Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 1

Coaching History: The Evolution of a Profession

Andriana Eliadis, Cornell University

Citation Information: Eliadis, A. (2023). Coaching History: The Evolution of a Profession. Journal of Organizational Culture Communications and Conflict, 27(S1), 1-18.

Abstract

Professional coaching and leadership coaching are emerging as two important parallel research streams in organizational settings. The existing research on two domains indicates many complex and mixed definitions, concepts, and applications, and a gap in practice and literature, which are confounding the researchers from exploring the new factors influencing these two concepts and their consequences. The research aims to conduct a chronological literature survey from the origins of concepts to the current state to examine the evolution of professional coaching and leadership coaching and how professional coaching facilities the implications of leadership coaching. The results suggest that these two fields are relevant and professional coaching development facilitates the growth of leadership coaching. The research also highlights the numerous benefits of leadership coaching for effective organizational culture, climate, and performance outcomes. Moreover, it highlighted that leadership coaching has the potential to increase employee performance, motivation, and commitment to work and make the environment more creative and open for learning. Therefore, this research recommends exploring it with different models and variables in diverse business sectors.

Keywords

Coaching, Coaching History, Leadership, Leadership Coaching.

Introduction

Coaching can be described as the process of facilitating self-determined and self-directed problem solving or change within the context of a helping conversation. As coaching has gained momentum as a tool in organizational training and development, its practitioners began forming communities to share experiences and further formalize, define, and hone this approach among themselves. Resultantly, professional coaching organizations appeared to offer peer-reviewed credentialing processes, most of which demand that the individual coaches continuously expand their coach training and hone their skill set (Hicks, 2013). In addition, each organization expects its member coaches to abide by a code of ethical conduct as a commitment to professional standards that support respect, responsibility, and integrity in their delivery of services. Common to professional standards across the global community of coaching associations are expecting that each coach will combine training and skillset with similar behaviors, qualities, and attitudes (English, 2019).

Leadership is a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal. Leadership is not a trait or characteristic that resides in the leader, but rather a transactional event that occurs between the leader and the followers. Whereas leadership coaching is important for effective leadership as it is one mode of leadership operations that involves active listening, being empathic and nonjudgmental, and driving people forward. The existing literature on coaching in the context of training and development has been published in the last few decades, but the intellectual underpinnings of the concept evolve in the 15th century (van Nieuwerburgh et al., 2018). Thus, the field of coaching is not new as it has evolved over a long time to offer many useful and important insights on the role of coaching in the development of some new concepts like professional coaching and leadership coaching. In this review, the author took an evolutionary and theme based perspective to explain the development of coaching into professional and leadership coaching. The study is mainly divided into two stages, in the first stage a review of professional coaching is presented with a few key themes: (1) History of coaching; (2) Emergence of professional coaching; (3) Current knowledge about professional coaching; (4) Professional associations; (5) Professional coaching niches and specializations and the second stage presents the overview of managerial and leadership coaching discussing the key themes like (1) Early leadership studies, Approaches, and Theories integrating human elements; (2) History of managerial and leadership coaching; (3) Current knowledge about leadership coaching from the perspective of leadership and managerial literature; (4) Coaching as leadership style; (5) Coaching and coaching training in workplace; (6) Critiques of managerial and leadership coaching (7) How coaching can enable leadership development. This division depicts the chronological evolution of the field, key trends, and directions of investigation on the subject. The particular focus of this research is to explore the empathic zone as these leaders tune into the feelings of their people. Moreover, it examines the role that empathic leadership plays in developing successful leadership capacities. The articles with a significant contribution to the evolution of the field were included in the review and focused to find the traces of coaching to its current stage and how it will further evolve in the future. The article contributes to the literature as it presents the up-to-date literature on professional coaching and leadership coaching, it offers a more comprehensive viewpoint by integrating key areas related concepts to professional and leadership coaching, and it also highlights key promising research areas that require attention for future research. Lastly, the research also expands the understanding of the current position of coaching literature and highlights its key limitations.

Literature Review

This section will first review the brief history and emergence of coaching as a profession. Professional coaching places coaching as an ultramodern profession that is monitored via evidence-based practices, academic research, ethics and standards, credentials, and coach accreditation processes. Secondly, it will discuss the evolution of managerial and leadership coaching as empathic leadership, the emphasis will be on the leader and/or manager leading via a coaching approach.

The History of Coaching

The word “coach” is originated from a town in Hungary, Koc, pronounced “kotch,” where they used to build carriages in the 15th century. The first use of the word “coach” seems to be in an academic setting at the University of Oxford in the 1830s (Online Etymology Dictionary, 2020; Nieuwerburgh, et al., 2018). In this case, the “coach” was used to refer to a tutor who supported students with their academic work. It was initially used informally, suggesting that a tutor would take a student from point A to point B-much like a coach (or carriage), which would similarly take individuals from point A to point B (Online Etymology Dictionary, 2020; Nieuwerburgh, et al., 2018).

Coaching, as a method for creating purposeful, positive change, is now an established part of the corporate landscape. It is increasingly used in many different industries and is taught at universities worldwide. Once seen as little more than a fad, the development of evidencebased approaches to coaching and the emergence of coaching-specific peer-reviewed academic literature have made coaching mainstream and are a testament to its growing professionalization (Brock, 2014).

