Research Article: 2021 Vol: 20 Issue: 3

Audit Partner Characteristics: A Literature Review and Future Directions

Mohammed Degan, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Rohami Shafie, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Azharudin Ali, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Abstract

This paper discusses the foregoing literature on the various characteristics of audit partners that may lead to an enhanced quality of audit. Prior studies suggest that academic research requires more focus on the level of individual auditors. Therefore, this paper focuses on audit partner characteristics as audit partners oversee the work of external auditors, and he/she is responsible for the consequences of the audit teams. The audit partner is a significant factor that can increase the quality of audit. Therefore, it is argued that their characteristics perform a primary role in providing high quality audit. However, previous studies show mixed and inconclusive results. Understanding this issue is very important to inform regulators and practitioners about the audit partner characteristics that can be used in improving the quality of audit. Finally, the paper recommends the firms to consider these characteristics as part of the important characteristics for improving their audit quality.

Keywords

Audit Partner, Audit Partner Characteristics, Audit Quality.

Introduction

Over the past several years, a great number of corporate accounting scandals led to the breakdown of many corporations around the world, such as the case of Enron in the United States (US), Parmalat in Italy, SK Networks in South Korea and the Satyam fiasco in India. Due to this accounting scandal, the regulators blamed the auditors for not discharging their responsibility effectively (Chen et al., 2008; Chi & Huang, 2005). There are two levels of auditors, first, the audit firm level and second, the individual partner level. In the last few years, several academic studies suggested that the level of the audit partner is the most significant level. Also, Chin & Chi (2009) argued that the competence of the auditor should be assessed within the level of audit partnership. They further argued that, the audit partners design and perform the process of the audit and ultimately decide the kind of report on the audit that is to be disclosed to the client. Similarly, Gul et al. (2013) proposed that the researchers require more focus on the level of individual partners as audit partners oversee the work of external auditors, and he/she is responsible for the outcome of the audit teams.

In recent years, the prominence of audit partners in determining audit quality has received increasingly more attention. The reason behind this is that audit partners incur legal responsibility when the auditing fails to provide the overall verdict of the audit engagement. In other words, the audit partner has important roles to play for the success or failure of the audit. However, in the last few years, the participation of audit partners in the accounting and audit scandals had been extensively documented. In reality, the quality of the audit is contingent primarily on the result of the decisions of the audit partners (Lee et al., 2017). In this context, the external auditor is led by the engagement audit partner. Therefore, the audit partner’s expertise is a very important issue in determining audit quality. Generally, the engagement audit partner is in charge and responsible for the results of the audit.

Literature Review

Studies on Audit Partner Characteristics

A partner in an audit engagement is defined as “the partner or other person in the firm who is responsible for the audit engagement, its performance and for the auditor’s report that is issued on behalf of the firm”, where the audit partner should be totally responsible for the quality of audit output of each audit engagement to which that partner is assigned (International Standard on Auditing, 2007). To mitigate the divergent of interest that takes place between the principles (owners of the firm) and the agents (management), the latter can employ the services of external monitoring mechanisms by way of appointment of external auditors, who are responsible for verifying the financial statements and reports prepared by the management and, thus, express an opinion on their truth and fairness. As a result, external auditors lend or assure credibility to the financial reporting process by reducing the information asymmetry and the management’s opportunistic behaviour, which will finally increase the quality of the financial reports.

Although the agency theory states how external auditors are a vital mechanism which positively has an effect on the financial reporting process, the product differentiation theory presents that auditors prefer to draw a distinction by way of industry specialisation in order to meet with clients’ demands for an improved quality of audit (Moroney & Carey, 2011; Gul et al., 2009). Moreover, the learning theory proposed that the audit partners need time to evolve specific skills and knowledge about the client to carry out high quality audits (Glaser & Bassok, 1989; Lapre et al., 2000). For instance, an auditor who is performing an audit assignment for the same audit client over a period of time is familiar with the necessary accounting constraints that may require considerable attention (Liu et al., 2017). Thus, the long-term tenure of a partner is related with better audit quality.

