Research Article: 2024 Vol: 30 Issue: 1

Contemporary Issues in Job Design; How to design faire, healthy and productive jobs?

Samir Salhaoui, University of Batna1

Adil Argabi, University of Batna1

Amar Taleb, University of Batna1

Citation Information: Salhaoui, S., Argabi, A.,Taleb, A. (2024). Contemporary Issues in Job Design; How to Design Faire, Healthy and Productive Jobs? Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 30(1), 1-11

Abstract

The experience of work as an innate predisposition in humans has a significant impact on the well-being of individuals and families. The positive effects of work are reflected in many ways, such as increased productivity, job satisfaction, and family stability. On the other hand, work may also have negative effects, such as fatigue, burnout, stress, work-family conflict, accidents, and occupational diseases. given that human competencies are the essential competitive advantage of organizations, and that they perform their tasks and offer their skills at the level of their jobs, and considering that we as workers spend a significant amount of our lives in our jobs, there is an urgent need to change the way we think about designing and creating good jobs for both the organization and the individual.

Concept of Job Design

The concept of job design has been a subject of extensive research and theoretical development in the field of organizational psychology and management. Job design encompasses various aspects such as task allocation, social relationships, and the overall structure of work within an organization (Humphrey, Nahrgang, & Morgeson, 2007). It has evolved over time, with a shift from a focus on specific tasks and responsibilities to a broader consideration of the entire work experience of employees (Dahling & Lauricella, 2016). The significance of job design lies in its impact on employee behavior, attitudes, well-being, and performance (Lee J & Lee Y, 2018). Moreover, job design is not a static process; it is proposed to be dynamic and circular, with the variables acting as both predictors and outcomes (Clegg & Spencer, 2007). The core of job characteristics theory emphasizes that the design of the job determines the motivational state of the worker (Voet & Steijn, 2019). Additionally, job crafting, which involves employees customizing their work roles and job designs to make their work experience more meaningful and motivating, has gained attention as a proactive behavior that complements traditional job design theories (Kilic & Kitapçi, 2022). The literature also suggests that job design can be a strategy to enhance employees' work environment and facilitate job performance (Siengthai & Pila-Ngarm, 2016). Overall, the concept of job design has evolved to encompass not only the structure of tasks but also the broader work experience, emphasizing its dynamic nature and its impact on employee motivation, well-being, and performance.

Job design entails the systematic structuring and organization of a position, specifying the tasks, responsibilities, and relationships inherent in the role. It involves determining the procedures for task execution and delineating the relationships with other positions within the organization. more specifically, job design describes how "jobs, tasks, roles, and responsibilities are structured, enacted, and modified, and the impact of these structures, enactments, and modifications on individual, group, and organizational outcomes. Job design specifies the content of jobs to meet work requirements and to meet the personal needs of jobholders.

As organizations expand, supervisors and human resources professionals must help plan for new or growing work units. When an organization is trying to improve quality or efficiency, a review of work units and processes may require a fresh look at how jobs are designed. These situations call for job design, the process of defining how work will be performed and the tasks that will be required in a particular job, or job redesign, a similar process that involves changing the design of an existing job.

To design jobs effectively, one must fully understand the job itself (through job analysis) and its place in the workflow process of the larger work unit (through workflow analysis). By having detailed knowledge of the tasks that are performed in the work unit and the job, the manager then has many alternative ways to design the job.

Job Design Features

Job design is a critical factor influencing employee well-being, attitudes, and behaviors (Panatik, O’Driscoll, & Anderson, 2011). Emphasizes the relationship between job design and employee motivation, highlighting the importance of understanding the mediational mechanisms that produce the motivational effects of core job design characteristics. Moreover, the impact of job satisfaction on turnover intention varies between the public and private sectors, suggesting the need to consider organizational context in job redesign efforts (Wang Y, Yang, & Wang K, 2012). Additionally, psychological capital has been found to negatively affect job burnout, indicating the significance of psychological factors in job design (Li, Wu, Yan, Chen, & Wang, 2019). The JD-R model further supports this by demonstrating that high job resources and low job demands predict employee well-being across different occupation (Lee, 2019). Furthermore, integrating ergonomic knowledge into workplace design has been shown to lead to healthier and more effective workplace designs (Hall-Andersen, Neumann, & Broberg, 2016). This is crucial as traditional production work practices often overlook task variability in job design and assessment, highlighting the need for a new approach to ergonomic physical risk evaluation in multi-purpose workplaces (Lasota, 2020).

