Research Article: 2024 Vol: 27 Issue: 1

CONTEXTUAL AND CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS OF THE VENEZUELAN MIGRATORY PANORAMA IN THE CITY OF SAN JOS?? DE C??CUTA

Luz Karime Coronel Arquitecta, Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander

Erika Tatiana Ayala Architect, Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander

Eduardo Gabriel Osorio, Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander

Citation Information: Arquitecta, L.K.C., Ayala Architect, A.E.T., & Osorio, E.G. (2024). Contextual and conceptual analysis of the venezuelan migratory panorama in the city of san josé de cúcuta. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 27(1), 1-12.

Abstract

The objective of this research is to recognize the relevance of the Venezuelan international migratory phenomenon for the city of San José de Cúcuta as a Colombian-Venezuelan border zone based on the analysis of the normative and historical component and its relationship with urban growth and territorial configuration. A qualitative approach methodology was used, from a deductive, exploratory and sequential method through a bibliographic or documentary source of data collection and from study categories such as International Migration and Border. As relevant findings, it is highlighted that the city of San José de Cúcuta and its Metropolitan Area present weaknesses regarding the support of an infrastructure that allows guaranteeing the control and adequate treatment of the migratory phenomenon and, it is concluded the importance that the national migratory policy contemplates specific aspects for border areas, as well as the generation of instruments that favor the articulation of governmental entities, international and national cooperation agencies, the private sector and the civil society; to promote the regularization and integration of migrants to the context of the host territory.

Introduction

This article addresses the phenomenon of migration under the recognition of the relevance it has on the global scale, and the high impact it represents both for the population that moves and for the territories that host it. In this sense, the research groups TARGET and JHUSDEM of the Universidad Francisco de Paula Santander, through their research lines "Urban and territorial management" and "The force of social facts and the transformation of Human Rights" give a pertinent response to the geographical context and the problems of the city of San José de Cucuta as a border area.

The above makes sense when taking into account what is pointed out by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean ECLAC, 2018 for whom international migration developed in and from the regions, presents a series of particularities, causes and effects that bring clear determinants for each of the actors (migrants-host territory). For this reason, addressing the migration phenomenon from the specificity of each case (territory) is relevant and pertinent, as it favors its understanding and allows determining the opportunities, limitations and effects that can be generated for the receiving societies and for the population seeking to improve their living conditions and expectations (Mayo, 2015).

Within this article, relevant aspects are condensed with respect to the international migratory phenomenon focused on the city of San José de Cucuta as a border territory with the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, developed from sections associated with: (1) Concept and particularities; whereby a conceptual framework is established and the regulations corresponding to the migratory phenomenon that allows establishing types, characteristics and rules that are part of the international context, as well as those referring to the Colombian one; (2) History and configuration of the territory, where it is described how migration has been present throughout the history and territorial configuration of San José de Cúcuta, in addition to making a deductive, exploratory and sequential account in which the different periods and relevant events with respect to the Venezuelan international migration phenomenon for the Colombian-Venezuelan border can be evidenced; and finally, (3) Migration in a border territory in which the problems associated with the lack of control and urban planning of the host territory are addressed, resulting in socio-urban and socio-economic effects (Colombian Migration, 2016).

Method

The methodological framework of this research corresponds to a qualitative approach, which allowed recognizing, analyzing and interpreting data (Hamui-Sutton, 2013), through a descriptive process that favored the understanding of the migration phenomenon (Hernandez et al., 2014). It was developed from a deductive, exploratory and sequential method Canese et al. (2021) taking into account that a discussion was developed from the observation and analysis of the history and the different periods of the phenomenon of Venezuelan international migration in the city of San José de Cucuta and its Metropolitan Area, favoring the understanding of the phenomenon of migration as an urban fact, as well as the territorial reality of a border area.

The source of data collection is bibliographic or documentary Gomez (2011) through which information was collected and analyzed, allowing the understanding of the particularities of the migratory phenomenon and the relevant facts from the historical scope in the configuration of the Colombian border territory. This was done through the implementation of the content analysis technique, systematization, selection and analysis of resources based on study categories such as International Migration and Border. The collection of information was based on sources from official documents of national and international authorities and organizations and institutions such as support programs for migrant groups, as well as bibliographic databases such as Redalyc, Scopus, and Mendeley, among others.