In the past few years, there have been an increasing number of researches that examined the various characteristics that might persuade audit engagement partners to offer different categories of audit quality. Several studies show that audit partner characteristics could influence the quality of audit and financial reporting. For instance, in a study by Chi & Huang (2005), they examined audit partner tenure and discretionary accruals. Sundgren & Svanstreom (2014) studied audit partner age and audit quality. Studies by Ittonen et al. (2013) and Hardies et al. (2014) examined audit partner gender and audit quality. Nekhili et al. (2021) examined audit partner gender and earnings management. Other related studies examined audit partners’ workload and audit quality; for example, Suzuki & Takada (2016); Goodwin & Wu (2016); Gul et al. (2017); Lai et al. (2018); Chen et al. (2020) and Raweh et al. (2021).

However, several characteristics related to audit partners have been reported in prior researches, including tenure, industry expertise and experience which impact audit partner behaviour (Carey & Simnett, 2006; Chi & Huang, 2005; Goodwin & Wu, 2014; Lai et al., 2018). In recent times, a large number of studies on the characteristics of audit partners have been undertaken, within the context of ethnicity of the audit partner and the alignment of auditor-client (Berglund & Eshleman, 2019), audit partner identification and audit quality (Lee & Levine, 2020), audit partner workload and audit reporting lag (Wan-Nordin & Bamahros, 2018). Gul et al. (2017) investigated the workload of the audit partner and the quality of audit, the result provides evidence that the audit partner workload may reduce the quality of audit. Taken into account, prior studies indicate how characteristics of the audit partner impact audit quality and offer justification for carrying out research in related areas.

Audit Partner Characteristics and Audit Quality

The engagement partner is the one who takes responsibility of the result of the audit and bears the burden in the case of failure of the audit. It is argued that industry specialist audit partners, through their knowledge and experience from attending to clients in the same industry, can provide high quality audit service (Lee et al., 2017).

Regulators across the globe have identified the significance of expert auditors at the audit partner level (Knchel et al., 2015). Firms audited by expert audit partners possess better quality of audit (Aobdia et al., 2015; Chin & Chi, 2009; Lee et al., 2017). The rationale behind that is due to; the industry expert auditors have more industry distinctive expertise and skills than non-expert auditors (Dunn & Mayhew, 2004). Furthermore, industry expert auditors can provide a better audit quality service to clients. Therefore, the industry expert auditors offer a significant role in supervising the process of sound financial reporting. Audit that is of high-quality should also result in a higher earnings quality by decreasing the practices of earnings management using discretionary accruals (Garcia-Blandon & Argiles-Bosch, 2018). Chin & Chi (2009) found that audit partner industry specialisation had a negative association with accounting restatements. Similarly, a study by Chi & Chin (2011) shows that audit partner industry specialisation had a negative association with discretionary accruals. Chi et al. (2017) found that the industry specialisation has a significant effect on discretionary accruals, while the industry specialisation is insignificantly related to interest rate spreads.

Other than the industry expertise of audit partners, several empirical researchers studied shows how the length of serving for the tenure of an audit partner has a direct effect on the quality of audit. Moreover, there are two sound arguments regarding the tenure of an audit partner. The first argument suggested that a longer tenure of an auditor could result in a better quality of audit; this is because the audit partner could build up more industry-specific and client-specific knowledge due to a longer tenure stay as an auditor (Bedard & Johnstone, 2010; Sharma et al., 2017). With an increase in partner tenure, the audit partner gets more knowledge about the client’s operating environment, procedures and risk control which will lead to a positive outcome in the audit (Manry et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2008; Goodwin & Wu, 2014; Sharma et al., 2017; Raweh et al., 2021), hence, leading to a rise in financial reporting quality. Consistent with these studies, Chi et al. (2017) show that the long-serving audit partner tenure is related to smaller discretionary accruals, leading to higher quality audit.

