Research Article: 2022 Vol: 28 Issue: 5

Association between Rapid Development of Microfinance and Related Critical Circumstances: A Narrow Review

Bishnu Prasad Bhandari, Tribhuvan University

Citation Information: Bhandari, B.P. (2022). Association between rapid development of microfinance and related critical circumstances: A narrow review. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 28(5), 1-18.

Abstract

Nepal Rastra Bank has played pivotal role in building up the institutional network and mechanism for easy and smooth availability of the micro-finance for the income generating activities of the poor and the deprived people. This has resulted in the emergence of many micro-finance institutions, which have been participating in the micro-financing operation using it as one of the effective financial tools for poverty reduction. However, these micro-finance institutions have not been able to provide services to all the targeted people. There is a wide scope and tremendous opportunity for these institutions to involve in micro financing right through various rural financing program. The challenge is first reaching out to the majority of the poor people with micro finance and secondly making them viable, sustainable, and profitable. Nepal is moving towards microfinance development and faces some problems which are hurdle in development of microfinance. These highlighted problems in literature should be sort out by implementing the positive recommendations.

Keywords

Microfinance, Nepal Rastra Bank, Organizations Development.

Introduction

Typically, banking and associated facilities have been out of reach for many people with lower income, especially customers and self-employed workers. For the most part, the goal of this movement is "a world where as many poor and near-poor families as feasible have total access to an acceptable variety of top-grade payment institutions, encompassing not just lending but also deposits, health coverage, and transfers of money" (Hermes & Hudon, 2018). Over the past twenty years, global banking has been one of the most successful financial ideas, and many organizations and institutions have attributed their economic security to it. During the previous two decades, the global microfinance industry has risen at an exponential rate, engulfing the global banking industry (Pignatel & Tchuigoua, 2020; Rahman, 2001). Since its inception, the banking industry has been dedicated to alleviating poverty in underdeveloped nations like Nepal (Chapagain & Dhungana, 2020; Adams & Von Pischke, 1992).

For the benefit of developing countries, microfinance institutions provide a viable source of lending for big groups of individuals who wish to invest and expand their financial foundations (Dhakal et al., 2020). Microfinance has a straightforward goal: to affect systemic change across the world's financial institutions. Many private microfinance and non-profit organizations were established in the early 2000s with microfinance programs. Successful microfinance programs were launched by NGOs such as Nirdhan Utthan Bank and the Center for Self-help Development (CDF) under the Grameen Model. Chhimek Bikas Bank Ltd. (CBB), Deprosc Bikas Bank Limited (DBB), and Neruda Microfinance Development Limited (NMDB) were also established as Microcredit Banks. The Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) licensed and authorized NGOs that were engaged in community-based financial operations, resulting in the formation of Financial Intermediary NGOs (FINGOs) (Nepal Rastra Bank, NRB, 2022). There are several operational microfinance organizations in Nepal that provide banking assistance to the needy. Many major social and financial shifts have occurred in Nepal in the past few years, and we must keep up with the latest information about the poor and economic circumstances in the nation (Shrestha, 2020). As per prior research, the execution of financial growth faces several challenges. Because of the country's tremendous hardship and difficult geographical position, providing banking operations to the poor in Nepal is exceptionally difficult (Oli, 2018; Arzeni & Akamatsu, 2014; Adusei & Adeleye, 2021).

It is difficult to make money because of a lack of economic prospects and a lack of arable land. Nepalese women are much less well-off than their male counterparts, lack access to education, and are less able to influence their country's economy. Predominantly domestic and agricultural, they have minimal economic options, working largely as semi-skilled or unemployed general wage employees. Increasing women's financial security and self-reliance by making loans and savings more widely available is effective in combating poverty (Khanal & Bhatta, 2022; Akhter & Cheng, 2020; Nkamnebe & Idemobi, 2011). Providing long-term access to financial services has to be done effectively and sustainably. The 4th Nepal Living Standards Survey (NLSS-IV) will be carried out in 2019-20 by the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) (2020), Government of Nepal, with help from the World Bank. This study, NLSS-IV, arrives at a critical time in Nepal's growth.

After the foundation of Nepal Bank Limited as the country's first financial company, the current banking system was implemented in Nepal. Microfinance has a lengthy history in both industrialized and developing nations, notably in Asia. Poverty alleviation has become more dependent on the use of microfinance institutions for the underprivileged. A social care strategy is taking place in this country rather than a corporate strategy. Microfinance is a beneficiary of a 'social banking' strategy rather than a long-term, sustainable form of financial intermediation. Microfinance institutions must make policy and managerial adjustments in response to five important challenges highlighted by the government and funders. For microfinance institutions to be financially viable, they need to be self-sufficient in terms of financial reporting and subsidies, as well as be financially self-sufficient in terms of financial coverage and subsidization, as well as be financially self-sufficient in terms of financial coverage and subsidization.

When it comes down to it, Nepali microfinance firms will have to move away from treating their customers as recipients who need handouts and subsidies and instead concentrate on providing them with valuable services they can pay for. This report, on the other hand, focuses on financial development and associated essential concerns. Microfinance organizations in Nepal describe their financial and operational expenses of financial intermediation better than their counterparts in several other South Asian nations. Microfinance programs in Nepal need to improve their current reporting, such as dividing bank lending from other operations, accurately assessing and capturing loan losses, and replacing disclosed financing costs and accumulated loan payments with the investment at risk and existing lending outstanding, respectively. A companion piece to this document discusses the existing gaps that require further examination through this and future research to help successfully operate microfinance and association with critical issues areas. So, we have conducted this study to overcome the issues which are a hurdle in advancements in microfinance development. Here are the objectives of this paper given below.

1. To review the association between the rapid development of microfinance and related critical circumstances in Nepal.

2. To suggest means of creating favorable conditions to support both expansions to poor groups not currently served (particularly women) and mechanisms to improve the long-term sustainability of microfinance institutions.

3. To provide recommendations to sort out the critical circumstances of microfinance in Nepal.

Literature Review

Microfinance and MFIs

Mohamad Yunis established microfinance in 1976 as a way to help the impoverished in rural regions by giving them modest, unsecured loans. Yunis sees microfinance as a way to alleviate poverty by empowering the individual. Microfinance was the foundation for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 and was widely accepted as a successful policy instrument by regulators, funders, and sponsors throughout the globe during its most prosperous time (Banerjee et al., 2015; Besley & Cord, 2007). For low-income individuals, accessibility to basic financial institutions is very restricted, and this opens the way for greater financial inclusion. Microfinance may help low-income families better deal with financial crises, better manage their cash flow, and make long-term investments (Besley & Cord, 2007). Many millions of low-income individuals might benefit from reliable financial services if microfinance was successful in showing that impoverished families can be trustworthy clients and that availability of a reliable banking system could alleviate their reliance on moneylenders (Cons & Paprocki, 2010).

