Review Article: 2022 Vol: 26 Issue: 4S

Conceptualizing the Consumer Legitimacy for Sharing Practices through the Prizm of Personal Values

Gautam Agrawal, BML Munjal University

Ruchi Garg, BML Munjal University

Ritu Chhikara, BML Munjal University

Vishal Talwar, IMT Ghaziabad

Citation Information: Agarwal, G., Garg, R., Chikkara, R., & Talwar, V. (2022). Conceptualizing the consumer legitimacy for sharing practices through the Prizm of personal values. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 26(S4),1-10.

Abstract

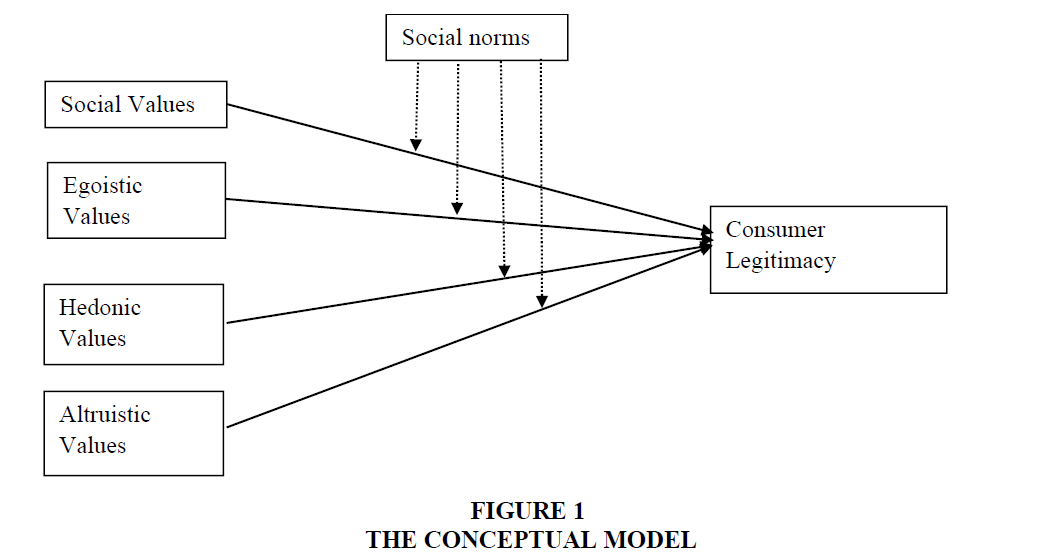

The exponential growth of disruptive socio-economic sharing economy practices has brought into focus the i) different forms of sharing practices ii) mass adoption of the sharing practices business models. In the present age of consumerism and consumer concerns for ethical, eco-sustainable consumption, developing an understanding of the reasons behind consumers granting legitimacy or acceptance, to certain business models and/or organizations is a relevant field of study for academicians and practitioners. The present work seeks to answer the questions about the legitimacy-granting behavior in sharing practices context through the prism of personal values of the participants. The study focuses on the impact of hedonic values, social values, egoistic values and altruistic values on the consumers acceptance of different sharing practice models. Further, the study posits mediating role of the social norms in the legitimacy-granting behaviour by the consumers. The study is a conceptual framework that attempts to extend the present literature in the sharing economy domain. The study postulates an individual’s legitimacy judgment as a behaviour. It is influenced by their personal values and mediated by the social norms. Our context is the legitimacy of the sharing practices irrespective of the industry. The paper develops a conceptual framework that identifies the three categories of legitimacy that the consumers may grant to sharing practices based on their value systems. The generic framework can be empirically tested in tourism and hospitality-related settings, including but not limited to accommodation, transportation, community-based tourism.

Keywords

Conceptual Framework, Values, Sharing Economy Practices, Consumer-Legitimacy.

Introduction

The sharing economy is an emerging business model that seeks to reallocate underutilized resources across the populace to expand their usefulness (Howard, 2015). Sharing economy stages permit clients to impart their assets to other people, consequently growing new examples of utilization (Dolnicar, 2021).

