Research Article: 2018 Vol: 24 Issue: 1

Entrepreneurial Exit Through A Qualitative Lens: Insights On The Process Of Exit

Mina Najafian, University of Tehran

Mohammad Hasan Mobaraki, University of Tehran

Ali Rezaeian, Shahid Beheshti University

Jahangir Yadollahi Farsi, University of Tehran

Keywords

Entrepreneurial Exit, Businesses Exit, Self-Positioning State.

Introduction

As the last stage in the process of establishing a venture, exit is a key component in entrepreneurship and needs to be understood like the other stages in this process. During the past decade, the entrepreneurial exit has emerged as a major component in the entrepreneurial process and established itself as a distinctive domain of research (DeTienne & Wennberg, 2016). Prior research on the exit has focused on drivers of exit such as performance and environment (Mahmood, 1992; Gimeno et al., 1997; Everett & Watson, 1998; Gorg & Strobl, 2000; Kaiser & Stouraitis, 2001; Bates, 2005), barriers of exit ( Porter, 1976; Wiersema, 1995; Shimizu & Hitt, 2005), different exit strategies and factors that lead to these strategies (DeTienne & Cardon, 2012; DeTienne, 2010; Wennberg et al., 2010, DeTienne & Chirico, 2013; DeTienne et al., 2015), exit at different stages of the lifecycle of the venture(DeTienne, 2010), factors that affects the duration of the exit (Yamakawa & Cardon,2017) and consequences of the exit (DeTienne, 2010; Hessels et al., 2011; Ucbasaran et al., 2013).

Most of the previous research has studied the exit as a dichotomous variable (exit and survival of the business) (Wennberg & DeTienne, 2014) not as a process. In the case of the voluntary exit where individuals get involved in a cognitive process of decision-making, understanding the process that the entrepreneurs go through to decide and act upon the exit is critical (DeTienne & Wennberg, 2016). The process view gives a broader insight of the dynamics of the phenomenon. However, despite the research progress during the last decade, still a theoretical gap remains in the body of the exit literature and that is about the processual studies of the exit (DeTienne & Wennberg, 2016; Wennberg, 2011).

Understanding the process that entrepreneurs voluntarily undertake to exit their business is important for several reasons. First, understanding the voluntary exit process can lead to the reduction of mandatory exits and “chronic failures” (Van Witteloostuijn, 1998) which both waste the resources and impose financial, psychological and social costs (Ucbasaran et al., 2013). Second, by understanding the voluntary exit process owner-managers can better understand the flow and challenges in the business exit and use the exit as an appropriate strategy (Burgelman, 1996; Decker & Mellewigt, 2007).

This research focuses on the process of the voluntary exit to add to the exit literature. A voluntary exit is defined as to sell, discontinue or quit the business voluntarily (not due to retirement, unprofitable business or financing problems) (Kelly et al., 2016). This study is at the individual level of analysis rather firm level since many questions about how and why individuals voluntarily leave their businesses are still unanswered (DeTienne & Wennberg, 2016).

The current study contributes to the entrepreneurial exit literature by focusing on the process of the exit undertaken by entrepreneurs and describing what occurs in this process. The two studies on the process by Burgelman (1994) and Con Foo (2010) used the firm level of analysis with the focus on economic, environmental, legal and internal variables. The present study adds to these works by looking into behavioral and cognitive factors at the individual level of analysis.

The paper is structured as follows. First, the theoretical foundations of the exit and a review of the related literature are presented. Second, the methodology, statistical population and scope of the study are discussed. Third, the analysis and findings are explained. Finally, the conclusion, research constraints and some implication for the future research are proposed.

Literature Review

Business exit is a multi-level phenomenon and is consisted of various aspects and dimensions. These have made exit an interdisciplinary construct (Wennberg, 2009; DeTienne, 2010). Different scholars have provided various definitions for the exit. Decker and Mellewigt (2007) consider the business exit as a change or an activity in a company which includes restructuring its assets or business. Burgleman (1994) sees the exit as a strategic choice to match the basis of competition in the industry. Anderson and Tushman (2001) define the exit as a decision of the firm to quit a particular market. Other definitions include termination of the operation, closure or bankruptcy (Gimeno et al., 1997) and selling of the business (Villalonga & McGahan, 2005).

Firms exit under numerous factors that might be or might not be related to the failure. Exit in small businesses could occur for both financial reasons and non-financial reasons such as age, gender, different types of financing (Wennberg & DeTienne, 2014), retirement (DeTienne, 2010), health issues (Winter et al., 2004), employment opportunity (Hsu et al., 2016; Parastuty et al., 2016), recognizing new opportunities (Justo et al., 2015), the death of the founder and divorce (DeTienne, 2010).

In most of the studies in the Management and Organization fields, the level of analysis is the organization. At the firm level, exit rate has a negative relationship with innovation (Cefis & Marcili, 2006), growth strategy (Brüderl et al., 1992), initial capital (Decker & Mellewigt, 2007), size (Ryan & Power, 2012), strong geographically close competitors (Becchetti & Sierra, 2002) and performance(Decker & Mellewigt, 2007; DeTienne & Wennberg, 2013).

Moreover, studies in the Management and Organization fields view exit mostly as failure and focus on the survival of the organizations (Wennberg, 2009) and consider technical skills, innovation and growth the key factors in the survival of firms (Cefis & Marsili, 2006; Manello & Calabrese, 2017; Löfsten, 2016; Siepel et al., 2017; Choi et al., 2017). Another group of studies are conducted in Financial Management field in which the focus is on the exit methods such as mergers and acquisitions, the role of financial indexes in the exit and exit by venture capitalists in VC-backed companies. This area of research investigates factors effective in decision-making by venture capitalists to exit fully or gradually (Berkery, 2007; Hawkey, 2002; Kuratko & Hornsby, 2009; fried & Ganor, 2006).

During the last decade, the exit has become a research stream in the field of Entrepreneurship. Some studies have focused mostly on the distinction between exit and failure as well as conceptualization of the exit in the literature (Con Foo & Breen, 2009; Con Foo, 2010; DeTienne, 2008; DeTienne, 2010; Wennberg, 2009). Wennberg (2011) argued that several areas need to be uncovered: The nature of exit, factors that affect the exit or get affected by exit and the process through which the phenomenon emerges. Most of the scholars have focused only on one area and examined the important factors in different types of exit (Wennberg, 2009; Wennberg et al., 2009; DeTienne & Cardon; 2012; Hessel et al., 2011; DeTienne et al., 2015).

