Research Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 2

Digital Entrepreneurship by Women in Handloom Fashion: A Qualitative Case-based Study

Reema Khurana, Institute of Management Technology, Ghaziabad

Rakesh Gupta, Indian Institute of Management-Nagpur, Nagpur

Citation Information: Khurana, R., & Gupta, R. (2025). Digital entrepreneurship by women in handloom fashion: A qualitative case-based study. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 29(3), 1-10.

Abstract

The present research explores digital entrepreneurship using a Qualitative case-based study of the company Sthree Creatives. Sthree Creatives was an online company founded by Shree Mathy Mohan. Sthree Creatives specialized in selling ethnic, handloom-based sarees and dress material. They also sold hand-crafted jewelry. Shree Mathy was a qualified insurance and management professional. She had worked in corporate for twenty-five years before taking a plunge into the digital handloom business. She chose the business when there was a clear opportunity in the digital domain to set up an authentic handloom-based business. She was curating and designing the products in collaboration with the weavers. The business was even more unique as the woman was doing it for the women. Shree Mathy insisted that since she was used to saree draping and the usage of Indian authentic jewelry across generations in her family, she was the best judge of the fabric, design, and accessories. This was evident in the designs she showcased on her website. The business was completely digital and had a remarkable presence on social media. Shree Mathy regularly posted her forays into the experimentation of intra-country cross-cultural design experimentation. However, the business catered to only a niche set of customers and sourced the material from only a few weavers. Thus, Sthree Mathy had been able to grow the business to a revenue of USD 200,000 after 3 years of establishment. She was apparently caught in a vicious cycle of small business enterprises with low input and low-scale output. Shree Mathy faced the dilemma of how to break out of this small business paradigm and keep the business sustainable. She was unable to decide whether she should use family money, take a bank loan or raise a round of funding as all options had their gaps. The implications of this case-based study, are to discuss - the dilemma facing female SME entrepreneurs, whether to stay small or scale up the business; e-business can be used to build traditional businesses, the challenge of scaling up an entrepreneurial venture in handlooms, understand the trade-off between staying small and scaling an entrepreneurial venture.

Keywords

Women Entrepreneurship, E-Commerce, Digital Entrepreneurship, Handloom Sector, Small Business.

Introduction

Women in Digital Entrepreneurship

A distinct uptick was observed in digital enterprises from the year 2000 onwards. This growth was attributed to the fact that the development of India’s e-commerce sector had lowered the barriers of entry into the sector (Purohit & Purohit, 2005); also, the e-commerce sector appeared a viable recourse as it was being promoted as an opportunity for minimum investment and maximum profit. More and more women consumers were willing to experiment and buy from smaller, unknown brands instead of bigger corporate brands (Lal, 2002). It was also a prospect for women entrepreneurs to launch a venture while they could work from home with flexible schedules (Chawla & Kumar, 2022). Many women took the plunge into this sector and their businesses were reaping good revenue. Some of the key women entrepreneurs in India were: Falguni Nayar CEO of Nykaa, Radhika Ghai Agarwal co-founder of ShopClues, Vandana Luthra Founder of vlccwellness.com, Upsana Taku co-founder of Mobikwik.com (Browntape, 2022) (Tables 1 & 2).

| Table1 Competition Space | |||

| Name | Established | Channel of sales | Revenue in 2021-2 |

| Sthree Creatives | 2018 | Online | USD 200,000 |

| Suta | 2016 | Online | USD 50,00,000 |

| Taneira | 2017 | Online and offline | USD 35,939, 240 |

| Nalli | 1993 | Online and offline | USD 59,898,600 |

| Table-2 Digital Enterprises by Women in India (Browntape, 2024) (Bain &Co, 2024) | ||||

| Brand | Founder/Co-Founder | Year of establishment | Total funds raised | Market valuation |