More specifically, microfinance institutions have proven to reach poor women, particularly providing the hope of breaking gender-based barriers and reducing violence. Rural lending has been a major financial instrument used by the government of Nepal since 1974. Until the 1990s, this lending was carried out by a few dedicated projects run by commercial banks. However, the 1990s saw the rise of rural development banks established solely to provide access to finance to people in villages. Traditionally, it has been argued that increased enterprise formation and access to credit make women more empowered, and hence crime against them becomes fewer. However, recent studies have questioned the assumption that Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) empower women (Banerjee et al., 2015). While some researchers, notably Hashemi et al. (1996), had earlier asserted that minimalist credit programs do empower women, others believed the optimal solution to address the gender parity issue should be to confront the patriarchy system directly rather than design programs around the issue of access to credit (Goetz & Gupta, 1996; Casper, 1994; Geetha et al., 2017; Ghalib, 2015). There is also disagreement among academicians about the causal relationship between overall economic development and gender empowerment.

While some researchers (Doepke et al., 2019) assert that economic development is naturally followed by more empowerment of women, others (Chassang & i Miquel, 2009) do not agree that economic development is a sufficient condition for female empowerment. In Nepal's context, lendings by MFIs were minimalist and not tailored to subvert existing cultural norms that have traditionally managed to place women at the lower echelon of gender hierarchy. Therefore, any improvement in the social position of women due to microfinance lending is channeled through their access to finance for them. Many Nepali women entrepreneurs still face difficulties in accessing credit, and, in a recent survey, a fully 46.1 percent of women cited access to credit as the major hurdle faced by them in growing their business, second only to find customers, which were cited as a constraint by 52.2 percent.

The variation in the target group for different MFIs also affords a good opportunity to test whether overall improvement in lending (thus increasing access to credit for the poor household) has better outcomes in terms of gender parity than gender-specific targeting. Not all empirical evidence would support the view that economic growth reduces violence in society. Argue that variations in policies addressing violence against women are, in general, not associated with economic factors but are spurred by the mobilization of feminist movements. Hence any reduction of social violence against particularly women, if they are caused by relevant legal instruments introduced in a country, would not be linked with the income-expanding intervention such as MFIs.

Microfinance is now widely accepted as a powerful instrument for poverty eradication across the world. Nevertheless, despite encouraging outcomes in many regions, the poorest people have yet to benefit from microfinance services. In Nepal, like in many other emerging economies, large populations remain without access to formal financial services. At the same time, the microfinance sector, in particular, faces a variety of difficulties. The infrastructure and insufficiency of funds in remote and distant places are restricted, which is why they are home to the majority of the poor. In settings like these, microfinance businesses are doomed to fail. The administration must take a more active role in the development of the infrastructure necessary to improve farming and the local economy. In many situations when there is a lack of assistance and cooperation among government entities and micro-finance banks/institutions. In a few select locations where a greater number of institutions serve the same set of clientele, many individuals from rural and distant locations go to towns and cities seeking seasonal work. As a result of their short-term presence in the program regions, MFIs are reluctant to provide services to them. As a result, the vast majority of political parties and their leaders have no idea what microfinance is or why MFIs need to be institutionally sustainable. Sometimes, they have advocated for reduced interest rates and debt forgiveness. Even in the Tarai districts, where financial institutions are prevalent, the ultra-poor, the marginalized castes, and the destitute are still unable to access the programs. Focusing on these susceptible demographics is critical for MFIs.

In many regions of the nation, highly subsidized microcredit programs are still in operation, putting at risk the budgeting skills and fundamental standards of microfinance institutions. NRB mandates that commercial banks, development banks, and finance companies provide a deprived sector loan of 3 percent, 2 percent, and 1.5 percent of their transactions to MFIs, but lending on a micro-hydro, hospital, youth for employment, and small housing is counted in microfinance, which accounts for nearly half of the MFIs' new resources. MF Banks are growing into rural and underserved regions, but resources will be constrained by the expansion. The NRB and the government should take a more active role in ensuring that MFIs have access to 3 percent of all loans.

Methodology

Current Macroeconomic and Financial Situation of Nepal

Inflation

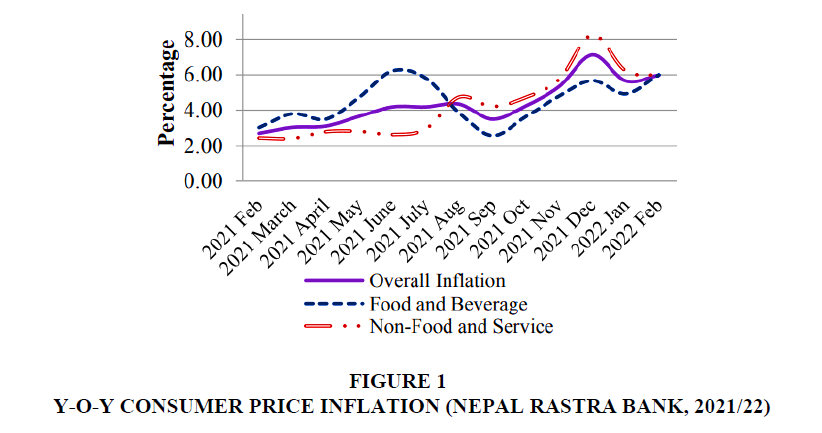

At 5.97 percent year-over-year inflation in the 7th month of the Fiscal year 2021/22, commodity prices were up from 2.70 percent. In the period under consideration, prices in the f&b industry were 6 percent, while inflation in non-food and service-related industries was 5.96 percent. On a year-over-year premise, ghee & oil, vegetables, and legumes & lentils categories saw price increases of 20.68 percent; 14.07 percent; and 9.36 percent, accordingly, under the f&b sector (Figure 1). Non-food and service costs climbed by 15.87 percent, 7.86 percent, and 5.92 percent year-over-year, accordingly, in the transport, schooling, furnishings, and domestic equipment categories. Inflation was 5.47 percent in the Kathmandu Valley, 6.50 percent in Terai, 5.32 percent in Hill, and 5.97 percent in the Mountains. There was 2.12 percent, 2.78 percent, 3.30 percent, and 2.05 percent inflation in each of these areas a year earlier, respectively.

External Sector

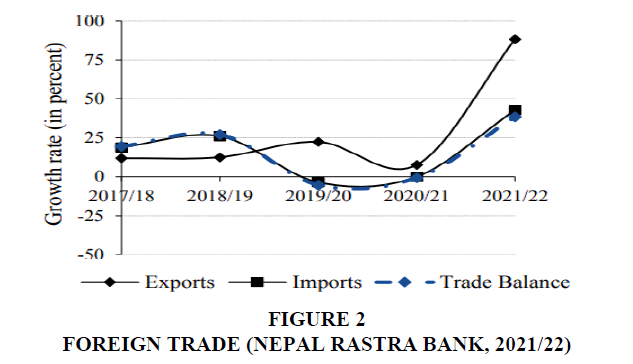

To put it another way, exports of goods jumped 88.5% in the first 7 months of 2021/22, representing an increase of just 7% in the same time last year. Goods exports and other nations grew by 113% and 27.7 percent, respectively, while exports to China declined by 12.4 percent. There was a rise in palm oil exports and a reduction in sales of other products during the evaluation period, such as soybean oil, oil pancakes, polyamide threads, and juices. There was a 42.8% rise in goods imports in the first 7 months of the fiscal year 2021/22 representing an increase of only 0.01% last year. There was a 30.9% rise in import bills, 42.3% from China, and 83.8% from other nations. There was a rise in the importation of oil products and medicine during the period under study, whereas the importation of M.S. billet, fertilizers, concrete, pulsed sugars, and soyabean oil fell. Across all main customs points studied, exports declined from Kanchanpur, Mechi, and Nepalgunj Customs Office, while exports grew from all other locations (Figure 2).

