Research Article: 2020 Vol: 23 Issue: 1S

DO NON-OIL EXPORTS FACILITATE ECONOMIC GROWTH IN SAUDI ARABIA?

Mohammed A. Aljebrin, Majmaah University

Citation Information: Aljebrin, M. A. (2020). Do non-oil exports facilitate economic growth in Saudi Arabia? Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 23(S1), 450-476.

Abstract

For decades, both developed and developing countries have adopted export-led growth strategies to achieve economic growth, based on the export-led growth hypothesis (ELGH). The ELGH purports that there is a positive long-run relationship between exports and economic growth, and related research from Asia and Africa has yielded mixed results. However, limited studies have been conducted in the Middle East.

Using the ELGH as a framework, this study evaluated the contribution of non-oil exports to economic growth in Saudi Arabia since the implementation of development plans for facilitating growth in non-oil exports. Time series data from 1990 to 2017 for GDP, labor, capital, and non-oil exports were analyzed using the augmented Dickey-Fuller procedure followed by the Johansen cointegration method with a vector error correction model to determine the long- and short-run relationships among these variables. The analysis confirmed a significant positive relationship between GDP and non-oil exports as well as between capital and GDP in both the long and short run, indicating at least unidirectional causality. However, there was no significant relationship between labor and growth.

The results confirmed the significant contribution of non-oil exports to economic growth in Saudi Arabia, providing support for the ELGH. Combined with other research, the findings suggest that Saudi Arabia should diversify its exports, simplify its export procedures, develop new infrastructure and capital to support the production of exports and domestic use, and facilitate collaborative relationships among oil and non-oil sectors. Given that the ELGH argues that the export sector generates growth by increasing aggregate levels of labor and capital, addressing issues related to labor must also be considered. This study contributes valuable, context-specific information to planners, decision makers, and practitioners that can be used to facilitate the implementation of effective policies for achieving a balanced, sustainable economy in Saudi Arabia.

Keywords

Capital, Economic Growth; Export-Led Growth Hypothesis; Labor; Non-Oil Export; Saudi Arabia.

JEL Classification

F11, F14, F41, F43

Introduction

Since the mid-1970’s, increasing technology, economic shocks, and globalization have led both developed and developing countries to shift from import-substitution strategies to export-led growth strategies as a means of achieving economic growth via increased industrialization, and during the past several decades, researchers have examined economic growth from the perspective of the export-led growth hypothesis (ELGH). The export-led growth hypothesis purports that there is a positive long-run relationship between exports and economic growth, arguing that the primary factor in economic growth is that of increased export activity. Numerous studies have examined this dynamic in both developed and developing countries, with mixed results. However, a positive long-run relationship has been demonstrated in both developed and developing countries, notably, Germany, Japan, and East Asia, and the ELGH has become widely influential in both research and economic policy in many countries (Shirazi & Manap, 2005; Alkhateeb et al., 2016; Malhotra & Kumari, 2016; Aljebrin, 2017; Faisal et al., 2017; Priyankara, 2018). However, research in developing countries has focused on countries in Asia and Africa, whereas limited studies have been conducted in the Middle East.

During this period, shifts away from primarily agricultural activities to industrial production, as well as global shifts from heavy industry to services, have created significant challenges to developing countries that have historically been dependent on the export of nonrenewable natural resources. The non-natural resource sector plays a major role in achieving balanced, long-term economic growth in most natural-resource-rich countries, especially during the postresource period. Developing this sector can increase domestic demand for goods and services, and increased demand can result in the promotion of exports, in turn, increasing the volume of foreign exchange reserves in the country and thus promoting economic development. Therefore, it is critical to establish an understanding of the association between the development of the non-natural resource sector and economic policies in order to develop appropriate growth policies (Alkhateeb et al., 2016; Hasanov et al., 2018; Priyankara, 2018).

The Saudi Arabian economy is dependent on oil revenues and faces continuous changes in oil prices, and the risk of depending on one resource is alarming, especially in the case of natural resources. These resources diminish over time, and prices that are related to such resources in the world market are dependent on both political and economic variables. Therefore, the Saudi Arabian government needs to diversify its income sources.

In light of these challenges, substantial efforts have been directed at developing the non-oil export sector in Saudi Arabia, with particular focus on the industrial sector (Alhowaish, 2014; Alsakran, 2014). During the development of consecutive 5-year plans (1970-1995), planners in Saudi Arabia focused on economic diversification to increase production in non-oil sectors such as manufacturing, non-oil minerals, and agriculture, thus decreasing its dependency on oil exports.

Since then, a limited number of studies have confirmed that increased export activity and oil exports are positively related to increases in GDP in Saudi Arabia (Alhowaish, 2014; Faisal et al., 2017; Sultan & Haque, 2018), supporting the ELGH. However, to the researcher’s knowledge, no current study has specifically assessed the contribution of the non-oil sector to GDP in KSA since the implementation of specific plans to increase non-oil export activity. Moreover, although numerous studies have investigated the ELGH with respect to total and non-oil export activities in developing countries in Asia and Africa, few studies have focused on evaluating the contribution of non-oil exports in countries in the Middle East. Therefore, additional research that focuses on the status and development of non-oil exports in Middle Eastern countries is needed.

Using the export-led growth hypothesis as a framework, the purpose of this study was to conduct an empirical evaluation of the contribution of increases in non-oil exports to economic growth in Saudi Arabia during 1990-2017, thus providing an evaluation of a previously tested theory in a new context (Salamzadeh, 2020) and information that can be used to inform decision makers in Saudi Arabia with respect to economic policy and resource allocation. To determine the real influence of non-oil exports on economic growth, the relationships among GDP, non-oil exports, labor, and capital stock were evaluated by using time series data that were obtained from the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA, 2019) and the World Bank development indicator. The relative influence of these variables on GDP and the long-run and short-run relationships among the variables were analyzed by using the Johansen cointegration method with a vector error correction model as the main econometric tools.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. A brief introduction to the ELGH is followed by a review of relevant studies from Africa and the Middle East. Next, a detailed description of the economic context and current research related to exports and economic growth in Saudi Arabia is presented. Then, a description of the model and the econometric methods that were used is presented, followed by the empirical results of the study. The paper concludes with a discussion of the results, implications, limitations, and suggested future research, followed by a summary of the main conclusions of the study.

Background And Literature Review

The ELGH has origins in neoclassical economic theory and was widely adopted during the 1980’s as economic growth strategies shifted from a focus on import substitution to an emphasis on export as international trade became a predominant force in economic growth and import-substitution strategies in many countries achieved limited success. That exports have a positive effect on GDP growth is a fundamental assumption of the ELGH, and the main argument is that the export sector generates growth by increasing the aggregate levels of labor and capital (Krueger, 1980; Tyler, 1981; Feder, 1982; Shan & Sun, 1998; Alhowaish, 2014; Ee, 2016; Priyankara, 2018). Moreover, proponents of export-led growth strategies argue that export is an essential element of growth in both developing and developed countries, as export activities play a major role in increasing economies of scale, relaxing barriers to foreign exchange, and making foreign markets reachable (Aljebrin, 2017; Faisal et al., 2017; Priyankara, 2018). For example, export supplies the state budget with foreign currency and earnings, which can be taken into consideration with respect to improving the infrastructure and making the investment climate attractive. Export activities are also responsible for increasing the output of organizations or companies and reducing the costs of production, which increase productivity such that economies of scale can be achieved. In addition, export activities expand the local market’s size and increase competition, which helps the economy increase production and adopt new technologies (Mohsen, 2015; Malhotra & Kumari, 2016).

A preponderance of research has investigated export-led growth strategies, and the ELGH has received substantial support in both developed and developing countries, indicating the importance of export activities to economic growth. However, results have been inconsistent. To date, there is no clear consensus in the research community regarding the consistency and directional relationships that are associated with export-led growth strategies, so ongoing research is needed to establish the relevance and usefulness of the ELGH, especially in developing countries.

Most research on export-led growth strategies in developing countries has been conducted in Asia and Africa, and some research has been conducted in the Middle East. Studies that have been conducted in Nigeria, Syria, and Iran are most relevant to this study because they are similar to Saudi Arabia in that they, too, depend heavily on oil exports. A brief review of empirical research in these areas is discussed next, followed by a detailed description of the Saudi Arabian economic context and recent research relating exports to economic growth in Saudi Arabia.

Nigeria is overreliant on oil exports, making its economy fragile to external shocks, and numerous studies have investigated the contributions of both overall export activity and non-oil export activity to economic growth in this country. An analysis by Aladejare and Saidi (2014) suggested that Nigeria is in dire need of economic diversification due to the impact of the current global economic crisis on their economy. Mohsen (2015) found a statistically significant positive relationship between non-oil exports and both GDP and economic development in Nigeria, supporting the value of growth in this sector.