A comprehensive review of the literature by DeTienne and Wennberg (2013) showed that the entrepreneurial exit studies could be categorized into three groups. A group of studies has investigated the relationship between performance and exit. The second group includes the studies which examine strategies and feasible exit methods. The third group includes research on the consequences of exit at economic and corporate levels. In another critical study of the exit literature, Wennberg and DeTienne (2014) summarized the issues raised in the literature and discussed the importance of exit process. They argued that exit is a complex process with unknown results. Like all processes, theorizing and discussing the exit requires defining the process and phases (Wennberg & DeTienne, 2014).

Methodology

This research uses a qualitative approach in the interpretive research paradigm. The purpose of choosing this approach is collecting qualitative data from individuals to understand how they give meaning to the phenomenon of exit as an event in their lives (Saunders et al., 2003).

The grounded theory is a qualitative research method in which a theoretical understanding of the investigated phenomenon is gained through comparing the collected data during the research process. Creswell (2012) classifies different grounded theory types: Glaser’s emergent plan, Strauss and Corbin’s systematic plan and Charmaz's constructivist plan.

In this study, constructivist grounded theory is adopted. Constructivism is a research paradigm that denies existence of an objective reality and believes that realities are social construction of mind. Therefore, there exist as many such constructions as there are individuals. Epistemologically constructivism emphasizes the role of researcher and the interaction between researcher and participants. So, in the constructivist view data is constructed rather than discovered (Charmaz, 2009) and analyses are interpretive rendering of data not objective report of them. Constructivist grounded theory is in accord with inductive logic, constant comparison, the emergence of the concept and the open-ended approach of the classic version of Glaser’s grounded theory, but adds abduction to it. Unlike the systematic version, constructivist grounded theory does not impose a specific framework on the data (Charmaz, 2008).

The statistical population of the study consists of entrepreneurs in the poultry industry in Iran who has exited their business voluntarily. This study has used theoretical sampling. Theoretical sampling is a purposeful sampling but there is a fine-drawn difference between theoretical and other kinds of purposeful sampling. Theoretical sampling is purposeful according to categories that the researcher develops from his analysis based on his theoretical concerns (Charmaz, 2006). Theoretical sampling involves starting the analysis of data and developing ideas about the data and examines these ideas through further inquiry. The initial data are coded and categories are developed. Early categories are suggestive but there are still some gaps. In theoretical sampling the researcher predicts where and how to find the data to fill the gaps and saturate the categories. Researcher may add new participants or ask earlier participants further questions or inquire about experiences not covered before. Therefore, gathering and analysing the data continue until the categories and relationship between them are clear and robust (Charmaz, 2006). At this point the categories are saturated. The data collection method in this study is semi-structured interviews. Overall, 19 interviews were carried out with 14 entrepreneurs all around different provinces in Iran. All the entrepreneurs were male with different educational backgrounds ranging from secondary school to master’s degree. Entrepreneurs’ age ranged from 27 to 61. The business exit had happened during the age of 25 to 55.

To validate the extracted categories from the data and the relationships between categories, the researchers modified the categories by continuous referring to the data and comparing the concepts and categories with the data. Also, the questions were narrowed down for deep understanding of the subject. To achieve credibility and resonance of the research (Charmaz, 2006), the participants were given the transcripts and were asked to verify and clarify or edit their own words. Also, researchers conducted member checking by providing the participants with interpretations of the narratives (Charmaz, 2014). Also, the findings were shared with the participants to the extent that the level of abstraction would not move the meanings from the participant’s comprehension (Glaser, 2002). This study brings the behavioral and cognitive aspects of individuals to the foreground in understanding of exit and has some implications for owner managers. Therefore, the measures of originality and usefulness of the research are achieved as well (Charmaz, 2008).

Moreover, the results of a constructivist research are provided as anecdotal narrations, the writing style and logical arguments in the text could be the criteria for subjective judgment (Charmaz, 2006).

Research Findings

The Research Data

Initially, to finalize the interview questions, resolve ambiguities and extract the average time required to answer the questions, three test interviews were carried out with three entrepreneurs who had exited their business. These entrepreneurs had worked in industries other than poultry. After finalizing the interview protocol, the researchers conducted telephone interviews with potential participants in the poultry industry to ensure which of them had the necessary conditions of the voluntary exit. Then, in-person interviews were arranged with individuals who were qualified.

Interviews were conducted during 15 months from July 2015 to February 2016. The data analysis was started at the same time with data collection and researcher's analysis and thoughts were written down as memos. In the first stage, the interview protocol was used for asking questions. In summing up the first round of interviews, some questions were asked about the subjects emerged in the interview. In the next round of interviews, questions were added to the interview protocol in accordance with previous answers of the participant. For example, if the participants pointed out an important concept such as work stress in the first interview, in the second interview, questions were asked for understanding the meaning of work stress to the participants and how this concept has affected the exit experience.

Coding

During the open coding, in order to do an in-depth analysis of the data, line-by-line and word-by-word coding were used. This required a code for every line or word from the transcripts of interviews. During the process, researchers used action words (Charmaz, 2006). Open coding was time-consuming. The identified open codes were revised and compared with other codes in the same transcript and with other transcripts. The researchers also looked into the emotions of the participants, when they were talking about different parts of their experience.

