Research Article: 2024 Vol: 28 Issue: 4

Command and Control Methods in Controlling Employee Behavior within Kuwaiti Work Organizations

Ali Muhammad, Kuwait University

Citation Information: Muhammad A., (2024). Command and Control Methods in Controlling Employee Behavior Within Kuwaiti Work Organizations. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 28(4),1-13

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to develop and test a theoretical framework which demonstrates the relationships between command-and-control mechanisms and employee compliance with organizational rules and policies in Kuwaiti business organizations. The framework suggested that trust in organization and procedural justice may play an important role in moderating the relationships between command-and-control mechanisms and employee compliance with organizational rules and policies. The framework adds to previous research by introducing new variables to the models demonstrating employees’ compliance. Structural equation modelling is used to analysis the data and examine the direct and indirect effects. A discussion of issues related to employee compliance is presented, and recommendations for future research are discussed

Keywords

Command and Control Methods, Organizational Trust, Adherence to Rules, Procedural Justice

Introduction

Controlling employees’ behavior is a goal organization strive to attain. Effective organizations utilize various mechanisms to make sure that employees act in accordance with organizational rules and) policies (Li, Wang, & Hamari 2021; Vardi & Weitz, 2004). Previous research identified two methods through which organizations attempt to control employee’s behavior. The first method is internal; it focuses on using employees’ ethical values as a tool for regulating their behavior and motivating them to adhere to organizational rules and policies. It is based on employees’ ethical perception regarding the lawfulness of organization rules and the coherence of employee’s ethical values with those of their organization (Kelman & Hamilton, 1989; O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986).

The other method is external because it uses external reinforcement to control employee’s behavior. The external method relies heavily on the use of positive (reward), and negative (punishment) to regulate employees’ behavior within the organization. The study of Tyler & Blader (2005) compared the impact of external and internal methods on employees’ motivation to adhere to rules. Their findings impact that internal methods of control (ethical values) have greater impact on employees’ desire to follow rules that extremal methods (reward and punishment). These findings were further confirmed by Nan Zhu, Yuxin Liu, Jianwei Zhang, & Na Wang(2023). Procedural justice was found to have a moderating effect between ethical judgment and rule following. Furthermore, cognitive evaluation theory suggests that the introduction of external reinforcements diminishes the effect of internal motivation (Carton, 1996).

The purpose of this paper is to investigates the effectiveness of the external approach on motivating Kuwaiti employees to follow. More specifically, the study examines the impact of employees’ expectations of his rule breaking behavior being detected on his desire to abide by rules. Furthermore, the study examines reaction to rule breaking behavior and the impact of this reaction on employees’ adherence to rules. The role of procedural justice and organizational trust in moderating the relationship between external reinforcements and rule following behavior will also be examined.

Goals of the Study

The study attempts to achieve the following goals:

1. To investigate the effectiveness of command-and-control methods in Kuwait business organization

2. To test the effect of demographic variables on employee compliance with rules.

3. To examine the moderating effect of procedural justice in the relationship between command and control and employee compliance with rules.

4. To examine the moderating effect of trust in the organization in the relationship between command and control and employee compliance with rules.

Importance of the study

There are a several theoretical and practical implication of this research. The current paper attempts to examine new variables that influence employee compliance with organizational policies. A new model of employee compliance is presented; this model includes moderating variables, which, as far as we know, are tested for the first time. The moderating variables include trust in organization, and procedural justice.

The practical implications of this study stem from the fact that it will provide practitioners with a new and more comprehensive model of employee compliance. With new moderating variables, the new model further explores the factors affecting employees’ compliance within business organization. Organizations may use the new model to improve and develop work systems that contribute to the enhancement of employee compliance with rules.

Command and control and adherence to rules

To establish the relationship between command and control and adherence to rules we invoke reinforcement theory of motivation (Skinner 1968). Based on reinforcement theory, employees’ adherence to rules is a result of rewards and punishment they relate to compliance with organizational rules. The command-and-control method is based on the premise that employees seek to maximize the rewards they receive from the organization and avert punishment. Accordingly, organizations provide rewards to motivate desired behavior and punishment to stop undesired behavior. The argument in favor of command and control is that workers are in organizations with an instrumental motivation. As a result, their primary focus is on the benefits and resources they obtain from their work. Therefore, companies must actively participate in enforcing norms by offering rewards for desired behavior and penalties for unruly behavior.

