Research Article: 2019 Vol: 18 Issue: 6

Consumer Behavior on the Russian Wellness Market: Results of Empirical Study

Konnikova Olga A, Saint-Petersburg State University of Economics

Yuldasheva Oksana U, Saint-Petersburg State University of Economics

Solovjova Julia N, Saint-Petersburg State University of Economics

Shubaeva Veronika G, Saint-Petersburg State University of Economics

Abstract

The wellness market is growing in Russia since the 1990s. This process is accompanied by promotion of healthy lifestyle and by development of consumption standards of wellness products and services. Because this industry is new for Russia, itsâ segment structure is constantly developing. Despite the great interest of producers to wellness market serious empirical studies are absent in this area in Russia. This paper empirically examines the effect that factors of external and internal nature have on consumersâ attitude and consumption within Russian wellness market. Research methods include literature overview, a series of in-depth interviews with wellness experts and a quantitative research of 560 Russian wellness market adherents. Results show a significant relationship between consumersâ attitude towards the wellness concept and the level of consumption of wellness goods and services. Eight segments of Russian wellness consumers with significantly different socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics were revealed and described during the study.

Keywords

Consumer Behavior, Consumer Modeling, Influencing Factors, Wellness, Russian Market, Segmentation.

Introduction

Kraft & Goodell (1993) define wellness as a holistic approach for improving the quality of health and life. Good health and well-being are part of UN sustainable development program and represent part of sustainable consumption trend-it is proved that sustainable food consumption and dietary choices make an important contribution towards meeting current environmental challenges (Grunert et al., 2014).

The main aim of realizing the wellness concept is preventing illnesses and prolonging life by using special combinations of goods and services (Pilzer, 2007). The qualitative composition of the wellness industry can be defined as follows (Goldman, 2011; Sun Waterhouse, 2011):

• Vitamins and dietary supplements;

• Enriched, natural (eco) and vegetarian products;

• Diagnostic, rehabilitation, beauty procedures and wellness treatments;

• Fitness and all forms of physical activity.

Analysis of consumer behavior on the wellness market was studied by Blair et al. (1989); Pilzer (2007); Sawyer et al. (2008); Goldman (2011); DiClemente et al. (2019). Reviewing the literature, we noticed a lack of studies that investigate relationships between behavior of wellness consumers and factors influencing that behavior. In addition, most studies were held in conditions of American, European, and Asian markets (Eagle, 2006; Laczó & Ács, 2009) and do not define the specifics of Russian consumers though this problem is becoming very urgent in Russia (Callister et al., 2009). The analysis of Russian media and RuNet (“Russian Internet”) show that people are concerned with problems of healthcare but lack official and proved information on the point. This makes the issues of Russian wellness consumer modeling rather crucial.

Accordingly, the primary objectives of the present paper are the following:

1. To identify conceptual traits of Russian wellness consumers’ behavior,

2. To distinguish the stimulating internal and external factors of wellness consumption,

3. To present a classification of Russian wellness market segments.

However, it cannot be expected that the increasing amount of information on the wellness concept will influence all the consumers in the similar manner forcing them to change their behavior. Classification of factors stimulating wellness consumption is researched in the following section.