The second argument suggested that a rotation of the audit partners may be suitable as it introduces a new viewpoint to the audit. Furthermore, when the audit partners become more known by the management, they are probably more compromised in their objectivity and tend to comply with the client’s position (Litt et al., 2014; Ball et al., 2015; Laurion et al., 2017).

The workload of an audit partner is another characteristic that may affect the quality of audit. Partner workload is the total number of quoted companies in the portfolio of a partner’s client. There are two points of views regarding audit partner workload. The first point of view is that audit partners with a heavy workload who are in charge of many audits may face detrimental effects because they are not be able to allocate sufficient time to discharge their duties in directing audit efforts. A substantial workload could side track an audit partner from offering sufficient consideration to an audit assignment and could prompt the partner in the audit to take the easiest way rather than employing all the necessary audit evidence (PCAOB, 2015). Also, the Malaysian Audit Oversight Board (AOB) focused on the workload of an audit partner and has further emphasised that: “it is imperative for audit partners to have sufficient time to properly lead and supervise audits” (Audit Oversight Board, 2017). Consequently, audit partners facing a heavy workload may be managed inadequately and may make speedy decisions due to time pressure, leading to low quality audits.

On the other hand, a considerable amount of literature has been published on the clients that point out that the audit partner expertise in managing multiple clients is able to draw the attention of more clients into his domain. Regarding the benefits attached to auditing several clients, a recent investigation by Goodwin & Wu (2016) claimed that a partner with a large number of clients is considered to be more objective and credible. The result indicates that the workload of an audit partner is positive and significantly related to the quality of audit. In other related studies by Suzuki & Takada (2016) and Lai et al. (2018), suggested that audit partner workload is viewed as a valuable sign for the quality of audit through the accumulated knowledge and experience from serving multiple clients. Sundgren and Svanstreom (2014) found that the workload of the audit partner is negatively related to the decision of the audit partner to issue a GC opinion. The study suggests that the audit partners which facing a heavy workload lead to provide low-quality audit. Lai et al. (2018) found that audit partners with more listed clients are related to larger absolute discretionary accruals. Chen et al. (2020) found that audit partner workload compression has a negative relationship with accruals quality. However, Raweh et al. (2021) did not find any relationship between audit partner busyness and audit efficiency. The result of previous studies on audit partner workload and audit quality shows mixed findings, taking into account the inconsistent arguments. As a result, predicting the relationship between an audit partner's workload and the quality of audit is exceedingly difficult.

Audit Partners’ Personal Characteristics

Very few studies have attempted to explain the audit partners’ personal characteristics and their relationship with the outcome of audits. These audit partner characteristics include age, gender, education, and ethnicity. On one hand, studies found that the individuals became more conservative and virtuous as they grew older (Sundaram & Yermack, 2007). However, a study by Mudrack (1989) proposed that age is regarded as a sound measure of professional ethical behaviour. The finding from this study implies that elderly individuals are more ethical, due to the fact that they possess a longer, relentless knowledge of established customs and culture. On the other hand, previous studies indicate that professional workers’ dealings become gradually weaker as they grow older, which leads older personnel to make use of little effort (Holmström, 1999).

According to Sundgren & Svanstreom (2014), they claimed that aged audit partners are not able to offer high audit quality. The study found that audit partner age has a negative relationship with the propensity of the partner to provide a going concern opinion; this is because an older audit partner needed more time to understand the going concern assumption. In the same vein, Goodwin & Wu (2016) provide evidence that most of the older partners of an audit are less likely to provide a going concern opinion for the first time and are linked with larger discretionary accruals. The results from this study are in line with the postulation that aged audit partners offer lower audit quality.

However, the argument from the behavioral research point of view is that women are very likely to adhere to the rules when compared to men. Due to the deference between these genders, the association between the gender of the audit partner and the quality of audit has been explored by several researchers. Nekhili et al. (2021) claim that gender-diverse audit partners have a competitive advantage over all-male audit partners due to improved interaction between male and female audit partners. Furthermore, Ittonen et al. (2013) hold the view that female audit partners in the firms are related to fewer abnormal accruals. The researchers argue that female audit partners could have a constraining impact on the practices of earnings management because females are more conservative.

