Research Article: 2022 Vol: 26 Issue: 1

Eco-Friendly Purchase behaviour of Emerging Adults: Investigating the Role of Religiosity

Chandan Parsad, Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Bodh Gaya, Uruvela

Vinita S. Sahay, Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Bodh Gaya, Uruvela

Soumyajyoti Banerjee, Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Bodh Gaya, Uruvela

Citation Information: Parsad, C., Sahay, V.S., & Banerjee, S. (2022). Eco-friendly purchase behaviour of emerging adults: investigating the role of religiosity. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 26(1), 1-17.

Abstract

Keyword

Religiosity, Emerging adult, Eco-friendly, Purchase Intention.

Introduction

The literature on religion has been profoundly concerned by the impact of religiousness and religious practices on individual behaviour. As the world shifted towards a deep ecological crisis, governments, economies, businesses, and communities worldwide started taking stock of environmental concerns. In the last two decades, most major world religions also started focusing on the ecosystem. Christian communities started many eco-friendly movements, such as "Creation Care" and "Green Bible." They published eco-friendly Bible cantos in green text and provided a nature-friendly explanation of the same. Followers of Judaism started "Tikkun Olam" ('the healing of the world') and "EcoKosher". "EcoIslam" was another ecological movement started by Islamic followers. Followers of Hinduism led initiatives such as the "Bhumi Project", the "Vrikshamandiras" (tree temples) and the "Sankat Mochan Foundation." They addressed issues of the pollution of sacred rivers, the earth and the cutting down of trees (Shodhganga 2011).

Across religions, such initiatives found common ground to influence and motivate its followers to act responsibly towards the environment. Research has established a common connection between religion and individual environmental behaviours across religions ( Ellingson 2016). Policymakers and community leaders started acknowledging the role of religion in creating awareness of environmental concerns.

Moreover, the connection between religion and individual environmental behaviour was self-evident because most of the population in any country or world belongs to one of the major world religions ( Engelland 2014), and religion is known to have a profound impact on individual and community behaviours ( Ellingson 2016). According to a 2010 report by the Pew Research Center, in 2050, the population of Christians will be 2.92 billion, Muslims will be 2.76 billion, and Hindus will be 1.23 billion ( Daniel 2015; Pew Research Center 2010). It led to numerous studies on the relationship between religion and the environmental behaviour of individuals and communities.

Despite religion and religiousness having an enriching history of research, not enough has happened in religious development. This area of religious research has lagged considerably. Primarily, there remains a dearth of studies on the link between emerging adults' religiousness and environmental behaviours. Most studies on religious development are on the evolution of an individual's understanding of and relation to religious images, symbols, language, etc. Previous studies have primarily focused on how an individual relates to religion and the methods for pursuing spirituality as they grow and develop. As young people attain adolescence, we know that this stage accompanies their individualization and cognitive development, making them "more capable of personalizing their understanding of and relationship to the religion and the sacred". While emerging adults or adolescents see their identity as separate from peers, parents, and institutions, they nevertheless remain part of and dependent upon "significant others to be a sounding board for the composition of their own faith identity" ( Arnett 2004).

Along with a scarce body of research on emerging adults' religiousness, another body of research is focused on the consumption patterns of emerging adults. This research draws a clear distinction in the consumption choices of emerging adults from consumers of other age groups. These two separate lines of research on emerging adults in the areas of religion and consumer behaviour, respectively, present an opportunity to study them together. However, there are hardly any studies on emerging adults that connect their religiousness and environmental behaviours.

As stated earlier, studies have established the impact of religion on an individual's environmental concern. Most studies were conducted in the West, focusing on Western religious contexts, such as Judaism and Christianity ( Martin & Bateman 2014; Schultz et al., 2000). James (1902/2004) describes that Western religions (Christianity, Judaism, Islam) believe that God created nature and, therefore, God and humans hold a superior position to nature (White's thesis 1967 cited in Van 2005). Thus, the disciples of such religions are less likely to be ecologically responsive ( Sarre 1995). On the other hand, Oriental faiths such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Sikhism and Taoism, believe that God and the universe are the same. The followers of these faiths believe that protecting nature is an essential part of their Dharma (responsibility). Hence, they are more nature friendly ( Sarre 1995). Besides, studies on the impact of Western religions on environmental concern produce conflicting results. Smith & Leiserworth (2013) posited that American evangelicals showed less concern for ecological changes than non-evangelicals.

Research conducted by Martin & Batman (2014) showed a positive correlation between religiousness and ecological concern. Arli & Tjipotono (2017) also established Islam's positive impact on individual concern for protecting the environment.