Furthermore, traditional economics suggests that in an ideal world, people would always make the best decisions based on a careful analysis of the costs and benefits of each option available to them. According to this view, rule following is a function of the costs and benefits people associate with adherence to those rules (Blair & Stout, 2001). In a recent study, researchers examined the impact of contingent rewards and punishment on employee compliance behavior. Their findings indicate that positive effect of contingent rewards on compliance behavior (Zhu et. al 2023). Other research findings indicate that the direct and interactive influences of the costs and benefits that employees perceive in alternative compliant and non-compliant behaviors play a key role in their rule following behavior (Khatib, & Barki, 2022).

Hypothesis 1: command and control method will be positively related to adherence to rules.

Organizational Trust and adherence to rules

The first to show that there are significant distinctions between organizational and interpersonal trust—as shown by general organization trust and trust in coworkers and supervisors—was Luhman (1979). The ability of one side to rely on the other with a sense of relative comfort despite the possibility of unfavorable outcomes is known as interpersonal trust (McKnight, Cummings, & Chervany, 1998). According to research by Korsgaard, Brodt, and Whitener (2002), interpersonal trust has a substantial relationship with a number of work-related factors, including performance, problem-solving skills, citizenship behavior, cooperation, and communicationquality.

Based on organizational responsibilities, relationships, experiences, and interdependencies, people's favorable expectations about the intentions and behaviors of various organizational members are largely responsible for building organizational trust (Shockley- Zalabak, Ellis, & Winogrand, 2000). As Kaneshiro (2008) points out, organizational trust is defined as having four components: competence (skill, expertise), integrity (character, credibility, honesty, openness, truthfulness), benevolence (care, concern, altruism, accessibility, availability, cooperativeness), and consistency (reliability, dependability, predictability).

According to the social information processing approach (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978), the social environment provides cues which individuals use to construct and interpret events, it also provides information about what a person’s attitudes and opinions should be. Employees’ trust in an organization is likely to influence their perception of the quality of their exchange relationship with the organization i.e., perceived organizational trust (Abd Ghani & Hussin, 2009). To the extent that employees’ willingness to assume a risk and relinquish control in the hope of receiving a desired benefit from their organizations contribute to their adherence to rules, organizational trust may be considered as an antecedent to employees’ adherence to rules. Recent findings indicate that organizational trust is an antecedent to compliance behavior, as organizational trust increase, employee deviant behavior decline (Abbasi, Wan, & Wan, 2023)

Hypothesis 2: Organizational trust will be positively related to adherence to rules.

Hypothesis 3: Organizational trust will moderate the relationship between command and control

and adherence to rules.

Procedural justice and adherence to rules

Justice of the procedures leading to a decision's conclusion is referred to as procedural justice (Leventhal, 1980; Leventhal, Karuza, & Fry, 1980; Thibaut & Walker, 1975). Thibaut and Walker (1975) developed two criteria for procedural justice, focusing on how disputes react to court proceedings: (1) the capacity to express one's opinions and arguments throughout a procedure (process control); and (2) the capacity to have an impact on the decision-making process itself (decision control). The extant research has provided strong support for these control-based procedural fairness standards (Lind & Tyler, 1988).

Early studies within the practice of performance appraisals have demonstrated that giving employees the opportunity to express their views and feelings (process control) was strongly related to perceived fairness of their performance appraisal procedures (for a review; see Greenberg 1990). Organizational justice research has consistently shown that voice effect (process control) enhances individual’s evaluations of procedural fairness (Greenberg, 1990; Lind, Kanfer, & Earley, 1990; Organ & Moorman, 1993; Lind & Tyler, 1988; Tyler & Lind, 1992). More recently, the study by Dulebohn & Ferris (1999) found a positive association between the use of supervisor-focused tactics (voice effect) and procedural justice evaluations. In line with these findings, Lind, Kulik, Ambrose, and Vera Park (1993) found the opportunity to present information to the authority to be one of the most influential factors generating procedural justice.

Lind and Earley (1991) suggested that independent relationship between procedural justice and adherence to rules can be explained using group value model of procedural justice (Lind & Tyler, 1988). The group value model suggests that an employee sees procedures as fair to the extent that they communicate that the employee is respected and valued member of a work group. Allowing employees greater input (voice) into procedures increases perceptions of the fairness of those procedures not only because employees having voice may influence the fairness of the distribution of rewards, but also because their having the opportunity to express their opinions and feelings demonstrates that the group considers their output is of value.

