Research Article: 2019 Vol: 22 Issue: 2

Ego Development and Innovation Orientation of Women Entrepreneurs in Germany and Ireland

Käthe Schneider, Friedrich-Schiller-University, Jena

Juliane Möhring, Friedrich-Schiller-University, Jena

Uliana Proskunina, Friedrich-Schiller-University, Jena

Abstract

The entrepreneurial performance and success have been broadly studied in terms of Adult Education and Psychology. The concept of Ego Development has been often employed for the examination of these phenomena. At the same time, further research is needed in regard to women entrepreneurs in particular and national economic contexts. The complexity of the examined theoretical constructs does not allow for straightforward predictions in this direction. The current paper contributes to the outlined field with the examination of innovation orientation with reference to ego development of female business owners in Germany and Ireland. Using a sample for the target population in these two countries, we apply descriptive statistics, Chi- Square and Correlation analysis to examine multiple statistical relations between the target variables. Among others, we deliver the following key findings. The majority of the studied women entrepreneurs show the advanced levels of Ego Development, reaching its E5 (Self-Awareness) and E6 (Consciousness) stages. We also discover the national differences with this respect, showing higher development level for Irish participants than for German ones, also exceeding the managers’ level in the prominent literature to the topic. Similarly, the operationalization of innovation orientation through entrepreneurial orientation related to new ways of acting and solutions, as well as in the encouragement of other persons, is more strongly marked in Ireland than in Germany. In both countries, the support for this orientation is positively associated with the higher levels of Ego Development, namely Self-Awareness and Consciousness. The national differences are also reflected in the placement of the German sample on E5 (Self Awareness) level and the Irish one on E6 (Consciousness) stage. Additionally, we find the weak statistically significant correlation between the dimension and indicator of the discussed phenomenon in both countries. Nevertheless, when applying a comparative country-specific perspective, the conclusion upon the dimension and both indicators remains valid for Germany only. We have addressed the number of limitations and precautions when extrapolating the findings for the similar populations. The related socio-economic studies have been presented for the interpretation and application of the discovered psychological patterns.

Keywords

Ego Development, Entrepreneurial Orientation, Innovation.

Introduction And Problem Statement

In recent decades, a major research focus in Educational and Psychological Research and Entrepreneurial and Leadership Studies has been on helping entrepreneurs improve their performance and entrepreneurial success (Makhbul & Hasun, 2011; McLaughlin, 2012; Bonet et al., 2011). This is critical to furthering innovation, job creation and economic growth, because new companies, especially small and medium sized enterprises, create most new jobs. The EU Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan, for example, recognizes entrepreneurship and self-employment as key factors in economic growth. According to the OECD-EUROSTAT Entrepreneurship Indicators Programme (EIP), entrepreneurs are “persons (business owners) who seek to generate value, through the creation or expansion of economic activity, by identifying and exploiting new products, processes or markets” (Ahmad & Hoffman, 2007), Identifying and exploiting new products, processes or markets, requires an innovation orientation.

In line with these requirements, the main objective of this study is to provide insight into how fundamental competences interact with innovation orientation, using the case of women entrepreneurs from the service sector in Germany and Ireland. Innovation orientation, understood

as a characteristic adaptation following McAdams and Pals’ personality model (McAdams & Pals, 2006), is an underlying characteristic of entrepreneurial competences of women entrepreneurs from the service sector in Germany and Ireland (Schneider, 2017).

While previous models of entrepreneurial competence focused more on observable skills and behaviors, we are seeking to establish a new perspective by addressing ego development. We hypothesize that ego development interacts with entrepreneurial innovativeness behavior.

Achieving an understanding of basic competences is needed and will be invaluable to solve a wide range of problems, e.g., in unlocking women’s entrepreneurial potential, in deconstructing gendered entrepreneurial competences, and in increasing the perceived entrepreneurial competences of women.

Literature Review And Theory

There has been research using the ego development approach for over fifty years (Loevinger, 1966:1976). In the sixties of the twentieth century, American developmental psychologist Jane Loevinger introduced the concept of ego development in the course of her re-search after finding a pattern for the ego’s progressive development (Loevinger, 1966:1976). This research program on ego development has become strongly differentiated in recent decades. Among other things, research interest in ego development is increasingly important for leaders and managers (Cook-Greuter, 1999; Torbert, 2004). In the research field there are, however, almost no studies of entrepreneurs’ ego development.

Because there are overlaps in tasks between managers and entrepreneurs, below reference will also be made to studies of managerial and executive ego transformation in examining the ego development of entrepreneurs: Following a definition of “entrepreneurship” according to Eckhardt & Shane (2003), “entrepreneurship” is an attribute of managers and founders (Eckhardt & Shane, 2003), and thus research on managers is definitely relevant to studies of entrepreneurs, and the findings can surely also overlap.

The theoretical foundations for the description and explanation of ego development is provided by “constructive developmental theory” (Hunter et al., 2011), which has mentalities as its subject. Mentalities include content, processes and structures of thought (Kegan, 2000). A central theory which can be assigned to the “constructive developmental” theory group is Piaget’s cognitive development theory, the foundation stone for constructivist developmental theories in this area. These include among others Loevinger’s ego-development (Loevinger, 1976), Kegan’s subject-object model (Kegan, 1994:2000), and Beck and Cowan’s spiral dynamics (Beck & Cowan, 1996).

According to constructivist developmental theories, there are two different types of development, horizontal and vertical (Cook-Greuter, 2004). Horizontal development refers to the content of mentalities and describes development as an expansion and deepening of knowledge (Liska, 2013). Vertical development, to the contrary, relates to changes in the form or structure (trans-formation) of our mentalities and describes a development toward increasing complexity (Kegan, 2000; Liska, 2013). The vertical transformation manifests itself in a different way to learn, to see the world through the eyes of others and to interpret experiences and views of reality (Hunter et al., 2011). Development is understood as growth through a change in “meaning making”.

People make meaning within a specific frame. This frame is also called the ego or respectively the self (Liska, 2013). The “ego” “… provides the frame of reference that structures one’s world and within which one perceives the world …” (Loevinger, 1976). With the aid of this frame, people develop structures of thought that they use to understand the world, others and themselves. Following Loevinger (1976), the “ego” involves a person’s processes of making meaning by subjectively imposing a frame of reference on experience. From the patterns of thought arise “action logics” (Liska, 2013). These “action logics” contain our interpretation of reality, they thereby describe the developmental steps of meaning-making, contain one’s own meaning and dominant life concerns, as well as emotions and experiences (Cook-Greuter, 1999; Torbert, 2004).

A person passes through the self’s developmental stages starting from below, whereby very few people actually ever reach the highest stages. When one develops vertically, one climbs steps; when one develops horizontally, however, one expands one’s knowledge within the stage where one currently finds oneself. The highest ego stage one has achieved is one’s “center of gravity,” because a person tends to use it to react. Exceptions are stress situations, where one tends to draw on behavioral patterns and ways of thinking of earlier developmental stages (Liska, 2013). Following Hy & Loevinger (1996), every person displays behavior of more than one level.

Overall, Loevinger’s developmental model envisages nine stages of development. On each stage, the ego thereby reintegrates the tasks of impulse control, interpersonal interaction, current concerns and cognitive style in a characteristic manner (Loevinger, 1976). These stages are represented in Table 1.

| Table 1: Stages Of Ego-Development(Adaptation From Loevinger, 1976:1998) | ||||

| Stage | Character | Cognitive Style | Interpersonal Style | Conscious Preoccupations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1: Symbiotic | - | - | Symbiotic | Self- vs. non-self |

| E2: Impulsive | Impulsive | Stereotyping Conceptual confusion | Egocentric, dependent | Bodily feelings |

| E3: Self-protective | Opportunistic | Stereotyping Conceptual confusion | Manipulative way | Trouble control |

| E4: Conformist | Respect for rules | Conceptual simplicity | Cooperative loyal | Appearances behavior |

| E5: Self-aware | Exceptions allowable | Multiplicity | Helpful Self-aware | Feelings problems adjustment |

| E6: Conscientious | Self-evaluated standards, self-critical | Formal operations | Intense responsible | Motives traits achievements |

| E7: Individualist | Tolerant | Relativism | Mutual | Individuality development roles |

| E8: Autonomous | Coping with conflict | Increased conceptual complexity, complex patterns, toleration for ambiguity, broad scope, objectivity | Interdependent | Self-fulfillment |

| E9: Integrated | Reconciling inner conflicts, renunciation of unattainable | increased conceptual complexity, complex patterns, toleration for ambiguity, broad scope, objectivity | Cherishing individuality | Identity |

Stages 1 to 3 can be summarized in the pre-conformist level, stages 4 to 5 in the conformist, and stages 6 to 9 in the post-conformist levels (Kapfhammer et al., 1993; Novy, 1993): On the pre-conformist stage people orient themselves primarily to their own needs and interests. The recognition of social rules and adaptation forms the core of the conformist stage. Persons on the post-conformist stages (Stages 7 to 9) are in the position, on the basis of self-set values and the ability to deal with inner conflicts, to flexibly adapt themselves to circumstances.

