Research Article: 2022 Vol: 26 Issue: 6S

Documentary analysis of primary education curricula for the development of entrepreneurship: competences and active methodologies

Jessica Paños Castro, University of Deusto

Leire Markuerkiaga, Mondragon University

Maria Jose Bezanilla, University of Deusto

Citation Information: Paños-Castro J., Markuerkiaga L., & Bezanilla M. J (2022). Documentary analysis of primary education curricula for the development of entrepreneurship: Competences and active methodologies. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 26(S6), 1-18.

Abstract

Entrepreneurial competence is a key competence for personal development, social inclusion and active citizenship. It is important that primary school teachers develop this competence and that it is therefore included in the initial training of future teachers provided by universities. The objective of this research is to sanalyse the competences and teaching methodologies of Primary Education degrees in Spain in order to determine the extent to which entrepreneurship is included in their curricula. For this purpose, a documentary and content analysis has been carried out of the 68 curricula that were entered into the Spanish Registry of Universities, Centres and Degrees for the academic year 2021-22. A total of 6262 competences and 655 methodologies were examined. The results indicate that 33.82% of the faculties include entrepreneurial competence either as a general or a transversal competence, relating it to entrepreneurial culture, entrepreneurial spirit and project design. The most common methodologies used in these university programmes are tutorials, lectures, teamwork, debates and case studies. Since entrepreneurial competence involves a subset of attitudes, aptitudes and skills, 909 competences in the curricula were found to be linked to entrepreneurial competence, notably including planning, innovation, oral and written communication, and problem solving. However, skills such as financial and economic literacy, mobilising resources, self-awareness and self-efficacy, vision, valuing ideas, and ethical and sustainable thinking were not covered in the curricula analysed.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship, Active Methodologies, Entrepreneurship Competence, Primary Education, Study Plans, Teacher Training.

Introduction

The first suggestion of what the term 'entrepreneur' might mean appeared in the writings of Cantillon (1755), which described an entrepreneur as a businessman who agrees to pay a fixed sum of money to the owner of a farm or land with no certainty of profit. Later, other economists such as Say, Schumpeter, Clark and Knight, among others, developed different theories and points of view based on economics, psychology, sociology and business management (Teran Yépez & Guerrero Mora, 2020). However, although a few years have passed, entrepreneurship is an area of study that is currently still being developed (De la Torre et al., 2019).

Sometimes the terms 'entrepreneurship', 'entrepreneurial mindset', 'sense of initiative and entrepreneurial spirit', and 'sense of initiative and business spirit' are used interchangeably (Pereira, 2007). This may be linked to the fact that the English term 'entrepreneur' derives from the French word 'entrepreneur', from Middle French 'entreprendre' (undertake), which in turn comes from the Latin term 'imprehendere', related to 'prendere' (hold, wield) (De la Torre et al., 2019). Sanwel (2010) argued that it is difficult to adopt a single definition because entrepreneurship is a complex phenomenon. This is also the case with the approaches to teaching entrepreneurship, in which the terms educating about, educating for, and educating through entrepreneurship are used interchangeably (Sanwel, 2010).

While the concept of entrepreneurship has traditionally been related to business creation and the economics based view has prevailed, a wider view currently encompasses the social, cultural, economic and productive perspectives (Rodriguez Ramirez, 2009). The university should therefore enable ‘each and every student to transversally acquire the necessary skills and competencies in their education process so that they can become visionary professionals who create new opportunities and companies’ (Vasquez, 2017).

From the 1970s onwards, driven by the rise in Information and Communication Technologies, the decline in public funding for research and the slowdown in economic growth, universities were compelled to establish a more solid relationship with the business world (Beraza & Rodriguez, 2007). This approach is also known as the Triple Helix model, the Entrepreneurial University or the third mission, where the university plays a key role in the business government relationship by fostering innovation in organisations as a source of knowledge creation (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 2000).

With the Bologna process and the development of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) in 1999 (Bologna Declaration, 1999), a paradigm shift has been needed in the teaching learning process where students face situations, either real or simulated, to acquire and develop skills (De Miguel, 2005). It is critical to make a wise choice of teaching methods and techniques, since they are considered one of the most effective factors in learning (Hamurcu & Canbulat, 2019).

Entrepreneurship is a transversal competence that applies to all spheres of life, including the personal, social, cultural and business spheres (Bacigalupo et al., 2016). In the twenty first century, students face constant changes in labour markets, which force them to compete for a limited number of vacancies or opt for self-employment (Sanwel, 2010). Specifically, in the last year ‘youth unemployment has increased by 64,700 among young people under 25 years of age (13.3%) and by 154,000 among young people up to 29 years of age (17.1%)’ in Spain (Ministry of Labor and Social Economy, 2021). Therefore, entrepreneurial people are required to generate jobs, act as agents of change and drivers of innovation, and build competitiveness (De la Torre et al., 2019).

Arruti et al. (2021) conducted a study with the five Jesuit universities in Spain which analysed the entrepreneurial competences included in the curricula of the degree in Primary Education. They found that the skills that were most often mentioned were related to mobilising others, planning and management, working with others, and creating an entrepreneurial learning environment that enhances autonomy.

