Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 3

Contemporary local government planning in developing countries: proposed new framework for change in South Africa

Johannes Mulaudzi, University of Venda

Johannes Francis, University of Venda

Johannes Zuwarimwe, University of Venda

Johannes Chakwizira, University of Venda

Citation Information: Mulaudzi, J., Francis, J., Zuwarimwe, J., Chakwizira, J., (2023). Contemporary Local Government Planning In Developing Countries: Proposed New Framework For Change In South Africa, International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 27(3), 1-16

Abstract

Integrated development planning is a comprehensive planning process that provides a framework for local government to align development plans and programs with the needs of communities. In South Africa, the integrated development planning was enforced to promote local democracy and fast-track service delivery. Numerous weaknesses inherent in the phased process necessitate its interrogation. This article presents a new framework for integrated development planning in South Africa. The framework is informed by an interrogation of the gaps in the existing process. Data was collected through the sequential exploratory mixed methods such as interviews, multi-stakeholders workshops and questionnaire. The study found that the existing process lacks stakeholders buy-in and ownership and doesn’t respond to community needs. A refined process is recommended, calling for compulsory stakeholder participation and the merger of project and integration phases. The article contributes to the body of empirical research by investigating and generating a practical framework of integrated development planning in practice.

Keywords

Integrated Development plan, Integrated Development planning process, Refined integrated development planning, Inclusive stakeholders participation

Introduction

This article presents a new framework for integrated development planning in South Africa, in the context of contemporary local government planning in development countries. The proposed framework is informed by the interrogation of the existing integrated development planning in South Africa. In South Africa, the integrated development planning framework was introduced in 2000 to enhance the transformation of municipal planning processes (Mathebula & Sebola, 2019). This came as a follow up to the African National Congress (ANC) led government’s 1994 Reconstruction and Development Programme which identified the need for participatory and inclusive planning (ANC, 1994). The new approach was meant to transform the typical modernist planning system, which was rigid, to a more democratic, strategic and developmental type of planning system (Mangwanya, 2019). Furthermore, it replaced the top-down apartheid regime segregation planning approach with a bottom-up planning process that provided for public, private and voluntary sectors involvement in local government (Dlamini & Reddy, 2018). To achieve this, Municipalities are compelled by the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996 and the Municipal Systems Act of 2000 to adopt integrated development plan to guide the planning and development across the entire municipal area (RSA, 1996; 2000).

The integrated development planning is intended to promote the participation of grassroots communities in the development processes of Municipalities, assist in coordination of the three spheres of government (namely local, provincial and national), equitable distribution of resources and fast-tracking the delivery of services (Dlamini et al., 2021). It is a demand-driven approach to service delivery, where the communities and the municipal officials identify and prioritize needs for the municipal planning and budgeting processes (Nabatchi et al., 2017; Huq, 2020). The process is made up of six phases which are interdependent and operate as a value chain with each phase providing guidance to the other. The phases include preparation, analyses, strategy, project, integration and approval phases.

Since its introduction in 2000, integrated development planning has been assumed to be the most effective planning tool for service delivery in local government. However, municipalities have been met with several service delivery challenges which in some cases resulted in community unrests. This has affected the implementation of projects. In Mpumalanga province of South Africa, for example, the section 71 report on municipal performance for the financial year 2019-2020 highlighted that a total of 73 projects were not completed in Mpumalanga’s 20 municipalities (17 local and 3 districts) due to community protests (Mpumalanga Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, 2020). According to the previous studies conducted on integrated development planning (Mathebula & Sebola, 2019; Sebake & Mukonza, 2020), depending on the municipality, some of the impediments to the delivery of services include community unrest due to lack of participation and constant political infighting in municipal Councils. It is for that reason that this study assessed the existing integrated development planning process in order to suggest a new planning framework that will not only facilitate meaningful grassroots communities participation but will improve the integrated development planning for sustainable delivering of basic services in South Africa and other African countries.

Problem Statement

It has been established in the introductory section that most municipalities in South Africa are experiencing service delivery challenges, which may be causing community unrests. For example, Mbombela Municipality in Mpumalanga province of South Africa service delivery protest report of 2018 and 2019 have shown that the Municipality has recorded an increase in the community unrest from 10 in 2018 to 24 in 2019 and the protests were due to the non-delivery of services. The Municipality integrated development plans for 2001-2005, 2006 to 2010 and 2011 to 2015 indicate that the residents have been raising issues of lack of water, roads, electricity and refuse removal. However, no progress has been made despite the issues being listed in the integrated development plan (s). This is a problem because there are projects that are funded by the municipality in each and every financial year which are different from what the communities have raised. In a similar study, (Msenge & Nzewi, 2021) found that the communities are not satisfied with the integrated development planning because it does not respond to their needs. Lack of meaningful participation of communities in integrated development planning processes was cited as the major challenge. This challenge is exacerbated by the lack of universally practical framework that can be adopted to improve the workings of the integrated development planning, particularly on how to achieve actual and inclusive participation of stakeholders in the process. Existing literature, policymakers and development agents do not give sufficient information on the extent at which communities should participate in order for the process to be a success.

