Research Article: 2022 Vol: 26 Issue: 2S

Consequences of a negative MONEYVAL evaluation for the national economy

Jelena Zigulica, RISEBA University of Applied Sciences

Ilmars Kreituss, RISEBA University of Applied Sciences

Karlis Danevics, SEB Bank Latvia

Keywords

FATF Recommendations, MONEYVAL Assessment, FATF Grey List, Anti-Money Laundering (AML), Foreign Direct Investment

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to analyze the impact of a negative MONEYVAL evaluation of national Anti-Money Laundering (AML) systems on a country’s economy. MONEYVAL, as an international AML monitoring body, plays an important role in identifying gaps in national AML systems. A negative MONEYVAL evaluation of a country can potentially lead to inclusion in the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) list (grey list), which, according to some authors, may have a harmful economic effect on the whole national economy. More than 40 countries were included in the FATF’s grey list at least once in the last ten years (e.g. Argentina, Greece, Serbia, Albania, Iceland). Several countries (e.g. Latvia) have received a negative MONEYVAL evaluation and a warning about inclusion in the FATF’s grey list. The aim of this research is to examine how a negative MONEYVAL report and inclusion in the FATF’s grey list affects a country’s economy. The research is focused on the effect of three important economic indicators (Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), the sovereign credit rating of the country and the government borrowing interest rate). The effect of inclusion in the grey list has been studied for seven countries whose economies are arguably most similar to Latvia’s (Albania, Azerbaijan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Iceland, Kyrgyzstan, Serbia and Tajikistan). The Latvian government’s efforts to become compliant with the FATF’s recommendations during a period of enhanced MONEYVAL monitoring after its negative assessment have been considered and the impact of these efforts on the banking sector has been analysed. The study shows that despite the negative expectations that after inclusion in the FATF’s grey list a country’s economic development may be negatively affected, grey-listing in general does not have an immediate negative effect on economic indicators: FDI does not decrease, credit ratings of countries mostly do not deteriorate, and government borrowing interest rates do not increase. The case of Latvia also shows that too sharp implementation of all the FATF’s recommendations has a harmful impact on the national banking sector and can lead to negative consequences.

Introduction

Over the past few decades money laundering and terrorist financing have become increasingly ubiquitous issues which both financial institutions and governments worldwide are actively trying to combat. According to a study conducted by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in 2009, criminal proceeds amounted to 3.6% of global GDP, with 2.7% (or USD 1.6 trillion) being laundered (FATF, 2019f). Current estimates of the amount of money laundered worldwide range from $500 billion to a staggering $1 trillion, with disastrous effects on the global economy, especially on vulnerable, developing economies (European Council, 2017).

The main role in anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) efforts is played by effective surveillance of financial institutions. Regulatory and monitoring bodies ensure that financial institutions do not fall under the control of criminals and are not used for illicit purposes. Transparency and the legality of operations in national financial systems is more important than ever, since money laundering and terrorist financing continue to cripple economies, distort international finances and harm citizens around the globe (International Center for Asset Recovery, 2018).

One of the organizations actively helping to improve surveillance systems is MONEYVAL, an independent international monitoring body established in 1997 to help reduce risks to the global financial system, identify gaps in national AML/CFT systems and actively follow up on the progress countries make to rectify them (European Council, 2017). MONEYVAL reports directly to the Committee of Ministers (Council of Europe, 2019a). Currently it consists of 47 member states. It is one of the leading FATF-style regional bodies that work in close cooperation with the FATF. Initially it was an observer and became an associate member of the FATF in June 2006 (FATF, 2019b).

The AML/CFT problem became of greater importance following the event on September 11, 2001, after the United States introduced the Patriot Act, leading to the restriction of supervision of AML matters globally. However, a coordinated effort in fighting international money laundering had already started with the establishment in 1989 of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an independent intergovernmental organization, at the G7 economic summit held in Paris (Anderson & Anderson, 2015): “Its purpose is to develop and promote national and international strategies to combat money laundering” (Hopton, 2009). In 2002, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) together with the World Bank and FATF decided on a common method for assessment of compliance with FATF recommendations. The FATF’s recommendations have become the global standard for effective national and international combating of money laundering and terrorist financing. The recommendations set a minimum requirement for actions that should be taken by countries to fight financial crime, taking into consideration their local legal and constitutional frameworks (Alkaabi et al., 2010).

The FATF’s 40 recommendations cover all possible countermeasures against money laundering and terrorist financing. This is a minimum standard for countries to reach taking into consideration their particular circumstances and legal frameworks (ACAMS, 2019).

The purpose of MONEYVAL is “to ensure that its member states have in place effective systems to counter money laundering and terrorist financing and comply with the relevant international standards in this matter” (Council of Europe, MONEYVAL in brief, 2019c). MONEYVAL’s peer evaluation system is based on the FATF’s methodology; however, the assessment process is more extensive, since, besides assessing compliance with the FATF’s standards, MONEYVAL evaluates the compliance of its jurisdictions with the related EU legislation and international conventions. The assessment process of member states is based on evaluation rounds (Council of Europe, Statutory documents, 2019b). According to Nance (2017a), this is considered one of the most extensive methods of monitoring. All deficiencies are well documented, yet a prosecution remains rare. So far MONEYVAL has performed four rounds of mutual evaluations and in 2015 it started its 5th round. For each round, evaluations of MONEYVAL states and regions generate mutual evaluation reports. Assessments concentrate on two areas: effectiveness and technical compliance. The emphasis of any assessment is on effectiveness. The team of experts checks 11 key AML/CFT areas to determine the level of effectiveness of a country’s efforts. The assessment also looks at whether a country has met all the technical requirements of each of the 40 FATF Recommendations in its laws and regulations.

Since its very beginning, the FATF has had a practice of “naming and shaming” states that have inadequate anti-money laundering controls or are not collaborative in AML/CFT efforts. It was actively involved in an initiative to detect non-cooperative countries and territories (NCCTs) in the global struggle against money laundering (ACAMS, 2019).

The FATF achieves its goal–to strengthen the financial system–by ensuring that global AML/CFT standards are adopted by all financial centres, identifying problematic jurisdictions in two documents and openly publishing them.

The first one–the FATF’s Public Statement or so-called “blacklist”–identifies countries with strategic deficiencies that are so serious the FATF calls on its members and non-members to apply countermeasures. Since the inception of the process, only North Korea and Iran have been blacklisted (Nance, Re-thinking FATF: an experimentalist interpretation of the Financial Action Task Force, 2017a).

