Review Article: 2025 Vol: 29 Issue: 1S

Analyzing the Effect of External and Internal Influencers on Compulsive Buying Behavior in Egypt's Fashion Market

Pakinam Nazmy, American University in Dubai

Lama Blaique, American University in Dubai

Subramaniam Ponnaiyan, American University in Dubai

Citation Information: Nazmy, P., Blaique, L., & Ponnaiyan, S. (2024). Analyzing the effect of external and internal influencers on compulsive buying behavior in egypt's fashion market. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 29(S1), 1-18.

Abstract

The main aim of this study is to identify the relationships between internal (self-esteem, materialism, and impulsive buying) and external (sales promotion, advertising, and credit card misuse) factors that influence consumers' compulsive buying behaviours in Egypt’s fashion industry. Internal and external factors are assumed to positively influence consumers' compulsive buying behaviour; however, a limited number of studies have tested these relationships. This study addresses this gap in the literature. A total of 373 questionnaires were distributed among staff at different universities in Egypt, using proportionate quota sampling. The data collected from the survey were analyzed using structural equation modelling. The results indicate that materialism, impulsive buying, and credit card misuse positively influence Egyptian consumers’ compulsive buying behaviour in the fashion industry. Low self-esteem, sales promotion, and advertisements do not affect compulsive buying behaviour. This study will benefit marketers and fashion brand managers in the emerging Egyptian market by developing the most appropriate marketing strategies, while simultaneously trying to reduce the negative consequences of compulsive buyers.

Keywords

Compulsive Buying, Self-Esteem, Materialism, Advertising, Sales Promotions, Credit Card Misuse, Fashion, Impulsive Buying.

Introduction

Clothing and other fashion related products are considered an obvious illustration of status consumption, thus some consumers who are fashion-oriented might tend to be more compulsive buyers (Park & Burns, 2005). Fashion buyers are more aware of how they look and appear in public; therefore, they associate buying fashion brands with prestige and recognition (Lavuri, 2021). Compulsive buyers usually purchase fashion-related products (clothing, jewelry, and accessories) more regularly than do normal buyers. Customers may compulsively purchase fashion products because this purchasing behavior helps them match their perceptions of themselves, makes them feel accepted and desired by society, and represents their identities. Fashion brands take advantage of customers with compulsive buying tendencies by offering fast fashion products that require compressed production time. Compulsive customers are likely to demand new products (Johnson & Attmann, 2009).

Compulsive buying is prevalent among customers at a rate between 2% and 16.4% in developed nations. However, it is higher in developing nations at a rate between 2% and 26.1%. Although such emerging economies make up around 80% of the world's consumers, the knowledge about the phenomenon of compulsive buying behavior in these parts of the world is still limited (Moon et al., 2022).

Studying the factors that influence consumer’s compulsive buying behavior of fashion brands in a Non-Western environment is crucial given the global shift of countries towards becoming more consumer-oriented societies. After examining Egyptian consumers' intentions to purchase global luxury fashion brands, it was found that numerous European and American brands faced severe competition in their domestic markets and began looking for new markets to grow. Egypt has emerged as a profitable market for investment as the luxury industry and has grown increasingly in recent years and has the potential for further growth (Khalifa & Sahn, 2013). In the past decade, there has been obvious growth in shopping malls, especially in new cities in Egypt. Wholesale and retail businesses are the second largest contributors to the Egyptian economy after manufacturing, accounting for 14% of GDP in 2019/20. The sector is prepared for steady growth with malls finally moving from traditional urban centers to new cities (American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt, 2021). This rapid growth has caused Egyptian consumers to be more oriented toward foreign fashion brands and more eager to purchase them. Due to improved economic conditions, Egypt is becoming a desirable market for luxury goods from across the world (Talaat, 2022). Many businesses have seen consistent growth over the past few years, and there are even more predictions of higher future growth (El Din & El Sahn, 2013). Egypt now ranks 13th globally in terms of favourable retail markets (Abdellatif, 2014).

Compulsive buying pertains to a person’s tendency to purchase things that he or she does not need and cannot afford. Compulsive buying is defined as “a chronic, repetitive purchasing that becomes a primary response to negative events or feelings” (O’Guinn & Faber, 1989). Previous research suggests that several factors such as psychological, social, genetic, and cultural can help explain consumers' compulsive buying behavior. Compulsive buying behavior can cause consumers to spend more than they can afford, which is one of the main reasons for credit card debts. People tend to purchase unnecessary and expensive products to conceal their low self-esteem and to be more socially accepted by others (Omar et al., 2014).

Although many studies have examined consumers’ compulsive buying behavior and the factors influencing it in different parts of the world, limited research has examined the factors influencing consumers’ compulsive buying in the unique Egyptian socio-cultural context. Considering that cultural norms, societal pressure, psychological factors significantly influence consumer behavior (Moon et al., 2022), understanding how these factors interact within the socio-cultural landscape of Egypt is important for developing effective interventions and marketing strategies. Additionally given the Egyptian market's enormous potential (Talaat, 2022) and the limited information available about the Egyptian consumers, more thought must be given to understanding the factors influencing Egyptian consumer's compulsive buying behaviour in the fashion industry. Thus, the main aim of this study is to address this research gap to help marketers and consumer behavior researchers understand the significance of each factor to develop informed business decisions and create the most appropriate marketing strategies. The study adds to our understanding of cross-cultural consumer behavior by examining compulsive purchase behavior within the Egyptian fashion sector. Going beyond Western-centric perspectives, this research can create a more inclusive and thorough understanding of consumer behavior across diverse markets. Moreover, insights gained from studying compulsive buying behaviour in Egypt can help marketers adapt global fashion trends to local preferences. This adaptation is crucial for global brands to maintain a balance between a standardized global image and the need for localization to meet diverse consumer needs. Therefore, this study attempts to empirically test several antecedents of compulsive buying behavior of consumers in Egypt’s fashion industry while utilizing the model of consumer behavior as the study’s theoretical framework.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The second section presents the literature review and the research model. The third section explains the methodology used in the study. This is followed by the results and discussion section. Finally, the paper concludes with implications for the practice, future research directions and limitations.

