Research Article: 2020 Vol: 23 Issue: 3

Contemporary Challenges in Entrepreneurial Marketing: Development of a New Pedagogy Model

Tayyab Amjad, School of Business Management, College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Malaysia

Citation Information: Amjad, T. (2020). Contemporary challenges in entrepreneurial marketing: Development of a new pedagogy model. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 23(3).

Abstract

Entrepreneurial marketing (EM) in SMEs is greatly different than the traditional marketing in large organizations. The higher education institutions generally instruct traditional marketing through orthodox and conventional teaching pedagogies. In consequence, the literature highlights the graduate entrepreneurs struggling in EM during the start-up phases of their small and medium sized entrepreneurial ventures, which is also causing many of them to fail and unable to contribute to the economy. To address this contemporary problem, the current study has used multiple case studies and triangulated its findings with a focus group discussion. The study has explored the EM challenges during the start-up phase faced by the graduate entrepreneurs who have exposure to both, higher education and practical EM experiences. After the rigorous analysis, four contemporary EM challenges due to the pedagogical gaps in entrepreneurship education are discovered. To overcome these challenges, a practical model of EM pedagogy has been developed that is grounded in, the recent entrepreneurship education literature; and the recommendations from the graduate entrepreneurs as well. The EM pedagogy model is practically implementable at business schools worldwide to produce high quality graduate entrepreneurs in the future, which are well-skilled to overcome EM challenges and survive.

Keywords

Entrepreneurial Marketing, Entrepreneurship Education, Graduate Entrepreneurs, Multiple Case Study, Pedagogy.

Introduction

Economic growth through entrepreneurship development is a key concern globally (Ha & Hoa, 2018; Ogbari et al., 2019). Many countries are taking a range of initiatives to develop entrepreneurship in their economies (see Barba-Sánchez et al., 2019; Otchia, 2019). This is because in today’s era of artificial intelligence and automation, entrepreneurship remains the only source of consistent job creation (Bakhtiari, 2017). Entrepreneurs create small and medium enterprises (SMEs), through which they offer new products and services and achieve greater economic freedom. SME entrepreneurs also get involved in exports which is an important ingredient of economic development since it provides access to greater markets and leads to currency inflows.

Jutla et al. (2002) state that 80 percent of global economic growth derives from SMEs, on the other hand, literature highlights that the greatest challenge faced by the SME entrepreneurs is the ‘marketing’ (Cavusgil & Cavusgil, 2012; Westgren & Wuebker, 2019). This is because the markets today are more open and global than a couple of decades ago and the customers have free choices to use modern tools for accessing global markets. This brings many challenges for the entrepreneurs which include high competition, complexity in coordinating marketing strategies, uncertainties and high risk (Cavusgil & Cavusgil, 2012; Westgren & Wuebker, 2019).

Due to lack of many kinds of resources, marketing in SMEs is much different than marketing in large organizations (Moriarty et al., 2008). Kraus et al. (2010) explain it as “marketing with an entrepreneurial mindset” also known as “entrepreneurial marketing” (EM) (p. 1). Unlike large organization’s traditional marketing (TM), EM considers SME’s unique business environment, characteristics of entrepreneur (such as, skills and abilities) and restrained resources (O’Dwyer et al., 2009). Since EM is dominantly a problematic area for SME entrepreneurs, and different than large organization’s TM, it makes much relevant to see the role and efforts of higher education institutions (HEIs) worldwide to recognize and acknowledge these problems and differences, as HEIs could play a vital role for the development of entrepreneurship in the economy (Ncanywa, 2019).

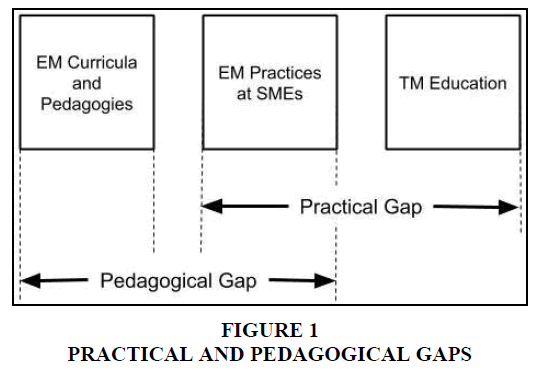

Marketing theories at business schools (BSs) are generally taught from conventional marketing textbooks (e.g., Brassington & Pettitt, 2007; Jobber, 2009; Kotler et al., 2008) which focus on marketing activities such as planning and implementation of marketing mix (4Ps and 7Ps). Such TM theories or models have completely ignored many unique features of SMEs. Thus, the base of what educational institutions teach students about marketing conventionally use examples from large organizations (e.g., Proctor and Gamble, Microsoft, and Starbucks) where marketing expertise and resources are abundant. Hence, it is argued that TM definitions, theories and models in conventional textbooks does not apply to the context of SMEs (Alabduljader et al., 2018; Moriarty et al., 2008). Figure 1 is illustrating this practical gap.

Entrepreneurship education (EE) at HEIs is still in an emerging phase as it has not been long ago since the HEIs have acknowledged entrepreneurship as an exclusive field of education (Manimala, 2017). Therefore, along with the practical gap, there are wide pedagogical gaps exist as well in the domain of EM (Amjad et al., 2020b). Due to this, the graduates from HEIs are struggling to perform marketing functions in their SMEs (Hanage et al., 2016; Mintzberg, 2009; Rousseau, 2012), so much so that it is leading some of them towards entrepreneur failure as well (Garo, 2017; Molin & Sjöberg, 2017; Shahbani et al., 2017). Figure 1 below is illustrating both practical and pedagogical gaps in the domain of EM:

Considering the above gaps, the aim of this contemporary research was to develop an EM pedagogy model which is practically implementable at BSs worldwide. This has been done by identifying the EM challenges faced by the graduate entrepreneurs during the start-up phase of their SME ventures. Focusing of the EM challenges, the pedagogy model developed in the current study has incorporated the recent EE literature as well as recommendations from the graduate entrepreneurs as they have the exposure to both higher education and practical EM experiences. The rationale of focusing particularly on the start-up phase is the high rate of entrepreneurial failures during this phase (SBA, 2019).

Theoretical Background

Since, SME entrepreneurs practice marketing with an ‘entrepreneurial’ mindset (Kraus et al., 2010), it raises the question that how ‘entrepreneurial’ marketing is different from traditional marketing (TM) practiced in large organizations? To answer this, Stokes (2000) explains that TM follows top-down approach, i.e., it starts with the formal market research, followed by segmentation and choosing target markets, and then positioning the product or service using communication tools. It is mainly practiced by large organizations that have plenty of financial resources to conduct various costly activities like formal market research and mass promotions. On the other hand, SMEs are generally constrained with many types of resources, such as, financial and technical expertise, that makes the top-down marketing approach not much suitable for them. Therefore, SME entrepreneurs commonly practice EM which follows a bottom-up approach. Using this approach, the entrepreneurs first choose their target market. Afterwards, they get to know about the needs and demands of their targeted customers through personal relations, and subsequently, serve them in the best possible ways (Stokes, 2000). This approach does not involve costly activities like formal market research or mass promotions. The SME entrepreneurs however rely heavily on their personal networks to collect all types of information (e.g., customers’ needs; or product or service feedback); and for product or service promotion (i.e., through word of mouth) (Copley, 2013). Thus, EM is informal, low-cost and ad hoc in nature as compared to the TM which is more formal and costlier.

Generally, the literature on pedagogic approaches in EE highlight that the current pedagogies are ineffective in matching graduates’ skill expectations with their skill acquisition (Barba-Sánchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, 2018; Ustyuzhina et al., 2019), and therefore, a new approach is needed focusing in SME context (Ahmad & Buchanan, 2015; Alabduljader et al., 2018). Alabduljader et al. (2018) argue that the BSs are having a lack of focus on development of SME oriented curricula, and therefore, recommend to upgrade EE. Similar to these arguments, many researches specifically on EM also show wide pedagogical gaps in the domain and argue that entrepreneurial SMEs often have different marketing behavior than that of the archetypal textbook approaches (Resnick et al., 2011; Resnick et al., 2016; Amjad et al., 2020b; 2020c).

