Original Articles: 2017 Vol: 21 Issue: 1

Conceptualizing the Bottom of the Pyramid: The Hope-Criticism Dichotomy From an Entrepreneurial Perspective

Inge Janse, University of Groningen

Abstract

C.K. Prahalad proposed that multinational corporations (MNCs) can successfully do business at the ‘bottom of the pyramid’ by adapting their product and service offerings, changing the lives of poor people, and ultimately transforming entire societies by sparking local entrepreneurship. While this notion has both followers and adversaries, we still lack conclusive evidence for or against it. In the view of the authors, this is mainly owing to the lack of a conceptual model explicitly based on Prahalad’s work that permits proper scientific research and goes beyond the numerous case studies that prohibit any generalizable deductions. By applying a systematic literature review process, we identify and summarize relevant, peer-reviewed, academic literature, leading to a conceptual model, as a basis for a call for further advanced research.

Keywords

Bottom of the pyramid, entrepreneurial activity, multinationals, foreign direct investment, transnational entrepreneurship, FDI, MNCs

Introduction

C. K. Prahalad’s work made the academic community aware of the needs of the large number of people living in poverty (Bruton, 2010). His work has become the starting point of a variety of applications, either as managerial strategies for internationalization and the unlocking of new markets, or as preliminary frameworks for academic inquiry (Landrum, 2007; Seelos & Mair, 2007).

Such efforts’ points of origin are usually Prahalad’s two managerial articles published in 2002 (see Prahalad & Hammond, 2002; Prahalad & Hart, 2002), as well as his subsequent book, which merged antecedent works and empirical findings into a coherent concept (Prahalad, 2004). According to these seminal contributions, in contrast to what practitioners and academics in developed countries seem to have anticipated, multinational corporations (MNCs) should not ignore consumers at the ‘bottom of the pyramid’ (BOP) - the billions of people who live on less than $2 per day (Prahalad, 2009) - as a potential market. Prahalad and Hammond (2002) maintain that these - untapped - consumers have the potential to improve those parts of MNCs’ business that may be stagnating. These companies could also realize new market opportunities, growth, costs savings through outsourcing operations, and even innovations that might affect and change the entire organization. This supposition is based on the premise that although these consumers’ individual buying power might be low, their accumulated spending power, even for luxury and/or high-tech products and services, is significant. However, the demand for such products and services is latent.

Prahalad and Hart (2002) take up the same basic arguments, but go beyond the obvious value for MNCs. They claim that MNCs’ investments in the BOP result in “lifting billions of people out of poverty and desperation” (Prahalad & Hart, 2002, p. 2). This can be achieved by establishing a concerted commercial infrastructure at the BOP to create buying power via access to credit and income-generation, to shape aspirations via consumer education and sustainable development, to tailor local solutions concerning product development and bottom-up innovation, and to improve access to distribution systems and communication links.

The proposed concept unites MNCs’ commercial interests with the social needs of those at the BOP. This concept is summarized in Prahalad’s book (2004), with the author arguing that if MNCs adapt their products and services to the specific requirements of those at the BOP, they will not only realize additional revenue, but will also achieve social transformation, and will eradicate poverty by means of the complex interaction between market players, such as private enterprises, development and aid agencies, civil society organizations, local governments, and consumers (London, 2007; Akula, 2008). Moreover, Prahalad maintains that the key to orchestrating these aims is “entrepreneurship on a massive scale” (Prahalad, 2010, p. 26) – suggesting that there is a strong interrelationship between his concept and the initiation of entrepreneurial efforts.

Since their introduction, business scholars have widely discussed these ideas (Pitta & Guesalaga, 2008). However, besides fairly favorable case studies and theoretical discussions, to date, this attention has not yet resulted in extensive scientific research (Bruton, 2010). Will MNCs’ investments in the BOP really produce measurable results? Further, Karnani (2009) dismisses Prahalad’s calculations of the market size at the BOP, and points out that it underestimates the costs involved in MNCs serving these customers. The core of Karnani’s argument is his claim that the present case evidence and the overall BOP proposition are “logically flawed” (Karnani, 2007a, p. 91). This includes the hypothesized impacts on entrepreneurship.

A reason for these counter-arguments is that Prahalad’s core concept – the interrelationships between MNCs’ customized product and service offerings, the BOP customers, the resulting increase in buying power, entrepreneurial activity, and eventual social transformation – remains a mystery. Which interrelations can be observed between the market players and between the influencing variables? Will the proposed interactions have the anticipated effects, especially regarding entrepreneurial activity? How can quantitative research operationalize and measure Prahalad’s concept in order to verify or reject the proposed model? What differences in application of the model might lead to success or failure?

We do not research the real buying power at the BOP, or challenge the underlying assumptions. We do not seek to mediate or take a position between the antagonizing positions of Prahalad and Karnani. We do not focus on the macroeconomic outcomes of related efforts. This article wants to provide the basis that could shed light on Prahalad’s key argument in his original model (Prahalad & Hammond, 2002; Prahalad & Hart, 2002; Prahalad, 2004). This model proposed that MNCs’ involvement in the developing country contexts could lead to economic development and social transformation by increasing individual buying power and entrepreneurial efforts. We conduct an in-depth, systematic literature review of the existing research and studies that apply a BOP perspective in business and management, so as to provide a conceptual model for further quantitative analysis of the effects that MNCs’ involvement in developing economies on individual entrepreneurial efforts.

The Systematic Literature Review Process

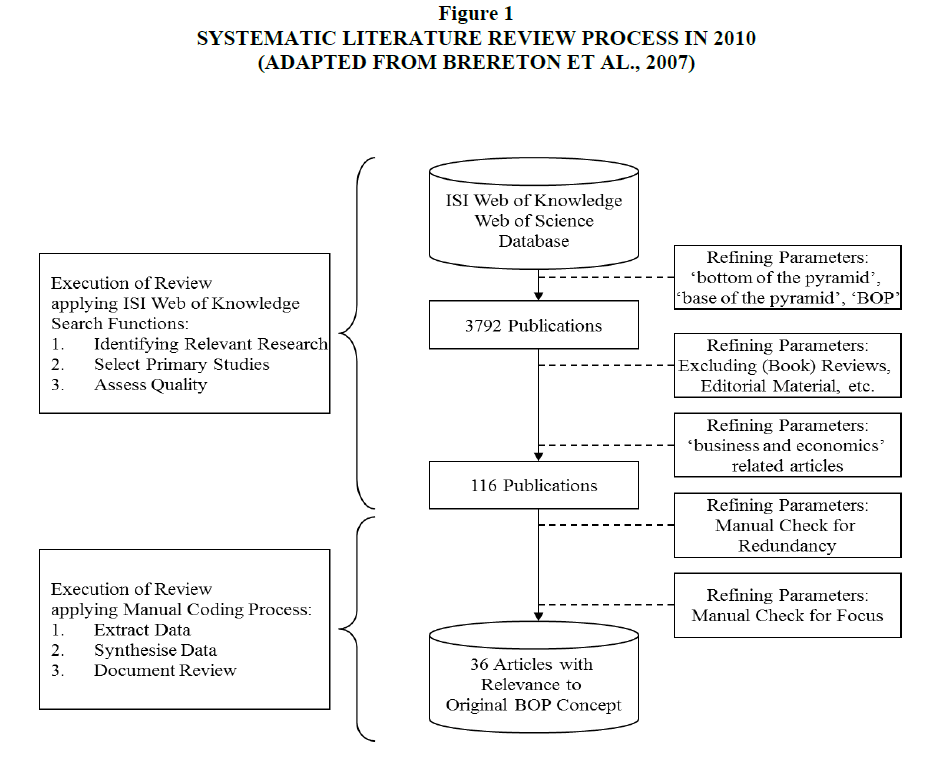

To develop a conceptual model of the BOP, we must review the relevant published material, in addition to the seminal sources by Prahalad and his co-authors. Thus, we undertook a systematic literature review following suggestions by Brereton, Kitchenham, Budgen, Turner, and Khalil (2007) (see Figure 1). To cover a wide range of relevant publications and an extensive spectrum, we accessed the Web of Science database was accessed. We searched for three general search terms: bottom of the pyramid, base of the pyramid, and BOP. Base of the pyramid is a synonym for bottom of the pyramid, which some authors use (e.g. London, 2007).

