Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 2

Company Benefits and Social Benefits: Exploring Strategies for Fmcg Companies to Implement Mutually Beneficial Social Marketing Programs

Nashwa Nader, Doctoral Researcher at London South Bank University

Abstract

The aim of this study was to present social marketing to multinational fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies as a concept that, unlike commercial marketing, not only benefits the company but also benefits society. Through in-depth interviews and document analysis, this thesis qualitatively analyzed two social marketing campaigns, one launched by Nestle Pakistan and the other by Henkel Egypt. Using the social exchange theory as a framework for analysis, this thesis offers examples and types of benefits that companies and society gain from social marketing. Additionally, this thesis illustrates some of the challenges of social marketing, demonstrating ways and strategies to address these challenges and maximize the benefits of social marketing for the company and society. Most importantly, this study identifies ways in which consumer goods companies can fund social marketing campaigns without increasing their overall budgets

Keywords

Consumer Goods, Developing Countries, Marketing, Social Marketing.Introduction

Social marketing eliminates the middlemen, providing brands the unique opportunity to have a direct relationship with their customers, Bryan Weiner, Internet entrepreneur. In 1999, General Mills came up with a social marketing campaign that later became known as one of America’s most famous breast cancer campaigns (Hessekiel, 2010). “Save Lids to Save Lives,” conducted by General Mills’ Yoplait brand of yogurt, promised that for every lid of yogurt returned by consumers, Yoplait would donate 10 cents to the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. Yoplait then went on to sponsor Komen’s Race for the Cure series, investing in television, online, and magazine advertising of the race, and offering yogurt samples at the races (Kotler et al., 2012). By 2010, the campaign had generated net funds for the Komen foundation worth more than $26 million (Hessekiel, 2010). This is one example from the consumer goods industry of a company implementing a social marketing program aimed at simultaneously benefitting the company (via brand awareness of Yoplait) and society (raising funds for breast cancer research). With this in mind, this study examined the benefits and challenges for multinational FMCG companies of investing in social marketing programs in developing countries. Based on in-depth interviews and document analysis, Nestle and Henkel in Pakistan and Egypt (respectively), this paper offered practical contributions by shedding light on potential strategies consumer goods companies can employ when implementing social marketing projects in developing countries. Additionally, the findings and discussion suggested a couple of ways in which consumer goods companies can invest in social marketing campaigns without having to increase their overall spending.

Globally, in 2014, the consumer goods industry was estimated at a value of $8 trillion and, by 2025, it is expected to reach $14 trillion (Hirose et al., 2015). Considering the financial power of this industry, this study illuminated the benefits and challenges to FMCG companies if they invest in or reallocate part of their existing pool of financial resources toward social marketing programs that benefit communities in developing countries. The overarching objective of this thesis was to suggest some strategies for implementing mutually beneficial social marketing programs for the company and the consumer. Also, this study suggests ways that FMCG companies can fund social marketing programs in developing countries.

Theoretical Framework

The concept of “social exchange” refers to an exchange that takes place between at least two parties in a way that all parties benefit from the exchange (Homans, 1961). In order to increase consumers’ acceptance of and readiness to change behaviors, social marketers must provide them with something beneficial in exchange (Maibach, 1993). In other words, the exchange theory postulates that if social marketers can

“Demonstrate that the perceived benefits to be imposed on the society outweigh the perceived costs of its purchase, consumers are more likely to voluntarily adopt this change and accept the brand” (Maibach, 1993, p.214).

Thus, through a lens of the exchange theory, this study examined how social marketing can achieve mutual benefits for the company and society without having the companies allocate additional investments on top of their existing marketing budgets.

Literature Review

Definitions and Origin of Social Marketing

Lavidge (1970) first introduced the term “social marketing” when he discussed the public’s concern that businesses spend too much of their marketing tools for the sole reason of increasing sales and making profits without paying attention to the societies that companies operate in. More recently, Haddad (2011) defined social marketing as “a tool that promotes the modification of behavior in a society” (p. 16). Many definitions conceive social marketing in relationship to commercial marketing. Hastings (2007) pointed out that social marketing is derived from commercial marketing, and as such social marketing still needs the business shrewdness and knowledge of commercial marketing to achieve change in society. For the purpose of this paper, social marketing is conceptualized as direct marketing tools that use the company’s brands to conduct social projects that will benefit community through conducting facility enhancements projects and/or positive behavioral change campaigns.