Still, there are insufficient studies that explore the impact of religion on eco-friendly purchase behaviour in the context of non-Western religious traditions, especially Hinduism, the fourth-largest religion in the world ( Arli & Tjipotono 2017; Minton et al., 2015). Many researchers have opined that every religion comprises a specific set of values, beliefs, and approaches that leads to a particular behaviour ( Allport & Ross 1967; Arli & Lasmono 2015; Zinnbauer et al., 2015). Hence, the eco-friendly behaviour of individuals living in a Hindu dominated culture will be significantly different from those living in cultures dominated by other religions ( Aminzadeh 2013; Minton et al., 2015). Therefore, this study investigates the influence of an individual's religious attitude on their ecological concern and subjective norms related to. It also explores the effect of these attitudes on their intention to purchase eco-friendly products.

Also, no significant study has yet been conducted on the correlation between emerging adults' religious practices and their influence on their environmental behaviours. As emerging adults strive to achieve a more defined sense of self, their search often turns inward to beliefs and values ( Nelson, 2013). Nelson (2003) mentions that emerging adulthood are a unique period in development. As mentioned earlier, emerging adulthood is distinguished by relative independence from social roles and normative expectations and characterized by increased freedom from family and support structures, change, and the exploration of possibilities. Therefore, this study focuses on emerging adults in India, which is number 3 in terms of the most religious country in the world ( Trimble & Austin 2019), and the second most populated country with the most significant Hindu population, has a majority of their people as emerging adults.

Theoretical Framework

Djupe & Gwiasda (2010); Hirschman et al. (2011) opine that consumer attitudes and behaviour can be affected by their core values. Sandicki and Ger (2010) expressed that "religion, like other institutional and social structures, such as gender, class, and ethnicity, influences consumption choices." These researchers opined that religion bears a significant impact in shaping one’s core values. Their line of reasoning finds similar logic to the theory of reasoned action, which states that "consumer values and attitudes motivate behaviour" ( Ajzen & Fishbein 1980).

This paper employs the theory of religious values. According to this theory, religion makes the follower or devotee more moral and bids some values and principles that the follower practices in their lives. Worthington et al. (2003) define the theory of religious values. They point out that religion does not directly impose obligations but usually moralistically sets specific values, beliefs, and practice requirements. Worthington et al. (2003) defined religious commitment as the degree to which a person adheres to their religious values, beliefs, and practices and uses them in daily living. According to Swimberghe (2010), religious commitment measures initially involves both a cognitive (focuses on the individual's belief or personal religious experience) and behavioural component (the degree to which an individual practises his religious affiliation). One of the most crucial aspects of religion is that it seldom enforces any obligations (Hirschman et al., 2011; Worthington et al., 2003). In 1967, Allport and Ross described religious orientation "as the extent to which a person lives out his or her religious beliefs". This belief is one of the most important cultural forces that impact person-purchasing behaviour (Essoo & Dibb 2004). These religious commitments and beliefs influence people's feelings and attitudes towards consumption (Jamal, 2003).

Researchers also propose that religious inspirations can be classified into two different motivations, namely, intrinsic and extrinsic. The "extrinsically motivated person uses his religion, while the intrinsically motivated person lives his religion" ( Allport 1950). An intrinsically motivated devout person tends to "follow religion in his/her daily life routine and most important he/she never wants anything in return from the God". However, the person with extrinsic religiousness motivation may be more "persuaded by social elements and preforms all the religious-related activities to meet his/her personal goals/needs" (e.g., source of comfort and peace) or for social goals (e.g., social support; Allport 1950; Vitell et al., 2005).

Who are Emerging Adults?

Emerging adults are those between 18 and 29 ( Nelson & Barry, 2005). It is a prolonged transition phase between adolescence and adulthood characterized by "[t]he rise in the ages of entering marriage and parenthood, the lengthening of higher education, and prolonged job instability during the twenties." These reflect the development of a new period of life for young people in industrialised societies, lasting from the late teens through the mid-to-late twenties. ( Arnett 2000) Furthermore, emerging adulthood is differentiated from adolescence as "[t]his period is not simply an extended adolescence, because it is much different from adolescence, much freer from parental control, much more a period of independent exploration" (Sharp et al., 2006). It is also different from young adulthood "[…] since this term implies that an early stage of adulthood has been reached, whereas most young people in their twenties have not made the transitions historically associated with adult status— especially marriage and parenthood—and many of them feel they have not yet reached adulthood" ( Arnett 2004).

Arnett (2007) proposed five phases that make emerging adulthood distinct: "the age of identity/explorations, the age of instability, the self-focused age, the age of feeling in-between, and the age of possibilities". Emerging adulthood is distinguished by a "relative independence from social roles and normative expectations and characterized by increased independence from family and support structures, change, and the exploration of possibilities". Emerging adults in this phase "anticipate career, marriage, and worldview choices. During this period, the scope of independent exploration of life's possibilities is greater for many young people than it will be at any other period of the life course" ( Arnett 2000; Arnett 2006; Schwartz et al., 2004; Smith 2009; Wuthnow 2010). Arnett (2007) pointed out that emerging adulthood is a transition phase, which undergoes cultural and religious self-construction, and the worldview is neither fixed nor universal.

