Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 6

Bank Efficiency in Indonesia: Empirical Evidence Using Data Envelopment Enalysis

Ahmed Sameer El Khatib, Federal University Of São Paulo

Jose Roberto Ferreira Savoia, University Of São Paulo

Citation Information: Khatib,A., & Savoia , J., (2023). Bank efficiency in indonesia: Empirical evidence using data envelopment enalysis. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 27(6), 1-21.

Abstract

As a Muslim majority country, Indonesia is also affected by the Islamic finance resurgence that has taken place in the Middle East and rest of the world during the last three decades. The aim of the present paper is to examine the revenue efficiency of the Indonesian Islamic banking sector. The study also seeks to investigate the potential internal (bank specific) and external (macroeconomic) determinants that influence the revenue efficiency of Indonesian domestic Islamic banks. We employ the whole gamut of domestic and foreign Islamic banks operating in the Indonesian Islamic banking sector during the period of 2009 to 2018. The level of revenue efficiency is computed by using the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) method. Furthermore, we employ a panel regression analysis framework based on the Ordinary Least Square (OLS) method to examine the potential determinants of revenue efficiency. The results indicate that the level of revenue efficiency of Indonesian domestic Islamic banks is lower compared to their foreign Islamic bank counterparts. We find that bank market power, liquidity, and management quality significantly influence the improvement in revenue efficiency of the Indonesian domestic Islamic banks during the period under study. This study provides for the first time empirical evidence that covering all three efficiency concepts, namely cost, revenue, and profit efficiency is completely missing from the literature. By calculating these efficiency concepts, we can observe the efficiency levels of the domestic and foreign Islamic banks. In addition, by comparing both cost and profit efficiency, we can identify the influence of the revenue efficiency on the banks’ profitability.

Keywords

Islamic Finance, Islamic Banks, Revenue Efficiency, Data Envelopment Analysis.

Introduction

Islamic banking is a financial system whose main objective is to achieve the teachings of the Qur’an (central religious text of Islam). Islamic law reflects the commandments of God, and organizes all aspects of Muslim life, and therefore directly involved in Islamic finance, spirituality and social justice. Based on the theory of Islamic banking on the concept that is strictly forbidden in the interest of Islam and the teachings of Islam which provide the necessary guidance is based on the work of the banks. The fundamental principle that has guided my work in Islamic banking is that, despite the ban on trade in interest in Islam, and encourages and profit. Traditional bank uses the interest rate mechanism for the implementation of its financial operations. It was developed by Muslim scholar’s completely different model of banking services that do not use, but the interest is based on change in the distribution of income for purposes of financial intermediation. The basic principle of Islamic law is that exploitation contracts or contracts of unfair risk or speculation are not permissible. Under Islamic banking, and all partners involved in financial transactions involved in the risk and the gain or loss on the project and not get a return on a predetermined. This direct relationship between investment and profit is the main difference between Islamic and conventional banks, which has a main objective to maximize shareholder wealth (Sufian Kamarudin & Noor, 2014).

Given the rapid development of the Islamic banking sector, it is reasonable to expect that the performance of Islamic banks has become the center of atten- tion among Islamic bank managers, stakeholders, policymakers, and regulators. Berger and Humphrey (1997) point out that studies focusing on the efficiency of financial institutions have become an important part of banking literature since the early 1990s. Furthermore, Berger et al., (1993) suggest that if banks are efficient, they could expect improvement in profitability levels, better prices and service quality for consumers, and greater amounts of funds intermediated. Besides, the efficiency in the banking sectors could significantly increase the credit growth that may lead to the economic development with the proper manage and well sustain during global financial crisis (Ivanović, 2016; Lakić et al., 2016).

In fact, the general concept of efficiency covers three components; namely, cost, revenue and profit efficiency (Bader et al., 2008). Evidence on bank efficiency could be produced by discovering these three types of efficiency concept. Howev- er, few studies have examined the comprehensive efficiency that consists of these three components. Most previous studies have mainly focused on the efficiency of cost, profit or both (Bader et al., 2008).

Studies on bank efficiency which ignore the revenue side have been criticized (Bader et al., 2008). It is mainly because most of the studies have only revealed the levels of cost efficiency which are higher than the profit efficiency, but they have not identified the causes. According to Chong et al., (2006) banks desire to maximize the profit to maximize the shareholders’ value or wealth. However, the main problem that contributes to the lower profit efficiency comes from revenue inefficiency (Sufian & Kamarudin, 2014). Sufianet al., (2013) found that the inefficient revenue affected the difference between cost and profit efficiency. Despite considerable developments in the Islamic banking sector worldwide, little attention has been given to the efficiency of its operations.

Therefore, instead of focusing on the Indonesian Islamic banking sector`s profit efficiency alone, it is better to compare it with cost efficiency as well in order to identify the existence of revenue efficiency. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first empirical study that has examined the comprehensive efficiencies concept including the revenue efficiency on the Indonesian Islamic banking sector. In fact, the main focus of this study is to investigate whether the revenue efficiency represents the most important efficiency measure that, in turn, could lead to higher or lower profit efficiency levels in the Indonesian Islamic banking sector.

Furthermore, this paper investigates whether the bank specifics and macroeconomic determinants influence revenue efficiency of overall Islamic banks and, specifically, of domestic Islamic banks operated in Indonesia. For that purpose, we employ the nonparametric Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) method to analyze the cost, revenue, and profit efficiencies of the universe of Indonesian Islamic banks over the period of 2009 to 2018 in the first stage of analysis. The preferred method allows us to distinguish between three different types of efficiency, namely cost, revenue, and profit efficiencies. Furthermore, we perform a series of parametric (t-test) and non-parametric (Mann- Whitney [Wilcoxon] and Kruskall-Wallis) tests to examine whether the domestic and foreign Islamic banks are drawn from the same population. Meanwhile, in the second stage of analysis we employed a pooled (OLS) and panel (GSL) regression analysis framework consisting of Fixed Effect Model (FEM) and Random Effect Model (REM) run by the Hausman test to analyze the determinants of revenue efficiency of Islamic banks in the sample.

Previous Studies

Previous studies examined the cost and profit efficiency in conventional banks. These studies discovered that different levels between cost and profit efficiency are caused by the inefficiency on the revenue side (e.g. Rogers, 1998; Berger and Mester, 2003). Revenue can be defined as how effectively a bank sells its outputs. Maximum revenue is obtained as a result of producing the out- put bundle efficiently. In fact, revenue efficiency is decomposed into technical and allocative efficiency which are related to managerial factors and is regularly associated with regulatory factors (Isik and Hassan, 2002). Posits that in order to ascertain revenue efficiency, banks should focus on both technical efficiency (managerial operating on the production possibilities) and allocative efficiency (bank producing the revenue maximizing mix of outputs based on certain regulations).

Another way to improve the revenue efficiency proposed by several studies is for banks to produce higher quality services and charge higher prices and struggles to avoid any improper choice of inputs and outputs quantities and mispricing of outputs (Rogers, 1998). The revenue inefficiency could be well identified via the profit function because this function combines both cost and revenue efficiency to evaluate profit efficiency. Revenue efficiency would totally affect profit efficien- cy even when cost efficiency is high. In essence, revenue efficiency would be the major factor that influences profit efficiency. Berger and Humphrey (1997), Bader et al. (2008) and Kamarudin et al. (2016) state that there have been limited studies done on revenue efficiency of banks. Furthermore, if these studies are narrowed down to the Islamic banking industry, there is paucity of studies that looked into the difference in the revenue efficiency of the domestic and foreign Islamic banks.

