Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 6

Cross Disciple Graduate Perceptions Of The Effectiveness Of Entrepreneurship Education In A Turbulent Economy; Case Of Chinhoyi University Of Technology, Zimbabwe

Jengeta Mirriam, Chinhoyi University

Citation Information: Mirriam, J. (2022). Cross Disciple Graduate Perceptions of the Effectiveness of Entrepreneurship Education in A Turbulent Economy; Case of Chinhoyi University of Technology, Zimbabwe. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 25(6),1-12.

Abstract

Whilst a lot has been published about entrepreneurship education the world over, not much is known about its impact and effectiveness to graduates of the same university but different disciplines. If this special stakeholder voice is to remain silent, policy makers, university executives and academics may remain uninformed of the relevant approaches to effectively offer entrepreneurship education and wrongly direct resources meant for the development of entrepreneurship training. The aim of the study was to establish the mode of entrepreneurship education in Zimbabwean universities; assessing the impact of teaching methods used in entrepreneurship education in Zimbabwean universities, and, evaluating graduate perceptions on the influence of resource availability to teach entrepreneurship in a volatile economy. A positivism philosophy was used in this case study designed research. A total population of 1092 CUT graduates of 2015 across disciplines formed the target population and a sample of 220 graduates selected as participants for this study. Stratified random sampling strategy was used to select participants from this population. Each school formed a stratum and informed the selection of the representative sample. Results revealed the existence of entrepreneurship in the CUT curriculum and embedded in the modules that are offered by various schools at the university. There was a weak association between the existence of the entrepreneurship education and employment status. CUT needs to have a vibrant industrial liaison office to facilitate the proper filtering of the graduates to the market. There was a strong correlation between resources availability and teaching entrepreneurship in a volatile economy. In a turbulent economy, graduates themselves must take ownership seriously; they must demonstrate interest in venture creation and growth by contributing towards the availability of resources instead of just waiting for the government to do everything.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship, Education, Turbulent, Discipline.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship education is the engine with the potential to pull different economies to prosperity. For that to happen, proper curriculum planning and implementation have to be done effectively. A flexible supportive structure that ensures resources availability, allows trial and error approach to learning, harnesses new ideas and open to criticism is also ideal for entrepreneurship education to be a success.

Across the globe, the practical approach to teaching entrepreneurship has proved to be fruitful (Ooi & Nasiru, 2015; OECD, 2009&2012; Mushipe, 2013). In Zimbabwe however, the practical component seems to fall short in some trades. This may explain the non reciprocal state of entrepreneurship graduates churned out of the country’s universities and in the country’s economic situation. The number of Zimbabwean entrepreneurship graduates plasticising as entrepreneurs seem to be out-numbered by those from other disciplines. This scenario is disturbing given the fact that entrepreneurs are expected to be more proactive when it comes to risk taking and venture creation. This study sought to establish the possible reasons behind the scenario through establishing the graduate perceptions of the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education across disciplines at Chinhoyi University of Technology, Zimbabwe.

Focus is to be on establishing the mode of entrepreneurship education in Zimbabwean universities; assessing the impact of teaching methods used in entrepreneurship education in Zimbabwean universities, and, evaluating graduate perceptions on the influence of resource availability to teach entrepreneurship in a volatile economy.

Problem Statement

Whilst a lot has been published about entrepreneurship education the world over, not much is known about its impact and effectiveness to graduates of the same university but different disciplines. If this special stakeholder’s voice is to remain silent, policy makers, university executives and academics may remain uninformed of the relevant approaches to effectively offer entrepreneurship education and wrongly direct resources meant for the development of entrepreneurship training.

Literature Review

The Evolution and Mode of Entrepreneurship Education across the Globe

Entrepreneurship education was introduced in New York as a course in 1953 before exploding in the entire United States in 1967, and, the rest of Europe in 1980. It saw its way in Germany in 1998, grew in offerage in Autrallia in 1990 and saw its way to Africa.