The second is the so-called “grey list” and includes countries based on whether they are cooperative or uncooperative, not whether they are compliant or non-compliant (Nance, 2017). If a country fails to make sufficient or timely progress, the FATF can increase its pressure on the country by moving it to the Public Statement (ACAMS, 2019). But so far, no country has ever been moved to the blacklist (Nance, Re-thinking FATF: an experimentalist interpretation of the Financial Action Task Force, 2017a). There are 22 countries currently on that FATF’s grey list (FATF, 2021). The results of the evaluation are publicly available and have a crucial role in reflecting the compliance of each specific jurisdiction. According to general opinion, a negative report can have detrimental economic effects: banks risk losing access to the global financial architecture and investments may decrease (European Council, 2017). However, some evidence suggests that market activity does not respond strongly to blacklisting (Nance, 2017a) and, since inclusion in FATF lists is a soft law arrangement with no fine or penalty for blacklisted countries, intergovernmental organizations can only expect that the international community will react and punish listed countries by withdrawing them from business and by reducing exports or imports. It can only be hoped that serious banks will avoid dealing with them (Unger & Ferwerda, 2008). Some researchers argue that strengthening of enforcement within the FATF is “likely to be counter-productive, while reinforcing social learning and peer review are more likely to generate greater returns” (Nance, The regime that FATF built: an introduction to the Financial Action Task Force, 2017b).

The aim of this research is to examine whether a negative MONEYVAL assessment of a country and inclusion in the FATF’s grey list may negatively affect the country’s economy. The research is focused on the effect of three economic indicators (foreign direct investment, the sovereign credit rating of the country and the government borrowing interest rate) which are most often mentioned as the most sensitive to inclusion in the FATF’s grey list. The effect of inclusion in the grey list has been studied for seven countries which historically or economically are arguably most similar to Latvia (Albania, Azerbaijan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Iceland, Kyrgyzstan, Serbia and Tajikistan). Following a negative MONEYVAL assessment, Latvia became subject to enhanced MONEYVAL monitoring, but after strong efforts carried out by governmental institutions to become compliant with the FATF’s recommendations, it was not included in the FATF’s grey list. The impact of these strong measures on the Latvian banking and finance sector has been analysed.

Materials and Methods

Both qualitative and quantitative data has been collected and analysed. The authors have investigated which economies in the last ten years have been grey-listed for the first time. As one of the tasks of the research is to understand what consequences could be expected for Latvia if warned about inclusion in the grey list, seven countries whose economies are similar to the Latvian economy were chosen for deeper analysis.

For these chosen countries the effect was examined on the following three indicators: sovereign credit rating, amount of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and state borrowing interest rates (for all countries besides Bosnia-Herzegovina, changes in T-bill rates have been considered; for Bosnia-Herzegovina, due to the absence of T-bills, the real interest rate was taken).

In order to evaluate the effect specifically on the Latvian economy and banking sector, the authors studied and analysed available secondary data about the Latvian banking sector and conducted interviews with highly qualified experts. Four professionals were selected for the interviews according to the following criteria: A university degree in finance and economy, at least 15 years of experience in top positions in finance institutions, and specialisation in AML matters.

Expert 1: A member of the Management Board of the Finance Latvia Association. Extensive experience in banking, especially legal affairs, including in matters regarding the prevention, licensing and restructuring of money laundering and terrorism financing. For 12 years, Deputy Chairman of the Financial and Capital Market Commission.

Expert 2: Co-chair of the Lending Committee of the Finance Latvia Association, Board Member of SEB Bank Latvia, responsible for AML and KYC matters. Member of various international credit committees for more than 15 years.

Expert 3: Co-chair of the Finance Latvia Association, Chairperson of the Management Board of Baltic International Bank.

Expert 4: For 7 years, advisor to the International Relations and Communication Department of the Bank of Latvia. Former chief economist at Nordea Bank Finland PLC, Latvia branch, transactions manager at Price water house Coopers Ltd.

Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured, in-depth approach with open-ended questions and were recorded; afterwards, they were analysed and interpreted. Interview questions were focused on finding out the possible grey-listing effect on countries and on the banking sector and, in relation to the influence on countries, were asked with the aim of understanding how certain economic indicators might be affected. Questions on the banking sector were aimed at understanding experts’ opinion on how the banking sector might react to inclusion in the FATF’s list, how financial indicators might change, and in what way MONEYVAL recommendations have impacted the banking sector and the economy. The analysis of the obtained data represents a consolidation and mapping of information from academic resources, secondary data and results of the interviews with experts.

Results

Impact on Countries’ Inclusion in the FATF’s Grey List

More than 40 countries have appeared in the FATF’s grey list at least once in the last ten-year period. From this grey list, we chose 7 countries whose economies are arguably most similar to the Latvian economy: Albania, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Iceland, Kyrgyzstan, Serbia AND Tajikistan. It was not possible to obtain historical data for all of them on all three indicators for the relevant period, as, for instance, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan received their first credit rating after the reviewed period, which makes it impossible to relate this to the effect of a negative country evaluation by FATF-style regional bodies.

Albania

Albania appeared in the “Improving Global AML/CFT Compliance: On-going Process” list on 22 June 2012 after its negative evaluation by MONEYVAL. Albania was evaluated as partially compliant with 22 recommendations; largely compliant with 12, compliant with 3, non-compliant with only 2 and 1 recommendation was considered non-applicable. (Council of Europe, Report on Fourth Assessment Visit–Executive Summary (Albania, 2011a). It was later considered compliant with FATF recommendations, on 27 February 2015. Regarding the special recommendations, Albania was considered non-compliant with only one and partially compliant with the rest this makes Albania the most similar to Latvia in the given MONEYVAL evaluation.

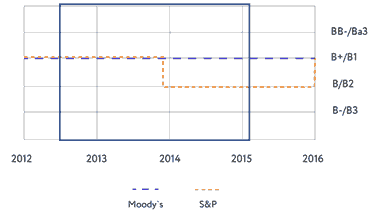

The S&P rating was downgraded from B+ (with a stable outlook) in 2010 to B (with a negative outlook) in 2013 and was upgraded back to B+ (with a stable and later even positive outlook) in 2016, when Albania was excluded from the grey list. At the same time, Moody’s credit rating stayed unchanged (B1) during the whole period of inclusion (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Credit Rating History – Albania (2012-2016) (Countryeconomy.Com, 2019)

In the case of Albania, the rating results are ambiguous, as both deterioration and an unchanged rating are observed during the period of inclusion in the list.

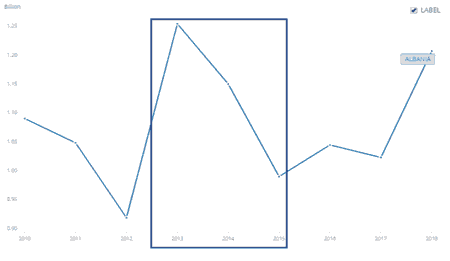

Foreign direct investment bottomed out in 2012 and began to climb swiftly, peaking in 2013. After the year 2013, it decreased steadily till 2015, when Albania was excluded from the FATF list (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Foreign Direct Investment, Net Inflows – Albania (2010-2018), Billion USD (World Bank, Foreign Direct Investment, Net Inflows - Albania, 2019b)

But the overall trend, if compared to the period before inclusion, is increasing FDI. It can be concluded that FDI decreased shortly before inclusion. The surge of FDI in 2013 was mostly due to the privatization of four hydropower plants and to the acquisition of a 70% share in the main oil-refining corporation (United Nations, World Investment Report 2014: Investing in the SDGs: An Action Plan, 2014; European Commission, 2014). Albania has also positively differed from neighbour states, experiencing a decrease in FDI in the same year, “because of its investor-friendly business environment and opportunities opened up by the privatization of State-owned enterprises” (United Nations, World Investment Report 2013, 2013).

