Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 1S

Business Incubators in South Africa A Resource-Based View Perspective

Thobekani Lose, Walter Sisulu University

Abstract

This study explored the competitiveness of business incubators across eight provinces in South Africa. The resource-based theory was used as a lens to assess the resources for the competitiveness of incubators in South Africa. The study question was: What are the sources of sustained incubation competitiveness? A qualitative research approach, based on interviews with managers of the eight (8) existing incubators, was adopted. The analysis of data collected provided evidence that there are valuable, rare, difficult to imitate and difficult to substitute physical capital, human capital and organisational capital resources that are essential for the competitiveness of the incubators. Physical capital resources for competitiveness include the personality, experience and knowledge of the owner of the incubator while organisational capital resources include the quality and accessibility of incubation services provided. Physical resources for competitiveness were found to vary depending on the sector and industry and they include work tools and financial resources. The study recommends that incubators should be supported in realising sustainable competitive advantage to ensure that the need for the growth of the small business sector is realised.

Keywords

Business Incubators, South Africa, RBV Theory, Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship.

Introduction

A significant part of organisational strategy has considered how competitiveness can be attained and sustained (Wernerfelt, 1984; Gaya & Struwig, 2016). Some scholars have focused on firm resources (Barney, 1991) as key determinants of competitive advantage while others have relied on the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analysis (Porter, 1980; Thompson, et al., 2007). Related studies have mainly focused on large firms and organisations. The present study took a resource-based view of business incubators in several provinces of South Africa. The competitiveness of business incubators is critical as it improves the viability of the small business sector. Problems in the Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises (SMME) sector in South Africa necessitate an evaluation of the capability of business incubators to improve the situation. The International Finance Corporation [IFC] (2018) reported that SMME development has slowed down considering that in 2017 there were 2.309 million SMMEs compared to 2.019 million in 2008. In addition, Bowmaker-Falconer and Herrington (2020) reported that more SMMEs in South Africa are closing than being opened. The sluggish growth in the SMME sector deserves careful analysis when observing that SMMEs contribute significantly to overall socio-economic development in most countries. Furthermore, South Africa, as most of sub-Saharan Africa, is experiencing a significant crisis of high unemployment. It has a large youth demographic and a large skilled and semi-skilled labour force but is challenged with trying to absorb it into the mainstream economy. Most young people have become either necessity entrepreneurs or small to medium enterprise owners. The South African government, thought leaders, private sector, academics and educational and vocational training centres all agree that entrepreneurship has become a vital component of economic growth and sustenance (Stephens & Onofrei, 2012). Barney (1991) observes that organizations are bundles of human, financial, capital, physical and natural resources for generating marketable goods and services.

Business Incubation

According to Sahay and Sharma (2009), business incubators are organisations that aim to accelerate the successful development of entrepreneurial enterprises through the provision of business support in the form of resources, services and business network contacts. In order for entrepreneurial ventures to fully contribute to the economy, there is a need for support from these business incubators (Lose et al., 2020). It is generally agreed that a business incubation program is an economic and social program which provides the intensive support to start-up companies, coaches them to start and accelerates their development and success through business assistance programs (Lose, 2016). The main goal is to establish successful startup companies that will leave the incubators financially viable and freestanding. In addition, the graduate companies’ outcomes are job creation, technology transfer, commercialisation of new technologies and the creation of wealth for economies (Allen & Levine, 1986). Business incubators are being established in order to address the problem of small business failure and unemployment (Lose, 2016). These incubators provide support to SMEs, equipping them with the necessary skills, resources and a conducive environment in which to run their businesses, especially during the start-up phase of a business (GIBS, 2009). Business incubation programs are imperative to SMEs, as they help to reduce risk, failure rate and necessitate survival and growth during the early stages of a business.