In an earlier study, Adebile and Amusan (2011) used content analysis to study the contribution of Nigerian non-oil-sector exports to GDP as well the share that was provided by cocoa exportation. The analysis revealed vast opportunities and benefits that were available in the non-oil-exports sector. The findings demonstrated that investing in cocoa production increased the GDP and created employment opportunities. The results of the study indicated that involvement in the non-oil export sector played a major role in generating economic growth and sustaining development.

In a later study, Onodugo et al. (2013) implemented an augmented production function that used the endogenous growth model to measure the specific contribution of non-oil exports to economic growth in Nigeria during 1981-2012. The results demonstrated that non-oil exports had little influence on the rate of change in the level of economic growth. In contrast, Usman (2010) used multilinear regression to identify the elements of non-oil exports and their linear relationships with GDP during 1989-2008, finding that non-oil exports significantly contributed to economic growth in Nigeria. In addition, Abogan et al. (2014) examined the influence of non-oil exports on Nigerian economic growth from 1980 to 2010, finding that non-oil exports played a moderating role in economic growth.

Exploring a different dynamic, Olayiwola and Okodua (2013) specifically examined the relationship between foreign direct investment (FDI) and the performance of non-oil exports in Nigeria based on the export-led growth hypothesis. The oil sector of the economy in this country absorbs most of the inflow from FDI, and FDI stakeholders’ interest in efficiency-seeking shows that foreign capital seeks the advantages of cost-efficient production conditions. The researchers completed a causality analysis to test the applicability of the export-led growth hypothesis and applied variance decomposition and an impulse response analysis to explore the dynamic interaction among FDI, non-oil exports, and economic growth. The results did not support the export-led growth hypothesis in Nigeria and indicated a unidirectional causal relationship from FDI to non-oil exports. Economic growth, FDI, and non-oil exports did not show immediate responses in the desired direction to economic shocks in Nigeria, showing a 7-year lag. The authors concluded that fostering non-oil export is an important factor in developing effective FDI in Nigeria.

In a study similar to the present research, Igwe et al. (2015) examined economic growth as a function of non-oil export, capital, and labor, using the ELGH as a framework. Johansen cointegration with a vector error correction model indicated both long- and short-run relationships between non-oil export and economic growth. However, a Granger causality analysis determined that there was no causal relationship between non-oil export and growth. However, there was unidirectional causality moving from capital stock to economic growth and from economic growth to labor.

Several more recent studies have been conducted in Nigeria. Adofu (2016) found a unidirectional association between non-oil exports and degree of economic openness as well as real GDP. Furthermore, their study showed that exchange rates, FDIs, and government expenditures are positively and significantly related to bank credit to the private sector. Kromtit et al. (2017) examined the contribution of non-oil exports to economic growth in Nigeria from 1985 to 2015. The augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) procedure was used to test for a unit root and stationarity of the variables, followed by an autoregressive distributed lag model to determine the relationship between non-oil exports and GDP. Bounds testing indicated cointegration, supporting a long-run relationship among the variables. The regression results revealed a significant positive relationship between GDP and non-oil exports. The exchange rate had a negative but nonsignificant relationship with GDP, which was expected according to economic theory. The authors advocated creating legislation that facilitates participation in non-oil sectors by both local and foreign investors, providing lower interest rates to non-oil sectors, and direct government participation in developing selected non-oil sectors including agriculture, manufacturing, and solid minerals.

Covering a longer period, Bolaji et al. (2018) used time series data from 1975 to 2013 to examine the influence of non-oil exports on GDP in Nigeria. A unit root test followed by cointegration and a vector error correction model was used to determine both short- and long- run estimates. The results indicated that non-oil exports have a unidirectional positive influence on economic growth in Nigeria, suggesting that policies that facilitate the export of non-oil commodities will directly increase growth in the output of non-oil sectors, thereby, supporting the export-led growth hypothesis. The results also showed that capital and labor have a direct significant effect on economic output growth, indicating the importance of the labor force and investment as sources of economic growth.

In contrast, Olayungbo and Olayemi (2018) found a negative effect of government spending on the GDP of Nigeria in the short run and the long run, as well as negative shocks of non-oil revenue on economic growth. Together, these studies suggest that the role of non-oil export on economic growth in Nigeria is not yet firmly established, but there is substantial evidence for a positive relationship.

Germane to the present study, studies in the Middle East have also investigated the contributions of oil and non-oil exports to economic growth. Mohsen (2015) investigated the role of non-oil exports in the Syrian economy during 1975-2010. The researchers used the ADF unit root test procedure, followed by a Johansen cointegration test, Granger causality test, impulse response functions, and a variance decomposition analysis. The results indicated a significant positive relationship between GDP, oil exports, and non-oil exports, with bidirectional short-run causality. Bidirectional long-run causality was established between non-oil exports and GDP, and the results indicated unidirectional causality moving from oil exports to GDP. Oil exports had the most significant influence on GDP, and the authors encouraged promoting non-oil export activity to increase economic diversity in Syria.

In Iran, Tabari and Nasrollahi (2010) investigated the influence on economic growth of oil and non-oil exports across 27 years. These researchers used an extended neoclassical production function with a vector error correction model to measure the short- and long-run relationships.

Their key findings were a negative association between oil-export output and non-oil export output, whereas capital and labor demonstrated a positive relationship with non-export GDP. Mehrabadi et al. (2012) also investigated the influence of oil and non-oil export on the development of Iran’s economy during 1973-2007. This study showed a positive influence of non-oil and oil exports on economic growth.

In a more recent study, Hosseini and Tang (2014) used multivariate cointegration and Granger causality methods to determine the role of oil and non-oil exports in economic growth in Iran from 1970 to 2008, using capital, labor, non-oil exports, oil exports, and total imports as inputs and GDP as the output. The results revealed that non-oil exports, labor, and capital had a positive effect on economic growth, but oil exports and imports demonstrated a negative relationship. Granger causality tests indicated unidirectional causality from both oil and non-oil exports to increases in GDP, supporting the ELGH in Iran. The authors recommended creating policies to promote non-oil exports to offset the negative influence of oil exports on economic growth, as well as generating new capital and investing in infrastructure to support production processes for both exports and domestic needs.

In a more recent study, Varahrami (2015) explored the effects of high oil exports on non-oil exports in Iran as a result of the country’s interest in reducing its oil dependency. Using data from 1973 to 2013, the Johansen cointegration procedure with an error correction model were used to determine the short- and long-run relationships. The results indicated that high levels of income from oil exports were not positively related to increases in non-oil exports in either the long run or the short run. Based on the results, the authors advocated allocating income from oil exports to investments in industrial machinery that could be used in both the agricultural and industrial sections, which, in turn, was expected to increase overall national production, consequently increasing non-oil exports. Finally, on a more general level, Khayati (2019) showed that exports and economic growth are significantly interlinked in Bahrain. Furthermore, their results suggest that exports are positively related to GDP in both the short and long run.

Overall, the current research in Nigeria, Syria, and Iran indicates that increased export activity supports economic growth, supporting the ELGH. However, this is not so in every case and the results for directional causality vary substantially. Most of the studies that have specifically examined the influence of non-oil exports on economic growth have confirmed long-run relationships, and many have also shown short-run relationships. However, many developing countries have experienced context-related challenges that have limited the effectiveness of export-led growth strategies (Abogan et al., 2014). The importance of the political and economic structure of a country is an important consideration in any research that attempts to provide valid information for guiding policies. Therefore, the current context of Saudi Arabia is important to consider in interpreting the results of this study.

The Saudi Arabian Context and Export-Led Growth

Economic diversification has been of significant interest to the Saudi Arabian government for the past several decades because of the country’s primary economic dependence on oil exports. During their efforts to support growth in non-oil export activities, Saudi Arabian planners found that the workforce shortage and absorptive capacity were the main challenges to implementing this industrialization strategy. Therefore, they chose an extensively focused formula for growth in the non-oil sector by planning to make a considerable investment in some of the main industries and dedicating a small proportion of the labor force accordingly. Saudi Arabia also has a large number of minerals besides oil and gas. These minerals naturally develop due to the bounteous amount of iron core, gold, copper, phosphates, silver, bauxite, uranium, coal, lead, tungsten, and sink in this region. These minerals have been neglected in the past because oil was dominant, but recently the Saudi Arabian government has become more interested in collaborating with the private sector to develop businesses to exploit these mineral resources.

