Research Article: 2018 Vol: 19 Issue: 1

Dropouts Issues and Its Economic Implications Evidence From Rural Communities In Ghana

Ngmen Yaganumah, St.Clare's Vocational Training Institute

Harriet Ellenlaura Obeng, University of Edinburgh

Abstract

Keywords

Dropouts, Primary Education, Economic Implications, Poverty, Child Marriages.

Introduction

The economic returns to education cannot be overemphasised. Literature abounds on the benefit a country can derive from education. Psacharopoulos & Woodhall (1985) indicated that the average return to education is higher than that of physical capital in Least Develop Countries (LDCs) but lower in Develop countries (DCs). Education helps individuals fulfill and apply their abilities and talents and increases productivity in an economy. Kuznets (1955) posits that the major stock of an economically advanced country is not its physical capital but “the body of knowledge amassed from tested findings and discoveries of empirical science and the capacity and training of its population to use this knowledge effectively.” According to Baldwin and Beckstead, (2003) “world of knowledge in which human capital, skills, innovation and technology are more necessary than ever in order to be competitive” is required in emerging economies. It has been argued that persons with high literacy and numeracy skills, analytic abilities and adaptability are more competitive in terms of employability and professional success (Hankivsky, 2008). Psacharopoulos and Woodhall (1985) argue that among human investments, primary education is the most effective for overcoming absolute poverty and reducing income inequality. Primary school education is the foundation and also a prerequisite for any further training in education. Apart from this, education is a fundamental human right that every child should have access to (Amoako, 2000) and also a form of human capital investment for all (Harber, 2014).

In view of this, many nations have policies to promote education among children towards achieving education for all which is a Millennium Development Goal 2 (MDG 2). Ghana, for example, has since 1995, instituted Free Compulsory and Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) policy. The FCUBE programme contributed to a significant increase in enrolment (Ministry of Education, 2014). Research has revealed that other interventions in the educational sector such as capitation grants, school feeding programme and provision of school supplies such as uniforms for the public have contributed to the increase in school enrolment. For example, a study on school feeding programme in Ghana indicated positive effects on school enrolment and school academic performance (Abotsi, 2013). Retention, repetition, drop-out and irregular attendances are problems faced with the call to universal education for all, especially in developing countries. The universal primary education goes beyond enrolling children in school, but these children must be helped to complete their education as well (UNICEF, 2012). Dropping out of school at the basic level has long been viewed as a serious educational and social problem.

The difficulty in maintaining these pupils in school after their enrolment especially in the rural areas must be of concern to all. This has become necessary because a report by the Ghana Living Standard Survey (Ghana Statistical Services, 2014b) reveals that 37.1 percent of the population aged 5 years and older have attained less than Middle School Leaving Certificate/Basic Education Certificate (MSLC/BECE) whereas 25.7 percent have never been to school. The 2010 population and housing census reveal that there exists a huge gap in educational attainment between urban children and their rural counterparts. Only eight percent of urban dwelling children in Ghana have no education while almost 1 in every 4 children in rural dwelling had no education (Ghana Statistical Services, 2014a). Rural education in Ghana is characterised by low enrolment, lack of professionally trained teachers, poor infrastructural facilities, lack or inadequacy of teaching and learning materials (Ghana Statistical Services, 2014a). This development makes dropouts in the rural areas peculiar and worth investigating. Most basic level dropouts have serious educational deficiencies that have severe consequences on them throughout their adult lives by limiting their economic and social well- being.

There is, therefore, the need to focus policy attention on addressing problems of dropout in the rural areas in order to achieve a universal basic education. Since the causes of dropout are complex and varied (Ananga, 2011), there is the need to analyse the causes of dropout in the rural areas and its economic implications in order to inform policy formulation in curbing these phenomenon. This is the motivation of this study. This study will sample views of not only the dropouts but also the caregivers or parents of these dropouts in the Wenchi Municipal Assembly so as to get a holistic view of the causes of dropouts.