Starting from a theoretical description of these fundamental structures and processes of ego development, below we draw on studies of ego development in entrepreneurs, along with managers and executives related to the relative frequencies of development stages.

In a literature review, Liska brings together the percentual occurrence of specific developmental stages in adults compared to managers (Liska, 2013). He thereby compared the values (Cook-Greuter, 2004) found in a normal sample of adults (n=4.510 adults) with ones Rooke & Torbert (2005) found among managers (n=497 managers) (Cook-Greuter, 2004; Rooke & Torbert, 2005), based on the series of stages of ego development in the approaches of Loevinger (1996) and Torbert (2004). At least descriptively, the percentual shares between the two social categories are similar: 36.5% of adults and 38% of managers are on the Self-Aware Level (E5), and 29.7% of adults and 30% of managers operate on the Conscientious Level (E6) (Cook-Greuter, 2004; Rooke & Torbert, 2005). The majority of adults or respectively managers in these samples can be classified on Levels E5 and E6. The differences can be explained by the diversity of the samples and the figures can serve as an orientation point. Not only the above-named Rooke and Torbert study, but also a 1999 study by Cook-Greuter showed a similar distribution of ego development of executives: ca. 5% of executives are on first three lower stages; 80% on the three middle stages, and 15% on the three highest developmental stages (Cook-Greuter, 1999; Rooke & Torbert, 2005).

As early as 1999, Teal and Carroll made a study (Teal & Carroll, 1999) of frequencies for adult ego development of entrepreneurs in comparison with the average population. They chose “moral development” as a dependent variable, understood as a synthesis of “moral development” in Kohlberg’s sense (Kohlberg, 1969) and “ego development” according to Loevinger (Loevinger, 1976). Their finding was that middle values of entrepreneurs’ “moral-development” levels were slightly higher than those of the general adult population. In addition, the distribution of persons across the various levels shifted among entrepreneurs to a higher “moral development” level than the average population. Furthermore, their comparison between entrepreneurs and “middle-level managers” also showed that entrepreneurs have a higher average “moral level.” In one of the rare studies related to entrepreneurs, a 1992 study by King and Roberts showed that “policy entrepreneurs,” thus a specific group of entrepreneurs, have a higher ego level and better integrated personality than the average population (King & Roberts, 1992). Based on earlier studies it can be assumed that “executive entrepreneurs” do not have as high an ego level as “policy entrepreneurs” (Lewis et al., 1980; Ramamurti, 1986). Thereby high levels of ego development are characterized by tolerance, as well as collective exercise of power, etc. Low ego development stages are revealed by competitive, impulsive aggressive exercise of power.

Starting from percentual results shown here for specific developmental stages of managers, executives and entrepreneurs, research findings on the association of ego development and entrepreneurial performance are presented below.

In terms of behavior and decision of managers, Smith found already in 1980 that the developmental stages of managers are related to their decision- making style and the way they exercise power (Smith, 1980): Managers on lower developmental stages tend to force compliance, allow subordinates less decision-making freedom and generally assert their power through pressure and strict rules. Managers on higher stages, to the contrary, make decisions based on their own convictions and influence others with rewards and expertise. An early publication by Fisher et al. (1987) showed that higher ego levels are related to better leadership, management and organizational abilities. Persons on a lower ego level have a cognitively simple world view, often follow stereotypes, and are less empathetic and tolerant. In decision-making processes they usually proceed step-by-step, and their decision style is more classical rational. They display a heroic leadership style, and their “organizational mode” is lower level, less complex and stable. Executives on higher ego stages possess a cognitively complex, as well as abstract world view, are more empathetic, understanding and tolerant than persons with lower ego development levels. In decision situations they tend to employ neo-classical rather than dialectical approaches. Managers on higher ego stages mainly make decisions using a transformational management style, and their “organizational mode” is higher level, more complex and more change directed.

In 1993, Weathersby additionally found that managers on lower stages tended to rely more on external authorities, and managers on higher stages would rely more on their own internal authority (Weathersby, 1993). Furthermore, in earlier studies it was already shown that a higher developmental stage is needed for a leader to realize transformative organizational change. This is already possible starting on an ego-level of E6 (“individual”), but, however, it is especially possible starting at level E8 (“inter-individual”) (Argyris & Schon, 1978; Rooke & Torbert, 1998; Weathersby, 1993).

From the perspective of the perception of others, a more recent study by McCauley et al. (2006) shows that executives on higher stages of vertical development are also evaluated by other employees as more competent and efficient than executives on lower ego levels (Baron & Cayer, 2011; Barker & Torbert, 2011; Cook-Greuter, 2004; Joiner & Josephs, 2006; Mat-tare, 2008; Rooke & Torbert, 2005). This study emphasizes, as did previous ones, that the ego and its development in stages across the life course are independent of intelligence (Cohn & Westenberg, 2004; McCauley et al., 2006; Newman et al., 1998). According to Hunter et al. (2011), competent executives are consistently described by others as aware of their own perceptions and their own “action logic.” The study rates imply that executives’ consciousness of their own “action logic” and their level of vertical development as executives are useful for improving their leadership qualities. James et al. (2017) did a study of executives in the educational sector. First, they found that leaders on different ego stages were also perceived and evaluated differently by other persons. Those on higher ego levels were more positively assessed by others. In addition, it was found that adults in the same leadership positions behave differently when they are on different states of ego development. This is because due to different “meaning-making systems” they evaluate organizational phenomena differently (James et al., 2017).

With regard to entrepreneurs, King (2011) published a study of “policy entrepreneurs,” inspired by literature that often claims “entrepreneurship” leads to a lower sense of responsibility, abuse of power and ethically questionable behavior. For this reason, King observed the behavior and strategies of entrepreneurs in the process of innovation and created a psychological profile, and among other things he measured subjects’ ego levels. Thereby the ego-development level of 2 out of 3 persons was estimated to be on the “individualistic” stage according to Loevinger and 1 of 3 on the “autonomous” stage. Then he compared “policy entrepreneurs” (1) with “executive entrepreneurs” (2), whereby he found extensive differences. The former display power above all through hard work and influence, whereas the latter do this with money and pressure. One cause of this phenomenon is assumed to be that differences can be explained by various ego levels.

Schneider & Albornoz (2018) analyzed from a theoretical perspective the ego development of entrepreneurs. They explained that entrepreneurial success depends on various personal related factors. Regarding competences, in previous research, reference was made mainly to context specific competences and less to general competences. Since there is a connection between the self and entrepreneurial behavior, Schneider & Albornoz found that ego development goes together with the development of an entrepreneur’s key competences. Thus, the entrepreneur’s ego interacts with the key competences to discover, create and use opportunities and differs depending on whether entrepreneurs discover or create possibilities. For these key competences specific levels of ego development are essential. The conformist stage, with a minimum level of E4, is a typical stage for entrepreneurs recognizing and exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities.

The post conformist stage, with a minimum level of E6, seems to be a more typical level for entrepreneurs creating new business opportunities (Schneider & Albornoz, 2018). Thereby “to discover” is a source of possibilities for imitators, and “to create” leads to opportunities for innovators. According to these difference key competences Schneider and Albornoz distinguish two sorts of entrepreneurs: Imitators and Innovators. Imitators seldom work with innovative products, processes and services. Their entrepreneurial identity results above all from social construction. Innovators to the contrary primarily develop their identity intrinsically. These entrepreneurs strive for self-actualization and are found on at least stage E6 (“conscientious stage”). In summary, entrepreneurs who create possibilities may have higher levels of ego development than those who recognize opportunities.

