Review Article: 2022 Vol: 26 Issue: 5

Effect of Continuous Professional Development on the Job Performance of Public University Administrators: Evidence from an Emerging Economy

Daniel Susuawu, University of Health and Allied Sciences, Ghana

Abigail Baah-Koranteng, Takoradi Technical University

Godwin Boakye Antwi, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science & Technology

Citation Information: Susuawu, D., Baah-Koranteng, A., & Antwi, G.B. (2022). Effect of continuous professional development on the job performance of public university administrators: evidence from an emerging economy. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 26(5), 1-11.

Abstract

A wide variety of professionals participate in Continuous Professional Development (CPD) to learn and apply new knowledge and skills that will improve their performance on the job. Most organizations acknowledge the CPD of the employees to be important in the pursuit of set targets and objectives. Thus, this study aimed to assess the effect of CPD on the job performance of public university administrators in Ghana. Further, the study establishes if gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank affect CPD training of administrators. A quantitative research design was adopted and the survey was used as the method of inquiry on 300 administrators sampled in a stratified manner from the ten public universities in Ghana. The collected data was analyzed using Pearson Moment Correlation Coefficient and linear regression. This study found that there is moderately positive significant relationship between CPD and job performance of public university administrators in Ghana. This implies that administrators who received CPD trainings were better positioned to deliver superior performance. The result further showed that gender, age, qualification, work experience (except length of role 5-7) and rank do not impact significantly on administrators’ job performance. Finally, the findings showed that gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank do not affect CPD training of public university administrators. This implies that regardless of gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank, administrators will need to undergo CPD training from time-to-time in order to improve their job performance considering the dynamic nature of the university environment.

Keywords

Continuous Professional Development, Public Universities, Job Performance, Ghana.

Introduction

Generally, university workers could be organised into academic and non-academic staff. The academic staff comprises lecturers, research fellows and research assistants, while the non-academic staff includes administrators, technical staff and other auxiliary workers. Whereas the academic staff members focus on teaching, learning, assessment and research, the non-academic staff are usually supporting staff responsible for managing and supervising the daily activities in the university. Key among the non-academic staff of a university are the administrators who are responsible for developing and coordinating academic programmes and student activities. They ensure that the institution and government requirement of recording, reporting and archiving information on students’ achievement are fulfilled (Nawi et al., 2016).

However, the current challenges of universities are increasingly making the roles of the university administrators more of problem-solving than just coordinating university activities (Akeke et al., 2015). In the 21st century, the university administrators’ roles are more of bringing efficiency and harmony to the operations and management of higher education. The university environment is dynamic, complex and turbulent which affects administrators’ performance. For instance, inadequate funding, competition, diversity in student population, increasing internationalisation, high students’ fees and increasing number of students, are major challenges that complicate the work of the university administrators (Ummah & Athambawa, 2018). Therefore, administrators have to be mindful of aiming at quality and adopt a learning-based approach to university administration, to cope with the complex environment. The university administrators must continually upgrade themselves to be able to tackle the contemporary issues and challenging trends confronting higher education by learning new things that will positively impact on their institution, become more competent in the discharge of their duties and increase their confidence level.

Continuous Professional Development (CPD) has therefore become the panacea for university administrators to learn new skills and improve their performance in the face of a challenging environment. CPD is the most commonly used approach the world over to develop staff in this modern and ever-changing work environment. According to Chikari et al. (2015), CPD is the systematic maintenance, improvement and broadening of knowledge and skills and the development of personal qualities necessary for the execution of professional and technical duties throughout an individual’s working life. Thus, professionals including university administrators must engage in it to improve their job performance and professional growth. CPD covers an employee’s working life. It starts with staff orientation, on-job training, experience, short courses, professional courses, postgraduate degrees or diplomas. CPD is the foundation on which the confidence and competence of individual employees are built Robbins. Employees are major assets of any organisation. They play an active role towards organizational success that cannot be underestimated. Equipping these unique assets through effective CPD training becomes imperative in order to maximize their job performance. As pointed out by Oduma & Were (2014), CPD is often used to close the gap between current performances and expected future performance. Many employees in different organizations have trained but they have remained stagnant with little evidence of job performance improvement.