Literature Review

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework for this study is the model of consumer behavior (MoCB). The model proposes that there are different factors influencing consumer’s buying decisions. Marketing and environmental stimuli such as pricing, promotion, distribution, political, legal, social, and other factors penetrate the buyer's awareness and impact their decision-making process. The model also highlights the importance of studying consumer’s psychology, traits, and characteristics as these factors have significant impact over the consumer’s interest in purchasing a product or service (Kotler & Armstrong, 2019). The model stems from the stimulus-response (S-R) model and is heavily used in investigating the real and reasonable consumption process (Kotler & Armstrong, 2011). Based on this model and the several factors influencing compulsive buying that have been studied in previous studies, researchers classified the factors influencing compulsive buying behaviour under two main categories external and internal. The external factors include brand’s sales promotions, advertising, and credit card usage. While the internal factors pertain to the consumer’s psychology and characteristics and they include holding materialistic values, impulsive buying tendencies, and self-esteem.

This model has proven to offer a better understanding of the consumer’s buying behavior and the factors influencing it. It has been utilized by various studies attempting to understand health factors that influence consumer behavior, consumer behavior under the conditions of technological changes and the impact of social-environmental factors on consumer behavior (Huang, et al., 2022; Letunovska, et al., 2021; Коноваленко, 2020; Yegina et al., 2020). The MoCB is deemed an appropriate theoretical framework for this study since it will aid in expanding knowledge and empirically examining the effect of several internal factors such as self-esteem, materialism, and impulsive buying and external ones namely sales promotion, advertising, and credit card misuse that may influence consumers' compulsive buying behaviours in the Egyptian context.

Compulsive Buying

Compulsive buying could be described using different terminologies such as, obsessive consumption, buying mania, compulsion, or even addiction. It is considered by many scholars as a psycho-pathological disorder that causes individuals to purchase uncontrollably, which in return might lead to financial and psychological problems (Harnish et al., 2021; Tarka & Harnish, 2023).

Previous research proposed that consumers who tend to be compulsive buyers are trying to overcome negative emotions and anxiety. Once consumers feel relieved after purchasing, there is a tendency that this behavior will be repeated whenever they feel anxious again (Khare, 2013). Compulsive buyers tend to have low self-esteem and high anxiety levels (Kothari &Mallik, 2015). Therefore, they are always motivated to purchase compulsively to avoid negative feelings and to boost their self-esteem.

The current study focuses on the compulsive buying behavior of customers in a physical store environment.

Self Esteem

Self-esteem is defined as an individual's feelings about their own value or worth, it is the degree of positivity of the self-concept. Self-esteem relates to how an individual interprets how others think about him/her (Omar et al. 2014). According to the self-determination theory, self-esteem varies from true to contingent. True self-esteem is related to stable individual traits that are not linked to meeting external standards or other people's approvals. While individuals with high contingent self-esteem scores tend to care more about how others perceive them and try to meet external standards. They also tend to base their self-worth on their physical appearance and social state (Biolcati, 2017).

Previous studies have concluded that there is a negative relationship between self-esteem and compulsive buying behaviors (Biolcati, 2017; Omar et al., 2014; Yurchisin & Johnson, 2004). Individuals with low self-esteem tend to purchase more products to boost self-esteem and reduce anxiety. For instance, Yurchisin & Johnson (2004) found a relationship between uncontrollable consumption and social status. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis (H1):

H1: Low Self-esteem positively affects consumers’ compulsive buying behavior.

Materialism

In recent years, many researchers have become interested in the role of materialism in developing consumer behavior. Materialism is directly related to various types of personal and social insecurities. It has been argued that materialism is a demonstration of deep, unsatisfied psychological needs (Sharif and Khanekharab, 2017). Materialism is the stage in which individuals begin to believe that possessing certain material goods is essential for enjoyment in life (Islam et al., 2017; Khare, 2014). It is defined “as the importance ascribed to the ownership and acquisition of material goods in achieving major life goals or desired states” (Xu, 2008, p. 39).

Previous studies have affirmed a positive relationship between materialism and compulsive buying (Islam et al., 2017; Villardefrancos and Otero-López 2016; Pham et al., 2012; Mueller et al., 2011; Yurchisin and Johnson, 2004) For example, in their recent study conducted on university students, Villardefrancos and Otero-López (2016) found a positive relationship between holding materialistic values and being a compulsive buyer. Consumers with materialistic characteristics who assume that the purchase of material goods is the main objective in life and is considered to symbolize success and happiness are more likely to develop compulsive buying behaviour through time (Yurchisin & Johnson, 2004; Dittmar, 2005). Thus, hypothesis (H2) postulates the following:

H2: Materialism positively affects consumers' compulsive buying behavior.

Impulsive Buying

Impulsive buying can be defined as unplanned buying, where consumers tend to purchase items; they never plan to buy in the first place based on a spontaneous urge (Badgaiyan et al., 2016; O'Guinn & Faber, 1989). There are four types of impulse buying: planned, reminded, suggestion or fashion-oriented, and pure. Planned impulsive buying occurs when the customer is planning to purchase some items, but the brand or product category has not yet been determined. Product determination depends on sales promotions and discounts inside a store. Reminded impulse buying occurs when the buyer is reminded of a specific need for a product inside a store. Pure impulse buying, which is sometimes referred to as an escape purchase, occurs when the customer purchases something purely out of impulse. Finally, suggestion or fashion-oriented impulse, is when the customer purchases the fashion product based on self-suggestion, although he or she has never tried it before (Muruganantham & Bhakat, 2013).

It is very critical to distinguish between compulsive and impulsive behaviours. Impulsive behaviour has been linked with irresponsible judgments that lead to incompatible behaviour. In other words, impulsive buying is a way of escape from the normal buying pattern. Compulsive buying, on the other hand, is more related to permanent purchase behaviour that can cause addiction, (Khare, 2013). Another way to distinguish between impulsive and compulsive buyers is by looking at their motives. Impulsive buyers tend to be motivated by external causes such as a product placed near the cashier. While compulsive buyers tend to be motivated by an internal cause such as stress (Johnson & Attmann, 2009).

Several studies examined the relationship between compulsive and impulsive buying behaviour. The results of these studies revealed that consumers who have the tendency to purchase items impulsively are more likely to develop a tendency to become compulsive buyers (Vogt et al., 2015; Omar et al., 2014; Billieux et al., 2008; O’Guinn and Faber, 1989;). Although by definition compulsive buying is considered a chronic condition and impulsive buying is suggested to be a temporary abnormal behaviour, it is possible to assume that compulsive buyers begin engaging in impulsive purchases but in the long run this behaviour provides sufficient positive reinforcements to become the normal response to negative feelings. (O’Guinn & Faber, 1989). Based on this, we propose the third hypothesis.

H3: Impulsive buying positively affects customers' compulsive buying behaviour.