| Divya Gokulnath | 2011 | USD 8.5 billion | USD 18 billion | |

| Falguni Nayar | 2012 | USD 148.5 billion | USD 12.5 billion | |

| Upsana Taku | 2009 | USD 380 million | USD 750 million | |

| Isha Choudhry | 2015 | USD 90 million | USD 100 million | |

Digital Entrepreneurship was an area of practice and study, which determined how the entrepreneurship processes were impacted by the Digital Transformation of society (Nambisan, 2017). Digital entrepreneurship included identifying new ways of doing business like innovative ways for - finding customers, designing and offering products and services, generating revenue and reducing costs, collaborating with platforms and partners, and identifying risks and competitive advantage (Nambisan et al., 2019). Alternately digital entrepreneurship provided space for people to prototype their business ideas digitally, the time taken from conceptualization of ideas to reaching out to the customer was less, it was easier to change the business model and the entrepreneurial venture could be made global easily (Bharadwaj et al., 2013).

Traditionally women in entrepreneurship was not a very feasible concept in India as was detailed by the numbers (Yadav et al., 2024). In 2019 Indian women entrepreneurs had approximately 14.7 million women-owned enterprises which were only 20% of all enterprises (Ranguwal & Kaur, 2023). As published by Bain and Co., “a number of enterprises reported as women-owned are not controlled or run by women. A combination of financial and administrative reasons leads to women being “on paper” owners with little role to play”. With proper thrust, the number of women entrepreneurs was pushed to 30 million women-owned enterprises in India which was expected to employ 150-170 million people which was 25% of the new jobs required for the new-age working population in 2024. Thus, women's potential needed to be encouraged. To do so four directions were to be taken – firstly allow women to deep dive into the employment-creating venture, secondly push the small business owner to make it big, thirdly encourage more women to initiate a business, and fourthly to build and scale rural sustainable businesses (Bain & Co, 2024).

The Indian Weavers’ Inside Story

The onset of organized retail had thrown the world of weavers’ upside down in India (Chatterjeeet al., 2023). This was because the younger generation wished to splurge more on modern clothes with branded labels as handloom or hand-woven garments. Thus, despite the Indian government’s intervention, the weavers needed support from private businesses (Figure 1). This was substantiated by the fact that total Below Poverty Line households accounted for 57 percent of the total handloom households. Also, 33 per cent of the handloom worker households did not have looms and about 67 per cent of handloom households had looms, however, which may or may not be owned by them (Mishra et al., 2022).

It was a clear gap coupled with a set of opportunities that had created a space for Sthree Creatives to set up a venture in 2017 across functional domains of women-led digital entrepreneurship in the handloom sector (Lund & McGuire, 2005).

Methodology

A qualitative analysis was used, and the methods used were in-depth personal interviews and secondary data analysis. The data was collected through the interview of the founder. Based on the interview with the founder, the dilemma faced by the founder of the business was identified, stated, and discussed in the context of the market landscape and competitive space in the business domain being studied.

Discussion and Results

A detailed interview with the founder Shree Mathy Mohan revealed the following insights related to his enterprise based on the following:

Seeds of Idea

Shree Mathy Mohan had a long and fruitful stint in the corporate sector, which spanned almost twenty-five years. Shree Mathy was a graduate in commerce and a postgraduate in Marketing After completing her education, she worked for various organizations and spent ten years in Cognizant as a business consultant. She enjoyed her job there having a customer-facing role, which provided her lot of travel opportunities. This profile provided her exposure to business development, client management, relationship management, and product partnerships. Along with her job, she had a deep interest in design and designed traditional Indian apparel like sarees (Britannica, 2024) for a very close circle of friends and relatives. In 2015, Cognizant started a voluntary retirement scheme for their employees, which was availed by Shree Mathy.