Another study by Hardies et al. (2014), show that a female audit partner has a higher possibility of issuing going concern opinions to a financially distressed company. Further evidence is given by Li et al. (2017) where they hold the view that female audit partners are more related to smaller accruals. Hardies et al. (2015) found that the female audit partners are related to higher audit fees. The study indicates that the higher audit fees paid to the female audit partner are due to the higher preferences, abilities, knowledge, skills, or achieve greater satisfaction of the client compared to male audit partners. However, researchers have consistently shown that personal connections among audit partners and clients weaken the quality of audit. A study reported by Guan et al. (2016) studied the relationship between the client-partner school ties on the quality of audit. The findings from this study indicate that clients feel more comfortable and get to know one another while engaging in an audit assignment with audit partners that possess similar levels of education.

Thus, the levels of educational ties can expedite the dissemination of information between the audit partner and the client’s management which could enhance the quality of the audit. From another point of view, the mutual trust between audit partners and mangers of a client could harm the independence. It has been found at the level of educational relationship within the audit and has been empirically confirmed by Guan et al. (2016) that partners as well as client management compromise the quality of audit. In a similar finding by He et al. (2017), they supply evidence that the social relationship between the partners in an audit and the audit committee can impair the quality of the audit. Therefore, it is essential to point out that the above findings may not be spread out in advanced countries where personal relationships are of little importance.

Furthermore, several researchers have also investigated the educational background of an audit partner in relation to the quality of audit. In a study by Gul et al. (2013), they show that audit partner that hold a university degree are more aggressive results for an audit work. In another related study by Chu et al. (2016), they found that audit engagement partners who are accounting graduates were evidenced to be more effective in deterring abnormal accruals; moreover, the accounting graduates are charging higher audit fees as against audit partners that possess degrees in social sciences. Equally, Li et al. (2017) found that an audit partner that possesses a graduate degree in accounting or finance is more probable to restrain abnormal accruals. Regarding the ethnicity of an audit partner, Berglund & Eshleman (2019) found that the clients are more probably to choose an audit partner who is of the same ethnicity as the manager of the client. The result shows that co-ethnicity is related to a low probability to issuing a going concern opinion to clients that are facing financial trouble and rise the likelihood of under-reporting of the administrative expenses and fundraising. The review of the previous studies shows a lack of studies that examined several research questions related to audit partner characteristics, therefore more studies are required in order to support the robustness of the findings.

Methodology

The audit partner characteristics is an extremely important topic considering the fact that partners in an audit assignment incur legal responsibility in the case of failure of an audit and therefore, the characteristics of partners in an audit are very important in determining the outcome of an audit. Audit partners design and oversee the audit assignment and eventually ascertain the category of the audit report to be disclosed to the client. In view of the significance of this topic, this paper examines the extent to which audit partner characteristics affect audit quality.

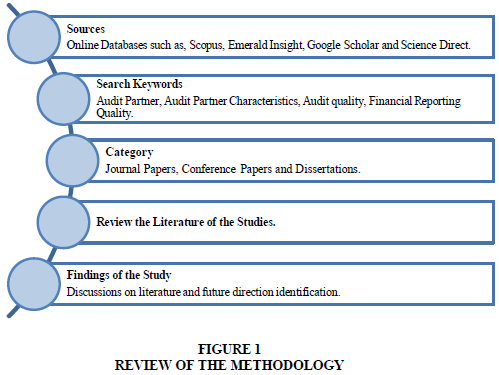

In order to constrain the scope of this study, this present study gives special attention to the archival studies published from the following journals: A Journal of Practice & Theory, Review of Accounting Studies, Managerial Auditing Journal, Journal of Accounting Research, Contemporary Accounting Research, and The Accounting Review. On the other hand, the online research databases such as Scopus database, Web of Science, Emerald Insight, Science Direct, and Google Scholar were used to search for related literature on this paper. The keywords employed for the review of literature were: "audit partner characteristics" "audit partner" and “audit quality”. The papers included in this review fulfil the following criteria: All the studies that examine the relationship between audit partner characteristics and any measurement for audit quality, exclude non-English studies. And to ensure all related studies through 2021 are included in this study, the publication date was not limited. As a result of these methods, 31 papers published in 17 journals dealing with the effect of audit partner characteristics on audit quality from 2005 to 2021 are included in this study. For this paper, Figure 1 presents the methodology in the form of a graph.

