Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 1

Customer Experience, Social Regard and Marketing Outcome (Satisfaction and Loyalty): Sub Saharan Oil Marketing Companies Perspective

Atia Alpha Alfa, University of Professional Studies

Ebenezer Addae, University of Professional Studies

Winston Asiedu Inkumsah, University of Professional Studies

Robert Yaw Amponsah, University of Professional Studies

Abstract

This study investigates by appreciating what customer experience entails as well as whether social regard impacts the relationship between customer experience and marketing outcomes. Utilizing an experience survey method because of the study’s focus, 524 out of the 650 respondents were found usable for the analysis after after using a convenience sampling approach to collect the responses. The findings confirm that customer experience is explained by such dimensions as employees, core service, value addition, speed and marketing mix. This is reflect by the positive and significant relationship which was shown in the findings to the effect that customer experience is explained by the above dimensions. Further, in assessing the direct influence of the higher order construct (customer experience) on such marketing outcomes as behavioural loyalty and satisfaction, the findings indicated a positive and significant relationship. Also, the results also established a link between satisfaction and loyalty behaviour although prior studies had questioned the nature of the relationship because although improved customer satisfaction is desirable it is not a sufficient basis for consumers exhibiting loyalty behaviour. The research as well illustrates that customer experience affects behavioural loyalty via social regard. The results have implications for academia and business practitioners.

Keywords

Customer Experience, Satisfaction, Social Regard, Loyalty, Oil Marketing Companies.

Introduction

Organizations in today’s hypercompetitive environment realize that to be outstanding, a thorough understanding of the customer is critical. Towards this end, these organizations are coming to terms with the fact that today’s customer is one who is time staffed and demanding and require more than just problem-solving properties of goods and services which offer functional benefits (Keller, 2013). To this end, most organizations are understanding that their marketing offering are similar in functionality and consumers demand more than functionality (Haeckel et al., 2003). As a result, organizations are linking the above thought to strategies and tactics which can be utilized to create lasting customer experiences (Skorupa, 2015). Building such lasting customer experiences has now captured attention and according to Lemon & Verhoef, (2016) is management’s foremost intent to achieve. Gartner (2016) supports the above, when they suggested that 89% of organizations expected to compete on experience. That is, their basis for remaining competitive is through creating superior value for customer which is achieved through service experience (Kotler & Keller, 2014). In the meantime, most customer-oriented companies are graving for a shift from a good centered logic to service centered logic (Vargo & Lusch, 2004) with focus on the process of exchange and value in use. However, the latter is confronted with the issue of separating services from the customer and not taking into consideration the experiences the customer has with the product (Schembri, 2006).

Whereas attention continues to be given to customer experience, thus far, no conclusive agreement has been reached as to what customer experience encompasses, because of its novel nature (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). To date, the approaches used to evaluate what it entails are inadequate (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). For instance, the assessment of customer experience using empirical data that are not gathered from the end user of an offering at the time of buying limits appreciation of the moment of truth between the end user and the service institution (Stein & Ramaseshan, 2019). It further avoids the fact that consumers have multiple experiences on the consumer path at various points in the consumption journey. In addition, scholars such as Babin et al. (1994) assert that customers typically respond and behave differently based on the purpose and goal of their actual shopping behavior. For instance, the real significance of the different customer experience moments of truth could vary for customers who engage in the consumption process due to the need to access information or purchase a market offering as against buyers who extend their stay at a retail environment even after acquiring what they desire, interact with other buyers and take part in other activities which is seen as experience filled because quality of the offering, speed of delivery, marketing mix activities as well as the genuine respect, deference and interest shown to customers by the service provider such that the customer feels valued or important in the social interaction. Based on the above, Stein & Ramaseshan (2019) asserts that should marketers ignore such among customers at the time of experience, it can limit appreciation of what customer experience entail.

De Keyser et al. (2015) asserts that customer experience

“Comprised of the cognitive, emotional, physical, sensorial, spiritual, and social elements that mark the customer’s direct or indirect interaction with (an)other market actor(s)”.

These researchers emphasize that academics have built robust approaches that includes several methods that assist in comprehending and managing customer experience (De Keyser et al., 2015; Klaus, 2014). Further, the scholars argue that despite the use of such visualization approaches like, customer journey mapping, service blueprinting, and customer experience mapping that can assist to create better insight into customer experience, in practice they are often created for specific consumer groups on the basis of their personality (Manning & Bodine, 2012). Hence, the need for further study, broadening the scope of customer experience measurement for other approaches such mobile real-time experience tracking approach, biometrics, eye tracking, EEG and fMRI-scan to ascertain customer experience (Venkatraman et al., 2012;) other than those that majorly relied on information gathered from traditional post-purchase surveys and interview (Stein & Ramaseshan, 2019; Macdonald et al., 2012; Kumar et al., 2014). The sparse nature of research that employed for instance mobile real-time experience tracking approach to ascertain customer experience (Baxendale et al., 2015) are scarce despite the fact that such methods examined the effects of moments of truth on variables such social regard, quality of the offering, speed of delivery, marketing mix activities.

One sector which has contributed significantly to Ghana’s economic growth is the oil and Gas sector. Statistically, Ghana’s 8.5% growth is predominantly oil driven with non- oil growth representing 4.9% (GSS, 2017). The industry is categorized into upstream and downstream sector. While the upstream sector is made up of exploration, development and production of crude and natural gas; the downstream sector comprises refining, storage, internal transportation, marketing and sale of petroleum products including petrol, diesel, LPG and Kerosene (Ghana Energy Commission, 2006).

The downstream sector traces its origin back to colonial times when foreign brands such as Shell, Mobil and Total imported, distributed and sold their products in the country. These OMCs built service stations at strategic locations in the country for sale and distribution of petroleum products. The sale of products at these service stations was performed by customer service attendants. As well, these companies also offered lubricants, care products, car wash bays and sale of groceries/convenience goods (Total Ghana, 2020). As such all these stations are an integral part of the retail trade sector.

The gasoline stations subsector is part of the retail trade sector. Industries in the Gasoline Stations subsector retail automotive fuels (e.g., gasoline, diesel fuel) and automotive oils or retail these products in combination with convenience store items. In recent years, the number of companies making up OMCs have grown substantially from 40 in 2010 to 95 in 2017 (NPA, 2017). Despite the growth in the numbers, 21.5% of the total are considered as inactive basically because of indebtedness and lack of competitiveness making these businesses not been profitable (Graphic Online, 2017) because customers are quickly turned off by long waits at pumps or queues in stores, a dirty pump handle or overflowing bins at forecourt (GfK, 2016). However, OMC’s such as GOIL, Total and Shell amongst others have remained consistent in their growth as a result of their ability to differentiate themselves by creating unique customer experience that accompany their products and service. For instance, Total Ghana have achieved competitiveness by helping clients to make the right choices, so that their experience at the pump and within the shop will be quick, safe and easy. As well they dominate the roadsides and their service area and their retail offer have changed significantly this last decade.

In spite of these limited successes, they are faced with the challenge of creating lasting experiences based on proper identification of specific variables that influence experience utilizing the appropriate methods. Hence, this study suggests a model focused on recognizing that consumers have experiences every time they encounter the marketing offering of oil marketing companies at varied touch points. The model assesses: the dimensions that explain the structure of experience at oil marketing companies in Ghana, the effect of customer experience on marketing outcomes such as satisfaction and loyalty behavior. Also, the relationship between satisfaction and loyalty will be examined. In addition, how the effect of customer experience is mediated by social regard, with real-time customer experience data that were captured by using sampling methodology (ESM) via a mobile mechanism (Stein & Ramaseshan, 2019).

This study is divided into several sections. First, a brief review of main concept of interest is provided. Also, the study’s model and the hypothesis are developed. Next, the research methodology used for this study is presented, followed by presentation and discussion of results. Finally, the article concludes with main findings and recommendations.