Kamarudin et al. (2014a) find that revenue efficiency seems to play the main fac- tor leading to lower or higher profit efficiency levels only on Islamic banks in the GCC region. Furthermore, Islamic and conventional banks in the GCC coun- tries tend to operate at constant return to scale (CRS) or decrease return to scale (DRS), while small banks tend to operate at CRS or increase return to scale (IRS). Kamarudin et al. (2014b) suggests that asset quality, non-traditional activities, management quality, and liquidity significantly influence the improvement in revenue efficiency of Islamic banks in the GCC countries. The improvement in revenue efficiency of the Islamic banks in the GCC was also influenced by inflation and concentration ratio of the three largest banks operating in the national banking sector.

The above literature reveals the following research gaps. First, the majority of these studies have mainly concentrated on the conventional banking sectors of the western and developed countries. Second, empirical evidence on the developing countries, particularly the Islamic banking sector, is scarce. Finally, virtually nothing has been published on the cost, revenue, and profit efficiency and its determinants in the Islamic banking sector. In the light of these knowledge gaps, the present paper seeks to provide new empirical evidence on the cost, revenue, and profit efficiency and its determinants in the Indonesian Islamic banking sector.

Research Methodology

The level of revenue efficiency is measured by using the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) method. The DEA method constructs a frontier of the observed input- output ratios by linear programming techniques. The linear substitution is pos- sible between observed input combinations on an isoquant (the same quantity of output is produced while changing the quantities of two or more inputs) that was assumed by the DEA method. Charnes et al. (1978) were the first to introduce the term DEA to measure the efficiency of each decision making units (DMUs), obtained as a maximum of a ratio of weighted outputs to weighted inputs. The more the output produced from given inputs the more efficient is the production.

There are six main reasons why this study adopts the DEA method to measure the efficiency of the banks as the DMU. First, each DMU is assigned a single ef- ficiency score that allows ranking amongst the DMUs in the sample. Second, the DEA method highlights the areas of improvement for each single DMU such as either the input has been excessively used or output has been under produced by the DMU (so they could improve on their efficiency). Third, there is a possibility of making inferences on the DMU’s general profile. The DEA method allows for the comparison between production performance of each DMU to a set of efficient DMUs (called the reference set). The owner of the DMUs may be interested to know which DMU frequently appears in this set. A DMU that appears more than others in this set is called the global leader. Apparently, the DMU owner may obtain a huge benefit from this information especially in positioning its entity in the market. Fifth, the DEA method does not need standardization, therefore allowing researchers to choose any kind of input and output of manage- rial interest (arbitrary), regardless of different units of measurement. Finally, the DEA method works fine with small sample sizes.

This study employs efficiency estimates under the variable returns to scale (VRS) assumption. The VRS assumption was proposed by Banker et al., (1984). The BCC model (VRS) extends the CCR model which was first proposed by Charnes et al., (1978) by relaxing the constant return to scale (CRS) assumption. The resulting BCC model was used to assess the efficiency of DMUs characterized by VRS assumption. The VRS assumption provides the measurement of pure technical efficiency (PTE). PTE measures the efficiency of DMUs without being contaminated by scale effects. Hence, results derived from the VRS assumption provide more reliable information on DMUs` efficiency compared to the CRS assumption.

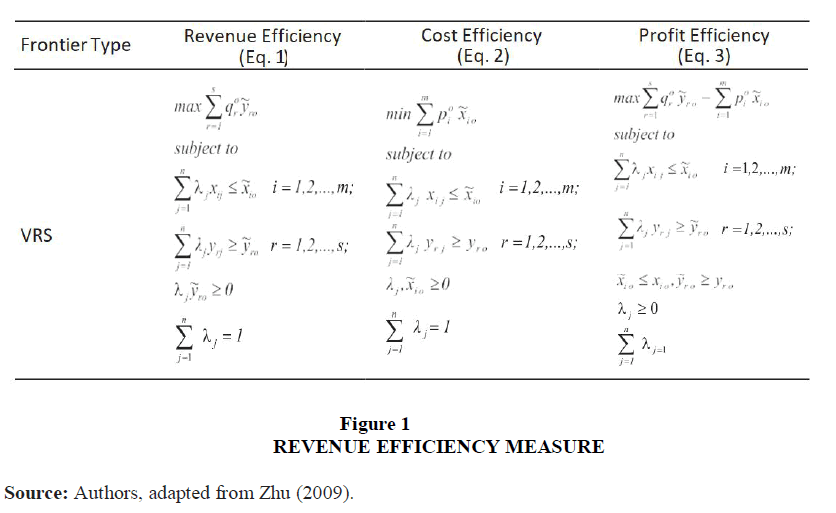

The revenue, cost, and profit efficiency models are given in Equations (1) – (3), respectively. As observed, the revenue, cost, and profit efficiency scores are bounded within the 0 and 1 range. By calculating the three efficiency measures (e.g. revenue, cost, and profit), we will be able to observe a more robust result for the domestic and foreign Indonesian Islamic banks over the period under study. However, the present study will give greater emphasis on the revenue efficiency measure compared to the other efficiency measures (e.g. cost and profit) in Figure 1.

where:

S is the output observation, m is the input observation, r is the sthoutput, i is the mthinput, qor is the unit price of output r of DMU0, poi is the unit price of input i of DMU0, is the rthoutput that maximize revenue for DMU0, is the ithinput that minimize cost for DMU0, yro is the rthoutput for DMU0, xio is the ithinput for DMU0, n is the DMU observa- tion, j is the nthDMU, λj is the non-negative scalars, yrj is the sthoutput for nthDMU, xij is the mthinput for nth DMU.

The Input And Output Variables In Dea

According to Cooper et al. (2002), there is a rule required to be complied with in order to select the number of inputs and outputs. A simple rule of thumb which could provide guidance can be given as:

n ≥ max {m * s, 3 (m+s)} (Eq. 4)

where

n is the number of DMUs

m is the number of inputs

s is the number of outputs.

Given the underdevelopment of capital markets, the importance of banks as financial intermediaries is more prevalent in developing economies like Indonesia. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the efficiency of banks in terms of their intermediation function is crucial as an effective channel for business funding. In this vein, banks play an important economic role in providing financial in- termediation by converting deposits into productive investments in developing countries. The banking sectors of developing countries have also been shown to perform the critical role in the intermediation process by influencing the level of money stock in the economy with their ability to create deposits.

Following Bader et al. (2008), Sufian & Kamarudin (2014), Kamarudin et al. (2015), Kamarudin et al. (2017) and Singh & Bansal (2017) among others, the present study employs the intermediation approach which views banks as an intermediary between savers and borrowers. Accordingly, two inputs, two input prices, two outputs, and two output prices variables were chosen. The two input vector variables consist of x1: deposits and x2: labour. Accordingly, the input prices are w1: price of deposits and w2 price of labour. The two output vectors are y1: loans and y2: income. Correspondingly, the two output prices consist of r1: price of loans and r2: price of investment. The summary of data used to construct the efficiency frontiers are given in Table 1.

| Table 1 Summary Statistics of the Output and Input Variables in the Dea Model (Usd Mil) | ||||||||

| Variables | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | Standard Deviation | ||||

| DIB | FIB | DIB | FIB | DIB | FIB | DIB | FIB | |

| Output | ||||||||

| y1 | 10,692.4 | 2,809.3 | 0.7 | 347.5 | 295,255.8 | 15,177.7 | 53,749.2 | 2,710.5 |

| y2 | 4,735.5 | 800.0 | 9.3 | 41.8 | 136,571.3 | 4,974.3 | 24,900.2 | 879.3 |

| Output Price | ||||||||

| r1 | 997.4 | 213.4 | 0.5 | 34.5 | 28,124.3 | 790.7 | 5,123.6 | 166.0 |

| r2 | 108.8 | 5.1 | -1.0 | -26.3 | 3,131.3 | 27.5 | 570.9 | 7.8 |

| Input | ||||||||

| x1 | 21,737.3 | 4,309.8 | 11.9 | 564.3 | 613,873.9 | 17,995.9 | 111,839.1 | 3,338.5 |

| x2 | 261.9 | 17.7 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 7,543.7 | 139.8 | 1,375.3 | 25.9 |

| Input Price | ||||||||

| w1 | 501.4 | 91.1 | 0.1 | 11.0 | 14,263.3 | 351.1 | 2,599.3 | 68.7 |

| w2 | 27,138.4 | 4,777.1 | 82.5 | 37.6 | 768,511.3 | 21,826.9 | 140,026.1 | 3,922.3 |

