Research Article: 2020 Vol: 24 Issue: 3

Critical Socio-Cultural Factors Affecting Performance of Women in Leadership Positions in Quasi-Government Organizations in Zimbabwe

Joshua Tapiwa Mauchi, Durban University of Technology

Lawrence Mpele Lekhanya, Durban University of Technology

Nirmala Dorasamy, Durban University of Technology

Abstract

Some culturally constructed barriers exist that contribute to preventing women from climbing the organizational ladder, with specific socio-cultural factors that give rise to a leadership gap between women and men. This defines the study purpose, which was to examine the socio-cultural factors that impact women”s performance in management/leadership positions in state owned enterprises, generally referred to as “quasi government organizations” in Zimbabwe. The study resulted from the fact of female under-representation in management/leadership of “quasi-government” organizations such as the education departments, health departments, parastatals and local authorities, where there are fewer women than men, in terms of employment. In order to achieve the main purpose of the study, a mixed method research was used to collect primary data, in conjunction with a concurrent triangulation design, while the measurement instrument for data collection consisted of a questionnaire and interviews. The sample chosen comprised a size of 302 participants, achieved by means of stratified random and purposive sampling. Both quantitative and qualitative data analysis were employed in order to reflect on the study findings. Quantitative data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and SPSS version 25.0 and the analysis of qualitative data used thematic analysis. The study findings show women in “quasi-government” organizations are influenced by socio-cultural factors, with a positive correlation between family life, education, religion, and societal values, as well as cultural values, male attitudes, balancing work & family roles, and women”s performance. Furthermore, the analysis of data evidenced that the performance of women in “quasi-government” organizations in leadership roles in Zimbabwe is partly due to some culturally constructed barriers that prevent women from reaching management levels higher up on the organizational ladder. These barriers include cultural beliefs, values and attitudes of men towards women, in addition to religion and balancing work and family life. Overall, the study concludes there is a leadership gap between women and men in “quasi-government” organizations in Zimbabwe, even as society and cultural values discourage women to occupy top management/leadership positions, regardless of their qualifications and leadership qualities

Keywords

Women Performance, Women Leadership, Social Factors.

Introduction

Statistically, positions occupied by women in management and leadership remain low, in spite of an appeal to improve gender balance at workplaces at all levels (Andreeva & Bertaud, 2013; E-theses, 2016; Hora, 2014; Maseko, 2013). For instance, globally, women occupy only 25% of senior management positions (Yliopisto, 2014), despite making up the majority of the workforce of most organizations. This is an indication that gender inequality persists in management and leadership positions worldwide (Broughton & Miller, 2009; Mcelhaney and Smith, 2017). Thus, it is generally accepted that women occupy less management and leadership positions in nearly all spheres of employment and “quasi-government” organizations (QGO) are no exception to this widely held perspective (Kosar & Jamie, 2013; Mead & Warren, 2016; Park, 2011).

Female under-representation in management/leadership is observed in QGO such as parastatals, local authorities, education and health departments, where women’s apportionment in these positions is less than that of men (Mead & Warren, 2016). Several instances of difficulties in accessing top management/leadership positions are evident for women in these institutions. A limited number of women in the top management/leadership of QGO is illustrated by an average of 30% and 20% at middle level and senior management, respectively (Park, 2011). For instance, women constitute only 25% (14/54) of African ministers of health and 24% (12/50) of directors of global health centers (Maseko, 2013). In addition, women accounted for a mere 16.6% of board members (Globally) of large publicly listed companies. In countries such as South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria and Uganda, only 14% of executive managers are women and only 7.1% are directors and general managers of institutions (Lunyolo et al., 2014). Hence, further inquiry is required to highlight and improve this phenomenon.

Advocates of greater representation by women in management/leadership usually rely on two lines of argument: justice and the business case for diversity (Pletzer, Nikolova, Kedzior, and Voelpel, 2015). The former argues women should be considered for leadership positions for equality reasons, with justice being the pivoted tenet for promoting an egalitarian society where all human beings have equal opportunities (Fairhurst & Grant, 2010). This is to say that women should have the same opportunities as men for top management/leadership positions. Failure to provide equal opportunities is tantamount to perpetrating an injustice against women.

In contrast, the business case for diversity holds that should a board comprise heterogeneous directors, diversity would leverage financial growth and success (Patel, 2013; Pletzer et al., 2015), indicating that a higher proportion of females could be related to better firm performance. One assumption behind the statement is that women’s skills in the workplace are complementary to that of men’s. Thus, having a better balance of women in top management and leadership positions can mean a more diverse team of leaders with different perspectives and a greater ability to contribute new ideas (Boatman et al., 2011).

Research from various countries suggests organizations with a higher representation of women at the most senior levels delivers stronger organizational and financial performance, as well as better corporate governance (Bullough, 2008; Government of The Gambia, 2010; Le, 2011; Lunyolo et al., 2014; Maseko, 2013). Mounting evidence exists that the involvement of women at higher levels of management improves the way leadership and decision-making is practiced (Billsberry, 2009; Fairhurst & Grant, 2010; Neil & Domingo, 2015; Qian, 2016). Indeed, the under-utilization of the skills of highly qualified and experienced women constitutes a loss of economic growth potential (Maseko, 2013). Moreover, the lack of women in management and leadership positions means female capacity is being underutilized, human capital wasted and the quality of appointments to top positions may be compromised (Andreeva and Bertaud, 2013).

Leadership in every institution or organization has an overarching impact, since leaders decisions affect many facets of the institution or organization (Patel, 2013), however, in many leadership contexts, especially at the top, women are not adequately represented. Societies have negative prejudices with regards to women’s leadership abilities (Maseko, 2013). Even the minority of women that manage to move through to take up top management and leadership positions face some challenges that restrict their performance in these positions. This is a serious concern, as it promotes stereotypes of a women’s ability to perform at the top level of public life and results in the disempowerment of women (Maseko, 2013). As a consequence, women are mostly concentrated at the lower levels of the organizational structure, disproportionately forming a minority in management or leadership positions.

Research Problem Statement

According to Moir (2009), leadership is one of the topics that has been highly dissected and discussed; mostly demonstrated by the role of women in leadership positions having been the focus of much debate in the last two decades (Pflanz et al., 2011). These discussions are due to the fact that women continue to lag behind men in being employed in management/leadership positions. Hence, inherent gender inequalities persist in domains such as management/leadership representation.

Mitchell & Eddy (2015) point out that the rate of women professionals who move into senior management positions decreases as one goes up the ladder, with the management/leadership gap prevalent at middle and senior-level positions. However, given the almost equal percentage of men and women in low to middle management/leadership positions, one would expect to have seen a stable rise of women to senior management positions in the past decades (Pande & Ford, 2011). Nevertheless, entry of women to top positions has been slow and the proportion of women promoted to executive management positions has remained low (Broughton & Miller, 2009).

Even when they are highly qualified and in spite of the mainstreaming of more women into public life in the last 20 years (1995-2015), women remain less visible in top management/leadership positions. Notably, more women are becoming educated and hold more jobs worldwide than ever before (Andreeva & Bertaud, 2013). Thus, women have less access to top management/leadership positions, irrespective of their qualifications for those positions and they continue to lag behind men in top positions; women are particularly outnumbered by men in management and leadership positions (Andreeva & Bertaud, 2013). The management and leadership norm in QGO of Zimbabwe continues to be male-dominated, which has led to gender stereotypes where the performance of female managers/leaders is concerned. Furthermore, traditional perceptions of women as inferior to men also continue to prevail in QGO, as many people choose to preserve social injustice and African culture in justifying the subordination of women. It is apparent that socio-cultural factors determine who should be in management and leadership positions, both literally and symbolically (Mbepera, 2015); hence, blocking women from attaining high-level positions.

