Research Article: 2022 Vol: 21 Issue: 1

Do the Contingencies Matter to Crisis Management? An Analysis of Thai Companies

Daranee Pamornrattanakul, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi

Patipan Sae-Lim, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi

Vorapoch Angkasith, King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi

Citation Information: Pamornrattanakul, D., Sae-Lim, P., & Angkasith, V. (2021). Do the contingencies matter to crisis management? An analysis of thai companies. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 21(1), 1-13.

Abstract

Mixed-methods research was employed to study the determinants of crisis management in Thai companies. Both quantitative and qualitative data were gathered during the global spread of the pandemic crisis of COVID-19. The theoretical framework was constructed with crisis management protocols, contingencies, and previous articles. A total of 15 experts were involved in semi-structured interviews. Thematic analysis (TA) was posited as a qualitative data analysis method for identifying the important themes of effective crisis management. According to the quantitative analysis under the regression, logistics regression and discriminant analysis models, culture and leadership are both significantly correlated with the maturity of crisis management. Firms with different sizes and types lead to different approaches to the management of crises. TA proposed three themes related to the effectiveness of crisis management in the results.

Keywords

Crisis Management, Contingency Theory, Maturity of Crisis Management.

Introduction

With the complexity and volatility of the environment, the crises confronted by firms and management have become more frequent and severe. The business lockdowns, social distancing, and even school closures announced on March 26, 2020 (United Nations Thailand, 2020) due to the spread of Coronavirus COVID-19 have tested the readiness of crisis protocols.

Historically, crises were rare risks that were considered to have low likelihood but very high impacts (Pearson & Clair, 1998), for example, the events of September 11, 2001, the SARS and H1N1 pandemic outbreaks in 2003 and 2009, respectively, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami that affected Thailand and several other countries, Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the 2010 Iceland volcanic eruption and its ash cloud over Europe, or the 2011 Tohoku earthquake in eastern Japan, and so on (Baubion, 2013). In contrast, today the chance of a crisis occurrence seems frequent; therefore, current crises are regarded simply as a normal situation that leads to negative or undesirable outcomes for firms. Crises have been defined by many authors in different ways, but there is no common and shared definition (De Wolf, 2013; Weick, 1993). Currently, at the time that the researchers conducted this research, COVID-19 has also heavily impacted Thailand’s society in the third wave.

In any crisis events, both physical and psychological loss still exists. At the country level in the short term, COVID-19 has negative impacts involving poverty that results from job loss, job suspension, and income reduction. Yet, any crises also include long-term negative impacts, especially those involving psychological turmoil (Thapa & Pathranarakul, 2019).

At the company level, Krungsri Research (2020) argued that 143,414 out of 473,324 companies in Thailand (30.3%) would experience tight liquidity, while 132,980 companies (28.1%) were at liquidity risk due to the COVID-19 situation. On the contrary, only 32.6% or 154,318 companies are financial resilient. To this conclusive view, COVID-19 has a negative impact mostly on small size firms. Furthermore, 33.2% of formal workers have experienced a pay cut or loss. Due to these huge effects of crises, systemic crisis management should be put in place.

While crises protocols are ready for large organizations, the small companies posit them on an ad hoc basis in Thai industries. Organizational theories thus proposed the hypothesis as “Do any influential factors correlate with the effectiveness of crisis management?” In addition, organizational theorists have attempted to explain the complexity of organizational phenomena with several organizational theories and concepts; unfortunately, the crises school of thought lacks the theories and empirical rigor which result from case studies or anecdotal evidence (James et al., 2011; Sellnow & Seeger, 2013). Although the studies of crisis are performed across various fields of study, such as strategic management, organizational behavior, mass communication as well as public relations, concrete holistic concepts are still neglected.

According to organization theory, academia most often mentions chaos theory while framing crisis work. Moreover, there are several organization theories: contingency, resource dependence, institutional, and population ecology theory, which could be contributed to the pre- and post-crisis explanations and mitigations but were never mentioned in previous studies. Moreover, most of the previous research concluded the largest determinant as accounting for “leadership” (Pathranarakul & Sae-Lim, 2018; Sae-Lim, 2019; Wisittigars & Siengthai, 2019).