Credit Card Misuse

Most people depend heavily on credit cards for their daily purchases. Paying using credit card is becoming more convenient and easier. Unfortunately, consumers sometimes use credit cards recklessly and pay the lowest possible amount on each card they own, eventually increasing their credit card debt. Consumers tend to spend more time buying more expensive products and services, knowing that they do not have to pay for them immediately. Credit card debt can cause anxiety and health problems. Joireman et al. (2010) found that approximately 90% of college seniors own at least one credit card, whereas approximately 56% own up to four or more cards. Credit card misuse is defined as excessive and irresponsible spending on a credit card that causes credit card debt. Consumers misuse credit cards when they perceive money to be a source of power or status (Joireman et al., 2010).

Several studies have examined the relationship between credit card debts and compulsive buying tendencies (Aslanoğlu & Korga, 2017; Simanjuntak & Rosifa, 2016: Joireman et al., 2010). Aslanoğlu & Korga (2017) concluded that credit card owners tend to spend more time and buy more expensive products and services, knowing that they will not have to pay for them immediately. In other words, owning a credit card increases the tendency to become a compulsive buyer. Joireman et al. (2010) found that compulsive buyers who concentrate on increasing instant consequences face a greater risk of substantial credit card debts. The more frequently working women misuse their credit cards, the higher the probability of developing compulsive buying behaviour (Simanjuntak & Rosifa, 2016). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Credit card misuse promotes consumers' compulsive buying behaviour.

Sales Promotion

Mendez (2012) believes that the best way to classify customer sales promotions is to divide them into monetary and nonmonetary categories. Monetary promotions include incentives, such as price discounts, rebates, and coupons. By contrast, non-monetary promotions include samples, games, contests, and sweepstakes.

After purchasing, compulsive buyers experience negative feelings such as guilt, embarrassment, or even regret. Their conspicuous buying behaviour might also lead to serious financial and social consequences, such as credit card debt as discussed in the previous section. Thus, they are prone to overcome their guilt by purchasing products that cost them less. Moreover, sales promotions may enable compulsory buyers to experience hedonic shopping benefits. Compulsive buyers are more likely to focus on paying lower prices and become more price-sensitive than non-compulsive buyers (Kukar-Kinney et al. 2012). Previous studies explain that price discounts are the most effective promotional tool that can trigger compulsive buying (Obeid, 2015; Wang & Jing, 2015). Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5: Sales promotion positively affects consumers' compulsive buying behaviour.

Advertising

Advertising is one of the most effective communication tools that helps deliver the right message at the right time to targeted consumers. Many marketers use different forms of advertising such as T.V., radio, and billboards advertisements to reach different types of customers. Advertising is any paid form of non-personal presentation and promotion of ideas, goods, and services. Among the many components of integrated marketing communication, advertising tends to have the most powerful effect on how consumers perceive a product, because it is the fastest and easiest method to inform consumers about any product. It can also reduce the barriers and difficulties faced by an organization and its consumers (Rahmani et al., 2012). Many studies have concluded that advertisements can significantly influence consumers' compulsive buying behaviour. Ampofo (2014) explored the impact of advertisements on consumer buying behaviour and concluded that ads tend to positively affect consumers' buying behaviour. Attitudes toward advertising considerably affect compulsive buying tendencies. Consumers with positive attitudes toward advertisements developed by a specific firm tend to be more compulsive than those who do not. By comparing compulsive and non-compulsive buyers, buyers’ advertisements appear to influence compulsive buyers more than non-compulsive buyers (Yuksel & Eroglu, 2015). Thus, the last hypothesis postulates the following.

H6: Advertisements positively affect the consumer's compulsive buying behaviour.

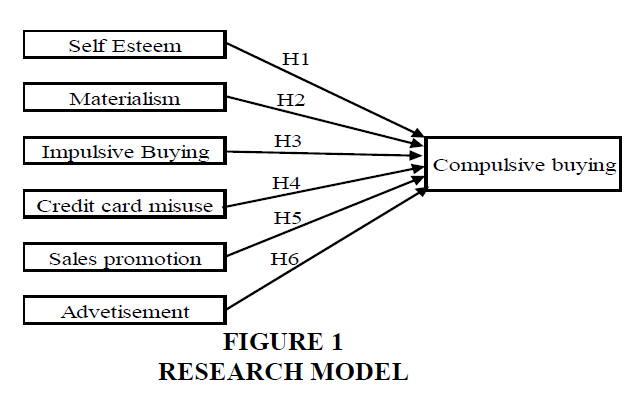

Overall, the proposed study has six hypotheses: Figure 1 depicts the conceptual model and research hypotheses discussed above. The next part of this study presents the methodology.

Research Methodology

Data were collected using preexisting and validated scales from the literature. The questionnaire was divided into three sections: The first section consisted of six questions measuring the two independent variables, which are the internal (impulsive buying tendency, self-esteem, and materialism) and external factors (credit card misuse, sales promotion, and advertising). The second section consisted of four items that measuring the dependent variable, which is the consumer’s compulsive buying behaviour. The last section consisted of demographic questions.

Data Collection and Sample

The survey was distributed among 400 staff at universities in Cairo using a non-probability proportionate quota sampling technique. 373 questionnaires were collected from the respondents. Therefore, the response rate was 92.5 %. Around 70% of the survey was self-administered to ensure a clear understanding of the questions by the respondents. The remaining 30% were mailed to the respondents who could not be reached due to the COVID19 pandemic restrictions. The collection of data started in January 2021 and ended in July 2021.

The study’s sample is made up of staff in universities in Cairo, Egypt. University employees come from different educational backgrounds, age groups, gender, and income levels, offering a diverse pool of experiences and perspectives. The diversity in the characteristics of the sample can enhance research finding and help in understanding the relationship between the variables. In addition, university staff are working individuals who own credit cards and have control over their purchasing decisions. Unlike in other countries, Egyptian undergraduate students depend on their parents for money and do not hold credit cards; therefore, undergraduate students would not be the right source for the proposed study.

Measures

All measured items were assessed on a five-point Likert scale where 1 represents strongly disagree and 5 represents strongly agree. The scale used for self-esteem was adopted from Rosenberg (1965). The scale used to measure materialism was adopted from Richins & Dawson (1992). Impulsive buying was measured using a scale from Rook & Fisher (1995). The measurement scale that was used to measure credit card misuse was adopted from Roberts & Jones (2001). As for sales promotions it was measured using a scale from Washburn & Plank (2002). The scale from Buil et al (2013) was used to measure advertising. Finally compulsive buying was measured using a scale from Faber &O’Guinn (1992).

