Research Article: 2017 Vol: 16 Issue: 2

Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure in Malaysian Business

Mohammed Abdullah Mamun, University Kuala Lumpur

Junaid M Shaikh, Curtin University

Rubina Easmin, East Delta University

Keywords

Corporate Social Responsibility, Disclosure, Strategic.

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has swept across the world and has become one of the buzzwords of the new millennium (Pedersen, 2006). Over the last few decades, corporate social responsibility (CSR) has received a large amount of attention in research and in practice. Evidences from empirical studies indicate that consumers are influenced by CSR initiatives by businesses, when they are aware of CSR communications. As a response to the growing awareness of and concern about social and environmental issues, an increasing number of companies are proactively publishing their CSR-related principles and activities (Kilian and Hennigs, 2014). Along with the public’s increased demand for businesses to actually operate responsibly, stakeholders want to be informed about what companies do right and what they do wrong (Kilian and Hennigs, 2014). Because, in recent times, corporations have been pressured by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), activists, communities, governments, media and other institutional forces. These groups demand what they consider to responsible corporate practices (Garriga and Mele, 2004).

Corporate social responsibility in Malaysia was formally instituted by several companies in the 1970s. At the turn of the century, it expanded along lines similar to the CSR movements in other Asian countries (Ismail, Alias and Rasdi, 2015). In fact, the number of companies reporting increased dramatically in 2006, almost doubling the number of reports produced in previous years. This growth is attributed to increasing government and regulatory involvement, heightened awareness of sustainability concerns amongst local media and civil society, and the private sector becoming more engaged with corporate responsibility (Lopez, 2010). Among the ASEAN countries, Malaysia showed remarkable progress in sustainability reporting due to the increase of government and regulatory requirements in this case. Within the five ASEAN countries surveyed, Malaysia has the distinction of having the highest number of reporters with a total of forty-nine companies overall producing ninety-seven Sustainability Reports in the past eight years (Lopez, 2010).

This research examines the disclosure of the Malaysian business organization to describe its CSR activities as strategic philanthropy responsibility towards the stakeholder of the company.

First section, follows the introduction, is the reviewing the literature to find the issue of this research to understand the disclosure requirements and quality of the same. Second, methodology of the research gives the nature of sample companies of which sustainability reports are used for analysis and also the models of the analysis. Third, CSR reporting practice of the sample Malaysian business has been analyzed to examine its quality of disclosure. Finally, the research recommends the future research direction from the concluding remark.

Literature Review

Despite the decades-old focus of CSR on business research, the environment and education, the relevant dimensions of CSR in the community is still unclear. It is argued that not much attention has been given to the characteristics of the CSR recipients, types of corporations involved, perceptions of participants to the orientations of CSR and the types of provisions extended to the community (Ismail, et. al., 2015).

Many business firms choose a CSR agenda that conforms to the traditional approach by selecting projects and meeting social obligations and objectives irrespective of firm interest. Projects are approved because there is a budget for them. Should there be competitive benefits, they are simply the result of doing good things. In contrast, a strategic approach to corporate social activity, as opposed to simply doing well by doing well, requires that companies create and implement social projects that seek competitive advantage and economic value (Husted, Allen and Kock, 2015).

How companies attempt to position CSR in their own organizational structure and reflect it in their own norms and values has received relatively little attention until now. Here it is assumed that every company needs to give its own individual meaning to the concept of CSR, ‘with current and emerging values, acting as brakes, gearboxes or accelerators (Cramer, Van Der Heijden & Jonkere, 2006).

The opportunity for companies’ gaining competitive advantage from environmental management systems and other pollution prevention activities increasingly depends on their ability to communicate attitudes and performance to stakeholders. The publication of an index of corporate environmental disclosures on the internet could enforce the reputation mechanism and provide a competitive advantage to companies that are actively fostering social and ecological values. This would provide other companies with a strong incentive to integrate corporate social responsibility into their strategies (Bolivar, 2009).

The two distinct phases of CSR integration into an organization which can be earmarked are- successful adoption and implementation of CSR, and effective communication of the same to the respective stakeholders (Tewari and Dave, 2012). Following the rising social and environmental challenges around the world, the increasing trend of CSR reporting has been apparent. CSR Asia, an advocate of sustainable economic, social and environmental development across the Asia Pacific region, reports on ten major social and environmental issues: labor and human resources, corporate governance, environmental issues, climate change, partnerships with stakeholders, regulation and leadership from governments, bribery and corruption, community investment and pro-poor development, product responsibility and the professionalization of CSR (Zainal, Zulkifli and Saleh, 2013).

There is no clear legislative control for CSR reporting in many countries around the world, especially in the Asia-Pacific region. However, concerns relating to the extent and quality of disclosures have led to calls for the introduction of mandatory reporting requirements. The introduction of a number of international standards and global benchmarks has answered some of these reservations and provided a timely interface between voluntary and compulsory disclosure regimes (Jain, Keneley and Thompson 2015).