Literature Review

Dropout has been conceptualized in many ways with various definitions. Generally, dropout is understood by many researchers as a developmental process; Starting in earliest grades where dropout is considered as the inability of the learner to continue with school, usually due to learners own capability (Evans, Chicchelli, Cohen & Shapiro, 1995; Lamb, Markussen, Teese, Sandberg & Polesel, 2011). Some other researchers believe the system is responsible for not enabling the learner to continue in school (Reddy & Sinha, 2010).

The individual theoretical underpinning of dropout is based on students’ attributes, including their value systems, attitudes and behaviours regarding school engagement and how they contribute to the decision to drop out of school (Grant & Hallman, 2006; Hunter & May, 2003; Wehlage, Rutter, Smith, Lesko & Fernandez, 1989). The institutional theoretical underpinning on the other hand focuses on contextual factors found in institutions such as students’ families, communities, schools as well as education systems and policies (Grant & Hallman, 2006; Hunter and May, 2003; Reddy, & Sinha, 2010; Rumberger, 2001; Wehlage & Rutter, 1989). Brimmer & Pauli (1971) defined a school dropout as a person who leaves school before the end of the final year of the education stage and Awedoba, Yoder, Fair and Gorin (2003) also defined school dropout as pupil’s permanent withdrawal from School. In all these definitions, there is no ambiguity about the fact that dropout refers to a pupil who has abandoned their course of study and therefore is unable to complete a program of studies and has not transferred the programme to another school.

Various characteristics associated with dropout risk have been identified in literature in varied domains such as school, family, community and the students themselves (Suh & Suh, 2007). Coley (1995) found school-related problems such as student disliking school, receiving poor grades among others as school-related causes of dropout. Devine (1996) found parents' low educational attainment, the number of household members and lack of motivation as reasons why students with a low socioeconomic status drop out of school. Pittman (1986) &Tidwell (1988) posited that students' resistance and resentfulness toward the school community was a major variable in their decision to drop out. Caraway, Tucker, Reinke & Hall (2003) identified students' low level of engagement in their education as an important factor leading to higher dropout rates.

In some other literature, poor children have been found to be more likely to be out of school than their wealthier (Akyeampong, 2009; Filmer & Pritchett, 2004; Rolleston, 2009). In fact, review of the literature on dropout by Hunt (2008) all cited poverty as one of the reasons for parents’ and guardians’ inability to pay for their wards’ educational costs, thus compelling them to terminate their education (Brown & Park, 2002; Colclough, Rose & Tembon, 2000; Dachi & Garrett, 2003; Hunter & May, 2003 as cited in Hunt, 2008). One of the focus areas of this study is the socio-economic factors that serve as pull factors of dropout. Ampiah and Adu‐Yeboah (2009) contended that dropping out of school seems to be the result of a series of events involving a range of interrelated factors, rather than a single factor from the perspective of school dropouts.

The problem of dropout is an intricate issue which should not just be limited to known factors. This is because human capital which is the accumulation of investments in people such as education is necessary for the growth of an economy. Undeniably, many authors posit human capital as the key ingredient of economic growth (Galor & Moav, 2003; Lucas, 1988). Indeed, Goldin (2001) has also attributed much of the US economic success in the twentieth century to the accumulation of human capital. Lucas (1993) has claimed that ‘the main engine of growth is the accumulation of human capital of knowledge and the main source of differences in living standards among nations is differences in human capital’. This calls for further exploratory studies to be conducted on dropouts based on individual community characteristics as a step to tackling the problems facing every community holistically.