Considering that the objective of the integrated development planning process is to enable Municipalities to fast-track service delivery, ensure equitable distribution of state resources and promote public participation, it is not clear why there are consistent service delivery protests in most of the local Municipalities in South Africa. This problem persists despite the requirement of the integrated development planning according to which all the stakeholders, including communities, have to participate throughout the entire process. Various scholars (Mathebula & Sebola, 2019; Sebake & Mukonza, 2020) have argued that although the integrated development planning is a critical development tool at the local government level, it has challenges with respect to the performance in providing services to the communities. Nowak (2020) argues that it is the inadequate input from the stakeholders during the phases of the integrated development planning that is a challenge. In view of the above, this study made an assessment on the current integrated development planning to determine the gaps in the process and propose a new planning framework which should be applied in the local municipalities in South African and elsewhere.

Literature Review

Origin of Integrated Development Planning

Planning is a continuous process and is frequently defined to cover any effort to select the best means to attain desired ends (Beauregard, 2020; Huq, 2020; Alexander, 2022). Although the principle of exertion is inherent in planning, it has been labelled as rigid, complex and autocratic in nature (Coetzee, 2012). The planning approaches were seen to be good on paper but not able to facilitate growth and development. However, there has been a gradual shift towards the inclusive planning system which is more democratic, strategic and developmental in nature (Asha & Makalela, 2020). Various scholars conceded that the new planning system has created a platform for citizen participation and have obliged government to build institutional capacity and allocate more funding towards community development (Cornwall, 2008; Banda et al., 2021).

The integrated development planning is an example of the planning tools which came as a result of a shift from autocratic approaches to more democratic, strategic and integrated forms, particularly in developing countries (Coetzee, 2012). This includes moving away from the notion of top-down planning which is done at government level without involving the citizenry to bottom up where grassroots communities have a say in the development taking place in their areas. (Dlamini et al., 2021) notes that integrated development planning is a tool used to drive a needs-based approach in which equal delivery of services, institutional transformation and participatory governance are attained. It is sometimes viewed as a political and social reconciliation tool, particularly in countries with post-conflict societies (Dlamini & Reddy, 2018). This is motivated by the fact that the integrated development planning model strengthens democracy and promotes coordination between different role players to achieve the desired outcome (Mamokhere, 2021). This also explains why, throughout the world, researchers and policymakers have given special attention to the various models of decision- making tools such as integrated development planning.

Globally, models similar to integrated development planning has been adopted by many countries in the world. The model has been applied differently, for different reasons and called by different names. For example, in North America, Canada in particular, a similar model called an Integrated Community Sustainable Plan (ICSP) is used to promote democracy and facilitate integrated planning across all spheres of government (Grant et al., 2018). The ICSP serves as a strategic business plan for the communities to identify short, medium- and long-term actions for implementation and is reviewed on an annual basis. Since its inception, the ICSP is faced with challenges associated with conceptual and jurisdictional barriers to integrate the full spectrum of proportions of planning processes toward a sustainable city. To address this challenge, the government of Canada adopted a system which requires regular refinement of the process to develop the ICSP. This process is in line with the purpose of the current study. The identical planning shift was also observed in countries such as Mexico, New Zealand, Switzerland and United Kingdom (Yudarwati, 2019; Othengrafen & Levin-Keitel, 2019; Huq, 2020).

In Africa, the United Nations (UN, 2001) established the Peace building Commission through the Integrated Mission Forces (IMFs) to advocate for the integrated post- conflict development planning process, especially for countries in the transition from war to lasting peace (Chettiparamb, 2019). This was also implemented in African countries such as Sierra Leone, Liberia and Sudan. The rationale behind the IMFs was to promote and encourage integrated planning from different perceptions to allow decision makers to find best solutions to key service delivery issues (Masiya et al., 2021). For example, in Sierra Leone, the government adopted the development plan to guide the development of the locality and form the basis for preparation of the annual budget. The concept was meant to assist local government to provide services and create an opportunity for all individuals and community groups to contribute to the development of their areas (Freetown City, 2019). The plan was developed in a more participatory fashion, aligning with top-down and bottom-up approach as well as bringing the spatial analysis dimension at the community level. Due to persistent service delivery protests, the city embarked on a process to refine the process leading to the finalization of plans, something which is imminent in South African local government. In turn, this has led to the creation of opportunities for all relevant stakeholders including vulnerable communities, to be part of the plan (Freetown City, 2018).

