Research Article: 2020 Vol: 23 Issue: 4

Effective Leadership Styles for Cooperative Banks in an Emerging Economy

Celani John Nyide, Durban University of Technology

Abstract

Co-operatives are seen as a growing tool to reduce poverty and unemployment. As such, they are the subject of government regulation in many parts of the world. However, a considerable number of co-operatives in emerging economies fail as economic enterprises and as self-help organisations beyond government support. They are unable to cope with modern economic realities due to poor administration, leadership and poor business practices. Studies are emphatic that the style of leadership has an influence on the survival of businesses. This study, therefore, investigated the leadership styles prevalent at a co-operative financial institution. This study used questionnaires as a research instrument to collect data from respondents. Questionnaires consisting test items were administered to 107 eligible participants who were selected using purposive sampling. A Kendall-Tau test was conducted to test the relationship between the leadership styles and their influence on the organisation’s performance. Findings from the primary research show that transformational leadership style is within the investigated co-operative. The results also show that there is a significant relationship between the transformational leadership style and its effectiveness in meeting job related needs. There is evidence that suggests that transformational leadership style is effective in ascertaining the investigated co-operative meets its organisational goals. This study contributes to the literature on the identification and evaluation of effective styles of leadership for cooperative banks in an emerging economy.

Keywords

Co-operatives, Co-operative Financial Institutions, Effective Leadership Styles, Emerging Economies, Performance.

Introduction

According to Clark et al. (2020), cooperatives are economic enterprises and self-help organizations that play a meaningful role in uplifting the socio-economic conditions of their members and their local communities. They are seen as a growing tool to reduce poverty and unemployment (Koz?owski, 2016). This view is supported by Clark et al. (2020) who point out that co-operatives are becoming actively involved in the process of poverty reduction. For this reason, governments are committed to promoting co-operatives in emerging economies. For example, the Co-operatives Bill (2005) reveals that the South African government is committed to providing a supportive legal environment to enable co-operatives to develop and flourish and ensure that international co-operative principles are recognised and implemented in the Republic of South Africa. According to Lecoutere (2017); Ghosh and Ansari (2018), co-operatives have been widely promoted as the ideal type of projects for women by international funding agencies, grassroots women’s movements, church-based organizations and governments. In most cases these co-operatives are formed for credit, preparation of handicrafts, weaving, animal rearing, poultry, preparation of condiments and other popular food items, and such other items (Lecoutere, 2017).

A co-operative as an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise (Dube, 2016). Co-operatives are based on the values of self-help, self-reliance, self-responsibility, democracy, equality, equity and solidarity. Dube (2016); Lecoutere (2017) assert that most co-operatives and group enterprises are started with unemployed people, often with low skills levels, and no prior business experience, in economically marginal areas. Under these circumstances, it is difficult for these entities to survive. Through its own efforts, co-operatives struggle to survive beyond a government support. As a result, most of the co-operatives perform poorly and end up being dysfunctional. Contributing to these challenges is the lack of leadership skills and poor internal governance (Oelofse & Van-der-Walt, 2016; Dube, 2016). Most co-operatives and group enterprises are started with unemployed people, often with low skills levels, and no prior business experience, in economically marginal areas (Phillip, 2003; Bibby and Shaw, 2005; Jovanovi? et al., 2017). The aim of this research is to investigate the leadership styles adopted by Co-operative Financial Institutions in South Africa, an emerging economy; and to determine the influence the leadership styles have on the enterprises’ economic performance.

Literature Review

Defining a Co-Operative Bank

A co-operative bank is a small financial institution compared to city banks and regional banks (Barros et al., 2009; Clark et al., 2020). It operates under the regulatory rules imposed on other banks and their clients have the same deposits protection scheme as large banks. This kind of financial institution focuses on the development of their local communities by supporting business activities of local small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Mushonga et al., 2018). Co-operative banks fall under saving and credit co-operatives. In savings and credit co-operatives, client/members invest personal savings or profits in a co-operative in order to enable others to borrow money for consumption or business spending. The key point is that members can access loans at a low rate of interest. In South Africa, some of these co-operatives are in a form of burial society and have started providing funeral insurance services to their members (Ramadiro et al., 2003; Nieman & Fouché, 2016). The co-operative banks are required to be registered in terms of the Co-operative Banks Act, No 40 of 2007.

