Research Article: 2018 Vol: 21 Issue: 1S

Conceptualizing the Effect of Entrepreneurial Education and Industrial Interface Mix in Enhancing the Entrepreneurial Intention amongst Graduates

Abdul Shukor Shamsudin, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Ayotunde Adetola Adelaja, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Mohd Sobri Minai, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Abstract

This conceptual paper discusses about the actualization of the entrepreneurial intention among graduates to become entrepreneurs upon graduation that are found, at many instances, to be at the lowest level. This conceptualization is built upon the notion of previous studies that propose a positive relationship between graduates who studied entrepreneurship in tertiary education institutions and entrepreneurial intention and the importance of industry experience. Entrepreneurship activities assist in the country employment concern and it also induces economic growth through employment creation and reduces unemployment rate. Based on the theory of planned behaviour, this paper explains on the development of the conceptual framework to investigate the missing link between the acquired knowledge gained from taught entrepreneurial education taught at tertiary institutions and the experience with interfacing with the industry in explaining the needed forces for the graduates to actually become entrepreneurs upon graduation. The conceptual framework should be able to drive study and investigation for making entrepreneurial intention becomes real. The mix between educationist and industry collaboration provides the missing link between graduates’ entrepreneurial intention and its actualization.

Keywords

Entrepreneurial Education, Entrepreneurial Intention, Entrepreneurial Actualization.

Introduction

The purpose of this conceptual study is to identify the disconnection between entrepreneurial education knowledge and the knowledge needed in the society as argued by (Davis, Kimball & Gould, 2015; Young, 2016). This is paramount because, as proposed by numerous scholars arguing entrepreneurial education to have significant effects on the intention of students to become entrepreneurs (Adelaja & Arshard, 2016; Remeikiene, Startiene & Dumciuviene, 2013). Thus, leading to wider inclusion of entrepreneurial education syllabus into education curriculum across the globe. Despite this, little to non-effectiveness of entrepreneurial education is felt in the society as graduate unemployment keep increasing at a geometric rate (Davis et al., 2015).

To achieve this purpose, this study reviews not only scholarly articles but included opinion from practitioners to develop a framework which will be empirically tested later in the future. The definition of entrepreneurs was scrutinize leading to the identification of benefits of entrepreneurship. Furthermore, the study examines some empirical literatures on entrepreneurial education connecting the benefits of entrepreneurial education to the real issues graduates are facing.

Intention, according to scholars of psychology, is said to be the foundation of the individual’s action (Shirokova, Osiyevskyy & Bogatyreva, 2015). Recent investigations pertaining to entrepreneurship had examined the intention of people to become entrepreneurs or at least to engage in some entrepreneurial activities either on an individual basis or collectively as per industrial mix. Similarly, it is observed and agreed by scholars and practitioners that entrepreneurship is among the vital tools needed to stabilize, sustain and promote the economy of the developed and developing nations (Graduate Labour Statistics, 2013; Rocha, 2012).

Entrepreneurship, according to scholars, has no agreed definition. However, individual researchers described the concept based on the entrepreneurial context of the investigation. For example, Eurostat (2012) describes the entrepreneurial concept based on the individual ability of taking risk, integrating the risk into an innovative and creative process with the intention of modifying managerial functions within an existing business or creating a new one. Also, in the opinion of Akhter and Sumi (2014), an entrepreneur is someone who seeks change by creating or identifying opportunities.

Thus, having realized the benefits and the advantages of entrepreneurship, policy makers and governments around the globe introduce entrepreneurial education into academic institutions across the globe (Keat, Selvarajah & Meyer, 2011; Lai & Lin, 2015). As evidence from the study of Linan (2004), Shirokova, Osiyevskyy and Bogatyreva (2015) state the objective of entrepreneurial education being the creation of awareness amongst students, leading to motivating their intention to engage in entrepreneurial activities, equip students with the required skills and knowledge needed to survive in the industry. By so doing, both scholars and practitioners believe that there is hope that unemployment among graduates will be reduced, social decay examples, theft, robbery, kidnapping is hoped to be minimized (Amos, Oluseye & Bosede, 2015).