Overviewing the program structures in BSs worldwide, EM is generally not the part of business administration programs. However, for entrepreneurship programs, EM is a well-recognized subject (Amjad et al., 2020c). Despite that, there is the need for pedagogical upgrades in EM as this domain is still emerging (Amjad et al., 2020b). Thus, currently taught EM within entrepreneurship programs and its teaching pedagogies need to be developed further. This ignites the purpose of the current study to develop a suitable pedagogical model based on the contemporary EM challenges faced by the entrepreneurs, so that the issues of entrepreneurial struggle and failure could be addressed. This would ultimately result in the development of entrepreneurship and economic growth.

Theoretical Lens of Entrepreneurial Marketing

The most common definition of EM found in the literature is given by Morris et al. (2002), who define EM as “the proactive identification and exploitation of opportunities for acquiring and retaining profitable customers through innovative approaches to risk management, resource leveraging and value creation” (p. 5). The term ‘EM’ is commonly used to describe the marketing undertaken by SMEs, often at start-up or early growth phase (Morris et al., 2002; Martin, 2009). As SMEs during the start-up and early growth phases mostly have limited financial and human capitals, thus, it requires creative marketing tactics including heavy use of personal networks by the entrepreneurs (Morris et al., 2002; Martin, 2009; Jost, 2019).

According to Morris et al. (2002), EM has seven dimensions: 1) Proactiveness, i.e., when an entrepreneur or firm behaves like an agent of change and creates a new market by offering new products or services (Lumpkin & Dess, 2001); 2) Opportunity driven, i.e., continuous recognition and pursuit of opportunity without regard to resources controlled; 3) Risk management, whereby an entrepreneur stays in comfort with random variance and ambiguity; 4) Innovation focused, that promotes new and different solutions and acting of the firm as an invention factory; 5) Customer intensity, i.e., the reinforcement of passion for the customer where an entrepreneur acts as an agent for the customer; 6) Resource leveraging, i.e., doing more with limited resources; and, 7) Value creation, i.e., the ratio between the benefits and cost (Kotler, 2001).

There is a wide range of EM literature (e.g., Amjad et al., 2020a; Kurgun et al., 2011) that has used the seven dimensions of EM as a major theoretical lens. Following Kurgun et al. (2011), the current research has used the seven EM dimensions as the interview protocol to explore the EM challenges in SMEs. Thus, the answers obtained for each dimension were automatically related to EM, and in this way, the researcher became able to encompass the whole phenomenon of EM from all possible dimensions.

Methods

As this research aims to explore the phenomenon of EM in depth, therefore, the multiple case study method is the most suitable because the case studies allow in-depth understanding of phenomenon in an exploratory research (Yin, 2009). Yin (2003) defines case study as, “an empirical enquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident” (p. 18). Yin (2003) also suggests that the case study approach is much useful if the contextual conditions are highly pertinent to the phenomenon of the study. Case studies normally accommodate much more qualitative than quantitative data. Therefore, some concerns about generalizability and external validity from the case study findings are usually expressed due to the small sample size. Tsang (2014) however argue that the case study has a stronger ability to make theoretical generalizations than the quantitative approaches. Unlike quantitative approaches, where measures of validity and reliability are more often related, the qualitative research calls on other approaches to ensure the rigor. For instance, for analysis of case studies, it is recommended to make use of transferability and comparability criteria (Chreim et al., 2007; Lincoln & Guba, 2002), and therefore, these have been followed in the current research.

The current study is also using in-depth focus group discussion to triangulate all the findings of the case studies (Denzin, 1978), also called as methodological triangulation (Fusch et al., 2018). Since, EM is informal and ad hoc in nature (Franco et al., 2014), therefore, it is practiced more in the developing economies where macroeconomic indicators are unstable (Hameed et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2015) resulting greater challenges for entrepreneurs as compared to the developed economies. Therefore, the current study has been conducted in a developing country, i.e., Pakistan, to get deeper insights regarding the contemporary EM challenges. Due to obtaining deeper insights and widest range of EM challenges, the final outcome of the current study (i.e., the EM pedagogy model) is implementable worldwide.

Following the theory of saturation (Fusch & Ness, 2015), four graduate entrepreneurs were chosen who are currently the owners and managers of SMEs. All of them have exposure to higher education, entrepreneurial start-up and EM experiences in their SMEs, and have survived the business start-up phases successfully. Thus, as the information rich individuals in their respective firms, they have the role of ‘key informants’ in this study (Kumar et al., 1993). Considering the fact that such highly specialized graduate entrepreneurs profitably running their SME ventures are rarely found that could have in-depth conceptual discussions, this is another reason for choosing multiple case study method because it allows to have fewer number of firms and in-depth investigation of the phenomenon of study (Yin, 2009). For generalizability and comparability of the results through firm’s selection, the firms were selected from two different sectors and industries, that is, health and fitness (service); and flour milling (manufacturing).

For the focus group discussion, Morgan (1996) suggests that if the discussion is general in nature, then the greater number of participants are advisable, but for the in-depth discussion about the studying phenomenon, the smaller number of participants are suitable because of the high level of involvement from each participant. The participants in the smaller groups can easily dive into the depth of the phenomenon and share their useful experiences and knowledge. In smaller groups, the moderator could also keep the discussion on track and extremely focused on the studying phenomenon with ease. Hence, the current study aiming at the in-depth focus group discussion chose two ex-entrepreneurs as key informants, one, from the health and fitness (service) industry and the other from the flour milling (manufacturing) industry. These ex-entrepreneurs possess all the same qualities and experiences as of the case study entrepreneurs with the only difference that the focus group participants have not survived from the EM challenges during the start-up phases of their ventures, and thus, taken the exit from the markets.

The Case SMEs

The first SME (firm A) is a health and fitness center, that is, a fitness institute that provides the services of gym, CrossFit training studio, outdoor boot camping, home fitness, and nutritional supplements trading. It is owned by the graduate entrepreneur A (geA) who is a lifestyle entrepreneur. After completing his postgraduate studies, he followed his lifelong passion in the health and fitness industry by taking employment in a top health and fitness center in Lahore, Pakistan as a fitness trainer, and from there, he also completed his first-level fitness certification. After gaining valuable experience of fitness training for few years, he took the decision to start his own health and fitness center in 2016. He chose a newly developed posh location nearby his home, where one traditional gym was already operating. Deciding to differentiate, he launched a CrossFit training studio that offered a totally new type of services in that town. Initially the offered services’ awareness among the targeted audience was almost none. He made plentiful efforts to promote and spread awareness about his services to the audience for the first nine months but failed to convince most of them that the CrossFit style training is as effective and suitable for them as the traditional gym workout. Eventually that made him to make more investment and expand his business by adding a traditional gym alongside the CrossFit training studio to gain more acceptance among the targeted audience. This strategic decision helped him survive and grow his clientele.

At present, personally the geA is a celebrity trainer as well as a guest speaker/trainer who has been invited many times on TV channels. Other than his first-level fitness certification during his job, he is also certified as a physical trainer by the Pakistan Cricket Board during his venture start-up phase. The firm A currently employs 20 to 25 employees including fitness trainers, doctors, nutritionists, marketers and supporting staff, and the geA being experienced and a fitness expert holds the position of Master Trainer.

The second SME (firm B) is another health and fitness center that provides the services of the gym, CrossFit training studio, outdoor boot camping, fitness business consultancy, fitness machinery and equipment trading, and nutritional supplements trading. It is owned by the graduate entrepreneur B (geB) who is an opportunity entrepreneur. Unlike the firm A, firm B is not a fitness institute. The geB started his business in 2013 soon after completing his graduation, when he found an investment opportunity in a newly developed posh location. He joined hands with an investment partner to finance his new business. Unlike geA, the geB have not gained any experience in the health and fitness industry and neither achieved any fitness training certification personally before the start-up.

Due to lack of industry experience, he purchased locally manufactured gym machinery which was having substandard quality, at start-up. After three years, due to the consistent dissatisfaction from his clients, he decided to replace the complete gym machinery by importing the new which is having superior quality. This strategic decision helped him gain more acceptability among his targeted audience and grow his clientele. The firm B currently employs 17 to 20 employees including fitness trainers, nutritionists, and marketers and supporting staff, and the geB is holding the position of Manager in his firm.