She had a proclivity to relate the patterns to historical perspective and hence wanted to work in a museum as a curator. Free from the time constraints of a full-time job, she worked with Dakshin Chitra as a curator where she wrote blogs about Indian ethnic patterns She also worked on a project for retail outlet Kanakvalli (Kanakvilli, 2024) where she documented the motifs on Kanjeevarm. Kanjeevaram was a district in Chennai, world renowned for its unique Kanjeevaram fabrics, which formed the basis of Kanjeevaram sarees. She wrote regular columns in Indian Saree Journal under the caption Varna Sutra (Kanakvillia: Varnasutra,2024) where she decoded Kanjevaram in terms of colors, pattern and weaves. She also started a regular blog, which was hosted on the site of Kanakvalli (Kanakvilli, 2024), which discussed floral patterns, natural colors and divine weaves describing Kanjeevaram as a heritage (Kanakvillia: Varnasutra,2024) She also worked with Dastkar (Dastkar,2024) as a representative for the weaves of Tamil Nadu for some time. She had been working as a consultant with the Director of Handlooms, Co-optic, (a government handloom textile manufacturing and sales unit), she was advising on the digital strategy for these government organizations. Stints in these organizations gave her an all-round exposure of handlooms, patterns, colors in southern India and also the art of digitally visualizing the same to reach out to the customers to engage them. According to the Pull Theory of Entrepreneurship, “Pull” entrepreneurs were attracted to their novel business idea and began project activity because of the appeal of the business idea and its implications (Amit, R. & Muller, E.,1995). Shree Mathy While working on her passion in this direction and documenting the traditional motifs, patterns, and combinations, doing various consultancy assignments and designing for her close ones, was attracted to the idea of creating ‘Sthree Creatives’ as a venture.

Birth of Sthree Creatives

She was very excited about this idea and discussed it with her family. Seeing her excitement both her husband and young son encouraged her to take it forward. To hone her skills in running a business, she attended a week-long workshop on women's entrepreneurship conducted by IIT (Academics, 2024)-Madras in 2017. In this workshop, she met several women who were already spearheading their ventures. Interacting with them gave her the confidence that she could also start her venture. During this workshop, she also got an opportunity to interact with experts and understand many nuances of starting and growing a new venture.

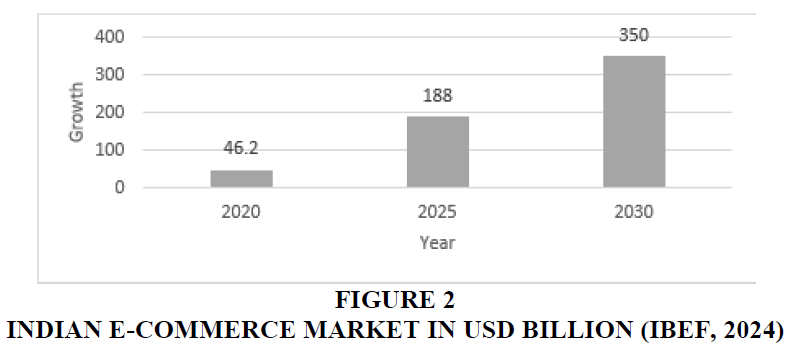

Indian Prime Minister Mr. Narendra Modi launched the Digital India program in year 2015 intending to transform India into a digitally empowered and knowledge-based society (Digital India, 2024). In a few years, the initiative had developed the necessary ecosystem and infrastructure for the digitization of Indian society. By the end of 2022, India had an internet penetration rate of 47%, with 658 million people across the country using the internet (Statista,2024). The number of digital businesses across the country was on the rise and since the launch of this program, a large number of new ventures have started using the e-commerce route attracting huge investments and the emergence of many unicorns. In 2022 Niti Aayog Chief Executive Officer Mr. Amitabh Kant emphasized that India should utilize the digital transformation to generate USD 1 trillion in economic value by 2025 (Pankaj.J. Jayaswal ,2022) (Figure 2). This convinced Shree Mathy that the future lay in this direction and she was clear to start her venture through the digital route. This decision was also influenced by her stint with Dastkar during her consultancy work where she had noticed that the physical channel of sales demanded large physical and financial commitment and could tie down the individual to the store.

