Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 1S

Determinants of Corporate Disclosures: A Conceptual Model emanating from Political Economy Theory

W.A.N. Priyadarshanie, Graduate School of Management, Management & Science University, Malaysia

Siti Khalidah Binti Md Yusoff, Graduate School of Management, Management & Science University, Malaysia

S. M. Ferdous Azam, Graduate School of Management, Management & Science University, Malaysia

Citation Information: Priyadarshanie, W.A.N., Md Yusoff, S.K.B., & Azam, S.M.F. (2023). Determinants of corporate disclosures: a conceptual model emanating from political economy theory. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 27(S1), 1-15.

Abstract

Purpose: This paper aims to develop a conceptual framework based on the most commonly used theories in corporate disclosure literature to explain firms’ motives for disclosure decisions. Design / methodology/ approach: System-oriented theories namely, institutional theory, stakeholder theory and institutional theory are integrated into one model to explain the determinants of corporate disclosures. Thereby, variables were identified under each theory and indicators which can be used as the proxy for the variables were also recognized. Findings: Disclosure literature confirms that political economy theory is the most commonly used theory in explaining determinants of corporate disclosure level. Accordingly, Profitability, company age, firm size and media exposure can be used as the measures of corporate legitimacy. Shareholder power, creditor power and lobby group power were taken as the variables of stakeholder theory. Isomorphism which is the practice of adopting similar practices is considered under the institutional theory. Coercive isomorphism, mimetic isomorphism, and normative isomorphism are three separate isomorphic processes and indicators were recognized for each isomorphism. Research limitations/ implications: The main limitation of this study is that this conceptual framework has included only the political economy theory. Other important theories such as agency theory, signaling theory, resource dependency theory, media agenda-setting theory may be used to explain corporate disclosure practices. Practical implications: This conceptual framework can be employed in empirical studies on the motivations for corporate disclosure behaviors in a variety of settings. The predicted disclosure motivates can be compared to empirical evidence of those studies. Findings obtained by utilizing this conceptual framework will help to evaluate which companies report? Under which context, in which sectors and of which size? And it answered whether there is uniform reporting across industries. Those findings will help regulators to establish a code of practice for disclosing information which leads to a better practice of reporting. Originality / Value: This paper has presented a conceptual model for determinants of corporate disclosures which is not discussed elsewhere in the literature.

Keywords

Corporate Disclosures, Legitimacy Theory, Stakeholder Theory, Institutional Theory, Conceptual Model.

Introduction

The main issue with corporates is the information asymmetry between managers and shareholders (Ho & Taylor, 2013). Managers use the corporate annual report to fill this informational gap. According to the findings of annual reports are the most important source of company information. Although in the beginning, the main focus was given to the shareholders, gradually identified that other stakeholders are also important and provide information which they are interested in. Thereby, the size of the annual reports is regularly increased over the years. However, companies in several countries have complained that their annual reports contain too much information KPMG 2016. According to the survey done by KPMG in 2016, the content of the annual reports shows an annual increase of 3%. Although growth in report length can often be tied to new or increased regulatory disclosure requirements, companies are also being challenged to voluntarily disclose their contribution to society Harvey. Qu (2011) found that voluntary disclosure made by firms was increased over the years. However, Deloitte claimed that the increasing complexity of regulations is the main reason for lengthy annual reports. At the same time, Morunga & Bradbury revealed that the increase in annual report size was due to the financials section of the report. It seems that pressure from regulators is always to add more, rather than to remove, disclosure (?ener, 2016).

Many companies have expressed frustration with the apparent ever-increasing volume of financial and non-financial information they are required to disclose as a result of regulations KPMG. European Union (2021) identified that the large and increasing number of reporting requirements and frameworks, together with their heterogeneity (in scope, objective, implementation – voluntary or mandatory, technology, etc.), are a source of numerous inconsistencies in reporting practices. Too many disclosures that are not relevant, making it difficult for preparers to effectively communicate through reports. This is not simply a matter of the cost of providing the information, but the possibility of data overload. This will ultimately lead to failing to address the users’ needs while being a burden for preparers of non-financial information, whose specificities and capacities (from large companies to small and medium entities) are not sufficiently considered (European Union, 2021). Kamal (2021) discovered that there is an apparent disconnection between stakeholder expectations and corporate disclosures. Andrades et al. (2020) also identified that the amount of corporate governance information disclosed by Spanish universities is far from being adequate and does not meet the stakeholders’ demands. In 2013, International Accounting Standard Board (IASB) identified that there is a problem with information overload and not enough relevant information. Information overload has become an alarming issue.

Both users and preparers are facing the problem of information overload. Investors are also confused as they struggle to find the relevant data to incorporate into their decision-making. Thereby, data overload will be an important issue to be considered in the future and it will impact decision outcomes which may lead to inefficient capital allocation (Agnew & Szykman, 2005). The importance of annual reports may also deteriorate and will lead to not reading annual reports (García-Ayuso & Larrinaga, 2003).

In June 2017, the European Commission provided Guidelines on non-financial reporting to help companies disclose relevant non-financial information more consistently and comparably (European Union, 2020). Regulations for corporate disclosures in other countries should also be established by carefully examining the current situation of reporting practice. Content, classification and reporting format of current reporting practice should be evaluated to provide technical advice for possible future non-financial reporting standard setters (European Union, 2021).

