Research Article: 2018 Vol: 22 Issue: 1

Design of Psychological Contracts in Japanese Firms and their Binding Force

Yasuhiro Hattori, Yokohama National University

Abstract

Keywords

Psychological Contracts, Psychological Contract Features, New-Graduate Hires, Psychological Contract Breach.

Introduction

While Japanese companies have increasingly non-permanent employees such as part-time staff and temporary workers since the 1990s, data from recent investigations have begun to show signs of a return to the trend of hiring new university graduates as permanent employees1 (JILPT, 2012). In a 2012 survey by the Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, 39.7% of responding firms expected to increase both the proportion and number of full-time employees in the organization over the next three years, a 6% increase from the same question three years prior (JILPT, 2012). Moreover, in the Recruit Works Institute’s 2009 Human Resource Management Survey, 79.2% of respondents said that their firm’s employment strategy focused on new university graduates, an increase from the 1990 rate of 67.7%. In parallel, 12.5% of respondents indicated a policy centred on hiring mid-career professionals, a decrease from the 1990 rate of 15.5% (RWI, 2010). It seems that Japanese firms have begun to revert to hiring new university graduates as regular employees.

Researchers have long noted that relationships between the employer and new-graduate hires in Japanese firms are characterized by an almost complete lack of codification in contract documents or related forms of the obligations that both parties must meet (e.g. long-term job security, acceptance of relocation) (Uchida, 1990 & 2000). Even if employees sign a written contract, this is seen as a mere formality and it is rare for terms-even important ones like job security-to be discussed explicitly between the two parties at the beginning of the employment relationship. Instead, the terms of employment are gradually understood after the hire, unspoken and tacitly, during the organizational socialization process (Nakane, 1970). Employment contracts for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms are like a “white stone plate,” in the words of Hamaguchi (2009) and the idea that the reciprocal obligations between companies and employees should be designed in an explicit, formal and meticulous manner at the first step of the employment relationship has been a rarity, historically speaking (Nakane, 1970). Researchers have long debated the advantages and disadvantages of the implicit, unwritten and flexible nature of these obligations: On the one hand, it is claimed to benefit Japanese firms by allowing them to dynamically modify their human resource management systems to adapt to changes in the business environment (Dore, 1986), while on the other hand, it has been viewed as a problem with employment in Japan by making organizations more susceptible to psychological contract breach (Hattori, 2010 & 2015).

In the case of permanent employees, the implicit, unwritten and flexible essence of their employment contracts has been attributed to Japanese employment practices, such as the long-term continuation of employer-employee relationships (Nakane, 1970) and the indirect nature of Japanese-style communication (Hall, 1976). It is precisely because they presume that the mutual relationship will last a long time that employees tolerate the practice of leaving the content of those reciprocal obligations vague, without confirming them in detail beforehand and allow for their gradual manifestation and as situations warrant-alteration with the passage of time. In addition, some accounts explain it as a consequence of Japanese-style communication, in which employee–employer interactions are non-verbal, vague and dependent on shared context and less contingent on explicit language (Hall, 1976).

Yet, these claims have not been validated by empirical research. Several studies have examined full-time employees at Japanese firms, including Ogura (2013); Suzuki (2007), but they did not target the employment contract itself, nor focus on full-time workers hired out of university. In light of the recent trend of reinvigorated hiring of new university graduates as permanent employees, the purpose of this study is to examine (1) how are employment contracts in Japanese companies designed, (2) and what kind of consequences do the employment contract features-such as implicitness, vagueness and mutability in these obligations-have on Japanese business organizations and individuals today. This study aims to examine these questions from the viewpoint of psychological contract features.

Psychological contract research to date has focused on identifying the content of the contracts, as well as elucidating the effects of failing to fulfil such contracts (Rousseau & Tijoriwala, 1998). In contrast, investigations of the features of psychological contracts at the individual level (e.g. whether or not they are put into writing, whether or not specific expectations are defined) have not entered the research mainstream, despite assertions of their importance from the early days (Rousseau & Tijoriwala, 1998). In this study, I will concentrate on feature-oriented research, which focuses on contract features, in the hopes of providing a fresh viewpoint from which to analyse the relationship between the organization and employees in Japanese firms.

Literature Review

The Evolution of Psychological Contract Research

Triggered by Denise Rousseau’s redefinition of the concept (1989), empirical research on psychological contracts started to accumulate in the literature from the 1990s onward2. Rousseau's definition held psychological contracts to be characterized by “an individual’s belief(s) in agreed-upon items and conditions regarding the mutually beneficial exchanges between that individual and another party” (p. 128).

While the definition accounts for wide-ranging obligations established between the employer and employees, irrespective of whether they are detailed in a written contract and even affirms that an objective consensus exists as to those mutual obligations, its primary importance actually lies in its focus on the individual’s (i.e., employee’s) perception that a given term is an obligation. Rousseau’s concept of the psychological contract treated it more broadly than in economics-based perspectives, which were limited to mostly contracts and written conditions: Her definition allowed us to treat the mutual obligations between employer and employee in a comprehensive manner, regardless of distinctions of whether they were put into words or not or whether they were explicit or implicit (Hattori, 2010). Separate from the contract verbalized or documented at the start of the employment relationship, her concept focuses on what the employee perceives to be the reciprocal obligations of him or herself and the organization, including tacit understandings, as well as which of these obligations contribute to perceptions of contract fulfilment or breach.

Researchers’ investigations from the 1990s onward have mainly aimed to identify the contents of psychological contracts and to clarify the consequences of employer breach (Rousseau & Tijoriwala, 1998; Conway & Briner, 2005 & 2009). The primary focus of the former type, called “contents-oriented” research, is to specify and systematically determine the contents of psychological contracts established between organizations and employees (“contract contents”3) and verify the effects of differences in contract contents on employee attitudes and behaviour (Rousseau, 1990). In contrast, the latter type, called “evaluation-oriented” research, seeks to verify the effects of organizational failure to uphold employee psychological contracts (“contract breach”4) on employee attitude and behaviour (Conway & Briner, 2005 & 2009; Hattori, 2010). Conway & Briner (2005) writes that evaluation-oriented studies comprise the majority of psychological contract research accumulated since 1989, forming the research mainstream.

In contrast, one can hardly claim that contents-oriented research has entered the mainstream today (Rousseau, 2011). This sub-field is concerned with the questions of what kind of specific obligations are perceived by employees in organizations. For this reason, it is well suited to describing specific employment contracts in organizations and to analysing discrepancies between the perceptions of employees and those of their employers. However, the contents of contracts established between employers and employees have been observed to vary depending on industry, organization type and employment status (Rousseau, 1995), making it poorly suited to comparing between different countries, types of industries/organizations or employees of differing employment status. Its weaknesses are most strikingly apparent in the problem of the inconsistency of latent variables for contents of psychological contracts (Conway & Briner, 2010). For example, when Rousseau (2000) developed a scale for the contents of psychological contracts, three factors were extracted by factor analysis: Transactional arrangements, relational arrangements and balanced arrangements; yet, in a study by De Vos, Buyens & Schalk (2003) using the same scale, five factors were extracted for employer obligations (career development, job content, social atmosphere, financial rewards and work-life balance) and five for employee obligations (in-and extra-role behaviour, flexibility, ethical behaviour, loyalty and employability). Variation is apparent among the factors extracted by different investigations and their findings are not stable. Other studies have found that which specific obligations load onto which factors changes dependent on the survey population (Rousseau, 1990; Robinson, Kraatz & Rousseau, 1994).

Thus, exactly the same contract contents can be interpreted differently depending on circumstances or even on the respondents, meaning they are extremely context-dependent. In summary, contents-oriented research is suited to analyses of samples in which researchers assume specific obligations are shared to a certain degree (e.g. long-term job security, offers of career development): These include analyses of permanent employees at specific firms or their comparison between generations. However, is not suited to comparisons of samples where the broader context is diverse, including cases where the contract contents fundamentally differ (e.g. full-time versus part-time employees, Japanese firms versus foreign-owned firms).

