Research Article: 2022 Vol: 21 Issue: 6S

Emotional Labor in Healthcare: The Role of Work Perceptions and Personality Traits

Joana Carmo Dias, UNIDCOM/IADE - Universidade Europeia

Susana Costa e Silva, Católica Porto Business School

Alberico Rosario, GOVCOPP, IADE - Universidade Europeia

Citation Information: Dias, J.C., Silva, S., & Rosario, A. (2022). Emotional labor in healthcare: The role of work perceptions and personality traits. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 21(S6), 1- 17.

Keywords

Emotional Labor, Nursing Work Environment, Personality Traits, JD-R Model

Abstract

Using the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model as the theoretical framework, this study investigates how the perception of the work environment predicts the emotional labor strategies, and the moderating effect of personality traits on this relationship. Data were collected through the Portuguese Nurses Council, yielding 180 valid questionnaires. The perceptions of the work environment were measured through the Practice Environment Scale for Nurse Working Index (PES-NWI). Emotional labor strategies and the personality traits, in turn, were measured through the Emotional Labor Scale (ELS) and the Big Five Inventory Scale (BFIS) respectively. The hypothesized model was tested through a hierarchical multiple regression and bias-corrected bootstrap analyses (using 1000 bootstrap samples) with the PROCESS macros. The results reveal a negative relationship between perception of the work environment and the adoption of a deep acting strategy. This relationship happens when individuals score high in consciousness and openness and when individuals score low in extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. When healthcare institutions offer a good work environment, nurses try to do their utmost to make their emotions correspond with what is expected of them. Thus, healthcare managers need to better understand how organizational policies and practices are translated into the work environment.

Introduction

Research investigating emotional labor in services settings - a form of emotion regulation that creates a publicly visible facial and bodily display within the workplace - has often emphasized the antecedents and outcomes of managing emotions (Grandey, 2000, 2003; Zapf & Holz, 2006) as the emotional labor performance can lead to several outcomes which can be positive or negative (Gursoy et al., 2011; Karimi et al., 2013). There is a set of variables at a cultural, organizational, or individual level that can predict employee engagement with one of the emotional labor strategies, namely surface acting or deep acting. Surface acting is when employees need to mask their own emotions to display the emotions required by the organization (Grandey, 2000). Deep acting refers to the display of emotions required by the organization through cognitive manipulation of their own emotions (Grandey, 2003). Although there have been attempts to investigate the effect of the emotional labor strategies (Brotheridge & Lee, 2002), no research has examined how the perceptions of the work environment impact the employees’ choice of one or the other approach to manage their emotions.

In the healthcare context, the management of emotions takes greater proportions compared to other service organizations, due to the proximity, frequency, and intensity of relationships between employees and customers (Mechinda & Patterson, 2011). Healthcare workers are employed in a complex, stressful, demanding, and sometimes hazardous work environment that affects outcomes for both organizational and individual levels (Kramer & Son, 2016). Furthermore, research has shown that work environment factors have a direct impact on health provider performance (Oswald, 2012). Accordingly, we wanted to explore this context to provide some insight into the impact that the perceptions of this specific work environment can have on emotional performance. We have decided to study the perception of nurses, who engage in emotional labor when they feel that their emotional displays do not match patient or social expectations (Mann & Cowburn, 2005). Such behavior assists nurses in managing their patients' reactions by facilitating emotional relief and has a positive association with psychological and physical well-being and recovery (Man & Cowburn, 2005). Emotional labor as a part of a dynamic and interdependent complex cannot be understood outside the influence of self and identity. When nurses choose to engage in one of the emotional labor strategies (surface or deep acting) their personality characteristics may predict this choice.

A positive perception of the work environment, even in a demanding service sector such as the healthcare sector, can lead to nurse’s engagement and to the choice of a more authentic strategy that also contributes to personal achievement, less stress, effective performance, and job satisfaction (Brotheridge & Lee, 2002; Grandey, 2003; Groth et al., 2009).

This paper is organized as follows. First, to further conceptualize how the perceptions of the work environment, emotional labor strategies and personality traits may combine, we examined the job demands-resources model that states that even if employees work in a demanding role; they can experience less stress if the organization provides resources to support them (Demerouti et al., 2001). Next, we build our theoretical framework including the relationship between work environment perceptions and emotional labor strategies and the moderation effect of the personality traits. Finally, we present the findings derived from our data.

Theoretical Background

Job Demand-Resources (JD-R) Theory

The Job Demands-Resources Model was initially developed by Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner & Schaufeli (2001) as an attempt to overcome the limitations of other existing models of employee well-being, such as the demand-control model (Karasek,1979), and the effort-reward imbalance model (Siegrist,1996). JD-R model predicts employee and organizational well-being, by considering a variety of job characteristics and their corresponding interactions on stress and motivation. It was also developed to combine the negative outcomes of work and the health-enhancing effects of positive job characteristics (de Lange et al., 2008). This model has two main assumptions that we will study throughout the paper.

The starting point of the JD-R model is the assumption that regardless of the type of job, the psychosocial work characteristics can be broadly categorized into two groups, namely job demands and job resources (Demerouti et al., 2001; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). These two groups influence respectively the health and commitment of employees or more specifically influence the level of burnout of employees. In general, job demands and job resources are negatively related, since job demands such as high work pressure and emotionally demanding interactions with customers may restrain the mobilization of resources (Bakker et al., 2003; Demerouti et al., 2000, 2001).

Job demands are the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require continuous effort and are hence related to certain physiological and/or psychological costs (Demerouti et al., 2001). High work pressure, role overload, unfavorable physical environment, and emotionally demanding interactions are some examples of job demands that may turn into job stressors (Meijman & Mulder, 1998).

In contrast, job resources refer to physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that are either functional in achieving work goals, reducing job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs, or stimulating personal growth, learning, and development (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). For example, feedback, job control, and social support are the aspects that can foster engagement as well as mitigate the adverse consequences of undue job demands (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). As mentioned by Pelfrene, et al., (2002), the psychosocial work situation such as the decision freedom of the worker, social support networks, and job demands should also be considered. Job resources may be placed at the organizational level (e.g., career development, job security, salary), interpersonal level and social relations (e.g., support from colleagues, leadership, teamwork), the job position (e.g., role clarity, participation in decision making), and task level (e.g., skill diversity, task identity, autonomy, and performance feedback). Hence, resources are not only important to deal with job demands, but they are also necessary to foster positive thoughts and feelings about work and the organization, human motivation, and to achieve individual goals (Van den Broeck et al., 2008).