Then, this study provides a conceptual framework to examine the determinants of corporate disclosures under political economy theory. It helps to get an idea about which factors have influenced the current reporting practice by responding to which companies report, under which context, in which sectors and of which size? Is there uniform reporting across industries? Many researchers (Khlif & Souissi, 2010; Betah, 2013; Lan et al., 2013) have conducted studies to investigate the factors which are affecting the level of corporate disclosures. Researchers have used diverse theoretical perspectives to explain the level of corporate disclosures. The purpose of this study is to develop a conceptual framework for determinants of corporate disclosures by critically reviewing the studies which are conducted under political economy theory. Three system-oriented theories (Political economy theory) namely legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory and institutional theory are widely used in corporate disclosure studies and they are mostly used individually (Fernando & Lawrence, 2014). To obtain a fuller understanding of and deep insights into organizations’ disclosure behavior, an outcome which might not be achieved by a single theory alone. Therefore, in this framework, all the sub-theories of the political economy theory are included (Liani, 2015).

Within corporate disclosure literature, researchers have identified key disclosure categories. They are corporate disclosure in financial statements, voluntary disclosure, social and environmental reporting. In addition to that biodiversity reporting, anti-corruption disclosure, political donation disclosure, Greenhouse gas emissions are also examined in some studies. The political economy theory provides explanations for non-financial disclosures as well as voluntary financial disclosures (Deegan, 2014). Hence, all of the above disclosures are covered under this proposed model. Therefore, the proposed model will able to be employed in empirical studies which examine the determinants of corporate disclosures in a variety of settings. The findings will help regulators to have a comprehensive impression of the current reporting practice (Nyahas, 2017).

Theoretical and Empirical Gap

This study is looking at the supply side of the corporate disclosures. Determinants of corporate disclosures which are based on three accounting theories under political economy theory namely, stakeholder, legitimacy and institutional theory are examined in the study. Although previous studies (Nyahas et al., 2017) look at those theories individually, this study provides a framework that enables consideration of all sub-theories of political economy theory, together in one study. Thereby, the findings of the study will fill the theoretical gap. No evidence of findings that have used these three theories in examining motives behind corporate disclosures. Thereby, applying this conceptual framework will provide empirical shreds of evidence for determinants of corporate disclosures by filling the empirical gap (La Torre et al., 2020).

Theoretical Review

The political economy theory is the main theory utilized in developing this conceptual framework. According to this theory, society, politics and economics are inseparable, and economic issues cannot be meaningfully investigated in the absence of considerations about the political, social and institutional framework in which the economic activity takes place. By considering the political economy, a researcher can consider broader issues that impact how an organization operates and what information it elects to disclose (Deegan, 2014).

Political Economy Theory

Corporate disclosure researches are conducted their studies based on several theories. Among them agency theory, legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory and institutional theory are prominent. This study is based on the Political Economy Theory which is generally used to explain non-financial disclosures rather than financial disclosures. Consequently, Legitimacy theory, Stakeholder theory and Institutional theory are considered. Gray et al. (1996) defined political economy as “the social, political and economic framework within which human life takes place”. According to this theory, it is unable to separate society, politics and the economy. Hence, all of those aspects should be considered when investigating an economic issue. Thereby, corporate reports assist in creating, maintaining and legitimizing economic and political arrangements, institutions and ideological themes that contribute to the private interests of the company. Hence, those corporate reports are apparent as social, political and economic documents (Guthrie & Parker, 1990). By considering the political economy, a researcher can consider a wide range of factors that affect how an organization operates and the information it chooses to disclose (Deegan, 2014).

Political Economy Theory is divided into two streams, like ‘Classical’ and ‘Bourgeois’ (Gray et al., 2009). According to Classical Political Economy Theory, accounting and disclosures are about maintaining an advantageous position of those who control scarce resources and undermining the status of those who do not have scarce resources. It focuses on structural conflicts in society. Therefore, disclosures about environmental and social impacts are considered less useful without a real change in the structure of society. Otherwise, such disclosures will help the resource owners to maintain their compensations and the real change in society will not take place (Lê & L?u, 2017).

Bourgeois Political Economy Theory considers the interactions between groups in an essentially pluralistic society. Legitimacy Theory and Stakeholder Theory are derived from Bourgeois Political Economy Theory. However, Institutional Theory can be applied within either a Classical or a Bourgeois conception of Political Economy Theory (Deegan, 2014).

These three theories are also known as system orientation theories (open system theories) (Deegan, 2014). A system-oriented perspective on organization and society allows us to focus on the role of information and disclosure in the relationship between organizations, government, individuals and groups (Gray et al., 1996).

The system-based perspective assumes that an organization has an impact on the society in which it operates. According to Deegan (2014) legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory and institutional theory are often used to explain managers' motives for making non - financial disclosures, they can also be used to explain voluntary financial disclosures. These three theoretical perspectives have been adopted by some researchers in recent years (Nyahas et al., 2017; Amran & Haniffa, 2011; Setyorini & Ishak, 2012; Qu et al., 2013; Mohamad et al., 2013). Ji & Deegan (2013) stated that the legitimacy theory is the most widely used in the social and environmental accounting literature in recent years, and however, the institutional theory is increasingly being applied in the same field of literature.

