Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 4S

Critical success factors influencing project management success: Perspectives of Sri Lankan clients, consultants and contractors

Abeyratna Banda Sarath Herath, Management and Science University University Drive, Off Persiaran Olahraga

Siong Choy Chong, Finance Accreditation Agency Malaysia

Citation Information: Herath, A.B.S., & Chong, S.C. (2022). Critical success factors influencing project management success: Perspectives of Sri Lankan clients, consultants and contractors. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 25(S4), 1-16.

Keywords

Clients, Consultants, Contractors, Key Project Components, Critical Success Factors, Project Management Success, Sri Lanka

Abstract

This research investigates the perception of Sri Lankan clients, consultants and contractors on the critical success factors (CSFs) of key project components influencing project management success. Five key project components (project design document, project human resources management, stakeholder management, project budget and efficient project management) and their associated CSFs influencing project management success were identified from the literature. Self-administered questionnaires were distributed to project management personnel at 20 major clients, consulting and construction companies in Sri Lanka. The ANOVA results showed that the relationships amongst the clients, consultants and contractors were not significant. Although the Pearson correlation coefficient results showed significant relationships between all the key project components and project management success across the three stakeholder groups, multiple regression analyses suggested significant variations. This study is amongst the first carried out from the perspectives of clients, consultants and contractors in Sri Lanka. The findings illustrate the priorities placed on the key project components by clients, consultants and contractors, which could inspire further research and may provide some guidance to the construction industry in understanding and managing the expectations of different stakeholder groups to achieve project management success.

Introduction

Project management success is a multi-dimensional concept encompassing many attributes, including technology, human control, finance, stakeholders and environment (Demilliere, 2014; Dinsmore & Cabanis-Brewin, 2011; Pitroda et al., 2016). Amongst the attributes, Silva, et al., (2015) single out people, i.e., the key groups within the construction sector, as critical to project management success.

Westerveld (2003) highlighted project clients as a key stakeholder group influencing project success, whereas other studies (Banki et al., 2009; Li et al., 2005; Ng et al., 2009; Palaneeswaran & Kumaraswamy, 2001) have acknowledged the contributions of consultants and contractors. These key stakeholders play vital roles in determining the direction and approach of projects, as well as project management success (Wong, 2004). Given the vast resources ploughed into planning and implementation of construction activities, project management success in terms of meeting cost, schedule and quality requirements is critical for the infrastructural and economic growth of any country.

This study aims to investigate how each of the three key stakeholder groups (clients, consultants and contractors) perceive and rate the critical success factors (CSFs) of key project components influencing project management success in Sri Lanka. Recognisingthat there are no universally accepted sets of CSFs for projects (Dvir et al., 1998; Hyvari,2006; Yong & Nur Emma, 2013), the study has identified five key project components influencing project management success, namely project design document, project human resources management, stakeholder management, project budget and efficient project management. Data were collected from a cross-section of project management personnel working in 20 major clients, consulting and construction companies in Sri Lanka through self-administered questionnaires. The findings are expected to shed light on how the clients, consultants and contractors perceive and rate the CSFs of key project components influencing project management success, allowing for a better understanding of the motivations of the key stakeholders and in managing them to achieve project management success.

The remaining paper is structured as follows. The next section reviews the literature, resulting in the formulation of a research framework and hypotheses. The methodology used is described next, followed by the analysis of the data collected. Theoretical and practical implications are then discussed before the paper is concludedwith recommendations and future research directions.

Review of Literature

Project Success and Project Management Success

The success of construction projects refers to the satisfactory achievement of the objectives defined in project specifications (Doloi et al., 2012). In contrast, project management success is defined as meeting project objectives within allocated budget, schedule and acceptable quality to the satisfaction of all stakeholders (Bajjou et al., 2017; Frimpong et al., 2003). This study adopts this definition of project management success.

Critical Success Factors of Key Project Components

Koutsikouri, et al., (2008) highlight that despite the numerous techniques and tools available to project managers, they continue to struggle to successfully complete projects. This points to the need to consider the application of CSFs in project management.

CSFs are defined as factors that project managers must have control over to achieveproject management success (Rockart, 1979). Based on the review of literature, the keyproject components identified include project design document, project human resources management, stakeholder management, project budget and efficient project management.

Many studies found that well-formulated project design packages are critical to project management success (Chan & Kumarasamy, 1997; Chan & Yeong, 1995; Toor & Ogunalana, 2008). In fact, poor initial design and/or design changes have been frequently cited as a cause of project delays and budget overruns, leading to either rework or a new design as evident from many megaprojects around the world (Abdul- Rahman et al., 2015; Ghazali, 2015; Hamilton, 2007; Maqsoom et al., 2018; Mohamed, 2001; Mpofu et al., 2017; Orangi et al., 2011; Toor and Ogunalana, 2008). Bedelin (1996) concludes that the time spent on the development of design, use of proper and detailed design procedures and standards after considering different options, lessons from past projects, environmental concerns, design complexity, as well as the availability of new technologies and sufficient quality control are amongst the CSFs. Other CSFs include the availability of skilled staff collaborating on project design (Gero, 1990; Ogwueleka, 2013), availability of detailed specifications (Haider et al., 2011), management support and striking a balance of cost, time and quality. To effectively develop a useful design package, all three key groups of participants (clients, consultants and contractors) must provide support in terms of the input requirements to the project design package. During the initial stage of design formulation, proper communication is vital to incorporate the requirements of clients and other stakeholders such as the public and consultants. In addition, the design teams must agree on the key basis of design, i.e., codes and standards, design parameters, types of documentation and risk analysis (Haider et al., 2011).

Project human resources management is another key project component associated with project management success (Doloi et al., 2012; Odeh & Battaineh, 2002). According to Verma (1995, 1996), leadership qualities and effective management of human resources are amongst the essential factors, including sufficient management support for projects and availability of competent project teams through access to and continuous monitoring of skilled resources (Belassi & Tukel, 1996; Maqsoom et al., 2018; Sambasivan et al., 2017), as well as recognition provided in the form of bonuses and promotion (Cooke-Davies, 2002). Along with this is the training provided to project team members not only from the technical perspective but also in ensuring that appropriate attitudes are inculcated. The importance of project human resources management to project management success was reported by all the key groups involved in projects, i.e., owners, consultants and contractors (Sambasivan & Soon, 2007). Specifically, the consultants and contractors reported that a shortage of skilled labour (Durdyev et al., 2017) and poor technical performance (Maqsoom et al., 2018) as the major contributors to project delays.