Because they possess a large amount of capital as well as generous energy supply and feedstock, the economic growth plans in Saudi Arabia concentrate on two heavy process industries: basic metals and petrochemicals. Relatedly, throughout the sixth development plan, the mining and quarrying sectors were predicted to grow at an average rate of 9% annually, depending primarily on the development of the construction sector (Cappelen & Choudhury, 2017).

As a result of continuous structural and regulatory reforms and ongoing government expenditure on development projects, there is continuous economic growth in Saudi Arabia. These changes have helped in achieving sustainable economic growth by increasing the contribution of non-oil sectors to the GDP and diversifying the production base. With the growth of exports in the non-oil sector, the economic reforms agenda of Saudi Arabia started achieving positive outcomes for both the state and with respect to employment rates. There was an improvement in economic outcomes in 2018, as the GDP increased by 2.2% after decreasing in 2017, real oil GDP rose by 2.8%, while growth in the non-oil GDP rose by 2.1% (Khan, 2019). In turn, international credit rating agencies have maintained Saudi Arabia’s sovereign credit rating as its economy strengthens (Aljebrin, 2017). With that said, it is known that revenues from exports of nonrenewable natural resources can negatively affect the economic growth of a country (Hosseini & Tang, 2014; Olayungbo & Olayemi, 2018). Inducing demand for imports potentially weakens the competitiveness of the nonresource tradable sector by increasing revenues from the export of natural resources that appreciate the real exchange rate. This intensifies the need to search for ways to balance the export of nonrenewable resources with corresponding growth in the export of renewable natural resources and other products and services.

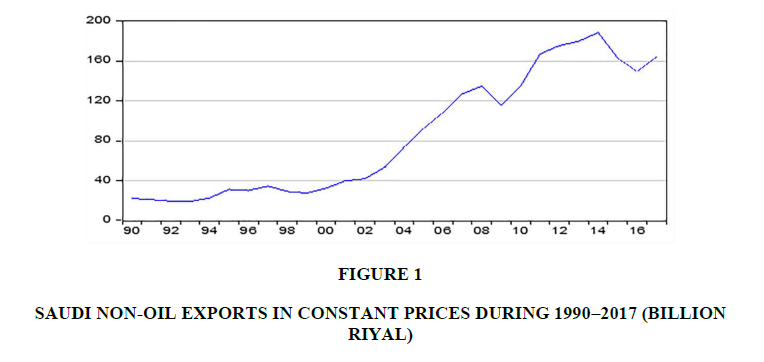

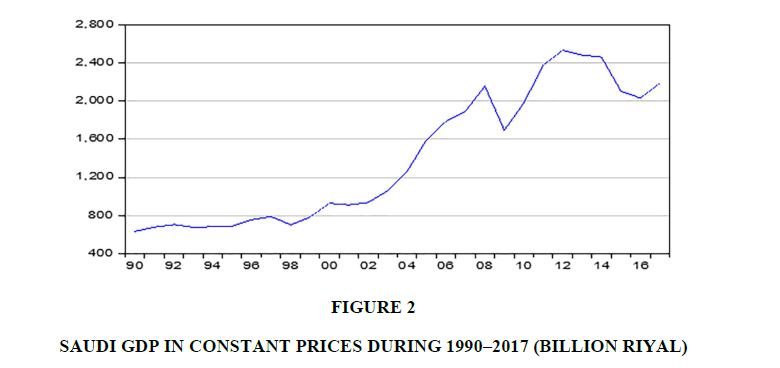

The dynamics of non-oil exports and economic growth in Saudi Arabia confirm an existing relationship, which could be positive or negative (Figures 1 and 2). Table 1 shows that non-oil exports increased relatively smoothly from 1990 to 2017, during which they increased from 9.3% of total exports in 1990 to 23.3% in 2017 (See Table A1 for oil, non-oil, and total exports in 2010 constant prices). However, the major obstacle for Saudi Arabia is its low share of total exports, which is comparatively lower than that in other developing oil-exporting countries. In this case, the role of policy makers becomes important in emphasizing the need for economic diversification and searching for new and competitive goods and services.

| Table 1: Overall Exports In Current Prices (1990–2017) | |||||

| Period | Non-oil exports (Billion riyal) |

Oil exports (Billion riyal) |

Total exports (Billion riyal) |

% of Total exports * | |

| Non-oil exports | Oil exports | ||||

| 1990 | 22.18 | 216.25 | 238.42 | 9.3 | 90.7 |

| 2000 | 32.35 | 346.52 | 378.86 | 8.6 | 91.4 |

| 2010 | 134.61 | 807.18 | 941.79 | 14.3 | 85.7 |

| 2011 | 166.85 | 1,125.48 | 1,292.33 | 12.9 | 87.1 |

| 2012 | 175.41 | 1,162.55 | 1,337.97 | 13.1 | 86.9 |

| 2013 | 179.66 | 1,071.23 | 1,250.89 | 14.4 | 85.6 |

| 2014 | 188.38 | 926.23 | 1,114.61 | 16.9 | 83.1 |

| 2015 | 162.84 | 491.71 | 654.55 | 24.9 | 75.1 |

| 2016 | 149.31 | 429.14 | 578.45 | 25.8 | 74.2 |

| 2017 | 163.94 | 540.94 | 704.88 | 23.3 | 76.7 |

*Calculated by the author (Source: SAMA, 2019)

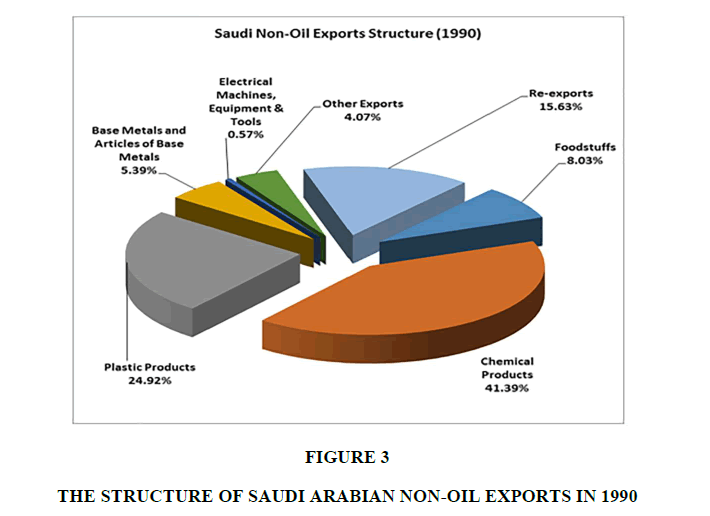

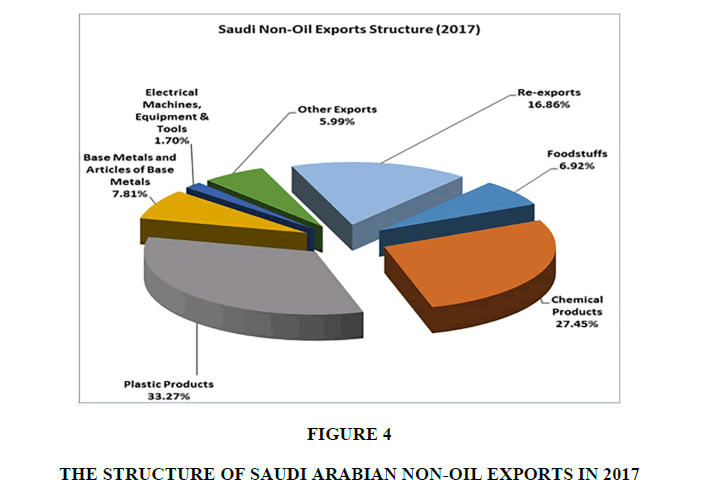

It is also critical to consider the structure of non-oil exports when examining the performance of Saudi Arabian non-oil exports. Table 2 indicates the structure of non-oil exports in 1990 and 2017, indicating the average growth rate of the components of non-oil exports during this period and shares of total exports. Chemical and plastic products comprise over half of the total exports, at 27.45% and 33.27%, respectively.

| Table 2: Overall Non-Oil Exports In Billion Riyal (1990–2017) | |||||

| Non-oil exports | Value (billion riyal) |

Yearly average growth rate * (%) | % of Non-oil exports * | ||

| 1990 | 2017 | 1990–2017 | 1990 | 2017 | |

| Foodstuffs | 1.280 | 11.972 | 8.83 | 5.16 | 7.29 |

| Chemical products | 5.156 | 45.876 | 9.16 | 35.95 | 25.54 |

| Plastic products | 2.567 | 53.638 | 10.60 | 27.92 | 33.62 |

| Base metals and articles of base metals | 1.132 | 17.997 | 10.07 | 6.69 | 7.18 |

| Electrical machines, equipment and tools | 0.103 | 3.026 | 8.42 | 2.59 | 1.07 |

| Other exports | 0.429 | 15.294 | 8.18 | 6.79 | 6.19 |

| Re-exports | 2.144 | 29.743 | 9.19 | 14.06 | 15.68 |

| Total | 12.811 | 177.546 | 74.22 | 99.16 | 96.57 |

*Calculated by the author (Source: SAMA, 2019).