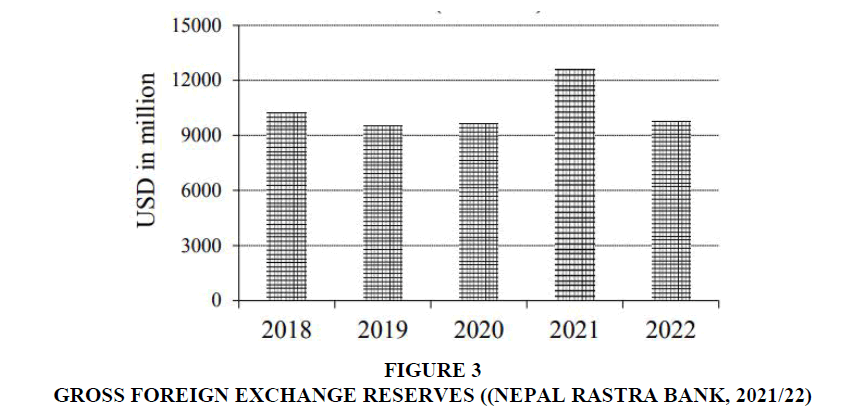

Price increased at all of the main immigration sites during the period under consideration. During the first 7 months of 2021/22, the total trade imbalance grew by 38.4% to Rs.1015.81 billion (Figure 3). At the same time last year, the gap had shrunk by 0.7%. During the evaluation time, the output ratio rose from 8.7% to 11.5%, a sharp rise. During the first 7 months of 2021/22, India imported goods worth Rs.128.17 billion in changeable foreign exchange. At the same time as the previous year, the sum was Rs.104.13 bn. It is estimated that 48.2% of exports were intermediary and final consumer items, while the percentage of capital equipment in export earnings stayed constant at 0.02%. The proportions of intermediary, investment, and final consumer items to export earnings stayed at 32.4 percent, 0.6 percent, and 67.0%, respectively, during the same time last year. In terms of imports, the percentage of intermediate products, capital goods, and final consumption items remained stable at 53.7%, 10.9%, and 35.4%, respectively. At the same time last year, these percentages were 53.3 percent, 11.9 percent, and 34.8 percent, respectively. Year-over-Year, the exchange rates rose by 11.4%, and the import price index rose by 11.6% in the 7th month of 2021/22, predicated on customs purposes (Nepal Rastra Bank, 2021/22). The percentage of Nepali employees (Renew entry) who received permission for overseas workers rose by 265.9% to 152,325 during the review period. When compared to the same time last year, it had fallen by 73.1%. The net transfer of Rs.603.73 billion declined by 4.2% in the evaluation period. During the same period the year before, this kind of transfer had grown by 8.9 percent. From Rs.1399.03 billion in mid-July 2021 to Rs.1173.02 billion in mid-February 2022, the gross foreign currency reserves declined by 16.2%. The total foreign currency reserves, measured in US dollars, fell from $11.7 billion in mid-July 2021 to $9.75 billion in mid-February 2022 (Nepal Rastra Bank, 2021/22).

In mid-February 2022, the NRB's currency reserves dropped 17.7% to Rs.1024.60 bn from Rs.1244.63 bn in mid-July 2021, according to the country's central bank. From Rs.154.39 bn in mid-July 2021, financial institutions' organizations' assets (excluding NRB) fell by 3.9 %by mid-February 2022 to Rs.148.42 bn. By the middle of February 2022, the Indian currency made up 24.2 %of the original capacity.

Fiscal Situation

At Rs.591.02 bn, total national state spending for the first 7 months of 2021/22 was reported by the Financial Comptroller General Office (FCGO), Ministry of Finance. Rs.475.62 bn was the money paid on recurring, structural, and fiscal spending in the review process (Table 1) (Nepal Rastra Bank 2021/22).

| Table 1 Fiscal Situation In Nepal |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particulars | Amount in Rupee (Billions) | Percentage Change | |||

| 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | |

| Total Expenditure | 487.09 | 499.68 | 591.02 | 2.6 | 18.3 |

| Total Revenue | 492.28 | 498.52 | 613.41 | 1.3 | 23.0 |

| Ref: (Nepal Rastra Bnak, 2021/22) | |||||

In the evaluation period, revenue totaled Rs.613.41 billion, which included the sum that was given to province and municipal governments. In the review period, the tax and non-tax revenues were Rs.560.84 bn and Rs.52.57 bn, correspondingly (Table 1). This included Rs.23 bn in t - bills and Rs.29.50 bn in developmental securities, which the national govt raised in the review period. GoN's NRB balances remained at Rs.304.42 bn as of mid-Feb 2022, compared to Rs.200.18 bn at the same time in the previous year. The province governments' overall resource mobilization was maintained at Rs.89.07 billion throughout the review period. Regarding grants and revenues, the federal government transferred Rs.63.54 bn to provincial governments and generated Rs.25.53 bn in income from other sources during the evaluation period. Regional governments spent a total of Rs.49.31 billion during the study period.

Monetary Situation

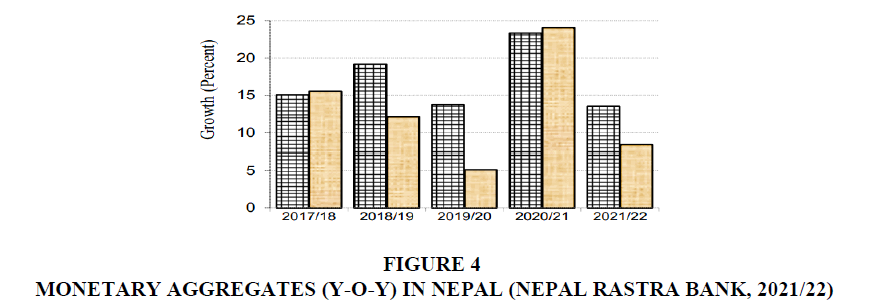

M2 (the broad measure of money) rose by 2.8 %during the review period, compared to a 10.3 %rise during the previous year's similar period. In mid-February 2022, M2 grew by 13.5% on a year-over-year basis (Figure 4). After correcting for foreign currency value gains/losses, the net foreign assets (NFA) declined by Rs. 247.03 bn (18.5%) in the review period, compared to a 7.3 %growth in the same time last year. According to the review period, reserve funds declined by 13.5%, compared to an 8.1%drop in the same time last year. Midway through the year 2022, Nepal Rastra Bank reported a 1 %year-over-year reduction in foreign reserves.

