Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 4

Emotional labor in healthcare: Patients and professionals perspective

Joana Carmo Dias, UNIDCOM/IADE - Universidade Europeia

Albérico Rosário, GOVCOPP, IADE - Universidade Europeia

Citation Information: Dias, J.C., & Rosário, A. (2022). Emotional labor in healthcare: Patients’ and professionals’ perspective. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 25(S4), 1-20.

Keywords:

Emotional Labor, Healthcare, Relational Engagement, Performative Engagement

Abstract

The emotional interactions and emotional management between healthcare professionals and patients are relevant but understudied phenomena. The value, meanings, attitudes, and strategies of emotional management may be associated with the perceptions of healthcare service quality, patients’ satisfaction and even health outcome. Therefore, this study attempts to explore the balance between expressing or suppressing emotions and negotiating closeness vs distance within the healthcare context. 78 Portuguese nurses, physicians and patients participated in a semi-structured interview and data were analyzed according to the thematic analysis of Braun and Clarke. The results suggested that healthcare professionals and patients may perceive the process of emotional management in two different ways: one that favors emotional display and a relational approach between professionals and patients, while the other favors emotional suppression or distance between interacting parties. These findings may help managers define and implement specific strategies regarding the role of emotions in service quality and customer satisfaction. This study provides novel evidence regarding healthcare professionals’ and patients’ perspectives about the emotional display during healthcare service encounters.

Introduction

In the context of healthcare, emotional management presents challenges to professionals and patients, due to the vulnerability of patients and the stress involved in the healthcare profession (Naz & Gul, 2011). In most cases, hospitalization represents a challenge for adults and for children as a hospital is usually perceived as an unfamiliar and frightening environment (Ceribelli et al., 2009). Minimizing the adverse feelings caused by hospital settings might include making them less intimidating and impersonal, namely through the humanization of care (Ceribelli et al., 2009). In order to do so, emotional dimensions of this context must be examined, including communication techniques and relational approaches. Therefore, this study aims to contribute to the understanding of such processes by exploring the emotional dimensions inherent to the context of healthcare, specifically in what concerns the construct of emotional labor.

Emotional labor, defined by Hochschild (1983) as the emotional management by professionals for purposes of relating with customers, is often necessary for healthcare to help professionals handle a problematic situation. Nurses, for instance, may have feelings towards a patient or a clinical situation that they do not consider adequate for display, due to their perceptions of patients’ expectations or to social and contextual norms (Mann, 2005). Behaviors associated with emotional labor help nurses to manage their patients' reaction by facilitating emotional relief and has a positive association with psychological and physical well-being and recovery (Mann, 2005).

Despite mounting support regarding the relevance of emotions in healthcare and the role of emotions for healthcare professionals and patients’ satisfaction (Chou et al., 2012; Karimi et al., 2013), the way healthcare professionals and patients consider emotions remains understudied. In this study, we want to understand how the display of emotions and the type of relationships that are established in this context are perceived and interpreted by healthcare professionals and patients. Hence, our research questions aim to understand what meanings are associated with emotional management by healthcare professionals and patients; and what is the association between emotional management and service quality and customer satisfaction.

Overall, this study provides three key contributions. Based on our findings and regarding the perceptions that healthcare professionals and patients report concerning the use of emotional labor, emotional labor is a two-way process that we called relational engagement and performative engagement. Indeed, the results suggest two different approaches, which are associated with what individuals identify as a good-quality service. Second, this study is the first qualitative study that considers the meanings associated with emotional management by both healthcare professionals and patients. Third, our findings provide specific and novel information to help healthcare managers define and implement strategies to achieve service quality and customer satisfaction.

Theoretical Framework

Managing Emotions at Work

In everyday life, the regulation of emotions is essential and cultivating positive emotions is even more vital. The ability to respond to the ongoing demands of experience with the range of emotions in a way that is socially acceptable (Cole et al., 1994) is called emotion regulation theory, that is, the bottom line of the emotional labor techniques (Gross, 1998). Emotion regulation is the conscious or non-conscious control of emotion, mood, or affect, that is, individuals can determine what emotion they should have, when they can feel these emotions, and how they express it (Gross, 2002). Gross (2002) developed a process model of emotion regulation that shows how specific strategies can be differentiated along the timeline of the unfolding emotional response (Gross, 1998; 2002). Emotion regulation is the most important for social interaction because it influences emotional expression and behavior directly. According to Mayer & Salovey (1997), individuals with great emotion regulation ability have a large repertoire of strategies for maintaining desirable emotions and for reducing negative emotions. Additionally, individuals with high emotion regulation ability report greater well-being (Côté et al., 2010), better quality social interactions (Lopes et al., 2005), and lower motivation for revenge (Rey & Extremera, 2014). Recognizing the usefulness of positive emotions, managers increasingly require the display of certain emotions in the workplace.

Emotional Labor

Service providers need to be emotionally prepared to effectively respond to customer interactions (Shani et al., 2014), as the work is not only denoted by intellectual and physical labor but also emotional labor, in terms of sincere concern about customers (Zapf, 2002; Jung & Yoon, 2014). Indeed, during a service encounter, service providers have an important role to play, since the customers’ perception of service quality is widely based on employee’s behaviors (Farrel et al., 2001) and how the customer-employee relationship unfolds. Lin & Lin (2011) pointed out that service encounter satisfaction will be more positive if the service employee’s affective delivery is also positive. The service providers’ attitudes, behaviors, motivation, job satisfaction and moods influence professionals’ performance and customers' evaluations of service encounters (Farrel et al., 2001). However, customers’ behaviors, that is, how pleasant or friendly the customer is to employees, can also have an impact on employees’ emotion regulation. As Rafaeli & Sutton (1987) observed employees and customers influence each other during an interaction and how customers react to employees’ emotion regulation can determine whether the employee experience that regulation as harmful or beneficial (Côté, 2005).

Emotions and their displays are controlled and managed in organizations, by formal and informal means (display rules), to ensure that some emotions are expressed while others are suppressed (Mann, 2005). Employees are expected to align with organizational emotional displays even when they conflict with inner feelings (Hwa, 2012). When this conflict results in suppressing genuine emotions or expressing fake emotions is called emotional labor. The concept of emotional labor was originally coined by Hochschild (1983) and is defined as the management of feelings to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display. Emotional labor can be considered as a sub-category of “emotion work”, since it has an exchange value, is sold for a wage, as opposed to emotion work that has no exchange value (Hochschild, 1983). Hence, it is related to the process of regulating feelings and expressions for organizational goals (Grandey, 2000). However, often a discrepancy arises between the organizational required emotions and employee’s inner emotions (Zapf & Holz, 2006), that is, emotional dissonance, when the expectation of certain behaviors concurs with employee’s authentic and personal feelings (Shani et al., 2014). According to Hochschild (1983), service providers use two strategies to cope with emotional dissonance: a) surface acting or ‘faking feelings’ to align with expectations; and b) deep acting or attempting to modify feelings to match expectations. Surface acting strategies occur when one performs an emotional display to meet certain rules and expectations. The display of emotions is considered to be inauthentic because the expressed emotions do not match the internal experience of the employee (Grandey, 2000; Côté, 2005). On the other hand, deep acting occurs when a person consciously attempts to feel a specific emotion that matches the expected emotional displays (Grandey, 2003). Service providers try to change what they feel to experience the emotions that they are expected to display (Groth et al., 2009).