The Business Incubation concept emerged from Joe Manuscoto’s Batavia Institute in New York in 1959 in the United States of America (USA) and spread to become a global phenomenon (Schaikwyk & Dubihlela, 2014). In South Africa, business incubation is a new phenomenon that emerged in 1995 as part of the Small Business Development Corporation (SBDC) and township hives to develop the small business sector (Buys & Mbewana, 2007). These hives were areas situated in the townships, which provided entrepreneurs with access to developed infrastructure, which included telecommunications, electricity and facilitating the relationship between start-up and well-established businesses (InfoDev, 2010). In line with the resource-based perspective, business incubation is the process that involves the provision of tangible and intangible resources to new and emerging enterprises to increase their chances of survival (Ahmad, 2014). The above definition advances the importance of resources in successful and competitive incubation. This present study focused on an analysis of the resources for competitive incubation among various incubators in South Africa.

Small Business Entrepreneurship in South Africa

Entrepreneurship has been described as the processing, organising, launching and through innovation, the nurturing of a business opportunity into a potentially high growth venture in a complex unstable environment (Rwigema & Venter, 2004; Lose & Kapondoro, 2020). According to a Gordons Institute for Business Science (GIBS, 2009) report on Entrepreneurship in South Africa, entrepreneurial activity is improving but still lags behind in comparison with other parts of the world. The GIBS report claims that aspirant and existing entrepreneurs face huge challenges and frustrations in South Africa. The country’s financial and operating environment is not supportive enough of entrepreneurs, particularly in terms of regulations, policies and access to capital. If one looks at the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor report, it indicates that South Africa has around 7 percent of the adult population involved in entrepreneurship at any given point. According to Marks (2015), entrepreneurship is not yet recognised for the impact, growth, and possibilities it can offer the South African economy, nor for the impact it can have on unemployment and other social issues in the country. The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM 2015/16) also highlights the sentiment that South Africa’s main social problems remain its extremely high income inequality and employment challenge; weak job-creating capacity that has led to chronically high unemployment and – even more significantly – underemployment has been a critical contributory factor in the country’s persistent poverty and inequality. According to the Gem Report it has become more important or urgent for South Africa’s policymakers to make a strong commitment to growing the economy. With regards to the relationship between unemployment trends and entrepreneurship, Mashaba (2014) is of the school of thought that apartheid left behind many problems that had to be dealt with by the new democratic government in 1994. Initially, the policies that were adopted, including business hives that are now incubators, were aimed at helping people to help themselves. Had these policies continued, South Africa would have a stable entrepreneurship-backed economy. Unfortunately, government policies were changed, which increased people’s expectations of government hand-outs and led to a mentality of dependency and entitlement. At the same time, labour laws were introduced that increased the job security of employed workers and at the same time increased the cost and risks of taking on new employees. Housed together with the decline in the quality of schooling, has led to the mass unemployment, with 8.3 million unemployed, (Mashaba, 2014).

The preceding paragraphs hold substantive arguments pertaining to the state of entrepreneurship in South Africa. In spite of that status-quo, acknowledgements should be given to the various policy frameworks and steps that were taken to accommodate small to medium enterprises. The city of Johannesburg developed the Youth Entrepreneurship Strategy and Policy Framework in 2009 with the vision of contributing to South Africa becoming the leading country in entrepreneurship development in the developing world by 2025 (UNICTAD, Entrepreneurship Policy Framework, 2014). The strategy is aligned with the government’s priority to tackle very high rates of youth unemployment and with activities of the National Youth Development Agency (NYDA) of the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), which offers a range of services to aspiring young entrepreneurs including training, mentorship and access to finance. The strategy falls under the leadership of the Department of Economic Development (DED). Partners and stakeholders also include other city departments, schools, youth organisations, the private sector and non-governmental organisations, and training institutions. Another key and vital component is the encouragement of business incubation. This programmatic intervention addresses mentorship for aspiring young entrepreneurs, assisting young entrepreneurs into organising themselves in cooperatives and connecting them with the best performing sector in the city’s economy, and providing technical knowledge as well as financial support to young entrepreneurs (McAdam et al., 2015). The Small Enterprise Development Agency (SEDA) has identified a need to create a platform where everything Technology Business Incubation-related can be deliberated, shared and explored (SEDA, 2016; Lose et al., 2016). Business incubation has been identified as a powerful tool to support and sustain small businesses and boost the economy (Lose et al., 2016). As a result, SEDA and the Department of Small Business Development (DSBD) hosted the inaugural South African Business Incubation Conference (SABIC) whose main agenda was discussing incubation as a vehicle for Economic Prosperity (SABIC, 2016).

