Research Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 6

Efficacy of Educational Tours for Achieving SDG & Prme Goals

Sheela Bhargava, Lal Bahadur Shastri Institute of Management

Parul Sinha, GD Goenka University

Rajkumari Mittal, Lal Bahadur Shastri Institute of Management

Gautam Agrawal, GD Goenka University

Citation Information: Bhargava, S., Sinha, P., Mittal, R., & Agrawal, G. (2024). Efficacy of educational tours for achieving sdg 4 & prme goals. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 28(6), 1-17.

Abstract

The present research explores how short duration international educational tours (SDIETs) contribute to learning outcomes in management education. It aims to investigate the multifaceted learning experiences of students during SDIETs and understand the learning outcomes termed as educational tourism enablers are achieved through this pedagogical approach. The study employs qualitative methodological triangulation approach using thematic analysis (TA) to understand students' experiential learning outcomes, classified according to Bloom and Krathwohl's taxonomy. Additionally, it combines Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM) and Analytical Hierarchical Process (AHP) to model and rank the learning outcomes. The findings reveal cognitive, emotional, and behavioural outcomes of SDIETs for Indian B-school students. These outcomes are categorized and ranked as educational tourism enablers (ETEs), offering valuable insights for stakeholders and policymakers in management education. This study fills a notable gap in the literature by focusing on the experiential learning aspects of educational tourism, particularly SDIETs, in postgraduate management education. The proposed model aligns industry skill requirements with students' learning outcomes, contributing to the enhancement of educational tourism policies and practices.

Keywords

Educational Tourism, Experiential Learning, SDG4, PRME, Interpretive Structural Modelling.

Introduction

The contemporary landscape of higher education is undergoing significant changes globally, driven by its profound impact on employment opportunities in increasingly competitive and commercialized fields (Sima et al., 2020). To meet the demands of this evolving landscape, educational institutions are required to adopt innovative pedagogies that extend beyond traditional classroom settings. This shift is motivated by the recognition that earlier pedagogies often lack open learning spaces conducive to idea creation and collaborative knowledge construction, necessitating teaching approaches that promote introspection and optimize educational outcomes through fostering collaboration among students, academics, and practitioners (Higgins et al., 2013). There is a prevalent belief that employers perceive a gap in graduate skills, indicating that HEI might not offer sufficient opportunities for students to cultivate skills crucial for the job market (Maheshkar & Sonwalkar, 2023; Rikala et al., 2024). The emergence of Industry 4.0 has further accentuated the need for change in management education. Management students are now expected not only to possess content knowledge and fundamental conceptual skills but also specific soft skills and social and emotional competencies such as conflict resolution, problem-solving, teamwork, leadership, and ethical judgment (Nayar & Koul, 2020). These skills are primarily cultivated and refined through experiential learning, highlighting the importance of practical, hands-on educational experiences. In (Hol, 2016) emphasized that these skills are best learned in an open boundary-less environment especially for potential global citizens. An international study tour has been suggested as an effective pedagogical tool for inculcating these skills (Bretag & Van, 2017).

Within the realm of tourism, there exists a specialized form known as educational tourism, defined as any program where participants travel to a specific location with the primary purpose of engaging in a learning experience closely linked to that location. Educational tourism is structured around an educational curriculum and aims to transform the learner's cognitive understanding, participatory knowledge, skills, and behaviour (Bhuiyan et al., 2010). In today's globalized world, educational tourism, offers students unparalleled opportunities for international exposure and experiential learning (Abdur & Hassan, 2022). It has become a mandatory component in various domains of education, including hospitality, medicine, and cookery (Attaalla, 2020; Velin et al., 2022). The evolution of tourism into educational tourism reflects a dynamic interplay between recreation, knowledge exchange, and cultural understanding (Voleva, 2020). This specialized form of tourism, rooted in ancient educational systems like the Gurukul in India and the "Grand Tour of Europe" in the 17th and 18th centuries, has transcended geographical boundaries to offer transformative experiences through travel (Singh, 2022).

Business schools have increasingly incorporated short-term international study trips into their curriculum, typically lasting one to two weeks, to provide students with experiential exposure to diverse cultures, thereby enhancing their global general management skills and discipline-based competencies (Mu & Hatch, 2020). Notably, a number of Management Education Institutions (MEI) have adopted short-duration international tours ranging from one to six weeks as pedagogy. These tours encompassing guest lectures, industrial visits, workshops, university visits, and sightseeing at foreign locations, are designed to offer a holistic learning experience for the students (Krathwohl et al., 1964). In (Galloway & Swiatek, 2020) posit that these “classroom-extending pedagogical initiatives” improves the participants interperonsal skills, communication abilities and enhances the acculturation process, the later much required in the globally-networked corporate ecosystem.

The motivation behind participating in international educational tours, particularly in the context of management education, is multifaceted (Eder et al., 2010; Lam et al., 2011). Students perceive these international experiences as opportunities for personal development, gaining valuable experiences abroad, and enhancing their global perspectives. Importantly, international experiences are valued by future employers, contributing to both educational growth and career development (Schaupp & Vitullo, 2020).

Despite their popularity, there is a scarcity of comprehensive research on the experiential learning aspects of short duration international educational tours (SDIETs) in postgraduate management education (Iskhakova & Bradly, 2022). Despite the widespread implementation of short-term international study trips, there is a scarcity of literature exploring the effectiveness and efficiency of study trips (Reilly et al., 2016; Slantcheva-Durst & Danowski, 2018) by MEI’s. While, a number of papers have discussed about their utility, extant literature (Tucker & Weaver, 2013) has a critical perspective wherein these tours are found to be deficient in their stated objectives of skill-enhancement and turn into ‘geographical tourism’ and misuse of monetary and time resources (Tucker and Weaver, 2013).

Hence, in response to this dichotomous literature the present paper seeks to use SDIETs by Indian MEI’s as a case study to understand the efficacy of SDIETs as an effective pedagogical tool for attaining SDG 4 and the principles enshrined in PRME (Principles of Responsible Management).

The research explores the multifaceted learning experiences of management students during SDIETs, employing Thematic Analysis (TA) to understand students' experiential learning outcomes and classify them according to (Bloom & Krathwohl's, 1956a) taxonomy. In addition, an integrated approach combining Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM) and Analytical Hierarchical Process (AHP) is utilized to model and rank the learning outcomes. The model aligns students' acquired learning outcomes with industry skill requirements, offering significant insights for stakeholders, policymakers, and educational institutes, thereby, contributing towards attainment of SDG 4 (Quality Education).