Methodology

This study adopts a descriptive research design and employed quantitative research methods to collect and analyse data. The study area is the Nchiraa Circuit in Wenchi Municipal Assembly which is located in the Brong-Ahafo Region in Ghana. The population of interest included households in communities in the Nchiraa Circuit that have dropouts. Five communities were sampled out of fourteen communities in the area using simple random sampling technique. These communities are Asampo, Kyebi-Nkwanta, Adoi, Aminamu (Bogi) and Pewodea. The sample size is a total of 50 households (ten from each community) which were selected using systematic sampling technique. Every 10th household in each community was sampled but households that did not have dropouts were exempted from the study. Therefore the households included in the study were selected using purposive sampling and all the dropouts in each household were included in the sample. It must be emphasised that consent was always sought from the parents of the dropouts and the dropout themselves involved in the study. The instrument for data collection was a structured questionnaire, the first questionnaire is the household questionnaire and the second questionnaire was for the dropouts. The causes of dropout are analysed from the perspective of parents, the dropouts themselves and the schools.

Results and Discussion

The analysis is done in three stages. First is the analysis of household questionnaire which examines the information about the parents, number of children in the household, occupation and level of parents’ education and causes of dropout from the parent perspective. The second set of analysis is based on responses of the dropouts and the last set of analysis is the school-based questionnaire answered by heads of four basic schools in the Nchiraa Circuit. However, even though the analysis is done separately the facts and evidence are merged to give a holistic response to the research questions.

Dropout Cases per Communities

Out of the 50 households sampled, 46 agreed to participate in the survey. The number of communities involved is 5 with 10 samples from each. Kyebi-Nkwanta recorded the highest number of dropouts per the study which is 23.7% followed by Pewodea which recorded 21.5% and Adoi which recorded 20.4%. Aminamu (Bogi) recorded 19.3% while Asampo recorded the least at 15.1% as shown in Table 1.

| Table 1: Dropout Cases Per Communities | |||

| Community | Number of Households Sampled | Number of Dropouts per Community | Percentage of Dropout per Community |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kyebi-Nkwanta | 10 | 22 | 23.7 |

| Pewodea | 10 | 20 | 21.5 |

| Asampo | 9 | 14 | 15.1 |

| Adoi | 9 | 19 | 20.4 |

| Aminamu (Bogi) | 8 | 18 | 19.3 |

| Total | 46 | 93 | 100 |

Source: Field Survey, 2017.

Education and Income

All the parents in each household are farmers and this is expected since the study area is predominately a farming community. The educational levels attained by the parents are presented in Table 2. The result shows that 31 (67.4%) of fathers and 37 (80.4%) of mothers have never had formal education. It is obvious that illiteracy among the parents is high and this is likely to negatively influence their children. Literature has indicated parents’ educational background to be one of the several reasons why students drop out of school (Devine, 1996).

| Table 2: Level Of Education Of Parents | ||||

| Fathers | Mothers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education level | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage |

| Nil | 31 | 67.4 | 37 | 80.4 |

| Primary | 6 | 13.0 | 5 | 10.9 |

| JHS | 5 | 10.9 | 4 | 8.7 |

| SHS | 3 | 6.5 | ||

| Tertiary | 1 | 2.2 | ||

| Total | 46 | 100.0 | 46 | 100.0 |

Source: Field Survey, 2017

Information on total annual household incomes is presented in Table 3. The annual income is considered because the respondents are farmers and can declare income only after the farming season. Only 1 household earned an annual income of GHS 7,501 and above and this represents 2.2%. About 35% and 37.0% receive incomes between GHS 5,001-GHS 7,500 and GHS 2,501-GHS 5,000 respectively. Information on the employment sector in the Wenchi Municipality indicates that about nine out of every ten persons (90%) aged 15 years and older who are working are in the private informal sector. The public sector constitutes only (6.6%) while the private formal sector makes up (3%). This is a clear indication that the majority of the people in the Municipality do not have the requisite educational qualification to gain employment in the formal sector (Ghana Statistical Services, 2014a). It is even more worrying when the children of these parents are dropping out of school. In the research literature, a large number of factors associated with family background and structure of dropouts have been identified to include socioeconomic status of the households. Numerous studies have found that dropout rates are higher for students from families of low socioeconomic status (Kolstad and Owings, 1986; Rumberger, 1983, 1987). The finding of this study is consistent with previous studies which found low educational and occupational attainment levels of parents, low family income to be associated with high dropouts rates (Rumberger, 1987; Steinberg, Blinde and Chan, 1984).

