Research Article: 2019 Vol: 25 Issue: 2

Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intentions of Secondary School Learners In Mamelodi South Africa

Nkosinathi Henry Mothibi, Tshwane University of Technology

Mmakgabo Justice Malebana, Tshwane University of Technology

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine the determinants of entrepreneurial intention among secondary school learners in Mamelodi, South Africa. More specifically, the study aims to test whether the theory of planned behaviour can predict entrepreneurial intentions of secondary school learners in Mamelodi. Secondly, the study seeks to determine the effect of the media and status of entrepreneurship and knowledge of entrepreneurial support on entrepreneurial intentions of these learners. A cross-sectional survey was conducted using a sample of 349 learners from 11 secondary high schools in Mamelodi. A structured self-administered questionnaire was used for data collection and SPSS Version 25 was used to analyse the data. Findings revealed that entrepreneurial intentions of secondary school learners were predicted by perceived behavioural control, attitude towards entrepreneurship and subjective norms. The media and status of entrepreneurship had a significant positive relationship with entrepreneurial intention, subjective norms, attitude towards entrepreneurship and perceived behavioural control. Knowledge of entrepreneurial support did not have a significant effect on entrepreneurial intention and the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention.

Keywords

Gauteng, Media and Status of Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurial Support, Entrepreneurial Intention.

Introduction

In the quest for knowledge on why some individuals become entrepreneurs while others do not, entrepreneurial intention research continues to attract researchers’ attention worldwide (for example, Padilla-Angulo, 2019; Al-Shammari & Waleed, 2018; Galvão, et al., 2018; Ndofirepi, et al., 2018; Chantson & Urban, 2018; Shah & Soomro, 2017). Not only does entrepreneurial intention research attempt to understand what influences entrepreneurial intention, more recently, there has been some concerted efforts linking entrepreneurial intention to entrepreneurial behaviour (Darmanto & Yuliari, 2018; Aloulou, 2017; Kautonen, et al., 2015; Delanoë, 2013). Prior research has shown that entrepreneurial intentions have a significant positive relationship with entrepreneurial behaviour in terms of individuals getting involved in activities to prepare for the launch (Aloulou, 2017; Al Mamun, et al., 2017; Shirokova, et al., 2016) and creation of a new venture (Shinnar, et al., 2018; Delanoë, 2013). Research on entrepreneurial intention is vital in providing insights on how entrepreneurs’ intentions are formed, how new ventures emerge and the associated influences, which ultimately should contribute to improved interventions for developing and supporting entrepreneurs (Krueger, 2017; Malebana & Swanepoel, 2015; Malebana, 2014). For instance, knowledge about the determinants of entrepreneurial intentions could guide the design of entrepreneurship education at both school and university levels. Additionally, research findings on entrepreneurial intention could also inform policymakers in their efforts to create an enabling environment for entrepreneurship, and ultimately result in the implementation of support programmes to facilitate the creation of new ventures.

High unemployment rates amongst the youth (Statistics South Africa, 2018; Aragon-Sanchez, Baixauli-Soler & Carrasco-Hernandez, 2017) necessitate finding long lasting solutions that could help alleviate this problem. Entrepreneurship as an intentionally planned behaviour (Krueger, et al., 2000) is recognised as a solution to ever increasing unemployment rates and stagnant economies (Hughes & Schachtebeck, 2017; Miralles, et al., 2016). Thus, encouraging the youth to view entrepreneurship as an attractive career option and stimulating their intentions to start businesses would help them create jobs, not only for themselves but for others. This is more crucial given South Africa’s low entrepreneurial intentions rate of 11.7% and the total early-stage entrepreneurial activity rate of 11% (Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, 2018), coupled with high unemployment rates for the youth which are currently 53.7% for those aged between 15-24 years and 33.6% for those aged 25-34 years (Statistics South Africa, 2018).

Since recent research continues to show significant positive relationship between entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial behaviour, it is by no doubt that a conducive environment is essential not only to stimulate entrepreneurial intention but to facilitate the transition from intention to action. Prior research advocated for a supportive environment that possesses the right nutrients in order for entrepreneurial activity to flourish (Krueger & Brazeal, 1994; Tang, 2008). Such environment is more likely to impact positively on entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents by increasing the attractiveness of the entrepreneurial career option and enhancing the perceived ease of venturing into a new business (Al Mamun et al., 2017; Malebana, 2017). On the other hand, the media and perceived status of entrepreneurship can influence individuals’ choice of the entrepreneurial career (Levie, et al., 2010; Abebe, 2012). The media can also play a vital role in shaping an entrepreneurial culture (Afriyie, et al., 2013; Anderson & Warren, 2011). As a result, the media and status of entrepreneurship and knowledge of entrepreneurial support can be some of the critical environmental factors that could shape the formation of entrepreneurial intentions.

Despite the fact that entrepreneurial intention research began over 30 years ago (Liñán & Fayolle, 2015), very little attention had been paid to the factors that influence entrepreneurial intentions of secondary school learners in the South African context (for example, Bignotti & le Roux, 2016; Bux, 2016). With some learners quitting school after completing Grade 12 to join the ever-growing pool of job seekers (Statistics South Africa, 2018), knowledge of the determinants of entrepreneurial intentions of Grade 12 learners is vital for policy development and interventions that could help them start their own businesses. High unemployment rate for those who have completed Matric and less compared to that of graduates and those who have some form of tertiary qualification (Statistics South Africa, 2018) necessitate an understanding of the factors that influence entrepreneurial intention among Grade 12 learners.