Two of the most unmistakable and broadly referred to instances of the sharing economy are Uber (ride sharing) and Airbnb (convenience sharing) (Geissinger, Laurell, and Sandström, 2020). Numerous other plans of action have arisen that attention on sharing as opposed to selling merchandise (Belk, 2014). This relates to a change in perspective by millennial consumers wherein the capacity to utilize, and not possession, turns into their central interest (Bardhi and Eckhardt, 2012).

Investigations of the sharing economy have developed fundamentally over the long haul, particularly throughout recent years (Hossain, 2020; Phung et al., 2021). The development of the sharing economy has produced significant conversation in both public and insightful talk. Some believe the sharing economy to be a promising an open door for people to track down transitory business, create additional pay or upgrade social communications or as a methodology towards more manageable utilization (Hamari, Sjöklint, and Ukkonen, 2015). Others question the cooperative, supportable and social outlining of the sharing economy, highlighting genuine or possible maltreatment of laborers by sharing economy organizations (Calo and Rosenblat, 2017)

Sharing economy practices have been named problematic due to their lack of legacy and as an emerging socio-economic model (Geissinger et al., 2020). They have brought changes to the current institutional and authoritative designs across businesses. While there is a huge agreement in both academics and sharing organizations that customers are pivotal partners in bringing the institutional change, how consumers accept and adopt these new business paradigms remains unknown.

The research adds to the academic literature in the accompanying ways. Initially, we integrate VBN theory with Institutional theory to understand the consumers expectation to acknowledge sharing economy practices. Besides, we give a theoretical system which can be experimentally tried in different ventures practicing the sharing economy elements. The different ventures range from shared accommodations, the travel industry, mobility to design, labor supply and money.

Literature Review

Sharing Economy Practices

The term sharing economy practices comes up short on universally acceptable definition (Cheng, 2016; Muñoz and Cohen, 2017; Parente et al., 2018; Netter et al., 2019; Ahsan 2020) consequently enveloping a wide scope of ideas (Hawlitschek et al., 2018). As of late, many terms and ideas have been conceptualized including but not limited to those examined here. These terms like ''Collaborative consumption'' (Botsman and Rogers, 2011) ''sharing'' or ''sharing economy'' (Belk,2014), ''access'' or ''access-based utilization'' or "on - request economy" (Bardhi and Eckhardt, 2012), ''asset sharing framework'' (Lamberton and Rose, 2012), "gig economy" (Friedman, 2014), "digital distributed economy" (Kostakis and Bauwens, 2014) etc. Hence, researchers depict the sharing economy as an umbrella term (Habibi et al., 2017) covering an assortment of ways of behaving and plans of action that can't be reduced to one explicit definition (Herbert et al., 2017; Schor et al., 2016). Belk (2014) referencing organizations like Airbnb, Zipcar, and Freecycle, groups these and other "related business and utilization practices" under the umbrella term "the sharing economy". The scholarly field, and therefore, the strategy creators, professionals are as yet bantering about what really establishes the sharing economy, or on the other hand if, as a matter of fact, it ought to try and be alluded to thusly or all things considered, the cooperative economy (Chase, 2015).

The researchers, subsequently, rather than adding another definition have conceptualized the cooperative utilization as an umbrella develop. Appropriately, sharing economy can't be organized as Peer-to-Peer, computerized or impermanent access-based under-used asset sharing plans. Further, it indicates customers' role play of being prosumer i.e., being supplier and user within a specific asset sharing plan (Mohlmann, 2015).

Legitimacy

Bitektine (2011) and Tost (2011) supported that specialist focus better on how people judge legitimacy. People are significant on the grounds that on the whole they impact the standards, regulations, and mental classes of a social framework. Thus, people are the miniature level underpinning of legitimacy and address the less contemplated, base up part of institutional examination (Scott, 1995).

