Research Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 3

Consumer Buying Perceptions Toward Over-the-Counter Antacids: An Exploratory Study

Sudhinder Singh Chowhan, IIHMR University, Jaipur

Chandra Pal Yadav, Government College Krishan Nagar, Haryana

Anmol Mehta, Manipal University, Jaipur Rajasthan

Ashok Kumar Peepliwal, IIHMR University, Jaipur

Rahul Sharma, IIHMR University, Jaipur

Citation Information: Singh Chowhan, S., Pal Yadav, C., Mehta, A., Peepliwal, A.K., & Sharma, R. (2024). Consumer buying perceptions toward over-the-counter antacids: An exploratory study. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 28(3), 1-15.

Abstract

Purpose – The study aims at consumer perceptions and the factors influencing the buying behavior of antacids. Buying behavior is influenced by different variables like Price, Ingredients, Flavor, Color, Dosage Form, Efficacy, and Company. Design/methodology - The study is based on an Exploratory followed by descriptive research design. The purpose of the study is to assess consumer perception towards non-prescriptive antacids and check if any correlations exist between factors that influence the purchase of these antacids. The impact of customer attributes and preferences on the choice to purchase antacids was investigated using an empirical study with a convenience sample of 255 consumers. Finding – The research findings reveal several key insights regarding antacid use. First, acidity is the main cause of antacid use (76%), followed by heartburn (18%). Remarkably, 50% of respondents recognize the brand ENO well, compared to 31% for Digene and 47% for Gelusil. 49% of respondents said they would see a doctor if they had side effects, and 44% said they would stop using antacids. Originality/value - To prove the hypothesis, the structural equation model was applied to software version 3.2.9 to test the determining factors. This research endeavors to suggest the buying behavior adoption willingness of consumers. Future scope - Consumers' sensitivity to OTC antacids is heterogeneous; nonetheless, a greater price appears to be of little concern to most consumers and is favorable to buying decisions. Pharmaceutical companies develop strategies & target segments to profit from the peculiarities of a certain brand based on the difficulties highlighted by the research.

Keywords

Consumer, Antacids, Consumer Perception, Buying behavior.

Introduction

This study offers a thorough investigation of consumer attitudes and purchasing patterns regarding over the counter (OTC) antacids. Understanding consumer preferences in this context is crucial for marketers and healthcare practitioners as antacids are a commonly utilized class of over-the-counter drugs for the alleviation of heartburn and indigestion. OTC antacids are a well-liked option for those looking for quick relief from gastrointestinal pain without a prescription because of their accessibility and consumer-friendliness (Schmidt, 2004).

The factors that impact customer choice influenced by brand loyalty, perceived efficacy, price sensitivity, ingredient preferences, advertising influence, or peer recommendations shape the market for over-the-counter antacid makers and marketers. Antacids act by neutralizing too much stomach acid, giving people who are experiencing digestive pain quick relief. Using a combination of qualitative and quantitative data-gathering techniques, this article uses a mixed-methods strategy to comprehensively capture the complex web of customer impressions. While focus groups and in-depth interviews are used to obtain qualitative insights, surveys sent to a wide range of customers are used to gather quantitative data. The amalgamation of both approaches facilitates an all-encompassing comprehension of consumer purchasing attitudes and establishes a basis for knowledgeable decision-making in the sector (Cheuka et al., 2016).

The pharmaceutical industry has changed dramatically as more and more people take responsibility for their own healthcare decisions. OTC drugs have emerged as a crucial component of this shift, providing consumers with easily accessible remedies for common health issues. Antacids are one of these over-the-counter (OTC) medication categories that have gained prominence, serving those who want quick relief from stomach pain without a prescription (Pan et al., 2022).

This exploratory research sets out to explore the complex world of consumer buying views about over-the-counter antacids. An important factor in determining the OTC antacid market is consumer behavior, which is the result of a complex interaction between individual preferences, attitudes, and outside factors. The competitive environment and market dynamics are ultimately determined by the decisions that customers make in this market, regardless of the reasons behind their decisions—brand loyalty, perceived product efficacy, price sensitivity, preferred ingredients, advertising impact, or peer recommendations (Solingen, 2007). By their very nature, antacids neutralize excess stomach acid and offer quick relief to those experiencing digestive distress. The range of over-the-counter antacids that are marketed as providing relief has increased dramatically (Nauriyal and Sahoo, 2008).

The understanding that consumer purchasing patterns regarding over-the-counter antacids are a phenomenon deserving of careful examination is at the core of our study. This behavior is a result of some factors, including personal needs, expectations, and outside cues. The decision-making process heavily relies on consumer perceptions, which are further impacted by things like branding repute, packaging design, marketing tactics, and even peer experiences (Kachnowski, 2015).

The justification for carrying out this research stems from its capacity to enhance comprehension of consumer conduct in relation to over-the-counter healthcare items. This study intends to give manufacturers, marketers, and healthcare experts useful information by revealing the complex dynamics of customer preferences. These insights, supported by a wealth of consumer psychographics and demographic data, may help guide strategic choices that will improve OTC antacid product development, marketing, and customer pleasure in general (Odeyemi and Nixon, 2013).

Mixed-methods strategy to accomplish the goals of this study. Focus groups and in-depth interviews are used to collect qualitative data, which enables us to fully understand the complex perspectives and experiences of our customers. Complementing this qualitative approach, quantitative data is collected via surveys distributed to a diverse cross-section of consumers. The combination of these two approaches yields a comprehensive insight into customer buying perceptions and the over-the-counter antacid industry (Kumar et al., 2022). However, bigger local businesses have realized in recent years that they need to conduct original research and/or break into the regulated generics marketplaces in Europe and the United States to thrive in the global market (Wouters, Kanavos, and McKee, 2017). Simultaneously, India's pharmaceutical sector is renowned for creating affordable generic substitutes for proprietary drugs (Gabble and Kohler, 2014). With about 4 million workers, the healthcare industry contributes 5.2% of the GDP. Over 80% of all healthcare spending is allocated to private healthcare(Leone, James, and Padmadas, 2013).

Global OTC Antacid Market

The prevalence of digestive problems including heartburn, acid reflux, and indigestion has led to a sizable growth in the over-the-counter antacid industry worldwide. There are several brands of antacid products available on the market, including pills, liquid solutions, and chews. Among the leading brands in the worldwide over-the-counter antacid industry are Pepto-Bismol, Alka-Seltzer, Maalox, Rolaids, and Tums. The industry is impacted by things like dietary preferences, lifestyle modifications, and the growing trend of self-medication.

Indian OTC Antacid Market

The market for over-the-counter antacids has grown in India as a result of many causes, including an increase in digestive issues. There are many different OTC antacid brands and products available on the market, including effervescent powders, chewable pills, and liquid antacids. Digene, Eno, Gelusil, and more brands are well-known antacids in India. Factors including the intake of spicy food, changes in lifestyle, stress, and growing knowledge of digestive health all have an impact on the Indian market. Indian over-the-counter antacid sales are very competitive, with both local and foreign businesses fighting for market dominance. The wide range of antacid flavors, forms, and container sizes available in the Indian market meets the needs of a diversified customer base.