This study also suggested that some future avenues of research could involve carrying out more detailed studies of all Primary Education degrees from a methodological perspective and analysing whether entrepreneurial competences had a presence in the rest of the Spanish universities. The research presented below examines the competences and methodologies used in all degrees in Primary Education in Spain to determine the extent to which entrepreneurship is part of the curricula.

Entrepreneurial Competencies in the Educational Field

DeSeCo (OCDE, 2003) defines competency as the ability to meet complex demands and tackle diverse tasks appropriately. The significance of entrepreneurship in Spain has gradually increased under the different education rules and regulations that have been enacted over the past two decades. The Organic Law on Quality of Education (Jefatura del Estado, 2002) recognised the importance of strengthening the entrepreneurial spirit by fostering self-confidence, critical thinking, personal initiative, the ability to plan, decision making and responsibility taking. In 2006, the Organic Law of Education (Jefatura del Estado, 2006) reaffirmed the key role of creativity, personal initiative, self-confidence, critical thinking and the entrepreneurial spirit. The objectives of the Organic Law for the Improvement of Education Quality (Jefatura del Estado, 2013) also highlighted the significance of entrepreneurship as a transversal competence.

There are seven key competences in the Spanish Educational System, notably including ‘a sense of initiative and an entrepreneurial spirit’ in the stages of Primary Education, Compulsory Secondary Education and Baccalaureate, as well as in lifelong learning (Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports, 2015).

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union (Official Journal of the European Union, 2006) have also considered the ‘sense of initiative and entrepreneurship’ to be a key competence ‘which all individuals need for personal fulfilment and development, active citizenship, social inclusion and employment’. This is related to creativity, innovation and risk taking, the ability to plan and manage projects (involving skills such as the ability to plan, organise, manage, lead and delegate, analyse, communicate, de brief, evaluate and record), the ability to identify opportunities, initiative, proactivity, motivation and determination. However, in 2017 the European Commission (Official Journal of the European Union, 2018) began a public consultation to review this framework. In this new consultation, special attention continued to be given to entrepreneurship competence, creativity and the sense of initiative.

The sense of initiative and entrepreneurial spirit involves transforming ideas into actions, integrating problem solving skills, planning, decision making, the ability to think creatively, communication, and risk management, adapting to change, identifying opportunities and managing uncertainty, among others (Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport, 2015). Entrepreneurs have been characterised in various different ways, partly because there is no widely accepted definition of the term ‘entrepreneur’. However, the most frequent characteristics attributed to entrepreneurs by behavioural specialists are initiative, innovation, leadership, perseverance, optimism, need for achievement, self-confidence, tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty, and creativity, among others (Pereira, 2007).

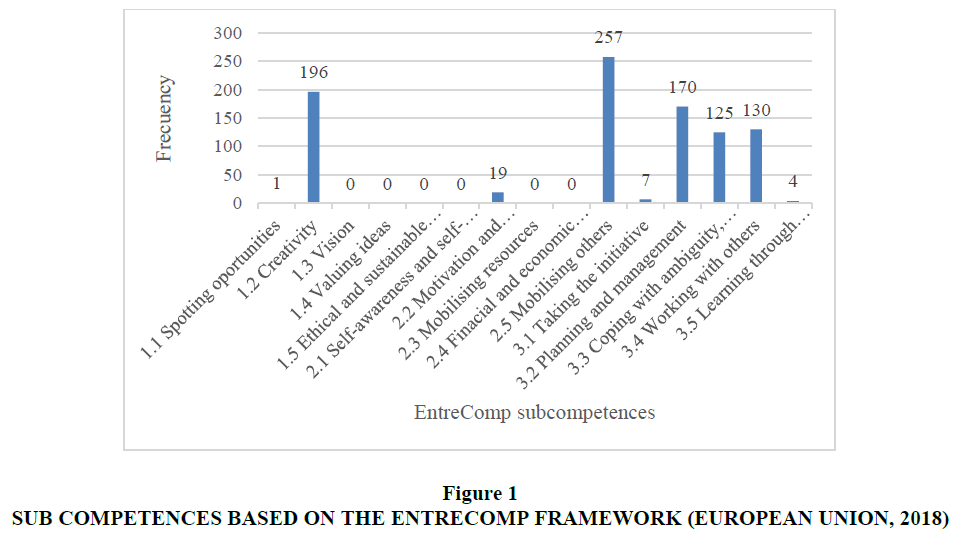

As there is no unanimous agreement on which attitudes, aptitudes and skills are related to entrepreneurial competence, the European Commission developed the European Framework of Entrepreneurial Competences, known as EntreComp (European Union, 2018). This Framework identified 15 sub competences: spotting opportunities, creativity, vision, valuing ideas, ethical and sustainable thinking, self-awareness and self-efficacy, motivation and perseverance, mobilising resources, financial and economic literacy, mobilising others, taking the initiative, planning and management, coping with uncertainty, ambiguity and risk, working with others, and learning through experience.

Education in entrepreneurship competences is essential, as it has been found to be one of the decisive areas for developing entrepreneurship, the entrepreneurial spirit, and entrepreneurial attitudes and skills (de la Torre Cruz et al., 2016).

Active Methodologies for Developing Entrepreneurship

Methodologies are ‘the scientifically based teaching strategies that teachers propose in their classroom so that students can achieve certain learning outcomes’ (Fortea, 2019). Sometimes the definition of methodology is ambiguous, since related concepts such as model and method overlap.