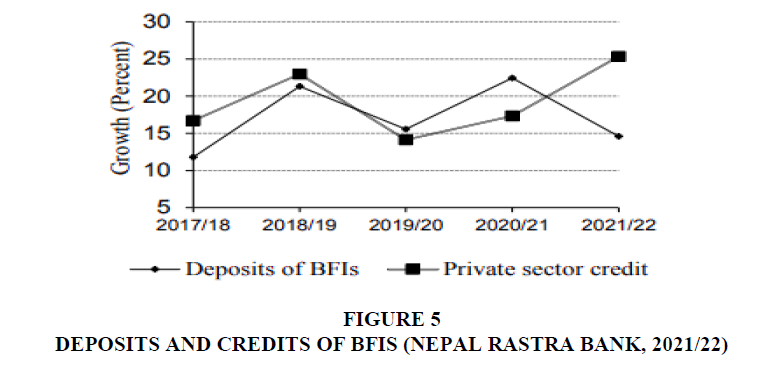

The rise in domestic credit during the review period was 9.3 percent, compared with an increase of 10.8 %during the same time last year. In mid-February 2022, domestic credit grew by 25.6 %year-over-year. Private industry claims in Monetary Sector rose by 12.9% in the review process compared with an increase of 14.0 %in the similar year-ago timeframe; by the middle of February 2022, these claims had grown 25.1 %year-over-year (Figure 5).

A 3.6 %rise in deposits at BFIs was recorded during the period under consideration, compared to a growth of 9.8 %during the same period in the preceding year. Deposits at BFIs grew by 14.6% on a year-over-year basis in mid-February 2022. In mid-February 2022, demand, savings, and fixed deposits make up 8.3 percent, 30.1 percent, and 54.6 %of total deposits, respectively. A year ago, these shares were 8.2 percent, 33.9 percent, and 48.9 %correspondingly. By the middle of February 2022, 38.8 % of BFI's total deposits were held in institutional accounts. In mid-February 2021, this percentage was 42.0 %. There were 239 BFIs active in this process as of mid-February 2022, after the implementation of the M&A transactions strategy aimed at increasing financial stability. As a result, 177 BFIs had their licenses canceled, leaving 62 BFIs in operation. By the middle of February 2022, financial institutions had opened branches in 750 of the 753 local levels. A year ago, there were 749 commercial bank branches on the local level. As of the middle of February 2022, the number of BFIs authorized by the NRB remained at 128. At the end of February of this year, there were 27 commercial banks, 17 development banks; 17 finance businesses; 66 microfinance financial institutions; and a single infrastructure development bank in operation. By the middle of February 2022, the number of BFIs locations had risen to 11,255 from the mid-July 2021 level of 10,683 (Table 2).

| Table 2 Deposits At Banks And Financial Institutions (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deposits | Mid July | Mid-February | ||

| 2021 | 2022 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| Demands | 10 | 10.4 | 8.2 | 8.3 |

| Saving | 31.9 | 34.2 | 33.9 | 30.1 |

| Fixed | 48.6 | 47 | 48.9 | 54.6 |

| Other | 9.5 | 8.4 | 9.0 | 7.0 |

| *(Nepal Rastra Bank, 2021/22) | ||||

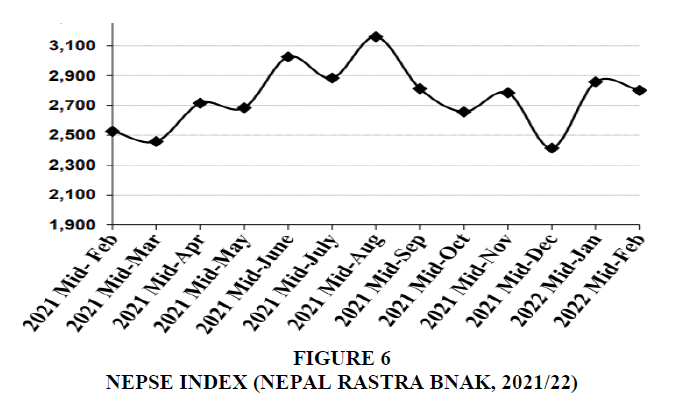

Capital Market

In mid-February 2022, the NEPSE index was 2801.6, up from 2526.9 in mid-February 2021. The mid-February 2022 stock market capitalization was Rs.3959.65 bn, compared to Rs.3406.17 bn in the mid-February 2021 market capitalization period. At the end of February 2022, NEPSE had 226 listed businesses, 143 BFIs, 47 hydroelectric businesses, 19 processing and manufacturing sectors, 5 restaurants, 5 financial institutions, 4 trading houses, as well as 3 other types of businesses. As of the middle of February 2021, there were 216 firms listed on NEPSE (Figure 6).

Current Developments in Microfinance Sector in Nepal

In the past couple of decades, Global Micro-finance, a monetary idea that has thrived, has been credited by multiple groups and organizations with their economic success in different development initiatives. For decades, thrift and loan societies and various savings clubs have been changing the economy for the underprivileged population, which was frequently ignored by commercial banks. Despite this, microfinance has not been as active as it once was (Dhungana et al., 2020). To make up for their losses, the numerous thrift and loan institutions formed cooperatives as well as other financial institutions focused on developing countries, like microcredit organizations, which supplied lending to rural residents who could not meet the high capital requirement of financial institutions. To help the poor, microfinance allows them to apply their survival skills, generate self-employment, boost family income, and enhance their quality of life. Shortly, 85 microfinance firms will be major players in the distribution of microcredit to the underprivileged. Microfinance has been a priority for financial institutions, banking institutions, and investment companies in Nepal. Nonblocking banking, rural offices, and a variety of microfinance services are being offered by them in Nepal (Dhungana et al., 2020). Table 2 shows the top Nepalese microfinance firms, together with their yearly profits per share. The microfinance industry's progress is shown in this article.