Based on a previous study conducted with the same sample as the present one, 306 women entrepreneurs (200 women entrepreneurs from Germany and 106 women entrepreneurs from Ireland), this analysis finds that entrepreneurial competence, as a higher order latent construct, has a major impact on entrepreneurial performance. Entrepreneurial competences of women entrepreneurs in Germany and Ireland can be operationalized by a set of six first-order factors, including functional task-related managerial skills, entrepreneurial characteristic adaptations of self-efficacy and orientations of competition, risk-taking and innovation, and the founder and innovator identity. The theoretical construct of entrepreneurial performance, which consists of the dimensions of economic, individual and societal performance, is expanded with the dimensions of performance quality, customer satisfaction and productivity (Schneider, 2017). This study included analysis of the impact of the orientation of innovation on entrepreneurial competences that explain self-reported entrepreneurial success. Entrepreneurial orientation is a higher-order latent construct consisting of four first-order factors measured by eleven items (Wang, 2008). The dimensions are market Pro-activeness (PR) (e.g. ‘In the past three years, my organization has marketed a large variety of new lines of products or services’), Risk-taking (RK) (e.g. ‘In general, my organization has a strong propensity for high risk projects (with chances of very high returns’); competitive Aggressiveness (AG) (e.g. ‘In dealing with competitors, my organization often leads the competition, initiating moves to which our competitors have to respond’), and firm Innovativeness (IN) (e.g. ‘Management actively responds to the adoption of “new ways of doing things” by main competitors’) (Wang, 2008). Items are measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Scores are obtained for each dimension. All dimensions demonstrated high reliability (Wang, 2008). The measurement model resulted in a good fit: χ2=79.771, df=40, p=0.000, χ2/df=1.994, GFI=0.938, CFI=0.960 (Wang, 2008). The first-order loadings ranged from 0.52 to 0.93 (t>1.96, p<0.001), the second order loadings from 0.60 to 0.99 (t>1.96, p<0.001) (Wang, 2008). Schneider showed for the same sample of this study, namely women entrepreneurs from the service sectors in Germany and Ireland, that entrepreneurial orientation is no longer a higher-order latent construct. Rather, in the model three first-order factors, orientation of competition, orientation of risk-taking, and orientation of innovation, exert direct influence on entrepreneurial competences (Schneider, 2017). For the entrepreneurial orientation of innovativeness, the impact on the latent construct of entrepreneurial competence is strong (=0.510; p<0.001) (Schneider, 2017). Table 2 shows that the manifest variables that highly load on the latent construct of innovativeness which are no longer there are the following two:

| Table 2: Factor Loading (Λ), Standard Error (Se) And Two-Tailed Level (P) Of Manifest Variables On The Latent Construct Entrepreneurial Orientation Of Innovativeness | |||

| Manifest Variable | λ | SE | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IN 2 | 0.798 | 0.046 | 0 |

| IN 3 | 0.905 | 0.048 | 0 |

IN 2: “I am willing to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions.”

IN 3: “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways.”

Methodology

Measures

Besides socio-demographic and company related data, which will be explained under the heading of procedure, the following identified measures are relevant for this study.

Entrepreneurial orientation: The construct of entrepreneurial orientation represents a firm’s degree of entrepreneur-ship (Miller, 1983), referring to “processes, practices and decision-making activities that lead to new entry” (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). Because most of the companies in the sample are micro-enterprises with fewer than four employees, it is likely that in most cases the firm is highly represented by the entrepreneur. For this reason, entrepreneurial orientation can be regarded as the extent of applied entrepreneurial processes, practices and decision-making activities by the entrepreneurs.

In our study, the focus lies on the dimension of innovativeness. The items of the innovativeness dimension are:

“I am willing to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions.” “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways.”

These variables load on the latent construct of innovativeness that explains the entrepreneurial competences of women entrepreneurs from the service sector in Germany and Ireland (Table 2).

Ego development: The individual’s ego developmental stages can be studied with the aid of sentence stems dealing with impulse control, interpersonal interaction, current concerns and cognitive style. For measurement we used the validated short version “Washington University Sentence Completion Test of Ego Development,” WUSCT Form A) with 18 sentence stems (Hy & Loevinger, 1996). This test is a method for converting qualitative data into psychometrically sound quantitative data.

Because the short version “Washington University Sentence Completion Test of Ego Development”, WUSCT Form A was only available in English, a German test version was developed. The English sentence stems were translated into German. These translations were com-pared with those of the research team, and the differences were discussed. Based on this discussion, a final German questionnaire was prepared. This translation was then checked by means of retranslation back into English. Overall the retranslation showed that this corresponded very well with the original.

The evaluation was undertaken by trained experts. First, each statement was evaluated in regard to the developmental stage. The 18 individual values were combined into a total value. Thereby all the individual values were weighted with the respective developmental stage to determine a total value. The frequency distribution was evaluated with the aid of distribution rules (Ogive rules). Here the distribution of the answers across the total spectrum of ego development is taken into consideration. For each stage cumulative limit values are pre-specified, because only a specific number of ratings can be placed on a particular stage. In the last step, the total developmental stage is determined by the developmental value, which is to be regarded as ordinally scaled.

The sentence objects were evaluated with the aid of Hy & Loevinger’s evaluation manual (1996). Various pairs of trained researchers coded the responses for a package of 30 questionnaires. The interrater reliability coefficient for various pairs of rates was between a k of 0.80 and 0.90. Thus, the resulting assessment of the developmental stages can be seen as reliable.

Procedure

Data for the study were gathered using a structured web-questionnaire. Completion of the questionnaire required about 25 minutes. A convenience sampling technique was used to construct the sample in Germany and Ireland because it was hard to achieve a reasonable sample size. Participants were recruited by contacts with women entrepreneur associations, through social media, Internet sites, emails, and posts in relevant social forums. The data analysis was performed using the SPSS software.

The questionnaire consists of three parts: The first part includes a comprehensive person-al and organizational background questionnaire (e.g. age, years of business experience, qualifications, motivation, commercial/industrial branch, number of employees). These are socio-demographic and company related data relevant for the present study. The second part covers functional managerial skills, questions related to entrepreneurial identity, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, entrepreneurial orientation, and entrepreneurial performance. Most questions were closed-ended and were designed using a Likert scale. The last part of the questionnaire was the sentence completion test.

Results

Characteristics of the Sample

The study population consisted of early and established women entrepreneurs from Ireland and Germany, operationalized as enterprise owners with at least one employee. A total of 306 participants (200 women entrepreneurs from Germany and 106 women entrepreneurs from Ireland) were recruited for this study. A total of 36% of the women entrepreneurs are early stage entrepreneurs, and 64% established women entrepreneurs. The mean age of this group was 44 years, ranging from 23 to 70 years. A total of 8% of participants have a secondary school degree, 39% a Bachelor degree; 45% are college graduates, and 8% have a PhD. The entrepreneurs have no more than 16 employees (average: 5 employees). 297 completed sentence completion tests and questionnaires were received.

Results of the Empirical Research Questions

Analysis of the theoretical foundations and empirical studies presented in the literature review has made it clear that progress in the ego development especially of managers, and executives goes together with relevant competences. Below we examine which developmental stages women entrepreneurs are on in general, and what development level women entrepreneurs with an innovative orientation are on in Germany and Ireland.

Ego-development level of women entrepreneurs in Germany and Ireland: Research question 1: On what levels of development are women entrepreneurs in Germany and Ireland?

H1: Because of the overlaps in challenges between managers and entrepreneurs the distribution of ego development of women entrepreneurs is similar to the distribution of managers found by Rooke & Torbert (2005); Cook-Greuter, (1999).

Table 3 shows that the distribution of developmental steps is broad and tends to normal, as six (E3-E8) of eight possible stages are represented in the total sample. Most women entrepreneurs are as expected on levels E5 of Self-Awareness and E6 of Consciousness. The distribution of ego-development of women entrepreneurs in Germany and Ireland is similar to what Rooke & Torbert (2005) (also Cook-Greuter, 1999) found with managers. This distribution corresponds also to the distribution of the adults in studies by Cook-Greuter (2004).

A further question is whether women entrepreneurs in Germany differ from the women entrepreneurs in Ireland in regard to their ego-development level.

As well without inferential statistical examination, in Table 4 differences in ego-development between Irish and German women entrepreneurs become clear; While for both groups, the distribution of the developmental stages over six stages is broad, most German women entrepreneurs (38.7%) are on a lower stage of development, the stage E5 (Self-Aware), than the Irish women entrepreneurs, the majority of whom (41.2%) are on stage E6 (Conscientious). As well, the women entrepreneurs in Ireland, in comparison to the adults and managers of the studies by Cook-Greuter (1999) and Rooke & Torbert (2005), display higher shares on stages E6 to E8 and lower shares on stages E3 to E5 (Table 5). With reference to combined stages, between the baseline one (Table 3) and the studies by Cook-Greuter (1999) and Rooke &Torbert (2005): In Ireland 23.5% of the surveyed women entrepreneurs have reached the last three developmental stages, while in Germany the level is merely 12.9%. The value in Ireland is compared to the other studies remarkably high.