Consequently, this research then further analyzed other influential factors. We believe that leadership and leverage culture are both prioritized but would like to consider if any other contingencies also have importance. With the adoption of a mixed research methodology, the reasons that such determinants are important can also be examined through qualitative study. Qualitative analysis will also propose the effective crisis management protocol in the results.

Ultimately, the contributions are two-fold. First and foremost, the practical contribution of this study will assist organizations to set the systematic crisis management during crises. Secondly, the convergence between organizational theories and the crises school of thought persists as a theoretical contribution.

Literature Review

The Definitions of Risk and Crises

Crises are a particular type of risk that is located in the red zone of the corporate risk heat map (Pinvanichkul & Sae-Lim, 2021; Pathranarakul & Sae-Lim, 2018). Most of the crises are high impact, yet they posit a low likelihood.

Definitions of crises are multifaceted terms as well as their typology. Saka (2014) stated seven types of crises: natural disaster, technological crisis, confrontation, malevolence, organizational misdeeds, workplace violence and rumors, while crisis typology could be consolidated as the internal and external crises. Most of the theorists attempt to determine crises at an organizational level; however, COVID-19 persists as a global crisis.

Yet, the typology and definitions of crises do not truly matter; nevertheless, effectively managing them is still a challenge due to the limitation of crisis knowledge in firms, the need for a high level of stakeholder engagement, and the new forms of crises. Equally important, previous research studies were fragmented and difficult for scholars and practitioners to further understand the literature’s core conclusions (Bundy et al., 2017).

Crisis Management Protocols

Practically and theoretically, effective crisis management includes three phases: pre-crisis, during-crisis and post-crisis (De Wolf, 2013; Pathranarakul & Sae-Lim, 2018; Pinvanichkul & Sae-Lim, 2021). Instead of implementing a constant crisis management plan, practical firms can generate crisis management protocols with the following details.

1. Pre-crisis: This phase could be determined as “planned for or prevented” (Racherla & Hu, 2019). Nevertheless, with the currently turbulent environment, organizations cannot easily plan for any crises in advance. The types and forms of crises change from time to time. Racherla & Hu (2019) thus proposed that firms should formulate their policies and procedures in this phase. To promote a good pre-crisis protocol, crisis management governance such as a “crisis management committee/team” facilitates a good direction of effective crisis management.

2. During-crisis: When crises spread through firms, safety is a priority. Thus, all stakeholders should survive. Pathranarakul & Sae-Lim (2018) mentioned that the high maturity energy firms in Thailand proposed sub plans in this phase, such as emergency response, incident management combined with crisis communication, business continuity and recovery.

3. Post-crisis: After crises have been mitigated, firms should return to the normal stage. Both physical and psychological loss is evaluated. Feedback from the lessons learned is included to enhance the crisis management protocols.

Organization Theories Related to Crises

Organization theorists have attempted to explain organizational phenomena by applying several theories. One of the most well-known open systems accounts for “contingency”, where a phenomenon in an organization depends on the internal and external context (Scott, 1987; Galbraith, 1973). To be more precise, one successful factor in one firm would not ensure the successfulness of other firms.

Donaldson (2001) and Ginsberg & Venkatraman (1985) concluded that “no theory or method can be applied in all instances.” To put it simply, under contingency theory, there is no one best way to manage firms due to both the internal and external factors. Common factors can be size and type, which the authors have examined.

Apart from contingency, explaining the rationale of crises most often adopts chaos theory. Under chaos theory, the phenomena of firms are non-linear, unpredictable, and dynamic as well as having random aspects (Seeger, 2002). However, chaos characters account for instability and change, which are both appropriate to explain the crisis cycle of pre-, during- and post-crisis.

Determinants of Crisis Management

Our independent variables were the determinants of crisis management. The dependent variable measured the maturity of effective crisis management.

The most mentioned determinant of crisis management is the “leader factor”. Leadership includes the vital determinants for crisis and risk management in terms of improving organizational performance (Sae-Lim, 2019). Wisittigars & Siengthai (2019) conducted the Delphi technique for searching for leader competencies during crises focused on facility management systems in Thailand. Their research found that “emergency preparedness and crisis communication are both prioritized.” Moreover, modern articles support transformational leadership for handling crises (Alkhawlani et al., 2019). Sae-Lim (2019) found the significant association between leadership and agile competencies during the crises. Furthermore, his research also revealed a high correlation between communication and crisis management.