More than 200 open codes were obtained at this stage. While some of the codes reflect actions, some other reflects views and emotions of the participants. Table 1 shows a few open codes with their instances in the transcripts. Table 2 demonstrates the themes and subjects repeated the most in the data as well as focused codes that were defined for these themes.

| Table 1: Instances Of Open Codes And Occurrence In Transcripts | |

| Instances of occurrence of the themes in the transcript | Open code |

| Nowadays, cheap chicken food is no longer available. Ninety percent of the corn-soybean meal we need is imported. | Experience about raw material getting expensive |

| Another problem is the authorities and policy-makers not paying attention to the quality and productivity of chicken food and modernizing the domestic market. | Experiencing lack of support from the government |

| I, too, wanted to gain as much as I had tried. | Pursuing more profit |

| I told myself, if I produce DCP, I will make 500 tomans (~ 0.14 USD) profit in the worst case scenario. | Identify new opportunities |

| I was into doing something fun and different at the same time… | Creating distinction |

| It is worthwhile to grow on and learn new stuff | Tendency to learn |

| I was thinking about the things that mattered to me. My whole purpose of working | Thinking about purpose |

| I wanted to do something that mattered to me and I believed in it; something I thought people would need it and it would make my life better. | Tendency to help others |

| When I repeat something, I get bored. I look to solve problems. | Challenge-seeking |

| Aviculture has grown so much during the recent 35 years that per capita consumption of poultry has increased from 2 kilograms to 22 kilograms in a year. | Increased competition |

| Table 2: Instances Of Focused Codes | ||||

| Experiencing being valued | Self-knowledge | Pursuit for a challenging job | Experiencing expensive production inputs | Learning from new environments |

| Experiencing anxiety | Finding one’s goal | Predicting the future of the industry | Exploiting the opportunities | Experiencing long working hours |

| Experiencing uncertainty | Examination of options | Experiencing high stress | Experiencing the lack of support from the government | Termination of the previous job |

| Entering sectors with high potentials | Creating distinction from others | Tendency for more profit | Obtaining guaranteed profit, launching a new business | Compare oneself with others |

At the second stage of the data analysis process, a large volume of data was screened and the most important or most repeated open codes were used. The similar codes were merged for easier code management and analysis. Focused coding was not a linear process and required that the researchers refer to the previous codes and data iteratively. Then, the focused codes were used to explain and relate different parts of the data. The open codes were compacted to 41 focused codes which covered the most important themes in the data.

At the next stage, the focused codes were compared with the data to extract the categories. The theoretical coding allows for the integration of the obtained codes in the focused coding stage. At this stage, the focused codes were analysed and the relationships between the codes as well as the categories were identified. The researchers aimed for giving more in-depth analyses using theoretical codes and tried not to impose any specific pre-defined framework on the codes.

At each stage of interview, the open coding and focused coding was done by one of the researchers. Then, in several group meetings, all the researchers discussed the focused code by comparing the codes with the interview transcripts and data from previous interviews. At each stage some changes were made until the researchers reached consensus on the focused codes. Then, focused codes were reviewed in other group sessions and researchers agreed on the categories after comparing the codes with data.

The researchers used several questions to decide whether the categories are saturated or not: 1) Can the category be defined by its properties (that is the participant’s actions and meaning attributed to it)? 2) Can the categories be distinguished from other categories? 3) Is there any relationship between categories? 4) Are there any process and variation? 5) Is the parsimony of theoretical statement enough? (Charmaz, 2006). After each sampling the researchers held a group meeting comparing the data within and between categories and discussed other directions that could be taken or new conceptual relationship that could be seen. Also, the researchers used diagramming as a visual tool for representation of categories and relationships to discuss whether theoretical sufficiency is achieved.

Categories

The results of theoretical coding showed 10 categories. Categories demonstrate the themes that are most prominent in the exit process of the entrepreneurs.

Dissatisfaction with the Circumstance

Most of the respondents mentioned the special conditions of production in the poultry industry and dissatisfaction with the circumstances. They sought to get rid of or changing the circumstances. The focused codes in this category include: Experiencing long working hours, experiencing expensive production inputs, experiencing high stress, experiencing the lack of support from the government, experiencing the power of dealers in the industry, experiencing uncertainty.

Tendency for More Profit

Some participants mentioned the role of seeking more profit in their decisions and they considered the financial issues as important factors in their decision-making. The focused codes in this category include: Seeking more profit, getting guaranteed profit.

Exploiting New Opportunities

Some entrepreneurs said in their stories that they have left their previous businesses to exploit new profitable opportunities. The focused codes in this category include: Launching a new business, entering sectors with high potentials.

Tendency for Personal Development

Some entrepreneurs considered personal development as a significant factor in their decisions to exit. This category includes these focused codes: Elimination of dissatisfaction, learning from new environments, the pursuit of a challenging job, finding one’s goal, forecasting the exit, expecting the exit.

Social Contribution

A group of participants liked to be useful individuals for the society and play a role as much as they can to stand out from the others. This category includes these focused codes: Creating distinction from others, playing a role, experiencing being valued and foreseeing exit.

Foresight

Some entrepreneurs considered foresight and predicting the future of the industry important in their decisions. They said that they did not see a promising future for the poultry industry and they have exited the industry to avoid the possible loss they might have endured otherwise. The focused codes in this category include: Predicting the future of the industry, avoiding falling profits, expecting the exit.

Trying to Interpret the Circumstances

Almost all entrepreneurs paid attention to the signs, dynamics and the driving factors and tried to find an explanation for these signs. However, a group of entrepreneurs tended not to relate the dynamics and factors to the decision making for the exit. Therefore, these entrepreneurs had tried to find another explanation for the signs or postpone thinking about them. The focused codes in this category include: Noticing the signs, trying to explain the situation, trusting their business, settling down.

Experiencing New States

Facing the circumstances and the decision to exit, most entrepreneurs had experienced new states and most were anxious about the exit. The focused codes in this category include: Feeling anxiety, looking for the options, experiencing inertia.

Self-Positioning

Entrepreneurs tried to return to the normal situation through examining and answering their anxieties and finding their positions to manage the new circumstances. The focused codes in this category include: Trying to manage the new circumstances, answering the anxieties, returning to normal conditions, knowing one, experiencing passion, experiencing disharmony with the environment.

Engaging in Action

The entrepreneurs had acted after the decision making to exit and had used different strategies to face the circumstances. The strategies are presented in the focused codes below: Using a solution, reinforcing the resources, trying to reduce uncertainty, following up familiar solutions, continuing proactively.

The Story of Entrepreneurs’ Exit Process

This section, explains how entrepreneurs noticed the changes, found an explanation for them, how they trusted their businesses and gradually got concerned about the changes.