According to Lind and Early (1991), organizations that place a high priority on group concerns and cognitions are more likely to experience adherence to rules. A focus like this frequently encourages workers to prioritize group benefits above individual ones. Thus, workers may utilize adherence to rules to uphold and sustain the group and look for methods to enhance itswell-being.

An explanation for the possible positive correlation between procedural justice and rule adherence can also be found in the social exchange theory (Organ, 1988). Relationships involving vague future responsibilities are referred to as social exchanges (Konovosky & Pugh, 1994). Employee trust in the other parties' long-term fair performance of their duties is the foundation of social exchange relationships.

Because employees' perceptions of the fairness of organizational rules and procedures contribute to the establishment of social exchange connections between employees and their company, procedural justice may be related to compliance with rules (Organ, 1988). According to Gouldener's (1960) norm of reciprocity, employees are expected to reciprocate when they believe their organization is treating them fairly. This reciprocation is based on social exchange relationships, where employees are expected to comply to corporate regulations and procedures.

Hypothesis 4: Perceptions of procedural justice will be positively related to adherence to rules.

Hypothesis 5: Procedural justice will moderate the relationship between command and control

and adherence to rules.

Methodology

Participants and Procedures

Nine corporate entities in the State of Kuwait were the sites of this study. Questionnaires that respondents self-administered were used to gather data. A survey was administered to 300 workers, both supervisory and non-supervisory. This survey methodology produced a response rate 70% (N= 212). The complete sample, out of all participants, was made up of Arab employees see Table 1.

The surveys were anonymous to guarantee the objectivity of the participants. Participants were guaranteed the privacy of their personal data. For follow-up, a random code was appended to every survey questionnaire. The survey list and numbers were deleted once the study was over, as promised to the subjects.

Measures

The survey was conducted in both Arabic and English because most respondents did not speak the language well. Back-translation was done in order to verify that the English and Arabic versions of the questionnaire were consistent.

Command-and-control

Command-and-control variable was measured using an eight-item scale developed by Tyler et. Al. (2005). The scale includes two components. The first component includes four items that measure respondent expectations about whether rule breaking, or rule following would be detected (e. g. how easy is it for your supervisor to observe whether you follow work rules). Ratings were made on a five-point scale with a high score indicating a high possibility for detection.

The second component of the scale include four items reflect the anticipated reaction (rewards and punishment) to detected rule breaking or rule following behavior (e. g. if you are caught breaking a work rule, how much does it hurt your pay or chances for promotion). Ratings were made on a five-point scale with high score indicating expecting more severe punishment. The Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for this scale was 0.85.

Adherence to rules

Adherence to rules was measured using a four-item scale developed by Tyler and Blader (2005). The scale measures compliance with organizational policy (e.g., how often do you follow the policies established by your supervisor). Participants were asked to respond using a six-point scale (1) never to (6) very often. The Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for this scale was 0.89.

Trust in Organization (OT)

Organizational trust was measured using five-items from the organizational trust scale developed by Tan and Lim (2009) and Gillespie (2003). Illustrative items are: “I would be comfortable allowing the organization to make decisions that directly impact me, even in my absence”; “I am willing to rely on the organization to represent my work accurately to others”. Ratings were made on a five-point Likert type scale that ranged from 1 (“Strongly disagree) to 5 (“strongly agree”). The Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for this three-item scale was 0.77.

Procedural justice.

A four-item scale developed by D. McFarlin, and P. Sweeney (1992) was used to measure procedural justice (items 31-34 in Table 3). Respondents indicated the extent to which the general procedures used to communicate performance feedback, determine pay increases, and evaluate performance and promotability were fair. The Cronbach coefficient alpha for this six-item scale was .76.

Analysis and Results

Descriptive statistics, reliability tests, rotated factor analysis, multiple response test, non-parametric tests, correlation analysis, and regression analysis were used to analyze the data in this study. The range of possible values, means, and standard deviations of the variables analyzed in this paper are reported in Table 2.

Non-parametric tests were performed to examine significant differences in responses within these categories in order to assess the response's sensitivity to changes in demographic parameters. Three demographic characteristics—gender, nation, and age—were specifically tested for because of their general propensity to inflate or suppress the specific outcome variables employed in this study (Staines, Pottick, and Fudge 1986). Results demonstrate how procedural justice is distributed differently for different age and gender groups. Nevertheless, the findings, which are presented in Tables 3, demonstrate that organizational trust, rule adherence, and command and control are insensitive to variations in age, gender, or nationality.

