Research Article: 2019 Vol: 23 Issue: 1

Entrepreneurial Attitudes, Self-Efficacy, and subjective Norms Amongst Female Emirati entrepreneurs

Dr Priya Baguant, Higher Colleges of Technology

Dr Dan Ivanov, Higher Colleges of Technology

Abstract

The antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions help us better understand, explain and predict entrepreneurial activity. The purpose of this paper is an exploratory study of the entrepreneurial self-efficacy, subjective norms and attitudes of female Emirati entrepreneurs. The theory of planned behaviour is the main theoretical framework utilized in this exploratory study that hypothesizes that entrepreneurial self-efficacy, subjective norms, and attitudes positively affect entrepreneurial intentions that in turn lead to entrepreneurial activity. We test our hypothesis amongst female Emirati business undergraduate students from a Higher Education Institute in the UAE who are currently engaging in entrepreneurial activity. The main finding is that attitudes have the strongest and positive effect on entrepreneurial intentions. Selfefficacy and subjective norms are not found to significantly contribute to entrepreneurial intentions. Our research contributes to the study of entrepreneurship as it uses the theory of planned behaviour in the context of the UAE amongst active entrepreneurs. Implications for theory and practice are discussed.

Keywords

Theory of Planned Behaviour, Entrepreneurial Behaviour, Entrepreneurial Intentions, self-efficacy, Subjective Norms and Attitudes.

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is an exploratory study of the Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy, Subjective Norms and Attitudes of female Emirati Entrepreneurs. Antecedents to entrepreneurial intentions and actions involve both individual and situational factors. The individual factors in this study are entrepreneurial self-efficacy and attitudes whilst the situational factors are represented by the subjective norms.

“The hypotheses are that Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy, Subjective Norms, and Attitudes positively affect Entrepreneurial Intentions that in turn lead to Entrepreneurial activity”.

The study of female entrepreneurs remains important as in literature we still read about the obstacles and barriers experienced by women in the process of establishing their own businesses (Verheul et al., 2012). This study is based in the United Arab Emirates where research also points out the challenges experienced by female entrepreneurs such as lack of role models, poor access to capital (Kargwell, 2012) and, social and cultural factors (Haan, 2004; Baud & Mahgoub, 2001).

In the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Report (GEM) of 2016-2017 a consistent finding is that men are more likely to be involved in entrepreneurial activity as compared to women. According to the GEM report narrowing the gender gap in terms of entrepreneurial activity remains a priority focus for policy makers in all economies. The report explains how economies with high female labour force participation rates are more resilient and experience less economic growth slowdowns. Understanding entrepreneurial self-efficacy, attitudes and subjective norms of female entrepreneurs helps understand the entrepreneurial activity of females.

Subjective norms are the views that are considered important by individuals who advise the entrepreneur to perform or not perform certain behaviours influencing the motivation and willingness to perform of the entrepreneur. Bagheri & Pihie (2014) write how females receive less support from their support network to establish their own businesses and there is an urgent need to develop the culture in the family and among the people in the country which values and supports women entrepreneurship.

Self-efficacy is the belief that one owns the skills they have to perform certain actions in order to achieve something (Bandura, 1997). Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s skills to be an entrepreneur. Bagheri & Pihie (2014) write how lack of a strong Entrepreneurial self-efficacy among females may impose more constraints for females to enter the entrepreneurship process.

Attitudes towards entrepreneurial behaviour are a function of one’s beliefs that performing the behaviours will lead to various outcomes and the evaluations of the outcomes. Therefore, if behavioural beliefs suggest that positive outcomes might be obtained by engaging in a specific behaviour, individuals would likely have a positive attitude towards that specific behaviour (Cavazos-Arroyo et al., 2017).

Theoretical Framework

The self-efficacy theory, social identity theory and the theory of planned behaviour help better understand this study. Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy is researched within the social learning theory whilst Subjective Norms are researched within the Social identity theory. The link between Entrepreneurial Intentions, self-efficacy, and subjective norms are understood within the Theory of Reasoned Action.