Theoretical Background and Literature Overview

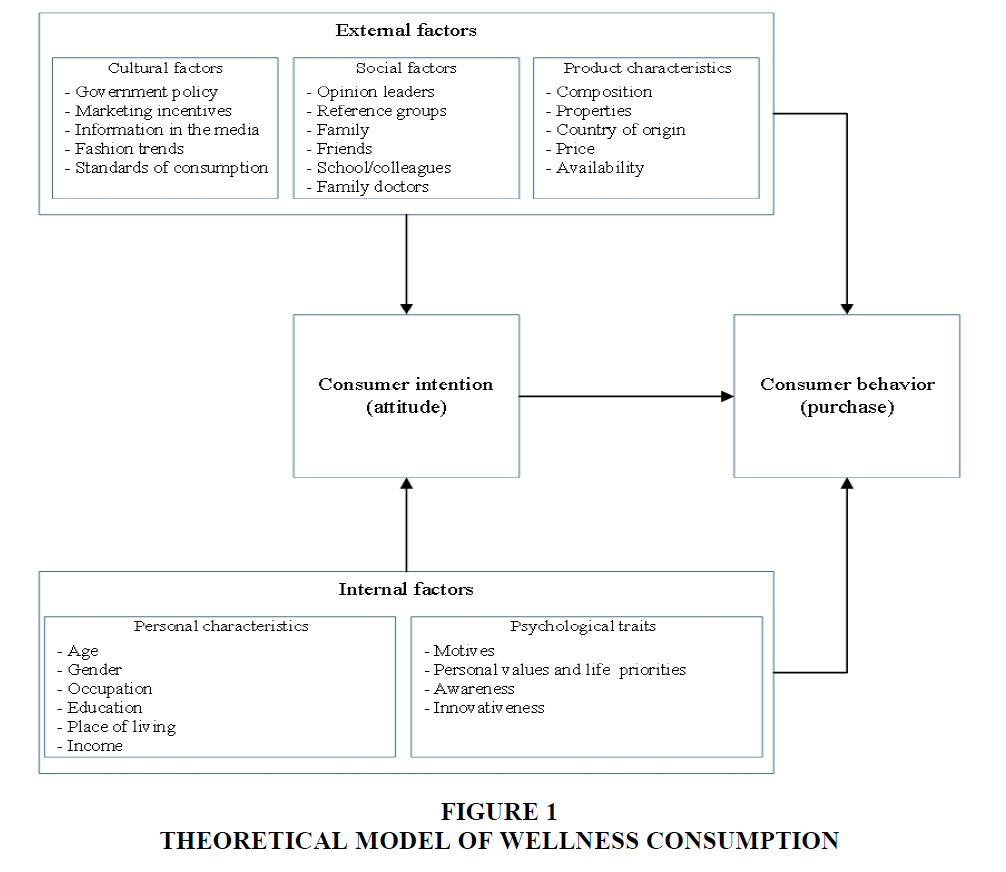

To develop a model of wellness consumption and to reveal factors stimulating it we started from the analysis of classical models of individual consumer behavior on b2c markets by Katona (1951); Engel et al. (1968); Howard & Sheth (1969); Hands (2010) paying special attention to modern investigations on the role of specific factors. Classical models of consumer behavior divide all influencing factors on internal and external ones (Hawkins et al, 1992). External factors are divided to cultural and social factors meaning the influence of environment (cultures and subcultures, social stratification, values and traditions) and consumer’s entourage (family, friends, reference groups, opinion leaders), as well as internal factors are divided into personal factors (gender, age, occupation, personal values) and psychosocial ones (motives, perception, knowledge, emotions).

Influence of External Factors on Wellness Consumption

Some authors pointed out predominant influence of certain factors on consumer purchasing decisions. For example; Duesenberry (1949) focused on the influence of social environment. Schor (1991); Solnick & Hemenway (2009) claimed that consumers are more affected by fashion trends and reference groups. Reingen & Kernan (1986) pointed out that a consumer first gathers information about new, unknown market and then uses it during purchase decision process, additionally emphasizing the word-of-mouth effect. Cialdini & Goldstein (2004) defined consumption norms valid for the certain society as a main source of consumer behavior modeling. Hopper & Nielsen (1991) wrote about the strength of normative influences and impact attitudes, while Ajzen & Fishbein (1980) analyzed the effect of an individual’s beliefs and norms on their attitudes, intentions, and consequently behaviors. Yuldasheva (2006) explored consumer behavior and factors influencing it within consumption standards.

Adoption by community is among the most influencing factors stimulating consumption of green and eco products (Moisander, 2007). This influence might come from family, friends, school and colleagues (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Nicholson & Xiao, 2011), different types of opinion leaders (Shoham & Ruvio, 2008), family doctors or role models like celebrities (Brace-Govan, 2013). Such tools of marketing communications as green advertising, eco labels, environmentally friendly packages and social actions are also among the important influencing factors (Leonidou et al., 2011; Shabunina et al., 2017). Promotion of healthy lifestyle by media is also proved to have a positive influence on the choice of wellness products and services (Maynard & Franklin, 2003; Chao et al., 2015).

To understand wellness consumer behavior more accurately, we chose the models of adoption of innovations for further research. Products and services that represent wellness consumption are evolutionary, not the revolutionary innovations as they reflect the following statements formulated by Mohr et al. (2010): expansion of an existing product or process, product characteristics are defined, markets are developing in response to consumer requirements. The model of Technology, Organization and Environment pays attention to the government policy towards innovations as well as information infrastructure. Institutional theory (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) reveals the pressure of the institutional environment. Such factors as pressure from market participants (competitive and partner pressure, the impact of social norms in the industry) should also be considered (Shchepinin et al., 2017).

The theory of innovations helped us to identify a new group of factors among external ones. We called it a group of Product characteristics including composition and properties of the product, its’ country of origin as well as price and availability. One of the most important barriers for wellness consumption is that wellness products and services are more expensive and sold in smaller quantities than the “usual” ones (Gogia & Sharma, 2012). Limited product availability and lack of infrastructure are also determined as discouraging wellness consumer behavior. Lack of knowledge also might influence consumer intentions negatively (Leiserowitz et al., 2006).

Influence of Internal Factors on Wellness Consumption

According to Zografos (2007), gender, age, level of education, and professional activities greatly affect the formation of responsible behavior. However, the biggest attention in this section should be paid to consumer values and life priorities (family, health, or career) connected with wellness lifestyle. Values are the driving force for all human actions (Schwartz, 1994). Vermeir & Verbeke (2006) proved the effect of the sustainable development values on different population groups. The best classification of wellness values was firstly formulated by Ardell (1977) as health nutrition, physical activity, stress management, personal health responsibility, environmental concern. Personal health responsibility later transformed into health consciousness (Gould, 1990) including such factors as health motivation and health information seeking and usage. Consumers with high health consciousness usually are willing to choose green and eco products even despite their higher price (Hughner, 2007; Michaelidou & Hassan, 2008). Among important life priorities for wellness lifestyle balance between different spheres of life and reduction of consumption (Cherrier et al., 2011) also should be mentioned.

Values transform into certain wellness motives, for example, need for health, disease prevention, body tone, dissatisfaction with the results of the use of traditional medicines etc. The full classification of wellness motives will be examined later specifically for Russian wellness consumers.

Some researches show that wellness behavior is determined by a more holistic set of factors, which can be interpreted as a way of life (Grunert et al., 2014). It is proved that for developing wellness consumption consumers have to change every day rhythm of their lives and well-established habits, which is difficult to implement in practice (Jansson et al., 2010; Dolnicar & Leisch, 2008). On the other hand, daily habits may gradually change through the provision of information and development of an attractive proposal for the market; so, marketing can play a major role in developing sustainable systems of production and consumption.