Legitimacy is a significant asset since it empowers social entertainers to acquire other significant assets vital for endurance (Suchman, 1995). Beverland and Luxton (2005) noticed that organizations get by to the degree that they are viewed as genuine by their public. Institutional theory describes legitimacy as a generalized perception that an organization’s actions are in conformity with the socially constructed system of norms, values, and beliefs (Higgins & Gulati 2006). Vinson et al., (1977) conceptualized legitimacy as an individual’s attitude, influenced by their personal beliefs. The authors follow Meyer and Scott (1983) to describe legitimacy as the acceptability of a phenomenon within the parameters of the social system. Acceptabilit

y has been emphasized in our definition (Santana, 2012; Van de Ven 2007) since it distinguishes legitimacy from the other associated concepts like status and reputation (Deephouse and Suchman, 2008; Tost 2011).

The legitimacy of an organization, its practices and processes are based on the acceptance granted by the constituents of its social system, which is an under-researched area (Bitektine 2011; Tost 2011). The consumers as legitimacy-granting constituency were neglected in the initial studies of Institutional theory. The initial research focused primarily on examining mostly how committed, and resourceful organizations are more likely to structure markets and shape institutions such as firms (Garud, Jain, & Kumaraswamy, 2002), intermediaries (Déjean, Gond, & Leca, 2004), or activists (de Bakker, de Hond, King, & Weber, 2013; Rao, 2009). Gradually, the consumers were considered an important audience to convince, as they could oppose institutional change. This implied that actors willing to introduce change have to consider consumers in order to obtain normative support, or legitimacy. Ansari and Phillips (2011) showcased that the microlevel everyday practices of consumers collectively create and diffuse new practices which allows the organizations to overcome the liability of newness.

Legitimacy is divided into three types: pragmatic, moral, and cognitive (Higgins and Gulati, 2006; Suchman, 1995).

1. Pragmatic Legitimacy refers to as social acceptance granted by the constituent through the practical benefits and/or consequences for them by the organization. Herein the “audiences are likely to become the constituencies” (Suchman, 1995). This dimension is further categorized in three aspects: a) exchange legitimacy-support for an organization’s policies based on the expected benefits to a specific segment of constituents (Dowling and Pfeffer, 1975). Das and Kumar (2011) simplified by stating that this aspect is related to the direct benefits in the form of individual, societal and national well-being that a customer perceives to have received.

2. Moral Legitimacy refers to positive normative evaluation of the organization and its activities by the constituents based on their moral values (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994). This dimension can be categorized into four aspects: a) Consequential aspect is related to the acceptance of the organization’s output and what they accomplish. Scott and Meyer (1991) gave examples of emission standards, mortality rates in hospitals, under this dimension. b) Procedural aspect is based on the approval of organizational procedures and techniques and scrutinizes organizational processes. Procedural legitimacy becomes most significant in the absence of clear outcome measures (Scott, 1992). c) Structural aspect (Scott, 1977) of legitimacy is based on approval of the organization’s structural parameters by the constituents. Scott (1977) described structures as indicators of an organization's socially constructed capacity to perform specific types of work. This kind of legitimacy can be gained they believe that the organization’s structures are morally favored, according to the constituent’s moral code. d) Personal legitimacy is based on the charisma, and personality of an individual organizational leader. Such a leader should establish self within the constituents’ moral taxonomic code of value and belief system.

3. Cognitive legitimacy refers to as social mass acceptance granted by a constituent based on their understanding of the organization as a permanent and compulsory part of their life’s and socio-economic system (Suchman, 1995). This taken for grantedness “is distinct from evaluation: one may subject a pattern to positive, negative, or no evaluation, and in each case (differently) take it for granted" (Jepperson, 1991). Thus, as Aldrich and Fiol (1994) posited that there is a set of legitimacy dynamics which is separate from interest and evaluation and is based on cognition

Although there are many values and beliefs, we focus on a limited set that appears very relevant and are universally applicable to the sharing practices.