In fact, the selection of the inputs and outputs could be difficult in the evaluation of bank efficiency to be used in the first stage of DEA analysis. There is ‘no perfect approach’ in the selection of the bank inputs and outputs (Bader et al., 2008). Berger & Humphrey (1997) also found that there are some restrictions on the type of variables since there is a need for comparable data and to minimise pos- sible biases due to different accounting practices in the collection of the variables. In fact, they stated that even in the same country, different banks might apply different accounting standards. The results of the efficiency scores for each study on the bank efficiency will be affected due to the selection of variables. Thus, the DEA method requiring bank inputs and outputs as the choice is always an arbitrary issue

(Berger & Humphrey, 1997). Since the issue selecting approaches is still arbitrary, this study decided to use intermediation approach because we assume bank is more suitable to be classified as intermediary entity.

Multivariate Panel Regression Analysis

The second objective of this study is to identify the potential bank specific and macroeconomic determinants which influence the revenue efficiency of Indonesia Islamic banks. To examine the relationship between the revenue efficiency of Indonesian Islamic banks and the explanatory variables, we employ a multivariate regression analysis defined as follows for observation (bank) i.

yit = βxit + εit i = 1,...,N, (Eq. 5)

yit is the efficiency of bank, xit is the matrix of the explanatory variables, β is the vector of coefficients, εit is a random error term representing statistical noise, i is a number of bank, t is a year and N is the number of observations in the data set. By using the revenue efficiency scores as dependent variable, we extend Equation (5) and estimate the following regression model:

LNθjt = αt + β(LNTAjt + LNLLRGLjt + LNETAjt + LNBDTDjt + LNLOANSTAjt + LNNIETAjt + LNGDPjt + LNINFLjt + DOM_IBj + LNBDTDjt*DOM_IBj + LNLOANSTAjt *DOM_IBj + LNNIETAjt *DOM_IBj + LNGDPjt *DOM_IBj + LNINFL*DOM_IBj) + εjt (Eq.6)

Where:

LNθjt Natural logarithm of revenue efficiency

LNTA Natural logarithm of total assets

LNLLRGL Natural logarithm of Loan loss reserve to gross loan

LNETA Natural logarithm of equity to total assets

LNBDTD Natural logarithm of bank’s deposit over total deposit

LNLOANSTA Natural logarithm of total loan over total assets

LNNIETA Natural logarithm of non-interest expense over total assets

LNGDP Natural logarithm of gross domestic product

LNINFL Natural logarithm of customer prices index

DOM_IB Natural logarithm of dummy domestic Islamic bank

j Number of bank

t Number of year

α Constant term

β Vector of coefficients

εjt Normally distributed disturbance term

The Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression method (also known as pooled model) is employed in the second stage regression analysis to examine the rela- tionship between revenue efficiency and bank specific and macroeconomic con- ditions determinants. Furthermore, to avoid severe multicollinearity problems, we adopt a step-wise regression models.

Nevertheless, before the results are totally based on the OLS estimator method, the Breusch and Pagan Lagrangian multiplier test need to be execute in order to identify either the data suitable to be pooled or panel. The pooled data shows that the OLS is the best estimation method to be used, however, the GLS estima- tion method is the best method to deal with the panel data. Thus, if the p-value is significant at 5% level, the panel data (GLS) is more appropriate than pooled data (OLS).

Gujarati (2002) mentioned three kinds of advantages in using panel regression. Firstly, panel data make the data more informative with variability, reduce col- linearity among the variables, they are efficient and give more degree of freedom to the data. Secondly, panel data could construct better detection and measure- ment of effects that simply could not be observed in pure cross-sectional or pure time series data. Thirdly, panel data provide the data to be available into several thousand units and this can minimise the bias that might result if individuals or firms level data are divided into broad aggregates.

Gujarati (2002) pointed out several advantages to using panel data that show sev- eral estimation and inference problems. Since such data involve both cross-sec- tion and time dimensions, problems that plague cross-sectional and time series data (such as heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation) need to be addressed. There exist some additional problems such as cross-correlation in individual units at the same point in time. So, several estimation techniques are used to address one or more of these problems. The two most prominent ones are the fixed effects model (FEM) and the random effects model (REM). In the FEM, the intercept in the regression model is allowed to differ among individuals in recognition to the fact that each individual or cross-sectional unit may have some special character- istics of its own. Meanwhile, the REM assumed that the intercept of an individual unit is a random drawing from a much larger population with a constant mean value. If it is assumed that the error component β and X’s regressors are uncor- related, the REM may be more suitable, whereas if β and X’s are correlated, the FEM may be appropriate.

The Hausman test can be used to differentiate between the FEM and the REM. The null hypothesis underlying the Hausman test is that the FEM and REM estimators do not differ significantly. The test statistics developed by Hausman has an asymptotic Chi-Square (X²) distribution. If null hypothesis is rejected (at 1% to 5% significant levels only), the FEM may be more appropriate to be used com- pared to the REM. But, if null hypothesis is failed to reject or is significant at only 10%, the REM is more suitable to be used.

Furthermore, the panel data is most suitable to be used with the Generalized Least Square (GLS) method. Gujarati (2002) suggests that GLS may overcome the heteroscedasticity, resulted from utilising financial data with differences in sizes. Due to the fact that the sample employed in this study consists of small and large banks, differences in sizes of the observations are expected to be observed.

The usual practice of econometrics modelling assumes that error is constant over all time periods and locations due to the existence of homoscedascity. Neverthe- less, problems could arise which lead to heteroscedasticity issues as variance of the error term produced from regression tend not to be constant, which is caused by variations of sizes in the observation. Therefore, the estimates of the depend- ent variable will be less predictable (Gujarati, 2002).

Using the OLS estimation will solve the problem since it adopts the minimis- ing sum of residual squares condition. The OLS allows all errors to receive equal importance no matter how close or how wide the individual error spread is from the sample regression function. On the other hand, GLS minimises the weighted sum of residual squares. In GLS estimation, the weight consigned to each error term is relative to its variance of the error term. Error term that comes from a population with large variance of error term will get relatively large weight in minimising residual sum of squares (RSS). Consequently, if a problem of nonconstant error arises, GLS is able to produce estimators in BLUE version because it accounts for such a problem by assigning appropriate weight to different error terms, which in turn, produces the ideal constant variable (Gujarati, 2002).