Legitimacy Theory

Organizations must constantly attempt to guarantee, that they function within the bounds and norms of their particular societies to legitimize their existence (Deegan, 2014). It gives an organization the right to carry out its operations following the interests of society. As a result, corporations strive to operate following the norms and ambitions of their respective societies. If an organization fails to follow societal standards, society may apply sanctions in the form of legal restrictions on its activities, resource restrictions, and even a reduction in demand for its products. Organizational legitimacy is critical to its survival. Thereby, organizations should pursue strategies to maintain legitimacy to assure a steady flow of resources.

Legitimacy is better achieved through governance disclosures as general corporate social responsibility disclosures often seem as symbolic and provide an immediate response to stakeholders’ pressure (Kamal, 2021). O'Dwyer also claimed that corporate social disclosures can play a role in the legitimacy process. The findings of O'Donovan's (2002) study back up legitimacy theory as an explanation for environmental disclosures. Muttakin et al. (2018) also identified the perceived need for CSR disclosures as a legitimation strategy for politically connected firms.

Researchers who examine the impact of legitimacy theory on corporate disclosures have used several indicators as measures of corporate legitimacy. Among them, the most prominent factors i.e. Profitability, operational leverage, company age, firm size, and media exposure/ coverage have been considered in the proposed model.

Profitability

One of the factors that have been widely used in the literature to explain the level of corporate disclosure is profitability (Naser & Hassan, 2013). According to the legitimacy theory, profitability can be viewed as either positive or negative to corporate disclosures (Neu et al. 1998). Profitable companies have positive messages to send to the users of business information. On the other hand, some companies are sustaining losses and still disclosing detailed information to explain what went wrong and how they intend to correct it. Thereby, the empirical studies focusing on the relationship between disclosures and profitability provided mixed results. Researchers (Mirza et al., 2017; Bhayani, 2012; Naser & Hassan, 2013) found a positive relationship between profitability and disclosures while Reverte (2009) identified no significant relationship between profitability and disclosures. Researchers have used different measures such as ROE, ROA, net income to sales, earnings to sales, operating profit to total asset, profit margin, return on capital employed as a proxy for profitability.

Company Age

According to legitimacy theory, companies having a longer societal presence may have taken on more legitimacy. As a corporation becomes older, it will require more information from society. The longer a firm has been listed on the stock exchange, the more probable it is to disclose more information, as voluntary disclosure is a tactic that management can actively adapt to combat public pressure. Zhang (2013) found that there is a significant positive relationship between company age and corporate environmental and social disclosures. Mirza et al. (2017) found that company age is positively related to the level of voluntary disclosures. However, Bhayani (2012) identified that company age does not influence the level of corporate disclosure.

Firm Size

Several studies (Naser & Hassan, 2013; Othman et al., 2009; Tagesson et al., 2009; Hackston & Milne, 1996) looked at the association between corporate disclosures and firm size. Large corporations are expected to have greater financial and human resources than small businesses to compile, evaluate, and publish information. Because of economies of scale, the cost of preparing information is falling for such businesses. Large corporations are subjected to scrutiny by the general public as well. These businesses are more visible and thus more subject to adverse reactions. As a result, they tend to provide more information than small businesses to guarantee the public and reduce political costs. Large organizations also tend to voluntarily disclose more information to reduce conflicts between management and stakeholders (Naser & Hassan, 2013). Bhayani (2012) also claimed that large companies have tendencies to be more transparent and hence disclose more information. Empirical studies confirm that firm size influences the amount of social and environmental disclosures (Cormier & Gordon, 2001; Hackston & Milne,1996) and voluntary disclosures (Barako et al., 2006; Mirza, 2017; Lan et al., 2013). Tan et al. (2016) concluded that firm size has a significant effect on CSR disclosure. Hau & Danh found there is a positive influence of firm size on disclosures in financial statements.

Tagesson et al. (2009) used the number of employees as a measure for firm size. The majority of researchers (Naser & Hassan, 2013; Othman et al., 2009; Hossain & Hammami, 2009) used total assets as a proxy for firm size. The total sale is considered by Dyduch & Krasodomska (2017) as a measure for firm size. Andrades et al. (2020) also identified that institute size is one of the most influential variables associated with better disclosure levels of corporate governance information. Andrades Pena and Jorge recognized that the institutional size was the variable that most significantly affects the disclosure of mandatory non-financial information by Spanish state-owned enterprises.

Media Exposure

Media attention raises a company's visibility, attracting more public scrutiny (Reverte, 2009). Empirical studies have demonstrated that the media has a strong influence on corporate disclosures. Michelon discovered a relationship between media exposure and sustainability disclosure. According to Magness companies who keep themselves in the public view by issuing press releases give more information than other companies. Reverte (2009) identified that firms with higher corporate social responsibility ratings present a statistically significant higher media exposure. Lock (2018) identified that media coverage is positively associated with voluntary disclosures.