| Table 3: Levels Of Annual Household Income | ||

| Household Income | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Less than GHS 2,500 | 12 | 26.1 |

| GHS 2,501-5,000 | 17 | 37.0 |

| GHS 5,001-7,500 | 16 | 34.8 |

| GHS 7,501 and above | 1 | 2.2 |

| Total | 46 | 100.0 |

Source: Field Survey, 2017.

Number of Children per Household

The information on the total number of children per household is presented in Table 4. The highest number of children per household is 17 children while 7 households have either 4 or less children. Majority (10) of the households have 6 children with 8 of the households having 7 children. The number of children per household, given the household level of income, can affect the education of the children. Interestingly, the household that has the greatest number of children is among those households whose annual income is less than GHS 2,500. Among the households whose annual income is less than GHS 2,500, 2 have 5, 6 and 8 children each. This can affect the children’s schooling since the family will not be able to afford education for all the children. The finding is consistent with previous studies which posited that the number of household members accounts for high rate of dropout (Devine, 1996; Suh and Suh, 2007).

| Table 4: Number Of Children Per Household | |||||

| Annual Household Income (GHS) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of children per household | Less than 2,500 | 2,501-5,000 | 5,001-7,500 | 7,501 and above | Total |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 6 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 10 |

| 7 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 8 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 7 |

| 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 17 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 12 | 17 | 16 | 1 | 46 |

Source: Field Survey, 2017.

Location and Distance

This study sought to find out the location of the school and the distances walked by the pupils to school. Out of a total of 46 respondents, 10 of the households representing 21.7% have their wards attending school within their communities which is less than 1 kilometre from their residences (Table 5). The remaining 36 (78.3%) households have their children attending schools outside their community of residence. Out of this number, the wards of 13 and 10 households walk 3 kilometres and more than 3 kilometres respectively to school. These schools are relatively far from the communities of residence and could be attributed to the students’ dropping out of school because they have difficulty walking to school.

| Table 5: Location And Distance Of Schools | ||||||

| Distance of school from home | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location of school from home | less than 1Km | 1Km | 2Km | 3Km | More than 3Km | Total |

| In the community | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Outside the community | 0 | 4 | 9 | 13 | 10 | 36 |

| Total | 10 | 4 | 9 | 13 | 10 | 46 |

Source: Field Survey, 2017.

Children’s Educational Status among the Households Studied

Table 6 shows a summary of the education status of children in the households sampled. The table shows that out of a total number of 326 children in these households, only 168 children representing 51.5% of these children were enrolled in school. Out of 168 children who were enrolled in basic schools, 93 of them dropped out which represents 55.4% of the children enrolled in school. This means also that only 75 of the children enrolled in school were currently in school at the time of the study. This appeals the need for serious interventions to be implemented if children from these households must be enrolled and sustained in school.

| Table 6: Analysis Of Children’s Educational Status Among The Households | ||

| Description | Number of Children | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of children in the households sampled | 326 | 100 |

| Total number of children enrolled in school expressed as a % of total number of children in the households sampled | 168 | 51.5 |

| Total number of dropouts expressed as a % of number of children enrolled in school | 93 | 55.4 |

Source: Field Survey, 2017

Number of Dropouts per Household

An analysis of the dropout situation per household is presented in Table 7. The highest number of dropout per household is 6 and the lowest is 1. All the children in 2 of the households have all their 6 children dropping out of school. Out of the 46 households, 24 reported a single case of dropout. These children dropping out may have a bad influence on the younger ones not to stay in school.

| Table 7: Number Of Dropouts Per Household | |||||||

| Number of dropouts per household | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of children per household | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Total |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 6 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10 |

| 7 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 8 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 11 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 17 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 24 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 46 |

