Research Article: 2024 Vol: 27 Issue: 2

Defining the Usefulness of Dynamic Capabilities in Business

Saurav Kumar, K.B Womens College

Citation Information: Kumar, S. (2024). Defining the usefulness of dynamic capabilities in business. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 27(2), 1-11.

Abstract

Today’s business world is changing from what it was just a decade ago. Dynamic capabilities have gained significant prominence in strategic management research. The growing popularity of explaining firm performance through dynamic capabilities has motivated plenty of conceptual development in the field. The word dynamic means that the organization can follow the changes; they are willing to make changes and adapt to the current or upcoming situation. An organization with dynamic capabilities surely will help prepare itself for any challenges, creating an advantage for itself. When the organization has dynamic capabilities, it can avoid any mistakes that could happen and transform them into an opportunity. The strength of a firm's dynamic capabilities help shape its proficiency at business model design. Dynamic capabilities enable business enterprises to create, deploy, and protect the intangible assets that support superior long- run business performance. Enterprises with strong dynamic capabilities are intensely entrepreneurial. They not only adapt to business ecosystems, but also shape them through innovation and through collaboration with other enterprises, entities, and institutions (Teece, David 2007). Dynamic capabilities are also believed to be the key to sustaining organizational innovation and creativity, especially in a highly dynamic and volatile environment. The research aims to deliver the significance of dynamic capabilities possessed by business firms.

Keywords

Dynamic Capabilities, Dynamic Capability Theory, Importance of Dynamic Capability.

Introduction

Dynamic itself means that the conditions change consistently, going with the environment’s flow. Therefore, the organization needs dynamic capability, including adaptability, to respond to the changes. Once they have grasped the concept of adaptability, the organization may seize the opportunity available in the market. Being dynamic means that an organization is always ready for the next new challenge. Every business must become a dynamic enterprise an organization that can quickly respond to changes in technology and consumer expectations. The field of strategy has mounted an enormous effort to understand, define, predict, and measure how organizational capabilities shape competitive advantage. While the notion that capabilities influence strategy dates back to the work of Andrews and the foundations to dynamic capability theory can be traced back to Penrose (1952) in her theory of the growth of the firm. The dynamic capability view has become one of the most vibrant topics in the domain of strategic management, and has even been referred to as ‘the new touchstone firm-based performance-focused theory’ (Arend & Bromiley 2009). D’Aveni highlighted the importance of having dynamic organizational capabilities to survive in a hyper-competitive environment. Dynamic capabilities are also believed to be the key to sustaining organizational innovation and creativity, especially in a highly dynamic and volatile environment. Dynamic capabilities allow firms continually to have a competitive advantage and may help firms to avoid developing core rigidities which inhibit development, generate inertia and stifle innovation (Leonard-Barton 1992). DC theory was derived from RBV theory and compensated for that theory’s shortcomings when it came to explaining sustainable competitive advantage and superior performance in a dynamic environment. The resource-based view (RBV) argues that resources that are simultaneously valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable and imperfectly substitutable (VRIN) are a source of competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). The underlying assumptions on which the RBV of the firm is based are that resources are heterogeneous across organizations and that this heterogeneity can sustain over time. It is a theory to explain how some firms are able to earn super-profits in equilibrium and, as such, it is essentially a static view (Priem & Butler 2001; Lockett et al., 2009). It does not specifically address how future valuable resources could be created or how the current stock of VRIN resources can be refreshed in changing environments: this is the concern of the dynamic capability perspective. This perspective is argued to be an extension of the RBV; it shares similar assumptions Barney (1991), and it helps us understand how a firm’s resource stock evolves over time and thus how advantage is sustained. The work was further extended by (Nelson, 1985). An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change, which addressed the role of routines and how they shape and constrain the ways in which firms grow and cope with changing environments. The dynamic capability acknowledges that ‘the top management team and its beliefs about organizational evolution may play an important role in developing dynamic capabilities’ (Rindova & Kotha, 2001). How firms change, sustain and develop competitive advantage and capture value are critical concerns to both practitioners and academics alike and, while many fields address change-related issues (e.g. organization learning, cognition, innovation etc.) none, except the dynamic capability perspective, specifically focuses on how firms can change their valuable resources over time and do so persistently. This is why the perspective is attracting increasing attention. Since the DCV first appeared in scientific literature Teece (1990), several hundred research publications have elaborated on this approach (Di Stefano et al., 2010). Another indication that the DCV is maturing into an established perspective is the recent publication of the first introductory textbooks (Helfat, 1997; Teece, 2007). The most seminal papers on dynamic capabilities Eisenhardt & Martin (2000); Helfat 1997; Teece, 1990; Zollo & Winter (2002) are among the highest cited in the broader array of strategic management publications (Furrer et al., 2008). In these articles, dynamic capability has been introduced, for instance, as ‘the firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments’ Teece (1990) or as ‘the firm’s processes that use resources – specifically the processes to integrate, reconfigure, gain and release resources – to match or even to create market change’ (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). Considering that the responsiveness of a firm’s resource stock to increasingly turbulent environments is associated with competitive advantage, dynamic capabilities are of inherent strategic relevance to a firm. However, Eisenhardt & Martin (2000) and Zollo & Winter (2002) emphasize that firms also need dynamic capabilities in markets characterized by lower rates of change, in order to keep pace with competitive dynamics. The DC perspective of accelerated internationalization in born global firms by Weerawardena, et al. (2007) is a fitting example of how specific DC concept scenarios could be realized. The research aims to deliver the significance of dynamic capabilities possessed by business firms (Leonard‐Barton, 1992).