Literature Review

Explaining Experience

The concept of experience which has existed and continue to stimulate interest for the past three decades is proliferated with several insights. This concept has been explained as a key ingredient of service offering and service design (Zomerdijk & Voss, 2010) and as such an essential concept of the service-dominant logic, which views the concept which Holbrook and Hirchman characterized as experiential and phenomenological as the basis of all business (Vargo & Lusch, 2008). Its evolution is as a result of the fact that earlier underpinnings of marketing which focused on features and benefits no longer emotively solved the challenges of customers (Schmitt, 1999). Factors such as information technology influencing experiences; service arena becoming competitive; consumers becoming more empowered and finally growth and influence of brands (Knutson et al., 2007; Keller, 2013) is also alluded to orchestrating this development. This has led to a change within the business environment as shown by several insights of experience. For instance, Mossberg (2007) defines it as “a constant flow of thoughts and feeling that occur during moments of consciousness”. Also, it is a state of being physically, emotionally, socially, or spiritually engaged with an activity (O’Sullivan & Spangler, 1998). Pine & Gilmore (1999) who are proponent further views it as a distinct economic offering that customer finds unique, memorable and sustainable overtime and would want to repeat and build upon and enthusiastically promote via word of mouth. The above is in agreement with Olsson et al. (2012) who view experience as the final phase of economic progression where service providers focus on staging unforgettable memories. Further, Gupta & Vajic (1999) views this concept as any sensation or knowledge acquisition resulting from some level of interaction with different elements of a context created by a service provider. Finally, Bustamante & Rubio (2017) sums it all up when they claim that within the retail space, experience results from collaboration and an “act of co-creation” between the retailer, (inclusive of his/her employees, environment, policies and practice) and the customer (subject).

From the above insights about the concept of experience scholars have characterized it as an interactive phenomenon (Jain & Bagdare, 2009) as well as based on processes and on outcomes (Helkkula, 2011). With respect to process-based experience, physical elements are used prior to main emotive and social encounter whereas outcome-based experience involves elements bound together to arrive at the concept of experience (Helkkula, 2011). Further, the above insight also indicates that experiences are personal and exceptional; it consists of perception and participation of customers; emotionally and socially involves stakeholders and not just a single individual (Helkkula, 2011), are shared with others and are memorable and sustainable overtime (Cetin & Dincer, 2014). The above characteristics explains the concept of experience and its measurability.

From a business perspective, firms have a myriad of options on how to introduce experiences to customers. Knutson et al. (2007) argue that firms can create the marketing offering to express the experience or the offering can be seen as the experience itself. Instinctively, in creating such an experience, the aim should be that all resources and activities are aligned such that a total package of sort is envisaged. With the above, more value is created for all stakeholder in the form of experiences (Knutson et al. 2007). Despite this insight, the customers’ perspective of the concept of experience is also rive with several interpretations and as such research seem to be limited as to what customer experience entails (Palmer, 2010).

Customer Experience Defined

In recent times the concept of customer experience has not only attracted the attention of academics and practitioners, but as well has been envisaged as an important criterion in support of business growth (Garg & Rahman, 2014). Despite this feat, the last four decades of its existence has seen several researchers making in-roads as to what this concept is all about. Cross section of the various definitions are provided briefly in Table 1. The themes from the various explanations are that, customer experience initially is an emotional, social, or spiritually bond not only between a single individual customer and the organization but as well “on the aggregated service experience of multiple respondents” and the firm. Also, it is internal and subjective to the customer in their interaction with the firm. In addition, the concept can be created by controllable (service interface, atmosphere, assortment, price, etc) and uncontrollable elements (influence of consumers or devices like smart phones (McColl-Kennedy et al., 2015). And finally, it is holistic in nature and is location and time bound.

| Table 1 Cross Section of Definitions of Customer Experience | |

| Author | Definition of Customer Experience |

| (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982) | “Fantasy, feelings and fun” achieved through consumption of a marketing offering. |

| Pine & Gilmore (1998) | “Experiences are a distinct economic offering, as different from services as services are from goods. An experience occurs when a company intentionally uses services as the stage, and goods as props, to engage individual customers in a way that creates a memorable event”. |

| Schmitt (1999) | “Result of encountering, undergoing, or living through situations. They are triggered stimulations to the senses, the heart, and the mind. Experiences also connect the company and the brand to the customer’s lifestyle and place individual customer actions and the purchase occasion in a broader social context. In sum, experiences provide sensory, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and relational values that replace functional values” |

| Bergmann (1999) | “Experience is specific knowledge that has been acquired by and agent during past problem solving. Experience is therefore always situated in a certain, very specific problem solving context. Therefore, experiences are stored knowledge” |

| McCarthy & Wright (2004) | View experience based on what they referred to as the four threads of experience, ideas that help us to think more clearly about technology as experience: the sensual, the emotional, the compositional, and the spatio-temporal. |

| Grewal et al. (2009) | Customer experiences can be categorized along the lines of the retail mix (i.e., price experience, promotion experience). |

| Verhoef et al. (2009) | Customer experience is “holistic in nature and involve(ing) the customer’s cognitive, affective, emotional, social and physical responses to the retailer. This experience is created not only by those factors that the retailer can control (e.g. service interface, retail atmosphere, assortment, price), but also by factors outside of the retailer’s control (e.g. influence of others, purpose of shopping)” |

| Brakus et al. (2009) | CE is conceptualised as subjective, internal consumer responses (sensations, feelings, and cognitions) and behavioral responses evoked by brand-related stimuli that are part of a brand’s design. |

| Lemke et al. (2011) | Customer experience is recognized as the internal and subjective response customers have to any interaction with a company |

| Bolton et al. 2014 | defined as holistic in nature, involving the customer’s cognitive, affective, emotional, social and physical responses to any direct or indirect contact with the service provider, brand, or product, across multiple touch points during the entire customer journey |

| De Keyser et al. (2015) | describe customer experience as “comprised of the cognitive, emotional, physical, sensorial, spiritual, and social elements that mark the customer’s direct or indirect interaction with (an)other market actor(s)” |

From the themes above this study also suggest that this multidimensional concept thrives not only on the empowered customer but as well requires an all hands-on deck for a co-created experience to persist. But this experiential and phenomenological concept also introduces some critical points such as what are the dimensions of customer experience? How do we measure it ?. Does customer experience affect positive or negative word of mouth?

Experience at the Fuel Station

Factors such as spatial variability in in retail gasoline markets, logistics planning, legacy processes, IT, rapidly evolving payment landscape indoor and outdoor have been adduced as constituting the overall reasons why OMC (Fuel stations) have struggled to offer consistent and personalized consumer experience globally (Xu & Murray, 2019; Seemann, 2019; Pileliene & Bakanauskas, 2016; McPherson Oil, 2017). This is no difference here in Ghana, coupled with the fact that customer service has been thrown to the dogs although adherence to customer service practices has immense impact on experiences customer leave the pump with (Bueno et al., 2019; Mensah-Keli, 2016). This notwithstanding, OMC are much in the reckoning of their branding and corporate image of their stations and retreating to their core mandate refueling, in addition to the retailing angle they have reinvigorated (Bever Innovation, 2015).

Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

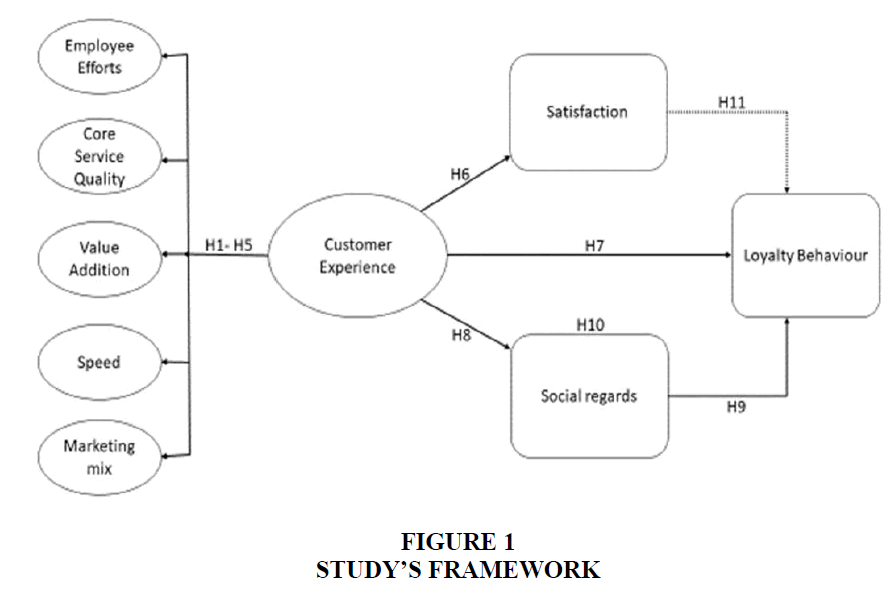

The theoretical model (Figure 1) proceeded from left to right, beginning with the five dimensions explained below (employee efforts, core service quality, value addition, speed and marketing mix) that could explain customer experience; and from there the direct effect goes to satisfaction and loyalty behavior. Then social regard is introduced as having a direct effect as well as a mediator on the link between a higher-level construct (customer experience) and loyalty behavior. Finally, the relationship between satisfaction and loyalty behavior is ascertained.