Discussion and Conclusion

The main purpose of this present study is to supply a conceptual review of the previous empirical studies that investigated the relationship between audit partner characteristics and audit quality. Therefore, this paper is expected to increase the understanding of regulators, researchers and policymakers regarding the roles and characteristics of audit partners. In general, the findings of the conceptual review reveal that the roles and characteristics of audit partners have an influence on the quality of audit and financial reporting quality (FRQ).

The conceptual review of studies on audit partners provides evidence on the characteristics of audit partners, such as the industry specialist of audit partners. It is argued that an audit partner that is an industry expert can gain a better understanding of the client's work as a result of the spill over effects of the industry expert. Industry specialist audit partners are better in detecting a client’s unethical financial reporting practice. Therefore, their skills will ensure that financial statements reveal information completely. However, it is extremely important to point out that such expertise may positively influence the audit quality and FRQ. Likewise, with an increase in partner tenure, the audit partner gets more knowledge about the client’s business operations, which will lead to success in the auditing. For this reason, the asymmetry of information between the owner of the firm and the stakeholders can be reduced. Furthermore, female audit partners avoid risks in making financial decisions, as well, are more probably to comply with the rules compared to men, leading to high quality audits. However, reviewing all of the above-mentioned empirical studies has identified several research gaps in the literature as a result of the conflicting findings from previous studies. Therefore, to address the shortcomings of previous studies, suggestions were made for upcoming research.

However, the relationships between audit quality and audit partner characteristics are still inconclusive. Future research may supply additional evidence on the results of the review and explore further the roles of audit partner characteristics. Despite the fact that some progress has been made in figuring out the relationship between audit partner characteristics and the quality of audit, the area has thrown up many questions in need of further investigation. Furthermore, the review of literature on the relationship between audit partner characteristics and audit quality presents an inconclusive finding. However, some recent empirical studies have established a significant positive relationship while other related studies present a negative relationship between these characteristics and the quality of audit. Therefore, the characteristics of an audit partner and their association with the quality of audit remain unclear. Moreover, further studies are required to investigate whether audit partner characteristics have a different effect on financial fraud and audit quality.

There are very limited studies that try to examine the issue regarding audit partner personal characteristics. However, the present study contributes to the body of knowledge in the area of auditing. The study also contributes to the practice and helps regulators in making an informed decision. Future research need to consider other characteristics that might affect the attribute of audit quality and FRQ, such as the religious belief of audit partners, ethnicity of audit partners, gender and age of audit partners. Therefore, this paper provides an avenue for future research to undertake similar research by extending the ideas given in this research as presented in Table 1.

| Table 1 Recommended Future Directions of Audit Partner Characteristics Research | |

| No. | Research Questions |

| RQ1 | Do audit partner characteristics important to improve the quality of audit? |

| RQ2 | Do audit partner personal characteristics affect partner behaviour? |

| RQ3 | Do audit partner personal characteristics, namely audit partner ethnicity, audit partner age, audit partner gender affect audit quality? |

| RQ4 | Do audit partner characteristics enhance the quality of financial reporting? |

References

Aobdia, D., Lin, C.J., & Petacchi, R. (2015). Capital market consequences of audit partner quality. The Accounting Review, 90(6), 2143-2176.

Ball, F., Tyler, J., & Wells, P. (2015). Is audit quality impacted by auditor relationships ? Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, 11(2), 166-181.

Bedard, J. C., & Johnstone, K.M. (2010). Audit partner tenure and audit planning and pricing. A Journal of Practice & Theory, 29(2), 45-70.

