Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 4

Effect Of Brand Personality On Consumer Product Choice In The Telecoms Industry

Ladipo, P.K.A., University of Lagos, N

Mordi, K.I. University of Lagos, Nigeria

Iheanacho, A.O. University of Nigeria

Abstract

This study investigated brand personality and consumer product choice in the Nigerian telecommunications industry. The study employed cross-sectional research design to survey 277 subscribers on the networks of four mobile telecom operators (MTN Telecommunications Limited, AirtelP Nigeria, Glo Mobile Telecommunication and 9Mobile). The respondents were selected through convenience sampling approach. All the five dimensions of brand personality (sophistication, excitement, ruggedness, sincerity, and competence) were found to be associated with and predicted consumer product selection. Based on the findings, the study concluded that firm’s choice of brand personality should be based on tactics that can invoke positive brand association so as to enhance consumer product selection and choice decisions. The study recommended that business organizations should critically evaluate changing personality traits and identify the brand’s personality that will covey the right message to the customers through his or her personality to stimulate consumer desire and purchase for the company’s brands. This study filled a very significant gap in literature by employing a cross-sectional descriptive research design to investigate the association of brand personality with consumer product selection in the Nigerian telecommunication industry. The outcome of this study can be used as a practical marketing framework for brand managers in the telecommunication industry to build strong brand personality.

Keywords

Sophistication, Excitement, Competence, Sincerity, Ruggedness, Brand Personality, Consumer Product Selection.

Introduction

The growth in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in both developed and developing nations has spurs rising interest and usage of mobile telecommunication. The upsurge in the use of Global System for Mobile communications (GSM) in Nigeria since its introduction in August, 2001 has conveyed extraordinary transformations in the telecom industry. Following the aforementioned development, a number of telecom operators have adopted a number of strategies to promote their brands. In particular, the growing interest in the use of important personality such as artist, sportsperson, politicians, top academicians and successful business people to promote a brand is growing. This is founded on the belief that consumers may be influence by the personality of such people. The growing product homogeneity and similarity in the pattern of service delivery in today’s globalized world have compelled business organizations to adopt different marketing tactics that will make them distinctive from competitors.

A number of businesses, for instance have used famous athletes’, politicians or Nollywood actors/actresses that are well respected by the public to build their brand image.

According to Wong, Kwok, and Lau (2015), the attitudes and behaviors of some famous sports person have attracted wider citizenry and thus, they consider those sport personality as dynamic with good qualities. In contemporary era, people purchase goods not only for what they can accomplish from consuming or using it but also for what such products symbolize (Maehle, Otnes, & Supphellen, 2011; Chinedu, Onuoha, & Onuegbu, 2016). As a result, the focus of marketers and brand executives shift from product features or attributes to the notion of brand personality (Heine, 2009).

Brand personality has been observed as instrumental and descriptive issues in identifying the inclinations, attitudes and intentions of consumers, and developing their brand loyalty (Ahmed, & Jan, 2015; Karjaluoto, Munnukka, & Salmi, 2016). Brand personality is a multidimensional notion consisting of five elements namely, excitement, sophistication, ruggedness, competence and sincerity. These dimensions were popularized by Aaker (1997). According to Sundar and Noseworthy (2016), the dimensions’ highlight how consumers perceive a brand. Since the recognition of brand personality in academia, Aaker’s (1997) brand personality dimensions have been the most widely used scale in a number of studies across diverse culture, nations and product classifications (Vahdati & Nejad, 2016).

Marketing ideologies and practices have significantly evolved over the years and so have the dynamics connecting brands and consumer behavior. Branding is a vital issue in this context, because consumers, regardless of being early or late adopter, constructively choose existing brands (vs. new) on the basis of tangible and intangible attributes one of which is brand personality (Truong, Klink, Simmons, Grinstein, & Palmer, 2017). Brands perform a vital role in simplifying and influencing consumer’s choice process. Individuals are commonly in search for valuable short-cuts in decision-making concerning a product/service and companies to patronize. The above scenario may result into approach which mostly rely on habits, but can also be founded on perceptions about brand image or people that promote it. In other words, such perceptions may be influenced not only from firm’s marketing or promotion campaign; but also from personality attached to the brands (Doyle, 1998).

Statement of the Problem

There is need for business organizations to realize that their products and services, irrespective of how good they might be, may not simply sell on their own (Kotler & Keller, 2012). This is because companies are facing huge competition from so many substitutes readily available; therefore, company must develop distinctive approaches to differentiate their products or service in the eyes of the target market. This chain of events has prompted many scholars and firms to consider the connection of brand personality to consumer choice decision (Park. Maclnnis, Priester, Eisingerich, & Laccoucci, 2010; Ang & Lim, 2013; Kim, Vaidyanathan, Chang & Stoel, 2017). Other challenges include the overall proliferation of media and distribution networks, decreasing trust in advertising, and the manifestation of digital technologies that give consumers more control. These developments instantaneously fragment both audiences and the media required to reach the target market (Pessemier, 2012). Besides, deterioration in the effectiveness of mass advertising through newspapers, radio or television among others is another major signs of distress that marketers are confronted with.

Companies, therefore, need to shift their focus from mass marketing and concentrate attention on tailoring a brand message that demonstrates brand personality that enable consumers easily differentiate one brand from other competing products.

As a direct consequence, branding has ascended as a fundamental feature of contemporary marketing practices and is presently deliberated a major firm resource (Kotler & Keller, 2012). Understanding consumers’ choice decision is one of the most vital goals in marketing; however, examining consumers’ choice decision is a complicated task to the extent that there seem to be incongruity across disciplines on the best method to study it. Nevertheless, the traditional techniques are often inadequate to analyze and study consumer behavior due to numerous unconscious mental procedures, and inability to make inform decision when confronted with diverse product choices (Letizia, Efthymios, & Massimo, 2018). As a result, these advances have diminished the capability of innovative developments to provide sustainable competitive advantage and have made product differentiation remarkably difficult (Levitt, 1983)

Although the use of personality to promote brands have gained huge recognition, however, previous research advocated that personality perceptions may differ by product category and diverse settings, and that explicit brand personality dimensions are connected with specific product classifications (Kaplan, Yurt, Guneri, & Kurtulus, 2010; Kim et al., 2017). Austin, Siguaw, and Mttila (2003) contended that it would be incorrect to associate certain traits (“sentimental” and “sincere”) of human personality with brands. Another stimulating dispute about the anthropomorphism in brand personality and the way it is conceptualized is that its meaning is too compressive and its scope needs to be delimited to the level it can be sufficiently applied to brands (Azoulay & Kapferer, 2003).