According to Hajra (2002), the main distinctive characteristics of co-operative banks from other types of banks may be listed as follows:

1. The members are limited to the small and medium companies, and individuals living in a certain geographical area,

2. Borrowers are also limited to small and medium companies in its targeting area,

3. There is a loan limitation to one loan per customer,

4. There are membership limitations in a certain range: the number of workers per firm, and the amount of capital per member,

5. The management policy of the company must be decided in the general representatives’ meeting, with a system of one vote per member.

General Issues Affecting the Co-Operative Sector in Emerging Economies

Co-operatives, often survivalist enterprises are founded by people who are unemployed and who have few business skills. They face many challenges to becoming viable businesses. Even though co-operatives play a vital role in rural and urban economic and social development of the country, the sad thing is that few survive (Oelofse & Van-der-Walt, 2016; Dube, 2016). They are unable to cope with modern economic realities due to poor administration and leadership and poor business practices. Such challenges hinder on the profitability and hence survival of these entities. According to Jovanovi? et al., (2017), government is generally committed to providing a supportive legal environment to enable co-operatives to develop and flourish and ensure that international co-operative principles are recognised and implemented. The Co-operatives Bill (2005) further asserts the government’s commitment in ascertaining that co-operatives register and acquire a legal status separate from their members and facilitate the provision of targeted support for emerging co-operatives, particularly those owned by women and Black people. Regrettably though, Twalo (2016) highlights that in reality, it has proved extremely difficult for co-operatives to succeed and become sustainable in the South African context. The business must be viable in order to survive. Most co-operatives and group enterprises are started with unemployed people, often with low skills levels, and no prior business experience, in economically marginal areas (Oelofse & Van-der-Walt, 2016).

Issues Affecting the Co-Operative Banking Industry

Ghosh and Ansari (2018) reveal that the co-operative banking sector is faced with a challenge that pertains to irregularities which are a result of the way co-operative banks do their transactions and related to record keeping. The system of corporate governance in cooperative banks is much weaker than commercial banks (Kontolaimou and Tsekouras, 2010; Ahmed et al., 2016). The lack of corporate governance in some of these banks has been a matter of concern. There is severe lack of professionalization in cooperative banks both at the employee and at the board of director level. Banking operations in cooperative banks are conducted in an ad hoc manner and decisions are taken based on reasons other than normal business considerations or the spirit of cooperative movement (Jovanovi? et al., 2017). These challenges hinder the co-operatives from becoming viable businesses. These challenges include lack of leadership skills and poor internal governance (Phillip, 2003; Bibby and Shaw, 2005; Jovanovi? et al., 2017). That is why Satgar (2007) finds it necessary to “enhance the multi-class appeal of co-operatives and to ensure co-operatives are able to attract people with different kinds of skills”. The diversity of skills can ascertain a balance between operational, financial and administrative side of business in co-operatives (Dube, 2016).

Styles of Leadership and their Influence on the Performance of a Co-Operative Bank

Sultan et al., (2018) write that the type of style of leadership that is chosen for an organisation will have an impact on the development of the purpose and the implementation of the strategy. Nahum and Carmeli (2020) concur that the style of the leader is considered to be particularly important in achieving organizational goals. Popli and Rizvi (2016) reveal the following popular styles of leadership, viz., Laissez faire leadership style which is a passive style of leadership that is reflected by high levels of avoidance, indecisiveness and indifference.

Transactional leadership style where leaders view the leader-follower relationship as a process of exchange (Popli & Rizvi, 2016). The leader clarifies subordinates’ responsibilities, reward them for meeting objectives, and correct them for failing to meet objectives (Gemeda & Lee, 2020). This style is characterized by contingent reward and management by objectives (Popli & Rizvi, 2016; Gemeda & Lee, 2020). Contingent reward refers to transactional rewards and recognition for accomplishments for desired outcomes, whilst management by objectives refers to a behaviour that is concerned with standard setting, deviation monitoring, error searching, rule enforcement and a focus on mistakes (Swain et al., 2018).

