Research Article: 2019 Vol: 11 Issue: 5

Do You Fit? Supply Chain Management As A Major and Career

Xolile Antoni, Rhodes University

Tony Matchaba-hove, Nelson Mandela University

Kholiswa Mathiyase, Nelson Mandela University

Keywords

Chain Management, Interpersonal Behavior, Business Degrees, Pre-Business Students.

Introduction

The student debt associated with higher education is a growing, and significant, concern (Godfrey, 2017; Hinton and Rezin, 2018; Selingo, 2018). A recent poll found almost 50% of recent graduates would forfeit their right to vote during the next two U.S. presidential elections in exchange for erasing their student debt (Blumberg, 2017; Scipioni, 2017). And while tuition, textbooks, and room and board expenses are largely outside of the control of students, one thing they can impact is their time to graduation (e.g. Farrington, 2017). A number of universities have begun emphasizing the four year time to graduation in an effort to help limit student debt (Browne, 2018). Indeed, one study estimates that an additional two years in time to graduation could cost $300,000 (Browne, 2018). Therefore, having a planned path to graduation may facilitate the timely completion of a college degree.

For business school students, the choice of a major is a complex one. Prior research has identified factors such as gender, affinity for the subject, job availability, or earning potential which may impact the decision (e.g. Coldwell and Callaghan, 2013; Kim et al., 2002; Leon and Kim, 2016; Mauldin et al., 2000; Pritchard et al., 2004). A study by Malgwi et al. (2005) undertook an enhanced examination of gender differences, but highlighted an additional issue change of major by students. Nearly 50% of the students that participated in their study had changed major within the business school. While they explored the positive and negative factors driving the change of major, there was no exploration of the potential delays in graduation associated with the change.

Other research regarding major choice has focused on personality traits, values, and interpersonal behavior (e.g. Giacomino and Akers, 1998; Noel et al., 2003; Kopanidis and Shaw 2014). Noel et al. (2003) define a personality trait as a “distinguishing, relatively enduring way in which one individual differs from another (Guilford, 1959)” (p.154). The study utilizes personality and self-monitoring indicators with respect to three business majors. The results indicate that “personality stereotyping and related self-monitoring behaviors take place in students’ selection of a business major.” (p.156). Thus, those individual and enduring personality aspects impact choice of major. The authors also note, however, that they did not address causality. There was no examination of precedence of career choice and personality traits.

Literature Review

Yet another research area has explored business degrees with respect to professionalism. This research includes efforts to examine professionalism (e.g. Holland, 2013; Noordegraaf, 2007; Senapaty and Bhuyan, 2014). Among this research, Cabrera and Bowen (2005) argue that global management should be viewed as a profession. To qualify as a profession, they emphasize three criteria: A common body of knowledge which is both theoretically grounded and instrumental for practice, a set of rules for entry to the profession to be able to practice, and a shared code of conduct for the profession to serve a greater good (Cabrera and Bowen, 2005). They go on to explore a particular MBA program and its efforts to advance professionalism. An interesting caveat to their discussion is that “fit with the values of professionalism “should be considered both in the selection of students and in the content of their education” (p.798). This idea is also recognized by Noel et al. (2003) when they state an “effective business program should strive to develop a match between the qualities desired in a profession and the students’ stereotypical images of those professions” (p.156). It is this idea of fit or match, which prompted the current study.

We seek to explore the match between the views of Supply Chain (SC) industry professionals and SC students regarding the characteristics required to be successful in the SC profession. This will allow us to assess whether students’ expectations are in line with the work environment they will encounter. We also included faculty that teach SC courses, to allow a triangulation approach, as demonstrated in Rosenberg et al. (2012). By including faculty, it also allows insight into whether the associated SC programs are emphasizing those characteristics or abilities relevant to the marketplace.