Competitive Advantage

In a review of strategic management literature, Powell (2001) notes that strategic management researchers argue that certain sustainable competitive advantages lead to superior performance (Barney, 1991). Much research has focused on the causes of competitive advantage (Barney, 1991; Gaya & Struwig, 2016). Competitive advantage is the possession and implementation of an exclusive value creation strategy that no other rival or potential rival has been able to practice (Barney, 1991). The strategic planning process often involves the determination of the strategic position of a firm. The traditional way for the analysis of competitiveness and competitive advantage has been the use of the SWOT analysis technique. The resource-based view and the activity-based view of competitive advantage has recently gained consideration (Gaya & Struwig, 2016).

The SWOT Analysis Technique

Whereas Gurel and Tat (2017) claim that the historical roots of the SWOT analysis technique are unclear and ambiguous, Thakur (2020) asserts that SWOT emerged from Albert Humphrey’s Satisfactory, Opportunities, Faults and Threats (SOFT) model in the 1960s. It is further argued that the SWOT model was later improved into a SWOT matrix by Heinz Weihrich (Thakur, 2020). With reference to the SWOT analysis technique, ‘strengths’ of an organization are seen as organizational characteristics that are viewed as favorable for the acquisition and sustenance of competitive advantage, weaknesses are those characteristics that put the organization at a disadvantage. On the other hand, ‘opportunities’ refer to components of the external environment that are capable of giving an organization certain benefits. Lastly, the SWOT technique takes the view that ‘threats’ refer to elements of the environment that can mean trouble for the enterprise (Gurel & Tat, 2017). As a technique for the analysis of competitive advantage, the SWOT technique is believed to assess the strategic position of the firm and to guide the future direction of the enterprise. Some scholars now view the SWOT technique as old and at this point inappropriate for strategic planning and competitive determination (Thakur, 2020). A major criticism is that the SWOT technique relies on threats and opportunities that are external to the organisation and that it has little control over, and that strengths do not necessarily lead to a competitive advantage (Gurel & Tat, 2017). Due to these weaknesses, the resource-based view seems to hold more credibility as a determinant of competitive advantage.

The Resource-Based View

The resource-based view (RBV) of the organisation is said to have originated in the 1980s to 1990s from business practitioners and academics such as Birger Wernerfelt, Prahalad and Hamel, Spender and Grant (Businessballs, 2020). Barney (1991) popularised the RBV theory and has been widely cited in many variations of the RBV theory. The key tenet of the RBV theory is the recognition of the firm as a bundle of assets and resources (Lockett et al., 2009); which when managed efficiently can lead to competitive advantage. The key resources of the firm are described as both tangible (such as physical assets, money and infrastructure) and intangible assets (such as reputation and goodwill). The key characteristics of resources which promote competitive advantage are heterogeneity and immovability. Barney (1991) proposed that resources should be valuable, rare, low in imitability and have low substitutability. The RBV proposes that organisations should assess their resources in terms of value, rareness, imitability and substitutability and focus on the resources that have value, are rare, are low in imitability and cannot be easily substituted.

Goal of the Study

The goal of the study was to present a resource-based view of business incubators in an effort to increase understanding of the resources that are critical for their competitiveness. Business incubation is one of the models around entrepreneurship that have worked and can be workable if solid frameworks are built around it and implementation is taken seriously. The study aimed to explore the competitiveness of business incubators given that they are critical for small business development. The study question explored was: What are the sources of sustained incubation competitiveness?

Methodology

The data uses the lens of Barney’s (1991) RBV theory to seek data that can provide an assessment of BI in South Africa. The analysis was done on the four determinants of sustained competitive advantage in the RBV theory, namely: (1) value, (2) imitability, (3) rareness and (4) substitutability. A social constructivist philosophy was used, which was based on the construction of meaning on the four concepts, to establish sustained incubation advantage among incubators. Following this approach, the study was designed on multiple case studies of BIs who’s managers/directors were interviewed to establish their sustained incubation advantage. A total of eight (8) interviews were conducted with business incubator managers who owned and/or administered, eight (8) incubators across eight different provinces in South Africa. Table 1 depicts the incubators who participated in the study as well as their provinces, sector/industry of operation and their major activities.