The Emergence of Professional Coaching

Initially the concept of Professional coaching has appeared over the decades by the extensive efforts of coaching companies, effective in their professions (Brock, 2008). Table 1 displays the six earliest professional coaching programs, the founding year of each program, the coaching company name, the company website, and a brief description of each coaching company.

| Table 1 The Six Earliest Coaching Companies |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year Founded | Company Name | Website | Description |

| 1986 | New Ventures West (NVW) | www.newventureswest.com | Created in 1986 by James and Stacy Flaherty, New Ventures West is in San Francisco, California. This program supplies an integral Coaching curriculum emphasizing didactic and experiential methods that focus on self-awareness and competence building and is based on a strong theoretical foundation (Flaherty, 2006). |

| 1987 | Success Unlimited Network (SUN) | www.successunlimitednet.com | Success Unlimited Network 1987 owned by Teri-E Belf in US, the current program is based on several traditions, including sports psychology, management theory, NLP, the Inner Game, integrative learning, and accelerated learning. |

| 1990 | Newfield Network | www.newfieldnetwork.com | Founded in 1990 in California by Julio Olalla and Rafael Echeverria. It provided training grounded in the philosophical traditions of the biology of cognition, the philosophy and ontology of language, and body movement studies. |

| 1992 | Coach U (CU) | www.coachu.com | CU was created by Thomas Leonard’s College for Life Planning, which he formed in 1988 at the age of 33 when he left his job in the accounting department of Werner Erhard and Associates (WEA). CU was officially started in September 1992 (Brock, 2014). |

| 1992 | The Coaches Training Institute (CTI) | www.thecoaches.com | CTI was founded by Laura Whitworth and Henry and Karen Kimsey-House. Each of the founders’ backgrounds (finance, acting, and business respectively) influenced the experiential and expressive nature of the curriculum. Karen Kimsey-House described the CTI philosophy and experience as intimate, tribal, and evolutionary. |

| 1986 | Hudson Institute | www.hudsoninstitute.com | The Hudson Institute of Santa Barbara was the only coach training program that derived came from the developmental/empirical paradigm. It was founded by two developmental psychologists. |

In 1986, Hudson, and McLean founded the Hudson Institute, mentoring was their first approach to support their clients. They applied their method to several academic disciplines, such as adult development, humanistic psychology and philosophy, adult learning, human and organizational systems thinking, and transformational change theory. This academic knowledge was practiced at the Fielding Graduate Institute, of which Frederic Hudson was the founding president from 1973 to 1986 (McLean, 2006). Under Hudson’s leadership, Fielding’s mission was to offer graduate degrees to adults who were in their mid-careers through a novel selfdirected learning model. Many of earlier influencers and thought leaders who formed the curriculum and foundational approach at Hudson and Fielding were Malcolm Knowles, father of adult learning; Robert Tannenbaum, Edgar Schien, and Richard Beckhard from Organizational Development domains; Marjorie Lowenthal Fiske, well-known developmentalist and researcher on intentionality; Fred Jacobs, founder of Leslie College and innovator in adult learning; Robert Goulding, MD, founder of Redecision psychotherapy; and Vivian McCoy, Carol Gilligan, Daniel Levinson, along with many earlier theorists and researchers, including Robert Kegan, Jean Piaget, and Abraham Maslow (Brock, 2014). These primary theoretical roots of adult development and learning, human systems thinking, and change theory that shaped the basis of the Hudson Institute programs were proved well before the field of coaching emerged (Brock, 2014).

By 2006, there were more than 275 English-language coaching schools, including academic institutions like Fielding Graduate Institute, the University of Texas at Dallas, and Georgetown University; the private training schools of Adler School of Professional Coaching, Institute for Life Coach Training (ILCT), and Success Unlimited Network (SUN); and the international schools of the Academy of Executive Coaching in the United Kingdom, Coach 21 in Japan, Results Coaching in Australia, and Institut de Coaching in Switzerland (Brock, 2014).

Current Knowledge about Professional Coaching

Interest in coaching has skyrocketed over the last two decades, with hundreds of training organizations delivering coaching programs. These range from one-day short courses, online courses, week-long certificated programs, and postgraduate-level courses and degrees. Coaching is used in professional contexts in many of the world’s leading economies (Ridler Report, 2016; Sherpa Executive Coaching Survey, 2015). However, a discipline’s movement toward professionalization is confirmed by the materialization of professional associations along with the development of professional literature and graduate study. This section traces the origin and growth of the first professional associations in coaching.

Professional Associations

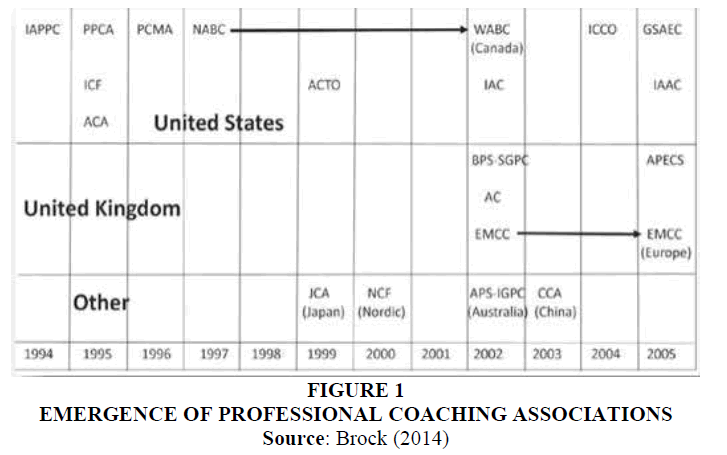

Coaching is now a profession, with the emergence of several professional associations, for example, the first professional coaching association was formed in 1992 by Thomas Leonardthe National Association of Professional Coaches (NAPC). Figure 1 is a visual representation of the holistic history of the evolution of professional coaching associations in the United States (US) and internationally from 1994 until 2005.

As Figure 1 portrays, another early initiative was the New York Coaching Alliance in 1994, which was an informal community for coaches in New York. In 1993, the International Association of Professional and Personal Coaches (IAPPC) was founded. IAPPC was a full professional association with regulations, a Board of Directors, and accountability. IAPPC held monthly meetings, and membership was extended to professional members and associate members. It also had a hard-copy newsletter entitled The Coaches Agenda. In 1995, IAPPC became PPCA.