Values

A focal aspect in consumer decisions is of values (Thogerson and Oldander, 2002). Endlessly esteem disciplines impact harmless to the ecosystem conduct (Hansla et al., 2008). Extant literature has number of studies wherein the impact of pro-environment values has been studied on the behaviour of the consumer (Ahmad et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020b). Following these examinations, the current exploration attempts to break down the impact of individual qualities viz. selflessness, social, epicurean and prideful on consumers' ability and expectation to legitimize sharing economy practices. As per the Value-beliefs-norms (VBN) framework (Stern et al., 1999) individual qualities, straightforwardly and additionally by implication sway the supportive of climate conduct. The VBN model has been widely applied in literature to understand the green behaviour and attitude of the participants towards acceptance and reception of sharing practices. Additionally, social norms are taken to be a prompt forerunner of conduct (Ajzen, 2002). Accordingly, current study plans to analyze the worth conviction standard relationship and consolidate this model with the Institutional theory inferred consumer legitimacy towards sharing practices.

The need to consolidate values in this sort of study is basic since values influence inclinations, assumptions, and conduct of people from various ages, as on account of Generation Z (Na and Kang, 2018). Values in this study mean the degree to which an individual has a great assessment and judgment of the sharing economy and what it addresses (Davlembayeva, et al., 2020; Yi et al., 2020). Thus, it has been explicitly demonstrated that values connected with adoption, acceptance and social relationships influence shoppers' inclinations related with sharing practices.

Social Values

Social values allude to the utility of an item or administration to propel the customer to be engaged with explicit gatherings (Sheth et al., 1991). Smith and Colgate (2007) characterized this social worth related with imagery. At the end of the day, this element of seen esteem is firmly connected with mental self-view and social character (Sweeney and Soutar, 2001). To be explicit, on the off chance that the green item or administration is considered to assist with working on mental self-view, the buy expectation expands (Finch, 2006). This is on the grounds that the reception of green items can function as a sign that one thinks often about the climate (Bennett and Vijaygopal, 2018). Yoo et al. (2013) observed that consumers who buy green items tend to think often about their emblematic character being esteemed by society. Past examinations tracked down a positive connection between friendly worth and supportable utilization in India (Biswas and Roy, 2015) and green utilization conduct in Portugal (Gonçalves et al., 2016) too. This positive connection between friendly worth and purchaser conduct is deciphered as customers are motivated to flag their economic wellbeing and address their character to other social individuals through their food decision (Costa et al., 2014). Accordingly, the creators set:

Proposition 1: the customers' social values will significantly affect their legitimizing the sharing practices.

Altruistic Values

Altruism is a caring type of inspiration planned to help others without the assumption for remuneration from outside sources (Powers and Hopkins, 2006). Straughan and Roberts (1999) involved benevolence as a psycho-realistic build of green utilization conduct in natural conduct studies. Charitableness is thought of as one of the most significant psychographic factors for making sense of shoppers' supportive of natural perspectives and ways of behaving (Rahman and Reynolds, 2016). Charitableness impacts disposition of shoppers towards green items and their aim to get them (Birch et al., 2018).

The philanthropic worth fundamentally and emphatically impacts green buy mentality and aim towards green hotel choice (Wang et al., 2020). Tan et al. (2020) showed that altruism is a huge indicator of green lodging support goal. Yadav and Pathak (2016) zeroed in on concentrating on the significance of philanthropic worth in deciding the youthful buyers' goal to buy natural food. Discoveries of the review demonstrated that unselfish worth fundamentally decides youth's disposition and aim towards purchasing natural food. Reimers et al. (2017) observed that charitableness has the most grounded impact over buyers' disposition towards earth capable attire which further impacts their buy aim. In view of this rationale, we plan to look at the effect of benevolence on buyers' disposition and buy goal towards green clothing. Consequently, that's what the creators place:

Proposition 2: the customers’ altruistic values will significantly affect their legitimizing the sharing practices.

