Research Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 2S

Enhancing International Negotiation Outcomes through Intercultural Competence and Ethical Practices

Hanene Hammami, Tabuk University, Saudi Arabia

Mohsen Debabi, University of Tunis Carthage

Citation Information: Hammami, H., & Debabi, M. (2025). Enhancing international negotiation outcomes through intercultural competence and ethical practices. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 29(S2), 1-10.

Abstract

This research delves into the domain of international marketing, with a specific focus on intercultural trade negotiations. While existing studies have explored the broader impact of culture on negotiation outcomes, there is a significant gap in understanding the role of intercultural competence in optimizing both relational and economic outcomes in negotiations involving masculine and feminine cultures. Additionally, the influence of unethical tactics, such as bluffing, on these outcomes has not been comprehensively addressed.

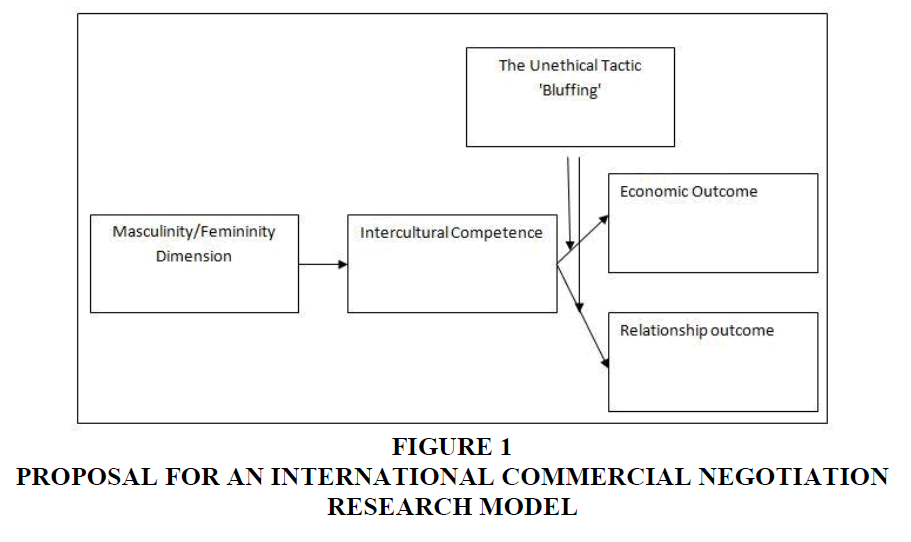

To fill these gaps, this study employs an exploratory qualitative approach, conducting in-depth interviews with professional negotiators experienced in international negotiations across different cultural dimensions. The findings offer new insights into how intercultural competence affects negotiation success and how bluffing moderates this relationship. Our primary contribution is the development of a theoretical model that clarifies the complex interplay between culture, competence, and ethics in intercultural negotiations. This model provides valuable guidance for researchers and practitioners alike, offering a deeper understanding and practical strategies for achieving successful international negotiations. Practitioners should focus on enhancing intercultural competence and adapting negotiation strategies to specific cultural contexts. Emphasizing ethical practices and utilizing the proposed theoretical model can lead to improved negotiation outcomes and the cultivation of sustainable international relationships.

Keywords

International Trade Negotiations, Masculinity/Femininity, Intercultural Competence, Bluffing, Relational Outcomes, Economic Outcomes.

Introduction

In the past decade, most research has focused on the impact of cultural differences on international negotiation outcomes, emphasizing how various cultural dimensions influence negotiation strategies and results (Khan & Ebner, 2019; Adler, 1994; Liang, 2022). On the international stage, negotiation frequently encounters cultural divergences and differences between negotiators, reflecting the increasing frequency of cross-cultural engagements (Korobkin, 2024). Understanding these cultural specifics offers companies significant competitive advantages, as noted by (Dupriez & Simons, 2002).