Results and Discussion

Concepts and Particularities of Migration

The definition of migrant has not had a clear concept in either international or Colombian law. However, human rights protection bodies have been using a term that allows for a standardized definition to address issues related to migration. In this sense, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (hereinafter IACHR) has been using terminology in its work, through the Rapporteurship on the Rights of Migrant Persons, understanding International Migrant as "any person who is outside the State of which he/she is a national" and Internal Migrant as "any person who is within the territory of which he/she is a national, but outside the place where he/she was born or where he/she usually resides" (Presidency of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 2015a).

Within the concept of International Migrant (defined more broadly) can be found people who enter a State of which they are not nationals to carry out various activities, professional, educational, trade, business, and tourism, among others. This entry may be made through the country's Migration Control Posts - hereinafter referred to as PCMs - in compliance with the time limits established by Colombian law for the type of activity to be carried out and then leave the national territory, or it may be made without passing through the PCMs, without complying with Colombian regulations for the entry of foreigners into the territory or even entering through the PCMs, without complying with the time limits established by law for being in the national territory. The first group of people is referred to as Migrants in a regular situation and the second, Migrants in an irregular situation (Presidency of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 2015b).

It is important to highlight that the IACHR recommends to the OAS States Parties that when referring to Migrants in an irregular situation, these persons should not be referred to as Illegal Migrants, as this denomination reinforces the idea that the Migrant is a criminal and therefore, their criminalization (Presidency of the Republic of Colombia, 2015). Indeed, the UN Committee on Migrant Workers has pointed out in its General Comment No. 2 of 2013 that criminalizing irregular migration entails considering migrant workers and their families as illegal, second-class people, which ends up translating into feelings of discrimination and xenophobia in the recipient population Committee on Migrant Workers, 2013.

These people who can be considered as International Migrants, whether they are in a regular or irregular situation, depending on the type of activities they will perform in the State they enter (and of which they are not nationals), may have a vocation to stay in the country; the interest to enter for a short time (hours or days) or use the national territory to move to a third country.

In the first case, Law 2136 establishes that in Colombia a Migrant with a vocation of permanence is recognized, as long as the person who enters the country has the intention to remain regularly, that is, under the regulations for the entry of foreigners, and to perform lawful activities, which is a legal provision that ignores the vocation of permanence of a significant number of migrants who irregularly enter the territory, but who still have the vocation of permanence to perform various activities not prohibited by law.

In this regard, the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, approved by Colombian Congress of Colombia (1943) establishes that a Migrant Worker (regardless of his regular or irregular status) is considered any person who "will perform, performs or has performed a remunerated activity in a State of which he is not a national".

Regarding migrants who enter the country for a short time, Law 2136, recognizes the Pendular Migrant as a person who enters the country for days or hours with the purpose of "obtaining provisions, necessities, visiting relatives or carrying out other activities in the municipalities of entry to the country". The law states that persons who carry out pendular migration do not have a vocation of permanence.

For its part, regarding the third case of migration, CONPES 3950 points out that it is Transit Migration. Regarding this type of Migracion Colombia (2017) issued by the Special Administrative Unit Migration Colombia (2018) here in after Migration Colombia- stipulates that the International Migrant who enters the country in a regular situation can request the Temporary Transit Entry and Stay Permit (PIP-TT), which is intended for migrants who enter the country with the purpose of "transiting within the national territory, to make connections or stops to board any means of transportation, whether by sea, land, air or river, to return to their country of origin or a third country, without the intention of settling or domiciling in Colombia".

In addition to the above, there is another type of migration that is associated with the will or not of persons to migrate to a certain country of which they are not nationals. This is the so-called Forced Migration that could characterize the movement of refugees at the international level and forced displacement when migration is internal (Comision Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 2015).