Service providers’ emotional labor is valuable for the service industry, on which displays of positive emotions have been associated with customers’ satisfaction (Oliver, 1997), intention to return, service failure recovery (Zemke & Bell, 1990), customer attitude and others (Gursoy et al., 2011; Shani et al., 2014). On the other hand, being ‘forced’ to perform in expected emotional displays has been correlated with low job satisfaction, stress, low quality of life, exhaustion or depression (Gursoy et al., 2011; Karimi et al., 2013). Accordingly, some authors (Kim, 2008; Gursoy et al., 2011) draw attention to the fact that emotional labor has double-edge effects in terms of causing positive organizational outcomes and negative effects on employee well-being. For instance, in a study conducted within university’s staff, about the extent to which surface and deep acting can lead to emotional exhaustion, Gopalan & colleagues (2013) found that surface acting was positively correlated with emotional exhaustion and negatively correlated with life satisfaction. However, no correlation was found between deep acting and emotional exhaustion, and deep acting and life satisfaction. Most of research demonstrated that deep acting leads to more positive outcomes that do surface acting (Kim, 2008).

Emotional Labor in Healthcare

Every service setting is created to fill certain customers’ needs, even the healthcare setting. However, in most industries, the product or service can be standardized to improve efficiency and quality. In healthcare, every person is chemically, structurally, and emotionally unique. What works for one person may or may not work for another. In this environment, it is difficult to standardize and personalize care in parallel. Furthermore, patients’ perceptions of the quality of the healthcare they received are highly dependent on the quality of their interactions with their healthcare provider (Clark, 2003; Wanzer et al., 2004). Hence, the healthcare setting is in some respects different from the overall service industry and requires special management strategies to ensure both employees’ and customers’ satisfaction.

The relationships that are created between the employee (the healthcare provider) and the customer (the patient) is the aspect that most differentiates healthcare services from other services. These relationships have both emotional and informational components, that is, emotional care and cognitive care (DiBlasi et al., 2001). Emotional care includes mutual trust, empathy, respect, genuineness, acceptance and warmth (Ong et al., 1995). Cognitive care includes information gathering, sharing medical information, patient education, and expectation management (Kelley et al., 2014). Healthcare providers and patients experience an emotional connection among them; this means there is a rapport between the patient and the professional. This emotional connection has the power to relieve the patient’s suffering, in terms of reduced distress (Fiscella et al., 2004; Roter et al., 1995), greater hope and motivation to manage the patient’s illness (Thorne et al., 2008; Fox & Chesla, 2008), better treatment planning (Charon, 2006), better adherence to treatment plans (Berry et al., 2008), and better symptom resolution (DiBlasi, 2001; Haezen-Klemens & Lapinska, 1984; Hojat et al., 2011). When doctors and nurses experience an emotional connection with their patient, they feel a sense of achievement, and are thus more satisfied with their own work (Shanafelt, 2009; Shanafelt et al., 2009; McMurray et al., 1997; Dunn et al., 2007).

Considering these types of relationships, the emotional labor plays a key role for healthcare professionals regarding the quality of their service and patients’ perception of service quality. Emotional management has been deemed to be as important to healthcare professionals as their technical skills or abilities (Banning & Gumley, 2012). These authors found that nurses report that the humanistic elements of nursing care, such as offer sympathy, consideration, demonstrate sensitivity, empathy, emotional support, counseling and education, play an important role in the delivery of care. This arises as a particularly important issue when relating to chronic illness (Banning & Gumley, 2012). Oncology, for example, is one of the most challenging environments in healthcare, and healthcare professionals often develop strong emotional links with their patients (Banning & Gumley, 2012), due to the establishment of a personal connection or continued care.

Nurses are often expected to perform accordingly with their colleagues, patients and other medical staff expectations (Bartram et al., 2012). In a cross-sectional, correlational survey, conducted to 183 nurses, these professionals confirmed that they often need to module their emotions and display something else rather than what they are really feeling (Bartram et al., 2012). The same is valid for physicians, when they are revealing a bad diagnosis, or when they need to confront the family with the death of a relative (Bartram et al., 2012). Healthcare professionals do not really change their inner sense of felt. They modulate their external self to produce an acceptable and desirable response to go along with the treatment, bringing better outcomes on it and comfort for patients (Jimenez et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2013).

In turn, healthcare professionals can manage patients’ reactions, by providing comfort and allowing them to express their emotions, when they know how to perform emotional labor (Mann & Cowburn, 2005). According to these authors, nurses identified the management of emotions as having a key role in making patients feel better, more comfortable, and more satisfied. They also identified it as a critical aspect of day-to-day work, expressing that it helps to “oil the wheels of nursing work” (Mann & Cowburn, 2005). Emotional labor is like an invisible bound that helps patients to be satisfied, show better treatment outcomes and even facilitate catharsis (Mann & Cowburn, 2005). In their study about nurses' views and emotions, Banning & Gumley (2012) concluded that these healthcare providers felt that the expression of compassion, empathic understanding and positive feelings towards patients were essential features of their work. The authors also concluded that "nurses who have little or negligible positive feelings, and emotions towards patients would have difficulties expressing their views and providing care for patients" (Banning & Gumley, 2012).

In addition to the fact that nursing is one of the occupations most prevalent to requiring extensive emotional labor (Bolton, 2001), emotional labor can be an important strategy for nurses and physicians because it increases self-efficacy – the belief that one can fulfill successfully the requirements of a given task – and task effectiveness (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1993). According to Henderson (2001), nurses are encouraged to demonstrate emotional involvement and commitment to create a less formal nurse-patient relationship and to improve patient outcomes. If nurses demonstrate emotional impassiveness, as when some show unconcern for a customer distress or when social rules are not followed, it can result in poor outcomes for patients (Bolton, 2000). As Smith (1992) discussed a study targeting the public’s expectations regarding the characteristics and emotions displayed by nurses, positive attitudes and feelings seemed more important than technical expertise. Bolton’s study (2000) also demonstrated that maintaining an emotional distance reduces attachment to such an extent that professional ability decreases.

As Mann and Cowburn (2005) put it, “the nurse who performs emotional labor is able to manage the reaction of the patient by providing reassurance and allowing an outlet for emotions”. Such emotional labor can also be therapeutic, due to its impact on patients' psychological and physical well-being (Phillips, 1996). Increasingly, the enhanced autonomy and use of technology in nursing, together with staff shortages and heavy workloads, has reduced the time and energy available for emotional labor (Jimenez et al., 2012). Zander & Hutton (2009) draw our attention to the fact that, although nurses understand the emotions they are going through, it is necessary to ensure that their own expressed emotions enable patients’ appropriate care. Emotional labor in nursing is not highly valued by most healthcare organizations (Hunter & Smith, 2007), which explains the link between emotional labor, emotional exhaustion and job burnout. Nurses’ emotional exhaustion results ultimately in depersonalization of the service (Grandey et al., 2007).

Regarding nurses, their common social representation includes displaying caring, kindness, sympathy, get involved and be concerned about patients (Henderson, 2001). Physicians are expected to be dedicated, supportive and sympathetic (Naz & Gul, 2011). According to a study by Mackintosh (2000), patients’ expectancy of these roles carries high expectations towards healthcare professionals and brings pressure to be up to those social representations, or otherwise they will not be delivering a good service. In fact, given that social representation and the extreme importance of the communication process between patient and healthcare professional it becomes clear that nurses, physicians and other healthcare employees must keep up to the challenge or otherwise they will be compromising patients’ satisfaction and ultimately treatment effectiveness (Naz & Gul, 2011).

Patients’ satisfaction is highly related with emotional labor (Rego et al., 2010). Patients that perceive healthcare professionals to be kind, use soft voice and gentle manners are much more prone to feel satisfied (Hayward & Tuckey, 2011). Patients tend to feel more satisfied with healthcare services when they experience that their one’s emotions are understood; when healthcare professionals pay attention and try to understand emotion they enhance patients’ trust and respect (Rego et al., 2010). On the contrary, when healthcare professionals fail to understand patients’ emotions or neglect attention given to them, they become less likely to share their true feelings or communicate effectively. According to Henderson (2001), patients are more likely to present positive treatment results and satisfaction if nurses can consciously monitor and moderate their own emotional responses.