Defining and Understanding Dynamic Capabilities

Dynamic capabilities are ‘The firm’s processes that use resources – specifically the processes to integrate, reconfigure, gain and release resources – to match or even create market change. Dynamic capabilities thus are the organizational and strategic routines by which firms achieve new resources configurations as markets emerge, collide, split, evolve and die’ (Eisenhardt & Martin 2000). ‘A dynamic capability is a learned and stable pattern of collective activity through which the organization systematically generates and modifies its operating routines in pursuit of improved effectiveness’ (Zollo & Winter 2002). Dynamic capabilities ‘are those that operate to extend, modify or create ordinary capabilities.’ They are ‘the abilities to reconfigure a firm’s resources and routines in the manner envisioned and deemed appropriate by its principal decision-maker’ (Zahra et al., 2006). More recently, Wang & Ahmed (2007) have defined dynamic capabilities as ‘a firm’s behavioural orientation constantly to integrate, reconfigure, renew and recreate its resources and capabilities and, most importantly, upgrade and reconstruct its core capabilities in response to the changing environment to attain and sustain competitive advantage’. Helfat (1997) offer this definition: ‘the capacity of an organization to purposefully create, extend or modify its resource base’. Winter explains, dynamic capabilities govern the rate of change of a firm’s resources and notably its VRIN resources. Those VRIN resources, i.e. the firm’s resource base, enable a firm to achieve sustained competitive advantage. Here, in line with Barney (1991) and Helfat (1997), a resource is defined in its broad sense, and hence it includes activities, capabilities, etc., which allow the firm to generate rents. If a firm possesses VRIN resources but does not use any dynamic capabilities, its superior returns cannot be sustained; without dynamic capabilities, a firm’s returns may be short lived if the environment exhibits any significant change. Dynamic capabilities allow firms continually to have a competitive advantage and may help firms to avoid developing core rigidities which inhibit development, generate inertia and stifle innovation (Leonard-Barton, 1992). Core rigidities are the flipside of VRIN resources: they are resources that used to be valuable but have become obsolete and inhibit the development of the firm. In other words, they are resources that have not been appropriately adapted, upgraded or restructured through dynamic capabilities. Bowman and Ambrosini building on Teece (1990) explain that dynamic capabilities comprise four main processes: reconfiguration, leveraging, learning and creative integration. Reconfiguration refers to the transformation and recombination of assets and resources, e.g. the consolidation of central support functions that often occurs as a result of an acquisition. Leveraging involves replicating a process or system that is operating in one business unit into another, or extending a resource by deploying it into a new domain, for instance by applying an existing brand to a new set of products. Learning allows tasks to be performed more effectively and efficiently as an outcome of experimentation, reflecting on failure and success. Finally, creative integration relates to the ability of the firm to integrate its assets and resources, resulting in a new resource configuration. Dynamic capabilities are sometimes argued to include search, i.e. identifying opportunities and threats, or the ability to sense changing customer needs, technological opportunities and competitive developments.