Dimensions of Customer Experience

This study’s focus on oil marketing companies is not business as usual of only studying tangible environments of retailing oil products (Machleit & Eroglu, 2000; Berry et al., 2005). But because there is little to no research in the oil marketing research relative to identifying what constitutes the dimensions of customer experience. Also as shown above oil marketing companies are increasingly recognizing the essence of creating experiential value for customers.

Several scales have been developed which have exposed the various dimensions that make up the concept of customer experience. For instance, in their post consumption experience of bank customers study, Grace & O’Cass (2004) indicated that the effects of core service, employee service and services cape was critical in triggering satisfaction and change in consumer attitude towards a brand. Also, in the hospitality sector, a seven-factor scale which include such variables as environment, benefit, accessibility, convenience, utility, incentive and trust was created by Knutson et al. (2007) to measure customer experience. The above set of variables were validated and used to develop the all-important customer experience index (Kim et al., 2011). In addition, studies by Brakus et al. (2009) also introduced such variables as sensory, affective, intellectual and behavioural which had an outcome on satisfaction and loyalty. However, this study seem to be in agreement with Garg & Rahman (2014) study which is of the view that most of the variables within the scales developed by distinguished researchers and is reflective of customer experience combines it with service quality and as a result have relied on the infamous Servqual developed by Parsuraman et al. (1988) which limits the status of the current empowered customer as passive who just process the information and later assess the service interaction as a resultant outcome. But today’s co-created marketing space which has seen the cooperation that exist between the service firm and the customer (Gonzalez-Mansilla et al., 2019) had called for further empirical studies which will introduce multidimensional scale which will help appreciate this all-important concept of customer experience (Garg & Rahman 2014).

In this study, both controllable and uncontrollable dimensions (which include employees, core service, value addition, speed, marketing mix, social regard among others) used to measure customer experiences but in the banking industry and SME sector (hairdressing, cafes and naturopaths) (Garg & Rahman, 2014; Butcher, 2003), which is not this study’s focus is used in the OMC (Fuel Station) context. As well, instead of looking at the reflective nature of the dimensions, this study makes a case to the effect that, customer experience is a higher order construct and the dimensions as above are lower order constructs.

Employees

Employees are co-value creators who help remedy loneliness (Stone, 1954). In other words, they are frontline staff who often engage with customers on a personal, emotional level to offer support (Fisk et al., 2011). The intuitive relationship between customer's perceptions of employee effort and customer experience is the more the customer perceives employees’ efforts the better the customer experience (Yani-de-Soriano et al., 2019). Evidence from research shows that customers’ perceptions of employees’ positive behavior in the service delivery and recovery encounter influences their customer experience outcome (McQuilken et al., 2013). How the firm’s staff treats customers during the service delivery and recovery process, including their courtesy and empathy (Tax et al., 1998) and the sensitivity and effort with which they try to solve the problem (Del Río-Lanza et al., 2009), affects customers’ overall experience (Yani-de-Soriano et al., 2019). Studies have shown that customer’s frequent outlets such as retail shops because of the life-enhancing, social supportive experience they get from staff of such outlets (Sheu et al., 2009; Fisk et al., 2011). But the above does not mean that every staff willingly doles out relational experiences to every customer or managers can even control the propensity to do so. Thus, from the discussions above, the study hypothesizes that:

H1: Customer experience is positively characterizes by Employees effort

Core Service Quality

The quality construct is proliferated with several meanings. But scholars agree that quality should be defined from the customer’s perspective (Rowley, 1999). A quality service has to be one which meet and exceeds customer’s expectation (Malik et al., 2020). Several studies have ascertained service quality by evaluating the difference existing between perceive performance and expectation (Parasuraman et al., 1988). Two types of service quality are known in literature, namely functional service quality and technical service quality (Gronroos, 1984). While functional quality defines the way benefits of an offering is delivered to the end user with the right employee behavior (“attitudes and friendliness”) and as well assesses the influence of the functionality of the service firm’s environment (Yilmaz & Ari, 2017). On the other hand, Chou & Kim (2009) explain technical quality as premised on the firm’s perception and highlights the service process and the way in which the service is offered and what the customer gets. Because, positioning yourself adequately in today’s competitive business environment is precedent on the quality of your core service (Walter et al., 2010). Several studies have associated customer perception of core service quality to desirable benefits (Butcher, 2003). Gronross (1990) for instance, argued for functional and technical quality dichotomy as a way to ascertain core service quality factors and relational activities. Marketers attempt to maximize a customer's perceived value because it is one of the most influential factors in the purchasing decision and is an antecedent of satisfaction and loyalty (Cronin et al., 2000; Koller et al., 2011; Parasuraman & Grewal, 2000). However, in a study by Iacobucci et al. (1994) in the health sector, it became vivid that delight was achieved as a result of core service quality or staff attitudes being good. Also, other studies have discovered that where service quality is higher customer experience is also higher (Tsaur et al., 2005; Nakayama & Wan, 2019). Hence, from the discussions above, the study hypothesizes that:

H2: Customer experience is positively characterizes by core service quality

Value Addition

Value is observed as a critical concept within the relationship marketing space and a firm’s tenacity to offer distinguishing services to customers is seen as a ‘sine qua non’ to business success (Ravald & Gronroos, 1996, Heskett et al., 1994). Value addition or added value (de Chernatony et al., 2000) presents varied meanings. It is the underlining theme to brand definition and a basis for distinguishing a product from a brand (de Chernatony et al., 2000). Gronroos (1997) offered a distinction between value and added value when he asserted to the effect that a product/service’s core value is the core solution and the added value is its addition services. The latter is what Levitt refers to as “augmentations”, adding things the customer had never thought about but are important and relevant. This is agreement with de Chernatony & McDonald (1998) who explained value addition as the attributes that are both relevant and welcome by customer. Hence, all the complements and extras which comes with the core services and leaves the customer with a desirous delight constitute the value addition. For instance, a firm’s ability to handle complaint and offer variety of service in addition to its core mandate was seen as critical to delighting bank clients in a study by Garg & Rahman, (2014). In addition, the generation of superior customer experience partly depends on value added to services or goods (Blocker et al., 2012; Echchakoui, 2016). Further, propositions from de Chernatony et al., (2000) was to the effect that this multidimensional variable made up of functional and emotional benefit as perceived by the customer as well offers the firm some advantages. Thus, from the discussions above, the study hypothesizes that:

H3: Customer experience is positively characterizes by value addition

Speed

Service delivery thrives on responsiveness and communication (Parasuraman et al., 1985). Responsiveness entails the speed of the service (Parasuraman et al., 1985), e.g. whether the oil marketing company (gas station operator) will provide prompt service to consumer of the service. In a study on online service delivery by Ding et al. (2011) it became evident that service speed was an important basis for evaluation. Formally, speed is explained as the urgency that a service firm exhibits while engage in delivering the desired experience for the customer as against his or her requirements (Jain & Bagdare, 2009). Speed can be particularly relevant in enhancing customer experience evaluation (Eisingerich & Bell, 2006; Fernandes & Pinto, 2019). For instance, in a study by Yang et al. (2015), it was concluded that the “service delivery process influences satisfaction in terms of speed and interaction frequency”. Again, speed is seen as critical to effecting business and customer interaction (Sheng, 2019). Thus, from the discussions above, the study hypothesizes that:

H4: Customer experience is positively characterizes by speed

Marketing Mix

Marketing mix is seen as a framework of transaction marketing and the origin for marketing success (Gronross, 1994). Although limited studies exist on the outcomes as well as the beneficence of these controllable variables to business success, there as well exist some studies which concludes that the mix is indeed a toolkit that businesses use in creating experiences and other benefits (Constantinides, 2006). This is in alignment with Coviello et al. (2000) who claim that the mix help to deal with tactical/operational marketing activities. Constantinides (2010) further argue that the marketing mix strategies of the controllable elements are structured such that it will meet the customer’s requirement. To a large extent it reflect how customers behave as well as decide on offering to purchase to satisfy their desires. Should their perception, behavior, expectation be positive or negative, it will have a

“Pervasive influence on as well attracting new customers and retaining existing customers” (Yelkur, 2000).