We propose that such positive thoughts and feelings about their role, job, and organization may influence the extent to which service employees engage in surface or deep acting. We focus on work environment perceptions as a key job resource because it is composed of physical and social organizational factors that help achieve goals and foster engagement.

Work Environment Perceptions and Emotional Labor

To perform a service job adequately, employees may be required to present types of emotions that differ from their inner feelings. Faced with these emotional demands, employees must “manage feelings to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display” (Hochschild, 1983), that is, do emotional labor. According to Hochschild (1983), service providers can have two types of emotional labor behavior: a) surface acting – ‘faking feelings’ to align with expectations, ie., when one performs an emotional display to meet certain rules and expectations; or b) deep acting – attempting to modify feelings to match expectations, ie., when a person consciously attempts to feel a specific emotion that matches the expected emotional displays (Grandey, 2003).

Frontline employees do not exclusively adopt one approach over another, but this choice can depend on several internal or external factors. For example, maybe determined by the amount and quality of resources that are available when they do not experience the required emotions (Chou et al., 2012). Several authors studied the main drivers of emotional labor strategies that can be found at a cultural, organizational, or individual level (Martin et al., 2016). However, and although there are several studies about the possible antecedents of emotional labor, there is one element, which was not studied yet – the perception of the work environment.

The work environment includes all external factors and variables that surround an employee and that can have an impact on his/her performance, such as the information, tools, and incentives that support performance (Robinson & Robinson, 1996; Gilbert, 1996). Although we can obtain data regarding work environment factors through various methods, the most reliable is from employees in the given environment (Bell, 2008). Employees provide the best information regarding how work environment factors influence their performance through their interpretation of reality (Robinson & Robinson, 1996).

Previous studies have suggested that employees' perceptions of their work environment may impact job performance, productivity, job satisfaction, and employees' creativity. For example, Maurer, et al., (2003) found that the intention and willingness of employees to participate in developmental activities may be influenced by employees' perceptions of supervisory and organizational support. A study conducted on employees at public universities concluded that the work environment has a significant positive impact on organizational commitment (Hanaysha, 2016). Yeh & Huan (2017) analyzed employees' creativity in hospitality and concluded that social support, resource adequacy, and freedom positively affect both employees' quantity and quality of creative performance. Another study associated work environment with employee job satisfaction in the context of banking, university, and telecommunication (Raziq & Maulabakhsh, 2015). They concluded that bad working conditions restrict employees from demonstrating their capabilities and reaching their full potential. According to Wilson, et al., (2012), the perceived services cape can also elicit emotional responses. Being in a particular place can make a person feel happy, light-hearted, and relaxed, or may make a person feel sad, stressed, depressed and gloomy.

We have further investigated the context of healthcare employees as they are employed in a complex, stressful, demanding, and sometimes hazardous work environment, which affects outcomes for both organizations and employees (Kramer & Son, 2016). This is especially relevant in the current Covid19 pandemic that we are witnessing (Ramaci et al., 2020). Nurses are at risk of burnout as they are exposed to intense physical and emotional suffering and are frequently the focus of patients’ reactions, both affectionate and hostile resulting sometimes even in posttraumatic growth (Hamama?Raz et al., 2020). Several studies found that the nursing work environment with high exposure to psychological demands and how work was organized were closely linked to stress, increased the probability of low vitality, bad mental health, and high emotional exhaustion (Escribà-Agüir, Pérez-Hoyos, 2007; Ramaci et al., 2020; Blake et al, 2020).

Undoubtedly, all the work environment factors have a direct impact on the health provider's performance (Oswald, 2012). For example, Aiken, et al., (2008), found that higher percentages of the nurses in hospitals with poor care environments reported high burnout levels and dissatisfaction with their jobs; on the contrary, when professional environment attributes were evaluated to be better, nurses’ work stress decreased, and nurses’ satisfaction indicators increased linearly (Tervo-Heikkinen et al., 2008). In sum, perceptions of a supportive work environment are the basis for reducing stress and increasing nurses’ satisfaction (Kirwan et al., 2013; Ganz & Toren, 2014; Zhang et al., 2014).

Hence, a positive perception of the work environment will result in a willingness to adopt an emotional labor strategy that is more authentic, require less effort, and contribute to job satisfaction. Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is postulated:

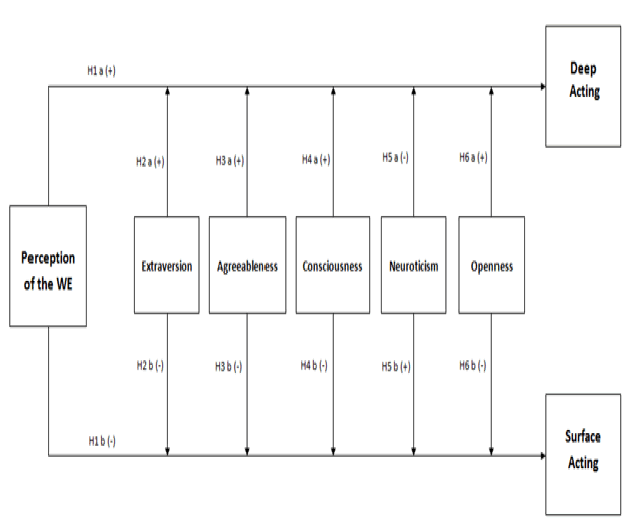

H1: The WE perceptions will affect the type and frequency of EL performance such that, (a) perceptions of the WE relate positively with deep acting and (b) negatively with surface acting strategies.

Personality Traits and Emotional Labor

Another assumption of the JD-R model refers to the relationships between job demands and resources. There are two possible ways in which demand and resources may have a combined effect on wellbeing, and indirectly influence performance. The first interaction proposed is the buffer effect of job resources on the relationship between job demands and strain (Demerouti & Bakker, 2006). In other words, employees who possess adequate or more resources could better cope with job demands and suffer less; whereas employees who are lacking resources may not be able to cope with job demands effectively, thus suffering more. Several studies have shown that job resources like social support, autonomy, performance feedback, and development opportunities can mitigate the impact of job demands on the strain, including burnout (Bakker et al., 2005; Xanthopoulou et al., 2006).