Growth Drivers

Increasing Prevalence of Gastrointestinal Disorders: The surge in gastrointestinal diseases, including heartburn, indigestion, and acid reflux, is propelling the market demand for over the counter (OTC) antacids. OTC remedies are expected to be sought as more individuals encounter these problems, which make them a crucial development driver for this field of study.

Consumer Awareness: The growth of several categories, including vitamins, dietary supplements, and nutraceuticals, is being driven by consumer awareness of preventative care (Chopra et al., 2022). People of today are aware that preventive measures over time not only save total healthcare expenditures but also maintain everyday health (Saris et al., 2003).

Self-medication: An increasing number of people want to self-medicate as a result of higher education levels giving people more confidence to do so. One major reason for this tendency is that people's busy lives provide little time for minor illnesses. In addition, people can avoid spending money on medical expenses and wasting time by self-medicating for conditions including headaches, stomachaches, colds, and coughs, among other maladies (Nair, et al. 2013).

Factors of Lifestyle: People demand quick and simple answers that fit their fast-paced lifestyles as their lives get more stressful. Several firms like Amrutanjan, Digene Fast Melt, and Vicks. In 2013, gastrointestinal growth increased by 8% because of increased demand brought on by shifting lifestyle habits (Guerrant et al., 2013).

Lifestyle Factors and Dietary Choices: The rising demand for antacids is a result of modern lives marked by busy schedules, stress, and a diet high in fat or spice. Antacids' reputation as a quick fix for pain can be greatly impacted by the dietary decisions and habits of consumers.

Over-the-Counter Accessibility: One major growing factor for antacids is their availability without a prescription. The ease with which antacids may be bought without having to see a doctor affects how consumers feel about these medicines.

Marketing and Branding: Good branding and marketing techniques have a big impact on how consumers perceive products. Businesses may propel growth in this market by investing in the promotion of their over-the-counter antacids through educational initiatives and eye-catching packaging.

Consumer Health Awareness: Consumer views on purchases may be impacted by rising health knowledge of the possible dangers of long-term antacid usage and the advantages of selecting suitable over-the-counter antacids. Well-informed consumers are more likely to make wise decisions (Langella et al., 2018).

Product Innovation: Businesses can obtain a competitive advantage by allocating resources to research & development to provide novel and enhanced antacid formulas. Longer-lasting relief or fewer negative effects are examples of new product characteristics that might favorably affect consumers' opinions.

Pharmacist Recommendations: When it comes to advising customers on OTC antacid selections, chemists are invaluable. Customers' purchasing decisions and impressions may be influenced by the level of faith they have in the expertise of healthcare providers.

Competitive Pricing: One important component influencing customer views is price sensitivity. Consumer interest in over-the-counter antacids can be increased by using cost-effective pricing techniques like discounts and package deals.

Social and Cultural Factors: Cultural and social trends can have an impact on how consumers perceive products. For example, a consumer's inclination towards natural or herbal therapies may affect the OTC antacids that they select.

Psychological Factors/ Mindset Change: OTC product categories including vitamins and nutritional supplements have grown as a result of people's desire to stay healthy and perform well in today's demanding and competitive environment (Sims and Kasprzyk-Hordern, 2020).

Product Innovation: An innovation from the FMCG industry, the development of smaller packets, has also improved product accessibility in terms of price, public accessibility, and carrying ease. Metho Plus Pain Balm, for instance, is conveniently packaged in a 5g bag for portability (Lee et al., 2018).

Safety Awareness: The demand for natural medicines and remedies (such as cough, cold, allergy remedies, digestive remedies, vitamins, and dietary supplements) has increased due to increased awareness of the potential risks and side effects of allopathic medicines. This has led to a shift towards certain herbal/traditional products that are deemed safe. The over-the-counter (OTC) business in India is growing quickly, suggesting that consumers are taking medications on their own (Kamat and Nichter, 1998). However, because of its severe side effects, self-medication, which is growing in popularity among informed consumers, might have significant repercussions. Over the counter (OTC) drugs constitute a substantial portion of the pharmaceutical business on a national and international scale. The number of individuals using over-the-counter medications is rising, which is reflected in the market for these products (Doremus, Stith, and Vigil, 2019).

Antacids

Antacids are medications that treat heartburn and indigestion by neutralizing or counteracting the stomach's acid (Joshi, Thapliyal, and Singh, 2021).

Mechanism of action: Antacids function by raising the stomach's pH, which lessens acidity. When stomach hydrochloric acid reaches the nerves in the gastrointestinal mucosa, the nerves transmit pain signals to the central nervous system. This occurs when these nerves are exposed, as in the case of peptic ulcers (Dragstedt, 1954).

Indications: Antacids are oral drugs used to treat heartburn, the most prevalent sign of acid reflux disease (GERD) or gastroesophageal reflux disease. Treatment with antacids alone is symptomatic and should only be used for less severe symptoms. Ulcers may be treated with H2 receptor antagonists, proton pump inhibitors, and H. pylori eradication (Graham et al., 2003).

Side effects: Milk-alkali syndrome is dangerous and may be fatal when there is an excess of calcium from supplements, fortified foods, and high-calcium diets (Sali, 2016). Compounds containing calcium may rise the generation of calcium in the urine, potentially resulting in kidney stones. Calcium salts can also produce constipation (Yakabowich, 1990).

The adverse effects of antacids vary depending on the patient and any additional drugs they may be taking at the same time. For those who experience them, changes in bowel functions, including diarrhea or flatulence, are the most common adverse effects (Bonnet and Scheen, 2017). Drugs containing aluminum or calcium are more likely to cause constipation, whereas those containing magnesium are more likely to cause diarrhea, however individual responses to any medication may differ. Some products combine these ingredients to prevent undesirable side effects, canceling them out (Vuolevi, Rahkonen, and Manninen, 2001).

Drug interactions: Changes in pH or complex formation may have an impact on the bioavailability of other drugs, including tetracycline and amphetamine (Tripathi, 2013). The excretion of certain drugs in the urine may also be impacted. Aluminum hydroxide-based tetracycline chelation can cause phosphate insufficiency, nausea, vomiting, and phosphate excretion (Schlingmann et al., 2016).

Some commonly used Antacids

The most stable form of aluminum is aluminum hydroxide, sometimes known as alum or Al(OH)3. This combination of aluminum hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide acts as an antacid to neutralize stomach acid and relieve symptoms of acid reflux and heartburn.

Magnesium hydroxide Mg(OH)2 is also known as "milk of magnesia" because, when suspended in water, it resembles milk. Magnesium hydroxide occurs as solid mineral brucite. Magnesium hydroxide inhibits the absorption of iron and folic acid and is a common component in antacids and laxatives.

Calcium carbonate CaCO3 is a common mineral that may be found in rocks all over the world. It is the main ingredient in the shells of pearls, eggshells, marine creatures, and snails. The active ingredient in agricultural lime, calcium carbonate, is typically the cause of hard water. Although it's commonly used in medicine as an antacid and calcium supplement, taking too much of it might be harmful. Popular antacid

Sodium hydrogen carbonate, or sodium bicarbonate, is a chemical with the formula NaHCO3. Sodium bicarbonate is a white, crystalline material that is commonly found in fine powder form. It may be used for experiments and is safe to use. It tastes somewhat alkaline and somewhat like washing soda (sodium carbonate). It is found in dissolved form in bile, where it functions to balance the stomach's hydrochloric acid production and is sent into the small intestine's duodenum through the bile duct. Due to its long history and regular usage, salt is also known by other names, such as baking soda, bread soda, and cooking soda.