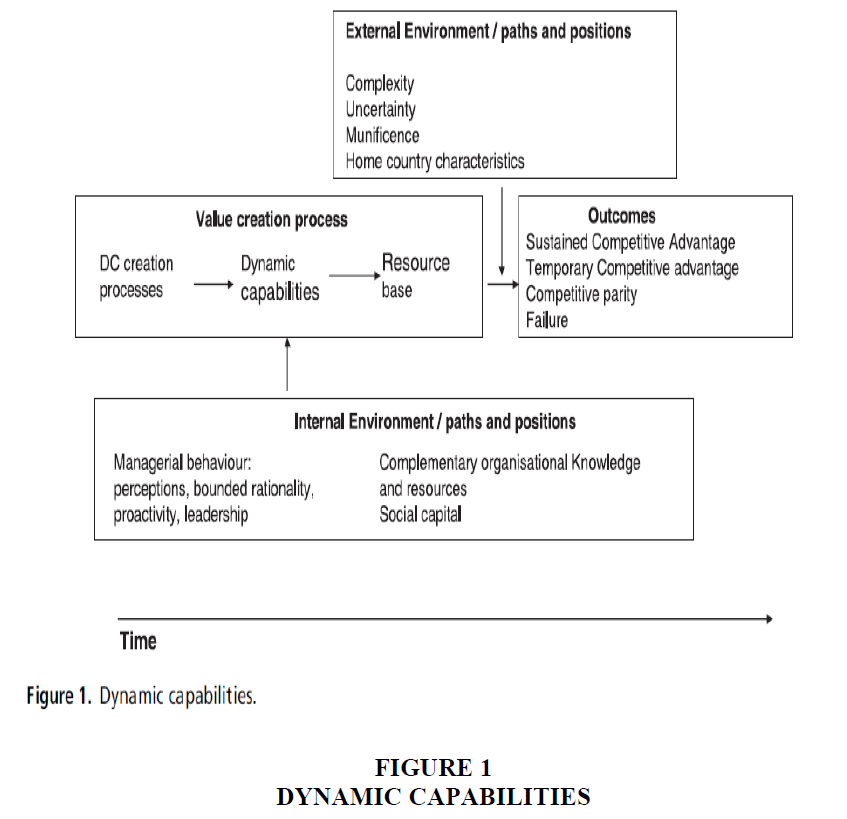

The deployment and performance of dynamic capabilities is moderated by a variety of internal and external variables, as depicted in Figure 1. The internal ‘paths and positions’ that have a moderating effect include managerial behaviours and perceptions, and the presence of complementary assets and resources. These internal paths and positions influence the deployment of dynamic capabilities. The external environment exerts a moderating influence, particularly on the linkages between the deployment of dynamic capabilities and competitive advantage. Dynamic capabilities impact firm value creation via their impact on the resource base. These impacts can result in competitive advantages which may be temporary or sustained, depending on the dynamism in the environment. It is possible, then, that resource-based advantages might be short-lived, owing to changes in customer and/or competitor behaviour. The dynamic capabilities enable the firm continually to refresh the resource stock so that the firm can continue to ‘hit a moving target.’

Dynamic Capabilities may be thought of as Falling in Three Categories

Sensing: Sensing refers to an organization’s capacity to continuously scan the organizational environment (Teece, 2007; Pavlou & Sawy, 2011). According to Teece, sensing refers to accumulating and filtering information from the environment ‘to create a conjecture or a hypothesis about the likely evolution of technologies, customer needs, and marketplace responses’ and ‘involves scanning and monitoring internal and external technological developments and assessing customer needs, expressed and latent’ Teece (2007), in addition to shaping market opportunities and monitoring threats. Some researchers have outlined that sensing does not only have an external focus but also has an internal aspect: It may, for example, involve the identification of new developments and opportunities within the firm. This theoretical difference between external and internal sensing is reflected in further developments of cognitive micro-foundations of sensing: Some scholars in the strategic management field (e.g., Helfat, 1997) have focused on perception and attention (i.e., a rather external perspective), while others Hodgkinson & Healey (2011) have mainly looked at the need for reflection/reflexion (i.e., a rather internal perspective). Nevertheless, Teece’s (2007) original conceptualization is more oriented towards the organization’s external environment. Refining Teece’s broad definition, an organization with high sensing capacity is able to continuously, and reliably acquire strategically relevant information from the environment, including market trends, best practices, and competitors’ activities.