Thus, from the discussions above, the study hypothesizes that:

H5: Customer experience is positively characterizes by marketing mix

Customer Experience and Outcomes (Satisfaction and Loyalty)

Customer satisfaction and loyalty have been shown by studies as an essential outcome of customer experience (Caruana, 2002). Shankar et al. (2003) agrees with the above when they claimed that experience influences satisfaction which further drives loyalty behavior. Satisfaction is defined here as

“An ongoing evaluation of the surprise in a product acquisition and/or consumption experience” (Anderson & Srinivasan, 2003).

Loyalty behavior is explained as

“A commitment to repurchase a preferred product or service in such a way as to promote its repeated purchase” (Cossio-Silva et al., 2016).

Despite the link between the two marketing outcomes, there seem to be indifference as to the exact nature of this relationship, because whereas a study by McDougall &Levesque (2000) questioned the nature of the relationship because for them although improved customer satisfaction is desirable it is not a sufficient basis for consumers exhibiting loyalty behavior. On the other hand, Klaus & Maklan (2013) study found that there is a link between satisfaction and loyalty behavior which is in agreement with Keisidou et al. (2013) claim of the existence of a positive relationship. Hence, based on the above discussion this study hypothesizes the following:

H6: Customer experience would have a positive relationship with satisfaction

H7: Customer experience would have a positive relationship with loyalty behavior

H11: There is a likely relationship between satisfaction and loyalty behavior

Social Regard

The essence of the social-psychological aspect to the service process is seen as important for most services where client and staff interaction is high (Butcher & Heffernan, 2006). The above observation is valid given the fact that social-psychological methods is been used in several studies (Butcher & Heffernan, 2006). For instance, perceived control, social justice, social norm, interactional justice, social regard among others have been used to study the variations in service evaluation and outcomes (Larson, 1987; Hui & Zhou, 1996; Collie et al., 2000; Butcher, 2003; Butcher & Heffernan, 2006). All these social-psychological methods traces to the social influence theory which addresses the interaction between a customer and the service provider. For this study, our interest is in social regard which is explained by Butcher (2001) as

“The genuine respect, deference and interest shown to customers by the service provider such that the customer feels valued or important in the social interaction”.

SR is supported within the literature in that as indicated by researchers being respectful or the lack of it have resulted in customers being delighted and exhibiting repeat purchase behavior. This is supported by Aaker (1991) who claim that firms that live lasting impressions that trigger satisfactory outcomes avoid being disrespectful.

However, there exist limited empirical research that have ascertained the influence of social regard on loyalty. Earlier studies have only looked at how the service provider have behaved rather than how the customer felt (Butcher & Heffernan, 2006). For example, findings from a study by Brown et al. (1996) depicts the above where their work indicated that within the service failure setting, positive employee behavior increased service encounter satisfaction. Despite the above result, when Clemmer & Schneider (1996) studied the influence of interactional justice following a service failure their findings was at odds in that it had a weak effect on overall satisfaction. That notwithstanding, Blodgett et al. (1997) in their study which used a four-item scale to explain interactional justice found that the above social-psychological method had a positive effect on loyalty behavior but a negative effect on word of mouth. Till date only Butcher (2003) and Butcher & Heffernan (2006) have ascertained whether customers felt regarded following an experience of waiting in a queue. Their findings indicated that social regard had a “greater predictive power on satisfaction”; loyalty behavior and positive word of mouth. This study’s point of departure is the fact that their work was in a café setting which is not the focus of this research. Hence the postulation of the following hypothesis:

H8: Customer experience would positively affect social regards

H9: Social regards would positively affect loyalty behavior

H10: Social regard would positively mediate customer experience and the resulting outcomes of loyalty behavior

Methodology

To empirically ascertain the hypothesis postulated and accomplish the purpose set for the paper, an experience sampling methodology was utilized to gain true appreciation of customer experience at the various oil marketing companies. This method was used to collect quantifiable and real time data (Osei-Frimpong, 2017) from customers who patronize OMC (fuel Station) products and services within the Ghanaian setting. Because the study was on the understanding the dimensions and outcomes of customer experience at fuel stations (OMC), that is how come the customers of these fuel stations were the population of interest. ESM studies commonly use automated research instruments with at least one longer questionnaire to assess constant personal or environment variables along with shorter questionnaires for momentary repeat-measure results (Fisher & To, 2012). Through an online survey link sent to respondent’s personal handheld device, instant consumer experience data and real-time feedback were captured before, during and after decision journey (Stein & Ramaseshan, 2019). Research interns were briefly accessed from University of Professional Studies, Accra and trained to administer and collect data from staff of Zoom Lion Ghana limited across the sixteen regions of Ghana, who patronize fuel station offerings. The rationale was because it was a convenient approach to assess respondent for data collection.

Burns & Bush (2010), in defining population, consider the entire group under study in line with the specified goals of the research work. For the current study, the diverse staff of Zoom Lion Ghana Limited who own vehicles was the study population out of which the respondents will be conveniently selected. “A sample is the section of a populace that is chosen for examination” (Bryman & Bell, 2007). Bryman & Bell (2007) elucidates that, likelihood testing is the point at which every unit in the populace has an equivalent chance of being selected, while non-likelihood use human judgment in the choice procedure of an example.

Other scholars argue that that, with non-likelihood testing, it depends on the judgment of the scientist, suggesting that a sample is made up of elements that are highly representative of the population in terms of characteristics and attributes (Hair et al., 2012). Accordingly, a sample size of 650 made up of male and female staff of Zoom lion Ghana Limited aged between 18-60years was used for this study.

According to Tabachnick & Fidell (1996) a sample size of about 100 is adequate for a study with a vast population. Considering the users of fuel within the staff of Zoom Lion Ghana limited in Ghana, this paper’s choice of a 650-sample size can be seen as appropriate. Non-probability sampling technique involves selection of samples. According to Neuman (2011), non-probability sampling technique is useful when working with a smaller sample size and when the researcher wants to select cases that are well informed. Staff within Zoom Lion Ghana limited who are well informed as well as who consume fuel products of oil marketing companies and can better understand and answer the questions is an obvious choice for this study.

Data Collection Instrument and Method

With the purpose of addressing the hypotheses, the data collection instrument employed for this study was an online survey questionnaire. Malhotra and Birks (2013) suggest that researchers have more flexibility in data collection using the above approach as they can use different question formats. The design of the questionnaires was primarily based on multiple-item measurement scales adopted from previous research on celebrity characteristics and consumer behavior outcomes. The first section of the questionnaire elicited demographic information on sex, age, education and annual income. The second section obtained information on the dimensions of customer experience. The third section as well obtained data on outcomes of customer experience which included satisfaction, loyalty and word of mouth. The questionnaire was a Likert scale type, and anchored on 1 “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree”. Prior to administration of the survey, a panel comprised of 20 graduate research students reviewed the measurement items (Malhotra & Birks 2013). Questionnaires was developed in English. Subsequently, the questionnaires were answered by the respondents who were contacted at various Zoom Lion Ghana limited offices across the sixteen regions of Ghana. After six weeks, 650 responses were obtained out of which 524 were found usable for the analysis after a thorough cleaning of data.

Measures

The various items used in measuring the constructs were developed based on literature. The customers were asked to identify dimensions of customer experience at oil marketing companies in Ghana. They responded on a Likert scale of 1 “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree”. The items used in measuring lower order variables which explains customer experience (employees, core service, value addition, speed, marketing mix, social regard) were adapted from Garg & Rahman, (2014) and Butcher (2003). The items used in measuring customer experience outcomes (satisfaction and loyalty,) were also adapted from (Dagger et al., 2007; Zeithaml et al., 1996; Parasuraman et al., 2005; Jones & Taylor, 2007).