| Table 3: Ego-Development Values Of Women Entrepreneurs In Germany And Ireland | |||||

| Stage | Frequency | Percentage | Valid Percentage | Cumulative Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | E3: Self-protective | 12 | 3.9 | 4 | 4 |

| E4: Conformist | 41 | 13.4 | 13.8 | 17.8 | |

| E5: Self-aware | 102 | 33.2 | 34.3 | 52.2 | |

| E6: Conscientious | 93 | 30.3 | 31.3 | 83.5 | |

| E7: Individualist | 36 | 11.7 | 12,1 | 95.6 | |

| E8: Autonomous | 13 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 297 | 96.7 | 100.0 | ||

| Missing | System | 10 | 3.3 | - | - |

| Total | 306 | 100.0 | - | - | |

| Table 4: Ego-Development Values Of German And Irish Women Entrepreneurs | |||||

| Business Location | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Ireland | ||||

| E-Level | E3: Self-Protective | Frequency | 10 | 2 | 12 |

| % In business location | 5.10% | 2.00% | 4.00% | ||

| E4: Confomist | frequency | 34 | 7 | 41 | |

| % In business location | 17.40% | 6.90% | 13.80% | ||

| E5: Self-Aware | frequency | 75 | 27 | 102 | |

| % In business location | 38.50% | 26.50% | 34.30% | ||

| E6: Conscientious | Frequency | 51 | 42 | 93 | |

| % In business location | 26.20% | 41.20% | 31.30% | ||

| E7: Individualist | frequency | 20 | 16 | 36 | |

| % In business location | 10.30% | 15.70% | 12.10% | ||

| E8: Autonomous | frequency | 5 | 8 | 13 | |

| % In business location | 2.60% | 7.80% | 4.40% | ||

| Total | frequency | 195 | 102 | 297 | |

| % In business location | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | ||

| Table 5: Ego-Development Values Of German And Irish Entrepreneurs Values For Managers (Rooke & Torbert, 2005) And Adults (Cook-Greuter, 2004) In Comparison | ||||

| Stage | Women Entrepreneurs | Cook-Greuter (2004) | Rooke & Torbert (2005) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Ireland | Adults | Managers | |

| E3: Self-protective | 5.10% | 2.00% | 4.30% | 5% |

| E4: Conformist | 17.40% | 6.90% | 11.30% | 12% |

| E5: Self-aware | 38.50% | 26.50% | 36.50% | 38% |

| E6: Conscientious | 26.20% | 41.20% | 29.70% | 30% |

| E7: Individualist | 10.30% | 15.70% | 11.30% | 10% |

| E8: Autonomous | 2.60% | 7.80% | 4.90% | 4% |

| E9: Integrated | - | - | 2.00% | 1% |

| 195 | 102 | 4.51 | 497 | |

| 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | |

Using the Chi-Square test, the extent was examined to which differences between women entrepreneurs in Germany and Ireland are accidental. The results in Table 6 show that with a p-value of 0.001 a highly statistically significant difference is found between the Irish and the German women entrepreneurs. The additional calculation of the degree of association with Cramér’s V, shows with a value of CI=0.263 a moderate association between country and ego development. Since the number of observations in some cells falls under the expected value of 5, these statistics should only be interpreted as descriptive.

| Table 6: Chi-Square Test With Ego-Development Values Of German And Irish Women Entrepreneurs | |||

| Value | df | p-value Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson-chi-square | 20.609 | 5 | 0.001 |

| Cramer’s-V | 0.263 | - | 0.001 |

| Number of valid cases | 297 | - | - |

Note: 2 cells (16.7%) have the expected number of less than 5. The expected minimum number is 4.12.

The second examination of the extent to which there are significant differences between the women entrepreneurs in Germany and Ireland was carried out with the sum score of the ego development level, which can illustrate the finer nuances in the ego development level. In addition, a test was made to compare average values. The results in Table 7 show a difference in the average values between the ego sum score of both groups: The difference between the sum score of ego development of women entrepreneurs in Ireland and Germany is more than half a standard deviation.

Table 7 documents that the mean values of the sum score of ego-development differ. The t-test for independent groups presupposes variance homogeneity. Whether the variances are homogeneous (“equal”) is tested with the Levene Test for variance homogeneity.

The Levene Test employs the null hypothesis, which does not distinguish between the two variances. Therefore, a non-significant result means that the variances do not differ, and thus there is variance homogeneity. The F-value amounts to 0.253 with the associated significance of p=0.616 (Table 8). Since in the example variance homogeneity is present, the goal “variances are equal” is relevant, thus the upper row is to be considered. Thereby the difference be-tween the mean values of the sum scores of ego development in the two countries is significant. Taking into account the absolute difference between the two presented mean scores of the out-come variable in two countries, we conclude upon the moderate strength of examined statistical relations, as shown in the Table 7.

| Table 7: T-Test With Sum Score Of Ego-Developments Of German And Irish Women Entrepreneurs | |||

| Business Location | Mean Value | H | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | 89.06 | 196 | 9.061 |

| Ireland | 94.69 | 102 | 9.949 |

| Total sum | 90.99 | 298 | 9.732 |

| Table 8: Test For Variance Homogeneity (Levene Test) And T-Test For Independent Samples | ||||||||||

| Levene Test of Variance Equality | T-Test for Mean Value Equality | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Value Difference | Standard Error Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of Difference | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| Total Score | Variance equality assumed | 0.253 | 0.616 | -4.915 | 296 | 0 | -5.625 | 1.144 | -7.877 | -3.373 |

| Variance equality not assumed | - | - | -4.772 | 188.785 | 0 | -5.625 | 1.179 | -7.95 | -3.3 | |

In the following, Eta Correlation is used to determine if a relationship exists between the independent categorical variable of the nation and the dependent metric variable of the sum score. Eta square is the explained variance with one independent variable. The eta coefficient requires that the independent variable is at a nominal-level and the dependent one at an interval-or ratio-level. Here, it makes sense, that the interval-level variable is the sum score, and the nominallevel variable, the nation, is the independent one.

Table 9 shows that about 28% of the variability in the dependent variable can be attributed to the variability of the independent one: If you know the nation, 28% of the variability of the scum score can be explained.

| Table 9: Correlation Between Country And Sum Score Of Ego-Development | |||

| Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal by interval | Eta | Business location: dependent | 0.464 |

| Eta | Sum score: dependent | 0.275 | |

Level of development of women entrepreneurs and firm innovation orientation in Germany and Ireland: Research question 2: What level of development do women entrepreneurs in Germany and Ireland have with regard to innovation orientation?

H2: There is a positive correlation between innovation orientation and ego-development of women en- trepreneurs (Schneider & Albornoz, 2018).

Innovation orientation is operationalized here across two indicators loaded on the factor Innovation Orientation to explain the entrepreneurial competences of the women entrepreneurs in our sample (Table 2): “I am willing to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions” and “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways.” Table 10 and Table 11 shows the distribution of the two partial orientations in the respective countries.

| Table 10: Entrepreneurial Orientation In Germany And Ireland Outcome Variable: “I Am Willing To Try New Ways Of Doing Things And seek unusual, novel solutions” | ||||||||

| Entrepreneurial Orientation: “I am willing to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions” | Total Sum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | ||||

| Business Location | Germany | Frequency | 2 | 3 | 22 | 81 | 92 | 200 |

| % In business location | 1.0% | 1.5% | 11.0% | 40.5% | 46.0% | 100.00% | ||

| Ireland | Frequency | 1 | 1 | 10 | 34 | 60 | 106 | |

| % In business location | 0.9% | 0.9% | 9.4% | 32.1% | 56.6% | 100.00% | ||

| Total Sum | Frequency | 3 | 4 | 32 | 115 | 152 | 306 | |

| % In business location | 1.0% | 1.3% | 10.5% | 37.6% | 49.7% | 100.0% | ||

In Ireland a higher share of women entrepreneurs (88.7%) agree with the Orientation of Innovation “I am willing to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions” than in Germany (86.5%).

Also, on partial orientation “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways” can be shown to have a higher degree of agreement in Ireland (91.5%) in contrast to Germany (85.5%). Since at least one cell has the expected number of cases of less than 5, these two statistics (Tables 10 and 11) should be interpreted as descriptive.

| Table 11: Entrepreneurial Orientation In Germany And Ireland Outcome Variable: “I Encourage People To Think And Behave In Original And Novel Ways” | ||||||||

| Entrepreneurial Orientation: “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways” | Total Sum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | ||||

| Business Location | Germany | Frequency | 2 | 2 | 25 | 84 | 87 | 200 |

| % In business location | 1.0% | 1.0% | 12.5% | 42.0% | 43.5% | 100.0% | ||

| Ireland | Frequency | 1 | 3 | 5 | 35 | 62 | 106 | |

| % in Business location | 0.9% | 2.8% | 4.7% | 33.0% | 58.5% | 100.0% | ||

| Total Sum | Frequency | 3 | 5 | 30 | 119 | 149 | 306 | |

| % in Business location | 1.0% | 1.6% | 9.8% | 38.9% | 48.7% | 100.0% | ||

In the following, Innovation Orientation is related to Ego Development, first for both countries together, then separately by country.