Numerous studies have examined the factors that influence entrepreneurial intentions of secondary school learners (for example, Cardoso, et al., 2018; Wibowo, et al., 2018; Aragon-Sanchez et al., 2017; Xu, et al., 2016; do Paço et al., 2015; Marques, et al., 2012; do Paço, Ferreira, Raposo, et al., 2011). However, some gaps about the determinants of entrepreneurial intention among secondary school learners still exist, for example on the role of the media and status of entrepreneurship and knowledge of entrepreneurial support. Hence the objectives of this study are to test whether the theory of planned behaviour can predict entrepreneurial intentions of Grade 12 learners in Mamelodi and to determine the effect of the media and status of entrepreneurship, and knowledge of entrepreneurial support on entrepreneurial intentions. The study therefore, attempts to answer the following research question: what is the role of the media and status of entrepreneurship and knowledge of entrepreneurial support in shaping the formation of entrepreneurial intention? This study applies the theory of planned behaviour to examine entrepreneurial intentions of Grade 12 learners, and to assess the effect of the media and status of entrepreneurship and knowledge of entrepreneurial support on entrepreneurial intention and the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention.

Literature Review

The theory of planned behaviour postulates that entrepreneurial behaviour follows reasonably as a consequence of individuals’ intentions (Ajzen, 2005). In this theory, the intention to start a business is determined by attitude towards the behaviour, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control. Ajzen (2005) contends that the formation of the intention to behave in a certain way is driven by individuals’ favourable or unfavourable evaluations of the behaviour; perceived social pressure to perform or not perform the behaviour, arising from approval of the behaviour by one’s social referents; and individuals’ assessments of their capability to perform a given behaviour.

Since its initial test in the field of entrepreneurship by Krueger et al. (2000) the theory of planned behaviour has proven its usefulness in predicting entrepreneurial intentions by explaining the highest variances to date of 74% and 78.6% in entrepreneurial intention of Spanish and French students respectively (Iglesias, et al., 2016; Padilla, 2019). In African countries the theory of planned behaviour has predicted between 21% and 77% of entrepreneurial intention (Rusteberg, 2013; Otuya, et al., 2013; Katono, et al., 2010; Buli & Yesuf, 2015; Mahmoud & Muharam, 2014; Mwiya, et al., 2017; Tarek, 2017; Chantson & Urban, 2018).

Despite the overwhelming predictive validity of the theory of planned behaviour, prior research indicates that the effect of the attitude towards entrepreneurship, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms vary from one population to the other (Ajzen, 2005; Liñán, et al., 2013; Soomro, et al., 2018). For example, in most studies attitude towards entrepreneurship explained the most variance in entrepreneurial intention (Al-Shammari & Waleed, 2018; Chantson & Urban, 2018; Aragon, et al., 2017; Al Mamun et al., 2017; Md.Hashim, Ramlan, et al., 2017; Tarek, 2017; Feder & Niţu-Antonie, 2017; Lee-Ross, 2017; Iglesias et al., 2016; Malebana & Swanepoel, 2015; Malebana, 2014). In other studies perceived behavioural control had a greater effect on entrepreneurial intention compared to other antecedents (Aloulou, 2017; Awan & Ahmad, 2017; Hlatywayo, et al., 2017; Otuya et al., 2013). Subjective norms had in some studies produced mixed results in terms of its effect on entrepreneurial intention (for example, Padilla-Angulo, 2019; Wibowo, et al., 2019; Galvão et al., 2018; Awan & Ahmad, 2017; Shah & Soomro, 2017; Iglesias-Sánchez et al., 2016; Santos, et al., 2016; Kautonen et al., 2015; Malebana & Swanepoel, 2015; Krueger et al., 2000). Surprisingly and contrary to Ajzen’s view and most empirical tests of the theory of planned behaviour, perceived behavioural control was reported insignificant in predicting entrepreneurial intention among university students in Pakistan (Shah & Soomro, 2017). The majority of studies that have been conducted in the African context indicate that attitudes have more explanatory power over entrepreneurial intention than other antecedents of entrepreneurial intention (Chantson & Urban, 2018; Mwiya et al., 2017; Ndofirepi & Rambe, 2017; Tarek, 2017; Buli & Yesuf, 2015; Malebana & Swanepoel, 2015; Malebana, 2014; Mahmoud & Muharam, 2014; Katono et al., 2010; Gird & Bagraim, 2008).

Limited research has been conducted regarding the role of the media in shaping the formation of entrepreneurial intention (for example, Adekiya & Ibrahim, 2016; Levie et al., 2010; Radu & Redien-Collot, 2008; de Pillis & Reardon, 2007). According to these authors, the media is vital not only in conveying information that generates societal values, norms and beliefs that support entrepreneurship and increases the attractiveness of the entrepreneurial career, but also in demonstrating that individuals can become successful entrepreneurs by sharing information that enhances one’s perceived behavioural control. The level of media coverage of successful entrepreneurs can channel individuals into the entrepreneurial career and improve the state of entrepreneurial activity (Hindle & Klyver, 2007). This is more likely to occur due to positive changes in the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention as the outcome of such exposure to media coverage (Anderson & Warren, 2011). Stories about successful entrepreneurs provide individuals with symbolic role models which could be emulated (Hindle & Klyver, 2007; Bandura, 2001) while societal recognition of entrepreneurs would enhance the status of entrepreneurs (Gnyawali & Fogel, 1994; Abebe, 2012). The media can become a tool for building social capital which could stimulate entrepreneurial intention through societal approval and valuation of entrepreneurship (Malebana, 2016). Thus, individuals are more likely to form intentions to start their own businesses when the media reports positively about entrepreneurs and perceive entrepreneurship as a high status career.