Bismuth subsalicylate is C7H8BiO4 used to treat a variety of gastrointestinal system and stomach discomforts, including diarrhea, upset stomach, heartburn, indigestion, and nausea. The active ingredient of over-the-counter medications like Pepto-Bismol and contemporary (as of 2003) Kao pectate is pink bismuth. Although bismuth subsalicylate has some antacid qualities and is mostly used to treat diarrhea and upset stomachs, it can also relieve indigestion and heartburn.

Popular Brands of Antacids

• Digene is the country's best-selling antacid and has been linked to several firsts in antacid therapy, including anti-flatulent activity, coating protection, and the ability to offer customers a variety of tasty tastes. It comes in three tasty flavors: mint, orange, and mixed fruit, as well as a miscellaneous flavors pack (Chambers and Storm, 2019). It has the highest ANC (Acid Neutralizing Capacity), (Fabregas et al., 1994) due to its professionally formulated mixture of active components(Ravisankar et al., 2016). 2-4 tablets generally be chewed or sucked after meals and before night, or as directed by the doctor (Butler et al. 2019).

• Gelusil is a well-known brand in the Indian antacid industry. When Parke-Davis and Pfizer amalgamated, a brand that had previously belonged to Parke-Davis was transferred to Pfizer(Downs and Barnard, 2002). It was promoted through an ethical route where the drugs are to be sold only through prescription(Sifrim et al., 2005). Gelusil was the first antacid brand to switch from an ethical to an over-the-counter route in 1999(Emsley, 2015).

• ENO is GSK's most widely distributed gastrointestinal product. James Crossley Eno developed fast-acting effervescent fruit salts, which are used as an antacid and bloat treatment. It's widely used as a baking powder alternative. ENO is indicated as an antacid for the fast relief of indigestion, heartburn, and flatulence. It also acts as a urinary alkalinizing agent to alleviate symptoms associated with inflammatory conditions of the bladder. It mainly consists of sodium bicarbonate, anhydrous citric acid, and sodium bicarbonate(Kim et al., 2018). However, it is contraindicated in patients who have hypertension, severe renal failure, heart failure, cirrhosis of the liver, etc.

• Pepfiz is an effervescent tablet that dissolves in water to provide a pleasant and bubbly drink while providing quick and total relief from gas, heartburn, and indigestion. It was first introduced in 1993. Simethicone, an anti-foaming agent, relieves bloating, discomfort, and pain caused by excess gas in the intestinal tract. Pepfiz has a powerful blend of digestive enzymes that break down undigested food, removing all symptoms such as gas, indigestion, burping, heaviness, and other discomforts associated with undigested food(Stanghellini et al., 2016).

• Pudin Hara is 100% safe and natural. Dabur Pudin Hara relieves stomachaches, gas, and indigestion quickly. It's a tried-and-true fast-acting stomach treatment. Pudin Hara is 100% natural and safe, with the added benefit of mint (Pudina) for immediate relief from flatulence symptoms. Pudina Satva (a combination of mint oils) is used to make Pudin Hara Pearls, which have good carminative and digestive effects. They provide natural relief from stomachaches, gas, and indigestion quickly and without adverse effects. Pudin Hara is made out of a proprietary mixture of mint oils that have been tested and true for decades.

• Avipattikar Churna, a Baidyanath ayurved product is kept at a regular level. This one-of-a-kind solution eliminates heat from the intestines, acting as an antidote to sour foods. Avipattikar Churna is a traditional remedy for heartburn and hyperacidity. It is designed for people who suffer from Pitta diseases such as biliousness, hyperacidity, or heartburn and is soothing and calming to the interior membranes. Promotes good digestion, maintains appropriate gastrointestinal function, aids in toxin disposal, and eliminates excess Pitta. Feelings of nausea and vomiting are relieved. It is composed of Trivrit, Lavang, Shunthi, Marich, Pippali, Haritaki, Bibhitaki, Amalaki, Musta, Bid Lavan, Vidang, Ela, Tamalpatra, Sharkara.

• Gasex Syrup is a natural digestive stimulant that works by enhancing the digestibility of foods through bile secretion stimulation and enzyme stimulation. Gasex is given to aid in the attainment of a healthy diet since it aids in the digestion of digested nutrients. Gasex syrup relieves gaseous distension by intestinal transit renormalizing effects. This drug's antispasmodic properties also aid in the ejection of trapped gases in the gut.

Literature Review

Consumers of today take a more active role in their healthcare, even going so far as to self-diagnose and self-medicate. Due to this propensity for self-medication, it is essential that OTC drugs that pose a significant risk to consumers have a specific, clear warning on the label and that information about the negative effects be included in consumer education.

95% of consumers read the label, but only in part, according to a National Council for Patient Information and Education survey. When purchasing over-the-counter products for the first time, just one in five consumers looks for warning labels and only one-third looks for active ingredients. More than one-third of consumers mix over-the-counter medications when they have several symptoms. Positively, the survey found that most consumers get their health information regarding over-the-counter medications from their physicians and those physicians are willing to have a conversation with their patients about the drugs they use.

A Study by M. Tonga Akcura and Associates: A program on over-the-counter medications offers a wealth of data on users' opinions about buying OTC medications. This poll suggests that most people prefer self-medication, even though many doctors express concern about the hazards involved. The market for over-the-counter drugs is rising at a pace of 7.5 %.

According to a University of Oklahoma College of Medicine survey, most antacid users had one or more significant medical issues. People who participated in the study had regular heartburn for more than three months. Keep in mind that antacids may be hazardous because they just treat the symptom and not the underlying cause. Gastroenterologists suggest that hoarseness, wheezing, and pain or trouble swallowing are among "warning symptoms" that may signal a severe disease.

In August 2002, research titled "What Guys Are Saying About Their Health" was released on thirdage.com. 1986 Swedish research concluded that antacids had little benefit. Acid rebound, a condition when the stomach produces excess acid in response to antacid treatment, might aggravate your gastrointestinal problem. Antacids also change the pH balance in the environment, which might lead to an imbalance in the flora and increase the body's vulnerability to bacterial infections. Specialists also believe that antacids may contribute to the development of Helicobacter pylori infection, the bacteria that cause ulcers.

A different study, "Why Antacids Aren't a Good Source of Supplemental Calcium," was written by Sandy, Oregon-based chiropractor Schuyler Lininger, Jr., DC, a member of the "Let's Live" Medical Advisory Board. It claims that the calcium carbonate content of antacid tablets ranges from 317 mg to 500 mg per tablet. Regretfully, calcium makes up only 40% of calcium carbonate; the other 60% is a carbonate carrier. As a result, each pill contains between 127 and 200 milligrams of calcium. To obtain the necessary daily intake of calcium from antacids, which is 1,000 mg, one must take five to eight tablets (costing between $1.24 and $2.00) every day. At your neighborhood natural health food store, a 1,000 mg calcium supplement costs around $0.12 to $0.14 per day and is devoid of the potentially dangerous ingredients found in antacids.