Feature-Oriented Research on the Sidelines

In parallel, a few research groups have identified features of psychological contracts that can be compared irrespective of specific context (“contract features” below) and examined psychological contracts in various kinds of industries, firms and organizations in terms of them (Rousseau & McLean Parks, 1993; Rousseau, 1995; McLean Parks, Kidder & Gallagher, 1998; Janssens, Sels & Van den Brande, 2003; Sels, Janssens & Van den Brande, 2004; McInnis, Meyer & Feldman, 2009). This sub-field is called feature-oriented research (Rousseau & Tijoriwala, 1998). In this context, “contract features” refers to employee perceptions about the kinds of general characteristics of the psychological contracts established between them and their employer (Sels et al., 2004; McInnis et al., 2009). Such research focuses not on the details of specific obligations, but rather on the state in which they were established (e.g. whether the agreements were explicit versus implicit, written versus unwritten).

For example, Sels et al. (2004) proposed six features that could characterize psychological contracts across different contexts: Tangibility, scope, flexibility, time frame and exchange symmetry and contract level. As well as developing and validating an assessment tool for measuring these six features, they revealed that long-term time frames and collective-level, not individual-level, agreements were significantly and positively related to affective commitment (Sels et al., 2004).

Later, McInnis et al. (2009) proposed a total of nine features-adding negotiation, formality and explicitness to the six of Sels et al. (2004) and used them as independent variables in multiple regression analysis to explain dependent variables corresponding to two features related to organizational commitment. They found that employee perceptions of contracts as being broad in scope, explicit, informal, equal in exchange symmetry, established by negotiation and long-term had significant positive effects on both affective and normative commitments, while their being asymmetric, imposed by the employer and short-term had significant negative effects on both types (McInnis et al., 2009).

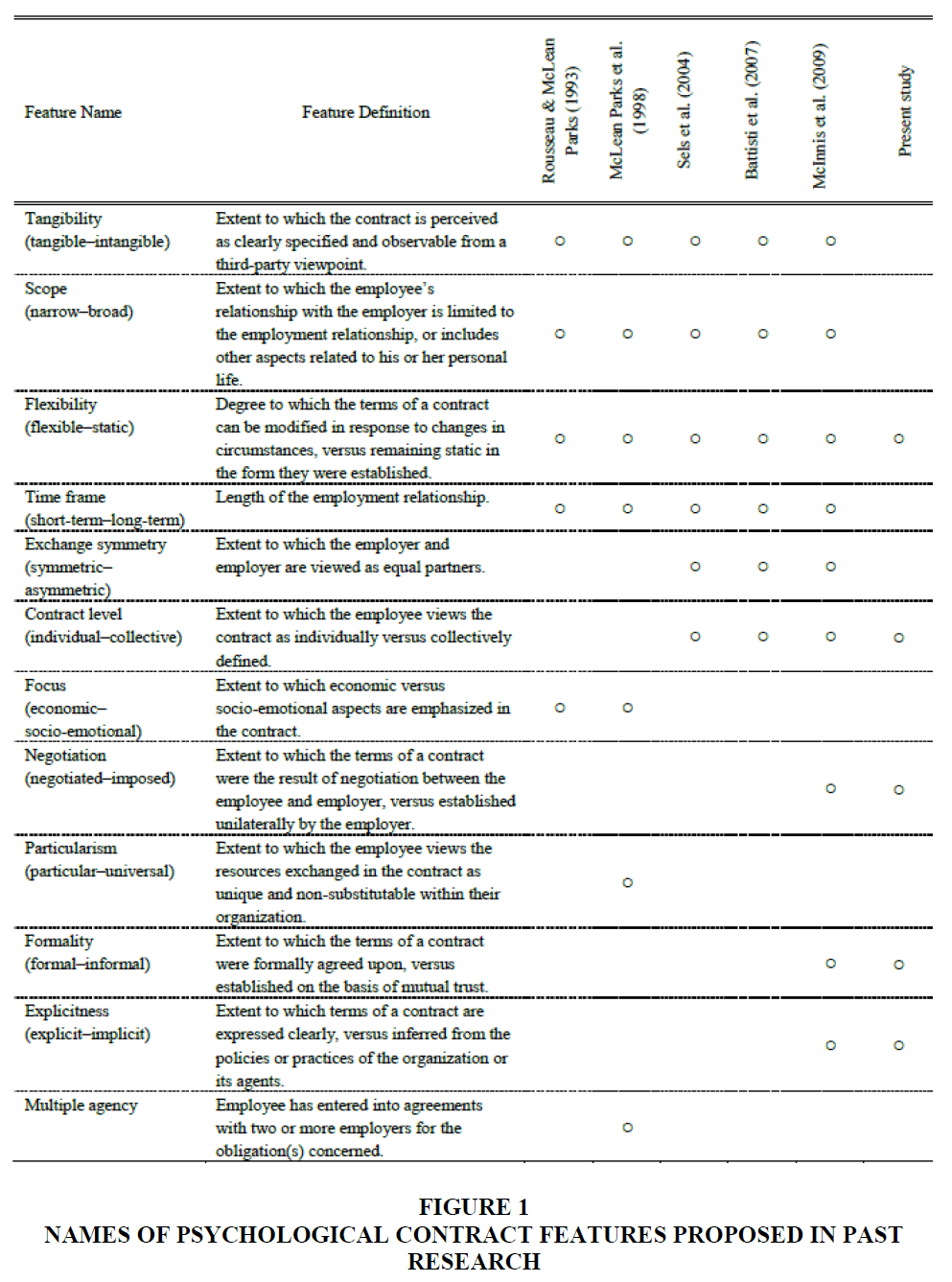

Other proposed features include focus, which is related to whether the focus of a contract is limited to economic aspects or instead extends to social and emotional dimensions (Rousseau & McLean Parks, 1993; McLean Parks et al., 1998); particularism, which indicates the extent to which the terms of a contract are unique to the employer or can be substituted in other places; and multiple agency, which is related to whether there are two parties to an agreement or more (McLean Parks et al., 1998). Figure 1 contains an overview of the major features proposed in the literature to date, along with the research studies that have presented them.

Feature-oriented research has at least two benefits. The first is its ability to identify characteristics shared by all psychological contracts regardless of specific context, allowing researchers to compare them across different industries, companies and organizations. If the main focus of contents-oriented research is answering questions about what obligations are established, irrespective of whether they are described in a written contract, feature-oriented research pays attention to the issue of in what form those obligations are established. This approach could provide important evidence for the theme of the present study, i.e., determining the design of psychological contracts for permanent employees at Japanese firms hired as new university graduates and clarifying its effects.

The second is the potential it holds to explain why psychological contracts are kept and broken. Evaluation-oriented research is capable of answering the question, “What kind of contracts is susceptible to breach of contract and what the resulting consequences are?” However, it is inherently incapable of answering the questions, “Why are contracts broken and why are they kept?” and “What can we do to make them easier to keep?” A feature-oriented approach to the design of psychological contracts could hold hidden potential to explain these matters, as will be described in detail below.

Challenges of Feature-Oriented Research

Nonetheless, there is an issue with the existing feature-oriented research published to date: It has not been established definitively which of the various contract features proposed to date are the most important ones. Notably, of the 12 features given in Figure 1, scope, time span, focus and particularism seem to more closely accord to ‘contract contents’ than to general features of all contracts. First, scope and focus seem to regard the breadth and type of the contents of psychological contracts, i.e., the matters of how much and what are included. Particularism deals with the question of whether or not the terms of a contract are unique to a given employer, which would fall under the rubric of contract contents. Time span, the length of the employment relationship, likewise corresponds to content of obligations, i.e., whether long-term job security is afforded or not.

Exchange symmetry characterizes the balance of power between employer and employee. However, this is more of a background, contextual factor that influences the contract relationship, rather than a feature of psychologist contracts per se. Tangibility relates to states that emerge as a result of explicitness and formality. Psychological contracts should automatically have high tangibility if they are relayed in explicit language and described as formal agreements, meaning it can hardly be called an independent feature. Accordingly, the parties have no room to wilfully design or make choices about psychological contracts in terms of this feature. Finally, multiple agencies regard temporary or other workers that have relationships with two or more organizations, which exclude it from the focus of this study.