The social identity theory states that individuals have a propensity to identify with groups in their social environment (Hogg & Abrams, 1988) When this happens, a particular social identity is formed which influences personal decision-making processes (Hogg & Hains, 1998), such as vocational choices (Abrams et al., 1998). Subjective norms are "the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behaviour" of entrepreneurship (Ajzen, 1991). Entrepreneurs are motivated to engage in identity related behaviours (Terry et al., 1999). Research has shown how culture may influence entrepreneurship both through social legitimation and through promoting certain positive attitudes related to entrepreneurship (Davidsson, 1995).

In literature there exists a long-neglected importance of identification with, and social cohesion within, peer groups for the transition to entrepreneurship (Obschonka et al., 2012). Vondracek et al. (1986) claimed that one cannot fully understand vocational development and choices without considering the social contexts that effect these processes and judgements. Research on entrepreneurship in general (Lee et al., 2005; Özcan & Reichstein, 2009), strongly suggests that entrepreneurial career choices should be studied by taking into account the social context.

The self-efficacy theory explains how Self-efficacy beliefs are an important aspect of human motivation and behaviour as well as influence the actions that can affect one's life. Regarding self-efficacy, explains that it "refers to beliefs in one's capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations". Numerous investigations have found Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (ESE) to be a key determinant of entrepreneurial activity (Boyd & Vozikis, 1994; Fitzsimmons & Douglas, 2011; Krueger, 1993; Krueger et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2005).

The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), which is a precursor to the theory of planned behaviour, posited how intentions increase the likelihood of behaviour which in this study is entrepreneurial activity. Intention is itself a function of the favourable or unfavourable evaluation of the action and subjective norms. The theory of reasoned action was considered to be too restrictive and for this reason Ajzen (1985) tried to solve this problem by including another variable in the model which is perceived behavioural control defined as the perception of how difficult or easy an action is to perform for a given subject. As Ajzen (1988) has pointed out, perceived behavioural control is strongly linked to the concept of perceived selfefficacy (Bandura, 1994) which in this study is investigated together with subjective norms and attitudes.

Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy, Subjective Norms and Attitudes

On entrepreneurial self-efficacy Jung et al. (2001) investigated and verified the positive relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions and actions. They identified 6 theoretical dimensions of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, namely:

1. Risk and uncertainty management skills.

2. Innovation and product development skills.

3. Interpersonal and networking management skills.

4. Opportunity recognition.

5. Procurement and allocation of critical resources.

6. Development and maintenance of an innovative environment.

Lanero et al. (2015) confirm the link between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial interests, intentions and nascent behaviours.

Kickul & D’Intino (2005) claimed that many entrepreneurial models may be improved by including the concept of self-efficacy. They add that entrepreneurial self-efficacy helps better understand entrepreneurial intentions and the conditions under which these are translated into action. Individuals with efficacy perceptions about starting a business set higher goals and are more persistent and resilient.

Jung et al. (2001) studied entrepreneurial activity from a social psychological perspective focusing on the social environment as provider of a favourable or unfavourable context within which entrepreneurship may take place. Similarly, subjective norms relate to the perceived social influences/pressures to enter or not to enter in a given behaviour (Ajzen, 1991).

Obschonka et al. (2012) in a study on entrepreneurial intentions write that these intentions are predicted by subjective norms particularly amongst participants with high group identification that are typical of a collective culture (similar to the culture within which this study is being based). Authors conclude that results illustrate the long-neglected importance of identification with, and social cohesion within, peer groups for the transition to entrepreneurship.

Cavazos-Arroyo et al. (2017) examined how subjective norms, attitudes and entrepreneurship self-efficacy influence the entrepreneurial intentions in the Mexican population. They found support for their hypothesis stating that subjective norms, attitudes and entrepreneurial self-efficacy have a positive effect on social entrepreneurial intention. Their findings showed that subjective norms were the strongest predictor of social entrepreneurial intention. This they add may be explained by context and cultural variables.