They often have an open mindset towards modifications in their lives. Pascarella and Terenzini (cited in Arnett 2000) argue that "most of the research on changes in worldviews during emerging adulthood has involved college students and graduate students, and there is evidence that higher education promotes explorations and reconsiderations of worldviews". Research also shows that emerging adults, irrespective of their educational background, “consider it important during emerging adulthood to reexamine the beliefs they have learned in their families and to form a set of beliefs that is the product of their independent reflections" ( Arnett 2000).

Religious Practices of Emerging Adults

Research focusing on emerging adults' religious activities indicates that religious participation and religious practices are lower in emerging adults than adolescents or children ( Gallup & Castelli 1989). This is also true for emerging adults who practised high religious participation and socialisation during adolescence and childhood. Even the adults could not maintain their previous levels. Arnett (2006) also notes a "marked reduction in attendance of religious services, such that only 50% of individuals in their early to middle twenties attend religious services about 1–2 times per year or less." (pp.14).

Other studies have made comparisons among emerging adults within various religious groups. A longitudinal study by Smith (2009) points out that "evangelical Protestants and black Protestants both display a slight increase in service participation among emerging adults whereas, for the same age cohort, service participation among Mainline Protestants and Catholics declined considerably." Commenting on four religious traditions, Smith (2009) opines that there was a religious decline in emerging adults irrespective of the tradition to which an emerging adult belongs. Vaidyanathan (2011) argued that despite the variation within religious traditions, significant differences still arise between these groups in the outcome effects of association with their religious practice.

Other studies point out that this decline in emerging adults' religiousness happens because of their transitional world view, making them exploratory and unsettling on a particular belief ( Setran & Kiesling 2013). It is further accentuated by the lack of attention from religious institutions, which makes them feel ignored and cannot be an excellent fit for religious institutions ( Belzer et al., 2007). Researchers largely opine that religious institutions have low interest in emerging adults because "some pastors neglect ministry to emerging adults as they know they are in a time of transition" ( Uecker et al., 2007). Also, emerging adults may feel "turned off" because "religious institutions focus on children, youth, and families and exclude their age group" ( Mitchell et al. 2016).

Religiousness: Hinduism

Traditionally, Hinduism as a religion and philosophy is closely aligned with the environment. Since ancient times, Hindu religious practices have been closely connected with nature and imbibed the concept of nature as an intrinsic part of its deep-rooted culture and tradition. Hindu philosophy gives nature the status of a mother. Thus, Hinduism considers the protection of nature as one of its core values. Ancient Hindu gurus (teachers) taught the lesson of the conservation of nature to ordinary folks and kings, and other elite members ( Rust 2017). Hindus have traditionally believed in sustainable consumption and considered it their moral responsibility to protect nature and be responsible for the environment. Hinduism is one of the rarest religions where plants/trees and animals are also worshipped, and it is considered blasphemous to kill an animal or cut down a tree ( Dwivedi 1993). Hindus believe that Lord Krishna (God)'s incarnations were fish, tortoise, man-lion (Narasimha), among others. In Shreemad Bhagwad Gita, Lord Krishna says "This form is the source and indestructible seed of multifarious incarnations within the universe, and from the particle and portion' of this form, different living entities, like demigods, animals, human beings and others, are created" (Srimad-Bhagavata Book 1, Discourses III: 5). The Bhagavad Gita (1974).

In Atharva Veda 12.1-15, the "earth is the home of humans and all other species". In the Gita Lord Krishna states that, "I am creator, maintainer, and annihilator of this world, I am origin and dissolution ( Devi 1982). All things like oceans, animals, plants, trees, sky, as well as all the species were created by me, and human beings do not have any privilege over other species" (Gita 7.6 in Goswami & Sastri 1982). Instead, the duty of maintaining harmony and balance between humans and nature is upon human beings. They are mainly responsible for maintaining the balance of nature and acting as the savior of the environment. Hindu philosophy emphasizes the fact that "God’s grace can only be received when we protect and give equal opportunities to all creatures”. In the Vishnu-Puran (3, 8, 15), “Lord Krishna blesses those who protect the other non-speaking species”. Hinduism endorses a Dharmic way of life, including protecting the environment and the development of all. Based on such tenets, we hypothesize that:

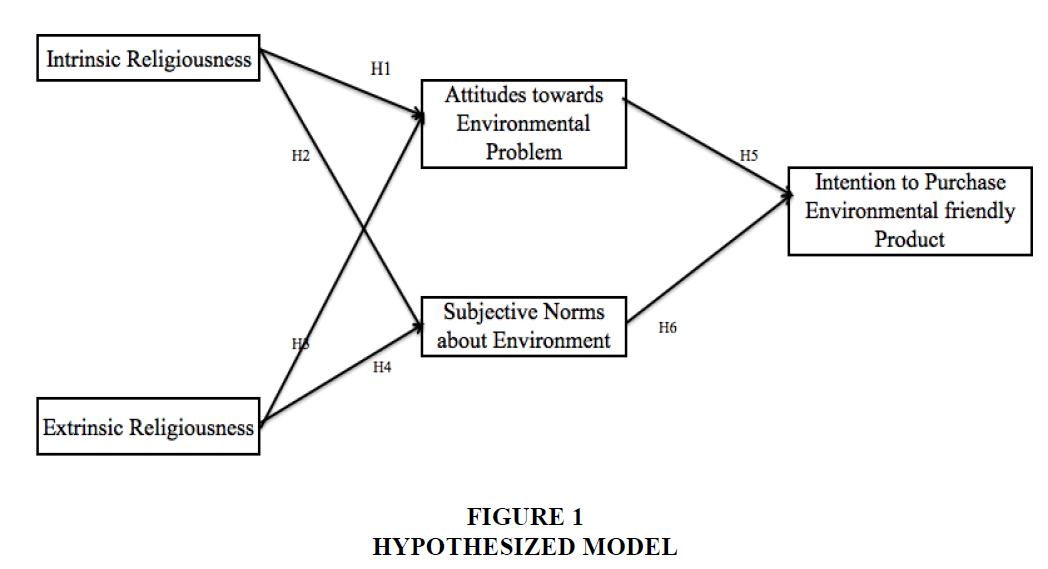

H1: There is a positive association between the intrinsic religiousness of individuals and their attitudes toward environmental problems.

H2: There is a positive association between the intrinsic religiousness and subjective norms of an individual.

Theories on moral identity and religious attitudes have differentiated individuals based on extrinsic versus intrinsic motivations. This distinction becomes essential to know what drives an individual to become righteous or religious. According to Allport and Ross (1967, pp.442), “[t]o know that a person is in some sense "religious" is not as important as to know the role religion plays in the economy”. Therefore, the distinction of religious orientation into extrinsic and intrinsic becomes crucial. An extrinsically interested individual uses his religion, while the intrinsically driven individual lives his religion ( Allport & Ross 1967). Individuals with extrinsic religiousness have socially ascribed identity to it. They use religion to achieve their social goals, e.g., making friends, social relationships, attending cultural events and festivals, earning their place in society, and getting affiliated with religious groups. They wear religious clothes, follow religious practices, and visit sacred sites because their faith gives them a shared identity with others and a common platform to further their socialization.

Within a Hindu society killing animals and cutting trees is considered sinful acts and can impact social relations. Attachment towards nature varies among individuals. A person high on extrinsic religiousness might not be concerned about environmental issues than one who is high on intrinsic religiousness. Hence, we propose that:

H3: Extrinsic religiousness will be negatively related to attitudes toward environmental problems.

H4: Extrinsic religiousness will be positively related to subjective norms.

Attitude towards Environmental Problems

An individual's attitude is defined as a predisposition directed towards an object or a person having positive or negative valence towards that object or person ( Ajzen 2001). Numerous studies consider attitude a better predictor than demographic variables ( Cleveland et al., 2005; Kalamas et al., 2014). A line of research found a strong association between attitude towards the environment and organic food purchasing behaviour (Grunert 1993). Environmental attitude is defined as “the collection of beliefs, affects, and behavioural intentions a person holds regarding environmentally related activities or issues” ( Schultz et al., 2004). Research has found that a positive attitude towards the environment predisposes consumers to responsible consumption by buying products with zero carbon footprints, such as green or recycled products (Hauser et al., 2013).

However, there are some contrary findings to this positive association as well. Gupta & Ogden (2009); Kollmuss & Agyeman (2002) found an insignificant correlation between green behaviour and the actual purchase of an eco-friendly product. (Gupta & Ogden 2009). The theory of reasoned action ( Ajzen and Fishbein 1980) and the theory of planned behaviour ( Ajzen 1991) suggest that "the adoption of a behaviour" of individuals "is the outcome of their beliefs and attitudes." Individuals who have a serious concern for the ecosystem exhibited a greater tendency to participate in environment-related activities irrespective of their age and gender ( Granzin & Olsen 1991). The findings of numerous studies corroborate this viewpoint and report that a positive attitude towards the environment or being concerned about it leads to consumers buying more organic food (Hauser et al., 2013; Pino et al., 2012 & Zhou et al., 2013). Such consumers are ready to pay a higher price for equivalent eco-friendly products ( Banerjee & McKeage 1994). Many studies have confirmed the positive impact of ecosystem concern on responsible attitude and behaviour ( Mostafa 2007; Simmons & Widmar 1990). Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:.

H5: Attitudes toward environmental problems is positively related to the intention to purchase environment-friendly products.