Stakeholder Theory

Stakeholder theory focuses on how businesses interact with their stakeholders (Deegan, 2014). Stakeholder theory, as articulated by Sternberg, states that businesses should be managed for the benefit of all stakeholders, rather than for the financial benefit of their owners. Furthermore, firms are responsible to all of their stakeholders, and management's primary goal should be to balance opposing stakeholder interests. Because there are a variety of stakeholder groups with varying and sometimes competing expectations (Fernando & Lawrence, 2014).

Managers dispute whether corporations should give equal attention to all stakeholders as a moral obligation or focus on a certain subset of stakeholders. As a result of this dispute, two branches of stakeholder theory have emerged (normative or ethical and managerial or positive branch).

The Ethical Branch of Stakeholder Theory

The moral or ethical (normative) perspective of stakeholder theory asserts that all stakeholders have the right to be treated equitably by an organization and that stakeholder power is irrelevant (Deegan, 2014). According to Freeman (1984), management has a fiduciary connection with all stakeholders and should attempt to treat each stakeholder equally as an ethical obligation for the optimal benefit of the firm and stakeholders' best interests.

According to this ethical branch of stakeholder theory, stakeholders have inherent rights and these rights should not be violated (Deegan, 2014. All stakeholders have a legal right to know how the organization affects them. As a result, all disclosures should be provided to be accountable to all of the interest groups. Consequently, the purpose of a corporate report is to inform society about the extent to which an organization's responsibilities have been met (Peña & Jorge, 2019).

The Managerial Branch of Stakeholder Theory

On the other hand, the management branch believes that, given resource and time constraints, managers are unable to satisfy the demands of all the stakeholders. Stakeholder theory from this perspective addresses the various stakeholder groups in society and how they should be managed for the organization's survival. The expectations of various stakeholder groups are seen to have an impact on the organization's operating and disclosure policies, similar to legitimacy theory. The organization will not respond to all stakeholders in the same way, but rather to those that are judged to be influential (Deegan, 2014). The ability of a stakeholder to influence corporate management is considered a function of the stakeholder's degree of control over the organization's resources (Ullman, 1985). The higher the importance of a stakeholder's resources to the organization's future sustainability and performance, the greater the expectation that the stakeholder's demand will be met.

The management branch of stakeholder theory assumes that the expectations of various stakeholder groups will have an impact on the organization's operating and disclosure practices (Deegan, 2014). Disclosing information is a key component that a company can use to manage stakeholders, either to gain their support and acceptance or to divert their resistance and dissatisfaction (Gray et al., 1996). Stakeholder groups that control vital resources that the firm needs to survive are likely to have their information demands met by firms. In this regard, corporations' levels of corporate disclosure to meet stakeholder needs differ depending on management's judgment of which stakeholder group is crucial to the firm's goal achievement. Thoradeniya et al. (2015) identified that managers’ attitude towards stakeholder pressure and their capacity to control sustainability reporting behavior influence their intention to engage in sustainability reporting. Kamal (2021) observed that powerful stakeholders receive their required governance information from an alternative media (social audit report) that less powerful stakeholders cannot access within the garments and textile companies of Bangladesh. Together, external stakeholder pressure is a contributing factor for the existence of greenhouse gas emissions disclosures (Liesen et al., 2015). The power of shareholders, creditors, and lobby groups has been utilized as a proxy for the power of stakeholders by researchers.

Shareholder Power

Sener et al. (2016) found that the shareholders are the most salient stakeholder influencing sustainability reports disclosures. Wilmshurst & Frost Researchers have used ownership consideration as the proxy for shareholder power. Different researchers have used various methods to measure ownership concentration. Kent & Chan (2009) and Roberts (1992) measured stakeholder power by using the percentage of shares of the company owned by shareholders owning more than 5% of the outstanding shares. Lu & Abeysekara (2014) has taken a percentage of shares owned by the largest shareholder at the end of the year to measure shareholder power. Roberts (1992) concluded that stockholder power does not support the proposition that widespread stock ownership increases corporate incentives to make social responsibility disclosures.

Creditor Power

Many researchers (Roberts, 1992; Kent & Chan, 2009; Betah, 2013; Lu & Abeysekera, 2014) used financial leverage to measure creditor power. Betah (2013) discovered that leverage positively impacts the level of corporate disclosure and transparency of listed companies in Zimbabwe during the financial crisis period 2007 – 2008. Lu & Abeysekera (2014) measured creditor power using debt to total asset ratio. Kent & Chan (2009) and Roberts (1992) have used the debt to equity ratio as a measure for financial leverage.

Lobby Group Power

Lobby groups pay more attention to industries that are highly sensitive to the environment. As a result, the industry in which a corporation works is an indirect measure of lobbying influence (Deegan and Gordon, 1996). Management is enticed to make disclosures by the perception of increased scrutiny from lobbying groups. This suggests that businesses in environmentally sensitive industries are more likely to make better disclosures than businesses in less environmentally sensitive industries. Empirical studies have found there is a positive impact of industry environmental sensitivity on CSR disclosures (Dyduch & Krasodomska, 2017; Tan et al., 2016; Ali et al., 2017; Kansal et al., 2014), environmental disclosures (Ayuso & Larrinaga, 2003; Hackston & Milne, 1996).

