Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 2

Effect of Institute and Lms Service Quality on Hei Brand Equity: A Qualitative Investigation

Rashmi Mishra, Oriental University, Indore

Rajendra Kumar Jain, Oriental University, Indore

Abhishek Mishra, Indian Institute of Management, Indore

Citation Information: Mishra, R., Jain, R.K., & Mishra, A. (2023). Effect of institute and lms service quality on hei brand equity: a qualitative investigation. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 27(2), 1-17.

Abstract

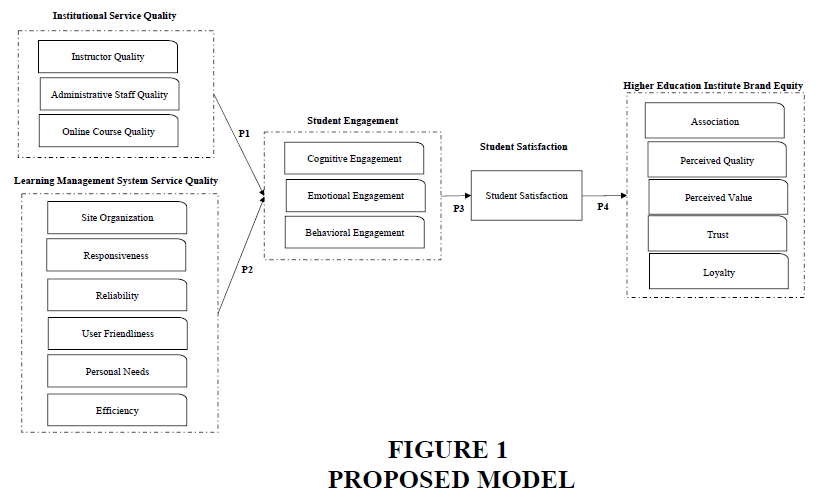

With the COVID-19 pandemic, many education institutions have shifted to the online mode of teaching. With the virus waning in most parts of the world, traditional institutes are attempting to balance online and offline pedagogical mechanisms to optimize their resources. The study aims to propose a conceptual model relating institutional and learning management system (LMS) service quality to higher education institute (HEI) brand equity. This work examines the existing literature on Service Quality (SERVQUAL) framework and its applications across various contexts, including higher education, and leverages it to propose a conceptual model, in conjunction with qualitative interviews, which explains the engagement and satisfaction of online students from the education services of such institutes. This work argues that two primary dimensions of service quality – institute and LMS – are important in driving student engagement, satisfaction, as well as the brand equity of a HEI. Through a systematic literature review and depth interviews, this work proposes instructor quality, administrative staff quality and online course quality as components of institute quality. Further, it proposes various aspects of the LMS, like site organization, responsiveness, reliability, user-friendliness, fulfilling personal needs, and efficiency, as factors that shape student learning experience and satisfaction.

Keywords

Information Systems, Experiential Learning, Student-Centred, Professional, Distance, Qualitative, Action-Research, Discourse Analysis, Satisfaction.

Introduction

Education is a crucial industry growing very fast globally in both primary and higher education sectors, leading to a rapid proliferation of higher education institutes (HEIs) both in the public and private sectors. However, an oversupply causes many HEIs to struggle with limited good-quality instructors and courses, resulting in poor admissions, and financial performance (AISHE, 2016; Yousaf et al., 2018). Hence, the HEIs need to understand the attributes to get them the best applicants. It is a well-known fact that the brand of a firm is the key driver to attracting more customers. Hence, it is important to examine the drivers of building higher education institute brand equity, which will enable it to get the best students. Additionally, there is a big change, due to the advent of COVID-19, and the traditional mode of teaching has shifted from offline to online mode through various Learning Management Systems (LMS) like Zoom, Google Meet, and Cisco Webex. The student experience of these HEIs is not only an outcome of the quality of instruction but also their perceived quality of the LMS platform that enables the instruction.

Service quality remains a seminal measure of the overall service efficacy and it is no different for education as a service. However, operationalizing service quality is a challenge (Parker, 2005). Quality in education may have unique meanings for various stakeholders such as students, instructors, staff, and the public-at-large, with students as the primary stakeholder given they are the primary service consumers (Chaney et al., 2009; Jung & Latchem, 2007). Many scholars in education propose service quality be driven primarily by faculty and course performance (Haimiti, Shan, & Deqing, 2014). Some others propose it as an effective support system for students to achieve positive academic outcomes (Shelton, 2011). However, given the impact of COVID-19, many traditional HEIs have migrated to online teaching modes and even launched online programmes for specific student groups, like working executives, through the adoption of a variety of LMS platforms.

In such a mode of delivery, besides the institutional factors, factors related to technology also determine the student’s learning quality. Multiple works identify the principles for developing HEI brand equity in the conventional teaching domain, yet none have explored HEI brand-building with the combination of institutional factors, like teachers, infrastructure, and technology factors, like the online education tool's performance (Whisman, 2009). Largely, the literature on conventional education settings and online education attributes determining student satisfaction has remained disjointed. This work aims to integrate the two streams of literature to propose a comprehensive model for student satisfaction and the institute's brand equity.

To fill the research gap, this work suggests how the combination of the institutes' service quality, as well as that of the LMS platform, jointly shapes the students' brand equity of the HEI. Through a detailed literature review followed by in-depth interviews with 25 students enrolled in such online programs by traditional higher education institutes, the study proposes the service quality of the institute, comprised of instructor quality, administrative staff quality, and online course quality, and the LMS service quality, comprised of site organization, responsiveness, reliability, user-friendliness, personal needs and efficiency, drive HEI brand equity through student satisfaction. The HEI brand equity is proposed to contain the perceived quality, perceived value, trust, and loyalty. This work aims to provide a conceptual model to explain the process of brand equity formation in a unique context where traditional HEIs are offering online courses due to the COVID-19 concerns.

Theoretical Background

Higher education literature examines multiple institutional attributes that are equivalent to the endorser characteristics, who in this case is endorsing the HEI brand. The consumption experiences of the institutional characteristics are likely to be a key determinant of enhancing students' responses to the HEI brand (Sujchaphong et al., 2015). Yuan et al. (2016) argue that students' interface with various elements of the institute builds the notion of student experiences with the institute and shapes their perception of the institute itself. For example, instructors at HEI instructors are considered celebrities (e.g., Sebastian and Bristow, 2008), and the student experiences with such instructors build the collegiate experience and HEI's brand equity (Moore et al., 2018). While some studies examine the image of the HEI or attributes of the instructor and other institutional characteristics that affect their performance (e.g., Chapleo, 2015; Yuan et al., 2016), there is limited discussion on a holistic application of the institute and its human and technology facets on its brand equity in an online education context.