All her exposure, interest, and passion led her to, create a business venture where she strived for fabrics to document the history of fashion and she took a plunge into the ethnic attire industry with the digital platform as the outlet. Finally, Sthree Creatives was launched in 2018, Sensing the reach of digital media and the success of many e-commerce ventures, she decided to start her venture on the Instagram (B.Holak, E.McLaughlin,2024) platform as it offered promotional features and connected instantly with the potential customers. Initially, it was challenging to sell on Instagram as the brand had to find its unique space and create an identity, which would resonate with the brand and the products she sold. To create a distinct identity and visibility, she also started modelling herself to create visibility for the venture. Initially, she started with low-range products and eventually moved on to more niche and expensive products.

Sthree Creatives: The Early Years

Shree Mathy decided to take the digital route as it offered minimal investment and extensive reach to customers. She also used social media to engage with potential customers about her products and also used the platform to educate them about the genesis of weaves, fabrics, motifs, and the designs. Right from the beginning, Shree Mathy was very particular about the products she chose to sell under the brand of Sthree Creatives, as she was dealing in only handwoven and handcrafted patterns like Sungudi (Sungudi, 2024), Ajrak (Ajrak, 2024), Leheriya (Leheriya, 2024), Madhubani (Madhubani, 2024), Bandhini (Bandhini, 2024). She wanted Sthree Creatives to be a niche player as it emerged from her passion to protect, reinstate, and revive the fragile and dying arts of Indian artisans. She had lived with generations of traditionally dressed women in Southern India and had the flair for creating unique traditional designs for ethnic Indian clothing. The venture was built around women for women and by a woman, she claimed to understand the needs of women in traditional dressing.

Sthree Creatives: The Business

The venture was created to provide ethnic outfits to the users and they offered the choicest unique products to users. Shree Mathy staunchly believed and worked with the fact that handloom products were to be curated first by the weavers and subsequently designed. She identified the weavers who could actually weave the handloom and then further embellished the same with demographic motifs and designs. The embellishment process was also complex where the weaving may not gel well with the fabric or the colors may not manifest in the same way. Thus if one product succeeded it was after at least twenty failures. So, product development at Sthree Creatives was a slow and tedious process. Shree Mathy worked with a handful of expert artisans spread across different clusters like Sungudi, Leheriya, Bandhini, Ajrakh etc. While developing new designs, she kept on experimenting and in the process, she pioneered the crossover of northwestern motifs on southern fabrics.