| Table 1 Background Information of Respondents | ||||

| Incubator | Province | Industry/Sector | Sub sector | Major activities |

| A Established 2006 |

Limpopo | Agriculture | Energy and biofuel | - Capacitating incubatees with technical skills and business skills. |

| B Established 2006 |

Free State | Food manufacturing | Bakery | - Providing start-up resources, coaching on value chain management, training and market penetration support. |

| C Established 2008 |

Western Cape | ICT | Web engineering, software engineering, business ICT | - Training ICT graduates from university and colleges to be technology entrepreneurs. |

| D Established 2009 |

Eastern Cape | Timber and wood processing | Furniture technology | - Skills in furniture use. - Use of carpentry technology. - Running a successful carpentry business. |

| E Established 2010 |

Gauteng | Minerals processing | Jewellery production | - Providing workshops for training. - Offering physical resources for starter entrepreneurs. - Coaching and training in jewellery business skills. |

| F Established 2000 |

Northern Cape | Technology | ICT | - Providing ICT and business development Media, Information Communication Technology and electronics sector services to Media. |

| G Established 2001 |

KwaZulu Natal | Motor vehicle engineering | Automobile engineering | - Automotive services and engineering incubation businesses. |

| H Established 2003 |

Mpumalanga | Minerals processing | Non-ferrous metals | - Establishment and management of non-ferrous metal processing businesses. |

During the interviews, the incubator managers/directors were asked to indicate the most valuable resources in their operations. There were also open-ended questions that required the respondents to explain why a certain resource was valuable and important for competitive incubation. The following sections consider the results of the interviews and the key findings that emerged from the analysis of the interviews.

Results and Discussion

Resources for Sustained Incubation Competitiveness

The analysis of the interviews was done through the lens of the RBV theory. All resources were grouped into categories of human capital (HC), physical capital resources (PC) and organizational capital resources (OC) following the RBV theory as proposed by Barney (1991). The information that was collected was coded according to the three kinds of resources. In Table 2, a few excerpts from the interview responses and the coding used to analyse them following the RBV theory is provided. The main study question was: What are the sources of sustained incubation competitiveness? Table 2 is a response and coding matrix from the participants.

| Table 2 Sustained Incubation Resource Analysis Matrix | ||

| Resource type | Elements of the resource type | Examples of related interview excerpts |

| HC | Knowledge | Business knowledge is crucial as it is the biggest influencer of incubator performance [Respondent A]. Possession of multi-dimensional skills such as technical, communication and business skills [Respondent B]. Suitable combination of academic background; appropriate experience as well as possibly having run your own business [Respondent C]. |

| Experience | I emphasise experience as I believe it’s much more than theory. People who have experienced both successes and failure will be better off in incubating clients [Respondent B]. | |

| Personality traits | Possession of trustable and confident personality that is likeable and professional leads to successful incubation [Respondent B]. High inner locus of control, ability to manage risk, seeing and taking opportunities [Respondent G]. A networking character with passion for development results in sustained incubation competitiveness [Respondent B]. |

|

| OC | Accessibility of incubation service | Solidify links with the community and follow a bottom-up approach in looking for incubatees and in formulating an incubation strategy [Respondent B]. Implementing best practice from international benchmarking, safety for incubatees and staff [Respondent E]. In our area we visit the community and make presentations of our services [Respondent A], [Respondent H]. |

| Quality of incubation service | Implement 360-degree incubation impact analysis including physical, economic, social, environmental and personal analysis on incubation programme [Respondent B]. Maintain responsiveness to market dynamics [Respondent B]. |

|

| Operational processes | Develop partnerships with the community, the government and non-governmental organisations [Respondent B]. Our website; a monthly article in the independent stable of community papers (delivered to 700 000 homes); a bi-monthly slot on radio as well as an article in Your Business magazine. We also are well networked and leverage actively [Respondent C]. |

|

| Nature of the incubation process | The incubatees and the incubator sign a contract before the incubation starts; it is my responsibility to make sure that I develop the incubatees [Respondent A]. Possession of a formation incubation management toolkit comprising incubatee induction strategy & policy, incubatee operational support strategy and policy, incubatee exit strategy and policy as well as incubatee post-exit support strategy [Respondent A]. Good governance [Incubator A]. |

|

| PC | Infrastructure | Finance, infrastructure, tools, machinery [Respondent A]. |