In the Southern African Development Community (SADAC) region, Zambia and South Africa have adopted the similar concept of integrated development planning respectively. In Zambia, the concept is at the initial stage and most municipalities are still struggling to develop their integrated development plans (IDP) due to lack of capacity and guidelines. The Zambian government together with the stakeholders are in the process to establish the ideological hegemony that befits the Zambian context and is also relying on the success of the South Africa model (Banda et al., 2021). In South Africa, the integrated development planning was introduced in 2000 to enhance the transformation of municipal planning processes (Mathebula & Sebola, 2019).

In South Africa, Municipalities were compelled in terms of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996 and the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act of 2000 to adopt IDP to guide the planning and development across the entire municipal area (RSA, 1996; 2000). Integrated development planning was expected to promote the participation of communities in the development processes of Municipalities (Dlamini et al., 2021). It was also expected to coordinate the work of the three spheres of government (namely local, provincial and national), equitable distribution of resources and fast-track service delivery. The concept was also meant to guide a demand-driven approach to service delivery, where the communities and the municipal officials identify and prioritize needs that must be considered in the municipal planning and budgeting processes (Nabatchi et al., 2017).

Overview of the Integrated Development Planning Process

The integrated development planning is the creation of a process which integrates procedural and substantive aspects of planning (Asha & Makalela, 2020). It is comprised of six phases which include preparation, analyses, strategy, project integration and approval. The phases are interdependent and operate as a value chain with each phase providing guidance to the other. The South African Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs IDP Guide spells out that the integrated development planning begins with the preparation phase (Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs, 2000). This outlines the time schedule, approach to public participation, institutional structures and define the stakeholders’ roles in the entire process (integrated development planning). Apart from the preparation phase being part of the integrated development planning, each Municipality is required, in terms of the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act of 2000 and Municipal Finance Management Act of 2003, to approve the process plan to guide the development of the IDP (RSA, 2000; 2003). According to (Adonis & Walt, 2017), the challenge with the preparation phase is that it seems to be done for compliance purposes and stakeholders are not consulted when developing the process plan. This has resulted in poor consultation because stakeholders do not understand their role in the integrated development planning.

The first phase of integrated development planning is the analysis phase where residents identify their needs in accordance with their urgency. (Tibane, 2017) explains that during this phase information is collected on the existing conditions and at the end, the Municipality must have a report on the assessment of the existing level of development, details on priority issues, problems and their possible solutions, and the information on available resources. This is in line with the Municipal Planning and Performance Regulations of 2001 which requires Municipalities to have a spatial development framework providing strategic guidance in respect of the location and nature of the development. Furthermore, the analysis phase plays a vital role in the success of the IDP because it forms the basis for the successive phases (Nomdo et al., 2019; Asha & Makalela, 2020). However, as (Munzhedzi, 2020) notes, communities are not consulted in the entire analysis phase; they participate only in identifying problems but not in determining which projects should be prioritized.

The second phase is the strategy phase. According to (Tibane, 2017), during this phase, the Municipality works on finding solutions to the problems identified in the initial phase. The DPLG IDP Guide Packs of 2000 also require that a vision, objectives and strategies must be developed as part of the third phase. (Dlamini & Reddy, 2018) note that this is one of the key phases in the integrated development planning, because it provides stakeholders with the opportunity to participate in designing strategies to address the challenges outlined in the analysis phase. The problem in this phase is that it seems like it is only done for compliance purposes because stakeholders are neither consulted nor agree on the strategies, as a result of which the phase does not add value to the IDP (Tibane, 2017).

The third phase entails converting strategies into programmes and projects. According to the Department of Provincial and Local Government of 2000, the project phase must contain the projects that will be of benefit to the community, how much it will cost, how the projects will be funded, how long it would take to complete and who is going to manage the project. In this regard, (Mathebula, 2018) argues that the project phase is one of the most disputed phases between Municipalities and the communities, and one of the major causes of service delivery protests in South Africa. (Biljohn, 2019) adds that there is no alignment between what is identified by communities in the analyses phase and the projects identified. This sentiment was echoed by other scholars (Sebola, 2017; Masiya et al., 2019) who indicated that the challenge with this phase is that it is done in-house by municipal officials without consulting the stakeholders and without considering what has been identified in the analysis phase.

In the fourth phase of integrated development planning, the Municipality is accorded the opportunity to ensure that the projects identified are aligned with the objectives and strategies as set out in the strategy phase. (Baloyi & Lubinga, 2017) argue that, there is less alignment between the Municipalities, districts and sector department projects, which makes this phase difficult to complete. For example, in Mbombela Municipality, the Department of Human Settlement constructed and handed over RDP houses in an area with no services such as water, electricity, roads and sewerage, which led to service delivery protests. For that reason, the Municipality was forced to divert from its plan and provide services to the communities to prevent further protests.