As we can see throughout the literature and despite being a widespread topic of study, most research on emotional labor has focused only on the display of emotions in a service encounter (Barger & Grandey, 2006; Rafaeli & Sutton, 1990; Pugh, 2001; Yagil & Medler-Liraz, 2013; Sutton & Rafaeli, 1988), and on the negative effects of emotional labor on service providers (Grandey, 2000; Zapf & Holz, 2006; Grandey, 2003). Thus, to date research regarding the perceptions of the display of emotions that plays a key role in healthcare services is still scarce.

Methodological Aproach

Research Design

Since our focus was to explore the perceptions associated with the role of emotions during healthcare service interactions, we developed a qualitative study with semi-structured interviews aimed at exploring and understanding the patterns and processes inherent to the display of emotions. This method offers a balance between the flexibility of an open-ended interview and the focus of a structured survey. The semi-structured interviews are open, allowing new ideas to be brought up during the interview as a result of what the interviewee says. Also, it provides reliable, comparable qualitative data and can uncover rich descriptive data on the personal experiences of participants (Bernard, 2000).

As a data analysis strategy, we chose thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to identify, analyze and report such patterns within data. Thematic analysis targets the identification of implicit and explicit ideas within the data (Guest et al., 2011), emphasizing a rich description. Coding is the primary process for developing themes within the raw data, a process involving the recognition of important moments in the data and its encoding prior to interpretation (Boyatzis, 1998). Interpretation of these codes may include comparing theme frequencies, identifying theme co-occurrence, and graphically displaying relationships between different themes (Guest et al., 2011). Thematic analysis has been considered as a valid method of capturing the intricacies of meaning within a data set (Guest, 2012).

Participants

We conducted 78 interviews with Portuguese nurses, physicians, and patients. These participants were recruited at one public hospital, one health center and one private clinic in the north of Portugal. All these institutions deal with more than one valence, so this research does not focus on any medical and nursing specialty. The sample consisted of 52 healthcare professionals – 19 physicians (10 women and 9 men) and 33 nurses (24 women and 9 men) – and 26 patients (18 women and 8 men). The ages of the elements of the three groups of participants ranged from 20 to 87 years old (Mphysicians =44, 95; Mnurses =36, 10; Mpatients =44, 80).

Data Collection

Data were collected through selective sampling, as the participants were selected by considering their knowledge and experience regarding the topic of research. Criteria for selecting participants included having high contact with patients, and, at least, two years of work experience – for physicians and nurses – and going at least once a year to a healthcare institution – for patients. Patients were randomly approached to respond to an interview, within the space of the healthcare institutions. The first question "How often do you usually go to a hospital, health center or clinic?" was the elimination factor of these participants. Nurses were indicated by the head nurse and the doctors, in turn, by the directors of the institutions they work in.

Interviews took place at nurses' and physicians’ workplace, during their shifts, and in the hospitals’ lobby. Each interview lasted approximately one-hour, except for five interviews, which due to busy schedules only lasted 30 minutes. We developed two similar provisional interview scripts. For nurses and physicians, the script had seven open-ended questions and, for patients, five. Regarding healthcare providers’ interview, we asked them, for example, to describe their interactions with patients, how they manage their emotions in front of the patient, what they think are the main determinants of service quality and to tell a story that affected them in a professional and personal level. To the patients we asked, for example, to describe their emotions when they are in a healthcare institution, how they think healthcare professionals should manage their emotions, how the relationship between patients and healthcare provider can influence perceptions of service quality and what they think are the main determinants of service quality. We adapted the scripts by adding or deleting questions, as the data collection and analysis evolved, to obtain a better and deeper comprehension of the main categories.

We obtained written consent to take part in the study and permission to audio-record the interviews from every participant. We also informed them about the research aims and assured them about the confidentiality of the data collected. This study was approved by the hospitals’ ethics committee.

Data Analysis and Findings

We recorded and transcribed the interviews verbatim and analyzed them through the qualitative software QSR Nvivo 12. After 60 interviews, several themes developed into clear patterns became commonplaces, since numerous participants mentioned them. Therefore, we conducted some more interviews to obtain a more reasoned confirmation of the theoretical saturation. We then closed the process of data collection.

We transcribed all the interviews into field notes (624 pages), listening carefully to all the audios and transcribing them to word documents, and then we searched for relations between ideas and created codes. We organized the data through the qualitative software QSR Nvivo 12, according to the following steps: 1) becoming familiar with the data, we read and re-read data in order to become familiar with what the data entails, paying specific attention to patterns that occur (Guest et al., 2011); 2) generating the initial codes by documenting where and how patterns occur. This happens through data reduction where data is collapsed into labels in order to create categories for a more efficient analysis (Saldana, 2009); 3) searching for themes, combining codes into overarching themes that accurately depict the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006); 4) reviewing themes, we look at how the themes support the data and the overarching theoretical perspective (Guest et al., 2011); 5) defining and naming themes, we defined what each theme was, which aspects of data were being captured, and what was interesting about the themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006); and, finally, 6) producing the report, which entails decisions regarding which themes make meaningful contributions to the understanding of what is going on within the data (Guest et al., 2011).