Seizing: Seizing refers to developing and selecting business opportunities that fit with the organization’s environment and its strengths and weaknesses (Teece, 2007). Seizing thus means that market opportunities are successfully exploited and that threats are eluded. Seizing bridges external and internal information and knowledge, and it is closely linked with strategic decision making, particularly regarding investment decisions. Seizing capacity starts from a strategy that enables the recognition of valuable knowledge. This evaluation is based on prior knowledge, and it results in a selection from a variety of strategic options. Seizing capacity within an organization is high if the organization is able to decide whether some information is of potential value, to transform valuable information into concrete business opportunities that fit its strengths and weaknesses and to make decisions accordingly.

Transforming: Transforming, according to Teece (2007), includes ‘enhancing, combining, protecting, and, when necessary, reconfiguring the business enterprise’s intangible and tangible assets’, such that path dependencies and inertia are avoided. That is, transforming refers to putting decisions for new business models, product or process innovations into practice by implementing the required structures and routines, providing the infrastructure, ensuring that the workforce has the required skills, and so forth. Transforming is characterized by the actual realization of strategic renewal within the organization through the reconfiguration of resources, structures, and processes. Teece (2007) describes transforming (reconfiguring) as the ‘ability to recombine and to reconfigure assets and organizational structures as the enterprise grows, and as markets and technologies change’. Thereby, transforming is similar to Li and Liu’s implementation capacity, which is defined as ‘the ability to execute and coordinate strategic decision and corporate change, which involves a variety of managerial and organizational processes, depending on the nature of the objective.’ Implementing thus refers to communicating, interpreting, adopting, and enacting strategic plans (Noble, 1999). Only through implementation does renewal come into being; otherwise, new information and ideas within an organization remain theoretical inputs and potential changes. An organization with a high transforming capacity consistently implements decided renewal activities by assigning responsibilities, allocating resources, and ensuring that the workforce possesses the newly required knowledge.

Usefulness of Dynamic Capabilities in Busines

Alliancing as a Dynamic Capability

In the tradition of Teece (1990), and Kogut & Zander (1992) argues that building up alliances describes a specific capability, labelled as ‘alliancing capability’. In this contribution alliances are defined as cooperative agreements of any form aimed the strengthening of the position of the participating firms. Therefore alliances could have several different goals, e.g. access to new knowledge, risk sharing or the exploration of a new market. Especially since the mid 1990s there is a world-wide trend observable towards an increasing number of strategic alliances among corporations. Several research papers and books already raised the topic of ‘strategic alliances’. Set up alliances seems to be a strategic option to get access to specific assets of other corporations. Eisenhardt & Martin (2000) argue that alliancing is a dynamic capability itself because it opens new sources of experience and knowledge. Powell argue that in dynamic environments corporations try to get access to innovations through learning from partners. They figured out that ‘skills in managing collaborations’ are one success factor of alliances. Ofcourse, alliancing capability is not the success itself, but it enables corporations to gain advantage from their alliances. The corporation with a high alliancing capability uses alliances to exploit and explorate new knowledge which is necessary to secure its competitive position in the market.

Therefore, a higher alliancing capability enables the corporation to manage current alliances better and improves the chance to increase the absorptive capacity of a firm and gain competitive advantage from its alliances.

Dynamic Capabilities and Competitive Advantage

Torough & Adudu findings revealed that there was an established positive significant effect between dimensions of dynamic capabilities and competitive advantage of telecommunication companies in Nigeria. Their study further discovered that integrating capabilities (36.8%) contributed more to competitive advantage of telecommunication companies in Nigeria than seizing capabilities (20.7%), reconfiguration capabilities (16.1%), and strategic flexibility (12.3 %). Thus concluded that dynamic capability has a positive significant effect on competitive advantage of firms by enabling firm's access to, and ability to obtain, combine, and deploy resources in ways that adequately respond to their operating context thus constitute a route to achieving sustainable competitive advantage operating in more complex, turbulent and disruptive environment offering both threats and opportunities to firms, depending on the tangible and intangible resources they possess and how well they are able to utilize them in different ways. Torough and Adudu argued that the Telecommunication companies must be encouraged to adopt sensing capabilities.