As can be seen from the international and national regulations, the characteristics of the conditions of the people who can be considered Migrants, obey different situations associated with the motivations or causes of their departure from the country of origin to the country of destination (better working conditions, living conditions, security, among others), the object sought in the territory of the State of which is not a national (work, tourism, transit, acquisition of goods and services, protection, among others) and the situation of regularity or irregularity according to the laws of the State where they enter (Colombian Migration, 2020).

In this sense, as Sierra et al. (2020) point out, the causes of migration are diverse, multiple and interrelated (Abu-Warda, 2008). Within these diverse causes, the authors highlight how they may be associated with social phenomena, which, as pointed out by Gomez (2010a), may be related in turn to situations "of a political, economic, labor, cultural, educational and religious nature, among others, and/or natural".

In the Latin American region, the phenomena that have been leading to migration have been diverse and have been associated with multiple circumstances that place people in a situation of manifest weakness and, as noted by the Presidency of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (2015b) are factors that have been increasing, such as:

1) the growing socio-economic disparities, particularly in terms of inequality, poverty and unsatisfied basic needs; 2) the rise of flexibilization and reduction of labor guarantees and rights, mainly for workers in low-skilled economic sectors; 3) the increase in criminal violence in some countries of the continent and the consequent progressive deterioration in the levels of human security; 4) the deterioration of the economic, social and political situation in various countries; 5) the impact generated by violence in response to wars, armed conflicts, and terrorism; 6) the fragility and/or corruption of political institutions in some countries of the region; 7) the need for family reunification; 8) the impact of the actions of national and transnational companies; 9) climate change and natural disasters, and 10) the boom in urbanization due to improved living conditions in cities (National university of Colombia, 2021).

This type of migratory phenomenon has materialized for Colombia as well as for other Latin American and Caribbean countries, in the massive migration of the Venezuelan population which, as pointed out by the Committee of Migrant Workers 2020 has meant that by June 30, 2019, around 4 million migrants have entered Colombia, of which 1.4 million ended up settling in Colombian territory. The above, added to the transit migration in the country and the pendular migration that would represent for 2019, 40 thousand people per day entering and leaving Colombia through border crossings.

This migration can be explained by the deep economic problems experienced in the Venezuelan country, the shortage of basic goods and medicines, the deterioration of the health system and its political instability all added to what the IACHR has called a generalized humanitarian crisis Presidency of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (2015a), which in recent years received the effects derived from the Covid-19 pandemic (Presidency of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, 2015b). In this context, it is the Colombian State, due to its geographical location, which "as a country of origin, transit, destination and return (...) faces an unprecedented situation, due to massive migratory movements" United Nations (2019), a situation that has had particularly important effects on the city of Cucuta, which historically shares a flow of people entering and leaving from and to Venezuela, with three formal border crossings and countless informal crossings that are used daily by Colombian and Venezuelan people for their transit between the two countries.