Accordingly, 11 regression models are estimated to examine the relationship between the revenue efficiency of Indonesian Islamic banks and the potential determinant variables. Table 2 presents detail description of the variables used in the regression models.

| Table 2 Description Statistic of Bank Specific, Macroeconomic, and Dummy Variables | |||

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dv. | Note |

| Bank Specific Variables | |||

| LNTA | 7.8631 | 1.2077 | A proxy of bank size computed as the natural logarithm of total bank assets. |

| LNLLRGL | 1.1229 | 0.5623 | A proxy of asset quality computed as the natural logarithm of loans loss reserved over gross loans. |

| LNETA | 2.1886 | 0.6397 | A proxy of capitalization computed as the natural logarithm of equity over total assets. |

| LNBDTD | 0.6823 | 1.0675 | A proxy of bank market power computed as the natural logarithm of bank’s deposit over total deposit. |

| LNLOANSTA | 3.8707 | 0.5869 | A proxy of liquidity computed as the natural logarithm of the ratio of total loans divided by total assets. |

| LNNIETA | 0.7451 | 0.6420 | A proxy of management quality computed as the natural logarithm of the ratio of non-interest expenses divided by total assets. |

| Macroeconomics Variables | |||

| LNGDP | 5.0578 | 0.0739 | A proxy of gross domestic product computed as the natural logarithm of the national gross domestic products |

| LNINFL | 4.7920 | 0.0331 | A proxy of inflation computed as the natural logarithm of the inflation rates. |

| Dummy Variable | |||

| DOM_IB | 0.6629 | 0.4754 | DOM_IB is a binary variable that takes a value of 1 for domestic Islamic bank, and it is 0 otherwise. As expected, this coefficient is to be in positive sign which indicates that the banking sector has been relatively more revenue efficient in Indonesian domestic Islamic banks. |

Results and Discussion

Before proceeding with the DEA results, as suggested by Cooper et al. (2002), this study first test the rule of thumb on the selection of inputs and outputs variables. Since the total number of DMUs (17 banks) in this study is more than the num- ber of input and output variables (2 inputs x 2 outputs @ 3 [2 inputs + 2 outputs]), the selection of variables is valid and allows the efficiencies of DMUs to be meas- ured. By calculating the three efficiency measures (e.g. revenue, cost, and profit), we obtain robust efficiency results for both domestic and foreign Islamic banks. Table 3 illustrates the revenue efficiency estimates along with the cost and profit efficiency measures for both the domestic and foreign Islamic banks.

| Table 3 Cost, Revenue and Profit Efficiencies for Indonesian Domestic and Foreign Islamic Banks | |||||||

| Domestic Islamic Banks | Foreign Islamic Banks | ||||||

| DMU Name | VRS RE | VRS CE | VRS PE | DMU Name | VRS RE | VRS CE | VRS PE |

| Bank Syariah Mandiri | 0.4975 | 0.5059 | 0.2783 | Al-Rajhi Bank | 0.7203 | 0.8554 | 0.6338 |

| Muamalat Bank | 0.9868 | 0.9853 | 1.0000 | Asian Finance Bank | 1.0000 | 0.9216 | 1.0000 |

| Bank Indonesia | 0.9408 | 0.8400 | 1.0000 | HSBC Amanah | 0.9347 | 0.9559 | 0.9186 |

| Bank Islam Indonesia | 0.5014 | 0.6973 | 0.4098 | Kuwait Finance House | 0.6426 | 0.7005 | 0.5065 |

| PT Bank Maybank | 0.5943 | 0.6271 | 0.4817 | OSBC AL-Amin | 0.7673 | 0.6877 | 0.6975 |

| Hong Leong Bank | 0.5162 | 0.6322 | 0.4227 | Standard Saadiq | 1.0000 | 0.6701 | 1.0000 |

| CIMB Islamic Bank | 0.7820 | 0.7807 | 0.6608 | ||||

| Bank BCA Syariah | 0.5855 | 0.5997 | 0.3578 | ||||

| Bank Kalbar Syariah | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||||

| Bank Permata Syariah | 0.8070 | 0.8729 | 0.7522 | ||||

| Bank Sinarmas Syariah | 0.6188 | 0.6538 | 0.5152 | ||||

| Mean | 0.7118 | 0.7450 | 0.6253 | Mean | 0.8442 | 0.7986 | 0.7927 |

Efficiency Of Domestic Islamic Banks

Table 3 shows the mean revenue, cost and profit efficiency of the Indonesian domestic Islamic banks of 71.18%, 74.50% and 62.53% respectively. In other words, the domestic Indonesian Islamic banks have been inefficient in producing outputs by using the same input (revenue inefficiency) and by not fully using the inputs efficiently to produce the same outputs (cost inefficiency). Banks are said to have slacked if they fail to fully minimize their cost and maximize their revenue (profit inefficiency). The results clearly indicate that the levels of cost, revenue, and profit inefficiency of the domestic Islamic banks are 28.82%, 25.50% and 37.47% respectively.

Regarding revenue efficiency, the average Islamic bank could only generate 71.18% of revenues, less than what it was initially expected to generate. Hence, revenue is lost by 28.82%, indicating that the average Islamic bank loses an opportunity to receive 28.82% more revenues given the same amount of resources, or it could have produced 28.82% of its outputs given the same level of inputs. For cost efficiency, the results indicate that on average Indonesian domestic Islamic banks have utilized only 74.50% of the resources or inputs to produce the same level of outputs. In other words, on average, Indonesian domestic Islamic banks have wasted 25.50% of its inputs, or it could have saved its inputs to produce the same level of outputs. It is also worth noting that, on average, Indonesian domestic Islamic banks have been more cost efficient in utilizing their inputs compared to their ability to generate revenues and profits

Obviously, the inefficiency is on the revenue side, which is followed by the profits side. Similarly, the average Islamic bank could have earned 62.53% of what was available and lost the opportunity to make 37.47% more profits from the same level of inputs. Even though the cost efficiency is reportedly highest in the do- mestic Islamic banks, the revenue efficiency is found to be lower, and this led to higher revenue inefficiency. When both efficiency concepts (revenue and cost) are compared, the higher revenue inefficiency seems to have contributed to the higher profit inefficiency levels.

Efficiency Of Foreingn Islamic Banks

The empirical findings presented in Table 3 seem to suggest that the Indonesian foreign Islamic banks have exhibited mean cost, revenue, and profit efficiency of 79.86%, 84.42% and 79.27%, respectively. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that, on average, Indonesian foreign Islamic banks have been found to be more efficient compared to their domestic Islamic bank peers. For revenue efficiency, the average foreign Islamic bank could generate 84.42% of revenues than it was expected to generate. Hence, the average foreign Islamic bank lost an opportunity to receive 15.58% more revenue, given the same amount of resources.

As for the cost efficiency, the results seem to suggest that the average foreign Islamic bank have utilized only 79.86% of the resources or inputs in order to produce the same level of output. In other words, on average, foreign Islamic banks have wasted 20.14% of its inputs, or it could have saved 20.1% of its inputs to produce the same level of outputs. Therefore, there was substantial room for significant cost savings for the foreign Islamic banks if they employ their inputs efficiently. Noticeably, the highest level of inefficiency is on the cost side, followed by the profit side. Similarly, the average foreign Islamic bank could have earned 79.27% of what was available, and lost the opportunity to make 20.73% more profits when utilizing the same level of inputs.

Robusteness Checks: Parametric And Non-Parametric Tests

After examining the results derived from the DEA method, the issue of interest now is whether the difference in the cost, revenue, and profit efficiency of the do- mestic and foreign Islamic banks is statistically significant. The Mann-Whitney [Wilcoxon] is a relevant test for two independent samples coming from popu- lations having the same distribution. The most relevant reason is that the data violate the stringent assumptions of the independent group’s ttest. In what fol- lows, we perform the non-parametric Mann-Whitney [Wilcoxon] test along with a series of other parametric (t-test) and non-parametric Kruskall-Wallis tests to obtain more robust results.