Effective Job Design

The interest in job design has a long history. Early writings focused on how the division of labor could increase worker efficiency and productivity (Babbage, 1835; Smith, 1776). The first systematic treatment of the subject was undertaken in the early 20th century by Gilbreth (1911) and Taylor (1911), who focused on specialization and simplification in an attempt to maximize worker efficiency. However, one of the problems with designing work to maximize efficiency is that it can lead to decreased employee satisfaction, increased turnover, absenteeism, and difficulties in managing employees in simplified jobs. (Stephen E. Humphrey, 2007), Specialization and task simplification formed the basis of classical industrial engineering, which seeks the simplest way to structure work to maximize efficiency. Industrial engineering seeks to break down work into simple steps that can be easily repeated, leading to increased productivity and efficiency. The application of industrial engineering to a job typically reduces the complexity of the work, making it so simple that almost anyone can be trained quickly and easily to perform the job. Such jobs tend to be highly specialized and repetitive, which can lead to boredom and routine for workers. (Noe Raymond A., 2016)

In practice, the scientific method traditionally seeks the "best way" to perform a job by conducting time and motion studies to identify the most efficient movements for workers. However, the focus on efficiency alone can create jobs that are so simple and repetitive that workers become bored. Workers who perform these jobs may feel that their work is meaningless. Therefore, most organizations combine industrial engineering with other job design methods, such as socio-psychological analysis, to create jobs that are more interesting and meaningful for workers.

Motivating Job Design

Designing Motivating Jobs When organizations need to compete for employees, rely on knowledgeable workers, or need a workforce that cares about customer satisfaction, a pure focus on efficiency will not achieve human resources goals. Employers also need to ensure that workers have a positive attitude toward their jobs so that they come to work with enthusiasm, commitment, and creativity. To improve job satisfaction, organizations need to design jobs that take into account the factors that make jobs motivating and satisfying for employees. The model that illustrates how to make jobs more motivating is the Job Characteristics Model, developed by Richard Hackman and Greg Oldham. This model describes jobs in terms of five core characteristics. (Noe Raymond A., 2016)

The Job Characteristics Model argues that job characteristics are primarily associated with increased job satisfaction, motivation, and work performance. More specifically, they hypothesized that five core job characteristics (skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback)

• Skill variety: The extent to which a job requires the use of a variety of skills and talents.

• Definition of Task: The extent to which a job requires the completion of all of its components from beginning to end to achieve tangible results. In this regard, Gibson and others have shown that individuals who complete the practices of their jobs are more likely to increase their levels of motivation and reinforce it. Based on this, such a motivational trait and its impact on individual behavior can be considered a form of self-reward.

• Meaning of Task: The extent to which a job has a strong impact on the lives of individuals, whether within or outside the organization. On this basis, an employee who performs his job in the field of aviation, for example, will perceive it positively compared to an employee who performs his job in a less important field, even if the levels of skills and abilities required are similar. (Zhang, 2020)

• Independence: The extent to which a job includes freedom and independence in its programming and the determination of the methods for achieving it. When freedom is granted to an employee in their workplace, they will likely realize the results obtained through their efforts, initiatives, and decisions. In such situations, the employee can feel responsible for success or failure. A recent study by LRN published by the World Economic Forum in Davos found that companies whose employees reported "high levels of freedom" were more than 10 to 20 times more likely to outperform companies with low levels of freedom.

In a study using data from the Workplace Employment Relations Survey conducted in the United Kingdom in 2004 and 2005 (12,836 employees and 1,190 managers), it was found that job autonomy was more strongly associated with mental well-being and organizational commitment in organizations with competitive quality. (Searcy, 2012)

Cordory confirmed three dimensions that fall within job autonomy, which are:

➢ Style of autonomy: The extent of freedom of action enjoyed by the employee in terms of quantity of production, variety of methods for performing tasks, planning, deadlines for completing tasks, and the choice of methods for their performance compared to the specified method for implementing tasks.