Measures of correlations were calculated and assessed for significance in order to examine the degree of relationship between various research variables. For each research variable, Table 4 displays correlations and reliability coefficients when appropriate. The findings show a substantial correlation between procedural justice, organizational trust, and rule adherence and command and control.

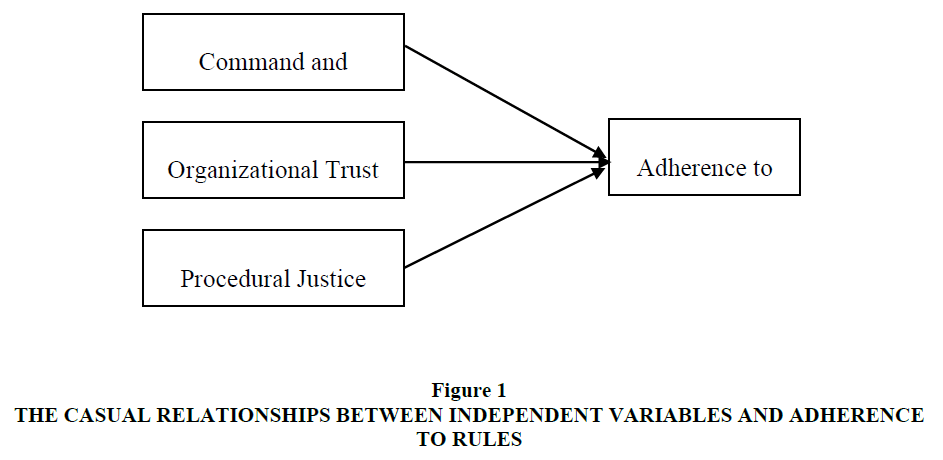

Hypotheses were tested using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and path analysis. AMOS computer software was used to perform structural equation analysis. Data was fitted against several competitor models. The most reasonable model provided GFI (goodness of fit index) = .90 and RMR (root mean square residual) = 0.04 which are considered appropriate to accept the adequacy of the model. Figure 1 illustrates the direct relationships between command and control, organizational trust, procedural justice, and adherence to rules. Results of path analysis presented in Table 4 indicate that command and control is positively related to adherence to rules (P = 0.00), confirming hypothesis number 1. Furthermore, results in table 5 show that organizational trust and Organizational justice are also positively related to adherence to adherence to rules (P = 0.00) confirming hypotheses 2, and 4. It would be interesting to investigate the above relationships in the presence of commitment as a moderator as shown in Figure 2.

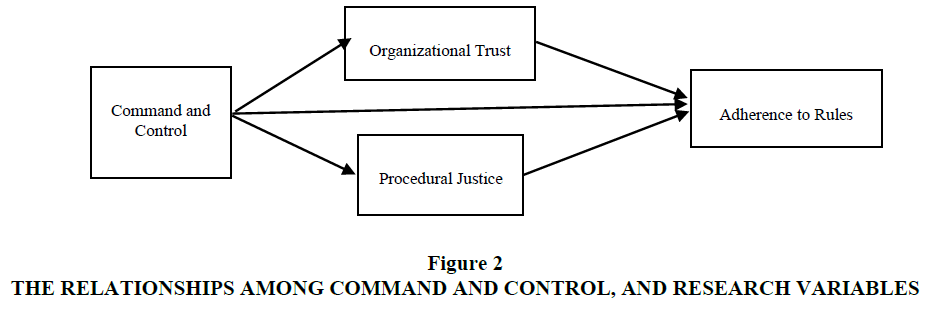

Figure 2 illustrates the model when organizational trust and organizational justice were included in the structural equation modeling as moderators. The fitted model provided GFI = .93 and RMR=0.07 which are considered appropriate to accept the adequacy of the model. Results of path analysis presented in Table 6 indicate a significant positive direct effect of command and control on work outcomes as follows: adherence to rules (P = 0.00), organizational trust (P = 0.00), and organizational justice (P = 0.00). Furthermore, results in Table 6 shows significant positive direct effect of organizational trust on adherence to rules (P= 0.00) and a direct positive effect of organizational justice on Adherence to rules (P = 0.00).

Results in Table 7 show the direct and indirect effects of command and control and adherence to rules. The direct paths from command and control to adherence to rule, organizational trust, and organizational justice statistically insignificant (p-values > 0.05). However, the relationship between command and control and adherence to rules become strongly significant via the moderating variables organizational trust and organizational justice. When the moderators are inserted in the model, the path coefficient of command and control on adherence to rules increase from 0.46 to 0.68 (p-values > 0.05).