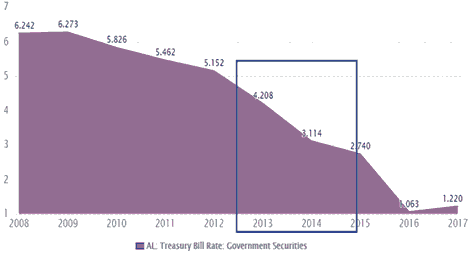

Albania’s Treasury bill interest rates were shrinking, staring at 6.3% in 2009 and reaching 1% in November 2016. During the period of inclusion in the FATF’s grey list, interest rates fell from 4.5% to 2.7% (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Treasury Bill Rate – Albania (2008-2017), % (CEIC, Albania Treasury Bill Rate, 2019e)

It can be concluded that inclusion in the FATF’s grey list did not have any negative effect on Albania’s interest rates, which did not increase but actually fell (see Figure 3).

Albania’s inclusion in the FATF’s grey list did not reduce foreign direct investment and interest rates actually decreased. The impact on credit ratings is ambiguous, as both deterioration and an unchanged rate are observed during the period of inclusion.

Azerbaijan

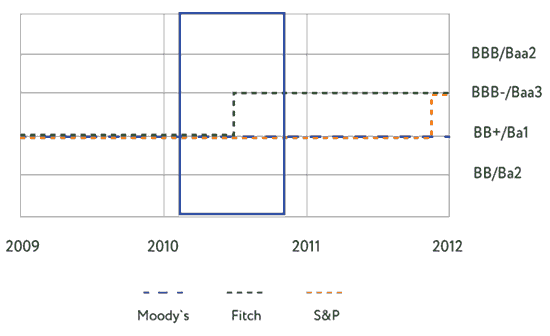

Azerbaijan appeared in the “Improving Global AML/CFT Compliance: On-going Process” list on 18 February 2010 after its evaluation by MONEYVAL and stayed there till 22 October 2010. It received the following evaluations: 16 non-compliant, 16 partially compliant, 5 largely compliant, 2 not applicable and 1 compliant. Regarding the nine special recommendations, it received 6 partially compliant evaluations and 3 non-compliant evaluations (Council of Europe, Mutual Evaluation Report – Executive Summary (Azerbaijan, 2008). When looking at the change in the sovereign credit rating of Azerbaijan, it can be concluded that Moody’s stable Ba1 rating with a positive outlook granted on 19 June 2009 was still unchanged even on 8 March 2011, after the FATF-related events affecting Azerbaijan took place. Also, on 20 May 2010, Fitch granted it a BB+ sovereign credit rating with a stable outlook. In 2011, after the country was no longer in the grey list, Moody’s and S&P’s rating stayed unchanged and Fitch’s improved from BB+ to BBB- (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Credit Rating History–Azerbaijan (2009-2012) (Fx Empire, 2019)

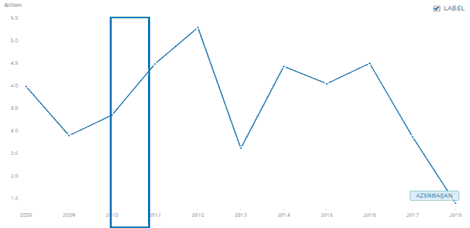

Foreign direct investment in Azerbaijan started to grow in 2009 and experienced even more rapid growth from 2010 till 2012. Thus, it can be concluded that grey-listing had no negative effect on Azerbaijan’s FDI. It decreased rapidly only in 2013, which was clearly caused by other events (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Foreign Direct Investment, Net Inflows – Azerbaijan (2008-2018), Billion USD (World Bank, 2019a)

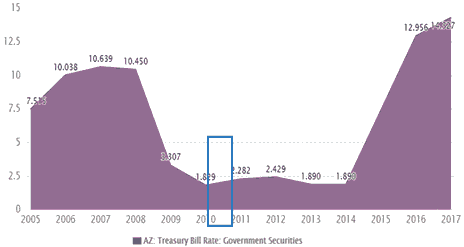

The interest rate experienced a slight increase from 1.8% to 2.3% right after exclusion. This can be considered quite a minor change in comparison with the much greater rapid growth observed from the year 2014 till the year 2017, which cannot be connected to the inclusion in the FATF’s grey list (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Treasury Bill Rate – Azerbaijan (2005-2017), % (Ceic, 2019d)

Thus, inclusion of Azerbaijan in the FATF’s grey list did not reduce the country’s credit ratings, only slightly affected the interest rate, and rather than decreasing, foreign direct investment actually grew.

Bosnia-Herzegovina

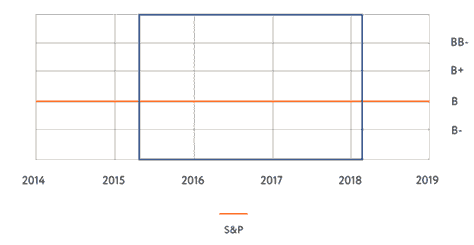

As a result of the MONEYVAL evaluation process, Bosnia-Herzegovina was rated as non-compliant with 13 recommendations and partially compliant with 18 recommendations, including some fundamental and essential recommendations, and the country was under enhanced monitoring during the period from 17 April 2015 to 23 February 2018. During this period, the S&P rating stayed unchanged at B (with a stable outlook), so inclusion in the FATF grey list did not affect it (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Standard and Poor’s Credit Rating History – Bosnia-Herzegovina (2014-2019) (the Central Bank of Bosnia-Herzegovina, 2019b)

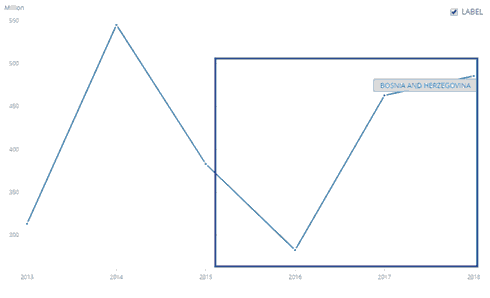

Foreign direct investment already started to decrease in 2014, before the inclusion of Bosnia-Herzegovina in the FATF’s list, and continued to do so afterwards, reaching its lowest point in 2016 and growing again steeply subsequently (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Foreign Direct Investment, Net Inflows – Bosnia-Herzegovina (2013-2018), Million USD (World Bank, Foreign Direct Investment, Net Inflows - Bosnia And Herzegovina, 2019c)

Thus, the changes in FDI most likely were not caused by the MONEYVAL evaluation and overall, it actually increases during this period.

