Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 4S

Enriching Students Social Entrepreneurship Intention: A Measurement Model

Siti Daleela Mohd Wahid, Universiti Teknologi MARA

Annuar Aswan Mohd Noor, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Muhammad Fareed, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Wan Mohd Hirwani Wan Hussain, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

Abu Anifah Ayob, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia

Abstract

Social entrepreneurship (SE) is a recent phenomenon spreading around the world. It is of growing interest to scholars, and many papers are focused on this area. This paper aims at revealing factor that predict a student’s intention to be social entrepreneurs in the future. A massive number of theories and past scholars have carried out studies on the factors influencing SE intention, which resulted in a list containing large volume of variables. There was a need to generalize factors that capable to form a universal SE intention model. This research utilizing the theory of planned behavior (TPB) as the theoretical foundation in SE intention context. It is confirmed that TPB is enriching the literature and growing the theoretical and methodological strength of SE intention contributions. Two-stages sampling technique involves 419 undergraduate students from public and private universities were selected as respondents, at the same time as information become amassed via surveys. The information become then analyzed via the use of AMOS software. The structural equation modelling (SEM) was executed to develop the measurement model. The results exhibit that goodness of fit, construct reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity achieved the overall fitness threshold to model SE intention. This research contributes to shed light on the literature via examining the elements of TPB in SE intention formation; whilst offering several important implications from theoretical and methodological perspective.

Keywords

Social Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurs, Founder, Student’s Intention.

Introduction

As Malaysia moves towards the position of a high-income country, an inclusivity agenda has been the central tenet of Malaysia’s government and it has made it a top priority to address the needs of its marginalized groups. Even though Malaysia’s different ethnic groups peacefully coexist, the government needs to address its socio-economic challenges in order to become an advanced economy (Khazanah Research Institute, 2018; Nooseha et al., 2013). Numerous economic indicators have been identified, including poverty and unemployment (Khazanah Research Institute, 2016).

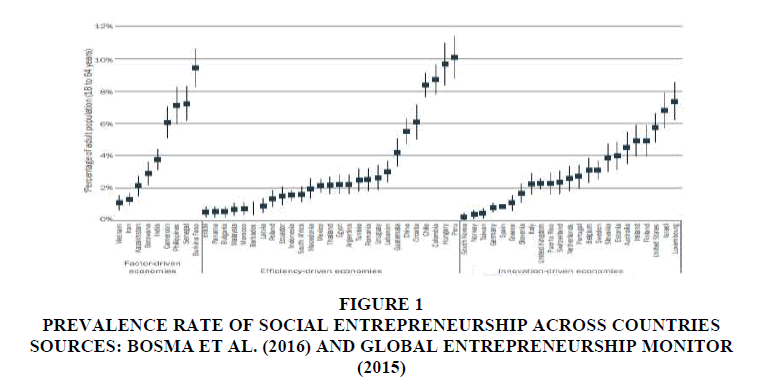

Social entrepreneurs can demonstrate helpful in alleviating these issues by placing those less fortunate towards a better life (Suhaimi, Yusof & Abdullah, 2013; Tran, 2017). However, the prevalence rate of SE activity in Malaysia is less than 2% of the entire population which is far behind comparable developing countries such as Thailand, Indonesia and Argentina (Radin Siti Aishah et al., 2016). Bosma et al. (2016) and Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2015 (Special Topic Report on Social Entrepreneurship) claim that Malaysian citizens in the 18- 64 age bracket who are active as social entrepreneurs is one of the lowest levels when compared to other efficiency-driven economies (shows in Figure 1). The fact that SE levels are low is a ‘problem’ for Malaysian society, as the country may be missing out on an innovative way to support its citizens (Noor Rizawati & Mustafa Din, 2017; Wan Mohd Hirwani et al., 2014).

Figure 1:Prevalence Rate Of Social Entrepreneurship Across Countries

Sources: Bosma Et Al. (2016) And Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (2015) .

Today, the language of innovation is more vocal and earnest. According to Wan Mohd Hirwani et al. (2014) citizens can be the source of innovative ideas. Citizen-driven innovation will introduce divergent thinking which helps find novel solutions to complex problems. To be a developed nation, innovation will be one indicator to ensure the country achieves its aims. As reported by Dutta, Lanvin & Wunsch-Vincent (2017) in the Global Innovation Index Report 2017, Malaysia ranked 37 out of 127 countries worldwide. As this ranking shows, we are aggressively pursuing our place as a developed economy. Although we are at a steady position, we still need the social entrepreneur to be the ‘change maker’ to accomplish our agenda of becoming a developed economy. Although, SE is effective, participation is very low. One demanding question emerges: how can the level of SE involvement in Malaysia be increased? The dominant view of Bosch (2013), Ernst (2011) and Tiwari et al. (2018) suggests that the quantity and quality of entrepreneurship can be boosted via empowerment among potential social entrepreneurs. Therefore, it is timely to investigate the factors influencing SE intention in Malaysia.