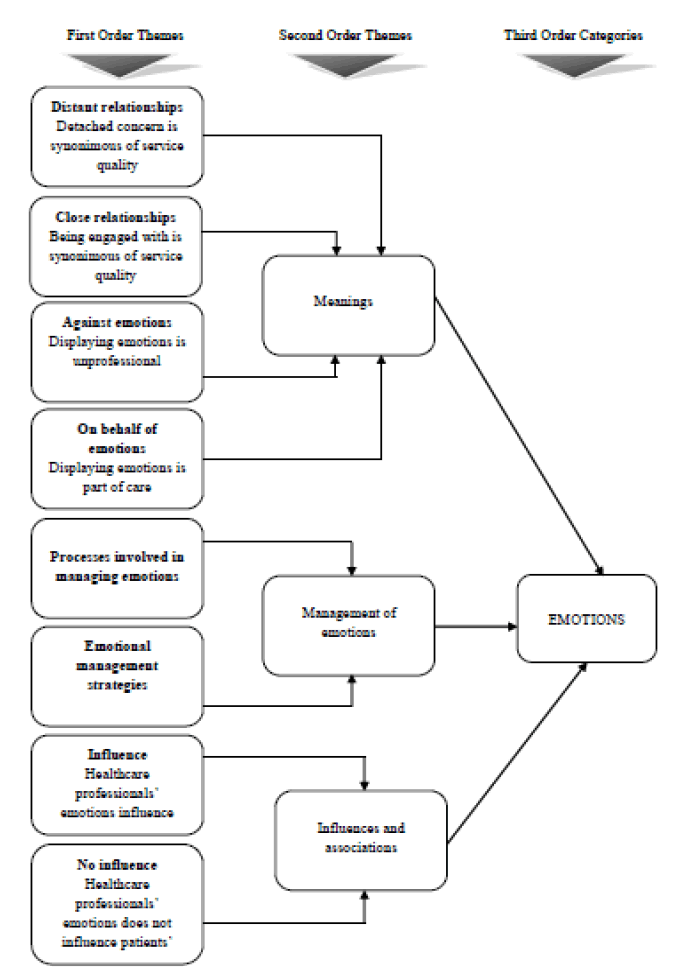

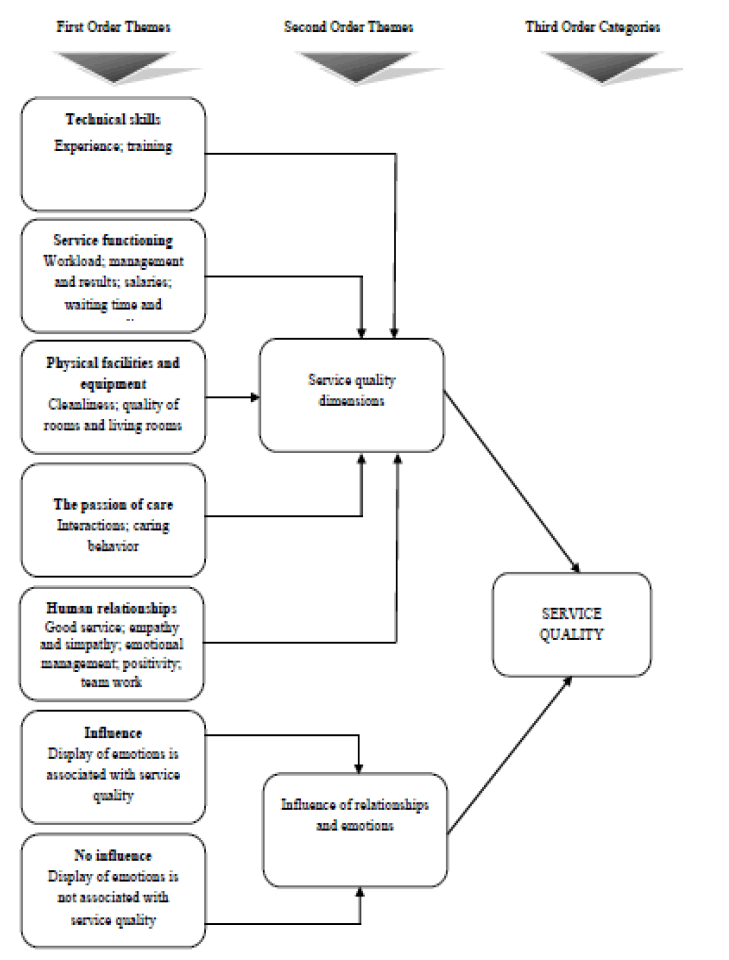

Figure 1 and 2 presents the main results from the thematic analysis. Figure 1 is related to the topic of emotions , under which we found themes such as meanings , management of emotions and influences and associations . The theme meanings refer to the meanings attributed to the emotional experiences of healthcare professionals and patients. Therefore, is possible to identify two different positions: 1) the management of emotions as fundamental in caring for the patient, underlining the importance of the continuous relationship between the same healthcare professional and patients (close relationships and on behalf of emotions ); and 2) a negative view of emotional experience and expression, viewing it as a non-professional stance, and giving more focus to the patient rather than maintaining a continued relationship (distant relationships and against emotions ). The theme management of emotions presents the processes and strategies mentioned by participants (e.g. being authentic, controlling emotions, faking emotions). Finally, the theme influences and associations relate to which kind of associations exist between the healthcare professionals display of emotions and patients’ well-being. Figure 2, in turn, is related to the service quality . Under this topic we found the main service quality dimensions , such as technical skills (e.g. experience, training), service functioning (e.g. workload, salaries, waiting time), physical facilities and equipment (e.g. cleanliness, quality of rooms), and passion of care (e.g. interactions, caring behavior). Also, we found whether the display of emotions was associated with service quality.

Relationships as ‘The Key to our Business’

According to figure 1, one of the meanings attributed to the management of emotions reveals that participants found the display of emotions and close relationships between healthcare professionals and patients – which we named as relational engagement – as fundamental to service quality. The display of emotions means that nurses and physicians share their feelings with their patients and show empathy, concern, interest, which is the opposite to the detached concern, that is, to be concerned about something without being emotionally involved (Halpern, 2001). In addition to show concern for the patients, healthcare professionals also get emotionally involved, both with the patient and with the situation (s) he is going through. The expression of emotions is believed to be a way to reinforce the proximity between professionals and patients and therefore serves as a facilitator of their physical and mental recovery, and ultimately of their satisfaction. The proximity and the relationship established between healthcare professionals and patients were also suggested as crucial in providing a personalized treatment, and creating trust, confidence, and hope among patients. There is a reciprocal connection between displaying emotions and relationships in the sense that the expression of emotions makes people become closer and intimate and relationships, in turn, urge individuals to share emotions.

In their study, Brooks & Phillips (1996) concluded that nurses believe that their emotional involvement was associated with a more positive result to their patients. Our nurses, also agree with this conclusion. The following statement summarizes this perspective on service quality: “No doubt the quality goes through the humanization of the service, with the nurse being the first link that connects the patient to the services and perpetuates the perception of good or bad hospital’s quality.” (Nurse [N] 13).

The importance of managing emotions also relies on the fact all feelings and emotions that nurses and physicians express affect patients’ feelings and emotions, which will impact their attitudes and behaviors, either positively or negatively (Andersen & Kumar, 2006). According to physicians and nurses, the display of emotions, if well managed, can be beneficial to patients’ well-being. McQueen (2004) stated that the quality of care can be improved when nurses engage with patients and anticipate their needs and wishes. In addition, physicians reported that emotions can act as a medicine for any disease and nurses understand that the way they treat patients can change a patient’s day: “The tranquility that we can transmit to patients is able to make them leave the office without the need for drugs.” (Physician [Ph] 10). Some patients also illustrated this view that the display of emotions is helpful for improving their psychological well-being, reporting some situations:

“I had a physician who was a very close friend, was very caring and concerned about me and it affected me because it made me feel good. So, the way he showed certain emotions affected and altered my state of mind. And it also happens with negative things. Once, I was operated by a physician who never spoke to me, at that time I was so upset.” (Patient [P] 8)

This claim also showed that the strong bonds between patients and healthcare professionals make patients return to that healthcare institution. Goff & colleagues (1997) stated that customers perceive employees as part of the company and positive feelings towards them, carry over to feelings towards the organization. Also, these bonds appear to result from patients’ desire to be attended by the same nurses and the same physicians over time. They suggested that it is the only way to get a personalized service:

“A patient is a weakened person, so, sometimes, it is important to establish a stronger connection with a particular professional. That person already knows you, so it gives you courage and strength. They know what your needs are, fears, concerns and so the patient is now more comfortable and, perhaps, also feel safer.” (P2)

Nurses stated that they often have close relationships with patients, describing them as "almost friendship" (N19). Nurses reported an attempt to get involved in patients’ lives as they perceive that this is advantageous for their recovery and for the creation of a positive atmosphere. A service encounter composed by caring and individualized attention that the service provider gives to customers takes on added significance (Wong & Sohal, 2003), as illustrated by this nurse’s personal experience:

"There were moments in my career where I cried with patients' parents. When some situations have a great impact on the family, e.g. diagnosis of a chronic disease, I feel involved too. And with those children that I had the first contact I feel that I am a little more emotionally connected..." (N5)

As we already seen, relationships between patients and healthcare professionals are important to these individuals. They see relationships as crucial to service quality; when there seems to be a poor relationship; service quality is perceived as compromised. Brady & Cronin Jr’s (2001) study of a new and integrated conceptualization of service quality pointed in the same direction, stating that service providers' empathy is determinant to delivering good service quality. In addition, DiBlasi, et al., (2001) stated that when physicians are warm, friendly and reassuring with their patients they are more effective. Physicians reported that when the relationship between healthcare professionals and patients is not positive, the patient cannot take full advantage of the service. Thus, all participants appeared to believe that the technical part of the service delivery does not constitute the whole of the service quality. Unlike in the past, recently there has been an increased appreciation of involvement and commitment in healthcare services (McQueen, 2004).

Performances as ‘The only Thing that Really Matters’

The other meaning attributed o the management of emotions and presented in figure 1 – which we designated as performative engagement – relates to the idea that some participants considered emotions as unnecessary to service transactions and that they might even have negative consequences. The job detachment seems to be the reason why healthcare professionals perceived emotions in this way: “I use strategy and game tactics. Zero empathic relationship for my protection. Since I enter and leave the hospital my relationship is purely professional” (N30). They believed that service quality can only be achieved when healthcare professionals maintain a professional distance from patients and focus their attention exclusively on the technical part of the service performance.