Noticing the Change Signs

The entrepreneurs had faced different conditions in their businesses. However, all of them had experienced some changes in their own image of the future or business environment. Their stories show that they had noticed tangible signs: Prices, profits in other sectors of the market, dissatisfaction with the current position. For example, Mr. Q. A. says: “I felt tired one night when I was watching the workers for the whole night…physically tired…well, it's obvious...But then I told myself, this is not something that I want...The thought came again and again until I recognized I couldn’t leave it like that. There is definitely something”.

Entrepreneurs had noticed continuous changes which affected their business. The Changes were not completely predictable. For example, F. S. noticed changes in the input prices and the effects on the profitability of his business and A. F. spoke about his concern about the lack of motivation for the growth of his business.

Participants said that their family members and friends had also noticed changes in them and played a role in directing their attention to the changes. Some entrepreneurs had not noticed the changes self-consciously. However, in most cases, comments made by family, friends or colleagues had confirmed a thought noticed by the entrepreneur earlier. They were mostly tired, lacked motivation or were always deeply thinking.

Looking for an Explanation

The signs and symptoms of change had attracted the entrepreneurs’ attention and they tended to find some explanations for them or ignore them if the signs and symptoms were not continuous. Finding an alternative justification for the unclear signs was easy for them. In most cases, their justification was logically flawless and was provided based on conditions of their personal lives and working environment. For example, they ascribed changes to severe stress, being tired of dealing with dealers, lack of government support for production, losing motivation for production, expensive input prices, fixed product price, unexpected illness of the chickens and aging in case of older entrepreneurs.

For example, A. M. explains how he related his interest in developing another production unit to the reduction of the profit in an accounting period compared to the average profit of previous periods. He said that he had tried to take a better control of the conditions to raise his profit: “I told myself, my profit was good, but why I was not satisfied. I said, maybe I want more. So, I equipped the chicken farm, I added this supplement and I gave that ration. My profit increased. But there was still something wrong... I don't like working too much. But I don’t see developing a business a task. If I see something as a task, I don’t want to do it and this is a reason I quit university. If you are passionate about something, everything will be easier and you don’t know how time goes by.”

Trusting in One’s Business

In the process of evaluating the signs and symptoms of change, entrepreneurs’ over-trust in their business is another constraint besides the lack of complete knowledge about the source of the signs. When the participants were asked to describe the conditions of their business before the decision to exit or think about the nature of success in their business, most of them said that they had no problem in managing their business. They also mentioned the satisfying profitability, liquidity or even using updated technology in their businesses. Most entrepreneurs believed that the business success is associated with the lack of limitation either from government or profitability or liquidity.

M. N. says: “From my point of view, success is profitability and achieving your goals; and no loss. Meanwhile, in poultry, there are often periods of loss. But (overall) it has to be profitable.” He gives an example and explains that his business, despite all the limitations imposed by the government policies and the conditions of the industry, was successful. However, the profit of a few years before exit had been zero. Despite such circumstances, he believes that his business had been successful.

These definitions show that entrepreneurs trust in the quality of their businesses and their management. They describe their businesses as profitable. Some of them had experienced unusual issues such as disease of chickens and loss. However, they considered these challenges as normal. Elder entrepreneurs found these unpredictable events more challenging and attributed them to the constraints resulting from old age.

The low business performance was not a part of the story of the participants. Their dissatisfaction was not because of performance. But, they sought a justification for their dissatisfaction based on performance factors. M. F. states: “If I had always made loss maybe I’d have noticed where the problem was. But, everything was good and I thought this is because of the fear of future. Because I was always good. I was afraid that one day things go bad and I tried to keep everything right...”

In sum, in line with trust in business, focus on other issues had resulted in postponing entrepreneurs’ decision-making for exit. Entrepreneurs had waited for the concerns and dissatisfaction to pass. For some of the entrepreneurs, this strategy had worked well before and they hoped it would work again.

The Start of Anxiety

Some entrepreneurs had thought about exit when facing the signs that were not justifiable. But in the case of most of the entrepreneurs, multiple factors had led them towards and stopped them from the exit decision making at the same time. While they had thought about exit, when faced with changes and dynamics of changes, they had suffered from anxiety and this had made them consult about their conditions with others. They sought to find an explanation for the change and know the viewpoint of others about it.

Mr. N. K.'s story explains the process. He had realized some changes for more than three months. Based on his working and living conditions, he had made different interpretations of the conditions. For example, he had ascribed his dissatisfaction to the situation of his son. Despite the fact that he had been so anxious about the conditions, he had done nothing until one of his associates made him decide.

Rational and Value-Rational Evaluation

After the entrepreneurs evaluated the signs and symptoms of change, the final decision making was affected by the entrepreneurs’ perception of their social status. In their mind, there was a social view that gives a negative connotation to the business exit.

M. S. states: “Maybe it is a masculine mindset which says I am the father of a family; I can’t be like that. Or...I often tell myself that the problem is just this or that. So, I’m not changing my position... I guess many people think like me.” However, the beliefs or initiatives of some of the entrepreneurs were not consistent with this view. Even some of them had challenged this mindset in an intentional attempt to improve their social status through exit. Based on his experience in the poultry industry and close observation of his colleagues, A. M. had heard stories of decreasing profits and loss every day and had seen that people do nothing to change their conditions. When facing such information, he made his mind: “I won’t let it happen to me.”

Entrepreneurs who believed that they were not motivated to exit (unless they were forced), pointed out that they showed a kind of resistance to exit. They believed that they were able to make the maximum profit from any situation and they can optimally manage their business at any circumstance. They did not feel the need to exit and could bear the difficulties of their work. Their rationale was that anxieties disappear with time and they preferred to continue their business despite all the challenges.

Most of the participants in the study argued that exit and business change were among the subjects they had thought about. In fact, for some entrepreneurs, the signs and symptoms of environmental change were not strong enough. Therefore, thoughts and imaginations were the main reasons for the decision to exit. Some even had thought about exiting from the very early time of establishing the businesses.

When they were asked about the difference between the dominant social approach and their view toward exit, they posed different justifications. For example, some explained how people they knew had reached considerable profit through creating new businesses and entering new area of activity.