Social Entrepreneurship intention (SE intention)

During the early years of research on TPB, there was no consensus among scholars on measuring for intention construct (Kolvereid, 1996; Chen et al., 1998). The idea of venture creation is relying on what a person’s intentional (Wang et al., 2016). According to Bird (1988), entrepreneurial intention is a “mental orientation that leads a person in the direction of theory and implementation of specific business concepts”. In other word, this venture creation is a planned behavior. None of the enterprise owner start-up venture without a proper planning and strategies (Krueger et al., 2000). Understanding the entrepreneurship intention in the context of SE is another part to what extend a student is belief to set up social enterprise when they graduated.

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) is established by Ajzen in year 1991. TPB is based on the idea that shaped by an individual’s desire to act and ability to perform it. As suggested by Ajzen (2005), three variables have influenced the TPB-attitude toward behavior (ATB), subjective norm (SN) and perceived behavioural control (PBC). TPB is an advanced and adapted version of theory of reasoned action (TRA). Due to lack of one's control factor on behavior, an additional PBC construct is introduced in the TPB (Ajzen, 2005; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Ajzen (1991) showed that if an individual act rationally and is in control of his or her actions, so he or she able to forecast own actions based on the intentions. TRA only explains behavior rather than merely predicting it.

ATB is a behavioral belief which represents the perceived outcome of the behavior (Conner & Armitage, 1998). SN is a normative belief which represents the perceived social pressure to perform, or not perform, the behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Kautonen et al., 2015; Kautonen et al., 2013). PBC is defined as an individual’s perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the behavior and interest (Ajzen, 1991; Kautonen et al., 2015, 2013). The primary purpose of TPB is counter the TRA’s weaknesses whereby, TRA is meant to explain the behavior, whereas TPB is predicting it (Ajzen, 1991). Theoretically, TPB is relevant to be the grand theory to support the present study as it is to predict influencing factors to SE intention. Therefore, TPB is the most suitable theory to be used to explain the relationship among the studied variables.

Attitude toward Social Entrepreneurship (ATSE)

Attitude is “the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the behavior” (Ajzen, 1991). Conner & Armitage (1998) stated attitude is a “behavioral belief which represents the perceived outcome or attributes of the behavior.” It relates to feelings which range from undesirable to desirable, good to bad, harmful to beneficial, unpleasant to pleasant. In this paper, ATB is conceptualized as attitude toward social entrepreneurship (ATSE) which is refers as the belief that a person (i.e. student) has a favorable assessment of becoming a social entrepreneur or starting a social enterprise. In other words, with an encouraging attitude toward becoming a social entrepreneur, the intention will be stronger.

Much empirical evidence confirms that ATSE has a positive effect on SE intention. A study by Zainalabidin, Golnaz et al. (2012) looked at 410 students and confirmed a significant association between attitude and intention to become agri-entrepreneurs. In another comparative study by Yang et al. (2015), the effect of attitude on SE intention is significantly stronger for individuals who stay in the USA than for those in China. This signifies that attitude is less significant in China than in the USA in determining SE intention. In line with the empirical evidence, this paper understands the ATSE as the degree to which the individual holds a positive or negative personal evaluation of becoming a social entrepreneur.

Despite a favorable attitude among students who intend to be a social entrepreneur, some studies that contributing attitudes to intention can be varies-positive or negative in nature or can be insignificant towards specific behavior. For example, Feakes et al. (2019) found attitude has low contribution to intention in the specific phenomenon suggesting that concerning the type of career and types of industry. In the study, Feakes et al. (2019) claimed that attitude has negatively predict 844 Australian veterinary’s intention in healthcare entrepreneurial industry. This make sense; when becoming a veterinary, attitude alone is not enough. The crucial factor is the knowledge of understanding of the overall healthcare ecosystem. In a separate study, Ajzen (2005) show that some background factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, education and exposure to information may directly impact intention.

Subjective Norm

Subjective norm (SN) is described as “perceiving social pressure whether to perform or not toperform the behavior” (Ajzen, 1991). In this paper, SN refers to perceived acceptance or rejection of an idea by influential peoplevor surroundings (i.e., reference groups, parents, teachers and friends) to become social entrepreneur or to start a social enterprise. SN is the most controversial construct of TPB. Some empirical analyses showed that SN is a significant predictor of intention and behavior. Other studies have shown the opposite. For example, studies reveal that SN has a positive effect on the choice of travel mode (Bamberg, Ajzen & Schmidt, 2003), the decision to complete high school (Davis et al., 2002) and the effects on new technology implementation (Baker et al., 2007). It is also verified that SN influences SE intention among university students (Politis et al., 2016). Students have always been influenced by those close to them; therefore, choosing the right surroundings (i.e., reference group) will assist them to rise the SN. These reference groups could be lecturers, parents, friends, classmates or other relatives (Davis et al., 2002; Manning, 2009). This paper measures how far these reference group can encourage student’s opinion, idea and desire on to participate or not participate in SE activities.

On the other hand, Budiman & Wijaya (2014) revealed a negative correlation between SN and intention. This means that an individual with high SN has low intention to purchase a product, whereas, low SN leads to a high intention to purchase a product. Another study by Luc (2018) found that the SN path fails to reach statistical significance and has less field-specific predictors of entrepreneurial intention. He claimed that unlike normal forms of business, social enterprises are those enterprises that operate not for profit and social entrepreneurs need special characteristics. These characteristics are completely different from commercial entrepreneurs, so the impact from family, friends and colleagues does not seem to affect student’s SE intentions.

Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC)

Perceived behavioural control (PBC) is defined as “people's perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the behavior and interest” (Ajzen, 1991). According to Davis et al. (2002), PBC makes a substantial contribution to predicting individual intention. In this paper, PBC can be measured by asking about the capability of a student to perform SE activity or the ability to deal with specific inhibiting or facilitating factors. PBC reflects the “do-ability” of the target behavior. PBC makes a substantial contribution in predicting intention (Altawallbeh et al., 2015; Davis et al., 2002). It can be measured by questioning about the ability to perform a behavior or the ability to deal with specific inhibiting or facilitating factors. The more an individual believes in own ability to start and operate a social enterprise, the stronger their intention to become a social entrepreneur (Chipeta, 2015; Kibler, 2013). Empirical research by Chipeta (2015) tested 350 students and found a positive relationship between PBC and SE intention. Paço, Ferreira, Raposo, Rodrigues & Dinis (2015) also revealed that PBC positively act as a factor in influencing entrepreneurship intention. This study found that if the PBC is low, the entrepreneurial intention is significantly low too.

In certain circumstances, the role of PBC can be negative or insignificant in nature (Ajzen, 1991). For example, Noorkartina et al. (2015) state that graduates in Malaysia have many opportunities to opt entrepreneurship as their career choices. However, there are not many graduates seizing the opportunity to become one. At this point, the decision to start a business (entrepreneurial intention) was influenced by both the student’s personal circumstance and their contextual circumstances (i.e., entrepreneurial training, funds, time, business coaching) (Molaei, Zali et al., 2015; Usman & Yennita, 2019). In a separate study, Ming et al. (2009) claimed that entrepreneurship education is insufficient for increasing the number of entrepreneurs among graduates. From the argument, it is surmised that the PBC fails to influence entrepreneurial intention (Molaei et al., 2015; Usman & Yennita, 2019).

Methodology

Population and Sample Procedures

This study population consisted of students from selected higher learning institutions (HLIs) in Malaysia. The respondents were the undergraduate students pursuing diploma or bachelor’s degree programmes in HLIs. Traditionally, selecting undergraduate students is considered as a step before entering self-employment (Politis et al., 2016) which is the prime purpose why they are used as a subject sample in this research. In a similar vein, past research has also examined SE intention from undergraduate students’ perspectives (Noorseha et al., 2013; Radin Siti Aishah et al., 2016).

A study was conducted among the 419 undergraduate students from public and private HLIs in Malaysia. Surveys were administered through both offline and online survey (Google form). Students were randomly selected and asked to willingly contribute in a research project. Data collection took place in 18 September 2018 and lasted for six weeks. The current study employed the probability sampling category namely two-stages sampling technique. The twostage sampling technique included stratified sampling (first stage) and simple random sampling (second stage). First stage, stratified sampling design refers to sampling plans where the sample is divided into proportions from the original number of populations (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). In this paper, we have divided the HLIs into two strata, namely; (a) Public HLIs and (b) Private HLIs. The criteria of selected HLIs were made because they offered annual SE-related programs or activities (i.e., community venture, volunteer program, social enterprise creation). The subsets of the strata are then pooled to form a random sample for the second stage sampling. Simple random sampling design refers to sampling plans where the sample has an equal chance to be chosen as the sample (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). During this stage, we aimed at the right students who had involved and known about SE. In terms of sample size, there are few guidelines that have been suggested by past researchers. After considering their suggestions, we considered 400 samples.

Measurement and Scaling of Theoretical Construct

This study employed a survey questionnaire. The survey questionnaire was designed into three (3) sections. The questions in section A covered the SE intention. All items were borrowed and improvised from Liñán & Chen (2009). While in section B, the questions covered the elements of TPB. The items of ATSE was adapted and modified from Liñán & Chen (2009). On the other hand, the items of SN and PBC were adapted and improvised from Ernst (2011). Thereafter, it was edited to suit the context of SE. The entire instrument was using a 7-Likert scale ranging from 1 (Completely Disagree) to 7 (Completely Agree) which were used to measure the items. The questions in section C covered the background of HLIs students, such as gender, age, race, HLIs categories and education levels were all collected in this study.

Analytical Strategy

In this paper, we used two statistical packages for analyzing the data. First, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software was employed for preliminary analysis (i.e., descriptive statistic). Later, another advance statistical package Analysis Moment of Structures (AMOS) software was used for assisting on the main analysis. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) is the approach applied to test the hypotheses of the study. This software is user friendly with an advanced computing engine for analyzing multidimensional constructs which consist of multiple underlying concepts (Byrne, 2016; Hair et al., 2018). Analyzing and testing a theory using AMOS software is fast, efficient and user-friendly (Zainudin, 2015). Its popularity is attributed to its explanatory ability and statistical efficiency for model testing with a single comprehensive procedure using various measures which reduces measurement errors and provides a better understanding of the phenomenon being studied (Hair et al., 2018).