Numerous research studies on brand personality that have been done (Anisimova, 2007; Xu et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2017). However, the influence of brand personality on brand prominence and consumer choice decision effects may not be permanent in nature, because selfperceptions are transformed irrespective of whether the brand experience is short-lived or repeated over time (Austin et al., (2003). Scholars have contended that brands actually do have personalities (Aaker, 1999; Beldona & Wysong, 2007), nevertheless there has been little research attention on how to establish whether or not customers seek a brand with a personality based on the circumstances (Sung, 2011). Similarly, bulk of these prior studies focused attention on the theoretical element that describe and offer an understanding of brand personality, ignoring a comprehensive knowledge gap that marketers need to understand about the association between brand personality dimensions and brand choice (Anisimova, 2007; Freling & Forbes, 2005). Consequently, there is inadequate knowledge to guide the development of brand personalities that guide consumer brand choice. Against the aforementioned research background, this study attempt to study the effect of brand personality on consumer product choice in the Nigeria telecoms industry.

The broad objective of the study is to determine the relationship between brand personality and consumer product selection. The specific objectives are to determine the relationship between sophistication as a dimension of brand personality and product selection in the Nigeria telecommunications industry; to investigate the relationship between sincerity as a dimension of brand personality and product selection in the Nigeria telecommunications industry; to determine the relationship between excitement as a dimension of brand personality and product selection in the Nigeria telecommunications industry;to determine the relationship between competence as a dimension of brand personality and product selection in the Nigeria telecommunications industry and o determine the relationship between ruggedness as a dimension of brand personality and product selection in the Nigeria telecommunications industry.

Research Hypotheses

Three hypotheses were raised

1) There is no significant relationship between sophistication as a dimension of brand personality and product selection.

2) There is no significant relationship between sincerity as a dimension of brand personality and product selection.

3) There is no significant relationship between excitement as a dimension of brand personality and product selection.

4) There is no significant relationship between competence as a dimension of brand personality and product selection.

5) There is no significant relationship between ruggedness as a dimension of brand personality and product selection.

Review of Related Literatures

Theoretical Framework

The two theories that underpinned this theory are:

Human Communication and Signal Perception Theory

Signaling theory elucidates that, in a context of information asymmetry, the knowledge holder (in this context, the firm) may not wish to offer the other party (herein refer to as the actual or potential customer, employee or other stakeholder) with adequate information and instead uses one or more signals to communicate (Spence, 1973). Signaling theory is harmonious with the impression that brand meaning is co-created between company and customer (von Wallpach, Voyer, Kastanakis, & Muhbacher, 2017). Signaling theory does not openly encompass identifying a typology of signals and does not describe which signals are most pertinent to brands and for this some scholars proposed stereotype content model (Fiske, Cuddy, & Glick, 2007) which postulates warmth/sincerity, competence and status as central to humans and which has been stretched to corporate and brand imagery (Aaker, Vohs, & Mogilner, 2010).

The Theory of the Extended Self

The theory of the ‘extended self’ developed upholds that possessions are foremost contributor to and replication of our identities (Belk, 1988). Therefore, brand personality permits consumers to identify themselves with a brand and to definite their own personality through the brand (Azoulay & Kapferer, 2003). Based on the theory of extended self, consumers purchase and use brands to fulfil their needs, to develop, strengthen, and communicate their personalities, and to form their self–brand networks which facilitate consumer’s expression of their actual or ideal self (Sung & Kim, 2010).

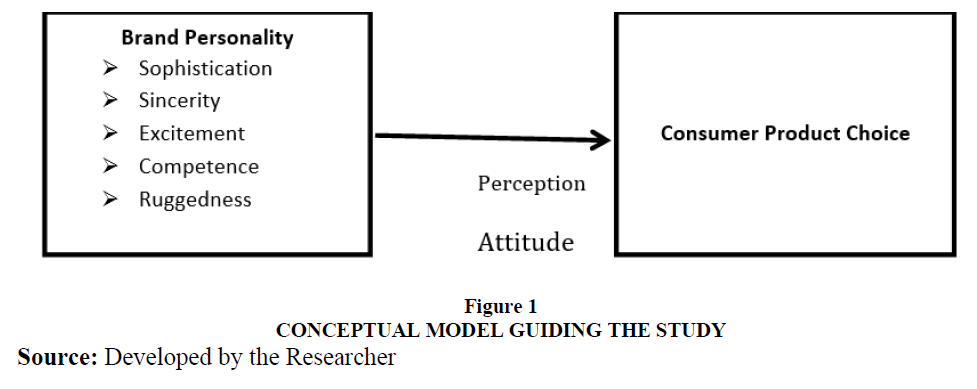

Conceptual Model

The conceptual model guiding this study is depicted in Figure 1 below.

Measurement and Dimensions of Brand Personality

The notion of brand personality was coined in 1955 (Avis, Aitken, & Ferguson, 2012) and has been progressing through contribution from numerous field of endeavors, such as retailing, advertising and entertainment to mention a few. The slowness in the domain of brand personality was rejuvenated by Aaker (1997) when she developed a scale (brand personality scale – BPS) for its measurement. Brand personality has long been acknowledged as part of the branding theory. There are multiplicities of definitions of brand personality. The most extensively quoted definition of brand personality, define it as the set of human attributes connected with a brand’ (Aaker, 1997). Azoulay and Kapferer (2003) conceptualized brand personality as a set of comparatively enduring human features that are suitable and appropriate to the explanation of social media.