Source: Field Survey, 2017

Parents Perception of Causes of Dropouts

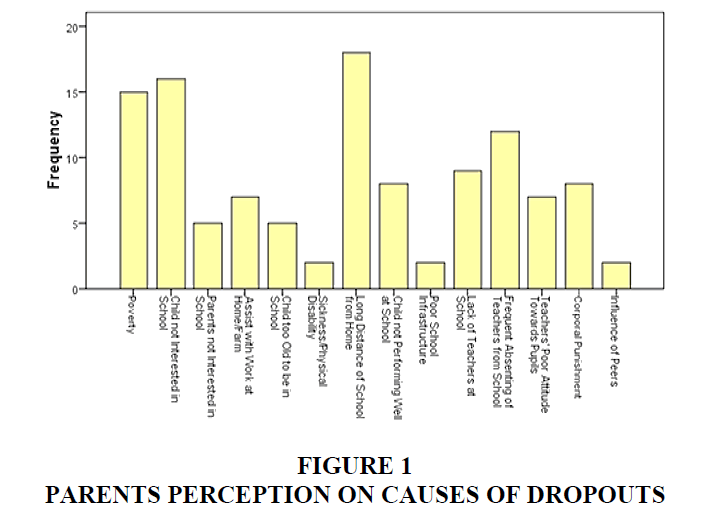

Parents views on some of the causes of dropout captured in literature were sought. The findings are presented in Figure 1. The study reveals that, parents are of the view that long distance of school from home (18 households representing 39.1%), child not interested in school (16 households representing 34.7%) and poverty (14 households representing 30.4%), are the leading causes of school dropout among their children.

Age and Gender of Dropouts

This analysis on dropouts is based on the 93 dropouts captured in the survey. The results in Table 8 show that the pupils within the ages of 6 and 10 years old recorded the highest dropout cases followed by those with 11 to 15 years with majority of them being males (63.4%). This phenomenon is likely to result in early marriages coupled with its associated problems. Research has shown that little or no schooling strongly correlates with being married at a young age (Malhotra, 2010). In fact, it has been reported in Ghana that majority of the population among rural settings are married compared to those living in the urban areas (Ghana Statistical Services, 2013). It has also been reported that child marriage is more common in rural areas compared to urban areas. Report by UNICEF indicates that child marriage increased from 30.6% in 2006 to 36.2% in 2011 across all rural areas while, it reduced from 20.5% to 19.4% in those same years across all urban areas in Ghana (UNICEF, 2015). These children who are already wading in poverty will end up raising their children in poverty.

| Table 8: Age And Gender Of Dropouts | |||

| Sex of Dropouts | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of Dropouts | Male | Female | Total |

| 0-5 years | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| 6-10 years | 22 | 16 | 38 |

| 11-15 years | 17 | 12 | 29 |

| 16-20 years | 12 | 2 | 14 |

| Total | 59 | 34 | 93 |

Source: Field Survey, 2017

Classes Attained by Dropouts before Dropping Out of School

The analysis of the classes that pupils attained in school before they dropped out is presented in Table 9. The dropout at the KG level is the highest (15) followed by Primary 6 (13), Primary 5 (12) and then Primary 1 (11). Dropout at the upper primary (primary 4 to primary 6) is generally higher (37.7%) than dropout at the lower primary (primary 1 to primary 3) 30.1% and JHS (Junior High School) 16.2 %. With exception of 1 female pupil, all the other females dropped out before JHS. Report by Ghana statistical service suggests that education plays a role in preventing child marriage in the Brong Ahafo Region. According to the report, a considerable proportion of persons who have attained primary (63.3%), JSS/JHS (62%) and SSS/SHS education have never married whereas every three in five persons who have never attended school are married (Ghana Statistical Services, 2013).