On the other hand, one can convincingly argue that explicitness, flexibility, formality, level and negotiation are all important features of psychological contracts.

First, I consider flexibility and level, proposed in the past by multiple researchers. Flexibility has been adopted in all feature-oriented research since Rousseau & McLean Parks (1993). This concept deals with the question of whether established contents of psychological contracts can change according to circumstances (that is, not the content of a contract per se, but its mutability): As I will argue later, this feature has an important influence on psychological contract fulfilment. Proposed by Sels et al. (2004), level pertains to whether a contract (as a whole; not specific content) is tailor-made for specific employees or whether it applies widely and generally to all of them: This is a choice that can be made when designing psychological contracts.

Negotiation, formality and explicitness have all been incorporated from McInnis et al. (2009)’s work onward. First, we can conceive of the feature of negotiation-whether a contract is decided on unilaterally by the employer or established through negotiation between the employer and the employee-as inherently involved in psychological contract design. A classic topic in contract theory in law and economics (Milgrom & Roberts, 1992), formality relates to whether obligations are put into a written contract or not. Just as in legal and economic debates, formality here focuses on whether contract terms are put in writing or not from an objective, external viewpoint. In contrast, explicitness is focused on the matter of whether or not the employee personally sees the terms of a contract as explicit obligations, unrelated to these two features that are externally defined. The importance of the concept of the psychological contract lies in its focus on obligations derived from sources besides written agreements. For example, organizations broadcast a wide array of signals that serve as the genesis of psychological contract formation, including the policies and personnel systems it comes up with and the behaviour of its management, HR department and an employee’s supervisors (Rousseau, 1995). Accordingly, while obligations may not be described in the official contract, they could nonetheless exist in a definite state between an employer and its employees. The feature of explicitness gives attention to this distinction.

Based on the considerations above, the present study focuses on explicitness, flexibility, formality, level and negotiation in its efforts to describe the features of psychological contracts in Japanese firms (Figure 1). Below, we continue by constructing several hypotheses regarding the features of psychological contracts and the effects they have on the relationships between individuals and their organization.

Hypothesis Construction: Psychological Contract Features Of New-Graduate Hires At Japanese Firms

From these five features of contracts, how can we decipher the psychological contracts of permanent employees of Japanese firms hired at graduation? As mentioned in the Introduction, the psychological contracts of new-graduate hires at Japanese companies have long been considered to almost completely lack codification in the form of a contract document and even if a written contract is signed, this is seen as only a formality (Uchida, 1990 & 2000). It is rare for terms-even important ones like job security-to be made clear between the two parties at the beginning of the employment relationship: Instead, the terms of employment are gradually understood after the hire, unspoken and tacitly, during the organizational socialization process (Nakane, 1970). The reciprocal obligations between Japanese firms and new-graduate hires are a “white stone plate,” in the words of Hamaguchi (2009): The idea that the reciprocal obligations between companies and employees should be designed in an explicit, formal and meticulous manner at the first step of the employment relationship has been a rarity (Nakane, 1970).

Yet, these claims have not been validated by empirical research. Several studies have already examined full-time employees at Japanese firms, including Ogura (2013); Suzuki (2007), but they did not target the mutual obligations of organizations and full-time employees per se, nor focus on full-time workers hired out of university.

This study first clarifies some characteristics of permanent employees at Japanese firms hired at graduation in terms of psychological contract features. The specific approach adopted will be to compare this group (“new-graduate hires”) with full-time professionals hired by Japanese firms midway through their career (“mid-career hires”), new-graduate hires at foreign-owned companies and part-time workers. By comparing these categories in terms of the five contract features, our investigation aims to gain an understanding of the features of psychological contracts of new-graduate hires at Japanese firms relative to other kinds of employees. In addition, we will consider the question of how these psychological contract features affect employer contract fulfilment.

Hypothesis Construction: Psychological Contract Design

Explicitness and Formality

Sociologists and jurists have previously noted that in Japanese companies, the reciprocal obligations of the organization and its employees are almost never specified in detail in written contracts (Nakane, 1970; Honna, 1992; Uchida, 2000). For example, Nakane (1970) writes that the idea of articulating mutual obligations in a formal contract or other form, by which individuals are bound to follow certain behaviours, is inherently alien to Japanese people. Instead, those obligations are reliably fulfilled by connecting the two parties in a long-term relationship, which aligns their goals and interests. Similarly, Kawashima points out that in Japan, even important commitments like job security are never clarified at the beginning stages of the employment relationship and instead left unspoken5

In addition, new university graduates are not recruited in Japan to ‘fill vacancies’, i.e., by defining the duties to be performed in advance and when necessary, hiring individuals having the necessary qualifications, skills and experience. Instead, it is assumed that new-graduate hires will carry out a variety of responsibilities: Japanese employers place primary emphasis on checking that applicants have the latent capacity to do so and on their ‘suitability’ to working as a member of the organization for many decades after entering it (Hamaguchi, 2009). In this respect, they stand in contrast to mid-career hires and part-time employees, whose specific responsibilities and compensation are well defined in comparison. Mid-career hiring is closer to filling vacancies: People with the necessary qualifications, skills and experience are employed at the necessary time. Therefore, one would expect the mutual obligations between the organization and employees to be made explicit at the time of hiring and for them to be incorporated into formal employment contracts in a high proportion of cases. In the case of part-time workers, the trend is likely similar to mid-career hires: In most cases, the duties to be performed after hiring are well defined. The same can probably be said of new-graduate hires at foreign-owned firms in Japan, whose employment is considered to be closer in character to hiring patterns at Europe and America. The obligations that each employee must fulfil at foreign-owned firms, from the president down to general employees, are made explicit in formats such as “core job descriptions” and “limitations of authority” provisions. Therefore, reciprocal obligations are expected to have a high degree of formality and explicitness for this employee group compared with new-graduate hires at Japanese firms. We can derive the following hypotheses about explicitness and formality based on our discussion above.

Explicitness:

Hypothesis 1a: Psychological contracts are more implicit for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms than for the same at foreign-owned firms.

Hypothesis 1b: Psychological contracts are more implicit for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms than for mid-career hires at the same.

Hypothesis 1c: Psychological contracts are more implicit for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms than for part-time workers..

Formality:

Hypothesis 2a: Psychological contracts are more informal for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms than for the same at foreign-owned firms.

Hypothesis 2b: Psychological contracts are more informal for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms than for mid-career hires at the same.

Hypothesis 2c: Psychological contracts are more informal for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms than for part-time workers.

Flexibility: Psychological contracts in Japan are viewed as having features of a white stone plate, in that reciprocal obligations are not put in writing or made explicit at the time of hiring, as noted above. This viewpoint has been supported by empirical research by legal scholars. In his comparative research on Japanese and American views of contracts, Honna (1992) found for Americans, a written employment contract represents a strict agreement about what specific responsibilities they have to do. For Japanese, on the other hand, the employment contract is essentially perceived as a vague and unspoken agreement related to various responsibilities they will perform over a long period of time.

Furthermore, if an American employer or employee finds ambiguous provisions or inconsistencies in the contract, they will strongly argue for those points to be made more explicit and amended through a formal procedure; however, skepticism is almost never expressed about the contents of a contract in Japan, in the absence of extraordinary circumstances (Honna, 1992). This would imply that in Japan, not only are mutual obligations left indefinite at the outset of employment, but also provisions previously established can be dynamically modified through interactions between employees and the organization. We can derive the following hypothesis accordingly.

Hypothesis 3a: Psychological contracts are more flexible for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms than for the same at foreign-owned companies.