The results are given in Table 4. The empirical findings show that during the period under study,nh the results from the parametric t-test indicate that do- mestic Islamic banks have exhibited a lower mean revenue efficiency (0.7119 < 0.8442), cost efficiency (0.7450 < 0.7986), and profit efficiency (0.6253 < 0.7927) compared to their foreign Islamic bank peers (statistically significantly different at the 1% level except for cost efficiency). The results from the parametric t-test are further confirmed by the non-parametric Mann-Whitney (Wilcoxon) and Kruskall-Wallis tests.

| Table 4 Summary of Parametric and Non-Parametric Tests on Indonesiandomestic and Foreign Islamic Banks | ||||||

| Test Groups | ||||||

| Parametric test | Non-parametric test | |||||

| Indiduals Tests | t-test | Mann-Whitney | Kruskall- Wallis | |||

| [Wilcoxon Rank-Sum] test | Equality of Populations test | |||||

| Hyphotesis | Median Domestic = Median Foreing | |||||

| Test Estatistics | t (Prb>t) | z (Prb>z) | x2 (Prb> x2) | |||

| Mean | t | Mean | z | Mean | x2 | |

| Revenue Efficiency | ||||||

| Domestic Islamic Banks | 0.7119 | -2.7259*** | 37.4909 | -2.8271*** | 37.4909 | 7.9925*** |

| Foreign Islamic Banks | 0.8442 | - | 53.1000 | - | 53.1000 | - |

| Cost Efficiency | ||||||

| Domestic Islamic Banks | 0.7450 | -1.1311 | 41.0909 | -0.9729 | 41.0909 | 0.9466 |

| Foreign Islamic Banks | 0.7986 | - | 46.5000 | - | 46.5000 | - |

| Profit Efficiency | ||||||

| Domestic Islamic Banks | 0.6253 | -2.5509** | 38.4636 | -2.3515** | 38.4636 | 5.5326** |

| Foreign Islamic Banks | 0.7927 | - | 51.3167 | - | 51.3167 | - |

In conclusion, the domestic Islamic banks operating have been relatively inef- ficient compared to their foreign Islamic bank on all three efficiency measures (e.g. revenue efficiency (71.19% vs. 84.42%), cost efficiency (74.50% vs. 79.86%), and profit efficiency (62.53% vs. 79.27%)). The results seem to suggest that do- mestic Islamic banks generate less revenue and profit, but incur relatively higher cost compared to their foreign Islamic bank counterparts implying high wastage of inputs among Islamic banks operating in the Malaysian banking sectors. In essence, the low (high) level of profit efficiency of the domestic (foreign) Islamic banks is due to lower (higher) revenue efficiency or higher (lower) inefficiency level from the revenue side. The significant results on lower levels of revenue efficiency in domestic Islamic banks indicate that the revenue efficiency could in- fluence the lower profitability of the banks due to lower profit efficiency levels. Therefore, the revenue efficiency represents the most important efficiency meas- ure that, in turn, could lead to higher profit efficiency levels.

Determinants of Revenue Efficiency

In essence, the results from the first stage indicate that the revenue efficiency of the domestic Islamic banks has been lower compared to their foreign Islamic bank peers. While, in the second stage, the main objective is to identify the internal (bank specific) and external (macroeconomic) factors which could specifically improve the revenue efficiency of the Indonesian Islamic banking sector. To do so, we estimate 11 multivariate regression models which are presented in columns (1) to (11) of Table 5 using the OLS method. For Model 1, which is the baseline regression model, the regression model includes all six basic bank specific deter- minant variables namely bank size (LNTA), asset quality (LNLLRGL), capitaliza- tion levels (LNETA), bank market power (LNBDTD), liquidity (LNLOANSTA), and management quality (LNNIETA).

| Table 5 Multivariate Regression Analysis Models Under Ordinary Least Square | |||||||||||

| Variable | Models | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| Constant | -4.896 | -1.644 | -0.014 | -0.350 | -0.558 | -0.149 | 6.242 | 0.608 | 7.021 | -0.036 | -1.265 |

| (1.022) | (4.707) | (4.995) | (4.984) | (5.003) | (4.976) | (4.247) | (4.186) | (4.359) | (4.977) | (4.862) | |

| Determinant Variables | |||||||||||

| LNTA | 0.9040 | 1.112 | 1.219 | 1.213 | 1.159 | 1.21 | 1.394 | 1.041 | 1.499 | 1.221 | 1.128 |

| (0.186) | (0.376) | (0.391) | (0.397) | (0.384) | (0.390) | (0.393) | (0.332) | (0.399) | (0.391) | (0.381) | |

| LNLLRGL | 0.082 | 0.104 | 0.113 | 0.110 | 0.163 | 0.118 | 0.099 | 0.206* | 0.063 | 0.113 | 0.107 |

| (0.104) | (0.109) | (0.110) | (0.110) | (0.141) | (0.111) | (0.093) | (0.099) | (0.091) | (0.110) | (0.111) | |

| LNETA | 0.222 | 0.185 | 0.149 | 0.155 | 0.157 | 0.177 | 0.095 | 0.011 | 0.092 | 0.148 | 0.177 |

| (0.136) | (0.151) | (0.156) | (0.156) | (0.158) | (0.152) | (0.126) | (0.140) | (0.125) | (0.156) | (0.154) | |

| LNBDTD | -1.111 | –1.33 | –1.399 | –1.389 | –1.351 | –1.402 | –1.585 | –1.138 | –1.607 | –1.400 | –1.341 |

| (0.198) | (0.394) | (0.400) | (0.401) | (0.397) | (0.401) | (0.392) | (0.350) | (0.393) | (0.400) | (0.398) | |

| LNLOANSTA | 0.299 | 0.346 | 0.357 | 0.349 | 0.344 | 0.371 | 0.56 | 0.165 | 0.519** | 0.357** | 0.354* |

| (0.094) | (0.123) | (0.123) | (0.123) | (0.124) | (0.126) | (0.119) | (0.117) | (0.118) | (0.123) | (0.126) | |

| LNNIETA | -0.23 | –0.254 | –0.258 | –0.256 | –0.244 | –0.264 | –0.161* | –0.242* | –0.181* | –0.257 | –0.251* |

| (0.090) | (0.097) | (0.097) | (0.097) | (0.098) | (0.097) | (0.075) | (0.085) | (0.073) | (0.097) | (0.098) | |

| Macroeconomic Variables | |||||||||||

| LNGDP | -0.748 | -1.105 | -1.042 | -0.964 | -1.084 | –2.285 | -1.008 | –2.49* | -1.102 | -0.824 | |

| (1.077) | (1.137) | (1.139) | (1.129) | (1.136) | (1.031) | (0.952) | (1.055) | (1.134) | (1.106) | ||

| LNINFL | 0.012 | 0.031 | 0.028 | 0.025 | 0.030 | 0.094 | 0.022 | 0.100 | 0.031 | 0.042 | |

| (0.079) | (0.082) | (0.082) | (0.082) | (0.082) | (0.070) | (0.070) | (0.070) | (0.082) | (0.117) | ||

| DOM_IB | -0.060 | ||||||||||

| (0.061) | |||||||||||

| Interaction Variables | |||||||||||

| LNTA*DOM_IB | -0.013 | ||||||||||

| (0.016) | |||||||||||

| LNLLRGL*DOM_IB | -0.081 | ||||||||||

| (0.121) | |||||||||||

| LNETA*DOM_IB | -0.056 | ||||||||||

| (0.060) | |||||||||||

| LNBDTD*DOM_IB | 0.0795 | ||||||||||

| (0.030) | |||||||||||

| LNLOANSTA*DOM_IB | 0.661 | ||||||||||

| (0.157) | |||||||||||

| LNNIETA*DOM_IB | 0.065 | ||||||||||

| (0.025) | |||||||||||

| LNGDP*DOM_IB | -0.010 | ||||||||||

| (0.010) | |||||||||||

| LNINFL*DOM_IB | -0.040 | ||||||||||

| (0.113) | |||||||||||

| Models | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| R2 | 0.489 | 0.494 | 0.502 | 0.499 | 0.497 | 0.501 | 0.645 | 0.613 | 0.644 | 0.502 | 0.495 |

| Adj R2 | 0.438 | 0.425 | 0.425 | 0.422 | 0.419 | 0.424 | 0.590 | 0.553 | 0.589 | 0.425 | 0.416 |

| Durbin Watson | 0.590 | 0.534 | 0.532 | 0.529 | 0.525 | 0.528 | 0.747 | 0.599 | 0.747 | 0.532 | 0.525 |

| F-statistic | 9.719 | 7.189 | 6.492 | 6.426 | 6.379 | 6.473 | 11.726 | 10.195 | 11.676 | 6.499 | 6.309 |