| Table 9: Classes Attained Before Dropping Out | |||

| Sex of Dropouts | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Class of Dropouts | Male | Female | Total |

| KG | 7 | 8 | 15 |

| Primary 1 | 7 | 4 | 11 |

| Primary 2 | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| Primary 3 | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Primary 4 | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| Primary 5 | 5 | 7 | 12 |

| Primary 6 | 9 | 4 | 13 |

| JHS 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| JHS 2 | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| JHS 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 59 | 34 | 93 |

Dropouts Perception on Causes of Dropout

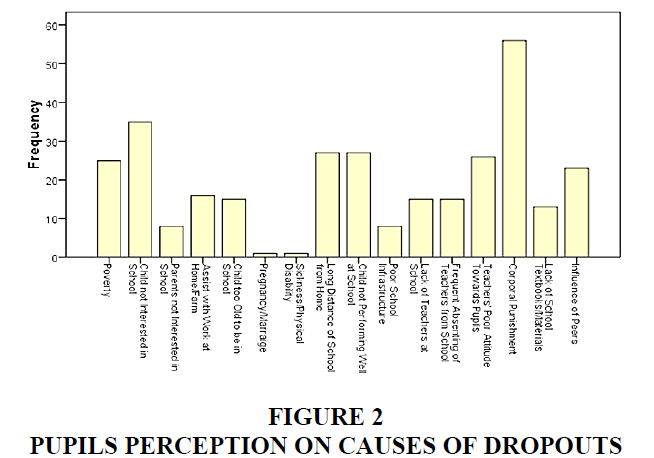

As was done in the case of parents, the perception of dropouts on some of the causes of dropout captured in literature was also sought. The findings are presented in Figure 2. The highest cause of dropout is attributed to corporal punishment. Fifty-six (56) dropouts representing 60.2% indicated that they dropped out of school because of corporal punishment in their schools. Thirty-five (35) representing 37.6% dropped out because they have no interest in schooling. The number of dropouts who dropped out because of long distance of school from home and poor performance is 29.0% (27) each and poor attitude of teachers towards pupils (28.0%).

Economic Implications of Dropouts

The phenomenon of dropping out of school has serious socio-economic implications on the individual dropouts themselves, their families, the society or community and the entire economy as a whole. Individual dropouts suffer because they may not be able to secure employment in future especially in the formal sector because of lack of the requisite educational qualification. In fact, Rumberger (1987) indicated that dropouts many have difficulty finding steady, well-paying jobs over their entire lifetimes. Information on the employment sector in the study area indicates that about nine out of every ten persons (90%) work in the private informal sector (Ghana Statistical Services, 2014a) which is an indication that the majority of the people in the Municipality do not have the requisite educational qualification to gain employment in the formal sector. This phenomenon will lead to increased dependency ratio in the family. The effect of unemployment on society such as armed robbery and other social vices cannot be overemphasised. The overall economy suffers from low productivity and increases demands on social services from the government.

A considerable proportion of persons who have attained primary and senior high school education in the study area have never married whereas every three in five persons who have never attended school are married (Ghana Statistical Services, 2013).This implies that with the increasing numbers of dropouts, the problem of child marriage may be aggravated. It has already been reported that child marriage is more common in rural areas compared to urban areas in Ghana (UNICEF, 2015).

Conclusion

The objective of the study was to analyse the causes of dropout in the rural areas and its economic implications using Wenchi Municipal Assembly as a case. The study finds that the number of dropouts per community is relatively enormous. The total number of dropouts in the communities included in the study is 93 and this represent 55.4% of the number of children enrolled in school. Among the factors identified to influence dropouts in this study, the prominent ones include poverty, low level of parental education, corporal punishment, no interest in schooling and long distances to school, poor performance and poor attitude of teachers. The phenomenon of dropping out of school has serious socioeconomic implications such as unemployment and its related social vices, increased dependency ratio and increased numbers of child marriages in the rural areas.