There are different classifications of teaching methods (see Table 1). Based on the participation of teachers and students, methodologies are usually grouped into two types: ‘traditional’ (teacher focused methodologies, basically lecture based), and ‘modern’ (or student centred methodologies) (Fortea, 2019). Fernández (2006) proposed a classification based on three categories: methods based on different forms of lectures; discussion and/or teamwork oriented methods; and methods based on individual learning or autonomous work. Another classification established a distinction between active (those which require students to work actively, which favours participation) and passive methodologies (Labrador & Andreu, 2008 cited by Silva & Maturana, 2017). Gargallo et al. (2011) underlined two major models. On the one hand, the knowledge transmission model or teaching centred model, also known as the teacher centred model; and on the other, the learning facilitation model or learning centred model, also known as the student centred model. Chiang et al. (2013), for their part, classified teaching styles into four typologies: open (teachers constantly innovate and promote active learning), formal (teachers follow strict planning, promoting reflective learning), structured (teachers engage in coherent and structured planning, promoting theoretical learning) and functional (teachers give less value to theoretical content than to procedural and practical content). Lastly, Traver et al. (2005) proposed the following classification: teacher centred teaching, student centred teaching, process centred teaching, and product centred teaching.

| Table 1 Differences Between Teaching Methodologies | |

| Author(s) | Classification |

| Traver et al. (2005) | Teacher centred teaching Student centred teaching Process centred teaching Product centred teaching |

| Fernández (2006) | Based on different forms of lectures Oriented towards discussion and/or teamwork Based on individual learning or autonomous work |

| Labrador & Andreu (2008, cited by Silva & Maturana, 2017) | Active Passive |

| Gargallo et al. (2011) | Knowledge transmission model or teaching centred model, also known as the teacher centred model. Learning facilitation model or learning centred model, also known as the student centred model. |

| Chiang et al. (2013) | Open Formal Structured Functional |

| Fortea (2019) | Traditional (teacher centred) Modern (student centred) |

Various Spanish bodies and organisations in recent years have put forward methodologies for adapting to the EHEA and fostering innovation. For example, the Commission for Teaching Innovation in Andalusian Universities (2005) emphasised a set of methods which included presentations, lectures, projections and large group activities, core teaching group, group work, and individual work.

For its part, the Commission for Updating University Education Methodology identified some recommendations to promote individualised tutoring, encourage activities outside the classroom and encourage collaborative work, among others. In 2006, a study by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science noted that there was a need to use more active methodologies and give greater prominence to the student. According to this study, universities in Spain still mainly use lecture and content based approaches instead of promoting competences, tutorial sessions and active methodologies.

Annex 2 of the guidelines to facilitate the development of methodological strategies to use competence based work in the classroom, provided by Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports (2015), highlighted that motivating students and stimulating their curiosity is a key aspect of any teaching learning process.

To do so, the use of active, real and contextualised methodologies was recommended, including project based learning, centres of interest, case studies and problem based learning. The guidelines also emphasised the need to employ varied teaching materials and resources such as the portfolio and Information and Communication Technologies. For its part, the Official Journal of the European Union (2018) noted that in order to acquire the entrepreneurship competence, traineeships in companies, business simulations and entrepreneurial project based learning should be used, and that entrepreneurs should be invited to visit educational institutions.

While there is no consensus on the teaching methods to be used for the development of entrepreneurship, ‘it has been shown that passive, unidirectional and teacher centred methodologies are not effective per se’ (Castro, 2017). In summary, those methodologies that are most student centred are especially suitable for achieving objectives related to long term memorisation, developing reasoning, motivation development, and transfer of, or generalised, learning (Fortea, 2019), thus encouraging learners to take a leading, proactive role (Vasquez, 2017).

Planning of Primary Education Degree Programmes

The teaching profession in Spain is regulated (Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports, 2007a) by ORDER ECI/3857/2007 (Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports, 2007b), which establishes twelve basic competences that all students must acquire by the end of their undergraduate degree. In the degree in Primary Education, these are:

1. Being acquainted with the curricular areas of Primary Education, the interdisciplinary relationship between them, the evaluation criteria and the body of didactic knowledge around the respective teaching and learning procedures.

2. Designing, planning and evaluating teaching and learning processes, both individually and in collaboration with other teachers and professionals from the institution.

3. Effectively addressing language learning situations in multicultural and multilingual contexts. Encouraging reading of, and critical commentary on, texts from the various scientific and cultural domains contained in the school curriculum.

4. Designing regulated learning spaces in diverse contexts that are aimed at gender equality, equity and respect for human rights, which make up the values of citizenship education.

5. Promoting positive relationships within and outside the classroom, solving disciplinary problems and contributing to the peaceful resolution of conflicts. Stimulating and valuing effort, perseverance and personal discipline in students.

6. Being acquainted with the organisation of primary schools and the diverse actions involved in their operation. Performing tutoring and guidance roles to support students and their families, attending to the unique educational needs of students. Assuming that the teaching role requires improving, updating and adapting to scientific, pedagogical and social changes throughout life.

7. Collaborating with the different sectors of the education community and the social environment. Assuming the educational dimension of the teaching role and promoting democratic education for active citizenship.

8. Maintaining a critical and autonomous relationship with respect to knowledge, values and public and private social institutions.

