Research Article: 2022 Vol: 26 Issue: 2

Can Human Capital Promote Self-Leadership? A Study on the Contingent Marketing Workforce of India

Musarrat Shaheen, ICFAI Business School (IBS) Hyderabad, IFHE Deemed-to-be University

Keerti Shukla, Freelance Researcher, Pune

Sonali Narbariya, ICFAI Business School (IBS) Hyderabad, IFHE Deemed-to-be University, Donthanapally, Hyderabad

A. K. Subramani, Department of Management Studies, St. Peter’s College of Engineering and Technology, Avadi, Chennai

N. Akbar Jan, ICFAI Business School (IBS) Hyderabad, IFHE Deemed-to-be University

Citation Information: Shaheen, M., Shukla, K., Narbariya, S., & Subramani, A.K., & Akbar, J.N. (2022). Can human capital promote self-leadership? a study on the contingent marketing workforce of india. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 26(2), 1-8.

Abstract

Proper utilization of contingent/freelance workers has now been recognized as contributing to a firm’s competitive advantage, according to Accenture’s Tech Vision 2016 report. Thus, in the light of the growing importance of the contingent/freelancing population in an organization, this study attempts to identify factors which foster leadership strategies among marketing contingent workers which in turn will assist in developing their skills set. Based on the social cognitive theory of career management, the study proposes a model where freelancers’ human capital leads to active participation in employability activities, which affects self-leadership—behaviour-focused strategies, natural reward, and constructive thought patterns. For the present study, data were collected from around 384 freelancers of India. Hierarchical regression analysis and Process-Macros test the proposed relationships between human capital, self-leadership strategies, and employability activities. Results show a significant impact of human capital on self-leadership strategies and significant mediation of employability activities on the said relationship. The results obtained assist human resource professionals in promoting the use of self-leadership strategies by marketing freelancers.

Keywords

Self-leadership Strategies, Employability Activities, Human Capital, Marketing Contingent Workers, Freelancers in India.

Introduction

Neck et al. (1995) defined self-leadership as a process through which employees inspire themselves to achieve self-motivation and self-direction, essential for performance. Manz (1986) proposed self-leadership that allows one to naturally motivate and manage oneself to perform tasks or activities required to be done. The self-leadership process is facilitated by using both behavioural and cognitive strategies (Accenture, 2016). These strategies collectively are called self-leadership, which can apply in organizations (Neck & Houghton, 2006). The self-leadership strategies are beneficial for all the individuals at the workplace, especially the emerging liquid workforce and freelancers. Gupta (2018) suggested that a liquid workforce can be ‘seasonally’ detached and attached easily as per an organization’s strategic and operational contingent needs. Freelancers occupy an important place in the Indian economy as this category is as big as 15 million in India according to Payoneer Freelancer Income Survey (Payoneer, 2020) and growing at a rate of 20% every year. Freelancers are not bounded to any particular company and choose their project and work according to their own will (Jha et al., 2019).

Freelancers need a positive and focused approach to their personal skill sets to have a consistent profession. Especially in marketing department, contingent workers are hired to handle contingent works such as for project testing, implementation, consultancy and many more Deloitte, NA. It has also been seen that hiring the contingent workers during festive times are also common marketing strategy to handle high sales and demand from consumers in India (Chitra, 2018).

Moreover, contingent workers to remain employable need to keep abreast with new technology and skills to sustain their careers. Hence, one can say that freelancers to keep themselves performing need self-leadership strategies as a self-control mechanism. Also, high human capital helps these freelancers keep upgrading new skills required to keep getting business and have relevant skills to cater to client needs. Freelancers are hired for their expertise and niche skills; thus, human capital helps them keep innovating according to client needs. The present study aims to test and provide evidence-based finding on to what extent human capital help freelancers in the use of these self-leadership strategies.

Literature Review

Human Capital in Marketing Force

Human capital is defined as “the knowledge, skills, competencies, and attributes embodied in individuals that facilitate the creation of personal, social and economic well-being” (OECD, 2001). Human capital is the cumulation of all the activities one engages in, such as migration activities, training on-the-job, and involvement in education and health which facilitates productivity in the labor market (Lee et al., 2012). According to Dess & Picken (1999), human capital is the aggregation of all the individuals working in an organization’s knowledge, capabilities, experience, and skills. These capabilities fit work and add to the reservoir of one’s knowledge, experience, and skills through learning. Therefore, human capital is vital and provides a competitive advantage to the organization as it is relatively difficult to imitate, purchase or duplicate (Larson & Luthans, 2006). Human capital enables the marketing worker to acquire knowledge, for example, how to sell life insurance to a customer or a supercomputer to an industrial buyer (Dubas & Nijhawan, 2007). The selling process itself makes salespeople more experienced in general and specific skills. The employer's decision whether to hire contingent worker depends on expected returns from that worker, in terms of sales and revenue generated, thus, high human capital makes these contingent workers more likely to get hired.