To ensure the academic relevance of identified publications, we set two cut-off dates to select relevant literature: June 2010 and June 2012. Such an approach and timespan to the date of publication of this article ensures that the selected articles have become part of the academic discourse. In 2010, bottom of the pyramid returned 370 unrefined results, base of the pyramid 962, and BOP 2,460 (3,792 in total). After focusing only on full articles related to business and economics, 37, 30, and 49 results remained respectively (116 in total). All three samples showed some overlap; we manually checked them for redundancy. We excluded articles that did not directly focus on the topic under scrutiny, or did not fulfill expectations in terms of quality. Moreover, we only considered publications that focus on the functioning of BOP models and existing concepts for the sample. We sought to avoid contributions that solely argue from an external MNC perspective (e.g. strategies for entering developing country markets). In 2010, 36 articles remained. We conducted the same query exactly two years later. Table 1 contains the unrefined results of both literature searches. Since these results include various research fields, we filtered the results concerning business and economics. When we put together the results of 2010 and 2012, this resulted in 132, 235, and 149 potentially relevant articles. The manual check was designed to search for qualitative articles that emphasize BOP models and their usefulness. In total, 43 articles are considered relevant material when addressing the current situation of the BOP. These 43 articles’ points of view vary, from authors that agree with the Prahalad’s proposition, to articles by authors who argue the opposite. In the following, we will use these articles, and Prahalad’s work as the source of the discussion and model-building.

| Table 1 : Literature Research Assessed in June 2010 and June 2012 | ||||

| Unrefined results of the first literature search (June 2010) | After filtering for business and economics (June 2010) | Unrefined results of the second literature search (June 2012) | After filtering for business and economics (June 2012) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom of the pyramid | 370 | 37 | 503 | 95 |

| Base of the pyramid | 962 | 30 | 8,371 | 205 |

| BOP | 2,460 | 49 | 4,603 | 100 |

Conceptualizing the Bottom of the Pyramid

Prahalad and Karnani represent different literary streams as well as opposing points of view. Prahalad describes the BOP in terms of untapped potential; here, a fortune can be made if the right strategies are maintained. Karnani disagrees; he understands the concept but states that MNCs might be financially harmed if they engage in BOP practices. Owing to the contradiction between these two authors’ theories, we will now address their statements.

Prahalad (2011, p. 25) proposes that poor people could become profitable potential consumers, despite what little they have to spend, by acknowledging them as resilient and creative entrepreneurs and value-conscious consumers. The combination of making profit and helping poor people to eradicate poverty seems very promising for MNCs worldwide. With many case examples in his writings (Prahalad & Hart, 2002; Prahalad & Hammond, 2002; Prahalad, 2004; Prahalad, 2010), Prahalad makes a convincing argument for MNCs to take the leap and do business at the BOP. His idea goes against many of the assumptions he says most MNCs make: that it is not profitable to do business at the BOP owing to a high cost structure; that the low-income segment cannot afford the products and services made by MNCs; and that only developed markets value innovation and are willing to pay for new technologies. Those assumptions suggest that governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in these developing countries should take account for the low-income segment (Pitta et al., 2008). However, Prahalad disagrees and counters these assumptions. When doing business in low-income countries, four key elements should be considered (Prahalad & Hart, 2002):

1. Creating buying power: providing access to credit and increasing the potential income of poor people are key to eradicating poverty

2. Shaping aspirations: sustainable product innovation and educating low- income consumers will help to adjust expectations

3. Improving access: better distribution and communication systems can help poor to break out of

isolation and can boost development

4. Tailoring local solutions: not global products for all segments, but targeted products adjusted to the BOP – bottom-up innovation and local solutions.

Prahalad has convinced a considerable number of managers of MNCs to act on his proposition. However, Karnani’s advice to these managers is very different. The title of one of his articles – Mirage at the Bottom of the Pyramid (Karnani, 2007b) – indicates this. Karnani disagrees on several points:

1. The BOP’s has been miscalculated: it is much smaller. The World Bank Estimates that the BOP consists of around 2.7 billion

2. The costs of serving poor people are too high: since BOP consumers are geographically dispersed and heterogeneous, MNCs cannot achieve economies of scale

3. The individual transactions represent little money: the people at the BOP only

have $1 or $2 to spend per day; thus, they cannot afford luxury goods

4. BOP consumers are very price-sensitive: 80% of poor people’s income goes to food,

clothing, and fuel; hardly any money is left for other products

5. Poor people should be seen as producers (potential entrepreneurs) rather than consumers: this way, they are not exploited and are they able to improve their economic situations by increasing their income levels.

Karnani (2007b, p. 109) concludes:

Certainly the best way for private firms to help eradicate poverty is to invest in upgrading the skills and productivity of the poor and to help create more employment opportunities for them.

While Karnani and Prahalad both present reasonable arguments, no right or wrong can be appointed. Our summaries of their points of view serve as input for a discussion concerning the BOP subject, integrating the selected articles in the systematic literature review.

Multinational Corporations

Prahalad and Hart (2002) ask a key question: Why are MNCs so important in creating innovation at BOP markets? Although MNCs have the financial resources and can reap benefits of scale and scope, small local organizations are much more responsive to developments in the market. Local entrepreneurs have significant roles, and entrepreneurship should be encouraged. However, MNC involvement is necessary, for the following reasons:

1. They have the resources to create a commercial infrastructure

2. They have global knowledge that can be applied to global markets

3. They can function as a node and catalyst to bring involved parties together

4. They are able to transfer BOP innovations to developed markets.

Prahalad and Hammond (2002, p. 49) state that the poorest regions can only become prosperous through direct and sustained involvement of MNCs. They claim that big companies should solve big problems, and that it is critical to counter poverty. If MNCs are willing to involve in BOP matters, poverty can be addressed. Several MNCs are already involved in BOP markets, and others will also become involved when they discover the opportunities at the BOP. We will now illustrate why MNCs consider poverty reduction to be an issue that relates to doing business.

Doing Well and Doing Good

Not only opportunities to profit drive MNCs to address the four billion people at the BOP, but also the possibility to help them get out of poverty (Prahalad, 2010). MNCs want to do well, and also to do good. The combination of these two goals lead to the BOP proposition. However, to do so, one cannot simply copy Western business models (Hahn, 2008). Traditional views of economic development and business strategy will not hold when entering markets with such potential (London & Hart, 2004). Business models should be adapted, and the focus should shift from high margins to volume (Prahalad & Hart, 2002).