Therefore, firms that are better at sensing opportunities and threats in the market are able to know and understand changing consumer needs and preferences and consequently grow their markets by constantly scan, search, and explore opportunities across technologies and markets.

Dynamic Capabilities as Moderator

Authors in their study find that dynamic capabilities had a statistically mediating effect on the relationship between strategic intelligence and the performance of commercial banks in Kenya. Their study recommended that commercial banks policy makers should consider restructuring their internal and external competitive strategies, by involving behavioural scientists to device better ways of achieving the intended competitive advantage that can lead to superior performance of their banks.

Therefore, a firms dynamic capabilities acts as a medium of acceleration between its strategic intelligence and its business performance.

Dynamic Capabilities as Digital Transformation

Dynamic capabilities support new strategic designs that contribute to improve the viability and the sustainability of the automotive sector such as the increasing pace of digital technology development which affects and brings major changes to all industries (Schwertner, 2017).The emergence of digital innovations is accelerating and intervening existing business models by delivering opportunities for new services. Particularly, the automotive sector is leading trends such as car sharing, connectivity, and self-driving, creating new business models. The digital transformation brings benefits for the automotive industry, among which the following can be highlighted: (a) improvements for the products adapted to customers demand; (b) development of new offers to multiple options from which customers can choose; (c) change in commercial strategies to sell a product, within time focusing on the customer experience; and (d) personalized attention, quality in terms of products and services. One of the greatest benefits that digital transformation brings to companies is the number of channels of interaction with customers, which allows them to obtain the necessary information about their requirements, preferences, and experiences. Customers can access information from any device with internet access, and in any language, which allows them to compare quality attributes, prices, and recommendations from other users or customers (Canfield & Basso, 2017). In this sense, customer satisfaction through digital transformation is oriented to give them information regarding whether the chosen company is doing the right thing to respond to their demands (Christensen et al., 2016).

Therefore, the capabilities that are generating increased added value could promptly develop a sustainable competitive advantage (Johnson, 2020).

Dynamic Capabilities for Social Enterprises

Social enterprises (SEs) have an increasingly important role in developing more equitable societies worldwide. The capabilities of SEs are an important driver of their performance. Absorptive capacity is an organization’s ability to absorb, assimilate, and apply knowledge which affects a SE’s performance indirectly via its marketing capabilities (Lee & Chandra, 2020). The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic enduringly affected the world; its implication on society will have long-lasting adverse effects. The pandemic allowed social entrepreneurs to form strategic partnerships, develop innovative solutions, and replicate at scale to advance social influence. Social enterprises require dynamic capabilities to provide renewal capability, continuous exploration of opportunities for innovation, and improvement of practices to remain competitive and achieve long-term commitment to its social mission (Mikalef & Pateli, 2017).

Therefore, the marketing capabilities of SEs mediates the relationship between its absorptive capacity and financial performance.

Dynamic Capabilities for Sustainable Supply Chain Ecosystem

Sustainable development involves companies on an individual, organizational and social level requiring the adoption of business models or innovations capable of privileging the co-creation of mutual value with a view to sustainability. From an organizational perspective, knowledge brokers, by making explicit their roles as mediators of interactions and acting on dynamic capabilities (DCs), can generate a proactive approach to the three dimensions of sustainability and specifically allows capabilities to positively impact the propensity toward sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) practices (Fait et al., 2023). In today's global economy, developing supply chain agility (SCA) and lean practices (LP) as resource-based view and dynamic capabilities are essential for firms to sustain their competitive advantage (CA) and enhance their operational performance (OP) (Manzoor et al., 2022). Dynamic capabilities and sustainable supply chain management are found to be connected by similar environmental and organizational conditions, thus making the application of dynamic capabilities concepts in the field of sustainable supply chain management a logical choice (Beske, 2012).