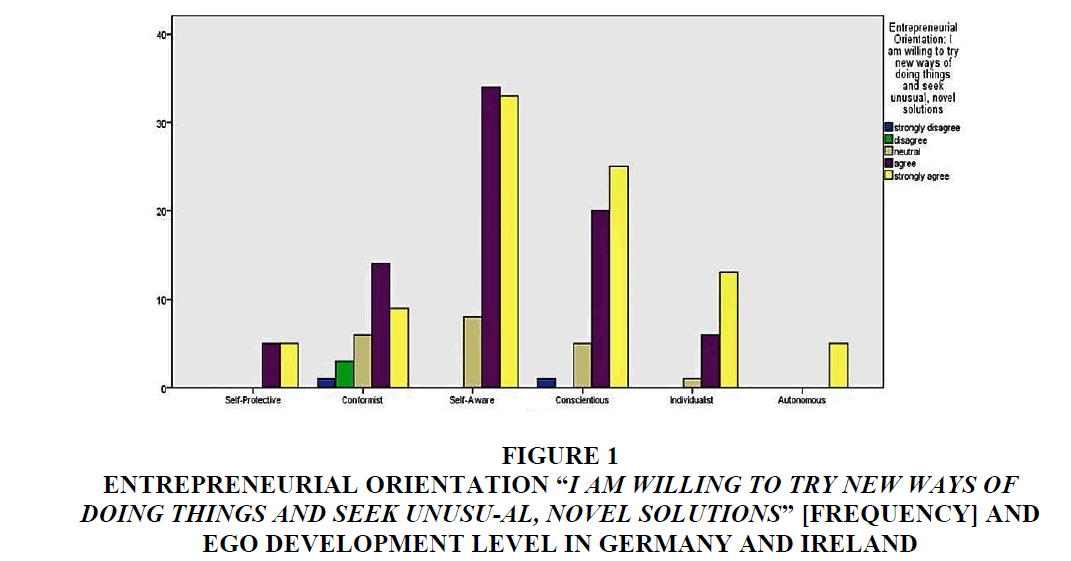

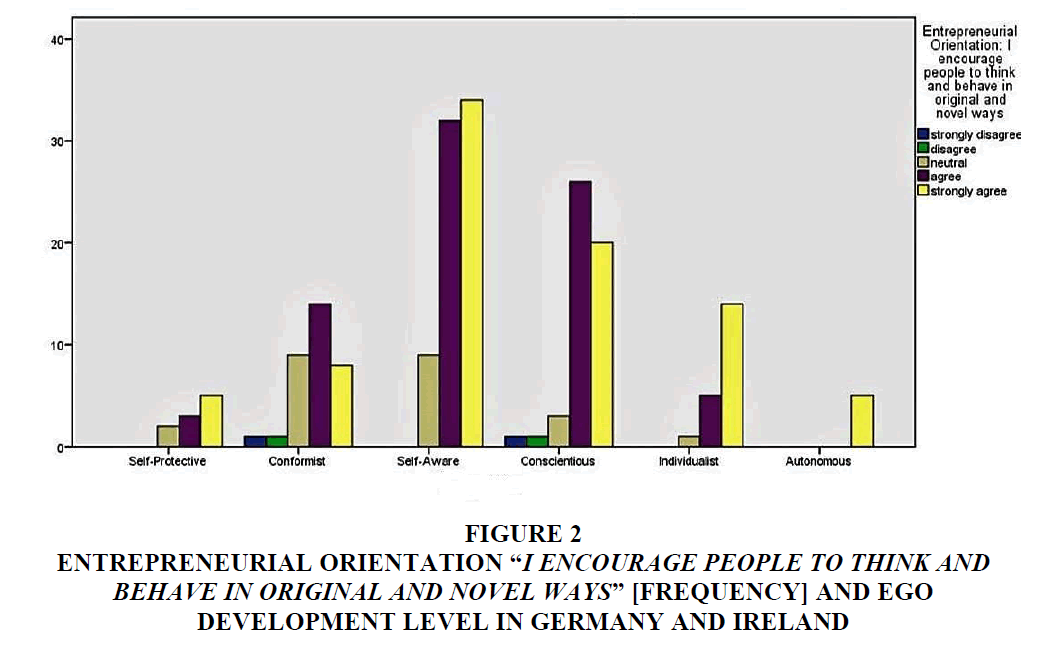

Most women entrepreneurs from Germany and Ireland who give an affirmative answer to the statement: “I am willing to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions” are on the ego level Self-Aware or Conscientious (Table 12 and Figure 1). It also appears that by stronger agreement with the statement, the share of those who are on higher levels, such as Individualist und Autonomous, increases (Table 12 and Figure 1), or respectively negative statements decrease with a higher ego level. Both results also hold for the second statement, “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways” (Table 13 and Figure 2).

Figure 1:Entrepreneurial Orientation “I Am Willing To Try New Ways Of Doing Things And Seek Unusu-Al, Novel Solutions” [Frequency] And Ego Development Level In Germany And Ireland.

Figure 2:Entrepreneurial Orientation “I Encourage People To Think And Behave In Original And Novel Ways” [Frequency] And Ego Development Level In Germany And Ireland.

For the variables “Entrepreneurial Orientation: “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways” and “I am willing to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions” at least one cell has the expected number of cased of less than 5. For this reason, these two statistics (Tables 12 and 13) should be interpreted descriptively.

| Table 12: Entrepreneurial Orientation And Ego Development In Germany And Ireland Outcome Variable: “I Am Willing To Try New Ways Of Doing Things And Seek Unusual, Novel Solutions” | |||||||||

| E-Level | Total Sum | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Protective | Conformist | Self-Aware | Conscientious | Individualist | Autonomous | ||||

| Entrepreneurial Orientation: “I am willing to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions” | Strongly Disagree | Frequency | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| % In e-level | 0.0% | 2.5% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 2.8% | 0.0% | 1.0% | ||

| Disagree | Frequency | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| % In e-level | 0.0% | 7.5% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.4% | ||

| Neutral | Frequency | 0 | 7 | 12 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 29 | |