Hedonic Values

Hedonic values are frequently connected with an elevated degree of client association (Bloch and Richins, 1983), and are consequently critical to grasp the sharing economy conduct of the members. Hedonism connects with the multi-tactile, and emotive parts of one's involvement in items or administrations (Hirschman and Holbrook, 1982). The potential ride sharers might like to partake in the solace of driving (rather than sitting inactive), drive as pressure help or for experience, room-sharers might incline toward isolation, treating oneself, fun and so on (Huttel et al., 2020). Clients want an agreeable assistance experience and are known to focus closer on the advantages they get from the assistance. Along these lines, a shopper with pro-environment attitude will decidedly see the taxi sharing practice, assuming they accept that it diminishes fossil fuel usage and congestion on the streets. Thus, in light of Tsou et al., (2019) idea for a need to concentrate on the effect of indulgent qualities on the sharing economy practices clients' conduct goals, the authors have acknowledged the utility of studying hedonic values.

Proposition 3: the customers' hedonic values will significantly affect their legitimizing the sharing practices.

Egoistic Values

Egoistic values are portrayed as a singular's personal circumstance opposite the general public, including abundance collection, acquiring the, strategic, influential place, and being powerful (Stern et al., 1999). The egoistic value can be conceptualized as supportive of self-idea mirroring a worry by the person for self or their loved ones. Consequently, prideful values reflect convictions about the self-corresponding to nature. As stated by friendly analysts (Dietz et al., 2005) certain qualities may likewise bring down supportive of natural perspectives and affect related ways of behaving. A self-seeker individual pictures the world from the crystal of individual addition, and tries to maximize individual utility. Subsequently, environmentalism has been displayed to connect with vain qualities adversely. Verma et al. (2019) place that advantages to self (selfish qualities), like better personal satisfaction, may rouse people to exhibit and embrace reasonable way of behaving (Verma et al., 2019). Prakash et al. (2019) focused on that people enjoy climate security to lessen the pessimistic effect of various nature-related issues, on self and their family. The said study demonstrated the effect of vain qualities towards buy aim towards eco-accommodating bundled items.

Proposition 4: the customers' egoistic values will significantly affect their legitimizing the sharing practices.

Mediating Role of Social Norms

The present study is based on the extended VBN theory. Choi et al. (2015), asserted that the social norms are an important antecedent towards predicting the behavioral intentions. Vitell and Muncy (1992) had included groups while defining values by stating that values are: “the moral principles and standards that guide behaviour of individuals or groups as they obtain, use and dispose goods and services”, inferring the part played by the groups. The group members values are reflected in their perception of the community’s, their emotions towards the community, and their perspective about the importance of the community (Bagozzi and Dholakia, 2006). Additionally, pro-social values, including altruistic, biospheric and openness to change have been found to positively influence an individual’s pro- environmental behaviour (Karp, 1996). According to recent research (Kumar et al., 2017), social norms influence individuals’ decisions, thereby providing a better explanation for their environment-friendly behavior. Social norms are of importance for an individual since they need to understand how their behaviour is inferred by their peer group including but not limited to family, friends, colleagues or society at large Thøgersen & Olander F (2002).

The more an individual is willing to interact with other people, Wang et al. (2015) assert, higher is their willingness to indulge in collaboration practices with others, including strangers. This assertion in conjunction with the findings by Han et al. (2018), that social norms have a direct and positive impact on an individual’s PEB, allows the authors to replace Personal Norms with Social Norms as mediating variable. Furthermore, Bucher et al. (2016) reported a positive correlation between sociability and both moral and social-hedonistic motives to partake in sharing economy practices. Kumar et al. (2017) too postulated that the social norms influenced the consumers’ decision-making, thereby explaining their positive behaviour towards the natural environment. Consequently, social norms were added as a mediating variable (Figure 1).

Proposition 5: the social norms will mediate the relationship between the personal values and the consumers’ legitimacy granting behaviour towards the sharing practices.