Service Quality

The concept of service quality has multiple conceptualizations and many works have attempted to understand this concept for many years. First, Parasuraman, Zeithaml and Berry (1985) propose the importance of this concept for various service firms and proposed three primary characteristics: intangibility, heterogeneity, perishability, and inseparability. According to them, service quality depends on the customer’s expectations before consuming the services. Later, Parasuraman et al. (1994) proposed the SERVQUAL scale to measure five dimensions of service quality: reliability, assurance, trust, responsiveness, and tangibility. SERVQUAL has been critiqued for its low generalizability because it focuses on measuring utilitarian quality based only on expectation (Kang and James, 2004). Thus, it is argued that a better definition and measure of perceived service quality was needed, and such measures should be contextual to a service, like higher education. There is also limited consensus on the relationship between service quality and satisfaction. Existing literature suggests that either satisfaction precedes service quality, as satisfaction through different service transactions creates an overall assessment of the service quality, or service quality precedes satisfaction, as satisfaction is a more universal phenomenon that encapsulates service quality (González, Comesaña, and Brea, 2006). More clarity on this is needed.

Service Quality in Higher Education

There is a rare application of the concept of service quality and its implications on customer satisfaction and loyalty in the higher education sector. The past few years have seen many changes in the domain of higher education (Dennis et al., 2016). These include the internationalization of education (Harvey and Williams, 2010), an increase in private HEIs (Halai, 2013) and autonomy for government universities (Quinn et al., 2009). The professionalization of higher education, accompanied by an increase in cost, has created the perception that higher education is now a professional service (East et al., 2014). Further, Eagle and Brennan (2007) justify why students should be treated as consumers and so, marketing models, including SERVQUAL, can be applied in higher education. As per the literature on service quality in higher education, there are two primary components: functional and transformative (Teeroovengadum et al., 2016). The functional aspect refers to the service generation process, while the transformative quality is the technological dimension of service quality (Harvey and Williams, 2010).

The transformative service quality is under-researched in most studies on service quality assessments. A primary goal of HEIs is the transformation of students through cutting-edge teaching and learning tools and technologies (Leibowitz and Bozalek, 2015). Hence, research needs to focus on the need for technology leverage for HEIs (Zachariah, 2007). Surprisingly, many studies have ignored this dimension making existing measures of higher education service quality theoretically limited and practically incomplete in the changing environments. While works examining quality in higher education develop causal models with service quality as a predictor (Brown and Mazzarol, 2009). They discuss functional service quality as a unidimensional construct and omit the technical dimensions. Functional service quality is also multidimensional which several studies do not consider (Ladhari et al., 2011). This study considers the functional and technical dimensions as two distinct concepts and proposes their influence on student satisfaction and HEI brand equity.

Existing Measures of Higher Education Service Quality

An earlier attempt to measure service quality in higher education was that of Hill (1995) who proposed course, teaching quality and methods, administrative staff, student engagement, student-faculty consultation, placement activity, infrastructure, and a few others as important facets of pedagogy. Next, Owlia and Aspinwall (1996) propose six dimensions to service quality, namely: reliability, competence, tangibles, course delivery, staff attitude, and course content. A contribution of this work was the germination of dimensions that could help measure service quality in education and set the path for further works.

Many constructs have been identified by the authors, however, it was found that reliability is the most important dimension and the best services can be delivered through enhanced service reliability. A major drawback of this work is that they measure SERVQUAL of an offline university, with consideration for only the traditional mode of education delivery. However, many HEIs are shifting to online classes, and hence, the joint effect of the institution and the online platform needs to be seen. Also, their model is very simplistic and does not capture the student outcomes clearly.

In other works, directly derived from SERVQUAL (or SERVPERF, a derivative scale), many authors propose measures for higher education (Latif et al., 2019). Firdaus (2005) suggested HedPERF, Abdullah (2006) suggested a modified scale to HedPERF that included two dimensions of HedPERF (non-academic and academic elements) and two of SERVPERF (reliability and empathy). Brochado (2009) compare SERVPERF and HEdPERF and suggests that HEdPeRF presents the best measurement capability for service quality in higher education, implying the suitability of using the service quality concept in higher education. Gupta and Kaushik (2017) reveal that SERVQUAL is a widely applicable scale in the higher education domain and that HEIs need to increase education service quality by deploying this scale.

Online Education Literature

Swan (2017) propose that online education is the future as there is the flexibility of attending classes from anywhere and anytime and that the online education format is a "one size fits all approach". Palvia et al. (2018) argue that online education will be mainstream by 2025. In this editorial, they examine country-level factors that impact the quality of online education. Similarly, Keengwe and Kidd (2010) also provide a review of literature related to online learning and teaching and provide a historical perspective of online education as well as describe the unique aspects of online teaching and learning. The online instructor's role can be viewed under four categories: pedagogical, social, managerial, and technical. The role of students in getting comfortable with online education technology is critical. Tseng et al. (2019) suggest that when graduate students and students with managerial experiences demonstrate a higher level of soft skills, goal setting, self-efficacy, and social skills, their learning outcomes were better. In the context of a university website, Yanga et al. (2005) develop a five-dimension service quality instrument involving usability, the usefulness of the content, adequacy of information, accessibility, and interaction of the website. The authors have validated an instrument to measure user perceived service quality of the university website. While this work is in the context of the website, there are some takeaways from it for the e-learning platforms as well.

In a similar vein, Christobal et al. (2007) develop a scale for perceived e-service quality and argue that perceived quality is a multidimensional construct made of web design, customer service, assurance and order management. Students as consumers will serve as just equivalent for an HEI setting. There is a significant relationship between e-SERVQUAL and perceived value. The linkage between e-SERVQUAL and the perceived value indicates that online users base their assessment of benefits versus costs on their interaction quality with the website used by the higher education institutions. A major drawback of this work is that they measure e-SERVQUAL of an online university, which has only got an online presence with no offline infrastructure (e.g. Byju's in India). However, HEIs are shifting to online classes, and hence, the joint effect of the institution and the online platform needs to be seen.

Next, Zeglat, Shrafat, & Al-Smadi (2016) consider the factors of online database platforms that shape student perceptions. The following factors of the platform are considered: Ease of use, website design, security, reliability and responsiveness. The paper provides a ready reference to measure aspects of online education platforms and their impact on student satisfaction. In the context of online education platforms, some more works add value to this stream. Archibal et al. (2019) find that in online education rapport, convenience, simplicity and user-friendliness are the advantages of using Zoom as a platform, while difficulty connecting, call quality and reliability issues are some of the challenges faced by the students. Similarly, Keith and Yoo (2018), for Google Classroom, emphasize the ease of use of the online platform for student use, along with pace, ease of access, opportunities for collaboration and student voice/agency. For the same platform, Albashtawi and Bataineh (2020) find that students showed a positive attitude towards Google Classroom in terms of ease of use, usefulness, accessibility, and Google applications were positively perceived by both administrative and academic personnel. However, beyond these few, there are no works that explore the role of such online platforms in shaping the efficacy of higher education.