The theory of reasoned action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) and the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) assert that motivation and intention to consume are the direct factors that influence consumers to undertake certain behavior. Other researches (Viardot, 2004; Anilkumar & Joseph, 2012) also stated that influencing attitude change in consumers is fundamental in transforming their behavioral tendencies. The influence of all factors mentioned on Russian wellness consumers should be tested firstly applying qualitative research methods to clarify the classification of influencing factors and then by applying quantitative research methods to determine the importance of the selected factors.

Research Methodology

The research design combined both qualitative and quantitative methodologies and consisted of several stages. First, the desk-based investigation of literary sources and results of several relevant studies was undertaken to gain an insight into the current trends in the Russian wellness industry. A wide range of statistics (according to Russian State Statistics Committee as well as data of the World Health Organization and the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, open research data of consulting companies like RBC and Mintel) was examined to define the features of the Russian wellness market in comparison with the foreign ones. Because of the lack of empirical studies concerning Russian wellness consumers’ behavior, eleven semi- structured in-depth interviews with open-ended questions were conducted with experts working in wellness and specialized medical centers in 4 large Russian cities (Saint-Petersburg, Moscow, Ekaterinburg, Chelyabinsk).

Results of desk-based and qualitative research can be summarized as follows. In Russia the industry of wellness goods and services is just beginning to arise. The culture of disease prevention is practically not developed and Russian consumers do not have a comprehensive understanding of the wellness concept. The behavior of most consumers can be described as spontaneous, constantly changing, without any order and structural logic and is highly affected by fashion trends and media factors. “Many of my consumers today buy kilograms of dietary supplements, tomorrow forget about a healthy lifestyle, the day after tomorrow spend all their free time in a gym and so and so…” (Irina Hlestkova, family doctor, Chelyabinsk).

The growing interest towards the wellness concept is reflected in increasing amount of popular scientific information in the media. All experts agree that wellness issues need to be discussed more in media, in social advertising, in hospitals and at schools. With the growing interest of consumers in the wellness concept the number of people who not only search for specialized information in the media but also attend training sessions, courses, seminars conducted by practicing doctors, specialists, representatives of manufacturers' companies are constantly rising. “Today, many of those patients who come to me are more aware of current trends in physiotherapy than many of my colleagues, and this knowledge is of very high quality” (Valentina Gusakova, chiropractor, Saint-Petersburg). Simultaneously, there is a negative opinion about some groups of wellness goods and services (dietary supplements, eco-products) among Russian consumers, not confirmed by scientific facts, but widely replicated through media.

The wellness industry in Russia is developing according to the Western pattern, often without adaptation to Russian conditions. There are no clear-cut leaders in the industry: Western companies operate quite cautiously on the Russian market, while Russian companies, even the largest ones, are not engaged in the active formation of consumption standards. The main reason for it is low incomes of most Russian population and the inability of consumers to spend significant amount of money on wellness goods and services. “Those visitors who are richer immediately choose American products by NL or NSP, while those with lower income ask to recommend them something from domestic dietary supplements producers-Evalar or the like” (Liubov Orlova, pharmacist, Ekaterinburg). However, practically all interviewed specialists are sure that some categories of consumers are gradually coming to realize that wellness goods and services should cost more than “ordinary” products.

The main motives for Russian wellness consumers are interest and pleasure of healthy way of life; self-development; prevention of diseases like diabetes, overweight, tooth decay, heart problems; body tone and care for appearance; dissatisfaction with the results of the use of traditional medicines; fashion influence; care for relatives and children. Marketing incentives most influencing on consumers are possibility of trial use; presence of approved reviews; information from exercises, courses and workshops; visual demonstration of effects.

Today, wellness industry in Russia is characterized by high product differentiation, including price factor, as well as the presence of many small segments of consumers that differ in their characteristics, needs and behavior in the market. In the developed theoretical model of wellness consumption (Figure 1) we tried to reflect the role of internal and external factors mentioned above as well as the significance of the influence that attitudes have on behavioral changes.

Hypotheses

Theoretical model of wellness consumption (Figure 1) developed through the desk-based research as well as the results of in-depth interviews helped to state the following hypotheses for the future quantitative research:

Firstly, it is interesting to identify how differences in age and gender of consumers affect their behavior (the consumption of wellness goods and services).

H1 Personal characteristics of Russian consumers (age, gender, etc.) influence the consumption of wellness goods and services.

The comparative influence power of different factors remains the least explored and represents a certain research gap; that makes it possible to formulate the following hypothesis.

H2 Social factors, particularly reference groups, influence the consumption of wellness goods and services on the Russian market.

As the wellness industry is a new market for Russia it is possible to say that it is in the stage of implementation or early growth according to the theory of industry life cycles. That determines higher influence of price, product and information factors.

H3 Product characteristics (especially price) and cultural factors (especially fashion trends) influence the consumption of wellness goods and services more than psychological traits of Russian consumers (values and motives).

Several researches (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Anilkumar & Joseph, 2012) stated that influencing attitude change in consumers is fundamental in transforming their behavioral tendencies. We try to prove the significance of the influence that attitudes have on behavioral changes applied to the Russian wellness market.

H4: The consumption of wellness goods and services on the Russian market grows with the improvement of attitude towards the wellness concept.

Sample Description for Quantitative Research

The empirical analysis was based on the data collected by means of written questionnaire with open and closed questions; data was processed and analyzed using IBM SPSS. We collected the data with the distribution of questionnaire through social networks (Vk.com and LinkedIn) and e-mail from September to December 2014.