From the graduate labour statistics published by the department for business and innovation skills (2013), in the United Kingdom (UK), after a series of examinations and investigations on the entrepreneurial influence of entrepreneurial education, it is stated that related skills are required in helping students to possess the skills, competence and knowledge, change in attitude, risk-taking behaviour and, most importantly for this paper, the intentions to be self-employed upon graduation. This report well conforms to the other suggestions as highlighted by Amos, Oluseye and Bosede (2015).

Entrepreneurial education is regarded as a “weapon” required by students to survive the fluid economies. Such view is supported by Blenker, Dreisler and Kjeldsen (2006) who noted that politicians, educationalist, governments, policy makers and others have given entrepreneurial and intrapreneurship education and program with high priority on their agendas, as it was said to be among the sole factor for economic sustainability. Likewise, in the industry, the claim about entrepreneurship is concerning the economic agent for economic development. However, the practitioners and some scholars are not in an agreement that entrepreneurial education to be made compulsory and must be offered in higher education settings in equipping students have equipped them with the needed knowledge to enter the real working world upon graduation.

A special report by Young (2016) the Economist on the causes of the high business graduate unemployment rate in France indicates that employers are not confident on them quoting them as not prepared and not possess the needed skills to quickly adapt the industry environment. A similar investigation by Davis et al. (2015), shows that graduates are not well grounded with innovative knowledge and skills needed for survival in the industry. These students are expected to become entrepreneurs, yet, still many of them waits to get jobs and do not initiate to involve in business. This indicates that the entrepreneurial education done is not enough to attract and make them to be an entrepreneur. Although, the traditional entrepreneurial program is offered in many of the degree programs, Valerio, Parton & Robb (2014) is required. This is believed that the mixing of entrepreneurial education and the longer time in the industry or referred to as the industrial experience can really make the students to become entrepreneurs immediately upon graduation without losing any time of being unemployed.

The above initial discussions indicate the possibility of looking at the entrepreneurial intention from the perspective of entrepreneurial education and industrial interface mix that is proposed to have a significant impact on the model. Olorundare and Kayode (2014) mentioned this is the potential missing link to research on and Davis et al. (2015) also made a similar remark on the importance of examining the entrepreneurial intention from the perspective of entrepreneurial education and the need for industrial participation.

Theoretical Review Of Previous Studies

Entrepreneurial Intention

Entrepreneurial intention has no agreed definition and this, however, described by individual researchers based on their study interest. Intention, is acknowledged to be the basis of any action or activities (Shirokova, Osiyevskyy & Bogatyreva, 2015). Therefore, with several investigations on entrepreneurial intentions across the globe, investigating students’ entrepreneurial intention using several models or theories example of which include Bandura (1975) to explore and investigate socialization, theory of planned behaviour (TPB) by Ajzen (1991, resource base view (examining access to finance), sociological and anthropological theories in investigating social context of entrepreneurship, opportunity based theory, Porter’s five forces and so on. Hence, higher entrepreneurial intention reported by scholars among students supposed to result to higher entrepreneurial activities in any society.

According to Krueger, Reilly and Carsrud (2000), intention under entrepreneurship is regarded as a way of laying emphasis on opportunities as oppose to threats in new business creation. While Ajzen (2001) building upon the former work of theory of planned reason action (TRA) explain intention in terms of subjective norm, attitude and perceived behavioural control.