Transformational leadership style which is described as guidance through individualized consideration, intellectual stimulation, inspirational motivation and idealized influence (Gemeda & Lee, 2020; Swain et al., 2018). Individualized consideration emphasizes personal attention, while intellectual stimulation encourages use of reasoning, rationality and evidence. Further, inspirational motivation is assumed to raise levels of optimism and enthusiasm, while idealized influence provides a vision and sense of mission.

It is interesting to note that Popli and Rizvi (2016) have categorised the aforementioned leadership styles into approaches that focus on people and relationships to achieve the common goal, and those that focus on the tasks to be accomplished. Examples of relationally focused leadership styles include transformational leadership which motivates others to do more than they originally intended and often more than they thought possible, individualized consideration, which focuses on understanding the needs of each follower and works continuously to get them to develop to their full potential. Transformational leaders use idealized influence, inspiration and motivation, intellectual stimulation and individualized consideration to achieve superior results (Simola et al., 2010). In contrast, task focused (non-relationally focused) leadership styles are primarily laissez-faire and transactional leadership styles. Laissez-faire styles are similar in that they are conceptualized as passive avoidance of issues, decision making and accountability. Transactional leadership emphasize the transaction or exchange that takes place among leaders, colleagues and followers to accomplish the work.

Leadership Style and Organisational Performance

Sultan et al. (2018) maintain that without effective leadership style, the probability that a firm can achieve superior or even satisfactory performance when confronting the challenges of the global economy will be greatly reduced. Nahum and Carmeli (2020) add that when organisations restore strategic control and allow the development of a critical mass of leaders, these leaders will be a source of above-average returns. The result will be wealth creation for the employees, customers, suppliers, and owners of entrepreneurial and established organisations. Organizations need to let their managers develop the skills and abilities required to exercise strategic leadership (Parker et al., 2017). This means that the management will be in a position to develop the skills necessary for the enhancement of the long-term viability and short-term financial stability of their organisations. It should be noted that leadership styles differ according to the business environment and that there are other variables influencing employee productivity (Sultan et al., 2018; Gemeda & Lee, 2020). This impact of different organizational approaches and cultures means that any theory of leadership should be evaluated in different organizational contexts if the results are to be generalized (Popli & Rizvi, 2016).

Parker et al. (2017) suggest that one of the key predictors of business success is effective leadership and that ineffective leadership often is a predictor of an organization’s failure. Therefore, it is important to all organizations that they understand the role of leadership and that they identify the styles of leadership most effective to their businesses. Whether the leader’s primary focus is on consideration or on initiating structure, there seems to be general agreement among researchers that the main function of leadership is to address the deficiencies that affect organizational production and detract from an organization’s climate and that are part of most job settings (Durowaiye et al., 2018). As a result of this process, a leader will be effective insofar as he or she can support the followers; can provide them with, as necessary, the guidance, ideas, constraints and pressure that may be missing from the organizations yet are essential to enhancing performance; and can minimize risks (Gemede & Lee, 2020). It seems, then, that flexibility in leadership style is a necessity if a high level of leadership effectiveness is desired and required by the situation.

Research Methodology

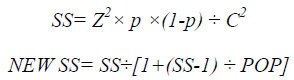

This study consisted of a literature review and a quantitative empirical study. The judgemental purposive sampling design was used to sample the participants. Participants that were involved in this study were members of a co-operative bank. 107 participants took part in this study which were from a co-cooperative bank that that has 147 members. The calculation of the sample size was based on a formula recommended by O’leary (2017):

Whereby SS = Sample Size, Z = Z value (1.96 for 95% confidence level), P = Standard of deviation (expressed as 0.5), C = Confidence Interval or Margin of error (expressed as 0.05) and POP = Population.