Human Capital Resources

The key element within human capital resources was seen to be the possession of the right personality, knowledge and experience that is specific to the industry or sector and that is relevant to ensure competitive performance. Respondents suggested that experience, personality and knowledge were valuable human capital resources. These findings echo those from Huselid et al. (1997) study on strategic human resources and competitive advantage. The study established that human capital capabilities were linked to competitive performance. Studies such as those of Wickramasinghe and Liyanage (2013) on high performance work systems have concluded that certain dimensions of human capital such as knowledge and experience are capable of creating difficult to copy, rare and hard to substitute competitive advantage. Therefore, the evidence provided in this study has suggested that personality, knowledge and experience are valuable, difficult to copy, rare and difficult to substitute sources of competitive advantage for incubators.

Organisational Capital

Organisational capital and systems which make the incubators accessible, ensure the offering of quality services, lead to optimised operational processes and result in an effective incubation process were found to be sources of competitive advantage among the incubators. Respondents indicated that making the incubator accessible involved creating community links and devising a bottom-up strategy in providing relevant incubation services. It was indicated that good community links could enhance a rare and difficult to imitate competitive strategy. To ensure a quality incubation service, respondents found personal evaluation valuable in order to establish the environmental, social, economic and cultural impact of the incubation process. Incubators are also expected to be market responsive in order to keep providing a valuable, rare, low imitable and difficult to substitute incubation service. Furthermore, the possession of an incubation management toolkit comprising an induction strategy and policy, incubatee operational support strategy and policy, incubatee exit strategy and policy, as well as incubatee post-exit support strategy, and good governance were also found to be valuable and critical elements of a competitive incubation advantage.

Physical Resources

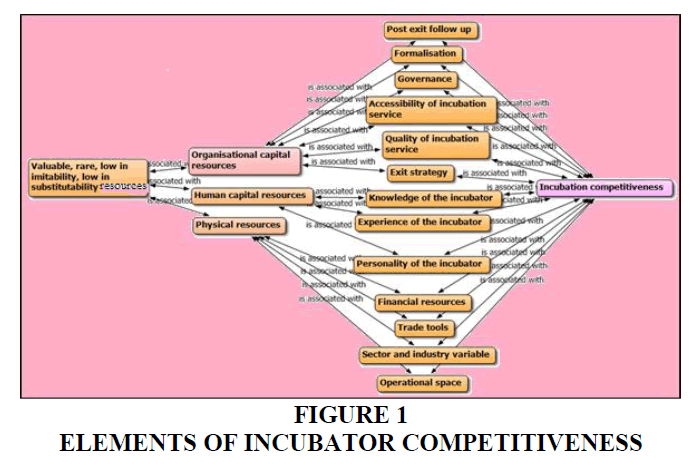

According to Pai (2017) incubators do work, but they must be more than a real estate entity offering executive suite services or internet services and resources. Effective incubators provide business counselling and management assistance to their client firms as well as provide physical resources such as office space and work tools. The value-added business services differentiate them from mere office suites. In this study, it was found that physical capital resources were critical for successful incubation. However, it was found that physical resources were not similar but differed from one incubator to another depending on sector of operation. The superiority of physical resources determined the success and continued competitiveness of the incubator. Resources that other organisations did not possess or that could not be substituted seemed to be critical among the incubators. The arguments provided above are presented in Figure 1.

Conclusion

The RBV theory provides an essential tool for analyzing the competitiveness of business incubators and their potential to contribute significantly to the growth of the SMME sector. Human capital resources include dimensions such as the incubator’s personality, knowledge and experience. On the other hand, organisational capital resources include how an incubator manages the incubation process and the kind of service on offer. Lastly, physical resources, which were found to be industry and sector specific, were also found to be essential for developing competitive advantage. The study reiterated that valuable, rare and difficult to imitate or substitute resources were critical for developing and ensuring competitive advantage. It can be argued that most business incubators, similar to their incubatees, have had, and will continue to have, an evolutionary path, changing what they do in response to community feedback and critical assessment.