Institutional Theory

The institutional theory examines the different forms that organizations adopt and explains why organizations in the same field tend to have similar characteristics and structures. According to institutional theory, organizations are viewed as working within a social framework of conventions, values, and implicit assumptions about what constitutes suitable or acceptable economic behavior (Deegan, 2014). Institutional theory has two basic dimensions: isomorphism, which refers to an organization's adaption of institutional practice, and decoupling, which refers to actual or factual organizational practices differing from institutionalized or obvious practices. Both of these are important to understand when it comes to voluntary corporate reporting.

Isomorphism is the practice of adopting similar practices (DiMaggio & Powel, 1983). Coercive isomorphism, mimetic isomorphism, and normative isomorphism are three separate isomorphic processes (DiMaggio & Powel, 1983). All three types of isomorphism are linked to corporate disclosures (Depoers & Jerome, 2019).

Coercive Influences and Corporate Disclosure

Coercive isomorphism occurs when an organization's institutional processes change as a result of pressure from stakeholders on whom the organization depends. It is a result of both official and informal pressures placed on organizations by other organizations on which they rely, as well as cultural expectations in the society in which they operate. Coercive pressures are also arising from the firm's legal and contractual environment (Scott, 2001). Such pressures may be seen as force, persuasion, or encouragement to collaborate (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). It requires organizations to adjust their institutional procedures in response to both official and informal demands from those stakeholders. Regulations and pressures from various socio-economic-political institutions are examples of coercive processes. Firms employ corporate reporting to address the economic, social, environmental, and ethical principles and concerns of the company's most powerful stakeholders. According to Qu et al. (2012), Chinese companies respond to coercive pressure by strengthening their voluntary disclosure procedures. In this context, government shareholding, foreign share ownership, government contract and the number of foreign business associates can be considered as measures of coercive isomorphism (Ullmann, 1985).

Mimetic Influences and Corporate Disclosure

Mimetic isomorphism refers to the practice of companies emulating or improving on the institutional practices of other organizations, which may be to gain a competitive edge in terms of legitimacy (Deegan, 2007). Mimetic isomorphism is generated by environmental uncertainties, for example, the regulator does not clarify the disclosure that must be communicated by companies. Setyorini & Ishak (2012) found that under uncertainty of government tools for corporate social and environmental reporting, companies in Indonesia tend to similar or mimic performance, structure and practices of other companies. Moreover, Pfarrer et al. (2005) found that firms voluntarily restate their earnings when industry peers did so in the past. Membership of an industrial association and the number of awards won can be considered as measures for mimetic influences (Trevor & Geoffrey, 2000).

Normative Influences and Corporate Disclosure

The ultimate isomorphic phase is a normative isomorphism, which is linked to demands from group norms to embrace specific institutional procedures or meet professional expectations (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Professional or industrial networks generate a set of norms, shared values, and standards that lead to creating normative influences. This is the urge to adopt specific institutional procedures as a result of group norms. In the case of corporate disclosures, the professional expectation that accountants will adhere to accounting standards and other reporting regulations operates as a sort of normative isomorphism (Deegan, 2012). Nyahas et al. (2017) found that normative isomorphic mechanisms are positively associated with voluntary disclosure. Managing director’s membership in a professional body, being a subsidiary or associate of a parent, managing director’s foreign experience, managing director’s foreign education and type of audit firm could be considered as proxies for normative influences.

Construction of The Conceptual Framework

To construct the conceptual framework based on the aforementioned theories it is necessary to identify the relationship between these three theories as a basis for explaining corporate disclosures. Legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory and institutional theory are often used to explain managers’ motivations to make non-financial disclosures, and they could also be used to explain voluntary financial disclosures (Deegan, 2014). Stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory are multi-faceted and interrelated theoretical perspectives. There are many similarities between legitimacy theory and stakeholder theory. As such, treat them as two distinct theories would be incorrect. Both theories conceptualize the organization as part of a broader social system wherein the organization impacts on and are affected by, other groups within society. Legitimacy theory relies on the assumption that there is a social contract between the organization and the society in which it operates (Deegan, 2014). However, while legitimacy theory discusses the expectations of society in general, stakeholder theory provides a more refined resolution by referring to particular groups within society. Stakeholder theory focuses on how an organization interacts with particular stakeholders, while legitimacy theory considers interactions with society as a whole (Deegan, 2014). However, legitimacy theory is about managers’ perceptions rather than accountability to stakeholders Laan. Legitimacy theory and stakeholder theory are largely overlapping theories that provide consistent but slightly different insights into the factors that motivate managerial behavior (O’Donovan, 2002). A consideration of both theories is deemed to provide a fuller explanation of management’s actions. The different theoretical perspectives need not be seen as competitors for the explanation but as sources of interpretation of different factors at different levels of resolution. In this sense, legitimacy theory and stakeholder theory enrich, rather than compete for, understanding of corporate disclosure practices (Deegan, 2014).