The second interaction is the boost effect of job demands on the relationship between job resources and work motivation (Demerouti & Bakker, 2006). Job resources become salient and influence motivation most when job demands are high. In other words, when an employee is confronted with challenging job demands, job resources become a valuable and foster dedication to the tasks at hand.

The literature offers ample evidence for the fact that personality characteristics shape (buffer or booster) adverse outcomes of stressors in general (Bakker et al., 2005). In our study, the personality traits function as a buffer or booster effect on the relationship between the perceptions of the work environment and the emotional labor strategies. The emotional labor performance is not an independent element of customer service employees, but instead, it is a part of a dynamic and interdependent complex comprising physical and intellectual aspects. Emotional labor performance cannot be understood outside the influence of self and identity. The display of emotions is, thus, dependent on the personality of the employees. When nurses choose to engage in one of the emotional labor strategies – surface acting or deep acting – their personality characteristics, as extraversion, agreeableness, consciousness, neuroticism, and openness, may predict this choice. Personality characteristics refer to the propensity to react in certain ways in given situations (Caprara & Cervone, 2000) and several authors studied personality characteristics as antecedents of emotional labor (Diefendorff et al., 2005; Gursoy et al., 2011; Qadir & Klan, 2016; Schaubroeck & Jones, 2000; Zhong et al., 2012). However, we study the role of these characteristics as moderators of the impact of the perceptions of work environment, as job resources, on emotional labor strategies.

Despite the breadth of theoretical perspectives (John et al., 1991; McAdams, 1995), research approached consensus on a general taxonomy of personality characteristics, known as the “Big Five”. The Big Five postulates that individual differences in adult personality characteristics can be organized into five broad domains: extraversion, neuroticism, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness (John & Srivastava, 1999). A large body of empirical research has supported the stability and predictive validity of the Big Five across different populations, contexts, and countries (Borghans et al., 2008).

In a study that examined the association between personality traits and emotional labor strategies, Diefendorff et al. (2005) added that extroverted individuals experience positive emotions more often and thus they may have less of a need to fake their emotions during their interactions (to surface act) and be more likely to display their real feelings. Similarly, Austin and colleagues (2008) found a negative relationship between extraversion and surface acting. Based on those arguments, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Extraversion will (a) booster the relationship between the perception of WE and deep acting, and will (b) buffer the relationship between the perception of WE and surface acting.

Another feature worth investigating is agreeableness, which describes individuals as being flexible, courteous, friendly, good-natured, cooperative, trusting, soft-hearted, generous, and tolerant, and forgiving (McCrae & Costa, 1991; Barrick & Mount, 1991; Mroz & Kaleta, 2016). These individuals are more likely to express positive emotions and suppress negative emotions at work. As such, they are greatly motivated to get along with others and try to develop and maintain positive relationships with others (McCrae & Costa, 1991). Studies show that individuals, who score higher on agreeableness, were more likely to engage with deep acting (Kim, 2008; Austin et al., 2008; Kiffin-Petersen et al., 2011). They are expected to put more effort into emotion regulation so that they have positive social interactions (Diefendorff et al., 2005). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

H3: Agreeableness will (a) booster the relationship between the perception of WE and deep acting and will (b) buffer the relationship between the perception of WE and surface acting.

One more personal characteristic is conscientiousness, which is related to people that are efficient, competent, hard-working, responsible, and persistent, and achievement-oriented (McCrae & Costa, 1991; Prentice, 2008). They are careful in carrying out their job tasks as they tend to perform well and have higher levels of safety performance at work. Because of this, conscientious individuals follow rules for emotional expression and are more likely to display positive fake emotions to fulfill their job responsibilities (Yazdani, 2013). Conscientious people need less effort to express positive emotions and suppress negative emotions; hence conscientiousness is negatively correlated with surface acting and positively with deep acting and the expression of naturally felt emotions (Diefendorff et al., 2005; Kiffin-Petersen et al., 2011; Basim et al., 2013; Austin et al., 2008). Since conscientious individuals are more responsible and careful, they show greater adherence to display rules and meet the organization’s expectations by trying to be more authentic and sincere (Diefendorff et al., 2005). We developed the following hypotheses to test that feature:

H4: Consciousness will (a) booster the relationship between the perception of WE and deep acting and will (b) buffer the relationship between the perception of WE and surface acting.

Neuroticism, in turn, is commonly characterized by anxiety, fear, moodiness, worry, envy, frustration, jealousy, and loneliness (Thompson, 2008). Individuals who score high on neuroticism are more likely than average to experience such feelings, to respond more poorly to stressors, to interpret ordinary situations as threatening, and minor frustrations as hopelessly difficult (Matthews & Deary, 1998). Diefendorff et al. (2005) confirmed that individuals with a high score on neuroticism would use a surface acting strategy because surface acting requires relatively little mental effort about regulating emotions, whereas deep acting is more demanding (Zapf, 2002). Furthermore, individuals who score high on neuroticism experience more negative emotions and have the tendency to suppress their emotions (Chioqueta & Stiles, 2005). We propose the following hypothesis:

H5: Neuroticism will (a) buffer the relationship between the perception of WE and deep acting and will (b) booster the relationship between the perception of WE and surface acting.

Finally, openness to experience describes the breadth, depth, originality, and complexity of an individual’s mental and experiential life (John & Srivastava, 1999). This trait relates to intellect, openness to new ideas, cultural interests, educational aptitude, and creativity. People with high openness to experience have broad interests and deeper scope of awareness, are liberal and like novelty (Howard & Howard, 1995; McCrae & Costa, 1991). However, this characteristic is not related to any kind of facial expression and any social interaction (McCrae & Costa, 1991). Thus, individuals who score high in openness are not suitable for service providing, because most of the time they are unable to hide their original feelings (Prentice, 2008; Smith & Canger, 2004). Therefore, we predict that:

H6: Openness will (a) booster the relationship between the perception of WE and deep acting, and will (b) buffer the relationship between the perception of WE and surface acting.