While the “fit” between student and program may be desirable, the choice of major is dictated by the student, not the educational program. While students might seek information regarding a major or field of study from others, the decision is ultimately left to the student. Further, the choice of major typically happens early in the students’ business program. This is consistent with Leon and Uddin (2016) who found “The sophomore year appears to be the most common year for major selection” (p.31). Thus, the choice of major may occur before a primary or introductory course in the discipline is taken. In the authors’ university, some incoming freshmen are accepted as pre-business students, and can declare SCM as a major upon enrollment in the University, even though admission to the College of Business occurs two years later. Given these possibilities, a student’s understanding of the SC field may be somewhat limited at the time the major choice is made.

Methodology

A survey was created and distributed to three different groups of respondents. Supply Chain industry professionals, faculty that teach Supply Chain Management courses, and students currently enrolled in a Supply Chain Management program were surveyed. The survey consisted of just a few questions, which were modified slightly according to the expected respondent. Examples of the questions are provided in Table 1. The first question was the primary focus of the current study. An open-ended approach was utilized, instead of culling potential characteristics of SC professionals from prior research. This was done deliberately, so that respondents could use their own terminology and phrasing, and it allowed respondents to answer briefly or in more depth. This open-ended approach also ensured that respondents were not limited to previously identified characteristics, as supply chains are continually changing and evolving, and management characteristics might also change over time (MacCarthy et al., 2016). The remaining survey questions were used to gather some basic information about the respondents, and the third and fourth questions provided lists where multiple responses could be chosen.

| Table 1 Survey Questions For Supply Chain Industry Professionals |

| Q1: What characteristics or traits do you think are beneficial for Supply Chain Management professionals? Consider a business student with an undeclared major. What abilities would you indicate to the student would support a successful career in SCM? Q2: What is your current job title? Q3: Which areas of the Supply Chain is the primary focus of your current job? Q4: Are you currently a member of any of the following professional organizations? |

Potential survey respondents were contacted via email and given a link to Surveymonkey.com. Participation in the survey was entirely voluntary. Faculty that taught Supply Chain courses at universities within or near west Michigan were identified as potential respondents. This regional approach was taken to align the responses with students and industry professionals in that same region. A total of 10 useable responses were received from faculty, for a response rate of 22.7%. A total of 83 students were queried, in a course required of Supply Chain Management majors. The majority of students in the course were seniors, and many on the verge of graduating. Useable responses were provided by 73 students, for a response rate of 87.9%. For the industry professionals, three professional organizations in West Michigan were asked to contact their members and forward the request for participation. Since the emails were sent by the professional organizations, and not the author, a precise response rate is not ascertainable. There is also the possibility of overlap among the email lists of the three organizations, as members could belong to more than one organization. Consequently, for industry professionals, an estimated response rate of 20.5% was determined. All of these response rates are considered acceptable for empirical research and provide some confidence in the findings.

Results And Discussion

The survey responses were analyzed within their respective groups. The initial analysis utilized Wordle, which is a program that creates word clouds from text. Word clouds allow a display of diverse words or themes, and those words with a greater frequency of occurrence will appear darker, and in a larger size. This approach has been used in other research, especially for preliminary explorations of qualitative issues (e.g. Holland, 2013).