Results Presentation

Descriptive statistics relating to the characteristics of respondents are discussed below. Out of the 524 responses used for the analysis, 80.3% were male, with 19.7% representing females. In terms of age, the greater percentage of 52.9% was found between the ages of 30-39, with 40 and above recording the second highest age percentage of 38.4% and 21-29 recording 8.8%. Respondents varied in terms of their education levels with greater number of respondents indicating they had their HND/Diploma (47.9%), undergraduate degree (40.6%), masters (11.1), and doctorate (0.4%). For the type of OMC where customers buy their fuel, 55.4% of the respondents indicated that they use fuel from GOIL, followed by 25.6% indicating that they use fuel from Shell. Total respondents also accounted for 2.6%, while Other OMC fuel stations users who responded accounted for 16.4%. Because this study’s focus was on construct associations and not descriptive insights, the study did not take into consideration weighting the sampling elements.

Analysis

In accordance with the recommendation by Chin (1998), on the two-step approach for evaluating structural equation models, we first assessed the measurement model for reliability and validity. The structural paths between the variables in the proposed model were also tested. The Smart PLS 3 software was used to evaluate the reliability and validity of the measurement model as well as assay the structural model. This was as a result of the fact that the data had dimensions (employees, core service, value addition, speed, marketing mix, social regard) which were reflective in appreciating the complexity of the higher order construct (customer experience) in terms of its effects and consequences. Reliability, discriminant validity and convergent validity were assessed with the measurement model. Reliability of constructs was evaluated using Cronbach’s α. From Table 1 it can be seen that Cronbach’s α values are engrossingly greater than the threshold set by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994). It can consequently be established that the measurement model exhibits good reliability.

The study relied on Henseler et al. (2009) recommendation on convergent validity of the measurement model which state that; “the average variance extracted (AVE) for each latent construct should be greater than 0.5”. As indicated in Table 2, the constructs’ AVE values are well above 0.5 which is in agreement with studies by Henseler et al. (2009). As well, all indicators show significant standardized loading ranging between 0.773 and 0.939 (p<0.001). This is in agreement with Hair et al. (2013) who claimed that factor loading estimates should be higher than 0.7. Also, Cronbach alpha and composite reliability values for the model construct were greater than 0.6 for constructs signifying internal consistency. This is in agreement with Hair et al. (2012) who indicated that factor variables are declared reliable if it has Cronbach alpha and composite reliability value greater than 0.6. It can hence, be concluded that the measurement model exhibits good convergent validity.

| Table 2 Internal Consistency | ||||||

| Construct | Cronbach's Alpha | Criteria | Results | Composite Reliability (CR) | Criteria | Results |

| EMPL | 0.861 | 0-1 | Reliable | 0.905 | 0.7 to 0.9 | Reliable |

| CSQ | 0.832 | 0-1 | Reliable | 0.899 | 0.7 to 0.9 | Reliable |

| MM | 0.882 | 0-1 | Reliable | 0.927 | 0.7 to 0.9 | Reliable |

| SP | 0.852 | 0-1 | Reliable | 0.931 | 0.7 to 0.9 | Reliable |

| VA | 0.801 | 0-1 | Reliable | 0.883 | 0.7 to 0.9 | Reliable |

| SR | 0.950 | 0-1 | Reliable | 0.964 | 0.7 to 0.9 | Reliable |

| CS | 0.933 | 0-1 | Reliable | 0.949 | 0.7 to 0.9 | Reliable |

| BLI | 0.826 | 0-1 | Reliable | 0.896 | 0.7 to 0.9 | Reliable |

For discriminant validity, the study accessed it based on Fornell & Larcker’s (1981) criterion, by testing if the square root of the Average variance extracted is greater than its correlation with each of the remaining constructs. Initially, the AVE for each construct was calculated. The average variance extracted of the constructs ranged from 0.705 to 0.871 (see Table 2). The values calculated were in agreement or exceeded the acceptable threshold of 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). It is also evident from (Table 3) that the square root of the AVEs for each construct is greater than the cross-correlation with other constructs.

| Table 3 Results for Testing Reliability and Convergent Validity | |||||||

| Construct | Item | Outer Loading | Criteria | Results | AVE | Criteria | Results |

| EMPL | EMPL 1 | 0.827 | >0.708 | Fulfilled | 0.705 | >0.5 | Fulfilled |

| EMPL 2 | 0.827 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| EMPL 3 | 0.857 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| EMPL 4 | 0.846 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| CSQ | CSQ 1 | 0.856 | >0.708 | Fulfilled | 0.748 | >0.5 | Fulfilled |

| CSQ 2 | 0.859 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| CSQ 3 | 0.844 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| MM | MM 1 | 0.917 | >0.708 | Fulfilled | 0.809 | >0.5 | Fulfilled |

| MM 2 | 0.910 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| MM 3 | 0.870 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| SP | SP 1 | 0.773 | >0.708 | Fulfilled | 0.871 | >0.5 | Fulfilled |

| SP2 | 0.831 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| VA | VA1 | 0.787 | >0.708 | Fulfilled | 0.717 | >0.5 | Fulfilled |

| VA2 | 0.881 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| VA3 | 0.868 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| SR | SR 2 | 0.926 | >0.708 | Fulfilled | 0.870 | >0.5 | Fulfilled |

| SR 3 | 0.939 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| SR 4 | 0.931 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| SR 5 | 0.934 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| CS | CS 1 | 0.859 | >0.708 | Fulfilled | 0.789 | >0.5 | Fulfilled |

| CS 2 | 0.896 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| CS 3 | 0.911 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| CS 4 | 0.890 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| CS 5 | 0.886 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| BLI | BLI 1 | 0.886 | >0.708 | Fulfilled | 0.742 | >0.5 | Fulfilled |

| BLI 2 | 0.894 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

| BLI 3 | 0.802 | Fulfilled | Fulfilled | ||||

Structural Model Assessment

Because the measurement outcomes were shown to meet and exceed set criteria, it was prudent to continue with the structural model. The assessment of the structural model was centred on the sign, magnitude and significance of path coefficients of each hypothesised path. In order to determine the significance of each estimated path, the bootstrapping procedure was used with 5,000 bootstrap subsamples drawn with replacement (Hair et al., 2013). Table 4 shows the path coefficient of each of the developed hypothesis in figure 1, in addition to the explained variances. From Table 4, all hypothesis (H1-H8) were confirmed. The findings indicated the positive relationship existing between the higher order construct and the lower order construct, in addition to outcome such as loyalty and satisfaction. Further, the results also established a link between satisfaction and loyalty behavior as shown by H8 in Table 5.

| Table 4 Construct Outer Loadings, CR, AVE, Reliabilities, and Intercorrelations | ||||||||||||

| CONSTRUCT | ALPHA | CR | AVE | CSQ | EMPL | BLI | MM | CS | SR | SP | VA | WOM |

| CSQ | 0.832 | 0.899 | 0.748 | 0.865 | ||||||||

| EMPL | 0.861 | 0.905 | 0.705 | 0.633 | 0.840 | |||||||

| BLI | 0.826 | 0.896 | 0.742 | 0.497 | 0.491 | 0.862 | ||||||

| MM | 0.882 | 0.927 | 0.809 | 0.562 | 0.509 | 0.569 | 0.899 | |||||

| CS | 0.933 | 0.949 | 0.789 | 0.593 | 0.589 | 0.648 | 0.665 | 0.889 | ||||

| SR | 0.95 | 0.964 | 0.87 | 0.505 | 0.576 | 0.641 | 0.584 | 0.644 | 0.933 | |||

| SP | 0.852 | 0.931 | 0.871 | 0.536 | 0.491 | 0.519 | 0.645 | 0.664 | 0.567 | 0.933 | ||

| VA | 0.801 | 0.883 | 0.717 | 0.664 | 0.500 | 0.518 | 0.642 | 0.647 | 0.518 | 0.600 | 0.846 | |

| Table 5 Summary of Hypothesis Testing Results | |||||||

| Path | Original Sample | Sample Mean | SD | t-values | R2 | Q2 | F2 |

| Main Effect | |||||||

| H1. CE→EMPL | 0.793 | 0.792 | 0.021 | 38.355 | 0.628 | 1.691 | |

| H2. CE→CSQ | 0.837 | 0.836 | 0.017 | 48.754 | 0.7 | 2.332 | |

| H3. CE→MM | 0.828 | 0.828 | 0.017 | 49.283 | 0.686 | 2.182 | |

| H4. CE→SP | 0.777 | 0.777 | 0.024 | 32.556 | 0.604 | 1.528 | |

| H5. CE→VA | 0.829 | 0.83 | 0.019 | 45.843 | 0.688 | 2.206 | |

| H6. CE→CS | 0.773 | 0.774 | 0.02 | 40.140 | 0.598 | 0.468 | 1.486 |

| H7. CE→BLI | 0.196 | 0.196 | 0.058 | 3.391 | 0.519 | 0.38 | 0.028 |

| SR→BLI | 0.287 | 0.286 | 0.059 | 4.838 | |||

| Relationships among constructs | |||||||

| H8. CS→BLI | 0.287 | 0.286 | 0.059 | 4.838 | 0.064 | ||

| Indirect Effect | |||||||

| H9. CE→SR→BLI | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.033 | 6.649 | |||

Further, the structural model was assessed by its ability to predict endogenous construct using the coefficient of determination R2. The coefficient of determination (R2) of the latent variable, a critical method in PLS path models for accessing the structural model was utilized in evaluating the customer experience model (Henseler et al., 2009). Chin & Newsted (1999) argued in their research that coefficient of determination (R2) values such as 0.19, 0.33 and 0.67 reflect the following interpretations; weak, moderate and substantial respectively. Therefore, the findings indicated that the study model explained 59.8 percent of the variance in customer satisfaction and 51.9 percent for behavioural loyalty.