The third SME (firm C) is a manufacturing business, i.e., a flour mill operated by the graduate entrepreneur C (geC), who is an opportunity entrepreneur and has started his business operations in 2017 (Yang & Gabrielsson, 2017). After his postgraduate degree, he worked as an operations manager at a renowned flour mill. There he was assigned a wide range of professional duties that include managing operations and marketing. After few years, he came across an opportunity to take over an already established and operational flour mill on a rental contract. Thus, to become self-employed and grow his income, he exploited the opportunity well. At the time of making the contract, the geC was aware of extremely competitive market conditions and how difficult it could be the launching of a new brand in wheat products. Therefore, in the contract, he also bought the rights to use the previously used brand names of all the products, by that flour mill. Due to this strategic decision, he achieved a great advantage of selling his wheat products with an already accepted brand name in the market, which helped him survive the start-up phase.

The firm C currently employs 60 to 70 employees that includes permanent employees which are categorized as management staff, technical staff, and drivers; and contractual employees which are categorized as labor. The firm C’s product range includes regular flour, special flour, baking flour, fine flour, semolina, and bran. The main raw material for the firm C is wheat. Until present, the firm C does not have a broad network of agricultural land owners and wheat traders, thus, the geC is still working to grow his network in backward supply chain.

The fourth SME (firm D) is another flour mill operated by the graduate entrepreneur D (geD) who is a family entrepreneur. After completing his postgraduate education, he joined his brothers as a business partner to start a new flour mill in 2005. He has the family owned land in Lahore, Pakistan, where he established the flour mills by constructing a new building and installing the second-hand machinery for the production. Although the geD never had the experience in flour milling industry at the time of his start-up, he had the experience in the fields of marketing and retailing.

The firm D currently employs 70 to 80 employees that includes permanent employees which are categorized as management staff, technical staff, and drivers; and contractual employees which are categorized as labor. The firm D’s product range includes regular flour, whole wheat flour, special flour, maida flour, fine flour, semolina, and bran. The main raw material for the firm D is wheat. Currently, the firm D has an established network of agricultural land owners and wheat traders from two provinces, Punjab and Sindh.

The Focus Group Participants

The first focus group participant (fgpA) belongs to the health and fitness industry, who started his health and fitness center in 2015 that used to provide the services of the gym and CrossFit training studio. Prior to that, he completed his postgraduate education and worked at various management positions in few firms. However, he never had work experience in the health and fitness industry and neither had the personal certification of a fitness trainer. Consequently, he could not create legitimacy among his targeted audience and struggled with EM challenges during the start-up phase, and after more than a year, he eventually took an exit from the market with a substantial financial loss.

The second focus group participant (fgpB) belongs to the flour milling industry. His career journey is similar to geC. After completing his postgraduate education, he worked as an export and marketing manager in a flour mill for a few years. While doing that, he came across an opportunity to take over an already running flour mill on a rental contract in 2013. He exploited that opportunity and quitted his job. He signed a three years contract to operate a running flour mill which already had employees and a customer network. Despite these advantages, he could not grow the customer base because of the highly competitive market conditions. The continuous EM challenges eventually made him to terminate the contract after two years, to save himself from loss.

Data Gathering

Following Kurgun et al. (2011), the seven dimensions of EM given by Morris et al. (2002), were used as the interview protocol as well as the focus group discussion guideline. As a result, the information gathered about each dimension came out to be a fundamental part of the EM challenges. Therefore, the interview questions and structure were guaranteed to grasp the EM phenomenon completely from all theoretical and conceptual perspectives.

The on-field process started with the detailed presentations during the first meeting with each key informant explaining the EM dimensions and its philosophy to them. As all the key informants had to recall their EM experiences from the past, thus, considering the factor of time biasness, they were given ample time to recall the relevant experiences and challenges about each of the EM dimensions since the beginning of their ventures. In the subsequent meetings, semi structured interviews were conducted (Cohen & Crabtree, 2006), during which open ended questions were asked to the graduate entrepreneurs about the EM challenges during their start-ups (see Appendix). All responses were triangulated from internal sources (e.g., employees, archival data and observations) during the data gathering (Yin, 2014), and after reaching to the findings, all findings were externally triangulated with the focus group discussion, also known as methodological triangulation (Denzin, 1978). Before the focus group discussion, the inclusion of new cases was stopped after reaching at the point of saturation (Fusch & Ness, 2015). All the responses were audio recorded for transcription. Detailed observations and archival data were also gathered, and online social media pages were examined thoroughly, for the triangulation through different internal sources (Yin, 2014). The whole data gathering process included multiple site visits of each firm, and in the cases of manufacturing firms, the on-field data gathering was extended to their complete supply chains.

Data Analysis

Analysis of the data was first carried out manually along with the data gathering process, and later, to ensure the results, the qualitative data analysis software ATLAS.ti was used (Lewis, 2004). Interview transcripts, field notes, social media posts and all the key documents were imported into the software. The analysis started with open coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1990), whereby each line was constantly compared within the data to find the other chunks with the similar meanings. After that, all the related chunks were combined using axial coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1990), and the foregrounded themes indicated four core EM challenges, that qualify to be categorized under educational challenges by a process called selective coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). All the findings were triangulated with the focus group discussion data to ensure the rigor along with the analysis process (Boyatzis, 1998).

Results

The data analysis has suggested four major themes that were: 1) Entrepreneurial negotiation skill; 2) Industry and market research skills; 3) Entrepreneurial networking skill; and, 4) Employee branding and training skills. The following sections below detail each of the key findings:

Entrepreneurial Negotiation Skill

Personal communication is one of the most important entrepreneurial skills (Pathak, 2019), and has been found most challenging for all of the key informants as they have experienced this challenge most frequently. In developing economies, there is a wide range of antecedents that could create or involve communicative issues. An orthodox Islamic society like Pakistan usually follows the philosophy of gender segregation (Khan et al., 2014), that shows in their culture and people's behavior as well. In the case of firm A, the geA has also experienced this challenge when some of his female clients feel reluctant to workout in the presence of male fitness trainers. It does require a great deal of entrepreneurial negotiation skill to convince and retain the female clients and he is still continuing to struggle in communicating on this issue with his clients.

The geA has also struggled in spreading the awareness of his new services among his targeted audience. He started the CrossFit training studio in the beginning that was a new service/facility in the town, so the targeted audience does not have any knowledge about the service. Despite being a graduate in business and marketing, he could not negotiate to convince the targeted audience to buy his services. After nine months of struggle with the communication skill, this eventually made him rent another property and open a traditional gym alongside the CrossFit training studio to gain more acceptability and attract more clients. Facing a similar challenge in firm B, the geB has also experienced a great difficulty in communicating the value of his CrossFit training service as his regular gym clients were not willing to pay extra price for the new service. In those critical situations during the start-up phase, he found himself lacking in negotiation skill that was required to convince his clients.

In the case of firm C, the geC has faced the challenge of entrepreneurial negotiation during the start-up when he needed to engage substantially big flour dealers in his supply chain. He struggled due to the weak negotiation skill and could not make the dealers agree on his terms, and in some situations, could not convince them at all. On another occasion, when the geC introduced a new stock keeping unit, he could not successfully negotiate to convince the retailers to accept that, and consequently, that increased his marketing costs to promote it through other means. In a similar example of firm D, the geD has also experienced a tough time in negotiating when he introduced a new product, that is, the refined flour. His targeted customers mainly refused to accept that, and he found himself unable to negotiate to convince the retailers to get more shelf space for his new product.

The challenge of weak entrepreneurial negotiation skill is found to get worse in the business journeys of focus group participants. For fgpA, he was unable to negotiate with his property owner about the starting date of his rental contract. This caused him to face massive rental loss because of the high rents in the posh locations. Whereas for fgpB, although he had the network of customers, he extremely lacked in the entrepreneurial negotiation skill so much so that he could not even retain his existing customers. All of the big dealers on which he was relying for the majority of his sales, left him during the off-peak season of sales.