Subjective Norm about the Environment

“Changing behaviour or attitude in tune with society’s norms or aligning the decisions with the rest of the society is known as the subjective norm” ( Ajzen 1985). Norms play an essential role in developing an attitude towards eco-friendly products and guiding individual purchasing behaviour ( Arli & Tjiptono 2017; Peattie 2010). A robust subjective norm may “increase the probability of transformation or consuming factors over time to environment-friendly behaviour, like adopting a green electricity tariff and social norms can reroute individual behaviour to the socially accepted behaviour” ( Bamberg 2003; Ozaki 2011). Gadenne et al. (2011) argue that presenting a positive image of oneself is very important and this encourages people to conform to the norms of the groups to which they want to belong.

Several studies conducted on consumer buying behaviour show that individual buying pattern or behaviour is highly influenced by the reference group/ inspirational group, mainly a colleague, family unit, partners and friends (Jager 2006; Pickett‐Baker & Ozaki 2008). Recent studies by Arli & Tjiptono (2017); Kim & Chang (2011) have found that subjective norms can influence consumer behaviour related to intention to buy environmentally friendly products Figure 1.

H6: Subjective norms about environmental problems will be positively related to purchasing environment-friendly products.

Research Methodology

Construction of Survey Instrument

For assessing both endogenous and exogenous constructs for this study, we adapted constructs from the established literature. We amended the Allport & Ross (1967) ten-item scale to examine the participants' intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness. A sample item includes “As a religious person, my religion affects my daily life”. We used the three-item scale proposed by Bohlen et al., (1993) for assessing individual attitudes towards environmental problems such as, "the environment is one of the most important issues." We drafted individual subjective norms about the environment from Fishbein & Ajzen (1975). Lastly, we used the scale developed by Arli & Tjiptono (2017) to observe participant intention to purchase eco-friendly products. We appointed a group of professionals from industry and academia to scrutinize the questionnaires. After trivial reformations in the statements' language, we created the final survey instrument, comprising eighteen items covering the constructs. We used a 7-point Likert scale as the anchor, with one as 'Strongly disagree' and seven as 'Strongly agree'.

Data Collection

India is the birthplace of eastern religions, like Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism. Approximately 80% of the Indian population follows Hinduism, while fourteen per cent follows Islam, Christians comprise 2.3%, and Sikhism has 1.7% of the population, as per the Census of India (2011). For Indians, religion is among the essential parts of their lives. India is home to ninety per cent of Hindus worldwide. India is, thus, ideal for investigating the influence of Hindu religiousness on individuals’ environment-friendly purchase behaviour.

Survey Design

This cross-sectional study involves both exploratory as well as conclusive phases. We used the convenience sampling method for collecting data. Convenience sampling was used for collecting homogeneous data, which increases the generalizability of the result (Jager et al., 2017). We distributed 400 survey instruments among various educational institutes, shopping malls and other public places from ten cities across India: Bangalore, Chennai, Delhi, Jaipur, Jammu, Kochi, Kolkata, Mumbai, Puri and Raipur. Out of ten cities, five were metropolitans where people across India travel to and reside with varying religious backgrounds. Moreover, the selected cities have popular Hindu sacred sites. Prominent among them are the Jagannath temple in Puri; Mata Vaishno Devi temple in Jammu, Guruvayoor temple; India’s first mosque and Church in Kochi; ISCKON temple, mosque and church in Bengaluru, and the Shri Siddhi Vinayak temple, several mosques and churches in Mumbai, among several others. After collecting the semi-finished questionnaires, three hundred twenty-three were found suitable for the study. The collected data has an equal representation of both males and females. Social desirability is the main reason for common method bias in the case of self-rated measurement. We reminded each respondent to respond according to how they behave or will behave in the given context. We explained the purpose of the study to the participants and sought their voluntary participation before distributing the questionnaires. We assured the participants that their responses would be kept confidential. These methods are consistent with the procedures prescribed by Podsakoff et al. (2003) to reduce common method bias.

Analysis and Results

We adopted a two-step statistical data analysis. We assessed the validity of the hypothesized model by both convergent and discriminant validity, using confirmative factor analysis. We used Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for measuring scale reliability. We used structural equation modelling (SEM) with AMOS as a data analysis tool to test the proposed hypotheses.

