Research Article: 2019 Vol: 23 Issue: 4

Effectiveness of the local economic Development strategy of Emakhazeni Local municipality, South Africa

Bulelwa Maphela, University of Johannesburg

Abstract

Local economic development (LED) is the vehicle that local government uses to shape the future of its communities, simultaneously fighting poverty and inequality. The National Development Plan (NDP) 2030, from which LED is derived as an overarching plan intended to warrant that by 2030 South Africa’s economy could create employment opportunities for its citizens (National Planning Commission, 2011). The study intends to understand the effectiveness of the strategic approach Emakhazeni Local Municipality (ELM) has adopted by examining whether there is a comprehensive, well-structured and integrated approach towards LED. It, further, examined whether there were obstacles within the ELM strategic objectives vision. The study found that the local economy of ELM is highly influenced by frameworks and policies designed by national government. Meyer (2014), Moyo & Mamobolo (2014); Khambule & Mtapuri (2018) assert that legislation, policies and frameworks in South Africa stem from a pro-poor ideology. Pro-poor policies target poor people and are intended to reduce poverty. They argue that the pro-poor strategic approach does not always deliver the required results for LED. The study recommends that the municipality implement a strategic management and the application of a systems model to ensure that inputs are employed effectively to achieve required outputs. Furthermore, collaboration by regional and district localities should be emphasised to achieve effective LED. Lastly, a theoretical model that there are systems that can be adopted to achieve the required LED objective by ELM.

Keyword

Local Economic Development, Strategy, Systems Thinking, Soft Systems Methodology.

Introduction

Local Economic Development is a concept that has been asserted by legislation since the initial stages of transformation in South Africa. The Constitution of South Africa, the White Paper on Local Government and Section 152 of the Municipality Systems Act 32, 2000 obligates the promotion of LED (Masuku & Selepe, 2016). The National Development Plan 2030 is the overarching strategic framework for South Africa. It was created to charter a new path for the country with an objective of eliminating poverty and minimising inequality (Manual, 2012). The National Framework for Local Economic Development (NFLED) is a guideline that seeks to clearly define the scope of LED and also tool that proposes strategic approaches municipalities could apply in the implementation of LED (CoGTA, 2016). The NFLED (2017) defines LED “…as the process by which public, business and non-governmental sector partner’s work collectively to create better conditions for economic growth and employment generation with the objective of building up the economic capacity of a local area to improve its economic future and the quality of life for all”. Both the NDP and NFLED set the tone for the overall tactical framework for economic and social development (Koma, 2012). The 1996 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa asserted that, local government is no longer expected to render basic services, but also to serve as an agent of development. Numerous challenges relating to slow economic growth and development of local economies, resulting in unemployment, poverty, poor service delivery, violent conflicts (civil unrests and labour disputes), billing crises, as well as many other forms of political decay (Meirotti & Masterson, 2018). Emakhazeni Local Municipality is challenged by high unemployment, poverty and inequality. These challenges indicate that local governments need to intensify their efforts towards the understanding of LED and its situational discourse. According to Aurangzeb & Asif (2013), an economy characterised by high unemployment rate means there is underutilisation of its human capital and that translates to underdevelopment of a local economy.

Thus the study seeks to study and understand systems employed in ELM LED strategy, with an aim of understanding the current strategy. It is anticipated that a new situational strategy may bringing about change in addressing social and economic possibilities. A qualitative content analysis approach was used to understand the effectiveness of the ELM current strategy on local developmental issues. The analysis was conducted from a soft systems methodology concept to unpack the interplay of strategic management, legislation and environment of ELM. To map out the spectrum behind ELM strategy, legislation, policies and frameworks perspective from the three government spheres were analysed using qualitative content analysis. Legislation, policies and frameworks entail information translated as input yielding output that encourages growth and aims to bring about change (Bodhanya, 2017). It gave insight into their influence on the strategic approach ELM employees towards LED. It further shed light on whether it contributed to or counteracted the ELM LED strategy to create jobs, attract new business and achieve local economic stability. The soft system methodology was further used to support learning and improve efforts to create outputs that would enhance strategy effectiveness in promoting local economic growth.

Literature Review

Local Economic Development Strategy for Emakhazeni Local Municipality

The National Framework for Local Economic Development gives an interpretation of what LED in any given municipality is and the guidelines thereof. As a programme, LED has core policy pillars that have been designed to enhance economic potential of local government (CoGTA, 2016). The interdependence of legislation, policy and stakeholders with diverse perceptions and partially conflicting views has meant that, ELM needs to concentrate on a system that delivers outputs that could lead to fresh inputs to create a sustainable operational system.