During a Coach University board meeting in 1995, Thomas Leonard announced the launch of the International Coach Federation (ICF), which he branched out of CU. Then in 1997, PPCA was dissolved, and ICF invited the former PPCA members to become members of ICF. When ICF was founded in 1995, its objective was to give credibility to the emerging profession of coaching and provide a place for coaches to connect with one another. Twenty-six years later, ICF has become the world’s largest organization of professionally trained coaches.

In 2020 the International Coach Federation became the International Coaching Federation as “a new way of serving coaches, coaching clients, our communities and the world, as we pursue our vision of coaching as an integral part of a thriving society” (ICF, n.d.-b, para. 2). In 2021 ICF created a new brand and the ICF ecosystem, which reflects ICF’s attention to many arenas of the coaching industry. These are represented by six family organizations that make up ICF as one entity including Professional Coaches, Credentials and Standards, Coach Training, Foundation, Coaching in Organizations, and Thought Leadership Institute.

In addition to ICF, two more early organizations, which are still in the forefront of the international professional coaching association sphere, were the European Mentoring and Coaching Council (EMCC) and the Worldwide Association of Business Coaches (WABC). EMCC was founded in 1992 as EMC (the European Mentoring Centre) by David Megginson and David Clutter buck. In 2002, EMC’s focus was revised to include coaching, and its name was rebranded to European Mentoring and Coaching Council (EMCC). From the beginning of its formation, the principle of inclusivity was important. Thus, anyone could join EMCC, if they agreed to abide by the Code of Ethics. As of December 31, 2018, EMCC has 24 affiliated countries in Belgium, Cyprus, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Spain, Switzerland, Serbia, Turkey, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom, plus the Asia Pacific Region (EMCC, n.d., para. 7).

WABC was originally founded 1997 as the National Association of Business Coaches (NABC) by Steve Lanning and Hal Wright of the United States. In 2002, Wendy Johnson transformed NABC into a new privately held federal corporation in Canada, and it became WABC Coaches Inc. WABC Coaches Inc. conducts business as the Worldwide Association of Business Coaches (WABC) and serves and develops business coaching markets around the world. Table 2 presents the competency and credentialing models of these three professional coaching associations.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

As the profession continues to grow, coaching consistently reveals itself as a dynamic, evolving process of pursuing human behavioral changes and attaining goals that defy definition and resist containment. Within this process, effective coaching is masterful facilitation (English, 2019), which serves individuals in moving from where they are to where they want to be-coming full circle back to the origins of the word “coach.” May the journey ahead be filled with awe, revelation, and wonder?

Professional Coaching Niches and Specializations

The current discipline of coaching has branched out into a varied array of niches and specialties. For example, there are business, personal, and life-related specialties. The life specialties concern issues outside the professional space, i.e., quality of life, relationships, personal identity, and change. Personal coaching specialties can be divided into five main subgroups:

1. Life, purpose, vision, lifestyle design, motivation, creativity, integrity, authenticity, clarity.

2. Relationship, family, parenting, teens/children, gay/lesbian, sexuality.

3. Transitions, divorce, retirement.

4. ADHD, wellness, self-care, addictions; and 5. Spiritual, Christian (Brock, 2014)

The business space specialties are categorized by the clientele, the client’s role, the situation being coached, and the focus of the coaching (Brock, 2014). The three main subgroups within the category are:

1. Business, entrepreneur, organization, and team, professional, practice building, sales, cross-cultural diversity.

2. Leadership, executive, and management; and 3. Career transitions, planning, and development (Brock, 2014)

At this point, it is important to distinguish between a professional coach, who has a specialty in management and/or leadership coaching and an organizational leader or manager who leads via a coaching approach mode. A professional coach who has a specialty in management and/or leadership coaching is a professional coach, usually external to the organization, who facilitates a manager’s or leader’s management and leadership goals and aspirations. An organizational leader or manager who leads via a coaching approach mode is an employee of the entailed company who manages and/or leads his/her people through a coaching model in which he/she facilitates problem-solving, encourages employees’ development via inquiry, and offers support and guidance instead of being directive and making judgments (Ibarra & Scoular, 2019).

In the next section, managerial and leadership coaching as empathic leadership has been discussed, the emphasis will be on the leader and/or manager leading via a coaching approach.

Managerial and Leadership Coaching

In the past 60 years, leadership has been in the center of debate concerning its definition and classification. These definitions and classifications have been influenced by numerous elements such as world affairs, politics, and scholars’ and practitioners’ perspectives and experiences. This section presents a discussion of early leadership approaches and theories, which have crafted the path to managerial and leadership coaching as well as the approach and interconnection to empathic leadership.

Early Leadership Studies, Approaches, and Theories Integrating Human Elements

Over 200 definitions and 65 classification systems have been developed to describe the components and dimensions of leadership (Fleishman et al., 1991; Northouse, 2018). Moreover, Table 3 shows six distinct emotional leadership styles; each style has a different effect on people’s emotions, and each has strengths and weaknesses in different situations.