Holistic efforts are required in finding solutions to the dropout phenomenon. All stakeholders including the Ghana Education Service and school authorities, the caregivers or parents and the students themselves should be involved in seeking solutions to dropouts. Some government interventions such as school feeding programme should be implemented since literature shows that such programmes have resulted in increased enrolment (Abotsi, 2013) and retentions of students in school. None of the schools in the study area benefited from the national school feeding programme. Providing means of transportation in these communities will contribute to finding solutions to the dropout problem. Some of the factors identified to influence dropout included corporal punishment but unfortunately, the teachers were not included in the study. This is the limitation of the study. It is recommended that future studies on the subject of dropout should include the teaching staff.

Acknowledgement

Our acknowledgement goes to all household members who agreed to participate in the study.

References

- Abotsi, A.K. (2013). Expectations of school feeding programme: Impact on school enrolment, attendance and academic performance in elementary ghanaian schools. British Journal of Education, Society & Behavioural Science, 3(1), 76-92.

- Akyeampong, K. (2009). Revisiting free compulsory universal basic education in ghana. Comparative Education, 42(2), 175-195.

- Amoako, G.Y. (2000). Perspective on Africa’s Development. New York: United Nations Publication.

- Ampiah, J.G. & Adu-Yeboah, C. (2009). Mapping the incidence of school dropouts: A case study of communities in Northern Ghana. Comparative Education, 45(2), 219-232.

- Ananga, E. (2011). Dropping out of School in Southern Ghana: The Push-out and Pull-out Factors. Create Pathways to Access. Brighton: University of Sussex.

- Awedoba, A.K., Yoder, P.S., Fair, K. & Gorin, S. (2003). Household Demand for Schooling in Ghana. Calverton, MaryLand USA: ORC Macro.

- Baldwin, J.R. & Beckstead, D. (2003). Knowledge Workers in Canada’s Economy, 1971-2001. Analytic Paper for Statistics Canada, Micro-Economic Analysis Division. 11-624-MIE-No. 004.

- Brimmer, M.A. & Pauli, L. (1971). Wastage in Education: A World Problem. Paris: UNESCO, IBE.

- Brown, P. & Park, A. (2002). Education and poverty in rural China. Economics of Education Review, 21(6), 523-541.

- Caraway, K., Tucker, C.M., Reinke, W.M. & Hall, C. (2003). Self- efficacy, goal orientation and fear of failure as predictors of school engagement in high school students. Psychology in the Schools, 40(41), 417-427.

- Colclough, C., Rose, P. & Tembon, M. (2000). Gender inequalities in primary schooling: The roles of poverty and adverse cultural practice. International Journal of Educational Development, 20, 5-27.

- Coley, R.J. (1995). Dreams deferred: High school dropouts in the United States. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service, Policy Information Centre.

- Dachi, H.A. & Garrett, R.M. (2003). Child labour and its impact on children’s access to and participation in primary education: A case study from Tanzania. London: DFID.

- Devine, J. (1996). Maximum security: The culture of violence in inner-city schools. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Evans, I.M., Chicchelli, T., Cohen, M. & Shapiro, N.P. (1995). Staying in school: Partnerships for educational change. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. brooks publishing co.

- Filmer, D. & Pritchett, L. (2004). The effect of household wealth on educational attainment around the world: Demographic and health survey evidence. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Galor, O. & Moav, O. (2003). Das Human Capital: A theory of the demise of class structure (Brown University Working Paper).

- Ghana Statistical Services. (2013). Ghana-Population And Housing Census 2010, Regional Analytical Report - Brong Ahafo Region.

- Ghana Statistical Services. (2014a). Ghana-Population And Housing Census 2010, District Analytical Report - Wenchi Municipality.

- Ghana Statistical Services. (2014b). Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 6 (GLSS6).

- Goldin, C. (2001). The human capital century and american leadership: Virtues of the past. Journal of Economic History, 61(2), 263-292.

- Grant, M. & Hallman, K. (2006). Pregnancy related school dropout and prior school performance in South Africa. New York: Population Council.