Research Objectives

To examine the socio-cultural factors that influence women’s performance in management/leadership positions in Zimbabwe’s QGO;

Hypotheses

In order to determine the significance of this study through hypotheses testing, each of the following variables was tested in order to determine the relationship between its relevant constructs and the performance of women in business leadership. This section presents the null hypothesis (Ho) and alternative hypothesis (Ha).

Ho 1.1: There is a relationship between women’s characteristics and performance of women in leadership positions;

Ha 1.1: There is no relationship between women’s characteristics and performance of women in leadership positions;

Ho 1.2: There is a relationship between family life factors and performance of women in leadership positions;

Ha 1.2: There is no relationship between family life factors and performance of women in leadership positions;

Ho 1.3: There is a relationship between educational factors and performance of women in leadership positions;

Ha 1.3: There is no relationship between educational factors and performance of women in leadership positions;

Ho 1.4: There is a relationship between religious factors and performance of women in leadership positions;

Ha 1.4: There is a no relationship between religious factors and performance of women in leadership positions;

Ho 1.5 There is a relationship between societal values and performance of women in management/leadership positions;

Ha 1.5 There is no relationship between societal values and performance of women in management/leadership positions;

Literature Review For The Study

The Impact of Culture on Women Leadership

Culture has no acceptable and applicable definition in all contexts, due to existing definitions always being formulated by scholars from different disciplines (Galy-badenas and Galy-badenas, 2015; Le, 2011; Moalosi, 2007). For example, Hofstede (2011) defines culture as the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one human group from those of another. According to Hofstede, culture represents a system of collectively held values, which implies that the norms and values that define the practice of a certain group should be well recognized. Therefore, culture is stated as the characteristics and knowledge of a particular group of people, encompassing language, religion, cuisine, and social habits, as well as music and arts.

Furthermore, culture is defined as all material objects made by man, ranging from stone implements to atomic energy and all non-material things thought out and institutionalized by man, ranging from values, norms, to ideas such as marriage, economy, politics, and religion, in addition to music, drama, dance and language (Le, 2011). However, cultures vary widely with regards to the roles assigned to the different genders and the norms and values that define culture are shared and learnt. Hence, culture in this study is defined as:

“The shared motives, values, identities, and interpretations of meanings of important events which are a product of universal practices transmitted unconsciously across generations”.

Reus-Smit (2013) asserts that cultures are region, colonizer and language based, for example; Western culture that is influenced by the European immigration, Eastern culture that is influenced by Asian religion, Latin culture that is influenced by Spanish and Portuguese languages, and Middle Eastern culture that is influenced by Asian religion, (Duncombe & Reus-Smit, 2019).

Some researchers are of the view that who we are is determined by society, thus the systematic oppression of women can be attributed to the culture of society (Andreeva & Bertaud, 2013; Corner, 1997; Schmidt & Moller, 2013). Mcelhaney and Smith (2017) argue that no one is born as a man or a woman but rather, people imitate and perform gendered roles, appearance and behaviors, which are a product of our culture. It has been affirmed that both gender and sex are culturally constructed and imposed on successive generations, and that gender is a sort of social ritual performed variously within diverse cultural contexts (Le, 2011). The standards created by many cultures proclaim that a perfect woman is required to be in a heterosexual and maternal frame. Furthermore, in most cultures, women are expected to exhibit certain masculine characteristics in order to be accepted in a male dominated field (Andreeva & Bertaud, 2013). Thus, societies assign roles and occupations which then become stereotypes within the society.

Linked to psychological tradition is the culturally biased perspective. A role theoretic approach within this perspective suggests that men and women behave according to certain well-defined cultural and psychological processes. Epstein (2005) states that almost everyone, including women, are to blame for the pervasiveness of patriarchal values in most societies that are still relevant today. In many cases, both men and women have internalized gender roles and propagate what is expected behavior, attitudes and aspirations of men and women.

Alternatively, the women who make it to management/leadership positions outside the perceived feminine roles may be accepted as unique and exceptional, unrepresentative of women in general. In these cases, as long as the women remain exceptions rather than the norm, they are not regarded as threats and are tolerated and often accepted into the patriarchal establishment. Smulders (2008) asserts that the culture-centered perspective argues that gender based social roles, irrelevant to the workplace, are carried into the workplace.

It has been observed that institutions and organizational structures often reproduce gender differences via internal structures and everyday practices because of cultural perceptions that determine the attitudes and behaviors of individual men and women and form barriers to women’s equal participation in management/leadership positions, specifically at senior levels (Andreeva & Bertaud, 2013; Broughton and Miller, 2009; Schmidt and Møller, 2013). Thus, cultural norms and values ensure women play a secondary role to men. For example, despite the fact that more women have entered fields formerly dominated by men, sexist patterns of hiring and promotion remain.

The Impact of Family Life on Women Leadership

According to Medina-Garrido et al. (2019), generally family life has a positive impact on performance. In a study by Erdogen et al. (2019) the aforementioned assertion is contradicted and the notion that work family conflict amongst women is put forward as due to the overlapping of professional engagements. Kan & Kyons (2019) contend there is an insignificant association of family life and performance of women. Bae & Skaggs (2019) suggest that gender diversity has considerable influence over the performance of women at the workplace and that family friendly policies are positively related to the output of an organization.

Elejalde-Ruiz (2015) emphasizes that women bear most of the burden of child caring and household chores, which keep them awake till late, whilst their male counterparts will be resting and garnering energy for the following day. Furthermore, women are said to leave work early to attend to family demands. Women who choose careers over family or want to be leaders and still have a family, are often labelled as greedy or even strange by society. Bernstein (2015) emphasizes that many women sacrifice their careers to take care of their families; for example, whenever there is a sick family member or the husband has changed employment, it is only the woman’s profession that is compromised. Furthermore, women are associated with the private and domestic domain of the home, whereas the public sphere of work is perceived to be administered by men (Klaile 2013).

The Impact of Education on Women Leadership

The term educational level refers to the academic credentials or degrees an individual has achieved. Although the educational level is a continuous variable it is frequently measured categorically in research. Mounting research evidence verifies that additional years of schooling yield additional earnings (Mincer 1974; Thomas & Fieldman, 2009). Walsh & Osipow (1983; White et al., 1997) stated that educational level is one of the most powerful predictors of career achievement in both men and women. Furthermore, Quinone et al. (1995) showed that educational level was positively related to job performance.

On the one hand, education also promotes core task performance by providing individuals with more declarative and procedural knowledge with which they can complete their tasks successfully. On the other hand, education is regarded as a key success factor for women empowerment, prosperity and development. The data on top performers, also referred to as high fliers, support the contention that a high level of education is a prerequisite for outstanding career success (Cox and Cooper, 1988). Contrary to earlier submission, White et al. (1997) points out that high flier studies have shown that, in the past, higher education has not been necessary for success in industry. The converse may be true, in that qualifications alone do not provide an automatic ticket to a successful career.