Local Economic Development in the SA situation is concerned with micro-economics, recognising and utilising local resources to generate sustainable socio-economic development in local areas and determining how decisions are made based on the allocation of limited resources at local level (Wyngaard, 2006 & Meyer, 2014). The planning and execution of LED takes place at local government according to the White Paper on Local Government (WPLG) (Republic of South Africa, 1998). The WPLG states the functions and roles of local government as being centred on developmental local government (Khambule, 2018). The strategic approach of economic development in South Africa is constituted in the Constitution (Republic of South Africa, 1996). It is defined by the country’s core strategy, the NDP, which a municipality’s IDP should explicitly articulate as a form of commitment to its local citizens and the country (de Kluyver & Pearce, 2015).

Meyer (2014), Moyo & Mamobolo (2014); Khambule (2018) have argued that legislation, policies and frameworks in South Africa stem from a pro-poor discourse. The propoor policies are intended at assisting the pockets of the society that lives below the poverty line to be able to sustain them through an economic activity. Meyer (2014) argues that the pro-poor discourse does not always deliver the required results for LED. The main constraints in delivering results in pro-poor implementation is poor analysis of local economies, unsustainable community projects, lack of capacity and lack of resources (Meyer, 2014). The pro-poor policies stem from the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), which was the first development plan that South Africa adopted (Soudien et al., 2019). It was a policy created to address the inequality, poverty and unemployment the country was experiencing at during the transformation era (Moyo & Mamobolo, 2014). Followed by the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) approach which was intended to rebuild the economy to achieve the goals of the RDP (Moyo & Mamobolo, 2014). GEAR, introduced a neo-liberalism ideology which emphasised privatisation (Breakfast, 2015). Then came the Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative for South Africa (ASGISA) which was concerned with the high levels of poverty and unemployment. Finally, the NDP which currently stands as the overarching framework that will expand the assets and proficiencies of the poor was put in place.

The approach that government adopts towards development planning has a critical component in the development of a strategy by local government towards LED (Karriem & Hoskins, 2016). The pro-poor approach was centred around focusing on the poor, while the neoliberal approach focused on formal business and industrial development. While there is criticism about each school of thought, their influence has impacted the approach regarding the implementation of LED. This includes the change in leadership, thwarted development plans, and local governments not being given ample time to fully contextualise and synchronise the plans in their context (Kondlo & Maserumule, 2010).

Strategic plan for LED can be used to strengthen the local economic capacity of an area, improve the investment climate, and increase the productivity and competitiveness of local businesses, entrepreneurs and workers (Peria, 2016). However, understanding whether a strategy is effective encompasses the ability of the strategy unpacked in a form of a developmental model being (de Kluyver & Pearce, 2015). It also includes whether it permits a clear consideration of the architecture of its respective components and its relationship to its environment, which is constantly changing (de Kluyver Pearce, 2015). Describing a strategy as creating an enabling environment for LED suggests institutional systems and processes that support the development of local economic activities and work with social complexity (Reynolds & Holwell, 2010).