Testing Validity and Reliability

As indicated in Table 1, all the fit indices values like CMIN/DF =2.01; GFI =0.903; CFI =0.951; IFI =0.953 and RMSEA= 0.06 of the measurement model are well above the cut for value, and it implies a good fit (Hair et al. 2009). Table 1 also exhibits that each variable's standardized loading value was more than 0.50 and that Cronbach's alpha coefficient ranges between 0.805 and 0.921, which is well above 0.70, signifying that the constructs were reliable (Hair et al., 2009). The average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability of each construct was more than 0.50 and 0.70, respectively, specifying the constructs' internal validity and reliability (Hair et al., 2009). Given that each construct's AVE value in Table 2 is higher than the squared correlation coefficient between the given and another construct, the discriminant validity was also proved.

| Table1 Factor Loading | ||

| Items | Standardized Loading estimates | Cronbach’s α |

| Intrinsic religiousness | ||

| As a religious person, my religion affects my daily life | 0.744 | 0.921 |

| My whole approach to life is based on religion | 0.815 | |

| My religion is an important part of my life | 0.85 | |

| I try hard to live all my life according to my religious beliefs | 0.85 | |

| I have often had a strong sense of God's presence | 0.650 | |

| It is important to me to spend time in private thought and prayer | 0.73 | |

| I enjoy reading about my religion | 0.71 | |

| Extrinsic religiousness | ||

| I go to a religious service because it helps me to make friends | 0.87 | 0.903 |

| I go to a religious service because I enjoy seeing people I know over there | 0.85 | |

| I go to a religious service mostly to spend time with my friends | 0.86 | |

| Attitude towards environmental problems | ||

| The environment is one of the most important issues | 0.82 | 0.805 |

| Unless each of us recognizes the need to protect the environment, future generations will suffer the consequences | 0.72 | |

| The benefits of protecting the environment do not justify the expense involved | 0.65 | |

| Subjective norms about the environment | ||

| People who are important to me buy environment‐friendly products | 0.78 | 0.845 |

| People who are important to me are concerned about the environment | 0.84 | |

| It is important to buy environment‐friendly household products | 0.804 | |

| Intention to purchase environment-friendly products | ||

| How likely are you to purchase environment‐friendly household products | 0.8 | 0.857 |

| Intend to buy environment‐friendly household products during the next six weeks | 0.92 | |

| Fit Indices | ||

| CMIN/DF =2.01; GFI =0.903; CFI =0.951; IFI =0.953 and RMSEA= 0.06 | ||

| All items were measured on a seven-point Likert scales, ranging from ‘‘strongly disagree’’ to ‘‘strongly agree,’ | ||

| Table 2 Discriminant Validity | |||||||

| CR | AVE | IR | ER | AEP | SN | IP | |

| Intrinsic religiousness (IR) | 0.91 | 0.59 | 0.768 | ||||

| Extrinsic religiousness (ER) | 0.898 | 0.75 | 0.084 | 0.866 | |||

| Attitude towards environmental problem (AEP) | 0.81 | 0.522 | 0.163 | -0.200 | 0.723 | ||

| Subjective norms about the environment (SN) | 0.85 | 0.65 | 0.345 | 0.362 | 0.242 | 0.806 | |

| Intention to purchase environment-friendly product (IP) | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.254 | 0.069 | 0.590 | 0.652 | 0.860 |

Testing of Hypotheses

The structural equation model (SEM) was used to assess the hypothesized relationships in the proposed model. We tested all the six proposed associations (both strength and significance) precisely. From a total of six tested associations, five were statistically significant Table 3. Of the two variables that reflect religiousness (Intrinsic and Extrinsic), the former has a significant effect on subjective norms about the environment (β=0.141; 0.421 p<0.1 respectively). Thus, hypothesis H2 is supported Table 3. In Table 3, ‘intrinsic religiousness’ has been established as a significant predictor of attitude towards environmental problems (β=0.315, p<0.1). However, we rejected hypothesis H3 because there was no statistically significant effect of extrinsic religiousness on attitude towards environmental problems in the model (β=0.054, p>0.1). It implies that extrinsic religiousness does not affect customers’ attitudes toward environmental problems.

| Table 3 Model Estimation | ||||||

| β | P | Result | ||||

| Intrinsic religiousness | H1 | Attitude towards environmental problem | 0.354 | 0.00 | Accepted | |

| Intrinsic religiousness | H2 | Subjective norms about the environment | 0.141 | 0.00 | Accepted | |

| Extrinsic religiousness | H3 | Attitude towards environmental problem | 0.054 | 0.11 | Rejected | |

| Extrinsic religiousness | H4 | Subjective norms about the environment | 0.421 | 0.00 | Accepted | |

| Attitude towards environmental problem | H5 | Intention to purchase environment-friendly product | 0.531 | 0.00 | Accepted | |

| Subjective norms about the environment | H6 | Intention to purchase environment-friendly product | 0.371 | 0.00 | Accepted | |

| Fit Indices | ||||||

| CMIN/DF =1.475; GFI =0.913; CFI =0.977; IFI =0.978 and RMSEA= 0.051 | ||||||

Purchasing products that are less harmful to the environment depends on individual attitude, so this aspect is significant for understanding an individual's intention to purchase environment-friendly products. Therefore, hypothesis H5 is supported Table 3. Moving to hypothesis H6, Hindu subjective norms about the environment have the strongest influence on the intention to purchase environment-friendly products (β=0.141; 0.371 p<0.1). It is noticeable that individuals who portray a positive attitude towards environmental problems and subjective norms about the environment consistently purchase eco-friendly products. The intention to purchase environment-friendly products is associated with individuals’ attitudes towards the environment and subjective norms. Hence, it supports hypotheses H5 and H6. From Table 3, it is also clear that all goodness of fit indices values is well above/within the recommended levels (RMSEA<0.08, GFI>0.90, CFI & IFI>0.90) (Hair et al., 2009; Nunnally 1978). This implies that the model is good.