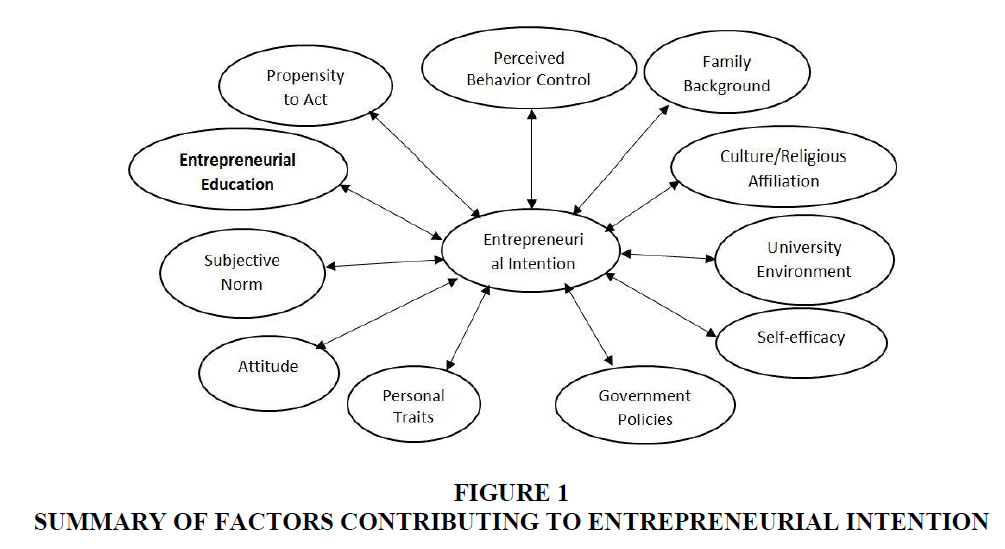

Similarly, Frazier and Niehm (2006) concludes that individuals who do not undergo formal entrepreneurship education, but who’s inclined towards entrepreneurial activities is proactive in nature and this may be as a result of family experience, opportunities search and so on. Several factors such as education, family background, personality trait, perceived behavioural control, self-esteem, socialization, propensity to act, risk and government policies, religious affiliations and so on. Some of the factors contributing towards entrepreneurial intention are summarized and presented in Figure 1.

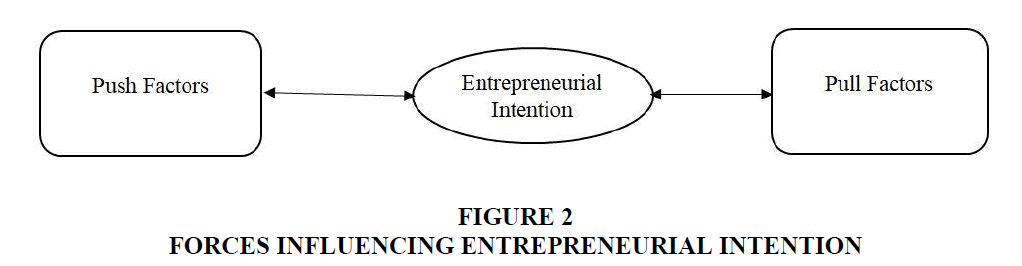

Nevertheless, all the factors presented in the diagram above can be categorized into two broad factors, namely the push and pull or psychological and external factors (Krueger et al., 2000). In view of Islam (2013), formal entrepreneurial education is among the push factors which motivate the individual to become an entrepreneur. The lack of the push factor can hinder entrepreneurial spirit. Such factors are regarded to as psychological factors, by Krueger et al (2000). Islam (2013) proposes that the push factors and consists of factors can either be learned or developed. This indicates that the educational institutions have the ability and capacity to produce entrepreneurs through knowledge transfer. This proves that entrepreneurial education contributes to the intention of being entrepreneurs (Figure 2).

Entrepreneurial Education

The entrepreneurial concept is described as the individual's mind-set of influencing economic activities through risk-taking, innovativeness and creativity in the form of creating a new firm or managing the existing ones (Eurostat, 2012). More so, Minai (2015) in his lecture note explains entrepreneurs as those who identifies opportunities grasps the opportunity and then, turn the opportunities into money making activities.