Based on all the arguments provided, we assumed that personality traits function as a moderator because they may buffer (decrease) and/or boost (increase) the relationship between the perceptions of the work environment and the emotional labor strategies. Our hypothesized model is presented in Figure 1.

Research Design

Data Collection

We conducted a survey online that was made available to nurses working in various healthcare units, as public and private hospitals, health centers, and clinics in Portugal. The participants were told that the purpose of the research was “to explore the association between the relationship nurses/patients and some demographic factors”. Data were collected from 180 valid questionnaires. Our group of participants consists of 133 (74%) female nurses and 47 (26%) male nurses. This disparity demonstrates well the Portuguese reality regarding the number of registered nurses in the Portuguese Nursing Council, 82% are women and 18% men. The men who make up our sample work on average for 18 years (SD = 9.28) as nurses, and women work on average for 14 years (SD = 10.03). More than 2/3 of our sample had a degree (67%). A great part of nurses work in public hospitals (52,5%) and half do not have a specialization in nursing (50%).

Measures of Constructs

Demographics

A 25-item questionnaire was developed to assess several demographic variables of interest, such as age, sex, job tenure, nursing specialization, type of health institution, and educational level.

Emotional Labor Scale (ELS)

Emotional labor strategies were measured with the emotional labor scale developed by Brotheridge & Lee (2003). This scale is divided into five emotional labor dimensions, however, we just assessed the dimensions of surface acting and deep acting as they are directly related to the aim of the study. The items in the deep acting subscale assess how much an employee has to modify feelings to comply with display rules. Moreover, the surface acting dimension measures the extent to which the employee must express emotions that are not felt and suppress feelings that conflict with display rules (Brotheridge & Lee, 2003). Participants were asked to answer these items in response to the following question "On an average day at work, how often do you do each of the following when interacting with customers?" The dimensions were measured with a five-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = always). In the present study, Cronbach's α for deep acting and surface acting, respectively, were 0.70 and 0.72.

Big Five Inventory Scale (BFI)

The personality assessment is made through the Big Five Inventory Scale (John & Srivastava, 1999), consisting of 44 items designed to assess personality in five dimensions: agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness to experience. Through a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), participants answered according to the degree they fit into a variety of responses. The 44 items selected for the inventory are composed of short and simple understanding sentences and refer to only one of the five dimensions that make up the Big Five personality. In the present study, Cronbach's α was for extraversion 0.81, for agreeableness 0.70, for consciousness 0.78, for neuroticism 0.76, and openness 0.77.

Practice Environment Scale for Nurse Working Index (PES-NWI)

The nurse work environment was measured by the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI; Lake, 2002) which comprises 28 items. We selected the 20 items that best fit our study across the five subscales that are included in the overall tool: nurse participation in hospital affairs (3 items), nursing foundations for quality of care (4 items), nurse manager ability, leadership, and support for nurses (5 items), staffing and resource adequacy (3 items), and nurse-physician relationships (5 items). This scale indicates the degree to which various modifiable organizational features are present in the nurse workplace with higher scores indicating more favorable ratings (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). In the current study, we have found excellent internal consistency for this scale (alpha= 0.91).

Data Analysis

After coding the variables, the data were processed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 23. The variables distribution was tested for normality by the Shapiro-Wilks test. To test the hypothesized model, we conducted a hierarchical multiple regression for the association between the perception of work environment and emotional labor strategies and the big five personality characteristics and emotional labor strategies, and we conducted bias-corrected bootstrap analyses (using 1000 bootstrap samples) with the PROCESS macros developed by Hayes (2013) to test the moderating effects.

Due to the conceptual orthogonal nature of the Big Five (McCrae & Costa, 2003), five separate, yet identical analyses were conducted, one for each dimension of personality tested. Following Aiken & West’s (1991) recommendation for using centered variables (i.e., standardized so that their means are zero and their standard deviations are one), each predictor and moderator variable was centered to reduce multicollinearity between the interaction term and the main effects when testing for moderation.

Findings

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and Cronbach alphas for all measures included in the study.

| Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, Internal Consistencies (Cronbach’s ? On The Diagonal), And Pearson Correlations (N = 180) |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |||||||||||||||

| Variables | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p-value | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | |

| 1 | PES-NWI | 2.65 | 0.71 | 2.94 | 0.84 | 0.02 | (0.91) | |||||||||

| 2 | Surface acting | 6.17 | 1.45 | 6.08 | 2.03 | 0.75 | 0.00 | (0.72) | ||||||||

| 3 | Deep acting | 5.73 | 1.89 | 6.10 | 1.65 | 0.23 | -0.17* | 0.01 | (.70) | |||||||

| 4 | Extraversion | 28.33 | 5.41 | 27.80 | 5.59 | 0.56 | 0.09 | 0.27** | -0.17* | (0.81) | ||||||

| 5 | Agreeableness | 35.0 | 4.14 | 32.93 | 5.24 | 0.007 | 0.04 | 0.20** | -0.09 | 0.33** | (0.70) | |||||

| 6 | Consciousness | 36.72 | 4.38 | 34.23 | 5.81 | 0.003 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.34** | 8** | (0.78) | ||||

| 7 | Neuroticism | 21.54 | 5.11 | 19.70 | 4.78 | 0.03 | -0.23** | -0.10 | 0.05 | -0.35** | -0.33** | -0.24** | (0.76) | |||

| 8 | Openness | 36.28 | 5.24 | 38.87 | 5.78 | 0.005 | 0.03 | 0.10 | -0.08 | 0.38** | 0.26** | 0.30** | -0.17* | (0.77) | ||

| 9 | Age | 37.11 | 10.22 | 39.78 | 9.22 | 0.05 | -0.12 | 0.12 | 0.10 | -0.09 | 0.00 | -0.17* | 0.06 | (n.a.) | ||

| 10 | Job tenure | 14.80 | 10.03 | 18.04 | 9.28 | 0.06 | -0.16* | 0.11 | 0.12 | -0.06 | -0.03 | -0.21** | 0.06 | 0.97** | (n.a.) | |

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

Abbreviations: PES-NWI, Practice Environment Scale for Nurse Working Index; SD, standard deviation.