Using big-five human personality typology, Aaker (1997) advocated a “brand personality scale,” consisting of five dimensions: sophistication, sincerity, excitement, competence and ruggedness. Aaker’s brand personality framework has three dimensions that are connected to the ‘big five’ human dimensions. As expressed by Aaker (1997), sincerity, excitement, and competence pass over into human personality because they were established to be linked with agreeableness, extraversion, and conscientiousness, which are fundamentals of the ‘big five’ notion (Mulyanegra & Tsaranko, 2009). The other two dimensions, sophistication and ruggedness, are not associated with personality traits, but echo individuals desire but not essentially essential brand elements they lack or possess (Aaker 1997). According to Okazaki (2006), the five brand elements are multidimensional concepts that also form a major building block from which the brand measurement scale is developed. Sincerity echoes truthful, honest, cheery.. Naresh (2012) viewed sincerity as the level to which the brand personality is welcoming, cheery and honest. Excitement evaluates openness, imaginative, and lively of brand personality (Lin, 2010). In the opinion of Aaker (1997) and Ramaseshan (2007) excitement involves features such as being current, enterprising, and creative. Competence denotes how accountable, dependable, resourceful, and smart a brand personality is (Aaker, 1997). Sophistication outlines the level of elegance, fashionable, delightful, passionate and charm with which a brand is gifted (Lin, 2010). Ruggedness, according to Aaker (1997) refers to the level forte, classy, and functional a brand is perceived to be.

Although Aaker (1997) brand personality framework constitutes the foundation of a number of studies on brand personality, a number of scholars have highlighted some of its drawbacks. The first inherent limitation of Aaker’s 1997 typology is the absence of cultural generalisability (Austin et al., 2003; Ahmad & Thyagaraj, 2014). Aaker model has also been condemned for failure to highlight the dimensions of her of model with an accurate description which poses a construct validity challenge (Anandkumar & George, 2011; Kumar & Kumar, 2014). Others academics such as Huang, Mitchell, and Rosenaum-Elliot (2012) and Kang and Park (2016) stated that measures designed to evaluate human personality can be adopted to measure brand personality, but Caprara, Barbaranelli, and Guido (2001) stated that there are essential variances between the two. On the basis of the aforementioned shortcomings of Aaker framework stream of research has reexamined the generalisability of the dimensions proposed by Aaker’s. Accordingly, Albert, Merunka, and Valette-Florence (2008) promoted a new scale named brand personality barometer by using only those traits that are appropriate for brands. Similarly, Sweeney and Brandon (2006) stated that only human traits that relate to the interpersonal and relationship-based attributes of human personality should be consider relevant to brand personality. Eisend and Stokburger-Sauer (2013) proposed hedonic benefit as a major element of brand personality.

An Overview of Consumer Product Selection

The most fundamental environment in which business organizations operate is their customer environment because the intricate belief of marketing oriented firm is that the customer is at the centre of their business. Therefore, business organizations need to understand the procedures that their customers go through when making decision concerning a product/service or where to buy from. Consumer drives, consumption circumstances, consumer prefer product features and availability of substitutes can be designated as exogenous influences, which could be mutually regarded as frames for the choice. Consumer engages in decisions all the time. Some purchase decisions are reflex in nature such as complying with traffic lights or taking breakfast, etc. Some decisions can be labelled as semi-automatic; they can be categorized as routines, but not completely automatic, for instance selecting clothes to put on, choice of menu etc. Some decision entail highly deliberated processes such buying a house, selecting a vacation destination, etc. Decision-making theorists seem to fundamentally agree on the stages in the choice process (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981; Bettman, Luce, Payne, 1998). In other words, even though a number of decisions seem quite diverse, the decision-making procedure is similar.

The consumer decision making procedure encompasses series of connected and successive phases. The procedure starts with problem recognition which is the detection of an unsatisfied desire which eventually becomes a drive that propel search effort for information. The search which is the third stage results to numerous alternatives product choice decisions; follow by the purchase decision made. The last stage is post purchase behavior and it is phase is where the buyer assesses the post purchase behavior based on anticipated benefits and the level of satisfaction derives from consuming or using a product/service.

Due to limited cognitive capacities and aspiration to lessen decision-making costs and time, some heuristics are usually used in decision-making. Besides, heuristics, consumers may attempt to contemplate all conceivable options and features (to engage in a so-called rational decision) or decide spontaneously or nearly repeatedly. Diverse decision-making approaches necessitate different level of consumers’ time, effort and attention. Thus, the complication of decision task has a direct impact on peoples’ choices. Bettman et al. (1998) stated that if a decision task is more difficult, people simplify their decision making accordingly and use modest heuristics guidelines.

Linking Brand Personality to Consumer Product Selection

The meaning and impression consumers attach towards a brand is very fundamental to consumer decision making. According to McCracken (1986), consumers are looking for brands whose cultural senses match with the person they are or they aspire to be. In other words, people are more interested in products that fit to their personal or ideal self-concept. Without a doubt, the sense that exist in brands or the consumption process itself activate consumers’ purchase of certain brands compare to others (McCracken, 1986; Arnould, Price, & Zinkhan, 2005).

Nonetheless, in other to distinguish one’s product/service from another, the experiential or symbolic meaning of a brand becomes more vital (McCracken, 1986). Brands obtain an experiential sense if they are connected with specific emotional state (Arnould et al., 2005). Brands can also have a symbolic meaning which implies that they become a framework of social interface and communication (Kim & Sung, 2013). Generally, if consumer perceives a fit between his own self-concept and the brand’s personality, that brand becomes an indicative symbol to the consumer’s (Maehle et al., 2011).

Empirical Review

Research carried out by Heine (2009) examined the influence of feeling and involvement on the association between brand personality, consumer personality and brand association on the basis of the self-identity, the study reported that consumers were using symbolic meanings of the brands to reflect their self-identities. Another stream of studies has focused on the predictive influence of brand personality on a number of outcomes such as consumer-brand associations (Carlson, Donavan, & Cumiskey, 2009); and self-image similarity and functional congruity (Su & Tong, 2017). Research conducted by Escalas and Bettman (2005) investigated why consumers prefer brands with attractive personalities. The results show that consumers prefer and choose brands with likeable personalities in an attempt to confirm and boost a sense of self. According to Kotler and Keller (2012), the tendency of customers, selecting the brands, which attune to their self-image is consistent. Plummer (2000) stated that brand personality is very fundamental to the understanding the choice of brands consumers purchase. A research carried out by Aaker, Founier, and Brasel (2004) on “when good brands do bad” discovered that sincere and exciting brand personalities dimensions’ merit attention in view of their prominence in the marketing context. Sung and Kim (2010) reported a connection between brand personality traits, comprising sincerity and excitement in particular, and brand trust.