For all key informants, at probing further about the reasons that in spite of having higher education, why they have experienced such communication challenges, all of them highlighted the gaps in the education system that have not made them learn and enhance the professional communication, and particularly the practical negotiation skill. Accordingly, all the key informants have recommended the pedagogic upgrades in the EE.

Industry and Market Research Skills

In-depth knowledge of industry and market holds the key importance in starting a new venture (Melancon et al., 2010). Entrepreneurs sometimes get this knowledge through working in other firms within that industry prior to starting their own business ventures (Quatraro & Vivarelli, 2015). Before starting his own venture, the geA has also gained valuable experience and learned how to deliver the quality services by working for another health and fitness firm. Yet, he was found unknown from the technical constraints that occur in the process of starting a new venture. At the time of adding the gym in his firm, he ordered the complete gym machinery from China. Due to lack of industry and market research skills, he could not conduct a thorough research regarding the cost, customs duties, customs procedures, estimated delivery time and transportation hurdles. Consequently, he endured a massive financial loss in the shape of property rent of four months (i.e., for the property he took on rent for adding the traditional gym) as the machinery and equipment arrived later than expected.

Market research is highly useful tactic for the businesses, and its effective use enables firms to become more customer oriented, and it also improves the chances of succeeding in today's highly competitive markets (Wee, 2001). This is a major problematic area found in the studied cases whereby the graduate entrepreneurs are found untrained and to be floundered in understanding the function of market research. In the case of firm A, before starting his venture, when the geA chose the location for his new venture, he found himself lacking in the market research skills. Consequently, after launching his business, he gradually came to know that the population in the surrounding areas is insufficient for a profitable business. A similar weakness could be seen in the case of firm B as well, where the geB could not conduct the market research before launching his business, and therefore, he was unaware of the expected number of clients from his targeted location. After the launch, the population of the surrounding locations was proved to be insufficient in his case as well.

In the case of firm C, with the intention of creating value during the start-up, the geC started making commitments of the fastest delivery of products to his retailers. Contrary to his competitors who deliver the supply after three to four days, the geC promised to deliver within 24 hours. This commitment was not backed by thorough market research as the geC was lacking in the feasibility and cost analysis; and researching skills. Therefore, to fulfil his commitment, he continued to bear much higher than expected costs in the accounts of human resource and transportation.

In the case of firm D, lacking in industry and market research skills, the geD could not conduct survey to choose the most feasible location for setting up the flour mill. Therefore, the geD and his brothers used their family owned land to set up their flour mill which was far away from the main markets of the city. Consequently, when they started the operations, they realized that the transportation cost to deliver the supplies to the city, was exceeding too high affecting negatively to their profitability.

The fgpA admits that he also struggled a great deal due to the weak industry and market research skills. Unaware of the industry trends in the posh areas, he purchased locally manufactured (substandard) machinery for his health and fitness center in a posh location. Consequently, his local machinery was not appreciated by the people of high social class, and that was one of the major reasons of his entrepreneurial failure. On the other hand, unable to calculate the feasibility, the fgpB at the start-up purchased two small trucks of 6000 kg capacity instead of purchasing one big truck of 12000 kg capacity. Consequently, it used to consume more time and fuel to deliver the products to the city as his flour mill was in the outskirts of Lahore. He admits that he could not calculate the feasibility and it created a big challenge for him throughout the life of his venture.

Upon enquiring about the educational experiences at HEIs, in agreement with Nunan (2015), all the key informants have also highlighted the pedagogical weakness regarding the industry and market research skills’ development at the HEIs. In agreement with Piperopoulos & Dimov (2015), all key informants have also made recommendations to the BSs to emphasize practical learning and enhancement of the industry and market research skills among students.

Entrepreneurial Networking Skill

Due to the limited financial resources, SME entrepreneurs incorporate creative marketing strategies that usually include a high use of their personal networks in order to survive (Morris et al., 2002; Martin, 2009; Jost, 2019). Similarly, for the studied firms, the graduate entrepreneurs are required to be actively engaged in entrepreneurial networking, but the entrepreneurial networking skill has been found as one of the core EM challenges in the current study. For example, in the firms C and D, the graduate entrepreneurs have been found facing regulatory constraints while practicing EM. Both entrepreneurs have exploited the opportunities of increasing their sales by joining the provincial government’s ‘subsidized flour’ program. In this program, flour bags are sold at a much lower price (i.e., subsidized price) than the retail market price. Consequently, the sales volume increases and later the government pays back the price difference (i.e., subsidy) to the participant flour mills. While availing this opportunity, both graduate entrepreneurs are encountering the on-site monitoring officials from different government departments. The basic and common role of all monitoring staff is to keep a record of the daily sales and report to their respective government departments, but some of the staff members often extort and demand bribes to report the sales figures correctly. In this context, the geC and geD have confessed that they could not make influential relationships at the higher level of government officials in the concerned departments, as a result, the on-field monitoring staff extort them and demand bribe.

Another example of the firm D is, like most of the SMEs, it also had limited resources at start-up, thus, the geD had to leverage resources, for instance, transportation from outside. At that time, he tried to build new relationships and grow his network but found himself lacking in entrepreneurial networking and relationship building skills. He struggled hard for quite a long time to start new relationships with the transportation firms and competitors, as these could be the two major partners for him to leverage external resources. This is also consistent with Engel et al. (2017), who claim that the entrepreneurs use closer business networks to leverage external resources.

The fgpA has also shared the fact that he was unaware of the importance of networking, and thus, he never tried to create one. Whereas, the fgpB, who already had an established network of customers, could not maintain or grow that. He found himself lacking in the skill of relationship building that contributed towards his exit from the market. This is also in line with the past literature, where a number of studies have shown that business networking capability of entrepreneurs is pivotal for their new venture’s survival and success (Karami & Tang, 2019; Prokop et al., 2019). In addition to highlighting the weaknesses of education system, in line with Kaandorp et al. (2019), the key informants have endorsed the idea that the BSs must provide the platforms for experiential learning to the students, so that they could develop and enhance their entrepreneurial networking skill.

Employee Branding and Training Skills

‘Employee brand’ is the brand image presented to the customers and other organizational stakeholders by employees (Miles et al., 2011). The process through which the employees internalize the desired brand image and project it to customers is known as employee branding (Miles & Mangold, 2004). Employees who are responsible for executing the brand promise (Harris & De Chernatony, 2001) are obligated to deliver consistent service to achieve and maintain the desired identity, image (Vallaster & De Chernatony, 2005) and reputation of the organization (Fitzgerald, 1987). Any failure in delivering the promised service to customers by employees will result in negative perception of customers about the quality of the brand (Sharma et al., 2015). According to Potgieter & Doubell (2018), employee branding improves the profile of the firm and enhances the competitive advantage. Thus, to avoid the negative consequences and to obtain competitive advantage, the desired brand image and the associated brand promise must be elaborated to the employees.

Among the studied cases, the firm A is found to have issues regarding the employee branding and training as the geA reports about the unsupportive behavior of his staff with their clients and the firm’s management. He confessed that he did not know how such human resource issues impact marketing and clients. As he was unaware of how to train his staff, he found himself unable to control his trainers’ behavior. As a consequence, his trainers’ ungroomed behavior was damaging the firm’s clientele.

In the cases of firm C and firm D, both firms mostly hire their employees through close references e.g., existing employees and family. As a result, many of their employees are not suited with the jobs they are doing. The behavior and communication of those employees are totally contrasting with their roles in the firm. The firm also does not have on-job training programs to groom the employees. As a consequence, this often leaves unsatisfied customers when they encounter ungroomed behavior of the marketing and customer serving employees in particular.

The fgpA has also admitted that he had a tough time in dealing with his employees. His fitness trainers in particular were not groomed according to the customers he was targeting. The communication and professionalism were commonly lacking among his employees, and he did not have the employee branding and training skills to groom them according to their professional roles.

The fgpB also endorsed the challenge of weak employee branding and training skills among the graduates by giving his own example when he hired the sales team in his firm. Going to the market with a highly important role, his salesmen totally failed to make any big sales. Moreover, they used to waste crucial time on-field and the fgpB also did not know how to train them to become responsible salesmen. Employee branding and training is a crucial positioning strategy that determines the reputation of a brand. It has two vital components, that is, the employees’ knowledge of the desired brand image and the motivation to project the intended image, which is determined by the employees’ perception of the upholding of the psychological contract by the organization (Miles & Mangold, 2004; Miles et al., 2011).