CSR disclosure is referred to as “a public report by companies to provide internal and external stakeholders with a picture of the corporate position and activities on economic, environmental and social dimensions” (Giannarakis and Grigoris, 2014). Social Reporting is one of the branches of Social Accounting as such firms will use communication mediums such as annual reports, social reports, promotional material, and web sites, to report their CSR activities. These reports are important to other users (such as employees, consumers, community, government and NGOs,) other than solely for financial analysts and fund managers (Zakimi and Atan, 2011). However, the extent of CSR information appearing in the annual report is varied over time, regions and countries economic development status. A number of researchers emphasized that business is under pressure from their stakeholders to report its social activities because these parties want to protect their long-term interests in the firms (Zakimi and Atan, 2011).

Of the various forms of CSR communication the most recent one is the use of sustainability report. They have evolved over a decade and have had various nomenclatures attached to them ranging from corporate social responsibility report, global citizenship report or sustainability report. But irrespective of the name under which these reports are released, provides a platform for firms to demonstrate to people at large the positive responsible corporate citizenship (Tewari and Dave, 2012).

Sustainability reports or social reports are released by the companies for the stakeholders and present the sustainability accountability of the corporate. Sustainable development reports have been defined by The World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSB) as ‘public reports by companies to provide internal and external stakeholders with a picture of corporate position on activities on economic, environmental and social dimensions’.

Sustainability Accountability has emerged for a period of time and has its roots both in philosophical accounting discussion and developments in accounting. There is a mixed pattern in the release of sustainability reports because certain organizations include the sustainable report as a section in their annual reports while others release it as a separate report (Tewari and Dave, 2012).

The sustainability reports unlike the annual reports, websites and press releases have a more structured format of reporting with guidelines, templates and ranking provided by several international agencies like Global Reporting Initiatives (GRI), Global Compact, CSR Assessment Tool, Conference Board of Canada in partnership with Imagine, CSR Insight TM Five Winds International, etc., of which GRI is the most popular one (Tewari and Dave, 2012).

Another example that supports the changing on corporate social behaviors is a study undertaken by the US magazine Fortune of the Fortune 500 companies in 1977 and 1990. In 1977 less than half of these companies embraced CSR as an essential component in their annual reports. However, at the end of 1990, it was discovered that nearly 90 percent of the Fortune 500 companies listed CSR as one of the basic elements of their organizational goals, actively reporting the CSR events held by these corporations in their annual reports (Moura Leite and Padgett, 2011).

A variety of models or frameworks such as the GRI, the ISO 14001 (Internationally Standards Organization), and the 2000 World Resources Institute (WRI) for reporting on corporate social responsibility are nowadays in place to report a corporation’s social responsibility performance. Nevertheless, the GRI framework is considered the most wide-ranging framework and widely used as an underlying framework for the coding structure of the content analysis of annual reports in both developed and developing countries context. (Khan, et. al., 2011).

To date no attempts have been made to examine corporate social reporting in Malaysia from the public relations’ perspective of issues management. Comparative studies across different national contexts have found that the practice of social disclosure is dependent on specific national influences (Keng, et. al., 2007).

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices are growing on a global scale and Malaysia is riding that momentum. The Government is one of the few in Asia to enact CSR reporting requirements for PLCs(Public Limited Companies). Since the inception of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) in 1999, sixteen different Malaysian companies published GRI reports by July 2012. There are more than three different annual award programs in Malaysia to recognize the CSR contribution of local businesses. Despite these advancement, the practice of CSR still has room for growth beyond philanthropy. CSR Asia conducted an analysis of media reporting and concluded that CSR is still largely seen as philanthropy; knowledge is superficial and partnerships need greater direction and monitoring (CSR Asia, 2009). In addition, the Malaysian Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA), in conjunction with their 2007 Malaysia Environmental and Social Reporting Awards (ACCA, 2007) revealed multiple reporting weaknesses, including companies being overly focused on philanthropic activities (UNICEF Malaysia, 2012).

There is no specific statutory requirement for public listed companies in Malaysia to disclose social information to the public, although a number of initiatives encourage corporations to report. For example, in 1990, the KLSE, the Malaysian Institute of Accountants (MIA), the Malaysian Institute of Management (MIM) and the Malaysian Institute of Certified Public Accountants (MICPA) launched the National Annual Corporate Report Awards (NACRA) to promote and enhance presentation and reporting of financial and other information. In the same year, the KLSE also initiated “The Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange Corporate Awards”. This initiative was aimed at encouraging companies to demonstrate high standards of corporate governance, disclosure and transparency. Nevertheless, despite these more recent forms of encouragement, there is a general sense that corporations in Malaysia are reluctant to report (Keng, et. al., 2007).

In Malaysia, a number of researchers have argued on the low level of CSR reporting among Malaysian firms and claimed that Malaysia is still in its infancy stage of CSR reporting. This is in spite of a number of social and environmental problems evolved as a result of continuous rapid economic growth, as well as globalization and urbanization processes that occur in the country (Zainal, et. al., 2013). Due to several environmental challenges and the corporate misconduct cases in Malaysia, the importance of extending firms’ accountability to all stakeholders and acting in a socially responsible way in all areas of business activity, are increased. Several initiatives have been taken by the government to enhance the development of CSR reporting in Malaysia. For example, Bursa Malaysia provides a voluntary guidance on CSR reporting to its members in 2006 and later made CSR reporting mandatory for all public listed firms with effect from December 31, 2007.

