Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 6S

Corporate Social Responsibility and Culture: Exploring CSR in an Arab Context

Randa Diab-Bahman, Kuwait College of Science & Technology

Citation Information: Diab-Bahman, R. (2022). Corporate social responsibility and culture: Exploring CSR in an Arab context. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 25(S6), 1-19.

Keywords

Ethics, Business Strategy, CSR, Decision Making, MENA

Abstract

The extant literature includes many studies of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and its impact on business ethics and outcomes. However, while CSR is well studied in general, the impact of culture on CSR is largely understudied in an Arab context. This is surprising, given that previous research has acknowledged that cultural factors can potentially have a big impact on the understanding and expression of CSR. This research therefore sets out to explore the understanding and expression of CSR in an Arab context. It does so through a qualitative pilot study with prominent CSR Experts (people with leading roles in CSR in the private, public and non-profit sector) in a predominately Islamic setting. The study confirms the importance of cultural elements in influencing the understanding and expression of CSR. Interestingly, the also highlights the importance of the Islamic religion and specific aspects of its religious doctrine as being particularly important to understanding why CSR may be expressed differently in an Arab context. The implications of these findings are important for policymakers as it can help them better align their CSR initiatives and better understand their possible impact on stakeholders. The study concludes by positing that further research is needed to explore the impact of aspects of the Islamic Religion on CSR.

Introduction

At the beginning of the 21st century, various challenges came to the forefront of human beings, which mainly constituted environmental and social issues such as climate change, increasing inequality, poverty, to name a few. Consumer and societal factors have identified companies as an efficient means to look after the significant issues and act as a change agent by participating in improvement initiatives (Marquina & Morales, 2012). Accordingly, (CSR) rose to fame and became a trending topic amongst scholars (Rundle-Thiele et al., 2008). As per Rahman & Norman (2016), CSR serves the purpose of long-run interest and survival of the firm in a socially responsible economy. Therefore, nowadays CSR activities are adopted by the majority of corporations in the field of social, environment and economic performance (Rahim et al., 2011). Further, contemporarily, CSR is not viewed as a cost but rather an investment, which will, in turn, bring extensive profits (Pohle & Hittner, 2008). Rochlin, et al., (2005) stated that business strategies which incorporate and focus on environmental, societal and economic performance for long-term become a part of the organization and result in the creation of value for both the firm and society.

The difference between how CSR is expressed in various parts of the world is attributed to multiple reasons, particularly social norms and values which differ around the globe (Matten & Moon, 2008). Recently, varying responses to CSR related stimuli called for more research into examining the non-homogenous results (Sukhdeo, 2020). Also, according to Sidiropoulos (2013), the behavior of organizations is driven by human values and culture, which has been noted to be more often a source of conflict than of synergy (Petrakis, 2014). Therefore, Hofstede’s model which provides an excellent understanding of the different cultures, can give insight on why conventional measures of CSR may not be as affective in some cultures when adopted from external cultures (Hofstede et al., 1990). The varying pillars of value and social norms may be impeding the understanding of the locals if conventional values are adopted generically. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate, from a local lens, what implications national culture may play on CSR understanding, initiative, and participation.

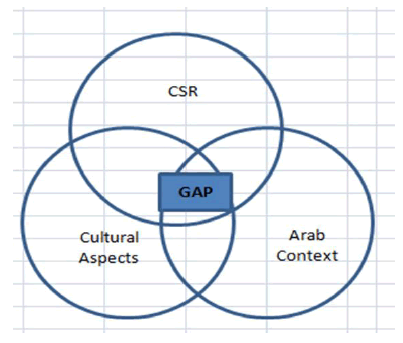

Although there are many framework on national culture developed, Hofstede’s framework is still one of the most widely used frameworks among the scholars and practitioners. Christie, et al., (2003) had showed in their research that there is a strong relationship between Hofstede’s cultural dimensions of individualism and ethical attitudes of business managers when it comes to CSR. Also, in their work on the subject, Burton, et al., (2000) found a correlation between CSR & culture when they compared the USA and Asia. As well, research on the effect of national culture on CSR orientation between Dutch and German business students by Bode (2012) found a clear correlation between the two elements. Moreover, Bode (2012) found that the higher the individualism scores of a respondent, the more importance they viewed non-economic responsibilities. More recently, Chang, et al., (2013) also found a similar correlation when comparing Singaporean and Malaysian cultures and their impact on CSR. Lack of awareness and understanding of what constitutes CSR from a local perspective could prove to be detrimental to impact of initiative. Thus, it is important to investigate whether or not policymakers feel that they align their CSR mission to stakeholder needs, relevancy and understanding. The gap is depicted in Figure 1 below:

Aims and Objectives

The study aims at understanding how various stakeholders perceive CSR in an Arab context, with a view to providing a deeper understanding of how culture can impact CSR and its expression in an Arab context. The aim will be fulfilled by investigating the following research questions based on existing literature:

• Research Question 1: How is CSR understood in the Arab Context?

• Research Question 2: What terminology better explains how CSR is expressed in the Arab context?

• Research Question 3: How does culture impact the theories and practices of CSR in the Arab context?

Literature Review

Defining CSR

CSR can be defined as the developing and ongoing obligation by organization to conduct business in an ethical manner, while contributing to economic development as well as enhancing and refining the quality of life of the company’s employees, their families, and local communities (Ghobadian et al., 2015). Ray (2008) concluded that corporate social responsibility has allowed companies all over the globe to fulfill their social duties towards their employees as well as the stakeholders at all levels. This has been the case of the corporate sector at all levels in all countries. The fast trending companies in recent times have increasingly becoming dependent upon the attitude of the employees which are an integral part of the company and the industry in cases of the sustainable performance and liberalization as well as effective CSR practices. Corporate social responsibility in terms of the cultural difference and governance has been adopted by the industrial sector in the current times of globalization. Corporate Social Responsibility has become a major topic of discussion for almost all organizations. These major organizations have engagements in CSR due to many reasons like demand from controlling bodies. According to (Glavas, 2016), almost 93% of the major global companies make formal reports on corporate social responsibility. The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (2017) primarily defines corporate social responsibility as a management term which involves the integration of social and environmental issues by organizations in their operations of business and interactions with their stakeholders. Generally, it is a technique by which an organization or a company attains economic, social as well as environmental imperatives and address the shareholders’ and stakeholders’ expectations.

CSR has gained widespread interest and broad activities are diffused in all different types of firms at the majority of levels (Koleva, 2021; Jamali et al., 2020; Ismaeel et al., 2020). Countries are shifting their focus towards CSR activities due to the importance attached to it and its connection to the consumer’s behavior and perception. With the increase in competition at global level and companies goodwill attached with the social assets employed, CSR is important to be incorporated into an entity’s core strategy (Avina, 2013). Media and the technological advancement has given unlimited access to the population about the CSR activities undertaken by the firms, and consumers behave according to the information received and perceived (Wagner et al., 2009). And wide ranges of opportunities are opened to the firms to craft their activities and present themselves in a better picture by fulfilling demands of the stakeholders (Groza et al., 2011).

According to academics in the field of CSR (see Jamali et al., 2020; Ismaeel et al., 2021; Koleva, 2021), there has been an increased pressure for the business world currently to adopt and further enhance its corporate social responsibility. The imperatives of this kind of pressure are both moral and strategic. As mentioned above, moral imperative has the notion that businesses are obligated to their shareholders as well as their stakeholders, including the whole society and thus they must play a role to address some of the globalization ills. On the other hand, the strategic imperative bases its argument on the fact that CSR has the potential of improving an organization’s competitiveness. Glavas (2016), further mentions that this imperative has been largely debated at the business level, but its conceptualization has not been adequate at the macroeconomic level. This has made CSR a surprising issue because it has been made a priority on most agenda of government strategies. It is alluded by (Boulouta & Pitelis, 2013), that most organizations are now engaged in strategic corporate social responsibility with the end results being an increased level of financial as well as social performance.