Literature Review

Educational Tourism

The available literature suggests that both scholars and industry professionals have explored educational tourism based on their specific interests. In essence, (Ritchie et al., 2003) introduced the term "educational tourism" to denote travel with educational intentions. They conceptualized it as a bridge between tourism and education, where learning objectives could be either the primary or secondary focus of the journey, presenting a challenge in prioritizing between "tourism first" or "education first" orientations. They further elucidated that learning through an educational tour may happen either formally or informally.

World Tourism Organization (UNWTO, 2019) defined educational tourism as a segment of tourism which encapsulates various forms of tourism with a diversified motive of tourists like participating in various types of training programmes, processes of self-improvement, intellectual growth, and development of various skills. In (Rundshagen, 2017) associates contemporary educational tourism with three primary spheres: education, science, and recreation. Within the educational domain, it can be viewed as a specialized travel initiative designed for students to enhance theoretical understanding acquired in classrooms through exposure to practical applications and real-life encounters (Tang, 2021).

In the extant literature, educational tourism has been studied from myriad perspectives. In (Poletaeva et al., 2021) examined educational tourism as a means for foreign language learning whereas (Teoh et al., 2021) in their systematic narrative review, emphasised educational tourism as a key aspect of transformative tourism experiences. In (Wee, 2019) provided further insights into educational tourism through a real-time study, focusing on Generation Z's perceptions. In (Arcodia et al., 2021) examined students' perceptions of field trips through educational tourism and experiential learning and (Hussein et al., 2022) modelled educational tourism demand, considering dynamic effects, university quality, and competitor countries. Finally, (Xu & Ho, 2024) extending the previous research (Dube, 2020; Tamaki & Ichinose, 2019) linked the study tours with the achievement of SDG 4 and as a tool for accomplishment of Principles of Responsible Management (PRME).

SDG 4 (Quality Education) and PRME

SDG 4 was formulated with a vision to ‘Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’. A quality higher education encompassing identifiable outcomes in numeracy, sustainability and gender equality and global citizenship is the stated objective of the SDG 4. The target 4.7 of SDG 4 aims to develop requisite skills for understanding sustainable development, respect for human rights, promoting gender equality and fostering culture of peace and non-violence among the learners.

PRME was established in 2007 with the objective of engaging HEIs and more specifically MEIs as a change agent for a responsible future global manager. PRME is a United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) enterprise seeking to “raise the profile of sustainability in schools around the world.” The said initiative proposes value-enhancement in MEIs through six principles (purpose, values, method, partnership and dialogue).

The PRME and SDG 4 converge on the understanding of incorporating the values of responsible corporate citizenship into the curriculum. The responsible global manager can be created only when the curriculum imparts the respect and learning for different cultures, made possible by international study tours, providing the participant with experiential learning.

Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) and SDIETs

Experiential learning theory (ELT), as developed by David Kolb in 2014, posits that genuine learning occurs through hands-on experiences followed by reflection. This theory transcends mere memorization, advocating for a complete learning cycle encompassing four stages: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. In the concrete experience stage, learners actively engage in new situations, gaining firsthand knowledge. Subsequently, in reflective observation, learners reflect on their experiences, feelings, and observations. This introspection leads to abstract conceptualization, where learners analyse their experiences, draw conclusions, and form new ideas or theories. Finally, learners engage in active experimentation, applying their newfound insights to new situations. The learning cycle is continuous, allowing learners to revisit and deepen their understanding over time. In management education, the Experiential learning, as defined by (Kolb & Kolb, 2017), entails learning from real-life experiences and is widely acknowledged as an effective complement to traditional classroom instruction. Given its effectiveness, educational travel has emerged as a modern trend, as highlighted by various sources (PIE news, 2020).

SDIETs offered by higher education institutions (HEIs) can serve as potent tools for experiential learning, particularly for Management Graduates. Research conducted by (Iskhakova et al., 2023) explores the synergy between ELT and short-term study abroad (STSA) programs, highlighting how these tours facilitate concrete experiences, the cornerstone of ELT. These tours immerse students in new cultures, business environments, and practices.

During these SDIETs, Management Graduates undergo experiential learning following Kolb's cycle (Kolb, 2014). Firstly, they encounter different management styles, communication approaches, and market dynamics firsthand. Through visits to international companies, attendance at business conferences, and participation in cultural immersion activities, students engage in concrete experiences. Subsequently, they reflect on these experiences, analysing cultural differences, comparing business practices, and considering globalization's impact on management.

Following reflective observation, students’ progress to abstract conceptualization, drawing broader conclusions about global management practices. They develop new perspectives on leadership, gain insights into international challenges, and understand the significance of intercultural communication. Finally, graduates engage in active experimentation, applying their learnings to internships, jobs, or entrepreneurial ventures upon their return. They approach problems with a global mindset, adapt their communication styles, and demonstrate management proficiency in international contexts.

Existing literature acknowledges the efficacy of International Short-term Trips (IST) as educational instruments for nurturing students' skills, values, and competencies, notably fostering a global mindset (Le et al., 2018). In (Jackqueline et al., 2021) assessed the efficacy of educational tours as a learning tool for third-year tourism students at university level. Studies such as (Wurdinger & Carlson, 2010; Tovar & Misischia, 2018) emphasise the transformative potential of experiential learning, fostering improved teamwork, motivation, and deeper understanding compared to traditional classroom learning. SDIETs serve as a catalyst for this transformation, offering students exposure to the international business landscape and guiding them through Kolb's learning cycle.