➢ Timing of autonomy: The extent of influence enjoyed by the employee in terms of scheduling work, sequencing work tasks, making decisions about the beginning and completion of tasks, and setting the pace of work compared to the specified timeline.

➢ Authority in determining performance goals: The extent of authority enjoyed by the employee in terms of setting challenging goals, performance evaluation, and providing feedback compared to the specified method in this framework.

➢ Feedback: Feedback is the amount of explicit and specific information that an individual receives regarding their performance. When an employee receives feedback on their work practices, it assists them in rectifying errors and bolstering their motivation to work. Consequently, in the absence of this characteristic within the work or job itself, individuals are likely to be unable to determine the accuracy and appropriateness of their responses to work stimuli.

Workers crave feedback because it helps them perform better. In a joint study published in the Harvard Business Review, 72% of employees said they believed their performance would improve if their managers provided corrective feedback. Employees do not just want to be patted on the back and told, "Good job." Employees want the truth. They want to know: How can I be better? What can I change or improve? In fact, in this same study, 57% of respondents preferred corrective feedback over praise and recognition by a margin of 43%.

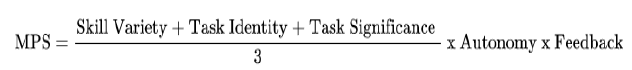

Figure 1 The Contribution of Job Characteristics to Motivation

Source: (Noe, Hollenbeck, Gerhart, & Wright, 2016, p. 111)

The five previous characteristics affect three critical psychological states (experienced meaningfulness of work, responsibility for work outcomes, and knowledge of actual results of work activities), which in turn affect work outcomes (intrinsic motivation, job satisfaction, general job satisfaction, work effectiveness, and absence from work). Finally, the model states that the five core job characteristics can be combined into a single Motivation Potential Score (MPS) index that reflects the job's overall potential to influence the individual's feelings and behaviors. The formula for MPS is as follows: (Yitzhak Fried, 1987)

Ergonomic (Healthy) Job Design

Occupational health research has shown that work-related risk factors affect the physical and mental health of employees, their performance, and their ability to work. To design healthy workplaces, a correct and comprehensive assessment of potential work-related risk factors is needed.

In 2017 an analytical study of 37 studies, titled "Can Work Make You Mentally Ill?" suggested that certain types of work may increase the risk of common mental disorders. Three work-related factors were identified to explain how work can contribute to the development of depression and/or anxiety: « imbalanced work design, job insecurity, and lack of value and respect in the workplace. »

These factors include high job demands, low job control, high effort-reward imbalance, low relational justice, low procedural justice, role overload, bullying, and low social support in the workplace, which are all associated with an increased risk of common mental health problems. (Harvey Samuel B, 2017). a well-designed workplace can also improve the usability of products, equipment, systems, and facilities that facilitate the efficient and effective execution of tasks and achieve ease of use of different workplace elements. Ergonomic workplace design will ultimately lead to improved productivity and reduced production costs with better anticipation and management of production and operating costs over the product life cycle.

Most importantly, employers are also legally responsible for their compliance with local occupational safety and health regulations. a comfortable and safer workplace creates a good environment for employees. If a company is committed to creating a safe and healthy work culture, it will lead to improved performance and well-being of employees alike. (Bagnara S., 2018)

Job Design Models

Job Enrichment

Job enrichment is a style of job design that increases and diversifies the tasks, activities, and responsibilities of individuals, which helps to maximize their roles. Enrichment strategies generate richer job positions, resulting in a greater awareness of the importance of the task to be achieved, improved employee motivation, and a boost of energy and enthusiasm in the employee's job. In short, enriching work positions will improve employee responsibility towards the company.

Job enrichment, which was strongly advocated by Frederick Herzberg, consists of fundamental changes in the content and level of job responsibility to offer greater challenges to the employee. Job enrichment provides a vertical expansion of responsibilities. The employee has the opportunity to derive a sense of accomplishment, appreciation, responsibility, and personal growth in the performance of the job. Although job enrichment programs do not always achieve positive results, they have often led to improvements in job performance and the level of employee satisfaction in many organizations. Today, job enrichment is moving towards the team level, as more teams become independent or self-managed. (Martocchio, 2016)

Job Expansion

There is a clear distinction between job enrichment and job expansion. Job expansion is defined as increasing the number of tasks that an employee performs, with all tasks at the same level of responsibility. Job expansion involves providing greater variety for the employee. For example, instead of knowing how to operate only one machine, a person is taught to operate two or even three machines, but no higher level of responsibility is required. Skilled workers may become increasingly important as fewer workers are needed due to limited budgets. Some employers have found that providing job expansion opportunities improves employee engagement and prevents burnout.