The mandatory CSR reporting requirement has been incorporated into the Listing Requirements of Bursa Malaysia (Appendix 9C, Part A, Paragraph 29), which obligates all public listed firms to include a description of the CSR activities or practices undertaken by the listed firm and its subsidiaries or, if there are none, a statement to that effect. However, the lack of specific reporting requirements on the content and extent of CSR reporting has led to greater variability in terms of CSR reporting provided by listed firms. It also gives the firms ample opportunity to report CSR information the way they want and this in turn puts the stakeholders at a disadvantage (Zainal, et.al. 2013).

In a study of 100 listed companies in Kualalumpur Stock Exchange (KLSE) in their annual reports from 1995-1999, the researchers found that the level of CSR disclosures in every year in their annual reports were less than 30%. Reasons of such low level were poor development and regulatory pressure until it was mandatory by the government in 2006 in Malaysia. Although the continuous effort by the Malaysian government in protecting the natural environment started in the eighties, social and environmental reporting has only been made mandatory in 2006. With this legislation, effective for annual reports for the year ending 2007 onwards, companies listed on Bursa Malaysia (BM) (Malaysian Stock Exchange) must include information on four focal areas of corporate social responsibility, namely, the community, workplace, employees and the environment (Sulaiman, Abdullah, & Fatimah, 2014).

Keng, et. al., (2007) in their study discussed the Malaysian social reporting context and reporting practice of four companies. Reviewing the literature on reporting practices, they found that in early 1980s, corporate social reporting in Malaysia was almost non-existence. Later in 1990s, most companies in Malaysia were reluctant to disclose except what was mandated. In early 2000s, some listed companies started to disclose social responsibilities, though the percentage was only 10% (Keng, et. al., 2007).

In the research (Keng, et, al., 2007), the authors evaluated the corporate social reporting of four large companies, two local and two multinationals. Using a semi structured questionnaire, they performed a thematic analysis of the respondents’ answers on the face to face discussions on the issues. Both the local and multinational responded that they were reluctant in doing reporting because it was not mandatory or not being asked for; neither from the headquarter nor from the local regulators.

Companies under the study also expressed the fact that, corporate social reporting, though not mandated, but voluntary reporting practices brought good public image that it gained competitive advantage in the long run (Keng, et. al., 2007). They also highlighted that the firms reporting on social issues had positive impact of the stakeholders and external environments impact as harmony and positive attitude. While companies which set aside the issues had negative effect from the supply chain, neighbors and other public groups who are aware of social and environmental effects of their operations (Keng, et. al. 2007).

Zainal, et. al.,(2013), conducted study on corporate social responsibility reporting of large firms listed in Malaysian Stock Exchange (KLSE) to find the differences between shariah and non- shariah. The study concluded that the firms’ disclosure significantly increased in the areas of environment and community in the years after 2007, since the KLSE made the CSR reporting mandatory from that year 2007 (Zainal, et. al., 2013).

Hamid and Atan (2011) conducted a study of CSR in Malaysian Telecommunication firms using the disclosures in annual reports. According to the research it was found that the telecommunication firms CSR involvements are increasing compare to previous period. Second, the firms involvement in CSR were studied by the activities related to community development, human resources and physical resources and environmental contribution, while it was found that among the firms’ studied most of them disclosed about the CSR related to community development and the environment related performance was the lowest. It means the firms performance of CSR, as they disclosed through annual reports over four (2002-2005) year period, they were more responsible to some community development activities rather than serving other stakeholders such as employee workplace, customers and others, especially the environment (Hamid and Atan, 2011).

Another study on top 100 listed companies in Bursa Malaysia, made by Yusoff and Yee, (2014), concluded that majority of the companies performed CSR activities, which they disclosed in annual reports, are related to community developments, followed by environment related, workplace related and marketplace related. Based on the word count analysis of the CSR reporting, the authors found that companies tend to publicize more on community related activities compared to workplace and environment, and less emphasis on marketplace.

In a study of 117 listed companies in Bursa Malaysia, Shirley, et. al., researched on web based CSR reporting. The study found that market place related reporting were the least preferred area in CSR activities of the sample firms. The study used four quadrant of CSR activities according to the Bursa Malaysia framework such as environment, community, marketplace and workplace. It was revealed that firms were reluctant to disclose CSR related performance until it was mandatory by the regulators.

Ismail, Alias, and Rasdi, (2015) studied outcomes in community development in Malaysia and opined that legal responsibility was considered the highest ranked by the participants in the study. It means companies want to abide by the laws and regulations given by government agencies and other industry performance related organizations.