Research Method

Research Design

Research design is a plan, structure and strategy of investigation aimed at providing answers to research questions and controlled variances. Research design is classified into: descriptive, causal or experimental and exploratory. For the purpose of this study, descriptive research design was employed and data collected through cross-sectional survey method. Mugenda and Mugenda (2010) stated that descriptive survey permits researcher to collect quantitative data in an objective way without manipulating the respondents.

Population of the Study

In respect of this study comprising 4 major telecom companies. The population of this study consists of subscribers across the 4 major mobile telecom operators, namely, Airetel, MTN, Glo and 9Mobile. Although the population across the 4 mobile operators is given at 23,565,388 subscribers (National Bureau of Statistics, 2019). However, a typical subscriber will be having up to 3 subscriber Identification Module-SIM cards, therefore, the population becomes rather infinite.

Sample Size and Selection Procedure

Daniel (1999) sample size computation formula was used to compute the sample size. The formula is:

Where:

n = Sample Size

Z = 1.96

e = 0.05

q = 0.3

p = 0.7

p+q = 1

From the above equation, the sample size is estimated to be 420 respondents that will be involved in this study. The sample size was determined from the entire population for data collection employing convenience sampling method.

Instrumentation

Instrumentation refers to the data collection instrument which for the purpose of this study is a structured questionnaire design. The instrument was designed to provide multiple answers or responses. The questionnaire format is known as close ended questionnaire and take the form of 5-point Likert scale. The choice of the instrument is influenced by its simplicity in nature and the ability to generate higher response rate than open ended questionnaire design. A five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (tag 1) to strongly agree (tag 5) was used.

This study adapted Aaker (1997) five dimensional structure of brand equity consisting of sophistication, sincerity, excitement, competence and ruggedness to examine brand personlaity. This study will adopt the measures from the questionnaire developed by Zhou, Arnold, Pereira, and Yu (2010) to evaluate consumer product choice. In this study, the method of data collection is based on self-administration technique.

Pilot Study of the Instrument

The instrument prior to its use was subjected to a pilot study to carry out the tests of validity and reliability. Validity itself is a measure of the accuracy of the instrument in measuring variables of research interests. Reliability, on the other hand, measures the consistency of the instrument measuring variables of research interest. Face and content validity was carried out by giving the instrument to experts for their inputs which provided immense opportunity in putting together the final draft. Reliability was assessed through Cronbach alpha coefficient to determine the internal consistency of the instrument. To assess the reliability, Cronbach alpha coefficients were computed for the variables and dimensions that make up the study Table 1.

| Table 1 Reliability Test (N = 20) | ||

| Variables | No. of items | Coefficient alpha (α) |

| Sophistication | 6 | 0.911 |

| Sincerity | 6 | 0.676 |

| Excitement | 6 | 0.769 |

| Competence | 6 | 0.897 |

| Ruggedness | 6 | 0.793 |

| Consumer Product Selection | 11 | 0.822 |

While diverse opinions have been advanced concerning the level of acceptance of Cronbach alpha level, Hair, Black, Babin, and Anderson (2010) stated that an alpha of .60 and over is acceptable. From the foregoing, the Cronbach alpha values for all the two variables and dimensions are above the cut-off point of (α=0.60), thus, all the measurement scales are reliable.

Questionnaire Administration and Response Rate

A survey of participants who are subscribers of 4 major telecom operators was conducted for four weeks (i.e. 14th of September, 2020 to 12th of October, 2020). Three Hundred and Seven copies of questionnaire were distributed to respondents who are subscribers of 4 telecom companies. Table 2 shows summary of the questionnaire distribution and response rate. With a targeted 420 respondents, a total of 307 copies of questionnaires were distributed, 21 copies of questionnaire were partially filled while 9 copies were made of multiple responses across the sections of the questionnaire. All the 30 copies of questionnaires based on the above-mentioned problems were discarded from further analysis. From the above figures, only 277 respondents that comprehensively filled the questionnaire were usable for further statistical analysis, resulting to response rate of 90.23%.

| Table 2 Questionnaire Administration and Response Rate | ||

| Sample and Questionnaire Administration | Frequency | Percentage |

| Targeted Participants | 420 | 100% |

| Copies of Questionnaire Distributed | 307 | 73.09% |

| Copies of Questionnaire partially filled | 21 | 6.84% |

| Copies of Questionnaire with multiple responses | 9 | 2.93% |

| Total Usable Response | 277 | 90.23% |

Procedure for Data Analysis

Data was analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics (such as frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation). Regression analysis was employed in analyzing data and generating findings.

Hypotheses Testing and Discussion

Socio-demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Details of the respondents socio-demographic variables are shown in Table 3.

| Table 3 Descriptive Statistics of Demographic Characteristics of Respondents | ||

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 173 | 62.5 |

| Female | 104 | 37.5 |

| Age Group | ||

| Less than 20 years | 23 | 8.3 |

| 20 – 29 years | 86 | 31.0 |

| 30 – 39 years | 72 | 26.0 |

| 40 – 49 years 56 years and above |

55 41 |

19.9 14.8 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 98 | 35.4 |

| Married | 179 | 64.5 |

| Level of Education | ||

| Diploma or equivalent | 84 | 30.3 |

| B.Sc. or Equivalent | 136 | 49.1 |

| M.Sc./MBA or Equivalent | 57 | 20.6 |

| Average Monthly Income Below 100,000 101, 000 – 200,000 |

77 63 |

27.8 22.7 |

| 201,000 – 300,000 | 79 | 28.6 |

| 301,000 – 400,000 | 31 | 11.2 |

| 401,000 and above | 27 | 9.7 |

As shown in Table 3, participants were 277 subscribers of 4 major telecom operatirs, namely, MTN, Airtel, Glo and 9Mobile. There were 173 (62.5%) male and 104 (37.5%) female. Regarding their age, 23(8.3%) were less than 20 years of age, 86 (31.0%) were between 20 and 29 years old, 72 (26.0%) were between 30 and 39 years, 55 (19.9%) were between 40 and 49 years old, and 41 (14.8%) were between 50 years and above. Regarding their marital status, 98 (36.4%) were single and 179(64.6%) were married. Concerning their educational level, 84 (30.3%) were diploma holder or equivalent, 136 (49.1%) were university graduates or equivalent, and 57(20.6%) holds a Master’s degree or equivalent. As regard their average monthly income, 77(27.8%) were earning below 100,000, 63(22.7%) earning 101, 000 – 200,000, 79(28.5%), were earning between 201,000 – 300,000, 31(11.2%) earn between 301, 000 – 400,000, and 27(9.7%) earn between 401, 000 and above.