The fifth and final phase involves the approval of the IDP in line with the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act of 2000. In this phase, the Municipality is required to approve a draft IDP and then consult all the stakeholders before approving the final IDP for implementation (RSA, 2000). The expectation is that by the time the IDP is approved, all the stakeholder inputs would have been addressed and incorporated into the final report. Contrary to this, (Tibane, 2017) argues that immediately after the IDP has been approved; communities still embark on protests expressing their dissatisfaction with the approved IDP. (Tibane, 2017) further suggests that there is a need to simplify the integrated development planning process and to focus more on strategic issues, which implies that Municipalities must move away from the one-size-fit-all process of IDP and adopt a process which suits their situation, taking into consideration the issues of capacity, both with regards to internal officials and external stakeholders.

In conclusion, (Hlongwane & Nzimakwe, 2018) purports that municipalities must demonstrate technical and financial competency to implement the IDP. However, there is generally shortage of personnel and the lack of capacity of those responsible for integrated development planning to manage the process effectively in Municipalities. This notion was echoed by (Khambule & Mtapuri, 2018) who noted that there are some Municipalities that are still using consultants to compile the IDP and key sector plans such as the SDF, local economic development strategy and rural development strategy. This shows that there is no internal ownership of the process, which affects the quality of the IDP in delivering the services to the communities.

Research Methods and Design

Empirical data was collected from the Mbombela municipality of Mpumalanga province of South Africa. The municipality was randomly selected. This was motivated by the fact that all the municipalities in South Africa use the similar integrated development planning process and same participants.

The study adopted sequential exploratory mixed methods design for data collection and analysis. These designs, according to (Creswell & Clark, 2017) are grounded in exploration research approach where data is collected in phases. In the context of this study, the first phase constituted qualitative data collection and analysis; and the results thereafter informed the second phase which was quantitative data collection and analysis. During the first phase, the study key informants were purposively selected based on their role and involvement in the integrated development planning process. A census of the two hundred and sixty five (265) stakeholders who are in the database of integrated development planning structures of Mbombela Municipality was done. The stakeholders included the Councillors, Ward Committees, Community Development Workers, Organized Business, Community Leaders, Traditional Leaders and War Rooms. Data was collected using multi-stakeholders workshops and semi-structured interviews which were conducted to the 265 stakeholders and the key informants such as Mbombela Municipality General Managers, Members of the Mayoral Committee, IDP Practitioners within the Ehlanzeni District Municipality and the Mpumalanga Provincial Department of Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs respectively. The multi-stakeholder workshops were chosen to maintain the existing stakeholders configuration and draw their knowledge and experiences on integrated development planning in a more collaborative and participatory nature. Interviews were conducted with seven officials and Councillors who were purposively selected on the bases of their direct involvement and experience in the integrated development planning. These included IDP Manager (1), Budget Manager (1), Public Participation Manager (1), Strategic Planning and Research Manager (1) at Ehlanzeni District Municipality, Members of the Mayoral Committee (2) and Deputy Director IDP: Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (1). The participants were engaged to explore their perspective on the overall observations and thoughts on the integrated development planning process and its influence on service delivery. Special attention was given to the participants’ perceptions on the weaknesses of each phase of the integrated development planning process.

The results from the multi-stakeholders workshops were summarized and organized into sub-themes. The consolidated information was then used to construct a structured questionnaire with closed-ended questions which was administered to the same informants as the second phase of the study. This was part of the quantitative data which was used to authenticate the results from the qualitative data. The structured questionnaires were administered to the 265 respondents who participated in the first phase of the study and the data was analyzed using the Thematic Content Analysis. The data was logical packaged and transcribed into reflective statements and analyzed. This was achieved through coding text and developing descriptive themes to establish whether there are common themes from the responses given by key informants. The data was stored in the Microsoft Office Word Processor before being exported to ATLAS.ti version 8.4 which is a qualitative data analysis software package.

Results

Demographic Information

Seventy-six percent of the 180 participants in the study were aged between 36-50 years old and a greater proportion (52 %) of them were female with youth constituting 21 % of the total number of the respondents. Fifty-six percent of the participants had secondary school education, followed by twenty-two percent (22 %) who had tertiary qualifications. The rest have primary level schooling (15 %) with those having no formal education making the remaining 7 %. Slightly less than half (46 %) of the participants were employed as casual workers with part-time employees making up 22 % of the total number with the 17 % being unemployed and those in full-time employment making the remaining 15 %.

Level of Stakeholder Participation in the Integrated Development Planning

To understand the level of stakeholder participation, it was found that the majority of respondents (56 %) did not participate in formulating the IDP compared to only 44 %. Out of those who did not participate, 26 % indicated that they did not participate as their views were not considered; while 16 % indicated that they were never afforded an opportunity to participate. Furthermore, 10 % did not participate as they did not understand their role with 3 % not participating as they did not understand the language used. Of the 44 % respondents who participated in the integrated development planning process, 18 % and 16 % participated in the analysis and approval phases respectively, while 10 % participated in the strategy phase, project phase and integration phase respectively.

