Research Article: 2021 Vol: 23 Issue: 6S

Employer Brand and Employee In-Role Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model of Employee's Self- Efficacy and Work Engagement

Mohammad A. Ta’Amnha, German Jordanian University

Omar M. Bwaliez, German Jordanian University

Ihab K. Magableh, Arab Planning Institute

Abstract

This study investigates the relationship between employer brand and employee in -role performance through the mediating role of employee’s work engagement and the moderating role of employee’s self-efficacy. It employs the integrated framework of the job demand- resource model, social exchange theory, and behavioral plasticity theory to explain these relationships. A structured questionnaire was used to collect primary data from 337 employees who work in several humanitarian organizations in Jordan. After checking the questionnaire’s validity and reliability, the research hypotheses were tested using the regression analysis and macro process plugin. The results revealed that there is a direct relationship between employer brand and employee in-role performance, and the employee’s work engagement is a mediator to this direct relationship. Furthermore, the results revealed that this relationship is stronger when an employee’s self-efficacy is low rather than high. The findings of this study pose a framework for humanitarian employees to strengthen their work engagement and in -role performance by offering employer brand activities to those individuals who have a low level of self-efficacy.

Keywords

Employer Brand, Employee In-Role Performance, Self-Efficacy, Work Engagement, Moderated Mediation Model, Humanitarian Organizations, Jordan

Introduction

Employee performance is a key issue that continuously captures the attention of scholars and practitioners (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009). It refers to the job results aimed at by job holders (Motowidlo & Van Scotter, 1994). High employee performance generally leads to achieving the desired organizational results, such as higher productivity and improved customer loyalty (Salanova et al., 2005). Therefore, organizations strive to understand how to improve the performance of their employees to enhance their profitability and sustainability (Al-Tahat & Bwaliez, 2015; Rifai et al., 2021). Employee performance can be divided into two types: in-role performance and extra-role performance (Becker & Kernan, 2003). Employee in-role performance indicates his/her behavior directed toward formal tasks, duties, and responsibilities such as those included in a job description (Williams & Anderson, 1991), while employee extra-role performance indicates the activities that are essential for organizational effectiveness but are discretionary in nature such as acting courteously and helping others (Moorman et al., 1993; Organ, 1988). This study is directed toward the influencers that can affect employee in-role performance only. One of these influencers that are highly neglected in literature is employer brand.

Employer brand is a competitive Human Resource Management (HRM) strategy that is adopted by organizations to promote themselves as attractive workplaces in order to increase the engagement and commitment of their current employees and to enhance their ability to attract highly qualified talents in globalized labor markets (Ta’Amnha, 2020). Employer brand refers to the functional, psychological, and economic values and benefits provided by employing organizations to existing employees which are contemporaneously communicated to potential employees (Ambler & Barrow, 1996). Several empirical investigations found that employer brand has significant impacts on organizational performance (Biswas & Suar, 2016; Tumasjan et al., 2020) since it has positive impacts on employees’ attitudes and behaviors (Arasanmi & Krishna, 2019; Tanwar, 2016). However, employer brand still needs more attention from researchers (Ta’Amnha et al., 2021b), particularly with regard to mechanisms explaining the relationship between employer brand and employee in-role performance. In addition, the exploration of boundary conditions concerning factors that may leverage existing relationships is very limited. This study investigates the effect of two of these factors: self- efficacy and work engagement. Self-efficacy refers to employees’ perceptions of their ability to behave properly and achieve certain tasks effectively (Bandura, 1997), while work engagement refers to a positive, pleasing, and work-related state of mind that exhibits vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al., 2002). In short, this study explores the impact of the employer brand on employee in-role performance, taking into consideration the mediating role of work engagement and the moderating role of self-efficacy.

This study targeted the humanitarian organizations for whom recruiting and retaining highly qualified employees are key challenges faced on an ongoing basis (Korff, 2012; Korff et al., 2015; Loquercio et al., 2006). This is often because the operations of these organizations are often concentrated in high risk and unstable societies and countries (Heyse, 2016). Therefore, workers in these organizations are more likely to experience traumatic experiences, resulting in depression, anxiety, burnout, and vicarious trauma (Curling & Simmons, 2010). Consequently, the issues of wellbeing and turnover rate among humanitarian workers are topics that capture increasing attention. In this study, we aim to provide the literature with the novel idea that employer brand can be operationalized to enhance the engagement of humanitarian workers which leads to enhance their in-role performance. In addition, the significance of this study stems from focusing on the individual differences in the relationships between the job resources (i.e., employer brand) and work engagement. There is a lack of scholarly works dedicated to explaining the role of personal resources (i.e., employee’s self-efficacy) in this relationship. Thus, revealing the interactions between personal and organizational resources comprises a significant contribution to the literature.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the prior literature and hypotheses development. Section 3 presents the research methodology. Section 4 presents the results and discussion. Section 5 presents the conclusion by providing the theoretical and practical implications. Finally, Section 6 presents the limitations and directions of future research.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Theoretical Underpinning

Three underlying theories were used to support the propositions of this research: the Job Demand-Resource (JD-R) model (Bakker et al., 2005), the Social Exchange Theory (SET) (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Homans, 1958), and the Behavioral Plasticity Theory (BPT) (Pierce et al., 1993).

First, the JD-R model is adopted frequently in work engagement, job burnout, and stress investigations. The core of the JD-R model is the proposition that every job has specific risk factors associated with job stress or burnout (Bakker et al., 2005). These factors are grouped into the categories of job demands and job resources studied by the holistic JD-R model, which is designed to be adaptable to explain related issues in diverse occupational settings regardless of the particular associated demands and resources. Bakker, et al., (2005) defined job demands as “physical, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical or mental effort and are therefore associated with certain physiological and psychological costs,” and job resources as “physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that (a) are functional in achieving work goals, (b) reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs, or (c) stimulate personal growth and development.” According to the JD-R model, there are numerous and diverse job resources that represent a buffer for numerous and diverse job demands.