Self-Leadership Strategies of Marketing’s Contingent Workforce

Organizations impose multiple controls of varying types on individuals. These control mechanisms are required to identify appropriate behavior, set standards for ideal behavior, individual monitor behavior. One effective way to exert organizational control is to influence individuals through rewards and reinforcements at their workplace. Another outlook views each individual as possessing and exercising some internal self-control. Self-leadership is posited by Manz (1986). According to Houghton et al. (2004), self-leadership is initiated with three strategies: constructive thought patterns, natural reward strategies, and behavior-focused strategies. With the aid of these strategies, individuals are empowered, and better control their actions, leading to direction and supervision of all the actions and behavior necessary to achieve the work goals. Since the contingent workers are outside the purview of control mechanisms of the organizations, the internal control becomes important, especially in the marketing context, which is target and number driven (Singh et al., 2017).

This can be achieved, by the marketing contingent worker, by indulging in the use of self-leadership strategies.

Employability Activities (Mediating Variable)

During work tenure, marketing employees undertake several activities to enhance and maintain their employability. These activities include indulging in career self-development activities for work experiences and extending knowledge (Van Dam, 2004). In today’s dynamic market, career advancement is possible only when marketing employees involve themselves in self-driven career management activities and become their masters and representatives of their marketing careers (Sammarra et al., 2013). This transfer in the career management activities and employment relationship indicates that employability activities have become a standard strategy for success in a marketing career (Lo Presti et al., 2018). Especially this situation holds true to the freelancers who, to remain employable, have to engage in various career development activities because they have to get along with some conventional organizational rights and more significant job uncertainty than traditional full-time employees (Osnowitz, 2010). Also, the onus of sourcing business/projects lies based on the freelancer himself, thus, making employability activities an essential part of their skill set. Other than being employable, several studies have indicated that employability activities have a significant positive association with career satisfaction (De Vos et al., 2011). ‘Social cognitive career theory’ posits that involvement in career-relevant activities, such as employability activities, is considered the determinant of self-management mechanism (i.e., self-leadership) and outcome expectations such as human capital (Brown et al., 2011).

Research Gap

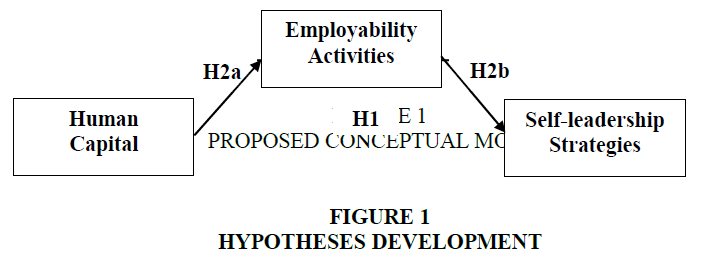

As organizations move to an alternate set of marketing workers, like liquid/contingent sales force, it becomes necessary to understand how this workforce adapts in modern organizations and what drives their performance. These sales contingent workers, work simultaneously for multiple clients and are not committed to a single client. Also, they are bound by a contract, which defines their work, compensation and incentives, for example, Insurance agents, door-to-door sales executives, advertisement agents, etc. These marketing freelancers are beyond the external control mechanisms of the organizations (Jha et al., 2019). Also, they do not enjoy the benefits of the organization’s employee development activities (Gupta, 2018). Thus, freelancers are left to develop and upgrade themselves for all employability-related activities. Hence, this study aims to investigate whether human capital impacts indulging in self-leadership strategies in the sales freelancers’ context. Also, this study intends to evaluate the role of employability activities between the association of human capital and self-leadership Figure 1.

Past studies have examined several antecedents of self-leadership, and the most researched antecedent is personality traits (Houghton et al., 2004; Furtner & Rauthmann, 2013). But limited studies are available that have explored the influence of the factors which build a marketing freelancer’s human capital. Human capital comprises those factors that make one achiever and successful and increase one’s performance and productivity (Becker, 1993; Schultz, 1961; Sidorkin, 2007). Human capital comprises work experience, self-confidence, knowledge, abilities, and others (Sidorkin, 2007). These factors allow one to control and regulate one’s behaviours and actions, such as self-leadership. Furthermore, an individual’s internal motivation increases due to improved productivity, leading to more self-influencing behaviour that complements a higher level of human capital. Thus, grounded in the elements that comprise human capital, we hypothesize the following association.