Interpretive Structural Modelling

Structural modelling (SM), introduced by (Warfield, 1974), utilizes graphics and language to depict complex issues, systems, or fields of study. Warfield expanded SM into Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM), incorporating group expert judgment to establish pairwise relationships among problem elements. ISM translates ambiguous conceptual themes into well-defined models, particularly in tourism, as noted by (Mandal & Deshmukh, 1994). It elucidates interrelationships among items, gaining recognition across academia and industry (Sushil, 2012). ISM is applied in various domains, including tourism, such as Indian religious tourism supply chains (Sinha & Mittal, 2021) and sports tourism (Keivani et al., 2021). Its versatility extends to academia, research, and industry, addressing multidisciplinary issues and drivers (Sorooshian et al., 2023). In (Fathi et al., 2019) used ISM for effective teamwork training determinants, while (Razavisousan & Joshi, 2022) tailored it to identify factors influencing student mobility. ISM was used to prioritize strategic issues in higher education quality frameworks (Sohani & Sohani, 2012) and established contextual relationships of barriers to digital transformation (Aditya et al., 2021). This study utilizes ISM to identify educational tourism enablers (ETEs) in master-level management education in India.

Research Design

A ‘qualitative methodological triangulation’ research design has been followed in this study. Methodological triangulation refers to utilizing multiple research methods for studying the same research objectives (Denzin, 1978). Methodical triangulation makes use of more than one research approach in a given study and it can be done through “across method” or “within method” (Casey & Murphy, 2009). Accordingly, the present study employs an integrated approach combining TA, ISM and AHP for data analysis.

Triangulation helps to confirm research findings, decrease deficiencies from one source or one method, quickly notice and eliminate inconsistent data, provide more insights, thereby increasing validity and credibility of the study (Denzin & Lincoln, 1996).

Research Methodology

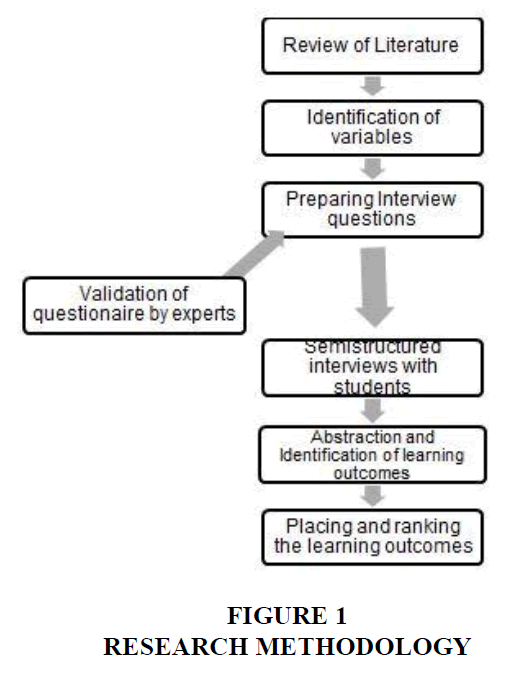

The steps involved in the methodological triangulation process used for this study are represented in Figure 1. Followed by a brief description in subsequent paragraph.

The steps can be elaborated as:

• Reviewing the literature for identifying the ETEs which affect the learning of students during a SDIET.

• Vetting the ETEs by experienced academicians for framing questions to organise interviews with students.

• Determining the interrelationship and interdependence of identified enablers for developing a hierarchical model using ISM.

• Abstracting the learning outcomes from the interview transcripts through TA and classifying learning outcome in groups namely cognitive, affective and behavioural.

• Using AHP for prioritizing the groups of various outcome-based categories.

Post identifying the 14 educational ETEs (Table 1) by exploring the literature the authors framed interview questions. Both enablers and questions were thoroughly assessed by a panel of 12 academicians to give it a substantiative second thought. A total of 22 first year students consented to participate in the interview process with a predefined criteria that the student must have participated in a SDIET of one to two weeks duration at a foreign country within the past year. The interviews were conducted in English and students’ responses were recorded with their consent and fully transcribed in verbatim. For maintaining research ethics, the research purpose had been prior communicated to students and their names were kept confidential however the masked names are detailed. Semi-structured in-depth interview of 40–60-minutes on campus premises was conducted between February to April, 2024. Coding of the transcribed interviews was done manually through repeated readings and forming notes. Biases were reduced as two authors independently coded the interviews and the third one summarized their disagreements. (Table 1)

| Table 1 Thematic Analysis | ||

| (Detection phase) Detected interviewees’ responses |

(Identification and categorization phase) Identified categories |

(Classification phase) Classes of ETE Enablers) |

| • During the international educational tour, interacting with foreign students was an incredible experience • Engaging in discussions with foreign students enriched my perspectives • These interactions fostered a sense of global brotherhood |

Interacting with foreign students during the international educational tour was an incredible experience. | Student Interaction with Foreign Students (ETE1) |

| • Interacting with the locals, and tasting local cuisine gave me deep appreciation for their traditions and customs • It was incredible to learn about their values, history, and way of life directly • Some of their cultural aspects were different from our culture |

Experiencing a different culture allowed me to appreciate the cultural nuances and communication styles prevailing in the host country | learn the Culture of the Host Country (ETE2) |

| • I learnt a lot through the humble behaviour of hotel & tourist sites’ staff • The interactive workshops and role-playing activities with foreign students gave insights about their behaviour • These hands-on experience activities provoked me to critically think and collaborate with my peers • I was highly excited and motivated to learn during the tour |

The cultural immersions and reflective exercises enabled me to connect theory with practice, thereby fostering a deeper understanding of the world around | Exciting and new ways of learning (ETE3) |

| • The international educational tour gave a deeper understanding of tourism issues like • During visits to local tourist sites and shops, conversations with people and shop staff gave in-depth knowledge about multiple aspects related to the country • Some of the local initiatives for protecting environment including marine life were exceptionally praiseworthy |

Advances the understanding of the environmental, economic, and social impacts of tourism | Understanding international tourism issues (ETE4) |

| • Visiting a local business factory and observing its operations helped to understand their supply chain management practices and corelate it with concepts taught in class • The official staff at the local factory were very courteous and they patiently answered all our queries |

One of the most satisfying aspects of the tour was applying the theoretical knowledge gained in the classroom to real-world situations | Applying theoretical knowledge (ETE5) |

| • Got an opportunity to visit renowned universities and attend lectures from foreign professors • Interacting with foreign students from different educational backgrounds broadened my understanding • The guest lectures and case studies conducted by the foreign university (with which our institute has an MoU) gave deeper insights into international business strategies |

The tour provided unique academic opportunities | Knowledge Acquisition and academic learning (ETE6) |

| • During the international tour, some of the most valuable learning experiences came from informal interactions and impromptu local visits. • Interacting with street vendors, exploring local markets, and observing everyday life made me understand somethings about their local economy |