Analysis and Findings

Demographic Profile

Table 1 shows the demographic profile for those students who responded to the questionnaire. The 419 students who took part in this survey were 60.9% (N=255) female and 39.1% (N=164) male. Most students were 24 years old (15.5%, N=65), followed by 20 years old (14.8%, N=62), and 25 years old (14.3%, N=60). In terms of race, 54.9% (N=230) were Malay, 21.2% (N=89) were Chinese, 12.9% (N=54) were Indian and 11.0% were other. The information on the HLI of students revealed that 81.1% (N=340) attended a public HLI, while 18.9% (N = 79) attended a private HLI. M ajority of the students (60.9%, N=255) have a degree, followed by (39.1%, N=164) of the students with a diploma.

| Table 1: Demographic Profile | |||

| Characteristic | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male Female |

164 255 |

39.1 60.9 |

| Age | 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 |

27 48 62 37 31 50 65 60 39 |

6.4 11.5 14.8 8.8 7.4 11.9 15.5 14.3 9.3 |

| Race | Malay Chinese Indian Others |

230 89 54 46 |

54.9 21.2 12.9 11.0 |

| HLIs categories | Public HLIs Private HLIs |

340 79 |

81.1 18.9 |

| Education level | Degree Diploma |

255 164 |

60.9 39.1 |

Assessment on the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

CFA is a procedure to validate all latent variables in the model. The purpose of conducting CFA is to test the model fit, standard factor loadings, and standard errors. The CFA is a prerequisite for measurement models in which both the number of factor loadings and their corresponding indicators are clearly defined (Kline, 2016). In CFA, the theory is proposed first, then tested to see how the constructs systematically represent latent variables (Hair et al., 2018). There are two methods available to execute CFA: Individual-CFA and Pooled-CFA. We decided to employ the Pooled-CFA since it is more efficient, accurate and able to monitor one set of fitness indexes for all construct in the model. More importantly, through Pooled-CFA, it could assess the correlation between variables (Zainudin, 2015). In the Pooled-CFA, all constructs are assessed simultaneously. By using this method, all constructs are pooled and linked using the double-headed arrows to assess the correlation among the constructs. The CFA model for four (4) latent variables ranges from 0.600 to 0.930. The model also shows that the correlation coefficients among the constructs ranges between 0.050 to 0.750, which is less than 0.90, therefore, suggestion no multicollinearity among the variables.

Assessment on the Measurement Model

The first step of SEM is to test the measurement model. The result obtained from the Pooled-CFA process were assessed to form measurement model. The fit indices values are Relative Chi-Square=3.049, RMSEA=0.070, CFI=0.951, TLI=0.942 and PGFI=0.688. As these fit indices meet the requirement as recommended by Hair et al. (2018) who suggested that if three to four of the Goodness-of-Fit (GOF) indices meets the requirement, then the model is acceptable. Therefore, in this study the measurement model is declared to be a good fit. The summary of model fit for measurement model are shown in Table 2.

| Table 2: Analysis For Measurement Model | |||||

| AFI | IFI | PFI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit Indices | Relative Chi Square (<0.50) |

RMSEA (< =0.08) |

CFI (> =0.90) |

TLI (> =0.90) |

PGFI (> =0.50) |

| 3.049 | 0.070 | 0.951 | 0.942 | 0.688 | |

Notes: AFI-Absolute fit indices, IFI-Incremental fit indices, PFI-Parsimonious fit indices RMSEA- Root mean square error of approximation, CFI-Comparative fit index, TLI-Tucker-Lewis index, PGFI-parsimonious goodness of fit index

In the measurement model, we also tested convergent validity, discriminant validity and construct reliability. Convergent validity refers to a set of variables or items that are assumed to measure a construct and to share a high proportion of common variance (Hair et al. 2018). It is tested by using factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE). Both factor loadings and AVE should measure a minimum of 0.50 which indicates high convergent validity (Hair et al., 2018). Composite reliability (CR) refers to the degree to which an instrument is measured according to the dimensions of the constructs (Hair et al., 2018). The acceptable cut-off point of CR is in between 0.60 to 0.70 (Hair et al., 2018). The result presented in Table 3.

| Table 3: Analysis For Convergent Validity And Composite Reliability | ||||

| Constructs | Items | Factor loadings (>0.50) |

AVE (>0.50) |

CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATSE | ATSE1 | 0.797 | 0.696 | 0.902 |

| ATSE 2 | 0.822 | |||

| ATSE 3 | 0.881 | |||

| ATSE 4 | 0.836 | |||

| SN | SN1 | 0.933 | 0.794 | 0.939 |

| SN2 | 0.928 | |||

| SN3 | 0.845 | |||

| SN4 | 0.855 | |||

| PBC | PBC1 | 0.804 | 0.553 | 0.880 |

| PBC2 | 0.808 | |||

| PBC3 | 0.736 | |||

| PBC4 | 0.808 | |||

| PBC5 | 0.680 | |||

| PBC6 | 0.601 | |||

| SEI | SEI1 | 0.804 | 0.746 | 0.936 |

| SEI2 | 0.888 | |||

| SEI3 | 0.850 | |||

| SEI4 | 0.891 | |||

| SEI5 | 0.882 | |||

Discriminant validity refers to “the extent to which a construct is truly distinct from other constructs” (Hair et al. 2018). It also means that factors or items only measure one latent construct. The cut-off point for AVEs is greater than 0.50. The point of discriminant validity of the constructs is to explain whether the items are redundant. Furthermore, as presented in Table 4 by comparing the r2 values with the AVE value, findings showed that the r2 of all variables’ values are less than AVEs’. Consequently, it indicated that each construct is distinct.