The role of university administrators in the successful operation of higher education cannot be underestimated. Equipping them through effective CPD training becomes imperative to maximize their job performance. For these reasons, the Ghana Association of University Administrators (GAUA), the mouthpiece of university administrators, cherish and espouse CPD. Over the years, the GAUA has orchestrated different programmes and policies to encourage CPD among its members, in order to motivate and enhance their performance towards the achievement of set targets and objectives in the university. However, the question emanating from these initiatives is; has the opportunity for CPD training enhanced performance among the administrators in public universities? To answer this question, this study, which seeks to investigate the effect of CPD on job performance of public university administrators in Ghana becomes indispensable.

Moreover, the impact of CPD on job performance has been well researched for several different professions. However, there is no known researches locally that have attempted to assess the job performance of administrators in public universities after they have undergone CPD training. Also, the previous studies (Dialoke & Nkechi, 2017; Oduma & Were, 2014) mostly elsewhere were on non-academic staff in general and were case studies hence their findings could not be generalized to other universities. Due to the limitations in the previous studies, this study investigates the effect of CPD on job performance of administrators in public universities. The study seeks to address specifically the following research questions:

1. Is there a relationship between CPD and job performance of public university administrators in Ghana?

2. Is there a relationship between administrators’ job performance and gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank other than CPD?

3. Does gender, age, qualification and work experience affect the CPD training of administrators?

The rest of the paper is structured as follows; Section 2 provides a review of relevant literature on CPD and job performance. The method and approach use to carry out the study are discussed in Section 3. In Section 4, result and discussion of the study are presented. Section 5 concludes the paper and made some recommendations.

Literature Review

The Concept of CPD

Change is constant and in the ever-changing work environment, it has become vital to keep up to date with new trends. CPD is therefore a panacea to stay ahead and keep up with the dynamic work environment. CPD results in superior growth, so for employees to achieve greater success in their job performance, CPD is the way to go.

According to Byars & Rue (2004), CPD is an ongoing, formalized effort by an organisation that focuses on developing and enriching the organization’s human resources to meet both the organizations and employees’ needs. Armstrong describes CPD as a lifelong process of managing learning, work, leisure and transitions in order to move toward a personally determined and evolving preferred future. CPD therefore is the process of training and developing professional knowledge and skills through independent, participation-based or interactive learning Mehta. This form of learning allows professionals to improve their capabilities with the help of certified learning. Thus, CPD courses for professionals should reflect their current expectations as well as future ambitions. As once career develops, the knowledge and skills required will also evolve. This is where CPD becomes indispensable.

CPD can only be effective when it is part of a planned process, there is a clear perspective on the improvement required, it is tailored individually to each professional and it is taught by people who have the necessary expertise, experience and skills Collins. In addition, professionals have to set their short-term and long-term objectives while undergoing a structured learning plan. They may also be required to record what they are learning and the progress they make in order to keep track of the skills and knowledge they obtain. CPD training helps professionals to stay up to date with the latest trends and learn new skills, improve their performance at work, boost their self-confidence, enhance their professional reputation and future job prospects, obtain concrete proof of their professionalism and commitment (Adanu, 2007).

CPD can take two forms-formal and informal Mehta. Formal CPD involves active and structured learning that is usually done inside or outside the organisation. Formal CPD usually consists of more than one professional, however in some cases it could just involve a single professional. Some activities in this form of structured learning include offline and online training programmes, learning-focused seminars and conferences, workshops and lectures. On the other hand, informal CPD is also known as self-directed learning, in which the professionals carry out development activities according to their own choice and without a structured syllabus. This form of learning usually consists of studying publications written by industry experts, perusing relevant case studies and articles, listening to industry-specific podcasts and following industry-specific news and studying and revising for professional exams (Adanu, 2007).

Importance of CPD for Employees and Organisations

Employees across most organizations usually opt for CPD training in order to improve their skills and knowledge in the face of challenging work environment. This is because at this level, they have already earned academic qualifications and are now working in the industry of their choice. CPD allows employees learn in a structured and practical format that boosts their overall skills and knowledge in the performance of assigned task. It also helps organizations ascertain the knowledge and skills employees need to obtain within a short time period to meet set targets and objectives of the organisation. The benefit of CPD is in two folds – to the employee and the organisation.