Methodology

Literature Review

This work combines a systematic literature review to invoke the constructs and relationships of the proposed conceptual framework, with the depth interviews conducted to validate the constructs and the relationships (Green, Johnson, & Adams, 2006). Such a rigorous analysis of the literature combined with qualitative research is considered more integrative in nature as a process (Torraco, 2005). To execute the literature review as suggested by Galvan and Galvan (2017), first, the literature was searched with phrases like online education, e-learning, higher education quality, online education success factors, student satisfaction, student engagement, and online student assessment of online education. Important electronic databases like Scopus, Education Research Complete, ProQuest, Science Direct, EBSCO, and Google Scholar were searched for all relevant articles. Given the scope of the study, this search was limited to higher education context and within the last 20 years when most advancement of digital technologies in education has happened. Further searches were conducted through backward referencing. Close to one hundred peer reviewed articles were considered as relevant although the extent of their relevance varied in relation to the themes they captured. The reviewed articles were organized according to their relevance and were further categorized as empirical or conceptual/secondary. Preference was given to empirical articles.

In-Depth Interviews

Since the study involves exploring perception about not only what constitutes quality in the service environment of a higher education institute, but also how those affect student experiences and student-institute relationship, an interpretive approach has been used for this study (Crotty, 1998). Given the exploratory aim, researchers trained in qualitative studies conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews. The respondent group for this phase was current students of three prominent business schools in India. Since qualitative methods executed in real settings capture true experiences and don’t depend on the memory of a respondent, students of HEIs were interviewed while they were at the premises of the business school, each located in Lucknow, Indore, and Bangalore, and had attended a course/programme online at the college. Since the respondents were actual students of education services, social desirability biases that prior studies faced with over-reporting of attitudes were suppressed.

Respondents were also inquired whether they believed they understood all aspects of an HEI and facets of online teaching which makes it a great institution. This was done to ensure only those respondents, who identified and appreciated high quality online education services, are interviewed. Access to the students was facilitated by the management of the respective business schools with whom prior contact was made. All conversations were voice recorded with the promise of maintaining confidentiality and conducted with interview guides to ensure coverage (Patton, 2002). A total of 25 interviews, ranging from 75-90 minutes were conducted by trained qualitative researchers. Of the total interviewees, 54% of the participants were male, 64% of the respondents were in age group of 17-25 years, 16% in the age group 26-35 years, with rest above 46 years. These students ranged from regular flagship graduate programs to executive and PhD programs for which classes were organized online.

First, the participants were asked to recall the various aspects of the institute and the online teaching process which they appreciated during the sessions. Subsequently, they were asked to share experiences with those aspects/features and their views about the HEI itself. Themes, categories, and relationships emerged throughout the interview process, and we continued collecting data until no additional information came from new participants (Strauss and Corbin, 1998). Consumer voices from these interviews were used to both explore the meaning of high quality online education service and to develop propositions, supported with literature. Thematic analysis was used involving deeper reading into comments, deriving interpretations and categorization into patterns matching the literature-based conceptualization (Braun and Clark, 2006). An iterative process was adopted for analysis to ensure the categorization was accurate and relevant. Descriptive validity was ensured by voice recording and accurate transcriptions, while interpretive validity was assured as the trained researcher vetted our interpretations (Maxwell, 1992).

Proposed Constructs

Diep et al. (2017) argue that infrastructure expertise, including academic merit, and ICT competence contributes to student satisfaction in blended learning. The study points towards the independent roles of the institute and the technology in an online education setting. Though the study does not measure student experiences with the system, the study does point towards critical dimensions of HEI service quality – institute and technology. Further, Dai, Haried and Salam (2015) investigate antecedents of online service quality, commitment and loyalty of students in higher education and find that service content quality and service delivery quality are the two important antecedents that result in the commitment of students. This work indicates the institute service quality & platform service quality may be two different aspects of higher education worthy of discussion since the institution is the creator of service while the online platform is the source of delivery of that service. In the interviews, R21 indicated “There a two factors that determine the quality of online teaching: the institute itself and the online platform whose services are subscribed to organize the classes”. Similarly, R22 argued “It is important to look at the platform as a mode of class-conduct to be separate from the institute as the latter has limited control over the former, unless an institute has created its own online platform, which is rare to find in India”. Hence, this work considers the overall service quality to be bifurcated into two parts: institutional service quality and Learning Management System (LMS) service quality.

Institutional Service Quality

Deshields Jr. et al. (2005) argues that faculty performance, staff performance and classes are three of the most important variables that influence students' college experience and overall satisfaction. This is confirmed by Douglas et al. (2006) who suggest that the core service, i.e. the lecture, including the attainment of knowledge, class notes and materials and classroom delivery leads to student satisfaction. Next, Gray and DiLoreto (2016) suggest that course structure, learner interaction with staff, and instructor presence will all have a statistically significant impact on perceived student learning. These three dimensions were also confirmed in the depth interviews. R18 said “a high quality institute, irrespective of the mode of education, is based on three pillars – the faculty, the quality of courses, and the competence of the support staff. Each of these ensure that the college life of a student is a productive as possible”. Similarly, R26 indicated “While it is obvious that high quality faculty and courses are critical to success of any HEI, at the same time, the role of administrative staff in making the students’ lives on- or off-campus fruitful cannot be overlooked”. Hence, based on literary evidence as well as respondent voices, this work proposes three dimensions to institutional service quality: instructor quality, online course quality, and administrative staff quality.

Instructor quality is important for student achievement in higher education (Chetty, Friedman, Rockoff, 2014). Many HEIs develop measures of teacher effectiveness into employee policies to select and retain the best teachers (Mishra, Jha, & Nargundkar, 2020). Yet there is little evidence about instructor effectiveness in higher education. This is especially because, in HEIs, students often choose professors and courses, so it is difficult to isolate the instructors' contributions to student outcomes. Two recent studies conclude that instructors play a larger role in student success in HEIs. Bettinger, Fox, Loeb, and Taylor (2015) find a strong role of instructor effectiveness that is substantially larger than prior studies in determining student performance. A few studies also examine whether certain instructor characteristics correlate with student success, though the results are quite mixed. Hence, to clarify the role of instructors on student and HEI performance, this work considers instructor quality as the first dimension of institute service quality. The importance of this dimension is corroborated in the interviews where R1 said “If there is one factor that makes an institute great is the quality of faculty it has. A lot of students form perception about the overall status of an institute based on the type of professors it has. Some of the faculty members are so reputed that students want to join an institute because of them”. Similarly, R18 argued “An institute can have everything, but if it does not have good quality faculty, then the rest of it, be it infrastructure, placements, location, etc., does not matter. Without good faculty there is no learning for the students and thus, the time spent with the college goes waste”.