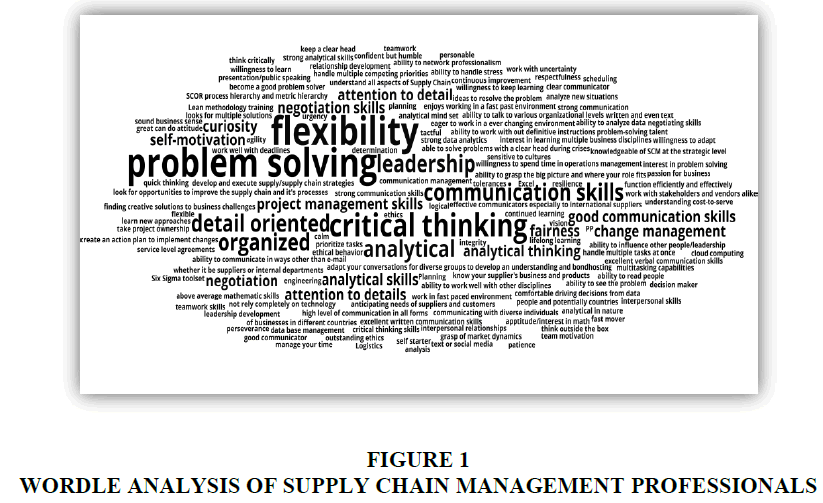

The word cloud created from the responses of SC professionals revealed several common themes (Figure 1). Problem-solving, flexibility, and critical thinking were cited as desirable characteristics for SC managers by numerous survey respondents. To support the relevance of these identified traits, it may be helpful to have some insight into the professionals that responded. Among the job titles provided by the respondents (Question 2 of the survey) were Strategic Purchasing Manager, Senior Materials Planning & Execution Manager, Master Scheduler, Vice President of Supply Chain, and Director of Logistics. These job titles span the supply chain and indicate individuals with substantial experience in the field of Supply Chain Management. Consequently, they should be very knowledgeable about the characteristics associated with success in the field.

The emphasis on critical thinking by SCM professionals is of particular interest, in that a study by Bycio & Allen (2009) found that performance by graduating business students on the California Critical Thinking Skills Test were significantly related to SAT performance. Both SAT-V and SAT-M had correlations greater than 0.60 with the critical thinking assessment. Thus, critical thinking is well developed at the time of taking the SAT. So, sharing the word cloud with incoming freshmen might expose students that self-identify with these characteristics to the idea of SCM as a major much earlier in their academic career.

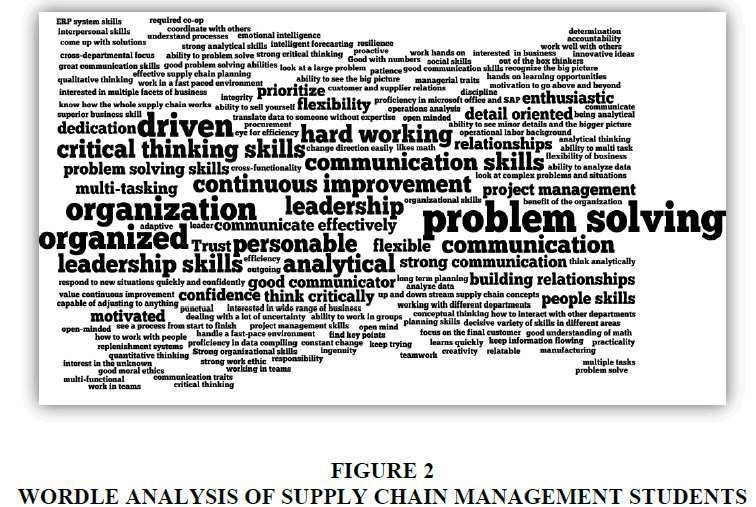

We then turned our attention to the student responses. The resulting word cloud is shown in Figure 2. As can be seen, there were a number of similarities between the student generated word cloud and that of the industry professionals. Students also emphasized problem solving, as well as organization and being driven. To clarify the amount of similarity between the two word clouds, a tally of the most frequently identified characteristics from the two respondent groups was conducted. There is some subjectivity in the counting of each identified characteristic, as it was subject to interpretation of the survey responses. However, both were tallied by the same individual with the hope of greater consistency. Table 2 provides the results. For both groups, communication skills (both written and oral were included) was the most frequently cited characteristic. While there were some differences in the importance placed on some of the characteristics, there is significant similarity (6 out of 8 in common) between the two lists. The students clearly have reasonable expectations regarding their future jobs.