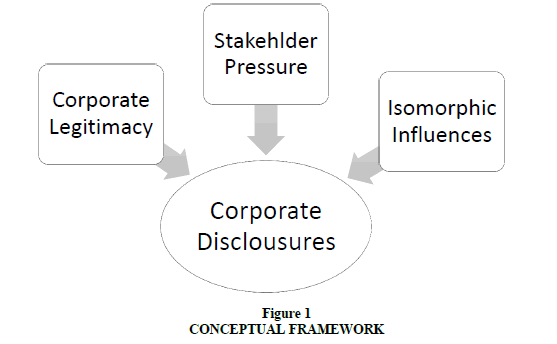

Legitimacy theory is also relevant to investigate corporate disclosure practices since it provides a complementary perspective to both stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory in understanding how organizations understand and respond to changing social and institutional pressures and expectations. This theory links organizational practices such as corporate reporting to the values of the society in which an organization operates and to a need to maintain organizational legitimacy. The structure of the organization and the practices adopted by different organizations tend to become similar to conform to what society considers to be normal. This process of institutionalization is also a process of homogenization which is referred to as isomorphism. Organizations that deviate from being of a form that has become normal will potentially have problems in gaining or retaining legitimacy. The institutional theory, therefore, explains how mechanisms through which organizations may seek to align perceptions of their practices and characteristics with social and cultural values become institutionalized in particular organizations. Such mechanisms could include those proposed by both stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory, but could conceivably also encompass a broader range of legitimating mechanisms. Therefore, these three theoretical perspectives should be seen as complementary rather than competing (Deegan, 2014). According to the discussion, the conceptual model in Figure 1 is proposed to evaluate the corporate disclosure decisions of firms.

Based on the empirical studies which were discussed in the previous sections, some scales were identified to measure the corporate legitimacy, stakeholder pressure, and isomorphic influences. Based on these scales, this study identifies measurements for each theory and provides the operational definition for each measurement in Table 1.

| Table 1 Operationalization Of Variables |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Measures | Definition | Previous Studies |

| Corporate Legitimacy | Profitability | Return on Assets (ROA) = Net profit / Total Assets | Zhang (2013), Ayuso & Larrinaga (2003) |

| Firm size | Natural log value of total assets | Ayuso & Larrinaga (2003), Cormier & Gordon (2001) | |

| Media exposure/ coverage | Number of newspaper article | Ayuso & Larrinaga (2003) | |

| Company Age | Number of years from listing in a stock exchange | Masum et al. (2020) | |

| Isomorphic Influences | Government Shareholding | Percentage of shares held by the government | Depoers & Jerome (2019) |

| Coercive | Foreign Share Ownership | Percentage of the shares held by non-residence | Depoers & Jerome (2019) |

| Government contract | Number of contracts with the government | Depoers & Jerome (2019) | |

| Foreign business associates | Number of foreign business associates | Depoers & Jerome (2019) | |

| Membership of an Industrial Association | Number of memberships in industrial associations | Depoers & Jerome (2019) | |

| Mimetic | Awards winning | Number of awards won | Depoers & Jerome (2019) |

| Managing director’s membership in a professional body | If the managing director is a member of a professional body – 1, if not 0. | Depoers & Jerome (2019) | |

| Normative | Subsidiary or associate of a parent | If the company is a subsidiary or associate of another company – 1, if not 0. | Depoers & Jerome (2019) |

| Managing director’s foreign experience | If the managing director has foreign experience – 1, if not 0. | Depoers & Jerome (2019) | |

| Managing director’s foreign education | If the managing director has foreign education – 1, if not 0. | Depoers & Jerome (2019) | |

| Type of Audit firm | If audit firm is one of the big 4 – 1, if not 0. | Depoers & Jerome (2019) | |

| Shareholder power | Ownership Concentration - Percentage of shares of the company owned by shareholders owning more than 5% of the outstanding shares | Qu et al. (2013) | |

| Stakeholder Pressure | Creditor Power | Debt to equity ratio = Total Debt / Total equity | Qu et al. (2013) |

| Lobby Group power | Industry Type (Dummy Variable) - If the industry is environmentally sensitive – 1, otherwise 0. | Qu et al. (2013) | |

Discussion

The conceptual framework presented in this paper has been developed from empirically-based research and extensive research of the literature. This conceptual framework resultant three convergent motivations of corporate disclosure practice: first, the desire to legitimize the business activities; second, the aspiration to accomplish responsibility to stakeholders of the business and third the desire to conform to industry norms, rules and regulations that are largely imposed on an organization, and which ultimately leads to homogeneity in organizations in the same field. This framework contributes to the corporate disclosure literature by providing a quantitative research tool for the analysis of determinants of corporate disclosures. This conceptual framework can be employed in empirical studies on the motivations for corporate disclosure behaviors in a variety of settings such as listed companies, non-listed public companies and small and medium-sized businesses. The aforementioned theoretically predicted disclosure motivations can be compared to empirical evidence from disclosure research. For example, disclosure practices in a given context can be investigated to see if they contradict these predictions and to discover what could be lean from those practices beyond these theoretical approaches.

Conclusion

This paper aimed to identify a conceptual model to capture the causal factors of corporate disclosures based on political economy theory. Corporate disclosure can be explained by joint consideration of legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory and institutional theory which are the sub-theories of political economy theory. By taking a more contextuAlized view of corporate reporting and by analyzing the literature of legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory and institutional theory, this article has sought to integrate these three political economy theories into the wider conceptual base and frameworks in the study of determinants of corporate disclosure decisions. This model needs further testing in a range of different contexts. Findings obtained by utilizing this conceptual framework will help to evaluate which companies report? Under which context, in which sectors and of which size? And it answered whether there is uniform reporting across industries. Those findings will help regulators to establish a code of practice for disclosing information which leads to a better practice of reporting.