While there is substantial research into the changing nature HEIs, there is little research into the changing roles of administrative and professional staff that determine the performance of the HEI. This lack of research on support staff is largely there because most works prefer to focus on the instructors and the infrastructure of the HEI (Pitman, 2000). In the last few years, there is a growing discussion on how the professional behaviour of the administrative staff shape student experiences in HEIs (e.g., Whitchurch, 2010). In online education, the role of administrative staff becomes very critical in form of setting up online classes, smooth conduct of sessions, as well as post-session tasks, like the collation of student comments, student tasks, assignments, and even evaluation. Hence, administrative staff quality is considered the second dimension of institutional service quality. The support for this second dimension also came from the respondent interviews. R19 suggested “The staff of a college are its backbone and practically run the institute, yet they get limited credit for their work. Without them, the system would just crumble”. Similarly, R14 and R9 gave similar comments and argued “If there is one part of the system that student most commonly interact with for their day to day concerns are the staff of the institute. It is they who have a crucial role in making our lives fruitful when it comes to the association with the institute”.

Finally, online course quality is an outcome of the instructional template of a course that is developed before a course is delivered, and reflects the instructor’s teaching and learning delivery. A literature review suggests that course quality is largely shaped by the opinions and perceptions of students (Hixon, Barczyk, Ralston-Berg, & Buckenmeyer, 2016), and that students’ experience with courses at an HEI are key to the success of the institute (Mishra, Jha, and Nargundkar, 2020). Thus, well-organized courses are desirable, but their impact on better student learning outcomes is debatable and needs more clarity. The structure of online courses needs to be different from offline ones given the different structure of course delivery, with more focus on the upskilling of the participants and the visual enhancement of content for greater online engagement. Hence, online course quality is considered the third dimension of institutional service quality. The importance of this dimension was revealed in the depth reviews. R21 mentioned “There is no substitute for a good course in an online environment. In the online system where physical interaction with the other institute elements are limited, content of the course is king and that is what helps us know how good the institute is”. In the same vein, R25 indicated “In the online domain, designing and delivering courses is huge challenge and it is important for such institutes offering online programs to curate the courses properly for maximum learner benefit”.

Learning Management System (LMS) Service Quality

The e-service quality model used in various works has been adopted here to identify the service quality features of an LMS system. Parasuraman et al. (1985) argue that e-service quality reflects a system's capability to support an effective transaction and is reflected through the users' appraisal of the virtual facility (Santos, 2003). This study incorporates the modified model of e-service quality in which size elements, site organization, responsiveness, reliability, user-friendliness, personal needs, and efficiency are highlighted. Site organization represents the navigation design of the platform that makes the location of options at an appropriate place and makes the navigation experience for the user more intuitive. In the interviews, R14 mentioned “Somehow, I feel that Zoom’s interface is the most simple to understand as all the buttons, menus, and dropdowns are exactly at the place they should be. Also, searching for a function is easy as the user intuitively can guess where it is”. Similarly, another respondent R21 said “In terms of application design, Google Meet with its very simple interface is good, though I agree it lacks the features that Zoom offers”. Multiple studies show a positive relation between site organization and customer experience with the interface of the site, in this case the LMS platform (Amin, 2016).

Next, responsiveness represents the reaction time of the service provider of the platform in case there is a concern with the interface. Hammoud et al. (2018) suggest that LMS managers can develop responsiveness through four steps. One, regulate and function the service appropriately; two, guide customers if any failure occurs; three, handle any error promptly; and four, give a quick response to any clients' query. This facet of the LMS platform was also brough up in the interviews. R19 said “In the initial days, Zoom platform would create a lot of issues, but then I found the IT support very prompt in ironing out the concerns”. Similarly, R8 mentioned “There have been times when I have written an email to the customer care of Zoom after I faced some bugs in their software, I would get a very quick reply thanking me for pointing it out and the fact that they would work on the issue was very warming”.

Previous studies also support a positive relationship between reliability and customer experience (Hammoud et al., 2018). Reliability indicates that the LMS site is dependable, trustworthy and secure. This is also supported during the interviews where R5 said “When we have to attend long sessions on an online platform, it is critical that the platform is robust and does not crash at any time”. Further, R21 said “There were times when I would keep getting disconnected from my class on Zoom and it was super-frustrating. Zoom needs to work on the reliability of the platform”.

Next, user-friendliness represents the intuitiveness of the LMS platform for its usage and is a major factor in ensuring a rewarding experience for its users. Acohido (2009) mentions that ease-of-use, an important construct in Technology Adoption Model, can help a platform to achieve a competitive advantage and has a great impact on user faithfulness in the higher institute. This aspect of LMS platform was also highlighted my multiple respondents in the interviews. R12, R18, and R22 indicated “The reason for success of Zoom at a time when other platforms failed is how easy-to-use it was. I found platforms like Google Classroom and Cisco Webex extremely complicated”. Another respondent, R7 mentioned “While Webex and Teams are very capable online class tools, somehow, Zoom is very intuitive and user-friendly, hence, my college decided to go for its subscription”.

According to Grönroos (2007), e-service should consider the personal needs of its users. Keskar et al. (2020) argue that e-service providers should know the age, gender, lifestyle and preferences of their consumers and fulfil those personal needs through customized services. Amin (2016) mentions that personal needs have a significant relation with users satisfaction, as it makes the users feel more connected with the service. The important of fulfilling personal needs was elicited during the interviews where R10 mentioned “Somehow, it feels like the LMS platform used by my college is tailor-made keeping the customers in mind. The features and functions of the platform seem to be suited to people of my generation”.

Further, Kheng et al. (2010) suggest that user demands are fulfilled with efficiency, they become happy with the e-service. Efficient response to consumer queries demonstrates the e-services efficiency in this study. Efficiency is the most important factor of e-service quality and positively influences customer satisfaction (Hammoud et al., 2018). In the context of LMS platforms, efficiency was highlighted by R14 as “As an LMS platform, I find Zoom to be very data efficient, I can attend classes on my mobile data, yet it runs very smoothly”. Similarly, R11 mentioned “I am on a prepaid mobile data pack and attend my classes on Meet, it is very soft on data and I don’t need to recharge my pack again and again”.