Writers across the world (Belwal et al., 2015; Undiyandeye, 2014; Efe, 2014; Mauchi et al., 2011) suggest that entrepreneurship education can be taught in universities and other tertiary institutions. They however were not agreeing on, or specifying the form it has to take. Mushipe (2013) saw entrepreneurship education in Zimbabwe as collaborations between universities and large companies, with the latter initiating developmental programs at universities. This is done to boost the spirit of venture creation amongst graduates.

Whilst Mauchi et al. (2011) bemoan the need for entrepreneurship education at tertiary level; they were quick to reduce the same to single modules mainly taught across disciplines. This means that even in a specific nation, writers view this notion differently.

Entrepreneurship started as a course and developed into a discipline in many countries across the world including the United States, Germany, Australia, and Zimbabwe among others (Mauchi et al., 2011). The rising of unemployment in developed countries as a result of globalization and the general unemployment levels in most developing countries necessitated entrepreneurship education in universities (Mauchi et al., 2011). However, the pursuance of entrepreneurship education in both developed and developing nations may be as a result of the need for ownership, and wanting to be associated with the end user.

The Impact of Teaching Methods Used in Entrepreneurship Education

Various teaching methods are being used to teach entrepreneurship education at different levels and countries. However, there are no specific teaching methods said to be the best since the economic activity, resources availability, and willingness to learn differ in different people and nations. Ideal entrepreneurship teaching methods are subjective. Mauchi et al. (2011) acknowledged that little is known about the appropriate teaching and assessment strategies that boast the spirit of venture start ups in graduates.

Traditional teaching strategies that include lectures, reading materials, discussions, examinations, and tutorials as viewed by Mauchi et al. (2011), do not activate entrepreneurship. This is mainly because of their theoretical nature. Turning to examinations, Undiyaundeye (2015) revealed that there is too much emphasis on the value of a certificate as opposed to the skills required of a given profession. Students do whatever it takes to get a certificate and not the required knowledge and skills which make them self-reliant. Though not documented by many researchers, this notion seems to be true in many countries where education is the gate way to employment. This is why Nani (2014) advocated for experiential learning arguing that it puts emphasis on the learners to be actively involved and not just be mere recipients.

According to Du Toit & Gaotlhobogwe, (2018), although business subjects have some entrepreneurship content, the difference is on focus, with entrepreneurship focusing on creation of enterprises and these on preparing learners for different economic or business environments.

Resources availability is a critical component to teaching entrepreneurship in a volatile economy. Mushipe (2013) believed that through entrepreneurship education, graduates can achieve material and personal success, gain independence and control over the products of their labour. It is unfortunate that in such economies, teaching and training is usually done theoretically.

Methodology

A positivism philosophy is to be adopted in this case study designed research. A total 1092 CUT graduates of 2015 across disciplines formed the target population for this study. They were derived from the following schools; Entrepreneurship and Business Sciences, Art and Design, Hospitality and Tourism, Wildlife Conservation and Ecology, Agricultural Sciences and Technology, Engineering Sciences and Technology. Five years was considered as long enough a period for these graduates to have seen the need for starting their own ventures or raising capital for the same purpose. Stratified random sampling strategy was used to select participants from this population. Each school formed a stratum. Informed the selection of a representative sample of 220 out of 1092 graduates. propounded that, 10% of the population is adequate enough a sample for a population of more than 200, while 40 % can be used when the population is below 200 Table 1. Data was collected using self administered questionnaires, and SPSS version 20 was used to analyse the collected data (Keat, 2015).

| Table 1 Cut Schools where the Sample was Extracted | ||

| School | Number of graduates | Sample size |

| Entrepreneurship & Business Sciences | 722 (10%) | 72 |

| Art and Design | 68 (40%) | 27 |

| Hospitality & Tourism | 147 (40%) | 59 |

| Agricultural Sciences and Technology | 62 (40%) | 25 |

| Wildlife Conservation and Ecology | 21 (40%) | 8 |

| Engineering Sciences and Technology | 72 (40%) | 29 |

| Total | 1092 | 220 |

Data Presentation and Analysis

The objectives of the study were to establish the mode of entrepreneurship education in Zimbabwean universities; assess the impact of the teaching methods used in entrepreneurship education in Zimbabwean universities and evaluate graduate perceptions on the influence of resource availability to teach entrepreneurship in a volatile economy.