Discussion and Implication

Previous research on religion has prominently focused on Western religions’ influence on environmental concern in the context of the Western world ( Martin & Bateman 2014; Schultz et al., 2000). This study is the first attempt to analyse how eastern religions, like Hinduism, influence Oriental people's nature-friendly behaviour, considering how intrinsic and extrinsic religious practices affect an individual's attitude towards environmental problems and subjective norms. This study gives a more holistic understanding of Eastern religions' impact on individuals' behaviour and attitude towards the environment. It also predicts how these behaviours and attitudes influence the intention to purchase environment-friendly products.

This study establishes the role of intrinsic religiousness on individuals’ attitudes towards the environment and their subjective norms about the environment. The Gita proclaims that “Ether, air, fire, water, earth, planets, all creatures, directions, trees and plants, rivers and seas, they are all organs of God’s body. Remembering this a devotee respects all species” Srimad Bhagavatam (2/2/41).

In other words, a follower of Hinduism must protect nature because God creates it. Similarly, Atharvaveda, (5/4/3) mentions “ aśwatthu devasadanastritiyashamityo divi. tatramṛitayasyo śakhan deva kushthamavanwat’’ (one of God's incarnations is a tree; thus, being a follower of this religion, we cannot harm nature). It reflects the importance of nature and religion's role in creating awareness about the conservation of nature. In Hinduism, ‘killing animals and cutting trees is sinful.’ It implies that a person’s intrinsic and or extrinsic religiousness towards nature follows social norms related to the environment, and this study proves these correlations.

The findings of this study are in line with many previous studies. This study proposes that an individual’s attitude towards environmental problems will impact their environment-friendly behaviour. One of the behaviours is the intention to purchase environment-friendly products. This finding is in line with Ajzen (1991), Ajzen and Fishbein (1980), Fisher (2011), Hauser et al. (2013), Granzin and Olsen (1991), Pino et al. (2012) and Zhou et al. (2013). These studies emphasize that an individual's attitude towards the environment will lead to consuming eco-friendly products and developing eco-friendly habits, e.g., consuming organic foods, using less plastic, purchasing star rated electronic equipment, and participating in environment-related activities.

Culturally, an eastern religion like Hinduism has always emphasized the protection of nature. Hindus believe that God is present everywhere, including the natural world. Therefore, one should not destroy nature. If one is involved in such activities, one is sinning. This belief has developed a positive attitude towards environmental issues among the followers of eastern religions, and our study also supports this relationship.

This study also reveals that individuals who portray extrinsic religiousness follow subjective societal norms about the environment. An essential aspect of these norms is that they redirect personal behaviour towards socially accepted behaviour. The subsequent finding of this study shows that individual subjective norms about the environment are positively associated with the intention to purchase environment-friendly products. This is also in line with previous research by Arli & Tjiptono (2017), Ellingson et al. (2012), Kim & Chang (2011); Ozaki (2011), which claimed that the person-purchasing pattern is mainly dependent on ‘the orientation of other’, most importantly, from the point of view of friends, family, colleagues, and aspirational group. These subjective norms can influence individual attitudes toward adopting environment-friendly behaviour, like green electric power solutions or purchasing star-rated electronic items .

A marketer who wants to improve consumers' awareness of the importance of environmental sustainability and subsequently support a green cause; can link them with social norms. This study's findings also highlight the significant influence of religiousness on an individual's intention to purchase eco-friendly products, especially those who follow Hindu religions. The results show the importance of collaboration between the government, businesses, and religious institutions to improve consumers' awareness of environmental sustainability and support a green cause.

Conclusion

This study hypothesized and verified how an individual's religious behaviour impacts one's attitude towards environmental problems and subjective norms about the environment. Individual attitudes and subjective norms impact the intention to purchase environment-friendly products. The model proposed six hypotheses, out of which five were accepted. The findings of this study reveal that intrinsic religiousness plays a more significant role in influencing an individual's attitude towards environmental problems. In contrast, extrinsic religiousness has more impact on an individual’s subjective norms about the environment. The findings of this research provides practical, theoretical implications to academic researchers and managerial implications to the marketer, government, businesses, and religious institutions.

Limitation and Future Research

This study helps practitioners and academics understand the role of an individual’s religiousness in purchasing eco-friendly products. However, this research is not without its limitations. The first limitation of this study is that the data employed are cross-sectional in one country, and therefore, the study’s generalizability may be limited. Second, the focus of this study is on followers of Hinduism only. Future research may investigate other religions, such as Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism. However, future research can also analyze religious versus nonreligious consumers, cross‐national studies, and so forth.