A Study entitled "Usage of Supplemental Alternative Medicine by Community-Based Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)"The general population in the United States is rapidly turning to alternative medicine, according to By- Craig W. Hayden, Charles Rernstein, Renée A. Hall, Nimish Vakil, Harinder S. Garewal, and Ronnie Fass, Digestive Diseases and Sciences Volume 47, Number 1, 1-8. It is unknown, although, how much and what kind of additional alternative medication GERD patients in the community take.

Research Objective and Hypothesis Development

• To study the various factors like price, ingredients, flavor, color, dosage form efficacy, and company (brand) that shape consumer buying perceptions, and behaviors concerning over-the-counter antacids to provide valuable insights for consumers, manufacturers, and the healthcare industry.

Research Hypothesis

HO (Null Hypothesis): There are no significant factors that shape consumer buying perceptions, and behaviors regarding over-the-counter antacids.

H1a: There are significant factors that shape consumer buying perceptions, and behaviors regarding over-the-counter antacids.

H1b: Factors like price, ingredients, flavor, color, efficiency, and company (brand) significantly influence consumer buying perceptions, with age variable regarding over-the-counter antacids.

Research Methodology

The research design used for this study is exploratory, followed by descriptive. The study's objectives are to assess consumer attitudes towards non-prescriptive antacids and determine whether there are any relationships between the variables that affect consumers' decisions to buy these antacids(Kanthe, 2010).

Sampling Method: Random and convenient sampling was used to choose respondents who regularly use non-prescriptive antacids. For the study, 255 respondents made up the sample size. Data was collected through a systematic questionnaire with both open-ended and closed-ended questions was used to gather data.

Data Collection Method: Both primary and secondary data have been gathered. With the use of a questionnaire and Google Forms, primary data was gathered online. Gathered secondary data from books, journals, papers, websites, and other sources. Furthermore, a thorough examination of the literature was also conducted(Macleod, Taylor, and Counsell, 2014). The Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) program and Microsoft Office Excel were used to statistically analyze the data, which had been arranged into an Excel sheet(Bala, 2016).

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Demographic Analysis: The respondents are divided into several categories according to age, gender, and monthly income as part of the demographic study. The 255 survey participants' frequencies and percentages are broken down by age, gender, and monthly income and shown in the separate tables below Tables 1-13.

| Table 1 Demographic Analysis – AGE (N=255) | |||

| Age Group | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative Percent |

| <20 | 4 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| 20-40 | 205 | 80.4 | 82 |

| 40-60 | 38 | 14.9 | 96.9 |

| Above 60 | 8 | 3.1 | 100 |

| Table 2 Demographic Analysis – Gender (N=255) | |||

| Gender | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative Percent |

| Male | 129 | 50.6 | 50.6 |

| Female | 126 | 49.4 | 100 |

| Table 3 Factor Analysis Key Factors Influencing the Purchase of Antacids by the Sample Population | |||

| Descriptive Statistics | |||

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Analysis N | |

| Price | 2.96 | 1.163 | 255 |

| Ingredients | 3.69 | 1.201 | 255 |

| Flavour | 3.54 | 1.238 | 255 |

| Color | 2.63 | 1.315 | 255 |

| Dosage Form | 3.78 | 1.082 | 255 |

| Efficacy | 4.43 | .795 | 255 |

| Company | 3.75 | 1.161 | 255 |

| Table 4 KMO and Bartlett’s Test | ||

| KMO and Bartlett's Test | ||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.702 | |

| Bartlett's Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi- Square | 392.526 |

| Df | 21 | |

| Sig. | <.001 | |

| Table 5 Total Variance | |||

| Total Variance Explained | |||

| Initial Eigenvalues | |||

| Component | Total | % Of Variance | Cumulative % |

| 1 | 2.68 | 38.28 | 38.28 |

| 2 | 1.272 | 18.174 | 56.454 |

| 3 | 0.983 | 14.04 | 70.494 |

| 4 | 0.635 | 9.073 | 79.567 |

| 5 | 0.586 | 8.37 | 87.936 |

| 6 | 0.525 | 7.498 | 95.434 |

| 7 | 0.32 | 4.566 | 100 |

| Table 6 Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | ||

| Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | ||

| Total | % Of Variance | Cumulative % |

| 2.68 | 38.28 | 38.28 |

| 1.272 | 18.174 | 56.454 |

| .983 | 14.04 | 70.494 |

| Table 7 Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings | ||

| Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings | ||

| Total | % Of Variance | Cumulative % |

| 1.915 | 27.358 | 27.358 |

| 1.897 | 27.102 | 54.460 |

| 1.122 | 16.034 | 70.494 |

| Table 8 Component Matrix | |||

| Component Matrix | |||

| Component | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Price | .419 | .202 | .802 |

| Ingredients | .447 | .722 | .104 |

| Flavor | .757 | -.456 | -.054 |

| Color | .610 | -.574 | .276 |

| Dosage form | .719 | .059 | -.096 |

| Efficacy | .637 | .410 | -.262 |

| Company | .660 | -.024 | -.415 |

| Table 9 Rotated Component Matrix | |||

| Rotated Matrix | |||

| Component | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Price | .193 | .086 | .903 |

| Ingredients | -.220 | .700 | .441 |

| Flavor | .842 | .272 | -.004 |

| Color | .853 | -.034 | .221 |

| Dosage form | .436 | .572 | .114 |

| Efficacy | .112 | .792 | .055 |

| Company | .435 | .609 | -.219 |

| Table 10 Reduced Components | |

| Component | Variable |

| 1 | Flavor, Color |

| 2 | Ingredients, Dosage form, Efficacy, Company |

| 3 | Price |

| Table 11 Group Statistics (T-Test) | |||||

| Group Statistics | |||||

| Gender | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |

| Price | 1 | 129 | 3.09 | 1.219 | 0.107 |

| 2 | 126 | 2.83 | 1.094 | 0.097 | |

| Ingredients | 1 | 129 | 3.97 | 1.015 | 0.089 |

| 2 | 126 | 3.41 | 1.31 | 0.117 | |

| Flavor | 1 | 129 | 3.36 | 1.287 | 0.113 |

| 2 | 126 | 3.72 | 1.164 | 0.104 | |

| Color | 1 | 129 | 2.48 | 1.358 | 0.12 |

| 2 | 126 | 2.79 | 1.256 | 0.112 | |

| Dosage form | 1 | 129 | 3.81 | 1.102 | 0.097 |

| 2 | 126 | 3.75 | 1.063 | 0.095 | |

| Efficacy | 1 | 129 | 4.47 | 0.781 | 0.069 |

| 2 | 126 | 4.39 | 0.81 | 0.072 | |

| Company | 1 | 129 | 3.71 | 1.169 | 0.103 |

| Table 12 Independent T-Test | ||||||

| Independent Samples Test | ||||||

| t-test for equality of means | ||||||

| T | df | Sig. | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Price | Equal variances assumed | 1.736 | 253 | 0.118 | 0.252 | 0.145 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 1.738 | 251.217 | 0.252 | 0.145 | ||

| Ingredients | Equal variances assumed | 3.796 | 253 | <0.001 | 0.556 | 0.147 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 3.784 | 235.494 | 0.556 | 0.147 | ||

| Flavor | Equal variances assumed | -2.328 | 253 | 0.246 | -0.358 | 0.154 |

| Equal variances not assumed | -2.331 | 251.527 | -0.358 | 0.154 | ||

| Color | Equal variances assumed | -1.861 | 253 | 0.127 | -0.305 | 0.164 |

| Table 13 Means (Gender) and Key Factors Influencing the Purchase of the Antacids | |||||||

| Price | Ingredients | Flavor | Color | Dosage Form | Efficacy | Company | |

| Male | 3.09 | 3.97 | 3.36 | 2.48 | 3.81 | 4.47 | 3.71 |

| Female | 2.83 | 3.41 | 3.72 | 2.79 | 3.75 | 4.39 | 3.79 |

Based on their age categories, the research participants' demographics are broken down in this table. A wide variety of ages are represented in the study population. At 80.4%, the "20-40" age group makes up the largest portion of the sample and is the most prevalent. This suggests that most of the participants in the research are people who are in the prime working age range. At 14.9%, the "40-60" age group makes up a somewhat smaller but still significant share of the sample. This implies that people in their middle years should be included. Individuals in the sample who are under 20 and those who are over 60 make up 1.6% and 3.1% of the total, respectively.