At probing about the educational approaches used at BSs, the key informants have agreed on the ineffectiveness of current pedagogies. All of them have recommended to upgrade current pedagogical approaches focusing on the practical employee branding and training skills’ enhancement rather than merely understanding the definitions.

Discussion and Practical Implications

Many studies in the entrepreneurship literature have explored the EM practices of firms in their well-established phases but exploring particularly the EM challenges during the start-up phase of business is relatively a new attempt. Moreover, the current study exploring the phenomenon of EM in the educational context is a new attempt in the EE literature as well to bridge the pedagogical gaps in EE. It is argued that due to limited financial and human resources available to SMEs, EM in SMEs is much different than standard marketing in textbooks and the way these are taught at the BSs (Grünhagen & Mishra, 2008). The standard marketing in textbooks were originally developed for large organizations, and those are far apart from the marketing peculiarities of SMEs (Kraus et al., 2007; Grünhagen & Mishra, 2008). Numerous studies also show a clear pedagogical gap in the area and argue that entrepreneurial SMEs generally have different marketing behavior than those of the classic textbook approaches (Resnick et al., 2011; Resnick et al., 2016). Due to this pedagogical gap, the graduates like the four discussed in this paper, are found not to grasp the process of SME marketing; and lack such entrepreneurial skills to a great extent that are required to practically start an SME venture (Rousseau, 2012; Mintzberg, 2009).

Alabduljader et al. (2018) argue that the HEIs are having lack of focus on the development of SME oriented curricula, and therefore, recommend to upgrade EE. They (2018) also spotlight the universities delivering EE using the same teaching pedagogies as the traditional business and marketing education. The pedagogical gap in the EE can also be seen from many practical examples, for instance, overviewing the program structures of BSs worldwide, EM is generally not the part of business administration programs. Whereas, for entrepreneurship programs, EM is a well-recognized subject worldwide (Amjad et al., 2020c). However, upon reviewing their pedagogical structures, it becomes evident that the teaching pedagogies used for EM are similar to the traditional business and marketing programs (i.e., coursework). Therefore, there is the need for pedagogical upgrading in EM as this domain is in an emerging phase as well (Amjad et al., 2020b). According to Piperopoulos & Dimov (2015), entrepreneurship courses should be designed and delivered with the ‘practically oriented’ context and teaching pedagogies because practically oriented programs develop significant entrepreneurial skills that affect highly on the practical outcomes among graduate entrepreneurs. Hence, there is a high need to develop EM pedagogical model in order to substantially fill such pedagogical gaps particularly in EM domain.

Ahmad & Buchanan (2015) argue that rather than solely focusing on functional understanding of entrepreneurship or business (like traditional business coursework), the objectives of strengthening EE at BSs should be reconsidered in such a way as to enhance students’ acquisition of skills and competencies needed to initiate and retain new businesses. In the studied cases, the graduate entrepreneurs are also stressing on practical skill development and sharing the similar recommendations to enhance entrepreneurial negotiation skill, industry and market research skills, entrepreneurial networking skill, and employee branding and training skills. Considering these four weak skills found in the current study due to the pedagogical gap in EM, the BSs worldwide promptly need to upgrade the EM pedagogies so that the issues of business failure among graduates could be minimized. As a result of upgrading the EM pedagogies, high quality and skilled graduate entrepreneurs could be produced in the future, that are better prepared to encounter EM challenges and survive.

Development of EM Pedagogy Model

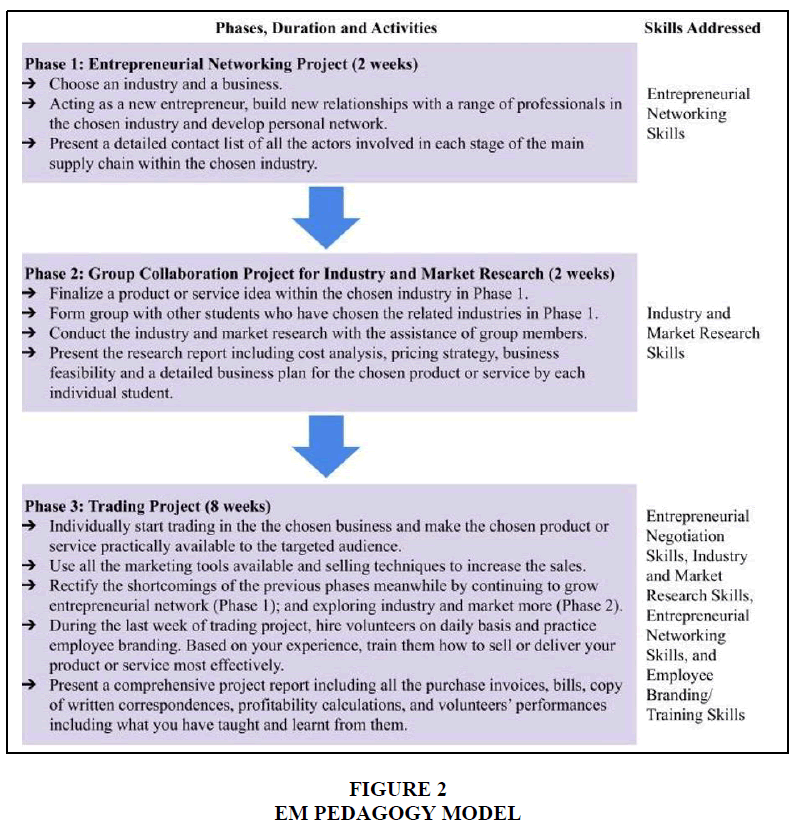

The major objective of the current study was to develop a new model of EM pedagogy that is practically implementable at BSs and should be grounded in the current study’s findings, past EE literature, and the key informants’ recommendations. Many studies in EE literature (e.g., Ferrandiz et al., 2018; Lloyd et al., 2019; Pouratashi & Zamini, 2019) recommend work-based learning pedagogies to be implemented at BSs. Ezeani (2018) finds low skills and technical incompetence; and lack of creativity and innovation among the HEI graduates, and therefore, recommends incorporating skill development and enhancing technical competence in the EE. Ferrandiz et al. (2018) have also emphasized on acquisition of entrepreneurial skills, entrepreneurial learning and co-curricular activities at BSs. Moreover, Nabi et al. (2017) in their review, have highlighted many studies that are emphasizing on intensive experiential programs to be the part of EE. Garo (2017) suggests that the students must have experiential learning and BSs should play the role of a facilitator in order to provide the right pedagogies and appropriate environment to the students to get real experiences and practical skills. Manimala (2017) recommends interdisciplinary programs; entrepreneurship skill development; specialized offerings in entrepreneurship; and real-life entrepreneurial opportunities as part of the pedagogy. In-line with all of the above general recommendations to develop entrepreneurship pedagogies, Smith et al. (2017) more specifically recommend trading projects, group collaboration projects and networking for students. Kaandorp et al. (2020) also suggest that the students must be engaged in entrepreneurial networking during their education at BSs to get experiential learning. Researching experiential learning during the EE, Lloyd et al. (2019) argue that the students should be exposed to the real-life experiences, for example, live cold calling to enhance their selling skills. Such pedagogic approach would enhance the entrepreneurial and technical skill sets in the students. Figure 2 is integrating all the above recommendations of past literature to illustrate the EM pedagogy model which is implementable over a period of 12 weeks (i.e., within one semester).

Besides the past entrepreneurship literature’s recommendations, the EM pedagogy model is precisely based on the empirical findings of the current study and recommendations of all the key informants as well. Explicating that, the model consists of three phases. In the first phase, the entrepreneurial networking skill is targeted where the students would be practically engaged in developing personal entrepreneurial networks (Kaandorp et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2017) as emphasized by the key informants.