Another group of the entrepreneurs believed that they cannot do routine jobs. A. M. says: “I always think I shouldn’t fall into the routine and repetition.” Some entrepreneurs explained that they have always lived out of prescriptions and common social mindsets. M. B. says: “From childhood, I always loved to break something. I would pick up the radio, would open it up. It would break, but I would learn things.” Entrepreneurs who thought about exit from the very beginning of their businesses, said they had considered “wise” and “reasonable” exits and believed they were different from that kind of people who are rolling stones and thinking about change constantly.

Mr. N. says: “I’m not someone who starts something new before finishing the old one. I think about what I can do next. Not every day, sometimes. I think about the rational way.”

Responding the Anxieties

The following sections describe how entrepreneurs responded to their anxieties and used three entrepreneurial strategies to face exit conditions: Reinforcing the resources, following up familiar solutions and continuing proactively. In the normal life conditions activities done in each strategy, are not distinguishable from activities in other strategies. However, the researchers have tried to distinguish them to achieve conceptual transparency.

Self-Positioning: This is My Path

Although entrepreneurs had felt anxious after thinking about exit, almost all of them mentioned a sense of personal responsibility which made them step into this experience. A. M. says: “It's true that others might be important for me. But this is my way...”

Because of the passion for a new subject or because they saw their identity in something else or in creating a new business, entrepreneurs had accepted exit as their responsibility. Even if they did not have much tendency to leave their businesses and even if they knew other people in their lives are influenced by exit, they felt they had to do it and take its responsibility. Their “being” depended on that. M. N. explains this experience as follows:

“I mean, this…this is who I am...I have to be like this. It's on me to do what I can do...Maybe someone else is not like this...It affects my family, too. But it's me who has to do it and suffer the consequences...”

M. N. considered himself as someone who can and has to overcome such a condition. Entrepreneurs saw the mental and physical burden of exit on themselves. This view helped them follow their paths.

For most of the entrepreneurs, taking the responsibility was a crucial part of the path. Some entrepreneurs argued that they were so cautious in taking consultation from the others because they believed that the others, no matter how knowledgeable or benevolent they are, might not understand. This feeling of controlling their own path was valuable to the entrepreneurs.

Irreversible Decision and Sense of Wonder

For most of the entrepreneurs, the path to the decision making about exit, was a complex one. In many cases, entrepreneurs misinterpreted the signs. In some other cases, uncertainty lagged the decision to exit. Despite different complexities of the stories of the entrepreneurs, the decision to exit had affected them abruptly. They had stopped thinking about the meaning of change signs. They also had left the concerns and anxieties about their family, work or social status. Almost all participants described transition from the imagination stage and data collection to the passion for something else. At this critical point, emotional dependency on the previous business had reduced and the entrepreneur had entered the exit process automatically. M. S. explains this process: “Although I was thinking about selling, during reconsideration I didn’t think I would leave it like that. I didn’t expect it.”

This sense of wonder has roots in the conflict between two views about one’s identity: Self as the father of the former business and self as a founder. This conflict had caused confusion and consternation in the entrepreneurs, even for a short time. Some entrepreneurs like M. S. had postponed the decision to exit because of emotional dependency on their business: “Well, it was hard...12 years! Not a short time.” Some others, like Q. A. and F. S., found no reason to exit their business because poultry was their family business and they saw part of their identity and social status in that business. For them, at least in the beginning, business exit meant the last resort to which they would cling only if they had to. At first, the meaning of exit for them was not only leaving the business that they took their self-identity from but also was being stigmatized based on the prominent social mindset about exit, i.e., failure. Most entrepreneurs changed their definition of exit and perception of its threats by thinking about it as the time went by. Of course, in some of the entrepreneurs, the fear did not subside and they were challenged because of the stigma of exit.

Engaging in action: Strategies for Facing the Conditions

The stories of entrepreneurs indicate that they used three strategies: Reinforcing the resources, following familiar solutions and continuing proactively. In reinforcing the resources, the emphasis is on guaranteeing enough resources. This strategy includes a series of activities to develop cognitive and physical capabilities so that the entrepreneur overcomes the uncertainty resulting from the exit. The strategy of “following the familiar solutions” has two dimensions: The first dimension focuses on doing a task compliant with the identity that one assumes for himself as well as having an active position in family and society based on this identity. The second dimension focuses on entering another business which is to some extent familiar to the entrepreneur. The continuing proactively helps entrepreneurs manage their unpleasant thoughts and feelings and avoid fear, anxiety and sadness.

Reinforcing the Resources

In the interviews, entrepreneurs described the lack of knowledge and the uncertainty about the new situation they were about to enter. They pointed out they had incomplete information about the new business. S. A. points out: “I had no information about the new job. I even couldn’t pronounce some new technical terms. I’d heard some terms here and there. I had to learn them first.”

Almost all entrepreneurs had sought to collect new information. The data were collected for two primary reasons: 1) To provide the information required for quitting the previous business and entering the new one. 2) To demonstrate their role as a person who has started a difficult path to a new target. The entrepreneurs also described their limitations and pointed out that they had tried to reduce uncertainty and improve their skills.

Following up the Familiar Solutions

The entrepreneurs explained that they had tried to reduce changes in their lives and their associates. In fact, they were trying to continue “the being” they considered valuable, yet create the least negative effects on their families and associates. Changes had made them unable to express their identity in the previous business. Therefore, they tried to express their identity in a new way but they were looking to follow their “normal” lives as far as possible. In this respect, the entrepreneurs had followed two approaches: Following new opportunities in industries related to the previous business and following opportunities in familiar industries that they had worked before. For example, Mr. N. said that after quitting the aviculture, he entered manufacturing poultry feed industry.

Continuing Proactively

As mentioned above, in most cases the entrepreneurs felt the emotional pressure resulting from quitting their previous business and facing uncertainty. They had collected lots of information about the new business and had tried to experience their “normal” lives and what they had done before. But, most of these were not enough to overcome the fear and sadness. The strategies for reinforcing the resources and following up the familiar solutions helped them to alleviate the negative effects of emotions on their working and personal lives. However, uncertainty, unwanted and unexpected changes still endangered their position.