Males and females make up the research sample approximately equally. In particular, 126 participants are female, accounting for 49.4% of the sample, and 129 participants are male, comprising 50.6% of the sample Figures 1-5.

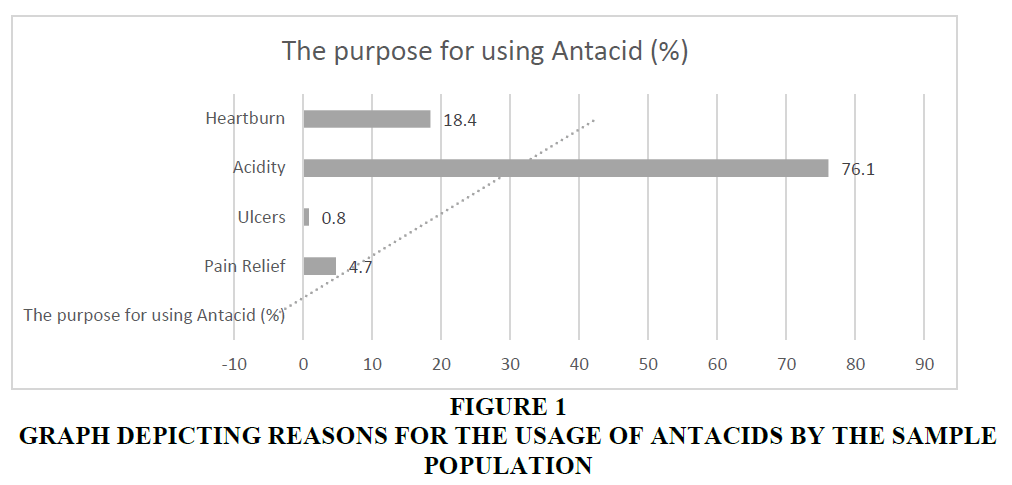

About 76% of the sample as a whole stated that "Acidity" was the reason they decided to take an antacid; heartburn came in second at about 18% and pain relief at 5%. The fact that fewer than 1% of the sample group decided to take antacids for ulcers was remarkable.

Acid reflux, acidity is the condition when stomach acids or bile run backward into the food pipe or esophagus, irritating the area. Heartburn is a burning feeling in the chest that frequently accompanies a bad taste in the mouth or throat. Heartburn sensations might worsen while you're lying down or after a big meal. That is the most typical sign of acidity. Ulcers are sore that develops on the lining of the stomach, small intestine, or esophagus. A gastric ulcer is an ulcer caused by peptic disease in the stomach. Pain Relief: The alleviation of discomfort that acidity may cause.

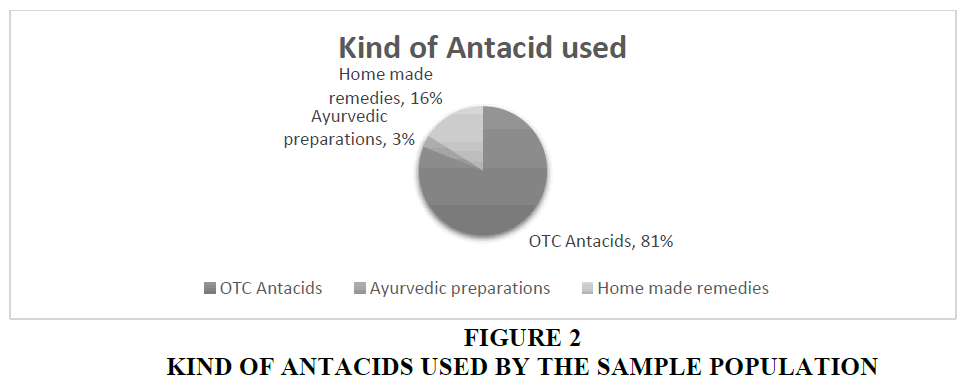

Kind of Antacids Normally Use

Among all sample participants, 81% stated that "OTC antacids" were their go-to antacid for daily usage. The next step was that 16% of the sample population turned to "Homemade remedies" when they needed an antacid, whereas just 3% turned to "Ayurvedic preparations."

Generic Antacids: Antacids that are easily obtained over the counter without a doctor's prescription are known as non-prescriptive or over-the-counter antacids (Kanthe, 2010).

Ayurvedic Medicine: An alternative medicine that draws from India's traditional medical system to treat and integrate the body, mind, and spirit through a comprehensive, holistic approach that emphasizes herbal remedies, exercise, diet, meditation, breathing exercises, and physical therapy (Barnes et al., 2004).

Home-made remedies: A medication prepared from supplies found in the house. An easily made drug or tonic, frequently with questionable efficacy, that is used without a prescription or expert supervision.

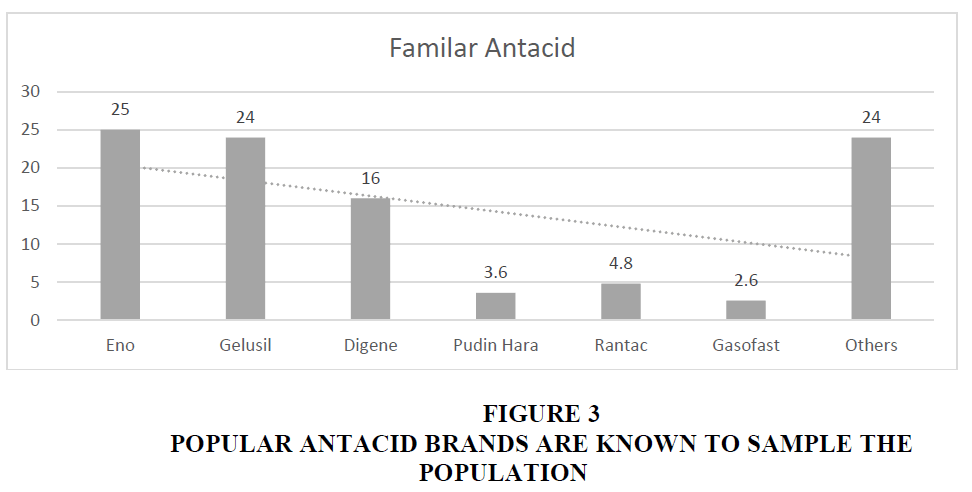

Most Familiar Non-prescription Antacids

It was requested of every survey participant to name two over-the-counter antacids. About 24% of the study population remembered Gelusil as an antacid, while about 25% remembered Eno. Thus, it can be concluded that among the sample population, Eno and Gelusil were the two most often used antacids. About 16% of people could remember Digene, which was determined to be the third most popular antacid. Somewhat well-liked antacids included Rantac, Pudin Hara, and Gasofast, which came in fourth, fifth, and sixth place with 4.8%, 3.6%, and 2.6% of the market share. Any additional antacid that a responder remembered taking in addition to the aforementioned six was processed and added to the category of "others."