One major reason reported for project failures in developing countries is the poor management of stakeholders and not meeting their expectations (Davis, 2014; Eyiah- Botwe, 2015). Many studies have stressed that recognising the important role played by different stakeholders and managing them accordingly is important for project management success (Durdyev, 2020; Jepsen & Eskerod, 2009; Jergeas et al., 2000; Liang et al., 2017; Nguyen et al., 2019; Ogwueleka, 2013; PWC, 2018). Because poor stakeholder management has an impact specifically on contractors, causing project delays (Durdyev et al., 2017), the literature has documented the important role played by management of construction companies in educating their stakeholders on project- related matters, holding continuous discussions with them to know their needs, as well as updating them periodically to win their commitments and for them to make timely decisions (Durdyev, 2020). At the same time, it is also imperative for management to understand the local environmental conditions where projects without support from external stakeholders will experience major barriers (Aapaoja & Haapasalo, 2014; Gudiene et al., 2013; Mok et al., 2015).

Many studies have also found a strong correlation between project budget and project management success (Toor & Ogunlana, 2008; Viles et al., 2019; Yong & Nur Emma, 2012; Silva et al., 2015) where project budget has been identified as a critical component to clients, consultants and contractors (Bagaya & Song, 2016; Durdyev et al., 2017). Having a sufficient allocation of budget with sufficient contingencies for different stages of project activities (Chen et al., 2019), proper cash flow management (Viles et al., 2019) and close monitoring and management of budget allocation (Durdyev et al., 2017; Odeh & Battaineh, 2002; Sambasivan et al., 2017) are critical. Similarly, having skilled people with experience in adopting recognisable cost estimating methods by taking into consideration historical data, external interference and different phases of project activities, as well as monitoring budget allocation are also found to be important to project management success (Vasista, 2017). Efficient project management has also been recognised as a key requirement for project management success (Ballard & Koskela, 1998; Cooke-Davies, 2014; Haider et al., 2011; Hamilton, 2007; Mohandas & Sankaranarayan, 2008). Accordingly, the experience, managerial skills and commitment of project managers, as well as their technical backgrounds and capabilities have been identified as critical factors leading to efficient project management (Aneesha & Haridharan, 2017; Leung et al., 2009; Taherdoost & Keshavarzsaleh, 2016) and subsequently project management success. The ability of project managers to plan, manage and coordinate projects, resources, finances and stakeholders, control of project variations, make quick decisions, as well as to communicate, motivate and train team members are reported to be amongst the more important pre-requisites to efficiently manage projects, leading to project management success (Kezsbom et al., 1989; Mandson & Selnes, 2015; Newton, 2009). Besides, & Durdyev et al., (2017) add good quality control and safety applications to the list of CSFs for efficient project managers. Bajjou, et al., (2017) found that efficient project management is very important especially for contractors to avoid project delays.

Brief Overview of Studies Relating to Clients, Consultants and Contractors

Based on the five key project components, the researchers attempted to identify studies that have included all the three stakeholder groups of clients, consultants and contractors. Except for stakeholder management, the other four key project componentshave been examined as shown in Table 1. Although clients, consultants and contractorsare considered as the key stakeholders, there are many other stakeholders in a project management environment such as the government, environmentalists and the general public. This justifies the inclusion of this component of stakeholder managementalongside other key project components.

| Table 1 Studies Relating to the Key Project Components and Stakeholder Groups |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Project Components | Clients | Consultants | Contractors | Researchers |

| Project Design | Yes | Yes | Yes | Baldwin et al. (1971) |

| Document | Yes | Yes | Yes | Frimpong et al. (2003) |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Frimpong and Oluwoye (2018) | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Mpofu et al. (2017) | |

| Project Human | Yes | Yes | Yes | Baldwin et al. (1971) |

| Resources | Yes | Yes | Yes | Bagaya and Song (2016) |

| Management | Yes | Yes | Yes | Durdyev et al. (2017) |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Frimpong et al. (2003) | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Frimpong and Oluwoye (2018) | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Odeh and Battaineh (2002) | |

| Project Budget | Yes | Yes | Yes | Arya and Kansal (2016) |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Bagaya and Song (2016) | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Durdyev et al. (2017) | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Frimpong et al. (2003) | |

| Efficient Project | Yes | Yes | Yes | Frimpong et al. (2003) |

| Management | Yes | Yes | Yes | Frimpong and Oluwoye (2018) |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Mpofu et al. (2017) | |

| Stakeholder | No studies | |||

The studies shown in Table 1 have also confirmed the four key project components as influencing project management success by the three stakeholder groups although their ratings and contexts differ. For instance, in the studies of Baldwin et al., (1971); Battaineh & Odeh (2002), project human resources management was identified as a more critical factor, whereas Arya & Kansal (2016); Bagaya & Song (2016) identified project budget, and Mpofu, et al., (2017) discovered project design document as amongst the primary factors. Efficient project management is another critical component cited across studies (Durdyev et al., 2017; Frimpong et al., 2003; Frimpong & Oluwoye, 2018; Mpofu et al., 2017). Both project budget and project design document have been identified as more important factors by clients. For consultants, the more important factors include project budget and project human resources management which enable them to prepare project design documents, whereas project design document, project human resources management and project budget are the more important factors to the contractors. Besides project budget, all the three key stakeholders have also reported on the importance of efficient project management to project management success.

Since these studies were conducted in the contexts of developed and developing countries, it is plausible to conclude that technical and administrative concerns are moreobvious in projects of developed countries. However, projects in developing countries are confronted with additional challenges such as insufficient funding, a lack of resources and skilled personnel, project management deficiencies and inadequate planning. Exploring the component of stakeholder management alongside the four keyproject components on the three key stakeholder groups will contribute to the existing studies.

Framework and Hypotheses

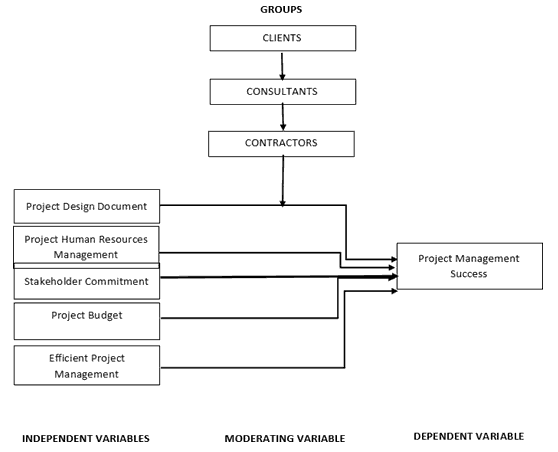

Figure 1 shows the framework of the study. Project design document, project human resources management, stakeholder management, project budget and efficient project management represent the independent variables, whereas project management success is the dependent variable. The three stakeholder groups serve as the moderating variables.