The benefits of CPD to employees of an organisation cannot be underestimated. Mehta has the following perspective of CPD for the employee; i) Improves intellect, personal skills and confidence; ii) Opens doors to excellent future employment opportunities; iii) Improves learning ability; iv) Promotes independent learning; v) Demonstrates ambition and commitment to professional self-improvement and vi) Relevant practical qualifications that will impress current and prospective employers. In the age of technological advancement, if administrators do not work hard to equip their knowledge, they may be trapped in their career. They may be unconfident in carrying out assigned duties and perhaps overwhelmed by currents challenges confronting higher education management. Researchers have shown that employees’ success in CPD enhances employee job delivery (Chikari et al., 2015). Adanu (2007) found some benefits derived from CPD by professional librarians in five state-owned university libraries in Ghana as job advancement and updated skills leading to competence (Wanjiku, 2016).

When it comes to the organisation, Mehta has the following as benefits of CPD; i) Allows setting of high standard across the organisation for staff development; ii) Improves productivity with the help of motivated and skilled employees; iii) Encourages a learning culture in the organisation; iv) Enhances the reputation of the company among prospective employees and clients; v) Increases employee retention; vi) Allows the company to keep up with the latest trends and changes in the industry. Mizell (2010) pointed out the following as additional benefits of CPD to organizations; vii) Help maximize staff potential by linking learning to actions and theory to practice. viii) Help human resources professionals to set specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timebound (SMART) objectives, for training activity to be more closely linked to organisation needs. ix) Promote staff development; x) Help staff to consciously apply learning to their role and the organization’s development and xi) A good tool to help employees focus their achievements throughout the year. An organization can only bring in these benefits if it supports the CPD of its employees (Kasule et al., 2016).

Relationship between CPD and Job Performance

Employee performance also known as job performance, according to Jex is all the behaviours employees engage in while at work. However, this definition seems to be patchy because a fair amount of the employees’ behaviour displayed at work is not necessarily related to job specific aspects. More commonly, job performance refers to how well an employee performs assigned task. Job performance is crucial because it is one of the key indicators of productivity in every organisation (Olsen et al., 2017; Kwon et al., 2015). Maqbali (2015) described job performance as an individual's efficiency in performing assigned tasks and duties. Milkovich defines job performance “as a function of outcomes; as a function of behaviour; as a function of personal traits”. However, most scholars are in agreement that employee dimension of performance focuses majorly on function of outcome and function of behaviour. Tzeng posits that performance is about meeting standards set or expected in one’s course of practice.

A variety of factors help with improved employee’s job performance, of which CPD plays a significant role (Owaka, 2014). CPD plays an indispensable role in getting employees in a better position to improve their job performance. Evidence of the impact of CPD on employee job performance has been presented in the literature (Lu et al., 2019; Osei et al., 2019; Hee et al., 2016; Chikari et al., 2015). Lu et al. (2019) posit that effective CPD enhances employees’ skills in order to perform their current jobs effectively as well as their attitude and knowledge to future job demands, thereby contributing to sustainable organizational performance. Also, Chikari et al. (2015) examined lecturer’s views towards CPD and the relationship between CPD and lecturer performance in Private Higher Education Institutions in Botswana with regards to variables such as gender, work experience, age and educational qualifications. The study found that lecturers viewed CPD positively and regard it as a panacea for professional growth, efficiency and teaching effectiveness. They also perceived strategies for CPD implementation as satisfactory and that a lot more with regards to stakeholder involvement was required. The study further showed that biographic characteristics such as gender, experience and qualifications had a positive relationship on lecturer performance after CPD training while age did not have a positive influence on lecturer job performance after going through CPD programmes.

Nabunya et al. (2019) examine the relationship between professional development practices and teaching, research and community service at Kampala International University and Kyambogo University. The findings were that professional development practices are significantly related with teaching service delivery but not research and community service. Oduma & Were (2014) investigated the influence of career development on both academic and non-academic staff performance in Kenyatta University. The study established that training, career mentoring, job orientation and career advancement had a positive influence on employee performance. Similarly, Dialoke & Nkechi (2017) assessed the effect of CPD on the job performance of non-academic staff of Michael Okpara University of Agriculture Umudike in Abia State, Nigeria. The study found that there is a positive and significant correlation between CPD and the job performance of the non-academic staff of the university. The study further found that career growth is positively correlated with motivation of the non-academic staff of the university. The researchers concluded that the impact of career growth on the performance and motivation of employees in the university cannot be succinctly stated and recommends that in harmony with the programmes and policies of the university, management should not relent in contributing to the career growth of the non-academic staff.