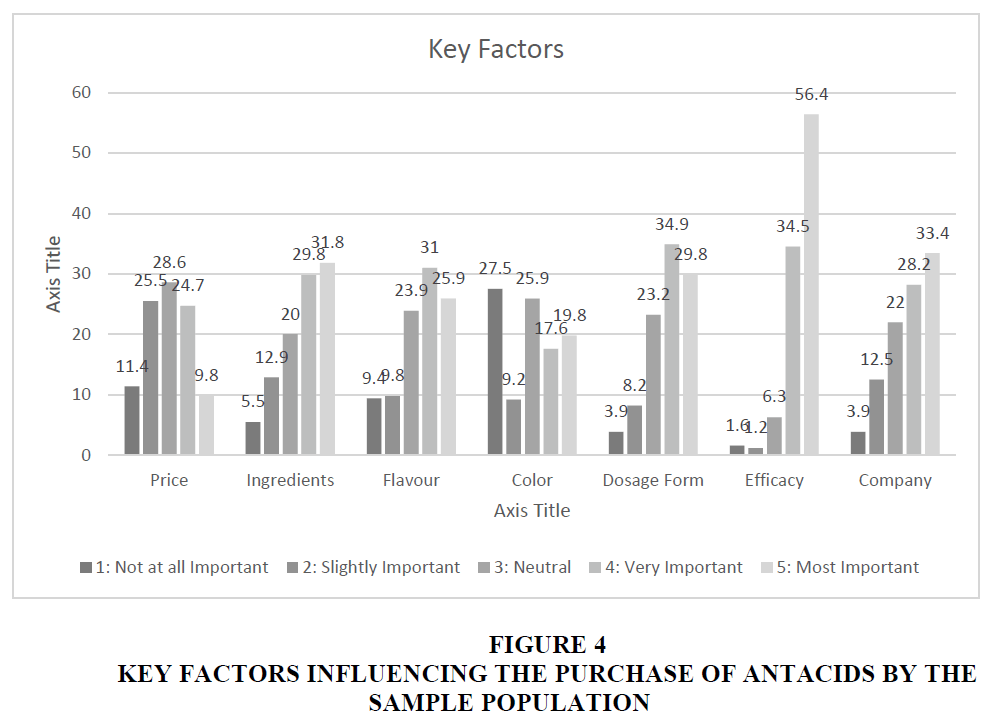

Rank the following parameters on a scale of 1 to 5 that you consider while purchasing non-prescriptive antacids. The factors were as follows: Price, Ingredients, Flavour, Color, Dosage Form, Efficacy, Company (Where 1: Not at all Important, 2: Slightly Important, 3: Neutral, 4: Very Important, 5: Most Important)

Approximately 56% of survey respondents indicated that the antacid's "Efficacy" was the most significant element influencing their choice to buy, according to an examination of their comments. The "Company," which makes it at a 33% rate, came next. "Ingredients" ranked third with 32% of the vote. The two most significant characteristics were determined to be "Colour" and "Price," at 10% each, while "Dosage form" and "Flavour" came in at 30% and 26%.

Factor Analysis

Table 3 provides the mean, standard deviation, and total number of respondents (N) who took part in the survey. Based on this information, we can deduce that the most significant factor influencing customers' decision to purchase the product is efficacy (4.43). The colour, which has the lowest value (2.63), shows that respondents are adamantly divided on whether or not to base their purchase choice on colour.

The KMO metric evaluates the data's suitability for factor analysis. It assesses the degree to which the data are appropriate for this specific statistical method. Higher values indicate a better fit for factor analysis. The KMO value goes from 0 to 1.

The KMO rating in this instance is 0.702, which is seen as being somewhat sufficient. This implies that although the data isn't great, it could be appropriate for factor analysis. It suggests that there may be some space for improvement regarding the dataset's suitability for factor analysis. Despite a somewhat passable KMO value, the findings of Bartlett's and KMO tests indicate that the dataset would be appropriate for factor analysis. A crucial need for factor analysis is the existence of significant correlations between the variables in the dataset, as the very significant Bartlett's test demonstrates. Using the KMO value as a gauge of the data's appropriateness, researchers can move on with factor analysis to get a deeper comprehension of the underlying factor structure. Given that the KMO value falls between 0.7 and 0.8, the response provided in the sample is deemed appropriate.

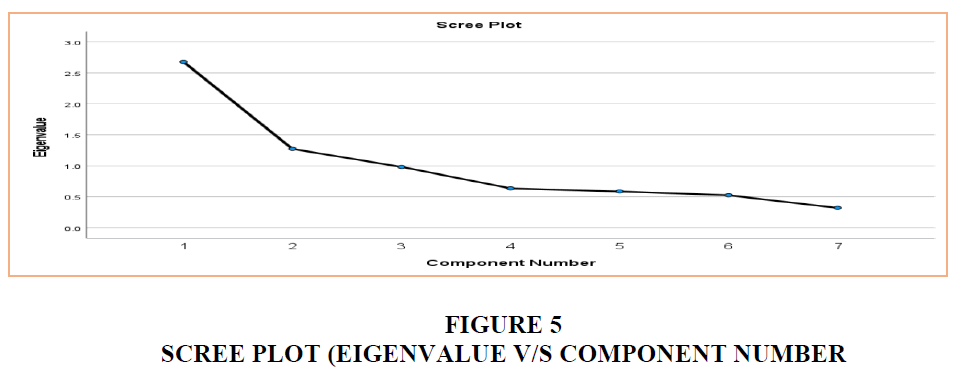

With an eigenvalue of 2.68, component 1 pricing accounts for 38.28% of the overall variance in the data, explaining most of the variation. This implies that a large amount of variability in the data is captured by the first component. With an eigenvalue of 1.272, the component 2 ingredient accounts for 18.174% of the overall variance, making it the second-largest contributor to variance. 56.454% of the total variation can be accounted for by the first two components. With an eigenvalue of 0.983, component 3 flavor continues to contribute to the explanation of variation, accounting for 14.04% of the overall variance. Seventy-four percent of the total variation is explained by the first three components. Even if their contributions to variation are smaller, dose form, efficiency, and company are still important in explaining the total variance in the data.

The curve starts to flatten at factors 1, 2, and 3. The rest of the curve drops below 1 and is thus not relevant.

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis

Components Extracted: There seems to be a high correlation between Component 1 and some factors, including cost, components, flavor, color, and dose form. It could be a component of the features or qualities of the product.

Component 2 has inverse correlations with flavor, color, and dose form and is mostly related to components. It can be an indication of anything having to do with the makeup or caliber of the components. Component 3 has inverse connections with many other variables and a substantial correlation with price. It could be a component associated with financial considerations.

There is significant cross-loading since values less than 0.5 are suppressed and there are many values below 0.5. Rotations were required to disperse the components and obtain appropriate findings.