Discussion

In order to mitigate the ‘wicked problems’ of resource overconsumption, climate change, unsustainable consumption, economic inequality, and social alienation, we must consider how to influence human behaviour towards being environment-friendly. Therefore, factors influencing human-behaviour are important to study. The extant literature has accepted the environment friendly credentials of the collaborative consumption. The sharing practices discourage individual linear consumption, thereby, promoting the environmentally-sustainable exchange between the participants.

For shared consumption, current values, attitudes, norms, and habitual behaviors are identified as major inhibitors (Barnes & Mattsson, 2016) therefore; we ground our arguments in VBN Theory of Environmentalism. Many scholars argue that values influence or guide preferences and behaviour (Steg & De Groot, 2012). In our study we posit that a consumer is expected to behave favorably towards the different practices of collaborative consumption and likely to share again if he/she i.e., the consumer has granted the legitimacy to the sharing practice Munoz & Cohen (2017).

Autio & Thomas (2020) posit that higher the number of adopters of a practice, their interrelationship and nature of such relationships, higher is the said practice’s acceptance and the greater its legitimacy. As the consumers worldwide gain familiarity with access-based services (Fritze et al., 2020) and consequently the collaborative consumption practices, they appear increasingly willing to legitimize the sharing practices by staying in Airbnb recommended hotels, ride Ola cabs, and share resources and assets over various platforms.

In this study, the authors postulate that the consumers ranking high on pro-environment behavior will grant legitimacy to different forms of collaborative practices. This, in turn, will lead to higher acceptance levels for these practices within the society in general. In order to increase the acceptance level of the sharing practices, it is important to understand that the consumers associate which practice with which dimension of legitimacy. For the practitioners, the understanding of consumer legitimacy-granting behavior will ensure that they are able to design their offerings (goods and/or services), communication and marketing strategies to increase the legitimacy dimension which is at low levels. This will ensure that they conform to the prevailing demands for pro-environment behavior from the consumers. Thereby countering the ‘normative isomorphism’ i.e the pressure for sustainable practices arising from social groups including the consumers. Simultaneously, they can reinforce the legitimacy dimensions ranked on higher scale by the consumer. Thus, our study seeks to answer Eckhardt et al., (2019) call for studies on how the business practices must adapt Stern et al., (1999).

Conclusion

In the study, the authors propose that the hedonic values should be researched as an independent construct in VBN theory separate from Openness to change as initially proposed. As deduced from the literature, the hedonic aspects of consumption do influence the values and beliefs towards the norms and behavior. We extend the effect of hedonic values on the acceptance-granting behavior of the consumers, which are further likely to affect their choice of consumption- individual or collaborative. The enjoyment derived from self-driving, freedom of choice, expression of individualism may overcome the need to practice sustainable behavior. Consequently, the hedonic values may negatively affect the legitimacy-granting behavior and reject the sharing practices.

References

Ahmad, W., Kim, W. G., Anwer, Z., & Zhuang, W. (2020). Schwartz personal values, theory of planned behavior and environmental consciousness: How tourists’ visiting intentions towards eco-friendly destinations are shaped? Journal of Business Research, 110, 228-236.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ahsan, M. (2020). Entrepreneurship and ethics in the sharing economy: A critical perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 161(1), 19-33.

Aldrich, H. E., & Fiol, C. M. (1994). Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. Academy of management review, 19(4), 645-670.

Autio, E., & Thomas, L. D. (2020). Value co-creation in ecosystems: Insights and research promise from three disciplinary perspectives. In Handbook of digital innovation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bagozzi, R.P., & Dholakia, U.M. (2006). Antecedents and purchase consequences of customer participation in small group brand communities. International Journal of research in Marketing, 23(1), 45-61.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bardhi, F., & Eckhardt, G.M. (2012). Access-based consumption: The case of car sharing. Journal of consumer research, 39(4), 881-898.