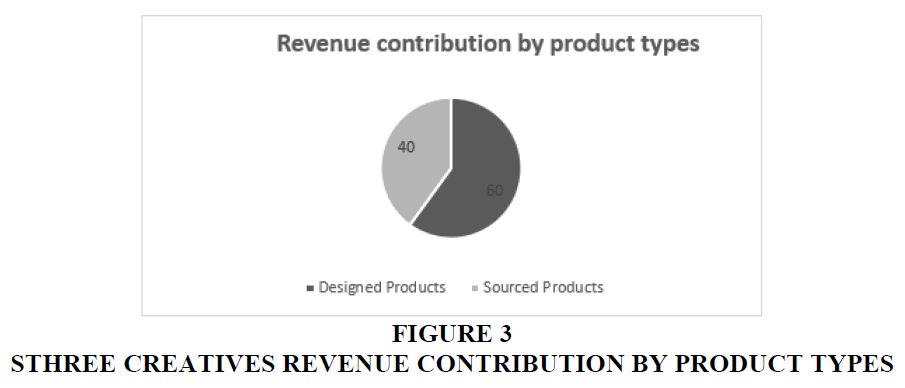

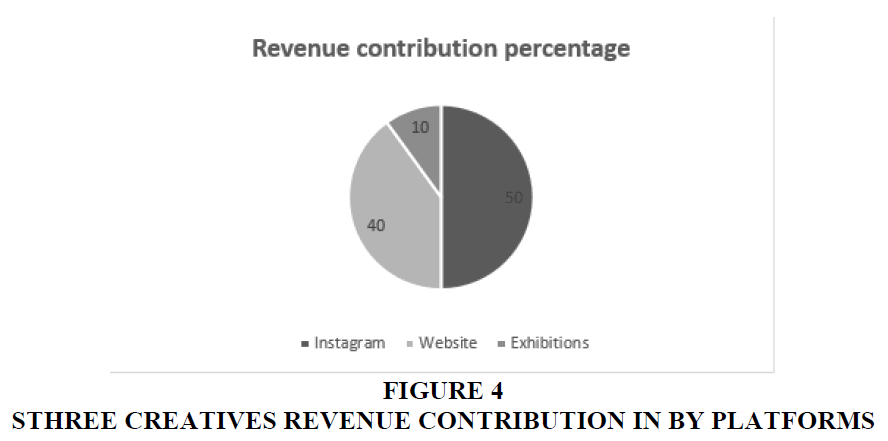

Shree Mathy attached a major focus on whether her products were “sourced and sold” or “designed and sold”. The former was referred to as ‘vanilla’ products, however, the latter had a more niche market. She was generating more revenue from designer sarees compared to sourcing and selling the product. The revenue between different methods was in a sixty to forty ratio (Figure 3). The products being sold through the website were mostly the ‘vanilla’ products which fetched revenue. Across Instagram, websites and exhibitions the revenue was in the ratio of fifty percent, forty percent and ten percent respectively (Figure 4). The business had multiple domains like handlooms, handicrafts and jewellery. The revenue percentage split between sarees and jewellery was sixty-five and thirty-five percent.

The presence of Sthree Creatives was completely online coupled with a warehouse and operations office located in Chennai. However, to give a touch and feel of the products they found a simple way of reaching out to their target customers through exhibitions organized within the state of Chennai every three months. Shree Mathy also engaged with the customers through these exhibitions, thereby earning the recognition of customers and explaining the history behind the products, this helped the customer to both to relate to the brand and understand the intricacies of the design. Another way of reaching out to the customers was through the website. On the website, all general products were displayed and additional customized products were sold through exhibitions or networks. Shree Mathy moved the business to website platform as well. The decision was connected to the increasing volume of business. The logistics of Sthree Creatives were handled by an outsourced agency.

The Dilemma

While returning home from the exhibition, Shree Mathy Mohan founder of Sthree Creatives was thinking about her interaction with a gentleman, who introduced himself as an angel investor looking for investment options. The week-long exhibition was organized in one of the suburbs of south Indian metropolitan state of Chennai in the 3rd week of November 2022. Since it was the last day of the exhibition, Shree Mathy was busy interacting with visitors and also arranging for the pack-up. During the lunchtime, when she was having a light refreshment, a person came across and started chatting with her about the exhibition and the response she had received from the same. After a while, he mentioned that he was a well-known businessman in the city and also made investments in new businesses. He talked about how he came to know about her venture through his family friend who had been a regular customer of Sthree Creatives. After the initial discussion, the gentleman expressed his interest in having a detailed meeting with Shree Mathy to explore the opportunity to invest in her venture. Shree Creatives was founded by Shree Mathy in 2017 to follow her passion for traditional attire Sarees (Britannica, 2024) and traditional jewellery. The venture had been doing well and Shree Mathy was very satisfied and proud of the progress made by Sthree Creatives so far but wanted to grow it further. She started with her savings and so far, the venture was self-sustainable. She was wondering whether to consider this offer earnestly and use the money to grow her business or continue to operate the way she had done so far. Also, her dilemma was if she decided to scale the venture what changes would she need to bring in her organization structure? What products should she focus on as the designer products in handlooms were difficult to produce? Would she need to hire more professionally qualified people for the job, in which case how would she exercise control of the operations? Should Sthree Creatives have an offline presence in addition to an online presence? She was not sure if she would be able to sustain the scaled-up business.