Self-employment is one of the finest outcomes of microfinance. For those who lack collateral but have indigenous talents and a strong desire for self-employment and income production, this organization offers assistance. Because of the increased earnings from their small initiatives, women who have been able to use microfinance services have gained economic and social empowerment. Together, the MFIs and wholesale lending institutions like RMDC have helped these women gain the knowledge and skills they need to succeed in locally viable income-generating industries (Anayo, 2011) shows in Table 3.

| Table 3 Microfinance Sector Development In Nepal |

||

|---|---|---|

| S.No | Microfinance Companies in Nepal | Earnings Per Share (In Rs.) |

| 1 | Jeevan Bikas Laghubitta Bittya Sanstha Ltd. | 132.02 |

| 2 | Mahila Laghubitta Bittya Sanstha Ltd. | 110.92 |

| 3 | Forward Microfinance Bittya Sanstha Ltd. | 108.48 |

| 4 | National Microfinance Bittya Sanstha Ltd. | 83.91 |

| 5 | Kalika Laghubitta Bittya Sanstha Ltd. | 53.71 |

| 6 | Global IME Laghubitta Bittya Sanstha Ltd. | 53.50 |

| 7 | Asha Laghubitta Bittya Sanstha Ltd. | 52.29 |

| 8 | Deprosc Laghubitta Bittya Sanstha Ltd. | 48.21 |

| 9 | Laxmi Laghubitta Bittya Sanstha Ltd. | 48.13 |

| Source: Unaudited Q2 Report, FY2078/79 | ||

Many women who participated in the microfinance program have become self-sufficient both socially and economically as a consequence of the information and skills they have gained and the revenue they have generated. Consequently, microfinance has emerged as a powerful strategy to alleviate poverty, particularly for women. Microfinance initiatives in Nepal have a strong regional focus and are aimed at the most vulnerable members of society. A microfinance program allowed the borrowers to save more money than non-borrowers who did not participate in the program (Khandker et al., 1998). The borrower can pay back their weekly payments and save more quickly with the extra money they have coming in. The spending habits of those who participate in microfinance programs are improved as a result of the program. Borrowers that join microfinance programs spend more on their health and children's education as well as more on savings and other investments, resulting in a better quality of spending. As a result, the greater rate of income is now going to investments, rather than consumer expenditures, as in the past. The poor's quality of life has improved as a result of their increased income via microfinance. Awareness about health and increased spending on quality things like health care, medical training, participation in seminars, and frequent sociability via center meetings have led to an increase in life expectancy and business skills and productivity.

Impact of Microfinance and Microcredit on Micro-Enterprise Development

Microfinance is a popular development tool, particularly in financial inclusion and poverty reduction (Rahman, 2020). Microfinance institutions (MFIs) apply a unique credit delivery mechanism that provides loans to the marginalized and disadvantaged people under the group-based lending system. The concept of microfinance became popular when Professor Muhammad Yunus, the founder of Grameen Bank, was awarded by Nobel Peace Prize in 2006. It helps enhance the socio-economic status of the poor and low-income people through a sustainable business model (Rahman, 2001; Rahman, 2010). Almost a global consensus is that microcredit to the poor is crucial for the twenty-first century's economic and social development (Microcredit Summit, 1998). The growth of a company might be stifled by a lack of capital (Malhotra et al., 2007). Financing for smaller businesses is more difficult to get by than for larger ones (Schiffer & Weder, 2001; Beck et al., 2002). For a company to grow its operations, innovate and invest in new manufacturing facilities and people, financing is required (OECD, 2006). As per the Global Findex database, almost half of the population is unbanked in Nepal (World Bank, 2017). This poor access to microcredit has greatly affected enterprise development and promotion (Rahaman, 2001).

Microfinance is considered an effective tool to access credit to the poor, marginalized, and low-income people. Most households are better off with microcredit programs. Still, its impact on income varies in magnitude and durability, and a sizeable proportion of clients find that their post-credit incomes stagnate or fall (Copestake et al., 2001; Mosley, 2001). Several studies find that microfinance helps reduce poverty, empowers women or other disadvantaged population groups, creates employment, and encourages microbusiness or enterprise creation. As per the Industrial Enterprises Act of Nepal, 2020, industries are classified into five groups: micro-enterprise, cottage industry, small industry, medium industry, and large industry. The registered (50.1%) and unregistered (49.9%) enterprises are almost equal in Nepal. Out of the unregistered enterprises, 52% are micro-enterprises, and the rest are small (5.2%), medium (3.9%), and large (2.5%) enterprises (CBS, 2019).

Entrepreneurs in small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) play a critical role in the global economy by providing employment, growth, and innovation. Many of Nepal's small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are undercapitalized, lack access to cutting-edge technology, and lack basic information about business prospects and marketing in the country (Pandey, 2004). Both the supply-side and demand-side factors point to a lack of financial support for MSMEs and the lack of business skills among MSME entrepreneurs. Because of high-interest rates, hefty collateral requirements, hassles connected with the procedure, a lack of knowledge, and insufficient institutional capacity, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have limited access to financing (NRB, 2019).

Access to microcredit, according to proponents, aids in the transformation of women into "entrepreneurs" (Sanyal, 2014). The lack of start-up money was the most significant impediment to disadvantaged people becoming more entrepreneurial. Small businesses and self-employment opportunities may be started by the impoverished using microcredit (Bateman et al., 2019). Financial, social, and human capital all play a crucial role in a woman's success in starting a micro-business (Hameed et al., 2020). Small companies' growth, efficiency, competitiveness, revenue, asset value, reducing poverty, and women's empowerment may all be used as indicators of the effectiveness of intervention programs for small enterprises (Yang, 2018).

It does not matter to micro-entrepreneurs whether the money comes from family, friends, or a specific financial institution; they just need it. Development policy arguments in developing nations continue to focus on the importance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The growth of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is considered a means of achieving more general economic and social goals, such as the reduction of poverty (Cook & Nixson, 2000). After productively using microcredit, microfinance has significantly improved the economic standing of those it has reached (Dhungana, 2018). There are many people who have very few connections and very little time to connect (Ozdemir et al., 2016).

Self-employment, increased productivity, and a rise in pay rates are all benefits of microfinance organizations (Wanjiku & Njiru, 2016). After participating in microfinance programs, the formation of micro-businesses, income levels, consumption expenditures, and customers' capital expenditures have all dramatically improved (Dhungana, 2016). Women's economic advancement boosted their self-esteem and self-respect. Microfinance is a kind of lending that gives small business loans to women entrepreneurs (Khanday et al., 2015). A study by Rehman et al. (2015) found that women's engagement in business improves their earnings as well as their savings, which in turn boosts their quarterly household income and other family resources.

Dhungana (2015) found that microfinance programs in Nepal have had a substantial impact on the micro-business or enterprise formation, job generation, occupational status, and income level of the population. According to previous studies, the microfinance sector is successful in reaching millions of impoverished people, providing them with financial services, and lowering their poverty levels (Simanowitz & Walter, 2002). Over time, impoverished borrowers benefit from microfinance programs that help them satisfy their urgent requirements (Khandker, 2001). According to Wright (Khandker, 2001) (Chan & Ghani, 2011), and Berhane and Gardebroek (2011), the beneficial effect of MF is large via raising income, improving family spending, and lowering vulnerability (Wright, 2000; Zaman, 2000; Salia & Mbwambo, 2014). There have been several studies looking at the link between loans and productivity. Overall, the data points to a beneficial influence on business productivity, with credit playing a major role (Levine, 1991; Bencivenga et al., 1995). This study shows that microcredit has a positive effect on a variety of socio-economic indicators, including the creation of new jobs (Arinaitwe 2006), income and expenditures of the target groups (Hietalahti & Linden, 2006), savings (Copestake et al., 2001), ownership of assets (Bhatt et al., 1999), as well as the standard of living for participants (Ang, 2004). Microcredit has been shown to boost the profitability of small businesses, according to several studies (Hietalahti & Linden, 2006; Copestake et al., 2001).