Second, the SET is based on the principle of reciprocity. When employees believe that they receive enough support and resources, they become more satisfied and less stressed which results in improving their organizational performance (Ta’Amnha et al., 2021c). In this study, employer brand represents the resources offered by organizations to their employees, such as training and development opportunities. In return, employees become indebted to their organizations and consequently become more engaged at work. The reciprocity in this relationship is explained by the SET. When employees find that they receive several sorts of support and resources from their organizations, they feel indebted and obliged to offer greater efforts, thus they become highly focused and engaged in their jobs (Bhasin et al., 2019) and more likely to show discretionary behavior (Cole et al., 2002). This leads to higher employee performance and associated improved product quality and services, thereby increasing customer loyalty and satisfaction.

Third, the BPT assumes that the changes in individual behaviors are fundamentally caused by exposure to external stimuli (Pierce et al., 1993). According to the BPT, people with low self-efficacy are more likely to be influenced by workplace conditions and circumstances, more vulnerable to a lack of organizational support, as well as more malleable and affected by increased organizational support (Turban & Keon, 1993). On the other hand, individuals with high levels of self-efficacy are less affected by external influences, more persistent and determined to reach their goals through high levels of engagement, as well as more able to use personal resources to deal with encountered challenges and demands effectively (Liu et al., 2017).

Hypotheses Development

Employer Brand and Employee In-Role Performance

Employer brand is a key HRM strategy that is adopted by organizations to enhance their competitiveness in labor markets. It refers to the functional, psychological, and economic values and benefits provided to the employees and communicated to the potential employees (Ambler & Barrow, 1996). Employer brand reflects the ongoing development in the psychological contract that explains the relationships between employers and their employees (Backhaus & Tikoo, 2004). According to Lievens (2007), employer brand consists of instrumental and symbolic benefits. Instrumental benefits comprise objective and tangible attributes, while symbolic benefits comprise subjective and intangible attributes. Recently, employer brand has come to be viewed from a broader, institutional perspective, as:

“An ongoing progressive institution that comprises several sorts of desirable experiences and outcomes that are communicated to both existing and potential employees, by which the employing company distinguishes itself from competitors, and at the same time, they give the firm the legitimacy to compete in the labor market over the highly qualified talents” (Ta'Amnha, 2020).

Ta'Amnha (2020) conceptualized the three institutional pillars of regulative, Professional, and cultural-cognitive domains (Scott, 2008) to institutionalize employer brand in entrepreneurial enterprises. Employer brand represents a profitable long-term investment, with significant impacts on organizational performance (Biswas & Suar, 2016; Kashive & Khanna, 2017; Robertson & Khatibi, 2013; Tumasjan et al., 2020). This is because it enables organizations to recruit and maintain highly qualified talents who contribute significantly to their organizational results. Moreover, employer brand has major influences on employees’ attitudes and perceptions. Employer brand is positively correlated with organizational commitment (Arasanmi & Krishna, 2019; Tanwar, 2016), job satisfaction (Buttenberg, 2013; Fasih et al., 2019; Kaur et al., 2020), organizational citizenship behavior (Buttenberg, 2013), and employee voice (Ta’Amnha et al., 2021a). However, it is negatively related to employees’ turnover intention (Kashyap & Rangnekar, 2016; Kashyap & Verma, 2018; Lelono & Martdianty, 2013). Hence, the employer brand has positive influences on the performance of the employees due to its ability to recruit highly qualified employees, and because it promotes positive attitudes, behaviors, and cultures in organizations. Capitalizing on the previous discussion, the following hypothesis has emerged:

H1: Employer brand has a positive relationship with employee in-role performance.

Mediating Role of Work Engagement

Employer Brand and Work Engagement

Work engagement is one of the key attitudinal subjects that have been capturing the attention of scholars and practitioners for two decades (Carasco-Saul et al., 2015; Saks, 2019). It is defined as a “positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (Schaufeli et al., 2002), whereby:

“Vigor involves high levels of energy and mental resilience while working; dedication refers to being strongly involved in one’s work and experiencing a sense of significance, enthusiasm, and challenge; and absorption refers to being fully concentrated and engrossed in one’s work” (Saks, 2019).

Employer brand values, such as economic, social, training, and development dimensions can positively influence work engagement. Employer brand involves several types of employer resources provided to employees that enable the latter to execute their job demands more effectively. According to the JD-R model, employer brand is the key determinant of work engagement, since it offers job resources to employees that enable them to be highly energized in their jobs and buffers them from surrounding stressors. According to the SET’s explanations and assumptions (Saks, 2006), this is because employees who perceive that their employers recognize their contributions and provide them with different types of support feel more obligated to their organizations and reciprocate by showing a higher level of engagement. Several empirical studies demonstrated that there is a strong relationship between employer brand and work engagement. For instance, Lee, et al., (2014) employed the SET to reveal that internal branding activities were critical to improving the engagement level among hotel employees in South Korea thereby leading to enhanced job satisfaction. In addition, Morya & Yadav (2017) found that internal employer branding has a positive impact on work engagement among hotel employees in India through enhancing employee commitment and loyalty. They recommended that hotel management should invest more in employer branding activities to ensure the engagement of their employees and ultimately enhance profitability. Davies et a l. (2018) found that the more positive employee views are of their employer’s image, the greater their engagement. Bhasin, et al., (2019) found that employer brand has a significant impact on job and organization engagement. Based on the aforementioned arguments, the following hypothesis should be tested:

H2a: Employer brand has a positive relationship with work engagement.

Work Engagement and Employee In-Role Performance

Engaged workers are often fully immersed in their work whereby they perceive that time flies (Bakker et al., 2012). Work engagement is a key factor that positively affects the performance and productivity of organizations and employees. Based on a sample of employees from various occupations, Bakker, et al., (2012) found that work engagement is positively related to task performance. In addition, Ghafoor, et al., (2011) found a significant relationship between work engagement practices and employee performance based on data collected from a sample of employees and managers of telecom companies. Bakker & Bal (2010) studied a sample of Dutch teachers and found that levels of autonomy, exchange with supervisors, and opportunities for development are positively related to engagement, which in turn is positively related to job performance on a weekly basis. Moreover, momentary work engagement is positively related to job resources in the subsequent week. These findings show how intra-individual variability in employees’ experiences at work can explain weekly job performance.