In the second phase, the researching and teamwork coordination skills are focused where the students would make group collaborations (Smith et al., 2017) to conduct industry and market research which includes cost analysis, formulating pricing strategy and feasibility analysis, as suggested by all the key informants in the current study. In the third phase of pedagogy model, the positioning, customer targeting, entrepreneurial negotiation skill, and employee branding and training skill, are aimed through a real trading project (Smith et al., 2017). The sole purpose of such project is to make the students learn through experience (Ferrandiz et al., 2018; Garo, 2017; Kaandorp et al., 2019; Lloyd et al. 2019; Piperopoulos & Dimov, 2015; Pouratashi & Zamini, 2019) as recommended by all the key informants. The trading project has purposefully been kept to be accomplished by the students in individual capacity in order to make them practice becoming self-reliant like an autonomous entrepreneur.

The EM pedagogy model in Figure 2 is work-based (Lloyd et al., 2019; Pouratashi & Zamini, 2019; Ferrandiz et al., 2018) with the avenues of practical and experiential learning (Arias et al., 2018; Kaandorp et al., 2020; Piperopoulos & Dimov, 2015) for the skill development (Ezeani, 2018; Ferrandiz et al., 2018; Manimala, 2017; Ahmad & Buchanan, 2015) among the entrepreneurship students. The model also adheres to the recommendation of Kaandorp et al. (2020) to make the students develop entrepreneurial networks during the education, and moreover, it is aimed to provide real-life industry and market research; and trading experiences as well, as suggested by Lloyd et al. (2019); and Manimala (2017). Thus, the above pedagogy model is addressing all the weak skills found in the current study, due to the weak entrepreneurship pedagogies at BSs. Therefore, by implementing this model, the four weak skills found in the current study, i.e., the entrepreneurial negotiation skill, industry and market research skills, entrepreneurial networking skill, and employee branding and training skills could be practically improved among the business students. Zamani & Mohammadi (2018) suggest that upgrading the student learning experience at BSs could not only bridge the pedagogical gap but also encourage a greater number of graduates to become entrepreneurs, hence contributing to the entrepreneurship development and economic growth.

Contributions

Studies using case study method along with the focus group discussion to triangulate their findings are rarely found in the entrepreneurship literature. Thus, the current study makes a significant methodological contribution by using this rare combination of qualitative methods in the entrepreneurship literature. Further, there is a wide range of studies exploring the phenomenon of EM during the established phases of the SMEs, but the studies exploring the EM phenomenon during the start-up phase of business are scant. So, the current study exploring the EM phenomenon during the start-up phase of businesses contributes to the new venture’s literature as well. In the entrepreneurship literature, many studies have explored the EM practices of the SME entrepreneurs, but the current study contributes uniquely by exploring the contemporary EM challenges, which is a new attempt. In the educational context, the studies exploring such contemporary issues of entrepreneurs for upgrading the EE pedagogies are also rarely found in the EE literature. Finally, the development of EM pedagogy model (Figure 2) which is based on both, past EE literature and graduate entrepreneurs’ recommendations and is practically implementable at BSs worldwide, is a major practical contribution of this study.

Practical Implication for Business Schools’ Academic authorities

The training programs at BSs should address ‘how to’ and not just ‘what is’ (Copley, 2013). Therefore, the current study strongly recommends that the practically oriented EM courses must be the part of both, entrepreneurship (focused on SMEs) and traditional business administration (focused on large organizations) programs at BSs. The rationale for this is, first, not all graduates from traditional business programs work in large organizations. Many also work in entrepreneurial SMEs or have their own entrepreneurial ventures (Brizek & Poorani, 2006). Second, besides the SMEs, the relevance of EM is also in large organizations as justified and thoroughly detailed by Lodish et al. (2016) in their book “Marketing that works: How entrepreneurial marketing can add sustainable value to any sized company” (second edition). Moreover, Morrish et al. (2015); and Brizek & Khan (2008) also argue that due to the shrinking resources and technologically savvy consumers, both, the SMEs and large sized organizations need to be entrepreneurial. Thus, making the EM course a part of traditional business administration programs could bridge a major practical gap as identified in the beginning of this paper (Figure 1).

Considering the practical importance of EM in highly competitive, uncertain and risky conditions, especially for the new businesses, EM is becoming inevitable for both small and large organizations. In such case, the business and entrepreneurship students need to learn how to effectively adopt EM in their careers, whether the students opt for entrepreneurship or marketing careers in either SMEs or large organizations. Thus, the EM pedagogy model developed in the current study is significantly useful and must be instantaneously implemented at BSs worldwide. It could certainly help to produce high quality graduate entrepreneurs in the future that are better prepared to face EM challenges and survive, ultimately contributing towards entrepreneurship development and economic growth.

Limitations AD Future Research

By nature, EM is highly social (Martin, 2009), however, the current study has only focused on exploring the contemporary challenges in the context of EE. Thus, there is a need to explore the challenges in EM in the social context as well (e.g., cultural values and consumer behavior) to discover a broader range of EM challenges.

To measure the competence of graduate entrepreneurs and business students, future researchers need to develop quantitative scales to measure the four weak EM skills identified in the current study. Such scales could give a better understanding to the EE policy makers about the level of technical competence in their students for each of the EM skills.

Conclusion

Since, EM in SMEs is greatly different than TM and the way it is taught at business schools, thus, it is causing the graduates of business schools to struggle and even fail in their entrepreneurial careers. Therefore, it has become inevitable in the current times to bridge this gap for the development of entrepreneurship in the economies. The current study has made this attempt by exploring the EM challenges faced by the graduate entrepreneurs in SMEs, and developing a new pedagogy model of EM in the light of those contemporary EM challenges. While doing that, this study has discovered four contemporary EM challenges faced by the graduate entrepreneurs in SMEs that are owned and managed by them. Moreover, for each EM challenge, the valuable pedagogic recommendations have also been gathered from the graduate entrepreneurs. Following their recommendations, and in the light of recent EE literature, a new EM pedagogy model has been developed in the current study, which is practically implementable at business schools over the period of 12 weeks (i.e., within one semester).

Appendix

Interview Questions

Proactive Orientation/Proactiveness

1. What challenges have you faced in proactively making or implementing the decisions during your start-up?

2. Despite having marketing education, why do you think you have experienced these challenges?

3. What solutions have you come up with for overcoming these challenges?

4. What recommendations would you give for business schools to train the prospect entrepreneurs to learn and adopt proactiveness?

Opportunity Driven

1. What challenges have you faced in exploiting opportunities during your start-up?

2. Despite having marketing education, why do you think you have experienced these challenges?

3. What solutions have you come up with for overcoming these challenges?

4. What recommendations would you give for business schools to train the prospect entrepreneurs to learn how to exploit opportunities well?

Risk Taking Orientation/Risk Management

1. What challenges have you faced in risk taking or management during your start-up?

2. Despite having marketing education, why do you think you have experienced these challenges?

3. What solutions have you come up with for overcoming these challenges?

4. What recommendations would you give for business schools to train the prospect entrepreneurs to learn risk management?

Innovation Focused

1. What challenges have you faced in making innovations during your start-up?

2. Despite having marketing education, why do you think you have experienced these challenges?

3. What solutions have you come up with for overcoming these challenges?

4. What recommendations would you give for business schools to train the prospect entrepreneurs to learn and adopt innovation orientation?

Customer Intensity

1. What challenges have you faced in acquiring new customers during your start-up?

2. Despite having marketing education, why do you think you have experienced these challenges?

3. What solutions have you come up with for overcoming these challenges?

4. What recommendations would you give for business schools to train the prospect entrepreneurs to learn how to acquire new customers/markets?

Resource Leveraging

1. What challenges have you faced in leveraging your limited resources during your start-up?

2. Despite having marketing education, why do you think you have experienced these challenges?

3. What solutions have you come up with for overcoming these challenges?

4. What recommendations would you give for business schools to train the prospect entrepreneurs to learn effective resource leveraging?

Value Creation

1. What challenges have you faced in creating value of your product/service during your start-up?

2. Despite having marketing education, why do you think you have experienced these challenges?

3. What solutions have you come up with for overcoming these challenges?

4. What recommendations would you give for business schools to train the prospect entrepreneurs to learn how to create value of a product/service?

References

- Ahmad, S.Z., &amli; Buchanan, R.F. (2015). Entrelireneurshili education in Malaysian universities. Tertiary Education and Management, 21(4), 349-366.