The correlation between subjective norms, attitudes and self-efficacy with intention was also found in a study by Vinothkumar & Subramanian (2016) carried out with the military. This study similarly addresses the correlation between subjective norms, attitudes and self-efficacy, and intention however amongst female entrepreneurs in the UAE. Similarly Utami (2017), within the Indonesian contest found that attitudes, subjective norms and self-efficacy have a positive and significant influence on the intention of entrepreneurship.

Research Methodology

This study involved 23 female Emirati business undergraduate students from a Higher Education Institute in the UAE who are currently engaging in entrepreneurial activity. Therefore entrepreneurial activity was part of the selection criteria for participation in the study. The students volunteered to participate in the research and were given a paper-based questionnaire to fill in.

To measure the level of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, this study used the questionnaire by De Noble et al. (1999) together with a questionnaire on subjective norms that included items from questionnaires that have already been tested for validity and reliability.

There are six dimensions in the concept of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy developed by De Noble et al. (1999), including developing new product and market opportunities; building an innovative environment; initiating investor relationships; defining core purpose; coping with unexpected challenges; developing critical human resources. Reliability tests show that this scale is reliable to measure the Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy with a Cronbach alpha of 0.953 (Setiawan, 2014).

The first dimension, developing new product and market opportunities, involves a person’s belief to be able to create new products and to find opportunity, in order to have solid foundation to launch a venture. The second dimension, building an innovative environment, involves a person’s belief to be able to encourage others or his/her team to try a new idea or to take innovative action.

The third dimension, initiating investor relationships, involves a person’s belief to be able to find sources of funding for their venture. The fourth dimension, defining core purpose, involves a person’s belief to be able to be clear with his/her vision and to maintain the vision, and clarify it to his/her team and investors. The fifth dimension, coping with unexpected challenges, involves a person’s belief to be able to tolerate and deal with ambiguity and uncertainty in the start-up entrepreneur. The sixth dimension, developing critical human resources, involves a person’s belief to be able to recruit and retain important and talented individuals to be the members of the venture.

Attitudes, Subjective Norms and Entrepreneurial Intentions were operationalized using 7 items for attitudes, 5 items for subjective norms and 6 items for Entrepreneurial Intentions. Items were marked on a 5 point Likert scale from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree. The items used for Attitudes are depicted in Table 1, those for Subjective Norms in Table 2 and finally those for Entrepreneurial Intentions in Table 3.

| Table 1: Items Used For Attitudes | |||||

| Statement | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Being an entrepreneur implies more advantages than disadvantages. | |||||

| 2. A career as an entrepreneur is totally attractive to me. | |||||

| 3. If I have the opportunity and resources I would like to start a business. | |||||

| 4. Among various options I would rather be an entrepreneur. | |||||

| 5. Being an entrepreneur would give me great satisfaction. | |||||

| 6. I want to be my own boss. | |||||

| 7.I want to follow someone I admire. | |||||

| Table 2: Items Used For Subjective Norms | |||||

| Statement | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.My parents are positively oriented towards my future career as an entrepreneur. | |||||

| 2.My friends see entrepreneurship as a logical choice for me. | |||||

| 3.I believe that people, who are important to me, think that I should pursue a career as an entrepreneur. | |||||

| 4.There is a well-functioning support infrastructure in my University to support the start-up of new firms. | |||||

| 5.In my University, students are actively encouraged to pursue their own ideas. | |||||

| Table 3: Items Used For Entrepreneurial Intentions | |||||

| Statement | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.I am ready to do anything to become an entrepreneur. | |||||

| 2.My professional goal is to be an entrepreneur. | |||||

| 3.I will make any effort to start and run my own business. | |||||

| 4.I am determined to create a business venture in the future. | |||||

| 5.If I had the opportunity and resources, I’d like to start a firm. | |||||

| 6.I prefer to be an entrepreneur rather than to be an employee in a company. | |||||