In addition, Halbesleben & Wheeler (2008) found that engagement affects employee in-role performance and intention to leave of employees. Salanova, et al., (2005) found that work engagement predicts service climate, which in turn predicts employee performance and customer loyalty, which is subsequently reflected in sales volume and profitability. Lisbona, et al., (2018) found that work engagement leadsto a higher personal initiative of employees, which in turn leads to higher employee performance. Buil, et al., (2019) found that work engagement fully mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and organizational citizenship behaviors, whereas engagement partially mediates the link between transformational leadership and job performance. Results also indicated a sequential mediation effect of identification and engagement on employee performance. Based on the aforementioned arguments, the following hypothesis should be tested:

H2b: Work engagement has a positive relationship with employee in-role performance.

Moderating Role of Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy refers to individuals’ perceptions of their ability to behave properly and

Achieve certain tasks effectively (Bandura, 1997). Self-efficacy reflects the core component of self-regulatory behavior in social cognitive theory, and it is considered to be constructed based on individuals’ previous experiences of achievement (Kim et al., 2008). Self -efficacy is distinguished from similar personality traits (i.e., self -confidence and self-esteem) in that it is “more specific, more readily developed, and much stronger predictor of how effectively people will perform a given task” (Heslin & Klehe, 2006). Evidently, self -efficacy is a significant factor positively affecting individuals’ career success (Ng et al., 2005; Valcour & Ladge, 2008). Kim, et al., (2014) indicated that career decision self -efficacy mediated the relationship between career engagement and career decision certainty.

Xanthopoulou, et al., (2009) investigated how daily fluctuations in job resources (autonomy, coaching, and team climate) are related to employees’ levels of personal resources (self-efficacy and optimism) and work engagement. The analyses revealed that day-level job resources have an effect on work engagement through day-level personal resources. Lisbona, et al., (2018) found that work engagement and self-efficacy lead to a higher personal initiative of employees, which in turn leads to higher employee performance. These results can be interpreted as self-efficacy reflects people’s perceptions and beliefs in their abilities to achieve certain tasks. In other words, it reflects self -evaluation according to self-agreement and standards of desirable achievement that employees seek to attain, which can be clearly noted from their satisfaction with actual results. People with high levels of self-efficacy have more personal resources that are reflected in their higher levels of confidence, optimism, and assertiveness. Therefore, we expect that high levels of personal and job resources can enhance work engagement and employee in-role performance as presented in the following hypothesis:

H3: Self-efficacy moderates the indirect relationship between employer brand and employee in-role performance via work engagement.

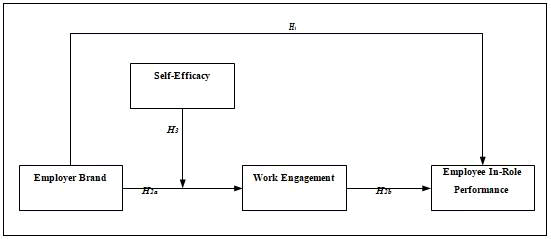

Research Model

A theoretical research model that combines all of the previously proposed hypotheses is shown in Figure 1. The model includes employer brand as an independent variable, employee in-role performance as a dependent variable, work engagement as a mediator, and self-efficacy as a moderator. To the best of our knowledge, this model is the first framework that suggests the mediating effect of work engagement on the direct relationship between employer brand and employee in-role performance, as well as the moderating effect of self- efficacy on the indirect relationship between employer brand and employee in -role performance via work engagement.

Methodology

Questionnaire’s Measures

To empirically test the research model, a structured questionnaire was developed. This questionnaire comprised several measurement items about each research variable (i.e., employer brand, employee in-role performance, work engagement, and self-efficacy) adopted from the published literature. Employer brand was measured using 23 items taken from Tanwar & Prasad (2017). These items were adopted because they are comprehensive and cover different aspects of employer brand and were originally developed to be distributed to employees from humanitarian organizations. Employee in-role performance was measured using six items taken from Becker & Kernan (2003). Work engagement was measured using 17 items adopted from Schaufeli & Bakker (2003). Finally, self -efficacy was measured using four items adopted from Lachman & Weaver (1998). All questionnaire items were chosen such that they achieved high Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient values in their original studies, which means that they had a high level of internal consistency reliability. Table 1 shows the final list of these items. Respondents were asked to indicate their degree of agreement with each one of these items on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

| Table 1Construct Validity and Reliability Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|

| Construct (source)/item description | Factor loading | Validity andreliability |

| Employer brand (Tanwar & Prasad, 2017) | ||

| My organization provides autonomy to its employees to takedecisions. | 0.61 | CFI=0.96; IFI=0.92; TLI=0.93; RMSEA=0.03; AVE= 0.62; Cronbach’sα= 0.94; CR=0.86 |

| My organization offers opportunities to enjoy a groupAtmosphere. | 0.70 | |

| I have friends at work who are ready to share my responsibility at work in my absence. | 0.88 | |

| My organization recognizes me when I do good work. | 0.76 | |

| My organization offers a relatively stress-free work environment. | 0.66 | |

| My organization offers opportunity to work in teams. | 0.79 | |

| My organization provides us online training courses. | 0.80 | |

| My organization organizes various conferences, workshops, and training programs on regular basis. | 0.65 | |

| My organization offers opportunities to work on foreignprojects. | 0.71 | |

| My organization invests heavily in training and development of its employees. | 0.86 | |

| Skill development is a continuous process in my organization. | 0.90 | |

| My organization communicates clear advancement path for itsemployees. | 0.82 | |

| My organization provides flexible-working hours. | 0.74 | |

| My organization offers opportunity to work from home. | 0.64 | |

| My organization provides on-site sports facility. | 0.83 | |

| My organization has fair attitude towards employees. | 0.63 | |

| Employees are expected to follow all rules and regulations. | 0.79 | |

| Humanitarian organization gives back to the society. | 0.84 | |

| There is a confidential procedure to report misconduct at work. | 0.68 | |

| In general, the salary offered by my organization is high. | 0.92 | |

| My organization provides overtime pay. | 0.77 | |

| My organization provides good health benefits. | 0.84 | |

| My organization provides insurance coverage for employees and dependents. | 0.91 | |

| Employeein-role performance (Becker & Kernan, 2003) | ||

| Our employees adequately complete assigned duties. | 0.87 | CFI=0.91; IFI=0.94; TLI=0.93;RMSEA=0.02; AVE= 0.51; Cronbach’sα= 0.84; CR=0.79 |