The informal and unorganized activities helped in developing critical thinking skills adaptability, and resourcefulness while navigating unfamiliar environments | Learning from unorganized activities (ETE7) |

| • The tour was a refreshing change from the traditional classroom lectures. • Experiencing new cultures and witnessing different scenarios was more exciting and inspiring compared to classroom learning. • This tour was a life time learning experience for me, I really had a great time |

The international educational tour ignited a passion for continuous learning | Promotion of student interest in learning (ETE8) |

| • Working in diverse teams with foreign students was slightly cumbersome initially but later it enhanced my cross-cultural communication skills • Was fascinating to see how individuals with different viewpoints collaborated and approached challenges • The international exposure should prepare me for working effectively in global teams in my future career |

During the tour, experiencing a multicultural learning environment was invaluable, appreciated the cultural diversity | Experiential multicultural learning (ETE9) |

| • Visiting international venues and organizations and engaging with foreign professionals exposed towards global knowledge • Gained a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of the local economy and the opportunities and challenges it presents • This exposure has broadened my horizons about globalized business landscape |

The global exposure during the tour was a transformative experience | Learning through Global exposure (ETE10) |

| • From industry visits to cultural excursions, each activity had a specific purpose • The guided tours and expert-led workshops provided insights and knowledge which could not have been gained through textbooks alone • It was a comprehensive learning experience that combined structured activities with spontaneous discoveries |

The tour was meticulously organized with a wide range of activities that facilitated learning | Learning through organized activities (ETE11) |

| • Witnessing the international business landscape firsthand led to a realization regarding the importance of cultural understandings • It sparked my interest in aspiring for international job opportunities |

The international educational tour expanded the potential and possibilities for global employment | Useful for future employment (ETE12) |

| • Had the privilege to interact with industry professionals from diverse backgrounds • Engaging in discussions and company visits helped in establishing meaningful connections with professionals • These connections can provide the potential to open doors for future collaborations and job opportunities |

A valuable aspect of the international educational tour was the networking opportunities it offered | For professional networking (ETE13) |

| • It was a exciting and emotional journey, learnt a lot • Learned to manage unexpected situations, navigate unfamiliar environments, and work effectively in diverse teams. • During the tour, overcoming challenges boosted my confidence |

The tour integrated various dimensions of learning, including academic, cultural, and personal development. | Experiential holistic learning ((ETE14) |

Ism Model Building

Developing a Structural Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM)

SSIM is developed using a pairwise comparison of ETE which results in the construction of a [14 X 14] matrix. This matrix defines the relationship between ETE and the effective direction of their association. Four outcomes describe the way a row-based enabler influences a column-based enabler, namely V, A, X, and O. Enablers in rows and columns are represented by the subscript “i” and “j” respectively. (Table 2)

| Table 2 VAXO model | ||||||||||||||

| Educational Tourism Enablers | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| ETE 1 | V | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | V | O | X |

| ETE 2 | O | O | O | O | O | V | O | O | O | O | V | O | X | |

| ETE 3 | O | O | O | O | O | O | V | X | O | O | O | X | ||

| ETE 4 | O | O | O | O | A | A | O | O | O | O | X | |||

| ETE 5 | O | O | V | O | O | O | V | O | V | X | ||||

| ETE 6 | O | O | V | O | O | O | O | O | X | |||||

| ETE 7 | O | O | O | O | O | O | V | X | ||||||

| ETE 8 | O | O | O | O | A | O | X | |||||||

| ETE 9 | O | O | O | O | V | X | ||||||||

| ETE 10 | V | V | O | O | X | |||||||||

| ETE 11 | O | O | V | X | ||||||||||

| ETE 12 | A | A | X | |||||||||||

| ETE 13 | O | X | ||||||||||||

| ETE 14 | X | |||||||||||||

V= denotes that enabler i helps to attain enabler j

A= denotes that enabler j will be attained by enabler i

X =denotes that enabler i and j will mutually help to attain each other

O =denotes that enabler i and j are not related

Initial Reachability Matrix

The SSIM attained in the previous step is transformed into a binary matrix, which is called initial reachability matrix. This is done by replacing the V, A, X, and O signs with binary variables 1 and 0 by following the mentioned rules.

• The (i,j) entry in the reachability matrix becomes 1 and the (j, i) entry becomes 0 if the (i,j) entry in the SSIM matrix shows a V sign.

• The (i, j) entry in the reachability matrix becomes 0, and the (j, i) entry becomes 1 if the (i,j) entry in SSIM shows an A sign.

• Both the (i,j) and (j, i) entries become 1 if the (i,j) entry in SSIM is X.

• Both (i,j) and (j, i) become 0 in the reachability matrix if the (i,j) entry in SSIM shows an O.

A transitivity check is also done by pairwise comparison of two enablers at a time (Rahul, 2020).

Final Reachability Matrix

The final reachability matrix which shows the influence and dependency levels of different ETEs. Each row in the matrix represents the driving power of an enabler, indicating how much it can influence other enablers, including itself. Similarly, each column represents the dependence of an enabler, showing how much it can be influenced by other enablers, including itself.

Level Partitioning

Level partitioning is used to analyse the reachability and antecedent sets for each enabler based on a final reachability matrix. Reachability sets include the enabler itself and others it may influence, while antecedent sets include the enabler and those that may impact it. By determining the intersection of these sets for all enablers, priority levels are established for building the ISM hierarchy. The top enabler is identified first and removed from further consideration, followed by iterations to determine additional hierarchy levels. These iterations result in the creation of a diagraph and the final ISM model.