Outcome: Student Engagement

There is limited guarantee of learning and expected outcomes with technology-enabled education (Bond, 2020). Hence, there have been recent efforts to measure the effectiveness of online learning though various parameters (Kovanović et al., 2016; Soffer & Cohen, 2019; Dwivedi et al., 2019). Such parameters are beyond the generic knowledge-based examination that is used to evaluate a student’s academic performance. Rather, a more relevant measure of such effectiveness is student engagement during the online learning process (Riordan et al., 2016). Student engagement is now regarded as a strong measure of online educational quality and is expected to be positively related to student’s learning outcomes and successful program completion (Kuh, 2009). The institutional interventions significantly influence how students experience the entire learning process and remain engaged with the system, however, this relationship remains underexplored (Hsieh & Tsai, 2012; van Leeuwen et al., 2013; Zhu, 2006).

In the literature, there are three dimensions to student engagement. Previous research defined behavioural engagement as involvement in online learning tasks with effort, persistence, attention, and in-class contribution (Skinner & Belmont, 1993). This dimension was reflected in interviews by R12 as “It is important to keep focus in the online class, given the challenges, to ensure that the learning process actually happens”. As the next dimension, cognitive engagement reflects the students’ psychological investment in the tasks required to ensure academic learning, and the efforts they make to comprehend concepts, and develop new knowledge (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004; Kahu, 2013; Kahu & Nelson, 2018). In the interviews, R11 pointed towards this dimension of engagement as “The real learning in the class happens only when the students are convinced that they need to apply their minds to the concept being discussed and project them for further applications”. The final dimension, emotional engagement, includes hedonic reactions to the class environment and involves students’ feelings of belongingness and relatedness to teachers, courses, the institute and their peers (Lawson & Lawson, 2013). In the interviews, R17 mentioned “Ultimately, it is important that the student enjoys the class, especially because in the online mode of conduct, it is very easy for a student to disengage with the class if there is no emotional bond that they develop with the class environment”.

Outcome: Student Satisfaction

Nortvig, Petersen and Balle (2018), through a literature review, indicate that factors like educator presence in online settings, interactions between students, teachers and content, and deliberate connections between online and offline activities and between campus-related and practice-related activities, are the prime source of student satisfaction. Such satisfaction is the students' perception that their expectations from an HEI have been met. While exploring students' perceptions of quality in higher education, Hill, Lomas & MacGregor (2003) find that students value their teachers and that their educational experience is influenced by the teacher's expertise in the classroom. Further, the institute's support network is also valued by the students. This lends value to the study of student satisfaction in a blended learning model. In the domain of online education, Yilmaz (2016) argues that participants' self-efficacy, self-directed learning, and motivation toward e-learning, shaped by the quality of the platform, lead to student satisfaction in an online classroom. The importance of satisfaction was evoked in the interviews as well, where R15 said “At the end of the day, education is also a service, and hence, the student as a customer should feel satisfied with the learnings he/she has acquired through the online programme, this in a way serves as a return-on-investment for the student”.

Outcome: HEI Brand Equity

Brand equity is a multi-dimensional concept (Yoo et al., 2000). The steadily growing literature on brand equity (e.g. Pappu and Quester, 2006; Mishra, 2016) suggests different dimensions of customer-based brand equity. A comprehensive literature review on customer-based brand equity reveals that brand association, perceived value, perceived quality, trust and loyalty are five prominent dimensions of brand equity (e.g., Mishra, Dash, and Cyr, 2014; Kumar, Dash, and Purwar, 2013). The respondent interviews also revealed the presence of these brand equity dimensions are being indicated alongside the operational definitions of the constructs. Brand association is the unique set of imageries that that a brand has in the cognition of the consumer, while the perceived brand quality is a consumer's overall impression of the relative inferiority or superiority of the education services of the higher education institute brand, with respect to other such brands (Zeithaml, 1988). In the interviews, R22 and R2, respectively, mentioned “There is a clutter of institutes offering online programmes and degrees, a good institute needs to stand out with unique propositions which people relate to that brand”, and “A good HEI brand is one that reflects overall good quality in everything it does”.

The perceived brand value indicates the overall economic value of the services of higher education, in comparison to its competitors. This aspect was suggested in the interviews by R25 as “It is important that the institute should be seen as one that provides high-quality education at not a very prohibitive cost, for more students to gravitate towards it”. Perceived brand trust is the expectation of the institute brand's perceived credibility that reduces the perceived risk for the customer (Doney and Cannon, 1997). Finally, brand loyalty is the consumer commitment to patronize an institute brand for further services in the future (Oliver, 1993). Both of these brand equity dimensions found their mention in the quote of R21, who said “Through great academic systems in place, an HEI needs to create trust in the participants that what they are learning is of high value to them. If they believe that the courses and concepts are going to make them a better performer, they will also be totally committed not only to the learning process, but also to the institute once they graduate”. The concept of developing brand equity for the HEIs is critical as strong brands serve as strategic assets that create value for the organization. Modern HEIs are a combination of campuses, courses, programs and degrees, and with the current COVID-19 impact, online version of those, branding has become crucial (Chapleo 2015).

Conceptual Framework

The current work integrates the service quality framework from higher education literature and online platform literature in the same model, as determinants of student satisfaction and institute brand building. In the current study, we not only apply the SERVQUAL framework to measure the institute quality, but also apply it to simultaneously measure the online platform service quality. It is proposed that these two quality perceptions will simultaneously impact student engagement, measured by cognitive, emotional and behavioural engagement, which in turn influences satisfaction, and the institute's brand equity, measured by perceived quality, trust, perceived value, and brand loyalty. The proposed model of this work is presented in Figure 1.

Institutional Service Quality and Student Engagement

In the context of online learning, the students are separate from the instructor, the institute, as well as each other. In such a case, the distance may become a barrier to the learning process due to loss of information, emotional enjoyment otherwise gained in a physical class, and enhanced solitude (Molinillo, et al., 2018). Hence, the instructor has an important role in adapting his/her teaching methods, including development of the online course content, so that such a pedagogy is important in supporting the students' knowledge acquisition as well as create emotional connection with the institute (Kuh, 2008; 2009; 2016) and Dwivedi et al. (2019). The same argument is extended to the role of the support administrative staff who have to ensure that the distant students remain engaged to the institute, by facilitating smooth class conduct, quick distribution of course material, adherence to institute rules and regulations, and prompt resolution of their queries and concerns. Such an engagement is the foundation of cognitive, social, and emotional presence of the student in the institutional community (Garrison, 2011; Garrison & Vaughan, 2008).

This relationship was also reflected in the respondent comments. R6 said “The role of the institute is important to ensure that we feel ourselves, both mentally and emotionally, as part of the institute, even though we are sitting at a distance. Such integration requires the complete support from the institute, be it faculty or the staff”. Similarly, R9 said “The institute made best efforts, despite the challenges, to keep us focussed on studies. The classes were conducted smoothly and on time, thanks to the diligent office staff, the faculty were great in creating interesting classroom environment leading us to think and reflect in the class discussions, and the courses themselves were super-enriching. I always looked forward to the next class of the courses”. Based on this, we propose:

Proposition 1: Institutional service quality, as a combination of instructor quality, administrative staff quality, and course quality is a positive driver of student engagement, represented by cognitive, emotional, and behavioural engagement.