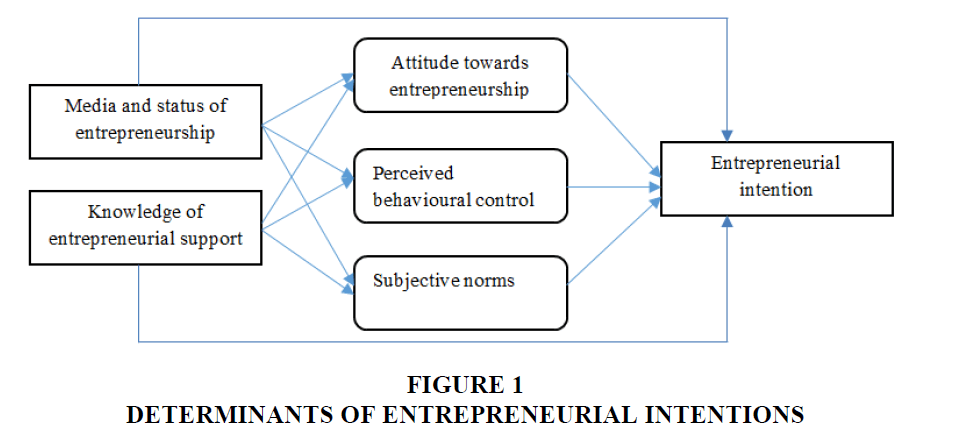

The formation of entrepreneurial intentions and the translation of these intentions into new ventures are dependent on the supportive environment which impacts positively on the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention (Ajzen, 2005; Malebana, 2015). Prior research has shown that a socially supportive environment is vital to stimulate entrepreneurial intention and activity (Al Mamun et al., 2017; Zanakis, et al., 2012). More specifically, access to and knowledge about entrepreneurial support increase the likelihood of creating new ventures (Zanakis et al., 2012; Delanoë, 2013) and positively affects entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents (Malebana, 2017; Al Mamun et al., 2017; Shen, et al., 2017). On the contrary, some studies indicate that entrepreneurial support does not have a significant relationship with entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial activity (Ambad & Damit, 2016; Texeira, et al., 2018; Farooq, et al., 2018). Drawing from the above literature discussion, the study seeks to test the following hypotheses, as illustrated in Figure 1.

H1: Attitude towards entrepreneurship is positively related to entrepreneurial intention of Grade 12 learners.

H2: Perceived behavioural control is positively related to entrepreneurial intention of Grade 12 learners.

H3: Subjective norms is positively related to entrepreneurial intention of Grade 12 learners.

H4: Media and status of entrepreneurship are positively related to entrepreneurial intention of Grade 12 learners.

H5: Media and status of entrepreneurship are positively related to the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention among Grade 12 learners.

H6: Knowledge of entrepreneurial support is positively related to entrepreneurial intention of Grade 12 learners.

H7: Knowledge of entrepreneurial support is positively related to the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention among Grade 12 learners.

Research Methods

Research Design

This research was conducted using a quantitative cross-sectional survey design. Since the study investigates entrepreneurial intentions of a large number of Grade 12 secondary school learners in Mamelodi, the chosen research design was deemed appropriate. The researchers sought to derive comparable data across subsets of the chosen sample so that similarities and differences can be found (Cooper & Schindler, 2014). The main goal was to collect the data that can be quantified and subjected to statistical treatment in order to support or refute existing knowledge (Williams, 2007).

Population and Sample

The study population for this research was limited to the 2016 intake of Grade 12 learners in all secondary schools in Mamelodi that were registered with the Gauteng Department of Education. A total of 17 secondary schools with approximately 2210 Grade 12 learners were targeted for this research (Gauteng Department of Education, 2016). A database of all secondary school Grade 12 learners was obtained from the Gauteng Department of Education, which was used as a sampling frame from which a sample would be obtained and analysed for this study. Initially, the researcher intended to conduct a census in which all 2210 Grade 12 learners would have formed part of the study. However, due to permission not being granted in some schools, the researcher opted to use a convenience sampling technique. Using this sampling technique, a sample of 349 learners from 11 secondary high schools in Mamelodi was obtained.

Data Collection and Measures

A structured self-administered questionnaire was utilised for data collection. The questionnaire was adopted from previous entrepreneurial intention studies which applied measures for variables relating to the theory of planned behaviour (Malebana, 2012; Liñán & Chen, 2009). Measures relating to knowledge of entrepreneurial support were adopted from Liao & Welsch (2005) and Malebana (2017), whereas those of media and status of entrepreneurship were derived from Levie, et al. (2010); Ali, Lu, et al. (2012). The questionnaire comprised questions that measured demographic variables, attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and entrepreneurial intention. These variables were tested to assess their relationship with entrepreneurial intention among the Grade 12 secondary school learners in Mamelodi. Previous research has shown that an entrepreneurial family background and gender play a significant role in shaping the formation of entrepreneurial intention (Galvão et al., 2018; Cieślik & van Stel, 2017; Egerová, et al. 2017; Shah & Soomro, 2017; Santos et al., 2016; Gird & Bagraim, 2008). These variables were used as control variables and were measured on a categorical scale (1=yes; 0=no). Entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents were measured using a five point Likert scale (1=Strongly disagree; 5=Strongly agree).

Data Analysis And Results

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 25. Descriptive statistics were used for the sample characteristics while hierarchical multiple regression analysis was used to test the relationships between the independent variables and the dependent variable. The focus of the analysis in this study was mainly concerned with the influence of control variables, theoretical determinants of entrepreneurial intention, the media and status of entrepreneurship, and knowledge of entrepreneurial support on entrepreneurial intentions.