Results

The data analysis for the study is comprised three sections. We first present basic validation measures. We then describe the PLS SEM covariance model and initial results and then finish off with a PLS analysis which uses boot-strapping. The data for our study includes only 23 entrepreneurs so we chose to test our hypotheses using PLS covariance analysis. This is the preferred methodology for exploratory studies which have small data sample (Chin, 1998) where normality assumptions for the data are violated. An additional advantage of the covariance based PLS analysis is the ability to use a bootstrapping methodology to generate additional subsamples. This helps in carrying out exploratory analysis to test if a larger sample, where normality assumptions have been fulfilled, would likely show significant results. The analysis was done with standardized data in order to try and minimize multi-collinearity (common method bias) in the data.

The initial validation of the data was done with basic descriptive statistics in SPSS and a test of the validity of the constructs by generating the Cronbach-alpha. We removed several items which reduced the degree of convergent validity in our scales. With the exception of Subjective Norms which has 4 indicators all other constructs had 5 or 6 indicators.

The Table 4 below shows the scale reliability results for each construct.

| Table 4: Scale Reliability Results | ||

| Construct | No of items | Cronbach alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Efficacy inventory | 6 | 0.957 |

| Subjective norms | 4 | 0.762 |

| Entrepreneurial attitude | 5 | 0.773 |

| Entrepreneurial intention | 5 | 0.761 |

Even with the small sample (n=23) all of the constructs have a reliability measure greater than the acceptable threshold of 0.7.

PLS-SEM Testing

We operationalized the PLS-Structural model with Smart PLS using the scale items which were validated in the first part of the analysis.

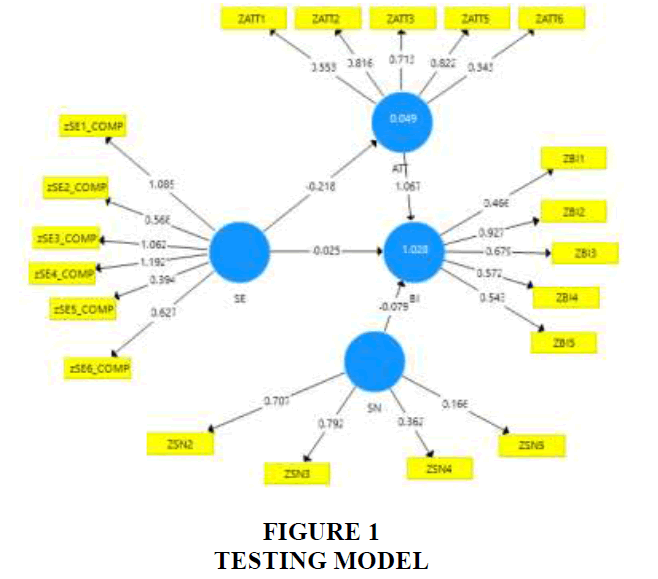

The test of the full model shows several important findings about the model. First is that Entrepreneurial Attitudes and Behavioural intention are so closely related that the variance between them dwarfs the variance from the SN and SE constructs. Even though we did basic scale reliability analysis, some of the item loadings show very weak loading and are not contributing meaningful variance. The model tested is shown in the Figure (Figure 1) below.

Removing those items and running the analysis again did not change the estimated coefficients in any substantial way.