The respondents were asked closed-ended questions to provide a greater uniformity of responses (Spinelli et al., 2017). The questionnaire items contained response categories in a Likert scale format adopted from the multifactor leadership questionnaire (MLQ) test proposed by Bass and Avolio (1990). The MLQ test measures which levels of transformational, transactional and laissez-fair leadership styles a leader makes use of (Baek et al., 2018) and is one of the most validated methods used world-wide (Boamah & Tremblay, 2019). The questionnaire items contained response categories in a Likert scale format using a rating scale of 0 to 4 (where 0=Not at all, 1=Once in a while, 2=Sometimes, 3=Fairly often, 4=Frequently, if not always). These categories were then transformed into an ascending 5 point Likert scale where 0=Strongly Disagree (SD), 1=Disagree (D), 2=Neutral (N), 3=Agree (A) and 4=Strongly Agree (SA). The particular value of this format is the unambiguous ordinality of the response categories (Spinelli et al., 2017). The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to compile the descriptive statistics. To evaluate the reliability of the questionnaire, the Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha coefficient was established at 0.891 (See Table 1). This ascertains that internal consistencies of the scale items have been satisfied and that the questionnaire was reliable (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). The data can therefore be used confidently for analysis and interpretation (Bryman & Bell, 2015).

| Table 1 Reliability Statistics Using Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha | ||

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Cronbach’s Alpha Based on Standardized Items | Number of Items |

| 0.891 | 0.812 | 14 |

Discussion of Results

A summary of the responses to the 14 leadership styles questions is shown in the next tables. The entries under 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 for each of the variables are the counts of the responses.

As per Table 2, 51% of the respondents agreed that the leadership is clear on what their subordinates can expect to receive when performance goals are achieved, while 27% of the respondents were neutral about the leadership being clear on performance goal achievement and 22% disagreed. The mean of 2.44 is leaning equally towards neutral and agree. The 51% who feel that the leadership is clear on performance goal achievement could be those that have been recognised and rewarded for accomplishing the desired outcomes (Swain et al., 2018). The 22% that disagreed could be those that resent the leadership due to the fact that they fail to meet the objectives and as such they do not get any recognition and compensation for meeting the objectives. The 28% that is neutral could be those that have been partly meeting the objectives and the leadership has tried to correct them for failing to meet objectives.

| Table 2 Clear on Performance Goal Achievement | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Clear on performance goal achievement | 9% | 13% | 27% | 27% | 24% | 22% | 51% | 2.44 |

This test item in Table 3 is a characteristic of a laissez-fair leadership style. The majority of the respondents, at 49% disagreed that the leadership delays responding to urgent questions, 25% agreed with the statement while 26% remained neutral. The mean of 1.52 equally leans towards neutral and agree. The 49% of the respondents that disagreed that the leadership delays responding to urgent questions could be those that find the leadership proactive and systematic in responding to situations and problems. Those that are neutral at 26% and those that agree at 25% actually suggest that there seem to be lack of assertiveness by the leadership. Gipson et al. (2017) write that lack of assertiveness may be the case with women in organizations, who may face backlash effects for showing high levels of assertiveness but they also risk being seen as overly communal and weak.

| Table 3 Delays Responding to Urgent Questions | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Delays responding to urgent questions | 31% | 18% | 26% | 17% | 8% | 49% | 25% | 1.52 |

The statement in Table 4 is characteristic of a laissez- fair leadership style. The majority of the respondents at 57% disagreed that the leadership fails to interfere until problems are serious and 14% of the respondents were neutral while 29% agreed that the leadership fails to interfere until problems are serious. The mean of 1.54 leans weakly towards not at all but leans equally towards neutral and agree. These findings contrast Jovanovi? et al. (2017) who point out that co-operative banks’ transactions are often conducted in an ad hoc manner and decisions are taken based on reasons other than normal business considerations or the spirit of cooperative movement (Table 5).

| Table 4 Fails to Interfere | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Fails to interfere. | 31% | 26% | 14% | 16% | 13% | 57% | 29% | 1.54 |

| Table 5 Focuses on Mistakes | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Focuses attention on mistakes | 28% | 19% | 26% | 16% | 11% | 47% | 27% | 1.62 |

The majority of the respondents at 47% disagreed that the leadership focuses attention on mistakes. On the other hand, 27% of the respondents agreed and 26 % were neutral. The mean of 1.62 strongly leans towards neutral. Typical behaviours of transactional leadership style include standard setting, deviation monitoring, error searching, rule enforcement and a focus on mistakes (Parker et al., 2017). Even though 47% of the respondents disagreed that the leadership focuses on mistakes, the mean is indicative of the fact that sometimes the leadership focuses on mistakes and 27% of the respondents agreed while 26% was neutral. The respondents that disagreed could be due to the fact that they are able to meet the standards and objectives set by the leadership. Those that agreed and those that were neutral could suggest that the leadership is confrontational and enforces the rules when objectives. The general observation is that there is a slight element of a transactional leadership style in the investigated cooperative bank.