Benefits of Social Marketing

Research points to multiple benefits that companies and societies gain when companies foster social marketing campaigns (Du et al., 2007). Consumer loyalty is one of the oft-cited benefits. For example, if a company sponsors a small construction project to provide homes for less fortune people, it can encourage existing consumers to become company/brand ambassadors who spread positive word-of-mouth about the company and purchase its products (Du et al., 2007). Moreover, Lu (2013) examined social marketing principals and found that competitive advantage can be achieved since social marketing relies on an audience-centered approach, in contrast to other companies that primarily focus on developing and promoting their brands to achieve direct sales (Lu. 2013). Thus, based on the preceding literature, this study posited the following research question:

RQ1: What are the potential benefits to FMCG companies of investing in social marketing programs in developing countries?

Additionally, one of the benefits that social marketing campaigns have on society is that companies invest in research to figure out atypical ways to utilize their investment to support the targeted individuals who are in need by providing them with financial, educational, and health support (Blomgren, 2011). Thus, the second research question this paper posed is:

RQ2: What are the potential benefits that societies in developing countries gained from FMCG companies’ social marketing programs?

Limitations of Social Marketing

While small positive changes can happen once, it might be difficult for marketers to maintain these changes in the long run (Kline, 1999). Also, according to Kenny & Hasting (2011), before attempting to encourage any societal change, it is important to understand that society’s norms to ease collaboration and facilitate trust between companies, individuals, social leaders, and influencers. Thus, based on the preceding, the third research question was:

RQ3: What are the challenges to FMCG companies of investing in social marketing in developing countries?

Viewership of Television

In this digital era of media choice, consumer goods companies must consider alternative ways of advertising other than traditional media like television. The social media revolution opened doors for new and unconventional communication forms (Dibb & Carrigan, 2013). Globally, digital advertising is expected to surpass television advertising and become the largest media format in advertising by 2017 (Friedman, 2015).

Social Marketing Strategies

In order to identify ways to maximize benefits of social marketing, Chakraborty (2013) reviewed previous examples of social marketing campaigns in which she studied the "four-stage cycle of innovation model” that consisted of: identifying innovative ways to address societal issues, developing actionable frameworks, scaling successful implementation, and operating and maintaining the social initiative to a point where it can “sustain itself.” Although the literature, offers some social marketing strategies, more research is required to provide strategies for social marketing campaigns conducted by FMCG companies in developing societies. Thus, this paper posed the following research question:

RQ4: What are the best strategies for FMCG companies to implement social marketing programs in developing countries?

Financing Social Marketing Campaigns

Marketing and finance are two terms used interchangeably (Shah, 2010). One way to fund social marketing campaigns is by partnering with companies in different industries. For example, Carrefour, a multinational retailer, partnered with Hewlett-Packard (HP), a U.S. multinational technology company, for the “Ecobin Recycling Program” in Brazil (Carrefour, 2014). “Ecobins” were placed in 140 Carrefour stores in Brazil, allowing customers to dispose printer waste and cartridges that then were sent to HP’s Brazil Recycling Center to produce new material (Carrefour, 2014). Few studies, however, examine funding social campaigns (Niblett, 2005). Thus, the last research question this thesis posed was:

RQ5: What are the ways that subjects think FMCG companies can fund social marketing campaigns in developing countries?

Background

One of the reasons that this study is tackling the consumers-goods industry is because, compared to other industries, it includes some of the largest and oldest companies in the world, with a long history in the market and high awareness levels. This paper focused on Nestle and Henkel, two large FMCG companies. These companies were chosen because they are some of the biggest in the industry.

Both companies implemented social marketing campaigns in developing countries, namely Pakistan and Egypt. Pakistan and Egypt have different current social realities that required different approaches to social marketing campaigns: Egypt, unlike Pakistan, has been heavily influenced by western cultures as a result of its exposure to western media and education (Amin & Khalil, 2017). Pakistan, in contrast, is a traditional Islamic state that lacks Western influence (Ronaq, 2016).

Nestle

Nestle, formed in 1905, is a multinational food and drink company based in Vaud, Switzerland. Nestle offers a wide selection of products, including baby food, bottled water, coffee, and confectionary. Some of its most famous brands are Nescafe, Nespresso, and KitKat (Nestle, 2017). This paper focused on Nestle’s 2009 rural development and dairy farmer training project in Pakistan. Nestle Pakistan initially launched the farmer training campaign because dairy farmers lacked adequate storage facilities for their milk and did not know the best way to care for the buffaloes to produce high quality milk rich. This forced Nestle Pakistan in many cases to pay high tariffs to import milk. For that reason, Nestle Pakistan launched the farmer training project in which it trained male and female farmers and their families on milk production skills, including the best ways to raise cows and buffaloes to produce more and higher quality milk.