Therefore, the second determinant accounts for “communication”. Crisis communication is indispensable during crises. Both external and internal stakeholders should receive the equal unique information during and post-crisis. Coombs (2015) stated that best practice of crisis communication takes its role as reputation repair. This research also indicated that strong crisis communication responsibility accounting for “instructing and adjusting information apology, compensation, or both” could protect a firm’s reputation by reducing anger, anxiety, and the likelihood of negative word-of-mouth.

Moreover, crisis communication should be a tactical strategy that is designed to improve the situation for stakeholders. We could also learn from the failure involving the unsystematic crisis communication related to the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. Tony Hayward, BP’s former CEO, made a mistake while communicating during the crisis. He mentioned empathy as well as the effect on the environment by the BP oil spill as the key, yet he also made a complaint to reporters that he wanted his life back (Pathranarakul & Sae-Lim, 2018).

Ultimately, as mentioned, leadership is the most mentioned in crises determinants. However, a leader also drives organizational culture. The last determinant the author included accounted for culture, which is difficult to measure, but in fact, it determines action and decision making consolidated from collective action through individuals. Leverage culture encapsulated with agile leaders could make it possible to achieve high levels of crisis management (Bhaduri, 2019). Thus, the last influential factor the author included in the empirical model was culture.

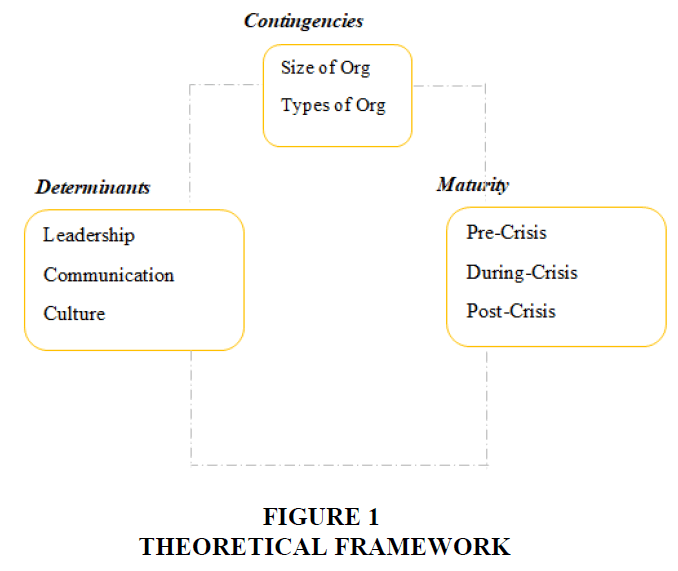

Proposed Theoretical Framework for Quantitative Analysis

According to the review of the literature above, under the section of quantitative analysis, the authors proposed the theoretical framework as the following.

In this paper, there are two main research questions: 1) “What are the largest determinants for the effectiveness of crisis management?”, and 2) “Why and how do particular organizations perform better during a crisis?” However, the sub-research question is “How many maturity levels of crisis management are there in Thai industry?.”

For the above research questions, a mixed method approach is appropriate for answering them. The data used in this study in the quantitative part was collected via Thai companies, while for the qualitative study, the researchers inquired with various types of organizations, which posit a high maturity level of crisis management.

A survey was involved in the quantitative part, as Babbie (2006) argued that a survey is considered a good tool for gathering the generalizations of social science research. All questionnaire items were constructed from the above conceptual framework. The Index of Item-Objective Congruence (IOC) through content validity was performed by three experts. The survey questionnaire is composed of four parts: contingency characteristics, determinants, crisis management cycle and other suggestions. The sampling frames were randomly selected with an unknown number of population (Koronis & Ponis, 2018) (Figure 1).

Both the descriptive and inferential statistics were used in the quantitative parts. Cluster analysis, which involves sorting “groups, individuals or objects into clusters” (Hair et al., 2010), was adopted to cluster the maturity levels of crisis management. Cluster analysis was initially screened as the statistical tools are suitable.