Model 2 considers the macroeconomic control variables such as the gross do- mestic product (LNGDP) and inflation rate (LNINFL), while the bank specific variables are kept in the regression model. In the regression Model 3, we include a binary dummy variable (DOM_IB) to examine the relationship between revenue efficiency and the Malaysian domestic Islamic banks. Models 4 to 11 represent focused models adopted to identify the potential determinants of Indonesian domestic Islamic banks’ revenue efficiency. All the bank specific and macroeco- nomic variables are retained in these models (Model 4 to Model 11). In addition, we include several interaction variables namely LNTA* DOM_IB, LNLLRGL* DOM_IB, LNETA* DOM_IB, LNBDTD* DOM_IB, LNLOANSTA* DOM_IB, LNNIETA* DOM_IB, LNGDP* DOM_IB and LNINFL* DOM_IB.

The main purpose of these interaction variables is to further examine the impact of the bank specific and macroeconomic factors to the revenue efficiency spe- cifically on the Indonesian domestic Islamic banks. These interaction variables are expected to have mixed coefficient signs. The positive (negative) coefficient of these interaction variables indicates that these determinants could significantly increase (decrease) the bank revenue efficiency specifically on domestic Islamic banks.

Table 5 shows the results from the multivariate regression models using the OLS method. The equations are based on 85 bank year observations during the period of 2006 to 2015. The results show that the relationship between revenue efficiency and bank size (LNTA) is positive (statistically significant at the 1% level). The results clearly indicate that the larger Islamic banks tend to exhibit a higher level of revenue efficiency. The result is consistent with Al-Sharkas et al. (2008) and Cornett et al. (2006) among others. Large banks tend to report improvements in profit efficiency compared to their small and medium bank peers because higher costs incurred tend to be compensated by higher revenues received via quality services. Besides, large banks appear to be better able to capitalize on revenue enhancement and have better cost cutting opportunities compared to the small and medium sized banks. Nevertheless, Igbinosa et al. (2017) suggest contrary since too much investment in total assets (large size) without guarantee of positive re- turn could waste the resources that may lead to inefficiency in the banking sector.

The empirical findings presented in Table 5 indicate that bank market power (LNBDTD) has negative influence on the revenue efficiency of Indonesian Islamic banks. We also find that the impact of asset quality (LNLLRGL) is only significant when we control for the macroeconomic variables (consistent with Dushku, 2016) and domestic Islamic banks (DOM_IB) in regression Models (8).

During the period under study, we do not find statistically significant impact of capitalization (LNETA) on the revenue efficiency of the Indonesian Islamic banks. During the period of study, we also find that the impact of liquidity (LNLOANSTA) is positive and is statistically significant at the 5% level or better. The findings im- ply that banks with higher loans-to-asset ratios tend to be more profitable. There- fore, bank loans seem to be more highly valued than alternative bank outputs such as securities and investment in the case of the Indonesian Islamic banking sector.

On the other hand, we find that management quality (LNNIETA) exerts a nega- tive and statistically significant impact on the revenue efficiency of the Indonesian Islamic banks. A lower LNNIETA ratio represents good management quality attributed to efficient bank managers in managing expenses resulting in the improvement of profitability. Low measure of cost efficiency is a signal of poor senior management practices, which apply to input-usage and day-to-day operations.

Robusteness Checks: Controlling For Domestic Islamic Banks

In order to check for the robustness of the results, we have performed a number of sensitivity analyses. First, the domestic and foreign Islamic banks may react differently to the same efficiency determinants. In what precedes, we seek to identify factors which influence the revenue efficiency of the Malaysian domestic Islamic banks. To do so, we interact all of the bank specific and macroeconomic determinant variables against the DOM_IB variable. As a result, six new bank specific interaction variables, namely LNTA*DOM_IB, LNLLRGL*DOM_IB, LNETA*DOM_IB, LNBDTD*DOM_IB, LNLOANSTA*DOM_IB and LNNIETA*DOM_IB, are introduced in the regression Models 4 to 9, respectively. Besides, two new macroeconomic interaction variables, namely LNGDP*DOM_IB and LNINFL*DOM_IB, are included in the regression Models 10 and 11, respectively.

The empirical findings in column 7 of Table 5 clearly indicate that bank market power (LNBDTD*DOM_IB) has positive impact on the revenue efficiency of the domestic Islamic banks. The results seem to suggest that an increase in bank market power tend to increase the revenue efficiency of the domestic Islamic banks. The finding is consistent with Pasiouras et al. (2008). To recap, Pasiouras et al., (2008) state that bank’s market share has a positive effect on the bank efficiency. A plausible reason could be due to the fact that during the period under study, higher bank market power contributes to high bank concentration level and consequently, changed both loan rates and market shares in an imperfectly competitive loan market. This contributed to the tendency for the Islamic banks to charge high loan markups (Graeve et al., 2007). In column 8 of Table 5 we report the LNLOANSTA*DOM_IB result. As observed, the empirical findings seem to suggest a positive coefficient of the LNLOANSTA*DOM_IB. The result seems to suggest a positive relationship between the level of liquidity and the revenue efficiency of the domestic Islamic banks. The loanperformance relationship depends significantly on the expected change of the economy. The revenue efficiency of the domestic Islamic banks tends to be negatively affected by borrowers which are likely to default on their loans during a strong economy environment.

On the other hand, the empirical findings in column 9 of Table 5 clearly indicate that management quality (LNNIETA*DOM_IB) has positive impact on the revenue efficiency of the domestic Islamic banks. The results imply that an increase (decrease) in these expenses enhance (reduce) the profits of the domestic Islamic banks. There are a few plausible explanations. Firstly, more highly qualified and professional management may require higher remuneration packages and thus a highly significant positive relationship with profitability measure is natural. Secondly, although overstaffing may lead to the deterioration of bank profitability levels in the middle-income countries, it will produce different results for banks operating in the middle- and high-income countries.

Robusteness Checks: Pooled, Panel, Fixed Effect and Random Effect

To further check for the robustness of the results, this study identifies whether the multivariate regression is suitable either with the pooled (OLS) model or the panel data (GLS) model. Based on the Breusch and Pagan Lagrangian multiplier test in Table 6, the result show that the panel regression model under the GLS method is most suitable to be used in this study to obtain the robust results since the p-value of the test is significant.

| Table 6 Breusch and Pagan Lagrangian Multipliertest | |

| Chi-Sq. Statistic (X²) | 20.210 |

| Prob. X2 | 0.0000 |

Therefore, we repeat the Equation (6) and use the Hausman test in order to decide which estimation technique is more appropriate between the FEM and the REM (Table 7). The test suggests that Models 1, 3, 6, and 7 are more appropriate with the REM because the chi square (X²) is not significant at 5% levels and the other models are more suitable with the FEM as it is significant at 1% for the chi square.

| Table 7 Hausman Test | |||||||||||

| Model | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| Chi-Sq. | 8.65 | 25.75 | 15.20 | 18.36 | 21.10 | 16.38 | 16.15 | 22.44 | 19.05 | 24.01 | 18.23 |

| Prob. | 0.19 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Est. tech. | REM | FEM | REM | FEM | FEM | REM | REM | FEM | FEM | FEM | FEM |