Based on the research framework, the following hypotheses were formulated.

H1: There is a significant relationship between the independent variables and thedependent variable.

H2: Clients significantly moderate the relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variable.

H3: Consultants significantly moderate the relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variable.

H4: Contractors significantly moderate the relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variable.

H5: There is a significant relationship amongst the three stakeholder groups.

Methodology

Data Collection and Analysis

The study uses a survey questionnaire to collect data. The questionnaire has two sections. The first section collects the demographic information of respondents. The second section comprises 58 questions on the CSFs of key project components and project management success, using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree (see Appendix 1).

Population, Categorisation and Sample Size

About 20 major institutions involved in the construction industry in Sri Lanka were selected for data collection, whereby five institutions represent clients, five institutionsrepresent consultants and 10 institutions represent construction organisations. The employee register of each of the institutions was used to select the survey participants. Questionnaires were distributed to 600 personnel working as project directors, project managers, senior project engineers, senior engineers and some senior technical staff working on-site and in offices.

A total of 233 responses were received, yielding a response rate of 38.8% which met the minimum requirement of 234 (Sekaran, 2009). The respondents included 60, 33 and 140 individuals representing clients, consultants and contractors, respectively. Table 2 shows the demographic profile of the respondents. Consistent with the nature of the industry, most respondents were male across the three groups of stakeholders. The majority of them were married and between the ages of 30 and 49. Most of the personnel working for clients and contractors possess a Bachelor’s degree, whereas theconsultants have a Master’s degree. Many of them were members or graduate membersof relevant professional bodies. The number of years in service and years with organisations indicated the extent of experience of the respondents in project management. Most of the respondents representing the clients were project managers and senior project engineers focusing on the costing and scheduling of projects. Many of them representing the contractors and consultants were project engineers, senior project engineers and project managers. The distribution of respondents shows a good indication of the representativeness of the sample size of the population of the key groups.

| Table 2 Demographic Profile of Respondents |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Variables | Clients | Consultant | Contractor | Grand Total | |||||

| Total | % | Total | % | Total | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 52 | 86.7 | 30 | 90.9 | 120 | 85.7 | 202 | 86.7 |

| Female | 8 | 13.3 | 3 | 9.1 | 20 | 14.3 | 31 | 13.3 | |

| Age | 30 - 39 | 18 | 30.0 | 6 | 18.0 | 58 | 41.4 | 82 | 35.2 |

| 40 - 49 | 25 | 41.0 | 14 | 42.4 | 56 | 40.0 | 95 | 40.8 | |

| 50 - 59 | 12 | 20.0 | 9 | 27.2 | 24 | 17.1 | 45 | 19.3 | |

| Above 60 | 5 | 8.3 | 4 | 12.1 | 2 | 1.4 | 11 | 4.7 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 53 | 88.3 | 26 | 78.8 | 112 | 80.0 | 191 | 82.0 |

| Single | 7 | 11.7 | 7 | 21.2 | 28 | 20.0 | 42 | 18.0 | |

| Education | Diploma | - | - | - | - | 22 | 15.7 | 22 | 9.4 |

| Bachelors | 30 | 50.0 | 10 | 30.3 | 80 | 57.1 | 120 | 58.4 | |

| Masters | 20 | 33.3 | 18 | 54.5 | 34 | 24.3 | 72 | 26.2 | |

| MBA | 10 | 16.6 | 5 | 15.1 | 4 | 2.9 | 19 | 4.7 | |

| Professional Qualifications | Fellow | 5 | 8.3 | 3 | 9.1 | - | - | 8 | 3.4 |

| Member | 45 | 75.0 | 20 | 60.6 | 43 | 30.7 | 108 | 46.3 | |

| Graduate Member | 10 | 16.7 | 10 | 30.3 | 97 | 69.3 | 117 | 50.2 | |

| No. of Years in Service | 5-9 | 18 | 30.0 | 3 | 9.1 | 40 | 28.6 | 61 | 26.2 |

| 10-14 | 12 | 20.0 | 20 | 60.6 | 38 | 27.1 | 70 | 30.0 | |

| 15-19 | 23 | 38.3 | 7 | 21.2 | 42 | 30.0 | 72 | 30.9 | |

| Above 20 | 7 | 11.7 | 3 | 9.1 | 20 | 14.3 | 30 | 12.9 | |

| No. of Years with the Organisation | 2-4 | 8 | 13.3 | - | - | 32 | 22.9 | 40 | 17.2 |

| 5-7 | 18 | 30.0 | 5 | 15.1 | 42 | 30.0 | 65 | 27.9 | |

| 8-12 | 14 | 23.4 | 10 | 30.3 | 28 | 20.0 | 52 | 22.3 | |

| 13-15 | 12 | 20.0 | 12 | 36.4 | 17 | 12.1 | 41 | 17.6 | |

| Above 16 | 8 | 13.3 | 6 | 18.2 | 21 | 15.0 | 35 | 15.0 | |

| Current Position |

Project Director | 9 | 15.0 | 6 | 8.1 | 15 | 10.7 | 15 | 6.43 |

| Project Manager | 18 | 30.0 | 7 | 21.2 | 26 | 18.5 | 71 | 30.5 | |

| Senior Project Engineer | 18 | 30.0 | 10 | 30.2 | 24 | 17.1 | 31 | 13.3 | |

| Project Engineer | - | - | - | - | 44 | 31.4 | 27 | 11.6 | |

| Senior Engineer | 3 | 5 | 7 | 21.2 | 17 | 12.1 | 43 | 18.5 | |

| Planning/Scheduling Engineers |

12 | 20.0 | 3 | 9.0 | 14 | 10.0 | 46 | 19.7 | |

Goodness of Data

Table 3 displays the results of confirmatory factor analysis using principal component analysis and varimax rotation. The minimum factor loadings and average variance extended (AVE) values were within a reasonable range, confirming the sufficiency of the validity of the model. Two key project components (project design document and stakeholder management) were each sub-divided into three sub-components, whilst the remainder remained intact. The three sub-components of project design document consist of: (1) design package initiation, data collection methods on designs and management support (PDDf1); (2) economic and technical considerations during the preparation of project design documents (PDDf2); and (3) time spent and methods of design preparation and availability of skilled personnel (PDDf3). The three subcomponents of stakeholder management are: (1) stakeholder strengths, financial commitment and attitude to risks (SMf1); (2) commitment to the success of the project (SMf2); and (3) expectations on benefits and recognition of projects (SMf3). Three items from project human resources management, one item from stakeholder management and four items from efficient project management were eliminated from the analysis (see Appendix 1).