Data Analysis and Results

Demographic Profile

The final sample comprised 373 participants; 76.9% were women, and 23.1% were men. 10.5% of the participants were between 20–25 years old, 29.8% were between 25–30 years old, 30.8% were between 30–35 years old, 14.2% were between 35–40 years old, 4.6% were between 40–45 years old, and 10.2% were above 45 years of age. The monthly income characteristics show that 5.9% earn less than 5000 LE (Egyptian pound), 40.5% earn 5000 LE to less than 10,000 LE, 29.8% earn 10,000 to less than 20,000 LE, and 23.9% earn over 20,000 LE (Table 1).

| Table 1 Demographic Profile | ||||||

| Gender | Frequency | Percentage | Age | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Male | 86 | 23.1 | 20 to less than 25 | 39 | 10.5 | |

| Female | 287 | 76.9 | 25 to less than 30 | 111 | 29.8 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 30 to less than 35 | 115 | 30.8 | |

| • | • | • | 35 to less than 40 | 53 | 14.2 | |

| • | • | • | 40 to less than 45 | 17 | 4.6 | |

| • | • | • | 45 or above | 38 | 10.2 | |

| • | • | • | Income (monthly) | • | ||

| • | • | • | a. Less than 5000 | 22 | 5.9 | |

| • | • | • | b. 5000 L.E to less than 10,000 L.E | 151 | 40.5 | |

| • | • | • | c. 10,000 L.E to less than 20,000 L.E | 111 | 29.8 | |

| • | • | • | d. Over 20,000 L.E | 89 | 23.9 | |

Measurement Model Analysis

In line with Chin (2009), a two-step procedure to test the hypotheses was used. The first step was to analyze the validity and reliability of the research instrument by examining the validity and reliability of the measurement model through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The second step was to test the structural model using AMOS 28.

Reliability and Validity

Hair et al. (2014) recommends testing convergent and discriminant validity to assess the validity and reliability of a research instrument. Convergent validity measures how individual items correlate with their respective constructs, whereas discriminant validity refers to the extent to which a construct is genuinely distinct from others. According to Hair et al. (2014), composite reliability values are between 0.60 and 0.70, and the average variance extracted (AVE) is greater than 0.5. However, according to Fornell and Larcker (1981), it is acceptable to ensure adequate convergent validity even if a construct has an AVE of less than 0.5, but a composite reliability of more than 0.6 to ensure adequate convergent validity. Discriminant validity can be established when the value of the average variance extracted from each latent variable is greater than the squared correlation between the latent variable and all other variables (Huang et al., 2013; Lam 2012; Fornell and Larcker, 1981)

Table 2 presents the results of the convergent validity tests. A cutoff for statistical significance of the factor loadings of 0.5 was used since loadings of 0.5 or greater are also considered practically significant ( et al., 2010). In our model, we included 30 items and found that only five items had a factor loading below 0.5. These items are Mate5, ccmi1, salp2, salp4, and comp 4, with factor loadings of 0.345, 0.481, 0.343, 0.249, and 0.342, respectively. We removed these five items to obtain the final factor loadings and re-evaluated the factor loading for the remaining 25 items. The final factor loadings for these 25 items are shown in Table 2 without any asterisk (*) marks. The composite reliabilities of all seven constructs were greater than 0.6. The AVE values of self-esteem, impulsive buying, sales promotion, and advertisements were above 0.50, while materialism, credit card misuse, and compulsive buying had AVE values of 0.479, 0.4,16, and 0.418, respectively. However, materialism, credit card misuse, and compulsive buying have composite reliability values of 0.7851, 0.7366, and 0.6823, respectively, implying that the proposed model has adequate convergent validity (Huang et al., 2013; Fornell and Larcker., 1981). In addition, the minimum Cronbach's alpha value was 0.69, which is within the acceptable threshold (>0.6) recommended by Churchill (1979), and close to the value (>0.70) as recommended by Nunnally (1978). The acceptable factor-loading values, composite reliability, and Cronbach's alpha demonstrate that the proposed model has convergent validity.

| Table 2 Results of the Measurement Model | ||||||

| Construct/item | Mean | SD | Factor | AVE | Composite | Cronbach's alpha |

| loading | Reliability (C.R) | |||||

| Self-esteem | 0.519 | 0.7633 | 0.76 | |||

| (self1) I feel that I have a number of good qualities. | 4 | 0.764 | 0.668 | |||

| (self2) I am able to do things as well as most people. | 3.92 | 0.863 | 0.752 | |||

| (self3) I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others. | 3.92 | 0.944 | 0.738 | |||

| Materialism | 0.479 | 0.7851 | 0.78 | |||

| (mate1) I admire people who own expensive homes, cars, and clothes. | 2.62 | 0.965 | 0.69 | |||

| (mate2) I like to own things that impress people. | 2.88 | 1.08 | 0.777 | |||

| (mate3) I always pay attention to material objects that others own. | 2.6 | 1.128 | 0.684 | |||

| (mate4) The things I own say a lot to others in terms of how my life is. | 3.09 | 1.191 | 0.608 | |||

| (mate5) Buying things gives me a lot of pleasure. | 3.94 | 0.965 | 0.345* | |||

| Impulsive Buying | 0.582 | 0.8735 | 0.87 | |||

| (impu1) I often buy things spontaneously. | 3.21 | 1.146 | 0.754 | |||

| (impu2) I often buy things without thinking. | 2.59 | 1.143 | 0.798 | |||

| (impu3) Most of the time I buy things on the spur of the moment. | 2.89 | 1.121 | 0.842 | |||

| (impu4) I do not plan most of my purchases. | 2.81 | 1.236 | 0.74 | |||

| (impu5) I am always reckless about what I buy. | 2.27 | 1.049 | 0.668 | |||

| credit card misuse | 0.416 | 0.7366 | 0.72 | |||

| (ccmi1) I am less concerned with the price of a product when I use a credit card | 2.84 | 1.252 | 0.481* | |||

| (ccmi2) I am more impulsive when I shop with credit cards. | 2.99 | 1.213 | 0.555 | |||

| (ccmi3) I am always late in making payments on my credit cards. | 2.28 | 1.213 | 0.688 | |||

| (ccmi4) I spend over my available credit limit most of the time. | 2.08 | 1.189 | 0.76 | |||

| (ccmi5) I often take cash advances on my credit cards. | 2.24 | 1.246 | 0.553 | |||

| Sales Promotions | ||||||

| (salp1) This brand frequently offers price discounts | 3.33 | 0.871 | 0.685 | 0.501 | 0.7468 | 0.74 |