In Table 6 above, 49% of the respondents disagreed with the fact that the leadership avoids getting involved in important issues, 28% was neutral and 23% agreed. The mean of 1.49 leans weakly towards agree. The respondents that disagreed suggest that the leadership is actively involved in dealing with important issues (Table 7).

| Table 6 Avoids Getting Involved | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Avoids getting involved in important issues | 31% | 18% | 28% | 15% | 8% | 49% | 23% | 1.49 |

| Table 7 Absent When Needed | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Absent when needed | 37% | 12% | 19% | 21% | 11% | 49% | 32% | 1.56 |

The majority of the respondents at 49% disagreed that the leaders are absent when needed. On the other hand, 32% agree that the leaders are absent when they are needed while 19% remained neutral. The mean of 1.56 is leaning strongly towards neutral. Even though the majority at 49% disagreed that the leadership is absent when needed which suggest that the laissez-fair leadership style is not in use, it is worth noting that 32% find the leadership not visible in critical situations, while 19% is neutral. This implies that there is lack of organisational commitment.

As per Table 8, 43% of the respondents agree that the leadership avoids making decisions. 34% disagreed while 23% remained neutral. The mean of 1.96 leans strongly towards neutral. As the majority of respondents are in agreement with the statement, it shows that the leadership is passive according the results found in this table, hence a laissez-fair approach. This could be due to the fact that the leadership lacks business and technical skills that would equip them to make relevant decisions. This is congruent to the assertion made by Clark et al. (2020) that leadership in co-operatives is challenged due to poor administration, leadership and poor business practices, and lack of technical skills which involves more specialization and knowledge that would facilitate decision making.

| Table 8 Avoids Making Decisions | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Avoids making decisions | 27% | 7% | 23% | 29% | 14% | 34% | 43% | 1.96 |

Table 9 illustrates that the majority of the respondents of 64% agreed that the leadership specifies the importance of having a strong sense of purpose, 27% was neutral and only 9% disagreed. The mean of 2.78 strongly leans towards agree The 64% of respondents in agreement probably suggest that the leadership elevates subordinates’ levels of consciousness about the importance and value of specified and idealized goals. Simola et al. (2010) write that this a characteristic of transformational leadership in which leaders demonstrate vision and mission, and serve as role models to followers; inspirational motivation, characterized by the inspiration of a shared vision and team spirit directed toward achievement of group goals. Based on this find it can be concluded that the leadership at the investigated co-operative bank has an element of transformational leadership behaviour.

| Table 9 Strong Sense of Purpose | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Strong sense of purpose important | 1% | 8% | 27% | 40% | 24% | 9% | 64% | 2.78 |

In Table 10 it is found that 75% of the respondents agreed that the leadership at the investigated cooperative bank displays the sense of power and confidence, 8% of the respondents disagreed and 17% was neutral. The mean of 2.97 leans strongly towards agree This statement was intended to gauge if the leadership is displaying a transformational leadership approach. The general observation is that respondents feel that the leadership indeed shows the transformational leadership style behaviour. This statement was intended to gauge if the leadership is displaying a transformational leadership approach. The general observation is that respondents feel that the leadership indeed shows the transformational leadership style behaviour (Popli & Rizvi, 2016).

| Table 10 Sense of Power and Confidence | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Displays sense of power and confidence | 0% | 8% | 17% | 45% | 30% | 8% | 75% | 2.97 |