Therefore, most sustainable supply chains are situated in dynamic environments, which leads to the assumption that management of such chains requires the application of dynamic management theories, such as the dynamic capabilities (DC) concept.

Dynamic Capabilities of Pharmaceutical Organizations

Pfizer, Novartis and other top-ranking pharmaceutical organizations decided to move away from historical pharmaceutical small molecule products to large molecules biotechnology products. There has been a more recent leap towards gene therapy, the cutting-edge technology utilizing genetic modification to treat patients both in oncology and rare disease settings. Pfizer who is renowned for its vaccines sensed the change in the types of medicine and treatment for oncology and the unmet needs of rare disease, it quickly acquired a small gene therapy biotechnology company, Bamboo Therapeutic, in 2016 with rapid expansion as part of its acquisition vision. Novartis renowned for its deep pipeline of oncology drugs sensed the rapid growth in the gene therapy arena and acquired the gene therapy company, AveXis, in 2018. Both Pfizer and Novartis sensed the threat of medicines going off patent as well as the trajectory in different treatment plans for oncology patients and rare diseases. They both had to seize the opportunities either to acquire organizations using cutting edge technology such as gene therapy and reconfigure their areas of expertise by way of mergers and acquisitions. Divestment of their portfolios was a strategic effort on the part of both Pfizer and Novartis to ensure both entities could remain competitive and solvent.

Therefore, in a changing environment, the most important factor for successful adaptation is the ability to identify and implement new learning, new kinds of knowledge and new organisational processes, but that this will only happen where the firm’s perceptions of future opportunity support such a strategy.

Results and Findings

Advantages of DC Firms

1. A higher alliancing capability enables the corporation to manage current alliances better and improves the chance to increase the absorptive capacity of a firm and gain competitive advantage from its alliances.

2. Firms that are better at sensing opportunities and threats in the market are able to know and understand changing consumer needs and preferences and consequently grow their markets by constantly scan, search, and explore opportunities across technologies and markets.

3. A firms dynamic capabilities acts as a medium of acceleration between its strategic intelligence and its business performance.

4. The capabilities that are generating increased added value could promptly develop a sustainable competitive advantage.

5. The marketing capabilities of SEs mediates the relationship between its absorptive capacity and financial performance.

6. Most sustainable supply chains are situated in dynamic environments, which leads to the assumption that management of such chains requires the application of dynamic management theories, such as the dynamic capabilities (DC) concept.

7. In a changing environment, the most important factor for successful adaptation is the ability to identify and implement new learning, new kinds of knowledge and new organisational processes, but that this will only happen where the firm’s perceptions of future opportunity support such a strategy.

Conclusion

The assumption that the companies need dynamic capabilities to compete and only companies with dynamic capabilities have a chance to build competitive advantage somewhere proofs to be true. There are several good examples of the effects of dynamic capabilities in the PBI. Gillespie detailed the collaborative efforts of Pfizer, Novartis, Takeda, Johnson & Johnson, Astra Zeneca, Sanofi and Merck to name a few multinational global pharmaceutical biotechnology companies. Many of these organizations had to use Open Innovation, going as far as setting up global platforms to support research and development while forming affiliations and consortiums with academia. Furthermore, use of social media platforms, crowdsourcing and outsourcing became the new age way of doing business in the 21st century.

Limitations

There is no unified conceptual definition of the dynamic capabilities and the primary focus of its concept remains to a large extent theoretically undefined and need more attention in future research.

Research Implication/ Future scope of work

It would be interesting to ascertain if there are different types of dynamic capability, innovation capability and entrepreneurial capability; such variety could explain, the different strategic actions that firms pursue in their respective industries.

References

Arend, R.J., & Bromiley, P. (2009). Assessing the dynamic capabilities view: spare change, everyone?. Strategic organization, 7(1), 75-90.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of management, 17(1), 99-120.

Beske, Philip. (2012). Dynamic Capabilities and Sustainable Supply Chain Management. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management. 42. 372-387. 10.1108/09600031211231344.

Canfield, D.D.S., & Basso, K. (2017). Integrating satisfaction and cultural background in the customer journey: A method development and test. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 29(2), 104-117.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Christensen, C. M., Hall, T., Dillon, K., & Duncan, D. S. (2016). Know your customers’ jobs to be done. Harvard business review, 94(9), 54-62.