Traditional Analysis and System’s Thinking

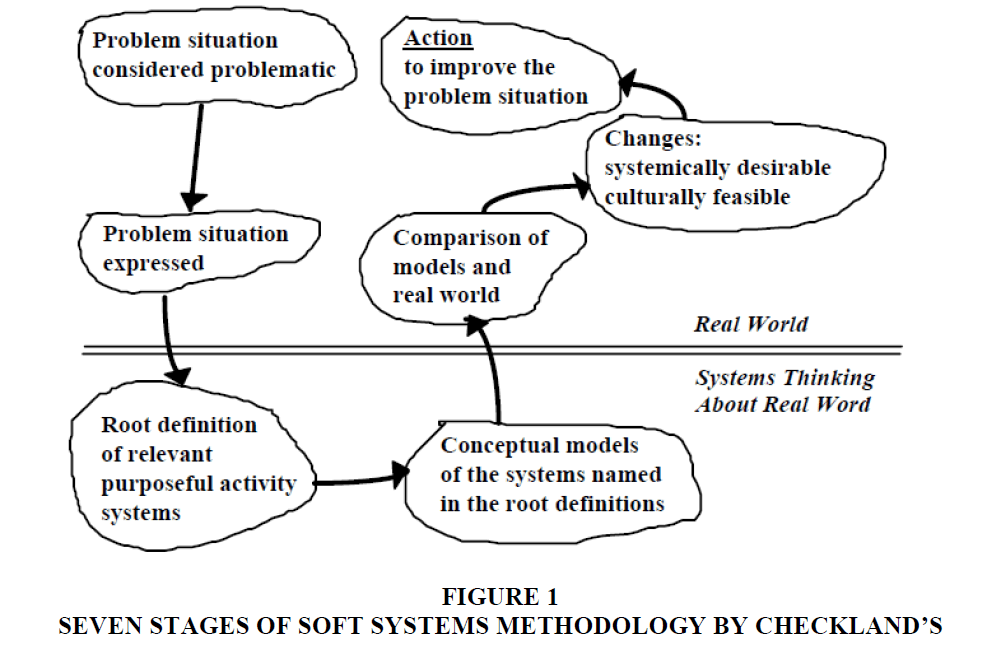

Systems thinking is unlike the traditional form of analysis (Carey et al., 2015). The difference is that traditional analysis is focused on separating the issues into individual pieces. According to the authors, systems approach uses qualitative methodology or action based approach. Soft Systems thinking methodology is focused on how things being studied connect with one another. It seeks to dig deeper, understand multiple perspectives and raise the level of thinking, and to determine whether it is used in a corporate context or stakeholder engagement. (Carey et al., 2015). System thinking has five models that deal with understanding interrelationships, dealing with different perspectives and addressing power relations in relation to systems intervention in different ways (Reynolds & Holwell, 2010). The five models are Systems Dynamics, Viable System Model (VSM), Strategic Options Development and Analysis (SODA), Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) and Critical Systems Heuristics (CSH). According to Reynolds and Holwell (2010), selecting the best method should be based on a rich interaction between the contextual situation, practitioner community and methodology of each of the selected methods. The Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) has been used in this study as model to unpack the interplay of strategic management on legislation and environment at ELM. The SSM approach, developed by Peter Checkland & John Poulter through action research over a period of 30 years, was selected to unpack the complexity within ELM, which arises from the interaction and interdependency of legislation, policy, governance and stakeholders that have diverse perception and partially conflicting views (Hildbrand & Bodhanya, 2014). The Soft Systems Model facilitates a holistic understanding of problem situations, supports learning and improvements, which may assist with examining the effectiveness and sustainability of ELM LED strategy (Hildbrand & Bodhanya, 2014). The Soft Systems Model has seven stages of which some stages address the ‘real world’ and others the conceptual world (Williams, 2005).

The first four stages (Figure 1) Adapted from: (Gasson, 1994) of the conventional seven stages were used to aid inquiry of the problem context and the human activity system (something that people do or cause to happen). The first stage assisted in identifying factors that hinder ELM from achieving its strategic objectives towards a sustainable LED. The second stage narrowed down the findings in the first stage using the Root Definition analysis. In the third stage the CATWOE analysis was utilised to logically reason what ELM would have to do in order to comply with the definition (Donaldson & Walsh, 2015). Business Change Academy (2017) unpacks CATWOE as one of the many techniques used to identify what an undertaking will be trying to achieve, what the problem areas are and how stakeholder perspectives affects people involved in the process of development and or enrichment. The findings that emanated from the CATWOE allowed for the development of the conceptual model, which is the fourth stage. The conceptual model provided detailed step-by-step-activities that need to be in place to achieve transformation (Gasson, 1994). The application of these stages facilitated uncovering the farreaching complexities that exist within ELM.

Situational Analysis using Soft Systems Methodology

The first stage, illustrated through a rich picture which was drafted using content analysis of the ELM IDP, revealed that national policy and changes in national policy objectives determined the development strategy. This top-down approach has created a situation where ELM finds itself implementing programmes regardless of need or buy-in from the community (Chaisson, 2018). This is evident in the ELM IDP which had adopted the Mpumalanga Vision 2030, the Mpumalanga Economic Growth Path, the National Development Plan, the Medium- Term Strategic Framework, and the 12 outcomes within which to frame public service delivery priorities. This approach has been criticised by Matland (1995), who states that it has an exclusive emphasis on the statute framers as key actors. He argues that local service delivery agents have the required expertise and the knowledge of the actual problems and are therefore in a better position to propose solutions (Matland, 1995). Meaning, the same delivery agents would have far more knowledge in recognising and utilising local resources to generate sustainable local economic development in local areas. They would also be able to determine how decisions are made based on the allocation of limited resources at within their local areas (Wyngaard, 2006 & Meyer, 2014).