The main limitation of this study is this framework has included only the system-oriented theories. Some other important theories such as agency theory, signaling theory, resource dependency theory, media agenda-setting theory may be used to explain corporate disclosure practices. Of course, seeking explanations for managerial motivation to disclose information is a study in human behavior and no one theory can ever completely explain definitive decision-making processes as theories are abstractions of reality and particular theories cannot completely account for or describe particular behavior (Deegan, 2000). It would be useful to develop this framework by adding other relevant theories of corporate disclosures. It is proposed to use this conceptual model to analyze the views of managers who are responsible for corporate disclosure decisions and at the same time, it would be useful to develop the same model into the qualitative analysis. This aspect should be considered as it may inform researchers as to the behavior associated with corporate disclosures.

References

Ali, W., Frynas, J.G., & Mahmood, Z. (2017). Determinants of corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in developed and developing countries: A literature review. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 24(4), 273-294.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Amran, A., & Haniffa, R. (2011). Evidence in development of sustainability reporting: a case of a developing country. Business Strategy and the Environment, 20(3), 141-156.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Andrades, J., Martinez-Martinez, D., & Larrán Jorge, M. (2020). Corporate governance disclosures by Spanish universities: how different variables can affect the level of such disclosures? Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(1), 86–109.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Barako, D.G., Hancock, P., & Izan, H.Y. (2006). Factors influencing voluntary corporate disclosure by Kenyan companies. Corporate Governance: an international review, 14(2), 107-125.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Betah, T. (2013). An investigation into determinants of corporate disclosure & transparency of listed companies in Zimbabwe during financial crisis (2007-2008). International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 2(1), 19-25.

Bhayani, S. (2012, January). Association between firm-specific characteristics and corporate disclosure: The case of India. In International Conference on Business, Economics, Management and Behavioral Sciences (pp. 479-482).

Cormier, D., & Gordon, I.M. (2001). An examination of social and environmental reporting strategies. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal.

Deegan, C., & Gordon, B. (1996). A study of the environmental disclosure practices of Australian corporations. Accounting and business research, 26(3), 187-199.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Deegan, C. (2014). Financial accounting theory. London: McGraw-Hill.

Deegan, C. (2010). Organizational legitimacy as a motive for sustainability reporting. In Sustainability accounting and accountability (pp. 146-168). Routledge.

Depoers, F., & Jérôme, T. (2020). Coercive, normative, and mimetic isomorphisms as drivers of corporate tax disclosure: The case of the tax reconciliation. Journal of applied accounting research.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

DiMaggio, P.J. & Powell, W.W. (1983). The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147 – 160.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dyduch, J., & Krasodomska, J. (2017). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An empirical study of Polish listed companies. Sustainability, 9(11), 1934.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

European Union (2021). Current Non-Financial Reporting Formats and Practices. European Reporting Lab.

Fernando, S., & Lawrence, S. (2014). A theoretical framework for CSR practices: Integrating legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory and institutional theory. Journal of Theoretical Accounting Research, 10(1), 149-178.

Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach (Marshall, MA/Pitman). ISBN-10, 521151740.

Gray, R., Owen, D., & Adams, C. (1996). Accounting & accountability: changes and challenges in corporate social and environmental reporting. Prentice hall.

García-Ayuso, M., & Larrinaga, C. (2003). Environmental disclosure in Spain: Corporate characteristics and media exposure. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting/Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad, 32(115), 184-214.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gray, R., Owen, D., & Adams, C. (2009). Some theories for social accounting?: A review essay and a tentative pedagogic categorisation of theorisations around social accounting. In Sustainability, environmental performance and disclosures. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Guthrie, J., & Parker, L.D. (1990). Corporate social disclosure practice: a comparative international analysis. Advances in public interest accounting, 3, 159-175.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hackston, D., & Milne, M.J. (1996). Some determinants of social and environmental disclosures in New Zealand companies. Accounting, auditing & accountability journal.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ho, P.L., & Taylor, G. (2013). Corporate governance and different types of voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Malaysian listed firms. Pacific Accounting Review, 25(1), 4-29.

Hossain, M., & Hammami, H. (2009). Voluntary disclosure in the annual reports of an emerging country: The case of Qatar. Advances in Accounting, 25(2), 255-265.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ji, S., & C. Deegan (2013), The origin, use and contribution of legitimacy theory to social and environmental accounting research, working paper, Melbourne: School of Accounting, RMIT University

Kamal, Y. (2021). Stakeholders expectations for CSR-related corporate governance disclosure: evidence from a developing country. Asian Review of Accounting.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kansal, M., Joshi, M., & Batra, G.S. (2014). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from India. Advances in Accounting, 30(1), 217-229.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kent, P., & Chan, C. (2009). Application of stakeholder theory to corporate environmental disclosures. Corporate Ownership and Control, 7(1-3), 394-410.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Khlif, H., & Souissi, M. (2010). The determinants of corporate disclosure: a meta?analysis. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lê, L.H., & L?u, C.D. (2017). Determinants of Corporate Disclosure in Financial Statements: Evidence from Vietnamese Listed Firms. International Journal of Advanced Engineering, Management and Science. 3(5), 474-480.