Belk, R. (2014). You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. Journal of business research, 67(8), 1595-1600.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bennett, R., & Vijaygopal, R. (2018). Consumer attitudes towards electric vehicles: Effects of product user stereotypes and self-image congruence. European Journal of Marketing.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Beverland, M., & Luxton, S. (2005). Managing integrated marketing communication (IMC) through strategic decoupling: How luxury wine firms retain brand leadership while appearing to be wedded to the past. Journal of Advertising, 34(4), 103-116.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bloch, P. H., & Richins, M. L. (1983). A theoretical model for the study of product importance perceptions. Journal of marketing, 47(3), 69-81.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bitektine, A. (2011). Toward a theory of social judgments of organizations: The case of legitimacy, reputation, and status. Academy of management review, 36(1), 151-179.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Botsman, R., & Rogers, R. (2010) What's Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption, 1.

Bucher, T., Collins, C., Rollo, M. E., McCaffrey, T. A., De Vlieger, N., Van der Bend, D., ... & Perez-Cueto, F. J. (2016). Nudging consumers towards healthier choices: a systematic review of positional influences on food choice. British Journal of Nutrition, 115(12), 2252-2263.

Choi, H., Jang, J., & Kandampully, J. (2015). Application of the extended VBN theory to understand consumers’ decisions about green hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 51, 87-95.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Costa, S., Zepeda, L., & Sirieix, L. (2014). Exploring the social value of organic food: a qualitative study in France. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(3), 228-237.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Davlembayeva, D., Papagiannidis, S., & Alamanos, E. (2020). Sharing economy: Studying the social and psychological factors and the outcomes of social exchange. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 158, 120143.

Deephouse, D. L., & Suchman, M. (2008). Legitimacy in organizational institutionalism. The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism, 49, 77.

Dietz, T., Fitzgerald, A., & Shwom, R. (2005). Environmental values. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour., 30, 335-372.

Dolnicar, S. (2021). Sharing economy, collaborative consumption, peer-to-peer accommodation or trading of space?. Airbnb Before, During and After COVID-19.

Dowling, J., & Pfeffer, J. (1975). Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizational behavior. Pacific sociological review, 18(1), 122-136.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Garud, R., Jain, S., & Kumaraswamy, A. (2002). Institutional entrepreneurship in the sponsorship of common technological standards: The case of Sun Microsystems and Java. Academy of management journal, 45(1), 196-214.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Geissinger, A., Laurell, C., & Sandström, C. (2020). Digital Disruption beyond Uber and Airbnb—Tracking the long tail of the sharing economy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 155, 119323.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gonçalves, H. M., Lourenço, T. F., & Silva, G. M. (2016). Green buying behavior and the theory of consumption values: A fuzzy-set approach. Journal of business research, 69(4), 1484-1491.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Habibi, M. R., Davidson, A., & Laroche, M. (2017). What managers should know about the sharing economy. Business Horizons, 60(1), 113-121.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Han, H., Yu, J., Kim, H. C., & Kim, W. (2018). Impact of social/personal norms and willingness to sacrifice on young vacationers’ pro-environmental intentions for waste reduction and recycling. Journal of sustainable tourism, 26(12), 2117-2133.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hamari, J., Sjöklint, M., & Ukkonen, A. (2016). The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of the association for information science and technology, 67(9), 2047-2059.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hansla, A., Gamble, A., Juliusson, A., & Gärling, T. (2008). The relationships between awareness of consequences, environmental concern, and value orientations. Journal of environmental psychology, 28(1), 1-9.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hawlitschek, F., Notheisen, B., & Teubner, T. (2018). The limits of trust-free systems: A literature review on blockchain technology and trust in the sharing economy. Electronic commerce research and applications, 29, 50-63.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of consumer research, 9(2), 132-140.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hüttel, A., Balderjahn, I., & Hoffmann, S. (2020). Welfare beyond consumption: The benefits of having less. Ecological Economics, 176, 106719.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kumar, R., & Das, T. K. (2011). Interpartner legitimacy in strategic alliances. Behavioral perspectives on strategic alliances. IAP, Charlotte, NC, 301-336.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kumar, B., Manrai, A. K., & Manrai, L. A. (2017). Purchasing behaviour for environmentally sustainable products: A conceptual framework and empirical study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 34, 1-9.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lamberton, C. P., & Rose, R. L. (2012). When is ours better than mine? A framework for understanding and altering participation in commercial sharing systems. Journal of marketing, 76(4), 109-125.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Meyer, J., & Scott, R. (1983). Centralization and the legitimacy problems of local government. In J. Meyer & R. Scott (Eds.), Organizational environments: Ritual and rationality (pp. 199– 215). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publishers.