Seeing business as a solution to poverty sounds appealing, but some disagree about the extent of the possibilities. Karnani (2007b) even claims that the BOP proposition is a “mirage” filled with “fallacies”. Garette and Karnani (2010) argue that there is in fact “no fortune at the bottom of the pyramid”; in their view, business opportunities are limited when marketed products’ primary goal is social usefulness. Karnani (2007a) argues that MNC’s behaviors to maximize their profit diverge from the public welfare. Therefore, markets in developing countries need to be constrained. Where governments might not have to power to obstruct these MNCs from maintaining ‘unfair’ business that negatively impact the public welfare, corporate social responsibility may be the best hope. Garette and Karnani (2010) argue that there are very few examples of profitable businesses that simultaneously help public welfare, but that there is no shortage of examples of profit-making MNCs that exploit poor people on a large scale. We must distinguish between charities and businesses that do in fact have a social goal besides the increasing of wealth. To combine corporate social responsibility with a profitable business is a major challenge.

Many business leaders have counted on the BOP proposition put forward by Prahalad, but there has been very little research into business in institutional settings where poverty is dominant (Bruton, 2010). The real incentives for MNCs to the opportunity of serving poor people remain unclear. Is it doing well and doing good, or is it mainly doing well? There is no agreement in the literature. Pitta et al. (2008) discuss the contrast between Prahalad and Karnani, concluding that there is as yet no clear picture of the opportunities at the BOP. Research is needed for us to get a clearer view of how these opportunities can help both MNCs and poor people.

Deriving profit is important, but businesses also contribute to society through innovation and company growth (Ahstrom, 2010). A good firm not only brings profit, but also innovation, which leads to economic growth, employment, and important changes in people’s everyday lives (Baumol, 2004). The connection between business and poverty alleviation primarily lies with the proposition of mutual value creation. In sum, business strategies to alleviate poverty can only exist when MNCs can also generate economic returns (London, 2010).

Market-specific Products and Services

Clearly, with the current cost structure, BOP markets cannot be served, because they cannot afford Western products. Poor people might not have use for the products that are sold in developed countries, but if their functionality is transformed, they could (Prahalad & Hart, 2002). Take the need for sanitation. The need is there, but detergents are not affordable in formats sold in many Western developed countries. To create a capacity to consume affordable packages sold per unit are the solution, according to Prahalad (2011). While people in developed countries can afford to hold stocks, people with $1 or $2 to spend per day cannot. Every day they must decide what they can buy with the little they have. Shampoo is a good example. Since poor people cannot afford large containers of shampoo, the use of single-serving packaging has increased tremendously. Three principles can be maintained when adapting business models, products, and services: 1) affordability (single-serving packages without reducing quality), 2) access (products and services must be geographically distributed), and 3) availability (distribution efficiency is key, because poor people do not postpone their buying or saving). When MNCs adopt their business models to serve BOP markets, they must be aware of the variability of BOP consumers’ cash-flows (Prahalad, 2011).

To be able to serve the BOP, foreign MNCs cannot simply copy their Western business models. When products are offered at the same prices at the same costs, they will not be profitable in BOP countries. Maintaining high margins will not work; instead, volume and capital efficiency will be key. Traditionally, the focus has been on gross margins; however, to pursue BOP opportunities, the focus must be on economic profit (Prahalad & Hart, 2002). To be successful in developing countries, products and services should be adapted to meet market-specific demands. The extent to which that is done influences BOP consumers and entrepreneurs’ consumption behaviors. Products that are perfectly suited for the BOP will sell much easier than unaltered products.

Local Government, NGOs, and the Informal Economy

Partnerships between MNCs and NGOs have been widely discussed in the literature (Brugman & Prahalad, 2007; Chesbrough et al., 2006; Perez-Aleman & Sandilands, 2008). Most studies agree that alliances between these parties are useful owing to their common interest: both want to create innovative businesses to help people at the BOP (Brugman & Prahalad, 2007). Partnerships with NGOs can positively influence the entrepreneurial process owing to a high degree of socialized knowledge, social embeddedness within multiple informal networks, and experience in dealing with diverse stakeholder groups (Webb et al., 2010).

The advantage NGOs have over private sector companies not only relates to their understandings of an environment, but also their lack of time constraints. While for-profit organizations often want to see a profitable result within a short period, NGOs can afford to take their time to implement new business models in order to create sustainable economic development. NGOs differ from for-profit organizations in that they leave the great most profits for small local entrepreneurs to create a sustainable economic ecosystem (Chesbrough et al., 2006)

When MNCs are supported by NGO intermediaries, knowledge, resources, and legitimacy can be provided. The gap that has existed between the private sector and civil society has been filled by MNC-NGO collaboration. Corporations have started to pay attention to the less fortunate and have begun to do business with the BOP. Simultaneously, NGOs are starting businesses to help people to get out of poverty. Owing to a shared interest, and in order to combine forces, MNCs and NGOs are creating new business models in attempts to alleviate poverty (Brugmann & Prahalad, 2007). Partnerships between MNCs and NGOs may have the goal to create a sustainable economic development, but how can small local entrepreneurs be included? These small producers should be included in the supply chain. Standards and agreements should be created by MNC-NGO alliances, and financial and technical support are required in implementation phases. Companies that wish to be successful in BOP countries should not take a short-term approach. They must interact with poorer and smaller companies and include them in global supply chains so as to create sustainability (Perez-Aleman & Sandilands, 2008).

When partnerships between multiple players such as MNCs, government, NGOs, local entrepreneurs, etc. are discussed, one large player is omitted. Besides the formal entities based on legal contracts, there is a large informal economy grounded only on social relationships. Much activity takes place in this informal economy (Webb et al., 2009). It accounts for approximately 40% of gross domestic product in developing countries (Schneider, 2002). This informal economy exists because these entrepreneurs cannot enter the formal economy owing to the high costs involved. Considering the size of this ‘extra-legal’ economy, it cannot be overlooked when doing business at the BOP. We must bridge the informal and formal economies if we are to understand existing social infrastructure (London & Hart, 2004). Considering that it is hard to measure this informal economy and that boundaries are vague, there is almost no empirical evidence in the literature. While it is hard to define how the entrepreneurial process works in the informal economy, it is clear that these entrepreneurs should be considered when MNC-NGO alliances are approaching producers in BOP markets (Webb, 2009).

It is clear that local government, NGOs, and the informal economy influence the relationships between MNCs and BOP entrepreneurs.

Partnerships between MNCs and Entrepreneurs

To be able to pursue opportunities to serve the world’s poor, business models must be adapted. Both such internal changes and external changes should be considered. An under-estimated aspect is partnering with local entrepreneurs. Prahalad and Hammond (2002) emphasize that it is crucial to empower local entrepreneurs. Although MNCs may have scale and cost advantages, MNC managers cannot beat the advantages of local entrepreneurs. Foreign managers are often relied on too much, while local managers have access to local knowledge and local social capital. These local managers have both operational and institutional value. Physical distances between local managers and MNC leaders must be overcome in order to create responsible leadership (Berger et al., 2011). Partnerships with established companies in the market can help to create physical and social infrastructures (Prahalad & Hammond, 2002). MNCs are one among many actors involved in serving the BOP. To be effective, they should partner with NGOs, local government, and communities.