A total of 220 questionnaires were randomly distributed to CUT graduates of 2015 across disciplines. The response rate results from the study indicated that the majority of the questionnaires (90%) were returned compared to 10% that were not returned as illustrated by Table 2 below. The high response rate of 90% was an indication of interest by the respondents on the problem being investigated.

| Table 2 The Response Rate for the Questionnaire | ||

| Response rate | Frequency | Percentage |

| Returned | 197 | 90% |

| Unreturned | 23 | 10% |

| Total | 220 | 100% |

| Source: Researcher | ||

The response rate of 50% is adequate for analysis and reporting; a rate of 60% is good and a response rate of 70% and over is excellent. The response rate in the range of 50-65% is considered credible for analysis. However advanced that there are no agreed norms as to what may be considered reasonable Response Rate (RR). The response rate was considered credible for further statistical analysis as it was above the minimum threshold of 60%.

Mode of Entrepreneurship Education in Zimbabwean Universities

The mean responses to the three assertions regarding the existence of a program for entrepreneurship education, existence of dedicated courses for entrepreneurship education as well as the adequacy of CUT entrepreneurship education are shown on the above Table 3. Generally respondents were in agreement to the assertions given shown by the mean response in the range of 3.

| Table 3 Descriptive Statistics | ||||

| The CUT curriculum has a program for entrepreneurship education | The CUT curriculum has dedicated courses for entrepreneurship education | Entrepreneurship education offered to students in other schools at CUT is adequate | ||

| N | Valid | 197 | 197 | 197 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mean | 3.5736 | 3.3147 | 2.8325 | |

| Mode | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | |

| Std. Deviation | 0.58981 | .74398 | 0.86151 | |

| Skewness | -1.043 | -.583 | -.975 | |

| Std. Error of Skewness | 0.173 | 0.173 | 0.173 | |

Cumulatively, 94.9% of the respondents are in agreement with existence of entrepreneurship in the CUT curriculum Table 4. The majority of the respondents from across the schools were generally agreeing with the existence in their programmes.

| Table 4 The Cut Curriculum has a Program for Entrepreneurship Education | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Disagree | 10 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.1 |

| Agree | 64 | 32.5 | 32.5 | 37.6 | |

| Strongly Agree | 123 | 62.4 | 62.4 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 197 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

The respondents were in agreement that entrepreneurship education was embedded in the modules that are offered by various schools at CUT Table 5. Besides schools have specific modules that address entrepreneurship education.

| Table 5 The Cut Curriculum has Dedicated Courses for Entrepreneurship Education | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Disagree | 33 | 16.8 | 16.8 | 16.8 |

| Agree | 69 | 35.0 | 35.0 | 51.8 | |

| Strongly Agree | 95 | 48.2 | 48.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 197 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

Majority of respondents were of the view that entrepreneurship education offered to CUT students was adequate. Cumulatively, 70.7% agree and strongly agree respectively with the view of the adequacy of the offered entrepreneurship education Table 6.

| Table 6 Entrepreneurship Education Offered to Students in Other Schools at Cut is Adequate | |||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | ||

| Valid | Strongly Disagree | 27 | 13.7 | 13.7 | 13.7 |

| Disagree | 11 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 19.3 | |

| Agree | 127 | 64.5 | 64.5 | 83.8 | |

| Strongly Agree | 32 | 16.2 | 16.2 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 197 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ||

Table 7 above shows a cross tabulation of the view of the existence of a program in entrepreneurship education and the employment status of the respondents. Out of the 197 respondents, 54 (27%) of the employed respondents strongly agree that the CUT curriculum has a program for entrepreneurship education and 60 (30%) of the self-employed respondents strong agreed with the notion that the CUT curriculum has an entrepreneurship education. Only 9 of the unemployed respondents strongly agreed and only a total of 10 (5%) across the employment statuses disagree to the existence of entrepreneurship education in the CUT curriculum.