History and Configuration of the Territory

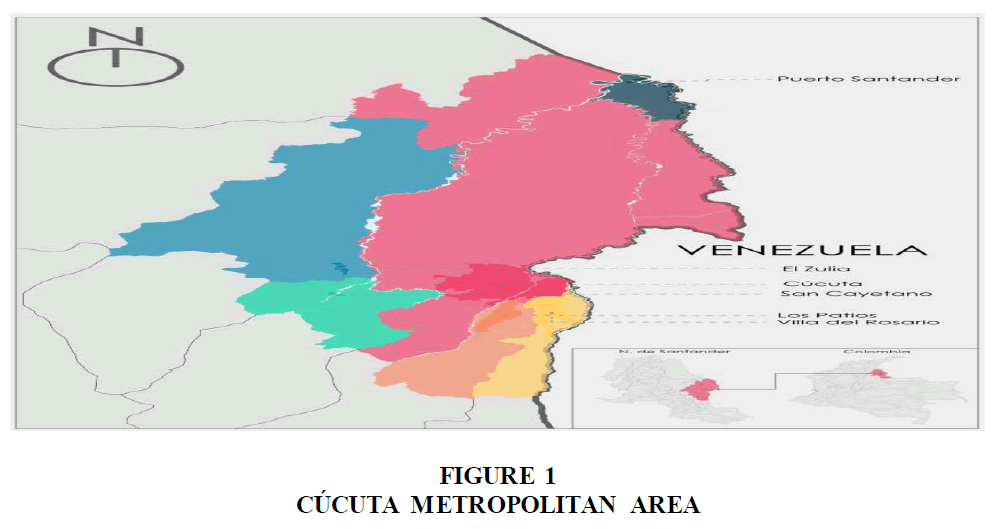

The city of San Jose de Cucuta is located in the central-eastern part of the department of Norte de Santander, Colombia. Its geographical boundaries are comprised of the municipalities of Tibu, el Zulia, San Cayetano, Bochalema, Los Patios, Puerto Santander and the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, it has an area of 1,176 km2 Ayala & Coronel, 2019 and a projected population of 777,106 inhabitants by 2020 according to data from the National Census of population and housing (National Administrative Department of Statistics, 2018).

Historically, its growth and urban configuration were the results of the sum of economic and social factors, which projected the city as an articulating node focused on the production of cocoa and coffee, and the improvement of road and rail infrastructure Melendez, 1982, Urdanet, (1988), as well as the various processes of national migration. These are the result of human mobility between urban centers and rural areas in the region of Norte de Santander, and international migration due to the arrival of foreigners from countries such as Italy and Germany, among others. Likewise, within this context, the important flow of commercial exchange stands out, taking into account its geographic positioning as a border zone with the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (Labrador, 2017).

For Febres (1926), the earthquake of San José de Cucuta in 1875 determined important aspects concerning the configuration of the territory, taking into account that from that moment on, human mobility, population growth and economic activity suffered a stagnation that impacted the economy, suffered a stagnation that impacted not only San Jose de Cucuta, but also territories such as Villa del Rosario and Pamplona and other areas of the region of Norte de Santander in the national context, and San Antonio del Tachira and San Cristobal in the Venezuelan territory due to its border location. However, the earthquake also presented an opportunity for the total reconstruction of the territory through the implementation of a hypodamic plan or checkerboard layout that favored its positioning as the urban nucleus of Norte de Santander.

Within this process, migration was configured as a determining factor considering that foreign residents of the city of San José de Cucuta of Italian, French, Lebanese, German and Arab nationalities economically supported the reconstruction of the city in anticipation of the coming boom times and the development of land productivity in Norte de Santander (Angel, 1990). This, added to the relaxation of the migratory regulations from which the Colombian government promoted the arrival of foreigners to the national territory. In the case of the Germans, it should be noted that their first approaches to the city corresponded to an educational labor profile, which later increased due to the interest in the wealth of the land, in addition to its geographical position that favored the river transport of goods (late XIX-XX), which promoted commercial activity, transportation infrastructure and the improvement of the physical characteristics of the city in the post-earthquake period, where the Germans acted as donors.

It should also be noted that during the XX-XXI centuries, the international migratory flow (Colombian-Venezuelan) determined significant changes for San Jose de Cucuta concerning the territory, taking into account that human mobility promoted the strengthening of infrastructure and the consolidation of conurbation processes close to the areas of Villa de Rosario (Colombia) and San Antonio del Tachira and Ureña (Venezuela) (Mercado, 2010). However, these processes developed mostly under non-formal characteristics that determined for the Colombian border zone changes in the landscape and territorial dynamics associated with the informal appropriation of land, being the relationship between the migratory phenomenon and the informality of land one of the main concerns for the planning and control of the territory.

Migration in the Colombian-Venezuelan Border Territory

To understand the urban growth and territorial configuration of the city of San José de Cúcuta under the previously described optics, this article must highlight that in 1991 the Metropolitan Area of Cucuta AMC was created by Ordinance number 40 of January 3, 1991, put into operation by Decree 508 1991, the AMC is integrated by the municipalities of Villa del Rosario, Los Patios, El Zulia, San Cayetano and Puerto Santander; San Jose de Cucuta being its articulating node Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2021. According to the Integral Metropolitan Development Plan PIDM (2017-2018), its extension represents 9.6% of the territory of Norte de Santander with 2,045 km2 and "thus gathering close to two-thirds of the total population of the department of Norte de Santander in only six of the Municipalities of the forty that comprise it and in less than 10% of its territorial extension" (Gomez, 2010b) Figure 1.