References

Ajzen, H., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. NJ: Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behaviour. In Kuhl J., & Beckmann J(Ed.), Action control (11-39). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organisational behaviour and human decision processes, 50(2), 179-211.

Allport, G.W. (1950). The Individual and his religion: A psychological interpretation. New York: MacMillan.

Arnett, J.J. (2006). Emerging adulthood: Understanding the new way of coming of age. In Jeffrey Jensen Arnett & J. L. Tanner(Ed.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (3-19). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Arnett, J.J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 68-73.

Arnett, J.J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press.

Belzer, T., Flory, R.W., Roumani, N., & Loskota, B. (2006). Congregations that get it: Understanding religious identities in the next generation. Passing on the faith: Transforming traditions for the next generation of Jews, Christians, and Muslims, (pp. 103-122).

Daniel, B. (2015). The world's fastest‐growing religion is …. CNN. Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2015/04/02/living/pew-study-religion/index.html

Devi, C. (1982). The Atharvaveda. New Delhi: Munsiram, Manoharlal Publishers: India.

Djupe, P.A., & Gregory, W.G. (2010). Evangelising the environment: Decision process effects in political persuasion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 49(1), 73-86.

Dwivedi, O.P. (1993). Human Responsibility and the Environment: A Hindu Perspective. Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies, 6(8), 19-26.

Ellingson, S. (2016). To care for creation: the emergence of the religious environmental movement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ellingson, S., Vernon, A.W., & Paik, A. (2012). The structure of religious environmentalism: Movement organisations, interorganizational networks, and collective action. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51(2), 266-285.

Environmental issues. (2010). Pew Research Center, Chapter 8.

Environmental protection and religious and cultural heritage in India. (2011). Shodhganga. Accessed on April 24 2020.

Fishbein, M., & Icek, A. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison‐Wesley.

Gallup, G., & Castelli, J. (1989). The people’s religion: American faith in the ’90s. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Goswami C.L., & Sastri, M.A. (1982). Srimad Bhagavata Mahapurana (2nd Vol.) Gorakhpur: Gita Press.

Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L., & Black, W.C. (2009). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed). London: Pearson Education

Jager, W. (2006). Stimulating the diffusion of photovoltaic systems: A behavioural perspective. Energy Policy, 34(14), 1935–1943.

James, W. (1902/2004). The varieties of religious experience. New York: Touchstone.

Kim, H.Y., & Chung, J. (2011). Consumer purchase intention for organic personal care products. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(1), 40–47.

Minton, E.A., Kahle, L.R. & Kim, C. (2015). Religion and motives for sustainable behaviours: A cross-cultural comparison and contrast. Journal of Business Research, 68(9), 1937-1944.

Mitchell, J.M., Poest, E.B., & Espinoza, B.D. (2016). Re-Engaging emerging adults in ecclesial life through Christian practices. Journal of Youth Ministry, 15(1), 34–57.

Nelson, L.J. (2003). Rites of passage in emerging adulthood: Perspectives of young Mormons. New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 33-49

Nunnally, J.C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Peattie, K. (2010). Green consumption: behaviour and norms. Annual review of environment and resources, 35, 195-228.

Pickett‐Baker, J., & Ozaki, R. (2008). Pro‐environmental products: Marketing influence on consumer purchase decision. Journal of Consumer Marketin, 25(5), 281–293.

Rust, N. (2017). Religion can make us more environment friendly. BBC. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20170206-religion-can-make-us-more-environmentally-friendly-or-not

Schultz, P.W., Zelezny, L., & Nancy J.D. (2000). A multinational perspective on the relation between Judeo-Christian religious beliefs and attitudes of environmental concern. Environment and Behaviour, 32(4), 576-591.

Setran, D.P., & Kiesling, C.A. (2013). Spiritual formation in emerging adulthood: A practical theology for college and young adult ministry. Michigan: Baker Academic.

Smith, C., & Snell. P. (2009). Souls in transition: The religious and spiritual lives of emerging adults. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

The Bhagavad Gita. (1974).Commentator Swami Shidbhavananda, Tirruchirapalli: Sri Ramakrishna Tapovanam.

Trimble, M., & Shelbi, A. (2021). The 10 Most Religious Countries, Ranked by Perception. U.S.NEWS. Retrieved from https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/10-most-religious-countries-ranked-by-perception?slide=9

Wuthnow, R. (2010). After the baby boomers: How twenty- and thirty-somethings are shaping the future of American religion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Zinnbauer, B.J., Pargament, K.I., Cole, B., Rye, M.S., Butfer, E.M., Belavich, T.G., Hipp, K., Scott, A.B., & Kadar. J.J. (2015). Religion and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy. In Sociology of religion (29-34). Oxfordshire: Routledge.