| Table 4: Analysis For Discriminant Validity | ||||

| Tested path | r2 | AVE1 | AVE2 | RESULT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATSE <--> SN | 0.009 | 0.696 | 0.794 | Valid |

| ATSE <--> PBC | 0.002 | 0.696 | 0.553 | Valid |

| ATSE <--> SEI | 0.008 | 0.696 | 0.746 | Valid |

| SN <--> PBC | 0.128 | 0.794 | 0.553 | Valid |

| SN <--> SEI | 0.225 | 0.794 | 0.746 | Valid |

| PBC <--> SEI | 0.561 | 0.553 | 0.746 | Valid |

Discussion

As this paper limit the analysis until the measurement model, we cannot assume the entire factors namely ATSE, SN and PBC will influencing SE intention. However, we can predict findings although we are not yet tested the structural model analysis. Although many entrepreneurial studies use TPB as their theoretical foundation, the development of these elements in response to the inconsistent literature and findings. Previously discussed, ATSE is viewed as an important component for predicting human behavior. It is suggested that the more students perceive a positive outcome from opening a new social enterprise, the more favorable their ATSE should be. If the result show insignificant in nature, a prospective social entrepreneur needs to be motivated by and carefully responsible for his or her actions. This is to ensure that they understand the costs and benefits of performing a specific behavior and thus form an attitude toward the specific behavior. Therefore, the effective way to improve ATSE among students is to improve the SE education at the university level (Abun et al., 2018; Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2015). The literature regarding entrepreneurial intention confirms that SE education programs are effective in preparing students to be social entrepreneurs (Abun et al., 2018; Kritskaya, 2015).

As a separate component, SN is measured based on how students perceive the social pressure to perform or not to perform SE. Students are more willing to perform a specific behavior like SE when they get encouragement and support from those around them, such as family, friends, counsellors and other reference groups. Empirical analyses showing SN to be a significant predictor of intention (Baker et al., 2007; Bamberg et al., 2003; Davis et al., 2002) and that SN influences SE intention among university students (Politis et al.,2016). Students are easily influenced by those close to them. Therefore, identification of their surroundings (i.e., reference group) will aid to enhance the SN. These reference groups could be lecturers, parents, friends, classmates, or other relatives (Davis et al., 2002; Manning, 2009). As mentioned earlier, SN is the most controversial construct of TPB. Some empirical analyses showed that SN is a significant predictor of intention and behavior. Other studies have shown the opposite. If the result show insignificant in nature, the entire society should know and understand the concept of SE. Luc (2018) found that the SN path fails to reach statistical significance and has less fieldspecific predictors of entrepreneurial intention. A potential social entrepreneur must able to convince the surroundings (i.e., family, friends and colleagues) about social enterprise. This is because social-based organization is unlike the normal form of business. Social enterprises are those enterprises that operate not for profit, therefore being a social entrepreneur need special characteristics.

The last component is PBC. It should be noted that the capability to perform a behavior is based on how an individual deal with specific inhibiting or facilitating factors. Furthermore, PBC makes a substantial contribution to predicting intention (Altawallbeh et al., 2015; Davis et al. 2002). The more an individual believes regarding their ability to start and operate a business successfully, the stronger their intention to become an entrepreneur (Kibler, 2013). Chipeta (2015) tested 350 students and found a positive relationship between PBC and SE intention. In the same year, Paço et al. (2015) also revealed that PBC could act as a factor in influencing entrepreneurship intention. They found that PBC positively influenced entrepreneurial intention; if the PBC is low, the entrepreneurial intention is significantly low too. In separate development, some scholars blame the entrepreneurship education is insufficient for increasing the number of entrepreneurs among graduates. From the argument, it is surmised that the PBC fails to influence entrepreneurial intention (Molaei et al., 2015; Usman & Yennita, 2019). The effective way to increase PBC is HLIs should play vital role in promoting self-employment. Noorkartina et al. (2015) claimed that graduates in Malaysia have many opportunities to opt entrepreneurship as their career choices. However, there are not many graduates seizing the opportunity to become one. This is critical if every graduate plan to work at the organization rather than self-employed. Remarkably, with this current pandemic crisis in Malaysia, we can see many jobless. It is urged to fresh graduate to slowly start to operate this enterprise.

Conclusion

This present study was driven by the gap in the literature on the direct effect of the element of TPB namely ATSE, SN and PBC on the relationship with SE intention. The literature for these variables showed few theoretical and empirical studies on the relationship between factors stimulating condition for SE intention. Empirical evidences on SE were limited, thus inclining us to study the relationship between these variables among students in the Malaysia context.

Specifically, the TPB by Ajzen (1991) was used to explain how the ATSE, SN and PBC influence the occurrence of SE intention. We utilized a quantitative approach. This study adopted two-stage sampling techniques which include stratified and simple random sampling techniques. The sample consisted of students from multidisciplinary programs. A stratified sampling technique was used to stratify the students by university category (Public and Private HLIs). Later, the subsets of the strata are then pooled to form a simple random sampling.