Opportunities of Microfinance in Nepal

A variety of pilot programs and efforts were launched in 1980 to bring banking and financial services to the poor and women in the microfinance sector, which had previously been supplied by cooperatives and conventional banks. Even if select groups of disadvantaged individuals were helped, these services were deemed useless in the long run. Not until India's Sixth Plan (1980/81-84/85) was it acknowledged as an official method for combating poverty. Despite this, the industry gained impetus once democracy was restored in 1991, and it has continued to grow since then. With the development of five Regional Development Banks (RDBs) in each Development Region based on the Grameen model, the government proceeded further to strengthen the Microfinance Institutions to offer financial services to the poor and women. After being privatized and regulated as a class 'D' financial institution, these Regional Development Banks (RDBs) became Microfinance Development Banks (MFDBs). Much private microfinance and non-profit organizations began offering microfinance programs in the early 2000s. Effective microfinance programs were launched by NGOs such as Nirdhan Utthan Bank and the Center for Self-help Development (CDF) under the Grameen Model. Chhimek Bikas Bank (CBB), Deprosc Bikas Bank (DBB), and Nerude Microfinance Development Bank Ltd. (NMDB) were all established as Microfinance Development Banks. Financial Intermediary NGOs (FINGOs) were established as a consequence of the legalization and licensing of community-based financial NGOs by the Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB). Microfinance institutions now serve the underprivileged in several different ways in Nepal.

Poverty Alleviation

At this point, destitution is one of the world's most pressing issues. Nepal is not an exception to the general rule, of course. Microfinance has been shown to lessen poverty. Aside from poverty reduction, the significance of microfinance is also acknowledged for its ability to diversify revenue sources; generate assets, and raise the stature and standing of women in society; increased income and asset levels are a result (Geetha et al., 2017).

Conductive Legal Environment

National Microfinance Policy, 2007 was released by the Nepalese government to promote the building of a conducive legislative environment and the required financial infrastructure for the ongoing growth of microfinance in Nepal.

Developed Professional Management

In the past few years, several high-quality commercial microfinance institutions with significant capacity building and professionally managed have emerged as a result of the adoption of best practices of their human resource department.

Availability of Domestic Sources

The mandated Deprived Sector Credit Program (DSCP) is a significant source of funding for microcredit initiatives.

Microfinance Insurance Products

A relationship between microfinance lenders and large insurance businesses has resulted in new solutions, such as micro-insurance product lines. More than a decade of organizational self-management of micro-insurance programs (not linked to an insurance firm) has been conducted in Nepal. The system may be replicated by new MFIs.

Opportunity for Commercial Banks

Financial institutions have much potential in the emerging industry of microfinance. Financial institutions have an excellent chance to invest their money because of the high percentage of recuperation and the high possibility of better profit.

Operating in a Professional Manner

It is now possible to gain useful microfinance best practices and successful microfinance stories from established MFIs functioning in the nation today.

Women Empowerment

As a result of microfinance, impoverished women now have access to finance via MFIs, NGOs, and other Nonbank Financial Institutions (NBFIs). The fact that so many of them have a stellar track record of on-time payments is noteworthy. It is feasible to make better use of resources in this manner, and this eventually helps the economy grow economically (Sharma, 2007).

Critical Issues in Nepal's Micro-Finance Circumstances and Their Association with Rapid Microfinance Development

Issues in Nepali microfinance are discussed in this section. It is clear from this overview that the administration and sponsors, as well as microfinance institutions, need to alter their policies and practices to address five major challenges. For state programs, revenue generated by the current amount of business is inadequate to meet their costs. Due to high loan losses incurred by government-sponsored initiatives, there is little hope that they will ever become financially viable. Debt recovery may be gauged by looking at repayment rates. Loan losses are not properly recorded in the books, and the real cost they represent is not taken into account (Lamichhane, 2020). In addition, the capital account in a microfinance firm is overstated because of interest accumulated on loans. Microfinance institutions lack strong managerial skills, accounting processes, and record-keeping, except for government-initiated schemes such as Rural Regional Development Banks (RRDBs). These groups may need financial help to get technical assistance and training. Some microfinance institutions benefit unfairly from government interest rate subsidies, which distort the market. Lending "internal money" at greater interest rates than "external funds" is the norm. Members' "ownership" of money has been shown to have a substantial impact on loan repayment and financial sustainability for microfinance firms (Karki et al., 2021).

There is a significant increase in the effective interest rates on loans since most customers cannot access their savings. A further consequence of borrowing is that the cost of loans rises as savings accumulate and constitute a larger fraction of the total loan balance. Nepal's tough geographic and economic conditions make it difficult to grow the number of loans and outreach. Accessible locations are the primary focus of most microfinance efforts. Inaccessible locations are difficult for institutions to reach. Some microfinance firms get government subsidies, while others do not, and this has led to cases of "encroachment" or unfair competition amongst the businesses that operate in the region. Microfinance institutions, especially those running government-initiated programs, have claimed that other organizations are snatching "worthy" borrowers and circulating inaccurate information about other firms (Paudyal, 2018). Many people are getting loans from many lenders, resulting in a larger risk of losing money and the need for additional services. NGOs and SCCs involved in microfinance face challenges because of gaps in the legal and policy framework, including a lack of an adequate organizational structure, a lack of ability to form apex organizations (federations), and a lack of access to government funding for non-registered organizations. Some NGOs and SCCs are unable to borrow money because of a lack of local financing facilities, while others can invest their surplus cash since they have no other place to put them. Most indigenous NGOs/SCCs have been unable to expand further because of a lack of financial sources and a tiny membership base. To carry out microfinance operations, many NGOs and SCCs backed by INGOs need a defined vision and mission statement. As a result of donor pressure, several of these organizations have launched savings and credit programs. Providing microfinance services is complicated, and many people do not comprehend this, resulting in ineffective and unprofitable initiatives. As a starting point for community development initiatives, these organizations rely on savings (Lamichhane, 2020).

Although these operations have resulted in large savings, relatively few INGOs have aided these institutions in obtaining finance. Government-mandated initiatives are very inefficient and lose a significant amount of money in loan repayments. In other circumstances, they seem to be the victims of political intervention in their activities. Non-profits organizations that get wholesale funding look to be more effective and have the possibility for long-term success. This leads to inefficient operations and higher operational expenses for many Nepali microfinance businesses. These organizations also have insufficient staff training programs, ineffective administration, a lack of credit discipline, and the delivery of social services alongside financial services. Increases in the number of customers have a substantial impact on the economies of scale. It is fairly uncommon for microfinance programs to lack the necessary outreach to help people attain financial independence.

Conclusion

We may infer from this brief examination that Nepal Rastra Bank has played a critical role in the establishment of an investment center and process to make microfinance available to the poor and disadvantaged on an easy and seamless basis. So many institutions have emerged to participate in microfinance operations utilizing it as an effective financial instrument to reduce poverty as a consequence of this. Micro-finance organizations have been unable to reach all of the individuals they have been aimed at. These institutions may participate in microfinance via a variety of rural financing programs, and the possibilities are almost limitless. To help the majority of impoverished people, micro and rural finance must first be accessible to the majority of people, and then it must be feasible, sustainable, and lucrative. It is also concluded that Nepal is moving towards microfinance development and face some problems which are a hurdle in the development of microfinance. These highlighted problems in literature should be sorted out by implementing the positive recommendations. So, that microfinance will grow more.