| Our employees meet formal performance requirements of the job. | 0.84 | |

| Our employees fulfill responsibilities specified in the job description. | 0.83 | |

| Our employees engage in activities that can positively affect their performance evaluation. | 0.79 | |

| Our employees perform tasks that are expected of them. | 0.84 | |

| Our employees consistently perform work tasks in a high quality manner. | 0.91 | |

| Work engagement (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003) | ||

| At my work, I feel bursting with energy. | 0.89 | CFI=0.99; IFI=0.98; TLI=0.92; RMSEA=0.04; AVE= 0.59; Cronbach’sα= 0.9; CR=0.88 |

| I find the work that I do full of meaning and purpose. | 0.90 | |

| Time flies when I am working. | 0.68 | |

| At my job, I feel strong and vigorous. | 0.84 | |

| I am enthusiastic about my job. | 0.87 | |

| When I am working, I forget everything else around me. | 0.83 | |

| My job inspires me. | 0.92 | |

| When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work. | 0.94 | |

| I feel happy when I am working intensely. | 0.87 | |

| I am proud of the work that I do. | 0.88 | |

| I am immersed in my work. | 0.68 | |

| I can continue working for very long periods at a time. | 0.69 | |

| To me, my job is challenging. | 0.71 | |

| I get carried away when I am working. | 0.73 | |

| At my job, I am very resilient, mentally. | 0.89 | |

| It is difficult to detach myself from my job. | 0.85 | |

| At my work I always persevere, even when things do not gowell. | 0.81 | |

| Self-efficacy (Lachman & Weaver, 1998) | ||

| I can do just about anything I really set my mind to. | 0.91 | CFI=0.93; IFI=0.98; TLI=0.97;RMSEA=0.05; AVE= 0.57; Cronbach’sα= 0.79; CR=0.80 |

| When I really want to do something, I usually find a way tosucceed at it. | 0.79 | |

| Whether or not I am able to get what I want is in my ownhands. | 0.86 | |

| What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me. | 0.89 | |

Research Sample

The constructed questionnaire was used to collect primary data from employees who work in humanitarian organizations in Jordan during the period between October 2020 and March 2021. Several humanitarian organizations in Jordan were contacted and they were invited to voluntarily participate in this study with an explanation of the purpose and need for this study. As a result, 12 organizations responded such that 356 questionnaires were received out of 550 distributed questionnaires. After eliminating the questionnaires with missing responses, the final sample comprised 337 usable questionnaires representing a response rate of 61.3%. This response rate is comparable to several previous empirical studies conducted in Jordan and used a similar distribution method (e.g., Al-Tahat & Bwaliez, 2015; Bwaliez & Abushaikha, 2019; Sharabati et al., 2020; Rifai et al., 2021; Ta’Amnha et al., 2021a; 2021c).

Assessment of the Common Method Variance (CMV)

Since a single questionnaire was collected from a single person at a single point in time, there was potential for the Common Method Variance (CMV) problem. This problem might be a threat to the validity of our results. We conducted the Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003) to ensure that no one general factor accounted for the majority of covariance between the predictor and criterion variables. Factors with eigenvalues greater than one showed a 73.4% total variance, and the first factor explained 35.8% of the total variance. This suggests that there is no CMV problem.

Questionnaire’s Validity and Reliability

The questionnaire’s measures were translated from English into Arabic and then Checked using back-translation to ensure conceptual equivalence (Brislin, 1980). The resulting Questionnaire was reviewed by four academics in the field of HRM, as well as four managers from different humanitarian organizations in Jordan. Thereafter, some modifications were made according to their notes and suggestions in order to improve the understanding of the questionnaire’s content. As a result, the content validity of the questionnaire was ensured.

Thereafter, the construct validity was checked by assessing the unidimensionality, Convergent validity, and discriminant validity. The one-dimensionality of the main constructs (i.e., employer brand, employee in-role performance, work engagement, and self-efficacy) was assessed by conducting a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). We conducted CFA by checking four key indices: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), The Incremental Fit Index (IFI), the Tucker- Lewis Index (TLI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Table 1 shows that CFI, IFI, and TLI values are greater than the recommended cut-off value of 0.9, and the RMSEA is less than the recommended cut-off value of 0.05 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Convergent validity was assessed by finding the factor loading for each individual Questionnaire’s item and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each main construct. Table 1 shows that all items in their respective constructs have statistically significant (p<0.01) factor loadings that are greater than 0.50, which suggest convergent validity of the constructs (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Furthermore, the AVE for each construct exceeds the recommended minimum value of 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), which indicates strong convergent validity.

Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the AVE value for each construct with the squared correlation between that construct and other constructs. Table 2 shows that the AVE values for all the constructs were greater than the squared correlation with all other constructs. Thus, we can assume strong discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

| Table 2 Mean, Standard Deviation, Correlations, And Ave Among the Research Variables |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research variable | Mean | SD | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1 | Employer brand | 3.63 | 0.71 | 0.621 | (0.79) | |||

| 2 | Employee in-role performance | 4.18 | 0.36 | 0.510 | 0.27** | (0.71) | ||

| 3 | Work engagement | 4.00 | 0.56 | 0.593 | 0.49** | 0.40** | (0.77) | |

| 4 | Self-efficacy | 4.03 | 0.65 | 0.573 | 0.36** | 0.37** | 0.43** | (0.76) |

| Note: n=337, **p<0.01, Square root of AVE is in parentheses. | ||||||||

Reliability was assessed by finding the Cronbach’s α coefficient and Composite Reliability (CR) (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016; Hair et al., 2017). Table 1 shows that the Cronbach’s α and CR are greater than the recommended cut-off value of 0.7 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2017).