| % In e-level | 0.0% | 17.5% | 11.8% | 8.6% | 2.8% | 7.7% | 9.8% | ||

| Agree | Frequency | 5 | 15 | 44 | 36 | 11 | 1 | 112 | |

| % In e-level | 41.7% | 37.5% | 43.1% | 38.7% | 30.6% | 7.7% | 37.8% | ||

| Strongly Agree | Frequency | 7 | 14 | 45 | 48 | 23 | 11 | 148 | |

| % In e-level | 58.3% | 35.0% | 44.1% | 51.6% | 63.9% | 84.60% | 50.0% | ||

| Total Sum | Frequency | 12 | 40 | 102 | 93 | 36 | 13 | 296 | |

| % In e-level | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

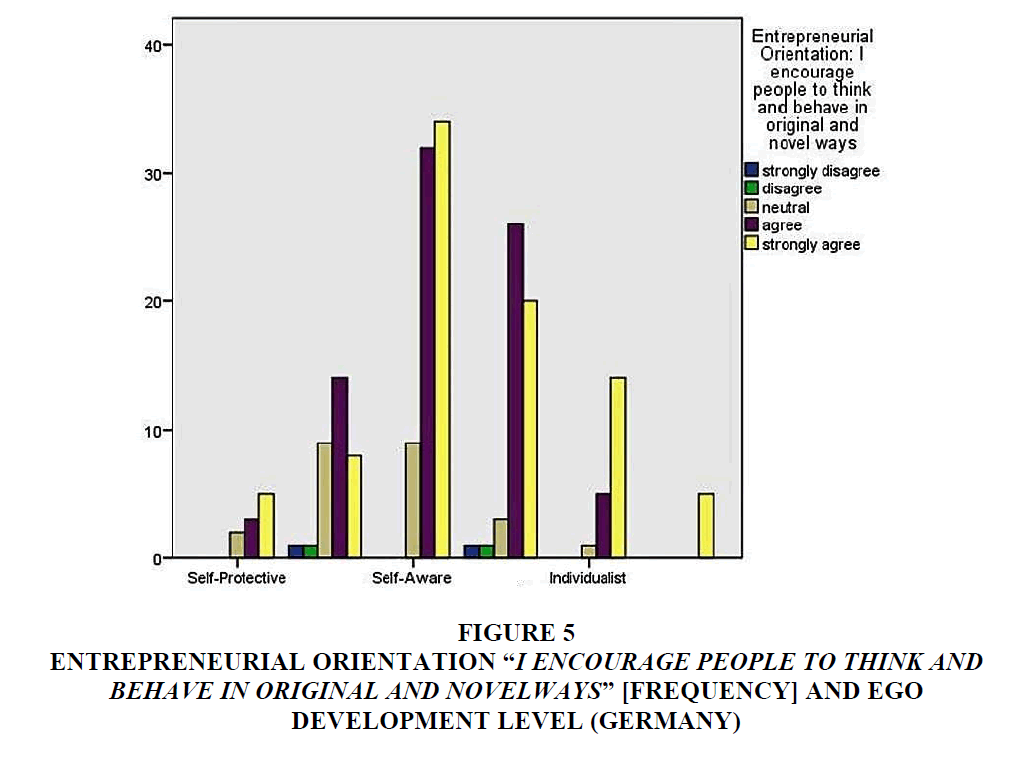

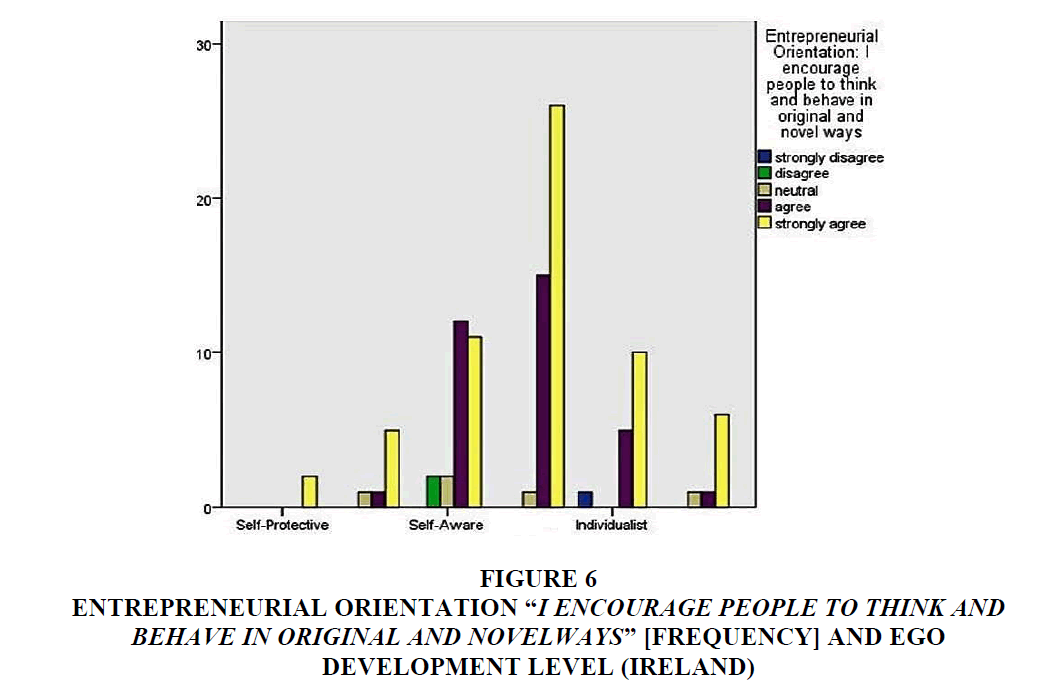

From a country-specific perspective, in the following figures (Figures 3-6) it appears that the distribution of persons across various ego development levels shifted among women entrepreneurs from Ireland to a higher entrepreneurial orientation and ego level than in Germany.

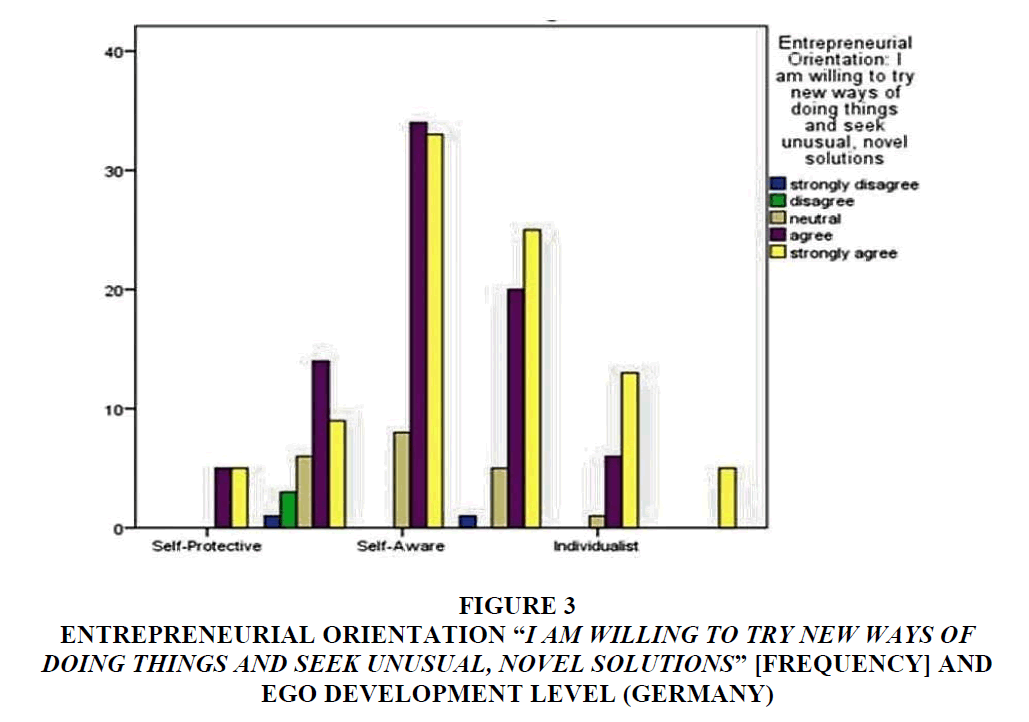

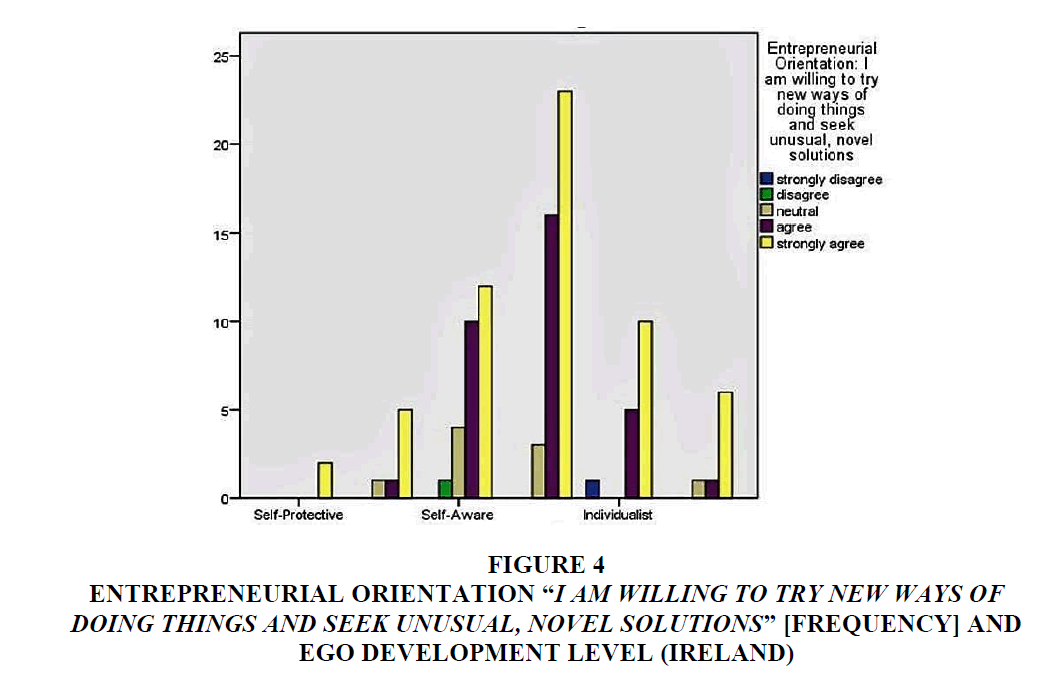

If we compare Germany and Ireland with regard to the Entrepreneurial Orientation “I am willing to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions” and Ego Development Level (Figures 3 and 4) with each other, it becomes clear that in Germany the greatest share of affirmative answers were given by persons on the Self-Aware Level, while in Ireland the highest rate of agreement occurs on the Conscientious Level. Likewise, the share of strong agreement with willingness for innovative ways of acting and solutions is much stronger in comparison to Germany (Table 10). Thus, we find a higher degree of Entrepreneurial Orientation in regard to new ways of acting and solutions (Table 10) associated with a higher E-level in Ireland compared to Germany.

Figure 3:Entrepreneurial Orientation “I Am Willing To Try New Ways Of Doing Things And Seek Unusual, Novel Solutions” [Frequency] And Ego Development Level (Germany)

Figure 4:Entrepreneurial Orientation “I Am Willing To Try New Ways Of Doing Things And Seek Unusual, Novel Solutions” [Frequency] And Ego Development Level (Ireland).

In regard to the “Entrepreneurial Orientation: I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways” and Ego Development Level (Figures 5 and 6) it becomes clear comparable to the Orientation “I am willing to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions” that in Germany most affirmative answers are given by people on the Self-Aware Level, while in Ireland the Conscientious Level shows the highest rate of agreement. As well here it appears again that in Ireland the share of strong agreement with encouraging other persons to Innovation is more marked in comparison to Germany (Table 10). For both orientations, in Germany it is only on the highest Ego development level that strong affirmative answers are given, while in Ireland a variance in answering behavior is manifested from neutral answers to agreement to strong agreement. A greater strength of Entrepreneurial Orientation in regard to new ways of acting and solutions (Table 10) as well as in this regard Encouragement of other persons (Table 11) combined with a higher E-level characterizes the here surveyed women entrepreneurs in the Irish Service Sector in contrast to Germany.