The given questionnaire consisted of several blocks of questions devoted to the following issues (Table 1).

| Table 1: Structure Of The Questionnaire | |

| Blocks of the questionnaire | Results of the literature review |

|---|---|

| Attitude towards the wellness concept | Viardot, 2004; Anilkumar & Joseph (2012) |

| Frequency of the use of wellness products and services | Pilzer (2007); Kraft & Goodell (2003); Sawyer et al. (2008); Goldman (2011); Sun-Waterhouse (2011): Grunert et al. (2014) |

| Motives0 determining wellness consumers’ behavior | Vermeir & Verbeke (2006); Hughner (2007); Michaelidou & Hassan (2008); Dolnicar & Leisch (2008); Jansson et al. (2010); Cherrier et al. (2011) |

| Sources of information important to the respondents | Leiserowitz et al. (2006); De Pelsmacker & Janssens (2007); Gogia & Sharma (2012) |

| Individuals influencing consumers’ purchase decision | Moisander (2007); Brace-Govan (2013) |

| Marketing incentives affecting wellness consumers | Maynard & Franklin (2003); Yuldasheva (2006); Leonidou et al. (2011); Solnick & Hemenway (2011) |

| Behavioral characteristics of the respondents | Cialdini & Goldstein (2004); Eagle (2006); Laczó & Ács (2009); Callister et al. (2009) |

Frequency of consumption was measured by asking respondents how often they buy different categories of wellness products and services on 6-point interval scale (1=buy more often than once a month, 6=never buy). Measures 1 and 3-7 were examined using five-point Likert-type scale (1=totally agree; 5=strongly disagree). Such variables as gender, age, occupation, income level and place of living were also included in the questionnaire.

On the result of quantitative research, we collected more than 5000 questionnaires (with the response rate of 81%), 560 of which were randomly selected and quoted on such socio- demographic characteristics as age, gender and income (Table 2). Our sample has balanced gender ratio (M=295; F=265), with the average age of 37. 80% of the respondents named Saint- Petersburg as a place of living, this being one of the limitations of our research.

| Table 2: Key Sample Characteristics | |

| Sample characteristics | % |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 52.7 |

| Female | 47.3 |

| Age | |

| Younger than 25 years old | 22.5 |

| From 26 to 35 years | 18.6 |

| From 36 to 45 years | 24.3 |

| From 46 to 55 years | 17.9 |

| Older than 56 years old | 16.7 |

| Monthly income, rub. | |

| Less than 25000 | 24.2 |

| From 25001 to 40000 | 29.2 |

| From 40001 to 55000 | 25.8 |

| More than 55001 | 20.8 |

Analysis of Research Results and Discussion

To verify the established hypotheses, a quantitative survey on the sample of 560 respondents has been performed. Research methodology included several consecutive stages:

1. Construction of a correlation matrix to confirm the independence of factors included into the regression model

2. Conduction of the regression analysis to identify the factors determinant and statistically significant for the present study

3. Performing a hierarchical cluster analysis to identify consumer segments on the Russian wellness market

Estimation of Conceptual Model of Wellness Consumption

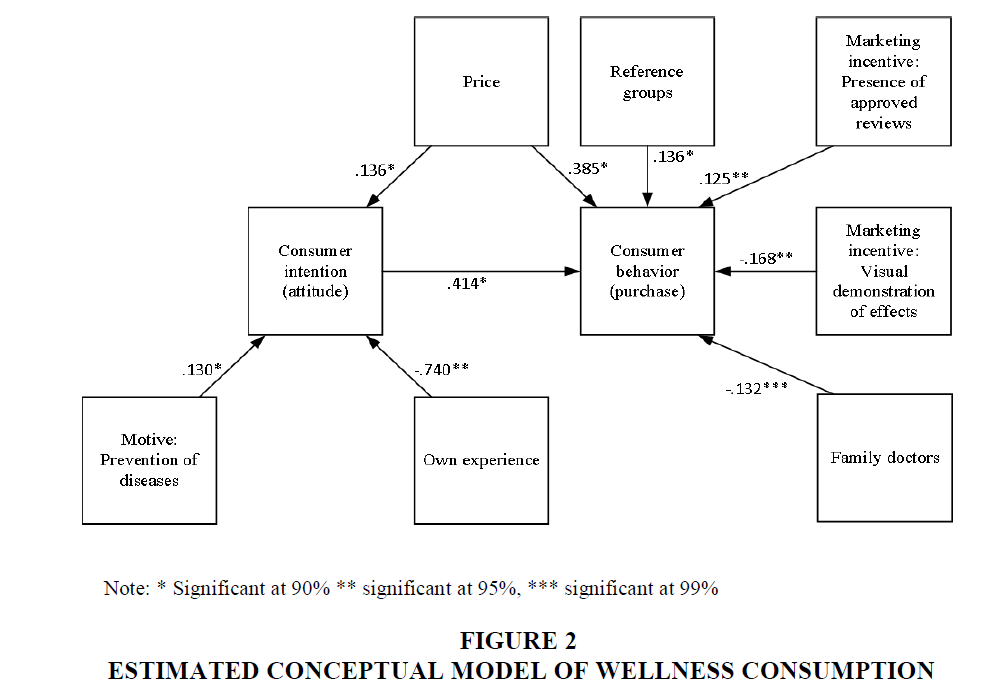

Correlation matrix showed no correlation or very weak correlation between factors included in the analysis (the average Pierson correlation coefficient is under 0.10; the maximum coefficient is 0.291) which makes it possible to analyze the data using moderated regressions models. Regression analysis was performed by forward step method that allowed to include in a regression model only factors with a given level of significance. The results of the analysis are presented in Figure 2.