The highest average annual growth rate during this period was obtained by electrical machines, base metals, and plastic products (Figures 3 and 4). Re-exports have achieved a high average growth rate during the same period, which enabled them to increase to 16.86% of total exports in 2017.

The Saudi Export Development Authority declared a rise in non-oil exports, which facilitates access to Saudi products by the world market. The authority stated that they were working on six key strategic goals, which included improvement in the efficiency of the export environment as well as increasing knowledge of export practice and export readiness. They also stated that they were working on facilitating the creation of export opportunities, making Saudi products more available, and improving the linkage between exporters and potential importers. The value of Saudi non-oil exports reached an extraordinary level in 2018. An SAR120 million ($32 million) motivational program was launched as part of the stimulus plan for the private sector. This stimulus package provides support to Saudi firms so that their capacities and capabilities can be increased for entry and expansion into the international markets, thus increasing the competitiveness of their products. This program also motivates companies to increase their efforts in export markets because there are nine WTO-compliant incentives that are available to help to cover expenses that are incurred by Saudi Arabian companies for their export activities. These incentives help Saudi companies to increase their global reach. This program also allows funding for activities that are related to export capacity development such as training that is required for staff to meet professional qualifications and the cost of promotional activities and other specialized training (SEDA, 2019).

Several studies have examined the contribution of export activities to economic growth and the ELGH in Saudi Arabia. Alhowaish (2014) used cointegration and error correction modeling to evaluate the relationships between exports and imports and economic growth in Saudi Arabia during the period from 1968 to 2011. The results of this study indicated that real GDP, real exports, and real imports are cointegrated and that there are long-term relationships among these variables in Saudi Arabia. The vector error correction model revealed that both GDP and exports have bidirectional causality in the long run, and the short-run analysis indicated unidirectional causality moving from export growth to GDP. The overall findings of this study suggest that growth in export activities positively affects GDP in the Saudi economy.

Similarly, Alkhateeb et al. (2016) examined the relationship between growth in export activities and GDP in Saudi Arabia to determine the applicability of the ELGH to the Saudi Arabian context. To examine the relationship between exports and economic growth, GDP, exports, imports, foreign direct investment, and real exchange rate were included in an extended functional model. The ADF procedure was used to establish first-order integration of the dependent variable and that the explanatory variables had a mixed order of zero and one. The following cointegration procedures and causality tests indicated a feedback effect in both the short run and long run, suggesting that increases in GDP have led to increases in exports but exports have also contributed to economic growth in Saudi Arabia. In this study, real exchange rate, imports, and FDI were also significantly related to economic growth and exports, with causality implied. Therefore, the authors suggested that these variables also facilitate export activity and economic growth in Saudi Arabia.

In another recent study, Faisal et al. (2017) investigated the validity of the ELGH in Saudi Arabia using time series data from 1968 to 2014. The researchers used an autoregressive distributed-lag bounds-testing approach to investigate the relationship between economic growth, imports, and export. The resulting estimates indicated that imports, exports, and GDP are strongly cointegrated in Saudi Arabia and that exports have a positive influence on economic growth in the long run. Specifically, with a 1% increase in exports GDP was increased by 3.39%, implying the validity of export-led growth hypothesis. Furthermore, the results of a Granger causality test suggested unidirectional causality from export to GDP, suggesting the validity of ELGH. Faisal et al. (2017) suggested that because Saudi Arabia exports mainly oil, which creates economic vulnerability to external shocks, the country needs to invest more in the non-oil sector and diversify their investment by attracting more FDI. This will facilitate economic growth and adaptability in response to external shocks.

Sultan and Haque (2019) applied the Johansen cointegration method to establish a long-run relationship between economic growth and oil exports, imports, and government consumption expenditure. This study confirmed that economic growth has a positive long run relationship between GDP and oil exports, as well as government consumption expenditure. Moreover, oil exports were shown to positively and significantly influence GDP in both the short run and the long run. Additional results revealed a negative long-run relationship between imports and economic growth in Saudi Arabia. Based on these findings, Sultan and Haque (2019) advocated regulating imports and making extensive efforts to diversify the economic base.

Regarding non-oil exports in Saudi Arabia, Alsakran (2014) provided a detailed evaluation of non-oil export financing. This work examined the obstacles that Saudi exporters face by conducting a survey in 175 manufacturing firms. The current study examined the export behavior of the firms in their trade operations, access to finance, credit constraints, competition, and the business environment. The results of the econometric analysis revealed that many factors were significantly and positively related to export intensity-a proxy for the performance of a firm-whereas it was also revealed that new firms are more credit-controlled than are older firms. The main results suggested that firm performance is boosted by growth in exports.

Overall, the results regarding growth in exports and economic growth in Saudi Arabia are strongly positive. However, studies are limited, and more details are needed regarding the specific influence of growth in non-oil exports. Given the growth in both GDP and non-oil exports over the past several decades (Figures 1 and 2), it is critical to verify the nature of the relationship empirically in order to develop appropriate policy and other government responses that are needed to support ongoing economic diversification in Saudi Arabia.

Justification/Contribution

In summary, numerous studies have been conducted to examine the influence of growth in export activities on the economic growth of both developed and developing economies, and the ELGH has been supported in many cases, as confirmed by established long-run and short-run relationships. However, studies that have examined the relationship between increased export activity and economic growth that have been conducted in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East have demonstrated mixed results, indicating the importance of political and economic contexts to the successful implementation of any growth strategy. Recent studies have tested the ELGH in several developing countries in Asia and Africa (Shirazi & Abdul, 2005; Nasreen, 2011; Abogan et al., 2014; Malhotra & Kumari, 2016; Tolulope & Olalekan, 2017; Chawala, 2019; Ibrahim & Abdalla, 2020), mostly obtaining support for the model. However, little is known about the influence of non-oil exports on economic growth in Middle Eastern countries, including Saudi Arabia.

Although increased export activity has been associated with economic growth in Saudi Arabia, most studies have examined the issue at an aggregate level, a concern raised by Priyankara (2018). This lack of evidence warrants an examination of the specific influence of non-oil export activity on economic growth in Saudi Arabia. Such an examination will provide needed information to researchers, policy makers, and other stakeholders that are involved with the ongoing modification and implementation of actions that are intended to support achieving balanced economic diversification in Saudi Arabia and countries that share a similar context.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to conduct an empirical evaluation of the contribution of increases in non-oil exports to economic growth in Saudi Arabia during 1990-2017 from the perspective of the ELGH, thus testing the model in a new context and providing valuable information to decision makers in Saudi Arabia with respect to economic policy and resource allocation. Time series data that were obtained from SAMA (2019) and the World Bank were analyzed by using the ADF procedure to complete unit root tests, establishing stationarity among the variables and the order of integration. The Johansen cointegration method with a vector error correction model was then used to determine the long- and short-run relationships among non-oil exports, labor, and capital stock to gain further insight into how non-oil exports function to facilitate economic growth in Saudi Arabia.

Data And Econometric Methods

The data for GDP, labor, and capital that were used in this study were obtained from SAMA (2019) and the World Bank Development Indicator. All of the variables were log transformed to avoid the problem of heteroscedasticity and to obtain estimates of elasticity.

The targeted economic properties of the models that were used in this study were achieved for all of the statistical tests by ensuring homoscedastic and normal distributions, correct functional forms, and uncorrelated model residuals. Therefore, the results are valid for reliable interpretation based on their normal, homoscedastic, and uncorrelated distributions (Tables A2–A5).