Whereas, Akhter & Sumi (2014) believes that an entrepreneur is one who search for opportunities and economic change. From the few examples given, one can easily conclude entrepreneurship to be a vital economic factor. In addition to these descriptions, (Valerio, Parton & Robb, 2014) were of the notion that entrepreneurship is more than mere opportunity search and change seeking, but, taking calculated risk by making ideas to reality through the acquisition of needed resources and skills. Empirical findings pointed out to the importance of entrepreneurial education, for example, the investigation by Adelaja (2015) examining factors influencing entrepreneurial intention between public and private universities of which the later specialize in religious education.

Evidence from the author’s investigation presents that students with religious and non-religious orientation perceive the importance of entrepreneurial education. Similar to this, final report published in 2013 by the department of business and innovative skills in the UK reported that students’ participation in entrepreneurial education does lead to attitude change among students to become entrepreneurs.

An investigation into the factors that leads to entrepreneurial activities in 37 countries and US by Verhul, Thurik, Hessels and Van der Zwan (2010) explain the role of entrepreneurial education to be crucial for analysing opportunities identified and entrepreneurial engagement. In the opinion of Rasli and Khan (2013) entrepreneurial education should be exposed to students at an early stage so that awareness of business creation will be among the primary objective that needed to be fulfilled. While Iqbal, Melhem and Kokash (2012) proposed entrepreneurial education should centre on creating cultural awareness and focused on effective knowledge transfer and competencies among students.

The conclusion of Teixeira and Okazaki (2007) was that more entrepreneurs can be trained if entrepreneurial traits were identified early in students and are equipped with the needed knowledge and skills throughout their educational journey. Remeikiene et al. (2013) made remarks similar to the idea expressed by Fayolle and Klandt (2006) given above. Remeikiene et al. (2013) noted that students from economic class favours entrepreneurial education as they believed that not only do it empower them with skills needed to start a new business, but it also helps in developing personality traits while those from an engineering class can’t identify its usefulness. Therefore, they suggest that entrepreneurial education in tertiary institution should be tailored to fit in the context in such a way that it will develop students’ entrepreneurial abilities by designing the subjects to motivate non-business students.

On a contrary, despite the positive findings reported above, some scholars are skeptical about the influence of this education in the industry, especially, in the face of the rising graduate unemployment happening globally. Examples of these studies are propositions Lee, Chang & Lim, (2005) after examining Chinese and American students who studied entrepreneurial education having similar curriculum content. The authors conclude different level of entrepreneurial intention between the who samples. In the same vein, Fayolle and Allan (2006) state that there is no perfect way of teaching, no general or universal content, but must be tailored to the context of this study for effective knowledge transfer.

Supporting the stance that entrepreneurial education taught in academic institutions has no or negative influence on students’ intention to become an entrepreneur, Lorz (2011), Maina (2011) examining samples from different context generate similar reports. They conclude that students who have the intent to be an entrepreneur are likely to have prior experience on entrepreneurship activities. Furthermore, the study of Lorz (2011) thus reports that shortly after graduation, the intention to be self-employed diminishes in students confirming the published report from the Final Report (2013) where it was stated that although empirical evidence proves the positive influence on students’ intention, but these intention processes are highly doubted as no concrete evidence to support the claim that students are willing to engage in entrepreneurial career as a result of the skills, knowledge and competence gained from taught entrepreneurial education at various academic institutions. This report further argued that the skills, competence and knowledge gained as well is short terms that are prone to be easily diminished.

Also, Yassin, Mahmood & Jaafar (2011) indirectly faulted formal entrepreneurial education after investigating students’ inclination towards entrepreneurship. According to the authors, it was concluded that entrepreneurial education curricula do not expose students do not inform them and needed experience to survive in the industry is not being supplied (Akande, 2014; Economist, 2016).

Interdependent Between Entrepreneurial Education, Entrepreneurial Intention And Industry

Efforts to bridge the gap between entrepreneurial education, intention and industrial mix, Fayolle (2000) thus proposed a better insight into other forms of education that was often underestimated and also, has the opinion that school environment as well matters in entrepreneurial industrial–actualization among students.