CSR in Various Regions

Exploring CSR activities in the Middle Eastern countries amongst countries like Kuwait, Oman and United Arab Emirates (UAE) bring to light that such activities have been an integral part of the businesses since the Islamic times. Most companies in these countries have been carrying out the activities based on the Islamic values such as Zakaat & Sadaqa (donations & alms) (Dadfar, 1984). Donations and other philanthropy activities have been in complacent with the Islamic Shari’ah laws, which are a system of values and beliefs adopted from various doctrines of Islam’s Holy book, the Quaraan. In recent times, the focus has shifted to grander schemes, on agendas of both local government and non-profit organizations to address UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, to focus on contributing more profits into communities as well as the environment. The CSR at government level in countries like Kuwait and UAE is crowded with the instances of social welfare which is aimed at increasing the quality of life of people while bringing more and more social and economic stability. It includes the establishment and growth of infrastructure and municipal services, education and health. It can be concluded that the CSR in Middle Eastern countries have taken a new shaper in the recent times. More and more companies have been going on board the idea of sustainable CSR practices as well (Ali, 1995). As per business ethics described by Hofstede & McCrae (2004), it is to be understood that in order to become a part of the country’s culture, to has to be assumed that the company will not be isolated form the culture and will be impacted but the social and cultural environment of the region(Hofstede & McCrae, 2004). It is further believed that national and regional adaptation of CSR is required when company has a major cultural difference from the foreign country’s market. Since the ethical actions of an individual or an organization are entangled in the culture and society, it is assumed that the ethics of a firm’s conduct will be changing as per the foreign country (Ajiferuke & Boddewyn, 1970).

Stakeholder-Defined CSR

Due to the fact that CSR is relative to the environment in which an entity exists, it is essential to take into account the views of the stakeholders involved. According to Hillenbrand & Money (2007), stakeholders are people are a group of people that have or can claim, ownership, interests as well as rights in an organization and its practices, whether past, present or even future. Stakeholders can be grouped into primary and secondary stakeholders where the primary stakeholders are the key for the company upon which the organization cannot survive on their absentia. There exists a strong link between an organization and this kind of stakeholders. Secondary stakeholders are those that have an influence or affected by the corporation but are not involved in the corporation’s transactions and are never important for its survival.

When it comes to an organization’s internal environment, Hillenbrand & Money (2007) and Bari? (2017) argue that other than the positive as well as the negative impact on profitability and economic development, CSR impacts the satisfaction, loyalty as well as the motivation of workers, and at the same time giving the management opportunity of extracting the best employee qualities which are direct contributions in the creation of positive business trends. A higher level of CSR affects the loyalty of the task force which enhances significantly business processes efficacy. Moreover, Hillenbrand & Money (2007) further suggest that a higher degree of motivation, loyalty as well as satisfaction which is affected by socially responsible business activities allows the workers alongside other internal stakeholders to adapt to the organizational values and norms.

As per Hofstede, et al., (1990) research, higher values of Power Distance contribute to the decision making of the stakeholders in the CSR activities. Further, the high value of individualism is also an indication that most stakeholders will be targeting their benefits in making decision about CSR activities (Hofstede et al., 1990). Moreover, it has been claimed by Hofstede (2011) that the unequal distribution of power is a clear indication of the fact that this inequality is equally propagated by the leaders and people in the culture.

Dimensions of Culture

Defining Culture

Value systems of different cultures have been of interest to researchers for many decades. The very thing which make a ‘culture’ or the pillars of what is often referred to as ‘values’ is ever-changing across the globe, as cultures and societies become more reachable and transparent in accordance with the latest technologies (Visser, 2008). Human action and behavior is a complex issue, with many varying arguments stemming from psychology and dwelling well into every aspect of science which involves cognitive thinking. Prevailing values are continuously found to play a dominant part as an indicator to human behavior, which inspires conversations of underlying motivations (the why’s) of individual behavior (Matten & Moon, 2008). Investigating the topic enables researchers to possibly bridge the gap between theory and practice, in a multitude of issues including decisions and activities such as CSR. Although it was found that management practices and their effectiveness varies widely by country (Sidani & Al Ariss, 2015), it is argued that such distinctive qualities continue to take effect – possibly at an even more rapid speed due to heavy exposure to other cultures and interdependence of world markets. Thus, it is essential to explore the topic further as cultural dimensions have been claimed as the pillars to the differences which exist amongst nations, which in turn help explain the practical outcomes of their collective human behavior – their governance and policies, which is expected to stipulate their values, norms and expectations.

In a debate by Edward Tylor (1871), he states that culture is a complex aspect which comprises of knowledge, morals, custom, belief, art as well as law together with any other abilities and behaviors that are gained by man as a society member. Tylor’s definition is opposed by various scholars as it packs in much into its definition with both psychological items (e.g., belief) and external items (e.g., art). Most scholarly definitions of culture, including those of and Herskovits (1955); Geertz (1972); Boyd & Richerson (2009); Ryle (2011), among others, in summary give culture the characteristic of an aspect that is shared largely by people of a common social group as well as being shared in virtue of being part of that social group. From Hofstede, et al., (2005), culture is defined as the cumulative knowledge deposit, beliefs, values, attitudes, meanings, hierarchies, religion, time notions, roles, spatial relations, universe concepts together with material objects and possessions that are gained by a group of individual in generations’ course by the striving of individual or group. Geert Hofstede, who is a leading scholar in the classification of cultural values, produced a framework of national culture that assists in giving an explanation to the differences in basic culture (Hofstede, 1984, 2021). The theories he presented have been laying the foundations for research in the field of cultural and behavioral inspection across cultures. The cultural dimensions presented by Hofstede was based on six main domains Including Power Distance (PDI), individualism (IDV), Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI) and Masculinity (MAS), Long Term Orientation (LTO) and Indulgence (IND). These have been the dimensions which allowed researchers to categorize the various societies of the world and effectively give them a score. Clearly, these cultural dimensions scores are in accordance with the practices of the local societies and have given researchers a perspective about how societies around the globe can be compared to one another. Hofstede’s contributions from his early work at IBM have been proven very worthy for cross cultural research (Ali, 1995) (Ali, 1995).

Moreover, in Hofstede, et al., (1990) research on the national culture of seven Arab countries, he gave them the title of the “Arab Group”. In his classification, the Middle Eastern countries showed a higher power distance, mostly strong uncertainty avoidance, a higher level of collectivism, and a modest Masculinity/Femininity (Hofstede et al., 1990). It was further signified by the research done by Weir (1993) that the unique features of the Middle Eastern countries and their culture can be best ascertained by accompanying the factors like management practice in these countries in comparison to the paradigms in American, European, and Japanese cultural models (Weir, 1993). It was established further by Dadfar (1984) that the Middle Eastern countries have a cultural model more deeply grounded in the Islamic, social, and political values of the people and the countries.

Culture in the Gulf

During the past decade, some Arabian Gulf cities like Dubai and Abu Dhabi have emerged as global hot spots due to their technological and social advances (Torstrick & Faier, 2020). These Gulf countries, despite their advances in technology and social norms, have tried to preserve their national identities and traditional culture while adapting to modern life. In Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman as well as the UAE, culture and customs are still upheld in many aspects of life, predominately the conservative nature of everyday life, gender roles and expectations, as well as their culture and customs (Torstrick & Faier, 2020).