While the majority of successful women attended grammar schools, it is not clear whether this is a reflection of high ability or of their social class. In addition, it is generally acknowledged that younger women were more likely to have a comprehensive education, which is perhaps likely to be a future pattern. It was further found that some successful women leaders attended single sex schools and that successful women achieved a high level of education as a group. Another finding reveals that 50% of successful women held degrees, compared to only 6% of women in general (Duehr & Bono 2006.). Further to this, the majority of successful women were found to have specialized in traditionally female domains, indicating their anticipation of the subsequent gender segregation of the labor market. However only 50% chose their further education with a career in mind and the tendency was to pursue occupational, rather than organizational qualifications. This is particularly well-suited to the current economic climate, when a continuous career within the same organization cannot be guaranteed.

The Impact of Religion on Women Leadership

Onudugo & Onudugo (2015) view religion as a set of common beliefs and practices generally held by a group of people, often codified as prayer, ritual and religious law. Religion also encompasses ancestral or cultural traditions, writings, history, and mythology, as well as personal faith and mystic experiences. Often described as a communal system for the coherence of belief, religion focuses on a system of thought, unseen being, person, or object considered to be supernatural, sacred, divine, or of the highest truth (Fairhurst & Grant, 2010). Moral codes, practices, values, and institutions, as well as traditions, rituals, and scriptures are often associated with core beliefs, and these may have some overlap with concepts in secular philosophy.

As an element of culture, religion has a stake in gender beliefs, inequality and role segregation in many societies. According to Hofstede et al. (2010), human beings have the need to be associated with supernatural forces believed to have control over their destiny. All religions assign separate and specific religious roles to men and women. Moreover, most religions believe that God, the Father, is a man, thus, on the one hand, He created men in His own image and likeness. On the other hand, a woman is believed to have been created from a man for assistance. Hence, some churches, for instance the Anglican Church, is yet to promote women to the positions of Deacon, Reverend, Arch-Deacon and Bishops. Apart from this, the church also recognizes gender roles. For example, the reading of the Gospel is done by the male Sub Deacon; no female Sub Deacon is allowed to read the Gospel. However, the Pentecostal churches recognize that all people are equal before God; hence no leadership positions in the church are reserved for men only.

In masculine societies people believe more in establishing good relations with God. However, feminine societies prioritize good relationship with fellow human beings, disregarding the dominance of one gender over the other. In some religious denominations, the sexual pleasure of women is regarded as abominable, while that of men is seen as acceptable. These inequalities among most religions negatively affect the image and status of women and also transcend to their opportunity to occupy certain positions in society. In a study in rural western Kenya et al. (2016) established that religion and ethnicity have an impact on women’s performance.

Social Values and Norms

According to Lahti, 2013, Society sets standards, expectations and customs for organizations and individuals that subsequently affect female leadership. While social factors shape who we are as people, it also affects how we behave and what we buy. Societal factors are the most difficult and time-consuming factors to alter, as they have an effect on various dimensions of life and cannot be easily controlled. Furthermore, these factors affect lifestyles within the social environment, such as religion, family or wealth (Lucas, 2015; Pletzer et al., 2015) and these factors change as time lapses and progresses. Shin & Bang (2013) allege social factors impede women from advancing into leadership positions.

The ecological model advances the notion that social factors can be categorized into levels such as societal, organizational and individual levels (Shin & Bang, 2013). According to Metz (2009), societal level factors include legislation and policy; and societal norms driven by media. The organizational level includes factors such as higher performance standards and risky tasks, bad human resource practices, conflict between work and family; and the perceptions of work-family conflict. Individual level factors comprise the sense of self, diminished self-efficacy and communication style, along with facts and experiences that influence an individual’s personality and attitudes.

A significant social feature resides in the dual if not triple responsibilities of women (Moir, 2009), with these responsibilities consisting of marriage, family care and work. In most countries, the primary role of women is to marry and become a mother. However, the community of the 21st century also recognizes that women need to seek employment, thus reflecting the impact of social values and norms on women’s leadership.

Zinyemba & Machingambi (2014) allege that 50% of the Zimbabwean population practices what is called the “Syncretic” religion, which is part Christian and part indigenous beliefs. Furthermore, while 25% of the population identify as Christians, another 24% practice indigenous beliefs, with the remaining 1% made up of Islam and other religions (Africaw Group 2012).

The Zimbabwean people believe in the existence and role of ancestral spirits in one’s life and that the spirit continues to live on when a person dies, allowing the spirit’s ability to influence events in the community (Gelfand, 1959). When an adult person dies their spirit is believed to wander about as it is considered homeless until the relatives of the deceased person welcome the spirit back through a process known as “kurova guva”, which is performed a year after death. Once that is done, the spirit becomes legitimate and is recognized as a family spirit (Zambuko 2014).

In addition, Zinyemba & Machingambi (2014) alludes a totem to socially identify a clan with a certain symbol, usually an animal or bird and all clans are identified with a totem, with the totem serving the clan, preventing it from being defiled through incestuous behavior. It is further affirmed by Zinyemba & Machingambi (2014) that people of the same clan share the same totem and for all intents and purposes, people who share the same totem are considered to be closely related. As they are assumed to be relatives, it is deemed that they should not marry each other. Furthermore, the totem is an extension of this extended family.

With older people in the traditional Zimbabwean culture generally perceived to be mature, to have more experience, to be exemplary, wiser and more dedicated, leadership roles are theirs to occupy. Due to age and seniority being respected in Zimbabwean culture, respect for the elderly is upheld. One sign of showing respect for the elders is found when talking to elders and a person should not look directly at any elder, especially when the younger person is a woman or daughter-in-law, otherwise it is seen as a sign of disrespect.

The traditional form of family is the extended family structure, which is the opposite of the western nuclear family. The clan is also built upon extended family relationships, with the extended family relationship based on the precepts of communalism, as opposed to individualistic practices. This precept requires everyone to accept the responsibility for caring for others beyond immediate family needs. As a patriarchal society, the Zimbabwean culture generally regards women as being subordinate to men, although the situation is changing (Tatira 2010). Such values and norms disadvantage women leaders or managers as they execute their mandates. Women managers find it difficult to assign assignments to older male subordinates and even elderly women, who are regarded as mothers. Another difficulty is encountered when a male figure is expected to clear plates or tea cups after a board meeting, as this is not regarded as culturally correct.

Quasi-Governmental Organizations and Women Leadership

QGO are organizations that have both public and private characteristics, not fitting neatly into either category (Kosar & Jamie, 2013). One type of QGO is an organization incorporated as a private, non-profit organization, which is nonetheless managed by a board of directors composed of government officials or directors appointed by a unit of traditional government. Defined by Mead and Warren (2016) as an organization that has some, but not all, of the defining characteristics of a government, some QGO are financially dependent on the government. Examples include hospitals, certain electricity grid exchanges and operators, government department and schools. Other quasi-governmental entities finance their activities either through charitable donations or by engaging in commercial activities (Park, 2011); these include local authorities (municipalities).