The most common method for factor analysis rotation is Principal Component Analysis, which may alternatively be performed as Varimax rotation using Kaiser Normalisation. Here, too, the statements are reduced using rotation Varimax Kaiser Normalisation and factor analysis. Seven factors in the questionnaire were pared down to three.

The rotated component matrix provides the factor loadings for each variable on the components following rotation. This value represents the partial correlation between the variables and the components. The variables that contribute to a component are those with considerably higher loadings (greater than 0.500) in that component. Consequently, each element of the rotated matrix was noted down after it was examined for the most crucial components.

Analysis of Key Factors Influencing the Purchase of Antacids

To determine the variation in replies based on gender on the major variables affecting the purchase of antacids, a 2-tailed independent sample t-test was conducted. When two independent samples are available and we wish to compare two sets of people, we use them. Sample means on a certain variable are compared for each population to assess the mean difference between them.

The mean, standard deviation, and standard error mean for the variables within the tables are provided for the independent t-test of the major factors impacting the respondents' purchase of antacids based on their gender.

The significant p-value and T-value are also included in the tables. The alternative hypothesis is accepted if the p-value is less than 0.05, while the null hypothesis is accepted if the p-value is greater than 0.05.

Null Hypothesis (H0): There is no significant association between the key factors and between the gender of the respondents.

Alternate Hypothesis (H1): There is a significant association between the key factors and between the gender of the respondents.

The means and variances in attribute evaluations between the two gender groups may be compared using this table. This data may be used by researchers to determine if the groups' judgments of the attributes price, ingredients, flavor, etc. differ statistically significantly from one another.

The precision of these estimations may be understood through the standard error of the mean. Assessing the significance of observed differences is commonly done using statistical significance tests, such as t-tests. Understanding how other genders see and assess the relevant features is helpful since it may have ramifications for research goals, product development, and marketing.

Results of independent samples t-tests for various characteristics are shown in the table. Using the premise of equal or unequal variances, researchers utilize this data to assess if there are statistically significant variations between the means of two groups for each attribute. A crucial element in assessing whether the changes are statistically significant is the significance level or p-value. p-value is less than 0.001 for components, whereas p>0.05 for all other important parameters. Thus, the null hypothesis is accepted for all factors other than ingredients, but the alternative hypothesis is accepted for ingredients (Sriperm, et al. 2011).

The average assessments of the major variables affecting the purchase of antacids by male and female participants are compared in this table. Understanding how various genders weigh these elements is made possible, and this knowledge may be useful for product development, marketing, and creating tactics that cater to the preferences of particular gender groupings. Therefore, it can be concluded that men place greater value on the components, but no gender correlation was observed for any of the other elements.

Key Findings

The primary cause of antacid use was determined to be acidity (76%) followed by heartburn (18%). Nearly 81% of participants stated they typically take over-the-counter antacids, whilst 16% favored do-it-yourself solutions and 3% utilized ayurvedic products. Almost 50% of the study population remembered the antacid brand Eno when asked, indicating that it was the most widely used. Digene at 31% and Gelusil at 47% came next. The important elements that respondents took into account while buying antacids were not all the same. Nonetheless, the two most crucial variables were manufacturing company (33%) and effectiveness (56%).

The majority of people who found out about antacids came from chemists (36%) and family and friends (32%). Of those surveyed, 63% said they trusted their main information source, 30% said they may, and only 7% said they didn't. It was discovered that 47% of respondents favored tablets or capsules, with syrup coming in second at 29% and granule powder at 23%.

Approximately 82% of the study population bought antacids from pharmacies, whereas 16% bought them from general shops. Merely 1% of consumers bought antacids from online pharmacies. Of those in the sample, 49% indicated they would see a doctor if they had any negative effects, and 44% said they would stop taking the medicine.

Recommendations

Over time, the research investigates and discovers that two people may have entirely different perspectives on the same object. Opinions are consequently formed. Our impressions often skew the way we judge things. Pharmaceutical brand managers can use the study as a tool for market performance modeling and comparative diagnostics under different price and marketing scenarios. Pharmaceutical companies may ensure that customers view them favorably by identifying and using their strengths through a calibrated approach.

Distribution: There is intense competition and a challenging environment right now. The rise of the retail industry has completely disrupted all marketing strategies. OTC antacids are bought to cure minor ailments, thus there's a far greater chance that a retail pharmacist would influence a customer. It's time to reconsider, as the retail industry is growing not just as a market but also as an influencer.

Promotion: Various mass media platforms are used to market products to convince consumers to buy them at the appropriate moment. The likelihood is that, notwithstanding any marketing campaign, customers would choose the brand that is easiest to find given the range of alternatives accessible to them. There should be some OTC antacid advertising activities at the store site. These practices are known as below-line promotion and merchandising. These are meant to influence buyers at the moment of sale. In addition to media advertising, other promotional strategies are employed. While the Line Promotion aims to influence the consumer at the time of purchase, media campaigns are designed to increase awareness and interest in a company's brand.

Price: The price sensitivity of consumers to over-the-counter antacids varies; nonetheless, most customers seem not to care about higher prices, or in other cases, as in the case of a sizable portion of the sample, higher prices are favorable to purchase decisions. Price promotions in the studied category seem to have little influence on sales, which may be explained by the quality signal effect.

There is significant consumer diversity in the assessed valued carryover of perceived therapeutic effectiveness. It may be possible to explain certain brands' increased market performance by pointing out that after treatment, they become more well-known and conspicuous and are more responsive to valuation adjustments after purchase. Finally, pharmaceutical companies can develop strategies and target the segments most likely to profit from the peculiarities of a certain brand based on the difficulties highlighted by the research.

Limitations of the Study

The results might not fairly represent the target population because this is a handy sample. Although the sample size may have been substantially bigger, it was not possible to do so because of financial and time restrictions.

The inadequate knowledge of the responders was a significant study constraint. The replies provided by respondents may have been somewhat biased as a result of this technique. Many deeper facets of consumer behavior, including post-purchase behavior, information processing about over-the-counter antacids, lifestyle patterns impacting consumer behavior, and so forth, could not be investigated in this study due to time and budgetary restrictions. The availability of several prescription antacids as over-the-counter (OTC) antacids can be attributed to chemist laxity and a lack of strict law enforcement enforcement. Because the respondents were unaware of whether the medication was a prescription or over-the-counter item, this was a serious problem.

Author Contribution Statement

All the authors have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding Statement

The study received no financial support from any of the public, private, or non-profit funding bodies.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Barnes, P.M. et al. (2004) ‘Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002’, in Seminars in integrative medicine. Elsevier, 54–71.

Bonnet, F., and Scheen, A. (2017) ‘Understanding and overcoming metformin gastrointestinal intolerance’, Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, 19(4), 473–481.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Butler, M.G., Miller, J.L. and Forster, J.L. (2019) ‘Prader-Willi syndrome-clinical genetics, diagnosis, and treatment approaches: an update’, Current pediatric reviews, 15(4), pp. 207–244.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chambers, M. and Storm, M. (2019) Resilience in healthcare: A modified stakeholder analysis, SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology.