In the MENA region, research is slowly but surely starting to emerge on the topic. Though the links between Hofstede’s dimensions of culture and social responsibility have been established on multiple levels, they are yet to be explored extensively in the area. Recently, there has been an interest in the topic as more business is being conducted with the West, and as CSR indices continue to be of interest to foreign investors. Moreover, the frequent occurrence of fraud and corruption in the recent years has accentuated the necessity and importance of identifying business ethics as CSR. But, most of the existing research in the MENA region uses static data to investigate associations between CSR from the aspect of reporting based on cultural dimensions. There is a dearth of research which actually examines CSR initiatives and activities and how they are expressed in relation to culture in the region.

Also, as CSR and cultural matters continue to be explored in the region, new research has shown that religion could be highly influential on CSR initiatives, as religion is already well recognized in the literature as a social construct (e.g. McNichols & Zimmerer, 1985; Barnett & Karson, 1987; Barnett et al., 1996).While the tenents of Christianity, (Abela, 2001; Emerson & McKinney, 2010; Karns, 2008; Lee, McCann & Ching, 2003) and Judaism (Lewison, 1999; Pava, 1998; Tamari, 1991) have reviewed and explored the role of religion in business ethics, studies on the Islamic perspectives including CSR, are at best scattered and scarce but are likely to be embedded through direct or indirect religious reference, on one’s behavior (Ali, 2014). Recently, Koleva (2021) explored the implications of religion on CSR in the MENA region. The findings of his research suggest that religion (Islam) is very important and helps understand and make sense of CSR. Furthermore, his study revealed that leaders from that part of the world share the common belief that they as individuals but also the organizations they represent, have the moral obligation to support local communities and provide response to stakeholder concerns that could be regarded as voluntary or government responsibility in the Western context (Koleva, 2021). He concluded that CSR in the examined context is not constrained within the boundaries of corporate performance and is not aligned with any specific corporate objectives.

The results of another recent study in the region suggest that CSR reporting is still at its early stages and is primarily driven by linkages and obligations to the global economy, and that belonging to environmentally sensitive industries does not appear to impact CSR reporting on the matter (Ismaeel et al., 2020). This confirms the view that CSR reporting is usually adopted by companies in developing countries as a way to respond to global stakeholders and their expectations. Lastly, Al-Abdin, et al., (2018) have also explored CSR and culture in the MENA region and identified gaps of collaboration between business and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), and the impact of stakeholders and institutions on CSR.

A prevailing debate in CSR literature is about the contextual nature of CSR (Visser, 2008). For instance, Khurshid, et al., (2014) argue that CSR activities could be affected, among others, by religious and cultural norms. From an Islamic perspective, the benefits which members of organizations gain from engaging in CSR are that they meet Islamic obligations and obtain rewards from God in the hereafter for their good deeds (Koleva, 2021). For example, Alfakhri, et al., (2018); Koleva’s (2021) research revealed that some countries in the Gulf region, where religiosity is considered to be high, view CSR as more of a religious duty, similar to what Wang & Juslin (2009) reported from China which they labeled ‘The Harmony Approach’. Indeed, social responsibility is deemed to be ingrained in the Qur’an and the Sunnah as Islam assumes a Shari’ah (or Islamic law) approach to CSR with foundations on the Qur’an & Sunnah (Ahmad, 2003). Williams & Zinkin (2010) even consider that Islam is fully in accordance with the CSR agenda of the UN Global Compact.

Methodology

Research Framework

This empirical study will be conducted using a qualitative content analysis. In accordance with the literature review above, exploring the local perspectives of CSR requires an investigation of what is currently being done and deemed important from those who participate in it and/or report it, and to what degree they believe culture impacts it.

Selection of Participants

Participants were selected through purposeful sampling, which is dominant strategy in qualitative research. Patton (2002) asserts that the logic and power of purposeful sampling lies in selecting information-rich cases for in-depth study. In total 12 experts in CSR in difference fields were chosen – 8 men and 4 women – all of which were personal contacts. All of the participants are from within the local community in Kuwait, and are either experts in the field of CSR, policy makers or practitioners.

Tool Development

The development of the initial research instrument, the interview guide, uses the logic of a restricted phenomenological approach in order to serve its purpose of gaining feedback from a first-person point of view. This selected approach is meant to elucidate the experience as lived by a group of people. Patton (2001) notes that a phenomenological study is one that focuses on the description of what people are doing and how they experience what they experience.

The interview guide is designed based on three categories as noted below:

A. Awareness and understanding of CSR.

B. Expression of CSR in local culture.

C. Influence of culture on CSR.

Each category was associated with five basic questions derived from the generic literature reviewed above as described in Table 1 below:

| Table 1 Interview Guide |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Research Topic | Assessing the moderating effect of culture on the relation between CSR | ||

| Objective 1: To explore understandings of CSR in the Arab Context | |||

| Objective 2: To verify the terminology & see if CSR should be expressed differently in the Arab context | |||

| Objective 3: To study/explore the theories and practices of CSR and its relationship to cultural dimensions. | |||

| Ice Breaker: | Can you tell me about your journey with CSR in your current position and how you have implemented related initiatives? | ||

| Research Question 1 | How people understand CSR in Kuwait? | 1. How would you explain the concept of CSR to those who knew little about it? | |

| 2. How do you think most businesses in Kuwait understand the concept of CSR tobe? | |||

| 3. How similar do you think CSR is to other concepts such as Corporate Responsibility, Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability? Which term do you find most useful, why? | |||

| 4. Do you believe that businesses in Kuwait generally responsible? Why/ why not? Are they embracing aspects of CSR? In what ways? (economic, social, environmental, political) | |||

| 5. Do you believe CSR (or related terms) are a useful tool to drive greater responsibility in business in Kuwait? In what ways, If so why? If not why not? | |||

| Research Question 2 | What is culture as expressed in the local society? | 1. How would you describe the Kuwait culture to someone from outside of the Arab world? | |

| 2. How do you think CSR (or related terms) adapted (by you or others) to the Arab context? | |||

| 3. How could CSR (or related terms) be adapted to be more culturally sensitive in the Arab world'? | |||

| 4. Can you think of an local example where you feel CSR has been implemented successfully? Why was this successful? (probe built-in vs bolt on?) | |||

| Built in - contemporary, clearly integrated into the org strategy with clear aims | |||

| 5. Can you think of a local example where you feel CSR has been implemented poorly (unsuccessfully)? Why was this unsuccessful? (probe built-in vs bolt on?) | Bolt-on - more traditional, one-offs | ||

| Research Question 3 | How has our culture influenced the expression of CSR? | 1. What do you think are some cultural barriers we are facing that implicate our acceptance/success of CSR? | |

| 2. What would it look like in our ideal world/ how would it be expressed locally? | |||

| 3. Do you have any other things to add? Any questions for me? | |||

| Added new: | |||

| 4. Enough education about SR in general in the classroom? | |||

| 5. What can we do to improve/change this? | |||

Participants of the study were part of a government entity, NGO or top officials in the private sector in order to get an overall view of the different sentiments. The candidates were then given a code in order to ensure their privacy. Throughout the findings, they will be referredto as SO1, SO2, etc, as highlighted in Table 2 below.

| Table 2 Process of Data Analysis & Examples |

||

|---|---|---|

| Aggregate Dimensions | 2nd Order Concepts | Example |

| Locals' understanding of CSR | How institutes understand & express CSR | “The reality of the situation is that most initiatives are done to show a personal dedication to societal norms" (SO5) |

| “Resources are widespread throughout the community by willing volunteers” (SO1) | ||

| “Supporting those who do good is considered a top priority” (SO11) | ||

| Similarity to conventional CSR practices | "CSR is alive & well here since centuries" (SO12) | |

| "The main purpose is to satisfy stakeholders but here its to satisfy God" (SO3) | ||

| Expression of/Perspective on Local Culture | Local adaptation to conventional CSR | “Our religion enforces sympathetic values |

| We become the brand, our values represent it” (SO11) | ||

| “The goal is to build relationships with the community that we both find important”(SO6) | ||

| Cultural impact | “There is a religious aspect which makes announcing good deeds a taboo” (SO10) | |

| “Community reputation is extremely important to any company as the name of the owners is associated with their brand” (SO9) | ||

| “Engaging with the community is done by sharing their experiences which are important to them” (SO12) | ||

| Barriers & Motivations to CSR | Barriers & implications | “Good deeds should not be announced openly “ (SO2) |

| “The locals here love to see an immediate impact” (SO1) | ||

| “There is no communication or synchronization between responsible bodies” (SO4) | ||

| Motives to succeed | “Those active in CSR have international ties” (SO7) | |

| “Impacting a single unit or cause is considered a big win for all” (SO4) | ||

| “CSR activities which are most impactful are ones which the people can clearly see how to partake in” (SO8) | ||