Table 8 provides summary statistics regarding the total effect of command and control on adherence to rules in the absence of two moderating variables and when the moderators are present.

Table 8 clearly signifies the role of organizational trust and organizational in moderating the relationship between command and control and adherence to rules. Th two moderating variables tend to significantly increase the effect of command and control on adherence to rules. The combined results in Tables 6 and 7 provide support for the moderating role of organizational trust and organizational justice in the relationships between command and control and adherence to rules, and thus validate research hypotheses 3, and 5.

Discussion

The present study establishes a specific model for rule following behavior which includes new variables to explain why employees adhere to organizational rules and policies. Drawing upon the literature of organizational trust, we suggest that employees’ ethical values will be turned on in decision making when employees perceive their organization as being trustworthy. Furthermore, we contend that workers' perceptions of their fair and equitable workplaces encourage them to follow rules and take on the responsibilities that the organization assigns them. Future research should empirically examine the model suggested in this paper to determine its validity.

This study demonstrates that procedural justice, organizational trust, and command and control techniques have a direct impact on rule adherence among employees in Kuwaiti corporate organizations, based on a sample of those workers. According to the tested model, employees follow organizational rules and policies because they believe in the existence procedural justice and organizational trust.

Employees’ willingness to assume a risk and relinquish control in the hope of receiving a desired benefit from their organizations contributes to their adherence to rules. Furthermore, employees’ perception of fairness of organizational rules and procedures leads to the development of social exchange relationships between employees and their organization (Organ, 1988). Based on the norm of reciprocity (Gouldener, 1960), when employees perceive that their organization is treating them fairly, social exchange relationship dictate that employees reciprocate, and adherence to organizational rules and policies is one likely avenue for employee reciprocation.

The findings outlined above confirm the findings of Tyler and Blader (2005) that using fair procedures within an organization enhances rule following behavior. Other antecedents of adherence to rules include ethical values, social value judgments command-and-control mechanisms and contingent rewards (Zhu et. Al. 2023, & Tyler & Blader, 2005). Furthermore, research findings indicate that the direct and interactive influences of the costs and benefits that employees perceive in alternative compliant and non-compliant behaviors play a key role in their rule following behavior (Khatib, & Barki, 2022).Organizational trust was also found to be an antecedent to compliance behavior, as organizational trust increase, employee deviant behavior decline (Abbasi, Wan, &Wan, 2023)

Theoretical and Managerial Implications:

Our research has several significant theoretical and practical ramifications.

The findings reveal new factors that determine employee adherence to company rules. Our research results support the role of command-and-control methods as antecedents to adherence to rules. Other antecedents to adherence to rules include self-regulatory strategies, which are based on individuals’ intrinsic motivation to abide by organizational rules and procedures. A comparison between the two approaches to rules following behavior showed that the self-regulatory approach to have stronger effect on employees’ rule following behavior (Tyler & Balader, 2005).

Furthermore, our findings indicate that the effect of command and control on rule following behavior is conditioned by organizational trust and procedural justice. The effect of command and control on adherence to rules becomes stronger as employees’ trust in the organization increases. Similarly, perceptions of procedural justice have a positive effect in the relationships between command and control and adherence to rules.

The practical consequences of this study include the need for companies that want to promote rule compliance to make sure that their procedures and policies support staff members' perceptions of procedural justice and organizational trust. Also, implementing measurement techniques which provide insight into trust in the organization, such as Trust Index (Shockley-Zalabak, Ellis, and Cesaria, 2003), focus groups, and organizational climate questionnaires.

Limitations and future research

There are certain limitations to the current investigation. First off, any interpretation of causality between the variables is precluded by the study's cross-sectional research design. The model proposed in this study is supported both theoretically and empirically, but other possible reasons for the results cannot be ruled out. I propose using longitudinal research designs in future studies investigating the determinants of adherence to regulations.

In a longitudinal study it may be possible to observe over time the effect of independent variables on adherence to rules. This type of research design will make it possible to unambiguously determine the causal effect of independent variables on adherence to rules. Second, the use of self-reported data, in testing the model, suggests that the reported results could possibly be influenced by method variance, necessitating the deployment of controls for various potential biasing effects.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to the research department at Kuwait University for financially supporting this study under the code number IM05/18

References

Abd Ghani, N. A., & Hussin, T. A. B. S. R. (2009). Antecedents of Perceived Organizational Support/ANTÉCÉDENT DE LA PERCEPTION DE SOUTIEN ORGANISATIONNEL. Canadian Social Science, 5(6), 121.