It remains unclear why some negotiators achieve better outcomes than others, particularly in negotiations involving negotiators from masculine versus feminine cultures. Despite valuable contributions to the field, such as those by (Debabi, 2010; Julien et al. 2015), there is an insufficient examination of how intercultural competence and unethical tactics, such as bluffing, impact negotiation outcomes.

This gap raises important questions about the role of intercultural competence and ethical practices in shaping negotiation results.

The purpose of this study is to address these gaps by investigating how intercultural competence affects negotiation success and how unethical tactics, such as bluffing, moderate this relationship in intercultural trade negotiations. This research aims to clarify how these factors interact and influence outcomes for negotiators from different cultural dimensions. The data used for this study were collected through in-depth interviews with professional negotiators experienced in international negotiations, focusing on diverse cultural contexts. This qualitative approach allows for a comprehensive exploration of the interplay between intercultural competence, negotiation tactics, and outcomes.

The findings of this study clearly show that higher levels of intercultural competence are associated with improved negotiation outcomes, and unethical tactics like bluffing can moderate this relationship. Our explanation for these findings emphasizes the critical role of understanding cultural nuances and ethical considerations in enhancing negotiation effectiveness. This study was limited by its focus on specific cultural dimensions and reliance on qualitative data from a limited sample of negotiators. Future research could build on these findings by incorporating quantitative methods and examining additional cultural variables to provide a more robust understanding of intercultural negotiation dynamics.

Theoretical Framework

Although trade negotiation plays a crucial role in marketing (Hammami & Dellech, 2022), it has historically been underexplored, with new research beginning to emerge in this field. In (Simmel, 1980) views negotiation as a fundamental relational process designed to manage conflicts and divergent viewpoints. This perspective emphasizes the complex and dynamic nature of negotiation as an interactive process between individuals. The influence of cultural factors on negotiation has been extensively studied by various scholars. In (Faure & Rubin, 1983; Binnendijk, 1987; Weiss, 1994; Salacuse, 1991; Salacuse, 1998; Gelfand & Dyer, 2000; Adair & Brett, 2004; Cohen, 2004; Debabi, 2010; Dellech & Debabi, 2017) have explored how cultural dimensions impact negotiation practices. Among these dimensions, (Hofstede, 2003) masculinity/femininity dimension, which examines the distribution of emotional roles by gender, is particularly relevant. Additionally, the tactics used in negotiation whether ethical or unethical—are of significant concern (Rees et al., 2019). In (Weingart et al. 1990) define tactics as specific behaviors employed during negotiation, while (Lewicki & Robinson, 1998) identify several unethical practices, including inappropriate information gathering, bluffing, information distortion, network manipulation, and competitive modes of negotiation. These issues raise critical questions: Do negotiators adhere to societal norms and rules when selecting their tactics? How do they differentiate between "just" and "unjust" actions? Does the absence of ethical considerations impact their competitive edge? The sparse literature on ethical rules in negotiation highlights a substantial research gap, signaling a need for more in-depth studies in this area.

This framework provides a comprehensive view of the theoretical underpinnings and contextual factors influencing trade negotiation, emphasizing the interplay of sociological, cultural, and ethical dimensions.

The existing literature provides a foundational understanding of trade negotiation, emphasizing the role of cultural dimensions and ethical considerations. In (Simmel, 1980) relational perspective on negotiation highlights the importance of managing conflicts through interactive processes, setting the stage for exploring how these processes are influenced by cultural factors. Key studies by (Faure & Rubin, 1983; Hofstede, 2003), and others have explored how cultural dimensions, particularly masculinity and femininity, affect negotiation tactics and strategies.

These insights reveal that cultural norms play a significant role in shaping negotiation practices, yet there remains a gap in understanding how unethical tactics specifically influence international negotiations.

Further, the literature on negotiation tactics, including unethical practices identified by (Weingart et al. 1990; Lewicki & Brinsfield, 2010), indicates that the choice of tactics is crucial and can vary significantly across different cultural contexts. However, there is a noticeable lack of in-depth research into the ethical implications of these tactics, particularly in the context of international negotiations.