| Table 3 Six Emotional Leadership Styles |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Leadership Style | Resonance | Impact on Climate | When Appropriate |

| VISIONARY | Moves people toward shared dreams | Strongly positive | When changes require a new vision, or when a clear direction is needed |

| COACHING | Connects what a person wants with the organization’s goals | Highly positive | To help an employee improve performance by building long-term capabilities |

| AFFILIATIVE | Creates harmony by connecting people to each other | Positive | To build buy-in or consensus, or to get valuable input from employees |

| DEMOCRATIC | Values people’s input and gets commitment through participation | Positive | To build buy-in or consensus, or to get valuable input from employees |

| PACESETTING | Meets challenging and exciting goals | Because too often poorly executed, often highly negative | To get high-quality results from a motivated and competent team |

| COMMANDING | Soothes fears by giving clear direction in an emergency | Because so often misused, highly negative | In a crisis, to kick-start a turnaround, or with problem employees |

| Note: Adapted from Goleman et al. (2013) | |||

Four of these styles-visionary, coaching, affiliated, and democratic-promote harmony, produce positive outcomes, and boost performance, while the two other styles-commanding and pacesetting-can create tension and should only be used in specific situations (Goleman et al., 2013). According to Goleman et al. (2013), the coaching leadership style emphasizes personal development rather than merely completing transactional tasks and generally anticipates an “outstandingly positive emotional response and better results” (Loc. 1557), almost regardless of other styles a leader may employ. By employing dialogues, leaders have personal conversations with employees; hence, coaching leaders set up rapport and trust. They show a genuine interest in their people rather than seeing them as employees to simply get the job done. Coaching thereby produces ongoing communication, allowing employees to listen to performance feedback developmentally and positively as well as see it as serving their own ambitions, not just their manager’s interests. Goleman et al. (2013), asserted that although there is a commonly held belief that every leader should be a good coach, not all leaders exhibit this style as they feel that they do not have time for it, especially in high-pressure and tense times. However, by not applying this style, they “pass up a powerful tool”.

History of Managerial and Leadership Coaching

Although the role of coaching has changed over time, some paradigms of research papers on managerial, supervisory, and business coaching show that between the late 1930s and the late 1960s, some forms of internal managerial coaching already existed, i.e., managers or supervisors acting as coaches to their people. During those times, coaching in the workplace focused merely on managers supporting followers with responsibilities and developing productivity as part of managerial functioning; these practices were later considered to be managerial coaching (Maltbia et al., 2014). Table-4 illustrates peer-reviewed coaching articles that have been tracked to date from 1937.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The first peer-reviewed article found was Gorby (1937) paper, which was published on workplace coaching. The author used the terms training and coaching interchangeably. The paper described how training and coaching have contributed to improved performance in a manufacturing environment (Grant, 2011; Maltbia et al., 2014). Lewis (1947) discussed supervisory training methods through example, and next in importance comes “coaching on-thejob”. Lewis argued that coaching on the job should constitute about 80% or more of all the training that takes place in the organization. He said it is timely and meets the specific needs of the employee. It presents a “near perfect learning situation”. At times in its history, the business world has been particularly attracted to exploring how to improve human performance through psychology (Whitmore, 2010). Between the 1940s and 1960s, some organizations provided their senior executives with counseling, delivered by occupational or organizational psychologists. These interventions were designed to support executives and leaders to overcome hurdles, develop themselves, and thus increase the quality and profitability of their organization (Wildflower, 2013).

As seen in Table 4 in the 1950s, following Lewis (1947) article, there were nine additional studies, and coaching was introduced as a management skill (Maltbia et al., 2014). In the 1960s and 1970s, there were six studies in total (Grant, 2011), but it was not until the 1980s that the first signs of progression were evident (Passmore & Fillery-Travis, 2011). During the 1980s, there were 19 peer-reviewed articles (Grant, 2011) which were more than double the number of articles written between 1960 and 1979. Several of these initial articles revealed the potential that coaching may have as an organizational intervention or as a complementary intervention to help with employee learning and leadership development training.

Gallwey (2014) introduced the concept of the “inner game.” of a player (psychological attitude) was as important as the “external game” (physical skill and competencies). This theory was embraced by the business community in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. Later, Alexander and Whitmore developed the concept into the well-known GROW model that is now taught in most coach training programs. Following Whitmore’s book Coaching for Performance in 1992, executive coaching started to flourish in the UK in the final years of the 20th century and has gained steady momentum since then.

The application of coaching as a concept and set of techniques to the art and practice of management grew rapidly through the 1980s and 1990s (Kilburg 2007). Krausz (1986) examined the relationship between different types of power and leadership styles in organizations and the effect that these types of power and leadership styles have on the culture, climate, and results of an organization. Two sources of power are considered-the organization and the individual-and six types of power are studied: coercion, position, reward, support, knowledge, and interpersonal competence. The author also considered four derivative leadership styles: coercive, controlling, participative, and coaching.

Most of the formal research being published on coaching in management came in the form of graduate dissertations; between 1980 and 1999, there were eight graduate dissertations, 33 journal articles, and several books about executive coaching. Also, Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research (Kilburg 1996) dedicated an entire issue to executive coaching (Kampa-Kokesch & Anderson, 2001; Kilburg, 1996; Maltbia et al., 2014). By far, the largest body of literature available consisted of articles devoted to urging managers to exert themselves to add coaching to their roles to empower subordinates, solve organizational problems, and push their enterprises towards peak performance (Kilburg 2007). This expediential attention of coaching in the academic literature coined the term “executive coaching” as a distinct intervention (Grant, 2011; Kampa-Kokesch & Anderson, 2001). A decade after Krausz (1986) study, Kilburg (2007) created a working definition for executive coaching; he said that:

Executive coaching is defined as a helping relationship formed between a client who has managerial authority and responsibility in an organization and a consultant who uses a wide variety of behavioral techniques and methods to help the client achieve a mutually identified set of goals to improve his or her professional performance and personal satisfaction and, consequently, to improve the effectiveness of the client's organization within a formally defined coaching agreement.

Executive coaching takes place in an organization between a “client”- an employee and his/her manager. All the literature, and Kilburg (2007) definition above, provided viewpoints, guidance, reinforcement, and warnings that firmly suggested that the manager/executive who did not know how to coach effectively would endure poor organizational performance and restricted career opportunities. The history of leadership, management, and executive coaching created a strong foundation for the current knowledge and application of leadership coaching in organizations worldwide.