Abd-Mutalib, Jamil & Wan-Hussin (2014) did a research on a sample of 300 listed firms from 11 different industries using dimensions of four focal issues of CSR disclosure; environment, workplace, marketplace and community, as outlined by Bursa Malaysia. The research found that majority of the firms have some sort of social responsibility disclosure in their annual report. Using the quality index score the study indicated about low quality while they mentioned that the content tis rather limited to general information and qualitative information.

The literature review of the research suggests that, Malaysian business firm might have been in reporting practice of corporate social responsibility performance both regulatory and voluntary following international standard guidelines since long time. But the research reviewed here revealed that the disclosure of the same has not been satisfactory to mean internationally standard practice. It is due to the fact that reporting CSR performance in Malaysian business is simply describing a few specific issues according to the company management preference to fulfill regulatory requirements and to some extent voluntary, rather than covering all the required areas important to social, economic and environmental aspects. More specifically, the review of the literature reveals that the Malaysian business CSR disclosure is not considered as strategic to fulfill the national and international requirements. Since, social reporting or CSR reporting has been found insignificant in Malaysian business; the research brings evidence of sustainability reporting in Malaysian business to examine the quality of those reporting to mean the fulfillment of the shareholders expectation.

Methodology

Malaysian company’s corporate social reporting increases over the years and happened to be the best in ASEAN countries as it was opined that corporate social responsibility in Malaysia was formally instituted by several companies in the 1970s. At the turn of the century, it expanded along lines similar to the CSR movements in other Asian countries (Ismail, Alias and Rasdi, 2015). These reports are important to other users (such as employees, consumers, community, government and NGOs,) other than solely for financial analysts and fund managers (Zakimi and Atan, 2011).

This research follows content analysis to code the CSR contents in the sustainability reports of the Malaysian business. Content analysis is a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful manner) to the contexts of their use. As a research technique, content analysis provides new insights, increases a researcher understands of particular phenomena, or informs practical actions (Krippendorff, 2013). A content analyst must acknowledge that all texts are produced and read by others and are expected to be significant to them, not just to the analyst (Krippendorff, 2013). The companies investigated in the research were awarded as the Malaysian best in the year 2015 as their delivery in the respective industries. This Frost and Sullivan awarded the best Malaysian companies as their performance in the industry and the companies the research investigated are considered best awarded companies in the year 2015. And, the sustainability reports examined were of the years 2011-2014 of the companies awarded by this Frost and Sullivan in 2015. Frost & Sullivan Excellence Awards recognizes companies in a variety of regional and global markets for demonstrating outstanding achievement and superior performance in areas such as leadership, technological innovation, customer service, and strategic product development. Industry analysts compare market participants and measure performance through in-depth interviews, analysis, and extensive secondary research in order to identify best practices in the industry (Frost and Sullivan, 2015). According to another award named ACCA Sustainability Report Award in 2011, it was found that out of 43 companies considered only 15 of them published sustainability report while others disclose through their annual reports (Best Business Practice Circular, 2013). Therefore, only 12 companies those which were considered the best performer by the Frost and Sullivan in 2015, of those web site based sustainability reports are used to code the disclosed items as CSR reporting of Malaysian business.