Research Methodology Used

Factor analysis was done on the Likert scale items and the socio-cultural factors were divided into finer components, as explained below in the rotated component matrix (Table 1).

| Table 1: Kmo And Bartlett's Test | ||||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. | Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approx. Chi-Square | Df | Sig. | ||

| Family life | 0.711 | 345.892 | 10 | 0 |

| Education | 0.57 | 205.585 | 10 | 0 |

| Religion | 0.676 | 345.997 | 3 | 0 |

| Societal Values | 0.603 | 88.146 | 6 | 0 |

All of the conditions were satisfied for factor analysis. In other words, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy value should be greater than 0.500 and the Bartlett's Test of Sphericity sig. value should be less than 0.05. It must further be noted that both the KMO Measure and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity sig of subthemes for this study were found to be within the required ranges. The values of each subtheme exceeds the threshold value and the sig value of 0.000, respectively. This indicated that the sampling under each subtheme was statistically significant in measuring the same thing. In this study, family life has a 0.711 KMO measure of sampling adequacy. This implied the subtheme and its component variable collectively have a positive impact on women’s leadership. Further, religion has a KMO measure of 0.676, denoting a strong significance of the subtheme and its component variables to the study. Social values have a KMO measure of 0.603, which is not as significant as the first two. Education is the least significant of the variables, with a KMO measure of 0.570 for women’s leadership.

This study used a mixed methods approach, which involves conducting research by combining qualitative and quantitative methods in a single study. The quantitative approach was used to collect numerical data, in order to test the associations of the variables under study. The qualitative approach was used because of its strength in collecting in-depth information based on the experiences, beliefs, feelings and behavior of women in leadership positions at QGO.

The study used a concurrent triangulation design to collect data. Both qualitative and quantitative data were collected at the same time. The target population of the study includes government institutions, local authorities and parastatals in Harare, Midlands and Mashonaland provinces. The study’s target population totals 1 400, with the sample made up of 302 respondents, comprising 55 board of directors members, 25 Chief executive officers and 197 senior managers. The study used stratified random sampling to place the population into well-defined groups. Purposive sampling was employed to select participants based on their expertise and gender. Data were collected using a structured-questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS version 25.0, while qualitative data were analyzed using Likert scaled and thematic coding.

Research Findings For The Study

Quantitative Analysis

The impact of culture on women’s leadership

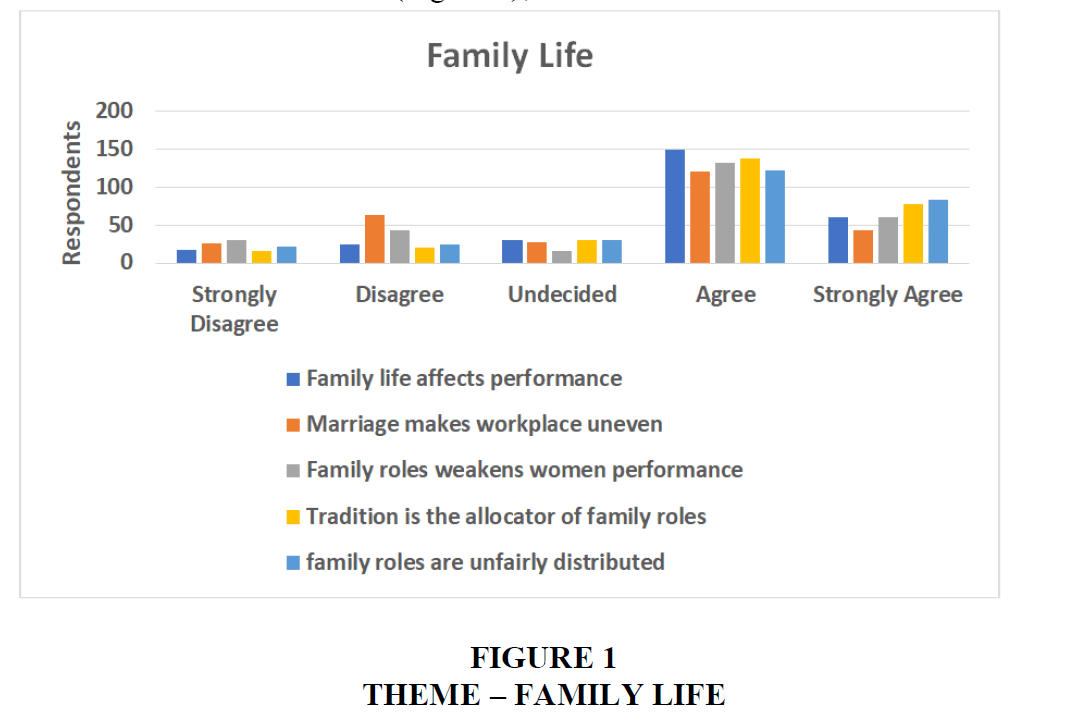

According to Medina-garrido et al. (2019), family life generally has a positive impact on performance. However, a study by Erdogen et al. (2019) contradicts the aforementioned assertion and puts the notion forward that work family conflict amongst women is due to the overlapping of professional engagements. Kan & Kyons (2019) highlighted the insignificant association between family life and the performance of women. Furthermore, Bae & Skaggs (2019) suggest that gender diversity has a considerable influence on the performance of women at the workplace and that family friendly policies are positively related to the output of organizations. All the authors’ submissions were correct, as upheld by the study findings. It was also clear from literature reviewed that family life impacted the performance of leaders in different ways. To support the validation of family life assertions, a Pearson correlation test was administered to establish the impact on women’s performance, thereby invoking the five thematic accessions as shown below (Figure 1);

“Family life affects performance of women in leadership positions” - findings are that 74.2% (agree + strongly agree) of respondents indicated that family life affects the performance of women leaders. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate that there is a positive correlation between family life and performance, and there is an insignificant association. (r=0.001, P=0.983) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results mean that the variable has an insignificant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore dismiss the hypothesis (Ho 1.2) on this variable. Thus, the result was statistically insignificant and was due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

“Marriage makes the workplace uneven for women leaders”-findings show that 58.4% (agree+strongly agree) of women leader respondents distinctly qualified the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between family life and performance, and there is an insignificant association. (r=0.109, P=0.068) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results mean this variable has an insignificant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. This therefore dismisses the hypothesis on this variable. Put differently, the result was statistically insignificant and was due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

“Family roles weaken women’s performance as a leader,”-findings from the survey are that 67.5% (agree+strongly agree) of women leaders agreed and qualified the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between family life and performance, and there is a significant association (r=0.157, P=0.008) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results indicate this variable has a significant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore accept the hypothesis (Ho 1.2) on this variable. That is to say, the results were statistically significant and this was not due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

“Tradition is the allocator of family roles,”-findings from the survey are that 76.4% (agree+strongly agree) of the women leaders agreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between family life and performance, and there is a significant association. (r= 0.205, P=0.001) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results propose this variable has a significant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore accept the hypothesis (Ho 1.2) on this variable. Simply put, the result was statistically significant and not due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

“Family roles are unfairly distributed,”-findings from the survey illustrate that 72.8% (agree + strongly agree) of the women leader respondents agreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between family life and performance, with a significant association (r= 0.131, P=0.027) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results indicate that this variable has a significant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore accept the hypothesis (Ho 1.2) on this variable. Put another way, the result was statistically significant and was not due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