| Table 3 Summary of Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Summary CFA | |||

| Final Measurement Items for Variables | Minimum Factor Loadings | AVE | Final Measurement Model Validity |

| PDDf1 | .885* | 0.817 | Sufficient |

| PDDf2 | .696* | 0.630 | Sufficient |

| PDDf3 | .900* | 0.857 | Sufficient |

| PRMf | .874* | 0.807 | Sufficient |

| PBf1 | .886* | 0.870 | Sufficient |

| PME | .904* | 0.830 | Sufficient |

| SMf1 | .796* | 0.783 | Sufficient |

| SMf2 | .767* | 0.727 | Sufficient |

| SMf3 | .851* | 0.790 | Sufficient |

Table 4 shows that the Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin (KMO) values of all the factors were above 0.50, assuring the validity of the constructs in the study. The Bartlett’s test results were also significant at 0.05 level. Internal consistency was measured through Cronbach’s Alpha, with values closer to 0.70 or above.

| Table 4 Reliability and Validity Analysis |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validity | Reliability | |||||

| No. of items | KMO test |

Bartlett’s test | Cronbach’s Alpha | |||

| Chi-value | Sig. | |||||

| Factor 1 | 5 | 0.781 | 211.291 | 0.00 | 0.723 | |

| Project Design Document | Factor 2 | 4 | 0.745 | 166.221 | 0.00 | 0.717 |

| Factor 3 | 3 | 0.699 | 112.121 | 0.00 | 0.697 | |

| Project Human Resources Management | Factor 1 | 5 | 0.708 | 273.70 | 0.00 | 0.731 |

| Project Budget | Factor 1 | 8 | 0.787 | 369.118 | 0.00 | 0.759 |

| Factor 1 | 4 | 0.717 | 190.018 | 0.00 | 0.731 | |

| Stakeholder Management | Factor 2 | 3 | 0.694 | 142.294 | 0.00 | 0.683 |

| Factor 3 | 3 | 0.664 | 139.342 | 0.00 | 0.681 | |

| Efficient Project Management | Factor 1 | 6 | 0.834 | 416.272 | 0.00 | 0.813 |

Table 5 shows the means and standard deviation scores for the key project components across the three stakeholder groups. All the three groups showed higher mean scores for SMf2 of stakeholder management (commitment of stakeholders to thesuccess of the project), PDDf2 of project design document (economic and technical considerations during the preparation of project design documents), project budget andefficient project management.

| Table 5 Means and Standard Deviations Scores of Csfs for All Three Stakeholder Groups |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clients | Consultants | Contractors | |||||||

| Mean | S.D. | Means Rating |

Mean | S.D. | Means Rating |

Mean | S.D. | Means Rating |

|

| PDDf1 | 4.06 | 0.582 | 8 | 4.07 | 0.418 | 9 | 4.09 | 0.459 | 8 |

| PDDf2 | 4.28 | 0.550 | 3 | 4.39 | 0.408 | 2 | 4.39 | 0.530 | 2 |

| PDDf3 | 4.10 | 0.488 | 7 | 4.12 | 0.368 | 7 | 4.04 | 0.486 | 9 |

| PRM | 4.12 | 0.402 | 5 | 4.31 | 0.455 | 4 | 4.21 | 0.430 | 5 |

| PB | 4.45 | 0.523 | 1 | 4.31 | 0.483 | 5 | 4.40 | 0.539 | 1 |

| SMf1 | 3.96 | 0.525 | 9 | 4.11 | 0.552 | 8 | 4.12 | 0.489 | 7 |

| SMf2 | 4.42 | 0.416 | 2 | 4.49 | .0435 | 1 | 4.38 | 0.469 | 3 |

| SMf3 | 4.12 | 0.465 | 6 | 4.28 | 0.472 | 6 | 4.19 | 0.468 | 6 |

| PME | 4.26 | 0.380 | 4 | 4.34 | 0.402 | 3 | 4.34 | 0.398 | 4 |

The four factors which scored above the mean scores for the clients included projectbudget, SMf2, PDDf2 and efficient project management. The consultants rated SMf2 as the highest, followed by PDDf2, efficient project management, project human resourcesmanagement, project budget and stakeholder management of SMf3 (expectations of stakeholders on the benefits and recognition of projects) as the six factors which scored above the average mean score. The contractors, on the other hand, rated project budget, PDDf2, SMf2 and efficient project management as the four factors which scored abovethe average mean scores. The lowest mean score was recorded under stakeholder management of SMf1 (stakeholder strengths, financial commitment and attitude to risks) by clients. However, since the mean score was close to 4, all the factors were rated highly by the three stakeholder groups. By comparing amongst the three key stakeholdergroups, clients rated project budget and PDDf3 higher than the average mean. Except for project design document of PDDf1 (design package initiation, data collection methods on designs and management support) and project budget, all the factors were rated higher than the average mean by consultants. For contractors, project budget, PDDf2, efficient project management, SMf1 and PDDf1 were rated higher than the average mean. The standard deviation values for all factors were less than one, indicating consistency in the ratings by respondents.

Findings

Table 6 shows the results of the Pearson correlation coefficient between the key project components and project management success amongst the three key stakeholder groups.In view of the significance of the relationships, H1 is accepted.

| Table 6 Results of Pearson Correlation Coefficient Between the Key Project Components And Project Management Success For All Three Stakeholder Groups |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation with Project Management Success | ||||||

| Clients | /th> | Contractors | Consultants | |||

| Factors | Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient |

P-Value | Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient |

P-Value | Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient |

P-Value |

| PDDf1 avg. | 0.465 | 0.000 | 0.538 | 0.000 | 0.369 | 0.000 |

| PDDf2 avg. | 0.457 | 0.000 | 0.598 | 0.000 | 0.484 | 0.000 |

| PDDf3 avg. | 0.243 | 0.000 | 0.365 | 0.000 | 0.308 | 0.000 |

| PRM avg. | 0.490 | 0.000 | 0.417 | 0.000 | 0.535 | 0.000 |

| PB avg. | 0.687 | 0.000 | 0.536 | 0.000 | 0.604 | 0.000 |

| SMf1 avg. | 0.519 | 0.000 | 0.392 | 0.000 | 0.471 | 0.000 |

| SMf2 avg. | 0.232 | 0.000 | 0.426 | 0.000 | 0.444 | 0.000 |

| SMf3 avg. | 0.327 | 0.000 | 0.376 | 0.000 | 0.268 | 0.000 |

| PME avg. | 0.588 | 0.000 | 0.248 | 0.000 | 0.565 | 0.000 |

To test H2 to H4, multiple linear regression analyses were performed on each key stakeholder group. Table 7 shows that the client group only moderated the relationshipbetween project budget and project management success. Hence, H2 is partially accepted. The variation inflation factor (VIF) was less than 10, indicating that multicollinearity was not an issue.