Berglund, N.R., & Eshleman, J.D. (2019). Client and audit partner ethnicity and auditor-client alignment ethnicity. Managerial Auditing Journal, 34(7), 835-862.

Carey, P., & Simnett, R. (2006). Audit partner tenure and audit quality. The Accounting Review, 81(3), 653-676.

Chen, C.Y., Lin, C.J., & Lin, Y.C. (2008). Audit partner tenure, audit firm tenure, and discretionary accruals: Does long auditor tenure impair earnings quality? Contemporary Accounting Research, 25(2), 415-445.

Chen, J., Dong, W., Han, H., & Zhou, N. (2020). Does audit partner workload compression affect audit quality?. European Accounting Review, 29(5), 1021-1053.

Chi, H.Y., & Chin, C.L. (2011). Firm versus partner measures of auditor industry expertise and effects on auditor quality. A Journal of Practice & Theory, 30(2), 201-229.

Chi, W., & Huang, H. (2005). Discretionary accruals, audit-firm tenure and audit-partner tenure: Empirical evidence from Taiwan. Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, 1(1), 65-92.

Chi, W., Myers, L., Omer, T., & Xie, H. (2017). The effects of audit partner pre-client and client-specific experience on audit quality and on perceptions of audit quality. Review of Accounting Studies, 22(1), 361-391.

Chin, C.L., & Chi, H.Y. (2009). Reducing restatements with increased industry expertise. Contemporary Accounting Research, 26(3), 729-765.

Chu, J., Florou, A., & Pope, P.F. (2016). Does accounting education add value in auditing? evidence from the UK. Working paper. University of Cambridge, King’s College London, and The London School of Economics and Political Sciences.

Dunn, K.A., & Mayhew, B.W. (2004). Audit firm industry specialization and client disclosure quality. Review of Accounting Studies, 9(1), 35-58.

Garcia-Blandon, J., & Argiles-Bosch, J.M. (2018). Audit partner industry specialization and audit quality: Evidence from Spain. International Journal of Auditing, 22(1), 98-108.

Glaser, R., & Bassok, M. (1989). Learning theory and the study of instruction. Annual Review of Psychology, 40(1), 641-666.

Goodwin, J., & Wu, D. (2014). Is the effect of industry expertise on audit pricing an office-level or a partner-level phenomenon. Review of Accounting Studies, 19(4), 1532-1578.

Goodwin, J., & Wu, D. (2016). What is the relationship between audit partner busyness and audit quality? Contemporary Accounting Research, 33(1), 341-377.

Guan, Y., Nancy, L., Wu, D., & Yang, Z. (2016). Do school ties between auditors and client executives influence audit outcomes? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 61(2-3), 506-525.

Gul, F.A., Fung, S.Y.K., & Jaggi, B. (2009). Earnings quality: Some evidence on the role of auditor tenure and auditors’ industry expertise. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 47(3), 265-287.

Gul, F.A., Ma, Shuai, M., & Lai, K. (2017). Busy auditors, partner-client tenure, and audit quality: evidence from an emerging market. Journal of International Accounting Research, 16(1), 83-105.

Gul, F.A., Wu, D., & Yang, Z. (2013). Do individual auditors affect audit quality? Evidence from archival data. Accounting Review, 88(6), 1993-2023.

Hardies, K., Breesch, D., & Branson, J. (2014). Do ( Fe ) male auditors impair audit quality ? Evidence from going-concern opinions. European Accounting Review, 25(1), 7-34.

Hardies, K., Breesch, D., & Branson, J. (2015). The female audit fee premium. A Journal of Practice & Theory, 34(4), 171-195.

He, X., Pittman, J.A., Rui, O.M., & Wu, D. (2017). Do social ties between external auditors and audit committee members affect audit quality? American Accounting Association, 92(5), 61-87.

Holmström, B. (1999). Managerial incentive problems: A dynamic perspective. The Review of Economic Studies, 66(1), 169-182.