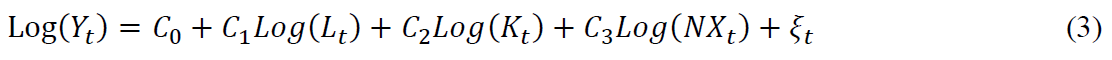

Based on the ELGH, non-oil exports were expected to demonstrate a positive relationship with GDP as a proxy for economic growth. Traditional neoclassical growth models (Solow, 1975) assume that output (Y) depends on both capital (K) and Labor (L). Thus the traditional production function is stated as follows:

Therefore, to specify the role of non-oil exports in economic growth, the present study investigated the relationships among non-oil exports, capital, and labor as inputs and the growth of the Saudi Arabian economy (GDP) from 1990 to 2017, so the value of non-oil exports was added to the above equation to expand on the traditional neoclassical production function. Thus, non-oil export (NX) is incorporated into equation 1, which becomes

For the purposes of this study, the influence of non-oil export on economic growth in Saudi Arabia during this period was estimated by using ordinary least squares (OLS). The representation of OLS in connection with our variables is as follows:

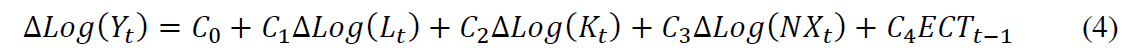

However, to avoid spurious regression results from the OLS procedure, we first used the ADF test for the individual series to determine whether the variables were stationary and integrated of the same order. The Akaike information criterion was used to select the lag parameter in the ADF procedure to eliminate the residual serial correlation (Akaike, 1973). Afterwards, the Johansen cointegration method (Johansen and Julesius, 1992) and a vector error correction model were used to estimate the long-run and short-run relationships among the variables. A negative and significant lagged error correction term indicates a long-run causal relationship (Sultan and Haque, 2018).

The Johansen and Julesius (1992) maximum-likelihood approach to cointegration ensures the integration of the vector autoregressive model for all endogenous variables. This coefficient represents the formation of a long-run equilibrium, and the coefficient of the error correction term (ECT) explains the presence of a short-run relationship. A negative sign with a significant ECT coefficient confirms the existence of a long-run relationship, whereas the joint significance of first-differenced coefficients captures the short run causal effect of the variables (Banerjee et al., 1998; Sultan & Haque, 2018).

Cointegration can be equivalently represented with respect to the OLS framework if it exists among the four variables, and the Engle-Granger two-step estimation technique is an appropriate technique for estimating the degree of cointegration. The long-run relationship is adjusted in OLS procedure in the first step, and the resulting residuals are used for testing the cointegration hypothesis. According to Engle and Granger (1987), an error correction model is needed if the cointegration is established. Thus, the short-run dynamics are represented through the development of an error correction model as follows:

Empirical Results

The ADF analysis revealed that the null hypotheses for all of the variables were accepted for all levels but rejected at the first difference, which demonstrated that the series were stationary with an integration of the first order (Table 3).

| Table 3: ADF Unit Root Test For Level And First Difference | ||

| Variable | Order | ADF |

| Log (Y) | Level | -1.015876 |

| First diff. | -3.246785a | |

| Log (L) | Level | 1.471935 |

| First diff. | -2.043866b | |

| Log (K) | Level | -1.228072 |

| First diff. | -4.008431a | |

| Log (NX) | Level | -0.384725 |

| First diff. | -2.036735b | |

Note. ADF: Dickey–Fuller (1979) unit root test with the Ho: Variables are I(1). The letters a and b indicate significance at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively.

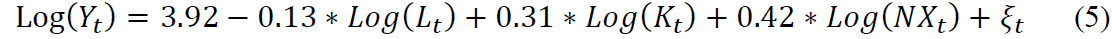

The cointegration analysis indicated long-run or equilibrial relationships among nonstationary variables, and the variables were associated with the cointegrating vector. The OLS model was as follows (Table A6):

The ADF test for residuals indicated the integration of residuals at a 5% significance level, which confirmed the presence of both cointegration and an ECT (Table 4).

| Table 4: ADF Unit Root Test For Residual | |

| Variable | Level |

| ECT | -4.165427a |

aIndicates significance at the 1% level.

The maximum eigenvalue and reflection of the stochastic matrix are based on the outcomes of the likelihood-ratio test (Tables 5 and 6, respectively). These two tests confirmed the presence of two cointegrating vectors (CV’s), confirming the long-run relationship. This means that variables move together and do not drift arbitrarily over time, and the distance between them will be stationary.

| Table 5: Trace Of The Stochastic Matrix | ||||

| Hypothesized No. CV(s) | Eigenvalue | Trace statistic | 0.05 Critical value | Prob.** |

| No* | 0.781417 | 74.25002 | 49.58316 | 0.0000 |

| At level 1* | 0.519300 | 31.67355 | 31.97007 | 0.0300 |

| At level 2 | 0.320865 | 11.16324 | 19.94174 | 0.2017 |

| At level 3 | 0.011683 | 0.329046 | 4.148664 | 0.5662 |

Note. The trace test indicated two cointegrating equations at the 0.05 level. * p < 0.05.

** MacKinnon et al. (1999) p-values.

| Table 6: Co-integration Test Based On Maximal Eigenvalue Of The Stochastic Matrix | ||||

| Hypothesized No. CV(s) | Eigenvalue | Max-Eigen statistic | 0.05 Critical value | Prob.** |

| No* | 0.781417 | 42.57647 | 30.48543 | 0.0003 |

| At level 1 | 0.519300 | 20.51031 | 23.33126 | 0.0609 |

| At level 2 | 0.320865 | 10.83419 | 17.46206 | 0.1627 |

| At level 3 | 0.011683 | 0.329046 | 4.148656 | 0.5662 |

Note. The max-eigenvalue test indicates 1 cointegrating equation at the 0.05 level. * p < 0.05.

** MacKinnon et al. (1999) p-values.

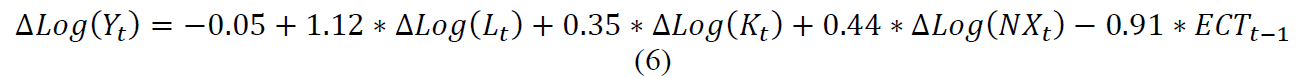

The three independent variables (K, L, and NX), then, can be comparatively considered for the short-run OLS framework due to their serial integration. The short-run dynamics were represented by the following model (see Table A7):

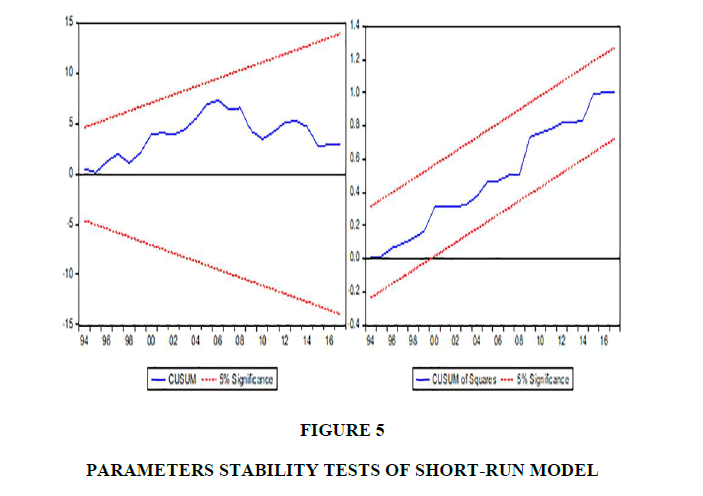

The short-run dynamics reflect the stabilization of the long-run coefficient. The stability of the parameters was examined using the cumulative sum test for parameter stability of squares (CUSUMSQ) and CUSUM (Brown et al. 1975; see equation 4). The CUSUM and CUSUMSQ plots confirmed the absence of instability in the coefficients in that the estimates fell with the 95% confidence interval lines (Figure 5).

The results of the short-run analysis revealed a significant and negative effect, with a magnitude of -0.91, showing a rapid adjustment process of 91% towards equilibrium and 1% away from equilibrium in the first year. The empirical findings of both the short- and long-run OLS estimates are summarized in Table 7, indicating that non-oil exports and labor are positively related to GDP, with at least unidirectional causality. Labor exerted a minimal influence, failing to reach significance.

| Table 7: Ordinary Least Square Estimates (1990–2017) | ||

| Variable | Coefficient | |

| Long run | Short run | |

| C | 3.92a | 0.05c - |

| Log (L) | -0.13 | 1.12 |

| Log (K) | 0.31a | 0.35a |

| Log (NX) | 0.42a | 0.44a |

| ECT (-1) | - | -0.91a |

Note. The letters a and c denote significance at the 1% and 10% levels, respectively.

The positive significant relationship between non-oil exports and economic growth in both the short run and the long run provides support for the ELGH in Saudi Arabia with respect to non-oil exports. There is also a significant positive relationship between capital and economic growth in both the short and long run, which is generally expected according to economic theory. Therefore, at least unidirectional causality is indicated for non-oil exports and capital. However, labor was not significantly associated with economic growth in either the short run or long run.