9. Valuing individual and collective responsibility in achieving a sustainable future.

10. Reflecting on classroom practices to innovate and improve teaching. Acquiring habits and skills for autonomous and cooperative learning and promoting it among students.

11. Being acquainted with and applying Information and Communication Technologies in the classroom. Selectively discerning audio visual information that contributes to learning, civic education and cultural wealth.

12. Understanding the role, potential and limits of education in today's society and the core skills concerning primary schools and their professionals. Being acquainted with models of quality improvement applicable to educational institutions.

The Spanish Ministry of Education also has also set minimum specific competences for professional qualifications. ORDER ECI/3857/2007 (Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports, 2007b) stipulates the compulsory modules that these degree programmes must include, assigning a minimum number of credits to them. These are core training (60 ECTS), disciplinary didactics (100 ECTS) and practicum (50 ECTS, a module that contains the End of Degree Project). Specialised modules may be proposed which account for 30 and 60 European credits. It should be noted that no specific modules or sub modules are established in terms of subjects or areas of knowledge to be covered, which are left at the discretion of universities (Jiménez et al., 2012).

Prior to preparing a curriculum conducive to a degree, each university is required to prepare a report to apply for its degree programme to be approved. The Council of Universities then approves the curricula after it has been authorised by the relevant Autonomous Region in Spain, and later the Ministry of Universities grants official status to the degree.

Once a degree has obtained official status and this has been published in the Spanish Official Journal, it is entered into the Registry of Universities, Institutions and Degrees (hereinafter, RUCT) where the description of the degree, competences, application procedures and admission criteria, teaching plans and implementation schedule are detailed (Ministry of Universities, 2021). As it is a regulated profession, universities must meet some minimum requirements when preparing the report for approval. These requirements are governed by Order ECI/3857/2007 (Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports, 2007b), of 27 December 2007. They fundamentally concern three aspects of the report: the name of the degree, the objectives and competences pursued and the learning structure (Jiménez et al., 2012).

The Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports (Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports, 2008) established the guidelines for university teaching and stressed the diversity of student centred teaching learning methodologies.

Objectives of the Study

The general objectives of this study are:

1. To examine the entrepreneurial competence and the entrepreneurial sub competences of Primary Education degrees in Spain.

2. To analyse the teaching methodologies of Primary Education degrees in Spain.

The specific objective is:

1. To analyse the entrepreneurial sub competences based on the EntreComp Framework.

Methods

First, the RUCT was accessed, particularly, the section on the name of the academic degree, where 'Primary Education Graduate' was selected. A total of 68 curricula were analysed for those universities that offered Primary Education degrees in Spain in the 2021 2022 academic year. This process involved conducting a documentary and content analysis. The units of analysis were the 655 teaching methodologies and the 6262 competences identified in the curriculum documents. The categories of analysis were the variety of methodologies and sub competencies of EntreComp.

In order to collect the information, we first looked for the number of universities offering a degree in Primary Education. Then, the methodologies and competencies (general, specific and transversal) of the curricula were copied into an Excel document. For the analysis of the information, researcher triangulation was used, that is, the analysis was carried out by three researchers from two different disciplines to reduce bias and add consistency to the findings.

The competencies have been analyzed and classified based on the EntreComp framework (European Union, 2018), and the teaching methodologies have been grouped by their typology.

Results

The four types of competences included in the curricula were analysed in order to meet to the first objective (to examine the entrepreneurial competence and sub competences of Primary Education degrees in Spain). These competences are basic (shared by all curricula for Primary Education degrees, since they are regulated by Royal Decree 1393/2007) (Ministry of Education and Science, 2007c)), general (common to most degrees), transversal (common to all students of the same university or institution) and specific (characteristic of a given field or degree) (ANECA, 2021). In total, 6,262 competences were analysed, of which 997 (15.92%) were general competencies, 343 (5.48%) were transversal competencies and 4,922 (78.6%) were specific ones. Basic competencies are predetermined, as set out in ORDER ECI/3857/2007 (Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports, 2007b). Only 23 faculties included the entrepreneurship competence in their curricula (that is, 33.82%), either as a general competence (43.47%) or as a transversal competence (56.53%). This competence was considered to be essential for all university students when identified as transversal. As shown in Table 2, the entrepreneurship competence is outlined in different ways, as some faculties gave importance to the entrepreneurial culture, others to the entrepreneurial spirit and others to project design.

| Table 2 Analysis of the Entrepreneurship Competence in the Curricula of Primary Education Degrees | |

| GENERAL COMPETENCES | |

| Definition of this competence | Frequency |

| Initiative and an entrepreneurial spirit | 3 |

| Planning, organising and managing processes, projects and information; problem solving. Having initiative, an entrepreneurial spirit and the ability to generate new ideas and actions. | 2 |

| Understanding the importance of entrepreneurial culture and being acquainted with the resources available to entrepreneurs. | 1 |

| Promoting an entrepreneurial spirit. | 1 |

| Being acquainted with the traits that make up the entrepreneurial spirit and its different levels of proficiency; and achieving its full development. | 1 |

| Being able to undertake and complete projects autonomously, professionally and expertly. The achievement of this competence entails being capable of designing a work plan and complete it within the specified schedule. It also involves carrying it out with perseverance and flexibility, anticipating and overcoming the difficulties that may arise and making any necessary changes in a timely, professional and expert manner, turning adversities into opportunities to learn and improve. | 1 |