Similarly, new-graduate hires should have more flexibly defined responsibilities than mid-career hires or part-time workers, for whom the work to be performed at hiring is clear to a certain extent. As Schein (1978) has pointed out, the psychological contracts of new-graduate hires and their organizations are made explicit gradually, in the process of organizational socialization, not immediately at the hiring step. Employees come to understand their own psychological contract through a wide variety of messages signalled by the company, for example: Mission statements, remarks from management, the personnel systems instituted by their HR department and interactions with their superiors. In this sense, psychological contracts for new-graduate hires should have extremely high flexibility. Accordingly, we can derive the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3b: Psychological contracts are more flexible for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms than for mid-career hires at the same.

Hypothesis 3c: Psychological contracts are more flexible for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms than for part-time workers.

Negotiation: Next, we take a look at the feature of negotiation. According to Emerson (1962), the negotiating leverage one party can hold over another is determined by the degree to which they have resources the other party considers important and the degree to which the other party could obtain those resources elsewhere. In the context of the employment relationship, an employee’s negotiating power is increased at the time of hiring to the extent he or she brings to the table resources that can contribute to the organization’s competitive advantage and to the extent that resource’s supply is monopolized by that ‘irreplaceable’ employee (Rousseau, 2005). Since new university graduates employed at Japanese firms are primarily hired based on their latent capacity to perform responsibilities (Hamaguchi, 2009), there is little possibility for them to bring resources on board at the time of hiring that employers would consider scarce. From their perspective, there are plenty of other potential candidates for employment. As a result, new university graduates have extremely limited leverage that they can exercise when signing their employment contract and most have no choice but to accept the working conditions proposed by the employer. On the other hand, hiring practices at foreign-owned firms as well as for mid-career hires are based on the filling vacancies and so it is more likely that these individuals would have resources considered necessary and scarce by employers and more negotiating power as a result.

In contrast, just like new-graduate hires, it is unlikely that part-time workers would bring to organization necessary and scarce resources at the time of hiring. It is precisely for this reason that such employees are the first targets of cuts in periods of recession, acting as a buffer to prevent the ‘employment adjustment’ of permanent employees. Accordingly, we can derive the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4a: Psychological contracts are formed less by negotiation for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms than for the same at foreign-owned firms.

Hypothesis 4b: Psychological contracts are formed less by negotiation for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms than for mid-career hires at the same.

Hypothesis 4c: There is no difference in the degree to which negotiation contributes to the formation of psychological contracts between new-graduate hires at Japanese firms and part-time workers.

Level: Finally, we will consider the feature of level. Given that the specific duties to be performed by new-graduate hires at Japanese firms are indeterminate, it is improbable that individual employees will develop ‘tailor-made’ psychological contracts different from those of other employees. In addition, as mentioned above, when a job applicant lacks negotiating power, the probability that he or she gains a specific and individualized contract that is personally advantageous falls accordingly. As Rousseau (2005) has also noted, the organization and the employee need to go through meticulous negotiations for an employment contract to be regarded as ‘tailor-made’ by the employee; however, negotiation per se is not done for new university graduates, as mentioned above and so it would be difficult for them to develop such a personalized contract. Additionally, the specific circumstances associated with hiring new university graduates can make it difficult to introduce disparities in employment conditions between employees on-boarded at the same time at the company: Accordingly, the psychological contract that eventually forms should be the same among all new-graduate hires and act in a ‘collective’ manner.

In contrast, filling vacancies applies to the hiring practices for new graduates at foreign-owned firms as well as for mid-career hires, making it highly likely that the obligations demanded of applicants take a tailor-made form, different from other employees. Since mid-career employment involves hiring people with the necessary qualifications, skills and experience at the necessary time, the expectations of each individual hire and the specific obligations of both him or her and the organization, will probably be individually determined. Accordingly, we can derive the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5a: Psychological contracts are more collective for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms than for the same at foreign-owned companies.

Hypothesis 5b: Psychological contracts are more collective for new-graduate hires at Japanese firms than for mid-career hires at the same.

This specificity can be contrasted with part-time workers: While their obligations are more explicitly defined at the individual level than in the case of new-graduate hires, they are less likely to be unique to a given worker. The responsibilities of part-time employees are often substitutable, in that they can be performed by other employees in many cases. Accordingly, these workers’ psychological contracts would be expected to behave as collective agreements. Accordingly, we can derive the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5c: There is no difference in the collective nature of psychological contracts between new-graduate hires at Japanese firms and part-time workers.

Hypothesis Construction: Effects of Contract Features

What kinds of effects do these five features have on (employee) perceptions of employer fulfilment or non-fulfilment of contract? Past research on psychological contracts has revealed that employer contract breach has negative effects on employee attitude and behaviour; however, it has not inquired about the reasons why contract fulfilment/non P fulfilment happens in the first place or the precise factors that promote contract fulfilment/non P fulfilment. Assuming that employee perceptions of contract breach are connected to negative attitudes and behaviours, we must ask how we can prevent it from happening and how we can design psychological contracts to make this possible.

To do so, before proceeding we must first clarify the phenomenon of employer breach of contract: Above all, what does “employer” in this phrase refer to? In one of the first studies on psychological contracts, Levinson (1965) wrote that in reality, an individual’s relationship with his or her employer is experienced in aggregate, as a collection of relationships with specific individuals such as superiors or HR department staff. While these specific individuals do no more than act as agents of the organization, with their authority delegated by management, employees nonetheless perceive their words and behaviour as if they were the words and behaviour of the organization itself. In other words, employees perceive their organization to have a singular, independent ‘personality’ based on the interactions between these specific individuals. Through their observations of the words and actions of the agents, they develop an understanding of the content of the psychological contract between themselves and their employer and perceive employer fulfilment/breach of the psychological contract on this basis (Levinson, 1965).

Among these several agents, the one considered most important is the employee’s direct superior (Porter, Pearce, Tripoli & Lewis, 1998; Dabos & Rousseau, 2004). Dabos & Rousseau (2004) demonstrated that perceptions of the obligations of the organization are shared to a certain degree between employees and their superiors i.e., if one party believes that a contract is an employer obligation, then the other party does as well. They also showed that such perceptions being shared by both parties have a positive influence on various outcomes such as individual performance. By influencing the degree to which such perceptions are shared by employees and their superiors, explicitness, formality and other features of psychological contracts could influence their fulfilment/breach as perceived by employees.

First, when contract provisions are made explicit, not left unspoken and put into writing, not left in an unofficial form, it likely helps to align the perceptions of employees’ superiors (and HR staff i.e., the agents of the organization) with those of the employees themselves. This could help to eliminate discrepancies between both parties’ perceptions of responsibilities as well as misunderstandings, making it less likely for contract breach to occur as a result. Making contract provisions explicit likely has the additional benefit of forcing superiors to be highly cognizant of the responsibilities they must fulfil as part of the contract. Research on behavioural consistency has shown that when a commitment is made explicit, not vague, it makes individuals acutely conscious of their responsibility for the consequences of their behaviour, acting to encourage compliance with the commitment (Salancik, 1977). Making contracts explicit and formal should improve the likelihood of contracts being upheld by forcing superiors, the agent through which organizations fulfil contracts, to be keenly aware of their obligations associated therewith. One should therefore expect that contracts being explicit and formal would improve the likelihood of contract fulfilment and influence employee perceptions of the same, through these two mechanisms: Sharing perceptions between superiors and employees and strengthening the former’s awareness of their responsibilities to uphold their part of the contract. We can derive the following hypothesis accordingly.

Hypothesis 6a: The more explicit a contract’s contents are, the more strongly employees perceive their employer as upholding it.

Hypothesis 6b: The more formal a contract’s contents are, the more strongly employees perceive their contract to be upheld.

Similarly, when a psychological contract is established through mutual negotiation and not unilaterally imposed upon an employee by their employer, the negotiation process itself likely helps to coordinate perceptions between superiors, HR officials and employees. Discrepancies between employee and employer perceptions of responsibilities, as well as misunderstandings, could be eliminated when a psychological contract is reached by the two parties working together, regardless of whether its terms are formal or informal: As a result, it should be less likely for contract breach to occur. Additionally, when obligations are established through conscientious negotiation, it should reinforce superiors’ beliefs that they chose the agreements reached of their own free will and make them explicitly aware of their responsibilities with regard to contract fulfilment (Salancik, 1977). Accordingly, we can derive the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 6c: The more a contract is formed through negotiation, the more strongly employees perceive their contract to be upheld.