Further analyses conducted in the second stage revealed that there was a soft issue relates to co-ordination. According to Koma (2012), there is an ineffective intergovernmental coordination and communication across the national, provincial and local spheres of government (Koma, 2014). This challenge is prevalent in rural municipalities such as ELM. To build up its economic capacity, ELM is required to align with national and provincial governments because some responsibilities are concurrent. Examples of concurrent responsibilities are electricity, water, and infrastructure (Ramodula, 2014).

It is important that appropriate coordination and alignment be warranted during the IDP and LED planning process (Koma, 2012). This is also prescribed in S104 (1) of the Constitution which prescribes the three spheres of government as distinctive, interdependent and interrelated. In this context local government does not exist on its own. The principle of co-operative governance underpins intergovernmental relations (Cameron & Quinn, 1999:2). Therefore, intentional action is required by all government spheres, through collaboration, to achieve LED.

The third stage was an examination of actions required to take place to describe what the actors need to do in order to achieve transformation in ELM to achieve an effective LED strategy (Gasson, 1994). The activities are as follows:

1. Goal-setting – this is to determine the aspiration the municipality would like to achieve or accomplish in the mid-term or long-term future.

2. Analysis – this is to assess the municipality’s competence and capabilities and its internal and external environments.

3. Strategy formulation – according to Ehlers, et al. (2010), strategies can be described as a comprehensive general approach that guide an organisation’s major actions. The choice of the strategy by an organisation could be based on competitive advantage, specifically regarding cost, leadership, differentiation or focus (generic strategies) or coordinating efforts towards the attainment of long-term goals (Ehlers, et al., 2010).

4. Strategy Implementation – the implementation of a strategy requires commitment, hard work and innovation (McShane & van Glinow, 2005). Creating measurable objectives – objectives are more achievable when they state clearly what is to be accomplished, when it is to be accomplished and how the accomplishment is to be measured (McShane & van Glinow, 2005).

5. Strategy monitoring – assignments or projects that need to be done if the strategy is to be accomplished (Johnson, 1979).

The fourth stage considered desirable and feasible changes. These would include ELM having a holistic and systems based strategic approach towards LED, which is not restricted by statutes and considers the significance of its stakeholders.

Though SSM is an appropriate methodology for comprehending and working with social complexity, it has been criticised for being radical when compared to other methods when dealing in complex problem context (Reynolds & Holwell 2010). SSM has been criticised for having unrealistic expectation because the process requires extremely high levels of communication skills and political skills on the part of the facilitators/analyst and a high level of commitment from stakeholders (Gasson, 1994). Should this method be applied at ELM functionality, one could deduce from lack of participation during IDP consultation that there would be high levels on the lack of participation from stakeholders. This is caused by ELM systems not having appropriate mechanisms and procedures to encourage its local community to participate in the IDP consultation and affairs of the municipality (Molaba, 2016). This challenge might result in the programme failing or municipality not meeting its community expectations. This further contributes to the challenges of CATWOE as stated earlier on.

Research Methodology And Design

The study adopted a qualitative content analysis research methodology. This method was selected due to the research being focused on the analyses of legislation, policies and frameworks to understand how they impacted on ELM strategic approach towards LED. The research design followed a qualitative research strategy, because it …begins with assumptions, a worldview, the possible use of a theoretical lens, and the study of research problems inquiring into the meaning individuals or groups ascribe to a social or human problem (Creswell, 2013). It further allowed for the interpretation of literature through legislation, policy and frameworks hence the research methodology used are qualitative content analysis. Content analysis as defined by Downe-Walbot (1992) is a research method that provides a systematic and objective means to make valid inferences from verbal, visual and written data in order to describe and quantify specific phenomena. Furthermore, the method applied within the qualitative content analyses context is the directed method which uses existing theory by identifying key concepts or variables as initial coding categories (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). The identified key concept in this study is a comprehensive, well-structured LED strategy should enhance the unique set of local conditions to its full potential whilst contributing to macro-economic development. Systems thinking model was applied as a coding process. The coding process use existing legislation, frameworks and policies to offer either support to existing text or to offer improvements that could be implemented to ensure that strategic decisions were drawn from the best available alternatives. In this case the content analysis approach required collection of secondary data. This mainly included published data that was already available from various government publications and those of subsidiary organisations, books, magazines and newspapers. The overall approach and analysis assisted in meeting the research objectives and responding to the research questions of the research under review.