The research question emerges from this gap in the literature: "How do unethical tactics affect trade negotiations across different cultural contexts, and what role does intercultural competence play in mediating these effects?" This question aims to address the identified gap by investigating the impact of unethical tactics in negotiations between cultures and exploring the significance of intercultural competence in navigating these tactics. The preliminary exploratory study, using semi-structured interviews with negotiators from Tunisia and France, seeks to provide empirical insights into this question, offering a deeper understanding of how cultural dimensions and ethical considerations intersect in international trade negotiations.

Methodology

Given the innovative nature of the research topic and the limited number of existing studies, a preliminary exploratory study is warranted to refine the definitions of the concepts within the research model (Igalens & Roussel, 1998). This qualitative study serves a dual purpose:

1. Exploratory Objective: To investigate and illuminate the potential role of unethical tactics in international negotiation contexts.

2. Complementary Objective: To augment the literature review with empirical insights through field research, facilitating triangulation to identify the most pertinent concepts. The study employs semi-structured individual interviews as the primary data collection method to assess the significance of intercultural competence in trade negotiations. An interview guide was crafted to address key themes relevant to the research. Each interview lasted between 30 and 45 minutes, with an average duration of 35 minutes. The sample was selected to capture a broad range of perspectives, ensuring diversity in terms of gender, age, and socio-professional categories. The criterion of theoretical saturation was applied, achieving this after interviewing 16 individuals—8 negotiators from masculine cultures and 8 from feminine cultures. The analysis included negotiators from Tunisia (a masculine culture) and France (a feminine culture), providing a cross-country perspective.

3. Finding : All interviews were transcribed and analyzed using Sphinx QII software, which is renowned for its efficiency in computerized qualitative analysis. The content analysis was structured around a thematic grid, revealing the following key insights:

Content Analysis

Intercultural Competence

From the thematic grid, we observe that the most frequently addressed theme by respondents is intercultural competence, with a percentage of 37.5%. Thus, this theme is crucial to this study. Intercultural competence is considered a key element in international negotiation.

All respondents affirm that intercultural competence impacts negotiation outcomes. They believe that adopting these competencies leads to optimal results.

Therefore, based on respondents' answers, it is evident that intercultural competence positively influences the outcomes of intercultural trade negotiations. According to their views, it is considered a success factor in any international negotiation scenario.

However, what can influence this competence and potentially lead to unexpected results is the use of unethical tactics by some negotiators. This leads us to our second theme in this study: the use of unethical tactics by negotiators from different companies.

Unethical Tactics

A consensus on the significance of unethical tactics in intercultural trade negotiations was reported in the respondents' answers. Respondents from both masculine and feminine cultures believe that unethical tactics influence the course and results of international negotiations.

This theme is as significant as the theme of intercultural competence, according to the participants' views on its impact on the course and outcomes of international trade negotiations. This is justified by the percentage allocated to this theme (33.3%).

From the responses of various participants, we can identify the most commonly used unethical tactics in intercultural trade negotiations as: bluffing, information distortion, and inappropriate information gathering.

A classification of unethical tactics used by negotiators in international negotiation situations will be covered in this study.

• Bluffing : Bluffing is the first unethical tactic addressed by participants (26.4%). Some respondents referred to this tactic as false promises. They consider this unethical tactic to be highly prevalent in intercultural trade negotiations and sometimes view its use as "legitimate."

• Information Distortion : We find that the second unethical tactic addressed, with a percentage of 25%, is information distortion. Most negotiators from both masculine and feminine cultures emphasize that this tactic is most commonly used by negotiators to achieve their goals.The tendency of a negotiator to present false information for a specific purpose directly influences international trade negotiations.