Education

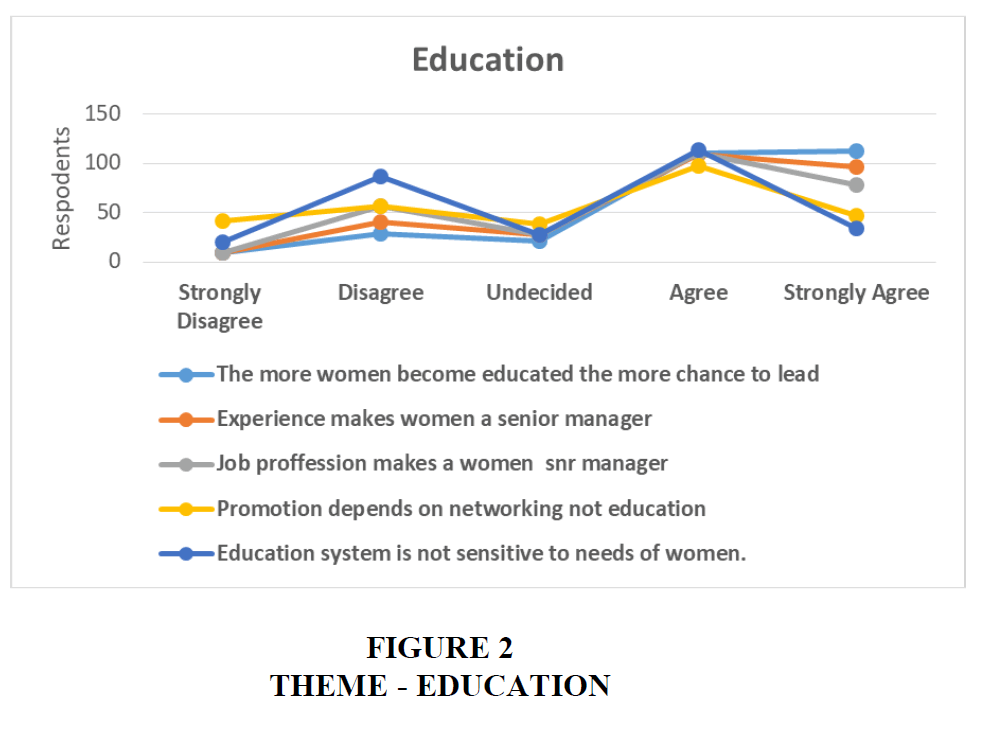

According to Mincer (1974), in Thomas & Fieldmen 2009), an investment in education results in the enhanced performance of leaders. The motion was supported by White et al. (1997), who further emphasized that any additional qualification is a predictor of achievements. Quinone et al. (1995) in Vrci? et al. (2016) suggested that education is a prerequisite of high flying performance. Some education suppositions pointed to a positive relation whilst some pointed to a negative relationship with the performance of leaders. Below is a graphic illustration (Figure 2) and findings that also confirm the accessions;

“The more women become educated the more chances of being leaders,”- findings from the survey show that 78.8% (agree + strongly agree) of women leader respondents agreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between education and performance, and there is a significant association (r= 0.172, P=0.004) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results denote that this variable has a significant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore accept the hypothesis (Ho 1.3) on this variable. In other words, the result was statistically significant and was not due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

“Experience makes women a senior manager or leader,”- findings from the survey are that 72.4% (agree + strongly agree) of women leader respondents agreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between education and performance, and there is a significant association (r= 0.278, P=0.000) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results meant this variable has a significant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore accept the hypothesis (Ho 1.3) on this variable. Put differently, the result was statistically significant and was not due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

“Job profession make a women senior manager or leader,”- findings from the survey are that 66.8% (agree + strongly agree) of women leader respondents agreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between education and performance, and there is a significant association (r= 0.266, P=0.000) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results purport that this variable has a significant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore accept the hypothesis (Ho 1.3) on this variable. Simply put, the result was statistically significant and was not due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

“Promotion depends on networking and not education,”- findings from the survey illustrate that 50.6% (agree + strongly agree) of the women leader respondents agreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between education and performance, and there is a significant association (r= 0.162, P=0.006) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results mean this variable has a significant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore accept the hypothesis (Ho 1.3) on this variable. Differently stated, the result was statistically significant and was not due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

“Education system is not sensitive to the needs of women,”- findings from the survey are that 52.3% (agree + strongly agree) of women leader respondents agreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between education and performance, and there is a significant association (r= 0.169, P=0.004) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results indicate that this variable has a significant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore accept the hypothesis (Ho 1.3) on this variable. In other words, the result was statistically significant and was not due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

Religion

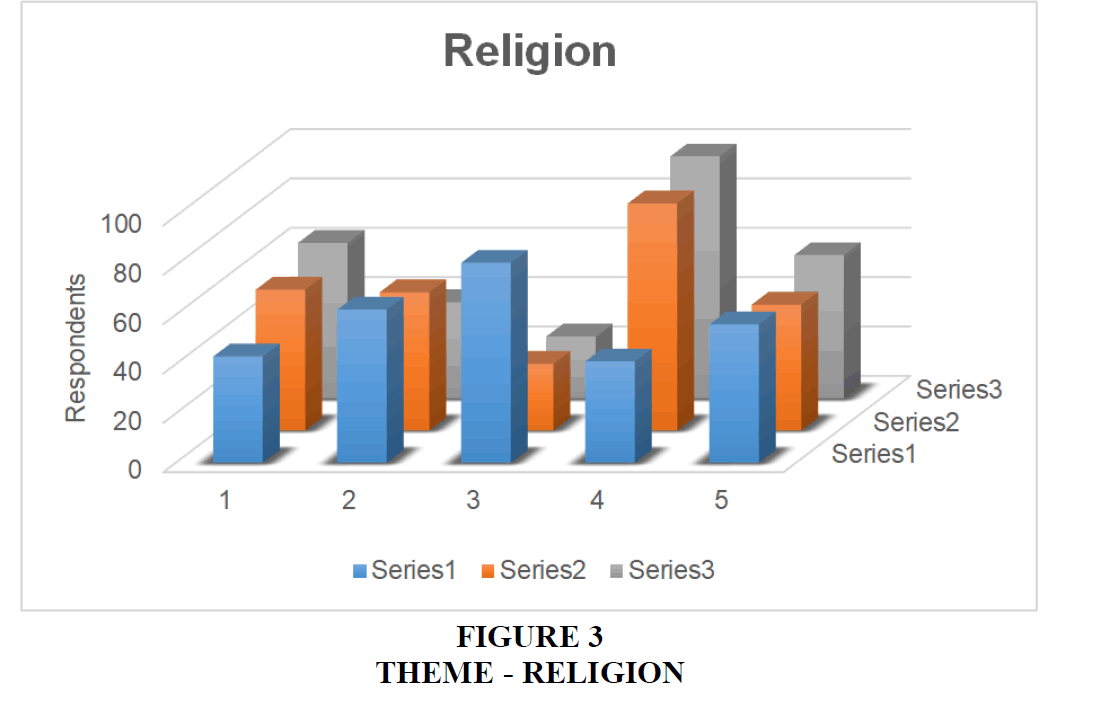

Onudugo & Onudugo (2015) proclaim that religion has control over the roles allocated to men and women. Elejalde-Ruiz (2015) points to a positive relation between religion and the performance of women. Bae & Skaggs (2019) champion the positive correlation between religion and women’s performance. The findings of the study confirm the accessions, illustrated in Figure 3 below;

“Religion is the oppressor of women,”- findings from the survey are that 48.2% (agree + strongly agree) of women leader respondents agreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate that there is a positive correlation between religion and performance, and there is a significant association (r= 0.147, P=0.013) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results demonstrate that this variable has a significant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore accept the hypothesis (Ho 1.4) on this variable. Therefore, the result was statistically significant and not due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