Findings

The findings stem from an interpretation of data collected through content analysis associated with purpose, design and implementation of a strategy. The soft systems methodology was not used in its totality but it was concentrated on the aspect that examined whether the ELM strategic approach could improve the potential for local economic growth, based on its comprehensives, structure and interestedness (Gasson, 1994). The degree in variation illustrated through the rich picture which is the first stage of the SSM model, revealed that national policy and changes in national policy objectives determined the development trajectory. These policies create barriers responsible for influencing the implementation of the LED, barriers which are political, staffing, financial resources, skills, direction, socio-economic status quo and coordination (Koma, 2012). Furthermore, national policies such as the NDP, NFLED, and Medium-Term Strategic Framework 2014-2019 employ a top down approach which impact on strategic management at local government. It was argued that the top-down approach had created a situation where ELM found itself implementing programmes regardless of the need for or buyin from the community or by local agents (Chaisson, 2018).

Defining the problem situation by capturing a view from legislative perspective uncovered that, ELM is not align with national and provincial governments on concurrent responsibilities, examples of concurrent responsibilities are water, electricity, and infrastructure (Ramodula, 2014). Evidence of this is found in the ELM Annual Report (2012, 2013), which describes ELM as being inconsistent in terms of its objectives, key performance indicators and key performance targets, as prescribed in its Integrated Development Plan.

Recommendations And Conclusion

The strategic management of executing an LED plan that is effective is a challenge for ELM. The challenge includes the top-down approach created by policies and frameworks, such as the NDP, NFLED, and district municipality’s concurrent responsibilities not being aligned. In order to improve the effectiveness of the strategic approach by ELM, it is therefore recommended that an intentional systems approach is implemented which includes, three-way communication between government spheres needs to be improved by ensuring that no sphere makes legally binding decisions that affect other spheres without consultation. These spheres of government need to concentrate on joint planning, fostering friendly relations, and anticipation and resolution of conflict emanating from processes (Mdliva, 2012). It is important that appropriate co-ordination and alignment be warranted during the IDP and LED planning process (Koma, 2012). This will ensure that the vision and mission, and the long-term development planning of the municipality results in external and internal transformation. Furthermore, a detailed intervention and monitoring and evaluation process is implemented. This will ensure that ELM concerns itself with a strategic approach that delivers guidance on what it wants to do, give the opportunities of its environment; what it can do, given the resources at its disposal. The personal values and aspirations of key decision-makers, and the ethical and legal context in which it is operating need to be considered (Porter, 2015).

These recommendations are made to assist ELM in attaining achievable output and to create shared value between internal and external stakeholders.

References

- Carey, G., Malbon, E., & Carey, N., (2015). Systems science and systems thinking for public health: A systematic review of the field. BMJ Open 2015.

- Aurangzeb, D., & Asif, K. (2013). Factors effecting unemployment: A cross country analysis. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3(1), 219-2030.

- Bodhanya, S. (2017). Systems thinking, regional and local economic development. Large Scale Systematic Change. University of Johannesburg.

- Breakfast, N. (2015). The effect of macro-economic policies on sustainable development in South Africa: 1994-2014. SAIPA, 50(4), 756-774.

- Cameron, K.S., & Quinn, R.E. (1999). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Creswell, J.W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles: Sage.

- De Kluyver, C.A., & Pearce, J.A. (2015). Strategic management: an executive perspective.

- Downe-Wambolt, B. (1992). Content analysis: method, applications and issues. Health Care for Women International, 13: 313-321. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2019. Introduction to systems dynamics. Model-based policy formulation models for national development planning (T21).

- Ehlers, T., Lazenby, K., CronjeŽ, S., & Maritz, R. (2010). Strategic management: southern African concepts and cases. Van Schaik: Pretoria.

- Fabus, M., Dubrovina, N., Guryanova, L., Chernova, N., Zyma, O. (2019). Strengthening financial decentralization: Driver or risk factor for sustainable socio-economic development of territories. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 7(2), 875-890.