Perceived Weaknesses in Phases of the Integrated Development Planning

Fifteen (15) subthemes were distilled out of the one hundred four (104) quotations drawn from the responses with regard to the weaknesses in phases of the integrated development planning. The 15 subthemes were further categorized into five (5) broader themes, names “Stakeholder participation”, “Integrated planning”, “Skills”, “Baseline data” and “Monitoring and evaluation” (Table 1).

| Table 1 Weaknesses Of Phases Of The Integrated Development Planning |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase of the IDP | Perception | IDP Practitioners | Councillors | Ward Committees | Community Development Workers | Organized Business | Traditional Representatives | War Room | Total |

| Analysis phase | Stakeholder participation | ||||||||

| i) Lack of stakeholder involvement | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 9 | |

| Skills | |||||||||

| i) Lack of understanding of municipal processes | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| ii) Wish list of community needs | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 7 | |

| Baseline Data | |||||||||

| i) Outdated baseline and insufficient information (backlogs) | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| Strategy phase | Stakeholder participation | ||||||||

| i) Lack of stakeholder involvement | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Skills | |||||||||

| i) No strategic planning reports | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| Project phase | Stakeholder participation | ||||||||

| i) Lack of stakeholder involvement | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 10 | |

| Integrated Planning | |||||||||

| i) Project misalignment to the community priorities and sector plans | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 10 | |

| Integration | Stakeholder participation | ||||||||

| i) Lack of stakeholder involvement | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 8 | |

| Integrated Planning | |||||||||

| i) Misalignment of municipal and sector departments programs | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| Approval | Stakeholder participation | ||||||||

| i) Lack of stakeholder involvement | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |

| Analysis Phase | Stake holder Participation | ||||||||

| Involvement | |||||||||

| ii) Community inputs are not addressed | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |

| Skills | |||||||||

| i) Lack of understanding on municipal process | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

| Monitoring and Evaluation | |||||||||

| i) Poor implementation of projects | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | |

| ii) No regular feedback | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| Total | 17 | 15 | 17 | 11 | 19 | 8 | 15 | 102 | |

The theme “Stakeholder participation” was the most popular response in all the phases of integrated development planning process. This was followed by “Integrated planning” and “Skills” respectively, with “Baseline data” and “Monitoring and evaluation” obtained the least quotations. The “Lack of stakeholders’ involvement” and “Project misalignment to the community priorities and sector plans” were cited unanimously and most common, particularly on the analysis phase, project phase and approval phase. Distributions of quotations also varied amongst interest groups with respect to “Project misalignment to the community priorities and sector plans”, “Outdated baseline and insufficient information on backlogs and wish list of community needs”. These results were further ranked according to the scores (Table 2).

| Table 2 Ranked Scores Of Respondents On The Weaknesses Of Integrated Development Planning |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Weaknesses of the phases of the integrated development planning value chain | Mean Score | Standard Deviation | Ranking |

| Stakeholder participation | |||

| i) Lack of stakeholder involvement | 8.36 | 1.755 | 1 |

| ii) Community inputs are not addressed | 8.31 | 1.649 | 2 |

| Integrated Planning | |||

| i) Project misalignment to the community priorities and sector plans | 7.82 | 1.804 | 4 |

| ii) Misalignment of Municipal and sector departments programs | 7.52 | 2.326 | 7 |

| iii) Outdated baseline and insufficient information (backlogs) | 7.59 | 1.938 | 6 |

| Skills | |||

| i) Lack of understanding of municipal processes | 7.28 | 1.856 | 8 |

| ii) No strategic planning reports | 6.73 | 2.89 | 9 |

| iii) Wish list of community needs | 7.73 | 2.053 | 5 |

| Monitoring and Evaluation | |||

| i) Poor implementation of projects | 7.97 | 1.886 | 3 |

| ii) No regular feedback on projects implementation | 7.97 | 2.04 | 3 |

| Key: Rank = position of statement within the themes: the higher the mean score, the more pressing the issue. | |||

Below are some of the verbatim quotes which interest groups expressed regarding the major weaknesses on the integrated development planning process?

“I feel like attending IDP meeting is a waste of time. All our inputs are not considered or `prioritised” (Ward Committee).

“Community members should be trained about the phases of the integrated development planning” (IDP Practitioner).

“We should improve our planning using the updated baseline data from SERO report, master plans….in order to ensure that the integrated development plans respond to the needs of people” (War Room).

Discussions

The majority of the stakeholders who participated in the study were adults and predominantly female. Studies carried out by various scholars (Khambule & Mtapuri, 2018; Molefe & Manamela, 2021) revealed that most service delivery related programmes such as integrated development planning are dominated by women as compared to the male counterparts. Apparently, the non-availability of basic service such as water, electricity and sewer have a direct effect to women because they get frustrated when there is no water to bath, clean or wash and electricity to cook. This in turn, encourages women to participate in processes like integrated development planning that are aimed at discussing service delivery matters. The fact that youth constitute only twenty-one percent of the total respondents is a major concern in the credibility of integrated development plan considering that they form the majority of the Municipality and South African population (Stats, 2020). Logically, it means that youth should be involved in the development planning processes in particular the integrated development planning make sure that their interests are covered. Thus, the question is whether the low number youth in the integrated development planning process is associated with them being side-lined or unwillingness to participate in the process.