According to Prahalad and Hammond (2002), MNCs are a catalyst in pursuing the BOP opportunity owing to their resources and global knowledge as well as their capacity to unite all actors and transfer knowledge. In contrast, Pitta et al. (2008) argue that MNCs have the weakness of being too large, too rigid, and too far from customers to be effective. Thus, some have suggested a bottom-up approach (Karnani, 2007b). These two starting points show that more research is needed to find out under which circumstances large foreign MNCs should be the ones to lead BOP incentives (Pitta et al., 2008).

When doing business at the BOP, it must be noted that BOP networks work differently to those at the top of the pyramid. BOP networks are more direct and informal; multiple interaction domains among network members are common. However, these networks are harder to predict owing to their unstable character (Rivera-Santos & Rufin, 2010).

According to London and Hart (2004), MNCs should be do four things: collaborate with non-traditional partners, co-invent custom solutions, build local capacity, and develop social embeddedness. Bottom-up learning is key if one is to understand BOP markets. Partnerships with local entrepreneurs is critical for success at the BOP.

BOP Consumers

In the BOP literature, little distinction is made between consumers and producers at the BOP. Prahalad often refers to poor people as potential consumers, while Karnani (2007b) argues that they should be seen as producers. Some clarification of these two terms is required. Prahalad and Hart (2002) mention that the focus should be on the billions of aspiring poor people who are joining the market economy for the first time. They talk about doing business with poor people. It is necessary to adapt products, services, and business models if one is to serve these four billion people. In contrast, Karnani (2007b) prefers to view poor people as producers. He argues that the best way to help to alleviate poverty is to raise poor people’s incomes. We will discuss increasing income and thus buying power later on.

Consumption has many levels. Each level of the pyramid consumes, but differently. It seems logical that poor people cannot consume luxury products, because they cannot afford them. Although consumers at the BOP may have low incomes, they still have self-fulfilling needs. Karnani (2007a, 2007b) argues that, despite this need, poor people do not benefit from consuming luxury goods. They might want to buy them, but cannot afford them. Also, this can lead to misuse – for instance, alcohol abuse. However, research (Subrahmanyan & Gomez-Arias, 2008) has shown that although survival and safety needs are critical, self-esteem and self-fulfillment needs lead to greater opportunities and profits. So, if there is a need, why not adapt and make market-specific products and services to meet the demand?

It is hard to clearly distinguish between BOP consumers and entrepreneurs. In the BOP literature, the two are often used interchangeably. However, we need to separate the two concepts. A BOP consumer does not necessarily have to be an entrepreneur, and vice versa. It Our primary focus is the BOP entrepreneur.

Local Entrepreneurs and BOP Producers

Local entrepreneurs are crucial when new, unsaturated markets are tapped. Still, the effects of entrepreneurial activity in developing countries are under-researched in the BOP literature. To describe the roles of entrepreneurship in the social transformation mentioned by Prahalad (2010), we used additional literature.

There is no consensus in the literature on how to define entrepreneurship. We employ a commonly used definition, that of Venkataraman (1997) and Shane and Venkataraman (2000):

Entrepreneurship is an activity that involves the discovery, evaluation and exploitation of opportunities to introduce new goods and services, ways of organizing, markets, processes, and raw materials through organizing efforts that previously had not existed.

Many authors have researches the roles and effects of entrepreneurship. Acs and Virgill (2010) highlight entrepreneurship’s roles in a country’s development. Change is required to generate economic development, and entrepreneurs are regarded as the best agents for such change. Entrepreneurs are key to responding to market imperfections (Acs & Virgill, 2010). Similary, Autretch and Thurik (1998) write about the shift to an entrepreneurial economy and the increased roles of new and small enterprises. Competitive advantage no longer lies in capital and labor, but in a knowledge-based economy. Two Austrian academics have also highlighted the importance of entrepreneurship: Shumpeter (1947) and Kirzer (1997). Shumpeter (1947) discusses a creative and disruptive response owing to external shocks, considering innovation to be key in discovering new products, processes, and markets. Shumpeter (1947) sees development as a process of disturbance and change instigated by the entrepreneur. In contrast, Kirzer (1997) describes entrepreneurs as people wo seek to restore market disequilibrium. He notes that information is free available for everybody; yet only alert entrepreneurs use this information in innovative ways, using their unique knowledge. Both Kirzner and Shumpeter describe entrepreneurship as a conflux of passing opportunities and alert individuals acting in a situation of economic disequilibrium. Most entrepreneurship in developing countries seems to be Kirznerian, owing to the levels of alertness and responsiveness required and these entrepreneurs’ desire to move to a global norm and push towards an equilibrium. However, in some cases, Shumpeterian entrepreneurship also occurs, although entrepreneurship that leads to entire new technologies is very rare (Hill & Mudambi, 2010).

Entrepreneurial Activity

As noted, there are many definitions of an entrepreneur in the literature. The concept often remains vague. Whickham (2000, p. 42) refers to an entrepreneur as someone who can be considered a manager undertaking an activity, an agent of economic change, and an individual. In his view, the primary difference between an entrepreneurial venture and a small business is the presence of a significant innovation on which a venture is founded, the articulation of strategic objectives, and growth potential. As Koveos and Zhang (2012) note:

Are entrepreneurship and economic growth and development related? This is a complicated question to answer empirically, since both building an entrepreneurial class and showing its impact on economic growth and development are dynamic, long-run processes.

A country’s entrepreneurial activity level can be measured by using entrepreneurial activity and growth indicators. An economy’s extent of market orientation is often used as a proxy for entrepreneurial activity. Koveos and Zhang (2012) indicate that economic performance is related to (potential) entrepreneurial activity.

Economic Growth

Economic growth is a key mechanism to help improve people’s living conditions. In the long run, it even is more important than foreign aid or macro-economic management tools. History shows that economic growth has led to rapid declines of poverty in countries such as China and India. Hundreds of millions of people have already moved from poverty to the middle class (Ahlstrom, 2010). Economic growth can only occur when innovation takes place. Concerning this, Ahlstrom (2010, p. 21) argues that disruptive innovation creates significant new growth in industries and enables less skilled and less affluent people to use products previously used only by wealthier people and organizations.

While there are various views of entrepreneurship in the literature, they all have the same starting point: entrepreneurship is key to economic development. When alert entrepreneurs effectively allocate resources and new firms create new jobs, higher economic growth is likely. For instance, Acs and Virgill (2010, p. 58) suggest that, in developed economies, entrepreneurship can be the engine of economic growth through its impacts on technology and innovation as well as the allocation and mobilization of production factors.

Innovation

Innovation in developing countries differs from innovation in developed countries. Several distinctions must be made. Anderson and Markides (2007) suggest that, in developing countries, the following issues are key: finding new customer groups, creating new products, and creating new business models or new ways to create competitive advantage. They argue that product availability and product affordability are important. Innovators must adapt their products and services in order to be able to serve the lowest-income customers, who often receive their income daily instead of monthly. Products have to meet poor people’s needs not only in price, but also in (cultural) acceptance. Marketing in developing countries also differs owing to limited distribution channels. When issues of affordability, acceptability, availability, and awareness are addressed, strategic innovation at the BOP can take place (Anderson & Markides, 2007).