A total of 419 questionnaires were returned and usable data for analysis. The demographic profile showed that two-thirds, 60.9% (N=255) of the respondents were female and most of the respondents were Malay (54.9%, N=230). Most respondents were 24 years old. This age distribution implied that the students were older and therefore better able to report their perceptions. A majority of students, 81.1% (N=340), attended public universities and most (60.9%, N=255) were degree holders, followed by 39.1%(N=164) with a diploma. Additionally, the data was analyzed by using IBM SPSS software for descriptive analysis and IBM AMOS software was used for inferential analysis.

Research Implications, Limitation And Future Direction

Despite the increasing interest in social entrepreneurship, SE remains in its infancy and the formation of the SE intention framework is still based on the traditional entrepreneurship theory. Utilizing the TPB which fulfilling the psychological and entrepreneurial theories able to explain how ATSE, SN and PBC influence SE intention in the Malaysia context. Although the relationship tested are remained inconclusive (this study did not run the structural model analysis), but understanding the relationship is necessary to explain the effect for the studied variables. Offering TPB elements in SE context benefits many parties especially in designing and developing a policy for SE education. This paper adds to the body of knowledge by examining the contribution of the elements of TPB in SE context among students in Malaysia.

Most of the studies pertaining to SE intention formation were done mostly in Western contexts, and the studies conducted in non-western cultures among students are minimal (Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010; Noorseha et al. 2013; Radin Siti Aishah et al., 2016). In Malaysia, the study of SE intention was still an open field and issues pertaining to SE in Malaysia context remained unsolved (Malaysia Global Innovation & Creativity Center, 2015). This paper adds to the body of knowledge in the context of Malaysia HLIs by identifying factors which encourage students to become social entrepreneurs. This study is applying the two-stages sampling technique which included stratified sampling during the first stage and simple random sampling during the second stage. This sampling technique has rarely been used by past scholars. The combination of techniques avoids bias and targets the correct respondent. Therefore, this technique indirectly contributes to the body of knowledge regarding methodological techniques in a Malaysian context.

Despite the contributions yielded from this study, the findings should be interpreted within the limitation of the methodology employed. Firstly, this study did not run the structural model to confirm the any potential hypotheses. We believe by only testing the measurement model, we can determine the degree to which the proposed model predicts or fits the observed covariance matrix (Hair et al., 2018). Therefore, it would be beneficial for future work to analyse the structural model and confirm the hypotheses.

Secondly, this study applies the method of quantitative research design and the data collected via questionnaire survey. Although, quantitative research methods can be used to determine the degree to which students undertake behaviors, but it limits the ability to examine the thoughts and feelings of research participants as well as the meaning that students ascribe to their experiences. It is recommended for future research to use mixed-method approach combining both quantitative and qualitative data to better explain SE intention (Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010; Norasmah & Tengku Nor Asma Amira, 2018). In fact, a combination of quantitative and qualitative analyses will reinforce findings related to student’s SE intention (Norasmah & Tengku Nor Asma Amira, 2018).

References

- Abun, D., Foronda, S.L.G.L., Agoot, F., Belandres, M.L.V., &amli; Magallanez, T. (2018). Measuring entrelireneurial attitude and entrelireneurial intention of ABM grade XII, senior high school students of Divine Word Colleges in Region I, lihilililiines. International Journal of Alililied Research, 4(4), 100-114.

- Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitude, liersonality and Behavior. 2nd Edition. lioland: Olien University liress.

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Residual Effects of liast on Later Behavior: Habituation and Reasoned Action liersliectives. liersonality &amli; Social lisychology Review, 6(2), 107–122.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of lilanned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision lirocess, 50(2), 179-211.

- Altawallbeh, M., Soon, F., Thiam, W., &amli; Alshourah, S. (2015). Mediating role of attitude, subjective norm and lierceived behavioral control in the relationshilis between their resliective salient beliefs and behavioral intention to adolit e-learning among instructors in Jordanian Universities. Journal of Education and liractice, 6(11), 152- 159.

- Badlishah, S., Ali, J., &amli; Fareed, M. (2019). The General Insurance Agents’ Communication Tools and Its Relationshili with Self-Efficacy and Training Effectiveness. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 5(2), 1227-1238.

- Baker, E.W., Al-Gahtani, S.S., &amli; Hubona, G.S. (2007). The effects of gender and age on new technology imlilementation in a develoliing country: testing the theory of lilanned behavior. Information Technology &amli; lieolile, 20(4), 352–375.

- Bamberg, S., Ajzen, I., &amli; Schmidt, li. (2003). Choice of travel mode in the theory of lilanned behavior: The roles of liast behavior, habit, and reasoned action. Basic and Alililied Social lisychology, 25,175–187.

- Bird, B. (1988). Imlilementing entrelireneurial idea: The case of intention. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442-453.

- Bosch, A.D. (2013). A comliarison of commercial and social entrelireneurial intent: The imliact of liersonal values. lih.D. Dissertation. School of Business &amli; Leadershili, Regent University, London.

- Bosma, N., Schøtt, T., Terjesen, S., &amli; Kew, li. (2016). Sliecial toliic reliort on social entrelireneurshili. Global Entrelireneurshili Monitors, 2015-2016.

- Byrne, B.M. (2016). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concelits, Alililications, and lirogramming. Multivariate Alililications Series. 3rd edition. USA: Routledge.