Most respondents had attained secondary and tertiary education. This might imply that the stakeholders who are involved in the integrated development planning process do have sufficient knowledge to actively participate in the process. This observation is in agreement with the findings of (Maharaj, 2020) study which revealed that education is one of the indicators that depicts the level of development and the potential for one to have better chances of participating and contributing positively in the integrated development planning process. Therefore, the failure or challenge in the integrated development planning process in Mbombela Municipality cannot be linked with education status of the stakeholders, but rather the lack of understanding of the process itself.

The majority (56 %) of the respondents did not participate in the formulation of the IDP. This is despite the legal requirement (Municipal Systems Act, the White Paper on Local Government and the Municipal Planning and Performance Regulations) that Municipalities must involve the stakeholders, including the communities, in the core municipal process such as integrated development planning. This observation might imply that grassroots communities are not satisfied with the manner in which integrated development planning is being implemented, particularly with regard to stakeholder involvement. Some stakeholders reported that they were only invited to submit community needs during the analyses phase and requested to comment on the draft IDP document as part of the approval phase; and no feedback was given on whether their inputs were considered or not. These sentiments were supported by (Sebola, 2017) who argued that Municipalities do conduct participation for compliance purposes and don’t consider inputs from grassroots communities when finalizing the IDP, resulting in disputes on the final product.

Building on the above arguments, previous studies conducted in South Africa (Marambana, 2018; Sebake & Mukonza, 2020 reveal that the non-consideration of inputs or views of grassroots communities is a major shortcoming which deters the integrated development planning process to fulfil its obligation of fast-tracking the delivery of basic services to the communities. Similarly to this study, a large proportion of respondents revealed that they did not participate because their views were not considered which raises questions on whether the persistence service delivery in the Mbombela municipal area was triggered by the credibility of the integrated development planning process. This result corroborated the observations of (Banda et al., 2021) who pointed out that most IDPs have failed due to lack of community buy-in and support. In a similar study, (Dlulisa, 2013) found that the Randfontein Municipality was unable to spend their annual budget because of community protests caused by the disputes on projects allocation criteria. Those that didn’t have projects on the IDP accused the Municipality of unfair allocation of projects and budget. For this reason, stakeholders’ participation should be cross-cutting in all the phases of the integrated development planning process, whereby each phase will be subjected to scrutiny prior finalization to ensure quality and buy-in from all the stakeholders (Dinbabo, 2003; Munzhedzi & Phago, 2020).

The lack of integrated planning was also cited as another major weakness in the integrated development planning process. Respondents in the study revealed that there is a disjuncture between the community needs and government projects (municipality, provincial and national government). To be precise, the projects outlined in the municipality IDP for implementation is not responding to the needs of the communities which were submitted for consideration during the public participation process. This finding is in consistent with (Tibane, 2017) study which confirmed that there is no alignment between community needs and government priorities. Presumably, this could be attributed to the fact that communities were not involved in the project identification phase of the integrated development planning process. This reality justifies the need for Mbombela local municipality to introduce compulsory stakeholders’ involvement in all the phases of the integrated development planning process and also merge the project phase and integration phase to form one phase.

The respondents further identified lack of skills as another weakness in the integrated development planning process. Key stakeholders were found not to have the capacity to compile service delivery reports of their area, despite them have attained secondary and tertiary qualification. This observation is in agreement with the findings of other studies (Dlamini & Reddy, 2018; Biljohn, 2019) where most of the role players in the integrated development planning process were unable to interpret the IDP documents and could not produce any report, including the status of service delivery in their area. Taking these facts into account, it can be argued that community awareness and training of key stakeholders are crucial in equipping grassroots communities with the knowledge and skills on integrated development planning processes.

Lastly, the respondents cited the lack of baseline data and monitoring and evaluation as the least weaknesses in the integrated development planning process. The stakeholders indicated that the statistical data used for planning and budgeting in the Mbombela local municipality were outdated which hinders the IDP from responding to the needs of the communities. This observation was supported by (Tibane, 2017) who argued that the quality of data used for planning has the ability to enable the IDP to response to the needs of the communities. Thus, building capacity in the research units within Municipalities is important in solving the challenge of baseline data.

Building on the above arguments, respondents indicated that poor service delivery is caused by lack of monitoring of IDP projects. In some instances, grant funding of some projects are withheld by National Treasury due to non-spending. It was revealed that this emanated from a perceived lack of accountability and consequence management for poor performance of municipal officials, particularly the Accounting Officer and Senior Managers. This observation is in line with (Nowak, 2020) findings which confirmed that poor performance were a problem that delays the implementation of projects in municipalities. (Dlulisa, 2013) notes the possible establishment of an independent multi-disciplinary team comprising of key stakeholders existing in the Municipality to monitor the implementation of all the IDP projects. This will not only solve the challenge of project implementation but improve the quality of all the phases of the integrated development planning process.