Out of all internal and external factors only seven display sufficiently strong association with attitude towards the wellness concept and consumption of wellness goods and services to be used in the regression function. Firstly, we analyze factors influencing consumer intentions (Table 3). Among all motives included in the model (interest and pleasure of healthy way of life; self- development; prevention of diseases like diabetes, overweight, tooth decay, heart problems; body tone and care for appearance; dissatisfaction with the results of the use of traditional medicines; fashion influence; care for relatives and children) only one (Prevention of diseases) turned to influence wellness consumer intentions. All social factors like opinion leaders and reference groups do not influence consumer intention either-only own experience is significant for consumers. The negative influence of “own experience” factor means that those respondents who are accustomed to use only their own experience as a source of information negatively relate to the wellness concept.

| Table 3: Factors Influencing Consumer Intention (Attitude Towards The Wellness Concept) | ||||

| Factor | Non-Standardized ß | Standard error | Standardized ß | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motive: Prevention of diseases | 0,130 | 0.052 | 0.241 | 0.014* |

| Own experience | -0.740 | 0.52 | -0.139 | 0.057** |

| Price | 0.136 | 0.053 | 0.246 | 0.012* |

Note: * significant at 90% ** significant at 95%

Next, we analyze the impact of factors on the consumption of wellness goods and services. Among all the factors the following were recognized as significant in regression analysis (see Table 4).

| Table 4: Factors Influencing Consumer Behavior (Purchase Of Wellness Goods And Services) | ||||

| Factor | Non-Standardized ß | Standard error | Standardized ß | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference groups | 0.136 | 0.088 | 0.202 | 0.029* |

| Price | 0.385 | 0.089 | 0.391 | 0.050* |

| Marketing incentive: presence of approved reviews | 0.125 | 0.086 | 0.131 | 0.059** |

| Marketing incentive: visual demonstration of effects | -0.168 | 0.086 | -0.176 | 0.055** |

| Family doctors | -0.132 | 0.087 | -.0137 | 0.000*** |

Note: * significant at 90% ** significant at 95% *** significant at 99%

The strongest factor influencing consumer behavior (as well as consumer intention) is price (β=0.385, p<0.1). Quite unexpectedly, the influence of visual demonstration of effects (β=-0.168, p<0.05) and recommendations of family doctors (β=-0.132, p<0.01) is in a negative relationship with the resulting variable. The negative influence of “family doctors” factor may mean that “traditional” doctors are mainly negative about wellness products and services and do not recommend them to their patients.

According to the results of the regression analysis attitude towards the wellness concept has a moderately strong positive direct effect on consumption of wellness goods and services (β=0.414; sig=0.017<0.05), the explained variance is R2=0.56. Thus, hypothesis 4 is confirmed.

Hypothesis 1 is rejected

Gender, age and income level of the respondents statistically were not included in the regression model. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that such factors as “gender”, “income” and “age” are not significant in the study of the Russian market of wellness goods and services.

Hypothesis 2 is confirmed

The factors of reference groups and family doctors influence are significant in the regression model.

Hypothesis 3 is partly confirmed

Price factor has the strongest influence on the resulting variable. On the other hand, none of cultural factors were included in the final regression model.

Though this model of consumers’ behavior on the Russian wellness market explains the general consumption trends (factors influencing consumers when making purchasing decisions), it doesn’t reveal the segment structure of the market, which was one of the objectives of the study. Therefore, the next step in the methodology of the study should be the segmentation of Russian wellness market conducted by means of hierarchical cluster analysis in IBM SPSS.

Results Of Cluster Analysis

All experts interviewed during qualitative research agree that today Russian wellness market is characterized by presence of many small segments of consumers different in their socio- demographic and behavioral characteristics, types of consumer goods and services, terms of consumption, the type of involvement in the process of consumption, factors that have a decisive influence on purchasing decisions. The identification and description of such segments became a matter of further research.

The first important step in conducting cluster analysis is the choice of the clustering variable. We have selected the frequency of consumption and the duration of consumption as clustering variables because these characteristics show the involvement of consumers in the wellness lifestyle. There are many interpretations of the term “involvement of consumers”. Mittal & Lee (1989) singled out six main consequences of increased involvement, one of which is the increase in the frequency of use of products. Zaichkowsky (1994) defined the degree of involvement as the duration of continuous interaction of the consumer with the goods. Kapferer & Laurent (1986) consider the duration of consumption as one of the indicators of involvement, since engagement should be characterized by a strong long-term dependence.

The second important issue is determining the number of clusters. The table of agglomeration steps, the plot of the number of clusters and the degree of their heterogeneity, as well as the dendrograms show that greatest differences between clusters were revealed when three clusters (and 8 segments among them) were selected. Results of Welch’s Robust Tests of Equality of Means indicate that differences between the individual cluster means are statistically significant (at p<0.05) for all clustering variables.

Further clustering was carried out by the K-means method. For all analyzed variables, Chi- square and ANOVA tests of independence were performed. In all cases, the relations between members were characterized by significant numbers (p <0.05). The validity of author segmentation can also be judged from the result of the criterion R2, which describes what percentage of the frequency of purchases is explained by the factors included in the regression equation. The result for all segments is higher or close to 0.7, which is characterized as high determination.