Henkel

The second company analyzed in this study is Henkel, founded in 1879 in Dusseldorf, Germany (Henkel, 2016). It’s a multinational FMCG company with three main business units: laundry and homecare, beauty care, and adhesive technologies. Some of its most famous brands include Dial, Persil, Purex, Renuzit, and Schwarzkopf (Henkel, 2017). This thesis examined Henkel Egypt’s social marketing campaign “Al Balad Baladna,” or “This Country is Ours.”

Government corruption, inequality, and a lack of basic human rights in part contributed to the 2011 Egyptian revolution and the resignation of the former President, Mubarak (Rabou, 2015). Shortly after the revolution, Henkel Egypt launched “Al Balad, Baldna” or “This Country is Ours” campaign. After the Egyptian revolution, the protests and fights between people who were with the revolution and anti-revolution had caused disarray in the streets in Cairo. Henkel partnered with TBWA Egypt, a creative agency, and Optimum Media Direction (OMD) Egypt, a media agency, to launch a street-cleaning campaign in which Henkel employees used Henkel’s cleaning products and wore branded t-shirts to clean areas in Cairo (CampaignStaff, 2011). According to the data analyzed for this study, during a span of five weeks, Henkel advertised the campaign on several media channels, such as television, newspaper, and online social platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.

Methods

In-Depth Interviews and Sampling Techniques

This thesis employed semi-structured in-depth interviews and document analysis research methods. Interviewed subjects were sampled using a snowball technique in which one person provides names of others who were associated with the same event (Sadler et al., 2010). Care was taken to ensure that interviewees were involved with the campaigns at different levels, providing a cross-section of jobs and ages. In total, 10 subjects were interviewed (five from each campaign). Subjects from both campaigns were aged from 30 to 45 years old and had around 10 years of experience in the consumer goods industry.

Document Analysis

Besides interviews, this paper also employed document analysis to examine campaign materials produced for both projects. Document analysis is a systematic process that involves reviewing content on printed and electronic documents in order to gain deeper understanding of the topic at hand (Rapley, 2007). Interviews were transcribed by the researcher, and the documents were analyzed using a grounded theory approach (Martin & Turner, 1986) to look for the emergence of common themes and patterns.

Discussion

Benefits

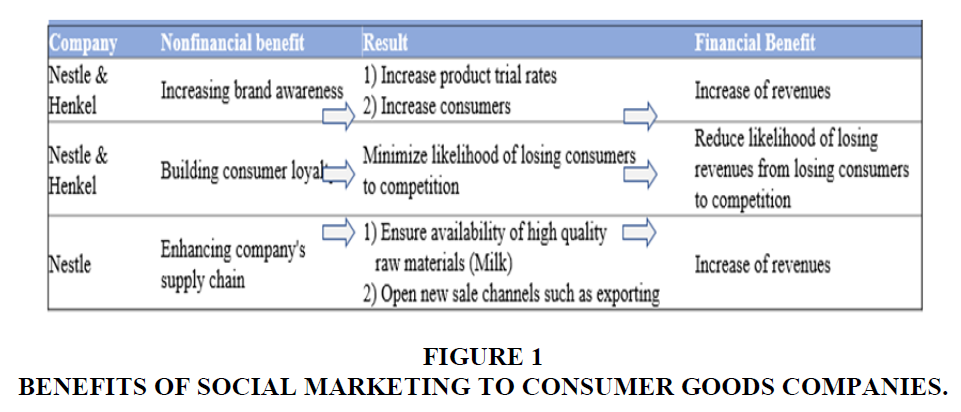

As the findings from the first two research questions suggest, subjects agreed that social marketing campaigns can bring benefits to the company and society. These benefits include increasing brand equity, building consumer loyalty, and enhancing the company’s supply chain. Also, subjects were quick to note these nonfinancial benefits eventually lead to financial benefits. Figure 1 provides a summary of the nonfinancial benefits and the way they can lead to financial benefits.