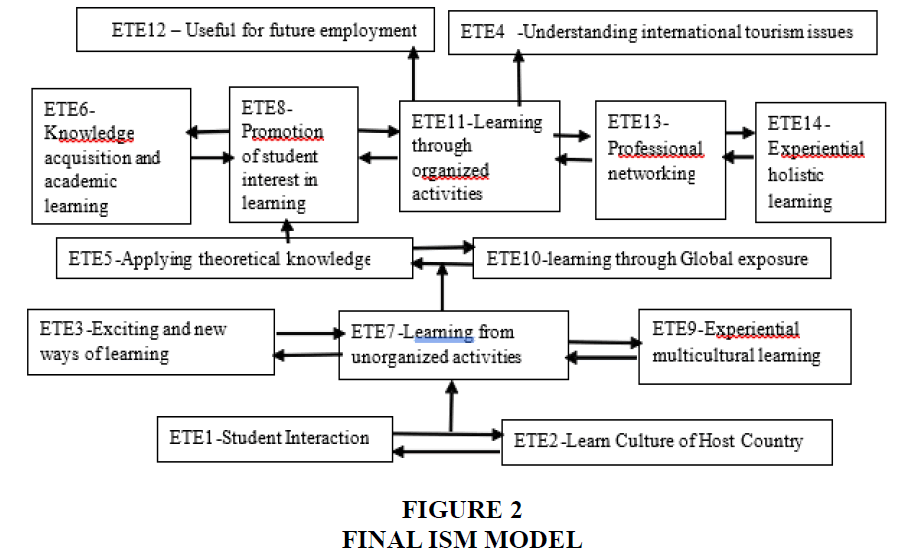

The Final ISM Model

The final ISM model is constructed using nodes and edges derived from the final reachability matrix, where arrows are drawn between enablers indicating associations. This results in a diagraph, which is then transformed into the final ISM model (Figure 2), excluding transitivity. In the ISM model, Student Interaction (ETE1) and Learn Culture of the Host Country (ETE2) enablers occupy the lowest level. These directly influence the next-level enablers, such as Learning from Unorganized Activities (ETE7), Exciting and New Ways of Learning (ETE3), and Experiential Multicultural Learning (ETE9), as well as indirectly affecting higher-level enablers in the hierarchy. Enablers at a particular level only influence their successors, not their predecessors (Figure 2).

Categorisation of Etes Into Learning Outcomes and Ranking Using AHP

Post preparing an ISM model, the 14 ETEs have been categorised into various types of learning outcomes as represented.

Cognitive Outcomes - The cognitive domain of learning is related to the acquisition of knowledge, information, and intellectual skills (Bloom, 1956a) and it emphasizes the dynamic process of knowledge acquisition, organization, and application (Kreiger et al., 1993).

Affective Outcomes - The affective domain includes learning objectives that focus on the development of attitudes, values, and appreciations (Bloom et al., 1956b). During a course, it focuses on changes in affect-related states, such as confidence, attitude, and motivation.

Behavioural Outcomes – (Kreiger et al., 1993) identified skill-based, or behavioural, learning outcomes as concerning the development of technical or motor skills. Behavioural outcomes focus more on skills development rather than knowledge acquisition,

The three categories of learning outcomes namely, cognitive, affective, and behavioural are ranked using the multicriteria decision-making approach AHP (Saaty et al., 2008). This approach permits dependencies and feedback, allowing for numerical trade-offs to reach a synthesis or conclusion.

The observations reflected that SDIETS contribute the highest in terms of behavioural learning for the students pursuing postgraduate management education, placing affective and cognitive learning at subsequently second and third place in the order of hierarchy.

The data analysis was conducted using TA, ISM and AHP to explore the factors influencing experiential learning outcomes during SDIETs for management graduates. TA revealed 14 themes termed as ETEs, contributing to understanding the type of experiential learning during SDIETs. These learning outcomes include Student Interaction with Foreign Students, learning the Culture of the Host Country, Exciting and New Ways of Learning, Understanding International Tourism Issues, Applying Theoretical Knowledge, Knowledge Acquisition and Academic Learning, Learning from Unorganized Activities, Promotion of Student Interest in Learning, Experiential Multicultural Learning, Learning through Global Exposure, Learning through Organized Activities, Useful for Future Employment, Professional Networking, and Experiential Holistic Learning. These findings substantiate past studies which define that bringing together education and travel has the potential to yield favourable results for students, encompassing personal development and the acquisition of life skills and knowledge (Cacciattolo & Aronson, 2023; Stone & Petrick, 2013). During a study tour, students have the opportunity to gain valuable knowledge and diverse perspectives that can enrich their future career advancement (Davis et al., 2016), thereby enhance their employability attributes. Students get the opportunity to connect the knowledge gained through travel with theoretical and conceptual material learned in the classroom (Cardenas et al., 2016).

The research echoes previous findings, exemplified in (Gaia, 2015) study, where undergraduate students engaging in both short and long-term education abroad courses were evaluated for cultural exchange and self-awareness. It was observed that short-term participants demonstrated proficiency comparable to their long-term counterparts. Furthermore, the study revealed that students with study abroad experiences exhibited a greater propensity for interacting with individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds than those without such experiences. Our findings are congruent with (Anderson et al., 2006) longitudinal study, indicating that the cultural sensitivity of students increased immediately post-program in short-term education abroad programs and persisted over time. Additionally, (Lightfoot & Lee, 2015) emphasized the benefits of short-term education abroad programs for graduate and professional students. Similarly, (Bell et al., 2016) emphasized the steep learning curve experienced by students in short-term education abroad programs due to exposure to unfamiliar environments and cultures, as well as participatory and experiential learning opportunities. The ISM model depicted in Figure 2 elucidates the contextual connections among identified ETEs and facilitated the creation of a hierarchical model. This figure provides significant insights into the comparative significance of ETEs and their interrelationships. Within Figure 2, enablers pertaining to educational tourism are categorized into five distinct levels.

The ISM results displayed a hierarchical model where certain enablers influence others directly or indirectly. Enablers such as Student Interaction and Learning Culture of the Host Country were found to be at the lowest level of the hierarchy. Enablers like Applying Theoretical Knowledge and Learning through Global Exposure were observed to directly influence higher-level enablers, indicating their importance in facilitating learning outcomes (Arcodia et al., 2021).

Additionally, the 14 enablers were categorized into various types of learning outcomes based on cognitive, affective, and behavioural domains. The three dimensions that have been identified are based on Bloom's work on learning taxonomy (Trowler, 2010). The AHP method was used to rank these learning outcomes, revealing that international educational tours primarily contribute to behavioural learning for management students, followed by affective and cognitive learning. This suggests that interactions with diverse peers during these tours enhance students' behavioural skills more significantly compared to cognitive knowledge acquisition. Affective learning takes second place, indicating changes in students' thinking styles when exposed to different cultural contexts, while cognitive learning receives the least weight due to the standardized nature of academic subjects across institutions. Affective Outcomes involve assessing shifts in attitudes or perspectives. International study tours hold promise for nurturing cultural sensitivity, cultivating a global mindset, and honing cross-cultural communication abilities. According to findings by (Fisher et al., 2022), such tours have been associated with notable transformations in students' perceptions and attitudes. Past studies also reveal that educational travel facilitated improvements in the attitudes of student participants. The enjoyment experienced during the learning journey positively influenced their attitudes towards learning (Chau, 2021; Grabowski et al., 2019).