Current Knowledge about Leadership Coaching from the Perspective of Leadership and Managerial Literature:

Coaching is currently being used to support students, business leaders, patients, health professionals, future leaders, senior executives-in fact, anyone who wishes to achieve more of their potential (Whitmore, 2010; Wildflower, 2013). Today, leadership coaching is firmly embedded in many Western cultures. It is frequently used in educational settings and is prevalent in many professional contexts (van Nieuwerburgh et al., 2018). Leadership and managerial coaching are viewed as an individualized practice of personal and professional development. While transactional skills are taught through traditional training methods, it is believed that more sophisticated professional development for leaders and executives can be provided through oneto- one coaching. It is seen as “timely, on-the-job professional development” (van Nieuwerburgh et al., 2018).

Coaching as a leadership style: Leadership coaching is on-the-job development and requires that a leader connects at the human level, beyond the task-thus, “being before doing” (Whitmore, 2017)-and stop thinking that the leader is the expert who tells everybody else what to do. Coaching is based on trust, belief, and non-judgment. Judgment and criticism put people in the defense mode. Fear of judgment and/or blame is a major inhibitor to collaboration, communication, and peak performance. Leadership coaching creates a culture where enjoyment is fundamental to learning, “mistakes” are seen as “learning opportunities,” and collaboration is the ultimate enabler. Whitmore (2017) claimed that if leaders manage by the principles of coaching, they get the job done at a greater standard and, concurrently, they develop their people.

Hicks & McCracken (2011) stated that “Coaching and leadership are two sides of the same coin”. People usually do not want to be managed, but they want guidance (Hicks, 2014). When employees have a drive for professional excellence and success, actionable feedback for professional improvement is necessary. Hence, developmental discussions and mentor relationships are highly appreciated, especially by young professionals, since young professionals tend to focus more on the technical side of their job at the expense of the behavioral essentials. Thus, help from leaders and more experienced colleagues is frequently needed to cope with the social and political problems that unescapably arise in team-based, task-interdependent work environments (Hicks, 2014). So “Leadership and coaching go hand-inhand”. A good leader as a coach must be able to relate to people in a way that will help them solve problems and pursue their goals (Hicks, 2014). A leader that has a coaching leadership style approach will establish a collegiate style of communication that will develop relationships and facilitate persuasion and influence. The coaching approach leadership style and the competencies associated with the implementation of coaching as well as the behaviors associated with coaching can assist any leader in becoming more transformational (Hicks, 2014). In a VUCA (Volatile - Uncertain - Complex - Ambiguous) world, which is undergoing fundamental reforming, a style of leadership that is essential and transformational is a “coaching-like” approach. This will be beneficial to leaders as they attempt to gain cooperation and commitment in a demanding professional environment (Hicks, 2013).

Coaching and coaching training in the workplace: In recent years, coaching has been implemented extensively in the business world in various organizational industries, like the financial sector, pharmaceutical sector, medical sector, and other corporate segments with success (De Meuse et al., 2009; Huff et al., 2013; Wilson, 2004). Wilson (2004) focused on the benefits of coaching in the working environment and how the workplace is changing from an authoritarian style of leadership toward a more self-directed learning culture. He discussed the coaching culture the company Virgin adopted, as its founder, Richard Branson, was such a leader. The author discussed the benefits of coaching as well as the main principles that Branson adopted. Wilson (2004), examined how Branson acknowledged his people, created a blame-free working culture, and supported learning from each other and from the experiences they each had acquired. He also emphasized that coaching not only needs to be taught but also practiced becoming “unconscious”. He then described a case study where coaching was implemented and succeeded and, finally, took a dive into the ROI in the workplace with a coaching culture. He finalized the article by discussing the reasons companies introduce coaching and suggested further readings.

Gerbarg (2002) emphasized that organizations must invest in leadership coaching as one of the keys to sustainable success. Coaching is recognized as a major competency for organizational leadership (Boyce et al., 2010; Henochowicz & Hetherington, 2006). Also, coaching should be provided as part of a leadership program, focusing on leadership competencies where constructive feedback is also encouraged (Barriere et al., 2002; Henochowicz & Hetherington, 2006). Leadership coaching is a fundamental element of most organizations’ leadership development strategies (Boyce et al., 2010). Huff et al. (2013) discussed how effective feedback and coaching can help school principals improve their performance and, thus, the performance of their schools. Moreover, a meta-analysis on a study conducted by Smither et al. (2005) discovered that feedback along with coaching could have a positive impact on improving the leadership performance of principals.

Bilas & Adeeb (2018) discussed two types of mindsets: an outward mindset and an inward mindset and indicated that the outward mindset is crucial for “personal development and perfection”. This type of mindset is one of the most important factors of coaching leadership. A person with an outward mindset is open to collaboration when leading others. They also highlighted that it is critical that team members of an organization understand the importance of an outward mindset, and its adoption by each team member “contributes to the creation of innovative, self-learning, and cooperative teams and organizations”. The outward mindset coaching approach is the same for an individual, a team, and an organization. When an organization and its people have created such a mental approach, then they can achieve their planned or desired results, even in the process of radical change. Teams, which are built on the principle of outward mindset, are ready to work and support their leaders, their colleagues, and their organizations (Bilas & Adeeb, 2018).

Critique of Managerial and Leadership Coaching

Berg & Karlsen (2016) discussed that although coaching has a significant effect in the development and sustainability of organizations, especially during crises, it may not work well with all organizations and/or employees. Goleman et al. (2013) stated that coaching works best with employees who show initiative and want more professional development. Henceforth, coaching will fail when employees lack motivation or require excessive personal guidance and advice (Berg & Karlsen, 2016; Goleman et al., 2013)-or when the leader lacks the expertise and understanding required to coach the employee (Goleman, 2013). When executed inadequately, the coaching leadership style appears more like “micromanaging or excessive control of an employee” (Loc. 1174). Poor coaching leadership skills can demoralize an employee’s selfconfidence and eventually create a plunging performance spiral.