• Information Gathering : The third unethical tactic addressed by respondents is inappropriate information gathering (19.4%). The majority of respondents believe that inappropriate information gathering is a notably used unethical tactic in international negotiation situations. They consider this tactic as a tool to achieve well-defined results. Thus, it significantly influences the negotiation process and outcomes.

• Competitive Negotiation Mode : This unethical tactic was mentioned by a minority of respondents. However, it still exists and contributes to influencing the negotiation outcomes.

• Attack on the Opponent’s Network : In order, this unethical tactic is the fifth addressed by some participants who believe that attacking the opponent’s network influences the negotiation. Establishing relationships with the negotiation partner’s network solely to weaken their position in the professional meeting is used by some negotiators.

• Negotiation Outcomes : We observe that negotiation outcomes are of two types: relational outcomes and economic outcomes. All respondents agree that the factors influencing international negotiation outcomes are the negotiator’s intercultural competence and the use of unethical tactics.

• Role of Competence in Negotiation Outcomes : From this study, we have found that the negotiator's intercultural competence significantly contributes to achieving optimal relational and economic outcomes. Therefore, intercultural competence is a crucial element in any negotiation and for all companies, both masculine and feminine. Its importance lies in the value of the results obtained.

• Role of Unethical Tactics in Negotiation Outcomes : Similarly, we have observed the role of unethical tactics used by male and female negotiators in both economic and relational outcomes.

Most interviewees mentioned that unethical tactics contribute to achieving economic gains and profits. They believe that these unethical tactics are used solely for economic purposes such as gain, profit, and monetary benefits. The use of unethical tactics never contributes to achieving relational outcomes. Therefore, negotiators who use bluffing, information distortion, inappropriate information gathering, competitive negotiation mode, and attack on the opponent’s network achieve good economic results but do not focus on maintaining relationships with other negotiating parties.

We conclude that the outcomes of intercultural trade negotiations are influenced by several factors, including the intercultural competence of the negotiator and the use of unethical tactics. These two factors affect both economic and relational outcomes. Moreover, competence positively influences both economic and relational outcomes, while unethical tactics positively influence economic outcomes and negatively influence relational outcomes.

Results and Discussion of Lexical Analysis

The goal of lexical analysis is to highlight the formal characteristics of the corpus, such as its size, richness, and the most frequent words. We present the most frequently mentioned concepts by respondents in a word cloud, with size proportional to occurrence.

We notice that the theme of international negotiation is the most addressed by respondents, indicating that the study context was well-defined by interviewees.

For factors influencing international negotiations, there is a strong presence of unethical tactics such as bluffing and inappropriate information gathering. This factor seems very important to interviewees as it affects negotiation outcomes. According to them, unethical tactics lead to economic results such as gain and profit. In contrast, on the relational level, unethical tactics never contribute to building relationships between negotiators, as evidenced by the jargon used: rupture, end, blockage.

Most respondents agree that the unethical tactic "bluff" is the most used and important in international negotiations. This could be explained by respondents’ belief that the use of bluffing is legitimate in international negotiations. This legitimacy is justified by achieving optimal economic results.

Another theme discussed in depth by respondents is intercultural competence, explained by several words such as aptitude, capacities, and effectiveness. In the word cloud, we also noticed that negotiators come from two different cultures: masculine and feminine.

The data from this study corroborates existing literature on the importance of intercultural competence in negotiations. Previous research, such as (Faure & Rubin, 1983) and (Hofstede, 2003), emphasizes that understanding cultural nuances and maintaining respect for differing cultural values are crucial for successful negotiations. Our findings extend this understanding by demonstrating that high intercultural competence not only fosters better relational outcomes but also contributes to more effective economic results.

In terms of the masculinity/femininity dimension, the study aligns with (Hofstede, 2003) theory, which suggests that masculine cultures prefer assertive and competitive strategies, while feminine cultures value collaboration and empathy. This study adds to the literature by providing empirical evidence of how these cultural traits influence negotiation tactics in specific contexts, such as those involving Tunisian and French negotiators.