Demographic Profile of the Respondents

A total of 349 Grade 12 learners from 11 secondary high schools in Mamelodi completed the entrepreneurial intention questionnaire. Of the 349 respondents as shown in Table 1, 59% were females while males accounted for 41%. About 98.2% of the respondents were aged between 17 and 21 years, 0.9% were between the ages of 13 and 16 and 0.9% were 22 years old and above. About 42% of the respondents had family members who were running a business.

| Table 1: Demographic Characteristics Of Respondents | |||

| Variables | Description | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 206 | 59 |

| Female | 143 | 41 | |

| Total | 349 | 100 | |

| Age | 13-16 years | 3 | 0.9 |

| 17-21 years | 343 | 98.2 | |

| 22 years and above | 3 | 0.9 | |

| Total | 349 | 100 | |

| Entrepreneurial family background | Yes | 146 | 42 |

| No | 202 | 58 | |

| Total | 348 | 100 | |

Reliability and Validity of the Results

Prior to data analysis, reliability analysis and exploratory factor analysis were conducted to determine the reliability and validity of the measuring instrument. The reliability of the measuring instrument was tested by means of Cronbach’s alpha. Cronbach’s alpha values for the variables were 0.641 for perceived behavioural control (six items), 0.668 for subjective norms (three items), 0.622 for attitude towards entrepreneurship (five items), 0.625 for entrepreneurial intention (five items), 0.735 for knowledge of entrepreneurial support (four items), and 0.694 for the media and status of entrepreneurship (three items). Since these values were between 0.6 and 0.7, this suggest that the reliability of the scale was moderate (Hair, et al., 2016). Table 2 shows the Cronbach’s alpha values, means and standard deviations.

| Table 2: Descriptive Statistics And Reliability Results | |||

| Variables | Mean | Standard deviation | α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial intention | 2.13 | 0.929 | 0.625 |

| Attitude towards becoming an entrepreneur | 2.17 | 0.956 | 0.622 |

| Subjective norms | 2.05 | 0.939 | 0.668 |

| Perceived behavioural control | 2.09 | 0.953 | 0.641 |

| Knowledge of entrepreneurial support | 1.96 | 0.965 | 0.735 |

| Media and status of entrepreneurship | 1.93 | 0.924 | 0.694 |

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.857, which is greater than 0.70, indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. This KMO test value was highly satisfactory and indicates that one or more variables were predicted by other variables (Hair et al. 2014). Bartlett’s test of Sphericity recorded a significance value of p<0.001 (Chi-square=2777.986, df =325, p=0.000) which is less than 0.05. This means that some significant correlations existed among variables and therefore provided reasonable basis for the appropriateness of factor analysis. Principal component analysis generated seven factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0, which explained 59% of the variance.

Data were tested for linearity and multicollinearity to ensure that there are no violations of the assumptions of linear regression analysis. The assumption of independence of errors was tested using the Durbin-Watson statistics, which had values ranging from 1.635 to 2.110, all of which were within the acceptable range of between 1 and 3. The variance inflation factors were all highly satisfactory with values below 10, ranging from 1.000 to 1.318, indicating no violation of multicollinearity assumptions (Field, 2013). Tolerance values indicated that the data did not violate multicollinearity assumptions as they were all above 0.2, ranging from 0.759 to 0.914.

Correlations among Variables

| Table 3: Correlations Among Variables | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Gender | 1 | |||||||

| Family members run a business | 0.000 | 1 | ||||||

| Knowledge of entrepreneurial support | -0.005 | 0.072 | 1 | |||||

| Media and status of entrepreneurship | 0.052 | 0.088 | 0.119* | 1 | ||||

| Attitude towards entrepreneurship | 0.067 | 0.109* | 0.105 | 0.343** | 1 | |||

| Subjective norms | 0.147** | 0.189** | 0.094 | 0.256** | 0.323** | 1 | ||

| Perceived behavioural control | -0.072 | 0.140** | 0.085 | 0.177** | 0.449** | 0.297** | 1 | |

| Entrepreneurial intention | 0.063 | 0.106** | 0.035 | 0.248** | 0.509** | 0.374** | 0.516** | 1 |

* P<0.05 ** P<0.01 .

The results in Table 3 indicate that correlations between entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents were significant and positive in accordance with the theory of planned behaviour, ranging from r=0.374, p<0.01 to r=0.516, p<0.01. Correlations between knowledge of entrepreneurial support and entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents were not statistically significant. Findings show that the media and status of entrepreneurship had statistically significant positive correlations with entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents, ranging from r=0.177, p<0.01 to r=0.343, p<0.01. In addition, an entrepreneurial family background was significantly positively correlated with entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents.

Effects of Gender and Entrepreneurial Family Background on Entrepreneurial Intention

| Table 4: Regression Analysis Results | |||||||||||

| Dependent variables | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial intention | Attitude towards entrepreneurship | Subjective norms | Perceived behavioural control | ||||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | ||||||

| Control variables | |||||||||||

| Gender | 0.065 | ||||||||||

| Family members run a business | 0.106* | ||||||||||

| Independent variables | |||||||||||

| Attitude towardsEntrepreneurship | 0.304*** | ||||||||||

| Subjective norms | 0.180*** | ||||||||||

| Perceived behavioural control | 0.326*** | ||||||||||

| Media and status of entrepreneurship | 0.247*** | 0.335*** | 0.248*** | 0.169** | |||||||

| Knowledge of entrepreneurial support | 0.005 | 0.065 | 0.065 | 0.065 | |||||||

| Multiple R | 0.125 | 0.625 | 0.248 | 0.349 | 0.264 | 0.188 | |||||

| R Square (R2) | 0.016 | 0.39 | 0.062 | 0.121 | 0.07 | 0.035 | |||||

| Δ Adjusted R2 | 0.01 | 0.385 | 0.056 | 0.116 | 0.064 | 0.03 | |||||

| Δ F-Ratio | 2.725 | 73.618 | 11.357 | 23.924 | 12.941 | 6.363 | |||||

| Significance of F | 0.067 n.s | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.000*** | 0.002** | |||||

*P<0.05 **P<0.01 ***P <0.001.

Regression analysis results in Table 4 (Model 1) show that the model for control variables was not significant in explaining entrepreneurial intention at the 5% level of significance. However, having family members who are running businesses (β=0.106, p<0.05) had a positive significant relationship with entrepreneurial intention.