Results and Discussion

Hypotheses Testing

Testing the Relationship between Employer Brand and Employee In-Role Performance

Multiple regressions was used to test the first hypothesis (H1) that propose a direct relationship between employer brand and employee in-role performance. Table 3 shows the regression statistics between employer brand (independent variable) and employee in -role performance (dependent variable). The r-value is 0.268, which means that there is a positive relationship between employer brand and employee in-role performance. Moreover, the coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.072, which means that 7.2% of the variability in employee in-role performance variable is explained by employer brand. Additionally, the regression statistics (F=14.166, p<0.01) indicates that the first hypothesis (H1) is supported. Therefore, the employer brand has an effect on employee in-role performance at the 0.01 level of significance

| Table 3 Regression Statistics of Employer Brand Against Employee In-Role Performance |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | R2 | Adjusted R2 | F-value | Sig. |

| 0.268 | 0.072 | 0.067 | 14.166 | 0.000 |

Table 4 shows the regression between employer brand (independent variables) and employee in-role performance (dependent variable). It is clear from this table that employer brand (t=3.764, p<0.01) has a positive and significant effect on employee in-role performance at the 0.01 level of significance. This indicates that humanitarian workers in Jordan believe that employer brand can affect employee in-role performance.

| Table 4 Regression Model of Employer Brand Against Employee In-Role Performance |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | ||||

| Model | B | Standard Error | β-value | t-value | Sig. |

| (Constant) | 3.697 | 0.132 | 28.002 | 0.000 | |

| Employer brand | 0.134 | 0.036 | 0.268 | 3.764 | 0.000 |

Testing the Mediating Effect of Work Engagement

Hierarchical regression analysis was used to test this hypothesis. Table 5 shows that employer brand significantly affects employee in-role performance, as shown in the data of model 1, and it shows that work engagement mediates the relationship between employer brand and employee in-role performance, as shown in the data of model 2 (ΔR2=0.097, ΔF=21.340, p<0.001). Therefore, it can be concluded that the second hypothesis (H2) is supported.

| Table 5 Results of Hierarchical Regression Analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: Employee in-role performance | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

| b | SE | b | SE | |

| Employer brand | 0.134* | 0.0360 | 0.044 | 0.039 |

| Work engagement | 0.229* | 0.050 | ||

| R2 | 0.072* | 0.169* | ||

| ΔR2 | 0.097* | |||

| ΔF | 21.340* | |||

| Notes: n=337, b is unstandardized regression coefficients. SE is standard error, *p< 0.001. | ||||

Testing the Moderating Effect of Self-Efficacy

Macro process plugin was used to estimate the impact of employer brand on employee in-role performance with the mediating effect of work engagement and the moderating effect of self-efficacy using SPSS Process Macro Model 7 (Preacher, Rucker & Hayes, 2007) with 95% confidence interval. Table 6 shows the regression of the mediation factor (work engagement) onto self-efficacy, employer brand, and their interaction. It shows that the interaction between employer brand and self -efficacy is statistically significant (b=-0.1022; SE=0.0485; p<0.05), suggesting that self-efficacy moderates the effect of employer brand on work engagement.

| Table 6 Regression Results of Process Analysis |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: Work engagement | |||||||||||

| Model Summary | |||||||||||

| R | R-sq | MSE | F | df1 | df2 | p | |||||

| 0.5794 | 0.3357 | 0.2136 | 30.4917 | 3.0000 | 181.0000 | 0.0000 | |||||

| Model | |||||||||||

| coeff | se | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | ||||||

| Constant | 4.0170 | 0.0349 | 115.1298 | 0.0000 | 3.9481 | 4.0858 | |||||

| Employer brand | 0.2999 | 0.0515 | 5.8270 | 0.0000 | 0.1984 | 0.4015 | |||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.2102 | 0.0594 | 3.5360 | 0.0005 | 0.0929 | 0.3275 | |||||

| Int_1 | -0.1022 | 0.0485 | -2.1083 | 0.0364 | -0.1978 | -0.0066 | |||||

| Product Terms Key: | |||||||||||

| Int_1: | Employer brand * Self-efficacy | ||||||||||

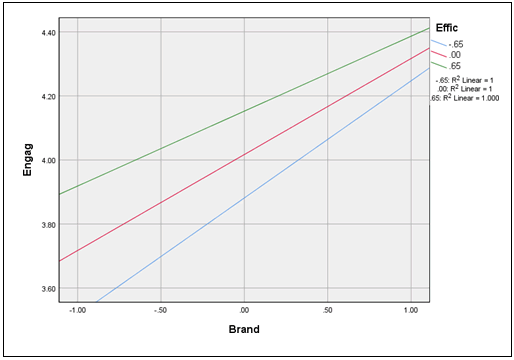

The simple slopes of the relationship between employer brand and work engagement at three points along the scale of the moderator (self -efficacy) are shown in Figure 2 and Table 7. The conventional “pick-a-point” approach is used. At low level of self -efficacy (one standard deviation below the mean (-1SD); R2=-0.65), the effect of employer brand is positive and significant with b=0.3658, SE=0.0570, p <0.001. At the mean level of self-efficacy (on the average; R2=0.00), the effect of employer brand is positive and significant with b=0.2999, SE=0.0515, p<0.001. While, at high level of self-efficacy (one standard deviation above the mean (+1SD); R2=+0.65), the effect of employer brand is positive and significant with b=0.2340, SE=0.0633, p <0.001. Hence, we found that self-efficacy moderates the relationship between employer brand and work engagement, such that this relationship is stronger when self-efficacy is low rather than high. This means that the impact of employer brand on employee in-role performance is also stronger when self-efficacy is low rather than high.

Figure 2: Conditional Indirect Effects of Employer Brand on Employee In-Role Performance Via Work Engagement At High and Low Levels of Self –Efficacy

| Table 7 Conditional Effects of The Focal Predictor At Different Values Of The Moderator |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| -0.6450 | 0.3658 | 0.0570 | 6.4163 | 0.0000 | 0.2533 | 0.4784 |

| 0.0000 | 0.2999 | 0.0515 | 5.8270 | 0.0000 | 0.1984 | 0.4015 |

| 0.6450 | 0.2340 | 0.0633 | 3.6992 | 0.0003 | 0.1092 | 0.3589 |

In addition, Table 8 shows the regression of employee in-role performance onto work engagement (mediator), indicating that work engagement is a positive and significant predictor of employee in-role performance (p<0.001).

| Table 8 Regression of Employer Brand on Employee In-Role Performance Via Work Engagement As A Mediator |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable: Employee in-role performance | ||||||

| Model Summary | ||||||

| R | R-sq | MSE | F | df1 | df2 | p |

| 0.4114 | 0.1693 | 0.1073 | 18.5404 | 2.0000 | 182.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Model | ||||||

| Coeff | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Constant | 3.2697 | 0.1996 | 16.3829 | 0.0000 | 2.8759 | 3.6635 |

| Employer brand | 0.0444 | 0.0390 | 1.1379 | 0.2567 | -0.0326 | 0.1215 |

| Workengagement | 0.2288 | 0.0495 | 4.6196 | 0.0000 | 0.1311 | 0.3265 |

On the other hand, the output shown in Table 9 provides an omnibus test of the conditional indirect effect reflected in the index of the moderated mediation of the effect of employer brand on employee in-role performance (Preacher, Rucker & Hayes, 2007). If zero does not fall between the lower and upper limit of the 95% confidence interval, we infer that the indirect effect is conditional on the level of the moderator variable (self -efficacy). Therefore, it is inferred that self-efficacy significantly moderates the indirect effect of employer brand on employee in-role performance.