Möhlmann, M. (2015). Collaborative consumption: determinants of satisfaction and the likelihood of using a sharing economy option again. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 14(3), 193-207.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Muñoz, P., & Cohen, B. (2017). Mapping out the sharing economy: A configurational approach to sharing business modeling. Technological forecasting and social change, 125, 21-37.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Netter, S., Pedersen, E. R. G., & Lüdeke-Freund, F. (2019). Sharing economy revisited: Towards a new framework for understanding sharing models. Journal of cleaner production, 221, 224-233.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Phung, K., Buchanan, S., Toubiana, M., Ruebottom, T., & Turchick-Hakak, L. (2021). When stigma doesn’t transfer: Stigma deflection and occupational stratification in the sharing economy. Journal of Management Studies, 58(4), 1107-1139.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Powers, T. L., & Hopkins, R. A. (2006). Altruism and consumer purchase behavior. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 19(1), 107-130.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Prakash, G., Choudhary, S., Kumar, A., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Khan, S. A. R., & Panda, T. K. (2019). Do altruistic and egoistic values influence consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions towards eco-friendly packaged products? An empirical investigation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 50, 163-169.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rahman, I., & Reynolds, D. (2016). Predicting green hotel behavioral intentions using a theory of environmental commitment and sacrifice for the environment. International journal of hospitality management, 52, 107-116.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Reimers, V., Magnuson, B., & Chao, F. (2017). Happiness, altruism and the Prius effect: how do they influence consumer attitudes towards environmentally responsible clothing?. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Santana, A. (2012). Three elements of stakeholder legitimacy. Journal of Business Ethics, 105, 257–265.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Schor, J. (2016). Debating the sharing economy. Journal of self-governance and management economics, 4(3), 7-22.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sheth, J. N., Newman, B. I., & Gross, B. L. (1991). Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. Journal of business research, 22(2), 159-170.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Smith, J. B., & Colgate, M. (2007). Customer value creation: a practical framework. Journal of marketing Theory and Practice, 15(1), 7-23.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Steg, L., & De Groot, J. I. (2012). Environmental values.

Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., Abel, T., Guagnano, G. A., & Kalof, L. (1999). A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Human ecology review, 81-97.

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of management review, 20(3), 571-610.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sweeney, J. C., & Soutar, G. N. (2001). Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. Journal of Retailing, 77(2), 203-220.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tan, L. L., Abd Aziz, N., & Ngah, A. H. (2020). Mediating effect of reasons on the relationship between altruism and green hotel patronage intention. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 8(1), 18-30.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Thøgersen, J., & Ölander, F. (2002). Human values and the emergence of a sustainable consumption pattern: A panel study. Journal of economic psychology, 23(5), 605-630.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tsou, H. T., Chen, J. S., Yunhsin Chou, C., & Chen, T. W. (2019). Sharing economy service experience and its effects on behavioral intention. Sustainability, 11(18), 5050.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Verma, V. K., Chandra, B., & Kumar, S. (2019). Values and ascribed responsibility to predict consumers' attitude and concern towards green hotel visit intention. Journal of Business Research, 96, 206-216.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yadav, R., & Pathak, G. S. (2016). Young consumers' intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 135, 732-739.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 10-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-11979; Editor assigned: 11-Apr-2022, PreQC No. AMSJ-22-11979(PQ); Reviewed: 24-Apr-2022, QC No. AMSJ-22-11979; Revised: 26-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-11979(R); Published: 28-Apr-2022