In this approach, healthcare professionals try to have a great control of their emotions, avoiding display to patients, as they appeared to believe their work should only be based on technical prowess. As Erickson & Grove (2007) agreed emotions should be controlled to the benefit of the employee and organizational effectiveness. A physician explained why he doesn’t want to show emotions: “I try to clarify and calm down patients and I try to control myself and not to show emotions, because, if I show emotions to a patient with a serious illness, it can complicate the situation.” (Ph3). Some patients agreed with these conclusions: “I think that nurses should control their emotions, because I think it aggravates the psychological state of a person. Healthcare professionals should always be serene, calm and not show pity in relation to any disease.” (P2).

Emotions, according to these individuals, may create unnecessary alarmism, worsening patients’ psychological state. In addition, patients considered that, if healthcare professionals are too emotional, that is, if they show what they feel about the situation the patient is going through, it may interfere in healthcare. Thus, these individuals suggested that professionals should not get too involved with patients but attempt to be more rational and less emotional. Henderson (2001) showed in her study a similar opinion from nurses, saying that “too much emotional engagement may render the nurse incapable of doing the job”. In addition, some nurses viewed detachment to ensure effective nursing or to self-protect against harm. This perspective is clearly illustrated by some patients: “I think that healthcare professionals should act with rationality, however, this should not be confused with detachment and coldness towards the problems experienced by patients.” (P4). According to these patients, the ideal service delivery is a personalized service, showing concern and interest in the patient, maintaining empathy, and not going beyond the emotional level: “Nurses and physicians should act professionally above all. They should ask the questions they consider necessary to make the correct diagnosis. They must have delicacy and compassion for the sick and be unbiased towards particular responses and patients’ behavior.” (P7).

Physicians stated that they shouldn’t show their inner emotions but give at least the impression that they are emotional and sensitive beings, just like patients. Furthermore, they reported they should neither spoil patients nor have personal conversations with them to the extent that this involvement can negatively affect patients' well-being. Physicians want to be serious, clear, objective and professional. Also, they are somewhat less emotionally involved because they spent less time contacting with patients (Argentero et al., 2008). These performance’s characteristics were present throughout the interviews: “I try to be fair, to be correct and friendly. But the patient is not my father, my brother or my friend, so there must be a certain distance. I can separate things and turn off from situations.” (Ph2).

Meanwhile, some nurses mentioned they must not create and maintain any closeness with patients, since it can affect the experience of both healthcare provider and patient, in relation to the disease. However, is based on literature that nursing leaders engaging in relationships will facilitate successful management (McQueen, 2004). Still, these nurses considered that emotions do not add any value to the service provided. For them, the most important service quality factor was the quality of equipment, teamwork, and technical skills. This view has been commonly argued in the literature, that nurses try to maintain a professional barrier and avoid becoming emotionally involved with patients and so discourage human interaction (McQueen, 2000). For some nurses, interactions with patients were inadequate: “From the moment they [patients] come in until they go away, my relationship and connection remain professional. Empathy is dangerous to my sanity. I keep it to my family.” (N29).

Patients also agreed that their relationships with healthcare professionals did not influence their judgment about the overall service quality. Clemes, et al., (2001) confirmed that patients give more importance to service quality dimensions that refer to the core product, which is to successfully treat a medical condition. Some patients explained why they don’t agree that their relationship with healthcare professionals’ influences service quality: “I think this is a bit misleading, because they can be friendly and attentive and able to put us at ease, but they also can be incompetent. So, I do not associate the two things, are different things, so a good relationship with a physician or nurse does not mean that the quality of service is excellent.” (P13). Patients also showed they didn't have a special preference for any healthcare professional; they only wished nurses and physicians to be friendly and professional, as they believed that they could not create bonds of friendship with them.

Furthermore, nurses, physicians, and patients agreed that there was no emotional impact, since they were all able to move away from emotional situations. They were not influenced by situations that they witnessed as they keep a distance that allows them to act professionally, as some nurses explained: “I act diplomatically. I remain stable and, sometimes, I don’t listen to the dubious complaints of patients. I'm indifferent and I remain neutral.” (N26).

However, there seemed to be a behavioral influence on the extent that when patients are more aggressive healthcare professionals would also tend to be so, and vice versa. A nurse said “My way of being at work depends on the patient and the way (s) he presents himself/herself in the room. If (s) he is polite, I make a regular contact without changing. If (s) he is aggressive, I use cynicism and sarcasm, are infallible weapons to disarm them.” (N27); and a patient said, “From physician to patient, there is an influence because, if the physician is angry, moody and we notice that we became uncomfortable: nobody likes to be treated by someone with this psychological state.” (P3).

Discussion

The emotional interactions and emotional management between healthcare professionals and patients are relevant but an understudied phenomenon. Healthcare professionals’ values, meanings, attitudes and emotional management strategies and its perceptions by patients may be associated with the perceptions of healthcare service quality, patient satisfaction, and even health outcome. Therefore, this study attempts to explore the balance between expressing or suppressing emotions and negotiating closeness vs distance within the healthcare context.

Our findings suggest that there is a dualistic view regarding the management of emotions in healthcare services (Figure 3), namely a reliance on emotions to develop connections – relational engagement – or, in contrast, an emotional control which deflects attention to the technical skills – performative engagement. The first perspective, which is already reported by the literature, underlines the importance and the expression of emotions to establish or develop a close relationship between healthcare professionals and patients, serving also as a facilitator of their physical and mental recovery and experience in the healthcare unit. Hence, this perspective of relational engagement is advocated when the proximity between professionals and patients is considered essential to the execution of a personalized treatment and to create confidence and hope among patients.

On the other hand, the second perspective - performative engagement – is a novelty for the literature of managing emotions in healthcare. This perspective values the importance of healthcare professionals’ technical capabilities over the use of emotions in their relationship with patients. The display of emotions is deemed unnecessary and even detrimental, since it may adversely affect the relationship between professionals and patients, increasing stress and burnout among them. Thus, these professionals tend to control and suppress their emotions.

Although we found these two different perspectives, the second one was the most frequently reported by respondents from the three groups (nurses, physicians, and patients). However, the performative engagement perspective is contrary to what the literature supports. The literature advocates that nurses themselves consider that the management of emotions is a key role in making patients feel better, more comfortable, and more satisfied (Mann & Cowburn, 2005). This is due in part to social expectations that perceive healthcare professionals as managers of care (Bolton, 2000; Larson & Yao, 2005). Nurses are expected to have not only professional competence but also the necessary sensitivity to meet patients’ vulnerability and anxiety (Akerjordet & Severinsson, 2004).

Also, the literature claims that there is a shift from a detached concern for patients, i.e., when nurses are concerned about someone without being emotionally involved, to a wish to be emotionally engaged with them (Halpern, 2001; Cadge & Hammonds, 2012) and nowadays emotional labor it is an indispensable aspect of patient care (Hochschild, 1983; Henderson, 2001; Mann, 2005). However, according to our results, there are still a great number of nurses and physicians that prefer to be emotionally detached from their patients, and healthcare managers have to be aware of these professionals’ perceptions in order to set strategies to overcome this issue. We hypothesize that this situation occurs because of three main reasons: 1) nurses and physicians feel the need to protect themselves; 2) they believe that this is the best way to give a quality service to patients; and 3) they are not motivated to emotionally engage with their patients. A study by Kerfoot (1996) that focused on nurse manager's challenge confirms our results, arguing that patients experience many situations where they receive excellent technical care, but the emotional side of their care is not met.