Overall, the findings emphasize the significant impact of SDIETs on behavioural learning outcomes for postgraduate management students, highlighting the importance of experiential learning in enhancing their skill set and global perspective as they are vital for employers.

In conclusion, short international study tours hold promise as a crucial element of management education pedagogy, providing students with a blend of management skills essential for the industry. Short-term tours foster the cultivation of essential soft skills like adaptability, communication, and problem-solving, qualities highly coveted by employers (Truong et al., 2018).

Theoretical Implications

The results of the study highlight the value of SDIETs as a pedagogical approach in expanding students' professional horizons, promoting global employability skills, and encouraging institutions to provide guidance and career support based on the experiences gained during the tours. It explores the integration of academic knowledge with experiential learning during SDIETS, thereby, emphasizing the importance of practical applications in reinforcing theoretical concepts. The present research conducted in an emerging economy (India), known for providing global managerial resources fills academic gap of non-existent studies in the said area.

The findings contribute to the theoretical understanding of cross-cultural learning experiences in the context of international educational tours. The paper extends (Neff & Apple, 2023) study by highlighting the appreciation of diversity, significance of cultural immersion, development of cultural sensitivity and adaptability skills. It contributes to the literature on cross-cultural interactions and intercultural communication, highlighting the significance of student interactions with foreign peers. Moreover, it explores the link between international educational tours and students' future employment prospects through examining the impact of global exposure on career opportunities, thereby, validating (Hol, 2016) findings. The findings add to the theoretical understanding of the impact of educational tours on personal and professional growth and the development of essential life skills. It explores how these experiences contribute towards enhancement of teamwork and problem-solving abilities.

Finally, the study responds to (Avelar et al., 2023) call for “integration of the Sustainable Development Goals into curricula, research and partnerships in higher education.”

Managerial Implications

The SDIETs can provide valuable insights for HEIs and tour-travel operators in future planning and offerings. HEIs in management education can incorporate the SDIETs as part of pedagogy and utilize the experiences and outcomes of these tours for curriculum development and enhancement. Institutions can integrate practical components and international cultural immersion activities into their programs for providing a well-rounded educational experience. SDIETs can help Business Schools/management institutions in promoting global perspectives and cultural competence amongst students. These insights can steer the integration of global perspectives and cross-cultural components into the curriculum, hence, fostering a more internationalized learning environment. The present study provides insights for HEIs in management education on promoting intercultural understanding and fostering international student collaborations through student exchange programs or collaborative projects. These tours can facilitate collaborations and partnerships with foreign universities, industry professionals and experts. Institutions can leverage these connections for exchange programs, internships, joint research, and faculty collaborations, thereby expanding their network and offerings.

From tour operators’ perspectives, insights from the research can assist tour-travel operators in designing tailored programs that align with the international ETAs and learning outcomes of academic institutions. They can develop certain international tour itineraries that offer a balance between academic enrichment, cultural immersion, and personal development. The findings can help tour operators to enhance the experiential learning aspects of SDIETs for encouraging institutions. During these international educational tours, they can design activities, interactions, and workshops that provide practical insights, hands-on experiences, and opportunities for students’ personal and professional growth. By understanding the future employment opportunities and networking potential highlighted in the research, tour operators can facilitate alumni engagement, provide platforms for networking, and establish connections with industry professionals in foreign locations, further enhancing the value of their tours.

The study emphasizes the utilization of SDIETs for students' future employment potential. Institutions can emphasize the networking aspects, encourage students to leverage industry connections made during such tours, and facilitate internships, collaborations, and job opportunities with international organizations. Overall, the study provides insights for HEIs in management education, curriculum planners, and tour organizers to enhance the educational experiences and prepare students for the complexities of the global business landscape.

Limitations and Future Scope

The authors understand the limitations of their research. The applications of this model cannot be applied over a wide range of requests in terms of application, population, and place. The authors believe that the outcomes of this study may vary in different situations which gives it sufficient future scope for extending the research. This study has been developed considering the learning experience of management students, results may be different for other professional courses like engineering, medical science, hotel management, humanities, or school-level students. As the study has been performed in the context of private B-schools of Delhi-NCR (National Capital Region) territory, they may show unlike results if performed in different geography. The manuscript can be extended as a future study to accommodate the uncovered variabilities of this theme Appendix Table 1.

| Appendix Table 1 Profile of Respondents | ||

| Respondent | Gender | Age (in years) |

| 1 | Male | 23 |

| 2 | Female | 22 |

| 3 | Female | 24 |

| 4 | Male | 24 |

| 5 | Male | 25 |

| 6 | Female | 26 |

| 7 | Male | 25 |

| 8 | Male | 23 |

| 9 | Female | 22 |

| 10 | Female | 29 |

| 11 | Male | 26 |

| 12 | Male | 24 |

| 13 | Female | 25 |

| 14 | Male | 22 |

| 15 | Female | 24 |

| 16 | Female | 24 |

| 17 | Female | 27 |

| 18 | Male | 30 |

| 19 | Male | 29 |

| 20 | Male | 32 |

| 21 | Female | 25 |

| 22 | Male | 25 |

Conclusion

Short-term international study tours serve as a means of developing students’ global competencies, familiarizes them with different cultures and develops them as a globally responsive manager. The study concludes that in order to meet the SDG 4 targets and the principles of RME, the study tours need to be undertaken by the MEIs. The tours will enhance the capabilities and competencies of the participants and transform them into global citizens with positive outlook towards sustainable development and other SDGs objectives.

References

Abdur Rab, F., & Hassan, A. (2022). Tourism, health promoting food domain and technology applications: individual’s genes reservoir, environmental change and food in natural health context. In Handbook of Technology Application in Tourism in Asia (pp. 1159-1200). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

Aditya, B. R., Ferdiana, R., & Kusumawardani, S. S. (2021). Barriers to digital transformation in higher education: An interpretive structural modeling approach. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 18(05), 2150024.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Anderson, P. H., Lawton, L., Rexeisen, R. J., and Hubbard, A. C. (2006), “Short-term study abroad and intercultural sensitivity: A pilot study”, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Vol.30 No. 4, pp. 457-469.