Also, the values for F2 which shows the relative size of each incremental effect in the structural model was also indicated (Sanchez-Casado et al., 2018). As proposed by prior studies, values of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 show a small, medium or large effect size (Cohen, 1988). As indicated in Table 4 above, per this research, the F2 values were seen to be larger than the threshold size of 0.02 for hypotheses H1-H8, which showed that the study model reflected a good explanatory power. In addition, the predictive relevance was evaluated using the Stone-Geiser’s Q2. A blindfolding approach in Smart PLS was utilized in measuring the above in which all the endogeneous values that positive are considered predictive. As indicated in Table 4, all the Q2 values were positive, consequently, the relationship in the model had predictive relevance.

Mediation Effect

After evaluating the model to test the various hypotheses H1-H8, mediation effect was assessed using the bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 bootstrap subsamples drawn with replacement (Hair et al., 201) in smart PLS. With respect to the mediation hypothesis, their outcomes and significance were estimated for the mediated hypothesis. It was shown from the evaluation that social regard partially mediated the effect of customer experience with behavioural loyalty intention (γ=0.220, t= 6.749 p< 0.000) at oil marketing companies.

Discussions and Study Implications

The study offers empirical proof in support of comprehending the dimensions which explain the structure of customer experience at oil marketing companies in Ghana. Also, the research reports a significant effect of customer experience on marketing outcome such as satisfaction and loyalty. The results have implications for academia and business practitioners as will be provided below.

The study’s results confirm that customer experience is explained by such dimensions as employees, core service, value addition, speed, and marketing mix. This is reflect by the positive and significant relationship which was shown in the findings to the effect that customer experience is explained by the above dimensions. The above is in agreement with studies by Garg et al. (2014) who assert that customer’s assessment of experience is inclusive of the above dimensions. For instance, the dimension of employees which explained customer experience and was positive and significant,

“Reflect the emotional benefit that customers experience based on the perceived expertise of the service provider and the guidance throughout the encounter, resulting to establishing a relationship with the firm” (Benedapudi & Berry, 1997; Dabholkar et al., 1996).

Further, in assessing the direct influence of the higher order construct (customer experience) on such marketing outcomes as behavioral loyalty and satisfaction, the findings indicated a positive and significant relationship. However, unlike Klaus & Maklan (2013), whose study found a stronger relationship between customer experience and loyalty than between customer experience and customer satisfaction, this research reveal that customer experience had a stronger, significant and positive relationship with satisfaction than with loyalty. The results is in agreement with Srivastava & Kaul (2016), who’s findings suggest that customer experience affects positively loyalty of two kinds (attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty). As a result, the finding did not support the assertion that experience measures provide superior explanatory power (Klaus & Maklan, 2013) but rather confirmed the fact that satisfaction measures current state and leads to loyalty.

Also, the results also established a link between satisfaction and loyalty behavior although prior studies had questioned the nature of the relationship because although improved customer satisfaction is desirable it is not a sufficient basis for consumers exhibiting loyalty behavior (McDougall & Levesque, 2000). The result was supported by Klaus & Maklan (2013) study which found that there is a link between satisfaction and loyalty behavior. The research as well illustrates that customer experience affects behavioural loyalty via social regard. The above is a clear indication that this social-psychological concept addresses the interaction between the firm and the customer and results in marketing outcome of loyalty. As the findings indicates, it was also observed that social regard had a “greater predictive power on loyalty behaviour”, which is in agreement with (Butcher & Heffernan, 2006).

The results of this research offers important implication for oil marketing companies within sub-Saharan Africa. OMC’s of all sort must become conscious of customer experience as a concept for achieving competitive advantage. The findings have established the effect of customer experience on customer satisfaction and loyalty and also via social regard. As such, customer experience can be considered and managed as a long-term approach for improving business growth (Jain et al., 2017). The findings also suggest that the dimensions of customer experience can provide oil marketing companies (Fuel Stations) an effective management of customer experiences. Therefore, oil marketing companies (Fuel Stations) can utilise the right systems and procedures for developing strategies for shaping and influencing stakeholder behaviour (experiences).

Conclusion Limitation and Future Studies

Like other relevant studies, this research had limitation, which show that there is room for future research. First, those used for the study were employees of Ghana’s largest waste management company (Zoom Lion Ghana) who patronize fuel product and services from OMC, who probably may be different from other customers with varying cultural characteristics. Future cross-sectional studies, should consider the general filling station customer base who throng these stations often to derive the desired satisfaction of meeting a particular need.

Second, despite the fact that customer experience at OMC’s was explained by six dimensions, all other dimensions of customer experience was not included. Therefore, utilizing these other dimension of customer experience in future studies will add to the body knowledge. Finally, this study considered only the direct and indirect effect of the dimensions and the marketing outcomes with sample of 524. Future studies can consider a larger sample and the moderation effect of the demographic data assessed on the marketing outcomes.

References

- Aaker, D.A. (1991). Managing Brand Equity, The Free Press, New York.

- Anderson, R.E., & Srinivasan, S.S. (2003). E‐satisfaction and e‐loyalty: A contingency framework, Psychology & Marketing, 20(2), 123-138.

- Babin, B.J., Darden, W.R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value, Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644-656.

- Baxendale, S., Macdonald, E.K., & Wilson, H.N. (2015). The impact of different touch points on brand consideration, Journal of Retailing, 91(2), 235-253.

- Benedapudi, N., & Berry, L.L. (1997). Customers' motivations for maintaining relationships with service providers, Journal of Retailing, 73(1), 15-38.

- Bergmann, R. (1999), Experience Management, Springer, New York, NY.

- Berry, L.L., Carbone, L.P., & Haeckel, S.H. (2002). Managing the total customer experience, MIT Sloan Management Review, 43(3), 85-89.

- Bever Innovation. (2015). Improving Customer Forecourt Experience, available at: https://www.beverinnovations.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/2015_Bever-brochure-FOC-2015-02_INT.pdf (accessed 14 February 2019).

- Blodgett, J.G., Hill, D.J., & Tax, S.S. (1997). The effects of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice on post complaint behaviour, Journal of Retailing, 73(2), 185-210.

- Bolton, R.N., Gustafsson, A., McColl-Kennedy, J., Sirianni, N.J., & Tse, D.K. (2014). Small details that make big differences: A radical approach to consumption experience as a firm's differentiating strategy, Journal of Service Management, 25(2), 253-274.

- Brakus, J.J., Schmitt, B.H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: what is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(3), 52-68.

- Brown, S.W., Cowles, D.L., & Tuten, D.L. (1996). Service recovery: its value as a retail strategy, International Journal of Service Industry Management, 7(5), 32-46.

- Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2007). Business Research Methods, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Bueno, E.V., Weber, T.B.B., Bomfim, E.L., & Kato, H.T. (2019). Measuring customer experience in service: A systematic review, The Service Industries Journal, 39(11-12), 779-798.

- Burns, A.C., & Bush, R.F. (2010). Marketing research (6th ed.), Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Bustamante, J.C., & Rubio, N. (2017). Measuring customer experience in physical retail environments, Journal of Service Management, 28(5), 884-913.

- Butcher, K., Sparks, B., & O’Callaghan, F. (2001). Evaluative and relational influences on service loyalty, International Journal of Service Industry Management, 12(4), 319-327.