| Learning to learn, a competence linked to learning, the ability to undertake and organise learning, either individually or in groups, according to each individual's needs, as well as being aware of the methods and identifying the opportunities available. | 1 |

| TRANSVERSAL COMPETENCES | |

| Initiative and an entrepreneurial spirit | 3 |

| Promoting active job search habits and entrepreneurial skills | 2 |

| Valuing the importance of leadership, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation in professional performance | 2 |

| Applying basic knowledge of entrepreneurship and professional environments | 1 |

| Generating proposals for entrepreneurship, innovation, research and leadership in professional practice | 1 |

| Projecting the values of entrepreneurship and innovation in the course of one's personal academic and professional path through contact with different practices and motivation towards professional development. | 1 |

| Acquiring leadership skills, initiative and an entrepreneurial spirit, especially in problem solving and decision making. | 1 |

| An entrepreneurial culture | 1 |

| Entrepreneurial spirit: Ability to undertake and carry out activities that generate new opportunities, anticipate problems or bring improvements. | 1 |

| N = 23 | |

Another objective of the study was to examine the sub competences that are related to the entrepreneurial competence following the EntreComp framework (European Union, 2018). Only 242 of the general competences (3.8%) were related to entrepreneurial sub competences (Table 3). The most mentioned were planning, innovation, oral and written communication, and teamwork. Following the EntreComp framework (European Union, 2018), the competences in Table 3 are grouped into the following areas: Resources (N=82), into action (N=91), and Ideas and opportunities (N=66). “Leadership and teamwork” and "Effective problem solve and decision making" have not been included in this grouping because they duplicate areas.

| Table 3 Sub Competences Related to the Entrepreneurial Competence in the General Competences | |

| GENERAL COMPETENCES | Frequency |

| Planning | 40 |

| Innovation | 38 |

| Oral and written communication | 35 |

| Teamwork | 27 |

| Effort and perseverance | 15 |

| Problem solving | 10 |

| Oral communication | 9 |

| Written communication | 8 |

| Adaptability | 8 |

| Decision making | 6 |

| Leadership | 6 |

| Creativity | 4 |

| Interpersonal skills | 4 |

| Organisation and planning skills | 4 |

| Creative thinking | 3 |

| Learning to learn | 3 |

| Initiative, innovation and creativity | 2 |

| Divergent thinking | 2 |

| Innovation and creativity | 2 |

| Leadership and teamwork | 2 |

| Self-improvement | 1 |

| Effective problem solving and decision making | 1 |

| Commitment | 1 |

| Organisation skills | 1 |

| Autonomy | 1 |

| Initiative, self-motivation and perseverance | 1 |

| Creative and innovative problem solving | 1 |

| Interpersonal communication | 1 |

| Giving innovative answers | 1 |

| Commitment to innovation | 1 |

| Self-motivation, achievement orientation and leadership | 1 |

| Achievement motivation | 1 |

| Identifying needs | 1 |

| Initiative | 1 |

| N = 242 | |

Regarding the transversal competences in the curricula, 99 entrepreneurial sub competences were mentioned (1.5%). The sub competences that were most often found included oral and written communication, teamwork and problem solving (Table 4).

| Table 4 Sub Competences Related to the Entrepreneurial Competence in Transversal Competences | |

| TRANSVERSAL COMPETENCES | Frequency |

| Oral and written communication | 39 |

| Teamwork | 18 |

| Problem solving | 10 |

| Adaptation to change | 5 |

| Decision making | 5 |

| Creativity | 4 |

| Leadership | 4 |

| Organisation and planning skills | 4 |

| Innovation | 3 |

| Interpersonal skills | 2 |

| Learning to learn | 1 |

| Initiative | 1 |

| Innovation and creativity | 1 |

| Planning skills | 1 |

| Creativity, initiative and proactivity | 1 |

| N = 99 | |

Following the EntreComp framework (European Union, 2018), the competences in Table 4 are grouped into the following areas: Resources (N=45), into action (N=34), and Ideas and opportunities (N=19). “Creativity, initiative and proactivity” has not been included in this grouping due to duplication of areas.

Lastly, the description of 568 specific skills (9.07%) mentioned entrepreneurial sub competences, notably including oral and written communication, innovation, planning and problem solving (Table 5).

| Table 5 Sub Competences Related to the Entrepreneurial Competence in Specific Competences | |

| SPECIFIC COMPETENCES | Frequency |

| Oral and written communication | 153 |

| Innovation | 136 |

| Planning skills | 107 |

| Problem solving | 90 |

| Teamwork | 64 |

| Oral communication | 7 |

| Leadership | 6 |

| Decision making | 2 |

| Written communication | 1 |

| Social skills | 1 |

| Creative thinking | 1 |

| N = 568 | |

Following the EntreComp framework (European Union, 2018), the competences in Table 5 are grouped into the following areas: Resources (N=167), into action (N=174), and Ideas and opportunities (N=227).