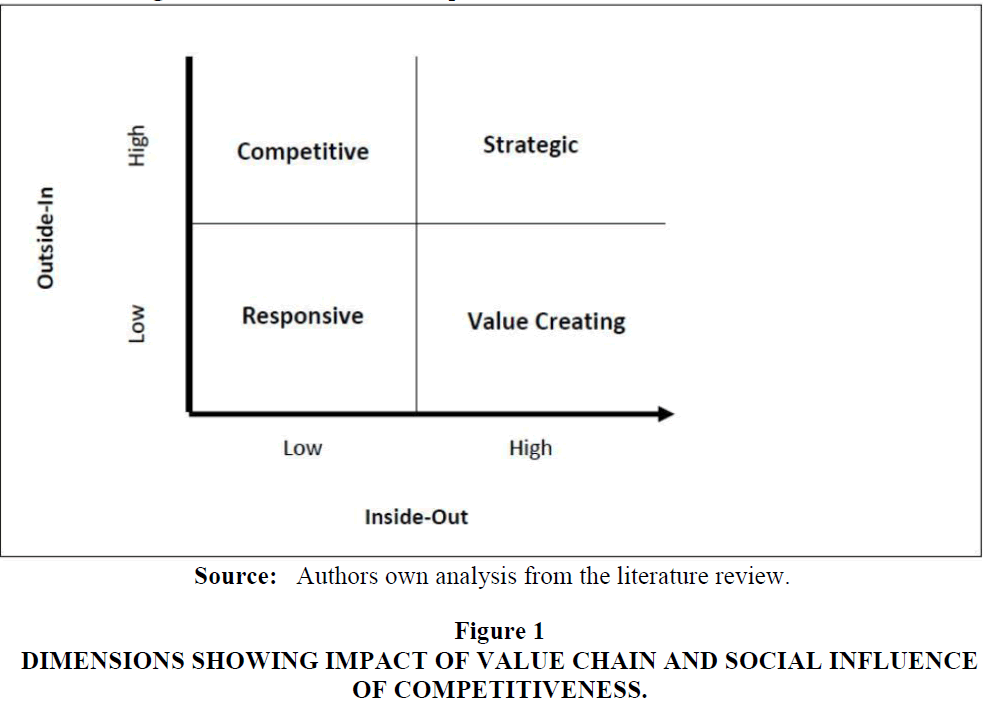

As it is mentioned in the literature review above, Malaysian business firm is not found strategic in reporting CSR performance so far, the study examines the strategic philanthropy contents of the CSR reporting by the Malaysian business organization. In this purpose, the sustainability reports of the sample companies are analyzed to find the strategic philanthropy or strategic CSR disclosure of the same. Porter and Kramer (2006) suggested strategic CSR as transforming value chain activities to benefit society while reinforcing strategy (Porter’s value chain model) and strategic philanthropy that leverages capabilities to improve salient areas of competitive context (Porter’s diamond framework). Using the criteria into two tools used by Porter and Kramer (2006), strategic approach to CSR has to be supported by two different dimensions such as internal or inside out and external or outside in while both of them are defined by the scales as measured on the respective axis of the matrix. This two dimensional matrix of strategic CSR disclosure can be depicted as below;

In the above Figure 1, the research uses two models described by Porter and Kramer(2006); Value Chain model and Nation’s Competitiveness Model to measure the extent of the two dimensions of the matrix Inside Out and Outside In respectively. This research assumes that the CSR performance of a business can be shown on this CSR Matrix (Figure 1) according to its value creating activities impact on the society(Inside Out dimension) and the firms competitiveness impact by the society (Outside In dimension), based on the models used in the study by Porter and Kramer(2006). Therefore the study develops the CSR disclosure assessment framework using the factors and the respective measurement indicators for each of the factors according to the research of Porter and Kramer (2006). This CSR Disclosure Assessment Framework is shown here as below;

Completive Advantage and Corporate Social responsibility

Now, the indicators as shown in the above Table 1 are used from the two models (Porter and Kramer 2006) considered for the two dimensions of the CSR Matrix (Figure 1). According to the degree of the dimensions, the matrix showed four different CSR performance disclosure; Responsive, Value Creating, Competitive and Strategic. The research defines the quadrant of the CSR performance disclosure as competitive when the company’s outside in indicators are high (perform more than 9 indicators out of total 18 outside in indicators) and inside out indicators are in a low position (perform less than 16 indicators out of total 33 inside out indicators), strategic when the company’s outside in indicators are high (perform more than 9 indicators out of total 18 outside in indicators) and inside out indicators are also in a high position (perform more than 16 indicators out of total 33 inside out indicators), value creating when the company’s outside in indicators are low (perform less than 9 indicators out of total 18 outside in indicators) and inside out indicators are in a high position (perform more than 16 indicators out of total 33 inside out indicators) and responsive when the company’s outside in indicators are in a low position (perform less than 9 indicators out of total 18 outside in indicators) and inside out indicators are also in a low position (perform less than 16 indicators out of total 33 inside out indicators). Using the methodology described in this section of the research, the study examines the sustainability reports of the following samples (Table 2) to measure their disclosed contents.

| Table 1: Csr Disclosure Assessment Framework | |||

| Grouping | Factors | Measure | No. of Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Outside In | 1. Factor Condition | Presence of high quality, specialized inputs available to firms | 7 |

| 2. Demand Condition | Nature and sophistication of local and foreign customer needs | 3 | |

| 3. Related & Support Industries | Availability & coordination within industries | 3 | |

| 4. Firm’s Strategy, Structure & Rivalry | Rules and incentives that govern competition | 5 | |

| B. Inside out | 1. Firm Infrastructure | Reporting ,governing and ensuring transparency by recording everything | 4 |

| 2. Human Resource Management | Effective and efficient HR practice for strategic human resource management | 6 | |

| 3. Technological Development | Performance of R & D to ensure product, process and material improvement. | 5 | |

| 4. Procurement | Efficient supply chain management | 3 | |

| 5. Inbound Logistics | Management of effects of transportation | 1 | |

| 6. Operations | Minimize environmental effects in the operations | 5 | |

| 7. Outbound Logistics | Environmentally friendly packaging and distribution | 2 | |

| 8. Marketing & Sales | CSR driven marketing mix practice | 4 | |

| 9. After Sales Service | Market oriented after sales activities | 3 | |

| Total number of reporting elements | 51 | ||

| Table 2: 2015 Frost & Sullivan Malaysia Excellence Awarding Companies | |

| Company | Award Category |

|---|---|

| Celcom Axiata Berhad | Information and Communication Technologies |

| Maxis Berhad | Information and Communication Technologies |

| Telekom Malaysia Berhad | Information and Communication Technologies |

| Sime Darby | Automotive, Building |

| UMW | Automotive |

| UEM Sunrise | Building |

| Digi Telecommunications SDN BHD | Information and Communication Technologies |

| Felda Global Ventures Holding Berhad | Palm Oil |

| MAH Sing Group Berhad | Building |

| Media Prima Berhad | The Ethical Boardroom Corporate Governance Awards 2015 |

| Faber | Home Appliance |

| CIMB | Asset Management & Finance |

Analysis and Discussion

CSR disclosures of the sample companies are examined by the coding of the two dimensions of the CSR Matrix discussed in the methodology of the research. Measuring the CSR disclosures made the by the reports examined in the research, the coded values against the factors are shown in the following Table 3. Coding to each factor is being measured in the sample report by using the indicators considered for outside in and inside out respectively.