Data Analysis Methods

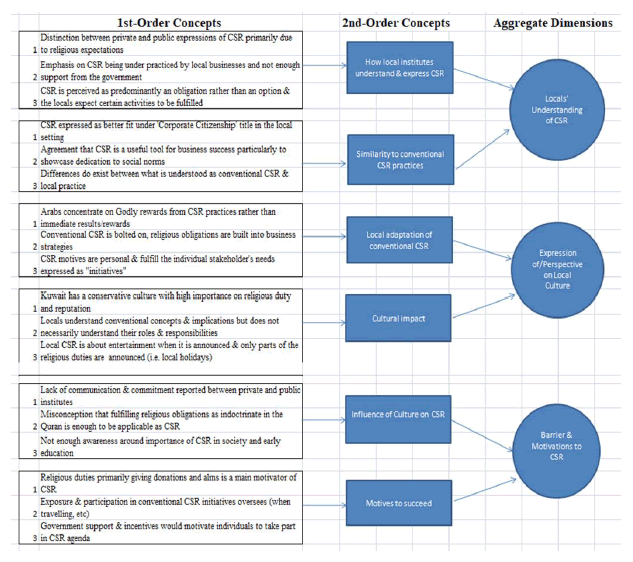

Using the thematic analysis approach and, in particular, Gioia’s Methodology (Gioia et al., 2013), which shows how the data collected is linked to the insights gained; the data was organize into first-order concepts and second-order themes. In filtering the 1st-order analysis, quotes from the interviewees are codified to look for similarities and differences in order to label data into concepts. Then, the 2nd-order analysis is conducted to relate the established concepts from the first order into theory using emergent themes, which may then be turned into aggregate dimensions needed to develop a data structure to visually aid theoretical development. The data is depicted in Figure 2 below:

Furthermore, the process which the initial research follows is in accordance with Gioia’s Methodology as described above. The process is highlighted further in Table 3 below, where examples are given in accordance to the process:

| Table 3 Process of Data Analysis & Examples |

||

|---|---|---|

| Aggregate Dimensions | 2nd Order Concepts | Example |

| Locals' understanding of CSR | How institutes understand & express CSR | “The reality of the situation is that most initiatives are done to show a personal dedication to societal norms" (SO5) |

| “Resources are widespread throughout the community by willing volunteers” (SO1) | ||

| “Supporting those who do good is considered a top priority” (SO11) | ||

| Similarity to conventional CSR practices | "CSR is alive & well here since centuries" (SO12) | |

| "The main purpose is to satisfy stakeholders but here its to satisfy God" (SO3) | ||

| Expression of/Perspective on Local Culture | Local adaptation to conventional CSR | “Our religion enforces sympathetic values |

| We become the brand, our values represent it” (SO11) | ||

| “The goal is to build relationships with the community that we both find important”(SO6) | ||

| Cultural impact | “There is a religious aspect which makes announcing good deeds a taboo” (SO10) | |

| “Community reputation is extremely important to any company as the name of the owners is associated with their brand” (SO9) | ||

| “Engaging with the community is done by sharing their experiences which are important to them” (SO12) | ||

| Barriers & Motivations to CSR | Barriers & implications | “Good deeds should not be announced openly “ (SO2) |

| “The locals here love to see an immediate impact” (SO1) | ||

| “There is no communication or synchronization between responsible bodies” (SO4) | ||

| Motives to succeed | “Those active in CSR have international ties” (SO7) | |

| “Impacting a single unit or cause is considered a big win for all” (SO4) | ||

| “CSR activities which are most impactful are ones which the people can clearly see how to partake in” (SO8) | ||

Findings

Locals’ Understanding of CSR

How Institutes Understand CSR

Within the first few interviews, a pattern emerged which distinguished conventional CSR and how it is expressed in Kuwait. It often took us back to the pre-discussed element of ‘Define CSR’ within these interviews. As the interviews went on, there seemed to be a clear distinction in the type of activities which are expressed as social responsibility. It took us back to the macro definitions which insist that CSR is about giving back, but there was a difference between community involvement and community engagement. All of the interviewees agreed that conventional CSR was a Western concept and that it was not exactly misunderstood in Kuwait, but rather implemented and expressed according to the cultural expectations of the local environment. As one of them expressed, “I think it is an American concept…some countries or regions are able to adapt it ‘as is’ but I think we are far from that in the Arab region.” (SO2)

Primarily, the conventional CSR approach was understood by these professionals as a means to give back, with words and expressions being repeatedly used such as “giving back to society”, “empowering others,” and “a way to contribute to a greater cause.” As another expresses, It is never a clear strategy we do not necessarily have this way of thinking that ‘oh we must do CSR’ it’s like a given that we have to serve the community and always give back.” (SO12) As well, most of them mentioned that CSR should be measurable, and that typically they should be aligned with global SDG goals. Those working in the financial sector referred to international indices as their benchmark of efforts, while the socialists and marketing professionals stated that CSR was more about the broader concept of the 3P’s – People, profit, planet. With these notions in mind, it was unanimously agreed that CSR does take place in Kuwait in this broader sense as expressed, but that the details of how it is implemented differed from one company to another. One interviewee mentioned “…we think differently…our culture is different…to us it’s about what we can give back in terms of what we can do to help others around us…we are so good at this our late Amir has been labeled the AMIR OF HUMANITRIANISM by the UN” (SO1)

Furthermore, another important theme which consistently came up is that of the religious obligations implemented through CSR. It was unanimously agreed that most, if not all, CSR campaigns in Kuwait have a major part dedicated to giving alms or donations in various forms, especially during religious holidays. Companies are also particularly keen on answering calls for disaster relief and aid from surrounding nations, particularly Muslim ones. This is all in line with the Islamic religious practice of ‘Zakat’ or ‘Sadaqah’, which in their simplest form mean ‘alms’ or ‘donations’. However, there are multiple debates on their individual meanings as conservative observers of the Islamic religion have strict definitions for each of these religious duties, for example some do not consider alms as charity of a certain type if it is announced, and debates are endless as to whether or not these are compulsory aspects of the Islamic religion or preferences/acts of goodness. “We like to think of ourselves as living beings that are here to serve God that is how we are raised…that is what our parents and our schools taught us. This mindset is entangled with everything we do ….somehow we end up valuing our self and our productivity based on upon this way of thinking. It always ends up in the way we do our jobs.”(SO6).

Similarity to Conventional CSR

The conversation with the various interviewees revealed many aspects of the local understanding of CSR as well as how these initiatives have been implemented throughout the years. Every single one of the people interviewed agreed that CSR is utterly misunderstood in the context that it is presented in Kuwait. As one of them conveyed, “Yes, sure there are different things we can do better but I wouldn’t say that we do not have CSR, we have it, and it is alive and well and runs through our blood. Our basic mindset traditionally gravitates to social norms and expectations which we grew up participating in….most of the time it is what we learned that we are obliged to do, like alms and donations/food/shelter (to those in need)” (SO1). It was also clear that the people interviewed are actively seeking to change the local perceptions through their professional and voluntary work, and that they are slowly but surely gaining the momentum to do so. As well, they were all in favor of a proactive approach forward through collaborations and awareness, as well as including the government sector in such initiatives. As another explains, “I usually see what big companies (with international presence) are doing and I try to twist it towards the local flavor” (SO6).