Job Rotation

Job rotation is defined as the transfer of employees between different positions and tasks, each of which requires different skills and responsibilities. Job rotation systems have been implemented to ensure workforce flexibility in assembly lines and to increase productivity, as well as to reduce monotony and boredom for factory workers who perform repetitive tasks, in an attempt to boost their job satisfaction and motivation.

Workplace diversification is a structured approach to employee development that involves strategically transitioning individuals from one position to another within an organization. This practice aims to expand their skill set, enhance their comprehension of various business functions, and foster increased adaptability and versatility. Upper-level roles often demand a comprehensive knowledge base, which workplace diversification training programs effectively cultivate. By exposing employees to a diverse range of tasks and responsibilities, organizations can enhance productivity, alleviate monotony and absenteeism, and encourage employees to achieve higher performance levels. Additionally, workplace diversification promotes cross-departmental collaboration and strengthens the company's overall operational agility. To ensure the success of workplace diversification initiatives, management should prioritize adequate training and support, allowing each individual to seamlessly transition between roles and fulfill their assigned duties with competence and efficiency. (Jeon Byung, 2016)

Self-managed and Independent Work Teams

The utilization of self-managed teams represents a contemporary organizational model. This concept emerged initially in Britain, spearheaded by an investment institute, where management recognized work teams as an effective catalyst for technological advancement. Scandinavian automotive manufacturing companies have further adopted independent work teams to address the social needs of employees operating within the context of modern technology.

Independent work groups engage in a diverse spectrum of activities and administrative roles. For instance, in automobile manufacturing facilities, individuals collaborate as a cohesive unit to produce vehicles seamlessly, rather than focusing on specialized components.

The formation of independent teams adheres to the following principles:

• Designing Team Tasks: The design of team tasks is one of the most critical factors influencing team success. Tasks should be designed to align with the preferences, motivations, and characteristics of individual workers, fostering high levels of job and organizational satisfaction.

• Team Formation: Teams should be formed based on the availability of performance-relevant skills and knowledge. To enhance team effectiveness, teams must possess proportionate levels of expertise in performing the assigned tasks and maintain a size that enables efficient task execution. Additionally, teams should exhibit a balance of characteristics and skills.

• Establishing and Constructing Team Performance Standards: Team performance standards should be clearly and precisely defined. These standards are often determined by the team members themselves. The actual standard depends on a range of organizational factors, such as the competency and performance control system, the availability of performance training and development programs, and the need for senior management support in providing clear information about job requirements.

The most significant outcomes that can result from implementing the independent work team model include: Increased productivity and reduced wasted time, Self-sustained quality enhancement, and Problem-solving. Equipment and machinery maintenance

Flexible work Schedules

One way that an organization can give employees some say in how they organize their work is to offer flexible work schedules. Depending on the requirements of the organization and individual jobs, organizations may be able to be flexible around employees' hours of work. (Hsu, 2021)

This suggests that these new work arrangements may fundamentally change the characteristics of employees' jobs. When individuals work from home, they are likely to have less face-to-face interaction with supervisors and colleagues than those who work in stand-alone institutions. Instead of face-to-face interaction, individuals working in these alternative arrangements may have more communication with colleagues through new computing technologies (e.g., email, instant messaging, video conferencing, file sharing) and have direct contact with individuals who do not work for the core organization (e.g., family members or individuals working for other companies).

Flexible Work Hour Models

The issue of setting fixed times for starting and ending work is one of the important topics that has been the subject of extensive studies and research by those interested in increasing productivity through better investment in working hours. Indeed, irregular work schedules represent a major problem facing contemporary administrations in both developed and developing countries.

The importance of flexible work schedules stems from their potential to increase the overall productivity of employees. The irregularity of work by some employees may be due to factors beyond their control. Some of these factors may be due to social and family factors, such as a woman's preoccupation with preparing children for school in the morning, which affects her attendance at the scheduled times. Additionally, transportation and its availability may have a negative impact on work. Therefore, it is essential to study this phenomenon that affects performance efficiency and develop useful treatments and solutions.