In this context, it is pertinent to remember that international migratory flows (Venezuelans) throughout history have permeated the Metropolitan Area of Cucuta since the geographic proximity between Colombia and Venezuela has generated processes of integration, dependence and tension in the economic, social, cultural, environmental and political-normative spheres, which has determined that migration is considered a metropolitan fact since it affects two or more municipalities of the Metropolitan Area of Cucuta Area Metropolitana de Cucuta, 2021.

Between the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the Colombian-Venezuelan border has seen an increase in migration due to events such as the continuous tension in the political relationship between governments, which has had an impact on the economy, security, peace and social stability of the territories.

In the same way, the application of the Border Regime Statute (1943-1970) which was intended to regulate population flows (border license) as well as issues associated with the environment, security and judicial cooperation Law 13, 1943, The Treaty of Treaty of Tonchala (1959) through which the border governments undertook to analyze issues related to transit, residence, workers, border permits, territorial delimitations and cooperation between border agencies (Gonzalez & Maldonado, 2015).

Also, the formulation of new bilateral trade rules, the formalization of the Tienditas crossing, within the framework of the projects of the Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America (IIRSA) between 2010-2012 (Sierra et al, 2020). Between the years 2013-2014, the border area went through a strengthening of the economy from currency fluctuation and foreign exchange impacting the economy of San José de Cucuta on a large scale, agreements were also carried out for the strengthening of security and increased controls on the sale of gasoline (Colombian Migration, 2020).

The years 2013- 2018 represented a new tension between governmental border relations associated with the Venezuelan internal crisis that brought as a consequence an increase in international human mobilities that defined San José de Cucuta as a receiving or transit city towards the interior of Colombia.

The year 2015 is considered a milestone in Colombian-Venezuelan history since the declaration of a State of Emergency issued by the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela through Decree 1950 where the Venezuelan government invoked the threat to the rights of the inhabitants of the Republic due to the presence of criminal and violent circumstances linked to "paramilitarism, drug trafficking and smuggling of extraction, organized at various scales, among other similar criminal behaviors" (Congress of the Republic of Colombia, 1994).

For its part, the Colombian government opted for the State of Emergency as of Decree 1770 (2015) "By which the State of Economic, Social and Ecological Emergency is declared in part of the national territory." Thus, the closure of the Colombian-Venezuelan land border began for a period of 72 hours, which was postponed for 60 days, with a temporary pedestrian opening (1 month) in 2016, and to date remains only with crosswalk enabled as of 2021 (See Table 1) (Linares, 2019).

| Table 1 Colombian-Venezuelan Regulations Border Closure | ||||

| COUNTRY | DATE | REGULATORY ACT | PURPOSE | |

| Venezuela | August 21st, 2015 | Decree 1950 | Declared a State of Emergency in the municipalities of Bolívar, Pedro María Ureña, Junín, Capacho Nuevo, Capacho Viejo and Rafael Urdaneta in the state of Táchira, bordering the department of Norte de Santander. | |

| It authorized personal requisitions, restrictions on the transit of goods and persons, the transfer of goods and belongings within the country, as well as the establishment of restrictions on the disposal, transfer, commercialization, distribution, storage or production of essential goods or basic necessities, "or regulations for their rationing, as well as to restrict or temporarily prohibit the exercise of certain commercial activities. | ||||

| September 1st, 2015 | Decree 1969 | The Venezuelan Government extended the State of Exception to the municipalities of Lobatera, García de Hevia, Ayacucho and Panamericana, also in the State of Táchira. | ||

| Colombia | September 7th, 2015 | Decree 1770 | Declares the State of Economic, Social and Ecological Emergency in part of the national territory. | |

In this sense, Venezuelan migration consolidated its impact on Colombian territory as of 2015, under the massive increase of human mobility initially corresponding to 10,780 people coming from Venezuelan territory (mobility that intensified over the months), according to sources of the National Unit for Disaster Risk Management of Colombia. This impact worsened with the Venezuelan internal crisis (political, economic and social) reported for 2017 affecting the territory again after the massive arrival of migrants to the border area (Migracion Colombia, 2017).