What are the consequences of a psychological contract being flexible, not static? According to Rousseau (1995), employee perceptions about what obligations consist of can vary depending on various factors, such as changes in circumstances and their own development. For example, it is conceivable that employees could come to view long-term employment as an important responsibility of their organization after an economic recession or upon hearing information about restructuring at other firms, despite not thinking of it as an organizational obligation at the time of hiring. Such changes in perception could occur more obviously when their contract is inherently an agreement that can be modified dynamically and not static. One would predict that employees are more likely to perceive employer breach of contract under such conditions. In addition, situations where obligations are readily changeable are at the same time situations where once-established agreements can be readily reneged on from the standpoint of superiors (the employer’s agents). For example, when upholding a given agreement is not a term specifically defined through negotiation between the organization and an employee, but just ‘for now’ or a non-binding goal, the party concerned probably feels no compunction to continue to comply with it. Accordingly, the degree to which employees perceive their employer as fulfilling their contract could also fall as a result. Hypothesis 6d can be derived accordingly.

Hypothesis 6d: The more flexible a contract’s contents are, the less strongly employees will perceive its fulfilment by their employer.

Finally, we consider the effects of level. Employees have firmer commitments to and higher awareness of personalized than collective-level contracts. For this reason, whether an employer (or rather, the employees’ superiors, the agents of the organization) has fulfilled their end of such contracts should be evaluated more stringently. Accordingly, breach of contract should be perceived more readily in this case than the case of a collectively established contract. In addition, the terms of individualized contracts are established through closed interactions between the employee concerned and personnel managers and those directly involved with fulfilling those terms (i.e., HR managers and immediate superiors) and are rarely known to the majority of other employees. Publicness is a quality of contracts that binds the parties concerned to uphold them; however, the only ones with knowledge of the contents of individualized contracts and who have an interest in complying with them, are the employee and the organizational members responsible for fulfilling the contract, which reduces their publicness (Salancik, 1977). As a result, from the employer’s perspective, the incentives for fulfilling such a contract are likely lower than for collective contracts. Accordingly, we can derive the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6e: The more individualized a contract’s contents, the less strongly employees will perceive its fulfilment by the employer.

Study Method

The hypotheses above were tested by analysing data collected from Japanese employees registered in a database kept by the Internet research company Macromill, Inc. via an online survey. The specific procedure of the survey was as follows. From August 6th to 8th, 2013, Macromill sent requests for participation and a URL link to the survey to 1030 randomly selected full-time Japanese employees in the database6.Respondents answered the online survey online on a voluntary and anonymous basis; data was collected online7. From the initial sample, individuals lacking response data for many question items or whose answers were strongly biased (e.g. all responses being a specific value) were excluded. Analysis was then performed for the effective sample consisting of 983 respondents.

Measurement Instruments

Psychological Contract Features

Janssens et al. (2003) measured the features of psychological contracts in a general sense, rather than pertaining to specific terms of such contracts. For example, they assessed explicitness using question items such as, “I expect from my employer that he unambiguously describes my rights within this firm,” and flexibility using items like “My employer can expect from me that I tolerate changes when introduced in the firm.” Responses were scored using Likert scales anchored by “1. Strongly disagree” and “5. Strongly agree.” This framework has an important consequence. Considering explicitness as an example, a high score would indicate that the terms of the psychological contract at that organization are ‘explicit.’ However, while a low score in this dimension implies that said terms are ‘not explicit,’ it does not necessarily entail the opposite, that they are ‘implicit.’ This is because by measuring two bipolar concepts (explicit-implicit) using a normal Likert scale; it prevents analysis from treating one of the concepts at the poles in isolation. McInnis et al. (2009) avoided this problem by establishing different questions for such mutually exclusive concepts: For explicitness, for example, respondents were asked if the commitments “made by my employer specify clearly what I can expect” to assess if contracts were explicit and if they “involve general promises without providing details or specific agreements” to assess if they were implicit. Responses to each question were scored using Likert scales anchored by “1. Strongly disagree” and “5. Strongly agree.” This method can be used to measure both the degree to which a contract with a given employer is explicit and the degree to which it is implicit; nonetheless, it has issues. First, analysis is complicated by the presence of two variables anticipated to be in a negative relationship. Second, the method cannot detect differences in the features of specific agreements within a contract, such as whether it applies to the guarantee of long-term employment differently from the provision of a definite career path.

Thus, we developed an original measurement instrument for this study as described below. First, five items were chosen from among the employer obligations included in the Japanese version of the Psychological Contract Scale, constructed by Hattori (2010). These five were chosen because of their importance as obligations and because they had resulted in high scores for breach in the previous study.

1. My employer shows me a definite career path.

2. My employer gives me clear explanations about assignment changes and transfers

3. My employer provides me with suitable education opportunities.

4. My employer is responsive to consultations about my career.

5. My employer guarantees me long-term employment.

Next, each item was assessed using the Semantic Differential (SD) method, as in Table 1. Respondents evaluated each of the five obligations above in terms of each of the five dimensions involved in psychological contract design, each using a six-point scale. Low scores corresponded to features on the left side of Table 1 (implicit, static, informal, collective and imposed), while high scores corresponded to features on the right side (explicit, flexible, formal, individual, negotiated). Thus, each of the five contract obligations were measured in terms of five contract-feature variables scored between 1 and 69, yielding a total of 25 variables. By evaluating obligations in this way, we can thus assess each feature-bipolar entities comprising mutually exclusive concepts such as ‘explicit’ and ‘implicit’-using one measurement scale.

| Table 1: Question Items For Contract Design Measurement Instrument | |||

| Explicitness | [Implicit] The question of whether I can expect my employer to meet this obligation has not been expressly discussed; I have no choice but to guess about it based on my organization’s policies and practices and through interactions with my superiors. |

⇔ | [Explicit] The matter of whether I can expect my employer to meet this obligation has been clearly described verbally or in writing. |

| Flexibility | [Static] I can continue to expect my employer to meet this obligation, even after time has passed. |

⇔ | [Flexible] My expectation that my employer will meet this obligation is only temporary; it is certainly possible that I will no longer have this expectation in the future. |

| Formality | [Informal] The commitment to meet this obligation is only based on trust between my employer and me: It lacks binding force in the legal sense. |

⇔ | [Formal] I feel the commitment to meet this obligation is an official agreement and associated with legal responsibility. |

| Level | [Collective] Employees in the same position as me in the same organization have the same obligations for this. |

⇔ | [Individual] My circumstances at employment were unique and so my particular obligations for this are different from those of other employees. |

| Negotiation | [Imposed] My obligations for this are not the result of formal negotiation with my organization, but instead the product of a unilateral decision by other people within it. |

⇔ | [Negotiated] My obligations for this are based on agreements settled through negotiation with my organization. |

Exploratory factor analysis by means of the principal factor method followed by promax rotation was conducted on these 25 manifest variables to check whether or not the five psychological contract features supposed in the study would be extracted as independent variables. Indeed, the five latent variables supposed a priori were extracted (explicitness, flexibility, formality, level and negotiation). However, it also extracted another latent variable loaded with the items concerning the guarantee of long-term employment. At least as far as can be judged from the results of factor analysis, this result signifies that obligations concerning long-term employment are of a different nature as others in psychological contracts and that this issue cannot be treated in the same manner. Another analysis was run after removing the five items related to long-term job security, yielding the five-factor structure shown in Table 2. The four items related to explicitness were loaded on Factor 1: This factor was thus named Explicitness (α=0.83). Similarly, each item related to level, formality, flexibility and negotiation was respectively loaded on Factors 2, 3, 4 and 5: These factors were named Level (α=0.86), Formality (α=0.81), Flexibility (α=0.73) and Negotiation (α=0.84) factors, respectively.