| Table 3: Social Influences Of Competitiveness (Porter’s Diamond) In Csr Disclosure Of Sample Companies |

||||||||||||||

| According to Porter’s Diamond | Outside in/ External | Axiata | Maxis | Media Prima Berhad | Telekom Malaysia | Faber | Sime Darby | UMW | UEM Sunrise | MAH Sing Group Berhad | CIMB | Digi | FGV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Condition | 1. Availability of Human Resources | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 2. Access of Research Institutions & Universities | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| 3. Efficient Physical Infrastructure |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 4. Efficient Administrative Infrastructure |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| 5. Availability of Scientific & Technological Infrastructure |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 6. Sustainable Natural Resources | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| 7. Efficient Access to Capital |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Demand Condition |

|

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 2. Demand Regulatory Standards |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

Nationally & Globally |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Related & Support Industries | 1. Availability of Local Suppliers | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 2. Access to Firms in Related Fields |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| 3. Presence of Clusters instead of Isolated Industries | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Firm’s Strategy | 1. Fair & Open Local Competition | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 2. Intellectual Property Protection | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| 3. Transparency | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 4. Rule of Law | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| 5. Meritocratic Incentive Systems | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

Source: Authors analysis of Sustainability Reports of the Sample Companies.

The above marking (Table 4) against the factors of the two models; Porter’s Value Chain and Porter’s Nation’s Competitiveness Diamond, gives the coded values of the sample sustainability reports disclosure for each of the two models. This coded values enable the mapping of the same according to the four different quadrants of the CSR Matrix (Figure 1) and depicted in the Table 5 below.

| Table 4: Social Impact Of The Value Chain Activities (Porter’s Value Chain) In Csr Disclosure Of The Sample Companies. |

||||||||||||||

| According to Porter’s Value Chain | Inside out/ Internal | Axiata | Maxis | Media Prima Berhad | Telekom Malaysia | Faber | Sime Darby | UMW | UEM Sunrise | MAH Sing Group Berhad | CIMB | Digi | FGV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm Infrastructure | 1. Financial Reporting Practices | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 2. Government Practices | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| 3. Transparency | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 4. Use of Lobbying | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Human Resource | 1. Education & Job Training | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| 2. Safe Working Conditions | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

|

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| 4. Health Care & Other Benefits |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 5. Compensation Policies | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 6. Layoff Policies |

√ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Technology Development | 1. Relationships with Universities | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 2. Ethical Research Practices |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 3. Product Safety |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| 4. Conservation of Raw Materials | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| 5. Recycling | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Procurement | 1. Procurement & Supply Chain Practices | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| 2. Uses of Particular Inputs |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| 3. Utilization of Natural Resources |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Inbound Logistics | 1. Transportation Impacts | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Operations | 1. Emissions & Waste | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 2. Biodiversity & Ecological Impacts | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| 3. Energy & Waste Usage | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| 4. Worker Safety & Labor Relations |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| 5. Hazardous Materials | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Outbound Logistics | 1. Packaging Use & Disposal | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 2.Transportation Impacts | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Marketing & Sales | 1. Marketing & Advertising |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| 2. Pricing Practices |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 3. Consumer Information | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| 4. Privacy | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| After Sales Service | 1. Disposal of Obsolete Products |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| 2. Handling of Consumables | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| 3. Customer Privacy | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

Source: Authors analysis of Sustainability Reports of the Sample Companies.

| Table 5: Csr Disclosure Mapping Of The Sample Companies | |||||

| Sl No. | Name of Organization | Number of CSR issues disclosed (out of 51 issues) |

Strategic Mapping | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outside In (out of 18 issues) |

Inside Out (out of 33 issues) |

Total Issues | |||

| 1 | Axiata | 14 | 26 | 40 | Strategic |

| 2 | Maxis | 10 | 28 | 38 | Strategic |

| 3 | Media Prima | 15 | 26 | 41 | Strategic |

| 4 | Telekom Malaysia Berhad | 13 | 30 | 43 | Strategic |

| 5 | Faber | 5 | 11 | 16 | Responsive |

| 6 | Sime Darby | 16 | 28 | 44 | Strategic |

| 7 | UMW | 5 | 11 | 16 | Responsive |

| 8 | UEM Sunrise | 8 | 24 | 32 | Value Creating |

| 9 | MAH Sing Group Berhad | 8 | 23 | 31 | Value Creating |

| 10 | CIMB | 14 | 24 | 38 | Strategic |

| 11 | Digi | 14 | 28 | 42 | Strategic |

| 12 | FGV | 16 | 28 | 44 | Strategic |

The mapping of the sample companies CSR disclosure reveals that 8 companies are found strategic, while 2 companies are value creating and the other 2 companies are responsive. In this small sample, the disclosure of CSR performance is found strategic, meaning high in both the dimensions of the CSR Matrix i,e, value creating to the firm and competitiveness to the society. Such disclosure can be compared to any developed country practice that it fulfills both the national and international guidelines to satisfy the stakeholders’ expectation. So, this disclosure of CSR can be followed as guidelines by a listed company in BURSA to use sustainability reporting of its CSR activity.