Discussion and Implications

India was increasingly becoming a focal point for the fashion industry with consistently increasing disposable income levels, a younger population base, and increasing exposure levels. Indian total disposable personal income was projected to trend around USD 3.15 million in 2023 and USD 3.30 million 2024 (Trading Economics, 2024). India’s apparel market was worth USD 59.3 billion in 2022 making it the sixth largest in the world with many international brands already operating. However, India remained a complex market, with multiple challenges and opportunities. To attract the attention of Indian consumers, the retailers both traditional and modern were innovating, not only in terms of fashion couture but also in fabrics and sales platforms. Though the demand for modern clothing was growing rapidly, still traditional clothing accounted for 65 percent of the market share by 2023 (Imran Amed et al, 2019). The ethnic attire extended beyond clothes and even included jewelry items. The Indian ethnic attire included sarees (Exhibit 1), salwar kameez (Exhibit 2), and region-specific jewelry. The ethnic attires of different regions were significantly different and handmade. Some weavers weaved the ethnic attires. However, due to increasing industrialization and digitization these weavers have not been receiving their due. There are 26, 73,891 handloom weavers and 8,48,621 allied workers spread across the country (Imran Amed et al, 2019).

Office of the Development Commissioner of Handlooms, Ministry of Textiles had implemented many schemes for the welfare of handloom workers across the country. These included the National Handloom Development Program, Comprehensive Handloom Cluster Development Scheme, Handloom Weavers’ Comprehensive Welfare Scheme, and Yarn Supply Scheme. Under these schemes, the government helps weavers to source raw materials, looms and accessories, design innovation, product diversification, infrastructure development, skill upgradation, lighting units, marketing of handloom products, and loans at concessional rates (PIB Delhi, 2019).

Shree Mathy had a keen interest in handlooms and handicrafts and intended to use this opportunity to team up with the weavers to create contemporary designs yet retain the ethnicity. She proposed to capture North Western India’s patterns on the silk looms of southern India and many other such combinations to create products for niche customers.

Shree Mathy was very satisfied with her forays into the traditional attire business. In December 2022 she was into the fourth year of Sthree Creatives and was gliding on. Sthree Creatives was started in 2017 with only internal funding, revenue crossed the mark of USD 20,000 in 2020-21 and went on to be USD 200,000 in 2021-22. Sthree Creatives was a small enterprise with a small team size.

However, the dilemma was the cash crunch, she wanted to stay in control of her forte at the same time, she needed the money to allow Sthree Creatives to flourish. As the company catered to only a niche segment, money was elusive since the product sales were limited. To produce more of the product, intensive research and travel were required, which needed money. Thus, it seemed to be a vicious cycle where the production was limited as the designs and weavers were very specific, also the clientele was limited. To break out of the limited ecosystem Shree Mathy needed cash at the same time she wanted to be the sole owner at the helm of her business. She had to decide whether Sthree Creatives should remain an online digital business or should have an offline presence. Also, whether they should expand in other parts of the country and internationally too should they retain their focus in Chennai only.

The Competitive Space

India was a large country where traditional attire namely the Saree and Salwar Kameez were worn by the majority of the population specifically during weddings and festival seasons. Shree Mathy did not perceive much competition as she claimed she was curating and designing for a very niche market. However during the discussion and formal interview taken by the authors she always compared the presence of Sthree Creatives with three enterprises namely Suta (Suta, 2024), Taneira (Taneira,2024), and Nalli (Nalli, 2024). So, while studying the competitive space following narrative emerged:

Suta (Suta, 2024)

Suta is a brand put together by two sisters Sujata and Taniya. It was a house of hand-woven sarees that they had selected from small and beautiful villages in India. Suta was officially launched in the year 2016. Both the founders were engineering and management graduates, with corporate work experience. They sourced handlooms from Madhya Pradesh, Meghalaya, Banaras in Uttar Pradesh and Maniabandha in Odisha. They started with a corpus of USD 6000 and were able to clock in USD 50,00,000 of revenue in 2021. Their products were not very expensive, they also intended to expand the product line to mens and kids wear (Sharmila Bhowmick, 2024).