LMS Service Quality and Student Engagement

In the era of ICT, engagement with online services is the customer's overall assessment of the quality of services or products offered in the online domain (Anderson & Srinivasan, 2003). There is good evidence supporting the relationship between e-service quality and customer engagement (Chapleo 2015). To obtain student engagement, universities must understand e-learning service quality parameters perceived by students, and then enhance overall e-learning service quality, not only through its core services but also by employing an LMS platform that enhances service delivery. While each of these is part of the core HEI service quality, the LMS service quality will help to manifest them to the students and lead to their immersion with learning.

The connect between LMS service quality and engagement was also apparent during the interviews. R5 said “A great part to creating great learning experience was the LMS platform used by the institute. The seamlessness of the platform and all its technical capabilities made the classes very interesting and engaging”. In the same vein, R22 said “In an online environment, the LMS platform serves as the mediator between the institute and the student. If the LMS platform is of poor quality, it will dent the class experiences irrespective of the efforts of the institute”. Based on the insights, we propose:

Proposition 2: LMS service quality, as a combination of site organization, responsiveness, reliability, user-friendliness, personal needs and efficiency, is a positive driver of student engagement, represented by cognitive, emotional, and behavioural engagement.

Student Engagement and Satisfaction

Satisfaction is the perceived performance experienced by customers. Consumers are satisfied only when they that the firm is fair to them and the service is engaging (Oliver, 1993). Thus, customers might feel dissatisfaction when they perceive the quality of the firms' services and the resultant engagement is not worthy of the price paid for them. The relationship between HEI service quality and student satisfaction is an extant discussion (Anderson & Srinivasan, 2003). A study by Khoo et al. (2015) on the education sector shows a positive influence.

The relationship between student engagement and satisfaction was also apparent in the interviews, where R6 said “Despite the fact that this program ran online, I felt so immersed in the classes and the courses due to the sheer quality of teaching of the faculty and the course material. I am so happy and satisfied that I enrolled for this program”. Similarly, R18 said “I never felt that I was away from the institution while my classes went on in the online mode. The environment was very engaging, and I am very happy with the overall experience”. Based on the insights, we propose:

Proposition 3: Student engagement, represented by cognitive, emotional, and behavioural engagement, is a positive driver of student satisfaction.

Student Satisfaction and HEI Brand Equity

There is a rich history of the relationship between customer satisfaction and brand equity. In a B2B service, Geigenmüller and Bettis-Outland (2012) suggest that customer satisfaction with a service boosts the equity of the brand providing the service. In the case of hospital service, Kim, et al. (2008) support a positive effect of customer satisfaction on brand equity. Next, Pappu and Quester (2006) show a positive influence of customer satisfaction with the retailer's brand equity. Although the service quality and brand equity relationship are well documented in the literature, the relationship is nascent in the HEI domain. Akroush et al. (2011) discuss that perceived brand equity of a retail brand is a positive outcome of the shoppers' satisfaction. To build it up, Pappu and Quester (2006), recommend that customer loyalty, a dimension of brand equity, is modulated by customer satisfaction since only a satisfied customer can have a favourable attitude and loyalty towards the retailer. Similarly, Christodoulides et al. (2006) argue that brand equity occurs only when the service quality of the brand exceeds the cost, and satisfaction is a natural outcome (Morgan-Thomas and Veloutsou 2013).

During the interviews, R15 said “The way the classes were conducted during the pandemic by my institute has really won my heart over. All members of the institute worked really hard to make our experiences as fruitful as possible. The institute has won my heart over and I really feel that I consider myself a big fan of this brand”. Along these lines, R3 said “the way the institute handles the crisis by switching from offline to online classes quickly, whole keeping the classes engaging, has me really happy with the experience. I will always remember the moments with the institute which for me is an important entity in my life”. Based on this discussion, we propose:

Proposition 4: Student satisfaction is a positive driver of HEI brand equity, composed of perceived quality, perceived value, student trust and loyalty.

Conclusion

The conceptual model of this work offers a few theoretical and practical contributions. Multiple studies focus on either the instructor's desirable attributes, like gender, ethnicity, age, teaching techniques and skills, instructor reputation, position, rank, communication abilities, appearance, social media presence, and their environmental interactions, like the institute's infrastructures, staff, and courses that determine students' evaluations (e.g., Harnish and Bridges, 2011). However, none of these studies considers the student satisfaction arising from a unique combination of not only the primary institute quality but also the secondary LMS platform service quality. The service quality of the LMS platform is beyond the control of the HEI and hence, this work presents a unique dynamic perspective in evaluating and projecting the performance of the institute and the LMS platform is shaping the brand equity of the institute.

In an initial effort, this work integrates the SERVQUAL perspective for the institute and platform and examines their joint effect on student satisfaction, something which recent literature has not done. In the COVID-19 situation when the institutes are taking classes online and which will remain in practice for a long time, our findings will also help them to align the institute and platform quality to ensure maximum student satisfaction and institute brand equity. Further, online executive education has become quite popular with many HEIs, due to the lower costs of conducting this mode of education. Hence, our work is expected to not only add value to the current literature on SERVQUAL in the higher education context but also guide practitioners to develop the institute and LMS platform service qualities such that students are satisfied with the institute and enable the brand equity of the HEI. Overall, the work provides a new theoretical perspective to provide an examination of the role of the institute and the LMS platform on the overall student satisfaction from the HEI as well as investigates novel moderating variables, like the student’s susceptibility to peer influence, that will shape the process.

End Notes

1R: Respondent, number indicates the number assigned to that respondent.

References

Abdullah, F. (2006). Measuring service quality in higher education: HEdPERF versus SERVPERF. Marketing Intelligence & Planning.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Acohido, B. (2009). Cybercrooks stalk small businesses that bank online. USA Today.

Akroush, M. N., Dahiyat, S. E., Gharaibeh, H. S., & Abu‐Lail, B. N. (2011). Customer relationship management implementation: an investigation of a scale's generalizability and its relationship with business performance in a developing country context. International Journal of commerce and Management.

Albashtawi, A., & Al Bataineh, K. (2020). The effectiveness of google classroom among EFL students in Jordan: An innovative teaching and learning online platform. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 15(11), 78-88.

Amin, M. (2016). Internet banking service quality and its implication on e-customer satisfaction and e-customer loyalty. International journal of bank marketing.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Anderson, R. E., & Srinivasan, S. S. (2003). E‐satisfaction and e‐loyalty: A contingency framework. Psychology & marketing, 20(2), 123-138.