Based on this analysis we can compile profiles of each of the identified clusters and segments by cross-tabulating the cluster membership variable and respondents’ demographic and behavioral characteristics as well as determinant and statistically significant factors influencing consumer behavior for each cluster (Table 5).

| Table 5: Segmentation Of Russian Wellness Consumers Based On Results Of The Empirical Study By Authors | ||||||||

| Frequency/ duration of consumption | Share in the aggregate sample | Title of the segment | Socio- demographic characteristics | Consumed goods/services | Influencing factors (Significance level) | R2 (adj) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | Segment 1 | Once in 3 months/5 years and more | 26 (5.00%) |

Wellness conservatives | 33% - ? 66% - F 67%> 46 years old |

Vitamins, diagnostic procedures | Price (0.037) Motive: Prevention of diseases (0.05) |

0.76 |

| Segment 2 | Once in 3 months/3-5 years |

49 (9.40%) |

Wellness ambassadors | 31% - ? 68% - F 82% - 36- 45 years old |

Vitamins, diagnostic procedures, enriched products, natural products |

Price (0.01) Marketing incentive: presence of approved reviews (0.06) Reference groups -0.037 |

0.81 | |

| Segment 3 | Once in 3 months/< 1 year | 69 (13.30%) |

Fitness enthusiasts | 53% - ? 47% - F 59% <25 years old |

Vitamins, enriched products, fitness | Marketing incentive: presence of approved reviews (0.02) Marketing incentive: visual demonstration of effects (0.015) | 0.88 | |

| Cluster 2 | Segment 4 | Once in 6 months/5 years and more | 47 (9.00%) |

Fashion victims | 50% - ? 50% - F 56% - 26- 35 years old Income>40000 rub./month |

natural products, enriched products, beauty procedures | Reference groups (0.05) Marketing incentives (0.09) |

0.67 |

| Segment 5 | Once in 6 months/2-3 years |

50 (9.60%) |

Interested newcomers | 55% - ? 45% - F 88% - 26 - 45 years old |

Vitamins, beauty procedures, dietary supplements | Reference groups (0.029) | 0.77 | |

| Segment 6 | Once in 6 months/ < 1 year | 52 (10.00%) |

Advertising victims | 55% - ? 45% - F 44% <25 years old |

diagnostic procedures, natural products, fitness, vitamins |

Brand advertising (0.04) | 0.84 | |

| Cluster 3 | Segment 7 | Once a year and less often/4 years and more | 97 (18.60%) |

Non- attracted followers | 41% - ? 59% - F 57% >46 years old |

Vitamins, wellness treatment, natural products | Motive: Prevention of diseases (0.003) Price (0.06) |

0.75 |

| Segment 8 | Once a year and less often/< 2 years | 129 (24.60%) |

Random consumers | 50% - ? 50% - F 67% < 35 years old |

Wellness treatment, diagnostic procedures | - | - | |

1) Segment 1 consists of aged wellness adherents, whose main incentive for using wellness products/services is prevention of diseases (46% of the representatives of the segment have indicated this incentive). On the one hand, these consumers can be called true followers of the wellness lifestyle as the term of their adherence is 5 years and more. The only significant factor for them is the price.

2) Segment 2 today can be identified as the foundation of the wellness lifestyle in Russia. Most of its’ representatives are of working age (82% -from 36 to 45 years) with a maximum income, they are actively interested in the concept of healthy lifestyle and related goods and services (as evidenced by the high value of social factors). It is interesting that the influence of reference groups on this segment has a negative effect on the frequency of consumption.

3) Segment 3 consists of young people interested in fitness and exercise. To improve their physical shape they use vitamins, fat burners, eco products. Brand advertising through reviews and visual demonstration of effects impacts them highly (Chao et al., 2015), the main incentive for using wellness products and services is to “support the body in good shape and good physical condition”.

4) The fourth segment can be called "fashion victims" because they are mostly affected by reference groups and brand advertising, promoting certain goods and services of the wellness sector (Terry, 2009). The representatives of this segment have a fairly high level of income to spend on the above-mentioned goods and services. The consumption of this segment is not structured, since they are buying anything that is fashionable at the given moment. This category of consumers will be most receptive to traditional marketing communications.

5) The fifth segment is made up of people who are beginning to take an interest in the wellness concept (it is indicated by the high influence of reference groups) and to buy relevant goods and services. This is one of the most promising segments in terms of the future of the industry.

6) The sixth segment consists of consumers whose behavior is determined by the influence of brand advertising (R2 = 0.84). Most of them are young people under 25 years old. They are interested in fitness, vitamins, natural products, but they cannot be called sustainable consumers as they are in the very beginning of their path to wellness lifestyle. The task of producers is to keep them on the way by means of advertising.

7) The seventh segment consists mainly of mature consumers and the elderly. They have been interested in the concept of healthy way of life for a long time but rarely buy appropriate products and services. The objective of manufacturing companies is to find out why and to influence them (mainly price).

8) The eighth segment consists of respondents who buy wellness products/services only occasionally. Their consumption is not systematical which was confirmed by the results of the regression analysis.

The final stage of the research should be devoted to the analysis of behavioral aspects of consumers of revealed segments. Most of the representatives of 1st and 2nd segments say that they are monitoring their health. It seems to be quite logical: the first adhere to a healthy lifestyle for a long time, for the latter the concept of wellness lifestyle is the essence of their lives now. For the same reasons, these two segments most often attract their environment to the healthy lifestyle (as well as representatives of the fifth segment). The representatives of 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 6th segments as the youngest representatives in the sample promote wellness in the Internet and social networks. All conclusions show that there are significant differences between the eight segments identified as a result of cluster analysis.