Since, BURSA framework for CSR reporting highlights four major dimensions such as; environment, which includes climate change, waste management, biodiversity, energy and endangered wildlife; community, which includes employee volunteerism, education, youth development, underprivileged, graduate employment and children; marketplace, which includes green products, shareholder engagement, ethical procurement, supplier management, vendor development, social branding and corporate governance; and workplace, which includes employee involvement, workplace diversity, gender issues, human capital development, quality of life, labor rights, and health & safety (Bursa Malaysia 2008). The Silver Book provides a strategic framework for government linked companies (GLCs) in Malaysia to establish effective contributions and mitigate the cost of any social obligations or even transform these obligations into positive social obligations (Atan & Razali, 2013). This book mentioned about six building blocks to develop socially responsible program to create benefits to society and one of the blocks is to communicate the contributions to society as such to all stakeholders (Atan & Razali, 2013).

It is revealed from the reporting CSR practices in the sample firms according to the models studied, are showed on the strategic dimensions (Figure 1), fit into the frameworks of two leading Malaysian policy making organizations. The firms reporting issues might be the major social issues of Malaysian society and environment, which could be the major threats and opportunities by the literature reviews of the research. In this regard, this research attempts to identify some important threats and opportunities which can be addressed by the firms in Malaysia to fulfill the structural needs of the policy makers. Such a list of threats and opportunities can be shown in the following table.

| Table 6: Threats And Opportunities Of Malaysian Society | |

| Threats | Opportunities |

|---|---|

| Compliance with regulatory bodies policy requirements | Image building through proven records |

| Social and environmental obligations in a society | Green economy to value based product and supply chain |

| Stakeholders expectations on social and environmental performance | More academic and institutional scope for research and learning |

| Market dynamics for values to customers or end users | Social and environmental dynamics for competitive advantage |

Source : Authors own analysis from the literature.

It is evident that the CSR reporting of the sample firms considered strategic if they address the issues related to the social and environmental value creating activities and the national competitiveness. Now, opportunities and threats as shown in the Table 6, are becoming determinates and motivational forces of the CSR reporting firms in Malaysia. Obviously, the Figure 1 can be used as a directional matrix for the CSR reporting practice in Malaysian business.

Conclusion

Researchers (Ling and Chandran, 2007) believed that Malaysian business must have ethical and strategic philanthropy responsibility towards the stakeholders of the company. So, since early of the century, basically by the end of the first decade of the century, Malaysian business firms need to be socially responsible responding the pressures from different stakeholders. At the same time, the business in Malaysia needs to disclose its CSR performance using national and international guidelines for reporting the same CSR performance. In this research, the sustainability reports studied are of only twelve excellent performing companies to find the reporting quality according to value creating activities and social competitiveness of business. The study opines that, most of the companies those are in the telecommunication industry show CSR disclosure that are strategic philanthropy. Other firms CSR disclosures are considered as value creating and responsive by the CSR matrix. It means that all of these Malaysian business firms CSR reporting are found high- high or high-low in both the dimensions of the CSR reporting matrix (Figure 1). The research concludes that Malaysian business should disclose its CSR performance using the standards given by the Malaysian government or BURSA as the regulator of listed companies and the international organization guidelines such as one from GRI. The CSR matrix (Figure 1) derived from this research can be used as an operational guideline for a Malaysian business CSR reporting quality both in mandatory and voluntary disclosures to fulfill the requirements of the regulators and the stakeholders. In this regard, the society provides threats and opportunities, which are the necessary dimensions of the disclosure of such report in CSR performance of the firm.

Research results from only twelve sustainability reports cannot be considered representative sample to understand the disclosure quality of CSR performance in Malaysia. Secondly, the degree of disclosure by using the code against the factors of the models is measured subjectively by the researchers in the study. Finally, coding of each factor of the models, meant as the dimension of the CSR matrix, can be interpreted as less reliable to some extent.

Overcoming the limitations mentioned above, further research can be directed to study representative samples reporting using more accepted coding or quantifying for the same models used in the research. In that case, the degree of the dimension used in the CSR matrix can be defined more accurately based on pilot survey or further literature review.

References

- Abd Mutalib, Hafizah Jamil, Che Zuriana Mohammad & Wan Hussin Wan Nordin (2014). The availability extent and quality of sustainability reporting by malaysian listed firm: Subsequent to mandatory disclosure. Asian Journal of Finance & Accounting. 6(2), 239-257.

- ACCA: “Report of the Judges: ACCA Malaysia Environmental and Social Reporting Awards (MESRA) 2007”, May 2008, page 6.