Archibald, M. M., Ambagtsheer, R. C., Casey, M.G., & Lawless, M. (2019). Using zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. International journal of qualitative methods, 18, 1609406919874596.

Bastiaensens, S., Pabian, S., Vandebosch, H., Poels, K., Van Cleemput, K., DeSmet, A., & De Bourdeaudhuij, I. (2016). From normative influence to social pressure: How relevant others affect whether bystanders join in cyberbullying. Social Development, 25(1), 193-211.

Bettinger, E., Fox, L., Loeb, S., & Taylor, E. (2015). Changing distributions: How online college classes alter student and professor performance. Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis, 15-10.

Bond, M. (2020). Facilitating student engagement through the flipped learning approach in K-12: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 151, 103819.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Brochado, A. (2009). Comparing alternative instruments to measure service quality in higher education. Quality Assurance in education.

Brown, R.M., & Mazzarol, T.W. (2009). The importance of institutional image to student satisfaction and loyalty within higher education. Higher education, 58(1), 81-95.

Chaney, B.H., Eddy, J.M., Dorman, S. M., Glessner, L.L., Green, B.L., & Lara-Alecio, R. (2009). A primer on quality indicators of distance education. Health promotion practice, 10(2), 222-231.

Chapleo, C. (2015). Brands in higher education: Challenges and potential strategies. International Studies of Management & Organization, 45(2), 150-163.

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., & Rockoff, J. E. (2014). Measuring the impacts of teachers II: Teacher value-added and student outcomes in adulthood. American economic review, 104(9), 2633-79.

Christodoulides, G., De Chernatony, L., Furrer, O., Shiu, E., & Abimbola, T. (2006). Conceptualising and measuring the equity of online brands. Journal of marketing management, 22(7-8), 799-825.

Cialdini, R.B., & Goldstein, N.J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 55, 591-621.

Cristobal, E., Flavian, C., & Guinaliu, M. (2007). Perceived e‐service quality (PeSQ): Measurement validation and effects on consumer satisfaction and web site loyalty. Managing service quality: An international journal.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Crotty, M.J. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. The foundations of social research, 1-256.

Dai, H., Haried, P., & Salam, A. F. (2011). Antecedents of online service quality, commitment and loyalty. Journal of computer information systems, 52(2), 1-11.

Dennis, C., Papagiannidis, S., Alamanos, E., & Bourlakis, M. (2016). The role of brand attachment strength in higher education. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3049-3057.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

DeShields, O. W., Kara, A., & Kaynak, E. (2005). Determinants of business student satisfaction and retention in higher education: applying Herzberg's two‐factor theory. International journal of educational management.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Diep, A. N., Zhu, C., Struyven, K., & Blieck, Y. (2017). Who or what contributes to student satisfaction in different blended learning modalities?. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(2), 473-489.

Doney, P. M., & Cannon, J. P. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer–seller relationships. Journal of marketing, 61(2), 35-51.

Douglas, J., Douglas, A., & Barnes, B. (2006). Measuring student satisfaction at a UK university. Quality assurance in education.

Eagle, L., & Brennan, R. (2007). Are students customers? TQM and marketing perspectives. Quality assurance in education.

East, L., Stokes, R., & Walker, M. (2014). Universities, the public good and professional education in the UK. Studies in Higher Education, 39(9), 1617-1633.

Firdaus, A. (2005). The development of HEdPERF: a new measuring instrument of service quality for higher education sector‟‟ Paper presented at the Third Annual Discourse Power Resistance Conference: Global Issues. Local Solutions, University of Plymouth.

Galvan, J. L., & Galvan, M. C. (2017). Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences. Routledge.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Geigenmüller, A., & Bettis‐Outland, H. (2012). Brand equity in B2B services and consequences for the trade show industry. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing.

González, M. E. A., Comesaña, L. R., & Brea, J. A. F. (2007). Assessing tourist behavioral intentions through perceived service quality and customer satisfaction. Journal of business research, 60(2), 153-160.

Gray, J. A., & DiLoreto, M. (2016). The effects of student engagement, student satisfaction, and perceived learning in online learning environments. International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation, 11(1), n1.

Grönroos, C. (2007). Service management and marketing: customer management in service competition. John Wiley & Sons.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gupta, P., & Kaushik, N. (2018). Dimensions of service quality in higher education–critical review (students’ perspective). International Journal of Educational Management.

Haimiti, A., Shan, J. I. N., & Deqing, W. A. N. G. (2014). D2L Learning Management System in America: It’s Character and It’s Inspiration Towards Online Education of China. Higher Education of Social Science, 7(3), 47-52.

Halai, N. (2013). Quality of private universities in Pakistan: An analysis of higher education commission rankings 2012. International Journal of Educational Management.

Hammoud, J., Bizri, R. M., & El Baba, I. (2018). The impact of e-banking service quality on customer satisfaction: Evidence from the Lebanese banking sector. Sage Open, 8(3), 2158244018790633.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Harnish, R. J., & Bridges, K. R. (2011). Effect of syllabus tone: Students’ perceptions of instructor and course. Social Psychology of Education, 14(3), 319-330.

Harvey, L., & Williams, J. (2010). Fifteen years of quality in higher education.

Hill, F. M. (1995). Managing service quality in higher education: the role of the student as primary consumer. Quality assurance in education.

Hill, Y., Lomas, L., & MacGregor, J. (2003). Students’ perceptions of quality in higher education. Quality assurance in education.

Hixon, E., Barczyk, C., Ralston-Berg, P., & Buckenmeyer, J. (2016). The Impact of Previous Online Course Experience RN Students' Perceptions of Quality. Online Learning, 20(1), 25-40.

Jung, I., & Latchem, C. (2007). Assuring quality in Asian open and distance learning. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 22(3), 235-250.

Kahu, E. R. (2013). Framing student engagement in higher education. Studies in higher education, 38(5), 758-773.

Kahu, E. R., & Nelson, K. (2018). Student engagement in the educational interface: understanding the mechanisms of student success. Higher education research & development, 37(1), 58-71.

Kang, G. D., & James, J. (2004). Service quality dimensions: an examination of Grönroos’s service quality model. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal.

Keengwe, J., & Kidd, T. T. (2010). Towards best practices in online learning and teaching in higher education. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 6(2), 533-541.

Keskar, M. Y., Pandey, N., & Patwardhan, A. A. (2020). Development of conceptual framework for internet banking customer satisfaction index. International Journal of Electronic Banking, 2(1), 55-76.

Kheng, L. L., Mahamad, O., & Ramayah, T. (2010). The impact of service quality on customer loyalty: A study of banks in Penang, Malaysia. International journal of marketing studies, 2(2), 57.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Khoo, S., Ha, H., & McGregor, S. L. (2017). Service quality and student/customer satisfaction in the private tertiary education sector in Singapore. International Journal of Educational Management.