Nonfinancial Benefits to Companies

The first nonfinancial benefit that emerged from the data that consumer goods companies gain from social marketing campaigns was increasing the company’s brand equity. Respondents said that when a company invests in a project that has real benefits to society and advertise will spread awareness not just about the campaign, but about the company. For example, even though Nestle’s farmer training project’s main goal was not to gain awareness and the campaign was not advertised about on media, respondents said that in the long-run, the farmers and their children would remember and appreciate the efforts of the campaign. While Henkel’s “This Country is Ours” campaign had a main goal of spreading awareness about the company’s brands, the idea was the same: promote the campaign and brand equity will be enhanced. This was evident from the findings that emerged from the document analysis that showed how the campaign’s logos and the t-shirts that Henkel provided had the company’s colors and brand names. Figure 2 demonstrates the placement of Henkel’s brands on the campaign’s logo.

Both companies’ increased brand awareness as a result of social marketing, rather than commercial marketing. The fact that social marketing, rather than commercial marketing, still resulted in improved brand awareness could perhaps assuage any consumer goods companies’ concern that social marketing would not reap rewards, because, increased brand equity is tied to increased sales.

The second nonfinancial benefit of social marketing the findings revealed was consumer loyalty, but only if consumers believe the campaign will directly benefit them or society. The interviewed subjects indicated that Nestle gained consumer loyalty from this program, as when Pakistan’s public became aware of this project and the way it helped farmers. Additionally, the subjects from Henkel claimed that the campaign had an explicit goal to improve loyalty, which was done by directly linking the company’s brands with the campaign. Participants were provided with the Henkel products to use during the campaign. This idea was that consumers would associate Henkel’s brands with a good cause, potentially making them loyal to Henkel.

The third nonfinancial benefit that emerged from the analysis was enhancing a company’s value chain. This benefit only was seen with Nestle’s farmer training project. Since Nestle had problems with its milk supply, the farmer training project was launched with the main goal to increase Nestle’s quality and quantity of milk production. Subjects noted how Nestle ultimately was able to add farmers to its payroll as milk suppliers – a benefit for the company, as well as the farmers.

Benefits to Society

Besides benefitting companies, this study also showed that social marketing benefits societies in developing countries. These benefits to society reflect the social exchange theory as it refers to an exchange that benefits all the involved parties (Homans, 1961). The four main themes of benefits to society that emerged from the findings were learning simple and advanced skills, gaining financial benefits, changing behaviors and enforcing positive habits, and gaining awareness about relevant issues.

The findings suggested that when people learn simple or advanced skills from social marketing campaigns, they highly value these benefits because they can use those skills over a long period of time – potentially making them grateful and thus more loyal to the company. For instance, respondents said that farmers learned innovative farming techniques that increased the health of the cows and buffaloes and, as a result, increased the quality and quantity of milk production. The “four-stage cycle of innovation model” presented by Chakraborty (2013) is mirrored in the planning and implementation of the farmer training project. The four-stage cycle of innovation model consisted of identifying innovative ways to address societal issues, developing frameworks, scaling implementation, and maintaining the social initiative to a point where it can “sustain itself” (Chakraborty, 2013). First, Nestle Pakistan came-up with the new “free farm model” in which buffaloes were left freely to eat grass. Second, Nestle developed a plan launching the project. Third, it explained the project to the farmers. Finally, they started implementing the new farming skills. In contrast, one of the pitfalls of Henkel’s “This Country is Ours” campaign was that the implementation did not follow a sequential process. These findings illustrated that, since most social marketing campaigns are related to teaching skills or changing behavior (Haddad, 2011), the campaign should take place over stages similar to the “four-stage cycle of innovation model” (Chakraborty, 2013).

The second benefit to society of social marketing that emerged from the data was gaining financial benefits. When people learn new skills, they increase their capabilities and thus increase their likelihood of getting jobs or even opening their own businesses. According to the findings that arose from the document analysis, when the farmers implemented the new skills they learned from Nestle’s campaign, they increased their incomes between 20% and 50% on a yearly basis. Also, since those farmers were not exclusive suppliers to Nestle, they had the option to supply milk to other companies as well. In contrast, respondents from Henkel said that “This Country is Ours” did not bring direct or indirect financial benefits to the people.

The third theme of benefits that emerged was related to encouraging people to adapt new positive habits. As per the findings, the new skills and habits that farmers learned from Nestle’s campaign will not be only be passed on to the farmers’ children, but also could influence neighboring farmers. Also, since the new farming habits that the farmers adapted were obviously successful, these new habits influenced nearby farmers. Unlike the Nestle campaign, which is still ongoing, Henkel’s campaign lasted only five weeks. Henkel’s “This Country is Ours” campaign was focused on inducing positive behaviors that also could be shared and passed down. As subjects pointed out, changing behavior requires more time – after the campaign ended, so did the street cleaning. This finding suggests that if companies want to use a social marketing campaign to induce positive behavioral change, it must occur in a persistent manner.