| Table 7 The Cut Curriculum has a Program for Entrepreneurship Education and Employment Status | |||||

| Employment status | Total | ||||

| Employed by someone | Self employed | Not Employed | |||

| The CUT curriculum has a program for entrepreneurship education | Disagree | 7 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| Agree | 31 | 27 | 6 | 64 | |

| Strongly Agree | 54 | 60 | 9 | 123 | |

| Total | 92 | 90 | 15 | 197 | |

Results from Table 8 above show the correlation and inferential statistics for the crosstabulation between the employment status and the existence of entrepreneurship education in the CUT curriculum. There was a week association between the existence of the entrepreneurship education and employment status as shown by the Cramer’s V of 0.093 as shown by the table above. However the probability value of 0.491 above resulted in the acceptance of the null hypotheses of the independence between the two variables. Existence of the entrepreneurship education in the CUT curriculum is independent of the employment status of the respondents.

| Table 8 Symmetric Measures | |||||

| Value | Asymp. Std. Errora | Approx. Tb | Approx. Sig. | ||

| Nominal by Nominal | Phi | 0.132 | .491 | ||

| Cramer's V | 0.093 | .491 | |||

| Contingency Coefficient | 0.131 | .491 | |||

| Interval by Interval | Pearson's R | 0.085 | 0.068 | 1.194 | .234c |

| Ordinal by Ordinal | Spearman Correlation | 0.076 | 0.071 | 1.063 | .289c |

| N of Valid Cases | 197 | ||||

| a. Using the asymptotic standard error assuming the null hypothesis. | |||||

| b. Based on normal approximation. | |||||

Table 9 above shows the cross tabulation of the existence of dedicated modules for entrepreneurship education and the school of the respondents. There was a significant association between school and dedicated entrepreneurship modules measured by the Cramer’s V of 0.657. The probability value of 0.000 was less that the level of significance of 0.05, which implied that the null hypothesis of independence of the variables could not be accepted. Existences of specific modules for entrepreneurship were school dependent at CUT. Some schools therefore did not have specific modules for entrepreneurship education but instead relied on other schools.

| Table 9 Symmetric Measures | |||||

| Value | Asymp. Std. Errora | Approx. Tb | Approx. Sig. | ||

| Nominal by Nominal | Phi | 0.928 | .000 | ||

| Cramer's V | 0.657 | .000 | |||

| Contingency Coefficient | 0.680 | .000 | |||

| Interval by Interval | Pearson's R | -.473 | 0.066 | -7.488 | .000c |

| Ordinal by Ordinal | Spearman Correlation | -.440 | 0.070 | -6.834 | .000c |

| N of Valid Cases | 197 | ||||

| a. Using the asymptotic standard error assuming the null hypothesis. | |||||

| b. Based on normal approximation. | |||||

The Table 10 above shows the cross tabulation of the school and the existence of a program for entrepreneurship education at CUT. There is a significant positive correlation between the two variables as measured by the Cramer’s V of 0.560. The probability value of 0.000 resulted in the non-acceptance of the null hypothesis of independence. CUT has schools that have specific programmes that have entrepreneurship education like the School of Business management and Entrepreneurship.

| Table 10 Symmetric Measures | |||||

| Value | Asymp. Std. Errora | Approx. Tb | Approx. Sig. | ||

| Nominal by Nominal | Phi | .792 | .000 | ||

| Cramer's V | .560 | .000 | |||

| Contingency Coefficient | .621 | .000 | |||

| Interval by Interval | Pearson's R | -.367 | .072 | -5.516 | .000c |

| Ordinal by Ordinal | Spearman Correlation | -.407 | .068 | -6.229 | .000c |

| N of Valid Cases | 197 | ||||

| a. Using the asymptotic standard error assuming the null hypothesis. | |||||

| b. Based on normal approximation. | |||||

The descriptive statistics above Table 11 are a cross-tabulation between the existence of dedicated courses for entrepreneurship and employment statuses of the respondents. Cumulatively 95 (48%) of the respondents across the employment statuses strongly agreed that CUT curriculum has dedicated modules for entrepreneurship education. Only 33 (17%) of the respondents across the employment statuses disagreed to the notion that CUT curriculum has dedicated modules for entrepreneurship education.