There is sufficient statistical evidence that allows us to conclude that the perception of the work environment is negatively associated with deep acting (r =-0.17, p <0.05). This means that the better the perception of the work environment fewer nurses tend to use deep acting. Extraversion (r =0.27, p <0.01) and agreeableness (r =0.20, p <0.01) were positively associated with surface acting. In other words, when nurses score high in extraversion and agreeableness, they are more likely to suppress and fake their emotions. In turn, job tenure (r =-0.16, p <0.05) was negatively associated with surface acting. That is, the higher the number of years in the profession, the fewer nurses tend to adopt a surface acting strategy or the less they tend to hide their emotions. Finally, extraversion (r =-0.17, p <0.05) was also negatively associated with deep acting. This means that when nurses score high in extraversion, they do not tend to use deep acting, i.e., to display more authentic emotions.

Concerning the moderating effects (table 2), we found no interaction effects of the impact of personality traits on the relationship between the work environment perception and emotional labor strategies. Extraversion, agreeableness, consciousness, neuroticism, and openness were separately examined as a moderator of this relationship in two different steps. The perception of the work environment and each different personality trait were entered in the first step of the regression analysis. In the second step of the regression analysis, the interaction term between each personality trait and perception of the work environment was entered and did not showed a significant increase in variance in deep acting and surface acting. Thus, the five personality traits were not a significant moderator of the relationship between perception of the work environment and deep acting, and surface acting.

| Table 2 Moderated Regression Testing The Link Between Work Environment Perceptions And Emotional Labor Strategies |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV: Deep Acting | DV: Surface Acting | |||||||

| Control Variables | IV | Moderators | Interactions | Control Variables | IV | Moderators | Interactions | |

| Age | 0.12 | - | - | - | -0.12 | - | - | - |

| Gender | 0.08 | - | - | - | -.002 | - | - | - |

| Tenure | 0.11 | - | - | - | -0.16* | - | - | - |

| WE perceptions | - | -0.17* | - | - | - | 0.00 | - | - |

| Extraversion | - | - | -0.17* | - | - | - | 0.27** | - |

| Agreeableness | - | - | -0.09 | - | - | - | 0.20** | - |

| Consciousness | - | - | -0.04 | - | - | - | 0.04 | - |

| Neuroticism | - | - | 0.05 | - | - | - | -0.10 | - |

| Openness | - | - | -0.08 | - | - | - | 0.10 | - |

| WE x Extraversion | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| WE x Agreeableness | - | - | - | -0.01 | - | - | - | 0.03 |

| WE x Consciousness | - | - | - | 0.03 | - | - | - | 0.03 |

| WE x Neuroticism | - | - | - | -0.06 | - | - | - | -0.00 |

| WE x Extraversion | - | - | - | 0.02 | - | - | - | 0.01 |

| WE x Openness | - | - | - | 0.00 | - | - | - | -0.00 |

| F | - | - | - | 1.82 | - | - | - | 3.21 |

| R2 | -0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| ? R2 | - | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | - | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

Abbreviations: WE, work environment; R2, regression model; DV, dependent variable; IV, independent variable.

Discussion

Based on the precepts of the JD-R theory, this study developed and tested a research model, which investigates the relationship between the perceptions of the work environment and the emotional labor strategies and personality traits as the moderators of this relationship. To tackle this objective, six hypotheses were suggested, based on the relevant literature on emotional labor, work environment, and personality traits, and the sample of nurses was chosen. Generally, we found that a perception of the work environment is negatively associated with the use of one of the emotional labor strategies. To the extent that the more positive the perception of the work environment fewer nurses tend to adopt a strategy of deep acting. However, we could not confirm the booster and buffer effects of the personality traits. In other words, personality traits do not interfere with the relationship between work environment perceptions and emotional labor strategies.

The Relationship between the Perceptions of the Work Environment and Emotional Labor Strategies

In our first hypotheses, H1a and H1b, we expected that a positive perception of the work environment, as a job resource, would be positively associated with the adoption of deep acting and would be negatively associated with the use of surface acting. Our hypotheses were not confirmed, however, the results revealed that there is a negative relationship between work environment perceptions and deep acting and, even if not statistically significant, there is a slightly positive relationship between work environment perceptions and surface acting. That means that nurses’ perceptions of their work environment have an impact on their emotional labor strategies, but in a reverse way, we were expecting. Thus, as nurses are getting a positive perception of their work environment, they do not try to change their inner feelings to feel a specific emotion; they instead show an inauthentic expression of themselves, trying to display positive fake emotions.

A possible explanation is that, because they have a positive perception of the work environment, nurses try to do their utmost to make their emotions correspond with what is expected of them. And given this work environment that is quite specific and emotionally tense, nurses are more likely to display positive fake emotions to fulfill their job responsibilities and to ensure that their emotions match patients' and the organization's expectations. In other words, the perceptions of the work environment mitigate the use of emotional labor strategies. In the literature, surface acting is understood as something negative and synonymous with employees' dissatisfaction (Hochschild, 1983; Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Morris & Feldman, 1996; Schaubroeck & Jones, 2000). However, in this specific work environment surface acting may be synonymous with employees' job satisfaction and employees' attempt to fulfill their responsibilities.

Our data indicated another important finding. Job tenure is negatively associated with the surface acting strategy. The length of work as nurses had an impact on the willingness to adopt the surface acting strategy. This finding means that the greater the number of career years, the lower the tendency for nurses to pretend and hide their emotions. Given that increases in job tenure are also accompanied by increases in chronological age, this is in line with the socioemotional selectivity theory that postulates that as people become older, they tend to be emotional expressive (Cheung & Tang, 2010; Hur et al., 2014) and avoid suppressing their emotions. People become motivated to maximize the experience of positive emotions and minimize the experience of negative emotions (Charles & Carstensen, 2007). Research on aging and development also confirms our data, suggesting that older individuals give higher priority to socially-oriented tasks (Carstensen et al., 1999) and invest their resources more in those goals that match their motivations and interests (Beier & Ackerman, 2001).