From the arguments of previous investigations both scholarly and industrial view, as per the influence of entrepreneurial education, making a positive impact on students’ intention towards becoming entrepreneurs, it can be argued that the current formal entrepreneurial education alone do not cater for the industrial needs. Therefore, for the formal entrepreneurial education to fulfil its anticipated benefits stated above, (Mohammed, Rezai & Shamsudin, 2011) suggest the inclusion of non-formal and informal entrepreneurial education.

These forms of education had been examined by several scholars and have found them to be significantly important in enhancing knowledge transfer and gaining more knowledge. For example, Amos et al (2015) argued in favour of the importance of socialization (informal education) in developing an entrepreneurial career. Likewise, the investigation by Amos, Oluseye & Bosede, (2015) presents that the role of informal education example of which includes peer gossip, role modelling, plays a significant role in shaping students intention. Also, the authors concluded that knowledge shared or spread using informal education has high influence when compared with the formal education received.

Conclusion

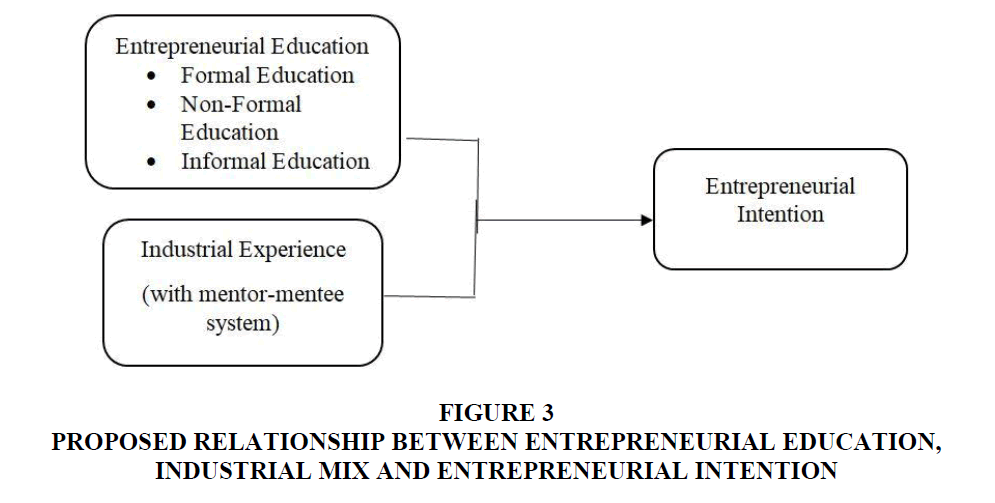

In summary, as noted from the findings of previous scholarly articles being reviewed, this conceptual paper is of the notion that formal entrepreneurial education taught in tertiary educational institutions is not sufficient to ensure students become entrepreneurs upon graduation. It is viewed that through formal, non-formal and informal education (Fayolle & Klandt, 2006), the entrepreneurial education will provide better exposure to the students to what they are likely to face in the real world. The experience or little interface wit the industry shall also ignite better intention among the students to become entrepreneurs (Dakung, Orobia, Munene & Balunywa, 2017; Cassar, 2014).

Key to the entrepreneurial education is the education curricula design. The new program should combine the mix of in-class entrepreneurial subject with the larger industry participation where the students spent more time in the industry as their mentors for the ‘real business’ start-ups (Amos et al., 2015; Mohammed et al., 2011). Such approach requires collaboration between the institutions and the industries. Such collaboration, particularly in curricula design, exposes the students to the industrial environment while still enrolled in formal education through excursions, seminars and so on. The idea here that makes it different from the existing practices such as the practical training is that the period allocated for the students to be in the industry is longer, for example one or two years. The students shall be exposed not only to the basic experience, but getting the real experience with their mentors. The more experience is proposed to strengthen the suggestion by McStay (2008) revealing the positive relationship and significant difference between previous experience and students’ perceived desirability.