Most importantly, to answer the main research question, “What are the largest determinants for effective crisis management?” the authors significantly confirmed the hypothesis based on three types of inferential statistics for parameter estimations. These three statistical models for inferential causality analysis are: 1) ordinary least squares (regression analysis), 2) maximum likelihood (logistics regression), and 3) canonical discriminant functions (discriminant analysis). The last two models are based on the categorization of the dependent variable; however, in the first one, the dependent variable is posited as continuous.

The mixed methodology in this study was utilized with two stages: 1) preliminary qualitative inputs to the core quantitative research processes and 2) follow-up qualitative extensions to the core quantitative research processes (David, 2014). The first stage of the qualitative approach initially started as a document analysis from previous studies to gather the determinants for constructing the items in the questionnaire. To explore further beyond the quantitative analysis, qualitative analysis through semi-structured interviews was implemented for answering the why and how questions by 15 executive interviewees who work in high levels of maturity of crisis management in various types of firms. The qualitative findings were processed by thematic analysis (TA) to search for common themes for the interview script (Creswell, 2014).

TA is a method for “identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data” as described by Braun & Clarke (2006: 79). They also presented the six steps of conducting TA: becoming familiar with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming of the themes, and producing the report.

Quantitative Analysis Results

Organizational characters

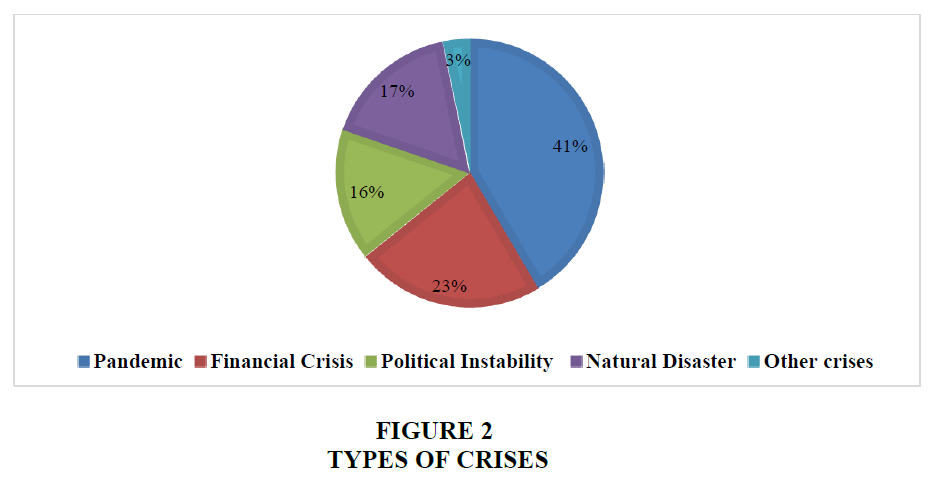

The unit of analysis in this study accounts for the “organizational level”, and thus, the respondents’ characters (gender, education, etc.) could be neglected. Although the organizational respondents amounted to more than 500, only 400 organizations that were confronted with crises were selected. Most of them were impacted by the pandemic resulting from the COVID-19 virus (Figure 2).

According to contingency theory, the size and type of an organization are both important. Size is defined by the number of permanent employees: 0 - 500 (small), 501 - 1,000 (medium) and above (large), respectively. In Tables 1 and 2, most of the respondents were from private and large organizations.

| Table 1 Size of Organizations | ||

| Size of Organization | Amount | Percentage |

| Small | 146 | 36.50% |

| Medium | 51 | 12.75% |

| Large | 203 | 50.75% |

| Total | 400 | 100.00% |

| Table 2 Types of Organization | ||

| Types of Organization | Amount | Percentage |

| Private | 360 | 90.00% |

| Public | 19 | 4.75% |

| State enterprise | 13 | 3.25% |

| Non-profit | 3 | 0.75% |

| Others | 5 | 1.25% |

| Total | 400 | 100.00% |

Maturity Level of Crisis Management

Effectiveness of crisis management could be determined by the readiness and preparation for the pre-, during- and post-crisis. In this empirical study, there are two clusters of the dependent variable, in which 58% of the respondents are defined as “high maturity of crisis management”, where the cycle of crisis management is routinely embedded as a pre-, and during- and post-crisis approach. The rest of the respondents are defined as “medium maturity of crisis management” (Table 3).