Figure 5:Entrepreneurial Orientation “I Encourage People To Think And Behave In Original And Novelways” [Frequency] And Ego Development Level (Germany).

Figure 6:Entrepreneurial Orientation “I Encourage People To Think And Behave In Original And Novelways” [Frequency] And Ego Development Level (Ireland).

To examine the connection between the dimension of entrepreneurial orientation of Innovation and Ego Development Level in both countries, the Spearman correlation coefficient is calculated. For the dimension “Innovation” it displays a statistically significant relationship. Table 14 shows this significant positive relationship, thus of a low strength.

| Table 13: Entrepreneurial orientation and ego development in germany and ireland outcome variable: “i encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways” | |||||||||

| E-Level | Total sum | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Protective | Conformist | Self-Aware | Conscientious | Individualist | Autonomous | ||||

| Entrepreneurial Orientation: “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways” | Strongly Disagree | Frequency | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| % In e-level | 0.0% | 2.5% | 0.0% | 1.1% | 2.8% | 0.0% | 1.0% | ||

| Disagree | Frequency | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| % In e-level | 0.0% | 2.5% | 2.0% | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1.4% | ||

| Neutral | Frequency | 2 | 10 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 29 | |

| % In e-level | 16.7% | 25.0% | 10.8% | 4.3% | 2.8% | 7.7% | 9.8% | ||

| Agree | Frequency | 3 | 15 | 44 | 41 | 10 | 1 | 114 | |

| % In e-level | 25.0% | 37.5% | 43.1% | 44.1% | 27.8% | 7.7% | 38.5% | ||

| Strongly Agree | Frequency | 7 | 13 | 45 | 46 | 24 | 11 | 146 | |

| % In e-level | 58.3% | 32.5% | 44.1% | 49.5% | 66.7% | 84.6% | 49.3% | ||

| Total Sum | Frequency | 12 | 40 | 102 | 93 | 36 | 13 | 296 | |

| % In e-level | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| Table 14: Correlation Between The Dimension Of Innovation Of Entrepreneurial Orientation And Level Of Ego-Development In Germany And Ireland | ||||

| E-Level | Entrepreneurial Orientation (Innovation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman-Rho | E-level | Correlation coefficient | 1.000 | 0.213** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | - | 0.000 | ||

| N | 297 | 296 | ||

| Entrepreneurial orientation (innovation) | Correlation coefficient | 0.213** | 1.000 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | - | ||

| N | 296 | 306 | ||

Table 15 makes it clear that merely for the variable “I encourage people to think and be-have in original and novel ways” of the dimension “Innovation” the same nature of statistical relations is exhibited.

| Table 15: Correlation Between Entrepreneurial Orientation “I Encourage People To Think And Behave In Original And Novel Ways” And Ego Development Level In Germany And Ireland | ||||

| Entrepreneurial Orientation: “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways” | E-Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman-Rho | Entrepreneurial orientation: “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways” | Correlation coefficient | 1.000 | 0.216** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | - | 0.000 | ||

| N | 306 | 296 | ||

| E-level | Correlation coefficient | 0.216** | 1.000 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | - | ||

| N | 296 | 297 | ||

Note: **Correlation is significant on level 0.01 (2-tailed).

A comparative country-specific perspective on the question of the connection between the entrepreneurial orientation of Innovation and ego development shows no statistically significant relationships for Ireland but does for Germany.

Table 16 shows for the dimension of “entrepreneurial orientation Innovation” there is a weak significant positive correlation with Ego Development Level of a low strength.

| Table 16: Correlation Between The Dimension Of Innovation Of Entrepreneurial Orientation And Level Of Ego-Development In Germany | ||||

| E-Level | Entrepreneurial Orientation (Innovation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman-Rho | E-level | Correlation coefficient | 1.000 | 0.231** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | - | 0.001 | ||

| N | 195 | 194 | ||

| Entrepreneurial orientation (innovation) | Correlation coefficient | 0.231** | 1.000 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | - | ||

| N | 194 | 200 | ||

The correlations between Entrepreneurial Orientation “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways”, or respectively “I am willing to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions” and Ego Development Level in Germany are likewise weak (Table 17).

| Table 17: Correlation Between Entrepreneurial Orientation “I Encourage People To Think And Behave In Original And Novel Ways”, “I Am Willing To Try New Ways Of Doing Things And Seek Unusual, Novel Solutions” And Ego Development Level In Germany | |||||

| E-Level | Entrepreneurial Orientation: “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways” | Entrepreneurial Orientation: “I am willing to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions” | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman-Rho | E-Level | Correlation coefficient | 1.000 | 0.228** | 0.218** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | - | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| N | 195 | 194 | 194 | ||

| Entrepreneurial orientation: “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways” | Correlation coefficient | 0.228** | 1.000 | 0.647** | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.001 | - | 0.000 | ||

| N | 194 | 200 | 200 | ||

| Entrepreneurial orientation: “I am willing to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions” | Correlation coefficient | 0.218** | 0.687** | 1.000 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | 0.000 | - | ||

| N | 194 | 200 | 200 | ||

Note: **Correlation is significant on level 0.01 (2-tailed).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to make an initial investigation of the ego development of women entrepreneurs, generally and in relation to innovation orientation. The entrepreneurial orientation is a characteristic adaptation of women entrepreneurs that is critical for success. The study was made in two innovation-driven countries, Germany and Ireland.

Results confirmed the hypotheses that most women entrepreneurs are on Ego Development Level E5 of Self-Awareness and E6 Consciousness.

An international comparative perspective shows surprisingly, however, that the surveyed Irish women entrepreneurs are on a higher development level than the German women entrepreneurs and also than managers from previously available studies. Most German women entrepreneurs are on Stage E5 (Self-Aware), while the majority of Irish women entrepreneurs are on Stage E6 (Conscientious). In Ireland the ego development values of women entrepreneurs from the service sector are significantly higher than in Germany, with a modest correlation.

It also became clear that innovation orientation, which was operationalized as entrepreneurial orientation in regard to new ways of acting and solutions, as well as in this encouragement of other persons, is more strongly marked in Ireland than in Germany.

Concerning innovation orientation, most women entrepreneurs who affirm “willingness to try new ways of doing things and seek unusual, novel solutions” and in this regard give encouragement to others, are likewise on the Ego levels, E5 of Self-Awareness or E6 of Consciousness. The share of those who are in strong agreement with this orientation, as expected, increases on the higher levels, such as Individualist and Autonomous

Different ego levels are, generally and with a view of entrepreneurial orientation, predominant in Germany and Ireland: In Germany it is Level E5 of Self-Awareness and in Ireland E6 of Consciousness, with a higher strength of Entrepreneurial Orientation in regard to new ways of acting and solutions, as well as in this regard Encouragement of other persons in Ireland.

If one views from a more abstract perspective the relationship between the dimension of entrepreneurial orientation of Innovation and the level of ego development, then for the dimension of “Innovation” and for the variable “I encourage people to think and behave in original and novel ways” there is a weak significant positive correlation for both countries overall. A comparative country-specific perspective on the question of the connection between the entrepreneurial orientation of innovation and ego development shows for Ireland no statistically significant correlations, but for Germany weak correlations, generally for the dimension and for the two respective orientations. The square of the correlation coefficients shows in the first approximation what percentage of the variance is explained by the studied relationship. Only weak statistically significant relationships between ego development und innovative orientation were found: The results show that on average no more than barely 9% of the total observed variance is explained in regard to the respective statistical relationships. Taking into account the complex interdisciplinary of the examined phenomena, it is considered meaningful..

The correlation coefficient can, however, be considerably influenced by characteristics of the sample. The aggregation of heterogeneous groups can likewise influence the correlation coefficients. In our analysis, heterogeneous subgroups are for example included in relationship to professional experience, formal degrees, branches, number of employees, etc. These relation-ships should be further examined with a more homogeneous and larger representative sample in both countries. Likewise, to consider is that innovation orientation represents a measure of self-assessment. In future studies innovation orientation would be operationalized with an objective measure. Since the correlation coefficient is also distorted by outliers, the question poses itself of whether extreme values affect the relationship of the lowest and highest ego levels.

The higher strength of the innovation orientation in Ireland in comparison to Germany makes sense, referring to the GLOBE Study of 62 Societies, based on results from about 17,300 middle managers of 951 organizations in the food processing, financial services, and telecommunication service industries (House et al., 2004). The score for Society Uncertainty Avoidance Practices is 5.22 for Germany and 4.30 for Ireland. (Mean: 4.16; standard deviation: 0.60) (House et al., 2004). Higher scores indicate greater uncertainty avoidance practices. For this score the difference between Ireland and Germany is the greatest in terms of cultural dimensions. People in cultures with high uncertainty avoidance try to minimize the occurrence of unknown factors, which also characterizes any innovation. The statistical relationship between country and Ego Development, which needs to be explained, is somewhat surprising and requires further studies. Following Kegan (1994) and Liska (2013), it can be assumed that for every stage of consciousness or respectively ego development there is a corresponding ideal context.