| (salp2) Promotions helps me faster purchase decisions | 3.84 | 0.929 | 0.343* | |||

| (salp3) This brand uses price discounts more frequently than competing fashion brands | 2.85 | 1.023 | 0.834 | |||

| (salp4) Whenever I am offered free gifts from this brand, I feel like I have made a smart choice | 3.62 | 0.966 | 0.249* | |||

| (salp5) This brand offer gifts more frequently than competing fashion brands | 2.49 | 1.023 | 0.582 | |||

| Advertisements | 0.649 | 0.8471 | 0.85 | |||

| (Advt1) The advertisements for the brand are creative | 2.91 | 0.882 | 0.807 | |||

| (Advt2) The advertisements for the brand are original | 3.15 | 0.878 | 0.825 | |||

| (Advt3) The advertisements for the brand are different from the advertisements for competing fashion brands | 3.01 | 0.904 | 0.784 | |||

| Compulsive Buying | 0.418 | 0.6823 | 0.69 | |||

| (Comp1) I feel others will be horrified if they know of my spending habits. | 2.82 | 1.082 | 0.616 | |||

| (Comp2) I buy things even though I cannot afford them. | 2.32 | 1.197 | 0.685 | |||

| (Comp3) I feel anxious or nervous on days I do not go shopping. | 1.94 | 1.061 | 0.636 | |||

| (Comp4) I make only the minimum payments on my credit cards. | 2.63 | 1.23 | 0.342* | |||

All seven study constructs met the criteria as presented in Table 2. The AVE from each latent variable was greater than the squared correlations between the latent variable and all the other variables. Additionally, Cronbach’s alpha values of the constructs were within the values recommended by Hair et al. (2010); thus, the proposed model established discriminant validity.

The measured model fit indices examined the relationships between the observed measures (indicators) and the latent variables (constructs). Fit indices of the measurement model are , df=231, IFI=.919, TLI=0.902, CFI=0.918, RMSEA=0.055, and SRMR=0.0515. All these fit indices are within the threshold values recommended by Byrne (2013). Thus, the proposed measurement model confirmed the goodness of the fit, as indicated in Table 3.

| Table 3 Discriminant Validity of the Constructs | |||||||||

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 1. Self-esteem | 3.946 | 0.707 | 0.72 | ||||||

| 2. Materialism | 2.795 | 0.848 | .194** | 0.692 | |||||

| 3. Impulsive Buying | 2.753 | 0.928 | 0.001 | .107* | 0.763 | ||||

| 4. credit card misuse | 2.398 | 0.894 | -.106* | .243** | .231** | 0.645 | |||

| 5. Sales Promotions | 2.888 | 0.791 | -0.048 | 0.036 | 0.034 | .170** | 0.708 | ||

| 6. Advertisements | 3.024 | 0.777 | 0.035 | -0.093 | 0.032 | 0.082 | .125* | 0.806 | |

| 7. Compulsive Buying | 2.358 | 0.873 | 0.004 | .315** | .415** | .453** | 0.093 | 0.011 | 0.646 |

Structural Model Analysis

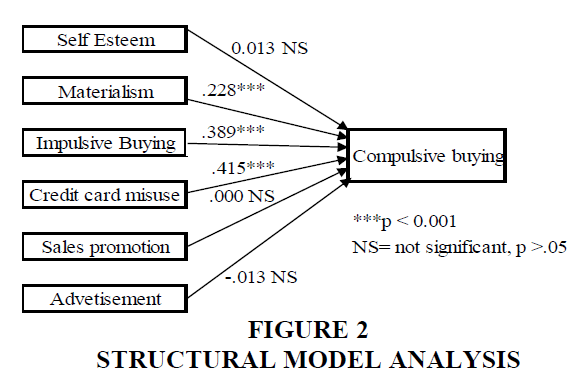

After confirming the factor structure of the constructs, structural equation modelling (SEM) with the maximum likelihood estimation method (MLE) was used because it supports both exploratory and confirmatory research, as presented in Figure 2 (Elmelegy et al., 2017; Gefen et al., 2000; Ponnaiyan et al., 2021). The fit indices that emerged from the structural model were , df=230, IFI=.924, TLI=0.907, CFI=0.923, RMSEA=0.054, and SRMR=0.0515. The model fit falls within the values recommended by Byrne (2013), indicating that the proposed model has an acceptable fit. The implies that the six independent variables in the model explain 59% of the variance in the dependent variable, compulsive buying, which is a good association between the independent and dependent variables.

The results reveal that materialism, impulsive buying, and credit card misuse have a significant direct effect on Egyptian customers’ compulsive buying at p < .001, implying that H2, H3, and H4 are supported. The other three variables (self-esteem, sales promotion, and advertisements) do not affect compulsive buying by customers, thereby not supporting H1, H5, and H6 since these variables have p >.05. Additionally, we controlled for age, sex, and income, none of which became significant.

Discussion

This study aims to examine the effects of external (advertisements, sales promotions, and credit card misuse) and internal (self-esteem, materialism, and impulsive buying) factors on compulsive buying in Egypt’s fashion industry.

Unlike the results of previous studies (Biolcati, 2017; Roberts et al., 2014; Yurchisin & Johnson, 2004; O'Guinn & Faber, 1989), which indicated a direct negative relationship between self-esteem and compulsive buying behaviours, the results of this research indicate that there is an insignificant relationship (β1=0.013, t=.211, p=0.833>.05) between self-esteem and compulsive buying behaviour among Egyptian consumers. This insignificance might be due to the cultural or economic differences between Egyptian consumers and consumers in other countries spending patterns, income disparities, and cultural values such as family, social status, or social trends (Tarka & Harnish, 2023) might have a stronger impact on purchasing decisions than self-esteem. Therefore, additional aspects like economic and cultural factors should be examined in future research to better understand the behaviour of compulsive consumers in future research.

The study results indicate that a significant positive relationship exists between materialism and compulsive buying in Egypt’s fashion industry (β2=0.228, t=3.381, p<.001), supporting hypothesis H2. The results are similar to previous studies (Islam et al., 2017; Sharif & Khanekharab, 2017; Villardefrancos and Otero-López 2016; Pham et al., 2012; Mueller et al., 2011; Yurchisin and Johnson, 2004), which stated that materialism directly influences compulsive buying. They indicate that consumers with materialistic values and characteristics are more likely to develop compulsive buying behaviors.