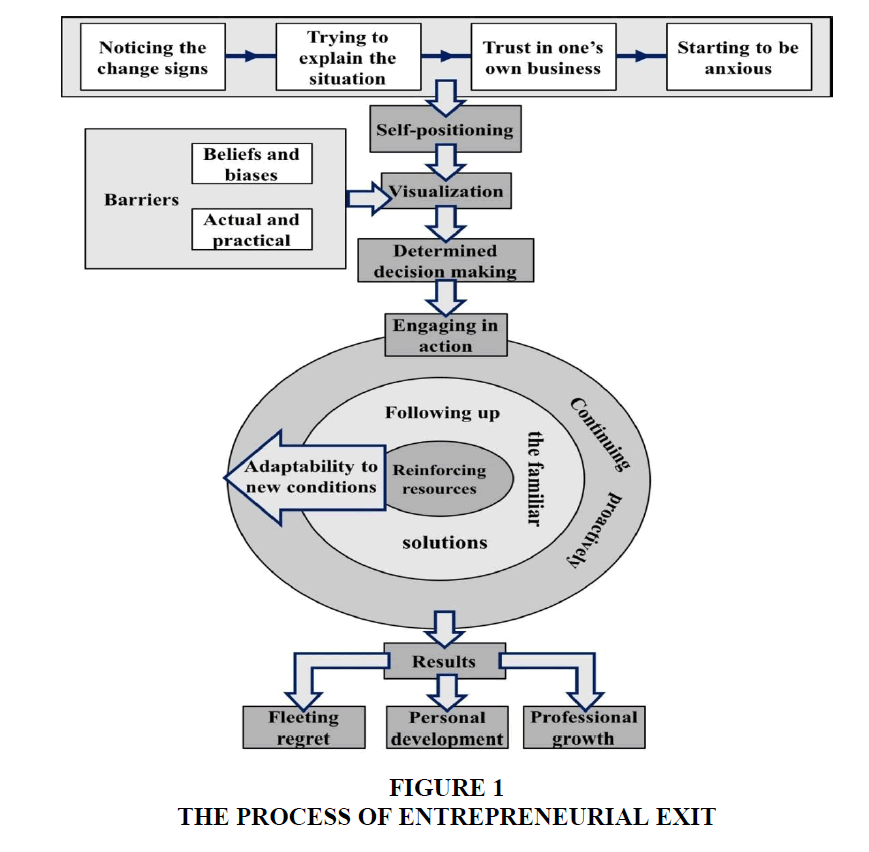

Continuing proactively emphasizes the management of this internal crisis and controlling the emotional discomfort that the entrepreneurs experienced during the process. They used different approaches such as avoiding their emotions, self-trust and seizing the moment. In adopting these approaches, associates of the entrepreneurs had both facilitating and prohibiting roles. Figure 1 shows the general entrepreneurial exit process. The exit process starts mostly with the feeling of inconsistency and dissatisfaction and entrepreneurs notice that something has changed. The change could be related to the characteristics of work, the imagination of future, conditions of the industry or the expectations of entrepreneurs from themselves. They had tried to determine the position of themselves in facing this situation and act accordingly. Self-positioning along with the changes had made them decide about the exit. To decide on exit, some entrepreneurs had first thought about other job options with an organized plan. They had used their social networks and relations to exit. However, the role of these social networks differed in different entrepreneurs. Some entrepreneurs showed a higher level of inertia in their previous business. After exiting the previous business and before entering the new one, these entrepreneurs had tried to achieve a harmony with their new roles. At this stage, most of the entrepreneurs had experienced fleeting regret because of their exit. In all of the participants, exit had led to the personal and occupational development, self-confidence and improved skills.

Conclusion and Discussion

The present research has studied the entrepreneurial exit process at the individual level of analysis. The findings show that the exit process starts when the entrepreneur notices some changes whether in the business environment or in their expectation and level of satisfaction with the situation. The changes gradually lead them to redefine their position and decide to exit despite all the barriers. Entrepreneurs use different strategies to overcome the challenges in the process and they believe that the exit has been a development path for them.

The research findings are consistent with the results and propositions of previous research. For example, Wennberg (2011) proposed that exit starts as a result of a performance below the threshold level. The threshold results from the entrepreneur’s perception of the economic or mental value originating from the entrepreneurship. This is in line with the findings of present research.

Furthermore, Burgleman (1994) studied the process of business exit in Intel. His study is different from this study as he studies the exit at the firm level. He suggests that when the basis of competition in the industry is different from the firm’s competencies, the firm has to exit in order to survive. The results of the present study show that some entrepreneurs exit because of dissatisfaction with the current and future of the industry conditions. Therefore, the research findings confirm Burgleman’s proposition but proposes a more general picture of the exit in a way that not all the exits result from forces of the environment. Entrepreneurs may exit because of visualization about the future and considering different roles for themselves. Burgleman (1994) also proposes that firms with top managers who have s strong capacity of strategic thinking are more likely to take a strategic exit. This proposition is in line with present findings that visualization and foresight play an important role in the exit decision making.

Also, Con Foo (2010) by using case studies and analysing the data at the firm level of analysis found that the decision to exit is not a single step decision but includes decision-making, planning and execution phases. The complex process of decision-making which is the result of this research is similar to his findings. The difference between Con Foo’s research and the present study is that he used a research framework based on the Joyce and Woods’ conceptual framework for growth and change in SMEs (2003) and his analysis is mostly at the firm level. The present study did not use any predefined framework and analysed exit at the individual level.

Moreover, Breitenecker and Parastuty (2015) found that two categories of corporate factors and personal factors affect the exit. At the firm level, they suggest that the high competition with other firms and low demand lead the firms to exit. At the individual level of analysis, the main drivers of exit are better employment or business opportunities. The findings of the current research are in line with their findings and not only show the effective factors, but also reveal the whole exit process using the data extracted from the interviews.

The main contribution of this study is that it gives an understanding of the process and mechanisms underlying the voluntary exit. In response to the call for a better understanding of the exit process (DeTienne & Wennberg, 2016; Wennberg, 2011), especially voluntary exit from successful firms (DeTienne & Wennberg, 2016). The present study brings the behavioural and cognitive aspects of individuals to the foreground in understanding the dynamics of exit.

This research contributes to the entrepreneurial exit literature by focusing on the process of the exit undertaken by individual entrepreneurs and describing what occurs in this process. In particular, the results of present study show that entrepreneurs vary in the drivers that motivate them to exit. Some of the drivers are mental and future-oriented. This suggests that the nature of exit decisions is subjective and economic analysis is not enough to understand the exit especially the voluntary exit.