The data depicted in Table 11 shows that 74% of the respondents, which represents the majority, agreed that the leadership talks optimistically about the future, 3% disagreed and 23% were neutral. The mean of 3.02 leans strongly towards agree. This suggests that the leadership creates a vision for the future and invests a great effort into sharing that vision with the subordinates. Swain et al. (2018) states that transformational leaders at various levels of an organization provide followers with statements about future goals and the requisite actions needed to attain those goals. The conclusion from this finding is that the leadership at the investigated cooperative bank possesses the transformational leadership trait.

| Table 11 Optimistic about the Future | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Talks optimistically about the future | 0% | 3% | 23% | 42% | 32% | 3% | 74% | 3.02 |

According to the analysis in Table 12, 67% of the respondents agreed, 8% disagreed and 25% is neutral to the fact that the leadership instils pride in them as employees. The mean of 2.8 leans strongly towards agree. These results show that the employees find the leadership to be showing the characteristics of the transformational leadership style in their approach of leadership.

| Table 12 Installs Pride in Employees | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Installs pride in employees | 4% | 4% | 25% | 41% | 26% | 8% | 67% | 2.8 |

According the data found in Table 13, the majority of the respondents at 73% agreed that the leadership is helpful in developing their strengths. On the other hand, 6% was in disagreement and 21% was neutral. The mean of 3 reveals the agreement of the respondents. The majority that find the leadership helpful in developing their strengths could be those that find the leaders to be attuned to their emotional issues. Those that disagreed could be caused by the fact that they are frustrated by the leadership emotionally. This is supported by Rawat et al. (2019) who write that highly attuned emotional leaders are skilled at understanding and managing human emotion as an inevitable phenomenon in women corporate settings, and leveraging it as a source of energy and shaping influence on follower behaviour.

| Table 13 Helps in Developing Strengths | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Helps in developing strengths | 3% | 3% | 21% | 36% | 37% | 6% | 73% | 3 |

As per Table 14, 68% of the respondents agreed, 3 % disagreed and 29% was neutral to the fact that the leadership at the investigated cooperative bank expresses confidence that goals will be achieved. The mean of 2.93 strongly leans strongly towards agreed. As it is discussed in Table 11, a leader that is characterized by the inspiration of a shared vision and team spirit directed towards the achievement of group goals is a transformational leader. One can, therefore, conclude that the respondents find the leadership to be using a transformational approach which confirms findings by Gemeda & Lee (2020) and Swain et al. (2018).

| Table 14 Confident in Goal Achievement | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Expresses confidence in achieving goals | 1% | 2% | 29% | 39% | 29% | 3% | 68% | 2.93 |

The results reflected in Table 15 shows that 71% of the respondents agreed that their leaders express satisfaction when expectations are met. Only 10% disagreed while 19% was neutral. The mean of 2.85 leans strongly towards agree. As the majority of 71% of respondents that feel that leadership expresses satisfaction when expectations are met, could be due to the fact that the leadership has rewarded them for meeting the objectives, which is a transactional leadership style attribute.

| Table 15 Satisfaction When Expectations are Met | ||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | TD | TA | ||

| Test item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | ||

| Expresses satisfaction when expectations are met | 8% | 2% | 19% | 39% | 32% | 10% | 71% | 2.85 |

Research Findings

The first objective set out for this study was to determine the leadership style or styles adopted by the leadership of the investigated co-operative. 14 test items were used to establish the style of leadership used by the co-operative. The results of a test comparing the overall results of the means for the 3 styles, namely: laissez-faire, transactional and transformational leadership styles, produced the results shown in the Table 16 and Table 17 below.