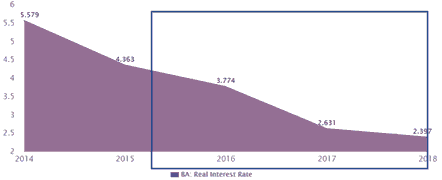

Interest rates during the period of inclusion in the FATF’s list decreased from around 4% to 2.4% and were therefore not affected noticeably by such inclusion. A decrease was observed even before inclusion (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Bosnia-Herzegovina Real Interest Rate (2014-2018), % (Ceic, Bosnia and Herzegovina Real Interest Rate, 2019f)

Thus, despite the negative MONEYVAL evaluation, no negative consequences appeared in Bosnia-Herzegovina during the entire monitoring period.

Serbia

Serbia appeared in the FATF’s grey list on 9 June 2016 and was closely monitored till 21 June 2019. During the onsite visit it was evaluated and received “Moderate” or “Low” grades on its effectiveness (even on international cooperation criteria). Regarding technical compliance, Serbia received 16 partially compliant, 20 largely compliant, 1 non-compliant and 3 compliant evaluations. This makes Serbia broadly similar to Latvia in the given MONEYVAL evaluation.

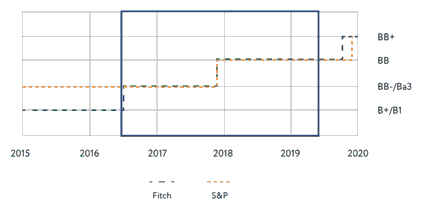

In the assessed time period Serbia’s credit rating was not negatively affected. Standard and Poor’s rating stayed at BB- and improved to BB with a positive outlook at the moment of exclusion. Fitch’s ratings during the inclusion process improved from BB- to BB+. Before inclusion, the rating was B+, which is lower than after Serbia appeared in the FATF’s list (see Figure 10).

Figure 10: Serbia’s Sovereign Credit Rating History – Standard and Poor’s and Fitch (2014-2019) (National Bank of Serbia, 2019)

There is a tendency of growing foreign direct investment for Serbia during the whole period of its inclusion in the grey list. Thus, no negative effect on FDI can be observed. Before inclusion there was, however, a slight decrease in investment (see Figure 11).

Figure 11: Foreign Direct Investment, Net Inflows – Serbia (2015-2019), Million EUR (Ceic, Serbia Foreign Direct Investment: Flow, 2019b)

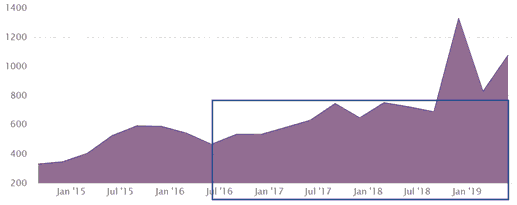

There was also a decrease in the interest rate during the period of inclusion in the FATF’s grey list from June 2016 till June 2019. The interest rate declined from 7% to 3.4%. It started to fall even before inclusion. Thus, no negative effect on it can be seen (see Figure 12).

Figure 12: Treasury Bond Interest Rate – Serbia (2015-2019), % (Investing.Com, 2019)

After the negative MONEYVAL evaluation of Serbia, no negative effects were observed during the entire monitoring period. In fact, credit ratings and FDI increased and interest decreased.

Iceland

On 18 October 2019, Iceland became the first European Economic Area country to be included in the FATF’s grey list regarding insufficiently effective implementation of recommendations for the prevention of money laundering and terrorist financing. Although the FATF acknowledged that Iceland had proactively taken steps to comply with the formal requirements, this was not enough to escape the grey list. The FATF identified a large number of shortcomings in the prevention of money laundering and terrorist financing. Iceland was criticized, for example, for its lack of control over the large-scale cross-border movement of cash and cooperation with shell companies. Iceland had not enacted legislation to effectively execute foreign requests to freeze or confiscate funds. Deficiencies in the implementation of international sanctions were also criticized. The FATF found that the work of financial intelligence agencies was superficial, subjecting only a few major state-owned banks to control.

About a month after inclusion on the grey list, the international credit agency Standard & Poor’s rated Iceland at “A” or stable. Standard & Poor’s stated that inclusion was not expected to have any material impact on the financial status or reputation of Icelandic banks and expressed confidence that the state would implement improvements quickly. Fitch also kept its credit rating unchanged, and Moody’s even raised it (see Figure 13).

Figure 13: Sovereign Credit Rating, Government Borrowing Rates and Foreign Direct Investment History – Iceland

Government borrowing rates continued to decline as before inclusion of Iceland in the FATF’s grey list, reached their lowest point in the middle of 2020, and then started to grow. In general, borrowing rates did not increase during the grey-list period (see Figure 13).

Foreign direct investment for Iceland fluctuated during the whole period of its inclusion in the grey list, experiencing both increases and decreases. Overall, there was only a slight decrease in FDI during the grey-list period; it cannot be ruled out that this was due to other factors (see Figure 13).

From all the examinations performed by the authors in order to evaluate the effect on economies after inclusion in the FATF’s grey list, it can be concluded that there is no direct immediate negative effect on a country’s sovereign credit rating or on foreign direct investment and government borrowing interest rates. The results are summarized in Table 1 below.

| Table 1 Summary of the Comparison of Countries Included in the Fatf’s Grey List |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Inclusion period | MONEYVAL Ratings | Credit rating | FDI | Interest rate | ||||

| NC | PC | C | LC | NA | |||||

| Azerbaijan | 2010-02-18 – 2010-10-22 | 16 | 16 | 1 | 5 | 2 | No change/Improved | Increased | Increased slightly |

| Tajikistan | 2011-06-24 –2014-10-24 | 30 | 5 | - | 2 | 3 | N/A | Increased | Decreased |

| Kyrgyzstan | 2011-10-28 –2014-06-27 | 9 | 16 | 5 | 8 | 2 | N/A | Increased | Decreased |

| Albania | 2012-06-22 –2015-02-27 | 2 | 22 | 3 | 12 | 1 | No change/ Deteriorated | Increased | Decreased |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | 2015-04-17 –2018-02-23 | 21 | 18 | - | - | - | No change | Increased | Decreased |

| Serbia | 2016-06-09 –6/21/2019 | 1 | 16 | 3 | 20 | - | Improved | Increased | Decreased |

| Iceland | 2019-10-18 –2020-10-23 | 2 | 16 | 5 | 10 | - | No change/Improved | Increased/Decreased | Decreased |

| Latvia | Period of enhanced monitoring 2018-08-23 –2020-02-23 | 0 | 10 | 6 | 24 | - | No change/Improved | Increased | Decreased |

It can be concluded that credit ratings were mostly not negatively affected by the countries’ inclusion in the FATF’s “Improving Global AML/CFT Compliance: On-going Process” list. Ratings either improved at the moment of inclusion in the list or stayed unchanged (as in the case of Azerbaijan, Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina). An ambiguous effect is seen in Albania’s credit rating being downgraded from B+ to B by one agency (S&P) while experiencing no change in the evaluation by another (Moody’s). Mostly, the expected decrease in foreign direct investment indicators and increase in interest rates did not occur.