Goleman et al. (2013) claimed that many managers are not knowledgeable with or are merely unskilled at using the coaching leadership style, especially when they are giving ongoing performance feedback that should build motivation, not fear or apathy. Moreover, Cox et al. (2014); Hunt & Weintraub (2002) claimed that although managers may have a genuine intention to use coaching in their leadership schema, it is easy to fail. A key reason is that managers do not spend enough time with their people. Ellinger & Bostrom (2002); Hunt & Weintraub (2002) suggested that another barrier to coaching is a lack of communication and information about the goal and purpose-for example, about the expected effects of coaching. To succeed with coaching as a leadership style, managers and/or leaders must have a “coaching mindset” and confidence that they can accomplish the coaching leader role. They must also have specific skills and abilities to lead from a coach-like perspective. Ellinger & Bostrom (2002) also claimed that leaders who succeed with coaching as a leadership style have empathy for and trust others, are less controlling and directing, facilitate the development of their people, are open to feedback and learning, and believe that people are open to learning.

Hunt & Weintraub (2002) emphasized that leadership coaching can facilitate change and learning through incremental learning, not through a “sink-or-swim” attitude. “Most managers practice the sink-or-swim philosophy of people development: Give them a good assignment and, if they survive, promote them”. However, when a leader does not use coaching to help people make “sense of their experiences”, they are bound to learn wrongly or even fail, which will hurt their confidence and ultimately their developmental capacity. Subsequently, there is a distinct difference between coaching as a leadership style and management, as coaching as a leadership style encompasses helping employees flourish and progress; management is about directing and telling people what and how to do something (Ellinger & Bostrom, 2002). Leadership coaching is advocated to develop leadership skills in context by engaging individuals in authentic situations in which they experience the unique problems that occur settings. Coaching is both action?oriented and learning?oriented, focusing on the individual’s personal and professional goals and intrapersonal and interpersonal skills, such as self?management and interpersonal communication (McNamara et al., 2014).

Coaching Enabling Leadership Development

The concept of Transformative Learning (TL) lays the notion of leadership via coaching as leadership coaching lies within the egalitarian relationship between leader and follower, just as between educator and student in the TL process. Transformative learning via coaching changes the way of knowing via epistemological grounds and not merely just a behavior shift. “The epistemological shift includes the whole lifespan and is not limited to formal educational contexts” (Bennett & Campone, 2017). As personal transformation requires deep grounded changes in the way a person perceives, understands, and acts upon situations both cognitively and emotionally, TL theory and empathic leadership via coaching tools can support the employee in changing his/her taken-for-granted beliefs and making them more open, discriminating, and psychologically capable of change (Bennett & Campone, 2017). Thus, TL can be enabled through coaching. Coaching can develop leaders and their leadership capacities, and TL together through the adoption of its tools. Great leadership can find their genesis via inquiry, reflection, non-judgmental behavior, and active listening.

Discussion and Synthesis

To analyze the coaching literature, the study examined the published literature in chronological order. Based on the literature survey many important conceptual underpinnings were recognized like the coaching concept expanded to professional coaching and leadership coaching and how professional coaching facilities the evolution of leadership coaching over time. The coaching field was expanded to include the formulation of professional organizations and associations and examine their role in the development of the field. as well as strategy implementation.

The published research provides evidence for the existence of the earliest coaching companies like New Venture Vest (1986), Success unlimited Network (1987), Newfield Network (1990), Coach U (1992), The Coaches Training Institute (1992), Hudson Institute, (1986), the companies have contributed largely to coaching and developing the professionals to make them successful on their jobs. The researcher has incorporated several disciplines and study fields to design her methodology and curriculum for coaching, like adult development, humanistic psychology, philosophy, adult learning, human and organizations, system thinking, and transformational change theory. Many renowned researchers have contributed to the coaching foundations and growth and resultantly, by 2006, there were 275 English language coaching schools.

The interest in coaching has flourished over the previous three decades, as many new courses were introduced at different study levels. However, the professional coaching growth was confined due to the lack of coaching associations, and to cover this gap few associations were formed and become operative from the 1990s to 2010 such as the International Coaching Federation (ICF), European Mentoring and Coaching Council (EMCC), and the Worldwide Association of Business Coaches (WABC). The growth of coaching associations gives rise to research in the field of professional coaching.

Currently, the field of coaching is generally classified into different niches or specializations coaching, for example, life specialization concern issues outside the professional space, i.e., quality of life, relationships, personal identity, and change, personal coaching and life-related coaching specialties are subcategorized in five domains including life, purpose, vision, lifestyle design, motivation, creativity, integrity, authenticity, clarity; relationship, family, parenting, teens/children, gay/lesbian, sexuality; transitions, divorce, retirement; ADHD, wellness, self-care, addictions; and spiritual, Christian (Brock, 2014). The business place specialties of coaching are divided into categories such as business, entrepreneur, organization, and team, professional, practice building, sales, cross-cultural diversity; leadership, executive, and management; and career transitions, planning, and development (Brock, 2014). Such division of business coaching helps the literature to distinguish between the professional coach, who is specialized in management and leadership coaching, and the manager coach, who leads using a coaching approach. At this point, the study considers leadership coaching as an important branch of professional coaching that aims at developing future professional leaders by providing them with robust training and development to be effective in a diverse business environment.