| Table 3 Maturity of Crisis Management | |||

| Cluster | Definition | Amount | Percent |

| 1 | Pre-crisis: Determine crisis governance, having tested the plan, dynamically adjust crisis protocol. During crisis: Very active in the emergency phase, good crisis communication as well as continuity and recovery of key business. Post-crisis: Evaluation of loss, improvement of protocols from feedback. |

232 | 58.00% |

| 2 | The same as Cluster 1, but not fully embedded. | 168 | 42.00% |

| Total | 400 | 100.00% | |

Before sophisticated statistical analysis was performed, testing of data assumptions was required. The sample size of 400 was five times the number of independent variables (Hair et al., 2010). There were no concerns of multicollinearity of the independent variables (VIF<10). Ultimately, both the dependent and independent variables are a symmetry in which skewness and kurtosis were mainly in the range of -2 to 2, or within the acceptable limits for normality testing (Trochim, 2006). This confirmed the symmetrical as well as normal distribution.

To confirm the contingency theory, in Table 4 and 5, the hypothesis that the significant distinction of size, types of organization, leadership style, communication and culture could lead to the different maturity of crisis management is accepted. Hence, the organizational context is a considerable matter.

| Table 4 Test of Inferential Assumptions | |||

| Variables | Skewness | Kurtosis | VIF |

| Leadership | -1.1 | 2.3 | 1.89 |

| Communication | -0.84 | 0.53 | 1.91 |

| Culture | -0.98 | 1.11 | 1.93 |

| Maturity of Crisis Management | -0.92 | -1.17 | |

Most importantly, the empirical results compared with the three proposed models: regression, logistics and discriminant analysis, were all the same patterns. To put it simply, leadership and culture were significantly associated with the maturity level of crisis management, while the communication factor seems insignificant. Finally, the largest determinant based on the primary data was culture (Table 6).

| Table 5 Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) | ||

| Independent Variables | F | Sig. |

| Size of Organization | 10.57 | 0 |

| Types of Organization | 3.78 | 0.005 |

| Leadership | 13.79 | 0 |

| Communication | 17.01 | 0 |

| Culture | 24.71 | 0 |

Qualitative Analysis Results

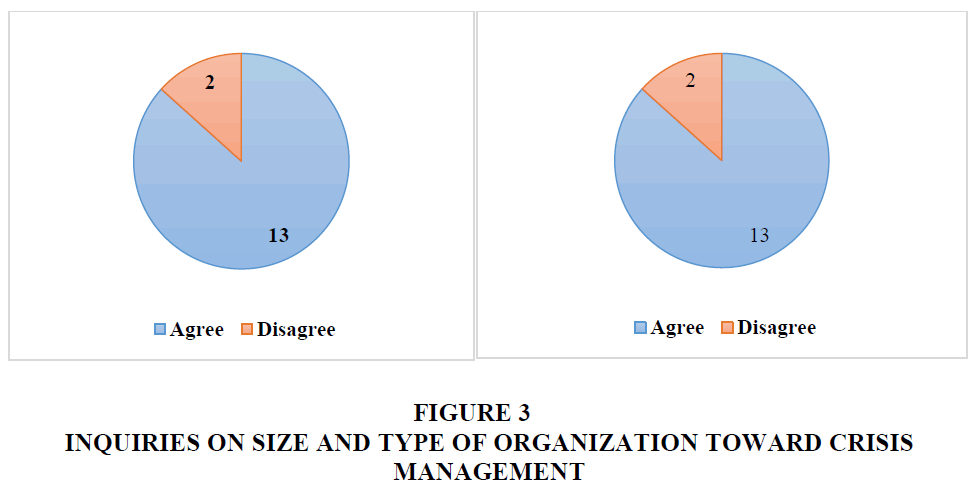

Qualitative data from 15 experts was included in this research. With the mixed methods approach, we tried to summarize both the integrated and divergent views. There are two collaborative roles of qualitative data, which are affirming quantitative results and exploring “why questions” (Figure 3).