Analysis of Screening Questions

Table 4 shows that among the 277 subscribers surveyed, 106(38.3%) are using MTN network as their major line, 60(21.7%) are using Airtel as their major network, 74(26.7%) are using Glo as their major mobile network, and 37(13.4%) are using 9Mobile as their major mobile network. As shown in Table 4, 109(39.4%) are using only 1 line, 127(46.8%) are using two lines, and 41(14.8%) are using three lines. Also from Table 4, 260 (93.9% are on prepaid tariff plan, and 17(6.1%) are on postpaid tariff plan.

| Table 4 Screening Questions | ||

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Subscriber’s Mobile Operator’s | ||

| MTN | 106 | 38.3 |

| Airtel | 60 | 21.7 |

| Glo | 74 | 26.7 |

| 9Mobile | 37 | 13.4 |

| Subscribers Number of GSM Line | ||

| 1 | 109 | 39.4 |

| 2 | 127 | 46.8 |

| 3 | 41 | 14.8 |

| Tariff plan | ||

| Prepaid | 260 | 93.9 |

| Postpaid | 17 | 6.1 |

Test of Hypotheses

Table 5 shows inter-correlations among the brand personality dimensions and consumer product choice, which exhibit low, to moderate and high positive and statistically significant correlations among themselves (the correlation ranged from .212 to .674 and p< 0.01). Precisely, sophistication is connected to other dimensions as: sophistication and sincerity (r=.212**, p<0.01), sophistication and excitement (r=.300**, p<0.01), sophistication and competence (r=.436**, p<0.01), sophistication and ruggedness (r=.405**, p<0.01). From Table 5, sincerity is linked to other brand personality elements as: sincerity and excitement (r=.594**, p<0.01), sincerity and competence (r=.328**, p<0.01), and sincerity and ruggedness (r=.293**, p<0.01). As depicts in Table 5, excitement is related to other factors as: excitement and competence (r=.450**, p<0.01), excitement and ruggedness (r=.419**, p<0.01). Table 5 also depicts that competence is associated with other brand personality factor as: competence and ruggedness (r=.491**, p<0.01). As shown in Table 5, all the five brand personality dimensions exhibit low, to moderate and high positive statistical significant correlations with consumer product choice. The findings are related to each hypothesis in the next paragraph.

| Table 5 Correlation Matrix of Brand Personality and Consumer Product Choice | ||||||||

| Mean | Standard deviation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Sophistication | 3.63 | 0.812 | 1 | |||||

| Sincerity | 3.66 | 0.689 | 0.212** | 1 | ||||

| Excitement | 3.76 | 0.840 | 0.300** | 0.594** | 1 | |||

| Competence | 3.82 | 0.718 | 0.436** | 0.328** | 0.450** | 1 | ||

| Ruggedness | 3.87 | 0.774 | 0.405** | 0.293** | 0.419** | 0.491** | 1 | |

| Consumer product choice | 3.71 | 0.533 | 0.415** | 0.674** | 0.640** | 0.462** | 0.396** | 1 |

H1: stated that there is no significant relationship between sophistication as a measure of brand personality and consumer product choice. However, finding revealed that sophistication is moderately related to consumer product choice (r=.415**, p<0.01). This finding is in line with the study carried out by Shukla, Banerjee, and Singh (2016) and Chung and Park (2017) that reported a significant positive effect of sophistication as a dimension of brand personality and consumer choice decision.

H2: stated that there is no significant relationship between sincerity as a measure of brand personality and consumer product choice However, finding exposed that sincerity is highly related to consumer product choice (r=.674**, p<0.01). Finding of this study is consistent with that of the study carried out by Kinjal (2014), Cuevas (2016) and Puzakova, Kwak and Bell (2015) that maintained that sincerity as a dimension of brand personality promotes longer and more loyal relationships from customers, and consolidation with time as reflected by continuous purchase decision.

H3: stated that there is no significant relationship between excitement as a measure of brand personality and consumer product choice However, finding exposed that excitement is highly significantly related with consumer product choice (r=.640**, p<0.01). The outcome of this study corroborates the findings of research conducted by Huang, Wang, and Gong (2014) and Hwang and Lim, (2015) who reported that exciting brands are trendy brand that gains wider acceptability due to its style sagacity, desire for usability, or even appealing value and as such play a remarkable role in consumer experience, prompting perceptions, consumer engagement and ultimately brand choice.

H4: stated that there is no significant relationship between competence as a measure of brand personality and consumer product choice However, finding uncovered that competence is highly significantly connected with consumer product choice (r=.462**, p<0.01). Finding of this study confirms the position expressed by Klipfel, Barclay, and Bockorny (2014), and Wirunphan and Ussahawanitchakit (2016) that stated that brands known for competence generate an image of dependability, responsibility, trustworthiness, competence and success to meet the desire of the target market, hence, influence consumer choice decision.

H5: stated that there is no significant relationship between ruggedness as a measure of brand personality and consumer product choice However, finding uncovered that competence is highly significantly connected with consumer product choice (r=.462**, p<0.01). The outcome of this study confirms the views expressed by Das (2014) and Toldos-Romero and Orozco-Gomez (2015) that expressed that ruggedness as a brand equity personality dimension is a significant predictor of consumer choice decision.