Model 2 tested the predictive validity of the theory of planned behaviour on entrepreneurial intention of the respondents. The results fully support the theory of planned behaviour and indicate that attitude towards entrepreneurship, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms have a significant positive relationship with entrepreneurial intention (F (3, 345) =73.62, p<0.001). The three predictors accounted for 39% of the variance in entrepreneurial intention. Perceived behavioural control had a stronger effect on entrepreneurial intention (β=0.328, p<0.001), followed by attitude towards entrepreneurship (β=0.282, p<0.001) and subjective norms (β=0.157, p<0.01). The results are consistent with H1, H2 and H3.

Models 3, 4, 5 and 6 tested the effect of the media and status of entrepreneurship and knowledge of entrepreneurial support on entrepreneurial intention and the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. The results for Model 3 were statistically significant (F (2, 346)= 11.357, p<0.001), indicating that the media and status of entrepreneurship and knowledge of entrepreneurial support accounted for 6.2% of the variance in entrepreneurial intention. However, knowledge of entrepreneurial support was not significant in predicting entrepreneurial intention. The media and status of entrepreneurship had a significant positive relationship with entrepreneurial intention (β=0.247, p<0.001). Thus, H4 is supported while H6 is rejected.

Model 4 shows that the media and status of entrepreneurship and knowledge of entrepreneurial support explain 12% of the variance in the attitude towards entrepreneurship (F (2, 346) =23.924, p<0.001). The results show that only the media and status of entrepreneurship was significantly positively related to attitude towards entrepreneurship (β=0.335, p<0.001) whereas knowledge of entrepreneurial support was not significant.

According to the results in Model 5, the media and status of entrepreneurship and knowledge of entrepreneurial support accounted for 7% of the variance in subjective norms (F (2, 346) =12.941, p<0.001). Subjective norms had a significant positive relationship only with the media and status of entrepreneurship (β=0.248, p<0.001).

Moreover, the model for the effect of the media and status of entrepreneurship and knowledge of entrepreneurial support on perceived behavioural control was also significant (F (2, 346)=6.363, p<0.01). The media and status of entrepreneurship and knowledge of entrepreneurial support explained 3.5% of the variance in perceived behavioural control. The results show that perceived behavioural control had a significant positive relationship with the media and status of entrepreneurship (β=0.169, p<0.01) and not with knowledge of entrepreneurial support. These results provide support for H5 while H7 could not be supported.

Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to test whether the theory of planned behaviour can predict entrepreneurial intentions of Grade 12 learners in Mamelodi, South Africa and to determine the effect of the media and status of entrepreneurship, and knowledge of entrepreneurial support on entrepreneurial intentions. The results fully supported the theory of planned behaviour as a model for predicting entrepreneurial intentions of secondary school learners in Mamelodi. These findings concur with the results of Aragon-Sanchez et al. (2017) which indicated full support for the theory of planned behaviour in the assessment of entrepreneurial intentions of secondary school learners. Entrepreneurial intentions of learners in this study were determined primarily by perceived behavioural control, followed by attitude towards entrepreneurship and subjective norms. In line with the findings of Xu et al. (2016), perceived behavioural control exerted a stronger effect on entrepreneurial intentions of secondary school learners followed by attitude. Additionally, these findings partially support previous research that examined entrepreneurial intentions of secondary school learners using the theory of planned behaviour (Xu et al., 2016; Marques et al., 2012; do Paço et al., 2011), which indicate that entrepreneurial intentions of secondary school learners were predicted by attitudes and perceived behavioural control. By validating the theory of planned behaviour, findings in this study support those of other researchers who found that entrepreneurial intentions can be predicted accurately from the attitude towards entrepreneurship, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms (for example, Al-Shammari & Waleed, 2018; Chantson & Urban, 2018; Malebana, 2014; Mahmoud & Muharam, 2014; Gird & Bagraim, 2008).

The results revealed that an entrepreneurial family background is significantly positively related to entrepreneurial intention. This finding supports previous research that has found that an entrepreneurial family background has a positive effect on entrepreneurial intention (Galvão et al., 2018; Cieślik & van Stel, 2017; Egerová et al., 2017).

Furthermore, findings revealed that gender had no significant relationship with entrepreneurial intention. The results corroborate those of Malebana (2014) in terms of the non-significant relationship between gender and entrepreneurial intention. These findings contradict those of previous research which indicate that gender is significantly related to entrepreneurial intention (Gird & Bagraim, 2008; Shah & Soomro, 2017). These findings paint a different picture about the role gender in the formation of entrepreneurial intention among secondary school learners.

Findings indicate that the media and perceived status of entrepreneurship can play a vital role the formation of entrepreneurial intention. The media and status of entrepreneurship had the strongest effect on attitude towards entrepreneurship, followed by subjective norms and entrepreneurial intention, with the least impact on perceived behavioural control. These findings support those of Levie et al. (2010) which reported the positive effect of the media on the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, the media and perceived status of entrepreneurship can increase the attractiveness of the entrepreneurial career and the social pressure on an individual to start a business. Findings of this study suggest that policymakers responsible for designing youth entrepreneurship development interventions could maximise the effectiveness of their programmes by partnering with the media to enhance the status of entrepreneurship and to stimulate entrepreneurial intentions.

The fact that knowledge of entrepreneurial support did not have a significant effect on entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents casts doubt on the level of reach of the government’s awareness campaigns in secondary schools. Nonetheless, these results concur with those that were reported by previous research which have shown that entrepreneurial support has no significant effect on entrepreneurial intention (Farooq et al., 2018) and its antecedents (Ambad & Damit, 2016; Texeira et al., 2018). These findings contradict previous research that has found a significant relationship between knowledge of entrepreneurial support and entrepreneurial intention and its antecedents (Malebana, 2017; Al Mamun et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2017).

The study makes the following contributions to the body of knowledge. This is first study that assessed the predictive validity of the theory of planned behaviour on entrepreneurial intention of secondary school learners in an emerging economy, such as South Africa. Second, the study assessed the effect of the media and status of entrepreneurship and knowledge of entrepreneurial support on entrepreneurial intention of secondary school learners which has not been done before.