The discussion of unethical tactics, particularly bluffing, reveals a notable gap in the literature. While the prevalence of such tactics in both masculine and feminine cultures is documented, the differential perceptions of their acceptability and effectiveness provide new insights. Negotiators from masculine cultures view bluffing as a strategic necessity, whereas those from feminine cultures are more concerned about the ethical implications and potential damage to long-term relationships. This contrast underscores the need for a deeper understanding of how cultural values shape the ethical dimensions of negotiation tactics.

Proposal of the Negotiation Model

Drawing inspiration from commercial negotiation models applied by various researchers such as (Jolibert & Velázquez, 1989; Dupont, 1994), which consist of three blocks of variables, our model takes into account the following:

Masculinity/Femininity: Antecedent Explanatory Variable

The Masculinity/Femininity dimension refers to the extent to which a culture enforces a clear division of social roles between the sexes (Hofstede, 1984; Singh, 2002). It also pertains to the prevalence of "hard" values such as achievement, excellence, and competition, compared to "soft" values like cooperation, solidarity, and empathy (Doney et al. 1998). In a masculine culture, individuals are motivated by self-actualization, excellence, material success, and social advancement. They value opportunistic behavior, competition, and autonomy, and base their decisions on calculated considerations aimed at serving their personal interests, even at the expense of others' well-being (Van de Vliert et al. 1999; Elahee et al., 2002). This emphasis on opportunism and self-interest means that ethical behavior in such a culture can only be based on cognitive processes and rational criteria such as reputation and competence (Kale & Barnes, 1992; Doney et al. 1998). In contrast, feminine cultures instill values of kindness, generosity, and cooperation. Opportunistic behavior is condemned, and collective interest prevails over personal interest. People from such cultures place greater importance on human relationships, mutual assistance, integrity, and honesty, and build their interactions with others based on these values (Hofstede, 1984; Doney et al. 1998; Gefen & Heart, 2006). Thus, feminine cultures' values foster ethical behavior.

Intercultural Competence: Intermediate Dependent Variable

For international negotiation, intercultural competence is essential but extends beyond mere "know-how." Other crucial factors for international success include knowledge of foreign contexts, understanding of socio-political systems, consideration of material constraints, and language skills, etc. (Bartel-Bardic, 2015).

Intercultural competence is the ability to understand and adapt to the specifics of intercultural interactions, notably through empathy, open-mindedness, and emotional stability.

This competence can be achieved through a thorough knowledge of one or two foreign cultures (cultural skills). Possessing this competence facilitates understanding unfamiliar cultures.

Negotiators interacting with different cultures need intercultural competence to achieve their previously set objectives. Negotiation skills are important for reaching agreements in business (Zohar, 2015). The ability to negotiate is valuable for business leaders, as the skills gained through negotiation practice develop critical thinking abilities and effective communication skills.

We measure this variable through the following five dimensions (Bartel-Radic & Giannelloni, 2015).

1. Commitment: The degree of participation in intercultural communication.

2. Trust: The degree of trust the interlocutor has in the opposing party during intercultural communication.

3. Enjoyment in Interaction: The degree of satisfaction experienced by interlocutors in intercultural communication.

4. Attention During Interaction: The ability to receive and respond correctly to messages during intercultural communication.

5. Respect During Interaction: The realization, acceptance, and respect of others' cultural differences in communication.

Bluffing: Moderator Variable

Negotiation follows a process in which the use of strategies is present, and among these strategies, the use of tactics and techniques is almost always present.

Tactics are specific and opportunistic actions aimed at achieving the negotiator’s set goals (Audebert-Lasrochas, 1999). The tactics used range from ethical to unethical, thus negotiators’ behavior can be ethical or unethical.

According to (Lewicki & Robinson, 1998), bluffing or "false promises" manifests in three situations:

1. Promising to make concessions in favor of the other party if they meet your need, even if you are unsure of keeping this promise.