Further analysis was carried out using multiple linear regression. The mathematical expression of the relationship between the independent (brand personality), and dependent (consumer product choice) is depicted in what is generally known as regression model. In the model, the independent variable and dependent was regressed. The model is stated as:

Y= α+B1X1+B2X2+.......BnXn +e

Where X=is the independent variable (brand personality, comprising of sincerity, sophistication, excitement, competence, and ruggedness)

Y=is the dependent variable (consumer product choice)

α =is the intercept/constant

βs=are the gradients which are perimeters to be estimated, brand personality measures

e=is the stochastic error

As presented in Table 6, the regression model confirms the following statistics R= .736, p=.000, adjusted R2 = .534 and R2=54.2%. The ANOVA sub-analysis also shows that the brand personality predicted consumer product choice. (F=64.189, p=.000). The Coefficient row in Table 7, showed that all the brand personality dimensions significantly predicted the modelsophistication (β=.175, t=3.757, p =.000), sincerity (β=.234, t=4.368, p =.000), excitement (β=.259, t=3.979, p =.000), competence (β=.100, t=2.009, p =.000), and ruggedness (β=.192, t=2.844, p =.000). The dimension that contributed most to the model is excitement (25.9%) and the least is competence (10.0%).

| Table 6 Model Summary | |||||||||

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R2 | Std. Error of the Estimate | |||||

| 0.736 | 0.542 | 0.534 | 0.364 | ||||||

| ANOVA | Sum of Square | Df. | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ||||

| Regression | 42.479 | 5 | 8.496 | 64.189 | .000 | ||||

| Residual | 35.869 | 271 | .132 | ||||||

| Total | 78.348 | 276 | |||||||

| Table 7 Coefficient | ||||||||

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficient | Unstandardized Coefficient |

||||||

| β | Std. Error | Beta | t | Sig. | ||||

| Intercept | 1. 281 | .152 | 8.420 | .000 | ||||

| Sophistication | .116 | .031 | .175 | 3.757 | .001 | |||

| Sincerity | .181 | .041 | .234 | 4.368 | .000 | |||

| Excitement | .164 | .041 | .259 | 3.979 | .000 | |||

| Competence | .075 | .037 | .100 | 2.009 | .000 | |||

| Ruggedness | .118 | .042 | .192 | 2.844 | .005 | |||

Using the model stated above, the regression equation is Y= 1.281+.175X1+.234X2+.259X3+.100X4+.192X5 + e = .542 , the model demonstrates that brand personality predicted consumer product choice (54.2%).

Conclusion

This study examined the relationship between brand personality and consumer product selection in the Nigerian telecommunications industry. The five brand personality dimensions, namely, sincerity, sophistication, exciting, competence, and ruggedness significantly predicted consumer product selection. Study conducted by Kichamu (2018) confirmed the relevance of the five dimensions of brand personality on consumer choice decision. Fournier (1998) stated that consumers' attitudes and behaviors towards the brand will echo in brand personality which may influence consumer tendency in connection with the brand and ultimately impact purchase prospect. According to Kimeu (2016), strong brand personality is invaluable in building brand equity that provide basis for differentiation based on impression created on the brand personality. Study conducted by Geyskens (2016) found that creating and managing strong brands is deliberated as one of the most fundamental tasks in brand management, because it serves as an entry barrier that makes it problematic for rivals to enter the market. Brand personality creates a mechanism which brands can use to distinguish themselves; and thus, serves as a major determinant for customer buying intentions and choice behavior (Bruwer & Buller, 2005).

Modern-day era reflect major changes within the marketing strategies exploited by businesses looking for opportunity to uphold competitive advantage. Subsequently, firms have turn to the use of behavioral and sociological factors such brand personality to stimulate consumers purchasing behavior. In contemporary consumer societies, consumers purchase products or service not only for what they can do (physical characteristics and functional values) but also for what they symbolize which are often the major motives for consumers’ purchase. Consequently, the focus of businesses changes progressively to symbolic benefits of brands (Tong, Su, & Xu, 2018). As expressed by Aaker (1996), brand personality can be adopted to build strong brands for companies because it offer a framework for companies to leverage brand identity, brand communication as well as establishing the essential guiding principle for marketing programs.

The notion of brand personality has attained huge prominence within brand management domain, with a view of fulfilling their consumers’ desires and to create long-term consumerbrand relationships, and for businesses reposition their brands with distinctive personalities (Tong et al., 2018). Brand personality provides a major business benefits. For instance, it creates better understanding and ensure superior engagement between brands and consumers (Chinnedu et al., 2016), and describes how consumer-brand relationship influences consumer choice decision (Aaker, 1996). Consequently, a business that develops and maintains a strong brand personality evidently nurtures the success of branding activities. Contemporary marketing has extremely advanced. As a result, companies utilize consumer-centered tactics to inspire their capabilities to fulfill the countless desires and needs of the customer. In the midst of these consumer driven methods, branding strategies such as brand personality has become one of the major activities essential within the building of a faithful customer base and the formation of a persuasive brand.

According to Ahmed and Jan (2015), one of the proactive approaches for creating brand superiority is through brand personality. Sticking personalities to brand aids in making a distinctive identity and build better desirability for consumers. This study filled important gaps in literature by employing a cross-sectional descriptive research design to explore the connection of brand personality to consumer product selection in the Nigerian telecommunication industry. The outcome of this study confirms that consumers do associate specific brand personality elements with specific brand categories, thus, the study contributes remarkably to empirical literature by revealing that the five brand personality dimensions; sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication and ruggedness have significant influence on product election. The scale and the distinguishing brand personality measurements documented in this study can be used as a practical marketing framework for brand managers in the telecommunication industry to build strong brand personality.

Recommendations

1. Business organizations should express the brand’s personality to customers by using numerous marketing programs to establish and enhance the level of resemblance between the company brand and target market.

2. The management should strive to incorporate all the essential dimensions of brand personality, namely, sincerity, sophistication, excitement, sophistication, and ruggedness in their promotion mix and marketing initiatives to ensure that their brand continuously communicates to customers the personality they want to identify with. Therefore, businesses need to have genuine commitment towards brand personality aiming at solving unpretentious desire of consumers.

3. Companies should persuade consumers’ relation to the brand personality dimensions using opinion leaders and personas that are regarded as authorities in particular areas, to present them as brand ambassadors and representatives of their brand.

Limitations of the Study and Suggestions for Future Research

This study has some inherent limitations, which constitutes areas for future research. First, findings of the study only reflect the views of telecom subscribers brand personality perception. For this purpose, the scale ought to be reexamined with consumers from other different contextual domain, such as customers of other industries. Secondly, convenience sampling approach was adopted in this study as sampling procedure, which may limit the generalization of the study findings.

In addition, participants were recruited mainly from four major telecom operators, researchers are encouraged to incorporate other telecom services firms such fixed line telecom operators for further research. Thirdly, the effect of brand personality on other outcomes such as level of perceived, switching tendency and price resistant among others should be investigated to extend knowledge and business practices.