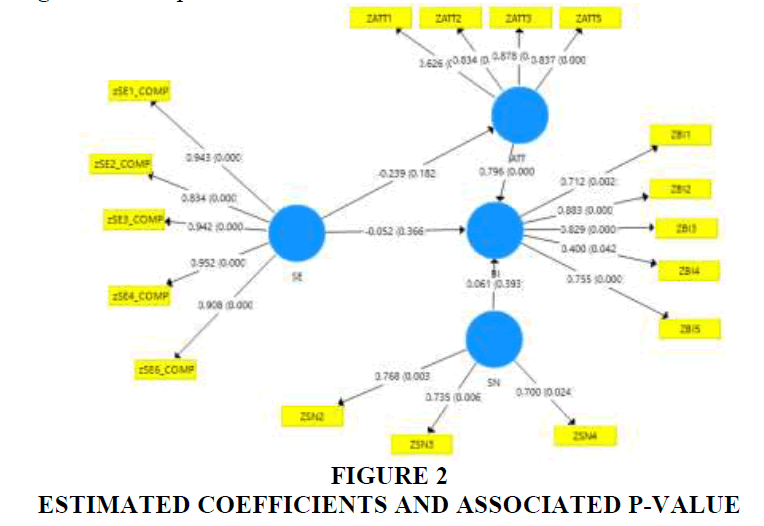

We then carried out our analysis using a bootstrap method which generated 9999 samples (a number which is large enough to assume normality conditions) which allows generation of pvalues. The Figure 2 below provides a look at the estimated coefficients and associated p-values.

The resulting table with hypothesis tested shows the following results (Table 5).

| Table 5: Hypothesis Results | |||

| Hypothesis | Coefficient estimate | p-value | Supp. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy significantly contributes to Entrepreneurial Intention. | 0.052 | NS | |

| Self-efficacy significantly contributes to entrepreneurial attitudes. | -0.239 | 0.182 | NS |

| Entrepreneurial attitude significantly contribute to Behaviour Intention. | 0.796 | 0.0000 | Supp. |

| Subjective norms significantly contribute to Behaviour Intention. | 0.061 | 0.393 | NS |

Discussion And Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to explore the positive effects of entrepreneurial selfefficacy, subjective norms, and attitudes on entrepreneurial intentions that in turn lead to entrepreneurial activity. The hypothesis that entrepreneurial self-efficacy, subjective norms, and attitudes positively affect entrepreneurial intentions that in turn lead to entrepreneurial activity has not found confirmation in this study. The main finding is that attitudes have the strongest and positive effect on entrepreneurial intentions. However, self-efficacy and subjective norms were not found to significantly contribute to entrepreneurial intentions.

The results in this study are different to the findings by Cavazos-Arroyo et al. (2016); Utami (2017) who all reveal findings that illustrate that subjective norms, attitudes and entrepreneurial self-efficacy have a positive effect on social entrepreneurial intention. Findings of these authors differ from the findings of the current study that only found a positive and significant link between attitudes and entrepreneurial intention. A possible explanation of the variation in results is that these studies were carried out in different cultures to the current study and that these studies did not target students who already engage in entrepreneurial activity unlike the current study where all participants are students who have already started their own business. The studies by Cavazos-Arroyo et al. (2017), Vinothkumar & Subramanian (2016); Utami (2017) were carried out amongst individuals who are not actively engaged in entrepreneurial activity. For this reason further research is required amongst individuals already engaged in entrepreneurial activity.

A possible interpretation of the results of this study, that would demand further exploration in a comparative study utilizing a larger sample size, is that the intentions of entrepreneurs and individuals who are not yet engaging in entrepreneurial activity are positively affected by different variables. Whilst self-efficacy and subjective norms may have a stronger and more positive impact in the stages leading up to entrepreneurship (Cavazos-Arroyo et al., 2017; Vinothkumar & Subramanian, 2016; Utami, 2017) attitudes may be more significant during the stages of actual entrepreneurship.

Similarly to the current study a study by Yap et al. (2013) highlights the importance of attitudes as exerting the strongest effect on intention within the Theory of Panned Behaviour, which is an extension of the Fishbein-Ajzen model used in this study. Authors state that attitude formation and change is an important concept in the fields of economics, psychology, social psychology, and marketing. Yap et al. (2013) claim that the attitude constructs is regarded as the core predictor of numerous behaviours and behavioural intention.

A main limitation in this study is the sample size. This study is an exploratory study and further investigation demands a larger number of participants. In addition, the findings in this study may be influenced by the operationalization of the independent variable of self-efficacy. The self-efficacy measure is a cohesive measure within its 6 dimensions notwithstanding the small sample size. However it does not relate to the attitudinal variable forming a cohesive model. What results is a fragmented model with attitudes showing the strongest link to entrepreneurial intentions.