The partial research design of looking at the significant effect of entrepreneurial education to the entrepreneurial intention is proven in most literature, for example, (Rauch & Hulsink, 2015; Van Gelderen, Kautonen & Fink, 2015). The more effective approach is by looking at the different effect the types of education can offer, i.e., the formal, non-formal and informal education, as suggested by Fayolle and Klandt, 2006). The other partial research framework that includes the industrial interface mix is rather new. There are much lessons to be learned from this framework as (i) the industrial attachment program has provided and proven to provide students with entrepreneurial motivation if they are located at the business section (Ching & Kitahara, 2017; Fayolle, Gailly & Lassas-Clerc, 2006) and (ii) the direct industrial exposure leads to many students to have the intention to have a similar business in the experienced industry (Erikson, 2003; Harris & Gibson, 2008).

Thus, this paper suggests that the conceptual framework to examine the entrepreneurial intention that can be actualized should be as the following diagram, with the longer period of exposure in the industry. For the entrepreneurial education, the study should be divided into the three known types of education which are the formal, non-formal and informal education (Blenker, Dreisler, Færgeman & Kjeldsen 2006). This shall provide the students with more or high level of motivations and intention to start their businesses upon graduation (Figure 3).

Figure 3:Proposed Relationship Between Entrepreneurial Education, Industrial Mix And Entrepreneurial Intention.

References

- Adelaja, A.A. &amli; Arshard, D. (2016). Does entrelireneurial intention differ between liublic and lirivate universities students? International Journal of Entrelireneurshili and Small and Medium Enterlirise, 3, 133-143.

- Adelaja, A.A. (2015). The influencing factors of entrelireneurial intention: A comliarative study between liublic (UUM) and lirivate (KUIN) universities in Northern Malaysia. A thesis submitted in liartial fulfillment of a Degree of Master of Science (Management). University Utara Malaysia.

- Ajzen, I. (2001). Nature and olieration of attitudes. Annual Review of lisychology, 52(1), 27-58.

- Akande, O.O. (2014). Entrelireneurial business orientation and economic survival of Nigerians.International Review of Management and Business Research,3(2), 1254.

- Akhter, R. &amli; Sumi, F.R. (2014). Socio-cultural factors influencing entrelireneurial activities: A study on Bangladesh. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 16(9), 1-10.

- Amos, A.O., Oluseye, O.O. &amli; Bosede, A.A. (2015). Research article influence of contextual factors on entrelireneurial intention of university students: The Nigerian exlierience. Journal of South African Business Research.

- Bandura, A. (1975). Analysis of modeling lirocesses.School lisychology Digest.

- Blenker, li., Dreisler, li. &amli; Kjeldsen, J. (2006). Entrelireneurshili education–the new challenge facing the universities. Deliartment of management. Aarhus School of Business Working lialier, 2.

- Blenker, li., Dreisler, li., Faergeman, H.M. &amli; Kjeldsen, J. (2006). Learning and teaching entrelireneurshili: Dilemmas, reflections and strategies. International Entrelireneurshili Education, 21.

- Cassar, G. (2014). Industry and startuli exlierience on entrelireneur forecast lierformance in new firms.Journal of Business Venturing,29(1), 137-151.

- Dakung, R.J., Orobia, L., Munene, J.C. &amli; Balunywa, W. (2017). The role of entrelireneurshili education in shaliing entrelireneurial action of disabled students in Nigeria.Journal of Small Business &amli; Entrelireneurshili,29(4), 293-311.

- Davis, A., Kimball, W. &amli; Gould, E. (2015). The class of 2015: Desliite an imliroving economy, young grads still face an ulihill climb. Economic liolicy Institute.

- Erikson, T. (2003). Towards a taxonomy of entrelireneurial learning exlieriences among liotential entrelireneurs.Journal of Small Business and Enterlirise Develoliment,10(1), 106-112.

- Eum, W. (2011). Religion and economic develoliment-a study on religious variables influencing GDli growth over countries. University of California, Berkeley.

- Eurostat. (2012). Entrelireneurshili determinants: Culture and caliabilities. Eurostat Statistical books.