References

- Aaker, J., Fournier, S., & Brasel, S.A. (2004). When good brands do bad. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 1-16,

- Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3), 347-356.

- Aaker, D.A. (1996). Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California Management Review, 38,102-120.

- Aaker, J. L. (1999). The malleable self: The role of self-expression in persuasion. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(1), 45-57.

- Aaker, J.L., Vohs, K.D., & Mogilner, C. (2010). Nonprofits are seen as warm and for profits as competent: Firm stereotypes matter. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 224-237.

- Ahmad, A., & Thyagaraj, K.S. (2014). Applicability of brand personality dimensions across cultures and product categories: a review. Global Journal of Finance and Management, 6(1), 9-18.

- Ahmed, M., & Jan, M.T. (2015). An extension of Aaker’s brand personality model from Islamic perspective: A conceptual study. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 6(3), 388-412.

- Albert, N., Merunka, D., & Valette-Florence, P. (2008). The love feeling toward a brand: Concept and measurement. Advances in Consumer Research, 36, 300-307

- Anandkumar, V., & George, J. (2011). From Aaker to Heere: A review and comparison of brand personality scales. The International Research Journal of Social Science and Management, 1(3), 30-50.

- Ang, S.H., & Lim, E.A. (2013). The influence of metaphors and product type on brand personality perceptions and attitudes. Journal of Advertising, 35(2), 7.

- Anisimova, T.A. (2007). The effects of corporate brand attributes on attitudinal and behavioral consumer loyalty. The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 24(7), 395-405.

- Arnould, E.J., Price, L., & Zinkhan, G. M. (2005). Consumers. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Arora, R., & Stoner, C. (2009). A mixed method approach to understanding brand personality. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 18(4), 272–283.

- Austin, J.R., Siguaw, J.A., & Mattila, A.S. (2003). A re-examination of the generalizability of the Aaker brand personality measurement framework. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 11(2), 77-92.

- Avis, M., Aitken, R., & Ferguson, S. (2012). Brand relationship and personality theory: metaphor or consumer perceptual reality? Marketing Theory, 12(3), 311-331.

- Azoulay, A., & Kapferer, J.N. (2003). Do brand personality scales really measure brand personality? Journal of Brand Management, 11(2), 143-155.

- Azoulay, A., & Kapferer, J.N. (2003). Do brand personality scales really measure brand personality? Journal of Brand Management, 11(2), 143–155.

- Beldona, S., & Wysong, S. (2007). Putting the “brand” back into store brands: an exploratory examination of store brands and brand personality. Emerald Journals, 16(4), 226-235.

- Belk, R.W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139–168.

- Bettman, J.R., Luce, M.F., & Payne, J.W. (1998) Constructive consumer choice processes. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(3), 187–217

- Bruwer, J., & Buller, C. (2005). Country-of-origin brand preferences and associated knowledge levels of Japanese wine consumers. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 25(1), 307-316.

- Caprara, G.V., Barbaranelli, C., & Guido, G (2001). Brand personality: How to make the metaphor fit? Journal of Economic Psychology, 22(3), 377-395.

- Carlson, B.D., Donavan, D.T., & Cumiskey, K.J. (2009). Consumer- brand relationships in sport: brand personality and identification. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 37(4), 370-384.

- Chinedu, N.O., Onuoha, A.O., & Onuegbu, O. (2016). Brand personality and marketing performance of Deposit Money Banks in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. International Journal of Research in Business Studies and Management, 3(5), 37-48

- Chung S., & Park J. (2017). The influence of brand personality and relative brand identification on brand loyalty in the European mobile phone market. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 4, 47–62.

- Cuevas, L. (2016). Fashion Bloggers as Human brands; Exploring brand personality within the Blogosphere (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from https://digital.library.txstate.edu/ handle/10877/6351

- Daniel, W.W. (1999). Biostatistics: A foundation for analysis in the health sciences 7th edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Das, G. (2014). Store personality and consumer store choice behavior: an empirical examination. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 32(3), 375-394.

- Doyle, P. 1998. Marketing management and strategy. 2nd edition, USA: Prentice Hall.

- Eisend, M., & Stokburger-Sauer, N.E. (2013). Brand personality: A meta-analytic review of antecedents and consequences. Marketing Letters, 24(3), 205-216.

- Escalas, J.E., & Bettman, J.R. (2005). Self-construal, reference groups, and brand meaning. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(3), 378–389.

- Fiske, S.T., Cuddy, A.J.C., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77-83.

- Fournier, S (1998). Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(4), 343-353.

- Freling, T.H., & Forbes, L.P. (2005). An empirical analysis of the brand personality effect. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 14(7), 404-413.

- Geyskens, I. (2016). Let your banner wave? Antecedents and performance implications of retailers private-label branding strategies. Journal of Marketing, 80, 1–19.

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective, (7th eds.). New Jersey: Pearson Prentice-Hall.

- Heine, K. (2009). Using personal and online repertory grid methods for the development of a luxury brand personality. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 7(1), 25–38.

- Huang, H.H., Mitchell, V.W., & Rosenaum‐Elliott, R. (2012). Are consumer and brand personalities the same? Psychology & Marketing, 29(5), 334-349.

- Huang, Y., Wang, B., & Gong Q. (2014). An empirical research on brand personality of Smart phone. Retrieved from https// Marketing-trends-congress.com/archives/2014

- Hwang, Y., & Lim, J. S. (2015). The impact of engagement motives for social TV on social presence and sports channel commitment. Telematics and Informatics, 32(4), 755-765.

- Kang, Y.J., & Park, S.Y. (2016). The perfection of the narcissistic self: A qualitative study on luxury consumption and customer equity. Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3813–3819.

- Kaplan, M.D., Yurt, O., Guneri, B., & Kurtulus. K. (2010). Branding places: Applying brand personality concept to cities. European Journal of Marketing, 44(9/10), 1286-1304.

- Karjaluoto, H., Munnukka, J., & Salmi, M. (2016). How do brand personality, identification, and relationship length drive loyalty in sports? Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 26(1), 50-71.