| Table 11 The Cut Curriculum has Dedicated Courses For Entrepreneurship Education * Employment Status Crosstabulation | |||||

| Employment status | Total | ||||

| Employed by someone | Self employed | Not Employed | |||

| The CUT curriculum has dedicated courses for entrepreneurship education | Disagree | 4 | 26 | 3 | 33 |

| Agree | 47 | 19 | 3 | 69 | |

| Strongly Agree | 41 | 45 | 9 | 95 | |

| Total | 92 | 90 | 15 | 197 | |

The correlation and inferential statistics in the Table 12 above show the cross tabulation of the existence of dedicated modules for entrepreneurship education and employment status. Results showed that the association between the two variables was not significant as measured by the Cramer’s V of 0.276 (27.6%). The two variables are insignificantly associated. Employment status is not associated much with the existence of dedicated entrepreneurship modules. The probability value of 0.000 resulted in the non-rejection of the null hypothesis of the independence of the two variables. Existence of dedicated modules for entrepreneurship education at CUT was not linked to the employment status of the respondents.

| Table 12 Symmetric Measures | |||||

| Value | Asymp. Std. Errora | Approx. Tb | Approx. Sig. | ||

| Nominal by Nominal | Phi | .390 | .000 | ||

| Cramer's V | .276 | .000 | |||

| Contingency Coefficient | .363 | .000 | |||

| Interval by Interval | Pearson's R | -.074 | .069 | -1.037 | .301c |

| Ordinal by Ordinal | Spearman Correlation | -.041 | .072 | -.576 | .566c |

| N of Valid Cases | 197 | ||||

| a. Using the asymptotic standard error assuming the null hypothesis. | |||||

| b. Based on normal approximation. | |||||

The descriptive statistics in Table 13 above show the cross tabulation between adequacy of the entrepreneurship education in other schools and the period of study. Results showed that 127 (64%) of the respondents agree with the notion that entrepreneurship education offered in other schools is adequate while 11 (6%) disagreed.

| Table 13 Entrepreneurship Education Offered to Students in other Schools at Cut is Adequate * Period as Graduate Crosstabulation | |||||||

| Period as graduate | Total | ||||||

| 1 Year | 2 Years | 3 Years | 4 Years | 5 Years | |||

| Entrepreneurship education offered to students in other schools at CUT is adequate | Strongly Disagree | 17 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 |

| Disagree | 4 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 11 | |

| Agree | 55 | 33 | 22 | 7 | 10 | 127 | |

| Strongly Agree | 16 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 32 | |

| Total | 92 | 55 | 25 | 11 | 14 | 197 | |

The statistics in the above Table 14 are showing the relationship between the adequacy of the schools’ entrepreneurship education and the period of study. The correlation coefficient measured by the Cramer’s V of 0.248 showed a weak association between the two variables. The probability value of 0.000 showed however that there was dependence between adequacy of entrepreneurship education and period of study.

| Table 14 Symmetric Measures | |||||

| Value | Asymp. Std. Errora | Approx. Tb | Approx. Sig. | ||

| Nominal by Nominal | Phi | .430 | .000 | ||

| Cramer's V | .248 | .000 | |||

| Contingency Coefficient | .395 | .000 | |||

| Interval by Interval | Pearson's R | .139 | .054 | 1.967 | .051c |

| Ordinal by Ordinal | Spearman Correlation | .079 | .067 | 1.113 | .267c |

| N of Valid Cases | 197 | ||||

| a. Using the asymptotic standard error assuming the null hypothesis. | |||||

| b. Based on normal approximation. | |||||

Impact of the Teaching Methods used on Entrepreneurship Education in Zimbabwean Universities