Workplace flexibility is defined as "the ability of workers to make choices that affect when, where, and how long they participate in work-related tasks". Flexible work arrangements are intended to give employees more control and autonomy over choosing when or where they work; the intent is to provide employees with the resources that allow them to balance their work and home responsibilities. Flextime refers to work scheduling flexibility. We focus on the use of flexible work time, which refers to employees' independent management of start, end, and break times according to their needs. (Noe, Hollenbeck, Gerhart, & Wright, 2016)

Flextime is a scheduling policy that allows full-time employees to choose their start and end times within guidelines set by the organization. Flextime policies may require employees to be at work between certain hours, for example, 10:00 AM and 3:00 PM. Employees work additional hours before or after this period to work a full day. For example, one employee may arrive early in the morning to leave at 3:00 PM. Large amounts of flextime have a significant impact on happiness, with the size effect being as large as the effect of family income, or about as large as increasing one step on self-reported health, such as moving from good health to excellent health. (Okulicz-Kozaryn, (2018)

Job Sharing

Job sharing is a flexible work arrangement that allows two employees to share the duties of one full-time job. This can be beneficial for both employees and employers. Employees can benefit from the ability to have more work-life balance and control over their work schedule. Employers can benefit from reduced employee turnover and absenteeism, as well as the opportunity to tap into a wider pool of talent. However, there are also some drawbacks to job sharing, such as the administrative costs involved and the risk of divided responsibility. Overall, job sharing can be a valuable option for both employees and employers who are looking for a flexible and mutually beneficial work arrangement. (Armstrong, 2012)

Remote work

Remote work, also known as telecommuting, flexible work, and virtual work, is becoming increasingly popular around the world. This work arrangement involves working away from the company's office for a portion of the workweek, typically from home, utilizing technology to conduct work as needed. Remote work has been practiced since the 1970s, but it has grown rapidly in recent years with technological advancements. It is estimated that there are over 25 million remote workers in the United States, and growth rates range from 11 to 30% in many regions around the world. (Timothy D.Golden:, 2021) The COVID-19 pandemic has further accelerated the shift to remote work. In 2020, a large percentage of the world's workforce began working remotely due to lockdowns and social distancing measures. Remote work is characterized by the notion of "bringing work to the workers, rather than workers to the work." This means that workers can choose to work from anywhere with an internet connection, which can provide them with a great deal of flexibility. Remote work has been associated with several advantages for both workers and their organizations. For workers, key benefits include increased autonomy, flexible work hours, and the potential to save time due to reduced or eliminated commuting. Organizations, on the other hand, benefit from cost savings resulting from reduced office space requirements and increased productivity. However, research has also identified several drawbacks associated with remote work, including social isolation, increased stress, burnout, reduced impact, and limited career advancement opportunities. (Anne Igeltjørn, 2020)

Model of Intensive Work Style

This is one of the suitable models for working individuals who wish to work for less than five days per week. Under this model, the working day extends to more than the specified hours, i.e., more than 8 hours to cover the standard workweek rate.

A study of intensive work in the police force indicated that those who work 10-hour shifts have significantly higher work-life quality and have much larger average sleep than those who work 8-hour shifts (Amendola, 2011).

References

Amendola, K. L., Weisburd, D., Hamilton, E. E., Jones, G., & Slipka, M. (2011). An experimental study of compressed work schedules in policing: advantages and disadvantages of various shift lengths. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7, 407-442.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Armstrong, M. (2012). Armstrong's handbook of management and leadership: developing effective people skills for better leadership and management. Kogan Page Publishers.

Bagnara S., T. R. (2018). Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. 6Ws in Ergonomics Workplace Design (p. 824). Springer, Cham.