Regarding patients’ perceptions about the management of emotions, most patients give great importance to relationships and to positive interactions with healthcare professionals, because they consider that this is a key factor in service quality. The display of emotions makes the professional more human and makes patients feel better. For example, in the case of patients with a more serious health condition, it is good to realize that physicians and nurses also have personal problems. Nevertheless, there are other patients that do not want healthcare professionals to be emotionally engaged with them, because they consider that it may interfere with care and can also create alarmism among patients because they do not have the sufficient knowledge to evaluate the technical part of the service. Also, these patients consider that healthcare professionals should work more with reason and less with emotion.

Our findings are partially consistent with the literature on emotions in healthcare. Some studies about nurses’ behaviors and relationships between nurses and patients concluded that patients feel cared for when nurses treat them as individuals and are supportive and available to them, anticipate their needs and appear confident in their work (Godkin & Godkin, 2004; Hines, 1992). The study from Williams (1997) about patients’ perceptions concluded that patients give more importance to nursing care that recognized them as a unique individual with a need to share feelings and to have someone listen to them. Patients also reported that nurses’ affective activities are more important for quality nursing care than their technical skills.

Even so, a possible explanation for this dualistic view about managing emotions can be what Fotiadis & Vassiliadis (2013) found: a patient’s satisfaction with healthcare services depends on their individual preferences, personality, and experience, and on their personal experiences during their illness. We also argue that these two perspectives can be related to the type of patients, that is, patients who go to the hospital often, almost daily, argue that healthcare professionals should foster close relationships among them, while patients who go sporadically to the hospital, for example once or twice a year, consider that this emotional side is unnecessary for patient care.

Several studies appear contradictory with our findings such as the work of Bitner, et al., (1990); Allen, et al., (2010), that argued that employees’ behavior was determinant for customers evaluation of the service; and the work of Pugh (2001) that stated that the display of positive emotions by employees was positively related to customers’ evaluations of service quality. Our study reaches a different conclusion because emotional labor was not associated with service quality. Actually, most participants did not indicate the relationships between healthcare professionals and patients and the management of emotions as essential for the quality of service. In fact, is patients’ waiting time and healthcare professionals’ punctuality that were considered more important. A possible explanation is that both healthcare professionals and patients do not value so much the use of emotions and the relationships they maintain with each other, as they value other factors for the service quality. Furthermore, the interviews were conducted in public hospitals, which possibly are still viewed only as cure centers and not as care centers.

However, all three groups of respondents, when directly asked about emotions, said that emotions and the relationships between healthcare professionals and patients influence their perception of service quality. There is still to add that, interestingly, participants who responded negatively to this question, i.e., they consider that the management of emotions and the relationships do not influence the perception of the service quality, were only patients. Despite respondents consider that emotions and relationships between healthcare professionals and patients have some influence on service quality perception, they do not consider these to be a service quality determinant.

Implications

The present study presents a dualistic view regarding emotions in the workplace: healthcare professionals’ reliance on emotions to develop connections – relational engagement – or healthcare professionals’ emotional control which deflects attention to the technical skills – performative engagement. But from these two perspectives, most nurses and physicians tend to control their emotions and to detach themselves from patients because they feel the need to protect themselves. They believe that this is the best way to give a quality service to patients and they are not motivated to emotionally engage with their patients. This is an important challenge in services and, in the case of healthcare it represents a major challenge for administrators. They must adopt certain strategies that will answer the question about what is the right thing for the healthcare institution to do in order to deliver a good service quality: to show or to hide emotions? In this sense, managers should focus on the experience and expression of emotion during service encounters to know how to train healthcare professionals to deliver a better service. Also, managers should be aware of on which conditions healthcare professionals refuse to do emotional labor to be able to counteract this trend.

Another implication is that healthcare organizations might benefit from communicating their emotional labor requirements during the selection process to help individuals decide whether their expressive behavior matches the organization’s display rules. However, the organization must also provide the appropriate conditions for professionals to be motivated to do emotional labor.

In sum, emotional labor should not be understood as something that has a negative impact on employees’ well-being (Grandey, 2000; Zapf & Holz, 2006; Grandey, 2003), but on the contrary, when properly understood by them, has positive effects both on employees and on customers, gaining special emphasis in healthcare services, because, as Banning and Gumley (2012, 804) states, “it is impossible to extract the human element of nursing from the provision of nursing care”.

Our findings suggest that healthcare professionals perceive the management of emotions and the establishment of relationships with patients as unnecessary and even detrimental to service quality. Therefore, there is a need for managers to encourage nurses and physicians to engage in positive behaviors when interacting with patients, regardless patients’ behavior. Even if patients are unpleasant and hostile, healthcare professionals should maintain their positive attitude and additionally express positive emotions.

Limitations and Future Research

Our main limitations are related to the generalizability of the qualitative results, the limited duration of the interviews, due to low availability of participants, and a large gender disparity, with more women than men participating in the study. Another constraint that may have influenced our study was the geographical scope of our sample, restricted to the north of Portugal, in a specific economic and social moment, albeit one that resembles many other European countries undergoing a social and economic crisis. Furthermore, the interviews were conducted in public hospitals, which possibly are still viewed only as cure centers and not as care centers.

Also, due to its exploratory nature, this study only focused on how healthcare professionals and patients perceive the management of emotional labor in an overall manner, not taking advantage of more specific issues that may explain the phenomenon that results from this investigation. Particularly, it would be interesting to explore with a quantitative approach the personal and contextual antecedents that can be associated with a more critical or distanced relational approach to patients and a more empathic one. Furthermore, focusing on the type of patient, considering how often they go to the hospital, it would be an interesting topic of study.

Future research should also explore if this phenomenon occurs in a variety of clinical specialties and in private and public healthcare institutions as well as the circumstances in which it occurs. We could also apply these new concepts – relational engagement and performative engagement – in other types of services where there is an intense interaction between service providers and customers. Further studies targeting specific emotional labor strategies, namely observational studies, would bring much needed information on the efficacy and well-being correlates for both patients and professionals. Also, in-depth interviews that explore the individual psychological mechanism underlying such specific strategies should shed light on a much-understudied subject.

Conclusion

This is the first qualitative study about the value, meanings, attitudes, and strategies of emotional management by healthcare professionals and its perceptions by healthcare professionals themselves and by patients. Our study contrast with the literature – that states that nurses are care managers – suggesting a dualistic view regarding emotions in the workplace. Not only healthcare professionals but also customers portrayed emotional expression in a positive and in a negative way. In other words, some healthcare professionals and patients identified with a relational engagement approach during the service encounter and attributed it to the way they see emotions as an asset in treating patients’ diseases and improving their psychological well-being. For this group of participants, emotions were considered intrinsic to the healthcare service. Other healthcare professionals and patients identified with a performative engagement approach, to the extent that they perceived the display of emotions as useless or even as having a negative impact on their work roles and on patients’ physical and psychological condition. They tend to act neutral or to show their true emotions, whether positive or negative, in response to patients’ emotions, driven by job dissatisfaction, stress and burnout. These different perspectives are due to the fact that the meaning attributed to “emotions at work” may vary from person to person (Gosserand & Diefendorff, 2005) and may be also due to several factors such as working conditions, healthcare professionals’ motivation, physicians’, nurses’ and patients’ perceptions of service quality, type of patients, and patients’ personality and experiences, among others. For that reason, the expression of emotions and empathy must not be mistaken for the establishment of personal or intimate interactions beyond the purpose of a relationship between a healthcare provider and a customer. It is, instead, something that should be perceived as part of the job (Henderson, 2001), with the purpose of promoting patient’s psychological well-being, ultimately actively contributing to the creation of a positive environment during the service performance. Future research should pursue the objective of studying healthcare providers reinterpretation and consolidation of a new professional identity that, besides goal-oriented, is also person-oriented. The goal of healthcare is well-being, which has a psychological and physical dimension and therefore, any attempts to detach it from the human factor will result in a loss of quality.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to the Editor and the Referees. They offered extremely valuable suggestions or improvements. The authors were supported by the GOVCOPP Research Center of Universidade de Aveiro, and UNIDCOM, IADE - Universidade Europeia. Joana Carmo Dias has financial support from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (through project UIDB/00711/2020).