If all the competences (general, transversal and specific) are grouped according to the EntreComp framework (European Union, 2018), it is clear that a number of sub competences were the most mentioned: 2.5 Mobilising others, 1.2 Creativity, 3.2 Planning and management, 3.3 Coping with ambiguity, uncertainty and risk, and 3.4 Working with others. However, a number of sub competencies were not included in the curricula, namely 1.3 Vision, 1.4 Valuing ideas, 1.5 Ethical and sustainable thinking, 2.1 Self-awareness and self-efficacy, 2.3. Mobilising resources and 2.4. Financial and economic literacy (Figure 1).

In connection with the second objective, as can be seen in Table 6, the methodologies that were most commonly included in the Primary Education degree curricula were tutorials, lectures, case studies, and seminars and workshops. It is worth noting that a variety of teaching learning methodologies (specifically 127) was found, with an average of 10 methodologies per university.

| Table 6 Methodologies that were the Most Mentioned in the Curricula of Primary Education Degrees | |||

| Types of methodologies | Frequency | Types of methodologies | Frequency |

| Tutorials (some universities differentiated between individual and group based, online, and face to face). Academic tutorials. End of Degree Project (EDP) and internship related tutorials. Tutorials to monitor learning outcomes. EDP follow up and supervision. | 62 | Research projects/Learning based on research and inquiry/Writing an educational research paper | 6 |

| Lectures/presentation sessions/lecturer's presentation/theoretical sessions/oral explanation of contents/presentation sessions/theoretical presentations/interactive theoretical presentations | 60 | Fieldwork | 5 |

| Teamwork/collaborative learning/cooperative learning | 42 | Service Learning | 4 |

| Debates/colloquia/talks/video discussions/round tables/conferences/scientific and/or informative events | 35 | Co assessment | 4 |

| Case studies/Case based learning/Case analysis/Case method (real or simulated) | 31 | Self-assessment | 4 |

| Seminars and workshops | 28 | Introductory/preliminary activities | 4 |

| Use of computer resources (discussions, chats, online classrooms, platforms...) | 27 | Project design | 4 |

| Practical activities carried out in educational institutions/external internships/practical application of knowledge in educational institutions/work outside the classroom | 25 | Concept maps/diagrams | 4 |

| Project Based Learning/Project Oriented Learning | 21 | Reflective learning | 3 |

| Practical classes/practical activities | 20 | Face to face work in the classroom | 3 |

| Problem Based Learning | 19 | Research and diagnostic techniques | 3 |

| Autonomous/individual learning/work | 18 | Previous learning work | 3 |

| Problem solving/Solving exercises and problems | 17 | Heteroevaluation | 2 |

| Reading of texts/documents/scientific articles/text analyses/Annotated reading of reference materials | 16 | Preparing and defending the EDP | 2 |

| Simulations and role playing games | 15 | Challenge based Learning | 2 |

| Presentations/Oral presentations (both individual and in groups) | 15 | Experiential learning | 2 |

| Literature searches/Literature queries/Analysis of documentary sources/Searches for information | 14 | Glossaries | 2 |

| Laboratory work/laboratory practice | 12 | Theoretical practical classes | 2 |

| Educational exams/tests | 11 | Question and answer sessions | 2 |

| Portfolios | 9 | Reports | 2 |

| Videos/audio visual materials/watching videos/listening to documents | 8 | Essays | 2 |

| Apprenticeship contract | 7 | Supervised school classroom observation | 2 |

| Individual/autonomous work | 7 | Large group interaction | 2 |

| Personal/individual study/subject study | 7 | Small group interaction/small groups | 2 |

| Assignment preparation | 5 | Preparation of teaching programmes | 2 |

| Visits/outings to organisations/places/cultural institutions/exhibitions/museums | 6 | ||

Other teaching methodologies were only included once in the curricula, but are worth noting:

- Guest speakers

- Writing centre

- CLIL methodology

- Design Thinking

- Communicative approach to language teaching

- Action research

- Active learning methodologies

- Guidance

- Practical artistic or physical/sports activities

- Learning by doing

- Teaching methods based on different forms of expression

- Presentation of teaching resources

- Micro teaching

- Application of programming techniques

- Assignment preparation guidelines

- Assessment templates

- Interpretation of documents and materials

- Development of materials and resources

- Participatory classes

- Observation and self-observation of teaching practice

- Design and application of materials

- Ongoing learning

- Strategies for the knowledge and development processes related to a subject or to Work Units or Projects

- Design of classroom activities and teaching strategies

- Regulatory analysis

- Other options

- Teaching hours

- Subsequent learning

- Work

- Guided learning (student teacher interaction)

- Analysis of texts, audio visual materials and sociological data

- Observation of student work

- Professional supervision

- Experiential context

- Conceptualisation

- Active experimentation

- Vicarious learning (modelling)

- Systematic and guided observation

- Evaluation projects

- Intervention projects

- Didactic artistic projects

- Analysis and evaluation of materials

- Review of activities

- Book review

- Summary

Discussion

The results section has shown that lectures are still one of the most commonly used methodologies in the Spanish university system; however, there is a growing use of active methodologies such as case studies, problem and project based learning, and cooperative/collaborative learning, among others. The study by Cano et al. (2014) found that the teaching methodologies in the EHEA, the most common being the lecture, followed by seminars, practical classes, case studies, and solving exercises and problems, are largely used in conjunction with each other. Cameron (2017), for his part, maintained that, although many teaching methods are currently used, there seems to be a preference for traditional methodologies, where textbooks and lecturers prevail. Despite this, there is a great variety of teaching methodologies being employed.