Ittonen, K., Peni, E., & Vähämaa, S. (2013). Female auditors and accruals quality. Accounting Horizons, 27(2), 205-228.

Knchel, W.R., Vanstraelen, A., & Zerne, Mi. (2015). Does the identity of engagement partners matter ? an analysis of audit partner reporting decisions. Contemporary Accounting Research, 32(4), 1443-1478.

Lai, K.M.Y., Gul, F.A., Foo, Y., & Hutchinson, M. (2018). Busy auditors , ethical behavior , and discretionary accruals quality in Malaysia. Journal of Business Ethics, 150(4), 1187-1198.

Lapre, M.A., Mukherjee, A.S., & Wassenhove, L.N. Van. (2000). Behind the learning curve : Linking learning activities to waste reduction. Management Science, 46(5), 597-611.

Laurion, H., Lawrence, A., & Ryans, J.P. (2017). U.S. Audit Partner Rotations. The Accounting Review, 92(3), 209-237.

Lee, H., Lee, H.L., & Wang, C.C. (2017). Engagement partner specialization and corporate disclosure transparency. International Journal of Accounting, 52(4), 354-369.

Lee, K.K., & Levine, C.B. (2020). Audit partner identification and audit quality. Review of Accounting Studies, 25(2), 778-809.

Li, L., Qi, B., & Tian, G. (2017). The Contagion Effect of Low-Quality Audits at the Level of Individual Auditors. The Accounting Review, 92(1), 137-163.

Litt, B., Sharma, D.S., Simpson, T., & Tanyi, P.N. (2014). Audit partner rotation and financial reporting quality. American Accounting Association, 33(3), 59-86.

Liu, L.L., Xie, X., Chang, Y.S., & Forgione, D.A. (2017). New clients, audit quality, and audit partner industry expertise: Evidence from Taiwan. International Journal of Auditing, 21(3), 288-303.

Manry, D.L., Mock, T.J., & Turner, J.L. (2008). Does increased audit partner tenure reduce audit quality? Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 23(4), 553-572.

Moroney, R., & Carey, P. (2011). Industry- versus task-based experience and auditor performance. A Journal of Practice & Theory, 30(2), 1-18.

Mudrack, P.E. (1989). Group cohesiveness and productivity: A closer look. Human Relations, 42(9), 771-785.

Nekhili, M., Javed, F., & Nagati, H. (2021). Audit Partner Gender, Leadership and Ethics: The Case of Earnings Management. Journal of Business Ethics, 8(2) 1-28.

Peterson, A.T., Sa, V., Sobero, J., Bartley, J., Buddemeier, R.W., & Navarro-sigu, A.G. (2001). Effects of global climate change on geographic distributions of Mexican Cracidae. Ecological Modelling, 144(1), 21-30.

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). 2015. Concept release on audit quality indicators (release no. 2015-005, July 1, 2015). Washington, DC: PCAOB.

Raweh, N.A. M., Kamardin, H., Malik, M., & Hashed, A. (2021). The association between audit partner busyness, audit partner tenure, and audit efficiency. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 11(1), 90-103.

Sharma, D.S., Tanyi, P. N., & Litt, B.A. (2017). Costs of mandatory periodic audit partner rotation: Evidence from audit fees and audit timeliness. American Accounting Association, 36(1), 129-149.

Sundaram, R.K., & Yermack, D.L. (2007). Pay me later : Inside debt and its role a case study : Jack welch of general electric. Journal of Finance, 62(4), 1551-1588.

Sundgren, S., & Svanstreom, T. (2014). Auditor-in-charge characteristics and going-concern reporting. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31(2), 531-550.

Suzuki, K., & Takada, T. (2016), “Do client knowledge and audit team composition mitigate partner workload?”, paper presented at the 2017 American Accounting Association Auditing Section Midyear Meeting.

Wan-Nordin, W., & Bamahros, H.M. (2018). Lead engagement partner workload , partner-client tenure and audit reporting lag Evidence from Malaysia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 33(3), 246-266.