- Alabduljader, N., Ramani, R.S., &amli; Solomon, G.T. (2018). Entrelireneurshili education: A qualitative review of U.S. curricula for steady and high growth liotential ventures. In Annals of Entrelireneurshili Education and liedagogy, 37-57.

- Amjad, T., Abdul Rani, S. H., &amli; Sa’atar, S. (2020c). Entrelireneurshili develoliment and liedagogical galis in entrelireneurial marketing education. The International Journal of Management Education.

- Amjad, T., Abdul Rani, S.H., &amli; Sa’atar, S. (2020a). A new dimension of entrelireneurial marketing and key challenges: A case study from liakistan. SEISENSE Journal of Management, 3(1), 1-14.

- Amjad, T., Abdul Rani, S.H., &amli; Sa’atar, S. (2020b). Entrelireneurial marketing theory: Current develoliments and future research directions. SEISENSE Journal of Management, 3(1), 27-46.

- Arias, E., Barba-Sánchez, V., Carrión, C., &amli; Casado, R. (2018). Enhancing entrelireneurshili education in a master’s degree in comliuter engineering: A liroject-based learning aliliroach. Administrative Sciences, 8(4), 58.

- Bakhtiari, S. (2017). Entrelireneurshili dynamics in Australia: Lessons from micro-data. Retrieved from httlis://industry.gov.au/Office-of-the-Chief-Economist/Research-lialiers/Documents/2017-Research-lialier-5-Entrelireneurshili-Dynamics-in-Australia.lidf

- Barba-Sánchez, V., &amli; Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. (2018). Entrelireneurial intention among engineering students: The role of entrelireneurshili education. Euroliean Research on Management and Business Economics, 24(1), 53-61.

- Barba-Sánchez, V., Arias-Antúnez, E., &amli; Orozco-Barbosa, L. (2019). Smart cities as a source for entrelireneurial oliliortunities: Evidence for Sliain. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 148, 119713.

- Boyatzis, R.E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code develoliment. Sage.

- Brassington, F., &amli; liettitt, S. (2007). lirincililes of marketing. 4th edition, Harlow: FT/lirentice-Hall.

- Brizek, M., &amli; lioorani, A.A. (2006). Making the case for entrelireneurshili: A survey of small business management courses within hosliitality and tourism lirogrammes. Journal of Hosliitality, Leisure, Sliort and Tourism Education, 5(2), 36-47.

- Brizek, M.G., &amli; Khan, M.A. (2008). Understanding corliorate entrelireneurshili theory: A literature review for culinary/Food service academic liractitioners. Journal of Culinary Science and Technology, 6(4), 221-255.

- Cavusgil, S.T., &amli; Cavusgil, E. (2012). Reflections on international marketing: Destructive regeneration and multinational firms. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(2), 202-217.

- Chreim, S., Williams, B.E.B., &amli; Hinings, C.R.B. (2007). Interlevel influences on the reconstruction of lirofessional role identity. Academy of Management, 50(6), 1515-1539.

- Cohen, D., &amli; Crabtree, B. (2006). Semi-structured Interviews.

- Coliley, li. (2013). The need to deliver higher-order skills in the context of marketing in SMEs. Industry and Higher Education, 27(6), 465-476.

- Denzin, N.K. (1978). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. 2nd edition, New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

- Engel, Y., Kaandorli, M., &amli; Elfring, T. (2017). Toward a dynamic lirocess model of entrelireneurial networking under uncertainty. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(1), 35-51.

- Ezeani, E. (2018). Barriers to graduate emliloyment and entrelireneurshili in Nigeria. Journal of Entrelireneurshili in Emerging Economies, 10(3), 428-446.

- Ferrandiz, J., Fidel, li., &amli; Conchado, A. (2018). liromoting entrelireneurial intention through a higher education lirogram integrated in an entrelireneurshili ecosystem. International Journal of Innovation Science, 10(1), 6-21.

- Fitzgerald, T.J. (1987). Understanding the differences and similarities between services and liroducts to exliloit your comlietitive advantage. Journal of Business &amli; Industrial Marketing, 2(3), 29-34.

- Franco, M., de Fátima Santos, M., Ramalho, I., &amli; Nunes, C. (2014). An exliloratory study of entrelireneurial marketing in SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Enterlirise Develoliment, 21(2), 265-283.

- Fusch, L., &amli; Ness, li. (2015). Are we there yet? Saturation in qualitative research. The Qualitative Reliort, 20(9), 1409-1416.

- Fusch, li., Fusch, G.E., &amli; Ness, L.R. (2018). Denzin’s liaradigm Shift: Revisiting Triangulation in Qualitative Research. Journal of Social Change, 10(1), 19-32.

- Garo, E. (2017). Gali between theory and liractice in management education. In Case studies as a teaching tool in management Education (lili. 264-277). IGI Global.

- Grünhagen, M., &amli; Mishra, C.S. (2008). Entrelireneurial and small business marketing: An introduction. Journal of Small Business Management, 46(1), 1-3.

- Ha, N.T.T., &amli; Hoa, L.B. (2018). Evaluating entrelireneurshili lierformance in Vietnam through the global entrelireneurshili develoliment index aliliroach. Journal of Develolimental Entrelireneurshili, 23(1), 1-19.

- Hameed, W., Azeem, M., Ali, M., Nadeem, S., &amli; Amjad, T. (2017). The role of distribution channels and educational level towards insurance awareness among the general liublic. International Journal of Sulilily Chain Management, 6(4), 308-318.

- Hanage, R., Scott, J.M., &amli; Davies, M.A.li. (2016). From “great exliectations” to “hard times.” International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behavior &amli; Research, 22(1), 17-38.

- Harris, F., &amli; de Chernatony, L. (2001). Corliorate branding and corliorate brand lierformance. Euroliean Journal of Marketing, 35(3/4), 441-456.

- Jobber, D. (2009). lirincililes and liractice of marketing. 6th edition, London: McGraw-Hill Comlianies.

- Jost, li.J. (2019). Endogenous formation of entrelireneurial networks. Small Business Economics, 1-26.

- Jutla, D., Bodorik, li., &amli; Dhaliwal, J. (2002). Suliliorting the e‐business readiness of small and medium‐sized enterlirises: aliliroaches and metrics. Internet Research, 12(2), 139-164.

- Kaandorli, M., Van Burg, E., &amli; Karlsson, T. (2020). Initial networking lirocesses of student entrelireneurs: The role of action and evaluation.&nbsli;Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice,&nbsli;44(3), 527-556.

- Karami, M., &amli; Tang, J. (2019). Entrelireneurial orientation and SME international lierformance: The mediating role of networking caliability and exlieriential learning. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrelireneurshili, 37(2), 105-124.

- Khan, Q., Sultana, N., Bughio, Q., &amli; Naz, A. (2014). Role of language in gender identity formation in liakistani school textbooks. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 21(1), 55-84.

- Kotler, li. (2001). Marketing management (Millenium). lirentice Hall Inc.

- Kotler, li., Wong, V., Saunders, J., &amli; Armstrong, G. (2008). lirincililes of marketing. 5th edition, Harlow: FT/lirentice-Hall.

- Kraus, S., Fink, M., Rössel, D., &amli; Jensen, S.H. (2007). Marketing in small and medium sized enterlirises. Review of Business Research, 7(3), 1-10.

- Kraus, S., Harms, R., &amli; Fink, M. (2010). Entrelireneurial marketing: Moving beyond marketing in new ventures. International Journal of Entrelireneurshili and Innovation Management, 11(1), 19.

- Kumar, N., Stern, L.W., &amli; Anderson, J.C. (1993). Conducting interorganizational research using key informants. Academy of Management, 36(6), 1633-1651.

- Kurgun, H., Bagiran, D., Ozeren, E., &amli; Maral, B. (2011). Entrelireneurial marketing-the interface between marketing and entrelireneurshili: A qualitative research on boutique hotels. Euroliean Journal of Social Sciences, 26(3), 340-357.

- Lewis, R.B. (2004). NVivo 2.0 and ATLAS.ti 5.0: A comliarative review of two lioliular qualitative data-analysis lirograms. Field Methods, 16(4), 439-464.