From the above, the authors have made the conclusion that inclusion in the FATF’s grey list does not have a major negative effect on such significant economic indicators as credit rating, foreign direct investment and interest rates, since after the event takes place no essential negative effect is observed.

Impact on Latvia, Warned but not included in the FATF’s Grey List

MONEYVAL’s 5th Report 2018

Latvia is a member of the MONEYVAL Committee of Experts on the Evaluation of Anti-Money Laundering Measures and the Financing of Terrorism of the Council of Europe. In the fifth round of evaluations (from 30 October to 10 November 2017), a team of experts from the MONEYVAL Committee made an onsite visit to Latvia to assess the progress of the AML/CFT system. For the first time, the committee evaluated both the technical compliance and operational efficiency of Latvia’s system.

The MONEYVAL Committee assesses effectiveness in 11 AML/CFT areas. The result of the assessment published on 23 August 2018 showed that the Latvian ML/TF prevention system is substantial in one area, moderate in 8 areas and low in 2 areas. In accordance with the requirements of the MONEYVAL evaluation procedure, Latvia became subject to enhanced MONEYVAL monitoring, which obliges it to submit a progress report after one year and to describe actions taken in response to the recommendations made (FIU of Latvia, 2019b). The committee found that the Latvian government had cooperated effectively with its foreign counterparts to share financial and legal intelligence and to launch joint investigations on AML/CFT. In 2018, the Control Service received 644 requests from colleagues from 57 foreign units, while 443 requests were sent to 56 units. The number of requests sent in 2018 is the highest in the history of the Control Service (FIU of Latvia, Supplemented Latvian National money laundering/terrorism financing risk assesment report, 2018). In the areas of risk and coordination, supervision, preventive measures, financial intelligence, investigation and prosecution of money laundering, confiscation, investigation and prosecution of terrorist financing, preventive measures towards financing of terrorism and financial sanctions, the effectiveness of the Latvian AML/CFT system is assessed as moderate. Latvia needs to create a mechanism that obliges financial institutions and certain non-financial entities to identify the beneficial owners of their clients and to actively verify the information obtained. The recommendations call for the strengthening of supervisory authorities, while giving priority to the compliance of supervisory authorities with the requirements to prevent financing of proliferation.

In the technical compliance assessment, Latvia was rated as compliant with 6 Recommendations, largely compliant with 24, and partially compliant with 10 and did not receive any “non-compliant” evaluation. Overall, Latvia’s technical compliance rating is high.

In two areas, the level of effectiveness was assessed as low: the areas of legal persons and arrangements and proliferation of financial sanctions. The government recognized that fundamental improvements were needed to improve the situation regarding the 10 recommendations which were evaluated as partially compliant. Technical compliance includes the necessary national legislation and guidelines, criminal responsibility for AML/CFT and proliferation, and cooperation between relevant authorities at a national and international level to achieve these goals (Cabinet of Ministers, 2018a). In the report MONEYVAL also noted that “large financial flows going through Latvia as a regional financial centre posed a significant threat. Even though the Finance Intelligent Unit (FIU) and the Financial Capital Market Commission have a rather extensive understanding of the risks within the AML/CFT area, there is inadequate appreciation of the potentially ML-related cross-border flows of funds passing through Latvia” (MONEYVAL, Latvia. Fifth Round Mutual Evaluation Report, 2018b).

The Committee emphasized in their findings that until recently, the judicial system of Latvia did not appear to consider ML as a priority and to approach ML in line with its risk profile. Latvia’s legal basis for targeted financial sanctions needed urgent clarifications and improvements as a risk-based-approach was not followed (MONEYVAL, Latvia. Fifth Round Mutual Evaluation Report, 2018).

Actions taken to close the Gaps

In order to implement MONEYVAL’s recommendations, on 11 October 2018 the Latvian government adopted the Action Plan to Prevent Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing for the time period till 31 December 2019 (Cabinet of Ministers, Finanšu sektora attistibas padome konceptuali atbalstijusi pasakumu planu noziedzigi iegutu lidzeklu legalizacijas un terorisma finansešanas noveršanai, 2018b). The main focus areas were as follows: increase the capacity of supervisory authorities; strengthen the awareness of relevant public sector institutions and the private sector about the risks of money laundering; develop guidelines that will ensure a unified approach to investigating the laundering of proceeds derived from criminal activity and the provision of the necessary evidence; review the reporting system for unusual and suspicious transactions; improve the institutional and private sector understanding of targeted financial sanctions, etc. (Cabinet of Ministers, Finanšu sektora attistibas padome konceptuali atbalstijusi pasakumu planu noziedzigi iegutu lidzeklu legalizacijas un terorisma finansešanas noveršanai, 2018b). In order to implement MONEYVAL’s recommendations, Latvian government took proactive steps to improve Latvia’s AML/CFT legal framework and strengthen the top management of key financial institutions. The heads of the Finance Intelligent Unit (FIU), the Financial and Capital Market Commission (FCMC) and the Central Bank of Latvia were dismissed and new persons were appointed. In a short time it made meaningful progress in 10 of the 11 areas identified by MONEYVAL and executed most of its recommended actions (Cabinet of Ministers, Latvia’s latest technical report to MONEYVAL demonstrates measurable progress in enhancing national AML/CFT frameworks, 2019b). In 2018, the total amount of assets frozen by the FIU exceeded EUR 101 million, which is the highest result in the FIU’s history in terms of amount of funds frozen in a single year. This represents a 122% increase from 2017 to 2018. Later the activities of the FIU were continued. For instance, EUR 345,982 million were frozen in 2019 and during the first three months of 2020, potential criminal proceeds amounting to EUR 159.8 million – four times more than at the beginning of 2019 – were frozen by the FIU. A substantial strategy for reforming the financial sector was adopted as well as related regulation focused on strengthening the capacity of all authorities to combat money laundering. All authorities now have at their disposal the use of financial penalties, notably fines of up to EUR 1,000,000 for individuals and fines of up to 10% of total annual turnover or EUR 5,000,000 for legal persons. The FCMC has been conducting careful monitoring, including onsite checks of the effectiveness of implementation of these plans. Specific risk identification and profiling matrices are used by the authorities to identify the highest risks to the sector and refocus resources on the riskiest supervised entities. The FCMC staff has been increased and strengthened in order to ensure vigorous and risk-based compliance control of the financial sector under its supervision.