Since the index of moderated mediation is statistically significant, then we probe the conditional effects. Table 9 shows the conditional indirect effect of employer brand on employee in-role performance. There are indirect effects at low level (-1SD), the mean level, and high level (+1SD) of the self-efficacy variable. All three indirect effects are positive (at - 1SD, Effect=0.0837; at the mean, Effect=0.0686; and at +1SD, Effect=0.0535) and significant, as the zero does not fall between the lower and upper limit of the 95% confidence intervals for each effect. In short, these results support the third hypothesis (H3) which posited that self-efficacy moderates the indirect effect of employer brand on employee in -role performance via work engagement.

| Table 9 Direct and Conditional Indirect Effects of Employer Brand on Employee In -Role Performance and the Index Of Moderated Mediation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect of Employer brand on Employee in-role performance | |||||

| Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| 0.0444 | 0.0390 | 1.1379 | 0.2567 | -0.0326 | 0.1215 |

| Conditional Indirect Effects of Employer brand on Employee in-role performance | |||||

| Employer brand -> Work engagement -> Employee in-role performance | |||||

| Self-efficacy | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |

| -0.6450 | 0.0837 | 0.0211 | 0.0480 | 0.1312 | |

| 0.0000 | 0.0686 | 0.0175 | 0.0372 | 0.1064 | |

| 0.6450 | 0.0535 | 0.0180 | 0.0207 | 0.0925 | |

| Index of Moderated Mediation | |||||

| Index | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | ||

| Self-efficacy | -0.0234 | 0.0137 | -0.0593 | -0.0041 | |

Employer brand is an important job resource that enables the employees to deal with challenging environments and meet their job requirements effectively. In addition, self -efficacy refers to people’s confidence in achievements. It has been conceived as an important personal resource to successfully have more control over their surrounding environments and reach their personal and organizational goals. Thus, the variety of resources that employees receive from their organizations enable and encourage them to exert more effort in their jobs, rendering them more able and enthusiastic to cope with job requirements and stress more effectively.

The results of this study support the integration between the considered theories. They correspond with previous research that is grounded by the JD-R, SET, and BPT in the essential conclusion that job resources (represented by employer brand) enhance work engagement. When employees receive economic and socio-emotional resources such as training and development as well as instrumental and symbolic benefits, they feel acknowledged and valued within their organization. As the SET proposes, employees feel indebted to repay their organizations by putting more effort into their roles and showing high levels of engagement that leads to enhanced performance (Bhasin et al., 2019; Saks, 2006). In addition, personal resources (represented by self-efficacy) boost such engagement, which results in enhancing not only the in-role performance of employees but also the performance of the ultimate organization.

Conclusion

Theoretical implications

Previous studies have found that employer brand has a significant impact on employees’ attitudes and performance, and more recent research has focused on understanding how personality characteristics boost these relationships. The current study adds more insights by investigating the relationships between employer brand, employee’s work engagement, self- efficacy, and in-role performance. It contributes to the literature by identifying that in the relationship between employer brand and employee in-role performance, work engagement is a key mediator and self-efficacy is a key moderator. In short, this study found that employer brand affects employee in-role performance both directly and indirectly via work engagement as a mediator. Moreover, this study revealed that self-efficacy has a moderating effect on the relationship between the employer brand and work engagement, as well as it has a moderating effect on the indirect relationship between employer brand and employee in-role performance via work engagement. According to the level of employee’s self-efficacy, the employer brand differently influences the relationship between employer brand and employee in-role performance via work engagement. This study found that the relationship between employer brand and work engagement is stronger when employee’s self -efficacy is low rather than high. In addition, it found that the impact of employer brand on employee in-role performance is stronger when employee’s self-efficacy is low rather than high. This means that the resources offered through employer brand activities compensate for the lack of personal resources of self- efficacy that in turn enhance employees’ work engagement and in-role performance.

In other words, this study affirmed the role of self-efficacy as a significant boundary condition of the relationship between employer brand and work engagement. It also suggested that employees can supplement their personal resources (represented by employee’s self- efficacy) with organizational resources (offered by employer brand benefits and experiences) to strengthen the impact of work engagement on employee in-role performance. Furthermore, this study adds to the literature by highlighting that work engagement and employee in -role performance arise from the interplay between the influences of both work environment (represented by employer brand) and personal traits (represented by employee’s self-efficacy). Thus, the interaction between the person-environment is critical in explaining work engagement and employee in-role performance.

Practical Implications

The findings of this study have several practical implications for the field of HRM in the context of humanitarian organizations. First, organizations can increase their employees’ in-role performance by getting them more engaged in their work. As found in the current study, to improve employees’ work engagement, organizations need to create and maintain a strong employer brand that leads to enhance the attractiveness of their workplaces by providing positive social life options, offering numerous and diverse training opportunities to employees, as well as offering them attractive compensation and benefits packages.

Second, the findings of this study suggest that humanitarian organizations should acknowledge and value their workers’ self -efficacy and offer support to enhance it. These organizations can focus on two sources of self-efficacy: verbal persuasion and vicarious modeling (Schunk et al., 2012). Verbal persuasion can be achieved by offering professional training and development programs that can significantly improve employees’ confidence and self-efficacy. Vicarious modeling can be achieved by assigning mentors and establishing role models such as team leaders who exemplify highly self -efficacious behaviors. Humanitarian organizations can also offer ongoing encouragement and emotional support to employees by listening to their voices. Aside from developing all employees’ self -efficacy, humanitarian organizations should also consider self -efficacy as a priority in their recruitment process through employee selection interviews and by asking candidates to take self-efficacy tests. This will gather personnel who are more engaged and better performers.