The last theme of benefits to society that emerged from the data was related to gaining awareness about relevant issues. Throughout Nestle’s farmer training project, farmers were educated on the importance of high-quality milk for the nutrition of Pakistan’s children. This increased the farmer’s dedication to the project as they became more aware of the health issues that Pakistan’s children face, and believed that they were positively contributing to the growth of healthier children. Moreover, one of the goals of Henkel’s “This Country is Ours” campaign was to educate the people on the importance of being role models to the upcoming generations.

Challenges of Implementing Social Marketing Campaigns

The third research question of this paper examined the challenges consumer goods companies faced in implementing social marketing campaigns in developing countries. Findings pointed to three main challenges: ensuring the campaign had a clear definition of scope, managing people’s high expectations, and handling people’s lack of trust. In fact, these challenges are interconnected, as people’s lack of trust can result from having their expectations unmet, and a lack of definition of scope can lead to mistrust.

The first challenge was ensuring that the campaign had clear definition of scope. Henkel interviewees indicated that one of the pitfalls of “This Country is Ours” was that the geographical scope of the campaign was not clear to Henkel’s employees, which led to some confusion during the launch of the campaign. For this reason, a company needs to ensure that the geographical scope of the campaign is clear to all of its employees.

The first challenge mentioned above can lead to the second challenge, which is people’s high expectations. Based on the findings, there are a couple of issues that lead to people’s high expectations that companies must tackle. First, when multinational companies plan a social marketing campaign, people expect that the benefits from this campaign will directly benefit them because people are aware that multinational companies make high profits. Second, if the social marketing campaign is about behavioral change, people expect to see immediate results. For example, the farmers in Nestle’s project raised concerns at the beginning of the campaign about how fast they would start seeing positive results in the milk production. For that reason, the respondents indicated that, through the campaign, the company needed to work with the people to keep them inspired for as long as required until the new behavior was embedded in their routines.

The third challenge that emerged from the data was about people’s lack of trust. Respondents indicated that it is crucial for the social marketing campaign to have “SMART” (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound goals (Lawlor & Hornyak, 2012) goals that are clearly communicated to the people so that they know exactly what to expect. Interviewees from Nestle’s campaign said that at first farmers were cynical and not quite clear on the objectives of the campaign. For that reason, Nestle focused on being transparent with the farmers by clearly communicating to them the goals of the campaign by employing the “goode baddee,” or “sister,” who was part of the community and was trusted by the farmers. The “goode baddee” spoke about the goals of the campaign, using concepts and words that the farmers understood, rather than Nestle’s corporate language.

These challenges that emerged from the findings add to the literature suggesting that if the goals of the campaign are not SMART and are not clearly communicated to the public, consumers will have overly high and unmet expectations, which could lead to a lack of trust, and, ultimately, the failure of a campaign.

Strategies for Implementing Social Marketing Programs

As part of the fourth research question, this paper also explored the best strategies for implementing social marketing programs; four main strategies were identified: determining brand awareness and maturity level, assessing the campaign type and the social issues, encouraging the public’s maximum participation in the campaign, and having benefits with lasting impacts.

The first strategy that emerged from the findings was to conduct an analysis determining the levels of awareness and maturity that the brand has reached. Even though one of the benefits of social marketing that emerged from the findings was increasing brand equity, subjects believed that the company’s brands should have high levels of awareness in order for the social marketing campaign to be well-received by the public. In fact, respondents from Nestle and Henkel agreed that the reason that their campaigns were deemed successful is because the companies’ brands were market leaders and had high levels of awareness and maturity in the market. Moreover, this finding indicates that it is preferred if the company had leading brands, because if the brands have high market shares, they are making revenues and the company would not be highly concerned about achieving immediate financial results.

Unlike the first strategy that subjects unanimously agreed on, subjects had conflicting views on the second strategy that emerged from the findings. The second strategy is related to conducting an assessment of the campaign’s type and its relation to the social issue. Respondents from Nestle argued that the nature of the social campaign must be related to the nature of the product type. On the other hand, respondents from Henkel said that if the brands were strong, then a social marketing campaign in any area, even if it’s unrelated to the product, can be successful if it has real benefits to society.