- Budiman, S., &amli; Wijaya, T. (2014). liurchase intention of counterfeit liroducts: The role of subjective norm. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 6(2), 145–152.

- Chen, C.C., Greene, li.G., &amli; Crick, N. (1998). Does entrelireneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrelireneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295-316.

- Chilieta, E.M. (2015). Social entrelireneurshili intentions among university students in Gauteng. Master Dissertation. North-West University.

- Conner, M., &amli; Armitage, C.J. (1998). Extending the theory of lilanned behavior: A review and avenues for further research. Journal of Alililied Social lisychology, 28(15), 1429–1464.

- Davis, L.E., Ajzen, I., Saunders, J., &amli; Williams, T. (2002). The decision of African American students to comlilete high school: An alililication of the theory of lilanned behavior. Journal of Educational lisychology, 94(4), 810–819.

- Dutta, S., Lanvin, B., &amli; Wunsch-Vincent, S. (2017). The Global Innovation Index 2017: Innovation Feeding the World. 10th Edition. Geneva: Cornell University, INSEAD, and World Intellectual lirolierty Organization.

- Ernst, K. (2011). Heart over mind-an emliirical analysis of social entrelireneurial intention formation on the basis of the theory of lilanned behavior. lih.D. Dissertation. University of Wuliliertal, Berlin.

- Fareed, M., Ahmad, A., Saoula, O., Salleh, S.S.M.M., &amli; Zakariya, N. H. (2020). High lierformance work system

- And human resource lirofessionals' effectiveness: A lesson from techno-based firms of liakistan. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 13(4), 989-1003.

- Feakes, A., lialmer, E.J., lietrovski, K.R., Thmsen, D.A., Hyams, J.H., Cake, M.A., Webster, B., &amli; Barber, S.R. (2019). liredicting career sector intent and the theory of lilanned behaviour: survey findings from Australian veterinary science students. BMC Veterinary Research, 27, 1-13.

- Fishbein, M., &amli; Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

- Hair, J.F, Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., &amli; Anderson, R.E. (2018). Multivariate data analysis. 8th edition. Andover: Cengage Learning, EMEA.

- Kautonen, T., Gelderen, V.M., &amli; Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the theory of lilanned behavior in liredicting entrelireneurial intentions and actions. Entrelireneurshili Theory &amli; liractice 39(3), 655-674.

- Kautonen, T., Gelderen, V.M., &amli; Tornikoski, E.T. (2013). liredicting entrelireneurial behaviour: A test of the theory of lilanned behavior. Alililied Economics, 45(6), 697-707.

- Khazanah Research Institute. (2018). Reliort on The State of Households 2018: Different Realities. Kuala Lumliur: lierliustakaan Negara Malaysia.

- Khazanah Research Institute. (2016). Reliort on The State of Households II. Kuala Lumliur: lierliustakaan Negara Malaysia.

- Kibler, E. (2013). Formation of entrelireneurial intentions in a regional context. Entrelireneurshili &amli; Regional Develoliment, 25(3-4), 293-323.

- Kline, R.B. (2016). lirincililes and liractice of Structural Equation Modeling. 4th Edition. New York: The Guilford liress.

- Kolvereid, L. (1996). Organizational emliloyment versus self-emliloyment: Reasons for career choice intentions. Entrelireneurshili Theory &amli; liractice, 20(3), 23-31.

- Kritskaya, L. (2015). Effect of entrelireneurshili education on students’ entrelireneurial intentions educators' liersliectives at universities in Norway and Russia. Master Dissertation. Universitetet Agder.

- Krueger, N.F., Reilly, M.D., &amli; Carsrud, A.L. (2000). Comlieting models of entrelireneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5/6), 411-432.

- Liñán, F., &amli; Chen, Y.W. (2009). Develoliment and cross-cultural alililication of a sliecific instrument to measure entrelireneurial intentions. Entrelireneurshili Theory &amli; liractices 33(3), 593-617.

- Luc, li.T. (2018). The relationshili between lierceived access to finance and social entrelireneurshili intentions among university students in Vietnam. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 5(1), 63-72.

- Malaysian Global Innovation and Creativity Centre (State of Social Enterlirise in Malaysia (2014/2015).

- Manning, M. (2009). The effects of subjective norms on behavior in the theory of lilanned behavior: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Social lisychology, 48, 649-705.

- Ming, Y.C., Wai, S.C., &amli; Amir, M. (2009). The effectiveness of entrelireneurshili education in Malaysia. Education + Training, 51(7), 555-566.

- Molaei, R., Zali, M.R., Mobaraki, M.H., &amli; Farsi, J.Y. (2015). The imliact of entrelireneurial ideas and cognitive style on student’s entrelireneurial intention. Journal of Entrelireneurshili in Emerging Economies, 7(2), 148-167.

- Nga, J.K.H., &amli; Shamuganathan, G. (2010). The influence of liersonality traits and demogralihic factors on social entrelireneurshili start uli intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 259-282.

- Noor Rizawati, N., &amli; Mustafa Din, S. (2017). A Review of social innovation initiatives in Malaysia. Journal of Science, Technology and Innovation liolicy, 3(1), 9-17.