Limitations and Directions of Future Research

There are several limitations of this study that should be considered in future research. First, this study only used humanitarian agency employees in Jordan as a research sample, which is not wide enough to validate and generalize the explanation of the relationships between research variables. Future researchers can include other employees from other industries and countries. Second, this study used a cross-sectional design in which the relationships between research variables studied at a specific period of time. Future researchers can use a longitudinal design to study the change in the relationships between researches variables over a longer period of time. Third, unlike the current study that took work engagement and self-efficacy into consideration to understand the indirect relationship between employer brand and employee in-role performance, future researchers can conduct more research to explore the effect of other personal resources and individual differences such as age and gender.

References

- Al-Tahat, M.D., & Bwaliez, O.M. (2015). Lean-based workforce management in Jordanian manufacturing firms. International Journal of Lean Enterprise Research, 1 (3), 284- 316.

- Ambler, T., & Barrow, S. (1996). The employer brand. Journal of Brand Management, 4(3), 185–206.

- Anderson, J.C., & Gerbing, D.W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

- Arasanmi, C.N., & Krishna, A. (2019). Employer branding: Perceived organizational support and employee retention – the mediating role of organisational commitment. Industrial and Commercial Training, 51(3), 174–183.

- Alrabei, A.M. (2021). The influence of accounting information systems in enhancing the efficiency of internal control at Jordanian commercial banks. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 24(1), 1-9.

- Al-Amaren, E.M., & Che, I., & Mohd, N. (2020). The blockchain revolution: A game- changing in letter of credit (l/C). International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(3), 6052–58.

- Al Amaren, E.M., & Indriyani, R. (2019). Appraising the law of wills in a contract. Hang Tuah Law Journal, 3(1), 46-58.

- Backhaus, K., & Tikoo, S. (2004). Conceptualizing and researching employer branding. Career Development International, 9(5), 501–517.

- Bakker, A.B., & Bal, M.P. (2010). Weekly work engagement and performance: A study among starting teachers. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(1), 189–206.

- Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., & Euwema, M.C. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10), 170–180.

- Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., & Lieke, L. (2012). Work engagement, performance, and active learning: The role of conscientiousness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 555– 564.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. London: Macmillan.

- Becker, T.E., & Kernan, M.C. (2003). Matching commitment to supervisors and organizations to in-role and extra-role performance. Human Performance, 16(4), 327–348.

- Bhasin, J., Mushtaq, S., & Gupta, S. (2019). Engaging employees through employer brand: An empirical evidence. Management and Labour Studies, 44(4), 417–432.

- Biswas, M.K., & Suar, D. (2016). Antecedents and consequences of employer branding. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(1), 57–72.

- Brislin, R. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material In Triandis HC & Berry JW (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychological: Col. 2. Methodology (389-444). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Buil, I., Martínez, E., & Matute, J. (2019). Transformational leadership and employee performance: The role of identification, engagement and proactive personality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77, 64–75.

- Buttenberg, K. (2013). The impact of employer branding on employee performance. In New Challenges of Economic and Business Development – 2013 (115–123). Riga, Latvia: University of Latvia.

- Bwaliez, O.M., & Abushaikha, I. (2019). Integrating the SRM and lean paradigms: The constructs and measurements. Theoretical Economics Letters, 9(7), 2371-2396.

- Carasco-Saul, M., Kim, W., & Kim, T. (2015). Leadership and employee engagement: Proposing research agendas through a review of literature. Human Resource Development Review, 14(1), 38–63.

- Cole, M.S., Schaninger, W.S.Jr., & Harris, S.G. (2002). The workplace social exchange network: A multilevel, conceptual examination. Group & Organization Management, 27(1), 142–167.

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M.S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900.

- Curling, P., & Simmons, K.B. (2010). Stress and staff support strategies for international aid work. Intervention, 8(2), 93–105.

- Davies, G., Mete, M., & Whelan, S. (2018). When employer brand image aids employee satisfaction and engagement. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 5(1), 64–80.

- Fasih, S.T., Jalees, T., & Khan, M.M. (2019). Antecedents to employer branding. Market Forces, 14(1), 81–106.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

- Ghafoor, A., Qureshi, T.M., Khan, M.A., & Hijazi, S.T. (2011). Transformational leadership, employee engagement and performance: Mediating effect of psychological ownership. African Journal of Business Management, 5(17), 7391–7403.

- Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), (2nd edition). Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Halbesleben, J.R., & Wheeler, A.R. (2008). The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work & Stress, 22(3), 242–256.

- Heslin, P.A., & Klehe, U.C. (2006). Self-efficacy. In: S. G. Rogelberg (Ed.), Encyclopedia of industrial/organizational psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Heyse, L. (2016). Choosing the lesser evil: Understanding decision making in humanitarian aid NGOs. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Homans, G.C. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63(6), 597–606.

- Hu, L.T., & Bentler, P.M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

- Kashive, N., & Khanna, V.T. (2017). Building employee brand equity to influence organization attractiveness and firm performance. International Journal of Business and Management, 12(2), 207–219.

- Kashyap, V., & Rangnekar, S. (2016). Servant leadership, employer brand perception, trust in leaders and turnover intentions: A sequential mediation model. Review of Managerial Science, 10(3), 437–461.

- Kashyap, V., & Verma, N. (2018). Linking dimensions of employer branding and turnover intentions. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 26(2), 282–295.

- Kaur, P., Malhotra, K., & Sharma, S.K. (2020). Employer branding and organisational citizenship behaviour: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, 16(2), 122–131.

- Kim, B., Jang, S.H., Jung, S.H., Lee, B.H., Puig, A., & Lee, S.M. (2014). A moderated mediation model of planned happenstance skills, career engagement, career decision self-efficacy, and career decision certainty. The Career Development Quarterly, 62(1), 56–69.

- Kim, S., Mone, M.A., & Kim, S. (2008). Relationships among self-efficacy, pay-for-performance perceptions, and pay satisfaction: A Korean examination. Human Performance, 21, 158–179.

- Korff, V.P. (2012). Between cause and control: Management in a humanitarian organization. Groningen, Netherlands: University of Groningen.