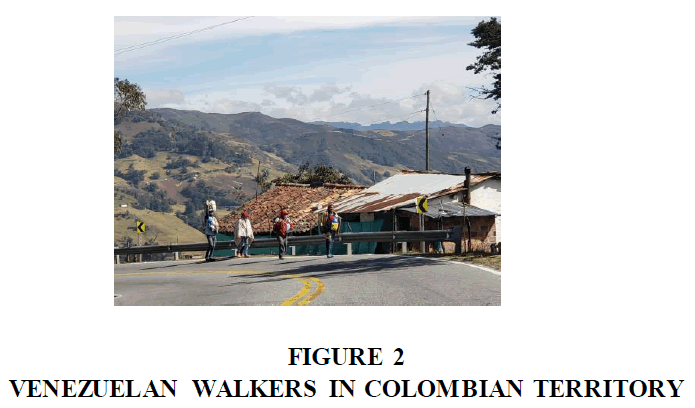

"We did not imagine that behind all this came a tremendous migratory flow. We began to realize it in January 2017, when we noticed that large groups of Venezuelans were seen on foot along the roads," recalls Victor Bautista, who specifies that they registered up to 800 walkers in one day along the border of Norte de Santander" (Palomares, 2020) Figure 2.

The massive arrival of Venezuelan migrants to the Colombian-Venezuelan border increased considerably in the year 2018, taking into account that the entry of Venezuelan foreigners corresponded to 1,359. 815, is the largest flow of migrants with entry to the country for this period (33%) (Migracion Colombia, 2019), followed by the year 2020 for which it was estimated that 1,729,537 Venezuelans arrived in the national territory through the Colombian-Venezuelan border, of which 762,823 regularly made their entry and 966,714 in an irregular manner (Migracion Colombia, 2019). The sanitary emergency due to Covid-19 deepened the migratory flow of Venezuelans into Colombian territory (see data for 2020). In 2021, according to the Interagency Group on Mixed Migratory Flows 2021 GIFMM, 2021, 1,742,927 Venezuelans entered Colombia (10.7% in Norte de Santander), of which 56.4% entered irregularly and 43.6% entered regularly (Migracion Colombia, 2019) Table 2.

| Table 2 Venezuelan Human Mobility in Colombia 2015-2021 | |

| YEAR | # VENEZUELAN HUMAN MOBILITY IN COLOMBIA |

| 2015 | 10,780 |

| 2016 | 378,965 |

| 2017 | 796,234 |

| 2018 | 1,359,815 |

| 2019 | 1,095,708 |

| 2020 | 1,729,537 |

| 2021 | 1,742,927 |

The aforementioned data show that historically, international migratory flows have influenced the configuration and development of the territory of San José de Cúcuta and its Metropolitan Area, initially with significant contributions to the reconstruction and development of the territory and, subsequently in response to its profile as a country of origin, transit, destination and return Migrant Workers Committee (2020) showing weaknesses in territorial planning such as the increase in informal settlements, informal land appropriation, problems associated with infrastructure and the provision of health services, unemployment, poverty, insecurity and the affectation of public space and the environment, among others (Migrant Workers Committee, 2013)

In this sense, for authors such as Ayala and Coronel 2019, the availability of land in the territory guarantees the generation of housing, social infrastructure and complementary uses necessary for the functioning of the city. The city of San José de Cucuta and its Metropolitan Area has experienced throughout its history the scarcity of developable land, due to the territory's dynamics, due to the lack of application of the objectives and functions of urban planning, and elements that allow the regulation of land use, thus projecting the development of the city and accurate response to phenomena such as human mobilities or large-scale migratory flows, which have transversally impacted all sectors and the security of society (health, services, economy, infrastructure and population) (United Nations, 2019).