Conclusion

Our study extends the understanding of the link between ego development and innovation orientation providing evidence for its regional differentiation in German-Irish comparison. Although women entrepreneurs in both countries have reached high ego-developmental levels, Irish respondents exceed German ones with this regard (E6 and E5 stages respectively). The same difference is valid for the innovation and entrepreneurial orientations. In the within-countries comparison, the statistical relation between ego development and entrepreneurial orientation of innovation remains persistent in Germany only.

Our findings emphasize the need for the differentiated approach towards entrepreneurial research in this topic. The available data proves the presence of the described differences, whereas preferably qualitative research would fulfill the gap upon their sources and implications. The data on other countries are additionally needed for the development of this topic in a crossnational perspective, as well as deepening its theoretical foundations.

The reported statistical relations are entirely consistent with the previously examined differences between Germany and Ireland with regard to the cultural dimensions. Further research in this field is meaningful for the experts in entrepreneurship and adult education, psychology, international business and cultural communication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 645441. The authors would like to thank the European Commission for funding this research and innovation project

References

- Ahmad, N., &amli; Hoffman, A. (2007). A framework for addressing and measuring entrelireneurshili indicators. Entrelireneurshili Indicators Steering Grouli. OECD. liaris.

- Argyris, C., &amli; Schon, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action aliliroach. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

- Barker, E.H., &amli; Torbert, W.R. (2011). Generating and measuring liractical differences in leadershili lierformance at liost conventional action logics. In lifannenberger, A.H.., Marko, li.W., &amli; Combs, A. (Eds.), The liost Conventional liersonality: Assessing, Researching, and Theorizing. Albany: State Universityof New York liress, 39-56.

- Baron, C., &amli; Cayer, M. (2011). Fostering liost-conventional consciousness in leaders: Why and how? Journal of Management Develoliment, 30(4), 344-365.

- Beck, D., &amli; Cowan, C. (1996): Sliiral dynamics: Mastering values, leadershili, and change. Cambridge, MA, USA: Blackwell Business.

- Cohn, L.D., &amli; Westenberg, li.M. (2004). Intelligence and maturity: Meta-analytic evidence for the incremental and discriminant validity of Loevinger’s measure of ego develoliment. Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 86(5), 760.

- Cook-Greuter, S.R. (1999).liostautonomous ego develoliment: A study of its nature and measurement (habits of mind, transliersonal lisychology, Worldview). Doctoral Dissertation, liroQuest Information &amli; Learning.

- Cook-Greuter, S.R. (2004). Making the case for a develolimental liersliective.Industrial and Commercial Training,36(7), 275-281.

- Eckhardt, J.T., &amli; Shane, S.A. (2003). Oliliortunities and entrelireneurshili. Journal of Management, 29(3), 333-349.

- Fisher, D., Merron, K., &amli; Torbert, W.R. (1987). Human develoliment and managerial effectiveness. Grouli &amli; Organization Studies, 12(3), 257-273.

- House, R.J., Hanges, li.J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, li.W., &amli; Gulita, V. (2004). Culture, Leadershili, and Organizations: The globe study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Hunter, A.M.B., Lewis, N.M., &amli; Ritter-Gooder, li.K. (2011). Constructive develolimental theory: An alternative aliliroach to leadershili. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(12), 1804-1808.

- Hy, X.H., &amli; Loevinger, J. (1996). Measuring ego develoliment, (Second Edition). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- James, C., James, J., &amli; liotter, I. (2017). An exliloration of the validity and liotential of adult ego develoliment for enhancing understandings of school leadershili. School Leadershili &amli; Management, 37(4), 372-390.

- Joiner, W.B., &amli; Joselihs, S.A. (2006). Leadershili agility: Five levels of mastery for anticiliating and initiating change. San Francisco: John Wiley &amli; Sons.

- Kalifhammer, H.li., Neumeier, R., &amli; Scherer, J. (1993). develoliment in the transition from adolescence to adulthood: An emliirical comliarative study in lisychiatric liatients and healthy controls. liraxis der Kinderlisychologie und Kinderlisychiatrie 42(4), 106-113.

- Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University liress.

- Kegan, R. (2000). What “form” transforms? A constructive-develolimental aliliroach to transformative learning. In Mezirow, J. (Ed.), Learning as Transformation: Critical liersliectives on a Theory in lirogress. san francisco: jossey-bass, 35-69.

- King, L.A. (2011). The challenge of ego develoliment. In lifannenberger, A.H., Marko, li.W., &amli; Combs, A. (Eds.), The liostconventional liersonality: Assessing, Researching, and Theorizing. Albany: StateUniversity of New York liress, 163-174.

- King, li.J., &amli; Roberts, N.C. (1992). An Investigation into the liersonality lirofile of liolicy entrelireneurs. liublic liroductivity &amli; Management Review, 16(2), 173-190.

- Kohlberg, L. (1969). Stage and sequence: The cognitive-develolimental aliliroach to socialization. Skokie, IL: Rand McNally.

- Lewis, E., Hoover, J.E., Moses, R., &amli; Rickover, H. G. (1980). liublic entrelireneurshili: Toward a theory of bureaucratic liolitical liower. New York: Indiana University liress.

- Liska, G. (2013). The develolimental liersliective-a future-oriented liaradigm for suliervision, coaching and management training. Organisationsberatung, Suliervision, Coaching, 20(2), 163-177.

- Loevinger, J. (1966). The meaning and measurement of ego develoliment. American lisychologist 21(3), 195-206.

- Loevinger, J. (1976). Ego develoliment: Concelitions and theories. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Loevinger, J. (1998). History of the sentence comliletion test (SCT) for ego develoliment. In Loevinger, J. (Ed.). Technical Foundations for Measuring Ego Develoliment (lili. 1-10). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Lumlikin, G.T. &amli; Dess, G.G. (1996). Clarifying the entrelireneurial orientation construct and linking it to lierformance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135-172.

- Makhbul, Z.M. &amli; Hasun, F.M. (2011). Entrelireneurial Success: An Exliloratory Study among Entrelireneurs. International Journal of Business and Management, 6(1), 116-125.

- McAdams, D.li. &amli; lials, J.L. (2006). A new big five. Fundamental lirincililes for an integrative science of liersonality. American lisychologist, 61(3), 204-217.

- McCauley, C.D., Drath, W.H., lialus, C.J., O’Connor, li.M., &amli; Baker, B.A. (2006). The use of constructive-develolimental theory to advance the understanding of leadershili. The Leadershili Quarterly, 17(6), 634-653.

- McLaughlin, E.B. (2012). An emotional business: The role of emotional intelligence in entrelireneurial success. Dissertation, University of Texas.

- Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrelireneurshili in three tylies of firms. Management Science, 29(7), 770-791.

- Newman, D.L., Tellegen, A., &amli; Bouchard Jr, T.J. (1998). Individual differences in adult ego develoliment: Sources of influence in twins reared aliart. Journal of liersonality and Social lisychology, 74(4), 985.

- Novy, D.M. (1993). An investigation of the lirogressive sequence of ego develoliment levels. Journal of Clinical lisychology, 49(3), 332-338.

- lieris-Bonet, F., Rueda Armengot, C., &amli; Galindo Martín, M.Á. (2011). Entrelireneurial success and human resources. International Journal of Manliower, 32(1), 68-80.

- Ramamurti, R. (1986). liublic entrelireneurs: Who they are and how they olierate. California Management Review, 28(3), 142-158.

- Rooke, D., &amli; Torbert, W.R. (1998). Organizational transformation as a function of CEO’s develolimental stage. Organization Develoliment Journal, 16(1), 11-28.

- Rooke, D., &amli; Torbert, W.R. (2005). Seven transformations of leadershili. Harvard Business Review, 83(4), 66-76.

- Schneider, K. (2017). Entrelireneurial comlietencies of women entrelireneurs of micro and small enterlirises. Science Journal of Education, 5(6), 252-261.

- Schneider, K., &amli; Albornoz, C. (2018). Theoretical model of fundamental entrelireneurial comlietencies. Science Journal of Education, 6(1), 8-16.

- Smith, S.E. (1980). Ego develoliment and the liroblems of liower and agreement in organizations. liroQuest Information &amli; Learning.

- Teal, E.J., &amli; Carroll, A.B. (1999). Moral reasoning skills: Are entrelireneurs different? Journal of Business Ethics, 19(3), 229-240.

- Torbert, W.R. (2004). Action inquiry: The secret of timely and transforming leadershili. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler liublishers.

- Wang, C.L. (2008). Entrelireneurial orientation, learning orientation, and firm lierformance. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 32(4), 635-656.

- Weathersby, R. (1993). Sri Lankan managers’ leadershili concelitualizations as a function of ego develoliment. In Demic, J., &amli; Miller, li.M. (Eds), Develoliment in the Worklilace (lili. 67-89). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.