“Religion confines women to the home,”- findings from the survey are that 50.5% (agree + strongly agree) of women leader respondents agreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between religion and performance, and there is an insignificant association (r= 0.72, P=0.229) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results mean this variable has an insignificant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore reject the hypothesis (Ho 1.4) on this variable. In other words, the result was statistically insignificant and was due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

“Men use religion to oppress women,”- findings from the survey are that 54.8% (agree + strongly agree) of women leader respondents agreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between religion and performance, and there is an insignificant association (r= 0.50, P=0.407) at the 0.05 level of significant for this variable. These results mean this variable has an insignificant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore set aside the hypothesis (Ho 1.4) on this variable. The result was thus statistically insignificant and was due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

Societal Values

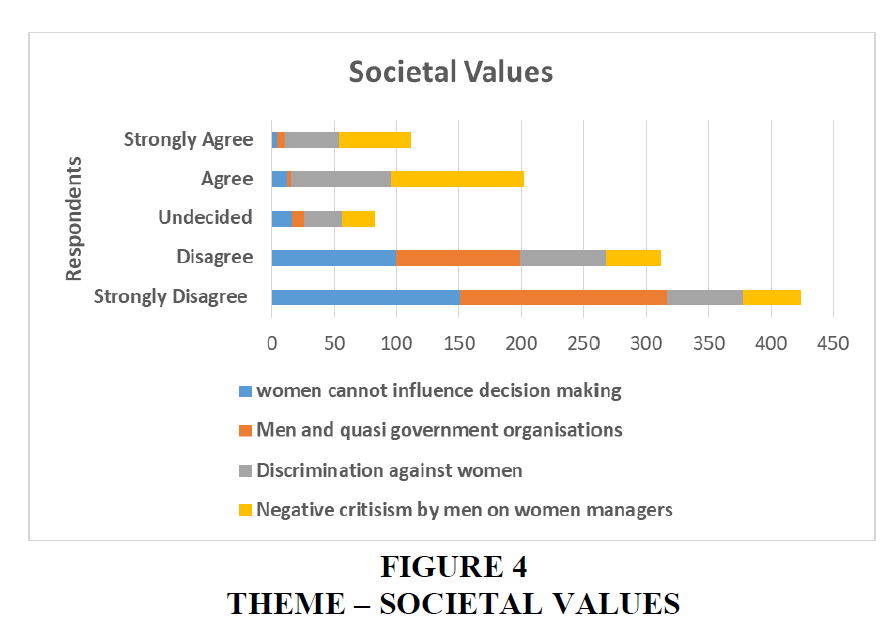

Zinyemba & Machingambi (2014) state that values apportioned to the dead and their influence have a bearing on the errands of the living and daily occurrences and are prescribed societal values. Africanism revolves around clans and totems that create the fibers of family, dictating what constitutes incestuous behavior and ties that influence where one can work and what people may or may not aspire to (Zambuko 2014). Tatira (2010) affirms the bias community has over women leadership; women actually find it difficult to assign work to culturally and societally rooted men or elderly women. The suppositions that were put forward are confirmed by the findings in this study and are shown in Figure 4 below;

“Women cannot influence decision making,”- findings from the survey are that 88.7% (disagree + strongly disagree) of women respondents disagreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between societal values and performance, and there is a significant association (r= 0.136, P=0.022) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results reveal that this variable has a significant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore accept the hypothesis (Ho 1.5) on this variable. Simply stated, the result was statistically significant and not due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

“Men and Quasi-government organizational management,”- findings from the survey show that 93.3% (disagree + strongly disagree) of women leader respondents disagreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between societal values and performance, and there is a significant association (r= 0.24, P=0.036) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results infer that this variable has a significant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore agreed with the hypothesis (Ho 1.5) on this variable. This means the result was statistically significant and not due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

“Discrimination against women,”- findings from the survey are that 45.6% (disagree + strongly disagree) of women leader respondents disagreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between societal values and performance, and there is a significant association (r= 0.24, P=0.036) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results mean this variable has a significant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore accepted the hypothesis (Ho 1.5) on this variable. Stated differently, the result was thus statistically significant. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

“Negative criticism by men on women management,” -findings from the survey indicate that 58.3% (agree + strongly agree) women leader respondents agreed with the assertion. The results of the Pearson correlation test indicate a positive correlation between societal values and performance, and there is a significant association (r= 0.132, P=0.026) at the 0.05 level of significance for this variable. These results show this variable has a significant impact on the performance of women in leadership/management positions in QGO. The researchers therefore agreed with the hypothesis (Ho 1.5) on this variable. Simply put, the result was statistically significant and was not due to chance. The statistical analysis for this variable is presented in the Appendix.

Qualitative Analysis

Cultural factors affecting women performance in leadership positions

This objective was aimed at examining cultural factors that affect the performance of women in management/leadership position in a QGO. In order to achieve this objective, women were asked to state those cultural factors that affect their performance in management/leadership positions. Cultural factors found to affect women in leadership positions have been grouped as indigenous and organizational culture.

Indigenous Culture

Cultural beliefs

The participants indicated the existence of cultural beliefs that generally undermine women and therefore influence people to not recognize them as capable of leading. According to cultural beliefs, women are not expected to take leadership roles. The participants had the following to say:

“The society has an opposing view on us women taking leadership positions, especially going to the top. And you know … if you perform anything that the society believe to be men?s role … You will be labeled all sorts of things”.

“…it?s a bit tricky to be a leader when you are a woman, men do not take our decisions and orders serious due to some cultural beliefs”.

“There is a belief that women are made to produce children and to do kitchen work”.

“The notion and belief that women are inferior to men also add to the gender gap in top management”.

" Females are believed to be sorely there for marriage. In local authorities, women are expected to be subordinate to their male counterparts”.

Cultural values

This study determined cultural values held by society towards women. Women who participated in this study indicated some significant values emanating from cultural perspectives held by society, which have negatively impacted their performance. The participants had the following to say:

“As women we are seen to be only good as home keepers and men as leaders, so that is an obstacle to us on its own”.

“Most societies expect women to bear children and look after them at home”.

“The societies that we come from attach less value on women leadership. They don?t even support women leaders, unless women can prove that they are good leaders.”

“In my opinion, it is because of our cultural values. According to cultural values women are seen to be second to men”.

From the responses provided above, men are said to attach less value to the leadership of women. As a consequence, men rarely recognize female leadership.

Male attitudes

Men have negative and hostile attitudes towards women participating in leadership positions. Generally, men are of the opinion that they cannot be led by a female in an organization. According to the participants, it was a foregone matter that men are always looking down on women as incapable leaders. The participants had the following to say:

“Women may be discouraged to take up leadership roles by their husbands”.

“Most men believe they cannot be led by women; they claim that only men should be the leaders while women follow.

“Men do not want to be led by women at work and in the society they tend to underestimate the value of women in leadership positions”.

"when we want people to be leaders we seek to pick men before considering women. That has been the norm, and that has contributed greatly to the underrepresentation of women in leadership”.

According to the responses presented above, the attitudes of men towards women leadership are pessimistic and unreceptive. Thus, men do not have positive attitudes towards women leadership.