| Table 7 Results of Multiple Regression Analysis between Csfs of Project Components and Project Management Success (For Clients) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Standardised Coefficients | t | Sig. | VIF | |

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| Model Accuracy=44.5% | ||||||

| (Constant) | 1.848 | 0.368 | 5.018 | 0.000 | ||

| PB avg. | 0.629 | 0.088 | 0.674 | 7.121 | 0.000 | 2.54 |

As shown in Table 8, the consultant group only moderated the relationships between project budget, PDDf2 (economic and technical considerations during the preparation of project design documents) and project management success. The VIF was again found to be less than 10. Hence, H3 is also partially accepted.

| Table 8 Results of Multiple Regression Analysis Between Csfs of Project Components ond Project Management Success (For Consultants) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Standardised Coefficients | t | Sig. | VIF | |

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| Model Accuracy=54.9% | ||||||

| (Constant) | 0.922 | 0.591 | 1.559 | 0.131 | ||

| PB avg. | 0.512 | 0.142 | 0.527 | 3.614 | 0.001 | 2.66 |

| PDDf2 avg. | 0.311 | 0.129 | 0.350 | 2.399 | 0.024 | 2.12 |

The contractor group only moderated the relationships between project budget, project human resources management and project management success as seen in Table 9. Similarly, the VIF was less than 10. As a result, H4 is partially accepted.

| Table 9 Results of Multiple Regression Analysis Between Csfs of Project Components and Project Management Success (For Contractors) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Standardised Coefficients | t | Sig. | VIF | |

| B | Std.Error | Beta | ||||

| Model Accuracy=42.4% | ||||||

| (Constant) | 1.477 | 0.298 | 4.949 | 0.000 | ||

| PB avg. | 0.450 | 0.078 | 0.464 | 5.772 | 0.000 | 2.62 |

| PRM avg. | 0.259 | 0.079 | 0.265 | 3.290 | 0.001 | 2.28 |

Table 10 shows the ANOVA results where the relationships amongst the three groups were not significant. Hence, H5 is not accepted.

| Table 10 Anova Results for Clients, Consultants and Contractors |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of Squares |

df | Mean Square |

F | Sig. | ||

| PMS | Between Groups | .034 | 2 | .017 | .114 | .892 |

| Within Groups | 33.493 | 222 | .151 | |||

| Total | 33.528 | 224 | ||||

| QDDf1 | Between Groups | .090 | 2 | .045 | .167 | .846 |

| Within Groups | 59.910 | 222 | .270 | |||

| Total | 60.000 | 224 | ||||

| QDDf2 | Between Groups | .124 | 2 | .062 | .257 | .774 |

| Within Groups | 53.513 | 222 | .241 | |||

| Total | 53.637 | 224 | ||||

| QDDf3 | Between Groups | .738 | 2 | .369 | 1.320 | .269 |

| Within Groups | 62.101 | 222 | .280 | |||

| Total | 62.840 | 224 | ||||

| PRM | Between Groups | .613 | 2 | .307 | 1.783 | .170 |

| Within Groups | 38.157 | 222 | .172 | |||

| Total | 38.770 | 224 | ||||

| PB | Between Groups | .265 | 2 | .132 | .745 | .476 |

| Within Groups | 39.454 | 222 | .178 | |||

| Total | 39.719 | 224 | ||||

| SMf1 | Between Groups | .903 | 2 | .452 | 1.774 | .172 |

| Within Groups | 56.532 | 222 | .255 | |||

| Total | 57.435 | 224 | ||||

| SMf2 | Between Groups | .205 | 2 | .103 | .509 | .602 |

| Within Groups | 44.741 | 222 | .202 | |||

| Total | 44.946 | 224 | ||||

| SMf3 | Between Groups | .505 | 2 | .252 | 1.129 | .325 |

| Within Groups | 49.655 | 222 | .224 | |||

| Total | 50.160 | 224 | ||||

| PME | Between Groups | .257 | 2 | .128 | .846 | .431 |

| Within Groups | 33.678 | 222 | .152 | |||

| Total | 33.935 | 224 | ||||

Taking a closer look, the results of multiple regression in Table 11 showed no significant relationship between the three groups of stakeholders (clients, consultants and contractors) and project management success.

| Table 11 Results Of Multiple Regression On The Moderating Variables |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Coefficients | Unstandardised | Standardised Coefficients | Collinearity Statistics | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | t | Sig. | Tolerance | VIF | |

| Clients | 0.72 | .045 | -.082 | 1.066 | .110 | .907 | 1.103 |

| Consultants | -.026 | .059 | 0.023 | .446 | .656 | .897 | 1.115 |

| Contractors | .026 | .059 | .033 | .446 | .656 | .421 | 2.374 |

Discussion and Implications

This study has achieved its objective of determining the perception of Sri Lankan clients, consultants and contractors on the CSFs of key project components influencing project management success. The research was based on an extensive review of literature, resulting in the development of a research framework and subsequently the survey instrument which was then validated. Although it involved responses from different stakeholders and in different numbers (60 represented clients, 33 represented consultants and 140 represented contractors), the ANOVA results have provided confirmation on the insignificant differences in their responses to the key project components influencing project management success.

The hypotheses were developed under the assumption that all the key project components are perceived as important by the three key stakeholder groups as reflected in the literature (Table 1) except for stakeholder management which was examined inthis study. This has in fact been confirmed by the responses across the three groups(Table 5). Except for SMf1 of stakeholder management (stakeholder strengths, financial commitment and attitude to risks) which scored a mean of 3.96 by clients, all the otherkey project components scored means above 4 out of 5. Likewise, the results have been affirmed by the Pearson correlation coefficient analysis (Table 6). This makesreasonable sense given that the CSFs of key project components were identified fromstudies related to the construction sector. Therefore, the significance of the key projectcomponents and their associations with project management success is to be expected. However, the results of multiple regression analyses fetched interesting findings.