Osei et al. (2019) examined the relationship between CPD and job performance of registered nurses in Ghana. The study found a moderate positive significant relationship between CPD and job performance of nurses in Ghana. Further, the study demonstrated that there is no significant difference in job performance of nurses when age, sex and clinical experience are considered. In contrast, Bakhshi & Kalantari (2017) found that there is a significant relationship between sex and job performance, however, there was no significant difference in gender and job performance of nurses. Also, Gaki et al. (2013) found a significant difference in job performance of nurses when age and work experience are considered. Similarly, AlMakhaita et al. (2014) found a significant difference in the clinical experience of registered nurses in relation to job performance.

It can be deduced from the previous studies that there are empirical studies done on the impact of CPD on employees’ job performance and these have focused mostly on different professions with little evidence on university administrators (Agala-Mulwa, 2002). Further, there is no known studies that has investigated the impact of CPD on administrator’s job performance in the public universities in Ghana. This study therefore seeks to fill the research gaps by investigating the impact of CPD on administrators’ job performance in the public universities in Ghana. The significant of this study is that, it will influence the development of effective policies and strategies for implementing CPD for administrators in public universities and beyond.

Methodology

The study used a quantitative research approach to investigate the effect of CPD on the job performance of public universities administrators. The population was administrators from the ten public universities in the country which numbered one thousand one hundred twenty-five (1,125). The study employed stratified random sampling design because it provided an efficient system of capturing each subgroup proportionately. To obtain the sample size from each of the ten universities, administrators were then randomly selected from all cadres of administrators as shown in Table 1. The total sample size determined from all the ten public universities was three hundred (300) administrators which represent 26.7% of the population.

| Table 1 Population and Sample Size |

||

|---|---|---|

| University | Population size (N) | Sample Size (n) |

| A | 238 | 63 |

| B | 180 | 48 |

| C | 153 | 41 |

| D | 141 | 38 |

| E | 137 | 37 |

| F | 103 | 27 |

| G | 63 | 17 |

| H | 49 | 13 |

| I | 41 | 11 |

| J | 20 | 5 |

| Total | 1,125 | 300 |

Source: Authors’ calculations with information from GAUA.

| Table 2 Relationship Between Cpd And Job Performance (Jp) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| CPD | JP | ||

| CPD | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.347** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | ||

| N | 268 | 268 | |

| JP | Pearson Correlation | 0.347** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | ||

| N | 268 | 268 | |

| **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). | |||

The number of sampled units in each stratum is proportional to the size of the stratum. The probability of selection is the same for all strata. In choosing a sample that is representative for each stratum, proportional allocation is used. The sample size for each stratum is mathematically chosen using the formula;

where n is the sample size for the population,Nh is the sum of stratum frame.

where n is the sample size for the population,Nh is the sum of stratum frame.

A self-constructed survey questionnaire was the main data collection instrument in this study. Part A of the survey instrument sought for demographic characteristics of administrators such as gender, age, qualification, work experience, etc. while parts B, C and D sought to find out the awareness and involvement in CPD training, reasons for CPD and effect of CPD on the job performance of administrators in public universities respectively. The questionnaire was externally validated to ensure that all relevant constructs are included. The reliability and internal consistency of the survey instrument were measured using Cronbach Alpha. The Cronbach’s Alpha is used to check whether the information obtained through a survey are reliable for analysis. Literature suggests that an alpha value of 0.700 or more is acceptable (Bagozzi & Yi, 2012). The result gives Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.733 for question items pertaining to CPD. For question items pertaining to job performance the Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.789.

Due to the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), the questionnaire could not be administered face to face. Instead, the administrators were approached via on-line Google form. The researchers explained the purpose and procedure of the study before directing the respondent to the questionnaire. The questionnaires were collected via on-line after completion. Administrators’ privacy was protected by providing anonymous and voluntary participation. Participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any stage. Furthermore, the identities of the participants were not disclosed and only aggregate data were presented. Ethical consideration was taken into account during the study. The statistical analyses used to address the research questions and hypotheses were Pearson Correlation Coefficients and linear regression.