The Moderation Effect of Personality Traits

No significant moderating effects of the personality traits on the relationship between work environment perception and emotional labor strategies were found, thus contradicting our hypotheses. However, our study shows some patterns within the data, as we summarized in table 3. The negative relationship between perceptions of work environment and deep acting, which we found in the first part of the study, happens when individuals score high in consciousness and openness and when individuals score low in extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. In turn, the positive relationship found between perceptions of work environment and surface acting occurs when individuals score high in extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness and score low in consciousness. These two relationships that are somewhat subjected to different personality traits seem to show an inverse pattern, the personality traits that are high in one relationship appear to be low in the other relationship and vice versa.

| Table 3 Relationship Between Perceptions Of Work Environment And Emotional Labor Strategies And Personality Traits |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Work Environment Perceptions | Personality Traits | ||

| High | Low | ||

| Deep Acting | Negative | Consciousness Openness |

Extraversion Agreeableness Neuroticism |

| Surface Acting | Positive | Extraversion Agreeableness Neuroticism Openness |

Consciousness |

A possible explanation for these results is as follows. First, extraversion refers to the traits of being cheerful, talkative, active, and outgoing (Block, 1961 & Zellars et al., 2000; McCrae & Costa, 1991). These individuals are optimistic about things, situations, and events. So, they may likely display higher levels of surface acting. Also, due to their social skills, as they can adjust themselves according to the situation, extroverts may easily display positive fake emotions, i. e., and surface acting. Our result agrees with Ehigie & colleagues (2012) that found that extraversion was a negative predictor of deep acting and a positive predictor of surface acting.

Second, agreeable individuals are tolerant, cooperative, forgiving, and caring (Barrick & Mount, 1991). According to McCrae & Costa (1991), such individuals are greatly motivated to get along with others and establish honest and respected relations. They hardly retaliate when someone treats them badly and they try to maintain the impression that they are very nice, tolerant, sensitive, and trustworthy. Therefore, to maintain that impression, they may tend to express fake emotions and to put on a good face during interactions with others.

Third, conscientiousness relates to being responsible, self-disciplined, and acting dutifully (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Consciousness may be negatively related to engaging in emotional labor because a conscientious person is believed to possess qualities that reflect non-dependability (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Hough, 1992; Moon 2001). Non-dependable persons make their own decisions, so they don't behave in some way others want them to. Therefore, we can say they need less effort to express positive emotions and suppress negative emotions, that is, to perform emotional labor.

Fourth, individuals who are high on neuroticism are more likely to experience negative emotions and feelings of stress and anxiety. Therefore, they may require more psychological effort to suppress these negative emotions during social interactions. And, because they may want to compensate for their inner negative feelings and want to be acceptable in front of others, they may likely adopt a surface acting strategy.

Fifth, openness to experience reflects a person's curiosity, originality, intellect, creativity, and flexibility (McCrae & Costa, 1991). According to Prentice (2008) and Smith & Canger (2004), the characteristics attained by openness individuals are not appropriate for service providing, because most of the time they are unable to hide their original feelings. So, they may face more emotional labor, and be unable to regulate the needed emotions during the interpersonal transaction. For these, and to fulfill their responsibilities, nurses may engage in surface acting.

In sum, although there is not enough statistical significance some personality characteristics are positively and negatively associated with both strategies of emotional labor. It is likely that one's personality – a relatively stable pattern of how one perceives and reacts to their environment – will influence how one manages their emotions in the workplace.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that investigated the association between the perceptions of the work environment and their choice for one of the emotional labor strategies – surface acting and deep acting –, as well as the moderating effect of personality traits within this relationship. The theoretical significance of this research is fourfold: 1) the perception of the work environment is negatively associated with one of the emotional labor strategies, that is, when a positive perception of the workplace is displayed there is no tendency to adopt a deep acting strategy; 2) this statistically significant association happens when individuals score high in consciousness and openness; 3) we found a statistically negative association between extraversion and deep acting and positive association between extraversion, agreeableness and surface acting; and 4) job tenure is negatively associated with surface acting.

Our results meet the idea that emotional labor is normally synonymous with not exhibiting genuine emotions, so we can assume that when we are in an environment that we consider positive or neutral, this need to forge emotions is not so necessary. Also, we may assume that emotional regulation is somewhat subjected to different personality traits. Extraverted individuals need less effort to exhibit positive emotions during service interactions. Thus, it is proposed that extraverted individuals face less emotional labor as they are social and ambitious. Individuals who score higher on agreeableness also express positive emotions easily because of their sincere disposition. So, it is proposed that individuals with agreeable personalities face less emotional labor in the management of emotions. Individuals with neurotic characteristics are not suitable for the service sector. They require more effort to regulate the organizationally required display emotions to fulfill the job tasks. Thus, is proposed that they will face more emotional labor to manage emotions. Conscientious individuals are careful in carrying out their job tasks and may thus be more appropriate to adhere to and display rules for emotional expression. Therefore, results support the argument that these individuals are good at interpersonal transactions.

For now, these findings have led to a deeper and fuller understanding of the impact of work environment perceptions and personality traits on the management of emotions at work. When healthcare institutions offer a good work environment, nurses try to do their utmost to make their emotions correspond with what is expected of them. Thus, healthcare managers need to examine how organizational policies and practices are translated into the work environment. Also, if we can better understand how nurses perceive their work environment and how that will affect, along with their personality, the way they manage emotions and present themselves to patients, we design better work environments.

Limited generalizability of the findings resulted from the small sample size and the convenience sample procedures, which can include paper-and-pencil surveys. Future studies might attempt to avoid the common method-variance problem by collecting data from different sources. We acknowledge that our sample was predominantly female. This is a typical phenomenon across the healthcare industry since most nurses are women. In Portugal is no exception, 80% of registered nurses are women and 20% are men. The number of items presented in the survey is higher than the sample size because we decided to use the original version of the scales and not the short version making this study more reliable. To solve this issue, future studies should increase the sample size and the ratio be at least 3 observations per item. Participants in the study were placed in units, but the "team" effects were not analyzed. To address this limitation, future research should consider the fact that nurses work in teams, and this can affect their perception of the work environment as well as the way they manage emotions Finally, our study was conducted using a homogeneous sample, namely nurses. Therefore, it would be important to test the external validity of the results for other working populations and organizations. But also, it would be useful if future studies replicate this study to a sample of physicians and make a comparison between these two important healthcare professions. Investigating other work environments would also be recommended to reveal any further idiosyncrasies, namely environments where the Covid19 outbreak presented different repercussions.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to the Editor and the Referees. They offered valuable suggestions or improvements. The authors were supported by the GOVCOPP Research Center of the University of Aveiro, and UNIDCOM, IADE - European University. Joana Carmo Dias has financial support from the Foundation for Science and Technology (through project UIDB/00711/2020) and Susana Costa e Silva has financial support from Foundation for Science and Technology (through project UIDB/00731/2020).