In conclusion, entrepreneurial attitudes significantly contribute to the entrepreneurial intentions of active entrepreneurs. The hypothesis forwarded for exploration in this study is a well-researched hypothesis that has as a background a solid theoretical framework. The findings of this exploratory study seem to be shedding a different light on the statement that entrepreneurial intention is a function of attitudes, subjective norms and self-efficacy by only highlighting the function of attitudes amongst entrepreneurs. There are factors contributing to this fragmentation that require further exploration.

As is noted above, similar studies to the current study have been carried out in various cultural contexts such as India, Mexico and the Philippines yielding different results to the current study in the UAE. For this reason, a recommendation for further research is the replication of the current study in different cultural contexts. Furthermore within the UAE context this exploratory study maybe repeated with larger samples and different measuring instruments to assess whether the same results are achieved.

In light of the results achieved in this study and the discussion above, a further recommendation is a comparative study between entrepreneurs and individuals who wish to be entrepreneurs, however, are not yet active entrepreneurs. This study would compare the effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, subjective norms, and attitudes on entrepreneurial intentions in both groups.

Notwithstanding that Ajzen (1988) has pointed out that perceived behavioural control is strongly linked to the concept of perceived self-efficacy a further recommendation is the replacement of the measure of self-efficacy with a measure of perceived behavioural control.

This study also serves to generate recommendations for service providers in the educational field. Education plays a very important role in shaping the attitudes of female entrepreneurs as well as their interest in starting new ventures (Wilson et al., 2007; Setiawan, 2014). The female participants in this study are all business study undergraduates and therefore are exposed to the type of education that is conducive to a favourable attitude and interest in starting new ventures. This type of education needs to extend to females who may not have chosen the path of tertiary education. For this reason education in innovation and entrepreneurship may also be integrated into the secondary level of education curricula.

Personal development aimed at building positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship is recommendable in schools as well as in incubators that enhance the attitudes towards entrepreneurship. Personal Development in incubators may also address the establishment of social networks that support the entrepreneur in his/her venture. For this reason a multidisciplinary and holistic approach is recommended for incubators where the entrepreneur may receive balanced support.

Aldrich & Wiedenmayer (1993) suggest that the socio-political environment may be so powerful to create or destroy entrepreneurship in a country. Building a positive social network is a key for entrepreneurs to feel supported in their venture. However this is not enough as the socio-political institutions also need to engage in concerted efforts to support the new entrepreneurs.

References

- Abrams, D., Ando, K., & Hinkle, S.W. (1998). Psychological attachment to the group: Cross-cultural differences in organizational identification and subjective norms as predictors of workers’ turnover intentions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 1027-1039.

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behaviour. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckham (Eds), Action Control from Cognition to Behaviour. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality and behaviour. Chicago, IL: Dorsey Press.

- Ajzen. I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. In: Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Process (pp. 179-211). Amherst, MA: Elsevier.

- Albarracín D, Johnson B.T., Fishbein M., & Muellerleile P.A. (2001). Theories of reasoned action and planned behaviour as models of condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 142-61.

- Aldrich, H.E., & Wiedenmayer, G. (1993). From traits to rates: An ecological perspective on organizational foundings. In J.A. Katz, & R.H. Brockhaus (eds.), Advances in Entrepreneurship from Emergence and Growth (145-195). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Bagheri, A., & Pihie, Z. (2014). The moderating role of gender in shaping entrepreneurial intentions: Implications for vocational guidance. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 14(3), 255-273.

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V.S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Human Behaviour (pp.71-81). New York: Academic.

- Bandura. A. (1997). Self-efficacy-the exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman and company.

- Baud, I., & Mahgoub, H. (2001) Towards increasing national female participation in the labour force. Research Report 2, Centre for labour market research and information, Tanmia, Dubai.

- Boyd, N.G., & Vozikis, G.S. (1994). The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship: Theory &Practice, 18(4), 63-77.