Clegg, C., & Spencer, C. (2007). A circular and dynamic model of the process of job design. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80(2), 321-339.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dahling, J. J., & Lauricella, T. K. (2017). Linking job design to subjective career success: A test of self-determination theory. Journal of Career Assessment, 25(3), 371-388.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fried, Y., & Ferris, G. R. (1987). The validity of the job characteristics model: A review and meta‐analysis. Personnel psychology, 40(2), 287-322.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Golden, T. D. (2021). Telework and the navigation of work-home boundaries. Organizational Dynamics.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hall-Andersen, L. B., Neumann, P., & Broberg, O. (2016). Integrating ergonomics knowledge into business-driven design projects: The shaping of resource constraints in engineering consultancy. Work, 55(2), 335-346.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Harvey Samuel B, M. M.-S. ( 2017). Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occup Environ Med, 301–310.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hsu, Y. S., Chen, Y. P., & Shaffer, M. A. (2021). Reducing work and home cognitive failures: the roles of workplace flextime use and perceived control. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36, 155-172.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Humphrey, S. E., Nahrgang, J. D., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Integrating motivational, social, and contextual work design features: a meta-analytic summary and theoretical extension of the work design literature. Journal of applied psychology, 92(5), 1332.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Igeltjørn, A., & Habib, L. (2020). Homebased telework as a tool for inclusion? A literature review of telework, disabilities and work-life balance. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Applications and Practice: 14th International Conference, UAHCI 2020, Held as Part of the 22nd HCI International Conference, HCII 2020, Copenhagen, Denmark, July 19–24, 2020, Proceedings, Part II 22 (pp. 420-436). Springer International Publishing.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jeon, I. S., & Jeong, B. Y. (2016). Effect of job rotation types on productivity, accident rate, and satisfaction in the automotive assembly line workers. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries, 26(4), 455-462.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kilic, E., & Kitapci, H. (2023). Cognitive job crafting: an intervening mechanism between intrinsic motivation and affective well-being. Management Research Review, 46(7), 1043-1058.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lasota, A. M. (2020). A new approach to ergonomic physical risk evaluation in multi-purpose workplaces. Tehnički vjesnik, 27(2), 467-474.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lee, J. Y., & Lee, Y. (2018). Job crafting and performance: Literature review and implications for human resource development. Human Resource Development Review, 17(3), 277-313.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lee, Y. (2019). JD-R model on psychological well-being and the moderating effect of job discrimination in the model: Findings from the MIDUS. European Journal of Training and Development, 43(3/4), 232-249.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Li, Y., Guo, W., Armstrong, S. J., Xie, Y. F., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Fostering employee-customer identification: The impact of relational job design. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102832.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Li, Y., Wu, Q., Li, Y., Chen, L., & Wang, X. (2019). Relationships among psychological capital, creative tendency, and job burnout among Chinese nurses. Journal of advanced nursing, 75(12), 3495-3503.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Martocchio, R. W. (2016). Human Resource Management. Pearson Education.

Noe Raymond A., H. J. (2016). fundamentals of Human Resource Management. McGraw-Hill Education.

Noe, R. A., Hollenbeck, J. R., Gerhart, B., & Wright, P. M. (2020). Fundamentals of human resource management. McGraw-Hill.

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A., & Golden, L. (2018). Happiness is flextime. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 13, 355-369.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Panatik, S. A., O'Driscoll, M. P., & Anderson, M. H. (2011). Job demands and work-related psychological responses among Malaysian technical workers: The moderating effects of self-efficacy. Work & Stress, 25(4), 355-370.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Park, R., & Searcy, D. (2012). Job autonomy as a predictor of mental well-being: The moderating role of quality-competitive environment. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27, 305-316.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Siengthai, S., & Pila-Ngarm, P. (2016, August). The interaction effect of job redesign and job satisfaction on employee performance. In Evidence-based HRM: a Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship (Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 162-180). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

van der Voet, J., & Steijn, B. (2021). Relational job characteristics and prosocial motivation: A longitudinal study of youth care professionals. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 41(1), 57-77.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wang, Y. D., Yang, C., & Wang, K. Y. (2012). Comparing public and private employees' job satisfaction and turnover. Public Personnel Management, 41(3), 557-573.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 28-Oct-2023, Manuscript No. AEJ-23-14196; Editor assigned: 31-Oct-2023, PreQC No. AEJ-23- 14196(PQ); Reviewed: 14-Nov-2023, QC No. AEJ-23-14196; Revised: 20-Nov-2023, Manuscript No. AEJ-23- 14196(R); Published: 27-Nov-2023