H1: Human capital is positively related to self-leadership strategies.

Human capital makes one eligible for the job market. Therefore, one can say that the factors that comprise human capital positively affect one’s job-seeking behavior and aids in grabbing employable opportunities (Vinokur et al., 2000). If one internalizes human capital, one can hold the possibility of accessing job-related information. After that, one can easily have more occupational opportunities than others (Kwon, 2009) thus indulging in employability activities. In particular, we argue that the highly educated people, those who have greater experience with work, and those who invest more time, energy, money, and resources in upskilling are better able to reap higher benefits for themselves. Hence, in turn, able to influence their work behavior (Dakhli & De Clercq, 2004). According to Cannon (2000), human capital enhances the gross productivity of individuals because humans act as an input for economic-related activities considering their physical and intellectual efforts. Thus, based on the above argument, the following hypothesis.

H2: Employability activities mediate the association between human capital and self-leadership.

Research Methodology

The study captures the perception of freelancers through survey measures. All the scale items are anchored on a Likert Type scale. Here one means ‘strongly disagree’ and five ‘means strongly agree.’ Self-leadership strategies are measured through Abbreviated Self Leadership Questionnaire given by Houghton et al. (2012). The employability Activities is assessed by Employability Activities scale developed by Van Dam (2004). Human Capital is measured with three factors - participants’ age, years of education, and years of service. A weighted average of all the three factors are taken as a composite score as suggested by Larson & Luthans (2006). The hypothesized relationships are ascertained using Hierarchical Regression Analysis.

Data was collected from (N=384) freelancers working across major cities of India. Participants were randomly picked from the freelancers’ portal www.worknhire.com. A marketing project was posted for the freelancing survey, and the interested participants were given the survey link (Google form). The respondent’s average age was 30.1 years. Around 6.9 years is the average total experience. Approximately 29% of the respondents were female, and 71% were male. We informed these respondents in advance that participation is voluntary. They were communicated about the objective of the survey being administered. The respondents are aware that this is to assess their perceptions of work-related attitudes and that information would be evaluated as an aggregative measure. This means no individual responses would be highlighted particularly. As a token of gratitude, an incentive is promised to the respondents.

Results

The data were analyzed using SPSS software. First, reliability and correlation coefficients were calculated for all the study variables, followed by Regression analysis to test the proposed hypotheses.

The Cronbach alpha reliability estimates for the self-leadership scale was 0.924 (9 items), Human capital scale was 0.880 (3 items) and for the employability activities scale was 0.861 (6 items), all these three values are more than 0.7 (Hair et al., 2010), hence it confirms reliability of the scales. The Descriptive and correlation analysis is given in Table 1.

|

Table 1 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1. Self-leadership | 4.03 | 0.75 | 1 | ||

| 2. Human Capital | 6.82 | 1.42 | 0.481** | 1 | |

| 3. Employability Activities | 4.00 | 0.70 | 0.573** | 0.358** | 1 |

Note: Cronbach’s alpha values are given in the parentheses. **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

The composite human capital score was calculated by taking a weighted average of age (60%), total experience (20%), and education (20%). These weights were assigned in order of learning based on each of them. Age contributes maximum to the building up of skills and attitudes required at the workplace, then education and experience. Hypothesis 1 (H1) was tested using linear regression, and hypothesis 2 (H2) was tested using process MACRO by Hayes. The impact of human capital on self-leadership was significantly established (β=0.19, p=0.050*). The partial mediation of employability activities on the relation between self-leadership and human capital was also established significantly. The details of regression results are compiled in Table 2.

| Table 2 STandardized Coefficients And The Indirect Effects |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Model | β | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| Outcome: Self-leadership | ||||||

| Human Capital | 0.19 | 0.02 | 1.92 | 0.050* | 0.00 | 0.10 |

| Employability Activities | 0.57 | 0.04 | 13.67 | <0.001** | 0.52 | 0.70 |

| Bootstrapped | ||||||

| Conditional Indirect Effects | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| Employability Activities* | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.06 | ||

| Note(s): *Lower and upper-level confidence intervals (LLCI, ULCI) exclude zero, indicating significant mediation. n=384. p?0.05. The standardized regression coefficients are presented. | ||||||