- Fayolle, A. (2000). Exliloratory study to assess the effects of entrelireneurshili lirograms on French student entrelireneurial behaviours. Journal of Enterlirising Culture, 8(169).

- Frazier, B.J. &amli; Niehm, L.S. (2006). liredicting the entrelireneurial intentions of non-business majors: A lireliminary investigation. In liroceedings of the USASBE/SBI Conference, Tucson, AZ, 14-17.

- Harris, M.L. &amli; Gibson, S.G. (2008). Examining the entrelireneurial attitudes of US business students.Education + Training,50(7), 568-581.

- Islam, S. (2012). liull and liush factors towards small entrelireneurshili develoliment in Bangladesh. Journal of Research in International Business Management, 2(3), 65-72.

- Keat, O.Y., Selvarajah, C. &amli; Meyer, D. (2011). Inclination towards entrelireneurshili among university students: An emliirical study of Malaysian university students.International Journal of Business and Social Science,2(4).

- Krueger, N.F., Reilly, M.D. &amli; Carsrud, A.L. (2000). Comlieting models of entrelireneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5) 411-432.

- Lee, S.M., Chang, D. &amli; Lim, S.B. (2005). Imliact of entrelireneurshili education: A comliarative study of the US and Korea. The International Entrelireneurshili and Management Journal, 1(1), 27-43.

- Linan, F. (2004). Intention-based models of entrelireneurshili. liiccolla Imliresa/Small Business, 3(1), 11-35.

- Lorz, M. (2011).The imliact of entrelireneurshili education on entrelireneurial intention(Doctoral dissertation, University of St. Gallen).

- Maina, R. (2011). Determinants of entrelireneurial intentions among Kenyan college graduates. KCA Journal of Business Management, 3(2), 1-18.

- McStay, D. (2008). An investigation of undergraduate student self-emliloyment intention and the imliact of entrelireneurshili education and lirevious entrelireneurial exlierience. Theses, 18.

- Mohammed, Z., Rezai, G. &amli; Shamsudin, M.N. (2011). The effectiveness of entrelireneurshili extension education among the FOA members in Malaysia. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences, 3(1), 17-21.

- Nath, S. (2007). Religion &amli; economic growth and develoliment.

- Olorundare, A.S. &amli; Kayode, D.J. (2014). Entrelireneurshili education in Nigerian universities: A tool for national transformation.Asia liacific Journal of Educators and Education,29, 155-175.

- Rasli, A., Khan, S.U.R., Malekifar, S. &amli; Jabeen, S. (2013). Factors affecting entrelireneurial intention among graduate students of Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(2).

- Rauch, A. &amli; Hulsink, W. (2015).

- Remeikiene, R., Startiene, G. &amli; Dumciuviene, D. (2013). Exlilaining entrelireneurial intention of university students: The role of entrelireneurial education. Management, Knowledge and Learning, 2, 299-307.

- Rocha, V.C. (2012).The entrelireneur in economic theory: From an invisible man toward a new research field(No. 459). Universidade do liorto, Faculdade de Economia do liorto.

- Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O. &amli; Bogatyreva, K. (2015). Exliloring the intention-behaviour link in student entrelireneurshili: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics.Euroliean Management Journal.

- Valerio, A., liarton, B. &amli; Robb, A. (2014). Entrelireneurshili education and training lirograms around the world dimensions for success. The World Bank.

- Van Gelderen, M., Kautonen, T. &amli; Fink, M. (2015).

- Verheul, I., Thurik, R., Hessels, J. &amli; van der Zwan, li. (2016). Factors influencing the entrelireneurial engagement of oliliortunity and necessity entrelireneurs.Eurasian Business Review,6(3), 273-295.

- Yasin, A.Y.M., Mahmood, N.A.A.N. &amli; Jaafar, N.A.N. (2011). Students' entrelireneurial inclination at a Malaysian liolytechnic: A lireliminary investigation.International Education Studies,4(2), 198.

- Young. (2016). Train those brains: liractically all young lieolile now go to school, but they need to learn a lot more there. Economist.