Whereas passive methodologies have been in the classroom for much longer, their excessive use should be avoided. Zabalza (2011) argued that lecturers tend to use those methodologies with which they feel safer. Lectures have been widely accepted methodologies because they do not involve major effort.

There is no single valid teaching methodology, as the best method is, in fact, a combination of methods (Zabalza, 2011). Lectures must therefore share the limelight with other more effective strategies and ways of teaching and learning (Ministry of Universities, 2021; Journal of the European Union, 2014). In this way, students will not lose focus or become demotivated (Parra González, 2020), and they will instead develop autonomy, and will be capable of managing conflicts and enable creativity, reflection and cooperation, among other things (Silva & Maturana, 2017).

The university cannot be merely limited to providing knowledge and sending its graduates to the market; it should include entrepreneurship as a factor in education, so that students can choose to create their own job at the end of their degree or, if they decide to become employed by someone else, they can develop corporate entrepreneurship, since this has been shown to have a positive impact on growth, profitability, productivity and the satisfaction of agents within organisations (Santander International Entrepreneurship Center, 2017). Entrepreneurship should be implemented in education from its initial stages through to the university system, to ensure that teachers have the relevant skills to be effective in the classroom (Leite et al., 2015; Government of Spain, 2022; Manso & Thoilliez, 2015).

As Zabalza (2011) noted, changes in education occur at four levels: within political powers (through laws and regulations), within universities, within academic institutions, and within teachers themselves. Therefore, the fact that active methodologies and some entrepreneurial skills appear in the curriculum does not necessarily mean that all teachers choose to use them.

While sometimes the choice of the teaching career is vocational, due to their fondness for working with children and being of service to others, initial teacher training in entrepreneurship is necessary to have an entrepreneurial culture (Huang et al., 2020). Being an entrepreneur should never be confused with a mere calling to start a business (Manso & Thoilliez, 2015).

Conclusion

As the results of this study have shown, certain entrepreneurial sub competences are not yet covered in the Primary Education degree in Spain. Business (strategic and organisational) and motivational (commitment) skills must be developed, since they are directly related to success in business and to the development of an entrepreneurial spirit. In addition, the entrepreneurial competence is one of the generic competences of the curriculum of Primary Education. If we want children to develop this competence, future teachers should be trained at the university. As noted in Table, methodologies that were the most mentioned in the curricula of primary education degrees, the RUCT does not differentiate between teaching learning and assessment methodologies. For this reason, this distinction has not been made in this research, but for future research it could be interesting to delve deeper into this area.

Some future avenues of research may include providing a comprehensive comparison of the programmes and guidelines for the subjects in the Primary Education degree, and exploring the self-perception of university lecturers and students to study to what extent each of the skills and methodologies is developed.

References

ANECA (2021). Support Guide for the elaboration of the Verification Report of Official University Degrees.

Arruti, A., Morales, C., & Benitez, E. (2021). Entrepreneurship Competence in Pre Service Teachers Training Degrees at Spanish Jesuit Universities: A Content Analysis Based on EntreComp and EntreCompEdu. Sustainability, 13(16), 8740.

Bacigalupo, M., Kampylis, P., Punie, Y., & Van den Brande, G. (2016). EntreComp: The entrepreneurship competence framework. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union, 10, 593884.

Beraza, J. and Rodriguez, A. (2007). The evolution of the mission of the university. Journal of Business Management and Administration, 14, 25 56.

Bologna Declaration (1999). Joint declaration of the European Ministers of Education.

Cameron, L. (2017). How learning designs, teaching methods and activities differ by discipline in Australian universities. Journal of Learning Design, 10(2), 69 84.

Cano, F., García, AB, Fernández, M., Gea, M., and Diaz, M. (2014). Teaching methodology in European universities: the perception of Erasmus. Faculty. Journal of Curriculum and Teacher Training, 18(1), 307 322.

Cantillon, R. (1755). An Essay on Commerce in General.

Castro, J.P. (2017). Entrepreneurial education and active methodologies for its promotion. Interuniversity Electronic Journal of Teacher Education, 20 (3), 33 48.

Santander International Entrepreneurship Center (2017). Corporate entrepreneurship in Spain Gazelles and elephants dance without stepping on each other. Santander Universidades.

Chiang, M.T., Diaz, C., and Rivas, A. (2013). A questionnaire of teaching styles for the Higher Education teacher. Lasallian Journal of Research, 10(2), 62 68.

Commission for Teaching Innovation in Andalusian Universities (2005). Report on teaching innovation in Andalusian universities.

de la Torre Cruz, T., Rico, M.I.L., Llamazares, M.D.C.E., Cámara, M.C.P., & Eguizábal, J.A.J. (2016). The figure of the teacher as an agent of change in the configuration of entrepreneurial competence. RIFOP: Interuniversity journal of teacher training: continuation of the old Journal of Normal Schools, (86), 131 144.

De la Torre, T., Luis, M.I., Palmero, C., Escobar, M.C., and Jiménez, A. (2019). Education and entrepreneurial competence. Theoretical challenges and socio pedagogical implications. Editorial Dykinson.

De Miguel Díaz, M., Alfaro Rocher, I.J., Apodaca Urquijo, P., Arias Blanco, J.M., García Jiménez, E., Lobato Fraile, C., & Pérez Boullosa, A. (2005). Teaching modalities focused on the development of competences: guidelines to promote methodological change in the European Higher Education Area. Publications Service. Oviedo University.