| Table 2: Factor Analysis For Contract Design: Primary Factors And Promax Rotations | |||||

| Explicitness | Level | Flexibility | Formality | Negotiation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational opportunities-Explicitness | 0.92 | -0.07 | -0.01 | -0.09 | -0.10 |

| Consultations-Explicitness | 0.76 | -0.05 | -0.04 | 0.06 | -0.01 |

| Assignments and transfers-Explicitness | 0.60 | -0.02 | -0.03 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| Career path-Explicitness | 0.57 | -0.02 | -0.10 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Consultations-Level | 0.09 | 0.81 | 0.02 | -0.01 | -0.09 |

| Educational opportunities-Level | 0.11 | 0.80 | 0.05 | -0.08 | -0.06 |

| Assignments and transfers-Level | -0.02 | 0.78 | -0.04 | 0.03 | -0.02 |

| Career path-Level | -0.29 | 0.71 | -0.07 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

| Consultations-Flexibility | 0.08 | -0.02 | 0.81 | -0.06 | 0.00 |

| Educational opportunities-Flexibility | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.75 | -0.07 | -0.02 |

| Assignments and transfers-Flexibility | -0.02 | -0.03 | 0.74 | 0.06 | -0.06 |

| Career path-Flexibility | -0.32 | -0.04 | 0.58 | 0.13 | 0.07 |

| Career path-Formality | -0.07 | -0.03 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 0.09 |

| Assignments and transfers-Formality | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.61 | 0.04 |

| Consultations-Formality | 0.36 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.53 | -0.05 |

| Educational opportunities-Formality | 0.39 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.44 | -0.08 |

| Career path-Negotiation | -0.03 | -0.06 | -0.06 | 0.08 | 0.74 |

| Assignments and transfers-Negotiation | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.60 |

| Educational opportunities-Negotiation | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.08 | -0.11 | 0.46 |

| Consultations-Negotiation | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.05 | -0.01 | 0.45 |

| Eigenvalue | 5.41 | 3.26 | 2.35 | 3.84 | 4.18 |

| Inter-factor Correlations | |||||

| Explicitness | Level | Flexibility | Formality | ||

| Explicitness | 1 | ||||

| Level | 0.33 | 1 | |||

| Flexibility | -0.09 | 0.24 | 1 | ||

| Formality | 0.65 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 1 | |

| Negotiation | 0.64 | 0.39 | -0.13 | 0.51 | |

Perceived Employer Contract Fulfilment

Hattori’s (2013) inventory was used to measure employer contract fulfilment as perceived by employees. Respondents answered each obligation item using a five-level Likert scale, from “1. My Employer Does Not Fulfil This Obligation at All” to “5. My Employer Conspicuously Fulfils This Obligation.” The employer contract fulfilment rating scale was constructed from these five obligation items and had a reliability coefficient of α=0.85. Employer contract fulfilment was constructed as the mean score for these five items.

Analysis Results

Table 3 contains descriptive statistics for the main variables used in the analysis, along with their inter-correlations. When interpreting the values, it is important to keep in mind that these five contract-design-related variables correspond to bipolar concepts i.e., Explicitness corresponds to implicit-explicit, Flexibility to fixed-flexible, Formality to informal-formal, Level to collective-individual and Negotiation to imposed-negotiated. For example, Explicitness was measured as a continuous value between 1 (implicit) to 6 (explicit) and had a mean score of 3.90. This indicates that the contents of the various obligations in Japanese firms tended, on balance, to lean towards explicit.

| Table 3: Descriptive Statistics And Inter-Correlations For Variables | ||||||||

| No. | Variable | Mean | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Explicitness (implicit–explicit) | 3.90 | 0.83 | 1 | ||||

| 2 | Flexibility (static–flexible) | 3.20 | 0.82 | -0.16 | 1 | |||

| 3 | Formality (informal–formal) | 3.88 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.00 | 1 | ||

| 4 | Level (individual–collective) | 3.74 | 0.86 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 1 | |

| 5 | Negotiation (negotiated–imposed) | 3.91 | 0.84 | 0.67 | -0.13 | 0.61 | 0.34 | 1 |

| 6 | Employer breach of contract | 2.76 | 0.85 | 0.50 | -0.28 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.40 |

Note: Descriptions of significance level are omitted: Due to the large sample size, even small correlation coefficients reached statistical significance. *p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01. Dummy variables excluded. Readers should note that while trust in the organization and employer contract fulfilment were measured using a 5-step Likert scale, contract feature variables (No. 1-5) were measured using a 6-step, semantic differential (SD) rating scale. The closer a score was to 6 in a given feature dimension, the more the contract design was perceived as explicit, flexible, formal, individual or negotiated; the closer it was to 1, the more it was perceived as implicit, static, informal, collective or imposed.

Psychological Contract Features of New-Graduate Hires at Japanese Firms: ANOVA

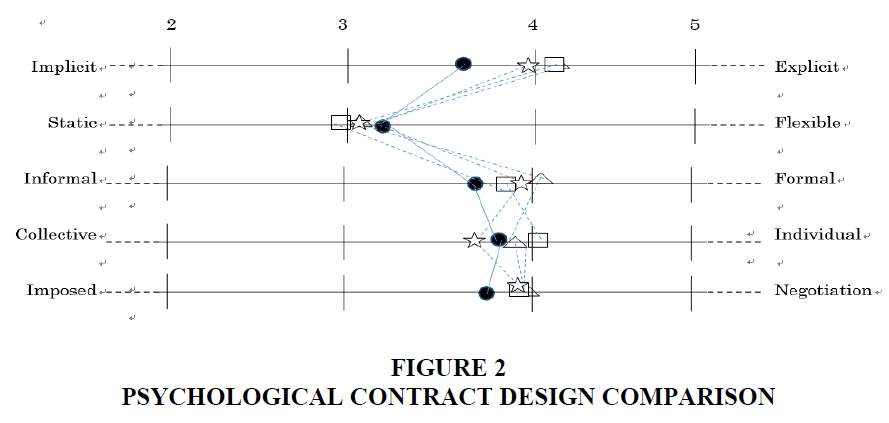

In Figure 2, mean scores for each variable are plotted along respective, continuous scales with opposite concepts at either end. The mean scores plotted are for different sub-populations isolated from the full sample: (1) New-graduate hires at Japanese firms (N=262), (2) mid-career hires at Japanese firms (N=433), (3) full-time employees at foreign-owned firms (N=55) and (4) part-time employees at both Japanese and foreign-owned firms (N=233).

With these data, we can test the hypotheses in Hypothesis Groups 1 through 5. To broadly summarize, the psychological contracts of new-graduate hires at Japanese firms are-relative to other employee categories-implicit, informal, flexible and collective and imposed. Figure 2 shows their scores for all feature dimensions are close to the theoretical mean of 3.5 or even slightly to the right of the respective scales except for Flexibility (Explicitness=3.66, Formality=3.71, Negotiation=3.81, Level=3.79, Flexibility=3.26). These data signify that their scores on these five continuous feature dimensions tend slightly toward the explicit, static, formal, individualized and negotiated sides of the respective scales.

Bear in mind that there is not much significance in the absolute values of scores measured with Likert-type scales8. Instead, what is important to note is how these scores are plotted relative to the scores of other employee categories. Compared with the other three employee categories, new-graduate hires had scores for Explicitness (3.66), Formality (3.71) and Negotiation (3.81) that were more to the left, a score for Flexibility (3.26) more to the right and a score for Level (3.79) midway between the three.