- Korff, V.P., Balbo, N., Mills, M., Heyse, L., & Wittek, R. (2015). The impact of humanitarian context conditions and individual characteristics on aid worker retention. Disasters, 39(3), 522–545.

- Lachman, M.E., & Weaver, S.L. (1998). The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 763–773.

- Lee, Y.-K., Kim, S., & Kim, S.Y. (2014). The impact of internal branding on employee engagement and outcome variables in the hotel industry. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 19(12), 1359–1380.

- Lelono, A., & Martdianty, F. (2013). The effect of employer brand on voluntary turnover intention with mediating effect of organizational commitment and job satisfaction (Universitas Indonesia, Graduate School of Management Research Paper No. 13–66). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2328459

- Lievens, F. (2007). Employer branding in the Belgian Army: The importance of instrumental and symbolic beliefs for potential applicants, actual applicants, and military employees. Human Resource Management, 46(1), 51–69.

- Lisbona, A., Palaci, F., Salanova, M., & Frese, M. (2018). The effects of work engagement and self-efficacy on personal initiative and performance. Psicothema, 30(1), 89–96.

- Liu, J., Cho, S., & Putra, E.D. (2017). The moderating effect of self -efficacy and gender on work engagement for restaurant employees in the United States. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(1), 624–642.

- Loquercio, D., Hammersley, M., & Emmens, B. (2006). Understanding and addressing staff turnover in humanitarian agencies, 55, London, UK: Overseas Development Institute.

- Marsh, H.W., & Hocevar, D. (1988). A new, more powerful approach to multitrait- multimethod analyses: Application of second-order confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of applied psychology, 73(1), 107-117.

- Moorman, R.H., Niehoff, B.P., & Organ, D.W. (1993). Treating employees fairly and organizational citizenship behavior: Sorting the effects of job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and procedural justice. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 6(3), 209-225.

- Morya, K.K., & Yadav, S. (2017). Employee engagement and internal employer branding: A study of service industry. Jharkhand Journal of Development and Management Studies, 15(4), 7557–7569.

- Motowidlo, S.J., & Van Scotter, J.R. (1994). Evidence that task performance should be distinguished from contextual performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(4), 475–480.

- Ng, T.W., Eby, L.T., Sorensen, K.L., & Feldman, D.C. (2005). Predictors of objective and subjective career success: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 367–408.

- Organ, D.W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. Pierce, J.L., Gardner, D.G., Dunham, R.B., & Cummings, L.L. (1993). Moderation by organization-based self-esteem of role condition-employee response relationships.Academy of Management Journal, 36(2), 271–288.

- Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, L., & Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

- Preacher, K.J., Rucker, D.D., & Hayes, A.F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42), 185–227.

- Rifai, F.A., Yousif, A.S.H., Bwaliez, O.M., Al-Fawaeer, M.A.R., & Ramadan, B.M. (2021). Employee’s attitude and organizational sustainability performance: Evidence from Jordan’s banking sector. Research in World Economy, 12(2), 166-177.

- Robertson, A., & Khatibi, A. (2013). The influence of employer branding on productivity- Related outcomes of an organization. IUP Journal of Brand Management, 10(3), 17-32.

- Saks, A.M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 600–619.

- Saks, A.M. (2019). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement revisited. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 6 (1), 19–38.

- Salanova, M., Agut, S., & Peiró, J.M. (2005). Linking organizational resources and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: The mediation of service climate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1217–1227.

- Schaufeli, W.B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A.B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92.

- Schaufeli, W., & Bakker, A. (2003). UWES–Utrecht work engagement scale: Test manual. Utrecht, Netherlands: Utrecht University Occupational Health Psychology Unit.

- Schunk, D.H., Meece, J.R., & Pintrich, P.R. (2012). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications. London, UK: Pearson Higher Education.

- Scott, W.R. (2008). Institutions and organizations: Ideas andinterests. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach, (7th edition). John Wiley & Sons Ltd., West Sussex.

- Sharabati, A.A.A., Al-Salhi, N.A., Bwaliez, O.M., & Nazzal, M.N. (2020). Improving sustainable development through supply chain integration: Evidence from Jordanian phosphate fertilizers manufacturing companies. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies on Management, Business, and Economy, 3(2), 10-23.

- Ta’Amnha, M.A., Bwaliez, O.M., & Samawi, G.A. (2021a). The impact of employer brand on employee voice: The mediating effect of organizational identification. Journal of Legal, Ethical, and Regulatory Issues, 24(S1), 1-14.

- Ta’Amnha, M.A., Bwaliez, O.M., Magableh, I.K., Samawi, G.A., & Mdanat, M.F. (2021b). Board policy of humanitarian organizations towards creating and maintaining their employer brand during the COVID-19 pandemic. Corporate Board: Role, Duties, & Composition, 17(2).

- Ta’Amnha, M., Samawi, G.A., Bwaliez, O.M., & Magableh, I.K. (2021c). COVID-19 organizational support and employee voice: insights of pharmaceutical stakeholders in Jordan. Corporate Ownership & Control, 18(3), 367-378.

- Ta’Amnha, M. (2020). Institutionalizing the employer brand in entrepreneurial enterprises. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 10 (6), 183-193.

- Tanwar, K. (2016). The effect of employer brand dimensions on organisational commitment: Evidence from Indian IT industry. Asia-Pacific Journal of Management Research and Innovation, 12(3&4), 282–290.

- Tanwar, K., & Prasad, A. (2017). Employer brand scale development and validation: A second- order factor approach. Personnel Review, 46(2), 389–409.

- Tumasjan, A., Kunze, F., Bruch, H., & Welpe, I.M. (2020). Linking employer branding orientation and firm performance: Testing a dual mediation route of recruitment efficiency and positive affective climate. Human Resource Management, 59(1), 83–99.

- Turban, D.B., & Keon, T.L. (1993). Organizational attractiveness: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(2), 184–193.

- Valcour, M., & Ladge, J.J. (2008). Family and career path characteristics as predictors of women’s objective and subjective career success: Integrating traditional and protean career explanations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(2), 300–309.

- Williams, L.J., & Anderson, S.E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behavior. Journal of Management, 17(3), 601-617.

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W.B. (2009). Work engagement and financial returns: A diary study on the role of job and personal resources. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(1), 183–200.