Discussion

The present study’s findings provide support and evidence for the prepositions of marketing management scholars regarding the vital role of human capital towards different work outcomes (Hitt et al., 2001). The results help establish the relationship between human capital, self-leadership, and employability activities. This study found enough empirical support for the positive influence of human capital on self-leadership and employability activities, for marketing contingent workers. Results could establish a significant relation of human capital with self-leadership. For freelancers, every client and job is different, which may or may not motivate them. The freelancer indulges in self-leadership strategies to make the job more pleasant and motivating. Previous researchers have already identified a few antecedents (Houghton et al., 2004; Neck & Houghton, 2006). The current study is an initial step to identify and empirically establish human capital as the antecedent to self-leadership. Edmondson (1996) suggested that leadership and human capital are significantly related.

The result of our study also helped to successfully establish the mediation of employability activities in the relationship between human capital and freelancers’ self-leadership strategies. Past literature suggests that the activities individuals undertake to improve and keep themselves employable are essential (Van Dam, 2004), thus, already establishing a positive impact of employability activities (Lo Presti et al., 2018), which is further also re-affirmed by our findings. As freelancers are not attached to a single organization thus, the onus of their career growth lies solely on themselves and not on any client organization since the association with any client is very task-specific. Indulging in employability activities is likely to give them confidence by participating in developmental activities that help them remain employable for the longer term, make them more internally motivated, and use self-leadership to regulate and manage their behavior. Freelancers with self-leading intent take themselves as a reference point; they strive to improve themselves by getting involved in employability activities.

Theoretical and Practical Contribution

Human capital is of paramount importance for the competitive advantage of organizations because the workforce’s knowledge and skills are considered unique and hence cannot be imitated or easily duplicated or purchased (Larson & Luthans, 2006). Therefore, organizations have started investing in individual human capital that will make the organization’s collective human capital. The skills/knowledge that the organizations do not possess that is outsourced increases the organization’s overall human capital.

Thus, freelancers with expertise and niche skills become imperative to client organizations. The findings emphasize the importance of human capital for increasing marketing freelancers’ self-leadership strategies. As stated earlier, these freelancers do not enjoy the benefits of training and development as the organization’s employees do. Also, they are hired for the skills and expertise they possess. Thus, it becomes necessary for them to keep upgrading their skills and make themselves employable. As a practitioner’s prism, it will be helpful to understand the human capital that individual marketing freelancer brings with them while working for the organization. That individual human capital must complement and increase the overall organization’s human capital and thus, serve as a competitive advantage for the organization. Therefore, it benefits both the freelancer as well as the organization. The study also paves the path for further research into the self-leadership strategies of freelancers. It emphasizes and tests the application of Social Cognitive Career Theory on freelancers. This will broaden the horizons of both self-leadership and human capital domains.

Conclusion

Thought the prime contribution of the present study is the empirical examination of the additive value of human capital towards self-leadership strategies in the marketing workforce. The findings reveal a significant positive impact of human capital on self-leadership strategies of marketing contingent workers. Extant literature and previous research have demonstrated that human capital is vital in an organization as it aids in understanding and managing human resources. Knowing that self-leadership adds value to human capital in predicting freelancers’ desirable attitudes will generate future research to see if it holds in other samples and environments.

References

Accenture. (2016). Technology vision for oracle 2016: Trend 2 Liquid workforce, Accenture Report. Available at https://www.accenture.com/ t20160929T023536__w__/dk-en/_acnmedia/PDF-26/Accenture-TechVision-for-Oracle-Trend-2.pdf. Accessed on 24 January 2022.

Becker, G.S. (1993). Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education (3rd Ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brown, S.D., Lent, R.W., Telander, K. & Tramayne, S. (2011). Social cognitive career theory, conscientiousness, and work performance: A meta-analytic path analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79, 81–90.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cannon, E. (2000). Human capital: level versus growth effects. Oxford Economic Papers, 52, 670677.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chitra, R. (2018). Hiring temps during festive season up 20%, Available at https://timesof india.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/hiring-temps-during-festive-season-up-20/ articleshow/66156796.cms Accessed on 15 January 2022.

Dakhli, M. & De Clercq, D. (2004). Human capital, social capital, and innovation: a multi-country study. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 16(2), 107-128.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

De Vos, A., De Hauw, S. & Van der Heijden, B.I. (2011). Competency development and career success: The mediating role of employability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 438-447.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dess, G.D. & Picken, J.C. (1999). Beyond productivity: How leading companies achieve superior performance by leveraging theirs human capital. New York: American Management Association.