Recommendations

There are some recommendations for sorting out the critical issues that are associated with microfinance development in Nepal is following:

• Subsidized capital for on-lending, technical support, and governmental bank rate subsidies are all offered to microfinance organizations in Nepal. The majority of the time, these subsidies are regarded as essential for the growth of long-term social and financial intermediaries, especially for organizations operating in distant locations. However, interest rate subsidies are useless, distort the market, and should be abolished altogether. For the most part, subsidies should be used solely for the development of institutions and organizations' capacities, and in certain cases, for the initial capital amounts needed to start a lending business.

• There is a need for an expansion of financial services in the Hills. Hill area non-governmental organizations (NGOs/SCCs) should be supported via village banking models and community loan funds, according to the authors. It is possible to encourage Grameens to experiment with new ideas, such as hiring local contractor persons to provide services. To encourage groups to operate in distant places, more funding may be necessary. Cost-sharing initiatives, training in new skills, and capital funding are all examples of help that might be offered. The Terai region of Nepal is home to the majority of Nepal's microfinance institutions. Due to the subsidies some borrowers accept, certain institutions are accusing others of 'encroachment' because of the duplication of services they provide.

• For a business to be financially viable, it has to have a strong grasp of financial management, which includes ensuring that it has enough capital to fulfill credit demand, generating enough income to pay operational expenses, and producing useful and accurate accounting statements (financial reporting.) A microfinance organization's potential to achieve financial sustainability is hampered if it relies on government subsidies indefinitely.

• A microfinance institution must produce enough income to pay all of its expenses, as well as adequate surplus revenue to develop the capital base (retained profits) so that it may serve an expanding customer base and customers with increasing financial requirements.

• Microfinance institutions must decrease loan losses, establish more efficient operational processes (distribution techniques), and expand their reach if they are to become financially self-sufficient. Another recommendation is to raise prices until they cover all expenditures, taking into account how well services are delivered now.

References

Adams, D.W., & Von Pischke, J.D. (1992). Microenterprise credit programs: Deja vu. World development, 20(10), 1463-1470.

Arzeni, S., & Akamatsu, N. (2014). ADB-OECD study on enhancing financial accessibility for SMEs: Lessons from recent crises.

Adusei, M., & Adeleye, N. (2021). Start-up microenterprise financing and financial performance of microfinance institutions. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 1-24.

Akhter, J., & Cheng, K. (2020). Sustainable empowerment initiatives among rural women through microcredit borrowings in Bangladesh. Sustainability, 12(6), 2275.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nkamnebe, A.D., & Idemobi, E.I. (2011). Recovering of micro credit in Nigeria: Implications for enterprise development and poverty alleviation. Management Research Review, 34(2), 236-247.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Arinaitwe, S.K. (2006). Factors constraining the growth and survival of small scale businesses. A developing countries analysis. Journal of American Academy of Business, 8(2), 167-178.

Bhatt, N., Painter, G., & Tang, S.Y. (1999). Can microcredit work in the United States?. Harvard Business Review, 77(6), 26-26.

Beck, T., & Maksimovic, V. (2002). Financing patterns around the world: the role of institutions, 2905. World Bank Publications.

Bencivenga, V.R., Smith, B.D., & Starr, R.M. (1995). Transactions costs, technological choice, and endogenous growth. Journal of economic theory, 67(1), 153-177.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bateman, M., Blankenburg, S., & Kozul-Wright, R. (Eds.). (2018). The rise and fall of global microcredit: development, debt and disillusion. Routledge.

Berhane, G., & Gardebroek, C. (2011). Does microfinance reduce rural poverty? Evidence based on household panel data from northern Ethiopia. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 93(1), 43-55.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Glennerster, R., & Kinnan, C. (2015). The miracle of microfinance? Evidence from a randomized evaluation. American economic journal: Applied economics, 7(1), 22-53.

Banerjee, A., Karlan, D., & Zinman, J. (2015). Six randomized evaluations of microcredit: Introduction and further steps. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(1), 1-21.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Besley, T., & Cord, L. (Eds.). (2007). Delivering on the promise of pro-poor growth: Insights and lessons from country experiences. World Bank Publications.

Casper, K.L. (1994). The Women’s and Children’s Health Programs and Gender Equity in Banchtie Shekha. Evaluation Report for Ford Foundation.

Chassang, S., & i Miquel, G.P. (2009). Economic shocks and civil war. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 4(3), 211-28.

Cons, J., & Paprocki, K. (2010). Contested Credit Landscapes: microcredit, self-help and self-determination in rural Bangladesh. Third World Quarterly, 31(4), 637-654.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chapagain, R., & Dhungana, B.R. (2020). Does microfinance affect the living standard of the household? Evidence from Nepal. Finance India, 34(2), 693-704.

Chan, S.H., & Abdul Ghani, M. (2011). The impact of microloans in vulnerable remote areas: Evidence from Malaysia. Asia Pacific Business Review, 17(01), 45-66.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

CBS (2019). National economic census 2018. Centra Bureau of Statistics, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Copestake, J., Bhalotra, S., & Johnson, S. (2001). Assessing the impact of microcredit: A Zambian case study. Journal of Development Studies, 37(4), 81-100.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Cook, P., & Nixson, F. (2000). Finance and small and medium-sized enterprise development. Manchester: Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester.

Dhungana, B.R. (2016). Does microfinance transform the economic status of people? Evidence from western development region of Nepal, The Journal of University Grants Commission, 5(1), 35-48.

Dhungana, B.R. (2018). Impact of micro-finance on business creation: A case of Nepal. Journal of Nepalese Business Studies, 11(1), 23-34.

Dhungana, B. R. (2016). Does loan size matter for productive application? Evidence from Nepalese micro-finance institutions. Repositioning The Journal of Business and Hospitality, 1, 63-72.

Dhungana, B. R. (2015). Microfinance, micro-enterprises, and employment: A Case of Nepal. The International Journal of Nepalese Academy of Management, 3(1), 78-91.

Dhakal, C.P. (2020). Growth and Development of Small Business Through Microfinance Activities in Nepal. Interdisciplinary Journal of Management and Social Sciences, 1(1), 26-34.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Doepke, M., & Tertilt, M. (2019). Does female empowerment promote economic development?. Journal of Economic Growth, 24(4), 309-343.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dhungana, B.R., Chapagain, R., & Ranabhat, D. (2020). Effects of Microfinance Intervention on Multiple and Non-multiple Financing Clients: A Case of Gandaki Province of Nepal. Journal of Nepalese Business Studies, 13(1), 49-61.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Goetz, A.M., & Gupta, R.S. (1996). Who takes the credit? Gender, power, and control over loan use in rural credit programs in Bangladesh. World development, 24(1), 45-63.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Geetha, C., Savarimuthu, A., & Majid, A.A. (2017). Assessing Financial Returns on Microloans from Economic, Social and Environment Impact: A Case in Kota Kinabalu. Malaysian Journal of Business and Economics (MJBE).