Carton, J. S. (1996). The differential effects of tangible rewards and praise on intrinsic motivation: A comparison of cognitive evaluation theory and operant theory. The Behavior Analyst, 19, 237-255.

Dulebohn, J. H., & Ferris, G. R. (1999). The role of influence tactics in perceptions of performance evaluations’ fairness. Academy of Management journal, 42(3), 288-303.

Gillespie, N. (2003). Measuring trust in working relationships: The behavioral trust inventory. Melbourne Business School.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American sociological review, 161-178.

Greenberg, J. (1990). Organizational justice: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Journal of management, 16(2), 399-432.

Kaneshiro, P. (2008). Analyzing the organizational justice, trust, and commitment relationship in a public organization. ProQuest.

Konovsky, M. A., & Pugh, S. D. (1994). Citizenship behavior and social exchange. Academy of management journal, 37(3), 656-669.

Krosgaard, M. A., Brodt, S. E., & Whitener, E. M. (2002). Trust in the face of conflict: The role of managerial trustworthy behavior and organizational context. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 312.

Leventhal, G. S. (1980). Beyond fairness: A theory of allocation preferences. Justice and social interaction, 3(1), 167.

Li, X., Wang, C., & Hamari, J. (2021). Frontline employees’ compliance with fuzzy requests: A request–appraisal–behavior perspective. Journal of Business Research, 131, 55-68.

Lind, E. A., & Earley, P. C. (1991). Some thoughts on self and group interests: A parallel-processor model. In annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Miami.

Lind, E. A., Kanfer, R., & Earley, P. C. (1990). Voice, control, and procedural justice: Instrumental and noninstrumental concerns in fairness judgments. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 59(5), 952.

Lind, E. A., Kulik, C. T., Ambrose, M., & de Vera Park, M. V. (1993). Individual and corporate dispute resolution: Using procedural fairness as a decision heuristic. Administrative science quarterly, 224-251.

Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. Springer Science & Business Media.

Luhmann, N., Burns, T., & Poggi, G. (1979). Trust and Power New York: Wiley.

McFarlin, D. B., & Sweeney, P. D. (1992). Distributive and procedural justice as predictors of satisfaction with personal and organizational outcomes. Academy of management Journal, 35(3), 626-637.

McKnight, D. H., Cummings, L. L., & Chervany, N. L. (1998). Initial trust formation in new organizational relationships. Academy of Management review, 23(3), 473-490.

O'Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior. Journal of applied psychology, 71(3), 492.

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington books/DC heath and com.

Organ, D. W., & Moorman, R. H. (1993). Fairness and organizational citizenship behavior: What are the connections?. Social Justice Research, 6, 5-18.

Pearce, J. L., Branyiczki, I., & Bakacsi, G. (1994). Person-based reward systems: A theory of organizational reward practices in reform-communist organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(3), 261-282.

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative science quarterly, 224-253.

Shockley-Zalabak, P., Ellis, K., & Winograd, G. (2000). Organizational trust: What it means, why it matters. Organization Development Journal, 18(4), 35.

Tan, H. H., & Lim, A. K. (2009). Trust in coworkers and trust in organizations. The Journal of Psychology, 143(1), 45-66.

Thibaut, J., & Walker, L. (1975). Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis. Hilsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2005). Can businesses effectively regulate employee conduct? The antecedents of rule following in work settings. Academy of management journal, 48(6), 1143-1158.

Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 115-191). Academic Press.

Vardi, Y., & Weitz, E. (2003). Misbehavior in organizations: Theory, research, and management. Psychology Press.

Zhu, N., Liu, Y., Zhang, J., & Wang, N. (2023). Contingent reward versus punishment and compliance behavior: the mediating role of affective attitude and the moderating role of operational capabilities of artificial intelligence. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 1-11.

Received: 28-Apr-2023, Manuscript No. IJE-24-14929; Editor assigned: 01-May-2024, Pre QC No. IJE-24-14929 (PQ); Reviewed: 15-May-2024, QC No. IJE-24-14929; Revised: 20-May-2024, Manuscript No. IJE-24-14929 (R); Published: 27-May-2024