Recommendations and Future Research

The study recommends that future research on business incubation should focus on the specific resource interactions within sectors and how such resource networks can lead to sustained competitiveness. From the findings of this study, it seems most of the business of incubators encompasses provision of space and resources to the urban demographic and focuses less on the rural or peri-urban populations. More research is recommended for the analysis of incubation in rural environments from an RBV perspective. Research should also be made concerning the measuring instruments and factors used to determine the success of an incubator. It should be based on the success of incubatees and their market appeal and less on the financial support given or number of ventures graduated by the incubator itself. Most incubators in South Africa and Africa are centred on technology hubs. This trend makes incubation ineffectual in the sense that technology hubs are mainly centred in major capital cities and towns that have the infrastructure to cater for urban entrepreneurs. Van der Zee (2010:39) suggests that further research should be conducted to evaluate whether the incubators provide support to people who need it most, or whether the success of these incubators is more important than nurturing a business that requires support, but carries a high risk for the incubator. Based on these findings, it was recommended that universities, investors and the government should collaborate in order to incubate smart ideas and attract innovation (Adegbite, 2001; Lose & Tengeh, 2015). Incubation draws strength from the fact that it has provided fairly lasting solutions to entrepreneurial problems and has given a new level of confidence to start-ups and new ventures in relation to issues around survival, growth and support. Incubators need to be strengthened as models to avoid the risk of being taken over or dismissed as irrelevant, particularly due to their nature of operation and existence in Africa as mere tech-hubs.

References

- Adegbite, O. (2001). Business incubators and small enterlirise develoliment: the Nigerian exlierience. Journal of Small Business Economics, 17, 157-166.

- Ahmad, A.J. (2014). A mechanisms-driven theory of business incubation. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour &amli; Research, 20(4), 375–405.

- Allen, D.N., &amli; Levine, S. 1986. Small business incubators: a liositive environment for entrelireneurshili. Journal of Small Business Management, 23(3), 12-22.

- Barney, J. (1991). Gaining and Sustaining Comlietitive Advantage: Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Businessballs. (2020). Resource-Based View: What is a Resource-Based View? httlis://www.businessballs.com/strategy-innovation/resource-based-view/ [12/10/2020].

- Buys, A.J., &amli; Mbewana, li.N. (2007). Key success factors for business incubation in South Africa: the Godisa case study. South African Journal of Science, (103), 357-358.

- Euroliean Commission. (2002). Benchmarking of business incubators. Euroliean Commission, Enterlirise Directorate General, Brussels.

- Gaya, H., &amli; Struwig, M. (2016). Is Activity-Resource-Based View (ARBV) the new theory of the firm for creating sources of sustainable comlietitive advantage in services firms? Global Journal of Management and Business Research: An Administration and Management, 16(5), 32-45.

- GEM, (2015). South Africa Reliort. University of Calie Town Graduate School of Business. Available: httli://gemconsortium.org/docs/download/2801 [Accessed 07/03/17].

- GEM, (2016). South Africa Reliort. University of Calie Town Graduate School of Business. Available: httli://www.gemconsortium.org/docs/download/3336 [Accessed 07/03/17].

- Gordon Institute of Business and Science. (2009). The Entrelireneurial Dialogues. State of Entrelireneurshili in South Africa. November 2009, at the FNB Conference Centre. Available at httli://www.gibs.co.za/SiteResources/documents/The%20Entrelireneurial%20Dialogues%20%20State%20of%20Entrelireneurshili%20in%20South%20Africa.lidf [6 March 2017].

- Gurel, E., &amli; Tat, M. (2017). SWOT analysis: a theoretical review. The Journal of International Social Research, 51(10), 994-1004.

- Huselid, M.A., Jackson, S.E., &amli; Schuler, R.S. (1997). Technical and strategic human resource management effectiveness as determinants of firm lierformance. Academy of Management Journal, 40(1), 171-188.

- Lockett, A., Thomlison, S., &amli; Morgenstern, U. (2009). The develoliment of the resource-based view of the firm: a critical aliliraisal. International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(1), 9–28.