Moreover, most Kuwaiti business have been reported as understanding the need to give back, but they do so in an unconventional way than traditional CSR implementing it in a customized way, bolt-on kind of way rather than having a clear built-in plan of action. The local businesses are considered by the majority to be in tune with the social expectations of the local community. As well, religious expectations are considered paramount and are considered standard CSR throughout the calendar year, particularly within the various seasons of religions holidays according to Islam. Most participants were concerned as to the subjectivity of the way CSR is implemented, some even saying that many only understand it as a monetary contribution. Others expressed their concerns for the drastic differences in how it is locally expressed, particularly in financial institutions, and thought that conventional CSR is more of a publicity stunt for the international audience rather than to fulfill the expectations of local stakeholders. One of the interviewees said “Most banks and financial institutes are way ahead in their CSR events which they hold….they are not really expected to do it this way by the locals, but primarily it is due to their international dealings and their international stakeholder expectations. We understand why they do it and locals are happy to participate in such events like marathons.” (SO7). It was also frequently expressed that many local companies take on initiatives collectively when there is hype on the subject, but little is achieved as they are often short-lived. This was expressed as a negative step as “we cannot all be doing the same thing all the time” (SO7) as stated by one of the interviewees.

Expression of/Perspective on Local Culture

Local Adaptation

The Kuwaiti culture is described as conservative one, with family and religious values consistently being mentioned. The key words which most respondents used when describing their culture were “conservative”, “religious”, and “righteous” and word of mouth and reputation was paramount in the society. Some expressed that it was essential for the locals to confirm their participation in these elements in the way they act, dress, and express themselves. Others stated that, although we seem to be “open” particularly in our business dealings and way of life, our views remain in line with that of our forefathers. As one expressed, “The Kuwaiti society is interesting…we are always looking to try new things, we have the money, they knowledge, but in many ways we are ‘stuck in our own ways’ no matter how much we are open or liberal we seem.” (SO12) Much of our values and upbringing has remained intact according to the strict ways of previous generations. For example, arranged marriages are still the norm within the society and dress codes are adhered to according to tradition also in accordance with religion, as one expresses “It is a religious society, we are modern but we are conservative at heart.” (SO8)

Many respondents stated that much of the CSR initiatives that they usually see around town are often un-intended as CSR. Some pointed out that it is mostly the big global corporations who actually use such definitions for the events and activities they host which fall under the umbrella of CSR. Others stated that, even when such events happen in a way that is pre-defined and strategized as CSR, it is not usually advertised in such a way to the public. One explained “The way we do it here (Kuwait) is usually not structured…I don’t think we can measure it unless we count the number of “events” which were held by a certain company. I would say that it would be difficult to have any kind of real measure, but I also think that such measures can be misleading…or rather difficult to measure…as long as the community keeps showing up to one that is the real measure.” (SO5) Moreover, the way that most of the people interviewed said that CSR is adapted to an Arab context is that it was relative to the sentiments of the public, that is was about pleasing social expectations in order to enhance the community relations of the brand.

Furthermore, CSR, though not a foreign term to locals as expressed above, is seen as foreign to the local culture in that they do not necessarily see any added value in participating in it as expressed by the interviewees. However, in the way that CSR or elements of it are presented locally, it is agreed that the idea of CSR could use some refinement in alignment to the expectations and the reactions of the various stakeholders. In their opinions, some expressed that CSR could be considered a service to the local people, in that companies should have a calendar of events which correspond with local celebrations as that was the most impactful way in terms of stakeholder reaction. Some expressed that, at the end of the day, the bottom line is what the initiatives do for the brand in terms of popularity, acceptance, and word of mouth. From this point of view, interviewees expressed that the Arab culture is keen on word of mouth and that free giveaways and fun activities were a main element to incorporate into the local adaptation of CSR. Those events seen as CSR were the most successful. Others, expressed by the interviewees as being bad examples of local CSR, included those which were “copy-paste” from the West, particularly green initiatives. As one stated, “We know what we are expected to do, we are just having a hard time taking the copy-paste approach….that does not mean that following international standards is not important” (SO10)

When asked what CSR means to them, the most common response was that CSR is a service to the community, a way to give back and prove to the community that the company cares. The interviewees also expressed unanimously that CSR should have a measurable element or some kind of tangible outcome in order for it to be effective. As one expressed, One explained “If I set out to measure environmental impact for example, that is relatively easy to do…but other elements which are not tangible …which do not produce immediate results…can be very difficult to measure.” (SO5) The majority highlighted the need to consider all stakeholders and some mentioned the need to address both local and international concerns. They also expressed concern as to the awareness of what may constitute as a CSR activity due to its many definitions and comprehensions. The majority also stated that CSR initiatives should at least be aware of international standards such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) or FTSE4 Good, and have an idea of the scope of work others in the region are undertaking. Some claimed that CSR initiatives should address local issues with a standardized goal, with every entity doing their part and contributing to the overall picture. Most are hopeful that there is a positive future and that locals are showing positive signs towards a well-accepted CSR, as one expressed “The young guys are great at this – the young entrepreneurs…they build brands around sustainability, values (ex-organic) and really you see a fresh wave of thought…but the majority of the existing entities usually hold what is considered CSR events in a spontaneous kind of way…of course other than their legal obligations.” (S01)

Cultural Impact

On a cultural level, the people interviewed generally reiterated that much of the way that CSR is expressed in this part of the world was in alignment with societal expectations, which often stemmed from religious expectations. As one puts it, “In Kuwait it is not ok to only do random events here and there to show the world your CSR initiatives…locals expect a certain kind of commitment, such as giving back to society in Eid occasions and other religious holidays…the other stuff is considered fun activity for the community” (SO2) Due to the conservative nature of the locals, it is rather expected that companies would act accordingly particularly in a small country as some noted. In Kuwait, degrees of separation are rather small and word of mouth goes a long way. Some expressed that the important social aspect - reputation – is often embedded in the heart of business dealings, which are often amplified with the community activities of a company. One of the interviewees expressed “Our efforts to give back to the society is a way of life…it’s an extension of what we are and what we represent as individuals.” (SO3)

The reputation aspect was also expressed as a particular interest in getting the entire town (either physically or virtually through social media) talking about a company’s initiatives, especially on anything innovative or new. The interviewees insisted that this is a good thing as it encourages the older, more traditional/conservative shot callers to get on board with future initiatives. Once they see the reaction of their families and peers in informal settings, like ‘Diwaniyas’ or places of social gatherings, acknowledging and approving of their activities. As one interviewee puts it, “…word of mouth is definitely an important consideration, most campaigns we do hold that as one of the top signs of an effective campaign.” (SO1)

Moreover, interviewees felt that many businesses in the local arena prioritize social expectations through their CSR work by catering particularly to patriotic acts and adopting locally-trending issues in an entertaining way. As expressed, “I think every professional understands that they must have some kind of CSR element in their plan (somewhere!) but it’s not always a die-hard, carved in stone way…sometimes its hit or miss…I do not have the luxury of time for example to set up a community event based on certain national celebrations or religious holidays but I know that it is expected of me/my company (by the locals.” (SO7). It was also expressed by some that other aspects which are in line with religious duties are somewhat taboo to be announced as it is seen as improper culturally. Lastly, it was also noted amongst the interviewees that the reason companies are not always eager to participate in conventional CSR campaigns is because they believe that they have done so already in private, which may cause implication as one expressed as “To follow the western way of CSR is not exactly ideal either…we don’t have a problem with issued such as diversity for example, so we do not spend a lot of time on it…but if we are to go by international standards, we may be “failing” in addressing this but that is not true…it’s all relative and should be considered this way.” (SO7). Through the government-imposed tax on all listed companies in Kuwait, entities are forced to pay an annual 2% of their profits towards the local Beit Al Zakat – the official state-owned center for giving alms (locally and internationally) and the Kuwait Foundation for Advancement of Science (KFAS). Theoretically, these are considered the alms donations – the popular go to activity for showing social responsibility.