2. Promising future concessions that you do not intend to make, in exchange for concessions from the other party.

3. Assuring that agents will support the agreement, even though you know they are unlikely to approve the agreement as it stands.

Negotiation Outcomes: Dependent Variable

Negotiation outcomes have been measured and conceptualized in various ways. Negotiation outcome measures can be grouped into two categories: economic and relational (Thompson, 1990).

Two important outcome variables will be examined: (1) economic outcomes, and (2) relational or affective outcomes (Negotiator Satisfaction) (Zarrad & Debabi, 2014).

Economic Outcome

Measures of economic outcomes are based on normative models of negotiation behavior that specify how rational and well-informed individuals should behave in competitive situations (Von Neumann & Morgenstern, 1947). It is a dependent variable that measures the negotiator’s ability to use tactics effectively throughout the negotiation process (Barry & Friedman, 1998), while having certain skills that may be useful in particular situations.

Relational Outcome

Satisfaction is the factor that increases the likelihood of establishing and maintaining long-term relationships. It has been associated with functional behaviors in various contexts (Churchill et al. 1990) and is considered a critical measure of exchange relationships (Ruekert & Churchill, 1984). This dependent variable measures the durability of relationships and the maintenance of rapport between negotiators over the long term Figure 1.

Our study builds on the theoretical frameworks of (Simmel, 1980; Weingart et al., 1990), providing a nuanced view of how intercultural competence and cultural dimensions influence negotiation outcomes. By integrating empirical data with these theories, we offer a comprehensive analysis of the interplay between cultural factors and negotiation practices.

The findings highlight the necessity of considering ethical implications in negotiation tactics. While bluffing might offer short-term benefits, it risks long-term relationship damage, particularly in feminine cultures where ethical behavior is highly valued. This aligns with (Lewicki & Stark, 1996) identification of unethical practices but extends it by showing how cultural context affects the perception and impact of these tactics.

For practitioners, the study emphasizes the importance of developing intercultural competence and tailoring negotiation strategies to cultural dimensions. It suggests that negotiators should be aware of the cultural context when choosing tactics and consider the long-term implications of unethical practices. For researchers, the study calls for further investigation into the ethical aspects of negotiation tactics across diverse cultural settings and the application of the theoretical model in various industries.

In summary, this study contributes to the literature by providing empirical evidence of how intercultural competence and cultural dimensions influence negotiation outcomes and ethical behavior. It also identifies areas for future research, particularly in exploring the broader applicability of the theoretical model and understanding the ethical implications of negotiation tactics in different cultural contexts.

Conclusion

This study underscores the critical role of intercultural competence in improving negotiation outcomes in international trade contexts. High levels of intercultural competence allow negotiators to navigate cultural differences more effectively, thereby enhancing both relational and economic success. Additionally, the masculinity/femininity dimension significantly influences negotiation strategies, with masculine cultures favoring assertiveness and competitive tactics, while feminine cultures emphasize collaboration and empathy.

The findings also highlight the prevalence of unethical tactics, such as bluffing, in both masculine and feminine cultures, though their ethical acceptability and effectiveness vary. This disparity underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of how cultural values shape ethical behavior in negotiations. The study advocates for further research into ethical practices and the impact of cultural dimensions on negotiation tactics to refine negotiation strategies in diverse cultural contexts.

Recommendations

1. Enhance Intercultural Competence: Negotiators should prioritize the development of intercultural competence through targeted training and education. Understanding cultural nuances and adapting negotiation strategies to align with the cultural context of counterparts can greatly improve negotiation outcomes. Building trust and managing expectations are essential components of successful negotiations.

2. Consider Ethical Implications: Practitioners should carefully consider the ethical implications of using tactics like bluffing. While such tactics may offer immediate advantages, they can potentially undermine long-term relationships and trust. Emphasizing ethical behavior and transparency is crucial for fostering sustainable and mutually beneficial agreements.