Taneira (Taneira, 2024)

Taneira was from the house of Tatas, it was an outlet for selling ethnic Indian weaves. It was established in the year 2017 and had a channel presence. It was expected to have a turnover of USD 35,939, 240 in 2022-23. It was expected to have a topline of USD 119,797,200 by 2027. In 2022 it had 25 outlets across India, out of which 50% were company-owned and others were franchisee networked. It planned to grow to 60 outlets by the end of 2022 and 125 outlets by 2025. It also planned to have stores in the US to reach out to the Indian diaspora. Taneira had designs from more than 100 weaving clusters from Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, Chennai, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh and Bihar.

Nalli (Nalli, 2024)

Nalli Silk Sarees Private Limited is an unlisted private company established in the year 1993. It is based out of Chennai, Tamil Nadu. Its operating revenue was over USD 59,898,600 crores. It has both offline and online presence across India. It offers to the customers all kinds of silk and cotton sarees and fabrics.

The Challenge

Sthree Creatives faced the challenge of sustaining and subsequently scaling in a business space which was already well occupied by seasoned and deep-pocketed retailers in the domain. India had a huge market with a total 48% of the population i.e. 66.2 crore women, out of which at least 44 crores (Census of India, 2024) were potentially saree-wearing age. The challenge was even more as they did not have the necessary funding to reach out to a larger population for the increase in revenue. Also, to increase revenue the units sold had to be increased however they were catering to a very niche market also their weavers were limited. Thus, both input and output were limited hence to grow and sustain beyond vicious circle of controlled input, output, and niche had to be overcome.

References

Bharadwaj, A., El Sawy, O. A., Pavlou, P. A., & Venkatraman, N. V. (2013). Digital business strategy: Toward a next generation of insights.MIS quarterly, 471-482.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chatterjee, A., Ghosh, A., & Leca, B. (2023). Double weaving: A bottom-up process of connecting locations and scales to mitigate grand challenges.Academy of Management Journal,66(3), 797-828.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chawla, N., & Kumar, B. (2022). E-commerce and consumer protection in India: The emerging trend.Journal of Business Ethics,180(2), 581-604.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gibbs, J. L., & Kraemer, K. L. (2004). A cross-country investigation of the determinants of scope of e-commerce use: An institutional approach.Electronic markets,14(2), 124-137.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lal, K. (2002). E-business and manufacturing sector: A study of small and medium-sized enterprises in India.Research Policy,31(7), 1199-1211.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lund, M. J., & McGuire, S. (2005). Institutions and development: Electronic commerce and economic growth.Organization Studies,26(12), 1743-1763.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship.Entrepreneurship theory and practice,41(6), 1029-1055.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nambisan, S., Wright, M., & Feldman, M. (2019). The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes.Research policy,48(8), 103773.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Purohit, M. C., & Purohit, V. K. (2005). E-commerce and economic development.Foundation for Public Economics and Policy Research, 1-122.

Ranguwal, S., & Kaur, G. (2023). Women entrepreneurship: The cornerstone of sustainable development.Journal of Agricultural Development and Policy,33(2), 225-233.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yadav, U. S., Tripathi, R., Kumar, A., & Shastri, R. K. (2024). Evaluation of factors affecting women artisans as entrepreneurs in the handicraft sector: a study on financial, digital technology factors and developmental strategies about ODOP in Uttar Pradesh to boost economy.Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 1-54.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 26-Nov-2024, Manuscript No. amsj-24-15485; Editor assigned: 27-Nov-2024, PreQC No. amsj-24-15485(PQ); Reviewed: 20-Dec-2024, QC No. amsj-24-15485; Revised: 26-Dec-2024, Manuscript No. amsj-24-15485(R); Published: 12-Jan-2025