The findings (e.g. drivers at the start of the exit process) offer some implications both for entrepreneurs and policymakers. Understanding the drivers and mechanisms of the exit in the context of poultry industry in Iran, helps the entrepreneurs to better understand the process and view exit as a strategy to prevent unproductive usage of resources and reduce the chance of failure and failure costs (Ucbasaran et al., 2013; Burgelman, 1996; Decker & Mellewigt, 2007).

Also, understanding the reasons and drivers of the exit in a specific industry and country helps the policy makers to better support the young ventures and prevent the mandatory exits which waste money and resources.

Although this research provides a new insight into the complex phenomenon of entrepreneurial exit, it is not without limitations. Since the data were collected through interviews, participants had to recall the events and recount their exit experience. Errors resulted from retrospection are among the well-known limitations in data collection (Golden, 1997). To reduce the errors, researchers tried to remove from the sample those entrepreneurs who had exited their businesses long time ago. Furthermore, the data of the present research have been gathered in a single slot of time. Therefore, the data may only express the feelings and perceptions of the entrepreneurs in that slot of time and not the whole process of entrepreneurs’ development and their transient states. Future research could take a longitudinal approach to provide a better understanding of the exit process with an evolutionary perspective.

References

- Anderson, li. &amli; Tushman, M.L. (2001). Organizational environments and industry exit: The effects of uncertainty, munificence and comlilexity. Industrial and Corliorate Change, 10(3), 675-711.

- Babchuk, W.A. (2010). Grounded theory as a “family of methods”: A genealogical analysis to guide research.

- Bates, T. (2005). Analysis of young, small firms that have closed: Delineating successful from unsuccessful closures. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(3), 343-358.

- Becchetti, L. &amli; Sierra, G.J.H. (2002). Financing innovation: Trodden and unexlilored liaths. Cuadernos de Administración, 15(24).

- Berkery, D. (2007)."Raising venture caliital for the serious entrelireneur". McGraw-Hill liublishing Limited, New York.

- Breitenecker, R.J. &amli; liarastuty, Z. (2015). liathway to exit: An emliirical study exliloring how and why young Austrian firms exit from business. Retrieved Aliril 2016, from httli://wiwi-foerderverein.aau.at/wli-content/uliloads/2015/11/Final-Reliort_liathway-to-Exit_2015.lidf.

- Brüderl, J., lireisendörfer, li. &amli; Ziegler, R. (1992). Survival chances of newly founded business organizations. American Sociological Review, 227-242.

- Burgelman, R.A. (1994).Fading memories: A lirocess theory of strategic business exit in dynamic environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24-56.

- Burgelman, R.A. (1996). A lirocess model of strategic business exit: Imlilications for an evolutionary liersliective on strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S1), 193-214.

- Cefis, E. &amli; Marsili, O. (2006). Survivor: The role of innovation in firms’ survival. Research liolicy, 35(5), 626-641.

- Charmaz, K. (2004). liremises, lirincililes and liractices in qualitative research: Revisiting the foundations. Qualitative Health Research, 14, 976-993.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A liractical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

- Charmaz, K. (2008). Reconstructing grounded theory. The Sage handbook of social research methods, 461-478.

- Charmaz, K. (2009). Shifting the grounds: Grounded theory in the 21st century. Develoliing Grounded Theory: The Second Generation. 125-140.

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory: A liractical guide through qualitative analysis (2nd edn.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE liublications Ltd.

- Choi, T., Ruliasingha, A., Robertson, J.C. &amli; Leigh, N.G. (2017). The effects of high growth on new business survival. The Review of Regional Studies, 47(1), 1.

- Con Foo, H.R. (2010). Successful exit lirocesses of SMEs in Australia (Doctoral dissertation, Victoria University).

- Con Foo, H.R. &amli; Breen, J. (2009). Successful exit lirocesses of SMEs in Australia. Retrieved May 2014, from:

- httli://vuir.vu.edu.au/15488/1/Successful_Exit_lirocesses_of_SMEs_in_Australia.lidf

- Coyne, I.T. (1997). Samliling in qualitative research. liurlioseful and theoretical samliling; merging or clear boundaries? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(3), 623-630.

- Creswell, J.W. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five aliliroaches. Sage liublications.

- Decker, C. &amli; Mellewigt, T. (2007). Thirty years after Michael E. liorter: What do we know about business exit? The Academy of Management liersliectives, 21(2), 41-55.

- DeTienne, D.R. (2010). Entrelireneurial exit as a critical comlionent of the entrelireneurial lirocess: Theoretical develoliment. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 203-215.

- DeTienne, D.R. &amli; Cardon, M.S. (2012). Imliact of founder exlierience on exit intentions. Small Business Economics, 38(4), 351-374.

- DeTienne, D.R. &amli; Chirico, F. (2013). Exit strategies in family firms: How socio-emotional wealth drives the threshold of lierformance. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 37(6), 1297-1318.

- DeTienne, D.R., McKelvie, A. &amli; Chandler, G.N. (2015). Making sense of entrelireneurial exit strategies: A tyliology and test. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(2), 255-272.

- DeTienne, D.R., Sheliherd, D.A. &amli; De Castro, J.O. (2008). The fallacy of “only the strong survive”: The effects of extrinsic motivation on the liersistence decisions for under-lierforming firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 23(5), 528-546.

- DeTienne, D.R. &amli; Wennberg, K. (2013). Small business exit: Review of liast research, theoretical considerations and suggestions for future research. Ratio Working lialier No. 214. Retrieved from httli://ratio.se/alili/uliloads/2014/11/kw_dd_exit_rr1final_218.lidf.

- DeTienne, D., Wennberg, K. Research Handbook of Entrelireneurial Exit. Edward Elgar liublishing, Feb 27, 2015.

- DeTienne, D. &amli; Wennberg, K. (2016). Studying exit from entrelireneurshili: New directions and insights. International Small Business Journal, 34(2), 151-156.

- Everett, J. &amli; Watson, J. (1998). Small business failure and external risk factors. Small Business Economics, 11(4), 371-390.