3. Tailor Strategies to Cultural Dimensions: Negotiation strategies should be customized according to the cultural dimensions of the negotiating parties. For instance, in masculine cultures, assertive and competitive strategies may be more effective, whereas in feminine cultures, collaborative and relationship-oriented approaches are likely to yield better results. Understanding these cultural preferences can guide the selection of appropriate negotiation tactics.

4. Incorporate the Theoretical Model: Both researchers and practitioners should leverage the theoretical model developed in this study to enhance their negotiation strategies. This model provides a framework for understanding the interplay between culture, competence, and ethics in intercultural negotiations and can be used to design more effective negotiation processes.

5. Pursue Further Research: Future studies should test the theoretical model across various industries and contexts to assess its robustness and adaptability. Additionally, exploring other unethical tactics and their impact on negotiation outcomes could offer a more comprehensive understanding of ethical behavior in international negotiations.

6. By following these recommendations, organizations and individuals engaged in international negotiations can improve their effectiveness, strengthen cross-cultural relationships, and achieve more favorable outcomes. Further research is needed to validate these findings in different cultural contexts and to explore the moderating role of other intercultural variables, such as power distance and uncertainty avoidance, in shaping negotiation outcomes.

References

Adair, W., Brett, J., Lempereur, A., Okumura, T., Shikhirev, P., Tinsley, C., &Lytle, A. (2004). Culture and negotiation strategy. Negotiation journal, 20(1), 87-111.

Adler, N. J. (1994). Competitive frontiers: Women managing across borders. Journal of Management Development, 13(2), 24-41.

Audebert-Lasrochas, P. (1999). La négociation. Paris, Editions dOrganization, 3éme éd.

Barry, B., & Friedman, R. A. (1998). Bargainer characteristics in distributive and integrative negotiation. Journal of personality and social psychology, 74(2), 345.

Bartel-Radic, A., &Giannelloni, J. L. (2015). Can Cross-Cultural Competence in International Business really be measured through Personality. In VeConférenceAnnuelle ATLASAFMI, Hanoï, Vietnam.

Binnendijk, H. (Ed.). (1987). National negotiating styles. Foreign Service Institute, US Department of State.

Churchill, N. C., & Bygrave, W. D. (1990). The entrepreneurship paradigm (II): chaos and catastrophes among quantum jumps?. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 14(2), 7-30.

Cohen-Émerique, M. (2004). Positionnement et compétences spécifiques des médiateurs. Hommes & Migrations, 1249(1), 36-52.

Debabi, M. (2010). Contribution of cultural similarity to foreign products negotiation. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 17(4), 427-437.

Dellech, D., &Debabi, M. (2017). La négociation interculturelle: défi des approches concurrentes et diversité des paradigmes. Question (s) de management, (4), 67-75.

Doney, P. M., Cannon, J. P., & Mullen, M. R. (1998). Understanding the influence of national culture on the development of trust. Academy of management review, 23(3), 601-620.

Dupont, C. (1994). Domestic politics and international negotiations: a sequential bargaining model. P. Allan and C. Schmidt. Game Theory and International Relations. Cheltam: Elgar Publisher.

Dupriez, P., & Simons, S. (2002). La résistance culturelle: Fondements, applications et implications du management interculturel, 2e éd., Bruxelles, De Boeck, coll. Management.

Elahee, M. N., Kirby, S. L., & Nasif, E. (2002). National culture, trust, and perceptions about ethical behavior in intra‐and cross‐cultural negotiations: An analysis of NAFTA countries. Thunderbird International Business Review, 44(6), 799-818.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Faure, G. O., & Rubin, J. Z. (Eds.). (1983). Culture and negotiation: The resolution of water disputes. Sage.

Gefen, D., & Heart, T. H. (2006). On the need to include national culture as a central issue in e-commerce trust beliefs. Journal of Global Information Management (JGIM), 14(4), 1-30.

Gelfand, M., & Dyer, N. (2000). A cultural perspective on negotiation: Progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Applied Psychology, 49(1), 62-99.