Results and Discussions

The study sought the level of awareness and involvement of public university administrators in CPD. The result showed that administrators are very much aware of the CPD in the university as 76.5% indicated so confirming Chikari et al. (2015)’s findings that CPD is widely acknowledged to be of great importance in every organisation, contributing to professional and personal development for staff (both teaching and non-teaching) and helping achieve the university set targets and objectives. The study further found that administrators were involved in CPD as 97.4% indicated they have attended at least one CPD training since joining the university. Greater funding for CPD was from the employer with 49.6% indicating so, while 26.9% indicated they self-financed their CPD training. On how often administrators undergo CPD training, majority representing 54.8% indicated there are no specific schedule, while 27.2% indicated they undergo training once in a year. Majority of the administrators had their CPD training off-the-job with 40.7% indicating so, while 28.0% and 26.8% had it on-the-job and through in-service training respectively.

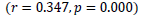

Using Pearson Correlation Coefficient, the relationship between CPD and job performance of public university administrators was examined. It was found that there exists a moderately positive significant relationship  between CPD and job performance of public university administrators at 99% confidence interval. This implies that administrators job performance increases with increase in CPD training. To support these findings Mizell (2010) argues that CPD is the only way administrators can learn so that they are able to increase their performance and meet the university set targets and objectives.

between CPD and job performance of public university administrators at 99% confidence interval. This implies that administrators job performance increases with increase in CPD training. To support these findings Mizell (2010) argues that CPD is the only way administrators can learn so that they are able to increase their performance and meet the university set targets and objectives.

The result further indicates that the administrators after undergoing CPD training, they practice what they have learned to increase their performance at the university. Thus, the study rejects the null hypothesis that there is no significant relationship between CPD and job performance. Employing regression analysis, the study further sought to investigate whether there exists a relationship between administrators’ job performance and gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank other than CPD. Table 3 presents the regression result.

| Table 3 Effect Of Cpd, Gender, Age, Qualification And Work Experience On Job Performance |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) |

| (Intercept) | 2.94397 | 0.58950 | 4.994 | 1.11e-06 *** |

| CPD | 0.30885 | 0.06144 | 5.027 | 9.52e-07 *** |

| SexMale | 0.04069 | 0.05940 | 0.685 | 0.4940 |

| age20-29 years | 0.22261 | 0.40092 | 0.555 | 0.5792 |

| age30-39 years | 0.04129 | 0.39234 | 0.105 | 0.9163 |

| age40-49 years | -0.13667 | 0.38957 | -0.351 | 0.7260 |

| age50-59 years | 0.08547 | 0.39587 | 0.216 | 0.8292 |

| Age60 years and above | 0.21313 | 0.51618 | 0.413 | 0.6800 |

| qualifiDoctoral degree | -0.22308 | 0.43694 | -0.511 | 0.6101 |

| qualifiMaster;s degree | -0.23135 | 0.39151 | -0.591 | 0.5551 |

| Qualifiother | -0.27596 | 0.42825 | -0.644 | 0.5199 |

| Lengthroles2-4 years | 0.06018 | 0.11512 | 0.523 | 0.6016 |

| lengthrole5-7 years | 0.41619 | 0.13935 | 2.987 | 0.0031** |

| lengthrole8-10 years | 0.23892 | 0.15620 | 1.530 | 0.1274 |

| lengthroleAbove 10 years | 0.03587 | 0.16836 | 0.213 | 0.8315 |

| rankAsst. Registrar/Equivalent | 0.06693 | 0.34255 | 0.195 | 0.8452 |

| rankDeputy Registrar/Equivalent | 0.49203 | 0.35577 | 1.383 | 0.1679 |

| rankJunior Asst.Registrar/Equivalent | 0.02493 | 0.36072 | 0.069 | 0.9449 |

| rankSenior Asst.Registrar/Equivalent | 0.24771 | 0.34185 | 0.725 | 0.4694 |

Signif. Codes: 0 "***" 0.001 "**" 0.01 "*" 0.05 "." 0.1 ""1

Residual standard error: 0.4584 on 249 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-Squared@: 0.2673, Adjusted R-Squared: 0.2143

F-Statistic: 5.047 on 18 and 249 DF, p-value: 9.096e-10.

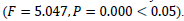

The results in Table 3 showed that CPD, gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank together explained 28% of the variation in job performance  This means that 72% of the variation was accounted for by extraneous variables. The regression model was relatively good

This means that 72% of the variation was accounted for by extraneous variables. The regression model was relatively good  This implied that job performance was moderately predicted by CPD, gender, age, qualification and work experience. Particularly, CPD and length of role (work experience) 5-7 years have their p-values low (<0.05) and this supports the alternative hypothesis that their coefficients are significant. This means CPD offered to public administrators has a high positive significant relationship with job performance of administrators. Once CPD training is provided and as administrators get some level of experience their job performance enhances. However, gender, age, qualification and rank each has a higher p-value ( >0.05) and this support the null hypothesis that each coefficient is insignificant, suggesting that they do not impact significantly on administrators’ job performance.