References

Aiken, L.S., & West, S.G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Austin, E.J., Dore, T., & O"Donovan, K.M. (2008). Associations of personality and emotional intelligence with display rule perceptions and emotional labour. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(3), 679–688.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Bakker, A.B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State-of-the-art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22, 309-28.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., & Euwema, M.C. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10, 170-80.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W.B. (2003a). Dual processes at work in a call centre: An application of the Job Demands-Resources model. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 12, 393-417.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., De Boer, E., & Schaufeli, W.B. (2003b). Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62, 341-56.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Barrick, M.R., & Mount, M.K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44, 1-26.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Basim, H., Begenirbas, M., & Yalcin, R. (2013). Effects of teacher personalities on emotional exhaustion: Mediating role of emotional labor. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 13(3), 1488-1496.

Beier, M.E., & Ackerman, P.L. (2001). Current-events knowledge in adults: An investigation of age, intelligence, and nonability determinants. Psychology and Aging, 16, 615-628.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Bell, E. (2008). Exploring employee perception of the work environment along generational lines. Performance Improvement, 47(9), 35–45.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Blake, H., Bermingham, F., Johnson, G., & Tabner, A. (2020). Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a digital learning package. International Journal of Environmental Rsearch and Public Health, 17(9), 2997.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Block, J. (1961). The Q-sort method in personality assessment and psychiatric research. Springfield IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Borghans, L., Duckworth, A., Heckman, J., & Weel, B. (2008). The economics and psychology of personality traits. The Journal of Human Resources, 43(4), 972-1059.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Brotheridge, C.M., & Lee, R.T. (2002). Testing a conservation of resources model of the dynamics of emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(1), 57-67.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Brotheridge, C. M. & Lee, R. T. (2003). Development and validation of the emotional labour scale. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76, 365.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Caprara G.V., & Cervone D. (2000). Personality: Determinants, dynamics, and potentials. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Carstensen, L.L., Issacowitz, D.M., & Charles, S.T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54, 165-181.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Charles, S.T. & Carstensen, L.L. (2007). Emotional regulation and aging. In J.J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation, 307–327. New York: Guilford Press.

Cheung, F., & Tang, C. (2010). Effects of age, gender, and emotional labor strategies on job outcomes: Moderated mediation analyses. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 2(3), 323–339.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Chioqueta, A.P., & Stiles, T.C. (2005). Personality traits and the development of depression, hopelessness, and suicide ideation. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(6), 1283–1291.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Chou, H., Hecker, R., & Martin, A. (2012). Predicting nurses’ well-being from job demands and resources: a cross-sectional study of emotional labour. Journal of Nursing Management, 20, 502-511.

Crossref,GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Costa, P.T., & McCrae, R.R. (1992). The five-factor model of personality and its relevance to personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 6(4), 343–359.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

De Lange A.H., De Witte, H., & Notelaers, G. (2008). Should I stay or should I go? Examining longitudinal relations among job resources and work engagement for stayers versus movers. Work and Stress, 22, 201–223.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A.B. (2006). Employee well-being and job performance: Where we stand and where we should go. In J. Houdmont, & S. McIntyre (Eds.). Occupational Health Psychology: European Perspectives on Research, Education and Practice, 1, Maia, Portugal: ISMAI Publications.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A.B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W.B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499-512.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A.B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W.B. (2000). A model of burnout and life satisfaction among nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32, 454-64.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Diefendorff, J.M., Croyle, M.H., & Gosserand, R.H. (2005). The dimensionality and antecedents of emotional labor strategies. Journal of Vocational Behavior,66(2), 339-357.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Ehigie, B.O., Oguntuase, R.O., Ibode, F.O., & Ehigie, R.I. (2012). Personality factors and emotional intelligence as predictors of Frontline Hotel employees’ emotional labor. Global Advanced Research Journal of Management and Business Studies, 1(9), 327-338.

Escribà-Agüir, V., & Pérez-Hoyos, S. (2007). Psychological well-being and psychosocial work environment characteristics among emergency medical and nursing staff. Stress and Health, 23, 153-160.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Ganz, F., & Toren, O. (2014). Israeli nurse practice environment characteristics, retention, and job satisfaction. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 3, 3-7.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Gilbert, T.F. (1996). Human competence: Engineering worthy performance. Amherst, MA: HRD Press, Inc., and Washington, DC: The International Society for Performance Improvement.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Grandey, A. (2000). Emotional regulation in the workplace: a new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1, 95–110.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Grandey, A. (2003). When the show must go on: surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal, 1, 86-96.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Groth, M., Hennig-Thurau, T., & Walsh, G. (2009). Customer reactions to emotional labor: the roles of employee acting strategies and customer detection accuracy. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 958-974.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Gursoy, D., Boylu Y., & Avci U. (2011). Identifying the complex relationships among emotional labor and its correlates. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30, 783-794.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Hamama-Raz, Y., Hamama, L., Pat-Horenczyk, R., Stokar, Y.N., Zilberstein, T., & Bron-Harlev, E. (2021). Posttraumatic growth and burnout in pediatric nurses: The mediating role of secondary traumatization and the moderating role of meaning in work. Stress and Health, article in press.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Hanaysha, J. (2016). Testing the effects of employee engagement, work environment, and organizational learning on organizational commitment. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 229, 289-297.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Hayes, A.F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hochschild, A. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley: US, University of California Press.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Hough, L.M. (1992). The big five personality variables-construct confusion: Description versus prediction. Human Performance, 5, 139-155.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Howard, P.J., & Howard, J.M. (1995). The big five quickstart: an introduction to the Five-Factor Model of Personality for human resource professionals. Charlotte, NC: Centre for Applied Cognitive Studies.

Hur, W., Moon, T., & Han, S. (2014). The role of chronological age and work experience on emotional labor: The mediating effect of emotional intelligence. Career Development International, 19(7), 734 – 754.

John, O.P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L.A. Pervin & O.P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd Edition), 102–138. New York: Guilford Press.