Several authors discuss disruptive technology as a suitable innovation method. Disruptive innovation, a theory introduced by Schumpeter (1947), suggests that companies should not look for growth in mainstream markets if they want great growth potential. The potential lies in low-income markets in which people’s basic needs are unmet (Hart & Christensen, 2002). Companies can put much effort into creating competitive advantage in developed markets that are already saturated, but they can also choose to compete against non-consumption in developing countries. Zhou et al. (2011) also describe disruptive innovation as an appropriate strategy to serve the people at the BOP. Poor people can benefit from new technologies, while companies have the possibility to disrupt an entire industry. At the BOP, the potential is massive, because developing countries are ideal target markets for disruptive innovation, owing to unmet demands.

Designing innovations to meet the demands of the masses at the BOP is challenging, because business models from developed countries cannot simply be copied. To succeed, companies should adapt to the characteristics and environment of BOP consumers (Ray & Ray, 2011).

Products should be simplified in order to achieve affordability and acceptability in BOP mass markets. Minor adaptations will not lead to significant cost reductions. Companies that want to innovate need to create a disruptive technology from the start. Ray and Ray (2011) agree with Hart and Christensen (2002) that economic use of technology and resources in every stage of the process are critical in order for product innovation to succeed.

Buying Power

Prahalad and Hart (2002) discuss the creation of buying power and focus on access to credit. They point out that increasing poor people’s income levels essential to help them out of poverty, referring to commercial credit as a solution. Most poor people are involved in the informal economy and have no collateral. The extension of microcredit is put forward as their best option, perhaps their only option. Providing poor people with credit presumably can help them to get out of poverty (Prahalad & Hart, 2002).

In contrast, some argue that the problem lies with product affordability and cannot be solved by extending expensive loans and getting them into debt. Karnani (2007b) argues that poor people have limited buying power, because they spent all their money on daily consumer products. Getting poor people to consume more will not solve the poverty problem. They want to consume more, but can’t afford to do so. To increase the buying power of the people at the BOP, their income must be raised, or the products they buy should be of lower quality in order to have lower product prices. When people only have $1 or $2 a day, they can barely afford basic needs, let alone luxury items (Karnani, 2007b).

The assumption that poor people have no money sounds obvious, but is superficial. Although each individual might have a low income and therefore little buying power, poor people’s joint purchasing power or aggregate buying power is large (Prahalad & Hammond, 2002; Martinez & Carbonell, 2007). Poor people often buy luxury items, especially as a group. Many own televisions and/or telephones. While owning a house is not a realistic option, money is spent on products or services that can instantaneously improve daily lives (Prahalad & Hammond, 2002). Doing business with poor people is not restricted by their lack of buying power, but by other barriers such as limited distribution access. We will discuss the influences of these and other entry barriers later.

Not only basic needs are served; luxury items can be purchased with aggregate buying power. Where access to bulk discount stores is non-existent, people at the BOP pay a much higher price for a product or service. Opportunities are observed in selling quality goods at affordable prices while maintaining attractive margins (Martinez & Carbonell, 2007).

Tools can measure buying power; for instance, the buying power index (BPI), which has been used for more than 30 years, measures consumers’ relative buying power in different geographical areas (Guesalaga & Marshall, 2008). Guesalaga and Marshall (2008) show that the buying power at the BOP can also be measured and distributions of BOP expenditures can be calculated. This provides a clearer picture of how income is spent on different product categories at the BOP. Still, it is hard to collect empirical data on how income is spent in different tiers and how regional disparities can pose significant barriers to consumption behaviors.

The question remains how generating entrepreneurs and local consumers can increase buying power. It is hard to get a complete picture of the impact of BOP ventures, because stimulating entrepreneurship at the BOP raises entrepreneurs’ incomes and has bigger impacts. London (2009) referred to three dimensions that are affected by a BOP venture: economic situation, capabilities, and relationships. Local buyers, local sellers, and local communities are impacted.

Incentives to Consume

We will now discuss two incentives for consumption. Microcredit and community play key roles in the BOP process. Both incentives support Prahalad’s (2011) theory and positively influence the process he suggest.

First, opinions on microcredit’s usefulness differ. Some plead for small loans that enable low-income persons to be entrepreneur, while some refer to it as unnecessary debt. Successful cases include Grameen Bank, the pioneer in the field, which has inspired around 25 million microlenders in developing and developed countries (Prahalad & Hart, 2002). Where banks normally ask for a security or pledge, no collateral is needed in microlending. Prahalad (2004, 2010) often mentions microcredit as a solution to increase the buying power of BOP people. Karnani (2007b) is against poor people getting deeper into debt owing to unsuccessful entrepreneurs that must pay very high interest rates. Not every person who has access to a loan is a good entrepreneur. Many microfinance firms failed to help a considerable number of people, owing to their lack of access to commercial funds and the high costs of controlling many these little loans that are geographically dispersed (Akula, 2008). Akula (2008) describes several key issues to succeed in microfinance. The founder of SKS Microfinance in India, proposes three principles that can help MNCs or NGOs to make a profitable business at the BOP: 1) maintain a profit-oriented approach (an investment in poor people can bring profit to them and to investors), 2) use standardized processes, products, and training, and 3) use of technology to reduce costs and to minimize failure.

These microfinancing programs might help entrepreneurs start a business; this might lead to job-creation; increases in income and consumption are the result (Pitta et al., 2008).

Second, a community’s roles in a poor country should be considered. As noted, individuals might not have much to spend, but their aggregate buying power in a community can be large (Prahalad & Hammond, 2002). Even if only a small percentage per household remains after necessities are paid for, a village that pools money can afford luxury items. Cooperatively owned items such as televisions, telephones, and medical services are possible, and can even lead to a community that starts producing products.

Peredo and Chrisman (2006) go one step further by suggesting community-based enterprises (CBEs). In his view, this unconventional form of entrepreneurship can form a promising strategy to alleviate poverty. A CBE is based on a community’s interest, instead of an individual’s interests; in it, the common good is key in the creation of new ventures.

Barriers to Consumption

Prahalad’s proposition to do well and do good sounds appealing to many companies. However, having the goal to simultaneously establish sustainability and improve a company’s financial situation seems challenging. Although BOP theory has gained much attention, few companies have successfully implemented it (Olsen & Boxenbaum, 2009). While most of the literature focuses on external barriers to implementation of BOP theory, Olsen and Boxenbaum (2009) focus on internal organization barriers. Managers often fail to achieve bringing corporate sustainability into practice. There is a lack of implementation-strategy, even among companies with a strong corporate responsibility track record. To be successful, managers should engage in sustainability practices to adopt theory into practice. When internal barriers are overcome, external barriers should not be forgotten. Companies need to ensure that their products are well received by consumers and products are adopted despite the barriers of poverty (Nakata & Weidner, 2012). We will now discuss several barriers to consumption.

The Affordability/Unaffordability of Luxury Goods

Karnani’s (2007b) argument builds on the fact that poor people do need to consume more, but cannot afford it. They may wish to buy quality products, but their limited incomes makes this difficult. Where Prahalad (2010) mentions adapting the ways products are packaged as a solution to affordability, to Karnani (2007b), smaller packages at lower profit margins are a fallacy. Poor people buy small packaged products owing to convenience and their inability to save. Since big containers of shampoo or packets of cigarettes are simply not affordable, small packages and single cigarettes are preferred. Although this way of marketing products can help to manage poor people’s cash-flows and can be more convenient, affordability is not increased; it is only increased when the price per product is reduced.