References

Akerjordet, K., & Severinsson, E. (2004). Emotional intelligence in mental health nurses talking about practice. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing , 13 (3), 164–170.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Allen, J., Pugh, S., Grandey, A., & Groth, M. (2010). Following display rule in good or bad faith?: Customer orientation as a moderator of the display rule-emotional labor relationship. Human Performance , 23 , 101-115.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Andersen, P., & Kumar, R. (2006). Emotions, trust and relationship development in business relationships: A conceptual model of buye-seller dyads. Industrial Marketing Management , 35 , 522-535.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Argentero, P., Dell?Olivo, B., & Ferretti, M. (2008). Staff burnout and patient satisfaction with the quality of dialysis care. American Journal of Kidney Diseases , 51 (1), 80-92.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Ashforth, B., & Humphrey, R. (1993). Emotional labor in service roles: The influence of identity. Academy of Management Review , 18 (1), 88–115.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Banning, M., & Gumley, V. (2012). Clinical nurses? expressions of the emotions related to caring and coping with cancer patients in Pakistan: A qualitative study. European Journal of Cancer Care , 21 , 800–808.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Barger, P., & Grandey, A. (2006). Service with a smile and encounter satisfaction: Emotional contagion and appraisal mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal , 49 (6), 1229-1238.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Bartram, T., Casimir, G., Djurkovic, N., Leggat, S., & Stanton, P. (2012). Do perceived high performance work systems influence the relationship between emotional labour, burnout and intention to leave? A study of Australian nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 68 (7), 1567–1578.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Bernard, R. (2000). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Berry, L., Parish, J., & Janakiraman, R. (2008). Patients? commitment to their primary care physicians and why it matters. The Annals of Family Medicine , 6 (1), 6-13.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Bitner, M.J., Booms, B.H., & Tetreault, M.S. (1990). The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. Journal of Marketing , 54 , 71-84.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Bolton, S. (2000). “Who cares? Offering emotion work as a “gift” in the nursing labour process. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 32 (3), 580–586.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Bolton, S. (2001). Changing faces: Nurses as emotional jugglers. Sociology of Health & Illness , 23 (1), 85–100.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Boyatzis, R. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development . California: US, Sage Publications. Crossref,

Brady, M., & Cronin, Jr. (2001). Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: A hierarchical approach. Journal of Marketing , 65 , 34-49.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology , 3 (2), 77-101.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Brooks, F., & Phillips, D. (1996). Do women want women health workers? Women's views of the primary health care service. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 23 (6), 1207–1211.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Cadge, W., & Hammonds, C. (2012). Reconsidering detached concern: The case of intensive-care nurses. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine , 55 (2), 266-282.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Ceribelli, C., Nascimento, L., Pacifico, S., & Lima, R. (2009). Reading mediation as a communication resource with hospitalized children. Latin American Journal of Nursing , 17 (19), 81–87.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Charon, R. (2006). Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness . New York: Oxford University Press.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Cheng, C., Bartram, T., Karimi, L., & Leggat, S. (2013). The role of team climate in the management of emotional labour: implications for nurse retention. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 69 (12), 2812-2825.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Chou, H., Hecker, R., & Martin, A. (2012). Predicting nurses’ well-being from job demands and resources: A cross-sectional study of emotional labour. Journal of Nursing Management , 20 , 502-511.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Clark, P.A. (2003). Medical practices’ sensitivity to patients’ needs: Opportunities and practices for improvement. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management , 26 (2), 110-123.

Crossref,Google Scholar, Indexed at

Clemes, M., Ozanne, L., & Laurensen, W. (2001). Patients’ perceptions of service quality dimensions: An empirical examination of health care in New Zealand. Health Marketing Quarterly , 19 (1), 3-22.

Cole, P., Michel, M., & Teti, L. (1994). The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development , 59 , 73-100.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Côté, S. (2005). A social interaction model of the effects of emotion regulation on work strain. Academy of Management Review , 30 (3), 590-530.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Côté, S., Gyurak, A., & Levenson, R. (2010). The ability to regulate emotion is associated with greater well-being, income, and socioeconomic status. Emotion , 10 (6), 923-933.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

DiBlasi, Z., Harkness, E., Ernst, E., Georgiou, A., & Kleijnen, J. (2001). Influence of context effects on health outcomes: A systematic review. The Lancet , 357 , 757–762.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Dunn, P., Arnetz, B., Christensen, J., & Homer, L. (2007). Meeting the imperative to improve physician well-being: Assessment of an innovative program. Journal of General Internal Medicine , 22 (11), 1554-1562.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Erickson, R., & Grove, W. (2007). Why emotions matter: Age, agitation, and burnout among registered nurses. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing , 13 (1).

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Farrel, A., Souchon, A., & Durden, G. (2001). Service encounter conceptualisation: Service providers' service behaviours and patients' service quality perceptions. Journal of Marketing Management, 17 , 577–593.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Fiscella, K., Meldrum, S., Franks, P., Shields, C.G., Duberstein, P., McDaniel, S.H., & Epstein, R.M. (2004). “Patient trust: Is it related to patient-centered behavior of primary care physicians?” Medical Care Journal, 42 (11), 1049-1055.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Fotiadis, A., & Vassiliadis, C. (2013). The effects of a transfer to new premises on patients’ perceptions of service quality in a general hospital in Greece. Total Quality Management , 24 (9), 1022-1034.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Fox, S., & Chesla, C. (2008). Living with chronic illness: A phenomenological study of the health effects of the patient-provider relationship. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners , 20 (3), 109-117.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Godkin, J., & Godkin, L. (2004). Caring behaviors among nurses: Fostering a conversation of Gestures. Health Care Management Review , 29 (3), 258–267.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Goff, B., Boles, J., Bellenger, D., & Stojack, C. (1997). The influence of salesperson selling behaviors on customer satisfaction with products. Journal of Retailing , 73 (2), 171–83.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Gopalan, N., Culbertson, S., & Leiva, P. (2013). Explaining emotional labor?s relationships with emotional exhaustion and life satisfaction: Moderating role of perceived autonomy. Universitas Psychologica , 12 (2), 347-356.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Gosserand, R., & Diefendorff, J. (2005). Emotional display rules and emotional labor: The moderating role of commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology , 90 (6), 1256-1264.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Grandey, A. (2000). Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 1 , 95–110.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Grandey, A. (2003). When the show must go on: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal , 1 , 86-96.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Grandey, A., Kern, J., & Frone, M. (2007). Verbal abuse from outsiders versus insiders: Comparing frequency, impact on emotional exhaustion, and the role of emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 12 (1), 63–79.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Gross, J. (1998). Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 74 , 224-237.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Gross, J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology , 39 , 281-291.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Groth, M., Hennig-Thurau, T., & Walsh, G. (2009). Customer reactions to emotional labor: The roles of employee acting strategies and customer detection accuracy. Academy of Management Journal , 52 (5), 958-974.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Guest, G. (2012). Applied thematic analysis . California: US, Sage Publications.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Guest, G., MacQueen, K., & Namey, E. (2011). Applied thematic analysis . California: US, Sage Publications.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Gursoy, D., Boylu, Y., & Avci, U. (2011). Identifying the complex relationships among emotional labor and its correlates. International Journal of Hospitality Management , 30 , 783-794.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Haezen-Klemens, I., & Lapinska, E. (1984). Doctor-patient interaction, patients’ health behavior, and effects of treatment. Social Science & Medicine , 19 (1), 9-18.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Halpern, J. (2001). From detached concern to empathy: Humanizing medical practice . Oxford University Press, New York.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Hayward, R., & Tuckey, M. (2011). Emotions in uniform: How nurses regulate emotion at work via emotional boundaries. Human Relations , 64 (11), 1591-1523.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Henderson, A. (2001). Emotional labour and nursing: An under-appreciated aspect of caring work. Nursing Enquiry , 8 (2), 130-138.