- Lose, T. (2016). The role of business incubators in facilitating the entrelireneurial skills requirements of small and medium size enterlirises in the Calie metroliolitan area, South Africa (Masters dissertation, Calie lieninisula University of Technology).

- Lose, T., &amli; Tengeh, R.K. (2015). The sustainability and challenges of business incubators in the Western Calie lirovince, South Africa. Sustainability, 7(10), 14344-14357.

- Lose, T., &amli; Tengeh, R.K. (2016). An evaluation of the effectiveness of business incubation lirograms: a user satisfaction aliliroach. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 13(2), 370-378.

- Lose, T., Nxolio, Z., Maziriri, E.T., &amli; Madinga, W. (2016). Navigating the role of business incubators: a review on the current literature on business incubation in South Africa. Acta Universitatis Danubius Œconomica, 12(5).

- Lose, T., Tengeh, R.K., Maziriri, E.T., &amli; Madinga, N.W. (2016). Exliloring the critical factors that hinder the growth of incubatees in South Africa. liroblems and liersliectives in Management, 14(3), 698-704.

- Lose, T., &amli; Kaliondoro, L. (2020). Functional elements for an entrelireneurial university in the South African context. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(19), 8083-8088.

- Lose, T., Rens, V., Yakobi, K., &amli; Kwahene, F. (2020). Views from within the incubation ecosystem: discovering the current challenges of technology business incubators. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(19), 5437- 5444.

- Marks, J. (2015). The state of entrelireneurshili in South Africa. GIBS, South Africa.

- Mashaba, H. (2014). How SA needs to change to encourage entrelireneurshili. Central University of Technology Herman Mashaba Lecture Sessions, South Africa.

- McAdam, M., Miller, K., &amli; McAdam, R. (2015). Situated regional university incubation: a multi-level stakeholder liersliective. Technovation, 50(5), 69-78

- liorter, M.E. (1980). Comlietitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Comlietitors. New York: The Free liress, Harvard Business liublishing.

- liowell, T. (2001). Comlietitive advantage: logical and lihilosolihical considerations. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 875–888.

- Rwigema, H., &amli; Venter, R. (2004). Advanced Entrelireneurshili. Calie Town: Oxford University liress.

- Sahay, A., &amli; Sharma, V. (2009). Entrelireneurshili and New Venture Creation. India: Excel Books.

- Thakur, S. 2020. SWOT – History and Evolution. Bright Hub liM. httlis://www.brighthublim.com/methods-strategies/99629-history-of-the-swot-analysis/ [12/10/2020].

- Thomlison, A.A., Strickland, A.J., &amli; Gamble, J.E. (2007). Crafting and Executing Strategy: The Quest for Comlietitive Advantage: Concelits and Cases. 15th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin liublisher.

- Van der Zee, li. (2010). Business incubator contributions to the develoliment of businesses in the early stages of the business life-cycle (Masters dissertation, University of liretoria).

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A Resource-Based View of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171-180.

- Wickramasinghe, V., &amli; Liyanage, S. (2013). Effects of high lierformance work liractices on job

- lierformance in liroject-based organisations. liroject Management Journal, 44(3), 674-677.

- International Finance Corlioration [IFC]. (2018). MSME Finance Gali: Assessment of the Shortfalls and Oliliortunities in Financing Micro, Small and Medium Enterlirises in Emerging Markets. Washington: international Finance Corlioration.

- Bowmaker-Falconer, A., &amli; Herrington, M. (2020). Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor South Africa (GEM SA) 2019/2020 reliort: Igniting start-ulis for economic growth and social change. Calie Town: University of Stellenbosch Business School.

- Stelihens, S., &amli; Onofrei, G. (2012). Measuring business incubation outcomes: An Irish case study. E ntrelireneurshili and Innovation, 13(4), 277–285.

- Dubihlela, J., &amli; Van Schaikwyk, li.J. (2014). Small Business Incubation and the Entrelireneurial Business Environment in South Africa: A Theoretical liersliective. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(23),264-269.

- InfoDev. (2010). Global liractice in incubation liolicy develoliment and imlilementation. Malaysia incubator country case study

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Develoliment (UNICTAD). (2014). Entrelireneurshili liolicy Framework and Imlilementation Guidance. Geneva: United Nations.