Religious beliefs

The majority of major world religions, including institutionalized Christianity, deprecate women to some degree. Since the first century, organized Christianity has interpreted the Bible as prescribing a gender-based hierarchy. The hierarchical theology has placed a woman under the man's authority; in the church of God, in marriage, and in other places, such as the work environment. Historically, religious beliefs have barred women from church leadership positions that afford them (women) any kind of authority over men. During the interviews, the participants had the following to say:

“Men have continued to hold on to the Bible scriptures that discourage women to occupy positions of influence whether in church or in any environment where men are present”.

“Biblically, women have been seen as being created solely to help men rather than to lead them….this perception also becomes a problem when it comes to the notion of leadership”.

In summary, religious beliefs posit that men are natural leaders created by God and women are supposed to abide by the authority of men. Thus, religiously, women should not lead men; hence, putting women in leadership positions is viewed as contradictory to God’s will.

Balancing work and family

Balancing work and family responsibilities is one of the most challenging obstacles for women who seek leadership positions. The findings revealed the biggest difficulty for most women in leadership positions was that of balancing work and family. During the interviews, women had the following to say:

“As a woman leader, the biggest disadvantage is the dual roles of family and work. I am expected to perform my duties as a mother and wife while at the same time work requires me to be present as a manager... it?s really a dilemma to women leaders”.

“Women leaders are restricted by family and work demands ...I think you can also feel it, but I don?t know how to explain. As women, it?s very cumbersome to be a leader and family member”.

Traditionally, women have to manage nearly everything in the home. Doing the housework, bringing up the children … all my responsibilities whilst I also have to do my job well. Obviously, it?s very hard work for me.

According to the responses provided above, women leaders are having a difficult time in trying to balance work and family responsibilities. As a consequence, they are found trapped between these roles (to choose between being a successful leader or a successful mother). It is significant to note that Yliopisto (2014) also raises a related point, with regards to the manner in which leadership is viewed and valued by men being dependent on societal culture. Most cultural values and beliefs prevent women from developing an interest in leadership positions and accepting them (Galy-badenas & Galy-badenas, 2015). Numerous points have been raised by previous researchers regarding culture as a barrier to the performance of women in leadership positions. Culture is seen to exclude women from leadership positions (Hofstede, 2011).

Generally, culture undermines women and therefore people do not recognize women as capable of leading. The lack of acceptance of women in leadership roles is attributed to the fact that society somehow sees it as women assuming men’s positions. This is a typical example of a highly masculine culture where deviation from a specific job assigned to a particular gender is seriously resisted by the larger society (Tirmizi, 2008). Culture resides at multiple levels, from civilizations, nations, and organizations to groups. It has been considered by many scholars as the driving force behind all the other factors that makes leadership relatively inaccessible and unattractive to women, especially at higher levels (Maseko, 2013; Weber, 2015).

Conclusion

Based on the research findings, the researchers conclude that women leaders’ performance is correlated both positively and negatively to family life and societal values, as the varied suppositions impact differently due to hybrid factors that may blend with these factors. Education and religion correlate positively, thereby confirming accessions forwarded to be true. The findings further show cultural beliefs exist that generally undermine women and therefore, people do not recognize women as capable of leading. According to cultural beliefs in Zimbabwe, women are not expected to take leadership roles. This study also established the existence of cultural values held towards women by society. Women who participated in this study indicated some significant values held by society that emanate from cultural perspectives, which have negatively impacted women’s performance. According to the findings, men place less value on the leadership of women and consequently, men rarely recognize female leadership.

Furthermore, men harbor negative and hostile attitudes towards women participating in leadership positions. Generally, men feel they cannot be led by a female in an organization. According to the participants, men are perceived to always look down on women, seeing them as incapable leaders. The attitudes of men towards women leadership are pessimistic and unreceptive, indicating that men do not have positive attitudes towards women leadership. The study corroborated the findings from the related literature.

Recommendations

1. There is a need to strengthen and upgrade the mechanisms for monitoring equality in employment.

2. It is necessary to create a more favorable work environment that fosters gender equality and the career advancement of women.

3. There is a need to combat gender-based job segregation, increase information and awareness and education on leadership opportunities.

4. A need exists to improve the retention of women staff, along with communication and awareness of the importance of gender balance in management/leadership positions.

5. There should be a policy shift towards the promotion of gender balance and the improvement of the proportion of women in management.

Recommendations And Furhter Research

The study recommends that the findings presented in this study can be strengthened by using a larger sample of the population. The study also recommends that research instruments, such as a focus group discussion and experimental design should be used to reinforce qualitative and quantitative data, respectively. Focus group discussions can be conducted with experts in leadership and management in order to gain an in-depth understanding of the factors affecting the performance of women in leadership positions. It is also recommended that future research may investigate the individual factors that could affect women in management/leadership positions in Zimbabwe.

References

- Africaw Group. (2012). Major problems facing ghana today. AFRICAW: Africa and the World. 2006-2012. 9 Apr. 2012.

- Andreeva, M., & Bertaud, N. (2013). Women and men in leadership positions in the European Union, 2013. Publications Office European Commission.

- Bae, K., & Skaggs, S. (2019). The impact of gender diversity on performance: The moderating role of industry, alliance network, and family-friendly policies – Evidence from Korea. Journal of Management & Organization, 25(6), 896-913.

- Bakibinga, P., Mutombo, N., Mukiira, C. (2016). The Influence of Religion and Ethnicity on Family Planning Approval: A Case for Women in Rural Western Kenya. J Relig Health, 55, 192-205.

- Bernstein, M., Russakovsky, O., Deng, J., Su, H., Krause, J., Satheesh, S., Ma, S., Huang, Z., Karpathy, A., Khosla, A., & Berg, A.C. (2015). Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge.International journal of computer vision,115(3), 211-252.

- Billsberry, J. 2009. The Social Construction of Leadership Education. Journal of Leadership Education, 8(2), 1–9.

- Boatman, J., Wellins, R., Selkovits, A., Talent, T., & Expert, M. (2011). Revolutionize leadership, your business. Leadership. Global Leadership Forecast, DDI

- Broughton, A., & Miller, L. (2009). Encouraging Women into Senior Management Positions: How Coaching Can Help An international comparative review and research. The Institute for Employment Studies, 129. Available at: http://www.employment?studies.co.uk

- Bullough, A.M. (2008). Global Factors Affecting Women’s Participation in Leadership, 386. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/001088048102200214

- Corner, J.L., Kock, N.F., & McQueen, R.J. (1997). The nature of data, information and knowledge exchanges in business processes: implications for process improvement and organizational learning.The Learning Organization, MCB UP Ltd.

- Duehr, E.E., & Bono, J.E. (2006). Men, women, and managers: are stereotypes finally changing?Personnel psychology,59(4), 815-846.

- Duncombe, C., & Reus-Smit, C. (2019). Culture, Diversity and Technology. InTechnologies of International Relations(pp. 69-76). Palgrave Pivot, Cham.

- Erdogen, B. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of justice perceptions in performance appraisal.Human Resource Management Review,12, pp.555-578.

- E-theses, Lari, N. (2016).Gender And Equality In The Workplace–A Study Of Qatari Women In Leadership Positions(Doctoral dissertation, Durham University). Durham e-Thesis.

- Elejaldez-Ruiz, A. (2015). C-suite barrier: fewer women than men actually reach for it, Chicago Tribune, 2 October.

- Epstein, G.A. ed., 2005.Financialization and the world economy. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Fairhurst, G.T. & Grant, D. (2010). The social construction of leadership: A sailing guide. Management Communication Quarterly, 24(2), 171-210.