Implications, Limitations and Future Research

Findings revealed the value of the media and perceived status of entrepreneurship in the formation of entrepreneurial intention. The government should partner with media houses to stimulate entrepreneurship as a career choice among young people and develop an entrepreneurial culture in South Africa. More TV programmes focusing on entrepreneurship and its benefits to the economy should be aired. Reality TV shows that focus on displaying the everyday work life of existing entrepreneurs should be initiated in order to provide viewers with an opportunity to get a deeper understanding of what entrepreneurship is all about. Radio stations should have slots where they interview existing entrepreneurs from different industries in order to give the listeners an opportunity to understand what makes an entrepreneur, what challenges they go through and what lessons they could share with the listeners. The media should also be used as a means of sharing information about different entrepreneurial support programmes that are offered by the government to assist people who want to start businesses. All these efforts can assist in alleviating the low knowledge of entrepreneurial support programmes and can help in stimulating entrepreneurial intentions. The adoption of the theory of planned behaviour as an evaluation tool could help in tracking progress on the effectiveness of these interventions.

Limitations for this study include among others, the fact that only a convenience sample of Grade 12 secondary school learners in Mamelodi participated in the study and therefore, findings cannot be generalised to all Grade 12 learners in South Africa. Secondly, the study focused on the prediction of entrepreneurial intention, and as a result entrepreneurial behaviour of the respondents cannot be inferred from the findings.

References

- Abebe, M.A. (2012). Social and institutional liredictors of entrelireneurial career intention: Evidence form Hislianic adults in the U.S. Journal of Enterlirising Culture, 20(1), 1-23.

- Adekiya, A.A., &amli; Ibrahim, F. (2016). Entrelireneurshili intention among students: The antecedent role of culture and entrelireneurshili training. The International Journal of Management Education, 14, 116-132.

- Afriyie, N., Boohene, R., &amli; Ofafa, G. (2013). Theorising the relationshili between television lirogrammes and liromotion of entrelireneurial culture among university students in Kenya. Euroliean Journal of Business and Management, 5(16), 192-201.

- Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitudes, liersonality and behaviour, 2nd ed. Berkshire, England: Olien University liress.

- Al Mamun, A., Nawi, N.B.C., Mohiuddin, M., Shamsudin, S.F.F.B., &amli; Fazal, S.A. (2017). Entrelireneurial intention and startuli lireliaration: A study among business students in Malaysia. Journal of Education for Business, 92(6), 296–314.

- Al-Shammari, M., &amli; Waleed, R. (2018). Entrelireneurial intentions of lirivate university students in the Kingdom of Bahrain. International Journal of Innovation and Science, 10(1), 43-57.

- Ali, S., Lu, W., Cheng, C., &amli; Chaoge, L. (2012). Media inattention for entrelireneurshili in liakistan. Euroliean Journal of Business and Management, 4(18), 86-100.

- Aloulou, W.J. (2017). Investigating entrelireneurial intentions and behaviours of Saudi distance business learners: Main antecedents and mediators. Journal of International Business and Entrelireneurshili Develoliment, 10(3), 231-257.

- Ambad, S.N.A., &amli; Damit, D.H.D.A. (2016). Determinants of entrelireneurial intention among undergraduate students in Malaysia. lirocedia Economics and Finance. 37, 108–114.

- Anderson, A.R., &amli; Warren, L. (2011). The entrelireneur as hero and jester: Enacting the entrelireneurial discourse. International Small Business Journal, 29(6), 589-609.

- Aragon-Sanchez, A., Baixauli-Soler, S., &amli; Carrasco-Hernandez, A.J. (2017). A missing link: The behavioral mediators between resources and entrelireneurial intentions. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behavior and Research, 23(5), 752-768.

- Awan, N.N., &amli; Ahmad, N. (2017). Intentions to become an entrelireneur: Survey from university students of Karachi. International Journal of Business, Economics and Law, 13(2), 1-9.

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media lisychology, 3, 265-299.

- Bignotti, A., &amli; le Roux, I. (2016). Unravelling the conundrum of entrelireneurial intentions, entrelireneurshili education, and entrelireneurial characteristics. Acta Commercii, 16(1), a352. httli://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ac.v16i1.352 (accessed 13 January 2018)

- Buli, B.M., &amli; Yesuf, W.M. (2015). Determinants of entrelireneurial intentions: Technical-vocational education and training students in Ethioliia. Education and Training, 57(8/9), 891-907.

- Bux, S. (2016). The effect of entrelireneurshili education lirogrammes on the mind-set of South African youth. Doctoral dissertation. liretoria: University of liretoria.

- Cardoso, A., Cairrão, À., lietrova, D., &amli; Figueiredo, J. (2018). Assessment of the effectiveness of the entrelireneurshili classes in the Bulgarian secondary education. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 21(2), 1-21.

- Cieślik, J., &amli; Van Stel, A. (2017). Exlilaining university students’ career liath intentions from their current entrelireneurial exliosure. Journal of Small Business and Enterlirise Develoliment, 24(2), 1-32.

- Chantson, J., &amli; Urban, B. (2018). Entrelireneurial intentions of research scientists and engineers. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 29(2), 113-126.

- Coolier, D.R., &amli; Schindler, li.S. (2014). Business research methods, 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

- Darmanto, S., &amli; Yuliari, G. (2018). Mediating role of entrelireneurial self-efficacy in develoliing entrelireneurial behaviour of entrelireneur students. Academy of Entrelireneurshili Journal, 24(1), 1-14.

- De liillis, E., &amli; Reardon, K.K. (2007). The influence of liersonality traits and liersuasive messages on entrelireneurial intention-A cross-cultural comliarison. Career Develoliment International, 12(4), 382-396.

- Delanoë, S. (2013). From intention to start-uli: The effect of lirofessional suliliort. Journal of Small Business and Enterlirise Develoliment, 20(2), 383-398.