John, O.P., Hampson, S.E., & Goldberg, L.R. (1991). Is there a basic level of personality description?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 348-361.

Karasek, R.A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 285-310.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Karimi, L., Leggat, S., Donohue, L., Farrel, G., & Couper, G. (2013). Emotional rescue: the role of emotional intelligence an emotional labor on well-being and job stress among community nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(1), 176-186.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Kiffin-Petersen, S.A., Jordan, C.L., & Soutar, G.N. (2011). The big five, emotional exhaustion and citizenship behaviors in service settings: The mediating role of emotional labor. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(1), 43–48.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Kim, H. (2008). Hotel service providers’ emotional labour: The antecedents and effects of burnout. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27, 151-161.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Kirwan, M., Matthews, A., & Scott, P. (2013). The impact of the work environment of nurses on patient safety outcomes: A multi-level modeling approach. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50, 253–263.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Kramer, A., & Son, J. (2016). Who cares about the health of health care professionals? an 18-year longitudinal study of working time, health, and occupational turnover. ILR Review, 69(4), 939–960.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Lake, Eileen T. (2002). Development of the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index. Research in Nursing & Health, 25, 176-188.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Mann, S., & Cowburn, J. (2005). Emotional labour and stress within mental health nursing. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 12, 154–162.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Martin, A., Karanika-Murray, M., Biron, C., & Sanderson, K. (2016). The Psychosocial work environment, employee mental health and organizational interventions: Improving research and practice by taking a multilevel approach. Stress & Health, 32, 201-215.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Matthews, G., & Deary, I. (1998). Personality traits. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Maurer, T., Weiss, E., & Barbeite, F. (2003). A model of involvement in work-related learning and development activity: the effects of individual, situational, motivational, and age variables. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), 707-724.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

McCrae, R., & Costa, P. (1991). Adding Liebe und Arbeit: The Full Five-Factor Model and Well-Being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(2), 227-232.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

McCrae, R., & Costa, P. (2003). Personality in adulthood: A Five-Factor Theory perspective, (2d Edition). New York: Guilford.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Mechinda, P., & Patterson, P. (2011). The impact of service climate and service provider personality on employees' customer-oriented behavior in a high-contact setting. Journal of Service Marketing, 25(2), 101 – 113.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Meijman, T.F., & Mulder, G. (1998). Psychological aspects of workload, in Drenth, P.J., Thierry, H. and de Wolff, C.J. (Editions), Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology, 2nd ed., Erlbaum, Hove, pp. 5-33.

Morris, A., & Feldman, D. (1996). The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. The Academy of Management Review, 21(4), 986-1010.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Mroz, J., & Kaleta K. (2016). Relationships between personality, emotional labor, work engagement and job satisfaction in service professions. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 29(5), 767-82.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Oswald, A. (2012). The effect of working environment on workers performance: the case of reproductive and child health care providers in Tarime district. Master Thesis of Public Health Dissertation, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences.

Pelfrene, E., Vlerick, P., Kittel, F., Mak, R.P., Kornitzer, M. & Backer, G.D. (2002). Psychosocial work environment and psychological well-being: assessment of the buffering effects in the job demand–control (–support) model in BELSTRESS. Stress and Health, 18, 43-56.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Prentice, C. (2008). Trait emotional intelligence, personality and the self-perceived performance ratings of casino key account representatives. PhD thesis, Victoria University.

Ramaci, T., Barattucci, M., Ledda, C., & Rapisarda, V. (2020). Social stigma during COVID-19 and its impact on HCWs outcomes. Sustainability, 12(9), 3834.

Raziq, A. & Maulabakhsh, R. (2015). Impact of working environment on job satisfaction. Procedia Economics and Finance, 23, 717-725.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Robinson, D.G., & Robinson, J. (1996). Performance consulting: moving beyond training. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Schaubroeck, J., & Jones, J. (2000). Antecedents of emotional labour dimensions and moderators of their effects on physical symptoms. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 163-183.

Schaufeli, W.B., & Bakker, A.B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 293-315.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Siegrist, J., & Peter, R. (1996). Measuring effort–reward imbalance at work: guidelines. Düsseldorf: Heinrich Heine University.

Smith, M.A., & Canger, J.M. (2004). Effects of supervisor “big five” personality on subordinate attitudes. Journal of Business and Psychology, 18(4), 465-481.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Tervo-Heikkinen, T., Kvist, T., Partanen P., Vehvilainen-Julkunen, K., & Aalto, P. (2008). Patient satisfaction as a positive nursing outcome. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 23, 58-65.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Thompson, E.R. (2008). Development and validation of an international English big-five mini-markers. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(6), 542–548.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Van Den Broeck, A., Cuyper, N., Luyckx, K., & Witte, H. (2008). Employees’ job demands– resources profiles, burnout and work engagement: A person-centred examination. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 33(4), 691-706.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Wilson A., Zeithaml V.A., Bitner M.J., & Gremler D.D. (2012). Services Marketing. Integrating customer focus across the firm, McGraw-Hill Education,

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W.B. (2006). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121–141.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Yazdani, N. (2013). Emotional labor & big five personality model, presented in the 3rd International Conference on Business Management.

Yeh, S., & Huan T. (2017). Assessing the impact of work environment factors on employee creative performance of fine-dining restaurants. Tourism Management, 58, 119-131.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Zapf, D. (2002). Emotion work and psychological well-being a review of the literature and some conceptual considerations. Human Resource Management Review, 12, 237-268.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Zapf, D., & Holz, M. (2006). On the positive and negative effects of emotion work in organizations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(1), 1–28.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Zellars, K., Hochwartearn, W., Perrewe, P., Hoffman, N., & Ford, E. (2004). Experiencing job burnout: The roles of positive and negative traits and states. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(5), 887-911.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Zhong, J., Cao, Z., Hue, Y., Chen Z., & Lam, W. (2012). The mediating role of job feedback in the relationship between neuroticism and emotional labor. Social Behavior and Personality, 40(4), 649-656.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Received: 04-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. ASMJ-21-10658; Editor assigned: 06- Apr -2022, PreQC No. ASMJ-21-10658 (PQ); Reviewed: 20- Apr-2022, QC No. ASMJ-21-10658; Revised: 27-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. ASMJ-21-10658 (R); Published: 05-May-2022