The Refined Integrated Development Planning

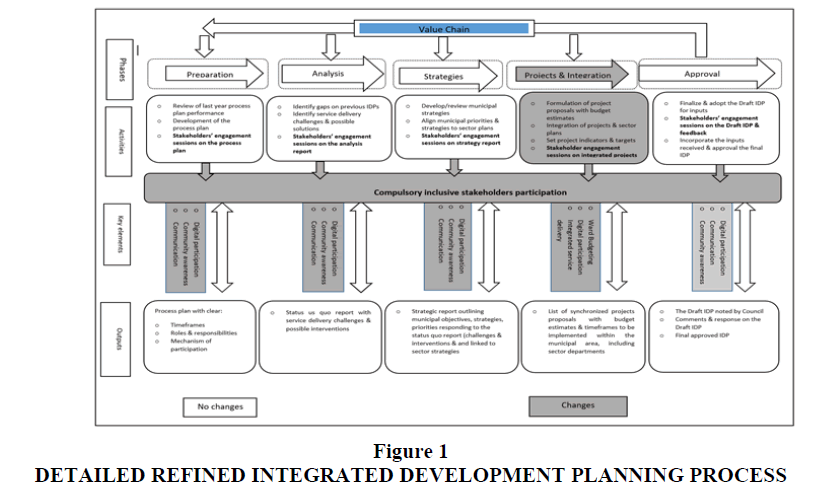

The study recommends a refined integrated development planning for South African and other African countries (Figure 1). The refined process highlights compulsory inclusive stakeholder participation in all the phases to solicit community buy-in and improve quality of individual phases and the amalgamation of project and integration phases to ensure coherent project planning and implementation. Lastly, the key planning elements such as digital participation, ward-based budgeting, integrated service delivery; integrated community awareness and communication are infused to the integrated development planning.

The refined process is accompanied by a brochure which exhibits the changes made in the process and also specify the required activities according to individual phases.

Conclusion

The study concludes that the current integrated development planning has failed to fulfill its obligation of providing services to the communities. Most participants agreed that grassroots communities are not satisfied with the integrated development plan because it does not respond to their needs. They also felt that they are not afforded an opportunity to raise their views on the integrated development planning process. The result is that the approved integrated development plan lacks community by-in and ownership, which in many cases has led to disputes by community unrests. The study therefore proposes the amalgamation of project and integrated phases to form one phase and the compulsory inclusive stakeholder’s participation in all the phases of integrated development planning process. This proposal is in line with the literature reviewed in this study (Dlamini & Reddy, 2018; Dinbabo, 2003, Munzhedzi & Phago, 2020) that grassroots stakeholder participation is very important in the success of the integrated development planning.

The study contributes to the body of knowledge in a number of ways. It contributes to the body of empirical research by investigating the integrated development planning in practice. It has generated a practical framework that can be adopted to improve the workings for the integrated development process in local government, particularly on how to achieve actual and inclusive participation of stakeholders beyond just ticking the box. The study has highlighted the importance of participation in development planning. The study which was motivated by the need to develop a refined integrated development planning becomes a timely intervention particularly in South Africa where despite the enforcement of an integrated development planning in all the Municipalities, persistent service delivery protests remains a challenge. The study has broadens the understanding of quality integrated development planning that is limited. For example, the study has offered five practical criteria to assess the quality of phases of integrated development planning.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the University of Venda, the National Research Foundation (NRF) for their financial support and the Mbombela municipality for the permission to conduct the study in the municipal area. In addition, the authors are grateful to the key stakeholders and IDP practitioners who responded to the numerous questions as this study was conducted.

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Authors’ contributions

Both authors have contributed equally to this work.

Ethical consideration

This study was part of the thesis submitted for a doctoral qualification. It was approved by the University of Venda Research Ethics Committee (ref. no. SARDF/19/IRD/03/1208).

Funding information

This research received funding from the National Research Foundation.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

Aklilu, A. S. H. A., & Makalela, K. (2020). Challenges in the implementation of integrated development plan and service delivery in Lepelle-Nkumphi municipality, Limpopo province. International Journal of Economics and Finance Studies, 12(1), 1-15.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Banda, B., van Niekerk, D., Nemakonde, L., & Granvorka, C. (2022). Integrated development planning in Zambia: Ideological lens, theoretical underpinnings, current practices, views of the planners. Development Southern Africa, 39(3), 338-353.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Biljohn, M. I. (2019). Developing the Participatory Capacity of South African Citizens in Municipal Service Delivery through Social Innovation. Politeia (02568845), 38(2).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Brinkley, C., & Hoch, C. (2021).The ebb and flow of planning specializations. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 41(1), 79-93.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cameron, R. (1996). The reconstruction and development programme. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 8(2), 283-294.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chimhowu, A. O., Hulme, D., & Munro, L. T. (2019). The ‘New’national development planning and global development goals: Processes and partnerships. World Development, 120, 76-89.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dinbabo, M.F. 2003. Development theories, participatory approaches and community development. Unpublished paper. Bellville: Institute for Social Development, University of Western Cape.