Table 8 shows the panel regression models under the GLS method. Although management quality (LNNIETA*DOM_IB) has statistically significant influence on the revenue efficiency of the domestic Islamic banks in the OLS regression model (Table 5), the coefficient of the LNNIETA*DOM_IB loses its explanatory power when we control for bank specific effects in the GLS regression model (col- umn 9 of Table 8). Meanwhile, the impact of capitalization (LNETA*DOM_IB) seems to be positive (statistically significant at the 1% level) indicating that the capitalization tend to lead to higher profitability levels.

| Table 8 Panel Regression Analysis Models Under Generalized Least Square | |||||||||||

| Variable | Models | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| Constant | -4.89 | -1.64 | -0.01 | -0.35 | -0.55 | -0.14 | 6.24 | 0.60 | 7.02 | -0.03 | -1.26 |

| (1.02) | (4.70) | (4.99) | (4.98) | (5.00) | (4.97) | (4.24) | (4.18) | (4.35) | (4.97) | (4.86) | |

| Determinant Variables | |||||||||||

| LNTA | 0.90 | 1.11 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 1.15 | 1.2 | 1.39 | 1.04 | 1.49 | 1.22 | 1.12 |

| (0.18) | (0.37) | (0.39) | (0.39) | (0.38) | (0.39) | (0.39) | (0.33) | (0.39) | (0.39) | (0.38) | |

| LNLLRGL | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.20** | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| (0.10) | (0.10) | (0.11) | (0.11) | (0.14) | (0.11) | (0.093) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.11) | (0.11) | |

| LNETA | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| (0.13) | (0.151) | (0.156) | (0.156) | (0.158) | (0.152) | (0.126) | (0.140) | (0.125) | (0.156) | (0.154) | |

| LNBDTD | –1.11 | –1.33 | –1.399 | –1.389 | –1.351 | –1.402 | –1.585 | –1.138 | –1.607 | –1.400 | –1.341 |

| (0.19) | (0.394) | (0.400) | (0.401) | (0.397) | (0.401) | (0.392) | (0.350) | (0.393) | (0.400) | (0.398) | |

| LNLOANSTA | 0.299 | 0.346 | 0.357 | 0.349 | 0.344 | 0.371* | 0.56** | 0.165 | 0.519* | 0.357* | 0.354* |

| (0.09) | (0.123) | (0.123) | (0.123) | (0.124) | (0.126) | (0.119) | (0.117) | (0.118) | (0.123) | (0.126) | |

| LNNIETA | –0.2** | –0.25 | –0.25 | –0.25* | –0.24* | –0.264* | –0.16* | –0.24* | –0.18* | –0.25* | –0.21* |

| (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.07) | (0.08) | (0.07) | (0.09) | (0.09) | |

| Macroeconomic Variables | |||||||||||

| LNGDP | 0.261 | 0.167 | 0.263 | 0.176 | 0.082 | 0.128 | 0.224 | 0.281 | 0.287 | 0.253 | |

| (0.066) | (0.059) | (0.067) | (0.081) | (0.052) | (0.058) | (0.064) | (0.065) | (0.091) | (0.079) | ||

| LNINFL | -4.697 | -3.283 | -4.705 | -3.161 | -2.047 | -2.74** | -3.915 | -5.02 | -4.755 | -4.426 | |

| (0.991) | (0.886) | (1.000) | (1.313) | (0.770 | (0.855) | (0.983) | (0.978) | (1.010) | (1.768) | ||

| DOM_IB | -0.227 | ||||||||||

| (0.094) | |||||||||||

| Interaction Variables | |||||||||||

| LNTA*DOM_IB | 0.147 | ||||||||||

| (0.313) | |||||||||||

| LNLLRGL*DOM_IB | 0.555 | ||||||||||

| (0.320) | |||||||||||

| LNETA*DOM_IB | 0.899 | ||||||||||

| (0.172) | |||||||||||

| LNBDTD*DOM_IB | -0.367 | ||||||||||

| (0.128) | |||||||||||

| LNLOANSTA*DOM_IB | -0.56 | ||||||||||

| (0.220) | |||||||||||

| LNNIETA*DOM_IB | 0.295 | ||||||||||

| (0.158) | |||||||||||

| LNGDP*DOM_IB | -0.033 | ||||||||||

| (0.079) | |||||||||||

| LNINFL*DOM_IB | -0.212 | ||||||||||

| (1.138) | |||||||||||

| Model | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| R² | 0.489 | 0.494 | 0.502 | 0.499 | 0.497 | 0.501 | 0.645 | 0.613 | 0.644 | 0.502 | 0.495 |

| Adj. R² | 0.438 | 0.425 | 0.425 | 0.422 | 0.419 | 0.424 | 0.590 | 0.553 | 0.589 | 0.425 | 0.416 |

| Durbin Watson | 0.590 | 0.534 | 0.532 | 0.529 | 0.525 | 0.528 | 0.747 | 0.599 | 0.747 | 0.532 | 0.525 |

| F-statistic | 9.719 | 7.189 | 6.492 | 6.426 | 6.379 | 6.473 | 11.726 | 10.195 | 11.676 | 6.499 | 6.309 |

On the other hand, it can be observed from columns 7 of Table 8 that the impact of bank market power (LNBDTD*DOM_IB) turns out to be negative when we control for bank specific effect in the regression model. The results seem to sug- gest that increase in bank market power tend to decrease the revenue efficiency of the domestic Islamic banks. A higher bank market power does not warrant higher profitability levels for Islamic banks because the theoretical predictions and empirical evidence from previous studies have reported that greater bank market power tend to result in a higher bank risk. Therefore, it could be argued that greater bank market power may lead to higher risk levels which consequently could result in lower revenues and profitability levels among the domestic Is- lamic banks. Similarly, the empirical findings presented in column 8 of Table 8 clearly indicate that the impact of liquidity on the domestic Islamic banks (LNLOANSTA*DOM_IB) is negative suggesting that higher liquidity tends to reduce the revenue efficiency of the domestic Islamic banks.

Conclusion

The study was carried out to examine revenue efficiency of the Indonesian Islamic banking sector over the period of 2009 to 2018. To date, the majority of research- ers have focused more on cost and profit efficiency in banking sectors and only a few have looked on revenue efficiency. Furthermore, most of these studies are carried out on the conventional banking sectors, while empirical evidence on the Islamic banking sectors is relatively scarce. The non-parametric Data Envelop- ment Analysis (DEA) method is applied to distinguish between three different types of efficiency measures, namely cost, revenue, and profit. Additionally, we perform a series of parametric (t-test) and non-parametric (Mann-Whitney [Wil- coxon] and Kruskall-Wallis) tests to examine whether the domestic and foreign Islamic banks are drawn from the same population.

We find that there is a statistically significant difference between the domestic and foreign Islamic banks’ revenue efficiency. The result of this study shows that the revenue efficiency of the domestic Islamic banks is relatively lower compared to their foreign Islamic bank peers due to the difference between the cost and profit efficiency levels. If anything could be inferred it is that the empirical findings clearly indicate that better revenue efficiency could improve the level of profit efficiency and, consequently, contribute to higher profitability of the Indonesian Islamic banks. The empirical findings from this study failed to reject the null hypothesis that the domestic and foreign Islamic banks come from the same population and have identical technologies since the revenue efficiency of the domestic Islamic banks is statistically significantly lower compared to the foreign Islamic banks.