- Butcher, K., Sparks, B., & O'Callaghan, F. (2003). Beyond core service, Psychology & Marketing, 20(3), 187-208.

- Butcher, K., & Heffernan, T. (2006). Social regard: A link between waiting for service and service outcomes, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 25(1), 34-53.

- Caruana, A. (2002). Service loyalty: The effects of service quality and the mediating role of customer satisfaction, European Journal of Marketing, 37(7/8), 811-828.

- Cetin, G., & Dincer, F.I. (2014). Influence of customer experience on loyalty and word-of-mouth in hospitality operations, Anatolia, 25(2), 181-194.

- Chin, W.W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling, Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295-336.

- Chin, W.W., & Newsted, P.R. (1999). Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares, Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research, 1(1), 307-341.

- Chou, J.S., & Kim, C. (2009). A structural equation analysis of the QSL relationship with passenger riding experience on high speed rail: An empirical study of Taiwan and Korea, Expert Systems with Applications, 36(3), 6945-6955.

- Clemmer, E.C., & Schneider, B. (1993). Managing customer dissatisfaction with waiting: applying social psychological theory in a service setting. In: Swartz, T.A., Bowen, D.E., Brown, S.W. (Eds.), Advances in Services Marketing and Management, 5, 213-229.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power for the social sciences, Hillsdale, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum and Associates.

- Collie, T.A., Sparks, B., & Bradley, G. (2000). Investing in interactional justice: a study of the fair process effect within a hospitality failure context, Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 24(4), 448-472.

- Constantinides, E. (2006). The marketing mix revisited: towards the 21st century marketing, Journal of Marketing Management, 22(3-4), 407-438.

- Constantinides, E. (2010). Connecting small and medium enterprises to the new consumer: The Web 2.0 as marketing tool, In Global perspectives on small and medium enterprises and strategic information systems: International approaches (pp. 1-21). IGI Global.

- Cossio-Silva, F.J., Revilla-Camacho, M.Á., Vega-Vázquez, M., & Palacios-Florencio, B. (2016). Value co-creation and customer loyalty, Journal of Business Research, 69(5), 1621-1625.

- Coviello, N.E., Brodie, R.J., & Munro, H.J. (2000). An investigation of marketing practice by firm size”, Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5-6), 523-545.

- Cronin Jr, J.J., Brady, M.K., & Hult, G.T.M. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments, Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 193-218.

- Dabholkar, P.A., Thorpe, D.I., & Rentz, J.O. (1996). A measure of service quality for retail stores: scale development and validation, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 24(1), 3.

- Dagger, T.S., Sweeney, J.C., & Johnson, L.W. (2007). A hierarchical model of health service quality: scale development and investigation of an integrated model, Journal of Service Research, 10(2), 123-142.

- De Chernatony, L., & McDonald, M.H.B. (1998), Creating Powerful Brands in Consumer, Service and Industrial Markets, Butterworth‐Heinemann, Oxford.

- de Chernatony, L., Harris, F., & Riley, F.D.O. (2000). Added value: its nature, roles and sustainability. European Journal of Marketing, 34(1-2), 39-54.

- De Keyser, A., Lemon, K.N., Klaus, P., & Keiningham, T.L. (2015). A framework for understanding and managing the customer experience, Marketing Science Institute Working Paper Series, 85(1), 15-121.

- Ding, D.X., Hu, P.J.H., & Sheng, O.R.L. (2011). e-SELFQUAL: A scale for measuring online self-service quality, Journal of Business Research, 64(5), 508-515.

- Eisingerich, A.B., & Bell, S.J. (2006). Relationship marketing in the financial services industry: The importance of customer education, participation and problem management for customer loyalty, Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 10(4), 86-97.

- Fernandes, T., & Pinto, T. (2019). Relationship quality determinants and outcomes in retail banking services: The role of customer experience, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 50, 30-41.

- Fisher, C.D., & To, M.L. (2012). Using experience sampling methodology in organizational behaviour, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(7), 865-877.

- Fisk, R.P., Patrício, L., Rosenbaum, M.S., & Massiah, C. (2011). An expanded servicescape perspective, Journal of Service Management, 22(4), 471-490.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error, Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

- Garg, R., Rahman, Z., & Qureshi, M.N. (2014). Measuring customer experience in banks: scale development and validation, Journal of Modelling in Management, 9(1), 87-117.

- Gartner. (2016). Gartner Predicts a Customer Experience Battlefield, available at: https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/customer-experience-battlefield/ (accessed 14 February 2019).

- GfK. (2016). Delivering a consistent customer experience at the petrol pump, available at: https://www.gfk.com/fileadmin/user_upload/country_one_pager/GB/documents/Energy_Oil__3_.pdf (accessed 21 July 2019).

- Ghana Energy Commission. (2006). Strategic National Energy Plan 2006 – 2020, Annex Three of Four, available at: http://www.energycom.gov.gh/planning/snep?download=2:petroleum (accessed 21 June 2019).

- Grewal, D., Levy, M., & Kumar, V. (2009). Customer experience management in retailing: An organizing framework, Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 1-14.

- Grace, D., & O’Cass, A. (2004). Examining service experiences and post-consumption evaluations, Journal of Services Marketing, 18(6), 450-461.

- Gronroos, C. (1984). A service quality model and its marketing implications”, European Journal of Marketing, 18(4), 36-44.

- Grönroos, C. (1997). Value‐driven relational marketing: from products to resources and competencies, Journal of Marketing Management, 13(5), 407-419.

- Gonzalez-Mansilla, Ó., Berenguer-Contrí, G., & Serra-Cantallops, A. (2019). The impact of value co-creation on hotel brand equity and customer satisfaction, Tourism Management, 75, 51-65.

- Gupta, S.V., & Vajic, M. (1999). The Contextual and Dialectical Nature of Experiences. New Service Development: Creating Memorable Experiences, ed. J. Fitzimmons, M. Fitzimmons, 33-35.

- Hair, J.F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C.M., & Mena, J.A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414-433.

- Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance, Long Range Planning, 46(1-2), 1-12.

- Hair, J.F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V.G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research, European Business Review, 26(2), 106-121.

- Helkkula, A. (2011). Characterising the concept of service experience, Journal of Service Management, 22(3), 367-389.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., & Sinkovics, R.R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing, In New Challenges to International Marketing, 277-319.

- Heskett, J.L., Jones, T.O., Loveman, G.W., Sasser, W.E., & Schlesinger, L.A. (1994). Putting the service-profit chain to work, Harvard Business Review, 72(2), 164-174.

- Holbrook, M.B., & Hirschman, E.C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: consumer fantasies, feelings and fun, Journal of Consumer Research, 9(1), 132-140.

- Hui, M.K., & Zhou, L. (1996). How does waiting duration information influence customer’s reaction to waiting for services? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26(19), 1702-1717.

- Iacobucci, D., Grayson, K.A., & Ostrom, A. (1994). The calculus of service quality and customer satisfaction: theoretical and empirical differentiation and integration, Advances in Services Marketing and Management, 3(C), 1-67.

- Jain, R., & Bagdare, S. (2009). Determinants of customer experience in new format retail stores, Journal of Marketing & Communication, 5(2).

- Jain, R., Aagja, J., & Bagdare, S. (2017). Customer experience–a review and research agenda, Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(3), 642-662

- Jones, T., & Taylor, S.F. (2007). The conceptual domain of service loyalty: how many dimensions? Journal of Services Marketing, 36-51.

- Keisidou, E., Sarigiannidis, L., Maditinos, D.I., & Thalassinos, E.I. (2013). Customer satisfaction, loyalty and financial performance, International Journal of Bank Marketing, 31(4), 259-288.

- Keller, K. (2013). Strategic brand management: Global edition, Pearson Higher Ed.

- Kim, S., Cha, J., Knutson, B.J., & Beck, J.A. (2011). Development and testing of the Consumer Experience Index (CEI), Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 21(2), 112-132.

- Klaus, P.P., & Maklan, S. (2013). Towards a better measure of customer experience. International Journal of Market Research, 55(2), 227-246.

- Klaus, P. (2014). Measuring Customer Experience - How to Develop and Execute the Most Profitable Customer Experience Strategies, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Knutson, B.J., Beck, J.A., Kim, S.H., & Cha, J. (2007). Identifying the dimensions of the experience construct, Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 15(3), 31-47.