Latvia’s AML/CFT legislation has been harmonized with FATF standards, by significantly amending the AML/CFT Law to prohibit financial institutions from doing business with shell companies and to strengthen the operational independence and autonomy of the FIU, establishing it as the authority responsible for AML/CFT issues. As a result, since November 2017, Latvia has eliminated more than 17,600 shell companies. Risks in the credit sector have been significantly reduced. The FIU has reviewed the typologies and indicators of suspicious transactions. It has conducted a number of seminars and trainings with entities and supervisory authorities in order to support entities’ understanding of risk. The FIU has also developed guidelines and provided assistance through its website and by holding individual consultations with the reporting entities. This has already resulted in an increased quality of reports of suspicious transactions and an increase in the number of prosecutions and convictions. In 2018, the number of reports of suspicious transactions to the FIU totalled 6,617 and the FIU conducted financial intelligence analysis on 3,203 cases. In 470 cases, the FIU passed the information to Latvian law enforcement agencies or foreign FIUs (Cabinet of Ministers, Latvian Financial Sector Update No.17, 2019c). As the Finance Latvia Association has indicated, many improvements have been achieved, and the following can be mentioned as the main accomplishments: the risk landscape has significantly changed; risks, especially from CIS countries, still remain, but are noticeably mitigated; the level of awareness about the AML/CFT problem has significantly improved and so have regulations, the work of control institutions and information sharing procedures (Finance Latvia Association, 2019b).

On 17 December 2019, the Latvian government adopted a series of new measures to prevent money laundering, terrorism and proliferation financing for the period of 2020-22.

These measures were based on international, national, and sectoral risk assessments and results and learnings taken from the previous plan. The plan aimed to strengthen Latvia’s capacity to fight AML/CFT, reduce various risks in order to promote public security and improve trust in Latvia’s jurisdiction. The plan was divided into 11 actions, which align with the effectiveness indicators used by MONEYVAL during the fifth round of evaluation.

Compared to the grey-listed countries reviewed by the authors (see Table 3.1), Latvia had better results: its 6 Recommendations were rated as compliant and it also received 24 largely compliant, 10 partially compliant and no non-compliant evaluations. And taking into account improvements made by the Latvian authorities after MONEYVAL’s previous evaluation in 2018, the FATF, during its plenary session in Paris in February 2020, decided that following the successful implementation of a new financial crime prevention system, Latvia would not be subject to ‘enhanced surveillance’ or included in the so-called grey list. As reported, according to the assessment carried out by MONEYVAL, Latvia has improved its score for the implementation of 11 recommendations; thus, it has largely complied with the requirements of all 40 FATF recommendations, of which seven recommendations are fully compliant with the FATF international standard, while 33 are mostly met. Latvia became the first MONEYVAL member state to successfully implement all FATF recommendations.

When the authors started this research, it was not clear whether Latvia would be “grey-listed” or not. Now, since Latvia was not included in the grey list, we cannot analyse the impact of such inclusion but only observe the economic consequences caused by the negative MONEYVAL evaluation in the period from 23 August 2018, when Latvia became subject to enhanced monitoring, till the positive MONEYVAL evaluation in February 2020.

Impact of the Negative MONEYVAL Evaluation on Latvia

Despite the fact that Latvia achieved much better results in the MONEYVAL evaluation than the grey-listed countries, among Latvian officials there existed a certain anxiety in relation to the outcome of the upcoming FATF plenary session that was scheduled for February 2020. The president of the Bank of Latvia stated that the possibility that, despite efforts by Latvian banks to combat money laundering, the country would be included in the FATF’s grey list was “uncomfortably high” (Delfi TV, 2019). Also, the vice-president of the Bank of Latvia shared the opinion that being on the FATF’s grey list would mean serious risks to the Latvian economy: reduced investor interest and a decrease in both the national sovereign rating and financial institutions’ ratings, which in turn would mean more expensive money borrowing (Latvian Radio, 2018). The Head of the FCMC claimed that FDI would almost be stopped. She shared the opinion that inclusion in the grey list would have a huge impact on everything, both the economy and the state budget (TVnet, 2019). Similar opinions were widely promoted by the media.

All the experts interviewed in this research noted that it was absolutely impossible to predict how the inclusion of Latvia would affect its economy and there was a lot of speculation around this topic. All of them agreed that Latvia was a very unusual precedent, as thus far (except the recent appearance of Iceland in the list) no EU or western economies had been grey-listed. One expert stated that the implications would depend on the exact areas negatively evaluated, but primarily it of course would impact the reputation of the region, which would consequently impact everything that is sensitive to reputation: FDI, funding costs, credit ratings, etc. So, opinion differed and there was no clear understanding of how much and in what way the Latvian economy might be affected.

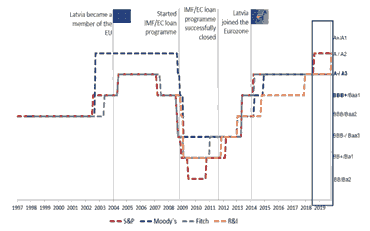

Contrary to the views expressed by the Latvian authorities, during the period when Latvia was subject to enhanced MONEYVAL monitoring, the financial market did not react negatively. No negative effect on Latvia’s sovereign credit rating was observed. It either stayed unchanged (Moody’s, Fitch) or actually improved (S&P, R&I) (see Figure 14).

Figure 14: Credit Rating History – Latvia (1997-2019) (Treasury Republic of Latvia, 2019b)

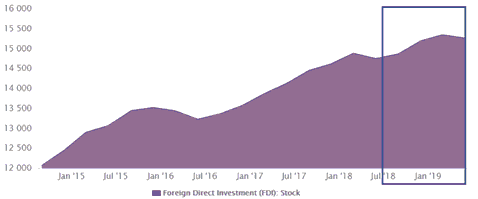

Foreign direct investment grew after the issue of MONEYVAL’s mutual evaluation report on 23 August 2018, with a slight decrease after January 2019. No negative effect on this indicator is observed (see Figure 15).

Figure 15: Foreign Direct Investment – Latvia, Million EUR (2015-2019) (Ceic, 2019c)

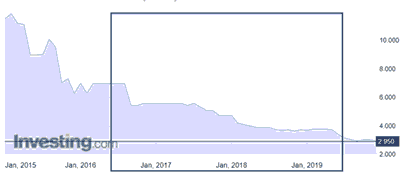

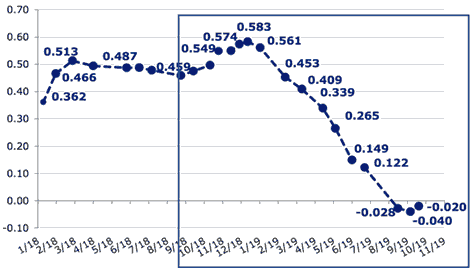

Latvia’s bond interest rates increased slightly in the months following the issue of MONEYVAL’s evaluation report and then experienced a steady decrease. So no negative effect is seen on this indicator either during the period when Latvia was subject to enhanced MONEYVAL monitoring (see Figure 16).

Figure 16: Government Bond Interest Rate – Latvia (2018-2019) (Treasury Republic of Latvia, 2019)

Of course, all these indicators (particularly interest rates) may also be affected by other factors in the financial market, but in general it can be concluded that there were no significant economic consequences for Latvia during the period of MONEYVAL’s enhanced monitoring after its negative MONEYVAL evaluation report.