Dlamini, B., & Reddy, P. S. (2018). Theory and practice of integrated development planning-a case study of Umtshezi Local Municipality in the KwaZulu-Natal Province of South Africa. African Journal of Public Affairs, 10(1), 1-24.

Dlamini, B. I., & Zogli, L. K. J. (2021). Assessing the integrated development plan as a performance management system in a municipality. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, Vol. 25, Special Issue 1.

Dlulisa, L. (2013). Evaluating the credibility of the integrated development plan as a service delivery instrument in Randfontein local municipality (Doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University).

Huq, E. 2020. Seeing the insurgent in transformative planning practices. Planning Theory, 19 (4): 371-391.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Khambule, I., & Mtapuri, O. (2018). Interrogating the institutional capacity of local government to support local economic development agencies in KwaZulu-Natal Province of South Africa. African Journal of Public Affairs, 10(1), 25-43.

Maharaj, B. (2020). South African Urban Planning in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries—Continuities between the Apartheid and Democratic eras?. Urban and Regional Planning and Development: 20th Century Forms and 21st Century Transformations, 101-112.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mamokhere, J. (2021). Evaluating the Impact of Service Delivery Protests in Relation to Socio-Economic Development: A Case of Greater Tzaneen Local Municipality, South Africa. African Journal of Development Studies (formerly AFFRIKA Journal of Politics, Economics and Society), 2021(si1), 79-96.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mangwanya, M. G. (2019). Assessment of intergovernmental relations for efficiency and effectiveness of service delivery in Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality (BCMM), South Africa. Journal of Public Administration and Development Alternatives (JPADA), 4(2), 49-59.

Marambana, N. (2018). An analysis of stakeholder engagement in the integrated development planning process: a case of Blue Crane Route Local Municipality.

Mathebula, N. E., & Sebola, M. P. (2019). Evaluating the Integrated Development Plan for Service Delivery within the Auspices of the South African Municipalities. African Renaissance (1744-2532), 16(4).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mathebula, N.E. 2018. IDP implementation and the enhancement of service delivery: is there a link? Proceedings of International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives.

Mbombela Local Municipality. 2019. Mbombela service delivery protests report, Nelspruit, South Africa.

Mbombela Local Municipality. 2020. Integrated Development Plan, Nelspruit, South Africa.

Molefe, P., & Manamela, M. G. (2021). The Spatial Spread of Violent Service Delivery Protests in South Africa: A Question of Demonstration Effect versus Genuine Calls. African Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies, 10(3), 59.

Nabatchi, T., Sancino, A., & Sicilia, M. (2017). Varieties of participation in public services: The who, when, and what of coproduction. Public administration review, 77(5), 766-776.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Phago, K. (2020). Necessitating a Germane developmental local government agenda in South Africa: A post COVID-19 contemplation. African Journal of Governance & Development, 9(1.1), 181-199.

Republic of South Africa. 1996. The Constitution of South Africa Act, Act No.108 of 1996, Pretoria, Government Printers.

Republic of South Africa. 1998. White Paper on Local Government. Pretoria, Government Printers.

Republic of South Africa. 2000. Local Government Municipal Systems Act, Act No. 32 of 2000, Pretoria, Government Printers.

Republic of South Africa. 2001. Municipal Planning and Performance Management Regulations, Pretoria, Government Printers.

Republic of South Africa. 2020. Census 2020, Pretoria, Government Printers.

Sakiwo, K. 2020. An exploratory study of public participation during the Integrated Development Planning process: a case study of Theewaterskloof Local Municipality, Western Cape. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation. Cape Peninsula University of Technology.

Sebake, B. K., & Mukonza, R. M. (2020). Integrated Development Plan, Monitoring and Evaluation in the City of Tshwane: a confluence question for optimising service delivery. Journal of Public Administration, 55(3), 342-352.

Sebola, M. P. (2017). Communication in the South African public participation process-the effectiveness of communication tools. African Journal of Public Affairs, 9(6), 25-35.

Tibane, S.J. 2017. Integrated Development Planning in South Africa: The practices and applications of South African legislation and policies in the development of strategic plans, Lambert Academic Publishers.

Received: 01-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. IJE-23-13313; Editor assigned: 03-Feb-2023, Pre QC No. IJE-23-13313 (PQ); Reviewed: 17-Feb-2023, QC No. IJE-23-13313; Revised: 22-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. IJE-23-13313(R); Published: 02-Mar-2023