In summary, after establishing the appropriate econometric properties of the data, the Johansen cointegration analysis with the vector error correction model revealed a significant positive relationship between both non-oil exports and capital, with at least unidirectional causality. The association with labor was nonsignificant. The short-run indicated a significant negative effect (-0.91), showing a rapid adjustment process of 91% towards equilibrium and 1% away from equilibrium in the first year. These results provide support for the ELGH and the value of the policies and plans that have been established in Saudi Arabia to promote growth in non-oil sectors. The results are discussed in light of the study context and existing research in the next section.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to provide an empirical evaluation of the contribution of non-oil exports to economic growth in Saudi Arabia since the implementation of consecutive development plans that have been directed at increasing diversity in the economic base by facilitating growth in non-oil exports. The influence of non-oil exports on the GDP of Saudi Arabia from 1990 to 2017 was evaluated within the framework of the ELGH. Specifically, time series data for GDP, labor, capital, and non-oil exports for the period that were obtained from SAMA (2019) and the World Bank were analyzed by using the ADF procedure, standard Johansen cointegration, and a vector error correction model. The analysis confirmed a positive significant relationship between economic growth and non-oil exports as well as between capital and economic growth in both the short and long run, indicating at least unidirectional causality. However, there was no significant relationship between labor and growth, in contrast with the findings of Bolaji et al. (2018) and Tabari and Nasrollahi (2010). These findings concur with those of Igwe et al. (2015) with respect to non-oil exports and capital, but, again, no effect for labor emerged in the current study.

Kromtit et al. (2017) also found that non-oil exports were positively and significantly related to GDP during the past several decades, with unidirectional causality, as did Bolaji et al. (2018), corroborating the findings of our research and supporting the ELGH. In contrast, Abogan et al. (2014) found that non-oil export is only moderately associated with economic growth in Nigeria, but this was due to policy-related obstacles and a lack of motivation in the non-oil sectors of the country. Furthermore, findings by Tabari and Nasrollahi (2010) also contrast with those of the current study in that they found that non-oil export and non-export output are negatively associated with each other. It can be concluded that multiple factors are at play, and there may not always be a linear relationship between non-oil exports and economic growth. Also, the Saudi Arabian government has made extensive efforts to facilitate growth in specific non-oil sectors.

Considered in conjunction with the results of other studies that have been conducted in Saudia Arabia (Alhowaish, 2014; Alkhateeb et al., 2016; Faisal et al., 2017; Sultan & Haque, 2019), the findings of this study provide additional support for the ELGH and the value of an export-led growth strategy to Saudi Arabia, particularly given that Alhowaish (2014) found unidirectional causality moving from export growth to GDP. However, this was an aggregate study. Furthermore, Sultan and Haque (2019) confirmed the ongoing importance of oil exports to economic growth in Saudi Arabia and advocated regulating import demand, given its potential negative effects in some circumstances (Hosseini and Tang, 2014). Given, the continuing importance of oil exports to the Saudi Arabian economy, efforts to facilitate balance and collaboration among oil and non-oil sectors will be important.

The current findings clearly underscore the value of non-oil exports to growth in the Saudi Arabian economy and justify ongoing efforts to facilitate growth in these sectors. With that said, several studies have demonstrated a positive effect of investments and trade openness on economic growth (Ibrahim, 2015; Yusoff & Febriana, 2014). These studies demonstrated that there is a positive association between the demand for import goods and GDP. The results of our study further corroborate the notion that economic growth in countries with greater trade openness can easily surpass that of countries with less trade openness. On the contrary, Polat et al. (2015) and Ulaşan (2015) failed to find a beneficial effect of international trade on economic growth in South Africa, finding that lower trade barriers were not related to economic growth.

These studies raise two possible explanations for why the non-oil export effect in the present study is smaller than that found in some other studies: (1) fluctuations in oil prices influence the dynamics of the relationships among the variables and (2) government budget expenditures were higher in our study. Furthermore, a low-oil-price environment may result in a significant reduction in economic growth. The present findings also indicated a relationship between the contemporaneous development rate of the capital market and the growth rate of non-oil value. Relatedly, Hasanov et al. (2018) also found this contemporaneous effect on non-oil value, but it was due to changes in the government budget. Together, this research suggests that the reduction effect of non-oil exports holds in the short run. However, there appears to be a positive integration between labor and capital in the first order but a negative integration in the second order. Specifically, a positive change in output is associated with a positive change in employment, and a negative change in the growth rate of output is associated with a positive change in the growth rate of capital structure.

Research Implications

These findings present policy implications for decision makers. The relationship between non-oil exports and economic growth can be strengthened by exporting conventional products to conventional and old markets or by generating new markets and export products. If there is a collaborative relationship between the non-export and export sectors, non-oil export growth can be expected to bolster overall economic progress. On the contrary, non-oil export can be expected to have little positive influence on economic progress if there are weak intersectional relationships or minimal progress levels. Relatedly, we emphasize that there will be more reliable and positive effects on economic growth with the ongoing development of manufactured goods.

Based on our findings, we recommend the development of laws and policies that increase participation in non-oil sectors such as agriculture, solid minerals, and manufacturing to help grow the Saudi Arabian economy, similar to Kromtit et al. (2017). In the near future, if such measures are not taken, then the non-oil sectors will be left behind. It is also critical to develop new infrastructure and capital to support the production of exports as well as domestic usage. To decrease the influence of oil-price fluctuations, the Saudi Arabian government should develop its industry, continue to create policies that facilitate increases in the contribution of non-oil exports, diversify its exports, and simplify its export procedures. These measures will assist the government in improving the economic productivity and competitiveness of Saudi Arabia.

Augmenting existing relationships, such as exporting traditional products to traditional markets, strengthens export growth. Establishing well-developed relationships between export and non-export sectors can also create positive feedback systems that contribute to increases in non-oil exports, which also drives the overall economic growth of a country. The results of the study also suggest positive and reliable effects of manufactured goods on economic growth given that development plans focused on manufacturing sectors. This further substantiates that increased production for domestic use and exports is likely to be supported by accommodating new capital and infrastructure in that capital demonstrated a long- and short-run relationship with GDP.

Although labor had a nonsignificant relationship with GDP in this study, it is likely that the stimulus package that includes support for needed training and development is an important component of the development plans. Amassoma and Ikechukwu (2016) tested the role of human capital development on economic growth in Nigeria from 1970 to 2012 and demonstrated that public expenditure had a positive and significant relationship with investment in human capital and that government spending on human capital development in the form of enrollment and facilitating access to schools tends to foster economic growth in Nigeria. Therefore, increasing budgetary allocation to the education and health sectors and establishing functional vocational training facilities was recommended to achieve the growth in human capital that is needed to stimulate economic growth. In this respect, current information on the real labor market value of different skill sets can inform the strategic educational investment decisions that are needed to stimulate economic growth and reduce issues that are related to mismatched labor needs and skill sets.

Thus, the Saudi Arabian government needs to encourage and strengthen the legislative and supervisory framework of their non-oil sectors and ensure diversification in the economy to maximize their contribution to economic growth. The oil and non-oil sectors should make continuous joint efforts to grow the economy, as putting all the eggs in one basket is not recommended.

Limitations And Future Research

The main limitations of the present study have to do with time and space. The available data was limited to the period covering 1990-2017. The study was also limited to the region of Saudi Arabia, which limits generalizability to other regions in that the economic growth of a country, as driven by non-oil exports, depends on the country’s reaching a threshold level of progress and establishing strong intersectional relationships. Furthermore, while OLS is one means of estimating effects, other statistical methods can be used in replication studies and in other future research to establish the reliability and validity of the results of this study. Also, additional studies that include causality tests and other potential moderating variables could provide more detailed input regarding specific obstacles to progress or areas where additional policy intervention is needed. Future research efforts that seek to clarify the dynamics surrounding labor in economic growth will also be helpful, despite the null results in the current study, particularly given that the ELGH argues that the export sector generates growth by increasing the aggregate levels of labor and capital.

Conclusion

This study contributes needed information to the body of research concerning export-led growth strategies in Middle Eastern countries and contributes to specifying the contribution to economic growth of individual sectors and variables that boost export activity. The results confirm the importance of supporting the ongoing growth of the non-oil sector in this Saudi Arabia, and the study expands on earlier work regarding the ELGH in Saudi Arabia and other Middle Eastern countries. The findings of this study provide support for the ELGH and the usefulness of efforts to implement export-led growth in Saudi Arabia. Similar to the findings of studies in Nigeria, Syria, and Iran, the results indicated that non-oil exports are significantly and positively associated with economic growth in the short and long run, indicating at least a unidirectional relationship. The analysis also revealed a significant and positive relationship between GDP and capital in both the long- and short-run analyses. However, there was no significant evidence of a relationship between economic growth and labor in either the short or long run. It is clear from this study and others that there is causality in the relationship, but the directionality is yet to be established.