Official Journal of the European Union (2014). Council conclusions of May 20, 2014, on effective teacher training.

Etzkowitz, H. and Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The dynamics of innovation: from National Systems and 'Mode 2' to a Triple Helix of university industry government relations. Research Policy, 29(2), 109 123.

European Union (2018). EntreComp: The European Entrepreneurship Competence Framework. Publications Office of the European Union.

Fernández, A. (2006). Active methodologies for skills training. Educatio Siglo XXI, 24, 35–56.

Fortea, M.Á. (2019). Teaching methods for the teaching/learning of skills. Educational Support Unit of the Jaume I University

Gargallo, B., Suárez, J., Garfella, P., and Fernández, A. (2011). The cemedepu questionnaire. An instrument for the evaluation of the teaching methodology of university professors. Studies on Education, 21, 9 40.

Government of Spain (2022). 24 reform proposals to improve the teaching profession.

González López, M.J., Pérez López, M.C., and Rodríguez Ariza, L. (2021). From potential to early nascent entrepreneurship: the role of entrepreneurial competencies. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17, 1387–1417

Hamurcu, H. and Canbulat, T. (2019). Preservice Teachers' Perceived Self Efficacy in Selection of Teaching Methods and Techniques. Pedagogical Research, 4(3), 36 43.

Huang, Y., An, L., Liu, L., Zhuo, Z., and Wang, P. (2020). Exploring Factors Link to Teachers' Competencies in Entrepreneurship Education. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 563381.

Jefatura del Estado (2002). Organic Law 10/2002, of December 23, on the Quality of Education.

Jefatura del Estado (2006). Organic Law 2/2006, of May 3, on Education.

Jefatura del Estado (2013). Organic Law 8/2013, of December 9, for the improvement of educational quality.

Jiménez, L., Ramos, F., and Ávila, M. (2012). The Spanish Universities and EHEA: A Study on the Degree Titles of Teacher in Primary Education. Formación Universitaria, 5(1), 33 44.

Leite, E., Correia, E.B., Sánchez Fernández, M.D., and Leite, E. (2015). The entrepreneurial spirit: conditions for innovation. HOLOS, 5, 278 291.

Manso, J. and Thoilliez, B. (2015). Entrepreneurial competence as a supranational educational trend in the European Union. Drone, 67 (1), 85 99.

Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports (2006). Proposals for the renewal of educational methodologies in the university.

Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports (2007a). Resolution of December 17, 2007, of the Secretary of State for Universities and Research, which publishes the Agreement of the Council of Ministers of December 14, 2007, which establishes the conditions to which the plans must adapt of studies leading to obtaining qualifications that enable the exercise of the regulated professions of Teacher of Compulsory Secondary Education and Baccalaureate, Vocational Training and Language Teaching.

Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports (2007b). Order ECI/3857/2007, of December 27, which establishes the requirements for the verification of the official university degrees that qualify for the exercise of the profession of Teacher in Primary Education.

Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports (2007c). Royal Decree 1393/2007, of October 29, which establishes the organization of official university education.

Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports (2008). Resolution of March 7, 2018, of the General Secretariat of Universities, by which instructions are issued on the procedure for the institutional accreditation of public and private university centers.

Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports (2015). Order ECD / 65/2015, of January 21, which describes the relationships between the skills, content and evaluation criteria of primary education, compulsory secondary education and high school.

Ministry of Universities (2021). Royal Decree 822/2021, of September 28, which establishes the organization of university education and the procedure for ensuring its quality.

Ministry of Labor and Social Economy (2021). Youth and labor market report. June 2021.

OCDE (2003).The definition and selection of key competencies. Executive Summary.

Official Journal of the European Union (2006). Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the council of 18 December 2006 on key competences for lifelong learning.

Official Journal of the European Union (2018). Council recommendation of 22 May 2018 on key competences for lifelong learning.

Parra Gonza´lez, M.E. (2020). Emerging methodologies for innovation in teaching practice. Octaedro.

Pereira Laverde, F. (2007). The evolution of entrepreneurship as a field of knowledge: Towards a systemic and humanistic vision. Management Notebooks, 20 (34), 11 37.

Rodriguez Ramirez, A. (2009). New perspectives to understand business entrepreneurship. Thought & Management, (26), 94 119.

Sanwel, E. (2010). Entrepreneurship education: a review of its objectives, teaching methods, and impact indicators. Education + Training, 52(1), 20–47.

Silva, J. and Maturana, D. (2017). A model proposal to introduce active methodologies in higher education. Educational Innovation, 17(73), 117 131.

Teran Yepez, E., & Guerrero Mora, A. M. (2020). Entrepreneurship theories: critical review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Espacios Magazine, 41(07).

Traver, J.A., Sales, A., Doménech, F., and Moliner, M.O. (2005). Characterization of the teaching perspectives of secondary school teachers based on the analysis of educational variables related to teaching action and thought. Ibero American Journal of Education, 36(8), 1 19.

Vasquez, C. (2017). Entrepreneurship education at university. Management Studies: International Journal of Management, (2), 121 147.

Zabalza Beraza, M.Á. (2011). Teaching methodology. Red U: university teaching magazine.