The Costs of Serving Poor People

A primary concern concerning serving poor people is that these costs are very high owing to a market’s geographical dispersion (Karnani’s, 2007b). Exploiting economies of scale is hard when distribution costs are very high. A weak infrastructure (transportation, communication, media, and legal) further drives up the costs of doing business with poor people (Karnani, 2007b). Seelos and Mair (2007) agree, and discuss the hindrances to investments at the BOP. They question Prahalad’s argument that the BOP presents a massive profit opportunity. If this were the case, and millions can be made that easily, why have companies not already exploited this opportunity at a large scale? The truth is that business models must change fundamentally to serve poor people while generating profits.

Terrorism and Extremism

Although little is known about what motivates people in developing countries to become an entrepreneur, extreme adversity positively influences entrepreneurial activity. This paradoxical observation is explained in the literature (Azevedo, 2010). It is argued that entrepreneurs are incubated when a disruptive event occurs. In environments with terrorism, people need coping skills to deal with a situation and to stay optimistic. Entrepreneurs have a higher adversity quotient than non-entrepreneurs, which enables them to see more opportunities. The main argument holds that entrepreneurs are more likely to respond and take action in situations of unexpected distress. These conditions can help entrepreneurs to approach things differently and respond to transitional opportunities. Setbacks and personal distress can increase self-knowledge and one’s level of functioning. Hoping for a better future can be the basis for engaging in entrepreneurial activities. Individuals are more willing to take risks when disruption occurs. As Azevedo (2005) puts it, the most straightforward explanation for the paradox of enterprise resilience in the face of adversity is that returns to entrepreneurial activities are commensurate with risk.

Branzai and Adblenour (2010) discuss these arguments; their research shows that the escalation of terrorism has the opposite effect. Escalation paralyses and therefore discourages entrepreneurship. Only a few are willing to take the risk, but most people are set back and find more secure ways to support for their families. However, a reduction in terrorism is most likely to encourage entrepreneurial activities. Environments with terrorism create the least economic motivation (Branzai & Adblenour, 2010).

Hall et al. (2012) argue that entrepreneurship often is seen as panacea for inclusive growth in BOP countries, with the negative outcomes often omitted. Crime and social exclusion are often forgotten or not mentioned.

Distribution Access

Prahalad and Hammond (2002) discuss distribution access as a key issue in doing business at the BOP. The problems concerning lack of distribution access are divergent. Distribution is conceived as “the provision of availability”, and channels of distribution are the routes to reach consumers. Problems diverge from information availability to products’ physical availability. Physical barriers relate to bad roads, limited local demand, and high transportation costs. Not only is this a problem for farmers who need to distribute their products, but also for children who want to attend school, for instance. Without available transportation or passable roads, children cannot attend school without having to walk for miles. Another obstacle associated with inadequate infrastructure is a lack of information. No informed choices can be made without the necessary information about buying and selling goods and accessing services. A lack of know-how, skills, and literacy are results of limited distribution access (Vachani & Smith, 2008).

Consumption Behaviors

People consume in some way, regardless of their income level. People also have higher-order needs, even when there is a lack of material goods. Even when people logically cannot afford luxury products, they are consumed (Subrahmanyan & Gomez-Arias, 2008). Some argue that this behavior is created by manipulating consumers. Poor people might want to consume luxury products, but they cannot afford them (Karnani, 2007b). Poor people consume more than just their basic needs. Take the increase in the uses of communication and technology. Low-income households often try to compensate for their lack of status in society by consuming socially visible products. Such compensatory consumption theory might explain why BOP consumers buy luxury products instead of nutritional products or education for their children (Subrahmanyan & Gomez-Arias, 2008).

Negative consumption behaviors such as alcohol abuse can result. Alcohol consumption is a financial drain for BOP consumers, and has economic and social costs. Alcohol abuse exacerbates poverty. Another example of ethical responsibility is the use of skin-lightening cream at the BOP. Karnani (2007a) did a case study on Fair and Lovely skin-lightener. He discusses the moral issue of companies not only selling whitening creams, but their convincing women that they are empowered when they use it. Companies have the right to sell skin-lightening creams to BOP women, but promising empowerment is morally problematic. Overall, such consumption patterns can increase people’s poverty levels.

Corruption

Companies assume that several barriers to commerce make it impossible for them to do business in BOP markets. Corruption, which is common in developing countries, is one (Prahalad & Hammond, 2002). According to Prahalad, corruption can be reduced when private sector competition is free and transparent. However, Adam Smith (1978) points out that corruption can hinder development (Landrum, 2007). Most BOP countries do not realize what the costs of corruption are and how this impacts on private sector development and the poverty alleviation. The – sizeable – informal sector is unable to grow, because informal entrepreneurs cannot attract capital. Thus, they remain small, local, and inefficient. The costs of doing business with the informal BOP sector can only be reduced when governments deal with issues of access and transparency and recognize the changes that must be made in laws and regulations (Prahalad, 2011). The size and influence of corruption is hard to measure, but they are intertwined.

Social Transformation

It is hard for MNCs and NGOs to measure the effects of their investments in the BOP. They often measure their success based on the amounts invested, the number of products sold and distributed, etc. These are quantitative measures. Hardly any qualitative measuring is done to evaluate the influences of their actions. Therefore, it is hard to get an overview of the impacts of MNC involvement in the BOP. London (2009) describes several cases of entrepreneurs who run successful business and who not only have an increased income, but also improve their social environment. He developed a framework to help BOP entrepreneurs assess the impacts of their businesses. Several dimensions are key when a venture’s effects are measured: economic situation, capabilities, and relationships (London, 2009).

Different motivations lead companies to do business in BOP markets. Elaydi and Harrison (2010) compare two strategies: market extension and strategic intent. They investigate the effects of a chosen business strategy on long-term poverty alleviation. Market extension is defined as tapping new markets and creating new customers and increasing use of a product by extending a product category. Strategic intent focuses on long-term effects and possible outcomes. In the case of market extension, the drivers are short-term goals concerning the firm’s size or scale, while strategic intent results in engagement in real poverty alleviation. MNCs with a market extension strategy mainly focus on increase in sales and revenue, a short-term effect. This has little to do with poverty alleviation and may even involve the exploitation of BOP consumers. Companies with strategic intent think of the long-term effects and possibilities of their actions. They engage with communities, and help to grow and transform subsistence markets (Elaydi & Harrison, 2010).

In Prahalad’s (2011) view, the proposition of the BOP he describes can help poor people to get out of poverty. He creates awareness by describing how people at the BOP can become consumers in a whole new market. To serve these BOP markets requires innovation; businesses must adopt their business models. MNCs cannot innovate on their own, but have to partner up and cooperate with NGOs and local entrepreneurs. This process has begun; eventually, this development will lead to social transformation. In Prahalad’s (2011, p. 125, p. 136) words:

When poor people at the BOP are treated as consumers, they can reap the benefits of respect, choice and self-esteem and have an opportunity to climb out of the poverty trap.

And further:

Social transformation is about the number of people who believe that they can aspire to a middle class lifestyle. It is the growing evidence of the opportunity, role models, and real signals of change that allow people to change their aspirations.