- Hankivsky, O. (2008). Cost estimates of dropping out of high school in Canada. Retrieved December 1, 2017, from http://www.ccl-cca.ca/pdfs/OtherReports/CostofdroppingoutHankivskyFinalReport.pdf

- Harber, C. (2014). Education and International Development, Theory Practices and Issues. The role of education in Development. United Kingdom: Symposium Books.

- Hunt, F. (2008). Dropping out from school: A cross country review of literature. In Create Pathways to Access Research Monograph No. 20. Brighton: University of Sussex.

- Hunter, N. & May, J. (2003). Poverty, shocks and school disruption episodes among adolescents in South Africa (CSDS Working paper No. 35).

- Kolstad, A.J. & Owings, J.A. (1986). High school dropouts who change their minds about school. Washington, DC: Office of Educational Research and Improvement.

- Kuznets, S. (1955). Economic growth and income inequality. The American Economic Review, 45, 1-28.

- Lamb, S., Markussen, E., Teese, R., Sandberg, N. & Polesel, J. (2011). School dropout and completion: International comparative study in theory and policy. London: Springer Science Business Media.

- Lucas, R.E.J. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3-42.

- Lucas, R.E.J. (1993). Making a Miracle. Econometrica, 251-272.

- Malhotra, A. (2010). The causes, consequences and solutions to forced child marriage child marriage in the developing world. Retrieved December 1, 2017, from https://www.icrw.org/files/images/Causes-Consequences-andSolutions-to-Forced-Child-Marriage-Anju-Malhotra-7-15-2010.pdf

- Ministry of Education. (2014). Secondary education improvement project: Project implementation manual (SEIP), project implementation manual. Ghana: Ministry of Education.

- Pittman, R.B. (1986). Importance of personal, social factors as potential means for reducing high school dropout rate. The High School Journal, 70, 7-13.

- Psacharopoulos, G. & Woodhall, M. (1985). Education and Development: Analysis of investment choices. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Reddy, A.N. & Sinha, S. (2010). School dropouts or pushouts? Overcoming barriers for the right to education. (C. R. M. 40., Ed.). National University of Educational Planning and Administration (NUEPA).

- Rolleston, C. (2009). The determinant of exclusion: Evidence from the ghana living standards surveys 1991-2006. Comparative Education, 42(2), 197-218.

- Rumberger, R.W. (1983). Dropping out of high school: The influence of race, sex and family background. American Educational Research Journal, 20(2), 199-220.

- Rumberger, R.W. (1987). High School Dropouts: A review of issues and evidence. Review of Educational Research, 57(2), 101-121.

- Rumberger, R.W. (2001). Why should students drop out of school and what can be done. A paper prepared for the Conference, Dropouts in America: How severe is the Problem? What do we know about intervention and prevention? Harvard: Harvard University.

- Steinberg, L., Blinde, P.L. & Chan, K.S. (1984). Dropping out among language minority youth. Review of Educational Research, 54, 113-132.

- Suh, S. & Suh, J. (2007). Risk factors and levels of risk for high school dropouts. Professional School Counseling, 10(3), 297-306.

- Tidwell, R. (1988). Dropouts speak out: Qualitative data on early school departures. Adolescence, 23(92), 939-954.

- UNICEF (2012). Global initiative on out-of-school children. GHANA COUNTRY STUDY.

- UNICEF (2015). Child marriage. Retrieved November 30, 2017, from https://www.unicef.org/ghana/REALLY_SIMPLE_STATS_-_Issue_5(3).pdf

- Wehlage, G.G., Rutter, R.A., Smith, G.A., Lesko, N. & Fernandez, R.R. (1989). Reducing the risk: Schools as communities of support. New York: Falmer Press.

- Wehlage, G.G. & Rutter, R. A. (1989). Dropping: How much do school contribute to the problem. Teachers College Record, 87, 374-392.