This implied that job performance was moderately predicted by CPD, gender, age, qualification and work experience. Particularly, CPD and length of role (work experience) 5-7 years have their p-values low (<0.05) and this supports the alternative hypothesis that their coefficients are significant. This means CPD offered to public administrators has a high positive significant relationship with job performance of administrators. Once CPD training is provided and as administrators get some level of experience their job performance enhances. However, gender, age, qualification and rank each has a higher p-value ( >0.05) and this support the null hypothesis that each coefficient is insignificant, suggesting that they do not impact significantly on administrators’ job performance.

Through regression analysis, we also investigated whether gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank affect the CPD training of administrators. The result is presented in Table 4.

| Table 4 Effect Of Gender, Age, Qualification And Work Experience On Cpd Training |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | Estimate | Std. Error | t value | Pr(>|t|) |

| (Intercept) | 4.492706 | 0.536237 | 8.378 | 3.91e-15*** |

| SexMale | -0.038992 | 0.061102 | -0.638 | 0.524 |

| age20-29 years | 0.239473 | 0.403866 | 0.581 | 0.562 |

| age30-39 years | 0.08451 | 0.401051 | 0.209 | 0.835 |

| age40-49 years | 0.011699 | 0.407535 | 0.029 | 0.977 |

| age50-59 years | -0.007027 | 0.530508 | -0.017 | 0.986 |

| Age60 years and above | 0.485011 | 0.530508 | 0.914 | 0.361 |

| Qualify Doctoral degree | -0.016224 | 0.449812 | -0.036 | 0.971 |

| Qualify Master’s degree | 0.134519 | 0.402961 | 0.334 | 0.739 |

| Qualify other | 0.107527 | 0.440820 | 0.244 | 0.807 |

| Length roles 2-4 years | 0.091202 | 0.118371 | 0.770 | 0.442 |

| Length roles 5-7 years | 0.206800 | 0.142861 | 1.448 | 0.149 |

| Length roles 8-10 years | 0.139052 | 0.160561 | 0.866 | 0.387 |

| Length roles Above 10 years | -0.105326 | 0.173194 | -0.608 | 0.544 |

| Rank Asst. Registrar/Equivalent | -0.200820 | 0.352415 | -0.570 | 0.569 |

| Rank Deputy Registrar/Equivalent | 0.064608 | 0.366229 | 0.176 | 0.860 |

| Rank Junior Asst. Registrar/Equivalent | -0.399365 | 0.370487 | -1.078 | 0.282 |

| Rank Senior Asst. Registrar/Equivalent | -0.149957 | 0.351798 | -0.426 | 0.670 |

Signif. Codes: 0 "***" 0.001 "**" 0.01 "*" 0.05 "." 0.1 ""1

Residual standard error: 0.4719 on 250 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-Squared@: 0.07851, Adjusted R-Squared: 0.01585

F-Statistic: 1.253 on 17 and 250 DF, p-value: 0.2242.

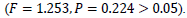

The results in Table 4 showed that gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank explained 8% of the variation in CPD This means that 92% of the variation is accounted for by other factors not considered in the study. The regression model was poorly fit

This means that 92% of the variation is accounted for by other factors not considered in the study. The regression model was poorly fit  This suggested that CPD was insignificantly predicted by gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank combined. Furthermore, the p-values are high (>0.05) and this also supports the null hypothesis that each coefficient is insignificant. This implies that gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank may not exactly impact on CPD training of public university administrators. Thus, regardless of gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank, administrators will need to undergo

This suggested that CPD was insignificantly predicted by gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank combined. Furthermore, the p-values are high (>0.05) and this also supports the null hypothesis that each coefficient is insignificant. This implies that gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank may not exactly impact on CPD training of public university administrators. Thus, regardless of gender, age, qualification, work experience and rank, administrators will need to undergo

Conclusion

The study showed that there was a moderate positive relationship between CPD and job performance of public university administrators. This indicated that administrators who received CPD trainings were better positioned to deliver superior performance. University authorities should encourage and advocate for the participation of administrators in continuous learning at all times to improve administrator’s knowledge and skills on university administration. Institution policies should be properly aligned to help administrators in the participation of professional training. Further research should explore other variables that impact on CPD and job performance of public university administrators.