| Table 2 Rankings Of Characteristics Based On Frequency |

||

| Ranking | SCM Professionals | SCM Students |

| 1 | Communication skills | Communication skills |

| 2 | Problem-solving | Problem-solving |

| 3 | Analytical | Hard-working/driven |

| 4 | Flexibility | Personable |

| 5 | Detail-oriented | Flexibility/adaptability |

| 6 | Organized | Analytical |

| 7 | Critical thinking | Organization/organized |

| 8 | Leadership | Leadership skills |

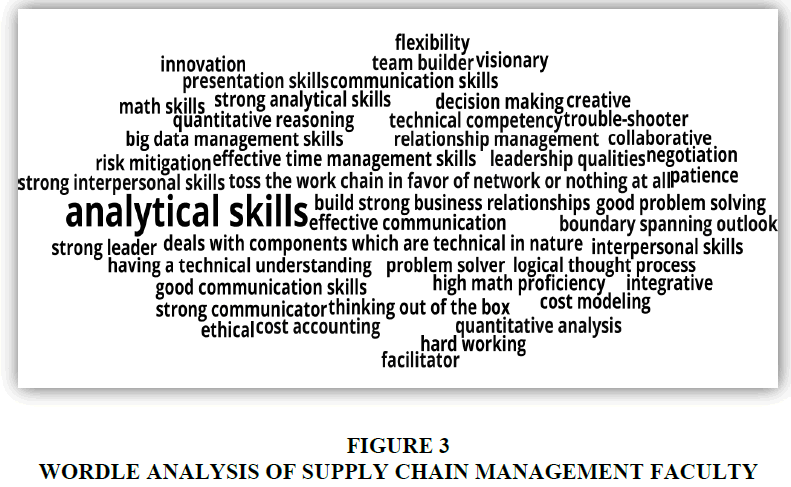

In creating the word cloud based on faculty responses, there were fewer bold words than in the other two. An examination of the individual responses indicated one response that focused on particular topics of study, such as ISO 14000, CAD, Six Sigma, etc. Consequently, this one response was omitted, to see if the remaining nine responses were more consistent with the word clouds created from student responses and industry professional responses. The resulting word cloud for faculty members (n=9) is provided in Figure 3. Again, we see similar emphasis to characteristics identified in the first two word clouds, but the smaller sample size here limits the generalizability.

Conclusion

The word clouds indicate a match between student perceptions of SC management and industry professionals’ expectations. Thus, students appear to have a reasonable understanding of their future working environments and should be a good fit for the field. Both groups ranked communication and problem-solving skills highly, and recognized the need for leadership, analytical abilities, and flexibility. While the importance of these attributes for business graduates have been identified (e.g. Stuba et al., 2017; Curkovic and Fernandez, 2016) this study is specific to SC majors. And while the faculty word cloud indicates their emphasis on similar abilities to those of the other two groups, the smaller sample size somewhat limits the generalizability of those findings.

These findings should also prove useful for recruiting potential SC majors. While the findings are consistent with other studies regarding SCM skills (e.g. Jordan and Bak, 2016), the word clouds provide a visual, easily accessible look at the field of SCM. They highlight the abilities and expectations required of professionals in the field and may help limit mismatches between students and the choice of major. This may, in turn, increase student satisfaction with a major or educational program. Further, choice of a major that aligns with student expectations may minimize change of major and thus prevent delays in time to graduation. Further, in programs with limited faculty resources, it may ensure that the best potential candidates are utilizing those limited resources.

A similar approach could also be used for other business majors. The short survey takes very little time, and could be shortened to just the first question. After collecting survey responses from appropriate professionals or employer recruiters, word clouds for other majors could be created. This could potentially allow better matching between students and choice of major across the entire business school.

Finally, this approach could be used to support assessment or even accreditation. The question could be altered to ask students what skills were emphasized in their major, or within the broader business program. Similarly, employers could be asked about skills business graduates possess or skills needed. This would allow an examination of the similarity or alignment between the two sets of responses. The shortness of the survey would allow frequent, and easy, assessment. Frequent assessments over time may also highlight any needed curricular updates or modifications as the business environment changes.