Proportions of Expert views towards Size & Types of Organization

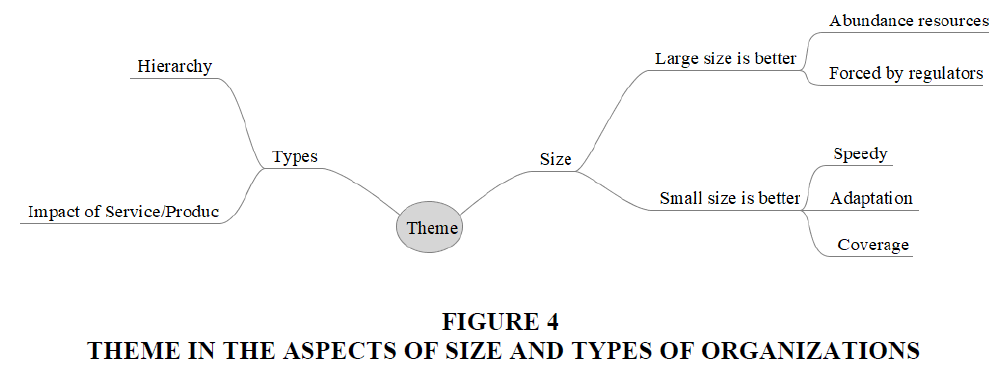

We started with investigating the affirmation between the quantitative results given size, type and maturity of crisis management. As seen in the quantitative results given in Table 5, size and types of organization both mattered as 13 out of 15 experts agreed that size and types lead to the different levels of maturity of crisis management. However, the minority qualitative data should also be included (Figure 4).

| Table 6 Comparison of the Determinant Analysis Model | |||

| Independent Variables | OLS | Maximum Likelihood | Canonical Discriminant Functions |

| Leadership | -0.08* | 0.942** | 0.563** |

| Communication | -0.7 | -0.452 | |

| Culture | -0.204** | -1.902** | 1.189** |

“One expert said that both size and types do not matter during crises, yet the effectiveness of crisis management relies on organizational structure.”

“Two experts pointed out that the effectiveness of crisis management depends on leadership style.”

Most importantly, expert views agreed on quantitative results in which “the difference between size and types lead to the maturity of crisis management.” Size is a significant matter. Some experts said that a large size of firm is better in terms of the crisis budget capacity. To be more precise, large firms mean that there are abundance resources to invest in crisis consultant expertise compared to those of small firms. This reason confirms the resource dependence theory (Robins et al., 2002). Another finding about the advantages of large firms affirms the institutional theory in which an “institution’s environment can strongly influence the effective crisis management” (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). To illustrate, one expert said that large organizations may be forced by regulators such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to put in place crisis protocols.

On the contrary, a small size of firms is also advantageous for many reasons. Quick decisions, good adaptability and coverage communication are the main benefits of small organizations.

Evidently, the types of firms are influential to effective crisis management. Experts stated that private organizations better mitigate crises due to having a flat structure compared to a public one. Moreover, hierarchy is associated with decision making. To illustrate, public organizations where the structure seems to be hierarchical are inertial and quite slow with decision making. To the expert views, effectiveness of crisis management depends on what types of product or service they deliver. Obviously, if particular firms deliver highly impactful services and products, they will have a high-level maturity of crisis management, for example, hospitals, airlines, banks, and so on.

Leadership Competencies Under Crisis Situations

Most of the articles point out the direct effect of leadership competencies and crisis management. Two out of 15 experts said that “the same leader who has a particular competency to cope with crises in firm A will not ensure the effectiveness to act in firm B.” In their view, culture and understanding organizational context are still important, which affirmed the quantitative results and the research question.

Moreover, half of the interviewees confirmed the appropriateness between agile competencies and maturity of crisis management and thus affirmed Sae-Lim (2019). With the different levels of agile leadership, there are two levels according to expert views: the achiever and catalyst levels. For the former, leaders should determine clear goals and mission as well as vision and need to routinely assess the external environment. For the latter, the approach is the same as the achiever leader, yet catalyst leaders are also skilled at team building and people strategies. Two experts stated that “leadership in turbulence should focus on staff psychology.”