Moreover, most described CSR as a way of giving, but did not seem to have a rigid structure or strategy as to what this ‘giving’ entailed. Even when discussing and dissecting their own initiatives with the researcher, most had a tough time really pin pointing where each activity fit best under the conventional definitions of these terminologies. One expressed that “People react to fun activities, non-tedious events which they can be entertained in….giveaways are important, they are very impactful and give company stakeholders what they are aiming for….the brand logo is in your home, on your car shade, etc.” (SO5), which makes it tough to meet conventional expectations and local expectations at the same time as some aspects, may overlap. In terms of CR, most understood it as equal to CSR, with some expressing “isn’t it the same thing?” (SO7) and elaborating that most of their relevant activities would qualify also as corporate responsibility. Conversations then took a turn discussing whether or not all companies had official CR events/activities, if CR included mandated elements or simply voluntary ones, and how CR is being measured. Those in finance-related fields expressed that sometimes international restrictions applied through corporate governance such as transparency could apply as CR by default, that CR is not necessarily something which is outlined and strategically pre-determined as, say, a KPI. As for Citizenship and sustainability, though most understood the terminologies, there were differences observed in the way they have connected it to their workplace. For example, those who were in the government sector viewed it as the responsibility of the employees working in the sector, independent of the organization. In contrast, those who worked in the private sector stressed the importance of guidelines not only for those within the organization, but also the grand society at large. They were keen to mention that all stakeholders of society are an integral part of building a sustainable future by partaking in acts of responsibility, and that such initiatives should be initiated by those in society who are either in power and/or using resources more than others. Also, as the conversation flowed, most realized that they could be doing more, but that in order to be effective, more communication and initiatives are needed throughout the country.

As for which terminology they would rather use, Corporate Citizenship came out on top as most confirmed that, due to their own understanding as well as realizing their own initiatives by talking to me about it, would fit best under this umbrella. The second most frequent answer to this question was Corporate Responsibility, which many expressed was the ‘ideal’ answer as per their conventional knowledge of the subject, but in reality this may not be the case.

Barriers and Motivation to CSR

Motivations

It was clear that the people interviewed collectively agreed that CSR is not a foreign concept to locals, as highlighted in the quotation below. This might be due to the fact that the majority are world travels who are highly exposed to (and oftentimes took part in) conventional CSR activities such as recycling and power saving. As one expressed, “We all get it, we have been a part of it at some point.” (SO4) (About environmental aspect of CSR). But they are conflicted as to why CSR initiatives are frequently overlooked in terms of importance by most stakeholders of society – particularly due to recent negative indicators including corruption, drug use, and economic outlook. Some speculated that his is due to the lack of awareness and participation of social responsibility from a young age, while others said that entities simply did not see the need for it as locals were not particularly interested in such initiatives. One expresses that “Maybe the community does not fully understand the importance of some CSR aspects, but the bigger problem is that they do not understand to what degree they are contributing to some of the negative indices within the society.” (SO12) Others stated that most of the time, conventional CSR initiatives fail simply because locals do not see a need for them, unless a religious aspect is highlight as one expresses - “Once you mention the word ‘religion’ or that an activity you are hosting is of a religious nature …there are many of them… then everyone is willing to take part…some more openly than others.” (SO4).

Moreover, the private sector representative expressed that CSR is a powerful tool as it allows them to enter international indices and show foreign investors what it’s like to do business in Kuwait. However, on a local level of implementation in relation to the local level of understanding, conventional CSR is not considered a powerful tool as it has limited impact on the society. Some even expressed that some initiatives, particularly economic and social ones, may possibly impact the brand negatively as societal norms may be influenced which could put a brand under some major scrutiny. One explains that “Meeting societal expectations and meeting the expectations of important people in our life is very important to us, it is a staple of the Arab society…naturally it would be an important thing to consider in our professional lives as well. We are a small country, we are all connected.” (SO11)

Barriers

Some expressed the need to open discussions about the real expectations of CSR, that it is always expected as a one-way deal where there is no real advantages for the giving company. As one puts it, “It is like a riddle…we practice CSR from one standpoint, but we turn a blind eye to other elements of it…we know it’s important, but somehow we create awareness and get more heavily involved in initiatives which resonate most with the community…environmental initiatives are not always popular maybe because they are not mandated?” (SO5) However, they insist that these elements are important to address and to be honest that there is a real expectation from decision makers especially due to the age gap which makes communicating and aligning priorities difficult. The truth of the matter is, as expressed by several persons, that CSR should be considered a two-way street with observable short & long-term effects in order to push the agenda of the campaigns and prove their impact and thus their importance. One of the interviewees said “We rarely discuss it (CSR)…we rarely consider the long-term effects of the impact which the lack of a holistic CSR approach can have on our society…it’s important to have these conversations.” (SO1).

All those interviewed suggested that everyone needs to do their part, especially those in power. As another expressed, “I mean, it’s so ambiguous and everybody is doing their own thing…not much communication going on or even conversations or awareness…” (SO8). They also felt that we can do a lot more in terms of education the future generations to take part in CSR initiatives, and that the importance of having them in place needs to be stressed upon. In an ideal world, all stakeholders in the community would be doing their part with rewards and punishment in place to incentivize the initiatives, particularly the government as one expressed “The government totally needs to be involved and supportive, it cannot be done without their support…just like they impose the religious aspect of giving, they should also be stressing other important dimensions and even penalizing those who do not participate…it’s not fair that for example some companies pollute more than others and they do nothing to compensate the society.” (SO11) Some even suggested that an ideal CSR would involve equally conventional elements such as environmental initiatives as well as social initiatives such as the ones currently being done.

Research Questions

From the findings above, it can be concluded that CSR in its conventional sense understood in the Arab world, but may be evident and practiced in a different context based on the local culture and expectations which was the objective of the first research questions. This obviously has some implications on the topic of what terminology better explains how CSR is expressed in the Arab context, as the pilot study reveals that the locals view it as more of a compulsory service to the community as per their religious teachings. This emerged theme which answered the second research questions set the research towards a new tangent, one which includes the investigation of religion as an individualistic aspect of culture which needs further attention. As for the third question, culture seems to impact the theories and practices of CSR in the Arab context quite heavily, and though there are plenty of barriers there, the locals are also hopeful of a brighter future.

Discussion & Conclusion

The research suggests that religion was being most significant cultural aspect influencing the expression of CSR in Kuwait. A key concern was therefore how CSR could be linked to and expressed in line with the Islamic religion. This contrasts with western practices of CSR, which are often linked to increasing business performance, corporate reputation, customer loyalty or reducing risk. The study supports theorists who suggest that Arab world is likely to have different individual, institutional and socio- drivers of CSR activities and that Islamic religion is likely to have play an integral part in the relationship between business and society (Koleva, 2021).

Another finding was that conventional CSR initiatives are engaged in Kuwait, mainly due to obligations imposed by the West – the more international presence a company has, the more it was likely to initiate traditional CSR activities. This is in line with the findings of Ismaeel, et al., (2020), who found that CSR in developing countries is expressed primarily to impress international stakeholders. Also, recent findings from Koleva (2021), confirm that most local initiatives which fit under the CSR umbrella are not entirely built into corporate strategy.