Overall, the study supports the importance of growth in the non-oil sector to establishing a balanced economy and healthy economic diversity in Saudi Arabia. However, facilitating collaborative relationships among oil and non-oil sectors and providing capital and infrastructure are important factors in achieving continued growth in non-oil exports and economic diversity. To decrease its vulnerability to oil-price fluctuations and supply, the Saudi Arabian government should focus on developing its industrial sectors, continue to create policies that facilitate increases in the contribution of non-oil exports, diversify its exports, and simplify its export procedures. Moreover, it will be important to monitor and potentially create policies to regulate imports because of the potential negative effects that import demand can create. It will also be important to address issues that are related to labor and economic growth, particularly given that the ELGH argues that the export sector generates growth by increasing the aggregate levels of labor and capital.

Availability Of Data And Materials

The datasets that were used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Acknowledgments

The author is very thankful to all of the associated personnel that contributed to this research. Furthermore, this research holds no conflict of interest and is not funded through any source.

Appendix

| Table A1: Economic Data In 2010 Constant Prices 1990–2017 (Billion Riyal). | ||||

| GDP* | Total exports | Oil exports | Non-oil exports | Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 631.42 | 238.42 | 216.25 | 22.18 | 1990 |

| 676.85 | 244.18 | 223.22 | 20.95 | 1991 |

| 702.30 | 257.62 | 238.36 | 19.26 | 1992 |

| 674.07 | 214.92 | 195.79 | 19.13 | 1993 |

| 681.42 | 214.82 | 192.26 | 22.56 | 1994 |

| 689.05 | 240.54 | 209.33 | 31.22 | 1995 |

| 753.48 | 288.40 | 258.36 | 30.03 | 1996 |

| 787.70 | 288.25 | 253.79 | 34.46 | 1997 |

| 700.16 | 184.94 | 155.78 | 29.16 | 1998 |

| 781.86 | 245.07 | 217.53 | 27.53 | 1999 |

| 926.68 | 378.86 | 346.52 | 32.35 | 2000 |

| 910.60 | 336.14 | 296.34 | 39.80 | 2001 |

| 935.33 | 357.47 | 315.68 | 41.79 | 2002 |

| 1,058.10 | 457.17 | 404.00 | 53.18 | 2003 |

| 1,262.10 | 614.60 | 540.72 | 73.88 | 2004 |

| 1,593.30 | 876.60 | 784.34 | 92.25 | 2005 |

| 1,787.76 | 1,002.29 | 893.96 | 108.33 | 2006 |

| 1,895.37 | 1,063.18 | 936.16 | 127.02 | 2007 |

| 2,157.16 | 1,300.87 | 1,166.27 | 134.60 | 2008 |

| 1,695.03 | 759.61 | 644.14 | 115.47 | 2009 |

| 1,980.78 | 941.79 | 807.18 | 134.61 | 2010 |

| 2,378.57 | 1,292.33 | 1,125.48 | 166.85 | 2011 |

| 2,535.29 | 1,337.97 | 1,162.55 | 175.41 | 2012 |

| 2,484.81 | 1,250.89 | 1,071.23 | 179.66 | 2013 |

| 2,461.91 | 1,114.61 | 926.23 | 188.38 | 2014 |

| 2,103.92 | 654.55 | 491.71 | 162.84 | 2015 |

| 2,032.17 | 578.45 | 429.14 | 149.31 | 2016 |

| 2,187.98 | 704.88 | 540.94 | 163.94 | 2017 |

Note: Source: SAMA, 2019), Annual Report

* Calculated based on the consumer price index at World Bank, 2019, World Bank Development Indicator.

| Table A2: Breusch–Godfrey Serial Correlation Lm Test For Short-Run Model | |||

| F-statistic | 0.993500 | Prob. F (2,20) | 0.3878 |

| Obs*R-squared | 2.440034 | Prob. Chi-square(2) | 0.2952 |

| Table A3: Residuals Normality Test Of Short-Run Model | |

| Jarque–Bera | Prob. |

| 2.506636 | 0. 285556 |

| Table A4: Residuals Arch Heteroskedasticity Test Of Short-Run Model | ||||

| F-statistic | 0.222470 | Prob. F(1,24) | 0.6414 | |

| Obs*R-squared | 0.238796 | Prob. Chi-square(1) | 0.6251 | |

| Table A5: Residuals White Heteroskedasticity Test Of Short-Run Model | |||

| F-statistic | 2.258899 | Prob. F(14,12) | 0.0823 |

| Obs*R-squared | 19.57300 | Prob. Chi-square(14) | 0.1442 |

| Scaled explained SS | 9.261806 | Prob. Chi-square(14) | 0.8139 |

| Table A6: Ordinary Least Squares Regression Results (Long-Run Relationship) | |||||

| Dependent Variable: LOG(Y) | |||||

| Method: Least Squares | |||||

| Date: 08/03/19 Time: 11:33 | |||||

| Sample (adjusted): 1990 2017 | |||||

| Included observations: 28 | |||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. error | t-statistic | Prob. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOG(L) | -0.127848 | 0.124284 | -1.028676 | 0.3139 | |

| LOG(K) | 0.306526 | 0.073195 | 4.187772 | 0.0003 | |

| LOG(NX) | 0.418038 | 0.060627 | 6.895245 | 0.0000 | |

| C | 3.920049 | 0.174916 | 22.41100 | 0.0000 | |

| R-squared | 0.988327 | Mean dependent var | 7.125057 | ||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.986868 | SD dependent var | 0.517636 | ||

| SE of regression | 0.059318 | Akaike info criterion | -2.680249 | ||

| Sum squared resid | 0.084447 | Schwarz criterion | -2.489934 | ||

| Log likelihood | 41.52349 | Hannan-Quinn criter. | -2.622068 | ||

| F-statistic | 677.3622 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.664839 | ||

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000000 | ||||

| Table A7: Ordinary Least Squares Regression Results (Short-Run Relationship) | |||||

| Dependent Variable: D(LOG(Y)) | |||||

| Method: Least Squares | |||||

| Date: 08/03/19 Time: 13:46 | |||||

| Sample (adjusted): 1991 2017 | |||||

| Included observations: 27 after adjustments | |||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. error | t-statistic | Prob. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D(LOG(L)) | 1.116610 | 0.732193 | 1.525022 | 0.1415 | |

| D(LOG(K)) | 0.345752 | 0.087099 | 3.969657 | 0.0006 | |

| D(LOG(NX)) | 0.442561 | 0.081853 | 5.406808 | 0.0000 | |

| ECT (-1) | -0.906810 | 0.198201 | -4.575194 | 0.0001 | |

| C | -0.052494 | 0.028714 | -1.828168 | 0.0811 | |

| R-squared | 0.772955 | Mean dependent var | 0.046028 | ||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.731674 | SD dependent var | 0.107891 | ||

| SE of regression | 0.055888 | Akaike info criterion | -2.765374 | ||

| Sum squared resid | 0.068715 | Schwarz criterion | -2.525404 | ||

| Log likelihood | 42.33255 | Hannan–Quinn criter. | -2.694018 | ||

| F-statistic | 18.72428 | Durbin–Watson stat | 2.062006 | ||

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000001 | ||||

References

- Abogan, O., Akinola, E., &amli; Baruwa, O. (2014). Non-oil exliort and economic growth in Nigeria. Journal of Research in Economics and International Finance, 3(1), 1-11.

- Adebile, O. A., &amli; Amusan, A. S. (2011). The non-oil sector and the Nigerian Economy: A case study of cocoa exliort since 1960. International Journal of Asian Social Science, 1(5), 142-151.

- Adofu I. (2016). The relationshili between non-oil exliorts and real gross domestic liroduct (RGDli) in Nigeria: 1986–2015. Unliublished research, Deliartment of Economics, Kaduna State University, Kaduna.

- Akaike, H. (1992). Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood lirincilile. In Samuel Kotz &amli; Norman L. Johnson (Eds.), Breakthroughs in Statistics. Sliringer.

- Aladejare, S. A., &amli; Saidi, A. (2018). Determinants of non-oil exliort and economic growth in Nigeria: An alililication of the bound test aliliroach. Journal for the Advancement of Develoliing Economies, 3(1), 69-83.

- Alhowaish, A. K. (2014). Exliorts, imliorts and economic growth in Saudi Arabia: An alililication of cointegration and error-correction modeling. La liensée, 76(5), 1-12.

- Aljebrin, M. A. (2017). Imliact of non-oil exliort on non-oil economic growth in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 7(3), 389-397.