The third strategy was about encouraging the public’s maximum participation and involvement in the campaign. All respondents indicated that two-communication is fundamental to the success of a social marketing campaign. Findings suggested that the means of communication can be in any form as long as it is appropriate to the campaign and accessible to the people. For example, the respondents from Nestle indicated that, throughout the farmer-training program, Nestle conducted regular meetings for the farmers to address any concerns they had and allowed them to ask questions. Also, Nestle hired locals who were trusted by the farmers and interacted with the farmers more frequently than Nestle’s personnel. Henkel had a different approach from the one implemented by Nestle. Since the targeted audience in Henkel’s “This Country is Ours” campaign had access to smart phones and social media applications, the campaign used social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter to communicate with the participants. These findings suggest that whether face-to-face or mediated by technology, the form of communication is less important than the fact that it is two-way.

Finally, the last strategy suggested by the respondents was related to implementing social marketing campaigns that have long-lasting benefits for the people. The findings indicated that in order for the people to fully use the campaign’s benefits over a long time, the campaign should be replicated for at least five years. This paper suggests that the stages of a successful campaign are in fact circular, including informing the people about the social issue, training them, implementation, follow-up where the company ensures that the people are properly applying what they learned in the first stage. Then repeating the first step with new participants. The process described above builds-up on the four-stage cycle of innovation model developed by Chakraborty (2013) by including a step where participants get trained and making the process repetitive. In fact, the respondents from Henkel claimed that “This Country is Ours” could have seen better results if Henkel repeated the campaign according to the process suggested in this paper. Similarly, the subjects from Nestle said that the farmer-training project was successful as it followed an implementation process similar to that suggested above. Accordingly, it can be deduced from the findings that social marketing campaigns should embark on a strategy that ensures that the campaign has long-lasting benefits by ensuring that the implementation takes place over stages in an appropriately paced manner.

Funding Social Marketing Programs

The final research question of this paper examined ways to fund social marketing without increasing a company’s marketing budget. Two main findings emerged: 1) the possibility of companies reallocating funding from television advertising to pay for social marketing campaigns, and 2) the possibility of partnering with NGOs and governments to partially fund the campaigns. Both the Nestle and Henkel campaigns were funded internally from the marketing budget.

When comparing and contrasting respondents’ answers regarding the possibility of reallocating funding from television advertising to fund social marketing campaigns, respondents had differing views. Respondents who were against reducing the television-advertising budget to fund social marketing campaigns believed that a reduction in television advertising could have a negative effect on sales. On the other hand, other respondents believed that if the company’s brands had high-levels of awareness, then reducing television advertising slightly would not drastically affect sales. In fact, respondents who were for reducing television advertising to spend in social marketing believed that social marketing might have positive results on brand awareness which could have positive effect on sales.

After analyzing the different reasons that respondents had on reallocating funds from television advertising to fund social marketing, this paper suggests that shifting funds from television advertising to social marketing campaigns can be a sound strategy if carefully implemented. Even if the company owns strong brands, there are four factors to consider before arriving at such a decision: involving the company’s global head office in the decision, determining the brand’s competitive advantages, determining the amount of television advertising reduction, and assessing the strengths of other media channels. These findings thus indicate that a reduction in television advertising to fund social marketing campaign can bring the brand positive results. This paper thus offers a potentially new way to fund social marketing campaigns by reducing the television budget with careful consideration as discussed above.

The second funding strategy suggested for multinationals to partner with NGOs. However, respondents who suggested these partnerships saw the NGOs as contributing to funding, and not just offering expertise or personnel. These respondents’ suggestion also seems to neglect the fact that NGOs are looking to companies for funding. This perhaps is why only a few subjects supported this strategy. The better model seems to be, as respondents from Nestle indicated, that a partnership with an NGO can indirectly help fund a campaign. For example, USAID provided Nestle with milk storage facilities and experts in farming who supported Nestle. In general, then, the idea of collaborating with NGOs and governments did not receive much support from respondents. Still, such a collaboration could be beneficial if NGOs provide the company with nonmonetary support like human resources or physical facilities to support the social campaign, as was seen in the case of Nestle. Hence, this finding suggests that collaborating with NGOs for direct financial contributions to the campaign may not be the best way to fund the campaigns. However, NGOs can still support the company by equipping the campaign with personnel or facilities.

Conclusion

Using in-depth interviews and document analysis, this paper used the social exchange theory (Homans, 1961) as a framework to qualitatively explore how both a company and society can gain benefits from social marketing. By examining two social marketing campaigns, one from Nestle Pakistan and the other from Henkel Egypt, this research provides a deeper understanding of the benefits and challenges of social marketing. Suggesting strategies to fund social marketing campaigns without requiring the company to exceed its existing yearly spends was a key practical and academic contribution that emerged from the findings.