Also, the research identified obstacles to implementing CSR locally in a successful way such as the lack of synchronization between NGO’s, government, and other stakeholders, which confirms Al-Abdin, et al., (2018) work which identifies gaps of relationships between stakeholders identified in the CSR literature. Lastly, since the pilot study revealed that religious beliefs are expressed as the primary strategies underpinning CSR initiatives in Kuwait, a few key observations remain puzzling. Firstly, when investigating how the professionals understood CSR, the results varied from one person to another. This is interesting, because participants generally agreed that religion is at the heart of their CSR strategies – thus leading to the conclusion that the same stimuli (religious duty) led to varied outcomes from individuals, both within and across demographic profiles, similar to findings observed by Bhattacharya & Sen (2004); Walker (2010); West, et al., (2016). It was clear that one main subset of culture seemed to be religion, that played a dominant role. Since scholars describe religion as a cultural system which naturalizes conceptions of a general order of existence, religion is considered a part of culture and experiencing spirituality that is inward, personal, and subjective. In other words, cultural values are seen as a foundation to religiosity (Edara, 2017).

References

Aikaterini, G., & Schwartz, S.H. (2009). Quod erat demonstrandum: From Herodotus’ ethnographic journeys to cross-cultural research. Pedio Books.

Ajiferuke, M., & Boddewyn, J. (1970). Culture and other explanatory variables in comparative management studies.Academy of Management Journal, 13(2), 153-163.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Alfakhri, Y., Nurunnabi, M., & Alfakhri, D. (2018). Young Saudi consumers and corporate social responsibility: an Islamic “CSR tree” model.International Journal of Social Economics.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Ali, A.J., & Camp, R.C. (1995). Teaching management in the Arab world: Confronting illusions.International Journal of Educational Management, 9(2), 10-17.

Ali, A.J., & Wahabi, R. (1995). Managerial value systems in Morocco.International Studies of Management & Organization, 25(3), 87-96.

Ali, A., (1995). Cultural discontinuity and Arab management thought.International Studies of Management and Organization, 25(3), 7-30.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Alqabas newspaper, (2021). https://alqabas.com/article/5869158 accessed on November 22, 2021.

Al-Rasheed, A., (1997). Factors affecting managers’ motivation and job satisfaction: The case of Jordanian bank managers.Middle East Business Review, 2(1), 112-117.

Arthaud-Day, M.L. (2006). A changing of the guard: Executive and director turnover following corporate financial restatements.Academy of Management Journal, 49, 1119-1136.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Atiyyah, H.S. (1996). Expatriate acculturation in Arab gulf countries.Journal of Management Development, 37-47.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Baric, A. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and stakeholders: Review of the last decade (2006–2015).Business Systems Research Journal, 8(1), 133–146.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Bhattacharya, C.B., & Sen, S. (2004). Doing better at doing good: When, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives.California management review, 47(1), 9-24.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Bitran, G.R.G.S.S.S.L. (2006). Emerging trends in supply chain governance. MIT Sloan School of Management, 1-31.

Boulouta, I., & Pitelis, C.N. (2013). Who needs CSR? the impact of corporate social responsibility on national competitiveness.Journal of Business Ethics, 119(3), 349–364.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Boyd, R., & Richerson, P.J. (2009). Culture and the evolution of human cooperation.Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1533), 3281-3288.

Butt, I., Mukerji, B., & Uddin, M.H. (2019). The effect of corporate social responsibility in the environment of high religiosity: An empirical study of young consumers.Social Responsibility Journal.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Proquest

Cassel, M.A., & Blake, R.J. (2011). Analysis of hofstede’s 5-d model: The implications of conducting business in Saudi Arabia.The 2011 New Orleans International Academic Conference.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Chan, Y.Y., Cheng, S.Y., Chia, K.H., Chong, P.Y., & Kuang, B.N. (2013). The effect of national culture on corporate social responsibility orientation: A comparison between Malaysian and Singaporean accounting students. (Doctoral dissertation, UTAR).

Chatjuthamard-Kitsabunnarat, P., Jiraporn, P., & Tong, S. (2014). Does religious piety inspire corporate social responsibility (CSR)? Evidence from historical religious identification.Applied Economics Letters, 21(16), 1128-1133.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Chhokar, E.A., (2008). Culture and leadership across the world. In: The globe book of in depth studies of 25 societies. London: Publisher Taylor & Francis Group.

Chiang, F. (2005). A critical examination of Hofstede's thesis and its application to international reward management.International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(9), 1545-1563.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

CIMA. (2007). Corporate reputation: Perspectives of measuring and managing principal risk. CIMA.

Costa, P.T., & McCrae, R.R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual. FL: Odessa.

Culture. (2003). Culture definition. Tamu.edu

Cunningham, R., & Sarayrah, Y. (1993). Wasta: The hidden force in middle eastern society. Westport, CT: Praegar.

Czechkid. (2021). CzechKid : Culture and cultural differences. Czechkid.eu.

Dadfar, H. (1984). Organization as a mirror for reflection of national culture: A study of organizational characteristics in Islamic nations. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Organization Symbolism and Corporate Culture.

Davies, G., Chun, R., Silva, R.V., & Roper, S. (2003). Corporate reputation and competitiveness. Psychology Press.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Davila, A. (2017). From silent to salient stakeholders: A study of a coffee cooperative and the dynamic of social relationships.Business & Society, 56(8).

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Dedoussis, E. (2004). A cross-cultural comparison of organizational culture: Evidence from universities in the Arab world and Japan.Cross Cultural Management, 11(1), 15-34.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Dimensions of national culture. (2015). Hofstede’s Five dimensions of national culture. Open Textbooks for Hong Kong.

Edara, I.R. (2017). Religion: A subset of culture and an expression of spirituality. Advances in Anthropology, 7(04), 273.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Fisher, V.E., Mahoney, L.S., & Scazzero, J. (2016). An international comparison of corporate social responsibility.Issues in Social and Environmental Accounting, 10(1), 1-17.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Friedman, A.L., & Miles, S. (2002). Developing stakeholder theory.Journal of management studies, 39(1), 1-21.

Garcia-Torea, N., Fernandez-Feijoo, B., & Cuesta, M.L., (2016). Board of director's effectiveness and the stakeholder perspective of corporate governance: Do effective boards promote the interests of shareholders and stakeholders?BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 19(4).

Geertz, C. (Ed.). (1972). Myth, symbol, and culture. Norton.

Ghobadian, A., Money, K., & Hillenbrand, C. (2015). Corporate responsibility research: Past – present – future.Group & Organization Management, 40(3), 271-294.

Giada Martino, R.I. (2017). Fashion retailing: A framework for supply chain optimization.Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 5, 243-272.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Glavas, A. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and organizational psychology: An integrative review. Frontiers in Psychology, 7.

Gregg, P.M., & Banks, A.S., (1965). Dimensions of political systems: Factor analysis of a cross-polity survey.American Political Science Review, 59, 602-614.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Groeschl, S., & Doherty, L., (2000). Conceptualising culture.Cross Cultural Management, 7(4), 12-17.

Hafeez, G.A. (2016). Cultural diversity in Middle East.

Hamidu, A.A., Haron, M.H., & Amran, A. (2018). Profit motive, stakeholder needs and economic dimension of corporate social responsibility: Analysis on the moderating role of religiosity.Indonesian Journal of Sustainability Accounting and Management, 2(1), 1-14.

Harjoto, M.A., & Rossi, F. (2019). Religiosity, female directors, and corporate social responsibility for Italian listed companies.Journal of Business Research, 95, 338-346.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Herold, D.M., (2018). Demystifying the link between institutional theory and stakeholder theory in sustainability reporting. Economics, Management and Sustainability, 3(2), 6-19.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Herskovits, M.J. (1955). Cultural anthropology.