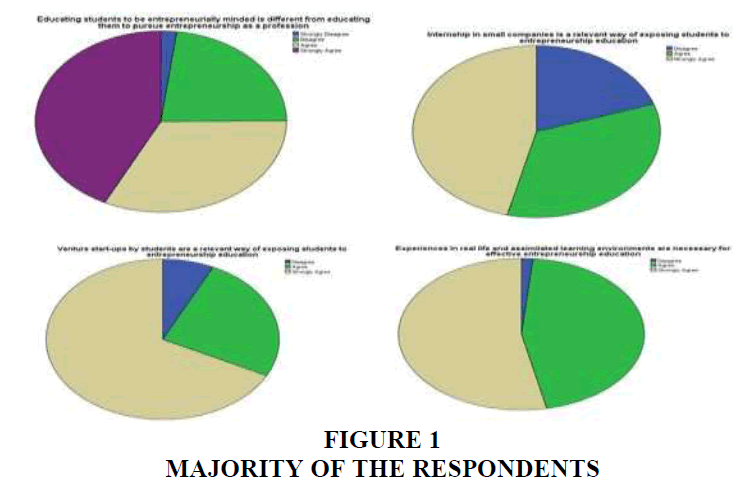

The Figure 1 below shows the view by respondents that teaching students to be entrepreneurially minded is different from educating them to pursue entrepreneurship as a profession and that internship in small companies was a relevant way of exposing students to entrepreneurship education. It also shows the relevance of venture start-ups in exposing learners to entrepreneurial education and the perception of the respondents regarding experiences in real life and assimilated learning environments as necessary conditions for effective entrepreneurship education.

Results from the above Figure 1 showed that the majority of the respondents strongly agree that teaching students to be entrepreneurially minded is different from educating them to pursue entrepreneurship as a profession and very few strongly disagreed with the notion. The majority of the respondents strongly agreed that internship in small companies was a relevant way of exposing students to entrepreneurship education while a few disagreed to the notion. Respondents strongly agreed that venture start-ups were a relevant way of exposing learners to entrepreneurship education while a small proportion of respondents disagreed. The majority strongly agreed that experiences in real life and assimilated learning environments were necessary conditions for effective entrepreneurship education.

The correlation and inferential statistics from Table 15 above show a cross tabulation of the view that venture start-ups were a relevant way of exposing learners to entrepreneurship education and respondent’s schools. The correlation coefficient measured by the Cramer’s V of 0.307 indicated that the relationship between the two variables was insignificant and the probability value of 0.000 resulted in the rejection of the null hypothesis of independence between the notions of the relevance of venture start-ups and the school of the respondent.

| Table 15 Symmetric Measures | |||||

| Value | Asymp. Std. Errora | Approx. Tb | Approx. Sig. | ||

| Nominal by Nominal | Phi | .434 | .000 | ||

| Cramer's V | .307 | .000 | |||

| Contingency Coefficient | .398 | .000 | |||

| Interval by Interval | Pearson's R | .011 | .066 | .147 | .883c |

| Ordinal by Ordinal | Spearman Correlation | .012 | .070 | .161 | .872c |

| N of Valid Cases | 197 | ||||

| a. Using the asymptotic standard error assuming the null hypothesis. | |||||

| b. Based on normal approximation. | |||||

The cross tabulation in Table 16 above relates the school of the respondent and the existence of an apprenticeship as an approach to entrepreneurship education in a volatile economy. The correlation coefficient of 0.561 showed a significant association between the two variables. The probability value of 0.000 also confirmed the dependence of the two random variables.

| Table 16 Symmetric Measures | |||||

| Value | Asymp. Std. Errora | Approx. Tb | Approx. Sig. | ||

| Nominal by Nominal | Phi | .793 | .000 | ||

| Cramer's V | .561 | .000 | |||

| Contingency Coefficient | .621 | .000 | |||

| Interval by Interval | Pearson's R | -.067 | .067 | -.936 | .351c |

| Ordinal by Ordinal | Spearman Correlation | -.123 | .077 | -1.724 | .086c |

| N of Valid Cases | 197 | ||||

| a. Using the asymptotic standard error assuming the null hypothesis. | |||||

| b. Based on normal approximation. | |||||

Graduate Perceptions on the Influence of Resource Availability to Teach Entrepreneurship in a Volatile Economy