Project budget was found to be a significant key project component across all three stakeholder groups. In fact, it was the only significant component highlighted by the client group. The consultants perceived the economic and technical considerations during the preparation of project design documents as another significant component, whereas the contractors perceived project human resources management as an important one. The findings are reflective of the scenario in Sri Lanka where project budget is given the top priority by different stakeholders (Arya & Kansal, 2016; Bagaya & Song, 2016) such as clients and contractors in this study (Table 5). This is not difficult to comprehend given that clients must carefully come up with a project budget and thatthe contractors rely heavily on funds to carry out their work. It could also imply that although the Sri Lankan clients acknowledge the importance of the other key project components, they are delegating all the other obligations to the consultants and contractors.

The consultants, on the other hand, also believe that project budget as a more significant component (Table 8) although this is not reflected in the mean score (Table 5). In addition, they are also of the view that the preparation of design documents considering economic and technical considerations is important to them, lending partial support to the works of Mpofu et al., (2017), as well as other researchers in this context (Baldwin et al., 1971; Frimpong et al., 2003; Frimpong & Oluwoye, 2018). It makes sense for the consultants to view project design documents as an important factor given that design constitutes their primary area of work. However, what is intriguing in this study is that the key project component of project design document has been sub-divided into three components, where the design package initiation, data collection methods on designs and management support (PDDf1) and time spent and methods of design preparation and availability of skilled personnel (PDDf3) were not thought to be as significant as the detailed specifications with a balance of cost and time with quality control procedures (PDDf2). This could be analogous to the adage ‘you get what you pay for’.

Similarly, the contractors regarded project human resources management as a significant component although this is not reflective of the mean score. Corroborating Baldwin, et al., (1971); Battaineh & Odeh (2002), the findings made reasonable sense since the contractors are the ones responsible for carrying out the projects. Hence,they must have appropriate resources to manage the contracts, including an excellent project budget and cash flow management.

What remains interesting is whose responsibility it is for the other key project components. This is most likely the reason why many projects in Sri Lanka are still not meeting its objectives of cost, time and quality as pointed out in several studies (De Silva et al., 2008; Gunathilaka et al., 2013; Silva et al., 2015). Although the researchers hypothesised that stakeholder management is a key project component that should be included in studies of such nature, the findings failed to show any significance despite the high rating of SMf2. The same can be said for efficient project management which has recorded somewhat high ratings too. Having said that, the mean ratings could be used as a supplement to the multiple regression analysis to better understand the motivations of the three stakeholder groups and to better manage them through their interactions with the key project components to achieve project management success.

The findings have the following theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical Implications

Although research on key project components influencing project management success from the lens of diverse stakeholder groups is not new, no such studies have been undertaken in Sri Lanka so far. This study has also attempted to incorporate stakeholder management into the equation although no significant association was recorded. Having stated that, the study has developed a comprehensive model of five key project components and their associated CSFs for the construction setting as evident from the mean scores and the results of the correlational analysis.

What is perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the study is the findings from the three stakeholder groups. This necessitates the replication of similar research with the same or expanded numbers of key project components, especially amongst the developing countries, with comparison studies possible. Adding to this is the focus of this study on large clients, consulting and construction companies in Sri Lanka which are involved in managing complex and large projects and which requires collaboration across the different stakeholder groups (clients, consultants and contractors). In conjunction with this, it is interesting to examine the relationships when medium and smaller size companies and different external stakeholders are considered.

Practical Implications

From a practical standpoint, this study has identified several key project components that must be properly understood and managed to achieve project management success. To begin with, project budget is essential from every angle of any project and stakeholder group (Bagaya & Song, 2016; Durdyev et al., 2017). Clients of projects must recognise the significance of employing skilled and qualified personnel to develop a realistic budget. This is on top of making references to past projects of what worked and what did not due to budget deficiencies. Soliciting feedback from consultants and perhaps contractors whilst developing the budget is recommended. Similarly, contractors must employ skilled and competent personnel to develop an efficient allocation and control of funds, as well as set aside some contingency funds to cover unforeseen expenses (Chen et al., 2019; Odeh & Battaineh, 2002; Sambasivan et al., 2017). Meeting this requirement has proven to be the most difficult aspect of project management, particularly the developing countries. The CSFs proposed in this study could be used as a reference to mitigating any budgetary challenge that may arise.

It is also imperative for project owners or clients to recognise the importance of allocating sufficient budget for project design by consultants, with an emphasis on detailed design specifications that consider technical and economic considerations, in which its effectiveness in preventing cost overruns, schedule delays and sub-standard output has been documented (Flyvbjerg, 2004). The CSFs proposed in this study could serve as a guide to consultants in developing a proper project design document. In addition, it is worth noting that constant communication with clients, especially during the early stages of design formulation, is crucial to ensuring that the requirements of clients are incorporated into the detailed project specifications.

The contractors, on the other hand, would require effective management of their human resources, including ensuring the availability of competent project teams responsible for carrying out projects. This entails an effective recruitment and selection practice, continuous training and development, as well as constant monitoring of skilled resources (Durdyev et al., 2017; Maqsoom et al., 2018; Sambasivan & Soon, 2007). Indeed, a strategic approach to managing and allocating resources is critical, particularly in Sri Lanka, where skills shortage has delayed many construction projects (Praveen et al., 2013).

Conclusion, Limitations and Future Research Directions

The research has provided useful insights into the key project components influencing project management success from the perspective of the three key stakeholder groups. It is hoped that the insights and recommendations provided will assist the stakeholdersto focus on what is genuinely necessary to achieve project management success. Collaboration amongst the key stakeholder groups in the implementation of the CSFs could lead to project success and significant development in Sri Lanka or any developing country.

The primary shortcoming of this research is that it only collected data from the Western province of the country, which is home to most large institutions. The other constraint was the number of key project components, which was limited to five.

Data collected from numerous institutions of varying sizes and locations across thecountry may yield different findings. Comparative studies are also possible to find solutions to broad concerns confronting emerging, developing and/or developed countries. Similarly, data can be collected from external stakeholders such as government agencies and environmentalists. Since this study focused only on five key project components, future research may broaden it to include environmental, information technology and/or other influences addressing the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals.

References

Aapaoja, A., & Haapasalo, H. (2014). “A framework for stakeholder identification and classification in construction projects”, Open Journal of Business and Management, 2(1), 43-55.