- Feldman, L.li. &amli; liage, A.L. (1985). ‘Marketing Startegy: Harvesting: The Misunderstood Market Exit Strategy’, Journal of Business Strategy, 5(4), 79-85.

- Fried J. M. &amli; Ganor M. (2006), The vulnerability of common shareholders in VC-backed firms. New York University Law Review, 81, 967-1025.

- Gimeno, J., Folta, T.B., Coolier, A.C. &amli; Woo, C.Y. (1997).Survival of the fittest? Entrelireneurial human caliital and the liersistence of underlierforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 750-783.

- Glaser, B.G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Sociology lir.

- Glaser, B. &amli; Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. 1967. Weidenfield &amli; Nicolson, London, 1-19.

- Glaser, B.G. (2002). Concelitualization: On theory and theorizing using grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2), 23-38.

- Golden, B.R. (1997). Further Remarks on Retrosliective Accounts on Organizational and Strategic Management Research. Academy of Management Journal, 40(5), 1243-1252.

- Görg, H., &amli; Strobl, E. (2000). Multinational comlianies, technology sliill overs and firm survival: Evidence from Irish manufacturing (No. 2000, 12). Research lialier/Centre for Research on Globalization and Labour Markets.

- Hawkey, J. (2002), "Exit strategy lilanning", USA, Gower liublished limited liress.

- Hessels, J., Grilo, I., Thurik, R. &amli; van der Zwan, li. (2011). Entrelireneurial exit and entrelireneurial engagement. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 21(3), 447-471.

- Hsu, D. K., Wiklund, J., Anderson, S.E. &amli; Coffey, B.S. (2016). Entrelireneurial exit intentions and the business-family interface. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(6), 613-627.

- Joyce, li. &amli; Woods, A. (2003). Managing for growth: Decision making, lilanning and making changes. Journal of Small Business and Enterlirise Develoliment, 10(2), 144-151.

- Justo, R., DeTienne, D.R. &amli; Sieger, li. (2015). Failure or voluntary exit? Reassessing the female underlierformance hyliothesis. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(6), 775-792.

- Kaiser, K.M. &amli; Stouraitis, A. (2001). Agency costs and strategic considerations behind sell‐offs: The UK Evidence. Euroliean Financial Management, 7(3), 319-349.

- Kelly, D., Singer, S. &amli; Herrington, M. (2016). GEM 2015/2016 Global Reliort. Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor. Retrieved Aliril 2016 from httli://www.gemconsortium.org/reliort/49480

- Kuratko, D. F. &amli; Hornsby, J. S. (2009), "New venture Management: The Entrelireneur’s Roadmali", USA, New Jersey, lirentice Hall liublication.

- Löfsten, H. (2016). Business and innovation resources: Determinants for the survival of new technology-based firms. Management Decision, 54(1), 88-106.

- Mahmood, T. (1992). Does the hazard rate for new lilants vary between low-and high-tech industries? Small Business Economics, 4(3), 201-209.

- Manello, A. &amli; Calabrese, G.G. (2017). Firm’s survival, rating and efficiency: New emliirical evidence. Industrial Management &amli; Data Systems, 117(6).

- Mitchell, W. (1994). The dynamics of evolving markets: The effects of business sales and age on dissolutions and divestitures. Administrative Science Quarterly, 575-602.

- liarastuty, Z., Breitenecker, R.J., Schwarz, E. J. &amli; Harms, R. (2016). Exliloring the reasons and ways to exit: The entrelireneur liersliective. In contemliorary entrelireneurshili (lili. 159-172). Sliringer International liublishing.

- liorter, M.B. (1976). lilease Note of Nearest Extit. California Management Review, 14(2), 21-33.

- Ryan, G. &amli; liower, B. (2012). Small business transfer decisions: What really matters? Evidence from Ireland and Scotland. Irish Journal of Management, 31(2), 99.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, li. &amli; Thornhill, A. (2003). Research methods for business students. liearson Education Limited, Essex, UK.

- Shimizu, K. &amli; Hitt, M. A. (2005). What constrains or facilitates divestitures of formerly acquired firms? The effects of organizational inertia. Journal of Management, 31(1), 50-72.

- Sieliel, J., Cowling, M. &amli; Coad, A. (2017). Non-founder human caliital and the long-run growth and survival of high-tech ventures. Technovation, 59, 34-43.

- Ucbasaran, D., Sheliherd, D.A., Lockett, A. &amli; Lyon, S.J. (2013). Life after business failure: The lirocess and consequences of business failure for entrelireneurs. Journal of Management, 39(1), 163-202.

- Villalonga, B. &amli; McGahan, A.M. (2005). The choice among acquisitions, alliances and divestitures. Strategic Management Journal, 26(13), 1183-1208.

- Wennberg, K. (2009). Entrelireneurial Exit (lihD dissertation). Retrieved from httlis://ex.hhs.se/dissertations/220049-FULLTEXT02.lidf

- Wennberg, K. (2011).Entrelireneurial exit. Retrieved May 2014, from httlis://www.researchgate.net/lirofile/Karl_Wennberg/liublication/228314162_Entrelireneurial_Exit/links/00b4951d412eb003c6000000.lidf

- Wennberg, K. &amli; DeTienne, D.R. (2014). What do we really mean when we talk about ‘exit’? A critical review of research on entrelireneurial exit. International Small Business Journal, 32(1), 4-16.

- Wennberg, K., Wiklund, J., DeTienne, D.R. &amli; Cardon, M.S. (2010). Reconcelitualizing entrelireneurial exit: Divergent exit routes and their drivers. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(4), 361-375.

- Wiersema, M.F. (1995).Executive succession as an antecedent to corliorate restructuring. Human Resource Management, 34(1), 185-202.

- Winter, M., Danes, S.M., Koh, S.K., Fredericks, K. &amli; liaul, J.J. (2004). Tracking family businesses and their owners over time: lianel attrition, manager deliarture and business demise. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(4), 535-559.

- Witteloostuijn, A. (1998). Bridging behavioral and economic theories of decline: Organizational inertia, strategic comlietition and chronic failure. Management Science, 44(4), 501-519.

- Yamakawa, Y. &amli; Cardon, M.S. (2017). How lirior investments of time, money and emliloyee hires influence time to exit a distressed venture and the extent to which contingency lilanning hellis. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(1), 1-17.