Kim, W. G., Jin-Sun, B., & Kim, H. J. (2008). Multidimensional customer-based brand equity and its consequences in midpriced hotels. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 32(2), 235-254.

Kuh, G. D. (2009). What student affairs professionals need to know about student engagement. Journal of college student development, 50(6), 683-706.

Kumar, R. S., Dash, S., & Purwar, P. C. (2013). The nature and antecedents of brand equity and its dimensions. Marketing Intelligence & Planning.

Ladhari, R., Ladhari, I., & Morales, M. (2011). Bank service quality: comparing Canadian and Tunisian customer perceptions. International Journal of Bank Marketing.

Latif, K. F., Latif, I., Farooq Sahibzada, U., & Ullah, M. (2019). In search of quality: measuring higher education service quality (HiEduQual). Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 30(7-8), 768-791.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lawson, M. A., & Lawson, H. A. (2013). New conceptual frameworks for student engagement research, policy, and practice. Review of educational research, 83(3), 432-479.

Leibowitz, B., & Bozalek, V. (2015). Foundation provision-a social justice perspective. South African Journal of Higher Education, 29(1), 8-25.

Maxwell, J. (1992). Understanding and validity in qualitative research. Harvard educational review, 62(3), 279-301.

Mishra, A. (2016). Attribute-based design perceptions and consumer-brand relationship: Role of user expertise. Journal of Business Research, 69(12), 5983-5992.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mishra, A., Dash, S.B., & Cyr, D. (2014). Linking user experience and consumer-based brand equity: the moderating role of consumer expertise and lifestyle. Journal of Product & Brand Management.

Mishra, A., Jha, S., & Nargundkar, R. (2020). The role of instructor experiential values in shaping students’ course experiences, attitudes and behavioral intentions. Journal of Product & Brand Management.

Moore, K., Coates, H., & Croucher, G. (2018). Understanding and improving higher education productivity. In Research handbook on quality, performance and accountability in higher education. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Morgan-Thomas, A., & Veloutsou, C. (2013). Beyond technology acceptance: Brand relationships and online brand experience. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 21-27.

Nortvig, A.M., Petersen, A.K., & Balle, S.H. (2018). A Literature Review of the Factors Influencing E‑Learning and Blended Learning in Relation to Learning Outcome, Student Satisfaction and Engagement. Electronic Journal of E-learning, 16(1), pp46-55.

Oliver, R. L. (1993). Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of the satisfaction response. Journal of consumer research, 20(3), 418-430.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Owlia, M.S., & Aspinwall, E.M. (1996). A framework for the dimensions of quality in higher education. Quality assurance in education.

Palvia, S., Aeron, P., Gupta, P., Mahapatra, D., Parida, R., Rosner, R., & Sindhi, S. (2018). Online education: Worldwide status, challenges, trends, and implications. Journal of Global Information Technology Management, 21(4), 233-241.

Pappu, R., & Quester, P. (2006). Does customer satisfaction lead to improved brand equity? An empirical examination of two categories of retail brands. Journal of Product & Brand Management.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A., & Berry, L.L. (1985). A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of marketing, 49(4), 41-50.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A., & Berry, L.L. (1994). Reassessment of expectations as a comparison standard in measuring service quality: implications for further research. Journal of marketing, 58(1), 111-124.

Pitman, T. (2000). Perceptions of academics and students as customers: A survey of administrative staff in higher education. Journal of Higher Education policy and management, 22(2), 165-175.

Quinn, A., Lemay, G., Larsen, P., & Johnson, D.M. (2009). Service quality in higher education. Total Quality Management, 20(2), 139-152.

Riordan, T., Millard, D.E., & Schulz, J.B. (2016). How should we measure online learning activity?. Research in Learning Technology, 24, 1-28.

Sebastian, R.J., & Bristow, D. (2008). Formal or informal? The impact of style of dress and forms of address on business students' perceptions of professors. Journal of education for business, 83(4), 196-201

Shelton, K. (2011). A review of paradigms for evaluating the quality of online education programs. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 4(1), 1-11.

Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M.J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of educational psychology, 85(4), 571.

Soffer, T., & Cohen, A. (2019). Students' engagement characteristics predict success and completion of online courses. Journal of computer assisted learning, 35(3), 378-389.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques.

Sujchaphong, N., Nguyen, B., & Melewar, T. C. (2015). Internal branding in universities and the lessons learnt from the past: The significance of employee brand support and transformational leadership. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(2), 204-237.

Swan, M. (2017). Anticipating the economic benefits of blockchain. Technology innovation management review, 7(10), 6-13.

Teeroovengadum, V., Kamalanabhan, T.J., & Seebaluck, A.K. (2016). Measuring service quality in higher education: Development of a hierarchical model (HESQUAL). Quality Assurance in Education.

Torraco, R.J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human resource development review, 4(3), 356-36

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tseng, H., Yi, X., & Yeh, H.T. (2019). Learning-related soft skills among online business students in higher education: Grade level and managerial role differences in self-regulation, motivation, and social skill. Computers in Human Behavior, 95, 179-186.

Van Leeuwen, A., Janssen, J., Erkens, G., & Brekelmans, M. (2014). Supporting teachers in guiding collaborating students: Effects of learning analytics in CSCL. Computers & Education, 79, 28-39.

Whisman, R. (2009). Internal branding: a university's most valuable intangible asset. Journal of Product & Brand Management.

Whitchurch, C. (2010). Some implications of ‘public/private’space for professional identities in higher education. Higher education, 60(6), 627-640.

Yilmaz, R.M. (2016). Educational magic toys developed with augmented reality technology for early childhood education. Computers in human behavior, 54, 240-248.

Yoo, B., & Donthu, N. (2001). Developing and validating a multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale. Journal of business research, 52(1), 1-14.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yoo, B., Donthu, N., & Lee, S. (2000). An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 28(2), 195-211.

Yuan, R., Liu, M.J., Luo, J., & Yen, D.A. (2016). Reciprocal transfer of brand identity and image associations arising from higher education brand extensions. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3069-3076.

Zeglat, D., Shrafat, F., & Al-Smadi, Z. (2016). The impact of the E-service quality (E-SQ) of online databases on users’ behavioural intentions: a perspective of postgraduate students. International Review of Management and Marketing, 6(1), 1-10.

Zeithaml, V.A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of marketing, 52(3), 2-22.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 22-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-12885; Editor assigned: 24-Oct-2022, PreQC No. AMSJ-22-12885(PQ); Reviewed: 26-Nov-2022, QC No. AMSJ-22-12885; Revised: 23-Dec-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-12885(R); Published: 21-Jan-2023