References

Adanu, T.S. (2007). Continuing professional development in state-owned university libraries in Ghana. Library Management Journal, 28(6), 292-305.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Akeke, N.I., Akeke, A.R., & Awolusi, O.D. (2015). The effect of job satisfaction on organizational commitment among non-academic staff of tertiary institutions in Ekiti State.International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research Method,2(1), 25-39.

AlMakhaita, H.M., Sabra, A.A., & Hafez, A.S. (2014). Job performance among nurses working in two different health care levels, Eastern Saudi Arabia: a comparative study.International Journal of Medical Science and Public Health,3(7), 832-837.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bakhshi, E., & Kalantari, R. (2017). Investigation of quality of work life and its relationship with job performance in health care workers.Journal of Occupational Hygiene Engineering,3(4), 31-37.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Byars, L.L., & Rue, L.W. (2004). Human Resource Management. Boston M.A: McGraw-Hill Irwin Publishers.

Chikari, G., Rudhumbu, N., & Svotwa, D. (2015). Institutional Continuous Professional Development as a Tool for Improving Lecturer Performance in Private Higher Education Institutes in Botswana. International Journal of Higher Education Management, 2(1), 26-39.

Dialoke, I., & Nkechi, P.A.J. (2017). Effects of career growth on employees performance: A study of non-academic staff of Michael Okpara University of Agriculture Umudike Abia State, Nigeria.Singaporean Journal of Business Economics, and Management Studies (SJBEM),5(7), 8-18.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gaki, E., Kontodimopoulos, N., & Niakas, D. (2013). Investigating demographic, work?related and job satisfaction variables as predictors of motivation in Greek nurses.Journal of Nursing Management,21(3), 483-490.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hee, O.C., Kamaludin, N.H., & Ping, L L. (2016). Motivation and Job performance among nurses in the health tourism hospital in Malaysia.International Review of Management and Marketing,6(4), 668-672.

Kasule, G.W., Wesselink, R., & Mulder, M. (2016). Professional development status of teaching staff in a Ugandan public university.Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management,38(4), 434-447.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kwon, M.S., Yang, S.O., & Eom, S.O. (2015). Job performance and self-confidence by visiting nurses who are engaged in the consolidated health promotion program in Gangwon-province. Journal of Korean Public Health Nursing, 29(2), 190-202.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lu, H., Zhao, Y., & While, A. (2019). Job satisfaction among hospital nurses: A literature review.International Journal of Nursing Studies,94, 21-31.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Maqbali, M.A. (2015). Factors that influence nurses’ job satisfaction: a literature review. Nursing Management 22(2), 30-37.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mizell, H. (2010). Why Professional Development Matters. Oxford: Learning Forward.

Nabunya, K., Mukwenda, H.T., & Kyaligonza, R. (2019). Professional development practices and service delivery of academic staff at Kampala International University and Kyambogo University.Makerere Journal of Higher Education,10(2), 133-143.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nawi, N.C., Ismail, M., Ibrahim, M.A.H., Raston, N.A., Zamzamin, Z.Z., & Jaini, A. (2016). Job satisfaction among academic and non-academic staff in public universities in Malaysia: A review.International Journal of Business and Management,11(9), 148-153.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Oduma, C., & Were, S. (2014). Influence of career development on employee performance in the public university: A case of Kenyatta University.International Journal of Social Sciences Management and Entrepreneurship,1(2), 1-16.

Olsen, E., Bjaalid, G., & Mikkelsen, A. (2017). Work climate and the mediating role of workplace bullying related to job performance, job satisfaction, and work ability: A study among hospital nurses.Journal of Advanced Nursing,73(11), 2709-2719.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ummah, S., & Athambawa, S. (2018). Organizational citizenship behavior and job satisfaction among non-academic employees of national universities in the Eastern province of Sri Lanka.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wanjiku, W.G. (2016). Factors affecting non-teaching staff development in Kenyan Universities.International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences,6(5), 104-130.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 22-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. AAFSJ-22-12230; Editor assigned: 24-Jun-2022, PreQC No. AAFSJ-22-12230(PQ); Reviewed: 08-Jul-2022, QC No. AAFSJ-22-12230; Revised: 27-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. AAFSJ-22-12230(R); Published: 03-Aug-2022