- Kichamu, D. A. (2018). The influence of brand personality on brand choice: A case of colgate palmolive in Nairobi. A Research Project Report Submitted to the Chandaria School of Business in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Masters of Business Administration (MBA) United States International University, Africa.

- Kim, E., & Sung, Y. (2013). To App or Not to App: Engaging consumers via branded mobile Apps. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 13(1), 6.

- Kim, P., Vaidyanathan, R., Chang, H., & Stoel, L. 2017. Using brand alliances with artists to expand retail brand personality. Journal of Business Research, 88, 424-433.

- Kimeu, M.S. (2016). Effects of service brand personality on brand performance in the context of Kenya's Insurance sector. European Journal of Business and Management, 8(18), 6.

- Kinjal, G. (2014). A study on brand personality of Coca-Cola and Pepsi: A comparative analysis in the Indian market. International Journal of Conceptions on Management and Social Sciences, 2(2), 2357 – 2787.

- Klipfel, J., Barclay, A. & Bockorny, K. (2014). Self-Congruity: A determination of brand personality. USA: Prentice Hall Publishers.

- Kotler, P., & Keller, K. (2012). Marketing management, USA: Pearson publishers.

- Kumar, A. & Kumar, R.V. (2015). A curious case of business media brand personality scale. Management and Labour Studies, 40(1&2), 95-108

- Letizia, A., Efthymios, C., & Massimo, F. (2018). Towards a better understanding of consumer behavior: Marginal utility as a parameter in Neuromarketing research. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 10(1), 90-106

- Levitt, T. (1983). The globalization of markets. Harvard Business Review, 61(3), 92-102.

- Lin, L.Y. (2010). The relationship of consumer personality trait, brand personality and brand loyalty: An empirical study of Toys and Video Games buyers. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 19(1), 4–17

- Maehle, N., Otnes C., & Supphellen M. (2011). Consumers’ perceptions of the dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 10, 290–303.

- McCracken, G. (1986). Culture and consumption: A theoretical account of the structure and movement of the cultural meaning of consumer goods. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(1), 71-84.

- Mugenda, O., & Mugenda, A. (2010). Research methods: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. Nairobi: ACT Press.

- Mulyanegara R.C., & Tsarenko, Y. (2009). The big five and brand personality: Investigating the impact of consumer personality on preferences towards particular brand personality. Journal of Brand Management, 16(4), 234-247.

- National Bureau of Statistics (2019). Nigerian Telecommunications sector Summary Report: Q4 and full year 2019. Retrieved from http://www.nbs.org.ng.

- Naresh, S.G. (2012). Do brand personalities make a difference to consumers? Procedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences, 37, 31-37.

- Okazaki, S. (2006). Excitement or sophistication? A preliminary exploration of online brand personality. International Marketing Review, 23(3), 279-303.

- Park, C.W., MacInnis, D.J., Priester, J., Eisingerich, A.B. & Laccobucci, D. (2010). Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. Journal of Marketing, 74, 1-17

- Pessemier, E. A. (2012). Forecasting brand performance through simulation experiments. Journal of Marketing, 28(2), 41-46.

- Plummer, J.T. (2000). How personality makes a difference. Journal of Advertising Research, 40(6), 79–83.

- Puzakova, M., Kwak, H., & Bell, M. (2015). Beyond seeing McDonald’s fiesta menu: The role of accent in brand sincerity of ethnic products and brands. Journal of Advertising, 44(3), 219–231.

- Ramaseshan, B. (2007). Moderating effect of the brand concept on the relationship between brand personality and perceived quality. Journal of Brand Management, 14, 458-466.

- Shukla, P., Banerjee, M., & Singh, J. (2016). Customer commitment to luxury brands: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Business Research, 69(1), 323–331.

- Sirgy, M.J. (1982). Self-concept in consumer behaviour: A critical review. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(3), 287- 300,

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87, 355-374.

- Su, J., & Tong, X. (2015). Brand personality and brand equity: Evidence from the sportswear industry. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 24(2), 124-133.

- Sung, Y. (2011). The effect of usage situation on Korean consumers’ brand evaluation: The moderating role of self-monitoring. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 10(1), 31-40.

- Sung, Y., & Kim, J. (2010). Effects of brand personality on brand trust and brand affect. Psychology and Marketing, 27(7), 639–661.

- Sweeney, J.C., & Brandon, C. (2006). Brand personality: Exploring the potential to move from factor analytical to circumplex models. Psychology and Marketing, 23(8), 639-663,

- Toldoz-Romero, M., & Gomez, M. (2015). Brand personality and purchase Intention. European Business Review, 27(5), 6.

- Tong, X., Su, J., & Xu, Y. (2018). Brand personality and its impact on brand trust and brand commitment: An empirical study of luxury fashion brands. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 11(2), 196-209.

- Truong, Y., Klink, R.R., Simmons, G., Grinstein, A., & Palmer, M. (2017). Branding strategies for high-technology products: The effects of consumer and product innovativeness. Journal of Business Research, 70, 85–91.

- Tversky, A., & Kahnemann, D. (1981). The framing of decision and the psychology of choice. Science, 2(11), 453–458

- Vahdati, H., & Nejad, S.H.M. (2016). Brand personality toward customer purchase intention: the intermediate role of electronic word-of-mouth and brand equity. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 21(2), 1–26.

- von Wallpach, S., Voyer, B., Kastanakis, M., & Mühlbacher, H. (2017). Co-creating stakeholder and brand identities: introduction to the special issue. Journal of Business Research, 70, 395-398.

- Wirunphan, P., & Ussahawanitchakit, D. (2016). Brand competency and brand performance: an empirical research of cosmetic businesses and health products business in Thailand. The Business and Management Review, 7(5), 5.

- Wong, M.C.M., Kwok, M.L.J., & Lau, M.M. (2015). Spreading good words: The mediating effect of brand loyalty between role model influence and word of mouth. Contemporary Management Research, 11(4), 313.

- Xu, A., Liu, H., Gou, L., Akkiraju, R., Mahmud, J., Sinha, V., Hu, Y, & Qiao, M. (2016). Predicting perceived brand personality with social media. Proceedings of the Tenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2016):436-445.

- Zhou, J.X., Arnold, Pereira, A., & Yu, J. (2010). Chinese consumer decision-making styles: A comparison between the coastal and inland regions. Journal of Business Research, 63, 45-51.