The Hope-Criticism Dichotomy From an Entrepreneurial Perspective

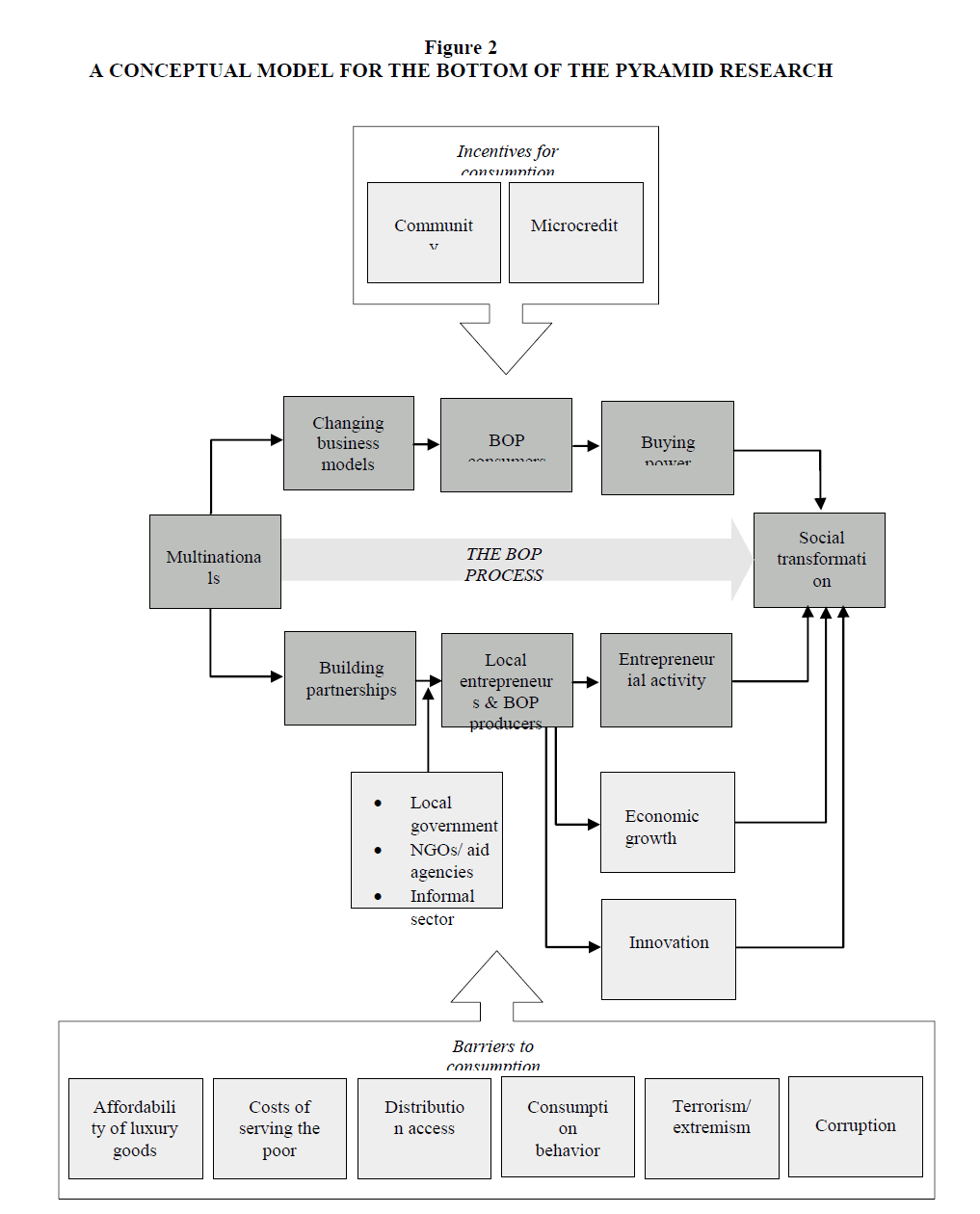

Having discussed the relevant literature, it is now possible to deduct a first conceptual model of research into the BOP concept that is explicitly based on Prahalad’s idea. Figure 2 provides an overview of all relevant interrelations that lay the ground for subsequent propositions and/or hypotheses. The model’s core is the actual BOP process, i.e. Prahalad’s premise of MNCs’ business involvements in developing countries that will lead to social transformation. This premise is at the heart of any successful application of the BOP idea, and is a prerequisite to avoid further exploitation of developing markets by Western industrialized countries. Around this core process, the adaptation of existing business models to the specific requirements of developing countries’ markets, the roles of consumers, producers, local entrepreneurs, as well as partnerships and entrepreneurial activities are well-known concepts presumably involved in social transformation, supported or hampered by local government, NGOs, and/or the informal sector. Most importantly, economic growth and local entrepreneurs’ innovativeness form the key drivers and basis of social transformation at the BOP. Finally, as discussed in the abovementioned literature, there are numerous incentives for and barriers to consumption, which might support or interfere with Prahalad’s assumptions and an ideal BOP process.

How can research into the BOP process be operationalized? One example could be the interrelationships between MNCs and local entrepreneurs. In the BOP literature, empowering local entrepreneurs is key for MNCs entering BOP markets. Knowledge, resources, and legitimacy can be seen as main drivers for MNCs to collaborate with local companies.

However, such partnerships between MNCs and local entrepreneurs, often active as small and medium-sized enterprises, are perceived as controversial. Audretsch and Thurik (2001) highlight the transformation from a managed economy, in which stability, long-term relationships, and continuity are important, to an entrepreneurial economy, in which flexibility, change, and a turbulent environment are much more relevant. In a managed economy, in which scale and scope dominate, small firms are perceived negatively because of the less efficient use of resources due to small size. To create competitive advantage, an MNC should have the capacity to identify, extract, and diffuse knowledge resources in the organization. Mobilizing knowledge is often seen as tradeoff between the overall view of an MNC and the local knowledge possessed by national companies (Asakawa & Lehrer, 2003).

While MNCs may have the advantage of scale and scope, the know-how and knowledge of the local entrepreneurs are much-needed ingredients for success. Thus, MNCs entering BOP markets must acknowledge local entrepreneurs’ roles and must find a way to collaborate with them. While this makes sense, it needs to be critically assessed whether the often significant power distance in the international market between global MNCs and local entrepreneurs does not lead to the exploitation of one by the other, thus resulting in new dependencies and obstacles to both economic growth and the innovativeness of small businesses and entrepreneurs. In this context, the following propositions can be considered:

1. Local businesses and the local economy are positively/negatively influenced by the entry of MNCs into BOP markets

2. Entrepreneurial activities are positively/negatively influenced by the entry of MNCs into BOP markets

3. Successful collaboration between MNCs and local entrepreneurs leads to social transformation.

Such a focus on one of the proposed interrelationships of the conceptual model opens several potential research questions and sheds light on the validity of the core premise of Prahalad’s idea.

Again, we make a strong plea to follow the above example, to explore the conceptual model, and to formulate research questions for the application of own qualitative and quantitative research. Only by doing so, not only might Prahalad’s concept be operationalized but also an urgent question of social and economic development at the BOP might eventually be answered.

References

- Acs, Z. & Virgill, N. (2010). Foundation and Trend in Entrepreneurship.

- Ahlstrom, D. (2010). Innovation and Growth: How Business Contributes in Society. Academy of Management Perspectives.

- Akula, V. (2008). Business Basics at the Base of the Pyramid. Harvard Business Review.