The findings of this study also support H3 by showing a positive relationship (β3=0.389, t=6.164, p<.001) between impulsive buying and consumers' compulsive buying behaviours in Egypt’s fashion industry. These results are consistent with those of previous studies (Darrat et al., 2016; Vogt et al., 2015; Omar et al., 2014; Billieux et al., 2008; O'Guinn & Faber, 1989; Valence et al., 1988;). These results indicate that consumers who purchase impulsively are more likely to become compulsive buyers.

The results of this study support (H4) (β4=0.415, t=5.791, p<0.001). These findings agree with those of previous studies (Aslanoğlu & Korga, 2017; Simanjuntak and Rosifa, 2016; Fagerstorm and Hantual, 2013; Joireman et al., 2010; Park and Burns, 2005; Roberts and Jones, 2001) which explain that the usage of credit cards influences compulsive buying behaviour either directly or indirectly. Consumers tend to believe that buying now and paying later facilitates the purchasing process, thus increasing buyers’ tendencies to become more compulsive.

Regarding sales promotions, this study hypothesized (H5) a direct positive relationship between sales promotions and compulsive buying. These findings do not support this hypothesis (β5=0.000, t=0.003, p=0.998>0.05). The result is inconsistent with the findings of previous researchers (Obeid, 2015; Wang & Jing, 2015; Kukar-Kinney et al., 2012) that state that sales promotion and specifically price discounts influence compulsive buyers purchase decisions. The difference between the results might be due to the sales promotions (mainly seasonal discounts) occurring during specific and fixed times in Egypt. Compulsive buyers tend to lose control easily and cannot wait for promotions to make purchases. In other words, while the sales promotion factor is appealing on the rational level, compulsive buyers tend to lack rationality when it comes to purchasing.

Finally, hypothesis six stated that advertising has a significant positive influence on compulsive buying was not supported (β6=-0.013, t=-.235, p=0.814>.05). This result is inconsistent with the findings of previous studies that explain that advertisements influence consumers' purchase decisions and increase their purchase intentions (Fatima & Lodhi, 2015; Yuksel & Eroglu, 2015; Ampofo, 2014). However, Kawak et al. (2002) believed that a negative relationship exists between consumers with compulsive buying tendencies and their attitudes toward advertisements. This difference in findings could be because fashion brands in Egypt do not invest heavily in different advertising methods. They depend primarily on different social media platforms and mobile messages to announce promotions and new collections. However, they rarely use television, radio, or billboard advertisements. This might be due to the governmental policies, norms, habits, and values in Egypt that limit or restrict the usage of certain models, ideas, or advertising messages.

Theoretical and Practical Contributions of the Study

This study contributes to a more refined understanding of compulsive buying behaviour among Egyptian consumers within the fashion industry, making notable contributions to both theoretical frameworks and practical applications in the field of consumer behaviour. Theoretically, our study extends existing model of consumer behaviour by adding and exploring new external variables such as credit card misuse and internal/ psychological variables such as impulsive tendencies to better understand factors that can lead to compulsive behaviour which is considered as an abnormal behaviour. The finding of this study offers practical insights for marketers and policymakers seeking to customise their marketing strategies to fit the Egyptian fashion market. Also, understanding the factors triggering compulsive buying behaviours will allow socially responsible fashion brands to develop educational campaigns to promote responsible consumption.

Practical Implications for Fashion Industry

Based on the results of this study, several practical recommendations are discussed in this section. Fashion brand managers should consider offering beneficial and innovative products at affordable prices that could immediately attract consumers' attention, while simultaneously satisfying their needs and wants. For example, they could improve the functionality and durability of fashion products. Moreover, the presentation of products also affects buyers' purchasing decisions; the arrangement and organization of clothes makes it easier for buyers to make decisions.

The study revealed that the higher the materialistic value the customer holds the higher the tendency to become compulsive buyers. Thus, fashion brand managers could consider positioning their brands differently from their competitors. Creating a sense of uniqueness for the brand and highlighting tangible aspects such as high quality and exclusivity will help customers, especially materialistic ones, to perceive it as a status brand. Moreover, they can use well-known and credible celebrities and influencers to represent their brands. Seeing a celebrity wear a certain brand at different events, not only in advertisements, might influence consumers' purchase decisions. Linking materialistic values with advertisement might help fashion brands in influencing decisions of Egyptian customers. For instance, developing creative advertisements that strike to achieve a balance between value driven content and materialistic appeals using media preferred by the Egyptian consumers might lead to better results.

Moreover, fashion brands should consider developing collaborations with different banks and facilitating the use of credit cards while offering an interest-free service so that consumers will benefit as well. Credit card misuse has emerged as the second most significant factor influencing compulsive buying. Thus, brand managers should offer promotions and better services for consumers purchasing with credit cards, while trying to limit the negative consequences and consumers' debt by reducing or eliminating interest.

Fashion brands should consider various advertising methods. Most fashion brands in Egypt depend heavily on social media to announce the arrival of new products or price discounts while rarely investing in the traditional advertising methods (T.V., radio, social media, billboards, etc.) that many consumers can easily reach and still dominate the Egyptian market even after the introduction of different digital platforms (Samir, 2023). For instance, advertising fashion brands in fashion special magazines is recommended. Also, out of home advertisement is heavily used in Egypt especially in crowded places in big cities such as Cairo (Samir, 2023). Thus, the usage of billboards might attract customers and influence their decisions.

Given the fact that compulsive buying behaviour is a negative behavior that has a vast number of negative consequences on consumers (Edwards, 1993; Kukar-Kinney et al., 2012; O’Guinn & Faber, 1989). Additionally, we are living in the time where green and social marketing are becoming increasingly prevalent (Kerin et al., 2011). Therefore, it is recommended for sustainable and socially responsible fashion brands to create an initiative in collaboration with the Egyptian government, highlighting the negative consequences of compulsive buying behaviour. They could facilitate recommendations offered by marketing experts and psychologists to customers engaging with this initiative that would help in controlling their compulsive consumption.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has a few limitations. It investigates compulsive buying and its influencing factors in the traditional environment. Future research could study the factors influencing compulsive online buying behaviour, as they might differ from the currently studied factors. Another limitation of this study is the sample which was collected from respondents working at academic institutions in Cairo, Egypt due to easy and convenient access during the COVID-19 pandemic. This might limit the generalizability of the results. Future searches are encouraged to explore other developing countries and respondents from various other industries.