| Table 16 Kruskal-Wallis Test | |||

| Ranks | |||

| Style | N | Mean Rank | |

| Mean | Laissez-faire | 6 | 3.50 |

| Transactional | 2 | 8.50 | |

| Transformational | 6 | 10.60 | |

| Total | 14 | ||

| Table 17 Test Statistics | |

| Mean | |

| Chi-Square | 9.415 |

| Df | 2 |

| Asymp. Sig. | 0.009 |

A Kruskal-Wallis test was used in this study to detect differences in locations among the population distributions based on independent random sampling. Since the p-value=0.009, there is a significant difference between the means for the 3 styles. The mean for the laissez-faire leadership style of 3.50 is significantly lower than that for the other two styles. This means that the respondents agree less with the laissez-faire style statements than with the statements concerning the other two leadership styles. Transformational leadership style, represented by a mean of 10.60, is found to be significantly dominant as per participants’ responses. The transactional leadership style was ranked second represented by a mean of 8.50. These results are in line with studies that have found that women tend to be rated as more transformational (Gipson et al., 017; Boamah & Tremblay, 2019). The study conducted by Jones and Jones (2017) also found that women were much more likely than men to use transformational leadership, motivating employees and peers to transform self-interest into organizational goals. Likewise, Rawat et al. (2019) concur that females engage in more transformational behaviour and that females who adopt a more transformational style may be perceived as being more effective than their transformational male counterparts.

Limitations

This study focused on a cooperative bank in a particular geographic area and the results can, therefore, neither be regarded to be representative of all cooperative banks in emerging economies.

Recommendations for Future Research

It is recommended that future research is done to investigate other possible contributing factors that contribute towards the failure of co-operatives’ survival as economic enterprises and as self-help organisations beyond government support. This research could be done in men owned co-operatives to establish the leadership style they use and its impact on the survival of their co-operative. A comparative study could also be done between rural co-operatives and urban co-operatives to examine if the results would show different leadership styles due to different geographical locations.

Conclusion

The study has contributed results and research approaches that could stimulate further research on the important issues that affect co-operatives and leadership. This study is significant to members of co-operatives and those who are aspiring to form co-operatives. The literature review and the empirical study revealed the leadership style that is effective in successfully managing a business. transformational leadership style is found to be effective in meeting organisational goals and has a positive significant impact on the performance of a cooperative bank.

References

- Ahmed, J.U., Nisha, N., & Rifat. A. (2016). The Dhaka mercantile co-operative bank limited: A case of Islamic Shari’ah banking in Bangladesh. International Journal of Financial Innovation in Banking, 1(2), 62–79.

- Baek, H., Byers, E.H., & Vito, G.F. (2018). Transformational leadership and organizational commitment in Korean police station: Test of second-order MLQ-6 S and OCQ. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 20(2), 155–170.

- Barros, C.P., Managi, S., & Matousek, R. (2009). Productivity growth and biased technological chance: Credit banks in Japan. Journal of International Financial Markets and Money, 19(2), 924-936.

- Bass, B.M., & Avolio, B.J. (1990). Transformational leadership development: Manual f or the multifactor leadership questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press.

- Bibby, G., & Saw, K.D. (2005). Making a difference: Co-operative solutions to global poverty. Retrieved from http://www.andrewbibby.com/pdfmaking%20a%20difference.pdf

- Boamah, S.A., & Tremblay, P. (2019). Examining the factor structure of the MLQ transactional and transformational leadership dimensions in nursing context. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 41(5), 743-761.

- Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2015). Business research methods. New York: Oxford university press.

- Clark, E., Mare, D.S., & Radi?, N. (2020). Cooperative banks: What do we know about competition and risk preferences? Journal of International Financial Markets, institutions & Money, 52(1), 90–101.

- Co-operative Bill. (2005). Retrieved from http://www.info.gov.za/view/downloadFileAction?id=66098

- Dube, H.N. (2016). Vulnerabilities of rural agricultural co-operatives in Kwazulu-Natal: A case study of Amajuba District, South Africa. M.Com. Dissertation. UKZN.

- Durowaiye, M.A., Erhun, W.O., & Osemene, K.P. (2018). Managerial and leadership styles of teaching hospital pharmacists in Nigeria. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 17(1), 34–46.

- Gemeda, H.K., & Lee, J. (2020). Leadership styles, work engagement and outcomes among information and communications technology professionals: A cross-national study. Heliyon, 6(1), 1–10.

- Ghosh, S., & Ansari, J. (2018). Board characteristics and financial performance: Evidence from Indian cooperative banks. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, 6(1), 86–93.

- Gipson, A.N., Pfaff, D.L., Mendelsohn, D.B., Catenacci, L.T., & Burke, W.W. (2017). Women and leadership: Selection, development, leadership style and performance. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 53(1), 32-65.