Surprisingly, some interviewees defined interesting functional leader competencies, which are innovative and change agent leaders that are also associated with effective crisis management.

Organizational Culture to Cope with Crises

All interviewees summarized that collaborative and teamwork culture could overcome crises. Also, open-mindedness and trust are vital in organizations during crises. Moreover, a half of the experts said that suitable culture to handle crises should be cultivated from individuals who are aware of risk. Precisely, risk culture leads firms to survive during the crises.

Meanwhile, although communication is not correlated with maturity of crisis management in the quantitative mode, it is indeed important to some expert views. They mentioned that two-way communications provide better enhanced crisis protocol.

This research investigated which factors determine the maturity of crisis management, and additionally why and how particular firms are able to successfully handle crises. Mixed methodology was applied to resolve the research questions. Several articles together with organizational theories as well as crisis management practices were incorporated into the conceptual framework and qualitative questionnaire.

All of the data assumptions were verified before estimating the parameters in the quantitative analysis. Advanced statistical models through ANOVA, regression, logistics regression and discriminant analysis were employed as the parameter settings. According to the empirical data, contingencies are significant. Different sizes and types of firms lead to the different maturity of crisis management levels. Moreover, leadership and culture are associated with the effectiveness of crisis management given the three types of parameter estimation models.

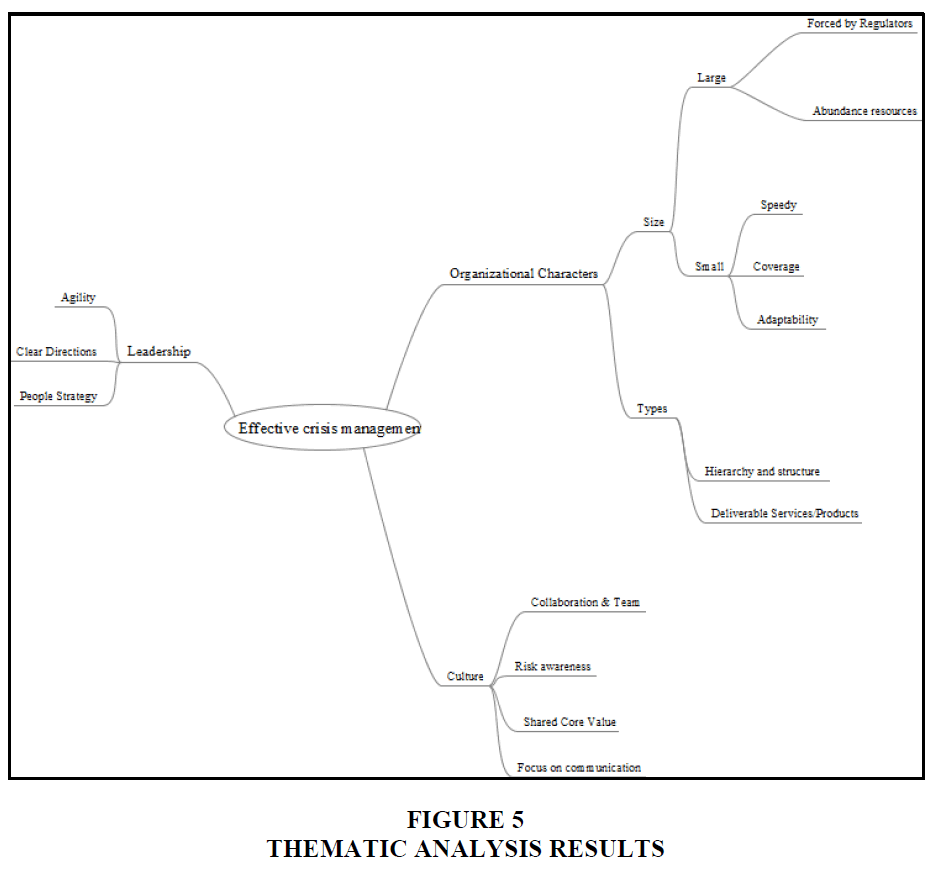

Most importantly, the semi-structured interviews with 15 experts who are now responding directly to crises in well-known firms were included as qualitative data. Thematic analysis (TA) was used to process the qualitative data. Three converging themes were found: culture, leader and organizational characters as the following (Figure 5).