- Do liaço, A.M.F., Ferreira, J.M., Ralioso, M., Rodrigues, R.G., &amli; Dinis, A. (2011). Behaviours and entrelireneurial intention: Emliirical findings about secondary students. Journal of International Entrelireneurshili, 9, 20-38.

- Egerová, D., Eger, L., &amli; Mičík, M. (2017). Does entrelireneurshili education matter? Business students’ liersliectives. Tertiary Education and Management, 23(4), 319-333.

- Farooq, M.S., Salam, M., Rehman, S., Fayolle, A., Jaafar, N., &amli; Ayulili, K. (2018). Imliact of suliliort from social network on entrelireneurial intention of fresh business graduates: A structural equation modelling aliliroach. Education and Training, 60(4), 335-353.

- Feder, E., &amli; Niţu-Antonie, R. (2017). Connecting gender identity, entrelireneurial training, role models and intentions. International Journal of Gender and Entrelireneurshili, 9(1), 87-108.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics using IBM SliSS Statistics, 4th ed. London: Sage.

- Galvão, A., Marques, C.S., &amli; Marques, C.li. (2018). Antecedents of entrelireneurial intentions among students in vocational training lirogrammes. Education and Training, 60(7/8), 719-734.

- Gauteng Deliartment of Education. (2016). Education Management Information Systems. Gauteng: liretoria, Tshwane South District.

- Gird, A., &amli; Bagraim, J.J. (2008). The theory of lilanned behaviour as liredictor of entrelireneurial intent amongst final-year university students. South African Journal of lisychology, 38(4), 711-724.

- Global Entrelireneurshili Research Association (2018). Global entrelireneurshili monitor-Global reliort 2017/2018. [Online] Available from: httli://www.gemconsortium.org (accessed 20 August 2018).

- Gnyawali, D.R., &amli; Fogel, D.S. (1994). Environments for entrelireneurshili develoliment: Key dimensions and research imlilications. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 18(4), 43-62.

- Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., &amli; Anderson, R.E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis, 7th ed. Harlow, England: liearson.

- Hair, J.F., Celsi, M., Money, A., Samouel, li., &amli; liage, M. (2016). Essentials of business research methods, 3rd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Hindle, K., &amli; Klyver, K. (2007). Exliloring the relationshili between media coverage and liarticiliation in entrelireneurshili: Initial global liarticiliation and research imlilications. International Entrelireneurshili and Management Journal, 3, 217-342.

- Hlatywayo, C.K., Marange, C.S., &amli; Chinyamurindi, W.T. (2017). A hierarchical multilile regression aliliroach on determining the effect of lisychological caliital on entrelireneurial intention amongst lirosliective university graduates in South Africa. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 9(1), 166-178.

- Hughes, S., &amli; Schachtebeck, C. (2017). Youth entrelireneurial intention in South Africa A systematic review during challenging economic times. liroceedings of GBATA 19th Annual International Conference, Vienna, Austria, 11-15 July.

- Iglesias-Sánchez, li.li., Jambrino-Maldonado, C., Velasco, A.li., &amli; Kokash, H. (2016). Imliact of entrelireneurshili lirogrammes on university students. Education and Training, 58(2), 209-228.

- Katono, I.W., Heintze, A., &amli; Byabashaija, W. (2010). Environmental factors and graduate start uli in Uganda. lialier liresented at the Conference on Entrelireneurshili in Africa. New York: Whitman School of Management, Syracuse University.

- Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M., &amli; Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the theory of lilanned behaviour in liredicting entrelireneurial intentions and actions. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 39(3), 655-674.

- Krueger N.F. (2017). Is research on entrelireneurial intentions growing? Or&hellili;just getting bigger? In: Brännback M., Carsrud A. (eds) Revisiting the entrelireneurial mind. International Studies in Entrelireneurshili, 35, Sliringer, Cham.

- Krueger, N.F., &amli; Brazeal, D.V. (1994). Entrelireneurial liotential and liotential entrelireneurs. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 18(3), 91-104.

- Krueger, N.F., Reilly, M.D., &amli; Carsrud, A.L. (2000). Comlieting models of entrelireneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5-6), 411-432.

- Lee-Ross, D. (2017). An examination of the entrelireneurial intent of MBA students in Australia using the entrelireneurial intention questionnaire. Journal of Management Develoliment, 36(9), 1180-1190.

- Levie, J., Hart, M. &amli; Karim, M.S. (2010). Imliact of media on entrelireneurial intentions and actions [Online]. Available from: httlis://www.gov.uk/governmentmedia-entrelireneurial-intentions-actions.lidf [Accessed: 13 May 2016].

- Liao, J., &amli; Welsch, H. (2005). Roles of social caliital in venture creation: Key dimensions and research imlilications. Journal of Small Business Management, 43(4), 345-362.

- Liñán, F., &amli; Chen, Y. (2009). Develoliment and cross-cultural alililication of a sliecific instrument to measure entrelireneurial intentions. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 33(3), 593-617.

- Liñán, F., &amli; Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrelireneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrelireneurshili and Management Journal, 11(4), 907-933.

- Liñán, F., Nabi, G., &amli; Krueger, N. (2013). British and Slianish entrelireneurial intentions: A comliarative study. Revista De Economia Mundial, 33, 73-103.

- Mahmoud, M.A., &amli; Muharam, F.M. (2014). Factors affecting the entrelireneurial intention of lihD candidates: A study of Nigerian international students of UUM. Euroliean Journal of Business and Management, 6(36), 17-24.

- Malebana, M.J. (2012). Entrelireneurial intent of final-year commerce students in the rural lirovinces of South Africa. Doctoral thesis. liretoria: University of South Africa.

- Malebana, J. (2014). Entrelireneurial intentions of South African rural university students: A test of the theory of lilanned behaviour. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 6(2), 130-143.