References

- Blumberg, Y. (2017). 50% of millennials would give up this fundamental American right to have their student loans forgiven. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/2017/09/29/millennials-would-give-up-this-right-to-wipe-out-their-student-loans.html

- Browne, C. (2018). Stay on the fast track to graduation and minimize student loan debt. Retrieved from https://www.credible.com/blog/student-loans/save-college-minimize-student-loan-debt/

- Cabrera, A., & Bowen, D. (2005). Professionalizing global management for the twenty-first century. Journal of Management Development, 24(9), 791-806.

- Coldwell, D.A.L., & Callaghan, C.W. (2013). The role of internal and external factors on management students’ subject choices. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences (SAJEMS NS), 16(3), 244-257.

- Curkovic, S., & Fernandez, N. (2016). Closing the gap in undergraduate supply chain education through live experiential learning. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 6(6), 697-708.

- Farrington, R. (2017). 3 ways to minimize your college debt. Retrieved form https://thecollegeinvestor.com/20953/3-ways-minimize-college-debt/

- Godfrey, N. (2017). Student loan debt is the gift that keeps giving. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/nealegodfrey/2017/12/19/student-loan-debt/#992c9f3459b0

- Hinton, R., & Rezin, A. (2018). A generation buried in student debt. Retrieved from https://chicago.suntimes.com/feature/a-generation-of-college-students-buried-in-debt/

- Holland, L. (2013). Student reflections on the value of a professionalism module. Journal of noInformation, Communication and Ethics in Society, 11(1), 19-30.

- Jordan, C., & Bak, O. (2016). The growing scale and scope of the supply chain: a reflection on supply chain graduate skills. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 21(5), 610-626.

- Kopanidis, F.Z., & Shaw, M.J. (2014). Courses and careers: Measuring how students; personal values matter. Education+Training, 56(5), 397-413.

- Leon, S., & Uddin, N. (2016). Finding supply chain talent: An outreach strategy. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 21(1), 20-44.

- MacCarthy, B.L., Blome, C., Olhager, J., Srai J.S., & Zhao, X. (2016). Supply chain evolution theory, concepts and science. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 36(2), 1696-1718.

- Malgwi, C.A., Howe, M.A., & Burnaby, P.A. (2005). Influences on students’ choice of college major. Journal of Education for Business, 80(5), 275-282.

- McInerney, C.R., DiDonato, N.C., Giagnacova, R., & O’Donnell, A.M. (2006). Students’ choice of information technology majors and careers: A qualitative study. Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal, 24(2), 105-115.

- Noel, M.N., Michaels, C., & M.G. Levas. (2003). The relationship of personality traits and self-monitoring behavior to choice of business major. Journal of Education for Business, 78(3), 153-157.

- Noordegraaf, M., (2007). From “pure” to “hybrid” professionalism present-day professionalism in ambiguous public domains. Administration & Society, 39(6), 761-785.

- Rosenberg, S., Heimler, R. & Morote, E.S. (2012). Basic employability skills: A triangular design approach. Education+Training, 54(1), 7-20.

- Scipioni, J. (2017). 50% of millennials would give up their right to vote to get student loans erased. https://www.foxbusiness.com/features/50-of-millennials-would-give-up-their-right-to-vote-to-get-student-loans-erased21/18

- Selingo, J. (2018). Where student loan debt is a real problem. The Washington post. Retrieved form https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/grade-point/wp/2018/01/05/where-student-loan-debt-is-a-real-problem/?utm_term=.81008a54fead

- Senapaty, S., & Bhuyan, N. (2014). Evaluating the profession and professionalism of business managers: Control embedded in character. Decision, 41(3), 271-278.

- Stuba, E., Curkovic, S., & Wagner, B. (2017). The benefits of simulated coursework in western michigan university’s undergraduate supply chain program. Creative Education, 8, 1821-1832.