Abdul-Rahman, H., Wang, C., & Yap, J.B.H. (2015), “Impacts of design changes on construction project performance: Insights from a literature review”, in Proceedings of the 14th Management in Construction Research Association Conference and Annual General Meeting, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Aneesha, K., & Haridharan, M.K. (2017), “Ranking the project management success factors for construction projects in South India”, in Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environment Science, 80(1), 012044.

Arya, A., & Kansal, R. (2016), “Analysing delays of construction projects in India: Causes and effects”, International Journal of Science Technology & Engineering, 3(6).

Bagaya, O., & Song, J. (2016). “Empirical study of factors influencing schedule delays of public construction projects in Burkina Faso”, Journal of Management in Engineering, 32(5), 05016014.

Bajjou, M.S., Chafi, A., & En-Nadi, A. (2017). “The potential effectiveness of lean construction tools in promoting safety on construction sites”, International Journal of Engineering Research in Africa,33, 179-193.

Baldwin, J., Manthei, J., Rothbart, H., & Harris, R.B. (1971). “Causes of delay in the construction industry”, Journal of the Construction Division, 97(2), 177-187.

Ballard, G., & Koskela, L. (1998). “On the agenda of design management research”, in Proceedings of the 6th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, Guaruja, Brazil, 52-69.

Banki, M.T., Hadian, S., Niknam, M., & Rafizadeh, I. (2009). “Contractor selection in construction projects based on a fuzzy AHP method”, in Proceedings of the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering Annual Conference 2009, St. Johns, Newfoundland.

Bedelin, H.M. (1996). “Successful major projects in a changing industry”, Civil Engineering, 55-63.

Belassi, W., & Tukel, O.I. (1996). “A new framework for determining critical success/failure factors in projects”, International Journal of Project Management, 4(3), 141-151.

Chan, A.P.C., & Oppong, G.D. (2017). “Managing the expectations of external stakeholders in construction projects”, Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 24(5), 736-756.

Chan, A.P.C., & Yeong, C.M. (1995). “A comparison of strategies for reducing variations”, Construction Management and Economics, 13(6), 467-473.

Chan, D.W.M. and Kumarasamy, M.M. (1997). “A comparative study of causes of time overruns in Hong Kong construction projects”, International Journal of Project Management, 15(1), 55-63.

Chen, G.X., Shan, M., Chan, A.P.C., Liu, X., & Zhoa, Y.Q. (2019). “Investigating the causes of delay in grain bin construction project: The case of China”, International Journal Construction Management, 19(1), 1-14.

Cooke-Davies, T. (2002). “The “real” success factors in projects”, International Journal of Project Management, 20(3), 185-190.

Cooke-Davies, T.J. (2014). “Sponsoring projects: Developing an organisational capability ”, in Proceedings of the 6th Concept Symposium on Projects Governance, Norway.

Davis, K. (2014). “Different stakeholder groups and their perceptions of project success”, International Journal of Project Management, 32(2), 189- 201.

De Silva, N., Rajakaruna, R.W.D.W.C.A.B., & Bandara, K.A.T.N. (2008). “Challenges faced by the construction industry in Sri Lanka: Perspective of clients and contractors”, Building Resilience, 158.

Demilliere, A.S. (2014). “The role of human resource in project management”, Romanian Distribution Committee Magazine, 5(1), 36-40.

Dinsmore, P.C., & Cabanis-Brewin, J. (2011), The AMA Handbook of Project Management, AMACOM American Management Association, New York, NY.

Doloi, H., Sawhney, A., Iyer, K.C., & Rentala, S. (2012). “Analysing factors affecting delays in Indian construction projects”, International Journal of Project Management, 30(4), 479-489.

Durdyev, S. (2020), “Review of construction journals on causes of project cost overruns”, Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management.

Durdyev, S., Shukla, S.K., Omarov, M., & Ismail, S. (2017). “Causes of delay in residential construction projects in Cambodia”, Cogent Engineering, 4(1), 1-8.

Dvir, D., Lipovetsky, S., Shenhar, A., & Tishler, A. (1998). “In search of project classification: A non-universal approach to project success factors”, Research Policy, 27(9), 915-935.

Eyiah-Botwe, E. (2015). “An evaluation of stakeholder management role in GETFund polytechnics projects delivery in Ghana”, Journal of Civil and Environmental Research, 7(3), 66-73.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2004). “Megaprojects and risks: A conversation with Bent Flyvbjerg”, Critical Planning, 11, 51-63.

Frimpong, Y., & Oluwoye, J. (2018). “Project management practice in ground water construction projects in Ghana”, American Journal of Management Science and Engineering,3(5), 60-68.

Frimpong, Y., Oluwoye, J., & Crawford, L. (2003). “Causes of delay and cost overruns in construction of groundwater projects in a developing country: Ghana as a case study”, International Journal of Project Management, 21(5), 321-326.

Gero, J.S. (1990). “Design prototypes: Aknowledge representation schema for design”, Artificial Intelligence Magazine, 11(4), 26-36.

Ghazali, R. (2015). “Transport Ministry: KLIA2 construction never experienced cost overruns”, The Star Online,

Gudiene, N., Banaitis, A., & Banaitiene, N. (2013). “Evaluation of critical success factors for construction projects: An empirical study in Lithuania”, International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 17(1), 21-31.

Gunathilaka, S., Tuuli, M.M., & Dainty, A.R. (2013). “Critical analysis of research on project success in construction management journals”, in Proceedings of the 29th Annual ARCOM Conference, 979-988.

Haider, N.I., Aziz, S., & Kashif-ur-Rehman. (2011). “The impact of stakeholder communication on project outcome”, African Journal of Business Management, 5(14), 5824-5832.

Hamilton, A. (2007), “Project design: task that need to be managed”, in Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Management, Procurement and Law, 160(1), 17-23.

Hyvari, I. (2006), “Project management effectiveness in project-oriented business organisations”, International Journal of Project Management, 24 No. 3, pp. 216-225.

Jergeas, G.F., Williamson, E., Skulmoski, G.J., & Thomas, J.L. (2000). “Stakeholder management on construction projects”, AACE International Transaction, 12(1), 1-6.

Jepsen, A.L., & Eskerod, P. (2009). “Stakeholder analysis in projects: challenges in using current guidelines in the real world”, International Journal of Project Management, 27(4), 335-343.

Kezsbom, D.S., Schilling, D.L., & Edward, K.A. (1989). Dynamic Project Management: A Practical Guide for Managers and Engineers, Wiley-Inderscience, New York, NY.