This study tests the antecedents of compulsive buying in the fashion industry. Future studies could investigate the relationship between external and internal factors influencing compulsive buying behaviour in several other industries, such as fast-moving consumer goods (FMCGs). In addition, future studies could explore the influence of other internal variables, such as personality traits and social, emotional intelligence, and external factors such as financial and economic elements and test their impact on the compulsive buying behaviour of consumers. Other external variables could also be studied to examine their effects on compulsive buying. For instance, future studies could investigate the influence of culture on compulsive buying behaviour, as well as peer pressure, which might have a positive relationship with compulsive buying. Besides, a study on mediating and moderating effects of these variables could provide further insights. Future studies could explore consumer behaviour and online shopping in the new era of digitalization (Blaique et al, 2024; Sharma & Jhamb, 2020).

Conclusion

This study tests the relationship between internal (self-esteem, materialism, and impulsive buying) and external (sales promotions, advertising, and credit card misuse) factors and compulsive buying behaviour of Egyptian consumers in the fashion industry. This study was conducted in Egypt’s fashion industry. A total of 373 questionnaires were collected and analyzed.

The findings indicate that internal factors (materialism and impulsive buying) have a significantly positive influence on compulsive buying behaviour. Regarding external factors, results show that there is a significant positive relationship between credit card misuse and compulsive buying behaviour while advertising and sales promotion were found not to affect compulsive buying behaviour. Research recommendations were developed to help fashion brand managers better understand consumers and the factors influencing their buying decisions.

Declarations

Originality: We declare that this manuscript is an original work, and it has not been published previously nor is it under consideration for publication elsewhere. Any data, figures, or ideas borrowed from other sources are properly cited.

Authorship

All authors listed on this manuscript have contributed significantly to the research and preparation of this manuscript. Each author has reviewed the final version of the manuscript and agrees to its submission for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that there are no conflicts of interest that could influence the results or interpretation of the findings presented in this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

Abdellatif, D. (2014). Overview of the retail market in Egypt. Infomineo, viewed 07 February 2020.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt. (2021). Real Estate: A Brand-New Landscape.

Ampofo, A. (2014). Effects of advertising on consumer buying behaviour: With reference to demand for cosmetic products in Bangalore, India. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Aslano?lu, S., & Korga, S. (2017) - credit card usage and compulsive buying: an application in Kirikkale. Journal of Business Research - Turk, 9(1), 148–165.

Badgaiyan, A. Verma, A. & Dixit, S. (2016). Impulsive buying tendency: Measuring important relationships with a new perspective and an indigenous scale. IIMB Management Review, 28(4).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Billieux, J., Rochat, L., Rebetez, M. M., & Van der Linden, M. (2008). Are all facets of impulsivity related to self-reported compulsive buying behavior? Personality and Individual Differences, 44(6), 1432–1442.

Biolcati, R. (2017). The role of self-esteem and fear of negative evaluation in compulsive buying. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Blaique, L., Abu-Salim, T., Asad Mir, F., & Omahony, B. (2024). The impact of social and organisational capital on service innovation capability during COVID-19: the mediating role of strategic environmental scanning. European Journal of Innovation Management, 27(1), 1-26.

Buil, I, Chernatony, L. &Martínez, E. (2013). Examining the role of advertising and sales promotions in brand equity creation. Journal of Business Research, 6.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural Equation Modeling with Amos.

Chin, W. W. (2009). How to write up and report PLS analyses. Handbook of Partial Least Squares, 655–690.

Churchill, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73.

Darrat, A. A., Darrat, M. A., & Amyx, D. (2016). How impulse buying influences compulsive buying: The central role of consumer anxiety and escapism. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 31, 103–108.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dittmar, H. (2005). Compulsive buying--a growing concern? An examination of gender, age, and endorsement of materialistic values as predictors. British Journal of Psychology, 4, pp. 467-491.

Edwards, E. A. (1993). Development of a new scale for measuring compulsive buying behavior. Financial Counseling and Planning, 4, 67–84.

El Din, D.G. and El Sahn, F. (2013), “Measuring the factors affecting Egyptian consumers’ intentions to purchase global luxury fashion brands”, The Business and Management Review, Vol. 3 No. 4, p. 44

Elmelegy, A. R., Ponnaiyan, S., & Alnajem, M. N. (2017). Antecedents of Hypermarket Service Quality in the United Arab Emirates. Quality Management Journal, 24(4), 35–48.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fatima, S. & Lodhi, S. (2015) 'Impact of Advertisement on Buying Behaviors of the consumers: Study of Cosmetic Industry in Karachi City', International Journal of Management Sciences and Business Research, 10(4).

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Gefen, D., Straub, D., & Boudreau, M. C. (2000). Structural equation modelling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the association for information systems, 4(1), 7.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed., Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.: Prentice-Hall.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Harnish, R. J., Roche, M. J. and Bridges, K. R. (2021) “Predicting compulsive buying from pathological personality traits, stressors, and purchasing behavior,” Personality and individual differences, 177(110821), p. 110821.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

He, H., Kukar-Kinney, M., & Ridgway, N. M. (2018). Compulsive buying in China: Measurement, prevalence, and online drivers. Journal of Business Research, 91, 28-39.

Huang, C. C., Wang, Y. M., Wu, T. W., & Wang, P. A. (2013). An empirical analysis of the antecedents and performance consequences of using the moodle platform. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 3(2), 217.

Huang, Z., Li, H., Wang, P., & Huang, J. (2022). Effects of Low-Calorie Nutrition Claim on Consumption of Packaged Food in China: An Application of the Model of Consumer Behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 799802.

Islam, T., Wei, J., Sheikh, Z., Hameed, Z., & Azam, R. I. (2017). Determinants of compulsive buying behavior among young adults: The mediating role of materialism. Journal of Adolescence, 61, 117–130.

Johnson, T., & Attmann, J. (2009). Compulsive buying in a product specific context: clothing. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 13(3), 394–405.

Joireman, J., Kees, J., & Sprott, D. (2010). Concern with immediate consequences magnifies the impact of compulsive buying tendencies on college students’ credit card debt. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(1), 155–178.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kerin, R. A., S. W. Hartley, & W. Rudelius. (2011). Marketing, (10th Eds.). New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Khalifa, D., & Sahn, F. (2013). Measuring the factors affecting Egyptian consumers’ intentions to purchase global luxury fashion brands. The Business & Management Review, 3(4).

Khare, A. (2013). Credit Card Use and Compulsive Buying Behavior, Journal of Global Marketing, 26(1), 28.

Khare, A. (2014). Money Attitudes, Materialism, and Compulsiveness: Scale Development and Validation. Journal of Global Marketing, 27(1), 30-45

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kothari, H., & Mallik, G. (2015).The comparative analysis of the impact of self-esteem on the compulsive and non-compulsive buyers in NCR. Journal of Business Management & Social Sciences Research, 4(1), 78–88.