- Anderson, J. & Markides, C. (2007). Strategic Innovation at the Base of the Pyramids. MIT Sloan Management Review, 49(1).

- Arnould, E.J. & Mohr, J.J. (2005). Dynamic Transformations for Base of the Pyramid Market Clusters. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science.

- Asakawa, K. & Lehrer, M. (2003). Managing Local Knowledge Assets Globally: The Role of Regional Innovation Relays. Journal of World Business, 38, 31-42.

- Audretsch, D.B. & Thurik, A.R. (2001). What's New about the New Economy? Sources of Growth in the Managed and Entrepreneurial Economies. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10(1), 267-315.

- Azevedo, J.P. (2005). An investigation of the labor market earnings in deprived areas: A test of labor market segmentation in the slums. http://www.anpec.org.br/encontro2005/artigos/A05A162.pdf, Accessed 7 February, 2008.

- Basu, R., Sengupta, K. & Guin, K.K. (2012). Format Perception of Indian Apparel Shoppers: Case of Single and Multi-Brand Stores. The IUP Journal of Marketing Management, 11(3), 25-37.

- Baumol, W.J. (2004). The free-market innovation machine: 22, Academy of Management Perspectives August Analyzing the growth miracle of capitalism. Princeton.

- Berger, R., Choi, C.J. & Kim, J.B. (2011). Responsible Leadership for Multinational Enterprises in Bottom of Pyramid Countries: The Knowledge of Local Managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 101,553-561.

- Bettis, R.A. (1991). Strategic management and the straightjacket: an editorial essay. Organization Science, 2(3), 315-319.

- Branzai, O. & Abdelnour, S. (2010). Another Day, Another Dollar:Enterprise Resilience under Terrorism in Developing Countries. Journal of International Business Studies, March 2010.

- Brugmann, J. & Prahalad, C.K. (2007). New Social Impact. Harvard Business Review.

- Bruton, G.D. (2010). Letter From the Editor, Business and the World’s Poorest Billions-The Need for an Expanded Examination by Management Scholars. Academy of Management Perspectives.

- Chari, A. & MadhavRaghavan, T.C.A. (2012). Foreign Direct Investment in India’s Retail Bazaar: opportunities and challenges. The World Economy, 79-90.

- Chesbrough, H., Ahern, S., Finn, M. & Guerraz, S. (2006). Business Model for the Technology in the Developing World: The Role of Non-Governmental Organizations. 48(3), 48-61.

- Choi, C.J., Kim, S.W. & Kim, J.B. (2010). Globalizing Business Ethics Research and the Ethical Need to Include the Bottom of the Pyramid Countries: Redefining the Global Triad as Business Systems and Institutions, Journal of Business Ethics, Springer 2009.

- Eisenhardt, K.M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532- 550.

- Elaydi, R. & Harrison. C. (2010). Strategic Motivations and Choice in Subsistence Markets. Journal of Business Research, 63, 651-655

- Fine, S., Meng, H., Feldman, G. &Nevo, B. (2012). Psychological Predictors of Successful Entrepreneurship in China: An Empirical Study. International Journal of Management, 29(1), 279-292.

- Garrette, B. & Karnani, A. (2010). Challenges in Marketing Socially Useful Goods to the Poor. California Management Review, 52(4), 29-48.

- Guesalaga R. & Marshall, P. (2008). Purchasing Power at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Differences across Geographic Regions and Income Tiers. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 25(7), 413-418.

- Hahn, R. (2009). The Ethical Rational of Business for the Poor - Integrating the Concepts Bottom of the Pyramid, Sustainable Development, and Corporate Citizenship. Journal of Business Ethics, 84, 313-324.

- Hall, J., Matos, S., Sheehan, L. & Silvestre, B. (2012). Entrepreneurship and Innovation at the Base of the Pyramid: A Recipe for Inclusive Growth or Social Exclusion. Journal of Management Studies, 49(4), 785- 812.

- Halepete, J., Iyver, K.V.S. & Park, S.C. (2008). Wal-Mart in India: a success or failure?. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 36(9), 701-713.

- Hart, S.L. & Christensen, C.M. (2002). The Great Leap: Driving Innovation From the Base of the Pyramid. MIT Sloan Management Review, Fall 2002.

- Karnani, A. (2007). Mirage at the Bottom of the Pyramid, How the private sector can help alleviate poverty,California Management Review, 49(4).

- Karnani, A. (2007). Doing Well By Doing Good-Case Study: ‘Fair & Lovely’ Whitening Cream. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 1351-1357.

- Khanna, T. & Palepu, K.G. (2006). Emerging Giants: Building World-Class Companies in Developing Countries.Harvard Business Review, 60-69.

- Koveos, P. & Zhang, Y. (2012). Regional Inequality and Poverty in Pre- and Postreform China: Can Entrepreneurship Make a Difference?. Thunderbird International Business Review, 54(1), 59- 72.

- Kuriyan, R., Ray, I. & Toyama K. (2008). Information and Communication Technologies for Development: The Bottom of the Pyramid Model in Practice. The Information Society, 24, 93-104.

- Kwasi Fosu, A. (2010). Inequality, Income and Poverty: Comparative Global Evidence. Social Science Quarterly, 91(5), 1432-1446.

- Landrum, N.E. (2007). Advancing the Base of the Pyramid Debate. Strategic Management Review, 1,1-12.

- London, T. (2009). Making Better Investments at the Base of the Pyramid. Harvard Business Review, 106-113.

- London, T. & Hart, S.L. (2004). Reinventing Strategies for Emerging Markets: Beyond the Transnational Model, Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5), 350-370.

- London, T., Anupindi, R. & Sheth, S. (2010). Creating Mutual Value: Lessons Learned from Ventures Serving Base of the Pyramid Producers. Journal of Business Research, 63, 582-594.

- Martinez, J.L. & Carbonell, M. (2007). Value at the Bottom of the Pyramid, Business Strategy Review, London Business School, Autumn 2007.

- Nakata, C. & Weidner, K. (2012). Enhancing New Product Adoption at the Base of the Pyramid: A Contextualized Model. Journal of Product Innovation and Management, 29(1), 21-32.

- Olsen, M. & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). Bottom of the Pyramid: Organizational Barriers to Implementation. California Management Review, 51(4), 100-125.

- Peredo, A.M. & Chrisman, J.J. (2006). Toward a Theory of Community-Based Enterprise. Journal of Management Review, 31(2), 309-328.

- Perez-Aleman, P. & Sandilands, M. (2008). Building Value at the Top and the Bottom of the Global Supply Chain: MNC-NGO Partnerships. California Management Review, 51(9), 24-49.

- Peters, T. (1992). Rethinking Scale. California Management Review, 7-29.

- Pitta, D.A. Guesalaga, R. & Marshall, P. (2008). The Quest for the Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Potential and Challenges. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 25(7), 393-401.

- Prabhu, G.N. & Mishra, A. (2009). Retail in Practice: Multi-Brand Retailing Failures in India. Retail Digest: Oxford Institute of Retail Management, 58-61.

- Prahalad, C.K. (2004). The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Prahalad, C.K. (2011). The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits, Revised and Updated 5th Anniversary Edition. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Prahalad, C.K. & Hart, S.L. (2002). The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid. strategy+business, 26.

- Prahalad, C.K. & Hammond, A. (2002). Serving the World’s Poor, Profitably. Harvard Business Review.