The second part of this article highlights the role of leadership coaching particularly as an empathic leader. The vast survey of leadership literature over the past 60 years, highlights different definitions and classifications of leadership varying on different factors like world affairs, politics, and scholars’ and practitioners’ perspectives and experiences. The literature suggests over 200 definitions and 65 classification systems (Northouse, 2021). The literature also suggests the six emotional leadership styles, affecting the emotions of people differently including visionary, coaching, affiliative, democratic, pacesetting, and commanding. The findings suggest that four of these styles-visionary, coaching, affiliated, and democratic helps to promote harmony, produce positive outcomes, and boost performance, while the two other styles-commanding and pacesetting-can create tension and should only be used in specific situations (Goleman et al., 2013).

The research on leadership styles recommends that every leader should be a good coach irrespective of their specific leadership style because leaders using a leadership coaching approach help their people identify their distinctive strengths and weaknesses, tying them to their personal and career aspirations. Leader-coaches use emotional intelligence competence to identify the employee’s ambitions and values. Effective leaders using emotional intelligence and empathy raise self-awareness to know about the key competence they hold to manage their people. Leaders with a leadership coach approach can help their subordinates believe in themselves and their capabilities.

The review of previous literature on managerial and leadership coaching suggests that in the published literature during the 1940 and 1960s, the main theme was to explore the ways to improve human performance using psychological approaches. During the 1950s, there were nine studies, and the focus of the research was to discuss coaching management skills. From the 1960s to 1970s there were only six studies, but with no progress until 1979.

During 1980s and 1990s, the researchers were inclined to examine the relation of various power and leadership styles in an organizational context and investigate the effects of types of power and leadership styles on an organization’s culture, climate, and outcomes. Most of the published researches during the 1980s to 1999 on coaching from management perspectives were graduate dissertations, 33 journal articles, and several books. This expediential rise in academic literature coined the term executive coaching. Executive coaching takes place between the client/employee and his /her manager.

From 2000 to 2010, the literature suggests many benefits for applying leadership coaching in different business sectors with the relevant examples like (Boyce et al., 2010; Henochowicz & Hetherington, 2006; Wilson, 2004; Gerbarg, 2002; Barriere et al., 2002). The next decade also carries a similar theme and expands the research to explore the positive impact of leadership coaching on organizational outcomes; scholars like Huff et al. (2013) discussed the feedback mechanisms of coaching. Bilas & Adeeb (2018) stated that effective leadership stems from the transformative, charismatic, and ethical leadership style. The authors concluded that due to the volatile nature of our world today, the fast-paced environment is filled with constant changes and crises; there is a need to incorporate within the leadership schema the advantages of team development in business organizations.

The literature on leadership coaching also critiques approaches like Berg & Karlsen (2016) discussed that although coaching has a significant effect on the development and sustainability of organizations, especially during crises, it may not work well with all organizations and/or employees. Goleman et al. (2013) stated that coaching works best with employees who show initiative and want more professional development. Moreover, Cox et al. (2014) and Hunt & Weintraub (2002) claimed that although managers may have a genuine intention to use coaching in their leadership schema, it is easy to fail. A key reason is that managers do not spend enough time with their people. Ellinger & Bostrom (2002) and Hunt & Weintraub (2002) suggested that another barrier to coaching is a lack of communication and information about the goal and purpose-for example, about the expected effects of coaching.

Future Research and Implications

These researches has presented a detailed review of the literature and synthesize the research on professional coaching and leadership coaching over the decades exploring various electronic research databases to explore the peer-reviewed articles, student dissertations on professional coaching and leadership coaching. The research found that the literature on both streams go parallel. The study discusses how development in professional coaching has given rise to the development of leadership coaching. However, the study is limited in its time and scope, creating a gap for future researchers. For example, as the study was a chronological review of literature, future researchers might use other types of review on the topic like systematic review, content analysis, integrative analysis, etc. the researcher may also explore new models combining the concepts of professional coaching and leadership coaching. Both subjective and objective approaches can be applied in the field to clarify the different typologies and taxonomies. Future studies may discuss that professional coaching and leadership coaching are related concepts. The research is helpful for academicians and practitioners, as academicians might use its finding to further explore the topic and practitioners may apply it in their workplace, particularly those who are professional coaches.

Conclusion

The rich history of leadership management and executive coaching has created a strong foundation for the evolution of current and future knowledge on leadership coaching and its organization-wide application. This literature review refines the evolution of leadership coaching and executive coaching concepts in an organizational context and suggests many important implications of the concepts for organizational outcomes like employee performance, motivation, competencies, organizational effectiveness, effective communication, improved organizational climate or culture, harmony, cohesiveness, cooperation among employee and their leaders. A summary of the outcomes of leadership/executive coaching indicates its success if is aligned well with the reasons for coaching and organizational goals or expected outcomes.

References

Allen, L. A. (1957). Does management development develop managers.Personnel,34(2), 18-25.

Barriere, M.T., Anson, B.R., Ording, R.S., & Rogers, E. (2002). Culture transformation in a health care organization: A process for building adaptive capabilities through leadership development.Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research,54(2), 116.

Bennett, J.L., & Campone, F. (2017). Coaching and theories of learning.The SAGE Handbook of Coaching, 102-138.

Berg, M.E., & Karlsen, J.T. (2016). A study of coaching leadership style practice in projects.Management Research Review,39(9), 1122-1142.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bigelow, B. (1938). Building a training program for filed salesmen. Personnel, 14(3), 142.

Bilas, L., & Masadeh, A. (2018). Coaching as a leadership style and a method of building high performance teams.Economica,104, 25.

Boyce, L.A., Jeffrey Jackson, R., & Neal, L.J. (2010). Building successful leadership coaching relationships: Examining impact of matching criteria in a leadership coaching program.Journal of Management Development,29(10), 914-931.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bridgman, C.S., Spaethe, M., Driscoll, P., & Fanning, J. (1958). Salesmen Helped by Bringing Out Jobs Critical Incidents. Personnel Journal, 36(11), 411-414.