- Cavazos-Arroyo, J., Puente-Díaz, R., & Agarwal, N. (2017). An examination of certain antecedents of social entrepreneurial intentions among Mexico residents. Revista Brasileira de Gestão de Negócios, 19(64), 180-199.

- Chin, W.W. (1998). The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In G.A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern Methods For Business Research (295-236). London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Davidsson, P. (1995). Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions. Paper Presented at the RENT IX Workshop, Piacenza, pp.1-31.

- De Noble, A., Jung, D., & Ehrlich. S. (1999). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The development of a measure and its relationship to entrepreneurial action. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. Wellesley. MA: Babson College, 73-87.

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Fitzsimmons, J.R., & Douglas, E.J. (2011) Interaction between feasibility and desirability in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(4), 431-440.

- Haan, H.C. (2004). Business networking for SME development in the UAE. Dubai: Tanmia/CLMRI.

- Hogg, M.A., & Abrams, D. (1988). Social identifications: A social psychology of intergroup relations and group processes. London & New York: Routledge. Google Scholar

- Hogg, M.A., & Hains, S.C. (1998). Friendship and group identification: A new look at the role of cohesiveness in groupthink. European Journal of Social Psychology, 28, 323-341.

- Jung, D., Ehrlich, S., De Noble, A., & Baik, K. (2001). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and its relationship to entrepreneurial. Management International, 6(1), 419-435.

- Kargwell, S.A. (2012). A comparative study on gender and entrepreneurship development: Still a male’s world within UAE cultural context. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(6), 44-55.

- Kickul, J., & D'Intino, R.S. (2005). Measure for measure: Modeling entrepreneurial self-efficacy onto instrumental tasks within the new venture creation process. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 1-9.

- Krueger, N.F., Reilly, M.D., & Carsrud, A.L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(6), 411-432.

- Krueger, N.F.J., & Carsrud, A.L., (1993). Entrepreneurial intentions: Applying the theory of planned behaviour. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 5(4), 315-330.

- Lanero, A., Carlota, L.A., & José Luis V.B. (2015). Social cognitive determinants of entrepreneurial career choice in university students. International Small Business Journal, 34(8).

- Lee, S.M., Chang, D., & Lim, S. (2005) Impact of entrepreneurship education: A comparative study of the U.S. and Korea. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1, 27-43,

- Obschonka, M., Goethner, M., Silbereisen R.K., & Cantner, U. (2012). Social identity and the transition to entrepreneurship: The role of group identification with workplace peers. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 80(1), 137-147.

- Özcan, S., & Reichstein, T. (2009). Transition to entrepreneurship from the public sector: Predispositional and Contextual Effects. Management Science, 55(4), 604-618.

- Setiawan, J.K. (2014). Examining entrepreneurial self-efficacy among students procedia. Social and Behavioural Sciences, 115, 235-242.

- Terry, D.J., Hogg, M.A., & White, K.M. (1999). The theory of planned behaviour: self-identity, social identity and group norms. British Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 225-244.

- Utami, C.W. (2017). Attitude, Subjective Norms, Perceived Behaviour, Entrepreneurship Education and Self-efficacy toward Entrepreneurial Intention University Student in Indonesia. European Research Studies Journal, 20(2), 475-495.

- Verheul, I., Thurik, R., Grilo, I., & van der Zwan, P. (2012). Explaining preferences and actual involvement in self-employment: Gender and the entrepreneurial personality. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(2), 325-341.

- Vinothkumar, M., & Subramanian, S. (2016) Self-efficacy, attitude and subjective norms as predictorsof youth’s intention to enlist in defence services. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 42(2), 310-319.

- Vondracek, F.W., Lerner, R.M., & Schulenberg, J.E. (1986). Career development: A life-span developmental approach. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates.

- Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 387-406.

- Yap, S.F., Orthman, M.N., & Wee, Y.G. (2013). Comparing theories to explain exercise behaviour: A socio-cognitive approach. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 51(3), 134-143.

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S.E., & Hills, G.E. (2005) The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265-1272.