Next, scores for the five feature dimensions between new-graduate hires at Japanese firms were compared with those of the other employee categories by means of one-way ANOVA. In Figure 2 and Table 4, variable scores for which a statistically significant difference with respect to new-graduate hires at Japanese firms are indicated by asterisks to their upper right. Significant differences can be seen in Explicitness and Formality with respect to mid-career hires and part-time workers. However, no significant differences could be found between these employee categories for any other features. In addition, no differences were found with respect to new-graduate hires at foreign-owned firms at the 5% significance level. The results above support Hypotheses 1b, 1c, 2b, 2c, 4c and 5c, but fail to support Hypotheses 1a, 2a, 3a, 3b, 3c, 4a, 4b, 5a and 5b.

| Table 4: Significant Differences Can Be Seen In Explicitness And Formality With Respect To Mid-Career Hires And Part-Time Workers |

||||

| Japanese Firms New-graduate Hires? N=262 (26.6%) | Japanese Firms Mid-career Hires? N=433 (44%) |

Foreign-owned Firms? New-graduate Hires N=55 (5.6%) | Part-time Workers? N=233 (23.7%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explicitness (implicit-explicit) | 3.66 | 3.98*** | 4.01* | 4.03*** |

| Flexibility (static-flexible) | 3.26 | 3.18 | 2.96 | 3.21 |

| Formality (informal-formal) | 3.71 | 3.91** | 3.87 | 4.00*** |

| Level (individual-collective) | 3.79 | 3.68 | 4.01 | 3.86 |

| Negotiation (negotiated-imposed) | 3.81 | 3.96 | 3.93 | 3.95 |

Results for Contract Features

What kinds of effects do these contract features have on employee perceptions of contract fulfilment by their employer? Table 5 shows the estimation results for a regression analysis using the five features as independent variables and the perception of contract fulfilment as the dependent variable. Analysis results for only new-graduate hires-the concern of the study-are displayed in the left-hand columns, while those for the whole respondent sample are shown in the right-hand columns. While there is not much difference between new-graduate hires and the whole sample in terms of the signs of the coefficients for any of the independent variables, slight differences can be seen in the statistically significant variables. This could be a result of the different sample sizes of the two populations.

As the concern of this study is full-time employees hired by Japanese firms after graduating university, the left-hand data are used for the validation of Hypothesis Group 6. According to Table 5, contracts being explicit (β=0.33, p<0.01) or established through negotiation (β=0.24, p<0.01) had positive effects on employees’ perception of contract fulfilment by the employer, while being individualized (β=-0.11, p<0.05) had a negative effect on it. Significant effects were not observed for contracts being formal or flexible.

Therefore, the results supported Hypotheses 6a, 6c and 6e, but failed to support Hypotheses 6b and 6d.

Discussion And Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the questions of how psychological contracts are designed for permanent employees of Japanese firms hired at graduation and how their design influences employee perceptions of employer breach of contract, in terms of psychological contract features. Here, we will briefly summarize the findings discovered in the present study and discuss their implications.

Psychological Contract Features of New-Graduate Hires at Japanese Firms

Figure 2 shows that the psychological contracts of new-graduate hires at Japanese firms are more implicit and informal than those of mid-career hires and part-time employees. These data show that the claims of sociologists and legal scholars-that the reciprocal obligations between Japanese firms and regular employees hired at graduation are almost never described in detail in the form of written contracts-still apply today and seem to support that notion that the employment relationship of regular employees at Japanese firms truly starts based on a ‘white stone plate’.

However, the analysis results of the present study also failed to indicate any differences between these new-graduate hires and other types of employees in terms of the other contract features examined: Flexibility, level and negotiation.

First, the flexibility rating tended toward the left side of the scale (i.e., toward “static”) in each employee category, as can be seen from Figure 2. It’s difficult to state so definitively from a study of only Japanese participants, but this finding shows that psychological contracts in Japan, once established, are perceived to a certain degree as static by all types of employees, regardless of employment status. According to Honna (1992) study on formal employment contracts, if an American employer or employee finds ambiguous provisions or inconsistencies in the contract, they will strongly urge for those points to be made more explicit and amended through a formal procedure; however, skepticism is almost never expressed about the contents of a contract in Japan, in the absence of extraordinary circumstances. Apparently, the same can be said of psychological contracts. In summary, as is classically seen in regular employees hired at graduation, the extent to which the mutual obligations between employer and employee are made explicit and put into writing may indeed be low in Japan, but once the terms of the contract are established, employees may perceive the obligations as robust and resistant to casual changes.

As for the features of level and negotiation, new-graduate hires’ ratings of their scores were almost no different from those of other employee categories. Looking at all respondents, their scores tended to lie on the right side of the scale (i.e., towards individual-level contracts). While drawing conclusions based on these data similarly suffers from the limitation of the study population consisting of only Japanese respondents, these are interesting findings nonetheless, which suggest that all employees at Japanese firms, regardless of employment status, may perceive psychological contracts at the individual level and see their terms not as something forced upon them by the organization, but as the fruit of their own negotiations. At least two interpretations of these findings are possible. One is that they reflect a transformation and diversification in how employees perceive their own careers (Kanai, 2002; Suzuki, 2007) i.e., that what employees demand of an organization has become ‘personalized.’ As employee attitudes toward their careers have diversified, intra-organizational variation in the contents of their psychological contracts may have increased. Another interpretation is that individuals hold cognitive biases i.e., employees believe (or want to believe) that they are special and different from others and that the relationship between themselves and their organization is something they personally chose.

If one assumes that mid-career hires tend to be employed according to a process of ‘filling vacancies,’ one would expect that the obligations of organizations and employees in this category would become more individualized in most cases. However, the data here suggest that the reality is different. Mid-career hires scored lower on the level scale than other employee categories, although not to a statistically significant degree. This could be related to issues with how mid-career hires are treated in Japanese firms. Several studies have pointed out that even when employees are hired by an employer with the expectation that they will perform specific duties and contribute to the organization using certain skills (and even when the employee him or herself expects to), the employer does not necessarily make full use of those skills after the hire (Hattori, 2015). Perhaps the dissonance between their expectations at the hiring stage and the organizational reality after being hired makes it more difficult for mid-career hires at Japanese firms to fully appreciate their own psychological contract as ‘individualized.’

Another important finding is the lack of differences in psychological contract features of regular employees hired after graduation between Japanese and foreign-owned firms. Figure 2 indicates that the contract features of new-graduate hires at foreign-owned firms are even more similar to those of comparable employees at Japanese firms than to mid-career hires at Japanese firms or part-time workers. Three reasons could account for this result. The first is that because respondents of various nationalities, not just Western countries, were present in the foreign-owned firm data in the present study, eliminating differences between Japanese and Western employees that are typically apparent. The second interpretation is that there is actually no difference between the hiring systems for new university graduates of Japanese firms and foreign-owned firms in terms of how they influence the features of psychological contracts between employers and employees. The third and most realistic, interpretation is that the segment of the sample belonging to foreign-owned firms was simply too small. Figure 2 indicates that the differences between the ratings of regular employees at foreign-owned firms and the ratings of those at Japanese firms are, at minimum, of the same order as their differences with other categories. It is entirely conceivable that if the sample size were adequate, a statistically significant difference would have been observed between these two groups.

Based on the discussion above, we can conclude that psychological contracts of regular employees at Japanese firms hired at graduation, at least in terms of how they compare to those of mid-career hires and part-time workers, are more implicit and informal. However, we cannot claim there were any differences between these employee categories for the features of flexibility, level and negotiation.

Relationship between Contract Features and Contract Breach

The analysis results revealed that employees have stronger perceptions of their employer upholding their end of their psychological contract when the employer’s obligations are explicit and when these obligations are established through negotiations between the employee and the organization. Explicitness helps to align the perceptions of superiors (and HR staff i.e., the agents of the organization) with those of the employees themselves. This eliminates discrepancies between employee and employer perceptions of responsibilities, as well as misunderstandings and perceptions of contract breach become less likely to occur as a result. In addition, explicitness could make an employee’s superior (the agent of the employer) more strongly cognizant of their responsibilities in upholding their part of the contract. Explicit contracts could help to improve employer contract fulfilment by acting through these two mechanisms: Sharing perceptions between superiors and employees and strengthening the former’s awareness of their responsibilities to uphold their part of the contract.