La Torre, M., Sabelfeld, S., Blomkvist, M., & Dumay, J. (2020). Rebuilding trust: Sustainability and non-financial reporting and the European Union regulation. Meditari Accountancy Research, 28(5), 701-725.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Liani, W. (2015). The effect of firm size, media exposure and industry sensitivity to corporate social responsibility disclosure and its impact on investor reaction. International Conference on Accounting Studies (ICAS) 2015.

Lan, Y., Wang, L. & Zhang, X. (2013). Determinants and features of voluntary disclosure in the Chinese stock market. China Journal of Accounting Research, 6, 265 – 285.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lock, B.M. (2018). The impact of media coverage on voluntary disclosure (Doctoral dissertation, Northwestern University).

Lu, Y., & Abeysekera, I. (2014). Stakeholders' power, corporate characteristics, and social and environmental disclosure: evidence from China. Journal of cleaner production, 64, 426-436.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mirza, H. H., Muneeb, K. F., & Ashghar, M. J. E. K. A. (2017). Determinants of Voluntary Disclosure in Non-Financial Listed Companies of Pakistan. South Asian Journal of Banking and Social Sciences, July.

Mohamad, Z.Z., Salleh, H.M., & Chek, I.T. Stakeholder Influence on the Quality of Non-Financial Information Disclosure in Five Malaysian Sectors. International Journal of Arts and Commerce, 2(10), 93-102.

Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Muttakin, M.B., Mihret, D.G., & Khan, A. (2018). Corporate political connection and corporate social responsibility disclosures: A neo-pluralist hypothesis and empirical evidence. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal. 31(20), 725-744

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Naser, K. & Hassan, Y. (2013). Determinants of corporate social responsibility reporting: evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of contemporary issues in business research, 2 (3), 56 -74.

Neu, D., Warsame, H., & Pedwell, K. (1998). Managing public impressions: environmental disclosures in annual reports. Accounting, organizations and society, 23(3), 265-282.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Iliya Nyahas, S., Munene, J.C., Orobia, L., & Kigongo Kaawaase, T. (2017). Isomorphic influences and voluntary disclosure: The mediating role of organizational culture. Cogent Business & Management, 4(1), 1351144.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

O’donovan, G. (2002). Environmental disclosures in the annual report: Extending the applicability and predictive power of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15(3), 344-371.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Othman, R., Thani, A.M., & Ghani, E.K. (2009). Determinants of Islamic social reporting among top Shariah-approved companies in Bursa Malaysia. Research Journal of International Studies, 12(12), 4-20.

Peña, J.A., & Jorge, M.L. (2019). Examining the amount of mandatory non-financial information disclosed by Spanish state-owned enterprises and its potential influential variables. Meditari Accountancy Research.

Pfarrer, M.D., Smith, K.G., Bartol, K.M., Khanin, D.M., & Zhang, X. I.A.O.M.E.N.G. (2005). Coming forward: Institutional influences on voluntary disclosure. Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland.

Qu, W., Leung, P., & Cooper, B. (2013). A study of voluntary disclosure of listed Chinese firms–a stakeholder perspective. Managerial Auditing Journal. 28(3)

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Reverte, C. (2009). Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure Ratings by Spanish Listed Firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 88, 351–366.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Roberts, R.W. (1992). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An application of stakeholder theory. Accounting, organizations and society, 17(6), 595-612.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

?ener, ?., Varo?lu, A., & Karapolatgil, A.A. (2016). Sustainability reports disclosures: who are the most salient stakeholders?. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 235, 84-92.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Setyorini, C.T., & Ishak, Z. (2012). Corporate social and environmental disclosure: a positive accounting theory view point. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(9).

Tagesson, T., Blank, V., Broberg, P., & Collin, S.O. (2009). What explains the extent and content of social and environmental disclosures on corporate websites: a study of social and environmental reporting in Swedish listed corporations. Corporate social responsibility and environmental management, 16(6), 352-364.

Tan, A., Benni, D., & Liani, W. (2016). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure and investor reaction. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 6(4S).

Thoradeniya, P., Lee, J., Tan, R., & Ferreira, A. (2015). Sustainability reporting and the theory of planned behaviour. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ullmann, A. A. (1985). Data in search of a theory: A critical examination of the relationships among social performance, social disclosure, and economic performance of US firms. Academy of management review, 10(3), 540-557.

Trevor, D.W., & Geoffrey, R.F. (2000). Corporate environmental reporting. A test of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 13(1), 10-26.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zhang, J. (2013). Determinants of corporate environmental and social disclosure in Chinese listed mining, electricity supply and chemical companies annual reports.

Received: 01-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. AAFSJ-22-12402; Editor assigned: 03-Aug-2022, PreQC No. AAFSJ-22-12402(PQ); Reviewed: 17-Aug-2022, QC No. AAFSJ-22-12402; Revised: 18-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. AAFSJ-22-12402(R); Published: 25-Nov-2022