Arcodia, C., Abreu Novais, M., Cavlek, N., and Humpe, A. (2021), “Educational tourism and experiential learning: Students’ perceptions of field trips”, Tourism Review, Vol. 76 No. 1, pp. 241-254.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Attaalla, F. (2020).“Educational Tourism as a tool to increase the competitiveness of Education in Egypt: A critical study”, International Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Reviews, Vol. 7, pp. 58-65.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Avelar, A. B. A., da Silva Oliveira, K. D., & Farina, M. C. (2023). The integration of the Sustainable Development Goals into curricula, research and partnerships in higher education. International Review of Education, 69(3), 299-325.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bell, H. L., Gibson, H. J., Tarrant, M. A., Perry III, L. G., & Stoner, L. (2016). Transformational learning through study abroad: US students’ reflections on learning about sustainability in the South Pacific. Leisure Studies, 35(4), 389-405.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bhuiyan, M. A. H., Islam, R., Siwar, C., & Ismail, S. M. (2010). Educational tourism and forest conservation: Diversification for child education. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 7, 19-23.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bloom, B. S. (Ed.). (1956a). Taxonomy of education objectives Book 1-Cognitive domain. David McKay Company.

Bloom, B. S., Englehart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H. and Krathwohl, D.R. (1956b). Taxonomy of educational objectives, Handbook I: Cognitive domain, David McKay Company, New York.

Braun, V., and V. Clarke. (2006), “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology”, Qualitative Research in Psychology, Vol. 3 No. 2, pp. 77-101.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bretag, T., & van der Veen, R. (2017). ‘Pushing the boundaries’: Participant motivation and self-reported benefits of short-term international study tours. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 54(3), 175-183.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cacciattolo, M., & Aronson, G. (2023). The role of international study tours in cultivating ethnocultural empathy: preservice teacher standpoints. In Inclusion, equity, diversity, and social justice in education: A critical exploration of the sustainable development goals (pp. 261-275). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

Cardenas, D. A., Hudson, S., Meng, F., & Zhang, P. (2016). Understanding the benefits of school travel: An educator's perspective. Tourism Review International, 20(1), 29-39.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Casey, D., & Murphy, K. (2009). Issues in using methodological triangulation in research. Nurse researcher, 16(4).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chau, S. (2021). Antecedents and outcomes of educational travel in higher education. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 29, 100331.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Davis, R., Bolden-Tiller, O., & Gurung, N. (2016). 131 Experiential Learning for Tuskegee University Students: Study Tour of Agricultural Industries. Journal of Animal Science, 94(suppl_1), 64-64.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Denzin N. (1978). Sociological methods. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1996). Handbook of qualitative research. Journal of Leisure Research, 28(2), 132.

Dube, K. (2020). Tourism and sustainable development goals in the African context. International Journal of Economics and Finance Studies, 12(1), 88-102.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Eder, J., Smith, W. W., & Pitts, R. E. (2010). Exploring factors influencing student study abroad destination choice. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 10(3), 232-250.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fathi, M., Ghobakhloo, M., & Syberfeldt, A. (2019). An interpretive structural modeling of teamwork training in higher education. Education Sciences, 9(1), 16.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fisher, C., Hitchcock, L. I., Neyer, A., Moak, S. C., Moore, S., & Marsalis, S. (2022). Contextualizing the impact of faculty-led short-term study abroad on students’ global competence: Characteristics of effective programs. Journal of Global Awareness, 3(1), 3.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gaia, A. C. (2015). Short-term faculty-led study abroad programs enhance cultural exchange and self-awareness. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 14(1), 21-31.

Galloway, C., & Swiatek, L. (2020). International study tours and public relations pedagogy: Insights from a practice-oriented approach. Asia Pacific Public Relations Journal, 22.

Grabowski, S., Wearing, S., Lyons, K., Tarrant, M., & Landon, A. (2019). A rite of passage? Exploring youth transformation and global citizenry in the study abroad experience. In Tourism, Cosmopolitanism and Global Citizenship (pp. 13-23). Routledge.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Higgins, D., Smith, K., & Mirza, M. (2013). Entrepreneurial education: Reflexive approaches to entrepreneurial learning in practice. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 22(2), 135-160.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hol, A. (2016). Students as global citizens: lessons from the international study tour. International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering, 2640-2644.

Hussein, S. H., Kusairi, S., and Ismail, F. (2022), Hussein, S. H., Kusairi, S., & Ismail, F. (2022). Modelling the demand for educational tourism: do dynamic effect, university quality and competitor countries play a role?. Journal of Tourism Futures.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Iskhakova, M., & Bradly, A. (2022). Short-term study abroad research: A systematic review 2000-2019. Journal of Management Education, 46(2), 383-427.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Iskhakova, M., Bradly, A., & Ott, D. L. (2023). Meaningful short-term study abroad experiences: the role of destination in international educational tourism. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 23(4), 400-424.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jackqueline E. Uy, Verano, H. M., Verbo, C. L. B. and Irene, G. (2021). “Educational Tours as a Learning Tool to the Third Year Tourism Students of De La Salle University- Dasmarinas”, International Journal of Research in Tourism and Hospitality, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 32-45.

Keivani, Z., Safaniya, A., Pourkiyani, M., & Baqerian, M. (2021). Designing of Interpretive Structural Model of Sport Tourism Development in Iran. Sport Sciences Quarterly, 12(40), 101-117.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2017). Experiential learning theory as a guide for experiential educators in higher education. Experiential Learning & Teaching in Higher Education, 1(1), 7-44.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT press.

Krathwohl, D.R., Bloom, B.S. and Masia, B.B. (1964). “Taxonomy of educational objectives: The affective domain, Handbook II, David McKay Company, New York.

Lam, J., Ariffin, A. A. M., & Ahmad, A. H. (2011). Edutourism: Exploring the push-pull factors in selecting a university. International Journal of Business & Society, 12(1).

Lightfoot, E., & Lee, H. (2015). Professional international service learning as an international service learning opportunity appropriate for graduate or professional students. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 14(1), 32-41.