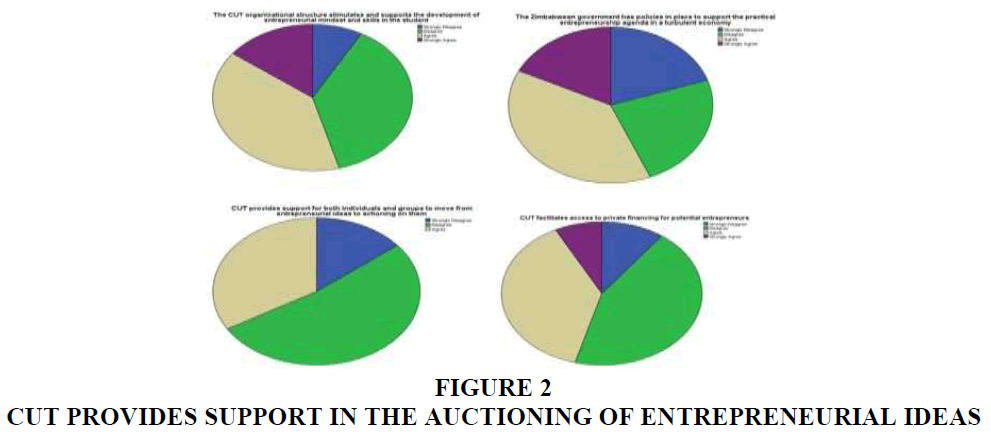

The Figure 2 above shows the respondents’ perception about whether CUT has the organisational structure that stimulates and supports the development of entrepreneurial mindset and skills to the learner and whether the government had policies in place to support practical entrepreneurship in a turbulent economy. The figure also show whether CUT facilitates access to private financing for potential entrepreneurs and whether CUT provides support in the auctioning of entrepreneurial ideas.

Results indicated that a sizeable proportion of respondents agreed to the notion that CUT has the organisational structure that stimulates and supports the development of entrepreneurial mind-set and skills to the learner while a smaller proportion disagreed to the notion. A greater proportion of the respondents disagreed that CUT provided support in the auctioning of entrepreneurial ideas, although a small percentage of respondents strongly disagreed.

Table 17 above shows the inferential statistics relating the school of the respondent and the view that government policies in place support practical entrepreneurship in a turbulent economy. There was a significant association between the two variables shown by the correlation coefficient of 0.630. The probability value of 0.000 supported the notion of dependence of the two variables.

| Table 17 Symmetric Measures | |||||

| Value | Asymp. Std. Errora | Approx. Tb | Approx. Sig. | ||

| Nominal by Nominal | Phi | 1.091 | .000 | ||

| Cramer's V | .630 | .000 | |||

| Contingency Coefficient | .737 | .000 | |||

| Interval by Interval | Pearson's R | -.559 | .053 | -9.421 | .000c |

| Ordinal by Ordinal | Spearman Correlation | -.549 | .061 | -9.179 | .000c |

| N of Valid Cases | 197 | ||||

| a. Using the asymptotic standard error assuming the null hypothesis. | |||||

| b. Based on normal approximation. | |||||

Discussion

Generally respondents were in agreement of the existence of dedicated courses for entrepreneurship education as well as the adequacy of CUT entrepreneurship education. This assertion is shared by Mushipe (2013), who views the entrepreneurship education as being done to boost the spirit of venture creation amongst graduates. Results further showed the existence of entrepreneurship in the CUT curriculum and embedded in the modules that are offered by various schools at the university. Entrepreneurship education is considered adequate. Mauchi et al (2011) contradict the study findings and bemoan the need for entrepreneurship education at tertiary level. Results showed a week association between the existence of the entrepreneurship education and employment status. Thus, the CUT graduates’ employment statuses are disconnected from the entrepreneurship training received. Undiyaundeye (2015) revealed that there is too much emphasis on the value of a certificate as opposed to the skills required of a given profession and such disconnection can result in employment choices deviating significantly from entrepreneurship training at universities. CUT needs to have a vibrant industrial liaison office that will facilitate the proper filtering of the graduates to the market.