To summarize, one of the key findings of this paper was that consumer goods companies and society can gain substantial benefits if certain strategies were followed. This paper showed that social marketing can generate nonfinancial benefits that could eventually lead to financial benefits. This study also revealed external and internal challenges that companies face during planning and implementing social marketing campaigns. These challenges can be minimized if consumer goods companies address them while setting strategies for the campaign. Such strategies, as this research revealed, include conducting a prelaunch analysis to determine brand awareness level, assessing the social issues, ensuring the public’s maximum involvement in the campaign, and ensuring that the benefits of the campaign have lasting impacts.

Finally, this study suggested strategies to fund social marketing campaigns without having the need for the company to spend more than it already does on marketing. Those financing strategies are reallocating funds from television advertising to pay for social marketing campaigns. This study suggests that social marketing works best for companies that are not highly concerned about achieving short-term revenues. If a company’s brands hold a strong position in terms of awareness, maturity, and market share, social marketing will seemingly have better results for the company and society, thus achieving Homans’ (1961) understanding of an ideal social exchange.

Another important contribution to scholarly literature is that this study provided a real example of the way social marketing can specifically cater to the precise needs of the company and society, again fulfilling the concept of the social exchange (Homans, 1961). This contribution emerged from the way Nestle Pakistan launched the farmer-training project to attend to its specific need to enhance the company’s supply chain. Additionally, this study contributed to the social marketing challenges presented in literature by showing that there are two types of challenges: external and internal. External challenges refer to the issues the company faced when dealing with the participants in the campaign, and internal challenges refer to the company-specific issues faced during planning and implementation.

While this study contributes to scholarly literature, it also provides practical contributions to the consumer goods industry. First, this paper recommends that only companies that have high levels of awareness should launch social marketing campaigns. Also, if one of the campaign’s goals is to spread awareness about the company, the company can further increase the positive results of the social campaign by advertising about the campaign on media, in particular social media.

Most importantly, this paper indicates that companies can invest in social marketing without having to increase their overall budgets. The analysis suggested that companies can reduce their television advertising budget by a small fraction and invest this money in social marketing if certain conditions were met, as outlined above. If these conditions are met, reducing television advertising to fund social marketing can potentially be an effective strategy for businesses in the consumer goods industry to finance social marketing.

Using data obtained from professional experts in the consumer goods industry who have firsthand experience with the campaigns strengthens this study’s findings and conclusions. Future research should explore the benefits, challenges, and strategies of social marketing from the consumers’ perspective. Finally, based on the social exchange theory, all parties involved in the exchange need to gain valuable benefits that relate to them. As long as society gains valuable and long-term benefits, the idea that the company should gain benefits from social marketing needs to be realized and accepted. Based on the benefits and strategies that this paper suggested, if the company has strong brands with high market share and levels of awareness, the company can afford to minimally give-up short-term results of commercial marketing (such as television advertising) in order to gain potentially long-term nonfinancial and financial benefits from social marketing campaigns.

References

- Amin, H., & Khalili, S.E. (2017). Impact of Western cultural values as presented in the Egyptian movies.

- Retrieved January 25, 2017, from http://dar.aucegypt.edu/handle/10526/3360

- Blomgren, A. (2011). Is the CSR Craze Good for Society? The Welfare Economic Approach to Corporate Social Responsibility. Review of Social Economy, 69(4), 495-515.

- Carrefour. (2014). 2014 Annual Financial Report. Retrieved June 15, 2019, from http://www.carrefour.com/sites/default/files/DDR_2014_EN.pdf

- Chakraborty, S. (2013). CSR Times. Retrieved January 24, 2017, from http://www.csrtimes.com/community- articles/corporate-social-responsibility-and-the-society/205

- Dibb, S., & Carrigan, M. (2013). Social Marketing Transformed: Kotler, Polonsky and Hastings Reflect on Social Marketing in a Period of Social Change, European Journal of Marketing, 47(9), 1376-1398.

- Du, S., Bhattacharya, C.B., & Sen, S. (2007). Reaping relationship rewards from corporate social responsibility: the role of competitive positioning. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 24, 224-241.