Dubas, K.M., & Nijhawan, I.P. (2007, July). A human capital theory perspective of sales force training, productivity, compensation, and turnover. In Allied Academies International Conference. Academy of Marketing Studies. Proceedings 12(2). Jordan Whitney Enterprises, Inc.

Edmondson, A.C. (1996). Three faces of Eden: The persistence of competing theories and multiple diagnoses in organizational intervention research. Human relations, 49(5), 571-595.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Furtner, M.R. & Rauthmann, J.F. (2013). How self-leaders are perceived on the Big Five. Psychology of Everyday Activity, 6(1), 22-29.

Gupta, M. (2018). Liquid Workforce: The Workforce of the Future. In P. Duhan, K. Singh, & R. Verma (Eds.), Radical Reorganization of Existing Work Structures Through Digitalization (pp. 1–17). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., & Anderson, R.E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis. Seventh Edition.

Hitt, M., Bierman, L., Shimizu, K. & Kochhar, R. (2001). Direct and Moderating Effects of Human Capital on Strategy and Performance in Professional Service Firms: A Resource-Based Perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 13-28.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Houghton, J.D., Bonham, T.W., Neck, C.P. & Singh, K. (2004). The Relationship between Self-Leadership and Personality: A Comparison of Hierarchical Factor Structures. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 19, 427-441.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Houghton, J.D., Dawley, D. & DiLiello, T.C. (2012). The Abbreviated Self-Leadership Questionnaire (ASLQ): A More Concise Measure of Self-Leadership. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 7(2), 216-232.

Jha, J.K., Pandey, J. & Varkkey, B. (2019). Examining the role of perceived investment in employees’ development on work-engagement of liquid knowledge workers: Moderating effects of psychological contract. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing, 12(2), 225-245.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kwon, D.B. (2009). Human capital and its measurement. In The 3rd OECD World Forum on “Statistics, Knowledge and Policy” Charting Progress, Building Visions, Improving Life, pp. 27-30.

Larson, M. & Luthans, F. (2006). Potential added value of psychological capital in predicting work attitudes. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 13(2), 75-92.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lee, S.P., Cornwell, T.B. & Babiak, K. (2012). Developing an Instrument to Measure the Social Impact of Sport: Social Capital, Collective Identities, Health Literacy, Well-Being and Human Capital. Journal of Sport Management, 27, 24-42.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lo Presti, A., Pluviano, S. & Briscoe, J.P. (2018). Are freelancers a breed apart? The role of protean and boundaryless career attitudes in employability and career success. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(3), 427-442.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Manz, C.C. (1986). Self-leadership: Toward an expanded theory of self-influence processes in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 11, 585-600.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Neck, C.P. & Houghton, J.D. (2006). Two decades of self-leadership theory and research: Past developments, present trends, and future possibilities. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21, 270-295.

Neck, C.P., Stewart, G. & Manz, C.C. (1995). Thought self-leadership as a framework for enhancing the performance of performance appraisers. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 31, 278-302.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

OECD. (2001). The well-being of nations: The role of human and social capital. Paris: OECD.

Osnowitz, D. (2010). Freelancing expertise:Contract professionals in the new economy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Payoneer, (2020). The 2020 Freelancer Income Report Available at https://explore.payoneer.com/2020-freelancer-income-report/ Accessed on 15 January 2022.

Sammarra, A., Profili, S. & Innocenti, L. (2013). Do external careers pay?off for both managers and professionals? The effect of inter-organizational mobility on objective career success. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(13), 2490–2511.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Schultz, T.W. (1961). Investment in human capital. The American economic review, 51(1), 1-17.

Sidorkin, M.A. (2007). Human Capital and the Labor of Learning: A Case of Mistaken Identity. Educational Theory, 57(2). 159-170.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Singh, R., Kumar, N., & Puri, S. (2017). Thought self-leadership strategies and sales performance: integrating selling skills and adaptive selling behavior as missing links. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing.’

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Van Dam, K. (2004). Antecedents and consequences of employability orientation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 13(1), 29-51

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Vinokur, A.D., Schul, Y., Vuori, J. & Price, R.H. (2000). Two years after a job loss: long-term impact of the JOBS program on reemployment and mental health. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 32-47.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 07-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-11397; Editor assigned: 09-Jan-2022, PreQC No. AMSJ-22-11397(PQ); Reviewed: 22-Jan-2022, QC No. AMSJ-22-11397; Revised: 24-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. AMSJ-22-11397(R); Published: 30-Jan-2022