Another problem associated with the lack of control and regulation in territorial planning is the socio-urban phenomena: associated with socioeconomic conditions, high rates of unemployment and informality and the migratory phenomenon; present in the city system, as a result of its binational or border profile; which directly affect land planning and occupation, in addition to conflicts related to the informal occupation of the territory, characterized by the location of housing in high-risk areas and the proliferation of irregular settlements. This fact has been more evident in the city of San Jose de Cucuta due to its configuration as the articulating nucleus of the Metropolitan Area and as a host, receiving or transit city for Venezuelan migration.

In 2015 San Jose de Cucuta stood out nationally among the ten cities with the best real estate dynamics Instituto Geografico Agustín Codazzi, 2016. In 2016 the DANE 2017 noted that San José de Cucuta and its Metropolitan Area registered the second highest unemployment rate and in 2017 the massive arrival of Venezuelan migrants to informal settlements located in the western road ring increased. In this regard, in 2018 the United Nations (2019) highlighted that for the January-October 2018 period, human mobility exceeded 66% of the data established for 2017 and the last five years. This when taking into account that around 30,000 people were displaced in 2018. It is noteworthy that Venezuelan international migration is considered the second migratory crisis after the one presented by Syria, generating a significant effect on the Colombian-Venezuelan border, which is still awaiting a solution by the governmental entities of each of the States parties.

Conclusion

Concerning the concept and particularities of migration, it can be concluded that the Colombian State and the international framework have relevant and current regulations through which the migratory phenomenon can be categorized and understood according to its characteristics, advocating for the guarantee of human rights and favoring the search for mechanisms to ensure their welfare and quality of life. In the case of the Colombian-Venezuelan border, it was established that its geographical framework defines the Colombian State (specifically San Jose de Cucuta) as a place of reception for migrants (Reception-Destination). However, it should be noted that despite having an important regulatory framework, it is essential to continue with the socialization of the same, being this an activity that is currently led by national and international authorities and organizations and institutions as support programs for the group of migrants.

The migratory phenomenon in the border territory has been present throughout history and has influenced the configuration of the territory, its increase (as of 2015) has generated the need to provide territorial responses in real-time, evidencing the case of San José de Cucuta and its Metropolitan Area weaknesses concerning the support of an infrastructure that allows guaranteeing the control and adequate treatment of the migratory phenomenon from the human point of view, as well as from that of its relationship with the context (health, housing, education and culture).

This goes against the development of the city and its basic functions, considering that sectors such as health, education and services have not been able to meet the needs of the new population sectors. As a consequence, the urban landscape has been affected by the informal appropriation of land, the growth of unemployment rates, social segregation, social gaps and the failure to meet new life expectations, aggravating migratory problems and xenophobia.

In this sense, it is relevant that the national migration policy contemplates specific aspects for border areas, since their dynamics differ from those present in other cities of the territory, for this reason, the challenges in migration matters are related to the generation of instruments that favor the articulation of governmental entities, international and national cooperation agencies, the private sector and civil society; to promote the regularization and integration of migrants to the context of their host territory. In addition, migration must be assumed under a sustainable vision through which it seeks to reduce inequality and poverty in compliance with target 1 of the Sustainable Development Goals.

References

Abu-Warda, N. (2008). International migrations. 'Ilu. Journal of Sciences of Religions, 33-50.

Angel, R.E. (1990). History of cúcuta: the house of the goblin. Cucuta: Hergora Workshops.

Canese, M.I., Estigarribia, R., Ibarra & Valenzuela R. (2021). Applicability of the sequential exploratory design for the measurement of cognitive skills: an experience at the national university of asunción, paraguay. UTIC Research, 7(2), 63-76.

Colombian Congress of Colombia. (1943). Law 13 of 1943. By which the border regime statute is approved, signed by the republic of colombia and the united states of venezuela, in caracas, on august 5, 1942. Official Gazette no. 25209.

Colombian Migration. (2016). Foreigners in Colombia 2015-2016. Migratory approach to their trajectories in Colombia. Bogota: Migration Colombia.