Conclusions, Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The results of the conducted analyses show conceptual features of the Russian wellness market. Among all groups of influencing factors identified during qualitative research only a few turned to be statistically significant for consumer attitude and behavior. Interestingly, different factors influence the attitude of consumers to the wellness concept and the consumption of corresponding goods and services, however, consumption is primarily determined by the attitude, therefore, it is important for producers to affect consumers through all groups of factors recognized to be significant in the study (see Figure 2). At the same time, price factors exert the strongest influence both on attitude and consumption, which reflects the low stage of development of wellness standard of consumption on the Russian market.

The analysis also included the division of Russian wellness consumers into 8 segments with the description of their socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics. This study helps to understand how the various segments make purchase decisions. The results of cluster analysis prove that wellness lifestyle in Russia is now only at the stage of formation, since even among the most “progressive” segments the frequency of consumption of wellness goods and services is 1 time per quarter. On the other hand, many segments have similar features. Segments 1st and 7th, 2nd and 5th, 3rd and 6th have a similar structure both in terms of the composition of consumed products and services, as well as demographic characteristics, influencing factors and duration of consumption. The difference is only in the frequency of consumption. Consequently, manufacturing companies can stimulate an increase in the frequency of consumption in segments 5th, 6th and 7th by impact through those factors that are significant for them (see Table 5). While realizing the marketing program for all segments it is crucial to focus on the driver products (vitamins and fitness) to attract new consumers. It is also quite important to develop a flexible system of discounts for various segments, to carry out the adaptation of price proposals for segments different in terms of income.

As to the directions of further research, a more detailed break-down of the behavioral wellness characteristics is needed including such environmental-health components as using wellness infrastructure, realizing wellness sports activities, visiting thematic exhibitions and so on to give some recommendations on wellness tourist facilities and advertising management.

In the process of data analysis, some limitations (also directions of future research) should be taken in consideration. Firstly, the results are limited by Saint-Petersburg region. Quantitative research should be conducted in different regions of Russia. As the wellness industry is constantly developing in Russia the research should be repeated to make the comparison of results.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior.Organizational behavior and human decision processes,50(2), 179-211.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc.

- Anilkumar, N., & Joseph, J. (2012). Factors Influencing the Pre-Purchase Attitude of Consumers: A Study.IUP Journal of Management Research,11(3).

- Ardell, D.B. (1977). High level wellness strategies.Health Education,8(4), 2-2.

- Blair, S.N., Kohl, H.W., Paffenbarger, R.S., Clark, D.G., Cooper, K.H., & Gibbons, L.W. (1989). Physical fitness and all-cause mortality: a prospective study of healthy men and women.Jama,262(17), 2395-2401.

- Brace-Govan, J. (2013). More diversity than celebrity: a typology of role model interaction.Journal of Social Marketing,3(2), 111-126.

- Callister, L.C., Getmanenko, N., Garvrish, N., Marakova, O.E., Zotina, N.V., & Turkina, N. (2009). Outcomes evaluation of St. Petersburg Russia women's wellness center.Health Care for Women International,30(3), 235-248.

- Chao, D.Y.P., Lin, T.M.Y., & Yeh, Y.F. (2015). How mobile intervention education can revolutionize wellness market and patient self-ecacy. InManagement, Information and Educational Engineering. CRC Press.

- Cherrier, H., Black, I.R., & Lee, M. (2011). Intentional non-consumption for sustainability: Consumer resistance and/or anti-consumption? European Journal of Marketing, 45 (11), 1757-1767.

- Cialdini, R.B., & Goldstein, N.J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 591-621.

- Cialdini, R.B., & Goldstein, N.J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 591-621.

- De Pelsmacker, P., & Janssens, W. (2007). A model for fair trade buying behaviour: The role of perceived quantity and quality of information and of product-specific attitudes.Journal of business ethics,75(4), 361-380.

- DiClemente, R., Nowara, A., Shelton, R., & Wingood, G. (2019). Need for innovation in public health research.American Journal of Public Health,109(S2), S117-S120.

- DiMaggio, P.J., & Powell, W.W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields.American Sociological Review, 147-160.

- Dolnicar, S., & Leisch, F. (2008). Selective marketing for environmentally sustainable tourism.Tourism management,29(4), 672-680.

- Duesenberry, J.S. (1949). Income, Savings and the Theory of Consumer Behavior. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Eagle, A. (2006). Fit for life. New facility helps Alabama hospital serve the wellness market. Health Facilities Management, 19 (8), 14-19.

- Engel, J.F., Kollat, D.T., & Blackwell, R.D. (1968). Consumer Behavior. Holt.Rinehart and Winston, New York.

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA.

- Gogia, J., & Sharma, N. (2012). Consumers’ compliance to adopt eco-friendly products for environmental sustainability. International Journal of Research in Commerce, Economics & Management, 2, 130-136.

- Goldman, S.M. (2011). The wellness prescription. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28, 87-91.

- Gould, S.J. (1990). Health consciousness and health behavior: the application of a new health consciousness scale. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 6(4), 228-237.

- Grunert, K.G., Hieke S. & Wills J. (2014) Sustainability labels on food products: consumer motivation, understanding and use. Food Policy, 44 (2014), 177-189.

- Hands, D.W. (2010). Stabilizing consumer choice: the role of ‘true dynamic stability’and related concepts in the history of consumer choice theory.The European journal of the history of economic thought,17(2), 313-343.

- Hawkins, D.I., Best, R.J., & Coney, K.A. (1992). Consumer Behavior: Implications for Marketing Strategy/5-th ed.Homewood, Ill.: Richard D. Irwin.