We also extend the study to examine the potential determinants of revenue efficiency, particularly for the Indonesian domestic Islamic banks. Six bank specific (internal) determinant variables are included in the regression models namely size, asset quality, capitalization, market share, liquidity, and management qual- ity. In addition, gross domestic products and inflation rate are included in the regression models as external factors control variables. Furthermore, in order to obtain robust results, all potential determinants are interacted with Indonesian domestic Islamic banks dummy variables. To do so, we employ a pooled (OLS) and panel regression (GLS) analysis framework. Furthermore, based on the Breusch and Pagan Lagrangian multiplier test this study will finally depend on the results that produced in the panel regression analysis under the GLS method. In addition, the FEM and REM are tested by the Hausman Test. During the pe- riod under study, we find that capitalization, bank market power and liquidity have significant influence on the revenue efficiency of Indonesian domestic Islamic banks. We find that all three potential determinants are to exert positive and negative influence on the Indonesian domestic Islamic banks’ revenue efficiency. We do not find any statistical significant impact of macroeconomic conditions on the domestic Islamic banks revenue efficiency levels.

The empirical findings from this study clearly call for regulators and decision makers to review the revenue efficiency of banks operating in the Indonesian Islamic banking sector. This consideration is vital because revenue efficiency is the most important concept which could lead to higher or lower profitability of the Indonesian Islamic banking sector. To improve the performance of banks, regulators may need to employ and exercise the same information technologies, skills, and risk management techniques which are applied by the most efficient banks.

The results could also provide better information and guidance to bank manag- ers, as they need to have clear understanding of the impact of revenue efficiency on the performance of their banks. Thus, banks operating in the Indonesian Islamic banking sector have to consider all the potential technologies which could improve their revenue efficiency levels since the main motive of banks is to maxi- mize shareholders’ value or wealth through profit maximization.

The empirical findings from this study may also have implications for investors whose main desire is to reap higher profit from their investments. By doing so, they could concentrate on the potential profitability of banks before investing. Therefore, the findings of this study may help investors plan and strategize on the performance of their investment portfolios. It would be reasonable to suggest that wise decisions that investors make today would significantly influence the level of expected returns in the future.

Nevertheless, the study has also provided insights to policymakers with regard to attaining optimal utilization of capacities, improvement in managerial exper- tise, efficient allocation of scarce resources, and the most productive scale of op- eration of commercial banks operating in the Indonesian Islamic banking sector. This may also facilitate directions for sustainable competitiveness of the Indonesian Islamic banking sector operations in the future.

References

Bader, M. K. I., Mohamad, S., Ariff, M., & Shah, T. H. (2008). Cost, revenue, and profit efficiency of Islamic versus conventional banks: international evidence using data envelopment analysis. Islamic economic studies, 15(2).

Banker, R. D., Charnes, A., & Cooper, W. W. (1984). Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Management science, 30(9), 1078-1092.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Berger, A. N., & Humphrey, D. B. (1997). Efficiency of financial institutions: International survey and directions for future research. European journal of operational research, 98(2), 175-212.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Berger, A. N., & Mester, L. J. (2003). Explaining the dramatic changes in performance of US banks: technological change, deregulation, and dynamic changes in competition. Journal of financial intermediation, 12(1), 57-95.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Berger, A. N., Hunter, W. C., & Timme, S. G. (1993). The efficiency of financial institutions: A review and preview of research past, present and future. Journal of Banking & Finance, 17(2-3), 221-249.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W., & Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European journal of operational research, 2(6), 429-444.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chong, B. S., Liu, M. H., & Tan, K. H. (2006). The wealth effect of forced bank mergers and cronyism. Journal of Banking & Finance, 30(11), 3215-3233.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cooper, W.W., Seiford, L.M. & Tone, K. (2002). Data Envelopment Analysis, a Comprehensive Text with Models, Applications, References and DEA-Solver Software. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Dushku, E. (2016). Some empirical evidence of loan loss provisions for Albanian banks. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 5(2), 157-173.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zeti, A. (2012, October). Internationalisation of Islamic finance–Bridging Economies. In Welcoming address, Governor of the Central Bank of Malaysia at the Global Islamic Finance Forum.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gujarati, D. N. (2002). Basic Econometrics 4th ed.

Igbinosa, S., Sunday, O., & Akanji, B. (2017). Empirical assessment on financial regulations and banking sector performance.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Isik, I., & Hassan, M. K. (2002). Cost and profit efficiency of the Turkish banking industry: An empirical investigation. Financial Review, 37(2), 257-279.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Ivanović, M. (2016). Determinants of credit growth: The case of Montenegro. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 5(2), 101-118.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kamarudin, F., Amin NORDIN, B. A., & Nasir, A. M. (2013). Price efficiency and returns to scale of banking sector in gulf cooperative council countries: Empirical evidence from islamic and conventional banks. Economic Computation & Economic Cybernetics Studies & Research, 47(3).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kamarudin, F., Nordin, B. A. A., Muhammad, J., & Hamid, M. A. A. (2014). Cost, revenue and profit efficiency of Islamic and conventional banking sector: Empirical evidence from Gulf Cooperative Council countries. Global Business Review, 15(1), 1-24.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kamarudin, F., Nassir, A. M., Yahya, M. H., Said, R. M., & Nordin, B. A. A. (2014). Islamic banking sectors in Gulf Cooperative Council countries: Analysis on revenue, cost and profit efficiency concepts. Journal of Economic Cooperation & Development, 35(2), 1.

Kamarudin, F., Sufian, F., & Md. Nassir, A. (2016). Does country governance foster revenue efficiency of Islamic and conventional banks in GCC countries?. EuroMed Journal of Business, 11(2), 181-211.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kamarudin, F., Sufian, F., Nassir, A. M., & Anwar, N. A. M. (2015). Technical efficiency and returns to scale on banking sector: empirical evidence from GCC countries. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 23(9), 219-236.

Kamarudin, F., Hue, C. Z., Sufian, F., & Mohamad Anwar, N. A. (2017). Does productivity of Islamic banks endure progress or regress? Empirical evidence using Data Envelopment Analysis based Malmquist Productivity Index. Humanomics, 33(1), 84-118.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lakić, S., Šehović, D., & Drašković, M. (2016). Relevance of Low Inflation in the Southeastern European Countries. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 5(2), 41-63.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pasiouras, F., Liadaki, A., & Zopounidis, C. (2008). Bank efficiency and share performance: Evidence from Greece. Applied Financial Economics, 18(14), 1121-1130.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rogers, K. E. (1998). Nontraditional activities and the efficiency of US commercial banks. Journal of Banking & Finance, 22(4), 467-482.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Singh, O., & Bansal, S. (2017). An analysis of revenue maximising efficiency of public sector banks in the post-reforms period. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 6(1), 111-125.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sufian, F., Kamarudin, F., & Noor, N. H. H. M. (2013). Assessing the Revenue Efficiency of Domestic and Foreign Islamic Banks: Empirical Evidence from Malaysia. Jurnal Pengurusan, 37.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sufian, F., & Kamarudin, F. (2014). Efficiency and returns to scale in the Bangladesh banking sector: empirical evidence from the slack-based DEA method. Engineering Economics, 25(5), 549-557.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sufian, F., Kamarudin, F., & Noor, N. H. H. M. (2014). Revenue efficiency and returns to scale in Islamic banks: Empirical evidence from Malaysia. Journal of Economic Cooperation & Development, 35(1), 47.

Zhu, J. (2009). Quantitative models for performance evaluation and benchmarking: data envelopment analysis with spreadsheets (Vol. 2). New York: Springer.

Received: 20-Sep-2023 Manuscript No. AAFSJ-23-14026 ; Editor assigned: 21-Sep-2023, PreQC No. AAFSJ-23-14026 (PQ); Reviewed: 04-Oct-2023, QC No. AAFSJ-23- 14026; Revised: 10-Oct-2023, Manuscript No. AAFSJ-23- 14026 (R); Published: 18-Oct- 2023