Koutsikouri, D., Austin, S.A., & Dainty, A.R.J. (2008). “Critical success factors in collaborative multi-disciplinary”, Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, 6(3), 198-226.

Leung, M.Y., Chan, Y.S., & Yu, J. (2009). “Integrated model for the stressors and stresses of construction project managers in Hong Kong”, Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 135(2), 126-134.

Li, Y.W., Chen, SY., & Nie, X.T. (2005). “Fuzzy pattern recognition approach to construction contractor selection”, Fuzzy Optimisation and Decision Making, 4, 103-118.

Liang, X., Yu. T., & Guo, L. (2017). “Understanding stakeholders’ influence on project success with a new SNA method: A case study of the green retrofit in China”, Sustainability, 9(10), 1-19.

Mandson, L., & Selnes, M. (2015). “Project management efficiency and effectiveness to improve project control in public sector”, unpublished Master’s thesis, NTNU Trondheim Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Maqsoom, A., Khan, M.U., Khan, M.T., Khan, S., & Ullah F. (2018). “Factors influencing the construction time and cost overrun in projects: Empirical evidence from Pakistani construction industry”, in Proceedings of the 21st International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate, Springer, Singapore, 769-778.

Mohamed, A.A. (2001), “Analysis and management of change orders for combined sewer over flow construction projects”, unpublished dissertation, Wayne State University.

Mohandas, V.P., & Raman, S.R. (2008). “Cost of quality analysis: Driving bottom-line performance”, International Journal of Strategic Cost Management, 3(2), 1-8.

Mok, K.Y., Shen, G.Q., & Yang, J. (2015). “Stakeholder management studies in mega construction projects: A review and future directions”, International Journal of Project Management, 33(2), 446-457.

Mpofu, B., Edward, G.O., Cletus, M., & Adriaan, P. (2017). “Profiling causative factors leading to construction project delays in the United Arab Emirates”, Engineering, Construction and Architect Management, 24(2), 346-376.

Newton, R. (2009). The Practice and Theory of Project Management: Creating Value Through Change, Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire.

Ng, S.T., Tang, Z., & Palaneeswaran, K. (2009). “Factors contributing to the success of equipment-intensive subcontractors in construction”, International Journal of Project Management, 27(7), 736-744.

Nguyen, T.H.D., Chileshe, N., Rameezdeen, R., & Wood, A. (2019). “Stakeholder influence strategies in construction projects”, International. Journal of Managing Project in Business, 13(1), 47-55.

Odeh, A.M., & Battaineh, H.T. (2002). “Causes of construction delay: Traditional contracts”, International Journal of Project Management, 20(1), 67- 73.

Ogwueleka, A.C. (2013). “A review of safety and quality issues in the construction industry”, JournalofConstructionEngineeringandProjectManagement, 3(3), 42-48.

Orangi, A., Palaneeswaran, E., & Wilson, J. (2011). “Exploring delays in Victoria- based Australian pipeline projects”, Procedia Engineering, 14, 874-881.

Palaneeswaran, E., & Kumaraswamy, M. (2001). “Recent advances and proposed improvements in contractor prequalification methodologies”, Building and Environment, 36(1), 73-87.

Pitroda, J.R., Makwana, A.H., & Prajapathi, N. (2016). “Analysis of factors affecting human resources management of construction firms using RII method, IMP.I method and RIR method”, in Proceedings of International Conference on Engineering: Issues, Opportunities and Challenges for Development. Umrakh, Bardoli: S.N. Patel Institute of Technology and Research Centre.

Praveen, R., Niththiyananthan, T., Kanarajan, S., & Dissanayake, P.B.G. (2013). “Understanding and mitigating the effects of shortage of skilled labour in the construction industry of Sri Lanka”, digital repository, University of Moratuwa.

PWC (2018). “Project success survey: Driving project success in Belgium”

Rockart, J.F. (1979). “Chief executives define their own data needs”, Harvard Business Review, 57(2), 81-93.

Sambasivan, M., Deepak, T.J., Salim, A.N., & Ponniah, V. (2017). “Analysis of delays in Tanzanian construction industry: Transaction cost economics (TCE) and structural equation modelling (SEM) approach”, Engineering, Construction and Architect Management, 24(2), 308-325.

Sambasivan, M., & Soon, Y.W. (2007). “Causes and effects of delays in Malaysian construction industry”, International Journal of Project Management, 25(5), 517-526.

Sekaran, U. (2009). Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach (4th ed., pp. 293-294), John Wiley & Sons, India.

Silva, G.A.S.K., Warnakulasuriya, B.N.F., & Arachchige, B.J.H. (2015). “Critical success factors for construction projects: A literature review”, in Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Business Management, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Taherdoost, H., & Keshavarzsaleh, A. (2016), “Critical factors that lead to projects’ success/failure in global marketplace”, Procedia Technology, 22, 1066- 1075.

Toor, S.U.R., & Ogunlana, S.O. (2008). “Problems causing delays in major construction projects in Thailand”, Construction Management and Economics, 26(4), 395-408.

Vasista, T.G.K. (2017). “Strategic cost management for construction project success: A systematic study”, Civil Engineering and Urban Planning: An International Journal, 4(1), 41-52.

Verma, V.K. (1996). Human Resource Skills for the Project Manager, Project Management Institute, Newton Square, Pennsylvania.

Verma, V.K. (1995). Organising Project for Success, Project Management Institute, Newton Square, Pennsylvania.

Viles, E.,Rudeli, N.C., & Santilli, A. (2019). “Causes of delay in construction projects: A quantitative analysis”, Engineering, Construction and ArchitecturalManagement, 27(4), 917-935.

Westerveld, E. (2003). “The project excellence model: Linking success criteria and critical success factors”, International Journal of Project Management, 21(6), 411-418.

Wong, C.H. (2004). “Contractor performance prediction model for the United Kingdom construction contractor: Study of logistic regression approach”, Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 130(5), 691-698.

Yong, Y.C., & Nur Emma, M. (2012), “Analysis of factors critical to construction project success in Malaysia”, Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 19(5), 543-556.

Yong, Y.C., & Nur Emma, M. (2013), “Critical success factors for Malaysian construction projects: An empirical assessment”, Construction Management and Economics, 31(9), 959-978.

Received: 30-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. JMIDS-21- 9945; Editor assigned: 02-Jan-2022, PreQC No. JMIDS-21- 9945(PQ); Reviewed: 15-Jan-2022, QC No. JMIDS-21- 9945; Revised: 23-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. JMIDS-21- 9945(R); Published: 30-Jan-2022