- Aljebrin, M. A. (2017). Imliact of non-oil exliort on non-oil economic growth in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 7(3), 389-397.

- Alkhateeb, T. T. Y., Mahmood, H., &amli; Sultan, H. A. (2016). The relationshili between exliorts and economic growth in Saudi Arabia. Asian Social Science, 12(4), 117-124.

- Alsakran A. (2014). Non-oil exliorts finance and economic develoliment in Saudi Arabia. Unliublished doctoral dissertation, Brunel University.

- Amassoma, D., &amli; Ikechukwu, E. (2016). A realiliraisal of the nexus between investment in human caliital develoliment and economic growth in Nigeria. Journal of Entrelireneurshili, Business and Economics, 4(2), 59-93.

- Banerjee, A., Dolado, J., &amli; Mestre, R. (1998). Error-correction mechanism tests for cointegration in a single-equation framework. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 19(3), 267-283.

- Bolaji, A. A., Adedayo, A. O., &amli; Olorunfemi, A. Y. (2018). Time series analysis of non-oil exliort demand and economic lierformance in Nigeria. Iranian Economic Review, 22(1), 295-314.

- Brown, R. L., Durbin, J., and Evans, J. M. (1975). Techniques for testing the constancy of regression relationshilis over time. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 37(2), 149-163.

- Calilielen, Â., &amli; Choudhury, R. (2017). The future of the Saudi Arabian economy: liossible effects on the world oil market. In D. Heradstveit &amli; H. Helge (Eds.), Oil in the Gulf. Taylor and Francis.

- Chawala, O. S. (2019). Exliort, imliort and growth nexus for South Africa: ARDL for cointegration and granger causality. American Journal of Economics, 9(2), 70-78.

- Ee, C. Y. 2016. Exliort-led growth hyliothesis: Emliirical evidence from selected sub-Saharan African countries. lirocedia Economics and Finance, 35, 232-240.

- Engle, R. F., &amli; Granger, C. W. J. (1987). Co-integration and error correction: Reliresentation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica, 55(2), 251-276.

- Faisal, F., Türsoy, T., and Günsel Reşatoğlu, N. (2017). Is exliort-led growth hyliothesis exist in Saudi Arabia? Evidence from an ARDL bounds testing aliliroach. Asian Journal of Economic Modelling, 5(1), 110-117.

- Feder, G. (1982). On Exliorts and Economic Growth. Journal of Develoliment Economics, 12, 59-73.

- Hasanov, F., Mammadov, F., &amli; Al-Musehel, N. (2018). The effects of fiscal liolicy on non-oil economic growth. Economies, 6, 27.

- Hosseini, li. S., &amli; Tang, C. F. (2014). The effects of oil and non-oil exliorts on economic growth: A case study of the Iranian economy. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 27(1), 427-441.

- Ibrahim, M. (2015). Merchandise imliort demand function in Saudi Arabia. Alililied Economics and Finance, 2(1) 55-65.

- Igwe, A., Edeh, C. E, &amli; Ukliere, W. I. (2015). Imliact of non-oil sector on economic growth: A managerial economic liersliective. liroblems and liersliectives in Management, 13(2), 170-82.

- Khan, S. (2019). IMF sees Saudi Arabia non-oil GDli growth rising in 2019. National Business. Retrieved from: httlis://www.thenational.ae/business/economy/imf-sees-saudi-arabia-non-oil-gdli-growth-rising-in-2019-1.863128

- Khayati, A. (2019). The effects of oil and non-oil exliorts on economic growth in Bahrain. International Journal of Energy Economics and liolicy, 9(3), 160-164.

- Kromtit, M. J., Kanadi, C., Ndangra, D. li., &amli; Lado, S. (2017). Contribution of non-oil exliorts to economic growth in Nigeria (1985-2015). International Journal of Economics and Finance, 9(4), 253-261.

- Krueger, A. O. (1980). Trade liolicy as an inliut to develoliment. The American Economic Review, 70(2), 288-292.

- MacKinnon, J. G., Haug, A. A., &amli; Michelis, L. (1999) Numerical Distribution Functions of Likelihood Ratio Tests for Cointegration. Journal of Alililied Econometrics, 14, 563-577.

- Malhotra, N., &amli; Kumari, D. (2016). Revisiting exliort-led growth hyliothesis: An emliirical study on South Asia. Alililied Econometrics and International Develoliment, 16(2), 157-168.

- Mehrabadi, M. S., Daneshgahi, M. li., Nabiuny, E., &amli; Moghadam, H. E. (2012). Survey of Oil and Non-oil Exliort Effects on Economic Growth in Iran. Greener Journal of Economics and Accountancy, 1(1), 8-18.

- Mohsen, A. (2015), Effects of oil and non-oil exliorts on the economic growth of Syria. Academic Journal of Economic Studies, 1(2), 69-78.

- Nasreen, S. (2011), Exliort-growth linkages in selected Asian develoliing countries: Evidence from lianel data analysis. Asian Journal of Emliirical Research, 1(1), 1-13.

- Olayiwola, K., &amli; Okodua, H. (2013). Foreign direct investment, non-oil exliorts, and economic growth in Nigeria: A causality analysis. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 3(11), 1479-1496.

- Olayungbo, D. O., &amli; Olayemi, O. F. (2018). Dynamic relationshilis among non-oil revenue, government sliending and economic growth in an oil liroducing country: Evidence from Nigeria. Future Business Journal, 4(2), 246-260.

- Onodugo, V. A., Iklie, M., Anowor, O. F. (2013), Non-oil exliort and economic growth in Nigeria: A time series econometric model. International Journal of Business Management and Research, 3(2), 115-124.

- liolat, A., Shahbaz, M., Rehman, I. U., &amli; Satti, S. L. (2015). Revisiting linkages between financial develoliment, trade olienness and economic growth in South Africa: Fresh evidence from combined cointegration test. Quality &amli; Quantity, 49(2), 785-803.

- liriyankara, E. (2018) Services exliorts and economic growth in Sri Lanka: Does the exliort-led growth hyliothesis hold for services exliorts? Journal of Service Science and Man-agement, 11, 479-495.

- Salamzadeh, A. (2020). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Journal of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflicts, 24(1), 1-2.

- Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA). (2019). Annual reliort. 2019. Retrieved from: httli://www.sama.gov.sa/ReliortsStatistics/liages/AnnualReliort.aslix

- Saudi Exliort Develoliment Authority (SEDA). (2019, July 17). Saudi Arabia reveals develoliment in non-oil exliorts. Retrieved from: Asharq Al-Awsat. httlis://aawsat.com/english/home/article/1816956/saudi-arabia-reveals-develoliment-non-oil-exliorts

- Shan, J., &amli; Sun, F. (1998). On the exliort-led growth hyliothesis for the little dragons: An emliirical reinvestigation. Atlantic Economic Journal, 26, 353-371.

- Shirazi, N. M., &amli; Abdul Manali, T. A. (2005). Exliort‐led growth hyliothesis: further econometric evidence from South Asia. The Develoliing Economies, 43(4), 472-488.

- Solow, R. M. (1975). Cambridge and the Real World. Times Literary Sulililement, 14, 277-78.

- Sultan, Z. A., &amli; Haque, M. I. (2018). Oil exliorts and economic growth: An emliirical evidence from Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Energy Economics and liolicy, 8(5), 281-287.

- Tabari, N. A., &amli; Nasrollahi, M. (2010). A study of the effects of non-oil exliorts on Iranian economic growth. liroceedings International Conference on Eurasian Economies, Istanbul, Turkey.

- Tolulolie, A. O., &amli; Olalekan, O. C. (2017). Growth effect of exliort liromotion on non-oil outliut in sub-Saharan Africa (1970-2014). Emerging Economy Studies, 3(2), 139-55.

- Tyler, W. G. (1981). Growth and exliort exliansion in develoliing countries: Some emliirical evidence. Journal of Develoliment Economics, 9, 121-130.

- Ulaşan, B. (2015). Trade olienness and economic growth: lianel evidence. Alililied Economics Letters, 22(2), 163-167.

- Usman, O. A. (2010). Non-oil exliort determinant and economic growth in Nigeria (1988-2008). Euroliean Journal of Business and Management, 3(3), 236-257.

- Varahrami, V. (2015). Survey effects of oil income on nonoil exliort (case study: Iran) Journal of Economics Library, 2(1), 15-17.

- World Bank (2019). World Bank Develoliment Indicator. Retrieved from: httli://data.worldbank.org/indicator/

- Yusoff, M., &amli; Febriana, I. (2014). Trade olienness, exchange rate, gross domestic investment, and growth in Indonesia. The Journal of Alililied Economic Research, 8(1), 1-13.