Crossref,Google Scholar, Indexed at

Hochschild, A. (1983). The managed heart: Comercialization of human feeling . Berkeley: US, University of California Press.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Hojat, M., Lous, D., & Markham, F. (2011). Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Academic Medicine , 86 (3), 359-364.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Hunter, B., & Smith, P. (2007). Emotional labour: Just another buzz word?International Journal of Nursing Studies , 44 (6), 859–861.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Hwa, M. (2012). Emotional labor and emotional exhaustion: Does co-worker support matter?Journal of Management Research , 12 (3), 115-127.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Jimenez, B., Herrer, M., Carvajal, R., & Vergel, A. (2012). A study of physicians' intention to quit: The role of burnout, commitment and difficult doctor-patient interactions. Psicothema , 24(2), 263-270.

Jung, H., & Yoon, H. (2014). Antecedents and consequences of service providers’ job stress in a foodservice industry: Focused on emotional labor and turnover intent. International Journal of Hospitality Management , 38 , 84-88.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Karimi, L., Leggat, S., Donohue, L., Farrel, G., & Couper, G. (2013). Emotional rescue: The role of emotional intelligence an emotional labor on well-being and job stress among community nurses.Journal of Advanced Nursing , 70 (1), 176-186.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Kelley, J.M., Kraft-Todd, G., Schapira, L., Kossowsky, J., & Riess, H. (2014). The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Timmer A, ed. PLoS ONE, 9 (4).

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Kerfoot, K. (1996). The emotional side of leadership: The nurse managers’ challenge. Nursing Economics , 14 (1), 59–62.

Kim, H. (2008). Hotel service providers? emotional labour: The antecedents and effects of burnout”. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27 , 151-161.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Larson, E., & Yao, X. (2005). Clinical empathy as emotional labor in the patient-physician relationship. Journal of American Medical Association , 293 (9), 1100-1106.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Lin, J., & Lin, C. (2011). What makes service providers and patients smile. Antecedents and consequences of the service providers? affective delivery in the service encounter. Journal of the Service Management , 22 (2), 183–201.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Lopes, P., Salovey, P., Côté, S., & Beers, M. (2005). Emotion regulation abilities and the quality of social interaction. Emotions , 5 (1), 113-118.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Mackintosh, C. (2000). Is there a place for care within nursing?International Journal of Nursing Studies , 37 , 321-327.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Mann, S. (2005). A health-care model of emotional labour: An evaluation of the literature and development of a model. Journal of Health Organization and Management , 19 (4/5), 304 317.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Mann, S., & Cowburn, J. (2005). Emotional labour and stress within mental health nursing. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 12 , 154–162.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Mayer, J., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D.J. Sluyter (Eds.). Emotional development and emotional intelligence , 3-31. New York: US, Basic Books.

McMurray, J., Williams, E., Schwartz, M.D., Douglas, J., Van Kirk, J., Konrad, T.R., … & Linzer, M. (1997). Physician job satisfaction: Developing a model using qualitative data. Journal of General Internal Medicine , 12 (11), 711-714.

McQueen, A. (2000). Nurse-patient relationships and partnership in hospital care. Journal of Clinical Nursing , 9 , 723-731.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

McQueen, A. (2004). Emotional intelligence in nursing work. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 47 (1), 101-108.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Naz, S., & Gul, S. (2011). Relationship between emotional labour and emotional exhaustion among medical professionals. International Journal of Academic Research , 3 (6), 472-475.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Oliver, R. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer . McGraw-Hill, London.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Ong, L., de Haes, J., Hoos, A.M., & Lammes, F.B. (1995). Doctor-patient communication: A review of the literature. Social Science & Medicine , 40 , 903–918.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Phillips, S. (1996). Labouring the emotions: Expanding the remit of nursing work?Journal of Advanced Nursing , 24 (1), 139–43.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Pugh, S. (2001). Service with a smile: Emotional contagion in the service encounter. Academy of Management Journal , 44 (12), 1018-1027.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Rafaeli, A., & Sutton, R. (1987). Expression of emotion as part of the work role. Academy of Management Review , 12 (1), 23-37.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Rafaeli, A., & Sutton, R. (1990). Busy stores and demanding patients: How do they affect the display of positive emotion?Academy of Management Journal , 33 (3), 623–637.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Rego, A., Godinho, L., McQueen, A., & Cunha, M. (2010). Emotional intelligence and caring behaviour in nursing. Service Industries Journal , 30 (9), 1419–1437.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Rey, L., & Extremera, N. (2014). Positive psychological characteristics and interpersonal forgiveness: Identifying the unique contribution of emotional intelligence abilities, Big Five traits, gratitude, and optimism. Personality and Individual Differences , 68 , 199–204.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Roter, D., Hall, J., Kern, D., Barker, L., Cole, K., & Roca, R. (1995). Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress: A randomized clinical trial. Archives of Internal Medicine , 155 , 1877-1884.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Saldana, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers . California: US, Sage Publications.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Shanafelt, T. (2009). Enhancing meaning in work: A prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. JAMA, 302 (12), 1338-1340.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Shanafelt, T., West, C., & Sloan, J. (2009). Career fit and burnout among academic faculty. Archives of Internal Medicine , 169 (10), 990-995.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Shani, A., Uriely, N., Reichel, A., & Ginsburg (2014). Emotional labour in the hospitality industry: The influence of contextual factors. International Journal of Hospitality Management , 37 , 150-158.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Smith, P. (1992). The emotional labour of nursing . How nurses care. Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Sutton, R., & Rafaeli, A. (1988). Untangling the relationship between displayed emotions and organizational sales: The case of convenience stores. Academy of Management Journal , 31 (3), 461–487.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Thorne, S., Hislop, T., Armstrong, E., & Oglov, V. (2008). Cancer care communication: The power to harm and the power to heal?Patient Education and Counseling, 71 (1), 34-40.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Wanzer, M.B., Booth-Butterfield, M., & Gruber, K. (2004). Perceptions of health care providers’ communication: Relationships between patient-centered communication and satisfaction. Health Care Communication , 16 (3), 363-384.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Williams, S. (1997). Quality and care: Patients’ perceptions. Journal of Nursing Care Quality , 12 (6), 18-25.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Wong, A., & Sohal, A. (2003). . Journal of Services Marketing , 17 (5), 495–513.

Yagil, D., & Medler-Liraz, H. (2013). Moments of truth: Examining transient authenticity and identity in service encounters. Academy of Management Journal , 56 (2), 473–497.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Zander, M., & Hutton, A. (2009). Paediatric oncology nursing: Working and coping when kids have cancer – a thematic review. Neonatal, Paediatric and Child Health Nursing , 12 (3), 15–27.

Zapf, D. (2002). Emotion work and psychological well-being: A review of the literature and some conceptual considerations. Human Resource Management Review , 12 , 237-268.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Zapf, D., & Holz, M. (2006). On the positive and negative effects of emotion work in organizations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology , 15 (1), 1–28.

Crossref, Google Scholar, Indexed at

Zemke, R., & Bell, C.R. (1990). Service recovery. Training , 27 (6), 42-48.

Received: 28- Dec -2021, Manuscript No. JMIDS-22-10777; Editor assigned: 01- Jan -2021, PreQC No. JMIDS-22-10777 (PQ); Reviewed: 13- Jan -2021, QC No. JMIDS-22-10777; Revised: 18- Jan -2021, Manuscript No. JMIDS-22-10777 (R); Published: 27-Jan-2022