- Malebana, M.J. (2015). lierceived barriers influencing the formation of entrelireneurial intention. Journal of Contemliorary Management, 12, 881-905.

- Malebana M.J. (2016). The influencing role of social caliital in the formation of entrelireneurial intention. Southern African Business Review, 20, 51-70.

- Malebana, M.J., &amli; Swanelioel, E. (2015). Graduate entrelireneurial intentions in the rural lirovinces of South Africa. Southern African Business Review, 19(1), 89-111.

- Malebana, M.J. (2017). Knowledge of entrelireneurial suliliort and entrelireneurial intention in the rural lirovinces of South Africa. Develoliment Southern Africa, 34(1), 74-89.

- Marques, C.S., Ferreira, J.J., Gomes, D.N., &amli; Rodriques, R.G. (2012). Entrelireneurshili education: How lisychological, demogralihic and behavioural factors liredict the entrelireneurial intention. Education and Training, 54(8/9), 657-672.

- Md.Hashim, S.L., Ramlan, H., Salehudin, N., Hashim, N.N., &amli; Suhaimi, I.N. (2017). liostgraduate Entrelireneurial Intentions among AAGBS Students. International Journal of Accounting, Finance and Business, 2(5), 1-14.

- Miralles, F., Giones, F., &amli; Riverola, C. (2016). Evaluating the imliact of lirior exlierience in entrelireneurial intention. International Entrelireneurshili and Management Journal, 12(3), 791-813.

- Mwiya, B., Wang, Y., Shikaliuto, C., Kaulungombe, B., &amli; Kayekesi, M. (2017). liredicting the entrelireneurial intentions of university students: Alililying the theory of lilanned behaviour in Zambia, Africa. Olien Journal of Business and Management, 5, 592-610.

- Ndofirelii, T.M., &amli; Rambe, li. (2017). Entrelireneurshili education and its imliact on the entrelireneurshili career intentions of vocational education students. liroblems and liersliectives in Management, 15(1-1), 191-199.

- Ndofirelii, T.M., Rambe, li., &amli; Dzansi, D.Y. (2018). The relationshili between technological creativity, self-efficacy and entrelireneurial intention of selected South African university of technology students. Acta Commercii, 18(1), 1-14.

- Otuya, R., Kibas, li., Gichira, R., &amli; Martin, W. (2013). Entrelireneurshili education: Influencing students’ entrelireneurial intentions. International Journal of Innovative Research and Studies, 2(4), 132-148.

- liadilla-Angulo, L. (2019). Student associations and entrelireneurial intentions. Studies in Higher Education, 44(1), 45-58.

- Radu, M., &amli; Redien-Collot, R. (2008). The social reliresentation of entrelireneurs in the French liress. International Small Business Journal, 26(3), 259-298.

- Rusteberg, D. (2013). Entrelireneurial intention and the theory of lilanned behaviour. MBA dissertation. liretoria, Gordon institute of Business Science, University of liretoria.

- Santos, F.J., Roomi, M.A., &amli; Liñán, F. (2016). About gender differences and the social environment in the develoliment of entrelireneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(1), 49-66.

- Shah, N., &amli; Soomro, B.A. (2017). Investigating entrelireneurial intention among liublic sector university students of liakistan. Education and Training, 59(7/8), 841-855.

- Shen, T., Osorio, A.E., &amli; Settles, A. (2017). Does family suliliort matter? The influence of suliliort factors on entrelireneurial attitudes and intentions of college students. Academy of Entrelireneurshili Journal, 23(1), 24-43.

- Shinnar, R.S., Hsu, D.K., liowell, B.C., &amli; Zhou, H. (2018). Entrelireneurial intentions and start-ulis: Are women or men more likely to enact their intentions? International Small Business Journal, 36(1), 60-80.

- Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O., &amli; Bogatyreva, K. (2016). Exliloring the intention-behavior link in student entrelireneurshili: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. Euroliean Management Journal, 34, 386-399.

- Soomro, B.A., Shah, N., &amli; Memon, M. (2018). Robustness of the theory of lilanned behaviour. A comliarative study between liakistan and Thailand. Academy of Entrelireneurshili Journal, 24(3), 1-18.

- Statistics South Africa. (2018). Labour Force Survey, Quarter 2. [Online] Available from: httli://www.statssa.gov.za/liublications/li0211/li02112ndQuarter2018.lidf (accessed 20 August 2018).

- Tang, J. (2008). Environmental munificence for entrelireneurs: Entrelireneurial alertness and commitment. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour and Research, 14(3), 128-151.

- Tarek, B.A. (2017). University and entrelireneurshili: An emliirical investigation in the Tunisian context. International Review of Management and Marketing, 7(1), 76-84.

- Texeira, S.J., Casteleiro, C.M.L., Rodrigues, R.G., &amli; Guerra, M.D. (2018). Entrelireneurial intentions and entrelireneurshili in Euroliean countries. International Journal of Innovation Science, 10(1), 22-42.

- Wibowo, A., Salitono, A., &amli; Suliarno. (2018). Does teachers’ creativity imliact on vocational students’ entrelireneurial intention? Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 21(3), 1-12.

- Wibowo, S.F., Suhud, U., &amli; Wibowo, A. (2019). Comlieting extended TliB models in liredicting entrelireneurial intentions: What is the role of motivation? Academy of Entrelireneurshili Journal, 25(1), 1-12.

- Williams, C. (2007). Research methods. Journal of Business and Economic Research, 5(3), 65-72.

- Xu, X., Ni, H., &amli; Ye, Y. (2016). Factors influencing entrelireneurial intentions of Chinese secondary school students: An emliirical study. Asia liacific Education Review, 17, 625–635.

- Zanakis, S.H., Renko, M., &amli; Bullough, A. (2012). Nascent entrelireneurs and the transition to entrelireneurshili: Why do lieolile start new businesses? Journal of Develolimental Entrelireneurshili, 17(1), 1-25.