Brock, V.G. (2008). Grounded theory of the roots and emergence of coaching.International University of Professional Studies.

Brock, V.G. (2014). Sourcebook of coaching history. Vikki G. Brock. Kindle Edition.

Cox, E., Clutterbuck, D.A., & Bachkirova, T. (2014). The complete handbook of coaching.The Complete Handbook of Coaching, 1-504.

De Meuse, K.P., Dai, G., & Lee, R.J. (2009). Evaluating the effectiveness of executive coaching: Beyond ROI?. Coaching: An international journal of theory, research and practice, 2(2), 117-134.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Driver, R.S. (1955). Training supervisors in remote company units. Personnel Journal, 34, 9-12.

Ellinger, A.D., & Bostrom, R.P. (2002). An examination of managers' beliefs about their roles as facilitators of learning.Management Learning,33(2), 147-179.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

English, S. (2019). Professional coaching. Springer. Kindle Edition.

Fleishman, E.A., Mumford, M.D., Zaccaro, S.J., Levin, K.Y., Korotkin, A.L., & Hein, M.B. (1991). Taxonomic efforts in the description of leader behavior: A synthesis and functional interpretation.The Leadership Quarterly,2(4), 245-287.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gallwey, W.T. (2014).The Inner Game of Tennis: One of Bill Gates All-Time Favourite Books. Pan Macmillan.

Gerbarg, Z. (2002). Physician leaders of medical groups face increasing challenges.The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management,25(4), 1-6.

Glaser, E.M. (1958). Psychological consultation with executives: A clinical approach.American Psychologist,13(8), 486.

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R.E., & McKee, A. (2013).Primal leadership: Unleashing the power of emotional intelligence. Harvard Business Press.

Gorby, C.B. (1937). Everybody gets a share of the profits. Factory Management and Maintenance, 95, 82-83.

Grant, A.M. (2011). Workplace, executive and life coaching: An annotated bibliography from the behavioural science and business literature. Coaching Psychology Unit, University of Sydney, Australia.

Hayden, S.J. (1955). Getting better results from post-appraisal interviews.Personnel,31(6), 541-550.

Henochowicz, S., & Hetherington, D. (2006). Leadership coaching in health care.Leadership & Organization Development Journal.

Hicks, R.F. (2013).Coaching as a leadership style: The art and science of coaching conversations for healthcare professionals. Routledge.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hicks, R., & McCracken, J. (2011). Coaching as a leadership style.Physician executive,37(5), 70-72.

Hoppock, R. (1958). Can appraisal counseling be taught.Personnel,35(2), 24-30.

Huff, J., Preston, C., & Goldring, E. (2013). Implementation of a coaching program for school principals: Evaluating coaches’ strategies and the results.Educational Management Administration & Leadership,41(4), 504-526.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hunt, J.M., & Weintraub, J. (2002). How coaching can enhance your brand as a manager.Journal of Organizational Excellence,21(2), 39-44.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ibarra, H., & Scoular, A. (2019). The leader as coach: How to unleash innovation, energy, and commitment. Harvard Business Review.

Kampa-Kokesch, S., & Anderson, M.Z. (2001). Executive coaching: A comprehensive review of the literature.Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research,53(4), 205.

Kilburg, R.R. (2007). Toward a conceptual understanding and definition of executive coaching.

Kilburg, R.R. (1996). Executive coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 48(2), 59-146.

Krausz, R.R. (1986). Power and leadership in organizations.Transactional Analysis Journal,16(2), 85-94.

Lewis, P.B. (1947). Supervisory training methods.

Maltbia, T.E., Marsick, V.J., & Ghosh, R. (2014). Executive and organizational coaching: A review of insights drawn from literature to inform HRD practice. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 16(2), 161-183.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

McNamara, M.S., Fealy, G.M., Casey, M., O'Connor, T., Patton, D., Doyle, L., & Quinlan, C. (2014). Mentoring, coaching and action learning: interventions in a national clinical leadership development programme.Journal of Clinical Nursing,23(17-18), 2533-2541.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mold, H.P. (1951). Developing top leaders: Executive training. InProceedings of the Annual Industrial Relations Conference, 47-53.

Northouse, P.G. (2021).Leadership: Theory and practice. Sage publications.

Northouse, P.G. (2018). Leadership: Theory and practice. Sage publications.

Online Etymology Dictionary. (2020).

Parkes, R. C. (1955). We use seven guides to help executives develop.Personnel Journal,33, 326-328.

Passmore, J., & Fillery-Travis, A. (2011). A critical review of executive coaching research: a decade of progress and what's to come.Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice,4(2), 70-88.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Perley, J.D. (1957). How the personnel staff can serve line management.Personnel,33(6), 546-549.

Ridler Report. (2016). Ridler & Co: Developing leaders, delivering results.

Smither, J.W., London, M., & Reilly, R.R. (2005). Does performance improve following multisource feedback? A theoretical model, meta?analysis, and review of empirical findings.Personnel psychology,58(1), 33-66.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

van Nieuwerburgh, C., Lomas, T., & Burke, J. (2018). Integrating coaching and positive psychology: Concepts and practice.Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice,11(2), 99-101.

Whitmore, J. (2010).Coaching for performance: growing human potential and purpose: the principles and practice of coaching and leadership. Hachette UK.

Whitmore, J. (2017). Coaching for performance: The principles and practice of coaching and leadership. Nicholas Brealey.

Wildflower, L. (2013).The hidden history of coaching. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Wilson, C. (2004). Coaching and coach training in the workplace.Industrial and Commercial Training,36(3), 96-98.

Received: 04-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. JOCCC-23- 13210; Editor assigned: 06-Jan-2023, Pre QC No. JOCCC-23- 13210(PQ); Reviewed: 20-Jan-2023, QC No. JOCCC-23- 13210; Published: 31-Jan-2023