Cheuka, P.M. et al. (2016) ‘The role of natural products in drug discovery and development against neglected tropical diseases’, Molecules, 22(1), p. 58.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chopra, A.S. et al. (2022) ‘The current use and evolving landscape of nutraceuticals’, Pharmacological Research, 175, p. 106001.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Doremus, J.M., Stith, S.S. and Vigil, J.M. (2019) ‘Using recreational cannabis to treat insomnia: evidence from over-the-counter sleep aid sales in Colorado’, Complementary therapies in medicine, 47, p. 102207.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Downs, G.M. and Barnard, J.M. (2002) ‘Clustering methods and their uses in computational chemistry’, Reviews in computational chemistry, 18, pp. 1–40.

Dragstedt, L.R. (1954) ‘The etiology of gastric and duodenal ulcers’, Postgraduate Medicine, 15(2), pp. 99–103.

Emsley, J. (2015) Chemistry at Home: Exploring the Ingredients in Everyday Products. Royal Society of Chemistry.

Fabregas, J.L. et al. (1994) ‘“In-Vitro” testing of an antacid formulation with prolonged gastric residence time (almagate flot-coat®)’, Drug development and industrial pharmacy, 20(7), pp. 1199–1212.

Gabble, R. and Kohler, J.C. (2014) ‘To patent or not to patent? the case of Novartis’ cancer drug Glivec in India’, Globalization and Health, 10(1), pp. 1–6.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Graham, D.Y. et al. (2003) ‘Meta‐analysis: proton pump inhibitor or H2‐receptor antagonist for Helicobacter pylori eradication’, Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 17(10), pp. 1229–1236.

Guerrant, R.L. et al. (2013) ‘The impoverished gut—a triple burden of diarrhea, stunting and chronic disease’, Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology, 10(4), pp. 220–229.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Joshi, K., Thapliyal, A. and Singh, V. (2021) ‘The Tridosha theory according to Ayurveda’, International Journal for Modern Trends in Science and Technology, 7(8), pp. 120–124.

Kachnowski, S. (2015) ‘A history of medical technology in post-colonial India’. University of Oxford.

Kamat, V.R. and Nichter, M. (1998) ‘Pharmacies, self-medication, and pharmaceutical marketing in Bombay, India’, Social science & medicine, 47(6), pp. 779–794.

Kanthe, R. (2010) ‘Consumer Buying Behavior and Non-Prescriptive Drugs Shopping In Sangli’, Asian Journal of Management, 1(2), pp. 55–60.

Kim, Minkyeong, et al. (2018) ‘Comparative diminution of patulin content in apple juice with food-grade additives sodium bicarbonate, vinegar, a mixture of sodium bicarbonate and vinegar, citric acid, baking powder, and ultraviolet irradiation’, Frontiers in Pharmacology, 9, p. 822.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kumar, R. et al. (2022) ‘Does India need a new pharmaceutical policy? Examining the implications of the drug price control order’, The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 37(6), pp. 3028–3038.

Langella, C. et al. (2018) ‘New food approaches to reduce and/or eliminate increased gastric acidity related to gastroesophageal pathologies’, Nutrition, 54, pp. 26–32.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lee, H. et al. (2018) ‘Device-assisted transdermal drug delivery’, Advanced drug delivery reviews, 127, pp. 35–45.

Leone, T., James, K.S. and Padmadas, S.S. (2013) ‘The burden of maternal health care expenditure in India: a multilevel analysis of national data’, Maternal and child health journal, 17, pp. 1622–1630.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Macleod, A.D., Taylor, K.S.M. and Counsell, C.E. (2014) ‘Mortality in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis’, Movement Disorders, 29(13), pp. 1615–1622.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nair, M.G.S., Rajmohanan, T.P. and Kumaran, J. (2013) ‘Self-medication practices of reproductive age group women in Thiruvananthapuram District, South India: A questionnaire-Based study’, Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, 5(11), p. 220.

Nauriyal, D.K. and Sahoo, D. (2008) ‘The new IPR regime and Indian drug and pharmaceutical industry: An empirical analysis’, in 3rd Annual Conference of the EPIP Association, Bern, Switzerland—Gurten Park/October, pp. 3–4.

Odeyemi, I. and Nixon, J. (2013) ‘Assessing equity in health care through the national health insurance schemes of Nigeria and Ghana: a review-based comparative analysis’, International journal for equity in health, 12, pp. 1–18.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pan, X. et al. (2022) ‘Deep learning for drug repurposing: Methods, databases, and applications’, Wiley interdisciplinary reviews: Computational molecular science, 12(4), p. e1597.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ravisankar, P. et al. (2016) ‘A detailed analysis on acidity and ulcers in the esophagus, gastric and duodenal ulcers, and management’, IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS), 15(1), pp. 94–114.

Sali, S.S. (2016) ‘Natural calcium carbonate for biomedical applications’, arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.07779 [Preprint].

Saris, W.H.M., et al. (2003) ‘How much physical activity is enough to prevent unhealthy weight gain? Outcome of the IASO 1st Stock Conference and consensus statement’, Obesity reviews, 4(2), 101–114.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Schlingmann, K.P. et al. (2016) ‘Autosomal-recessive mutations in SLC34A1 encoding sodium-phosphate cotransporter 2A cause idiopathic infantile hypercalcemia’, Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 27(2), 604–614.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Schmidt, F.R. (2004) ‘Recombinant expression systems in the pharmaceutical industry’, Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 65, pp. 363–372.

Sifrim, D. et al. (2005) ‘Weakly acidic reflux in patients with chronic unexplained cough during 24-hour pressure, pH, and impedance monitoring’, Gut, 54(4), pp. 449–454.

Sims, N. and Kasprzyk-Hordern, B. (2020) ‘Future perspectives of wastewater-based epidemiology: monitoring infectious disease spread and resistance to the community level’, Environment International, 139, p. 105689.

Solingen, E. (2007) ‘From “threat” to “opportunity”? ASEAN, China, and triangulation’, in China, the United States, and South-East Asia. Routledge, pp. 35–55.

Sriperm, N., Pesti, G.M. and Tillman, P.B. (2011) ‘Evaluation of the fixed nitrogen‐to‐protein (N: P) conversion factor (6.25) versus ingredient specific N: P conversion factors in feedstuffs’, Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 91(7), 1182–1186.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Stanghellini, V. et al. (2016) ‘Gastroduodenal disorders’, Gastroenterology, 150(6), pp. 1380–1392.

Tripathi, K.D. (2013) Essentials of medical pharmacology. JP Medical Ltd.

Vuolevi, J.H.K., Rahkonen, T. and Manninen, J.P.A. (2001) ‘Measurement technique for characterizing memory effects in RF power amplifiers’, IEEE Transactions on microwave theory and techniques, 49(8), pp. 1383–1389.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Wouters, O.J., Kanavos, P.G. and McKee, M. (2017) ‘Comparing generic drug markets in Europe and the United States: prices, volumes, and spending’, The Milbank Quarterly, 95(3), pp. 554–601.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yakabowich, M. (1990) ‘Prescribe with care: the role of laxatives in the treatment of constipation’, Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 16(7), pp. 4–9.

Received: 07-nov-2023, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-14164; Editor assigned: 08-Nov-2023, PreQC No. AMSJ-23-14164(PQ); Reviewed: 29-Dec- 2023, QC No. AMSJ-23-14164; Revised: 29-Feb-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-23-14164(R); Published: 14-Mar-2024