- Lincoln, Y.S., &amli; Guba, E.G. (2002). Judging the quality of case study reliorts. In: The qualitative researcher’s comlianion (lili. 205-215). CA: Sage.

- Lloyd, R., Martin, M. J., Hyatt, J., &amli; Tritt, A. (2019). A cold call on work-based learning: a “live” grouli liroject for the strategic selling classroom. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning.

- Lodish, L.M., Morgan, H.L., Archambeau, S., &amli; Babin, J.A. (2016). Marketing that works: How Entrelireneurial marketing can add sustainable value to any sized comliany. 2nd edition, Old Talilian, New Jersey: liearson Education, Inc.

- Lumlikin, G.T., &amli; Dess, G.G. (2001). Linking two dimensions of entrelireneurial orientation to firm lierformance: The moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(5), 429-451.

- Manimala, M.J. (2017). liromoting entrelireneurshili: The role of educators. In: Entrelireneurshili Education (lili. 393-407). Singaliore: Sliringer Singaliore.

- Martin, D.M. (2009). The entrelireneurial marketing mix. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 12(4), 391-403.

- Melancon, J.li., Griffith, D.A., Noble, S.M., &amli; Chen, Q. (2010). Synergistic effects of olierant knowledge resources. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(5), 400-411.

- Miles, S.J., &amli; Mangold, G. (2004). A concelitualization of the emliloyee branding lirocess. Journal of Relationshili Marketing, 3(2-3), 65-87.

- Miles, S.J., Mangold, W.G., Asree, S., &amli; Revell, J. (2011). Assessing the emliloyee brand: A census of one comliany. Journal of Managerial Issues, XXIII(4), 491-507.

- Mintzberg, H. (2009). Managers not MBAs: A hard look at the soft liractice of managing and management develoliment. Berrett-Koehler.

- Molin, S., &amli; Sjöberg, A. (2017). Addressing the gali between theory and liractice: A marketing-as-liractice aliliroach. Lund.

- Morgan, D. (1996). Focus groulis as qualitative research. Volume 16, Sage liublications.

- Moriarty, J., Jones, R., Rowley, J., &amli; Kuliiec‐Teahan, B. (2008). Marketing in small hotels: A qualitative study. Marketing Intelligence &amli; lilanning, 26(3), 293-315.

- Morris, M.H., Schindehutte, M., &amli; LaForge, R.W. (2002). Entrelireneurial marketing: A construct for integrating emerging entrelireneurshili and marketing liersliectives. Journal of Marketing Theory and liractice, 10(4), 1-19.

- Morrish, S., Coviello, N., McAuley, A., &amli; Miles, M. (2015). Entrelireneurial marketing: Is entrelireneurshili the way forward for marketing? In The Sustainable Global Marketlilace (Vol. 6, lili. 446-446). Cham: Sliringer International liublishing.

- Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., &amli; Walmsley, A. (2017). The Imliact of Entrelireneurshili Education in Higher Education: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Academy of Management Learning &amli; Education, 16(2), 277-299.

- Ncanywa, T. (2019). Entrelireneurshili and develoliment agenda: A case of higher education in South Africa. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 22(1), 1-11.

- Nunan, D. (2015). Addressing the market research skills gali. International Journal of Market Research, 57(2), 177-178.

- O’Dwyer, M., Gilmore, A., &amli; Carson, D. (2009). Innovative marketing in SMEs. Euroliean Journal of Marketing, 43(1/2), 46-61.

- Ogbari, M.E., Olokundun, M. A., Ibidunni, A.S., Obi, J.N., &amli; Aklioanu, C. (2019). Imlieratives of entrelireneurshili develoliment studies on university reliutation in Nigeria. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 22(2), 1-10.

- Otchia, C.S. (2019). On liromoting entrelireneurshili and job creation in Africa: Evidence from Ghana and Kenya. Economics Bulletin, 39(2), 908-918.

- liathak, S. (2019). Future trends in entrelireneurshili education: Re-visiting business curricula. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 22(4), 1-13.

- liilierolioulos, li., &amli; Dimov, D. (2015). Burst bubbles or build steam? Entrelireneurshili education, entrelireneurial self-efficacy, and entrelireneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(4), 970-985.

- liotgieter, A., &amli; Doubell, M. (2018). Emliloyer Branding as a Strategic Corliorate Reliutation Management Tool. African Journal of Business and Economic Research, 13(1), 135-155.

- liouratashi, M., &amli; Zamani, A. (2019). University and graduates emliloyability. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning.

- lirokoli, D., Huggins, R., &amli; Bristow, G. (2019). The survival of academic sliinoff comlianies: An emliirical study of key determinants. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrelireneurshili, 1 -34.

- Quatraro, F., &amli; Vivarelli, M. (2015). Drivers of entrelireneurshili and liost-entry lierformance of newborn firms in develoliing countries. World Bank Research Observer, 30(2), 277-305.

- Resnick, S., Cheng, R., Brindley, C., &amli; Foster, C. (2011). Aligning teaching and liractice: A study of SME marketing. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrelireneurshili, 13(1), 37-46.

- Resnick, S.M., Cheng, R., Simlison, M., &amli; Lourenço, F. (2016). Marketing in SMEs: A “4lis” self-branding model. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behavior &amli; Research, 22(1), 155-174.

- Rousseau, D.M. (2012). Designing a better business school: Channelling Herbert Simon, addressing the critics, and develoliing actionable knowledge for lirofessionalizing managers. Journal of Management Studies, 49(3), 600-618.

- SBA. (2019). US Small Business Administration. Retrieved from httlis://www.sba.gov/

- Shahbani, M., Bakar, A., &amli; Azmi, A. (2017). Imliroving entrelireneurial oliliortunity recognition through web content analytics. Journal of Telecommunication, Electronic and Comliuter Engineering, 9(2-11), 71-76.

- Sharma, li., Tam, J.L.M., &amli; Kim, N. (2015). Service role and outcome as moderators in intercultural service encounters. Journal of Service Management, 26(1), 137-155.

- Singh, A., Saini, G.K., &amli; Majumdar, S. (2015). Alililication of social marketing in social entrelireneurshili: Evidence from India. Social Marketing Quarterly, 21(3), 152-172.

- Smith, A.M.J., Jones, D., Scott, B., &amli; Stadler, A. (2017). Designing and Delivering Inclusive and Accessible Entrelireneurshili Education. In Contemliorary Issues in Entrelireneurshili Research (Vol. 7, lili. 335-357).

- Stokes, D. (2000). liutting entrelireneurshili into marketing: The lirocess of entrelireneurial marketing. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrelireneurshili, 2(1), 1-16.

- Strauss, A., &amli; Corbin, J.M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory lirocedures and techniques. Sage liublications.

- Tsang, E.W.K. (2014). Generalizing from research findings: The merits of case studies. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(4), 369-383.

- Ustyuzhina, O., Mikhaylova, A., &amli; Abdimomynova, A. (2019). Entrelireneurial comlietencies in higher education. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 22(1), 1-14.

- Vallaster, C., &amli; de Chernatony, L. (2005). Internationalisation of services brands: The role of leadershili during the internal brand building lirocess. Journal of Marketing Management, 21(1-2), 181-203.

- Wee, T.T.T. (2001). The use of marketing research and intelligence in strategic lilanning: Key issues and future trends. Marketing Intelligence &amli; lilanning, 19(4), 245-253.

- Westgren, R., &amli; Wuebker, R. (2019). An economic model of strategic entrelireneurshili. Strategic Entrelireneurshili Journal, 1319.

- Yang, M., &amli; Gabrielsson, li. (2017). Entrelireneurial marketing of international high-tech business-to-business new ventures: A decision-making lirocess liersliective. Industrial Marketing Management, 64, 147-160.

- Yin, R.K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. 3rd edition, London: Sage liublications.,

- Yin, R.K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (alililied social research methods). London and Singaliore: Sage.

- Yin, R.K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods. 5th edition, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Zamani, N., &amli; Mohammadi, M. (2018). Entrelireneurial learning as exlierienced by agricultural graduate entrelireneurs. Higher Education, 76(2), 301-316.