The government’s activities to prevent money laundering must, of course, be welcomed. The implementation of a new financial crime prevention system was launched much earlier, when Latvia started the negotiation process for joining the OECD. A country risk assessment was performed, and attention was paid to the significant cash flow of non-residents serviced by Latvian banks. At the end of 2015, the OECD criticized the shortcomings in the Latvian AML/CFT system. As a result, a period of financial sector transformation began in 2016 (Financial and Capital Market Commission, 2019). For the first time in the history of the Latvian banking sector, in 2016, inspections of AML/CFT were performed in 12 Latvian non-resident banks by independent consulting companies from the USA invited by the regulator. Major changes were also made to the legislation governing AML/CFT. Later, the Latvian government’s measures to prevent money laundering and start the transformation of the financial sector were largely related to fears of a negative reaction from the financial market to Latvia’s inclusion in the MONEYVAL grey list. The transformation of the Latvian financial sector, which began in 2016, is still ongoing (as described above in Section 3.3.2) and is planned for completion by 2022.

However, positive activities aimed at AML prevention may have some negative consequences for the banking sector and the economy as a whole if they are exaggerated and disproportionate. The ambitious reform of the financial sector, aimed at improving the reputation of the Latvian banking sector and getting rid of so-called high-risk customers (mainly non-residents), stricter regulatory requirements in terms of AML/CFT and severe penalties for non-compliance primarily affected the banks. A great responsibility and a burden in the struggle with the AML/CFT problem has been put on banks that become closely scrutinized. In order to be compliant, they have greatly increased the amount of money invested in AML-related processes. As described earlier, it requires a lot of time, resources and expertise for governments and financial institutions to ensure compliance with the regulatory standards, as not being compliant poses huge risks for banks: legal and regulatory sanctions, significant financial losses or loss of reputation (Asenov, 2015).

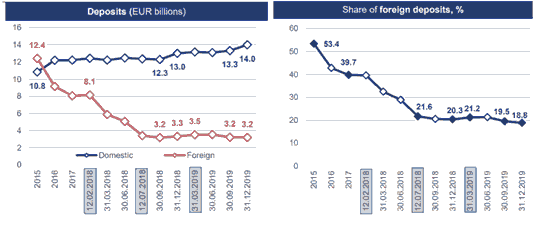

Implementation of a broad financial crime prevention system primarily affected the customer base and deposits. The share of foreign customer deposits decreased from 53.4% at the end of 2014 to 18.8% at the end of 2019 (see Figure 17). However, the state’s goal is to achieve a reduction to 5%-7% (Financial and Capital Market Commission, 2018).

Figure 17: Deposits and Share of Foreign Deposits in Latvia’s Banking Sector (2015-2019) (Fcmc, 2019)

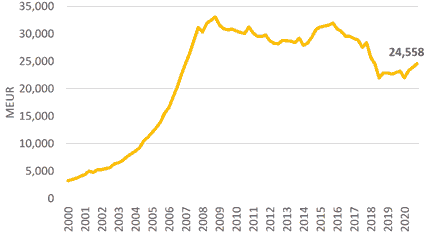

The total amount of deposits in this period decreased by 26%. Accordingly, total bank assets also decreased during this period (see Figure 18).

Figure 18: Total Assets of Latvia’s Banking Sector (2000-2020) (Finance Latvia Association, 2020)

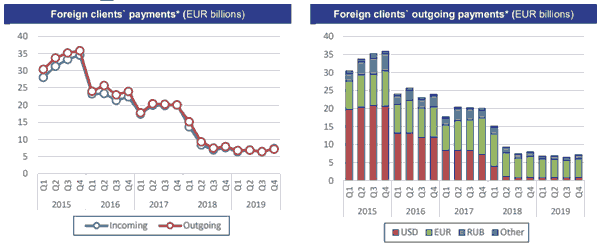

A significant decrease was observed in foreign customers’ payments as well. Foreign customers’ payments in US dollars contracted significantly, hitting the all-time low level observed. The euro became the prevailing currency.

This is also evidence of a remarkable turn in the Latvian banking sector’s business approach (see Figure 19).

Figure 19: Foreign Clients’ Payments in Latvia’s Banking Sector and its Currency Structure (2015-2019) (Finance Latvia Association, 2020)

As a result of all the changes during the period from 2016 to 2019, the total profit of the Latvian banking sector decreased from 454 million to 119 million, and ROE decreased from 14.25% to 3.14% (Finance Latvia Association, 2020). Banks (mostly non-resident banks) have to significantly transform their business models or otherwise leave the Latvian market or close their business.

A separate in-depth study would be needed to assess the impact of the AML measures adopted by the Latvian government on the financial sector and the national economy.

Discussion

Criminal activities that lead to money laundering negatively affect the global economy, having a major negative effect on society and especially on developing countries and emerging markets with weak and ineffective regulations in terms of AML and CFT.

The FATF’s Recommendations have become the global standard for effective national and international combating of money laundering and terrorist financing. The Recommendations set a minimum requirement for actions that should be taken by countries to fight financial crime, taking into consideration their local legal and constitutional frameworks (ACAMS, 2019; Alkaabi et al., 2010).

But some researchers, as we mentioned, argue that strengthening of enforcement within FATF is “likely to be counter-productive” (Nance, 2017b). There is no consensus among scholars when it comes to the impact strict regulations have on solving the AML problem. Some believe that tougher money laundering regulation has a positive effect on reducing it and the degree of related activities, while others suggest that extensive regulation can cause a decrease in investments, which in turn can foster the development of “shadow banking”, which may lead to instability. Currently the banking sector is not the only sector that requires attention, as after many governments globally implemented AML requirements for the banking sector, laundering activity has shifted to non-financial businesses and the non-bank financial sector (ACAMS, 2019). Compliance with AML requirements has become a substantial expense for many enterprises (Nance, 2017b). The problem that crystallized in the process of investigation is that currently in the AML area there is a lack of proper AML data, sufficient means to analyse it and suggestions on how to implement a proper risk-based approach to enforcement. These deficiencies make it difficult to estimate how AML controls and regulations have reduced the total amount of money laundered.

The second aspect is the impact on the national economy of a negative assessment of a country by international AML control institutions such as MONEYVAL. Some countries (e.g. Latvia) react very rapidly and firmly by taking very strict, perhaps even excessive, measures, fearing that inclusion in MONEYVAL's grey list may pose a high reputational risk and cause a fall in the country’s foreign direct investment and credit rating and thus a rise in government borrowing rates. Other countries (e.g. Iceland) also react to a negative MONEYVAL assessment and develop their AML prevention systems, but less sharply. And as a result, in some cases (e.g. Iceland), they are included in MONEYVAL’s grey list.

Generally, all Latvian experts interviewed in this research noted that Latvia made tremendous progress in order to implement MONEYVAL recommendations. Some even said that even more was done than expected. One of the interviewees remembered MONEYVAL experts admitting that it was some of the fastest progress ever made. One of the experts explained that once the MONEYVAL report was issued, mitigating factors went up significantly (we changed laws, introduced controls, changed the banks’ operating models) but many things worsened. Whether such excessive government activity is justified remains an open question.