Conclusion and Implications

According to the TA, it was found that those three themes are interdependent. For example, culture has an effect on leaders and vice versa. Firms that cultivate team and risk culture, shared core values and focus on communication can easily cope with crises. Such firm characters may create appropriate leaders who are ready for crises or agile, clear direction leaders who can also create such mentioned culture in which a survival model is created during a turbulent environment.

Moreover, apart from contingency theory, maturity of crisis management could be explained from resource dependency and institutional theory. Thus, the different types and size of firms lead to significantly different levels of effectiveness of crisis management.

This article contributes both practical and theoretical aspects. Regarding the former, it posits the blueprint for firms to develop crisis protocols. For the latter, the authors explain crisis phenomena based on three organizational theories.

What the authors have learnt is that mixed-method research will respond to social science research questions well. Although communication factors were found to insignificantly correlate to crisis management in the three statistical models, some of the experts emphasize that effective communication is essential.

Importantly, culture determines the maturity of crisis management; however, culture is difficult to alter. Firms then need to recruit or develop potential leaders who are sufficiently competent to cope with crises and modify culture instead. Obviously, the empirical data has shown that agile leaders are a key in turbulent environments. One interesting result indicated that future leaders should focus on people and psychology. Additionally, leaders acting as change agents and innovators will be beneficial to the 21st century.

In terms of the internal management, organizational structure is associated with managing crises. Flexibility and flat structures can allow communication to flow speedily. Management teams can thus insert this finding during organizational arrangements.

Ultimately, this research explains crisis phenomena given three organizational theories: contingencies, resources dependency and institutional. Future research studies may add other theories to frame the concepts. Also, the empirical results fit well with Thai companies where crisis management practices are new and novel. Therefore, it is recommended that future research be conducted to test the model in other countries and regions.

References

Babbie, E.R. (2006). SPSS practice WB the practice of social research. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Baubion, C. (2013). OECD risk management: strategic crisis management.

Creswell, J.W. (2014). Research design. Washington DC: SAGE Publications, Inc.

David, M.L. (2014). Integrating qualitative and quantitative methods a pragmatic approach.

De Wolf, D. (2013). Crisis management: lessons learnt from bp deep-water horizon spill Oil. Business Management and Strategy, 4(1), 69-90.

Donaldson, L. (2001). The contingency theory of organizations. Sage.

Galbraith, J. (1973). Designing complex organizations. Reading, Mass.

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E., & Tatham, R. (2006). Multivariate data analysis. Uppersaddle River.

Krungsri Research. (2020). COVID-19 crisis: The impact on businesses and choice of policy tools. Retrieved from https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/research-intelligence/ri-covid19-crisis-en

Pinvanichkul, T., & Sae-Lim, P. (2021). Materializing sustainability and business resiliency. Prentice Hall.

Robins, J.A., Tallman, S., & Fladmoe‐Lindquist, K. (2002). Autonomy and dependence of international cooperative ventures: An exploration of the strategic performance of US ventures in Mexico. Strategic Management Journal, 23(10), 881-901.

Sae-Lim, P. (2019). Enterprise risk management (ERM) as strategic tool for organizational performance: Empirical study in Thai listed companies. Journal of Public and Private Management, 26(2), 89-89.

Saka, R.O. (2014). Crisis management strategy and its effects on organizational performance of multinational corporations in Nigeria: Empirical evidence from Promassidor Ltd. European Journal of Business and Management, 6(23), 79-86.

Scott, W.R. (1987). Organizations: Rational, natural, and open systems. Prentice hall.

Seeger, M.W. (2002). Chaos and crisis: Propositions for a general theory of crisis communication. Public Relations Review, 28(4), 329-337.

Sellnow, T.L., & Seeger, M.W. (2013). Theorizing crisis communication. Malden, MA: Wiley

Trochim, W.M. (2006). The research methods knowledge base. 2nd. Edition. Internet WWW page.