Maheshkar, C., & Sonwalkar, J. (2023). The pedagogy mix: teaching marketing effectively in business/management education. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mandal, A., and Deshmukh, S. G. (1994). “Vendor selection using interpretive structural modelling (ISM)”, International Journal of Operations and Production Management, Vol. 14 No.6, pp. 52-59.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mu, F., & Hatch, J. (2020). Managing a short international study trip: the case of China. International Journal of Educational Management, 34(2), 386-396.Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nayar, B. and Koul, S. (2020). “Blended learning in higher education: a transition to experiential classrooms”, International Journal of Educational Management, Vol. 34 No. 9, pp. 1357-1374.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Neff, P., & Apple, M. (2023). Short-term and long-term study abroad: The impact on language learners’ intercultural communication, L2 confidence, and sense of L2 self. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 44(7), 572-588.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

PIE news. (2020). “Educational travel to grow dramatically by 2020”.

Poletaeva, O., Moroz, N., & Lazareva, O. (2022). Educational Tourism as an Engine in Learning Foreign Languages. In IX International Scientific and Practical Conference “Current Problems of Social and Labour Relations"(ISPC-CPSLR 2021) (pp. 343-348). Atlantis Press.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rahul, M. (2020). Interpretive structural modelling.

Razavisousan, R., & Joshi, K. P. (2022). Building textual fuzzy interpretive structural modeling to analyze factors of student mobility based on user generated content. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(2), 100093.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Reilly, A. H., McGrath, M. A., & Reilly, K. (2016). Beyond ‘Innocents Abroad’: Reflecting on Sustainability Issues During International Study Trips+. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 11(4), 29-37.

Rikala, P., Braun, G., Järvinen, M., Stahre, J., & Hämäläinen, R. (2024). Understanding and measuring skill gaps in Industry 4.0—A review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 201, 123206.

Ritchie, B., Carr, N. and Cooper, C. (2003). “Managing Educational Tourism”, United Kingdom: Channel View Publications.

Rundshagen, V. (2017). “Educational tourism”, In L. L. Lowry (Ed.), The SAGE international Encyclopaedia of travel and tourism (pp. 406-408), “Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publication.

Saaty, T. L. (2008). Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. International journal of services sciences, 1(1), 83-98.

Schaupp, L. C., & Vitullo, E. A. (2020). Implementing experiential action learning in the MBA: use of an international consulting experience. International Journal of Educational Management, 34(3), 505-517.

Sima, V., Gheorghe, I. G., Subić, J., & Nancu, D. (2020). Influences of the industry 4.0 revolution on the human capital development and consumer behavior: A systematic review. Sustainability, 12(10), 4035.

Singh, A. (2022). “Methods of teaching in gurukul, Vedic Concepts”.

Sinha, P., & Mittal, R. (2021). Identification and Modelling of Religious Tourism Supply Chain Enablers in Post ـ Covid Era Using ISM. ASEAN Journal on Hospitality and Tourism, 19(3), 246.

Slantcheva-Durst, S., & Danowski, J. (2018). Effects of short-term international study trips on graduate students in higher education. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 55(2), 210-224.

Sohani, N. and Sohani, N. (2012).“Developing Interpretive Structural Model for Quality Framework in Higher Education: Indian Context”, Journal of Engineering, Science and Management Education, Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 495-501.

Sorooshian, S., Tavana, M. and Ribeiro-Navarrete,S. (2023). “From classical interpretive structural modeling to total interpretive structural modeling and beyond: A half-century of business research”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 157, 113642.

Stone, M. J., & Petrick, J. F. (2013). The educational benefits of travel experiences: A literature review. Journal of Travel Research, 52(6), 731-744.

Sushil (2012). “Interpreting the interpretive structural model”, Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 87-106.

Tamaki, K., & Ichinose, T. (2019). Sustainable tourism industry and rural revitalization based on experienced nature and culture tourism Case study of international regional tourism by SDGs linking urban and rural areas. Journal of Global Tourism Research, 4(2), 111-116.

Tang, C. F. (2021). “The threshold effects of educational tourism on economic growth”, Current Issues in Tourism, Vol. 24 No. 1, pp. 33-48.

Teoh, M. W., Wang, Y., and Kwek, A. (2021). “Conceptualising co-created transformative tourism experiences: A systematic narrative review”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Vol. 47, pp. 176-189.

Tovar, L. A., & Misischia, C. (2018). Experiential Learning: Transformation and Discovery through Travel Study Programs. Research in Higher Education Journal, 35.

Trowler, V. (2010), “Student Engagement Literature Review. York: The Higher Education.

Truong, T.T., Laura, R.S., and Shaw, K. (2018), “The Importance of Developing Soft Skill Sets for the Employability of Business Graduates in Vietnam: A Field Study on Selected Business Employers”, Journal of education and culture, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 32-45.

Tucker, M., & Weaver, D. (2013). A longitudinal study of student outcomes from participation in an international study tour: Some preliminary findings. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 10(2).

Velin, L., Van Daalen, K., Guinto, R., van Wees, S. H., & Saha, S. (2022). Global health educational trips: ethical, equitable, environmental?. BMJ Global Health, 7(4), e008497.

Voleva, I. (2020). “Origin and characteristics of educational tourism”, Economics and Management, Vol. XVІI, pp. 185-192.

Warfield, J. N. (1974). Developing interconnection matrices in structural modeling. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, (1), 81-87.

Wee, D. (2019). Generation Z talking: Transformative experience in educational travel. Journal of Tourism Futures, 5(2), 157-167.

World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) (2019).“UNWTO Tourism Definitions”, Madrid, Spain: World Tourism Organization (UNWTO).

Wurdinger, S. D., & Carlson, J. A. (2009). Teaching for experiential learning: Five approaches that work. R&L Education.

Xu, J., & Ho, P. S. (2024). Whether educational tourism can help destination marketing? An investigation of college students’ study tour experiences, destination associations and revisit intentions. Tourism Recreation Research, 49(1), 131-146.

Received: 01-May-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-14914; Editor assigned: 02-May-2024, PreQC No. AMSJ-24-14914(PQ); Reviewed: 26-Jul-2024, QC No. AMSJ-24-14914; Revised: 06-Aug-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-14914(R); Published: 11-Sep-2024