Ghalib, A.K., Malki, I., & Imai, K.S. (2015). Microfinance and household poverty reduction: Empirical evidence from rural Pakistan. Oxford Development Studies, 43(1), 84-104.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hietalahti, J., & Linden, M. (2006). Socio-economic impacts of microfinance and repayment performance: a case study of the Small Enterprise Foundation, South Africa. Progress in development studies, 6(3), 201-210.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hameed, W.U., Mohammad, H.B., & Shahar, H.B.K. (2020). Determinants of micro-enterprise success through microfinance institutions: a capital mix and previous work experience. International Journal of Business and Society, 21(2), 803-823.

Hermes, N., & Hudon, M. (2018). Determinants of the performance of microfinance institutions: A systematic review. Journal of economic surveys, 32(5), 1483-1513.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hashemi, S.M., Schuler, S.R., & Riley, A.P. (1996). Rural credit programs and women's empowerment in Bangladesh. World development, 24(4), 635-653.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Khandker, S.R., Samad, H.A., & Khan, Z.H. (1998). Income and employment effects of microcredit programs: Village-level Evidence from Bangladesh. Journal of Development Studies, 35(2), 96-124.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Khanday, M.I., Shah, B.A., Mir, P.A., & Rasool, P.A.R.V.A.I.Z. (2015). Empowerment of women in India-historical perspective. European Academic Research, 2(11), 14494-14505.

Khandker, S. (2001). Does micro-finance really benefit the poor? Evidence from Bangladesh. In Asia and Pacific Forum on Poverty: Reforming Policies and Institutions for Poverty Reduction ,14.

Khanal, S., & Bhatta, S. (2022, January). The Evaluation of Intervention Programs in Girls’ Capability Development Opportunities in Nepal. In The Educational Forum, 1-13. Routledge.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Karki, K.K., Dhungana, N., & Budhathoki, B.B. (2021). Breaking the Wall of Poverty: Microfinance as Social and Economic Safety Net for Financially Excluded People in Nepal. Molung Educational Frontier, 11, 26-53.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lamichhane, B.D. (2020). Microfinance for Women Empowerment: A Review of Best Practices. Interdisciplinary Journal of Management and Social Sciences, 1(1), 13-25.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Levine, R. (1991). Stock markets, growth, and tax policy. The journal of Finance, 46(4), 1445-1465.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Malhotra, M., Chen, Y., Criscuolo, A., Fan, Q., Hamel, I.I., & Savchenko, Y. (2007). Expanding access to finance: Good practices and policies for micro, small and medium enterprises. WBI Learning Resource Series.

Microcredit Summit (1998). Draft declaration, Washington, DC: Result Education.

Mosley, P. (2001). Microfinance and poverty in Bolivia. Journal of development studies, 37(4), 101-132.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

NRB (2019). Nepalma Sana tatha majhaula udhyamma bittiya sadhan parichalan (SMEs Financing in Nepal). Kathmandu: NRB.

Ozdemir, S.Z., Moran, P., Zhong, X., & Bliemel, M.J. (2016). Reaching and acquiring valuable resources: The entrepreneur's use of brokerage, cohesion, and embeddedness. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(1), 49-79.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

OECD (2006). Financing SMEs and entrepreneurs. OECD Policy Brief. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

Oli, S.K. (2018). Impact of microfinance institutions on the economic growth of Nepal. Asian Journal of Economic Modelling, 6(2), 98-109.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pandey, G.D. (2004). Problems and prospects of SMEs in Nepal. In N. Dahal and B. Sharma (Eds.), WTO Membership: Opportunities and Challenges for SMEs in Nepal. Kathmandu: SMEDP and SAWTEE.’

Paudyal, R. (2018). Microfinance and socio-economic development: an integrated approach in Nepal (Doctoral dissertation, University of the Sunshine Coast).

Pignatel, I., & Tchuigoua, H. T. (2020). Microfinance institutions and International Financial Reporting Standards: an exploratory analysis. Research in International Business and Finance, 54, 101309.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rahaman, A. (2001). Women and microcredit in rural Bangladesh: Anthropological study of the rhetoric and realities of Grameen bank lending. Westview Press.

Rahman, M.T. (2020). Controlling for self-selection Bias in evaluating the impact of microcredit programs: Evidence from Asa Bangladesh. The Journal of Developing Areas, 54(4).

Rehman, H., Moazzam, D.A., & Ansari, N. (2020). Role of microfinance institutions in women empowerment: A case study of Akhuwat, Pakistan. South Asian Studies, 30(1),107-125.

Rahman, S. (2010). Consumption difference between microcredit borrowers and non-borrowers: A Bangladesh experience. The Journal of Developing Areas, 43(2), 313-326.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Simanowitz, A., & Walter, A. (2002). Ensuring Impact: Reaching the Poorest While Building Financially Self-Sufficient Institutions, and Showing Improvement in the Lives of the Poorest Families: Summary of Article Appearing in Pathways Out of Poverty: Innovations in Microfinance for the Poor (No. 1762-2016-141572).

Schiffer, M., & Weder, B. (2001). Firm size and the business environment: Worldwide survey results. IFC- Discussion Paper 43. International Finance Corporation, Washington D.C.

Sanyal, P. (2014). Credit to capabilities: A sociological study of microcredit groups in India. Cambridge University Press.

Salia, P.J., & Mbwambo, J.S. (2014). Does microcredit make any difference on borrowers’ businesses? Evidences from a survey of women owned microenterprises in Tanzania. International Journal of Social Sciences and Entrepreneurship, 1(9), 431-444.

Shrestha, P.K. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 on Microfinance Institutions of Nepal. Research Gate.

Sharma, P. R. (2007). Micro-finance and women empowerment. Journal of Nepalese Business Studies, 4(1), 16-27.

World Bank (2017). The global index database 2017.

Wanjiku, E., & Njiru, A. (2016). Influence of microfinance services on economic empowerment of women in Olkalou constituency, Kenya. International Journal of Research in Business Management, 4(4), 67-78.

Wright, G.A N. (2000). Microfinance systems: Designing quality financial services for the poor. Zed Books.

Yang, W. (2018). Empirical study on effect of credit constraints on productivity of firms in growth enterprise market of China. J. Financ. Econ, 6, 173-177.

Zaman, H. (2000). Assessing the poverty and vulnerability impact of microcredit in Bangladesh: A case study of BRAC. The World Bank, Washington DC.

Received: 22-June-2022, Manuscript No. AEJ-22-12144; Editor assigned: 23-June-2022, PreQC No. AEJ-22-12144(PQ); Reviewed: 30-June-2022, QC No. AEJ-22-12144; Revised: 08-July-2022, Manuscript No. AEJ-22-12144(R); Published: 12-July-2022