In contrast, contracts being written did not significantly influence their binding force. As Honna (1992) writes, Japanese may have a weaker appreciation of written contracts compared with Americans: Accordingly, they would seldom regard such documents as constraining their behaviour. Therefore, whether or not obligations are put into writing may not be as important in explaining the apparent advantages of explicitness-both in coordinating the perceptions of superiors and subordinates and in committing superiors to fulfil their end of the contract-as whether or not said obligations are expressed in clear language. Discussions of the binding force of contracts in law and in economics have emphasized the matter of whether the terms of a contract are written and official or not (Milgrom & Roberts, 1992). In contrast, this study showed the possibility that explicitness is an independent feature of contracts, separate from formality and moreover that of these two qualities, explicitness is what actually affects contract fulfilment.

Why is explicitness more important than formal? It seems that the Japanese socio-cultural context is deeply involved in this. Some Japanese sociologists posited that behaviours of Japanese people (including Japanese managers) are more affected by the relationship with others than personal personality (Watsuji, 1935; Hamaguchi, 1977). In this view, Japanese people must nurture and maintain our relationships with other people and with society at large in order to retain our humanity. Hamaguchi (1977) articulated an explicit theory of Japanese selfhood based on the notion of a “contextualized-person (or people)” that is governed by ritual interactions in social groups. Hamaguchi’s model establishes a contrast between the Euro-American egocentric models of self as an individual versus the Japanese model of self which is a social-self. In this contextualized view, who a person is and the actions he or she takes are determined based on the person’s relationship with others. One must adjust appropriately whenever the people with whom one interacts changes. Managers in the organization are also influenced by the relationship with others. Discussion of manager’s behaviour in Japan, both by practitioners and academics, generally is in line with this contextualized-view (Hattori & Heller, 2018). Because of this behavioural principle, Japanese managers would place great emphasis on explicit contracts established with their subordinates. For managers, an explicit agreement is a promise that was created in the “inside” of the relationship with the subordinates. On the contrary, although Japanese companies also create formal contracts at the time of recruitment, the items included in these are often very ambiguous and too general. In many cases, the contract is not tailor-made for each employee. Therefore, for managers, formal contracts may be recognized as "a promise from outside".

In line with this, contracts being established by reciprocal negotiation also had a positive effect on the degree of employer contract fulfilment perceived by employees. The negotiation process itself likely helps to coordinate perceptions between superiors, HR officials and employees. In addition, such obligations should reinforce the beliefs of superiors-the agent of the organization-that they chose the agreements reached of their own free will and make them explicitly aware of their responsibilities for what they must do to fulfil the contract.

As expected, level had a negative effect on the perception of contract breach. This also can be interpreted from the contextualized-view discussed above. According to the study comparing behaviour between Japanese and Americans (Yamagishi & Yamagishi, 1994), Japanese keep promises in situations where it is easier for third parties to see whether they have kept their promises or not. In circumstances where it is difficult for the three to see, however, Japanese person do not always keep their promises. Because Individualized contract is a contract for a specific employee, the number of people who monitor the fulfilment of agents (managers and HR) is small. In contrast, collective contracts are monitored by many employees in its nature. Although Japan is the society where actions are determined by relationships with others, promises that are not embedded in social networks may breach. In addition, employees commit more strongly to their own individualized contract than they do to collective contracts: Consequently, their assessments of employer contract fulfilment should be stricter and it becomes more likely for them to perceive contract breach.

Finally, with regard to flexibility, while a statistically significant relationship was observed in the analysis of the complete sample between it and contract breach, no such correlation was observed in the respondent segment of new-graduate hires. Normally, when contractual obligations can be modified dynamically, it would become more likely for changes to occur that employees can perceive and accordingly easier for them to detect employer breach of contract. In addition, such flexible obligations also represent situations where once-established agreements can be readily reneged on from the standpoint of superiors (the employer’s agents), which should reduce the likelihood of contract fulfilment. In the case of new-graduate hires, however, such apparent changes to contract terms may not occur as readily, preventing divergences in opinion from occurring between them and superiors.

One of the contributions of the present study is its focus on psychological contract features, to serve as a framework for describing relationships between the organization and its new-graduate hires in Japanese firms, as well as a framework to compare these individuals with other categories of employees. As has already been noted by many researchers, one of the characteristics of the psychological contract concept is that it describes the relationship between the company and the employee at the content level i.e., in terms of specific reciprocal obligations between the two parties (Rousseau, 1989; Hattori, 2010). While this specificity was originally envisioned as an inherent feature of the concept, it has simultaneously acted to hinder the expansion of this research field, as has been pointed out by Sels et al. (2004); Conway & Briner (2005) among others. One would naturally expect a certain degree of content-level variation in psychological contracts at the industry level, the company level and even within an organization (Hattori, 2013). In the extreme hypothetical case, it is even possible that as there are many combinations of contract contents as there are organizations or even employees. With its focus on specific contract contents, the content-oriented approach holds great significance in describing the specific contents and fulfilment status of reciprocal obligations within a firm. However, it is ill suited to comparative research between industries or between firms or studies that attempt to uncover patterns connecting the two. This methodological issue could explain the bulk of the reasons why the mainstream of psychological contract research has been evaluation-oriented and not content-oriented. To compensate for the weaknesses of the content-oriented approach, this study once again focuses on the feature-oriented approach, to date relegated to the side-lines, as a new way to describe the relationships between organizations and individuals. By dealing with psychological contracts in terms of a small number of features, such as explicitness and formality, research can compare contracts while overcoming the confounding effects of differing specific contexts. In addition, this approach could provide answers to the questions of how to design the reciprocal obligations between employer and employee before the start of the employment relationship and what the precise conditions is that improve the likelihood of contract fulfilment.

In closing, a few limitations of the present study should be mentioned. The first is the fact that it was a cross-sectional study. In order to verify the design of psychological contracts in an organization and its influence on the perception of contract fulfilment, contract features and perceived contract fulfilment should be measured at different times in future works. The second limitation concerns the study design. What this research examined was a comparison between Japanese people, not of Japan with the West. In other words, the characteristics identified in the present study only apply to new-graduate hires in the context of a comparison between different employee categories within Japan; they were not determined via an international comparison. Performing international comparative studies should permit us to determine the matter of whether or not the feature-oriented approach is effective as a framework for comparing employee psychological contracts across diverse contexts. The third limitation concerns the measurement of psychological contract features. In this study, the five obligations in psychological contracts that were measured have been considered to have high importance in other investigations to date. Would similar results have been found if contract features had been measured for other contract contents? This matter must first be verified in order to claim that the feature-oriented approach is feasible for comparing employment contracts generally, with a scope that extends beyond the effects of specific contract contents at individual organizations.

This manuscript closes by re-emphasizing the fact that the feature-oriented approach, if it can overcome these limitations, is promising both as a new development in psychological contract research that has reached maturity in the modern day and as a new vantage point from which to analyse employment relationships in Japanese firms.

Endnotes

1. In the Japanese labour market, permanent employees refer to staff hired without special arrangements in their employment contract (Okubo, 2006). Generally speaking, their contracts are characterized by the lack of a fixed employment period, regulations governing dismissal and full-time working hours with obligatory overtime within a certain range (Ogura, 2013). In addition, new university graduates refer to individuals expected to matriculate from university at the end of the next school year at the point in time they are seeking employment. In the present study, the term new-graduate hires is used to indicate permanent employees hired by companies as new university graduates and permanent (or full-time) employees to full-time workers generally, including both those hired mid-career and upon graduation, unless otherwise indicated.

2. Readers interested in research trends prior to 1989 can find detailed information in Roehling (1997); Hattori (2013).

3. Contract contents refer to employees’ beliefs about their obligations to their employer, as well as their employer’s obligations to them as employees (Conway & Briner, 2005).

4. Contract breach refers to the employee perception that their employer has failed to meet their obligations, in violation of their expectations (Conway & Briner, 2005).

5. According to Macaulay (1963) & McMillan (2002), it is very common for the employer-employee relationship in American businesses to involve mechanisms besides written contracts entered into voluntarily, such as hierarchical control on the presumption of an authority-based relationship. However, the present study is unable to compare the U.S. and Japan due to data constraints. Accordingly, in the same manner as Honna (1992), this study’s discussion will proceed under the assumption that the former mechanism will be more heavily weighted in Japan, while the latter will be more heavily weighted in the US.