- Gasson, S. 1994. The use of soft systems methodology (SSM) as a tool for investigation.

- Hildbrand, S., & Bodhanya, S. (2014). Applying SSM to explore the complexity in a multi-stakeholder setting. Journal of Contemporary Management, (11).

- Hsieh, H., & Shannon, S. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288.

- Johnson, G. (1979). Managing strategic change: strategy, culture, and action. Long Range Planning, 57(2).

- Karriem, A., & Hoskins, J. (2016). From the RDP to the NDP: A critical appraisal of the developmental state, land reform, and rural development in South Africa. Politikon. 1-19.

- Khambule, I., & Mtapuri, O. (2018). Interrogating the institutional capacity of local government to support local economic development agencies in KwaZulu-Natal Province of South Africa. African Journal of Public Affairs, 1(25).

- Koma, S.B. (2012). Local economic development in South Africa. Africa Journal of Public Affairs, 5(3), 25-140. School of Public Management and Administration, University of Pretoria.

- Koma, S.B. (2014). Developmental local government with reference to the implementation of local economic development policy. Doctorate in Public Administration. Unpublished Dissertation. University of Pretoria: Pretoria.

- Kondlo, K., & Maserumule, M.H. (2010). The Zuma Administration Critical Challenges. Human Sciences Research Council Press.

- Kovaleva., Valentina, D., Lilia, F.S., Zarema Ruslanovna, K., Mikhail Gennadevich, R., & Viktoriya, I. (2018). Eurasian Economic Integration: Problems and Prospects. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 17(4), 1-8.

- Larionova, Nina I., Tatyana V., Yalyalieva., & Dmitry, L., & Napolskikh. (2018). Economic Development Of Russian Regions On The Basis Of Innovative Clusters. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 17(4), 1-5.

- Manual, T. (2012). Speech: National Development Plan 2030.

- Masuku, M.M., & Selepe, B.M. (2016). The implementation of Local Economic Development initiatives towards poverty alleviation in Big 5 False Bay Local Municipality. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 5(4).

- Matland, R.E. (1995). Synthesizing the implementation literature: The Ambiguity conflict model of policy implementation?, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 5(2), 145.

- McShane, S.L., & van Glinow, M. (2005). Organisational behavior-Emerging realities for the workplace revolution. (3rd Ed). McGraw-Hill: Boston.

- Mdliva, M.E. (2012). Co-operative governance and intergovernmental relations in South Africa: a case study of the Eastern Cape. Dissertation. Graduate School of Business and Leadership. UNISA.

- Meyer, D.F. (2014). Local economic development (led), challenges and solutions: the case of the northern Free State Region, South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(16).

- Meirotti, M., & Masterson, G. (2018). State capture in Africa: Old threats, new packaging. EISA. Richmond, Aucklandpark.

- Molaba, G.E. (2016). Community participation in Integrated Development Planning if the Lepelle-Nkumpi Local Municipality. Dissertation. University of South Africa.

- Moyo, T., & Mamobolo, M. (2014). The National Development Plan (NDP): A Comparative Analysis with the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) Programme and the Accelerated and Shared-Growth Initiative (ASGISA). Journal of Public Administration 4(3), 946-959.

- Naushad, M., Faridi, M.R., & Malik, S.A. (2018). Economic development of community by entrepreneurship: An investigation of the entrepreneurial intent and the institutional support to the local community in Al-Kharj region. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 5(4), 899-913

- Orlova, L., Gagarinskaya, G., Gorbunova, Y., & Kalmykova, O. (2018). Start-ups in the field of social and economic development of the region: A cognitive model. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 5(4), 795-811.

- Pietrzak, M.B., Balcerzak, A.P., Gajdos, A., & Arendt, L. (2017). Entrepreneurial environment at regional level: The case of Polish path towards sustainable socio-economic development. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 5(2), 190-203.

- Porter, M.E., & Lee, T.H. (2015). Why Strategy Matters Now. The New England Journal of Medicine, 372(18), 1681-1684.

- Ramodula, T.M. (2014). Assessing the extent of the application of strategic thinking in Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality. Master of Commerce in Leadership Studies. Unpublished Dissertation. University of KwaZulu Natal.

- Reynolds, M., & Holwell S. (2010). Systems Approaches to Managing Change: A Practical Guide. Springer, London.

- Wyngaard, A.T. (2006). An introduction to economic development in the Western Cape. Department of Economic Development and Tourism.