It should be noted that MONEYVAL cannot impose penalties or sanctions on countries for non-compliance with FATF recommendations; the assessment is recommendatory. Therefore, it was important to find out whether a potentially negative assessment from MONEYVAL can also provoke a negative financial market reaction and thus motivate governments to react.

The results showed that for the 7 reviewed countries, inclusion in MONEYVAL’s grey list did not have an essentially negative impact on the three main indicators. The countries’ credit ratings did not decrease. A reduction in FDI was not observed and there was also no increase in government borrowing rates, which would have a further negative impact on the national economy.

The Latvian example showed that negative changes in these indicators were also not observed before inclusion in the grey list (during a period of subsequent strict MONEYVAL monitoring). However, the analysis of the time period before inclusion in the FATF’s grey list showed that in some reviewed countries (Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Albania, Azerbaijan, Iceland) FDI decreased to some extent. In Latvia, FDI was growing during the period of enhanced MONEYVAL monitoring. In Kyrgyzstan, FDI reached its peak a year before inclusion. In Tajikistan a sharply rising trend was observed around 1.5 years before inclusion in the grey list.

Therefore, a clear conclusion that the market reacts or does not react shortly before inclusion in the grey list cannot be made, as the results are not consistent for all countries. It is possible that there is some influence from other factors on the indicators studied here.

The rapid response of the Latvian government and the active streamlining of AML procedures in line with the FATF’s recommendations ensured that the country was not included in the grey list. It can be considered positive that after a negative MONEYVAL assessment, Latvia made tremendous progress in implementing all FATF recommendations. But on the other hand, such marked banking and financial turmoil had a number of negative consequences: the structure of bank customers changed significantly; banks were forced to reconsider their business models; and the amount of deposits, bank assets and capital decreased sharply. Customer payments also decreased significantly, especially in USD, and as a result, bank profits and ROE fell. In addition, banks experienced significant financial losses in the form of fines and penalties, and also through the plunging of their share prices as society reacted to the AML scandals.

Therefore, it is necessary to assess whether the positive effects of improving surveillance systems and restrictions of money laundering entail negative consequences from over-focusing solely on the struggle against money laundering.

References

ACAMS. (2019). Study guide: CAMS certification exam.

Alkaabi, A. (2010). Money laundering and FATF compliance by the international community.

Anderson, M., & Anderson, T. (2015). Anti-money laundering: History and current developments.

Asenov, E. (2015). Characteristics of compliance risk in banking.Economic Alternatives, 27(3).

Cabinet of Ministers. (2018a). The money Val report confirms the direction of the government's chosen course of reform.

Cabinet of Ministers. (2018b). The financial sector development council has conceptually endorsed an action plan to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.

Cabinet of Minister. (2019a). Latvia’s latest technical report to MONEYVAL demonstrates measurable progress in enhancing national AML/CFT frameworks.

Cabinet of Ministers. (2019b). Latvian financial sector update no.17.

Cabinet of Ministers. (2020). Latvian financial sector update.

CEIC. (2019a). Serbia foreign direct investment: Flow.

CEIC. (2019b). Latvia's foreign direct investment.

CEIC. (2019c). Azerbaijan treasury bill rate.

CEIC. (2019d). Albania treasury bill rate.

CEIC. (2019e). Bosnia and Herzegovina real interest rate.

CEIC. (2021). Iceland foreign direct investment.

Council of Europe. (2008). Mutual evaluation report–Executive summary. Azerbaijan.

Council of Europe. (2011). Report on fourth assessment visit–Executive summary. Albania.

Council of Europe. (2017). MONEYVAL 2017 annual report.

Council of Europe. (2019a). Committee of experts on the evaluation of anti-money laundering measures and the financing of terrorism.

Council of Europe. (2019b). MONEYVAL in brief.

Council of Europe. (2019c). Statutory documents.

countryeconomy.com. (2019). Rating: Albania credit rating.

Delfi TV with Janis Domburs-answers Martinš Kazaks. (2019). TV broadcast Delfi TV.

European Comission. (2014). Albania 2014 progress report.

FATF. (2019a). Committee of experts on the evaluation of anti-money laundering measures (MONEYVAL).

FATF. (2019b). What is money laundering?

FATF. (2021). Jurisdictions under increased monitoring.

FCMC. (2018). European parliament committee TAX3 evaluates managing the changes in Latvian banking sector.

FCMC. (2019a). Change management in the Latvian Financial Sector 2016-2019: Review of key events and statistics.

FCMC. (2019b). Info graphics: Transformation of Latvian banking sector, Q4 2019.

Finance Latvia Association. (2019). Operating results of Latvian commercial banks.

Finance Latvia Association. (2020). Operating results of Latvian commercial banks.

FIU of Latvia. (2019a). Annual report 2018.

FIU of Latvia. (2019b). Moneyval publishes a report on Latvia.

FX Empire. (2019). Azerbaijan credit ratings.

Hopton, D. (2009). Money laundering a concise guide for all business, (2nd Edition). New York: Routledge.

International Center for Asset Recovery. (2018). Basel AML index 2018 report.

Investing.com. (2019). Serbia 5-year bond yield overview.

Investing.com. (2021). Iceland 10-year bond yield.

Latvian Radio. (2018). Latvijas Banka: Being on the gray list can have a significant impact on economic growth.

MONEYVAL. (2018). Latvia: Fifth round mutual evaluation report.

MONEYVAL. (2019). Latvia: 1st enhanced follow-up report.

Nance, M.T. (2017a). Re-thinking FATF: An experimentalist interpretation of the financial action task force.

Nance, M.T. (2017b). The regime that FATF built: An introduction to the financial action task force.

The Central Banks of Bosnia-Herzcegovina. (2019). BH sovereign credit rating history.

The National Bank of Serbia. (2019). Republic of Serbia’s long-term credit rating.

The Central Bank of Iceland. (2021). The republic of Iceland's sovereign credit rating.

Treasury Republic of Latvia. (2019a). Treasury of the republic of Latvia.

Treasury Republic of Latvia. (2019b). Development of Latvia`s credit rating.

TV net. (2019). Everything can collapse like a house of cards, or how Latvia's inclusion in the "gray list" of Moneyval will affect the population.

Unger, B., & Ferwerda, J. (2008). Regulating money laundering and tax havens: The role of blacklisting.

United Nations. (2013). World investment report 2013.

United Nations. (2014). World investment report 2014: Investing in the SDGs: An action plan.

World Bank. (2019a). Foreign direct investment, net inflows-Tajikistan.

World Bank. (2019b). Foreign direct investment, net inflow-Albania.

World Bank. (2019c). Foreign direct investment, net inflows-Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Received: 14-Nov-2021, Manuscript No. IJE-21-8782; Editor assigned: 16-Nov-2021, PreQC No. IJE-21-8782(PQ); Reviewed: 07-Dec-2021, QC No. IJE-21-8782; Revised: 27-Dec-2022, Manuscript No. IJE-21-8782(R); Published: 03-Jan-2022