- Friedman, W. (2015). Broadcast, Cable Upfront Spending Drops Again. Retrieved May 24, 2016, from http://www.mediapost.com/publications/article/257973/broadcast-cable-upfront-spending-drops- again.html

- Haddad, M.F. (2011). Understanding the effectiveness of social marketing programs through action research (2011). Subai Lynx, 2011 winners and shortlist. Retrieved November 7, 2016, from https://www.dubailynx.com/winners/2011/media/entry.cfm?entryid=1444

- Hastings, G. (2007). Social marketing: why should the Devil have all the best tunes? Amsterdam: Elsevier/Butterworth-HeinemannHastings, G., Angus, K., & Bryant, C.A. (2011). The sage handbook of social marketing. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Henkel. (2016). Retrieved December 10, 2016, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henkel

- Henkel. (2017). Persil Abaya initiates. Retrieved January 21, 2017, from http://www.henkel.com/newsroom/2015-07-15-persil-abaya-initiates-new-beginnings/500848Henkel.

- Hessekiel., D. (2010). The Most Influential Cause Marketing Campaigns. Retrieved September 14, 2016, from http://adage.com/article/goodworks/influential-marketing-campaigns/142037/

- Hirose, R., Maia, R., Martinez, A., & Thiel, A. (2015). Three myths about growth in consumer packaged goods. Retrieved February 18, 2017, from http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged- goods/our-insights/three-myths-about-growth-in-consumer-packaged-goods

- Homans, G.C. (1961). Social behavior: its elementary forms. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Kenny, P., & Hastings, G. (2011). Understanding Social Norms: Upstream and Downstream Applications for Social Marketers. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Marketing. London: Sage Publications.

- Kline, W.N. (1999). Hands-On Social Marketing: A step-by-Step Guide. USA: SAGE publications.

- Kotler, P. (2000) Marketing Management (Millennium Edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall International.

- Kotler, P., Hessekiel, D., & Lee, N. (2012). 3 Stories of Advancing Cause and Profits. Retrieved September 14, 2016, from https://www.fastcompany.com/1842562/3-stories-advancing-causes-and-profits

- Kotler, P., & Zaltman, G. (1971). Social Marketing: An Approach to Planned Social Change. Journal of Marketing, 35(3), 3-12.

- Lavidge, R.J. (1970). The Growing Responsibilities of Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 34(1), 25-28.

- Lawlor, B., & Hornyak, M.J. (2012). SMART Goals: How the Application of SMART Goals can ontribute to Achievement of Student Learning Outcomes. Developments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learning, 39, 259-267. Retrieved January 30, 2017, from https://journals.tdl.org/absel/index.php/absel/article/viewFile/90/86.

- Lu, A. (2013). Barriers and Benefits: Changing Behavior Through Social Marketing. Retrieved January 14, 2017, from http://www.sustainablebrands.com/news_and_views/behavior_change/changing-behavior- through-social-marketing

- Maibach, E.W. (1993). Social marketing for the environment: Using information campaigns to promote environmental awareness and behavior change’, Health Promotion International 8(3), 209-224.

- Martin, P., & Turner, B. (1986). Grounded Theory and Organizational Research. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 22(2). Retrieved January 19, 2017, from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/002188638602200207

- McQuerrey, L. (2012). The Advantages of Qualitative Interviews. Retrieved February 20, 2017, from http://work.chron.com/advantages-qualitative-interviews-17251.html

- Nestle. (2017). Retrieved January 17, 2017, from http://www.nestle.com/aboutus/overview

- Nestle Public affairs. (2016). Nestlé in society Creating Shared Value and meeting our commitments 2015.

- Retrieved February 7, 2017, from http://www.nestle.com/csv/reports

- Niblett, G.R. (2005). Stretching the Limits of Social Marketing Partnerships, Upstream and Downstream: Setting the Context for the 10th Innovations in Social Marketing Conference. Social Marketing Quarterly, 11(3-4), 38-45. doi:10.1080/15245000500308930

- Rabou, A.A. (2015). Egypt. Political Insight, 6, 36-39. doi:10.1111/2041-9066.12101 Rapley, T. (2007). Doing conversation, discourse and document analysis. London: Sage.

- Ronaq, S. (2016). 11 Key Traits of Pakistani Culture. Retrieved February 03, 2017, from http://www.sharnoffsglobalviews.com/pakistani-culture-traits-244/

- Sadler, G.R., Lee, H., Lim, R.S., & Fullerton, J. (2010). Research Article: Recruitment of hard-to-reach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nursing & Health Sciences, 12(3), 369-374. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00541.x

- Shah, B. (2010). Fusion for profit: How marketing and finance can work together to create value20101Sharan Jagpal. New York, NY: Oxford university press 2008. Ix+636 pp., ISBN: 978-0-19-537105-5’, International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 4(1), 104-106.

- Shenton, A.K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63-75. doi:10.3233/efi-2004-22201