Colombian Migration. (2020). Annual bulletin of migratory flow statistics 2020. Bogotá: Migración Colombia.

Comision Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. (2015). Human mobility. Inter-American Standards. Washington: OAS.

Congress of the Republic of Colombia. (1994). Law 146 of 1994. Through which the "International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of all Migrant Workers and their Families" is approved, made in New York on December 18, 1990.

Febres, L. (1926). The cucuta earthquake: writings referring to this catastrophe, with some data on the physiognomy of the ancient city and the modern city. Bogota: Banco Popular.

Gomez, J. (2010a). Volume 1. Technical support document. Part one: major issues and guidelines for review. Mayor's office of san josé de cúcuta.

Gomez, J.A. (2010b). International migration: Theories and approaches a current look. Economic Semester, 13(26), 81-89.

Gomez, L. (2011). A space for documentary research. Theoretical and Practical Clinical Psychological Vanguard Journal, 2(1), 226-233.

Gonzalez, MS. & M.J. Maldonado (2015). Historical treaties between colombia and venezuela: a look at the framework of táchira-norte de santander relations. Justice, (28), 151- 157.

Hamui-Sutton, A. (2013). An approach to mixed methods of research in medical education. Research in Medical Education, 2(8), 211-216.

Hernandez, R., C. Fernandez & P. Baptista (2014). Metodologia de la investigacion (sexta edicion). Mexico: Mcgraw Hill Education.

Interagency Group on Mixed Migratory Flows. (2021). Colombia Venezuelan refugees and migrants.

Labrador, G.L. (2017). Cucuta and Norte de Santander: historical configuration of an imagined community. Undergraduate thesis, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Linares, R. (2019). Security and border policy: a look at the border situation between Venezuela and Colombia. Opera, 24, 135-156.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mayo, L. (2015). International migrations. Report number i. Migrations from a theoretical perspective. University of California, San Francisco.

Mercado, Y. (2010). Metropolization in border areas. Cucuta in retrospect 1999-2010. Master's Thesis, Pilot University of Colombia.

Migracion Colombia. (2017). Annual bulletin of migratory flow statistics 2017. Bogotá: Migración Colombia.

Migracion Colombia. (2019). Annual statistics bulletin. Bogota: Migration Colombia.

Migrant Workers Committee (2020). Concluding observations on the third periodic report of Colombia. Nations.

Migrant Workers Committee. (2013). General Comment No. 2. On the rights of migrant workers in an irregular situation and their families. United Nations.

National Administrative Department of Statistics. (2018). National population and housing census. CNPV.

National university of Colombia. (2021). Metropolitan Area of Cucuta, a binational mobility.

Palomares, M. (2020). Five years after the start of the venezuelan exodus, integration is urgent in colombia. Weekly magazine.

Presidency of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. (2015a). Decree 1950 of 2015. by means of which the state of exception is declared in the municipalities of bolívar, pedro maría ureña, junín, capacho nuevo and rafael urdaneta of the state of táchira. Official Gazette 142.

Presidency of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. (2015b). Decree 1969 of 2015. The state of exception is issued in the municipalities of lobatera, panamericano, garcía de hevia and ayacucho in the state of táchira. Official Gazette 40735.

Presidency of the Republic of Colombia. (2015). Decree 1770 of 2015. By which the state of economic, social and ecological emergency is declared in part of the national territory.

Sierra, O.M., L.K. Colonel & E.T. Ayala (2020). Gender perspective in migratory phenomena: socio-economic and labor study of the colombian-venezuelan border. Espacios Magazine, 41(47), 198-212.

Special Administrative Unit Migration Colombia. (2018). Resolution 3346 of 2018. Whereby the pip-tt temporary transit entry and permanence permit is added to resolution 1220 of 2016.

Treaty of Tonchala. (1959). Agreement signed between the foreign ministers of Colombia and Venezuela.

United Nations. (2019). Humanitarian needs overview. OCHA.

Urdanet, A. (1988). San jose de cucuta, in the marabino trade of the 19th century. Americanist Bulletin, (38), 247-58.