Di Stefano, G., Peteraf, M., & Verona, G. (2010). Dynamic capabilities deconstructed: a bibliographic investigation into the origins, development, and future directions of the research domain. Industrial and corporate change, 19(4), 1187-1204.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Eisenhardt, K.M., & Martin, J.A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: what are they?. Strategic management journal, 21(10‐11), 1105-1121.

Fait, M., Palladino, R., Mennini, F. S., Graziano, D., & Manzo, M. (2023). Enhancing knowledge brokerage drivers for dynamic capabilities: the effects on sustainable supply chain ecosystem. Journal of Knowledge Management.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Furrer, O., Thomas, H., & Goussevskaia, A. (2008). The structure and evolution of the strategic management field: A content analysis of 26 years of strategic management research. International journal of management reviews, 10(1), 1-23.

Helfat, C.E. (1997). Know‐how and asset complementarity and dynamic capability accumulation: the case of R&D. Strategic management journal, 18(5), 339-360.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hodgkinson, G. P., & Healey, M. P. (2011). Psychological foundations of dynamic capabilities: Reflexion and reflection in strategic management. Strategic management journal, 32(13), 1500-1516.

Johnson, H. (2020). The moderating effects of dynamic capability on radical innovation and incremental innovation teams in the global pharmaceutical biotechnology industry. Journal of Innovation Management, 8(1), 51-83.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization science, 3(3), 383-397.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lee, E.K.M., & Chandra, Y. (2020). Dynamic and marketing capabilities as predictors of social enterprises’ performance. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 31, 587-600.

Leonard‐Barton, D. (1992). Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. Strategic management journal, 13(S1), 111-125.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lockett, A., Thompson, S., & Morgenstern, U. (2009). Reflections on the development of the RBV. International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(1), 9-28.

Manzoor, U., Baig, S. A., Hashim, M., Sami, A., Rehman, H. U., & Sajjad, I. (2022). The effect of supply chain agility and lean practices on operational performance: a resource-based view and dynamic capabilities perspective. The TQM Journal, 34(5), 1273-1297.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mikalef, P., & Pateli, A. (2017). Information technology-enabled dynamic capabilities and their indirect effect on competitive performance: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Journal of Business Research, 70, 1-16.

Nelson, R. R. (1985). An evolutionary theory of economic change. harvard university press.

Noble, C.H. (1999). The eclectic roots of strategy implementation research. Journal of business research, 45(2), 119-134.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pavlou, P.A., & El Sawy, O.A. (2011). Understanding the elusive black box of dynamic capabilities. Decision sciences, 42(1), 239-273.

Penrose, E.T. (1952). Biological analogies in the theory of the firm. The american economic review, 42(5), 804-819.

Priem, R. L., & Butler, J. E. (2001). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research?. Academy of management review, 26(1), 22-40.

Rindova, V. P., & Kotha, S. (2001). Continuous “morphing”: Competing through dynamic capabilities, form, and function. Academy of management journal, 44(6), 1263-1280.

Schwertner, K. (2017). Digital transformation of business. Trakia Journal of Sciences, 15(1), 388-393.

Teece, D. (1990). Firm capabilities, resources and the concept of strategy. Economic analysis and policy.

Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic management journal, 28(13), 1319-1350.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wang, C. L., & Ahmed, P. K. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: A review and research agenda. International journal of management reviews, 9(1), 31-51.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Weerawardena, J., Mort, G. S., Liesch, P. W., & Knight, G. (2007). Conceptualizing accelerated internationalization in the born global firm: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Journal of world business, 42(3), 294-306.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zahra, S.A., Sapienza, H. J., & Davidsson, P. (2006). Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: A review, model and research agenda. Journal of Management studies, 43(4), 917-955.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zollo, M., & Winter, S. G. (2002). Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organization science, 13(3), 339-351.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 20-Jan -2024, Manuscript No. jmids-24-14481; Editor assigned: 22-Jan -2024, Pre QC No. jmids-24-14481(PQ); Reviewed: 29- Jan-2024, QC No. jmids-24-14481; Revised: 18-Nov-2023, Manuscript No. JMIDS-24-14481(R); Published: 31-Jan-2024