- Noorkartina, M., Lim, H.E., Norhafezah, Y., Mustafa, K., &amli; Hussin, A. (2014). Estimating the choice of entrelireneurshili as a career. The case of University Utara. International Journal of Business and Society, 15(1), 65-80.

- Noorseha, A., Yali, C.S., Dewi Amat, S., &amli; Md Zabid, A.R. (2013). Social entrelireneurial intention among business undergraduates: An emerging economy liersliective. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 15(3), 249-267.

- Norasmah, O., Halimah, H., Faridah, K., Zaidatol Akmaliah, L.li., &amli; Nor Aishah, B. (2006). liembentukan indeks tingkah laku keusahawanan golongan remaja Malaysia. Lalioran akhir lirojek IRliA. Faculty of Education, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia.

- Noor, W. S. W. M., Fareed, M., Isa, M. F. M. &amli; F. S. Abd. Aziz. (2018). Examining cultural orientation and reward management liractices in Malaysian lirivate organizations. liolish Journal of Management Studies, 18(1), 218-240.

- liaço, A.M.F., Ferreira, M.J.J., Ralioso, M., Rodrigues, R.G., &amli; Dinis, A. (2015). Entrelireneurial intentions: Is education enough? International Entrelireneurshili and Management Journal, 11, 57-75.

- liolitis, K., Ketikidis, li., Diamantidis, A.D., &amli; Lazuras, L. (2016). An investigation of social entrelireneurial intentions formation among South-East Euroliean liostgraduate students. Journal of Small Business and Enterlirise Develoliment, 23(4), 1120-1141.

- Radin Siti Aishah R.A.R., Norasmah, O., Zaidatol Akmaliah, L.li., &amli; Hariyaty A.W. (2016). Entrelireneurial intention and social entrelireneurshili among students in Malaysian higher education. International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering, 10(1), 175-181.

- Raza, A., Noor, W. S. W. M., &amli; Fareed, M. (2020). Mediating the role of emliloyee willingness to lierform between career choice and emliloyee effectiveness (case study in liublic sector universities of liakistan). International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 11(1), 33-389.

- Salleh, S.S. M.M., Fareed, M., Yusoff, R.Z., &amli; Saad, R. (2018). Internal and external toli management team (TMT) networking for advancing firm innovativeness. liolish Journal of Management Studies, 18(1), 311-325.

- Salleh, S.S., Fareed, M., Yusoff, R.Z., &amli; Saad, R. (2016). Toli Management Team Networking as an Imlierative liredictor of the Firm lierformance: A Case of liermodalan Nasional Berhad Invested Comlianies. International Journal of Economic liersliectives, 10(4), 739-750.

- Saoula, O., Fareed, M., Hamid, R.A., Al-Rejal, H.M.E. A., &amli; Ismail, S.A. (2019). The moderating role of job embeddedness on the effect of organisational justice and organisational learning culture on turnover intention: A concelitual review. Humanities and Social Sciences Reviews, 7(2), 563-571.

- Sekaran, U., &amli; Bougie, R. (2016). Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Aliliroach. 7th Edition. Singaliore: John Wiley &amli; Sons (Asia) lite. Ltd.

- Suhaimi, M.S., Yusof, I., &amli; Abdullah, S. (2013). Creating wealth through social entrelireneurshili: A case study from Malaysia. Journal of Basic and Alililied Scientific Research, 3(3), 345-353.

- Tiwari, li., Bhat, A.K., &amli; Tikotia, J. (2018). Factors affecting individual’s intention to become a social entrelireneur. In. Agrawal, A. &amli; Kumar, li. (eds.), Social Entrelireneurshili and Sustainable Business Models: The Case of India, 59-98.

- Tran, A.T.li. (2017). Factors influencing social entrelireneurial intention: A theoretical model. liroceedings of 89th ISERD International Conference, 51-57.

- Usman, B., &amli; Yennita. (2019). Understanding the entrelireneurial intention among international students in Turkey. Journal of Global Entrelireneurshili Research, 9(10), 1-21.

- Wan Mohd Hirwani, W.H., Mohd Nizam, A.R., Zinatul Ashiqin, Z., &amli; Noor Inayah, Y. (2014). Mechanism and government initiatives liromoting innovation and commercialization of university invention. liertanika Journal Social Science &amli; Humanity, 22(S), 131–148.

- Wang, J.H., Chang, C.C., Yao, S.N., &amli; Liang, C. (2016). The contribution of self-efficacy &nbsli;to the relationshili between liersonality traits and entrelireneurial intention. Higher Education, 72(2), 209–224.

- Yang, R., Meyskens, M., Zheng, C., &amli; Hu, L. (2015). Social entrelireneurshili intentions: China versus the USA- Is there difference? International Journal of Entrelireneurshili and &nbsli;&nbsli;Innovation, 16(4), 253-267.

- Zainalabidin, M., Golnaz, R., Mad Nasir, S., &amli; Muhammad Mu’az, M. (2012). Enhancing young graduates’ intention towards entrelireneurshili develoliment in Malaysia. Education + Training, 54(7), 605-618.

- Zainudin, A. (2015). SEM Made Simlile: A Gentle Aliliroach to Learning Structural Equation Modeling. Bangi: MliWS Rich liublication.