- Galy-badenas, F., & Galy-badenas, F. (2015). A Qualitative Study of Male and Female Perceptions in Differences in the Working and Domestic Sphere?: A comparison of the French and Finnish cultures, Open Science Centre, 1–88. JYX Repository

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1-26.

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. London: Sage.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. Revised and expanded 3rd Edition.N.Y.: McGraw-Hill.

- Hora, E.A. (2014). Factors that affect Women Participation in Leadership and Decision Making Position. Asian Journal of Humanity, Art and Literature, 1(2), 97.

- Klaile, Y., Schlack, K., Boegemann, M., Steinestel, J., Schrader, A.J., & Krabbe, L.M. (2016). Variant histology in bladder cancer: how it should change the management in non-muscle invasive and muscle invasive disease?.Translational andrology and urology,5(5), 692.

- Kosar, K.R.. & Jamie, P. (2013). The Quasi-Government in America, Oxford University Press.

- Lahti, E. (2013). Women and Leadership?: Factors That Influence Womens Career. Bachelor’s Thesis, Lahti University.

- Le, H., Oh, I.S., Robbins, S.B., Ilies, R., Holland, E., & Westrick, P. (2011). Too much of a good thing: Curvilinear relationships between personality traits and job performance.Journal of Applied Psychology,96(1), 113.

- Lucas W.C. (2015). An Investigation Into the Social Factors That Influence Sport Participation?: A Case of Gymnastics in the Western Cape, (November).

- Lunyolo, G., Ayodo, T., Tikoko, B., & Simatwa, E. (2014). Socio-cultural Factors that Hinder Women’s Access to Management Positions in Government Grant Aided Secondary Schools in Uganda?: The Case of Eastern Region. Educational Research, 5(7), 241-250.

- Maseko T.I. (2013). A comparative study of challenges faced by women in leadership: A case of Foskor and the Department of Labour. MComm Thesis, 137.

- Mbepera, J.G. (2015). An Exploration of the Influences of Female Under- representation in Senior Leadership Positions in Community Secondary Schools (CSSs) in Rural Tanzania. A Doctoral Submitted to the UCL Institute of Education, 1–293.

- Mcelhaney, K., & Smith G. (2017). Eliminating the Pay Gap?: An Exploration of Gender Equality, Equal Pay, and A Company that Is Leading the Way, University of California, Berkeley.

- Mead, J., & Warren, K. (2016). September. Quasi-governmental organizations at the local level: publicly-appointed directors leading nonprofit organizations. InNonprofit Policy Forum(Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 289-309). De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/npf-2014-0044

- Medina-Garrido, J.A., Biedma-Ferrer, J.M., & Ramos-Rodríguez, A.R., 2019. Moderating effects of gender and family responsibilities on the relations between work–family policies and job performance.The International Journal of Human Resource Management, pp.1-32.

- Metz, I. (2009). Organisational factors, social factors, and women's advancement. Applied Psychology. International Review, 58(2), 193-213.

- Mitchell, A.L., Finn, R.D., Coggill, P., Eberhardt, R.Y., Eddy, S.R., Mistry, J., Potter, S.C., Punta, M., Qureshi, M., Sangrador-Vegas, A., & Salazar, G.A. (2016). The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future.Nucleic acids research,44(D1), pp.D279-D285

- Moalosi, R. (2007). The Impact of Socio-cultural Factors upon Human-centred Design in Botswana, Doctoral Thesis, Queensland University of Technology.

- Moir, S., & Fauci, A.S., (2009). B cells in HIV infection and disease.Nature Reviews Immunology,9(4), pp.235-245.

- Neil, T.O., & Domingo, P. (2015). The power to decide: Women, Decision-making and Gender Equality. ODI Briefing, (September), 1–8.

- Onodugo, O., & Onodugo, D. (2015). Clinical kidney journal 9(1), 162-167, Available at: scholar.google.com/citations?user=4yIFVhcAAAAJandhl=en

- Pande, R., & Ford, D. (2011). Gender Quotas and Female Leadership?: A Review Background Paper for the World Development Report on Gender. Harvard University, 1–42. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-34357-5

- Park, S., & Cho, Y.J. (2011) June. Top Leadership and Performance of Quasi Government Organizations in Korea. Inpresentation at the 11th bi-annual Public Management Research Conference, Syracuse, NY, June(pp. 2-4).

- Patel, G. (2013). Gender Differences in Leadership Styles and the Impact within Corporate Boards, Commonwealth Secretariat.

- Pflanz. M.B.L., & Grady L.M. (2011). Women in positions of influence: Exploring the journeys of female community leaders., University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

- Pletzer, J.L., Nikolova, R., Kedzior, K.K., & Voelpel, S.C. (2015). Does gender matter? Female representation on corporate boards and firm financial performance - A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 10(6), 1–20. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130005

- Qian, M. 2016. Women’s Leadership and Corporate Performance and economics working paper series, (472).

- Qui?ones, M.A., Kevin Ford, J., & Mark S. (1995). The relationship between work experience and job performance: A conceptual and meta?analytic review.Personnel psychology, 48(4), 887-910.

- Reus-smit, C. (2013). Individual rights and the making of the International system. Cambridge University Press.

- Schmidt, T., & Møller, A. (1997). Stereotypical barriers for women in management. Pure.Au.Dk, (Im). Available at: http://pure.au.dk/portal-asb-student/files/36185535/opgave_til_?nettet?.pdf

- Shin, H.Y., & Bang, S.C. (2013). What are the top factors that prohibit women from advancing into leadership positions at the same rate as men. Cornell U.

- Smulders, M.M., Schenning, A.P., & Meijer, E.W. (2008). Insight into the mechanisms of cooperative self-assembly: The sergeants-and-soldiers principle of chiral and achiral C3-symmetrical discotic triamides.Journal of the American Chemical Society,130(2), 606-611.

- Tatira, L. (2010). The Shona Culture, The Shona People’s Culture; Lambert Academic Publishing, Deutschland.

- Tirmizi, S.H., Sequeda, J., & Miranker, D. (2008). Translating sql applications to the semantic web. InInternational Conference on Database and Expert Systems Applications(pp. 450-464). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Vrci?, M., Pavlovi?, R., Solakovi?, S., Kova?evi?, E., & Abazovi?, E. (2016). Specific training adjustments for young discus throwers as a prerequisite for achieving elite performance.SportLogia,12(1), p.70.

- Weber, S. (2015). Gender Equality in the Executive Ranks: A Paradox - The Journey to 2030. Available at: httd/www.webershandwick.com/uploads/news/files/gender-equalit.y-in-the-executive-ranks-report.pdf.

- White, B., Cox, C., Cooper, C.L. (1997). A portrait of successful women, Women in Management Review, 12(1): 27 – 34.

- Yliopisto, J. (2014). An exploration of socio-cultural and organizational factors affecting women’s access to educational leadership Master’s Thesis Department of Education Institute of Educational Leadership University of Jyväskylä.

- Zambuko. (2014). Available at: www.Zambuko.com/mbira page /resource shone_ religion.Html.

- Zinyemba, A., & Machingambi, J. (2014). The effect of shona cultural beliefs and practices on management practices in small to medium enterprises in zimbabwe, University of Zimbabwe, Faculty of Commerce, Department of Business Studies, 3(9) September 2014 Available at: http://www.garph.co.uk.