HAMMAMI, H., & DELLECH, D. (2022). For A Better Understanding of Opposing Negotiator Behavior. International Journal of Business & Economics (IJBE), 7(2), 51-79.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture's consequences: International differences in work-related values (Vol. 5). sage.

Hofstede, G. (2003). Cultural dimensions. www. geert-hofstede. com.

Igalens, J., & Roussel, P. (1998). Méthodes de recherche en gestion des ressources humaines. FeniXX.

Jolibert, A., &Velazquez, M. (1989). La négociation commerciale Cadre théorique et Synthèse. Recherche et Applications en Marketing (French Edition), 4(4), 51-70.

Julien, V. I. A. U., Sassi, H., &Pujet, H. (2015). La négociation commerciale. Dunod.

Kale, S. H., & Barnes, J. W. (1992). Understanding the domain of cross-national buyer-seller interactions. Journal of international business studies, 23, 101-132.

Khan, M. A., & Ebner, N. (Eds.). (2019). The Palgrave handbook of cross-cultural business negotiation. Springer International Publishing.

Korobkin, R (2024). Negotiation theory and strategy. Aspen Publishing.ISO 690.

Lewicki, R. J., & Brinsfield, C. T. (2010). 11. Trust, distrust and building social capital. Social capital: Reaching out, reaching in, 275.

Lewicki, R. J., & Robinson, R. J. (1998). Ethical and unethical bargaining tactics: An empirical study. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(6), 665-682.

Lewicki, R. J., & Stark, N. (1996). What is ethically appropriate in negotiations: An empirical examination of bargaining tactics. Social Justice Research, 9, 69-95.

Liang, J. (2022). A New Perspective to Resolve Behavioral Biases in Business Negotiation: Dao. International Negotiation, 1(aop), 1-20.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rees, M. R., Tenbrunsel, A. E., & Bazerman, M. H. (2019). Bounded ethicality and ethical fading in negotiations: Understanding unintended unethical behavior. Academy of Management Perspectives, 33(1), 26-42.

Ruekert, R. W., & Churchill Jr, G. A. (1984). Reliability and validity of alternative measures of channel member satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 21(2), 226-233.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Salacuse, J. W. (1991). Making global deals: Negotiating in the international marketplace. Ticknor & Fields.

Salacuse, J. W. (1998). Ten ways that culture affects negotiating style: Some survey results. Negotiation journal, 14(3), 221-240.

Simmel, G. (1980). Essays on interpretation in social science. Manchester University Press.

Singh, N. (2002). From cultural models to cultural categories: A framework for cultural analysis. Advances in consumer research, 29(1).

Thompson, L. (1990). Negotiation behavior and outcomes: Empirical evidence and theoretical issues. Psychological bulletin, 108(3), 515.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Van de Vliert, E., Nauta, A., Giebels, E., & Janssen, O. (1999). Constructive conflict at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 20(4), 475-491

Von Neumann, J., & Morgenstern, O. (1947). Theory of games and economic behavior, 2nd rev.

Weingart, L. R., Thompson, L. L., Bazerman, M. H., & Carroll, J. S. (1990). Tactical behavior and negotiation outcomes. International Journal of Conflict Management.

Weiss, S. E. (1994). Negotiating with" Romans"-part 1. Sloan Management Review, 35, 51-51.

Zarrad, H., &Debabi, M. (2014). La négociation interculturelle: proposition d’un cadre conceptuel de l’impact de la culture sur la négociation. Congrès trends marketing, Paris.

Zohar, I. (2015). “The art of negotiation” leadership skills required for negotiation in time of crisis. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 209, 540-548.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 04-Oct-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-15313; Editor assigned: 05-Oct-2024, PreQC No. AMSJ-24-15313(PQ); Reviewed: 20-Nov-2024, QC No. AMSJ-24-15313; Revised: 26-Nov-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-15313(R); Published: 14-Dec-2024