Results from the study showed that the existence of specific modules for entrepreneurship were school dependent at CUT. This showed that some schools did not have specific modules for entrepreneurship education but instead relied on other schools. There was agreement that teaching students to be entrepreneurially minded was different from educating them to pursue entrepreneurship as a profession. Du Toit & Gaotlhobogwe (2018) asserted that business subjects have some entrepreneurship content; the difference is on focus, with entrepreneurship focusing on creation of enterprises and these on preparing learners for different economic or business environments. Results showed the relationship between the views that venture start-ups were a relevant way of exposing learners to entrepreneurship education was insignificant. The CUT curriculum should be very clear as the expectation of the graduates after the completion of their studies.

Results revealed that CUT has the organisational structure that stimulates and supports the development of entrepreneurial mind-set and skills to the learner and that the government had policies in place to support practical entrepreneurship in a turbulent economy. Resources availability is a critical component to teaching entrepreneurship in a volatile economy (Nani, 2014).

Conclusion

There is a strong correlation between these two variables and the ability of graduates to become successful entrepreneurs in turbulent economies was dependent upon the availability of resources. Government should continue providing resources as well as capacitation to ventures from these graduates. Efforts must be made by the government to create a predictable environment for business. In a turbulent economy, graduates themselves must take ownership seriously; they must demonstrate interest in venture creation and growth by contributing towards the availability of resources instead of just waiting for the government to do everything.

References

Belwal, R., Al Balushi, H., & Belwal, S. (2015). Students’ perception of entrepreneurship and enterprise education in Oman. Education+ Training.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Du Toit, A., & Gaotlhobogwe, M. (2018). A neglected opportunity: entrepreneurship education in the lower high school curricula for technology in South Africa and Botswana. African journal of research in mathematics, science and technology education, 22(1), 37-47.

Efe, A.J. (2014). Entrepreneurship education: A panacea for unemployment, poverty reduction and national insecurity in developing and underdeveloped countries. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 4(3), 124-136.

Keat, Y. (2015). Perceived effective entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention: The role of the perception of university support and perceived creativity disposition. Journal of Education and Vocational Research, 6(2), 70-79.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mauchi, F.N., Karambakuwa, R.T., Gopo, R.N., Njanike, K., Mangwende, S. and Gombarume, F.B. (2011). Entrepreneurship education lessons: a case of Zimbabwean tertiary education institutions. International research journal, 2(7),1306-1311.

Mushipe, Z.J. (2013). Entrepreneurship education---An alternative route to alleviating unemployment and the Influence of gender: An analysis of university level students' entrepreneurial business ideas. International Journal of Business Administration, 4(2), 1.

Nani, G.V. (2014). Teaching of ‘entrepreneurship’as a subject in zimbabwean schools-what are the appropriate teaching methods?–a case study of bulawayo metropolitan schools. Zimbabwe Journal of Science and Technology, 9(1), 21-27.

OECD (2009), Evaluation of Programmes Concerning Education for Entrepreneurship, report by the OECD Working Party on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, OECD.

OECD (2012) A guiding Framework for Entrepreneurship universities, OECD.

Undiyaundeye, F. (2015). Entrepreneurship skills acquisition and the benefits amongst the undergraduate students in Nigeria. European Journal of Social Science Education and Research, 2(3), 9-14.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 10-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. AJEE-22-12440; Editor assigned: 12-Aug -2022, Pre QC No. AJEE-22-12440(PQ); Reviewed: 26-Aug-2022, QC No. AJEE-22-12440; Revised: 02-Sep-2022, Manuscript No. AJEE-22-12440(R); Published: 09-Sep-2022