Kotler, P. & Armstrong, G. (2019). Principles of Marketing: Global Edition. 18th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Pearson Education.

Kukar-Kinney, M., Ridgway, N. M., & Monroe, K. B. (2012). The role of price in the behavior and purchase decisions of compulsive buyers. Journal of Retailing, 88(1), 63–71.

Lam, L. W. (2012). Impact of competitiveness on salespeople's commitment and performance. Journal of Business Research, 65(9), 1328-1334.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Lavuri, R. (2021). Intrinsic factors affecting online impulsive shopping during the COVID-19 in emerging markets. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 18(4), 958-977.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Letunovska, N., Yashkina, O., Saher, L., Alkhashrami, F. A., & Nikitin, Y. (2021). Analysis of the model of consumer behavior in the healthy products segment as a perspective for the inclusive marketing development. Marketing i mened?ment innovacij, (4), 20-35.

Mendez, M. (2012). Sales Promotions Effects on Brand Loyalty Unpublished PhD thesis.

Moon, M., Faheem, S., & Farooq, A. (2022). I, me, and my everything: Self conceptual traits and compulsive buying behavior. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 68.

Mueller, A., Mitchell, J. E., Peterson, L. A., Faber, R. J., Steffen, K. J., Crosby, R. D., & Claes, L. (2011). Depression, materialism, and excessive Internet use in relation to compulsive buying. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52(4), 420–424.

Muruganantham, G., & Bhakat, R., (2013). A Review of Impulse Buying Behavior. International Journal of Marketing Studies,5(3).

Nunnally, J.C. (1978). Psychometric theory. 2nd ed. McGraw Hill, New York.

O’Guinn, T. C., & Faber, R. J. (1989). Compulsive Buying: A Phenomenological Exploration. The Journal of Consumer Research, 16(2), 147. https://doi.org/10.1086/209204

Obeid, M. (2015). The effect of sales promotion tools on behavioral responses. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 3, 28–31.

Omar, N.A., Rahim, R.A., Wel, C.A., & Alam, S.S. (2014). Compulsive buying and credit card misuse among credit card holders: The roles of self-esteem, materialism, impulsive buying, and budget constraint. Intangible Capital, 10(1), 5274.

Park, H.-J., & Davis Burns, L. (2005). Fashion orientation, credit card use, and compulsive buying. The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 22(3), 135–141.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Pham, T. H., Yap, K., & Dowling, N. A. (2012). The impact of financial management practices and financial attitudes on the relationship between materialism and compulsive buying. Journal Of Economic Psychology, 33(3), 461–470.

Ponnaiyan, S., Ababneh, K. I., & Prybutok, V. (2021). Determinants of fast-food restaurant service quality in the United Arab Emirates. Quality Management Journal, 28(2), 86–97.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rahmani, Z., Mojaveri, H. S., & Allahbakhsh, A. (2012). Review the Impact of Advertising and Sale Promotion on Brand Equity. Journal of Business Studies Quarterly, 4(1).

Richins, M.L. & Dawson, S. (1992). A Consumer Values Orientation for Materialism and Its Measurement: Scale Development and Validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3).

Roberts, J. A., & Jones, E. (2001). Money attitudes, credit card use, and compulsive buying among American college students. Journal of consumer affairs, 35(2), 213-240.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Roberts, J. A., Manolis, C., & Pullig, C. (2014). Contingent self-esteem, self-presentational concerns, and compulsive buying: Contingent self-esteem, self-presentational concerns, and compulsive buying. Psychology & Marketing, 31(2), 147–160.

Rook, D.W. & Fisher, R.J. (1995). Normative Influences on Impulsive Buying Behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 22(3).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rosenberg, M., (1965). Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Acceptance and commitment therapy. Measures package, 61(52).

Samir, A. S (2023). An overview on the development of advertising in Egypt, UK, and Belarus. Slovak international Scientific Journal, 68.

Sharif, S. P., & Khanekharab, J. (2017). Identity confusion and materialism mediate the relationship between excessive social network site usage and online compulsive buying. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 20(8), 494–500.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sharma, A., & Jhamb, D. (2020). Changing consumer behaviours towards online shopping-an impact of Covid 19. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 24(3), 1-10.

Simanjuntak, M. and Rosifa, A. S. (2016) Self-esteem, money attitude, credit card usage, and compulsive buying behaviour. Economic journal of emerging markets, 8(2).

Talaat, R. M. (2022). Fashion consciousness, materialism, and fashion clothing purchase involvement of young fashion consumers in Egypt: the mediation role of materialism. Journal of humanities and applied social sciences, 4(2), 132-154.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tarka, P., & Harnish, R. (2023). Toward Better Understanding the Materialism-Hedonism and the Big Five Personality-Compulsive Buying Relationships: A New Consumer Cultural Perspective. Journal of Global Marketing.

Valence, G., d’Astous, A., & Fortier, L. (1988). Compulsive buying: Concept and measurement. Journal of Consumer Policy, 11(4), 419–433.

Villardefrancos, E., & Otero-López, J. M. (2016). Compulsive buying in univer0073ity students: its prevalence and relationships with materialism, psychological distress symptoms, and subjective well-being. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 65, 128–135.

Vogt, S., Hunger, A., Pietrowsky, R., & Gerlach, A. L. (2015). Impulsivity in consumers with high compulsive buying propensity. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 7, 54–64.

Wang, M., & Jing, X. (2015). The study of sales promotion and compulsive buying. Journal of Management and Strategy, 6(2).

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Yegina, N. A., Zemskova, E. S., Anikina, N. V., & Gorin, V. A. (2020). Model of consumer behavior during the digital transformation of the economy. Industrial Engineering & Management Systems, 19(3), 576-588.

Yuksel, C., & Eroglu, F. (2015). The Effects of Personal Factors and Attitudes toward Advertising on Compulsive Buying Tendency. Journal of Marketing and Marketing Research, 16, 43–70.

Yurchisin, J., & Johnson, K. K. P. (2004). Compulsive buying behavior and its relationship to perceived social status associated with buying, materialism, self-esteem, and apparel-product involvement. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 32(3), 291–314.

Received: 05-Aug-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-15119; Editor assigned: 06-Aug-2024, PreQC No. AMSJ-24-15119(PQ); Reviewed: 26-Sep-2024, QC No. AMSJ-24-15119; Revised: 06-Oct-2024, Manuscript No. AMSJ-24-15119(R); Published: 11-Oct-2024