- Best Business Practice Circular (2013). Corporate Social Responsibility: Guidance to Disclosure and Reporting, Kent Media House, Malaysia.

- Bolivar, M.P.R. (2009). Evaluating corporate environmental reporting on the internet: The utility and resource industries in Spain. Business & Society. 48(2), 179-205.

- Cramer, J., Van Der Heijden, A. & Jonker, J. (2006). Corporate social responsibility: Making sense through thinking and acting. Business Ethics: A European Review, 15(4), 380-389.

- CSR Asia (2009). “How well is CSR Understood in Malaysia? A Perspective from the Media”.

- CSR Asia Weekly Vol. 5 Week 32, 12 August 2009.

- http://www.csr-asia.com Frost & Sullivan Award (2015). Retrieved from the web site; http://www.frost.com/

- Garriga, E. & Mele, D. (2013). Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics. Springer, Netherlands. 69-96.

- Giannarakis, G. (2014). Corporate governance and financial characteristic effects on the extent of corporate social responsibility disclosure. Social Responsibility Journal, 10(4), 569-590.

- Hamid, F.Z.A. & Atan, R. (2011). Corporate social responsibility by the Malaysian telecommunication firms. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(5), 198-208.

- Husted, B.W., Allen, D.B. & Kock, N. (2015). Value creation through social strategy. Business & Society, 54(2), 147-186.

- Ismail, M., Alias, S.N. & Mohd Rasdi, R. (2015). Community as stakeholder of the corporate social responsibility programme in Malaysia: Outcomes in community development. Social Responsibility Journal, 11(1), 109-130.

- Jain, A., Keneley, M. & Thomson, D. (2015). Voluntary CSR disclosure works! Evidence from Asia-Pacific banks. Social Responsibility Journal, 11(1), 2-18.

- Keng, K.T., Roper, J. & Kearins, K. (2007). Corporate social reporting in Malaysia: A qualitative approach. International Journal of Economics and Management, 1(3), 453-475.

- Khan, H.U.Z., Azizul Islam, M., Kayeser Fatima, J. & Ahmed, K. (2011). Corporate sustainability reporting of major commercial banks in line with GRI: Bangladesh evidence. Social Responsibility Journal, 7(3), 347-362.

- Kilian, T. & Hennigs, N. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and environmental reporting in controversial industries. European Business Review, 26(1), 79-101.

- Krippendorff, Klaus (2013), Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. California, USA: SAGE.

- Lopez, Jennifer (2010). Malaysia Leads in Sustainability Reporting. Accountants Today. 10-13.

- Moura-Leite, R.C. & Padgett, R.C. (2011). Historical background of corporate social responsibility. Social Responsibility Journal, 7(4), 528-539.

- Pedersen, E.R. (2006). Making corporate social responsibility (CSR) operable: How companies translate stakeholder dialogue into practice. Business and Society Review, 111(2), 137-163.

- Porter, M. & Kramer, M.R. (2006). Strategy & Society. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78-92.

- Shirley, C., Suan, A.G., Leng, C.P., Okoth, M.O.A. & Fei, N.B. Corporate social responsibility reporting in Malaysia: an analysis of website reporting of second board companies listed in bursa Malaysia. Retrieved from http://www.segi.edu.my/onlinereview/chapters/vol2_chap8.pdf

- Shirley, C., Suan, A.G., Leng, C.P., Okoth, M.O., Fei, N.B. & PJU, K.D. (2009). Corporate social responsibility reporting in Malaysia: An analysis of Website reporting of Second Board companies listed in Bursa Malaysia. SEG Review, 2(2), 85-98.

- Sulaiman, M., Abdullah, N. & Fatima, A.H. (2014). Determinants of environmental reporting quality in Malaysia. International Journal of Economics, Management and Accounting, 22(1), 63-90.

- Tee Keng Kok, Roper Juliet & Kearins, Kate (2007). Corporate social reporting in Malaysia: A qualitative approach. International Journal of Economics and Management, 1(3), 453-475.

- Tewari Ruchi & Dave Darshana (2012). Corporate social responsibility: Communication through sustainability reports by Indian and multinational companies. Global Business Review. 13(3), 393-405.

- Tewari, R. & Dave, D. (2012). Corporate social responsibility: Communication through sustainability reports by Indian and multinational companies. Global Business Review, 13(3), 393-405.

- UNICEF Malaysia (2012). Corporate social responsibility policies in Malaysia enhancing the child focus. 1-58, http://www.unicef.org/malaysia.

- Yusoff, I.Y. & Yee, L.S. (2014). Corporate social responsibility reporting by the top 100 public listed companies in Malaysia. Paper presented at the 29th International Business Research Conference, Novotel Hotel Sydney Central, and Sydney, Australia. ISBN: 978-1-922069-64-1.

- Zainal, D., Zulkifli, N. & Saleh, Z. (2013). Corporate social responsibility reporting in Malaysia: A comparison between shariah and non-shariah approved firms. Middle-East. Journal of Scientific Research, 15(7), 1035-1046.