- Hajra, S. (2002). Deposit insurance for cooperative banks: Is there a road ahead? Economic and Political Weekly, 37(48), 4800–4806.

- Jones, E.L., & Jones, R.C. (2017). Leadership style and career success of women leaders in non-profit organizations. Advancing Women in Leadership, 37(1), 37–48.

- Jovanovi?, T., Arnold, C., & Voigt, K.I. (2017). Cooperative banks in need of transition: The influence of Basel III on the business model of German cooperative credit institutions. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, 5(1), 39–47.

- Kontolaimou, A., & Tsekouras, K. (2010). Are co-operatives the weakest link in European banking? A non-parametric metafrontier approach. Journal of Banking and Finance, 34(1), 1946–1957.

- Koz?owski, ?. (2016). Cooperative banks, the internet and market discipline. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, 4(2), 76–84.

- Lecoutere, E. (2017). The impact of agricultural co-operatives on women’s empowerment: Evidence from Uganda. Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management, 5(2), 14–27.

- Mushonga, M., Arun, T.G., & Marwa, N.W. (2018). Drivers, inhibitors and the future of co-operative financial institutions: A Delphi study on South African perspective. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 133(2), 254–268.

- Nahum, N., & Carmeli, A. (2020). Leadership style in a board of directors: Implications of involvement in the strategic decision?making process. Journal of Management and Governance, 24(1), 199–227.

- Nieman, G., & Fouché, K. (2016). Developing a regulatory framework for the financial, management performance and social reporting systems for co-operatives in developing countries: A case study of South Africa. Acta Commercii, 16(1), 1–7.

- Oelofse, R., & Va-der-Walt, J.L. (2016). The effect of support initiatives on the operations and performance of South African Worker Co-Operatives. Forum Empresarial, 21(1), 1–21.

- O’leary, Z. (2017). The essential guide to doing your research project. London: Sage Publications.

- Parker, B.A., Ellis, J.D., & Rogers, D. (2017). Leadership in Kansas agriculture: Examining organization CEOs’ styles and skills. Online Journal of Rural Research & Policy, 12(3), 1-11.

- Phillip, K. (2003). Co-operatives in South Africa: Their role in job creation and poverty reduction. Retrieved from http://www.sarpn.org/documents/d0000786/P872-Coops_October2003.pdf

- Popli, S., & Rizvi, I.A. (2016). Drivers of employee engagement: The role of leadership style. Global Business Review, 17(4), 965–979.

- Ramadiro, B., Mavundla, Z., & Seohatse, L. (2003). Research report: Youth participation in co-operatives in South Africa. Retrieved from http://ftp.org.za/coop_youth_participation.pdf

- Rawat, P.A., Rawat, S.K., Sheikh, A., & Kotwal, A. (2019). Women organization commitment: Role of the second career & their leadership styles. The Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 54(3), 458–470.

- Satgar, V. (2007). The state of the South African co-operative sector. Retrieved from http://www.copac.org.za/files/state%20of%coop%sector.pdf

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Simola, S.K., Barling, J., & Turner, N. (2010). Transformational leadership and leader moral orientation: Contrasting an ethic of justice and an ethic care. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(1), 179–188.

- Spinelli, S., Dinnella, C., Masi, C., Zoboli, G.P., Prescott, J., & Monteleone, E. (2017). Investigating preferred coffee consumption contexts using open-ended questions. Food Quality and Preference, 61(2), 63–73.

- Sultan, Y.A.S., Al-Shobaki, M.J., Abu-Naser, S.S., & El-Talla, S.A. (2018). The style of leadership and its role in determining the pattern of administrative communication in Universities- Islamic University of Gaza as a model. International Journal of Academic Management Science Research, 2(6), 26–42.

- Swain, A.K., Cao, Q.R., & Gardner, W.L. (2018). Six sigma success: Looking through authentic leadership and behavioural integrity theoretical lenses. Operations Research Perspectives, 2(1), 120–132.

- Twalo, T. (2016). Compromised success potential of South African co-operatives due to lack of credible data. Journal of Co-operative Studies, 49(3), 24–31.