- Koller, M., Floh, A., & Zauner, A. (2011). Further insights into perceived value and consumer loyalty: A “green” perspective, Psychology & Marketing, 28(12), 1154-1176.

- Kotler, P., & Keller, K. (2014). Marketing Management. 15th Edition, Prentice Hall, Saddle River.

- Kumar, V., Umashankar, N., Kim, K.H., & Bhagwat, Y. (2014). Assessing the influence of economic and customer experience factors on service purchase behaviors, Marketing Science, 33(5), 673-692.

- Larson, R.C. (1987). Perspectives on queues: social justice and the psychology of queuing, Operations Research, 35 (6), 895-905.

- Lemke, F., Clark, M., & Wilson, H. (2011). Customer experience quality: an exploration in business and consumer contexts using repertory grid technique, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(6), 846-869.

- Lemon, K.N., & Verhoef, P.C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey, Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 69-96.

- Macdonald, E., Wilson, H.N., & Konus, U. (2012). Better customer insight-in real time (Vol. 90). Harvard Business School Publishing.

- Machleit, K.A., & Eroglu, S.A. (2000). Describing and measuring emotional response to shopping experience, Journal of Business Research, 49(2), 101-111.

- Malhotra, N.K., Birks, D.F., & Wills, P. (2013). Essentials of marketing research. Harlow: Pearson.

- Malik, S.A., Akhtar, F., Raziq, M.M., & Ahmad, M. (2020). Measuring service quality perceptions of customers in the hotel industry of Pakistan, Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 31(3-4), 263-278.

- Manning, H., & Bodine, K. (2012). Outside in: the power of putting customers at the center of your business. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- McCarthy, J., & Wright, P. (2004). Technology as experience, interactions, 11(5), 42-43.

- McColl-Kennedy, J.R., Gustafsson, A., Jaakkola, E., Klaus, P., Radnor, Z.J., Perks, H., & Friman, M. (2015). Fresh perspectives on customer experience, Journal of Services Marketing, 29(6-7), 430-435.

- McDougall, G.H., & Levesque, T. (2000). Customer satisfaction with services: putting perceived value into the equation, Journal of Services Marketing, 14(5), 392-410.

- McPherson Oil. (2017). Top challenges for fuel retailers, available at: https://www.mcphersonoil.com/top-challenges-for-fuel-retailers/ (accessed 14 February 2019)

- McQuilken, L., McDonald, H., & Vocino, A. (2013). Is guarantee compensation enough? The important role of fix and employee effort in restoring justice, International Journal of Hospitality Management, 33, 41-50.

- Mensah-Keli, J. (2016). Customer service at fuel stations, available at: https://www.graphic.com.gh/features/opinion/customer-service-at-fuel-stations.html (accessed 21 June 2019).

- Mossberg, L. (2007). A marketing approach to the tourist experience, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(1), 59-74.

- Neuman, W.L. (2011). Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, seventh ed. Pearson, Boston.

- Nunnally, J.C., & Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Validity. Psychometric Theory, 3, 99-132.

- NPA. (2017). List of Companies whose licenses have been revoked, available at: https://www.npa.gov.gh/images/npa/documents/notices/REVOKED_COMPANIES_DATA.pdf (accessed 21 June 2019).

- Olsson, L.E., Friman, M., Pareigis, J., & Edvardsson, B. (2012). Measuring service experience: Applying the satisfaction with travel scale in public transport, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 19(4), 413-418.

- O’Sullivan, E.L., & Spangler, K.J. (1998). Experience marketing—strategies for the new millennium, State College, PA: Venture.

- Osei-Frimpong, K. (2017). Patient participatory behaviours in healthcare service delivery: Self-Determination Theory (SDT) perspective, Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(2), 453-474.

- Palmer, A. (2010). Customer experience management: a critical review of an emerging idea, The Journal of Services Marketing, 24(3), 196-208.

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A., & Berry, L.L. (1985). A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research, Journal of Marketing, 49(4), 41-50.

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A., & Berry, L.L. (1988). SERVQUAL: a multiple‐item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality, Journal of Retailing, 64, Spring, 12‐40.

- Parasuraman, A., & Grewal, D. (2000). Serving customers and consumers effectively in the twenty-first century: A conceptual framework and overview, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 9-16.

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A., & Malhotra, A. (2005). ES-QUAL: A multiple-item scale for assessing electronic service quality, Journal of Service Research, 7(3), 213-233.

- Pileliene, L., & Bakanauskas, A.P. (2016). Determination of factors affecting petrol station brand choice in Lithuania, In Entrepreneurship, Business and Economics, 1, 535-543.

- Pine, J., & Gilmore, J.H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy, Harvard Business Review, 97-105.

- Pine, J., & Gilmore, J.H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theatre and every business a stage, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Ravald, A., & Grönroos, C. (1996). The value concept and relationship marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 30(2), 19-30.

- Rowley, J. (1999). Measuring total customer experience in museums, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 11(6), 303-308.

- Sanchez-Casado, N., Confente, I., Tomaseti-Solano, E., & Brunetti, F. (2018). The role of online brand communties on building brand equity and loyalty through relational benefits, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 26(3), 289-308.

- Seemann, U. (2018)Fueling the Customer Experience, available at: https://www.cspdailynews.com/technologyservices/fueling-customer-experience (accessed 14 June 2019).

- Schembri, S. (2006). Rationalizing service logic, or understanding services as experience? Marketing Theory, 6(3), 381-392.

- Schmitt, B. (1999). Experiential marketing, Journal of Marketing Management, 15(1-3), 53-67.

- Shankar, V., Smith, A.K., & Rangaswamy, A. (2003). Customer satisfaction and loyalty in online and offline environments, International Journal of Research in Marketing, 20(2), 153-175.

- Sheng, J. (2019). Being active in online communications: firm responsiveness and customer engagement behaviour, Journal of Interactive Marketing, 46, 40-51.

- Sheu, J., Su, Y., & Chu, K. (2009). Segmenting online game customers: the perspective of experiential marketing, Expert Systems with Applications, 36(4), 8487-8495.

- Skorupa, J. (2015). Top Omnichannel Failures: Causes and Solutions, RIS News, available at: http://risnews.edgl.com/retail-insight-blog/Top-OmnichannelFailures--Causes-and-Solutions99718 (accessed 21 June 2019).

- Srivastava, M., & Kaul, D. (2016). Exploring the link between customer experience–loyalty–consumer spend, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 31, 277-286.

- Stein, A., & Ramaseshan, B. (2019). The customer experience–loyalty link: moderating role of motivation orientation, Journal of Service Management, 31(1), 51-78.

- GSS. (2017). Provisional 2017 Annual Gross Domestic Product, available at: http://www2.statsghana.gov.gh/docfiles/GDP/GDP2018/2017%20Quarter%204%20and%20annual%202017%20GDP%20publications/Annual_2017_GDP_April%202018%20Edition.pdf (accessed 21 June 2019).

- Stone, G.P. (1954). City shoppers and urban identification: observations on the social psychology of city life, American Journal of Sociology, 60(1), 36-45.

- Tabachnick, B.G., & Fidell, L.S. (1996). Using multivariate statistics, Northridge. Cal.: Harper Collins.

- Tax, S.S., Brown, S.W., & Chandrashekaran, M. (1998). Customer evaluations of service complaint experiences: implications for relationship marketing, Journal of Marketing, 62(April), 60‐76.

- Total Ghana. (2020). “About us”, available at: https://www.total-ghana.com/about-us (21 June 2019).

- Tsaur, S.H., Lin, C.T., & Wu, C.S. (2005). Cultural differences of service quality and behavioral intention in tourist hotels, Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 13(1), 41-63.

- Vargo, S.L., & Lusch, R.F. (2008). Service-dominant logic: continuing the evolution, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 1-10.

- Venkatraman, V., Clithero, J.A., Fitzsimons, G.J., & Huettel, S.A. (2012). New scanner data for brand marketers: How neuroscience can help better understand differences in brand preferences, Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(1), 143-153.

- Verhoef, P.C., Lemon, K.N., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M., & Schlesinger, L.A. (2009). Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies, Journal of Retailing, 85(1), 31-41.

- Walter, U., Edvardsson, B., & Ostrom, A. (2010). Drivers of customers’ service experiences: a study in the restaurant industry, Managing Service Quality, 20(3), 236-258.

- Xu, J., & Murray, A.T. (2019). Spatial variability in retail gasoline markets, Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science, 3(2), 581-603.