- Hopper, J.R., & Nielsen, J.M. (1991). Recycling as altruistic behavior: Normative and behavioral strategies to expand participation in a community recycling program.Environment and Behavior,23(2), 195-220.

- Howard, J.A., & Sheth, J.N. (1969). The theory of buyer behavior.New York.

- Hughner, R.S., McDonagh, P., Prothero, A., Shultz, C.J., & Stanton, J. (2007). Who are organic food consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food.Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review,6(2-3), 94-110.

- ing: How to build psychologically healthy

- ing: How to build psychologically healthy

- ing: How to build psychologically healthy

- Jansson, J., Marell, A., & Nordlund, A. (2010). Green consumer behaviour: determinants of curtailment and eco-innovation adoption. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 27 (4), 358-370.

- Kapferer, J., & Lauren, G. (1986). Consumer Involvement Profiles: a New Practical Approach to Consumer Involvement. Journal of Advertising Research, 6, 48-56.

- Katona, G. (1951) Psychological Analysis of Economic Behavior. NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Kraft, F.B., & Goodell, P.W. (1993) Identifying the health-conscious consumer. Journal of Health Care Marketing, 13(3), 18-25.

- Laczó, T., & Ács, P. (2009). Spatial characteristics of the Hungarian wellness market’s demand and supply relations.World Leisure Journal,51(3), 197-210.

- Leiserowitz, A.A., Kates, R.W., & Parris, T.M. (2006). Sustainability values, attitudes, and behaviors: A review of multinational and global trends.Annual Review of Environment and Resources,31, 413-444.

- Leonidou, L.C., Leonidou, C.N., Palihawadana, D., & Hultman, M. (2011). Evaluating the green advertising practices of international firms: a trend analysis.International Marketing Review,28(1), 6-33.

- Maynard, L.J., & Franklin, S.T. (2003). Functional foods as a value-added strategy: The commercial potential of “cancer-fighting” dairy products.Review of Agricultural Economics,25(2), 316-331.

- Michaelidou, N., & Hassan, L.M. (2008). The role of health consciousness, food safety concern and ethical identity on attitudes and intentions towards organic food. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 32 (2), 163-170.

- Mittal, B., & Lee, M.S. (1989). A causal model of consumer involvement.Journal of Economic Psychology,10(3), 363-389.

- Mohr, J.J., Sengupta, S., & Slater, S. F. (2010).Marketing of high-technology products and innovations. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Moisander, J. (2007). Motivational complexity of green consumerism.International Journal of Consumer Studies,31(4), 404-409.

- Nicholson, M., & Xiao, S.H. (2011). Consumer behaviour analysis and social marketing practice.The Service Industries Journal,31(15), 2529-2542.

- of a healthy workplace. In A. Day, E. K. Kello-

- of a healthy workplace. In A. Day, E. K. Kello-

- of a healthy workplace. In A. Day, E. K. Kello-

- Pilzer, P.Z. (2007). The new wellness revolution.NY, John Wiley&Sons.

- Reingen, P.H., & Kernan, J.B. (1986). Analysis of referral networks in marketing: Methods and illustration.Journal of Marketing Research,23(4), 370-378.

- Sawyer, E.N., Kerr, W.A., & Hobbs, J.E. (2008). Consumer preferences and the international harmonization of organic standards.Food Policy,33(6), 607-615.

- Schor, J.B. (1991). The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure. New York: Basic Books.

- Schwartz, S.H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values?.Journal of social issues,50(4), 19-45.

- Shabunina, T.V., Shchelkina, S.P., & Rodionov, D.G. (2017). An innovative approach to the transformation of eco-economic space of a region based on the green economy principles.Academy of Strategic Management Journal,16, 176-185.

- Shchepinin, V.E., Leventsov, V.A., Zabelin, B.F., Konnikov, E.A., & Kasianenko, E.O. (2017). The content aspect of the tendency to reflect the actual result of management. In2017 6th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions) (ICRITO), IEEE.

- Shoham, A., & Ruvio, A. (2008). Opinion leaders and followers: A replication and extension.Psychology & Marketing,25(3), 280-297.

- Solnick, S.J., & Hemenway, D. (2009). Do spending comparisons affect spending and satisfaction?The Journal of Socio-Economics,38(4), 568-573.

- Sun-Waterhouse, D. (2011). The development of fruit-based functional foods targeting the health and wellness market: a review.International Journal of Food Science & Technology,46(5), 899-920.

- Terry, M. (2009). The personal health dashboard: consumer electronics is growing in the health and wellness market.Telemedicine and e-Health,15(7), 642-645.

- Vermeir, I., & Verbeke, W. (2006). Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer attitude-behavioral intention gap.Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics,19(2), 169-194.

- Viardot, E. (2004).Successful marketing strategy for high-tech firms. Artech House.

- way, & J. J. Hurrell (Eds.), Workplace well-be-

- way, & J. J. Hurrell (Eds.), Workplace well-be-

- way, & J. J. Hurrell (Eds.), Workplace well-be-

- workplaces. (pp. 27–49). London, UK: Wiley

- workplaces. (pp. 27–49). London, UK: Wiley

- workplaces. (pp. 27–49). London, UK: Wiley

- Yuldasheva, O.U. (2006). Cognitive marketing: Fundamentals and terminological apparatus.Marketing, (1-2), 34-43.

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. (1994). The personal involvement inventory: Reduction, revision, and application to advertising.Journal of Advertising,23(4), 59-70.

- Zografos, C. (2007). Rurality discourses and the role of the social enterprise in regenerating rural Scotland.Journal of Rural Studies,23(1), 38-51.