Hillenbrand, C., & Money, K. (2007). Corporate responsibility and corporate reputation: Two separate concepts or two sides of the same coin?Corporate Reputation Review, 10(4), 261–277.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Hillenbrand, C., Money, K.G., Brooks, C., & Tovstiga, N., (2019). Corporate tax: What do stakeholders expect?.Journal of Business Ethics, 158, 403-426.

Hofstede, G., & McCrae, R.R. (2004). Culture and personality revisited: Linking traits and dimensions of culture. Cross-Cultural Research, 38, 52-88.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage Publications. (Original work published 2021)

Hofstede, G. (2019). Hofstede’s cultural framework – Principles of management. Opentextbc.ca; Sage Publishers.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1998). Organizing for cultural diversity.European Management Journal, 7(4), 390-396.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context.OnlineReadings in Psychology and Culture, 1-26.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., & Minkov, M. (2015). Cultures and organizations: Pyramids, machines, markets, and families: organizing across nations. Classics of Organization Theory, 314(23), 701-704.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., & Minkov, M. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (Vol. 2). New York: Mcgraw-hill.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Hofstede, G., Neuijen, B., Ohavy, D.D. & Sanders, G. (1990). Measuring organizational cultures: A qualitative and quantitative study across twenty cases. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(2), 286-316.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Hofstede. (2017). Kuwait*-Hofstede Insights. Hofstede Insights

Hunjra, A.I., Boubaker, S., Arunachalam, M., & Mehmood, A. (2021). How does CSR mediate the relationship between culture, religiosity and firm performance?.Finance Research Letters,39, 101587.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Hur, W.M., & Kim, Y. (2017). How does culture improve consumer engagement in CSR initiatives? The mediating role of motivational attributions.Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 24(6), 620-633.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Inkeles, A., & Levinson, D.J. (1969). National character: The study of modal personality and sociocultural systems. In: The Handbook of Social Psychology IV. G. Lindzey & E. Aronson ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 418-506.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Jafari, H.A., Pirmaleki, P., & Najafabadi, M.K. (2020). Influence of Piety (Taqwa) on ethical decision-makings in business: Integration of religious and scientific views. In Handbook of Ethics of Islamic Economics and Finance (pp. 410-438). De Gruyter Oldenbourg.

Jamali, D., & Sdiani, Y. (2013). Does religiosity determine affinities to CSR?Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 10(4), 309-323.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Kavoossi, M., (2000). The globalization of business and the Middle East: Opportunities and constraints. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Khanum, M.A., Fatima, S., & Chaurasia, M.A. (2012). Arabic interface analysis based on cultural markers.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Khushman, S., Todman, A., & Amin, S. (2009). The relationship between culture and e-business acceptance in arab countries. Second International Conference on Developments in eSystems Engineering (DESE), 454-459.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Kirkman, B.L., Lowe, K.B., & Gibson, C.B. (2006). A quarter century of culture’s consequences: A review of empirical research incorporating Hofstede’s cultural values framework. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 285-320.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Koleva, P. (2021). Towards the development of an empirical model for Islamic corporate social responsibility: Evidence from the Middle East. Journal of Business Ethics, 171(4), 789-813.

Lamb, D., (1987). The Arabs. New York: Random House.

Lynn, R. & Hampson, S. L., (1975). National differences in extraversion and neuroticism. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 14, 223-240.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

MacMillan, K., Money, K., & Downing, S., (2005). Reputation in relationships: Measuring experiences, emotions and behaviors.Corporate Reputation Review, 8(3), 214-232.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Macmillan, K., Money, K., Downing, S., & Hillenbrand, C. (2004). Giving your organisation SPIRIT: an overview and call to action for directors on issues of corporate governance, corporate reputation and corporate responsibility.Journal of General Management, 30(2), 15–42.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Maignan, I., & Ralston, D.A., (2002). Corporate social responsibility in Europe and the U.S.: Insights from businesses' self-presentations.Journal of International Business Studies, 33, 497-514.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Marton, F. (1992). Phenomenography and “the art of teaching all things to all men'’.Qualitative studies in education, 5(3), 253-267.

Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2008). “Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility.Academy of management Review, 33(2), 404-424.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Matthiesen, M.L., & Salzmann, A.J. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and firms’ cost of equity: how does culture matter?.Cross Cultural & Strategic Management.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Mayer, F.P.J. (2010). Re-embedding governance: global apparel value chains and decent work. Capturing the Gains, economic and social upgrading in global production networks.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

McSweeney, B., (2002). Hofstede’s model of national cultural differences and their consequences: A triumph of faith – a failure of analysis.Human Relations, 55, 89-118.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Naeem, M., & Khurram, S. (2019). Does a CEO’s national culture affect corporate social responsibility?.Journal of Managerial Sciences,13(3).

Najm, N.A., (2015). Arab culture dimensions in the international and Arab models. American Journal of Business, Economics and Management, 3(6), 423-431.

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M. & Kemmelmeier, M., (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3-72.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Prinz, J. (2011). Culture and cognitive science (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Stanford.edu.

Randon, E. (2012). Corporate social responsibility, the role of stakeholders and the information gap MSc Thesis.

Ray, C.C. (2008). A cross-cultural comparison of corporate social responsibility practices: America and China (pp. 1–79) Master Thesis.

Ray, C.C. (2008). A cross-cultural comparison of corporate social responsibility practices: America and China.

Ringov, D., & Zollo, M., (2007). The impact of national culture on corporate social performance. Corporate Governance International Journal of Business in Society, 7(4), 476-485.

Ryle, R. (2011). Questioning gender: A sociological exploration. Sage Publications.

Sachs, S., Maurer, M., Rühli, E., & Hoffmann, R. (2006). Corporate social responsibility from a stakeholder view perspective: CSR implementation by a swiss mobile telecommunications provider.Corporate Governance, 6, 506-515.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Samer Al Ahmadieh & Abdullah Alnabhan (2019) “How Kuwait can Transform its Education to Meet its Economy's Demands”.

Schmidt, M.A. (2017). Does religiousness influence the corporate social responsibility orientation in Germany?. In Corporate Social Responsibility in the Post-Financial Crisis Era (pp. 25-39). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Sidani, Y.M., & Gardner, W.L., (2000). Work values among Lebanese workers.Journal of Social Psychology, 140(5), 597-607.

Sims, R.L. & Keon, T.L., (1997). Ethical work climate as a factor in the development of person-organization fit.Journal of Business Ethics, 16, 1095-1105.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Smith, N.C. (2003). Corporate social responsibility: Whether or how?. California Management Review, 45, 52-76.

Sondergaard, M. (1994). Research note: Hofstede's consequences: A study of reviews, citations and replications.Organization Studies, 15(3), 447-456.

Spence, M.B., & Brown, L.W. (2018). Theology and corporate environmental responsibility: A biblical literalism approach to creation care. Journal of Biblical Integration in Business, 21(1).

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Stohl, M., Stohl, C., & Townsley, N., (2007). A new generation of global corporate social responsibility. In: The Debates Over Corporate Social Responsiblity. S. May, G. Cheney & J. Roper ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 30-44.

Sukhdeo, B.L. (2020). Social axioms as antecedents of corporate reputation in South African banking (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria).

Tang, L., Li, H., & Lee, Y. (2008). Corporate social responsibility in the context of globalization: An analysis of CSR self-presentation of Chinese and global corporations in China. San Diego, s.n.

Tokoro, N. (2007). Stakeholders and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): A new perspective on the structure of relationships. Asian Business & Management, Volume 6, pp. 143-162.

Crossref, GoogleScholar, Indexed at

Torstrick, R.L., & Faier, E. (2020). Culture and customs of the Arab Gulf States. Products.abc-Clio.com.

Triandis, H. C. (2004). The many dimensions of culture. Academy of Management Executive, 18, 88-93.

United Nations Industrial Development Organisation. (2017). What is CSR? | UNIDO. Unido.org.